1. Introduction

In recent years, particularly in Europe and other Western countries, increasing attention has been devoted to issues of environmental sustainability, material circularity, and the reuse of products. The European Commission has adopted a set of proposals aimed at reducing net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030, compared to 1990 levels [

1]. These initiatives encompass a wide range of sectors, including energy, transportation, and taxation policies.

Among the most commonly used materials in construction are various mortars and concretes, whose main component is cement. Cement is produced from a mixture of limestone, clay, and sand, which is crushed, blended, and heated to a temperature of approximately 1450 °C [

2]. Another widely used material, mineral (stone) wool, is manufactured from molten minerals such as dolomite and limestone, with melting temperatures reaching up to 1600 °C [

3]. It is evident that achieving and maintaining such high temperatures requires substantial amounts of energy and results in significant CO

2 emissions, thereby increasing production costs. For these reasons, it is recommended to expand the use of wood and other organic materials in construction.

Wood has long been a widely used building material. In addition to solid wood, various engineered wood products are extensively employed in construction, including glued laminated beams, CLT panels, plywood, LVL, and particle-based boards such as OSB and MDF. Through the adhesive bonding of wooden elements [

4,

5,

6], it is possible not only to manufacture elements of various dimensions but also to improve certain material properties—reducing the variability of mechanical characteristics, minimizing environmental effects on dimensional and shape stability, and eliminating defects or anatomical features that negatively affect mechanical performance. This also broadens the potential applications of wood-based materials.

Furthermore, wood and wood-based composites are often modified to enhance their resistance to environmental factors such as moisture, fire, and biological degradation, thereby improving their durability. In the near future, as efforts intensify to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the role of wood in building construction is expected to increase even further.

A wide variety of synthetic fibers and plastics are used in industry and everyday life. Their production, performance characteristics, and sustainability criteria are regulated by numerous international standards and directives [

7,

8,

9]. In recent years, there has been a growing trend toward the use of organic-based, environmentally friendly, and biodegradable materials. Naturally, in each case, the material and the product manufactured from it must meet specific requirements—exhibiting suitable physical, mechanical, and functional properties, among others.

For instance, pectin and cellulose nanofiber (CNF) composites reinforced with sodium borate (NaB) demonstrate properties desirable for packaging applications intended for atmospheric exposure. These composites enable effective fruit preservation and moisture regulation. They are biodegradable and mechanically strong, exhibiting a tensile strength of 150 MPa and a toughness of 8.5 MJ/m

2, which are comparable to other bioplastic composites. Moreover, they show great potential for use in sustainable packaging applications [

10].

Another study has shown that fiber-reinforced polymer composites possess superior mechanical properties compared to traditional materials. Replacing synthetic fibers with natural fibers further reduces production costs [

11]. The research demonstrated that treated wheat straw fibers significantly improve tensile and flexural strength compared to untreated ones, particularly when used with epoxy resins. Specifically, the tensile strength of treated wheat straw fiber was found to be 54.4 MPa—approximately twice that of untreated fibers—while the flexural strength reached 88.76 MPa for treated fibers and 49.60 MPa for untreated ones.

One of the promising classes of materials that are currently being actively investigated is biocomposites produced from various organic materials and fungal mycelium species. These materials already play a significant role in the circular economy, can be manufactured from waste streams (e.g., lignocellulosic residues, plant biomass), and have the potential to replace petroleum-based materials [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

They can be applied in multiple sectors—packaging, construction, thermal insulation, bio textiles, as substitutes for conventional textile materials, as well as in the food industry [

12]. Materials such as expanded polystyrene (EPS) and glass fiber offer good thermal insulation performance but are synthetic and non-biodegradable. They pollute the environment, emit substantial amounts of CO

2 during production, and pose health hazards during installation. In one study [

13], the authors proposed using these biocomposites as air-filtration media. Owing to their high specific surface area, these structures effectively capture fine particulate matter, indicating potential as sustainable filters for urban air-pollution control.

In contrast, mycelium-based biocomposites do not exhibit these drawbacks and may even achieve comparable thermal conductivity values (approximately 0.03 W/mK) [

14]. In addition to thermal insulation, their porous, fibrous structure enables their use in sound insulation or absorption. It has been determined that, in the low-frequency range (from 500 Hz to 4300 Hz), the sound absorption coefficient (α) may range between 0.65 and 0.99 depending on material thickness and structure. These values are similar to those of traditional acoustic materials, such as glass wool, which typically exhibits α values of 0.40–0.99 in the same frequency range. Although glass–fiber composites may offer superior acoustic insulation at higher frequencies with thinner panels, their non-biodegradable nature and installation-related health risks make mycelium a safer and more sustainable alternative for comparable applications. Such materials can also be used for air purification.

Moreover, depending on the raw materials used in fabrication, mycelium-based composites can exhibit favorable mechanical properties. For example, composites produced from Pleurotus eryngii, hardwood sawdust combined with spent coffee grounds and stem fibers can reach an ultimate strength of up to 12.99 MPa and a Young’s modulus of 3.66 GPa. This versatility allows MBCs to meet diverse construction requirements—from thermal insulation to structural components—offering a degree of adaptability that conventional materials such as EPS or glass fiber generally do not provide. Another study [

15] examined the dependence of mechanical performance on ambient humidity. Samples were conditioned for 72 h at different humidity levels (23%, 54%, and 98%). The specimens, measuring 66 mm × 20 mm × 20 mm with a support span of 50 mm, withstood different loads in three-point bending tests. The flexural strength ranged from 172 to 335 kPa (low RH) and 232–364 kPa (medium RH). Increasing the substrate fraction in the composite resulted in higher flexural strength. Compared to other non-pressed mycelium composites, which typically exhibit flexural strengths of 50–290 kPa, the composites produced in this study demonstrated the ability to withstand greater bending loads.

The study [

16] investigated cost-reduction strategies for packaging-grade mycelium materials by partially substituting hemp shives with paper waste. When 30% paper waste was incorporated (using Ganoderma lucidum), the growth period increased from 20 days (pure hemp substrate) to 24 days, and the material density increased to 145 kg/m

3—still significantly lower than that of conventional pulp- or paper-based packaging materials (0.2–1.0 g/cm

3). At 60% relative humidity, the hybrid material absorbed 1.5% less moisture, whereas at 80% RH, it absorbed more than pure-hemp composites. Additionally, when the paper-waste fraction reached up to 35%, mechanical strength increased by 1.9–30.8%, depending on the fungal strain used; however, at 40%, the strength declined again. Thus, hybrid composites containing up to 30% paper waste are well suited for packaging applications in dry environments.

In studies [

17,

18,

19], the relationships among fungal species, substrate type, material structure, and mechanical performance of mycelium-based composites were extensively analyzed. The density of the produced specimens ranged from 136 to 283 kg/m

3, with compressive elastic modulus (MOE) values between 0.15 and 4.55 MPa, while the maximum recorded MOE reached 106.08 ± 40.65 MPa at a density of 286.67 kg/m

3. A clear correlation between density and elastic modulus was observed: an increase in density from 0.024 to 0.029 g/cm

3 corresponded to an increase in MOE from 0.6 MPa to 97 MPa. The choice of substrate—flax, hemp, wood, or straw fibers—significantly influenced composite performance, with hemp- and flax-based composites exhibiting the best mechanical properties. Hemp-based composites also showed the lowest water-absorption rates, indicating higher moisture resistance. Furthermore, fungal growth on different substrates induced specific chemical modifications, particularly within lignin and cellulose, enabling the development of tailored materials suitable for construction, packaging, and various industrial applications.

Meanwhile, paper [

20] compared two manufacturing approaches: naturally grown samples and samples subjected to hot-pressing at 180 °C. Hot-pressed composites exhibited higher density and superior mechanical properties, whereas naturally grown ones demonstrated better thermal-insulation performance. Thus, by adjusting the processing approach, materials can be tailored to meet the demands of specific applications. By selecting different fungal species, organic fillers, cultivation technologies, and growth conditions, it is possible to obtain biocomposites with distinct structures and physical–mechanical properties. A major challenge, however, is that these properties and processes are not yet standardized. Additionally, because the material is biodegradable, questions remain regarding its long-term durability [

12].

Overall, as emphasized in work [

21], the properties of mycelium-based biocomposites depend on numerous interacting variables, and further research is required to establish more precise correlations. One aspect is clear, however—such biocomposites generally exhibit inferior mechanical properties (e.g., elastic modulus typically below 100 MPa) compared to traditional materials used in furniture, interior, or structural applications. In addition, the service performance of the material and its behaviour under changing environmental conditions are of critical importance. And such studies are lacking.

The aim of this study is to evaluate the dependence of the viscoelastic properties of original biocomposite elements, produced from natural wood and mycelium, on ambient temperature and on the volumetric wood–mycelium ratio.

2. Materials and Methods

For the study, four types of original cross-sectional biocomposite samples (10 specimens of each type) were prepared, composed of spruce wood scantling and mycelium. Initially, the viscoelastic properties of the conditioned scantlings were determined (conditioning at 20 ± 0.5 °C and 60 ± 2% relative humidity for 2 weeks). In order to avoid anatomical defects (knots, fiber defects, etc.) found in natural wood, the scantlings were cut from high-quality glued panels.

Simultaneously, special molds were fabricated in four sizes based on internal dimensions (length × width × height): 585 × 50 × 50 mm, 585 × 50 × 100 mm, 585 × 100 × 50 mm, and 585 × 100 × 100 mm. A single scantling (580 × 49 × 18 mm) was placed into each mold, which was then filled with the substrate prepared according to the mycelium manufacturer’s instructions [

22]. These “preforms” were covered with perforated polyethylene and placed in a climatic chamber maintained at approximately 25 °C. After one week of “growth,” the formed wood–mycelium biocomposite samples were removed from the molds and subjected to post-treatment in the climatic chamber at ~80 °C for about 4 h and ~25% relative humidity. This step ensured the removal of excess moisture and terminated fungal activity, preventing the mycelium from performing any vital functions, even under otherwise favorable conditions.

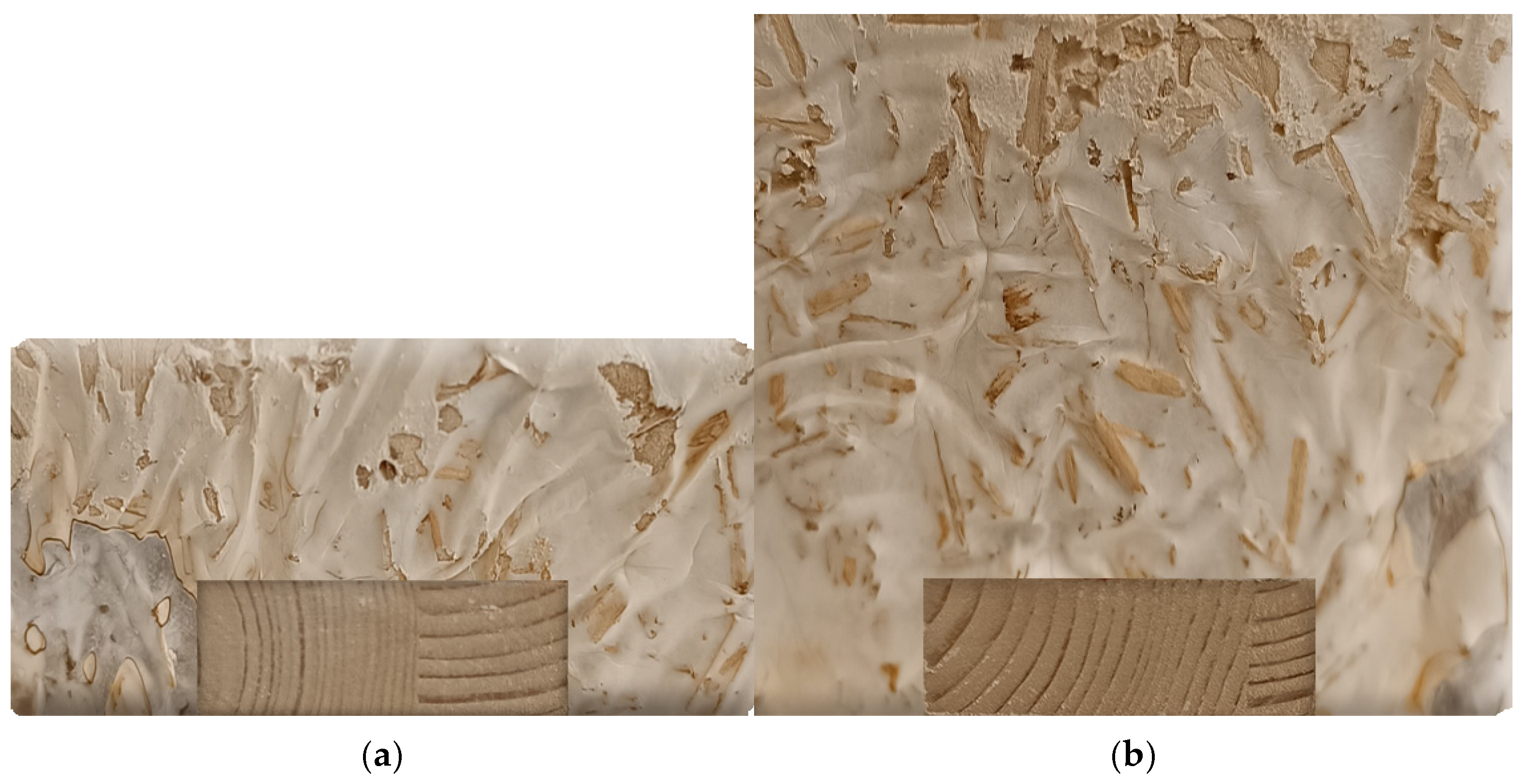

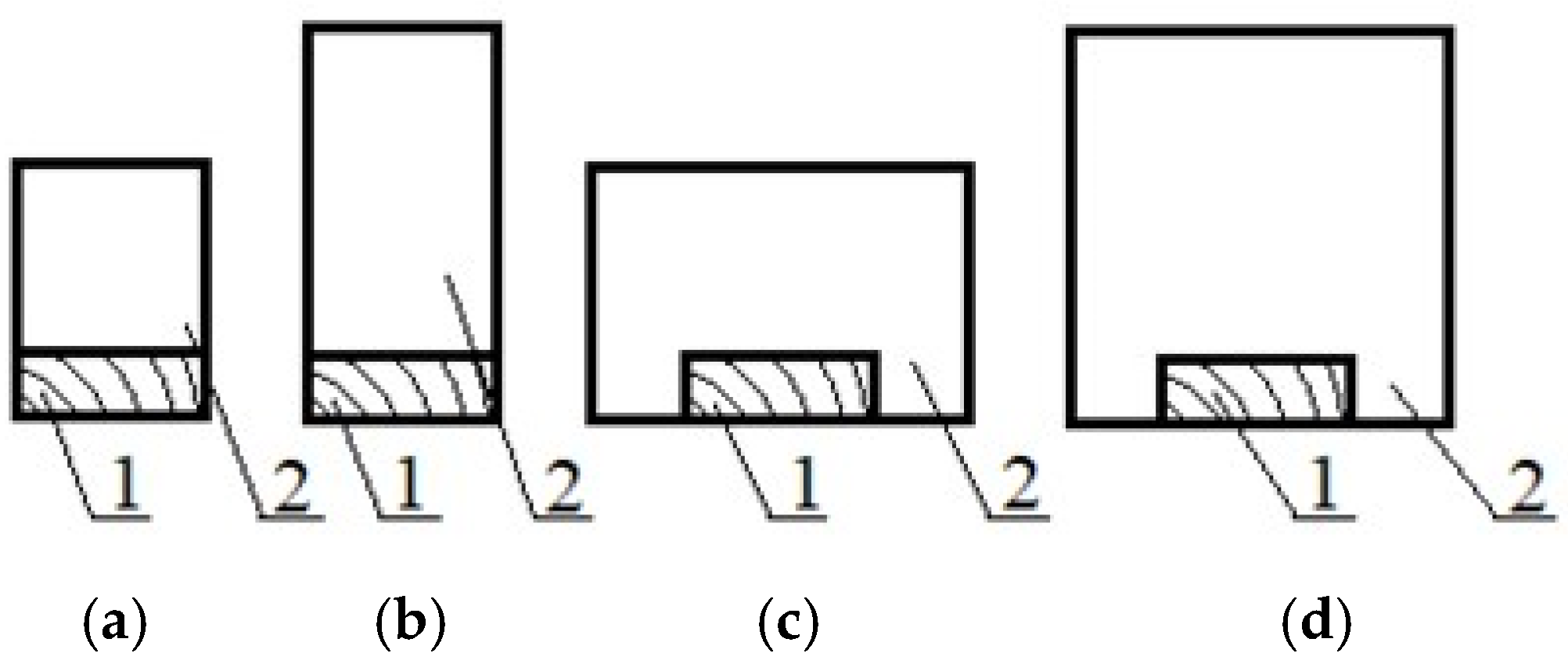

The resulting four sample groups were designated MW1, MW2, MW3, and MW4. Additionally, as a control group, 10 spruce wood scantlings were used, designated as 0W. A general view of the samples is presented in

Figure 1, and the cross-sectional schemes of the groups are shown in

Figure 2.

Prior to testing, the samples were conditioned for two weeks in a climatic chamber at 20 ± 0.5 °C and 60 ± 2% relative humidity. The average dimensions, mass, and density of each sample group after conditioning are presented in

Table 1. The moisture content of the spruce wood elements after conditioning was determined using an electronic moisture meter in accordance with standard EN 13183-2:2003. Moisture Content of a Piece of Sawn Timber—Part 2: Estimation by Electrical Resistance Method [

23]. It was found that moisture was in the range of 10–11%.

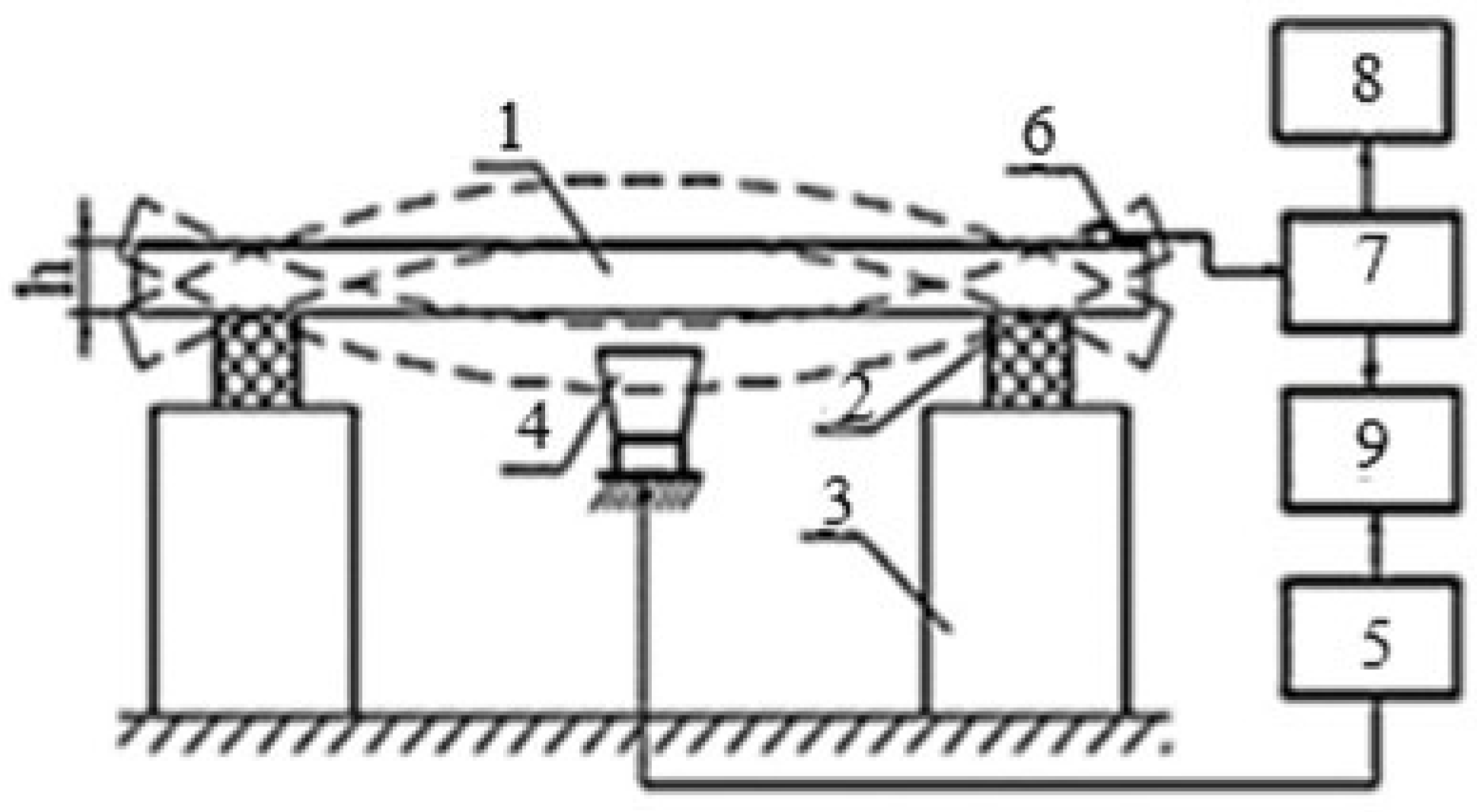

Subsequently, the viscoelastic properties of the samples, namely the dynamic modulus of elasticity (MOEd) and the coefficient of damping, were determined. The measurements were performed using a custom-built apparatus based on a non-destructive transverse resonance vibration method. By determining the resonant frequencies, frequency–amplitude characteristics, and vibration modes of the specimen, and taking into account the mounting conditions and geometrical parameters of the sample, the elastic properties of the material were calculated according to the theory of vibrations of an isotropic beam [

24,

25]. The experimental scheme is shown in

Figure 3.

The dynamic modulus of elasticity was calculated based on the following Equation (1):

where

E is dynamic modulus of elasticity; ƒ

rez is frequency of transverse vibrations; ρ is density of wood;

s is cross-sectional area;

l is beam length;

I is cross-sectional moment of inertia; and

A is e fastening method being used, as represented by a coefficient.

The viscous properties (coefficient of damping) of the specimens being studied were evaluated based on the following Equation (2):

where

ƒrez is frequency of transverse vibrations; Δ

ƒ is frequency bandwidth when vibration amplitude decreases by 0.7 times.

Initially, the viscoelastic properties of the scantlings used for biocomposite fabrication were determined after conditioning and compared with the properties of the produced biocomposites (the results are presented in

Table 2).

Subsequently, the testing procedure was conducted as follows: after the conditioning stage, the samples were kept for 24 h at –20 °C (hereafter referred to as C1) and tested individually, ensuring that each specimen was removed from the climatic chamber before it could warm up. After all specimens were tested under C1 conditions, they were returned to the climatic chamber at 20 ± 0.5 °C and 60 ± 2% relative humidity for 6 days. The same procedure was then repeated for samples kept 24 h at –10 °C (C2), with each specimen tested individually in the same manner. This procedure was repeated for 0 °C (C3), +20 °C and 40 ± 2% relative humidity (C4), and +40 °C and 40 ± 2% relative humidity (C5). According to the authors, these conditions correspond to realistic potential service conditions for the material in interior or structural applications. The results of the experiments are presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

4. Discussion

The study investigated the viscoelastic behavior of biocomposites composed of spruce wood scantlings and mycelium under varying environmental conditions. As expected, natural spruce wood and mycelium exhibit substantially different physical and mechanical properties, and therefore, the volume ratio of wood to mycelium within the biocomposite largely determines its overall characteristics.

The densities of individual wood scantlings groups were relatively consistent, with average values ranging from 453 to 464 kg/m3. In the biocomposite samples where the wood scantling comprised approximately 37% of the total volume, the average density was 243 kg/m3. For samples with 20–22% wood content, densities ranged from 181 to 190 kg/m3, and in samples with only ~11% wood, the average density decreased to 148 kg/m3.

The dynamic modulus of elasticity (MOEd) and coefficient of damping of the biocomposites depended not only on the wood–mycelium volume ratio but also on the position of the wood scantling in the sample. Generally, as the proportion of wood decreased, the MOEd decreased—from 520 MPa at 37% wood to 92 MPa at 11% wood. In contrast, the coefficient of damping was more influenced by the alignment of wood and mycelium along the transverse vibration direction, varying between 0.033 and 0.045 r.u.

Analysis of the temperature-dependent behavior revealed several notable trends. The control group (0W), consisting of pure spruce wood scantlings, exhibited mechanical properties consistent with literature values [

4,

25,

26,

27]. As temperature increased, the scantlings became more plastic, evidenced by a decrease in MOEd (from 10,465 MPa to 10,116 MPa, ~3.3%) and an increase in the coefficient of damping (from 0.018 r.u. to 0.024 r.u., ~30%). In individual specimens, variations ranged from 2.1 to 4.5% for MOEd and 22–45% for coefficient of damping, likely due to softening of the cellulose matrix and partial freezing of bound moisture at subzero temperatures.

Among the biocomposite groups, MW1, with 37% wood content, behaved most similarly to natural wood. The average MOEd decreased from 540 MPa to 519 MPa (~3.8%), while the coefficient of damping increased by ~19% (0.038 → 0.046 r.u.), reflecting the influence of both wood and mycelial matrix.

The MW2 and MW3 groups, with ~20–22% wood content, demonstrated that both MOEd and the coefficient of damping are influenced not only by wood content but also by scantling positioning (

Figure 2). Despite similar volume fractions, the MW2 samples exhibited lower MOEd and higher damping, with MOEd decreasing from 140 to 135 MPa (~3.6%) and from 331 to 314 MPa (~5.1%) for MW2 and MW3, respectively. The corresponding increases in the damping coefficient were ~21% (MW2) and ~28% (MW3).

This can be explained by the fact that bending behaviour (and thus vibration response) is more strongly affected by the specimen height rather than its width. Consequently, in the MW2 group, the mycelium had a greater relative influence on the overall vibrational behaviour of the specimens. Since the mechanical properties of mycelium are generally less sensitive to temperature changes than those of natural wood (as evidenced by the results), the viscoelastic properties of the MW2 composite varied less with temperature compared to the MW3 group.

In the MW4 group, containing only ~11% wood, MOEd remained practically constant with temperature (variation ~3 MPa), whereas the coefficient of damping increased similarly to other groups (~0.038 → 0.046 r.u., ~21%). Notably, values of coefficient of damping were comparable to MW2 and higher than MW3, confirming that damping depends not only on the wood–mycelium volume ratio but also on component orientation relative to the vibration direction.

Overall, the results suggest that the mycelial matrix forms a relatively weak bond, and the low composite density indicates a sparse distribution of particles, which explains the generally low MOEd. In composites with ≥20% wood, the decrease in MOEd with increasing temperature is primarily attributed to softening of the wood scantlings, whereas in samples with lower wood content, temperature has minimal effect. The increase in coefficient of damping with temperature is likely due to enhanced plasticity not only of the wood but also of the mycelial hyphal network, improving energy dissipation during vibrations.

All obtained results were subjected to statistical analysis. For each sample group maintained at the different test temperatures, the standard deviation of the dynamic modulus of elasticity (MOEd) and the coefficient of damping was calculated. Due to the inherent variability in the mechanical properties of wood (as reported in the Wood Handbook and other sources), the standard deviation of MOEd for the wood scantlings groups ranged from 420 to 750 MPa. For the biocomposite groups, the ranges were: MW1—42–55 MPa, MW2—1–4 MPa, MW3—23–32 MPa, and MW4—2–5 MPa. These values correspond to approximately 6% for 0W, 9% for MW1, 2% for MW2, 8% for MW3, and 4% for MW4 of the respective group mean values. These results indicate that a higher mycelium content, particularly along the bending direction of the sample, contributes to more uniform mechanical properties within the biocomposite group. Thus, the variation in dynamic modulus for mycelium is considerably lower than that observed for natural wood.

Regarding the coefficient damping, the standard deviation for natural wood was approximately 0.002 r.u., corresponding to about 10% of the mean value. For the biocomposite groups, the standard deviations were: MW1—8–14%, MW2—4–7%, MW3—7–11%, and MW4—3–4%. These results again suggest that the viscous properties of mycelium are more uniformly distributed. Furthermore, in samples aligned along the bending direction (MW2 and MW4), the variation in coefficient of damping was lower than in other biocomposite groups or natural spruce wood. Since bending behaviour (and consequently vibration response) is primarily governed by the specimen height, the results (and their variability) are more strongly influenced by the mycelium in cases where the specimens are taller.