Tailoring Fe-Pt Composite Nanostructures Through Iron Precursor Selection in Aqueous Low-Temperature Synthesis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aqueous Synthesis of Fe-Pt Nanocomposites

- system A (Fe(III)-based): iron(III) ammonium sulfate (NH4Fe(SO4)2) in a dilute HNO3 supporting electrolyte;

- system B (Fe(II)-based): iron(II) sulfate (FeSO4) in a dilute H2SO4 supporting electrolyte.

2.2. Elemental Analysis of Composite Powders

2.3. Structural Characterization of Composite Phases and Thermal Stability

2.3.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

- laboratory XRD: a Bruker D8 ADVANCE A25 diffractometer (Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) with Cu Kα radiation (Ni filter) was used, scanning from 10–90° 2θ with a step size of 0.02°;

- synchrotron radiation (SR) XRD: High-resolution patterns were acquired at the VEPP-4M storage ring (λ = 0.17836 Å) in transmission mode using a MAR3450 detector (Marresearch GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) (2θ range: 1–25°) [24]. Two-dimensional patterns were integrated into one-dimensional intensity profiles [25].

2.3.2. In-Situ High-Temperature XRD for Phase Evolution

2.3.3. High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (HRTEM)

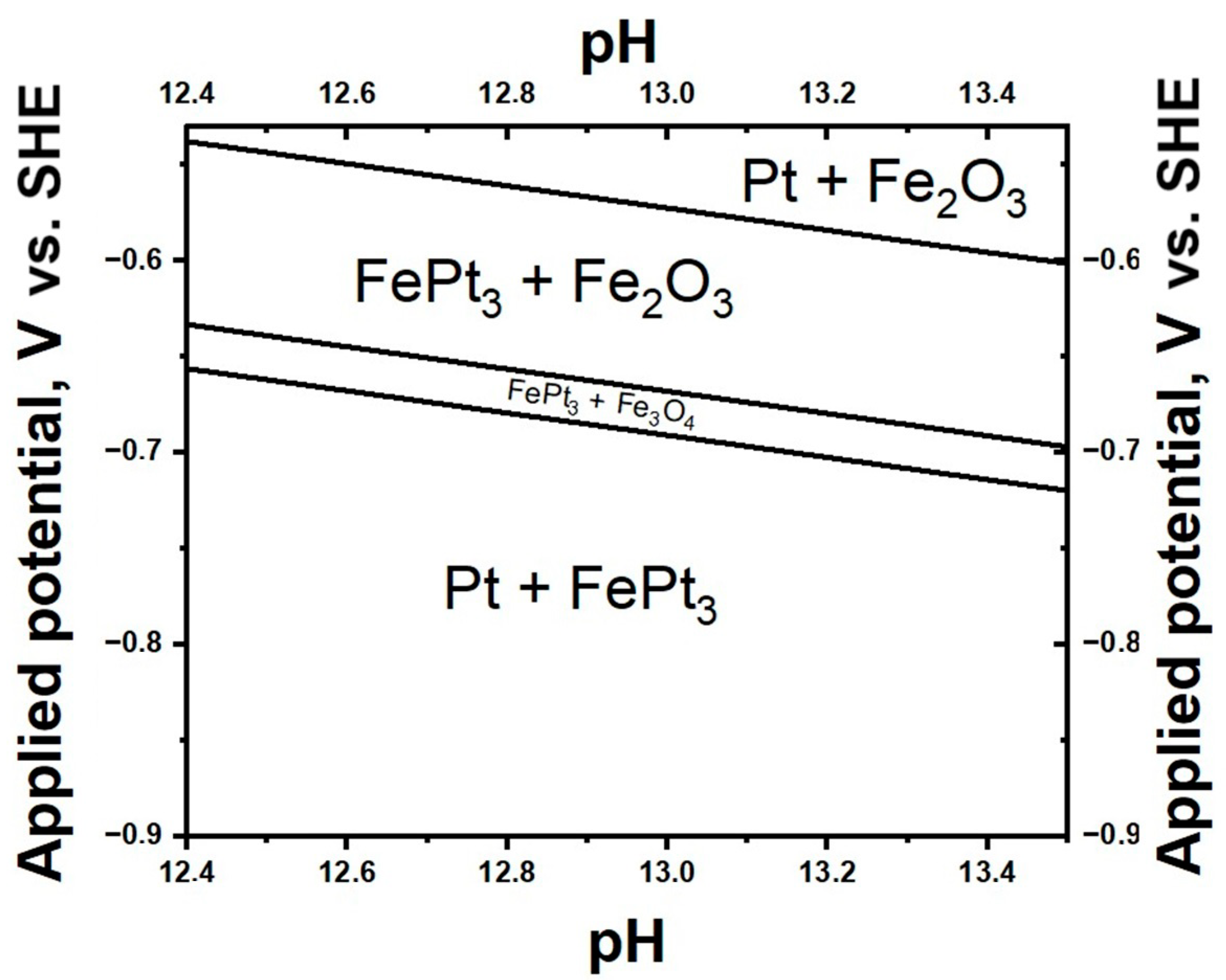

2.4. Theoretical Analysis of Phase Stability

3. Results

3.1. Elemental Composition and Theoretical Phase Stability of Fe-Pt Composite Powders

3.2. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis, HRTEM and SAED: Revealing Precursor-Dependent Composite Architecture and the Full Composite Morphology

- a Pt-rich FCC solid solution (as a dominant phase, ~61% of the crystalline fraction) with a lattice parameter of 3.923 Å, consistent with nearly pure platinum, and a small crystallite size of ~4 nm;

- an Fe-Pt FCC solid solution with a smaller lattice parameter of 3.903 ± 0.001 Å, corresponding to an iron content of 9.8 at.% and larger crystallites of ~10 nm.

- ultra-fine metallic iron (XRNDPh): particles of 1–3 nm identifiable as pure FCC iron (PDF No. 88-2324) with lattice fringes (2.41 Å, 1.99 Å), which correspond to the (110) and (111) planes [25];

- FePt3 intermetallic domains: these iron particles are often adjacent to larger (8–10 nm) particles exhibiting lattice spacings of 2.72 Å, which correspond to the (110) planes of the L12-ordered FePt3 intermetallic phase (PDF № 01-071-8366) [25];

- Fe-Pt solid solutions: particles with intermediate lattice spacings (2.27 Å, 2.10 Å) confirm the presence of FCC solid solutions with varying iron content (~10 at.% to ~50 at.% Fe).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COD | Crystallography Open Database |

| CSR | Coherent Scattering Region |

| DFT | Density Functional Theory |

| EDX | Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy |

| FCC | Face-Centered Cubic |

| HRTEM | High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| ICP–OES | Inductively Coupled Plasma–Optical Emission Spectrometry |

| Pair Distribution Function | |

| SAED | Selected-Area Electron Diffraction |

| SR | Synchrotron Radiation |

| XPS | X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy |

| XRD | X-ray Diffraction |

| XRNDPh | X-ray Non-Detectable Phase |

References

- Gorbachev, E.A.; Kozlyakova, E.S.; Trusov, L.A.; Sleptsova, A.E.; Zykin, M.A.; Kazin, P.E. Design of Modern Magnetic Materials with Giant Coercivity. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2021, 90, 1287–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skomski, R.; Sellmyer, D.J. Anisotropy of Rare-Earth Magnets. J. Rare Earths 2009, 27, 675–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuz’min, M.D.; Tishin, A.M. Theory of Crystal-Field Effects in 3d-4f Intermetallic Compounds. In Handbook of Magnetic Materials; Brück, E., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 17, pp. 149–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemmer, T.; Hoydick, D.; Okumura, H.; Zhang, B.; Soffa, W.A. Magnetic Hardening and Coercivity Mechanisms in L10 Ordered FePd Ferromagnets. Scr. Metall. Mater. 1995, 33, 1793–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrobak, A. High and Ultra-High Coercive Materials in Spring-Exchange Systems—Review, Simulations and Perspective. Materials 2022, 15, 6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniak, J.; Werwiński, M. L10 FePt Thin Films with Tilted and In-Plane Magnetic Anisotropy: A First-Principles Study. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 108, 214406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisan, O.; Dan, I.; Palade, P.; Crisan, A.D.; Leca, A.; Pantelica, A. Magnetic Phase Coexistence and Hard–Soft Exchange Coupling in FePt Nanocomposite Magnets. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishina, A.; Vekilova, O.Y.; Björkman, T.; Bergman, A.; Herper, H.C.; Eriksson, O. High-Throughput and Data-Mining Approach to Predict New Rare-Earth Free Permanent Magnets. Phys. Rev. B 2020, 101, 094407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, C.; Liu, Z.; Sun, X.; Cheng, S.; Zakharov, D.N.; Hwang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Fang, J.; et al. Composition-Dependent Ordering Transformations in Pt–Fe Nanoalloys. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2117899119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunakala, S.R.; Job, V.M.; Murthy, P.V.S.N.; Nagarani, P.; Seetharaman, H.; Chowdary, B.V. In-Silico Investigation of Intratumoural Magnetic Hyperthermia for Breast Cancer Therapy Using FePt or FeCrNbB Magnetic Nanoparticles. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2023, 92, 108405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.X.; Li, C.H.; Chang, Y.C.; Huang, C.Y.F.; Chan, M.H.; Hsiao, M. Novel Monodisperse FePt Nanocomposites for T2-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Biomedical Theranostics Applications. Nanoscale Adv. 2022, 4, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, H.; Tang, W.; Kou, Y.; Sun, Y.; Dai, Z.; Zheng, X. Advances in FePt-Involved Nano-System Design and Application for Bioeffect and Biosafety. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozuyuk, U.; Suadiye, E.; Aghakhani, A.; Dogan, N.O.; Lazovic, J.; Tiryaki, M.E.; Schneider, M.; Karacakol, A.C.; Demir, S.; Richter, G.; et al. High-Performance Magnetic FePt (L10) Surface Microrollers towards Medical Imaging-Guided Endovascular Delivery Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2109741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Jang, I.; Lee, T.; Kang, Y.S.; Yoo, S.J. Overcoming Poisoning Issues in Hydrogen Fuel Cells with Face-Centered Tetragonal FePt Bimetallic Catalysts. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 207, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, Y.Z.; Wang, X.X.; Song, K.K.; Jian, X.D.; Qian, P.; Bai, Y.; Su, Y.J. Size and Stoichiometry Effect of FePt Bimetal Nanoparticle Catalyst for CO Oxidation: A DFT Study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 8706–8715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, P.; Lim, S.; Aguey-Zinsou, K.F. Superior Performance of an Iron-Platinum/Vulcan Carbon Fuel Cell Catalyst. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharov, Y.A.; Popova, A.N.; Pugachev, V.M.; Zakharov, N.S.; Tikhonova, I.N.; Russakov, D.M.; Dodonov, V.G.; Yakubik, D.G.; Ivanova, N.V.; Sadykova, L.R. Morphology and Phase Compositions of FePt and CoPt Nanoparticles Enriched with Noble Metal. Materials 2023, 16, 7312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakharov, N.S.; Tikchonova, I.N.; Zakharov, Y.A.; Popova, A.N.; Pugachev, V.M.; Russakov, D.M. Study of the Pt-Rich Nanostructured FePt and CoPt Alloys: Oddities of Phase Composition. Lett. Mater. 2022, 12, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugachev, V.M.; Zakharov, Y.A.; Popova, A.N.; Russakov, D.M.; Zakharov, N.S. Phase Transformations of the Nanostructured Iron-Platinum System upon Heating. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1749, 012036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Jiang, M.; Li, H.; Ren, Y.; Qin, G. Redetermination of the Fe–Pt Phase Diagram by Using Diffusion Couple Technique Combined with Key Alloys. Int. J. Mater. Res. 2022, 113, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Wei, L.; Wang, Y.; Kawazoe, Y.; Liang, X.; Umetsu, R.; Yodoshi, N.; Xia, W.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, C. Effect of Si Addition on the Magnetic Properties of FeNi-Based Alloys with L10 Phase through Annealing Amorphous Precursor. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 920, 166029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulska, E.; Breczko, J.; Basa, A. Multifunctional NiTiO3-decorated-rGO nanostructure for energy storage, electro- and photocatalytic applications. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2022, 128, 109310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koryam, A.A.; El-Wakeel, S.T.; Radwan, E.K.; Darwish, E.S.; Abdel Fattah, A.M. One-Step Room-Temperature Synthesis of Bimetallic Nanoscale Zero-Valent FeCo by Hydrazine Reduction: Effect of Metal Salts and Application in Contaminated Water Treatment. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 34810–34823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piminov, P.A.; Baranov, G.N.; Bogomyagkov, A.V.; Berkaev, D.E.; Borin, V.M.; Dorokhov, V.L.; Karnaev, S.E.; Kiselev, V.A.; Levichev, E.B.; Meshkov, O.I.; et al. Synchrotron Radiation Research and Application at VEPP-4. Phys. Procedia 2016, 84, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lande, J.; Webb, S.M.; Mehta, A. Area Diffraction Machine. 2008. Available online: http://code.google.com/p/areadiffractionmachine (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- PDF-2 Database; International Centre for Diffraction Data: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2011.

- Toby, B.H.; Von Dreele, R.B. GSAS-II: The Genesis of a Modern Open-Source All Purpose Crystallography Software Package. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2013, 46, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharov, Y.A.; Pugachev, V.M.; Korchuganova, K.A.; Ponomarchuk, Y.V.; Larichev, T.A. Analysis of Phase Composition and CSR Sizes in Non-Equilibrium Nanostructured Systems Fe-Co and Ni-Cu Using Diffraction Maxima Simulations in a Doublet Radiation. J. Struct. Chem. 2020, 61, 994–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 Years of Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momma, K.; Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for Three-Dimensional Visualization of Crystal, Volumetric and Morphology Data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2011, 44, 1272–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, K.A.; Waldwick, B.; Lazic, P.; Ceder, G. Prediction of Solid-Aqueous Equilibria: Scheme to Combine First-Principles Calculations of Solids with Experimental Aqueous States. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 85, 235438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, P. Dean’s Analytical Chemistry Handbook, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ginzburg, S.I. Analytical Chemistry of Platinum Metals; Israel Program for Scientific Translations: Jerusalem, Israel, 1975. [Google Scholar]

| Composite No. | Target Fe/Pt Ratio * | Platinum Precursor/ Supporting Electrolyte ** | Iron Precursor/ Supporting Electrolyte ** |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15/85 | H2[PtCl6]/HCl | FeSO4/H2SO4 |

| 2 | 15/85 | H2[PtCl6]/HCl | NH4Fe(SO4)2/HNO3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prigorodova, A.N.; Zakharov, N.S.; Pugachev, V.M.; Shmakov, A.N.; Adodin, N.S.; Russakov, D.M. Tailoring Fe-Pt Composite Nanostructures Through Iron Precursor Selection in Aqueous Low-Temperature Synthesis. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9110616

Prigorodova AN, Zakharov NS, Pugachev VM, Shmakov AN, Adodin NS, Russakov DM. Tailoring Fe-Pt Composite Nanostructures Through Iron Precursor Selection in Aqueous Low-Temperature Synthesis. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(11):616. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9110616

Chicago/Turabian StylePrigorodova, Anna N., Nikita S. Zakharov, Valery M. Pugachev, Alexander N. Shmakov, Nickolay S. Adodin, and Dmitry M. Russakov. 2025. "Tailoring Fe-Pt Composite Nanostructures Through Iron Precursor Selection in Aqueous Low-Temperature Synthesis" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 11: 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9110616

APA StylePrigorodova, A. N., Zakharov, N. S., Pugachev, V. M., Shmakov, A. N., Adodin, N. S., & Russakov, D. M. (2025). Tailoring Fe-Pt Composite Nanostructures Through Iron Precursor Selection in Aqueous Low-Temperature Synthesis. Journal of Composites Science, 9(11), 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9110616