1. Introduction

Lattice structures are defined in the literature as objects that are periodic in nature, consisting of continuously repeating unit cells that interconnect in three dimensions. They are typically created from truss structures, as well as minimalistic or basic surfaces [

1,

2,

3]. One of the main advantages of a lattice structure is the possibility of varying the geometry and density of the lattice, thereby optimizing parts for stiffness, strength, or flexibility while minimizing mass. Lattice structures are widely used for energy absorbers [

4,

5,

6,

7], acoustic and vibrational dampers [

8,

9,

10], mechanical structure optimization [

11,

12], heaters and exchangers [

13,

14], biomedical implants [

15,

16], and electrochemical devices [

17,

18]. The frequent use of these design methodologies is linked to additive manufacturing (AM) developments. In fact, these techniques are crucial for creating complicated mechanical parts using lattice structures [

19,

20].

Lattice-structured materials exhibit interconnected, complex, and variable pore structures, along with highly specific surfaces. The correct design of structures with lattice infills can lead to significant weight reductions in the parts or even the development of re-engineered materials with customized macroscopic properties [

21]. According to the arrangement of units, they can be divided into two-dimensional lattice structures and three-dimensional lattice structures.

Two-dimensional lattice structures consist of an arrangement with basic polygonal units, which can be extended in the third dimension to form a three-dimensional solid structure. Three-dimensional lattice structures, on the other hand, are created with a spatial repetition in the three directions; they can be divided into two main categories: strut-based lattices (cubic, octet-truss, face-centered cubic, etc.) [

22], and surface-based lattices and the triple periodic lattice structure, or TPMS (Schwartz, Gyroid, Fisher Koch, etc.) [

23]. Three-dimensional lattice structures significantly enhance the specific stiffness and strength of porous materials compared to two-dimensional lattice structures, offering a greater design ability [

24,

25].

In this work, attention is given to the surface-based lattice structure, and the goal is to find a new family of lattice structures with improved performance in terms of material budget compared to the well-known lattice structures, such as the Gyroid and Schwartz. Two interpretations of the material budget are considered; the first is a concept central to particle accelerator design, particularly in quantifying the amount of material a particle passes through, expressed in terms of the material’s effect on the particle. This quantity depends on the radiation length of the material, which is the mean length required to reduce the energy of an electron by a factor of 1/e. The higher the material budget, the higher the energy losses. The second interpretation is a financial plan that details the quantity and cost of raw materials a company needs to purchase to meet its production goals for a specific period. It is a key component of a company’s overall budget, considering factors like production schedules, current inventory levels, material costs, and inventory management policies. The purpose is to ensure the right amount of materials is available for production, manage costs, and optimize inventory levels. In this case, we will refer to the material budget as the quantity of material (i.e., its mass or volume), preferring, however, to reserve the noun ‘budget’ to emphasize its economic significance. This tendency can be found in several scientific papers.

The idea is, therefore, to link savings in terms of material budget to the use of minimal surfaces. In geometry, a minimal surface is a surface that locally minimizes its area. This is equivalent to having zero mean curvature (the algebraic mean between the maximum and minimum curvatures).

In recent decades, different approaches have been used to create this type of lattice structures: the implicit method, where a TPMS can be described by a single-valued function of three variables consisting of trigonometric functions, and explicit method, an explicitly constructed surface patch is evolved iteratively by minimizing surface area, subject to the boundary constraints that ensure the periodic compositionality of patches. The reason why different methods are investigated with respect to the implicit approach is that the implicit functions are known only for a few TPMS. A novel approach, for example, was proposed by Y. Xu et al. [

26], which combines the advantages of both implicit methods and explicit methods by explicitly specifying flexible periodic boundaries and implicitly computing minimal surfaces adhering to these boundaries.

The scope of this work is to create an ad hoc family of cells based on a specific starting geometry and boundary conditions, compare the different cells using a particular comparison criterion, and utilize the best cells as infill for mechanical structures. The main problem in the synthesis of new and different minimal surfaces is the need to solve a complex differential problem that imposes the characteristic of minimality. Considering this, we proposed a different approach for creating a surface-based lattice using an iterative particle-spring dynamic model, which is employed to generate the lattice, taking into account symmetrical requirements related to boundary conditions. The proposed methodology enables us to find the minimal surface configuration through an iterative step of equilibrium, resolving the dynamics of a stretched membrane. In structural mechanics, a membrane cannot bear moments but only normal stresses and this intrinsically leads to finding an equilibrium with interpolating surfaces with zero mean curvature. As equilibrating forces, we use the sum of the forces dictated by the objective function and the reaction forces to ensure that the boundary conditions are respected. Once the boundary conditions on the displacements and the applied stretching level have been imposed, equilibrium causes the structure to evolve toward a minimum-surface equilibrium state. The need for a dynamic rather than a directly static solution is related to the greater ease of convergence given the large displacements expected. The novelty of this approach lies in the possibility of starting from a generic initial geometry and choosing an ad hoc comparison criterion to select the best lattice generated without resolving the differential partial equation or knowing the exact minimal surface equation. In this case, the performance of the lattice is based on the concept of material budget, as described in the following sections. The paper is organized as follows. In the first part, the algorithm for generating the minimal surface lattice is presented. Then, the comparative strategy and the results are reported, with the following workflow validation. After the best cell identification, the experiment tests are described, as well as the results obtained and the comparison with the finite element analysis. In the concluding section, we have also briefly discussed a practical application of the proposed methodology, which resulted in a material budget savings in an industrial case study.

2. Methods

In this section, the minimal surface lattice generation workflow is described; the fundamental requirement is to create a procedure adaptable to different starting geometries and boundary conditions, capable of generating a final lattice cell based on a minimal surface.

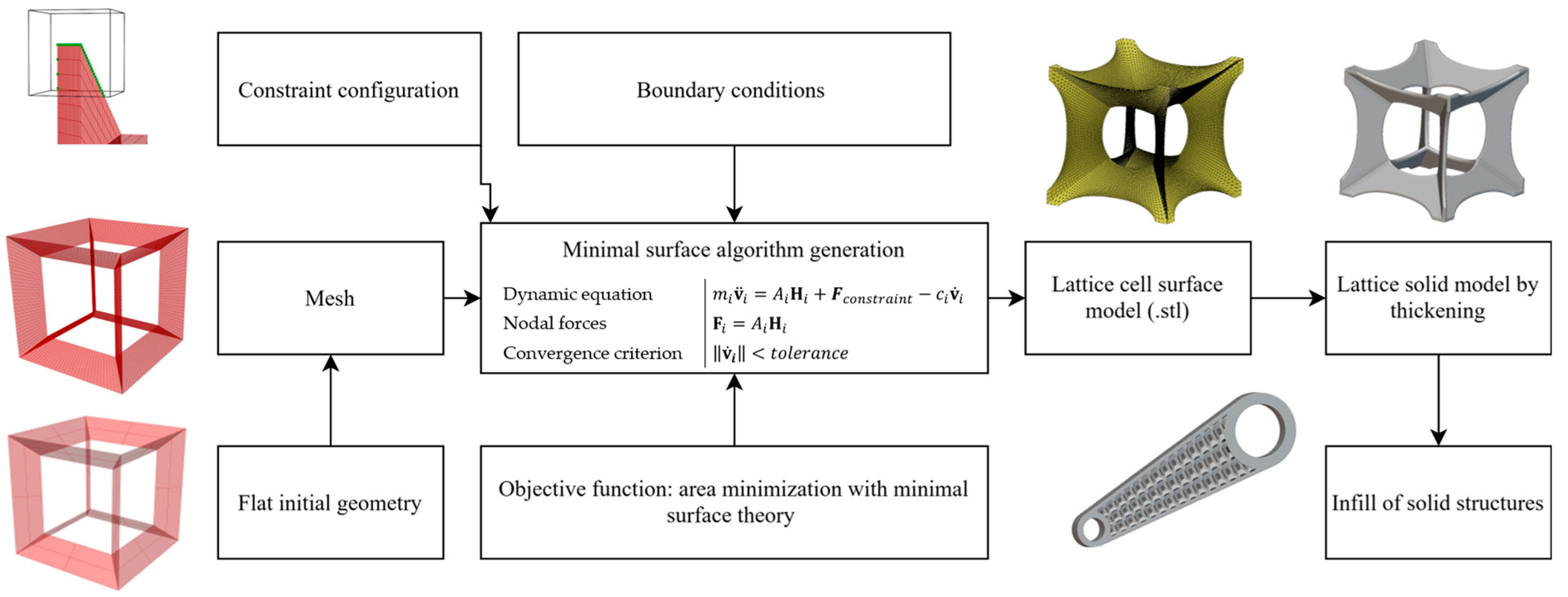

The minimal surface generation workflow can be summarized in the scheme reported in

Figure 1. This workflow can be generalized and applied to various simulation environments.

From the initial geometry, imposing the boundary conditions and applying the algorithm described in

Section 2.1, the initial flat geometries, discretized creating a mesh, are subjected to the applied stretching forces, which move the mesh nodes according to the objective function, the area minimization, achieving a minimal surface lattice, congruent with the constraint configurations. When the equilibrium is reached, the cell is created as a surface model (.stl), and after assigning the thickness, the thin lattice can be generated.

The generated cells can be mechanically characterized using homogenization, which enables the calculation of the stiffness matrix for each cell, allowing for successive comparison.

The same homogenization method was applied to create a Gyroid cell and a Schwartz cell, yielding their respective stiffness matrices. The final step of the lattice generation is to check the mean curvature and ensure that the obtained lattice respects the minimal surface requirements, thereby validating the workflow.

2.1. Mathematical Formulation

The main idea is to create the minimal surface lattice without resolving geometrical differential equations (Equation (1)), but resolving a dynamic system of equations (Equation (2)). The general equation for the fulfillment of the minimality for a surface

in the parametric form (i.e.,

) is:

The solution to Equation (1) [

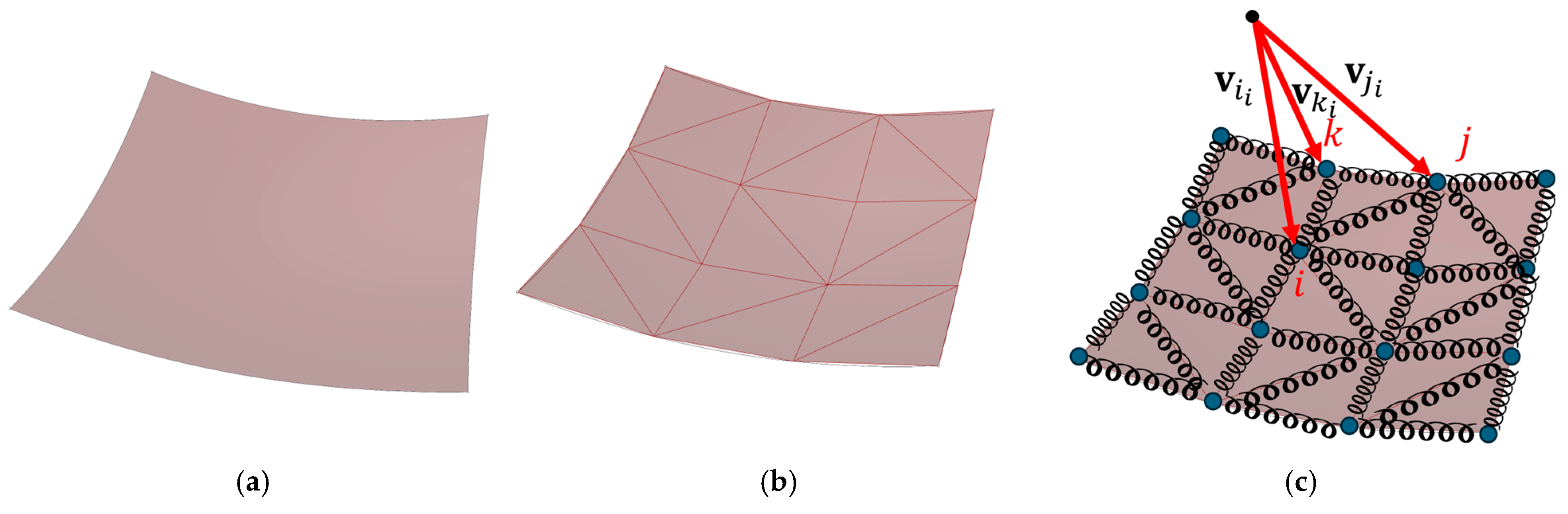

27] is very challenging, and it is only possible to achieve closed-form results for a limited number of cases. In order to explore a wider set of solutions, we proposed a different approach. Let us start by considering a first-attempt surface that does not meet the conditions of minimality. We consider it as a membrane subjected only to tangential forces at the boundary edges. This means that the initial condition will not be in equilibrium, but the surface will have to evolve to reach a configuration in which the external boundary forces are balanced exclusively by normal stresses inside the membrane (stretching force). Since our goal is to achieve a geometric equilibrium configuration, rather than accurately estimating deformations and stresses in the structure, we decided to decompose the surface using a discretization of nodes with concentrated mass, connected by elastic springs (

Figure 2).

The dynamic equilibrium of this lumped parameter system can be written as Equation (2):

where:

(u,v): parametric coordinate in a planar domain U.

f = f(u,v): parametric surface as a function of and parameters.

: nodal mass.

c: damping coefficient.

: nodal spring forces.

: nodal acceleration.

: nodal velocity.

Forces are incrementally applied, calculated from the area gradient, until the equilibrium is reached according to the equilibrium condition. The dynamic equation is used to optimize the starting mesh. The equilibrium condition is reached when the nodal velocities are below a threshold (Equation (3)):

The function to optimize is the area of the triangular mesh, defined by Equation (4), which is the sum of the areas of each triangle. This can be expressed as reported in Equation (5), corresponding to the energy function optimized by the algorithm.

where:

: total mesh area.

: is the vertex vector n-th of the i-th triangle.

is the i-th triangle area.

: index of the three triangle vertices.

For the area reduction, the

n-th vertex of each triangle is subjected to a force, expressed by Equation (6). Using Equations (4) and (5), the forces can be calculated as reported in Equations (7)–(9).

where:

The stiffness

can be chosen independently of structural considerations, but only of convergence, and in this case, it was assumed to be equal to 1. The

k is selected as 1 to simplify the algorithm, and it does not influence the final lattice, but only the iterative steps. The parameter

only affects the evolution of the dynamics and not its final state, and for our simulation, it is assumed to be 0.9; the sensitivity analysis of the simulation in function of

c is discussed in

Section 3.

Considering Equation (10) [

28,

29] for the discrete mean curvature, it has been demonstrated that the area derivative with respect to the vertex position is proportional to the discrete mean curvature, as reported in Equation (11).

where:

: discrete mean curvature vector.

: set of vertices adjacent to vertex i.

, : opposite angle to the i–j segment in the two adjacent triangles (i, j, k) and (i, j, m); in other words, the angle in vertex k and vertex m.

is the participating area to the vertex i, which can be simplified as one-third of the element area.

Considering Equation (6) and Equation (11),

can be expressed as a function of the

and

(Equation (12)). At this point, the dynamic equation can be formulated as reported in Equation (13).

The terms in regulate the tension between the vertex i and j, and the direction of reflect the direction of the force In conclusion, the terms are responsible for the vertex movement during local area reduction: regions with positive mean curvature will be contracted, while those with negative mean curvature will be expanded. At the equilibrium, the minimal energy configuration is reached.

2.2. Initial Geometry and Boundary Conditions

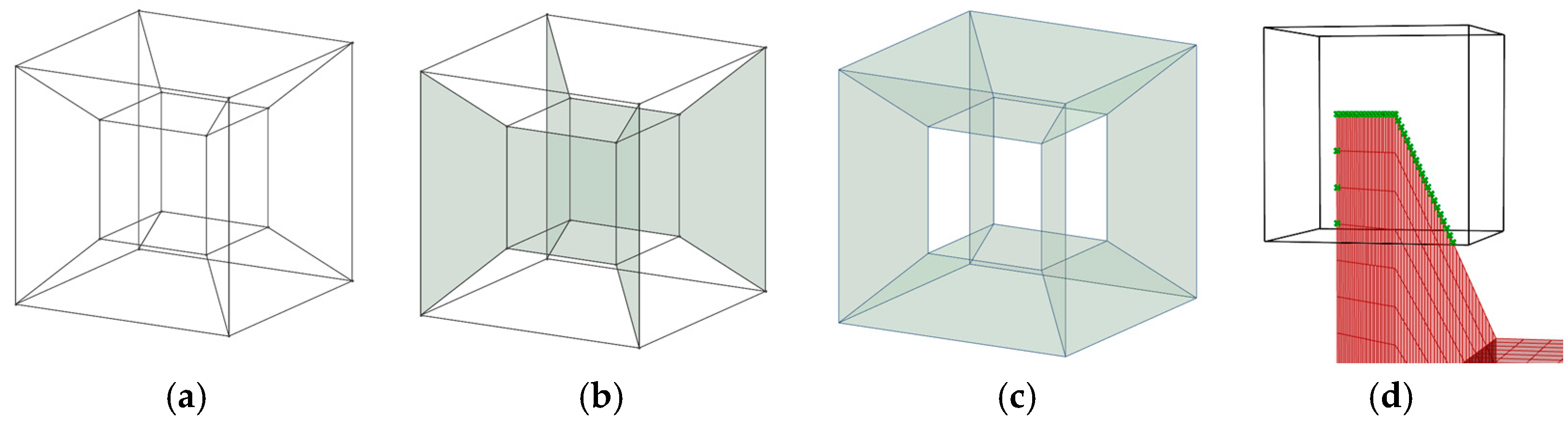

The initial geometry considered is the hypercube; it was chosen for its fractal geometry, which allows the creation of different starting frameworks for minimal surface generation, and because it can be easily parameterized, facilitating the study of various configurations. A cubic geometry was chosen to apply the border conditions easily, to homogenize the cell, and to facilitate comparison with well-known surface lattice structures, such as the Gyroid and Schwartz. This choice also efficiently guarantees the cell arrangement along the three directions.

From the hypercube framework (

Figure 3a), two different starting scenarios have been considered: a configuration with two specular face groups (

Figure 3b) and a configuration with all faces that connect the internal cube to the external one (

Figure 3c). These initial frameworks are used in this work to generate the minimal surface lattice structure, applying the described workflow.

The boundary conditions are crucial for the lattice creation; two configurations are created considering two requirements: the necessity to guarantee a proper interface between adjacent cells and the will to analyze two different scenarios, one with the internal cube free to evolve (S2) with the mesh and one with the internal cube edges fixed (S1). The first necessity has been fulfilled by applying boundary conditions to each external cube corner (

Figure 3d), creating the interface for the cell repetition, and the second by applying a boundary condition to the internal cube only for the S1 configuration. In this way, the lattice generation scenarios are ten, created by five different initial geometries and two anchoring point configurations.

2.3. Minimal Surface Comparison

After lattice generation, it is essential to focus on the research aim, properly define the comparison parameters to select the best cells, and compare the created cell with the Gyroid and Schwartz. The main characteristic is the cell material budget performance. The material budget is a concept central to many structural designs, due to its general relevance. The identification of lattice structures with better performance in terms of material budget is central, but it is also essential to consider in parallel the stress intensification and the comparison between the flat starting geometries and the obtained minimal surface lattices. The stress intensification analysis is needed to ensure that the obtained lattice does not present criticalities that can compromise the usability of the cell; the comparison with the flat starting geometry is required to justify the entire workflow, demonstrating that the minimal surface lattice obtained has better performances with respect to the flat geometry, before the workflow application.

The material budget for a lattice structure can be defined as proportional to the lattice surface; in fact, considering Equation (14), with the material density and thickness constant, it is proportional to the surface area.

where:

: mass of the structure.

: mass of the i-th cell.

: material density.

: lattice thickness.

: surface area of the i-th cell.

In the comparison process, the structural resistance of the lattice has been considered, using the ratio between the minimum stiffness modulus (

E) obtained by homogenization and the surface area (

S) of the lattice (Equation (15)). The higher the ratio, the higher the performance of the lattice cell in terms of material budget, considering the mechanical resistance.

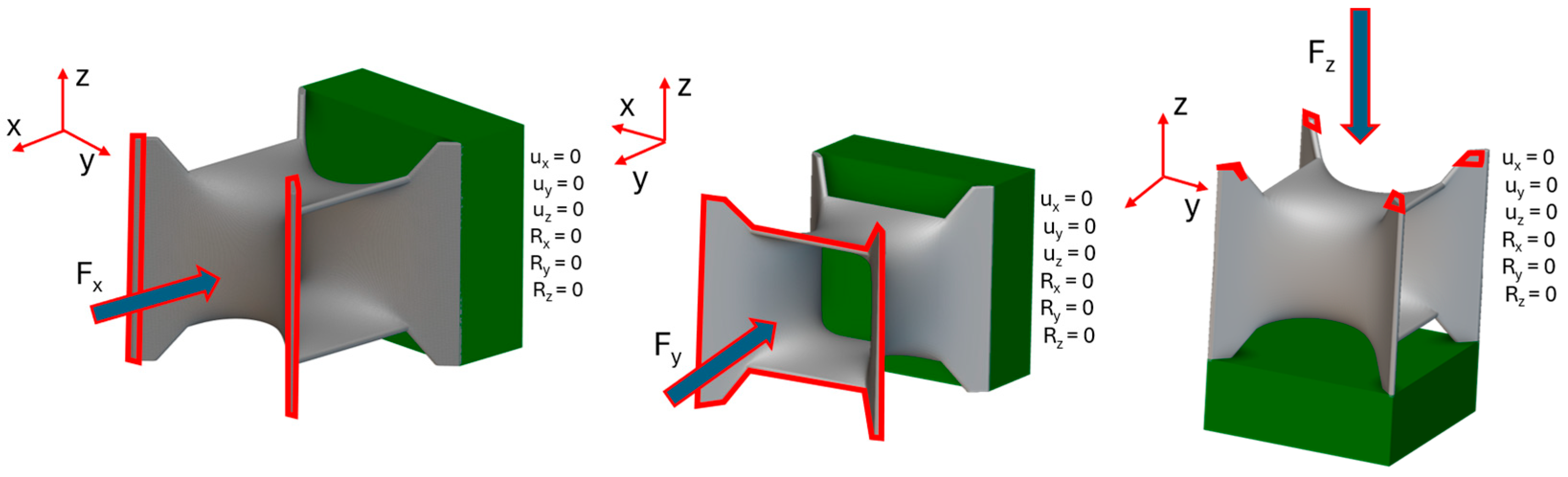

For the stress intensification evaluation, two different structural analyses were performed for each cell: a single-cell analysis with a dimension of 30 mm and a 3 × 3 × 3 structure analysis with a dimension of 90 mm, to consider the interface between adjacent cells. The used load and constraint configurations are reported in

Table 1 for the single cell and in

Table 2 for the 3 × 3 × 3 structure.

The constraint and forces application is similar to the scheme reported in

Figure 4 for both the single-cell and 3 × 3 × 3 structure.

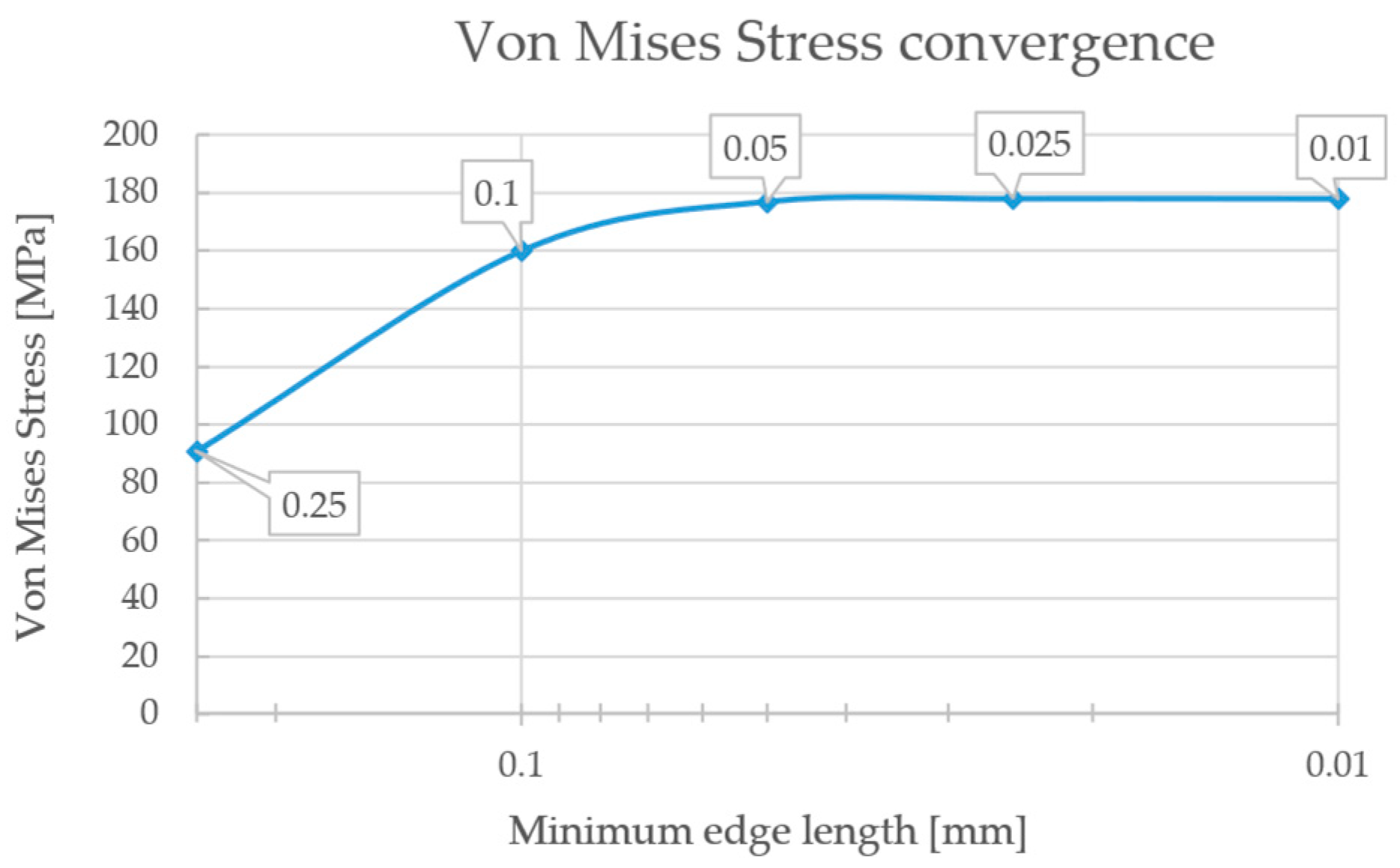

Before the analysis, a mesh convergence analysis was performed, designing 0.025 mm as a minimum edge length (

Figure 5). For the last comparison factor, to ensure the efficiency of the approach with respect to the use of flat geometries, flat models were created, starting from the initial geometries used for the cell generation, assigning a thickness and characterizing the flat cell with homogenization, to calculate the stiffness matrices and the surfaces for the comparison.

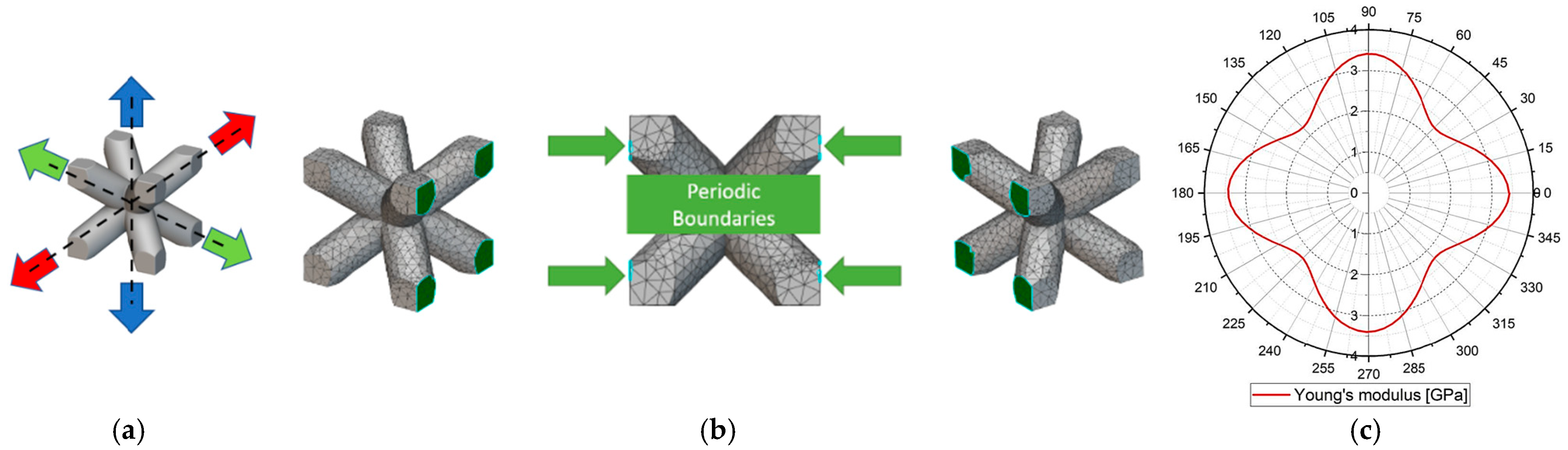

Homogenization [

30] is a technique for replacing a complex lattice with an equivalent continuum by averaging its micro-scale behavior, using a representative volume element (RVE), that is large enough to capture the lattice’s periodic features, and applying boundary conditions to obtain effective stiffness. In this case, periodic conditions have been used to ensure a spatial seamless infill. Defining

as a bulk material, the general stiffness matrix, the scope is to find an equivalent stiffness matrix

, to replace the lattice with a continuum material with the elastic equivalent characteristics of the lattice. Six independent unitary strain loads are applied (

Figure 6a), three normal strains and three shear strains, under periodic boundary conditions (PBCs) (

Figure 6b).

The microscale displacement field

is composed of a uniform displacement and a fluctuation field. The uniform displacement represents the displacement considering the RVE as a solid homogeneous block; the fluctuation field represents all local deviations caused by the lattice geometry (Equation (16)).

where:

: displacement field inside the RVE.

: macroscopic strain tensor applied to RVE.

: microscale deviation from affine deformation.

The fluctuations are calculated imposing the PBCs: opposite faces of the RVE present the same fluctuation displacement and opposite tractions. These conditions are based on the Hill-Mandel macro homogeneity principle that affirms that the microscopic virtual work is equal to the macroscopic one. Imposing the periodicity, the fluctuation field is null; therefore, the macroscopic strain

is representative of the entire RVE. The fluctuation field

is calculated as the equilibrium response of the lattice in answer to the imposed macro-strain. At this point the displacement field

is known, and the microscale stress and strain can be calculated as reported in Equations (17) and (18).

where:

The macroscopic stress is obtained as a volume average of microscale stress, as reported in Equation (19).

At this point, to calculate di,

can be applied to the RVE the six independent unitary strain loads. For each of the

k-th load condition, Equation (20) is valid, and considering the unitary of the load,

is directly populated by the averaged stress vectors.

The effective stiffness matrix

can be used to define a bulk material equivalent to the lattice structure, without meshing and modeling each cell of the lattice. The calculated components of the

C are used to create the polar diagram, which is the graphic representation of the modulus as a function of the direction with respect to the center of the mass. A 2-D representation is reported in

Figure 6c; this gives a straightforward representation of the stiffness modulus variation at different orientations.

3. Results

For this study, the single-cell characteristics are reported in

Table 3; none of these parameters affects the generalization of the workflow.

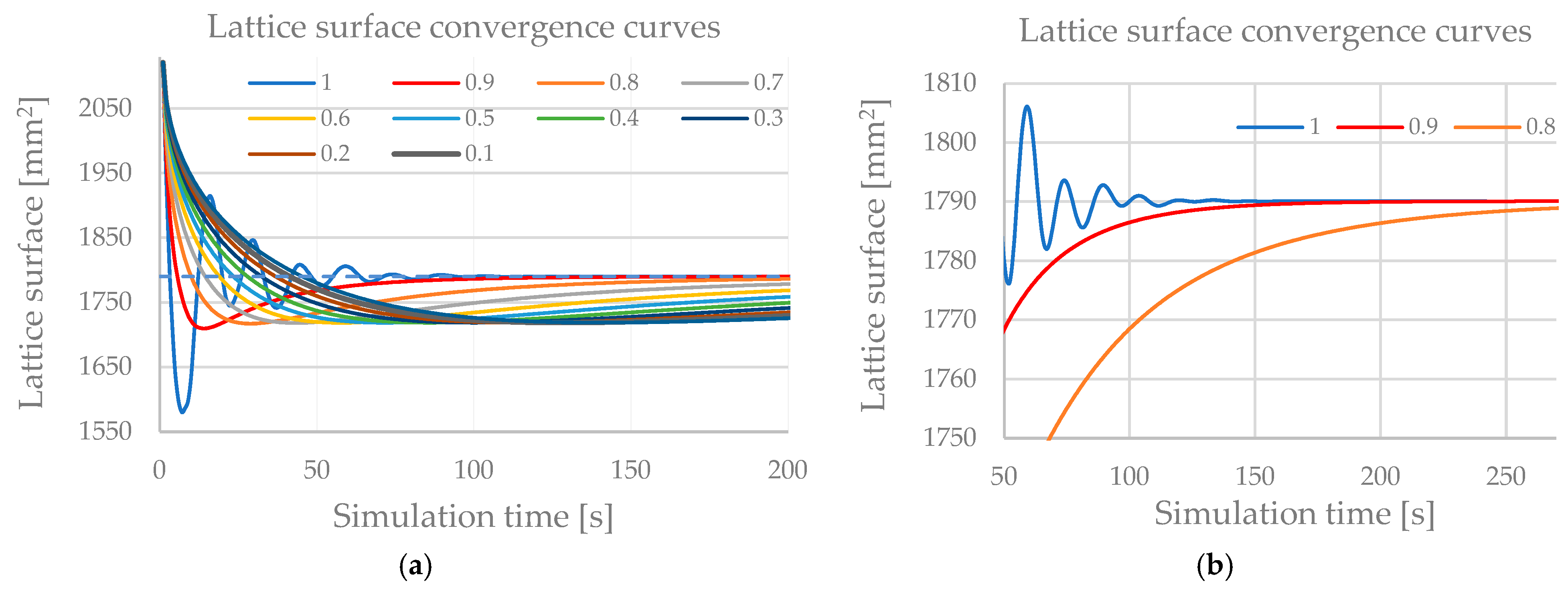

The workflow described in

Section 2 requires the evaluation of the damping parameter

c, which influences the convergence time of the simulation. For this reason, a sensitivity analysis of the convergence time as a function of

c has been conducted, and the best results have been obtained using a value of 0.9 as damping, which guarantees the fastest convergence time while maintaining good model stability (

Figure 7).

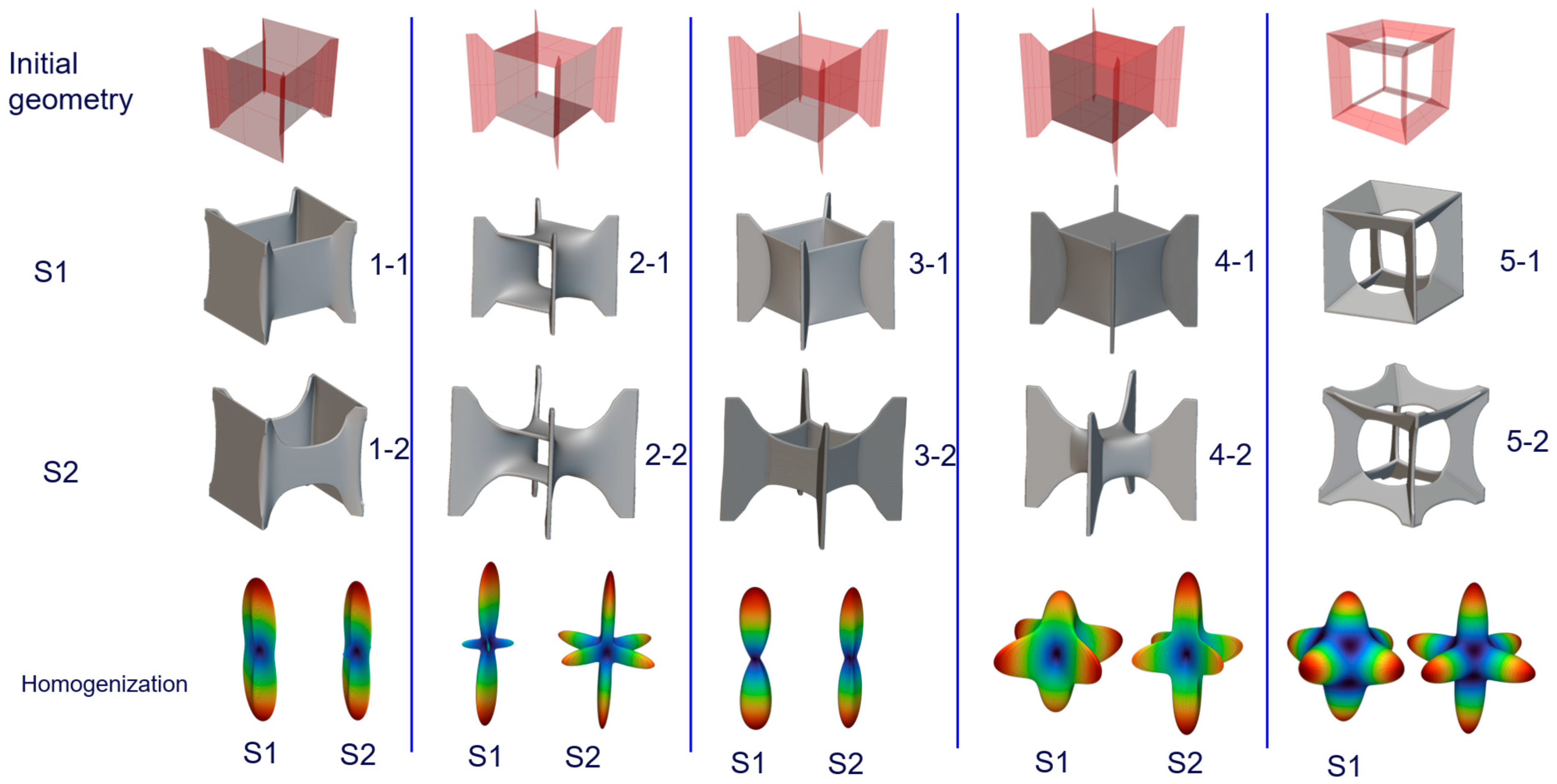

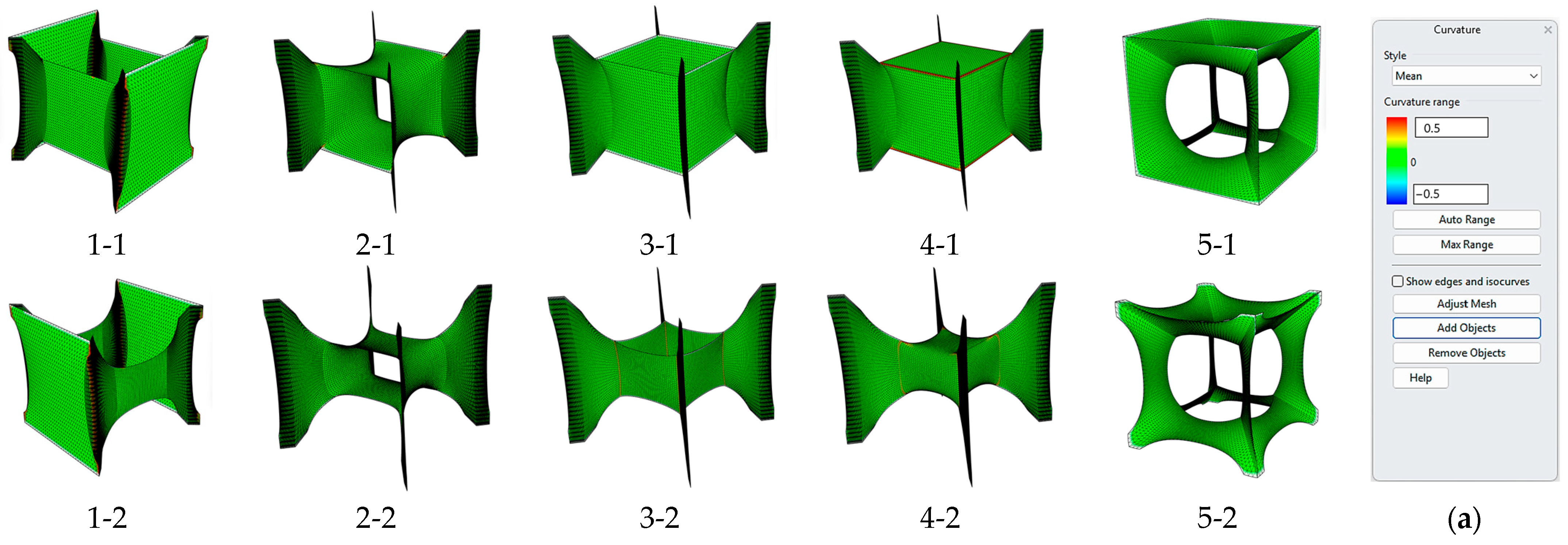

Applying the workflow described using the dimension reported in

Table 3, it is possible to create ten different lattice cells (

Figure 8—line 2, 3), considering five initial geometries (

Figure 8—line 1) and two constraint configurations. For each configuration, the mean simulation time is about 85 s, using a laptop with Intel

® Core™ i7-9750H and 16 GB of RAM.

In this section, the comparison step described in

Section 2 is detailed. The first control regards the curvature, to check if the obtained cells are minimal surfaces proving the success of the workflow.

A curvature analysis was performed on the obtained lattices (

Figure 9), highlighting a global zero mean curvature and some very localized areas with non-zero mean curvature, which will be verified during the stress intensification analysis.

The material used for the analysis is a photo-polymeric resin, a similar material will be used in experimental tests. The main resin properties are reported in

Table 4. From the homogenization, it is possible to calculate the Young’s modulus of each cell, to create the polar diagram (

Figure 8—row 4) and to calculate the

E/

S ratio, needed for the material budget performances. The results are reported in

Table 5, with the weight and surface of each cell.

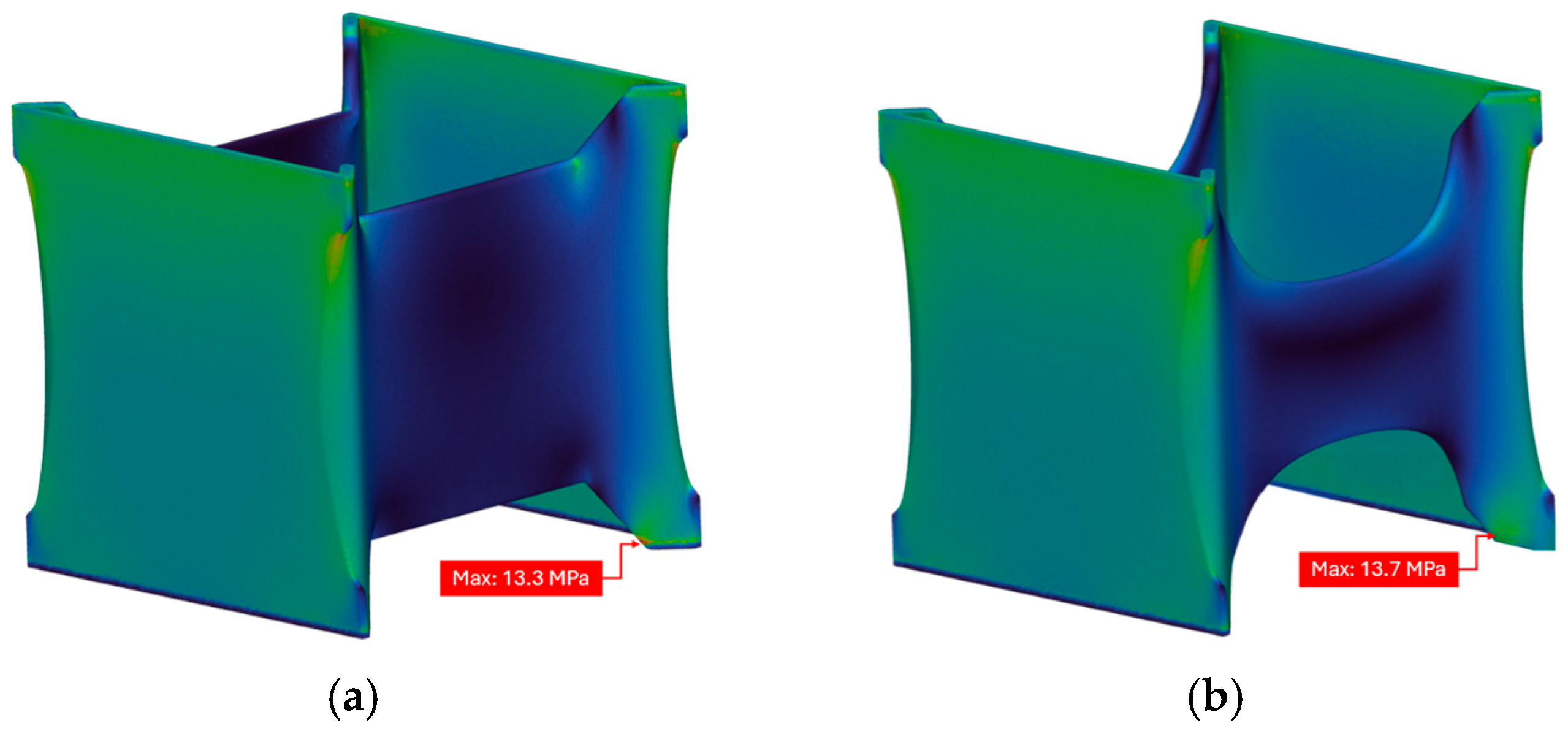

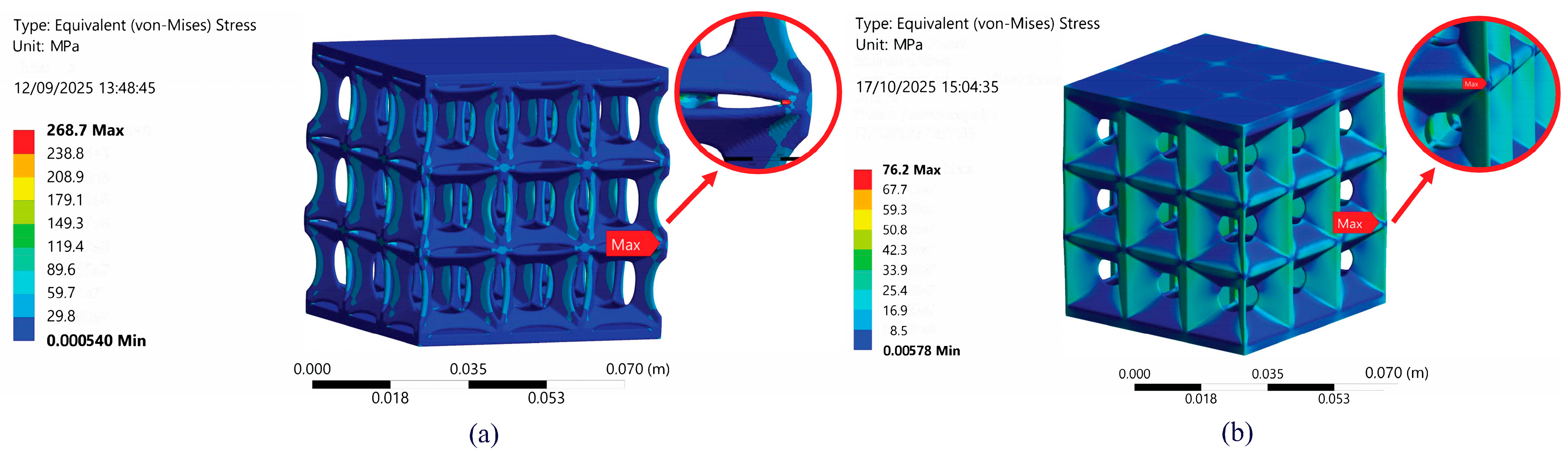

The second step, as previously described, involves stress intensification analysis for both the single cell and the 3 × 3 × 3 structure. The two more suitable cells for each scenario are reported in

Table 6, where the choice criterion is the cell with the lower Von Mises maximum stress under the imposed loads.

The regions where the maximum stress is localized are reported in

Figure 10.

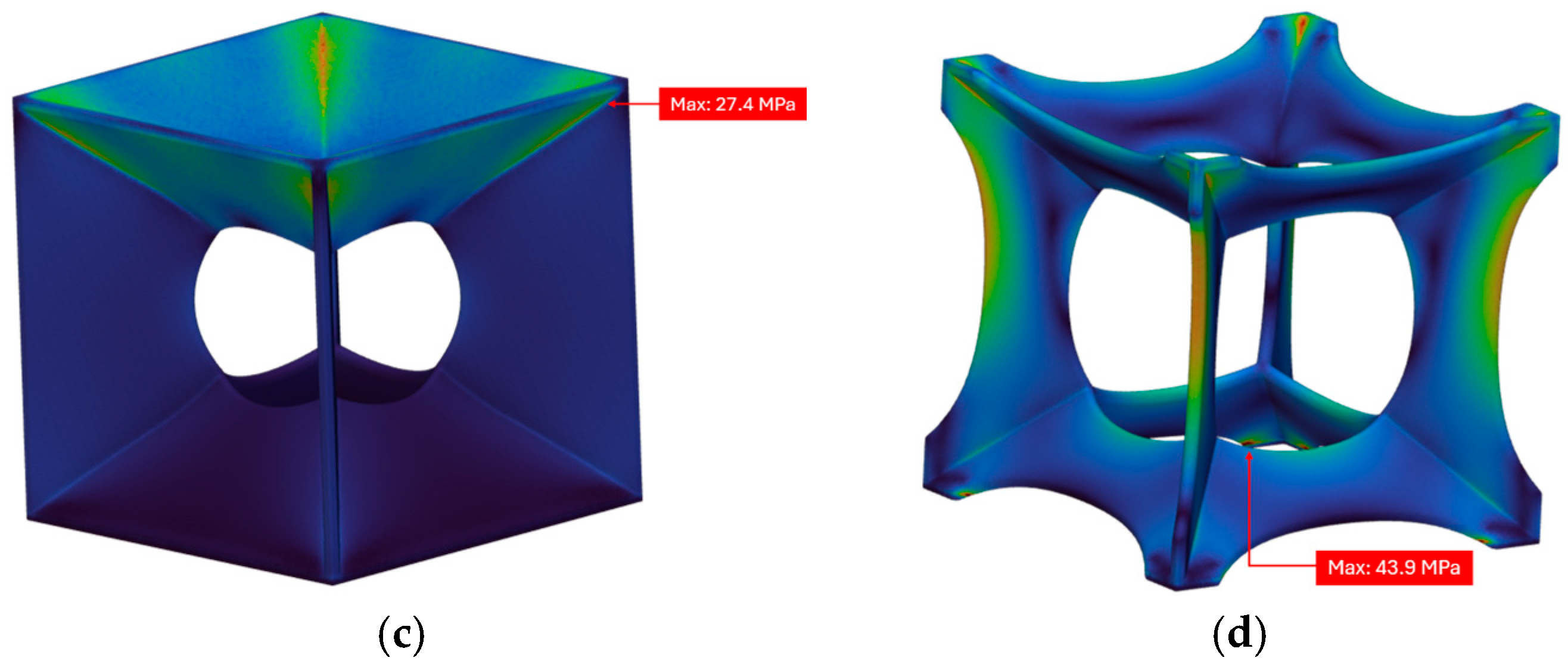

At this point, the lattices that emerged from the comparison can be compared with the flat structure created from the starting geometries without applying the described algorithm for minimal surface generation. Flat structures have been created for the starting geometries 1 and 5 and are reported in

Figure 11.

The comparison shows an increase in the E/S ratio of 77% for cell 1-1, 436% for cell 1-2, 23% for cell 5-1, and 7% for cell 5-2. In all cases, the workflow for generating the minimal surface achieved better results compared to the flat structure. At this point, it is necessary to select the two best-performing lattices that can be used for experimental testing and further studies. The 5-1 cell presents the best evaluation in terms of material budget and stress intensification; therefore, it can be considered the first choice for further study.

Regarding the second cell in terms of material budget, the 5-2 presents a lower contribution; in terms of stress distribution, it is the best for the load along the x-axis and y-axis, but the cells 1-1 and 1-2 are better along the z-axis. Cell 1-1 for the single cell stress intensification is 37% better than 5-2, and 1-2 for the 3 × 3 × 3 cell stress intensification is 60% better than 5-2, but in terms of material budget (E/S ratio), 5-2 is 70% better than 1-1 and 500% better than 1-2.

In conclusion, the two cells used for further studies are 5-1 and 5-2. These two cells have a better E/S ratio compared to the flat-cell, respectively, at 23% and 7%. This means that the application of the algorithm with the minimal surface is justified because it allows for obtaining better performance in terms of stiffness for the surface unit, the parameter that considers the material budget contribution. The lattice 5-1, in terms of material budget, considering the E/S ratio, is better than the Gyroid by a factor of 2.3 and Schwartz by a factor of 1.7; the lattice 5-2 is better than Schwartz by a factor of 1.4 and equal to the Gyroid.

Relative Dimension Factor Analysis for Further Optimization

The comparison was conducted using different initial geometries and constraint configurations, but the relative dimensions between the internal cube and the external one were kept constant. This further study aims to analyze different configurations in terms of relative cube dimensions, optimizing the cells. The cell cube remains unchanged (30 mm × 30 mm × 30 mm); the internal cube is created by introducing the relative dimension factor (

RDF), defined in Equation (21). This value influences the entire internal frame, particularly the length of the internal connection between the external cube and the internal one.

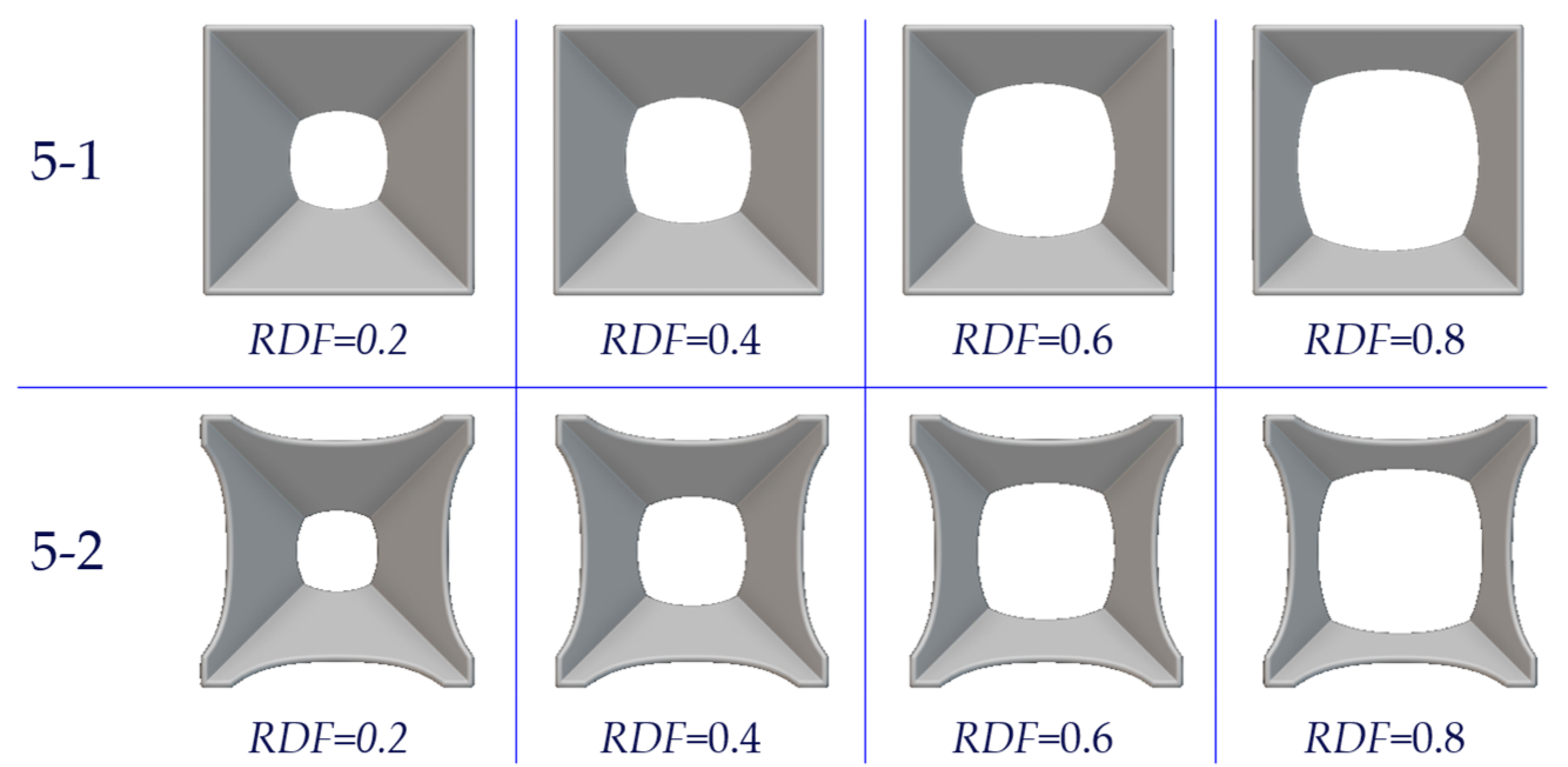

The

RDF was varied from 0.2 to 0.8, with a step of 0.2, creating four different scenarios, reported in

Table 7 and in

Figure 12.

The best configurations in terms of E/S ratio for the material budget performance are RDF = 0.2 for lattice 5-1 and RDF = 0.4 for lattice 5-2. The chosen RDF configuration is used in an experimental test for creating specimens.

4. Experimental Testing

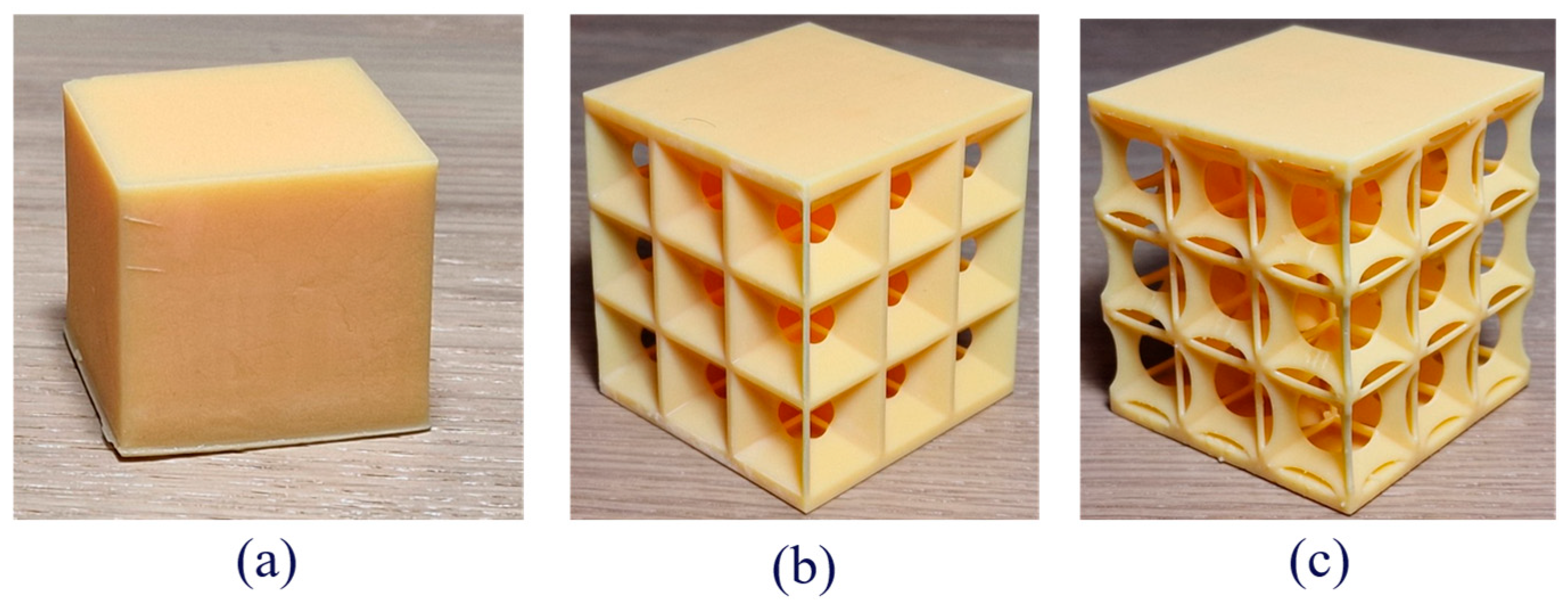

The experimental tests of fabricated specimens are fundamental for verifying the quality of the finite element simulation and understanding the actual behavior of the cell. The specimens have been subjected to compression testing.

With this purpose, three different pieces were fabricated for each of the three specimen types: the solid cube, the lattice cell 5-1, and the lattice cell 5-2. The solid cube is necessary for the material characterization in terms of Young’s modulus. Following the experimental test, finite element analyses were performed for comparison.

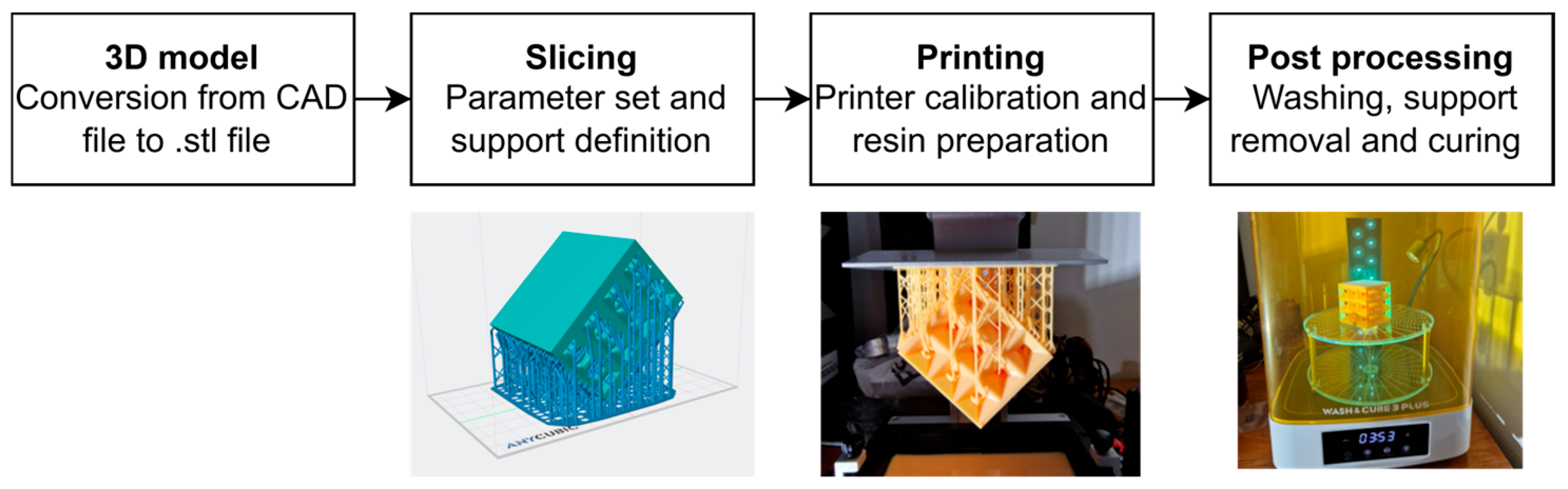

4.1. Specimens Fabrication

The stereolithography (SLA) has been used for the fabrication of the specimens; the general workflow is reported in

Figure 13.

The process begins by converting the CAD model into a .stl file, which is required for slicing. In the slicer, the parameters for the slicing were set, in particular, the resin type, the layer thickness, the normal exposure time, the bottom exposure time, and the number of bottom layers; all the parameters are reported in

Table 8. The washing follows the printing phase, to remove excess resin and prepare the model for the final phase, the curing, where the specimens are exposed to UV light, diffused and localized, to ensure the final resistance. The washing and curing have been performed using a washing-curing machine, creating a repeatable process for each specimen. The washing and curing time are reported in

Table 8. The fabricated specimens are shown in

Figure 14.

4.2. Compression Test Setup

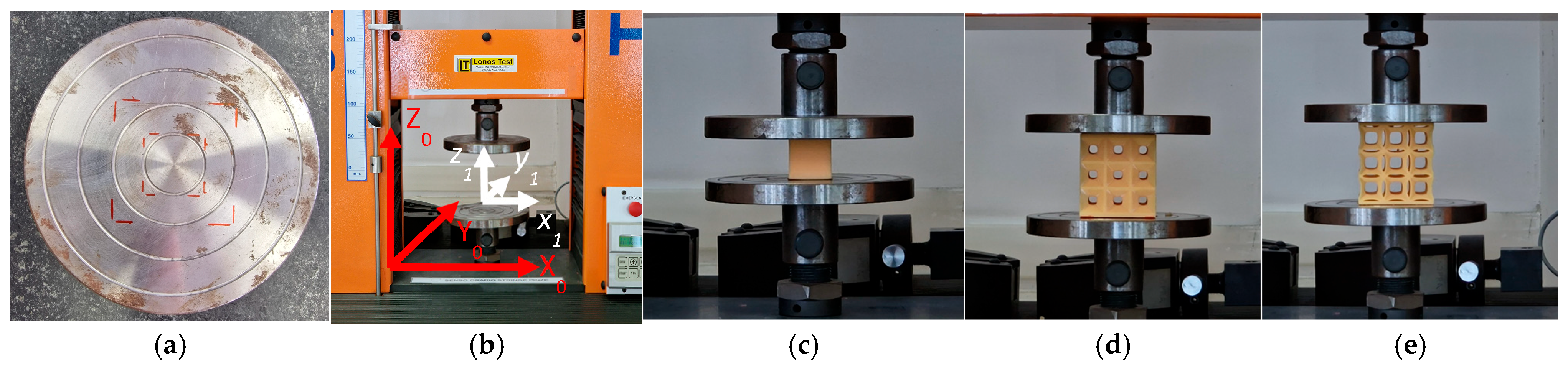

Compression tests were performed using a testing machine, Lonos Test TT5000, with a cell load of 25 kN, and with a test velocity of 0.05 mm/min; each test was repeated three times using different specimens, creating three curves force–displacement for each of the models: the cube, 5-1 lattice, and 5-2 lattice.

Centering is crucial for a good compression test. The head plate has different circles machined to create a reference for the specimens’ disposal. In order to develop a congruent alignment for each specimen, a frame was made on the plate, creating the initial position for the cube test and for the lattice cell tests. To create a reproducible test, all specimens were positioned using the same reference, based on the printing position.

Regarding the sample size, we considered a 3 × 3 × 3 cell. This means that there is an internal 2 × 2 × 2 cell not in contact with the border loads; therefore, it is representative of the behavior of the structure. Furthermore, we performed three tests for each specimen with a high correlation, which highlights the repeatability of the tests and, therefore, sufficient statistical significance.

4.3. Test Result and Finite Element Model Comparison

Each test was repeated three times using different specimens, creating three curves of force–displacement for each of the models: the cube, 5-1 lattice, and 5-2 lattice.

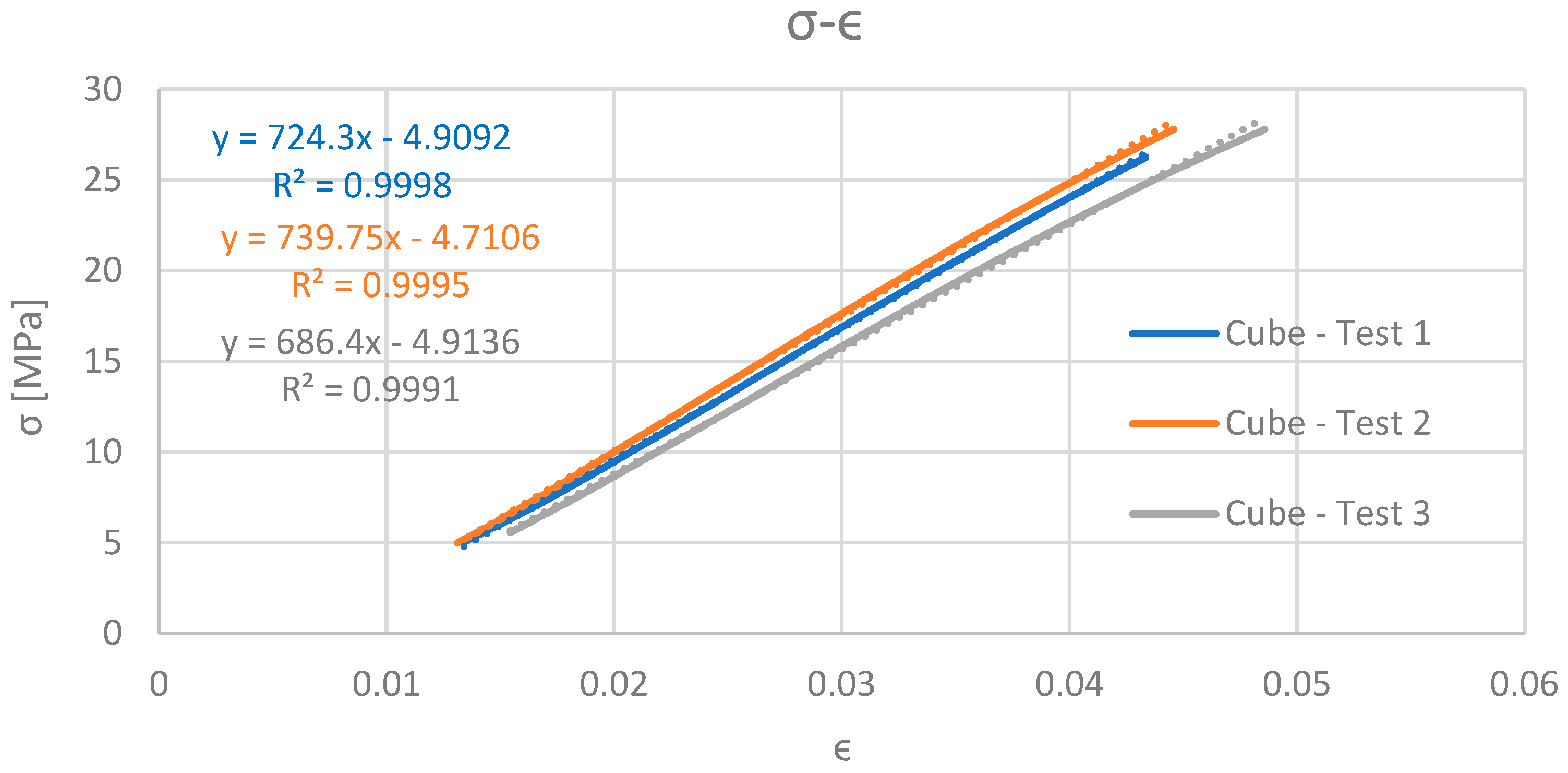

From the solid cube test (

Figure 15c), the Young’s modulus was calculated; in

Figure 14, the three curves from the solid cube test are reported. From the analysis of the linear part, applying the linear regression, it is possible to calculate the Young’s modulus, which is 0.7 GPa. The linear regression for all three cases has R

2 higher than 0.99 (

Figure 16).

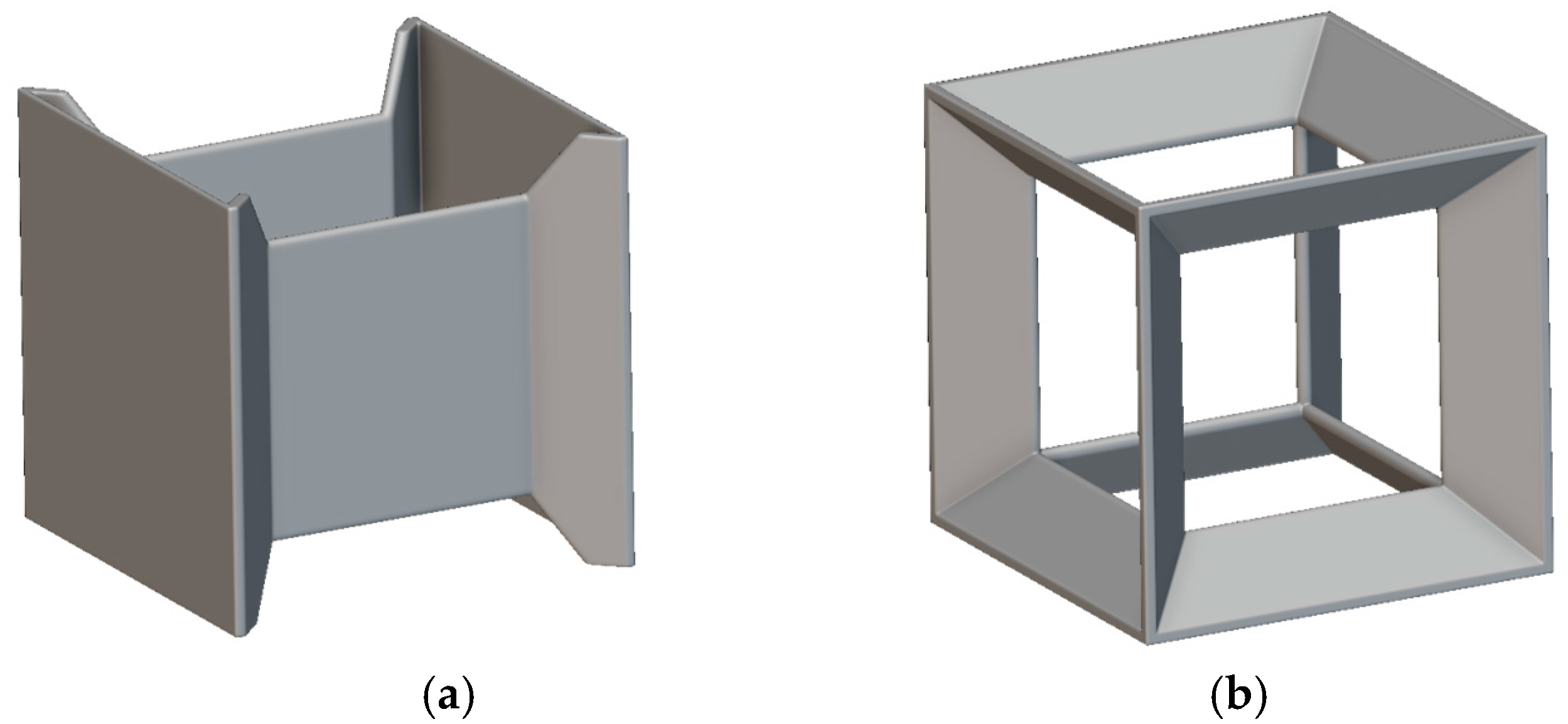

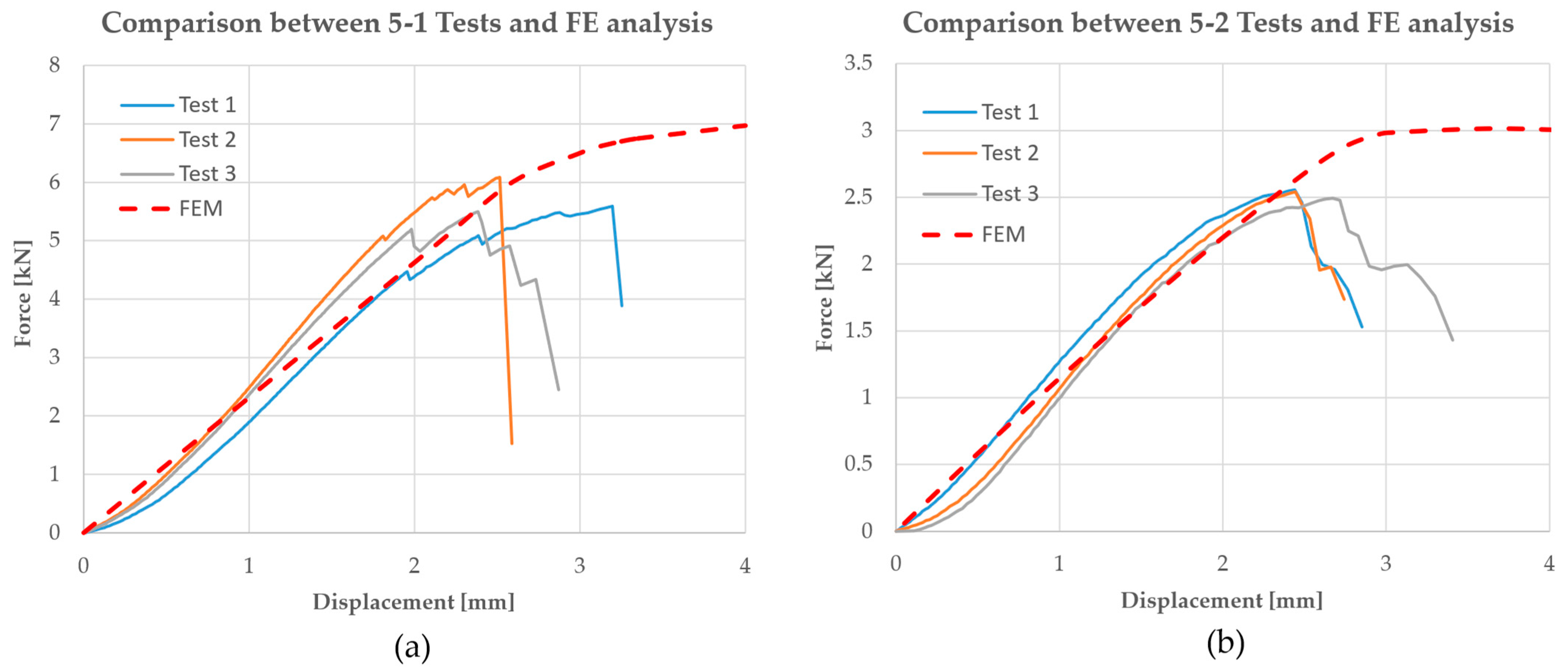

From the tests of lattices 5-1 and 5-2, it is possible to obtain the force vs. displacement curves needed for comparison with FEM. The nonlinear finite element analysis was performed by applying a linear displacement from 0 to 4 mm in 20 incremental sub-steps, considering large deflections. The used mesh elements are tetrahedrons, with a minimum edge size of 0.1 mm, and mesh controls have been applied to ensure closure, orientation, and prevent self-intersection. The boundary conditions are reported in

Table 9.

The finite element model accurately captures the general behavior of the elastic region in terms of stiffness and stress, considering the maximum allowable stress of the resin at 35 MPa. The curves are overlapped (

Figure 17), and the stiffness decrease is similar; the divergence starts from the crack inside the model, which is delayed in the finite element simulations. The Von Mises stress is reported in

Figure 18, with the localization of the highest values.

In this work, we considered the elastic behavior of the lattice; therefore, the results in the elastic field remain valid even when the material is changed. The density, yield strength, and material damping do not influence the E/S metric; in fact, the obtained lattice surfaces are created from geometrical considerations, independently of the material. The material change influences the manufacturing process, the production tolerances and the quality of the infill created using the lattice, influencing the stress distribution in case of a rough final shape.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, a novel methodology for designing a minimal surface lattice cell, optimized for structural performance in terms of material budget, is presented. This approach is compared to the well-known Gyroid and Schwartz designs. This objective has been achieved, without resolving any differential partial equation, but by creating a workflow adaptable to different environments and capable of starting from a cubic starting geometry, imposing boundary conditions, and constraints. In our approach, we propose starting from the initial geometry and then allowing it to evolve to reach the final shape according to the minimal surface formulation. This different approach allows us to define a priori the entire starting geometry, utilizing the concept of an initial framework, which in our case is the hypercube. The solutions have been compared in terms of the material budget ratio, offering an immediate quantitative index. The material budget is crucial for the design of mechanical components, especially when these components are integrated into particle accelerators and detectors. The decision to investigate this new family of lattices using the material budget as a performance parameter is innovative in this field.

The dynamic resolutive procedure permits independence from the geometrically exact equation of the minimal surface and is not connected with the Lagrangian equations. The main idea is to start from a generic mesh, consider each node as a mass element connected with the other nodes by the mesh edges, and apply forces to minimize the surface, obtaining a minimal surface, which permits the creation of a workflow adaptable to various geometries and boundary conditions, paying attention only to the final result desired. This approach offers a new way to compute shape to create a minimal surface-based lattice structure; it is only necessary to create the starting geometry, the hypercube in this case, and with the dynamic approach, the final lattice shape can be created. It is important to highlight that the result was achieved without knowing the exact minimal surface equation or resolving partial differential equations.

The obtained cells, in particular the 5-1 lattice, are better in terms of material budget than the Gyroid by a factor of 2.3 and Schwartz by a factor of 1.7; the lattice 5-2 is better than Schwartz by a factor of 1.4 and equal to the Gyroid. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of the workflow and the achievement of the research’s scope. The proposed workflow concludes with the use of the lattice as infill in various designs; this step paves the way for future development, particularly the possibility of implementing the created lattice within a 3D-printing slicer. In this way, the created lattices can be used as infill directly in the slicing phase.

As a final remark, it is essential to highlight that in the proposed workflow, it has been possible to determine the starting geometries, boundary conditions, and comparative parameters, which demonstrate the flexibility of the approach.

The considered application is static and in a controlled atmosphere (20 °C, 50% humidity); therefore, only a compression test was performed. In case fatigue and dynamic behavior are important, such as long-term stability under various environmental conditions, different tests must be included in the study.

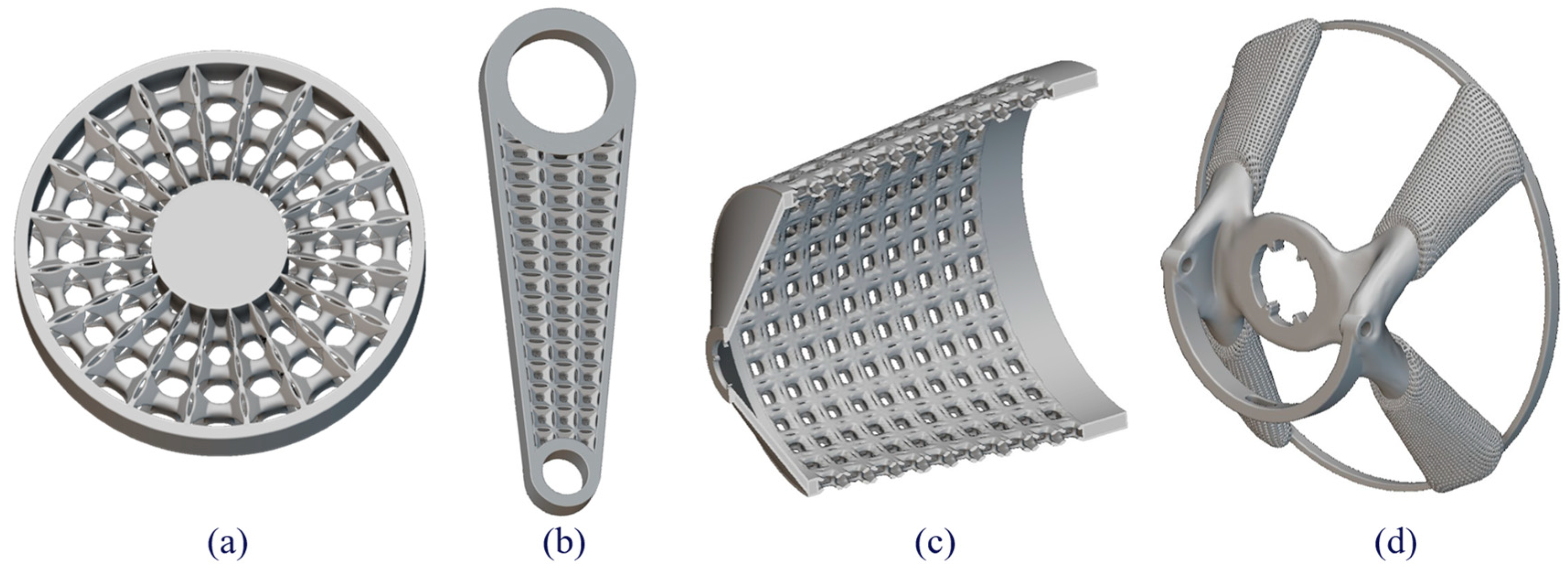

In order to contextualize the presented workflow, some examples of using the lattice cells as infill for mechanical parts are reported; this allows us to integrate the proposed workflow in a product design process. Defining a custom unit cell and a cell map, which is essentially a spatial distribution and positioning of the lattice cells, it is possible to create a conformal infill that follows the geometry. Three examples have been created: the first configuration consists of the infill between two faces (

Figure 19a,b), creating the cell map between them; in the second scenario, there is infill inside a volume (

Figure 19c); for the third scenario, the entire volume of four harms has been substituted using the 5-2 lattice (

Figure 19d).

For the first configuration, it has been achieved a mass reduction of 67% (a) and 45% (b), 21% for the second configuration, and 20% for the third. The results are summarized in

Table 10.

Future developments of the proposed workflow can involve machine learning (ML) [

33,

34] to optimize multiple parameters and create different lattice configurations. ML-based approaches can be used to predict mechanical performance through building surrogate models to avoid the high computational costs of running FEA simulations. The different scenarios could be created considering different boundary conditions, different starting geometries, and

RDF scenarios, targeting [

35] the material budget performance required and generating the cells that respect these performances. The inclusion of the ML in the workflow will be investigated, and the possibility of inserting the ML in the workflow proves the flexibility and adaptability for future developments.

A last consideration regarding the use of the proposed lattice in large-scale production can be a starting point for other future works. The lattice structures require additive manufacturing for production, which allows for a reduction in the raw material [

36], a reduction in waste [

37], and automated parameter optimization, improving the resistance and reducing the need for rework. On the other hand, the use of AM for lattice manufacturing increases machine runtime due to its high complexity, which is translated into increased process costs and limits standardization for critical applications [

38]. Considering all these aspects, the use of a lattice family in large-scale production required the integration of the proposed workflow with AM parameter optimization. Aligning the lattice design with the manufacturing constraints, using ML techniques, it could be possible to reduce the cost, reducing the material budget, which is the aim of this work, considering the manufacturing process for large-scale production.