Novel Development of FDM-Based Wrist Hybrid Splint Using Numerical Computation Enhanced with Material and Damage Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Preliminary Testing Process

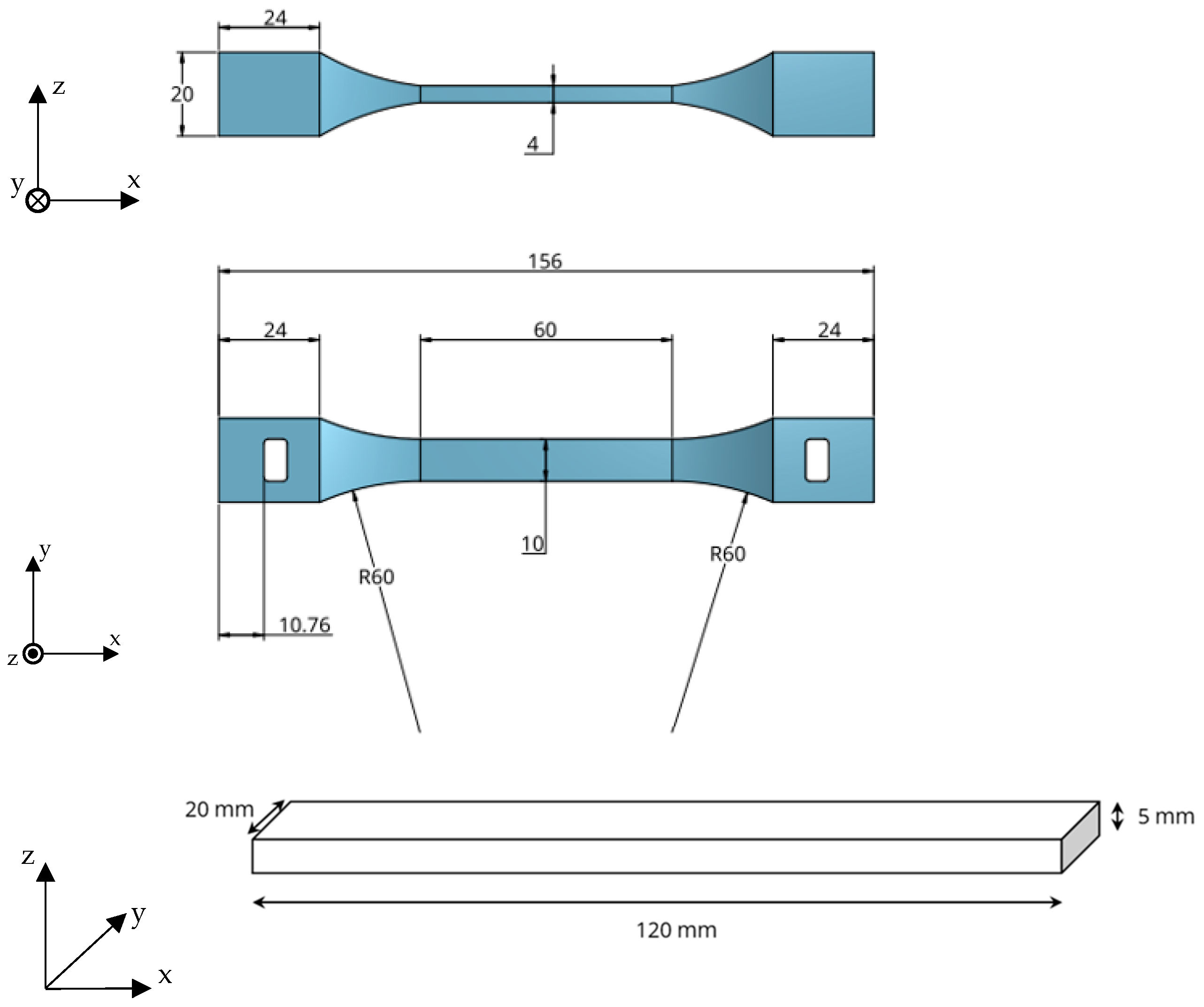

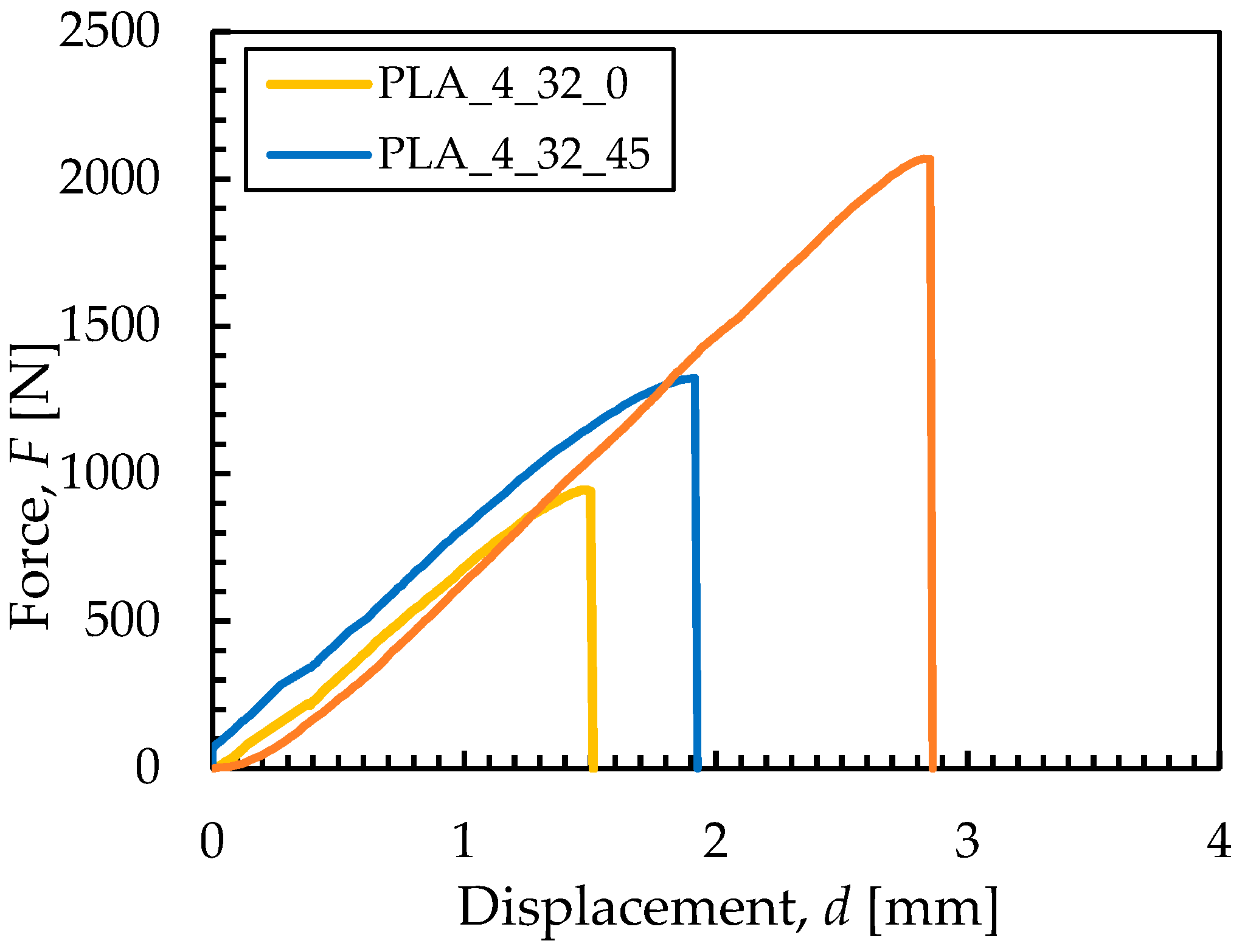

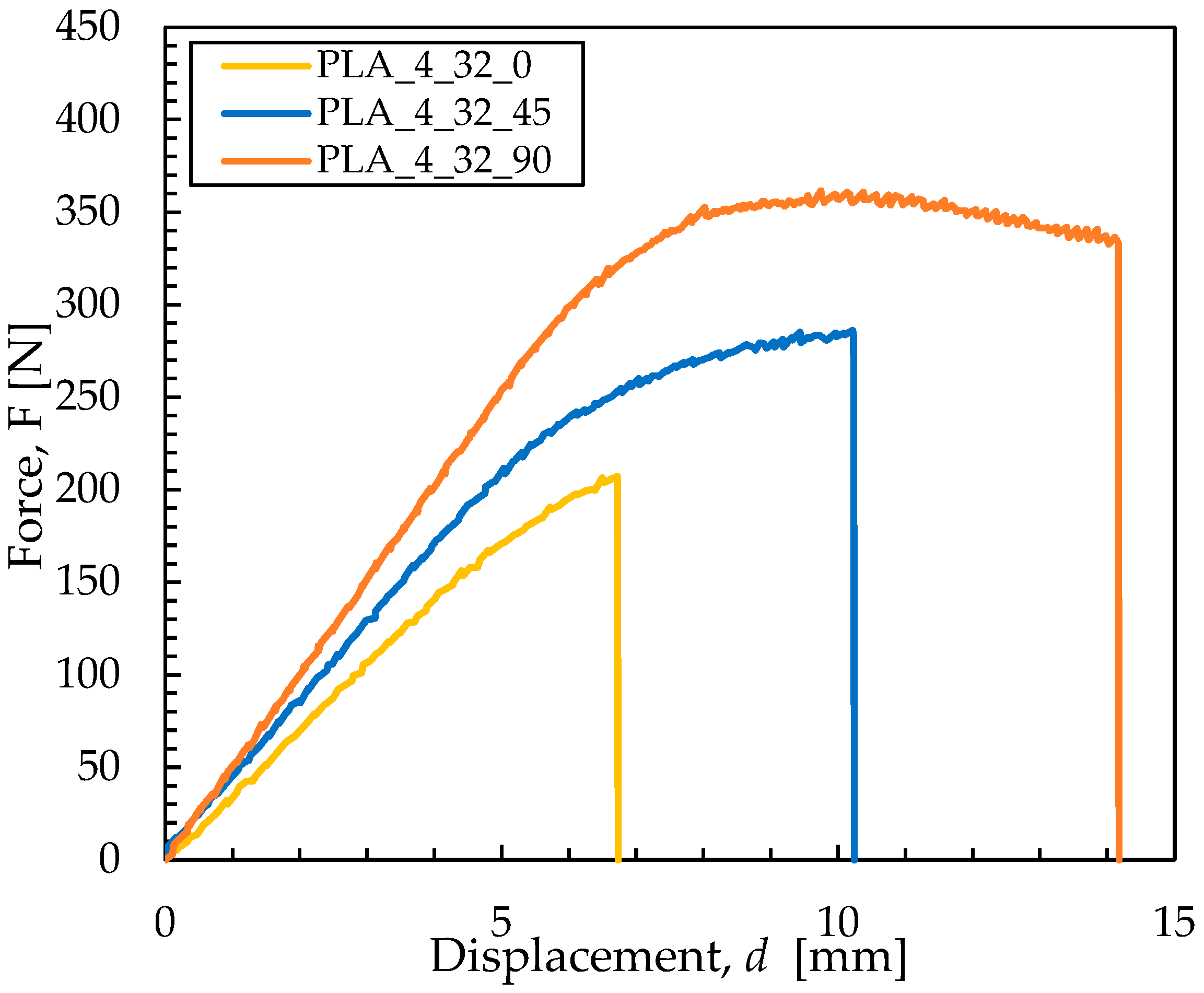

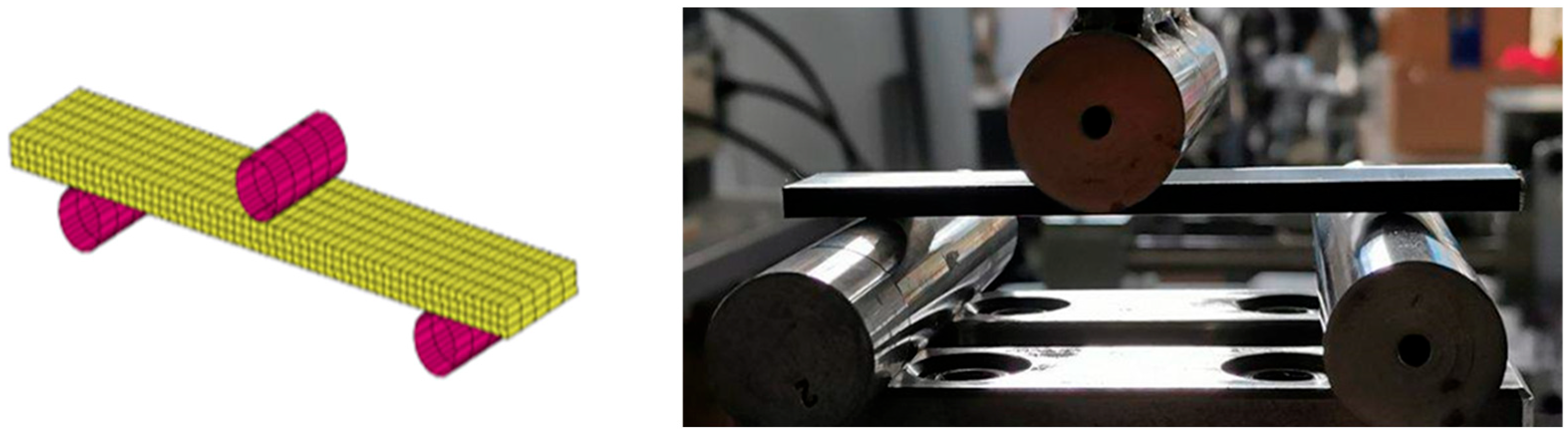

2.1. Preliminary Tensile Testing and Three-Point Bending Setup

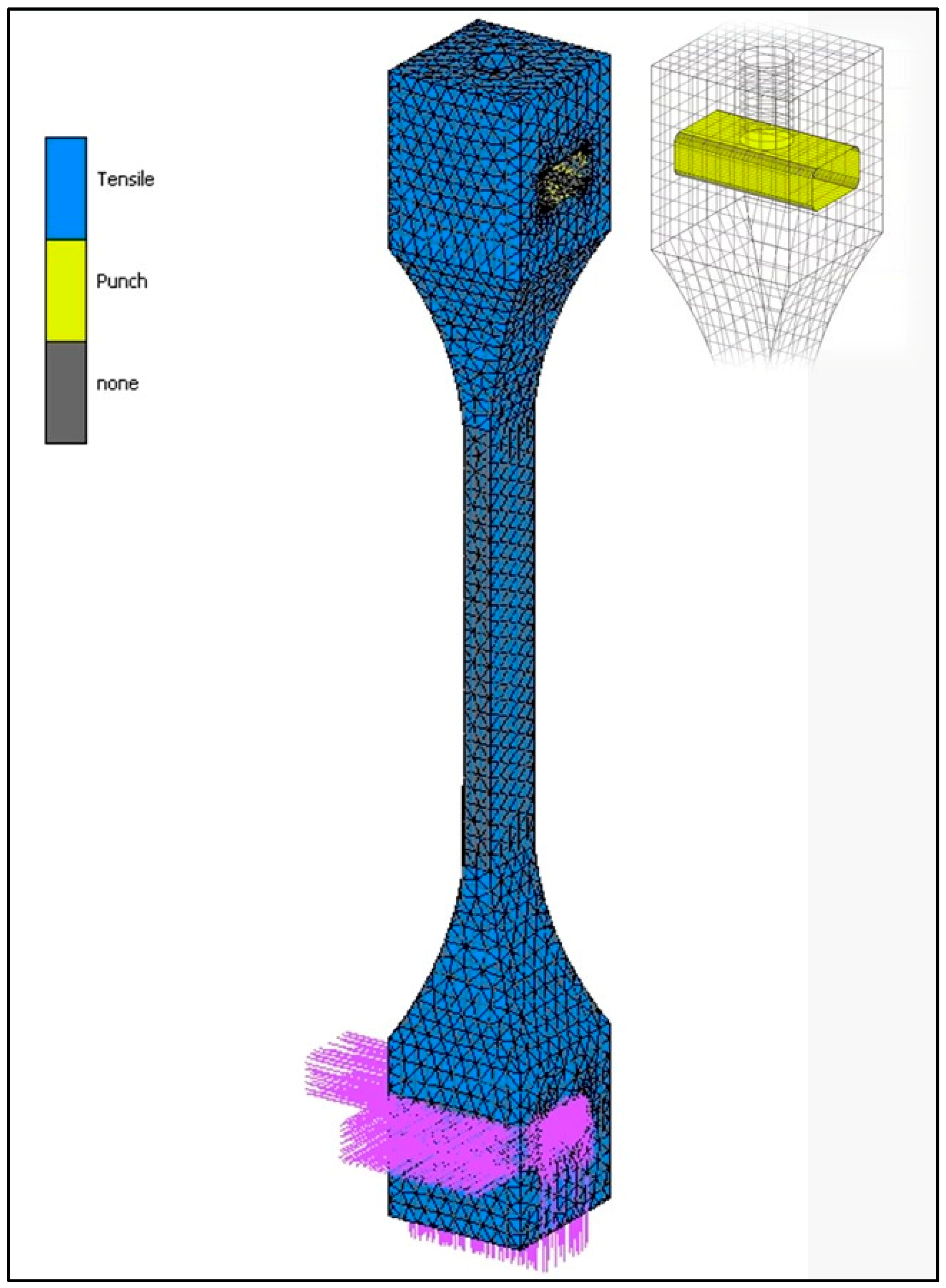

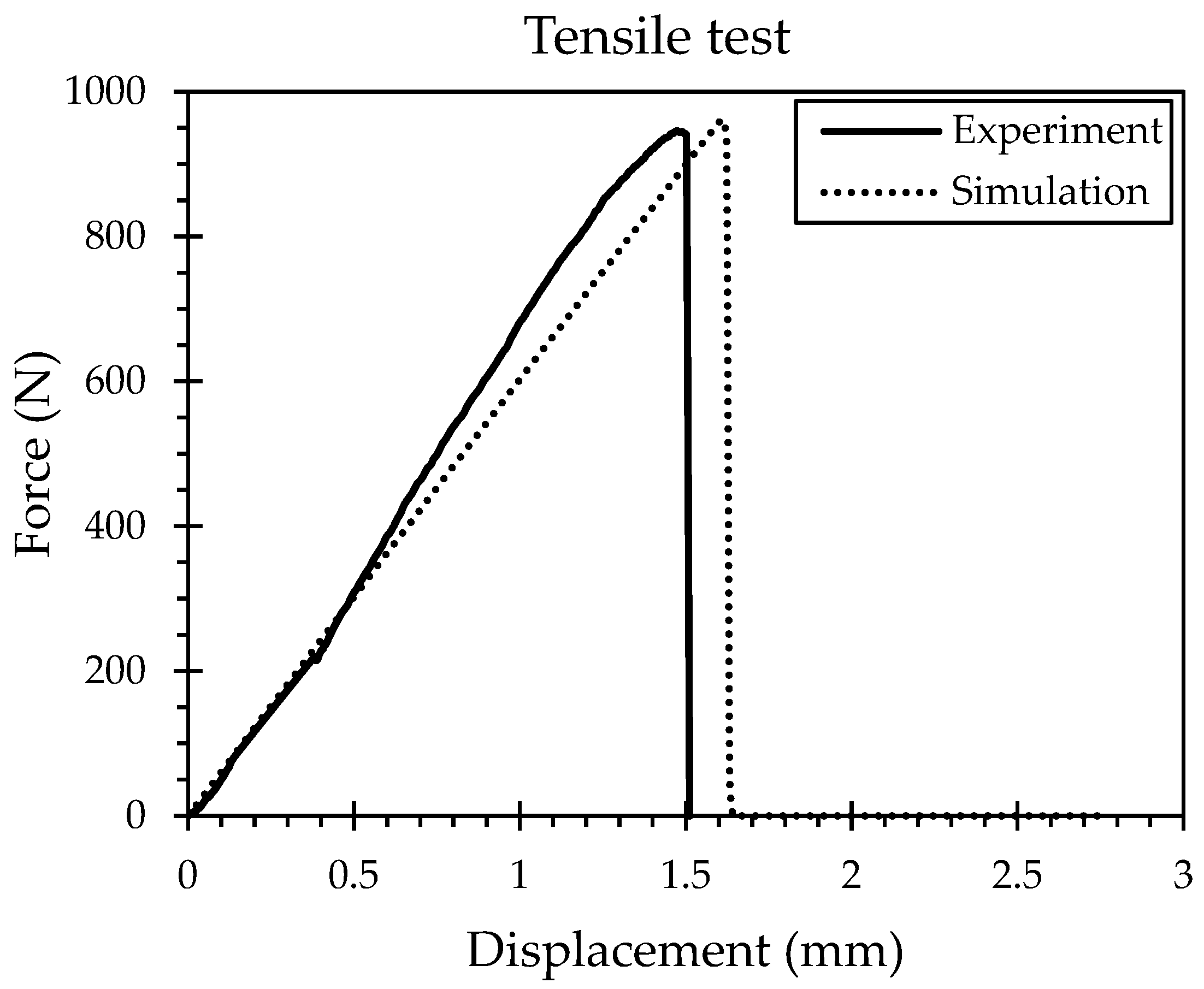

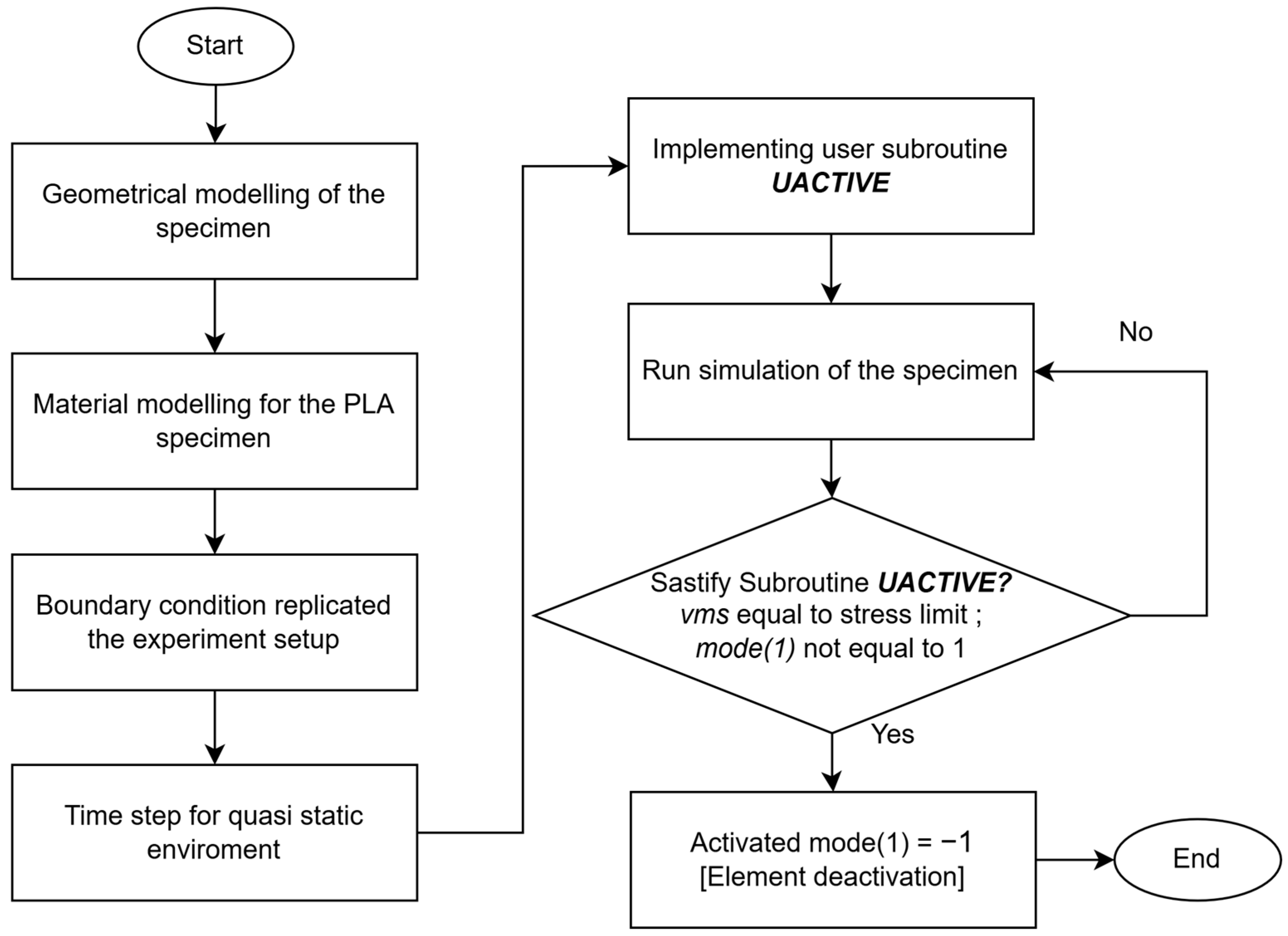

2.2. Numerical Simulation of Tensile Simulation in MSC Marc/Mentat

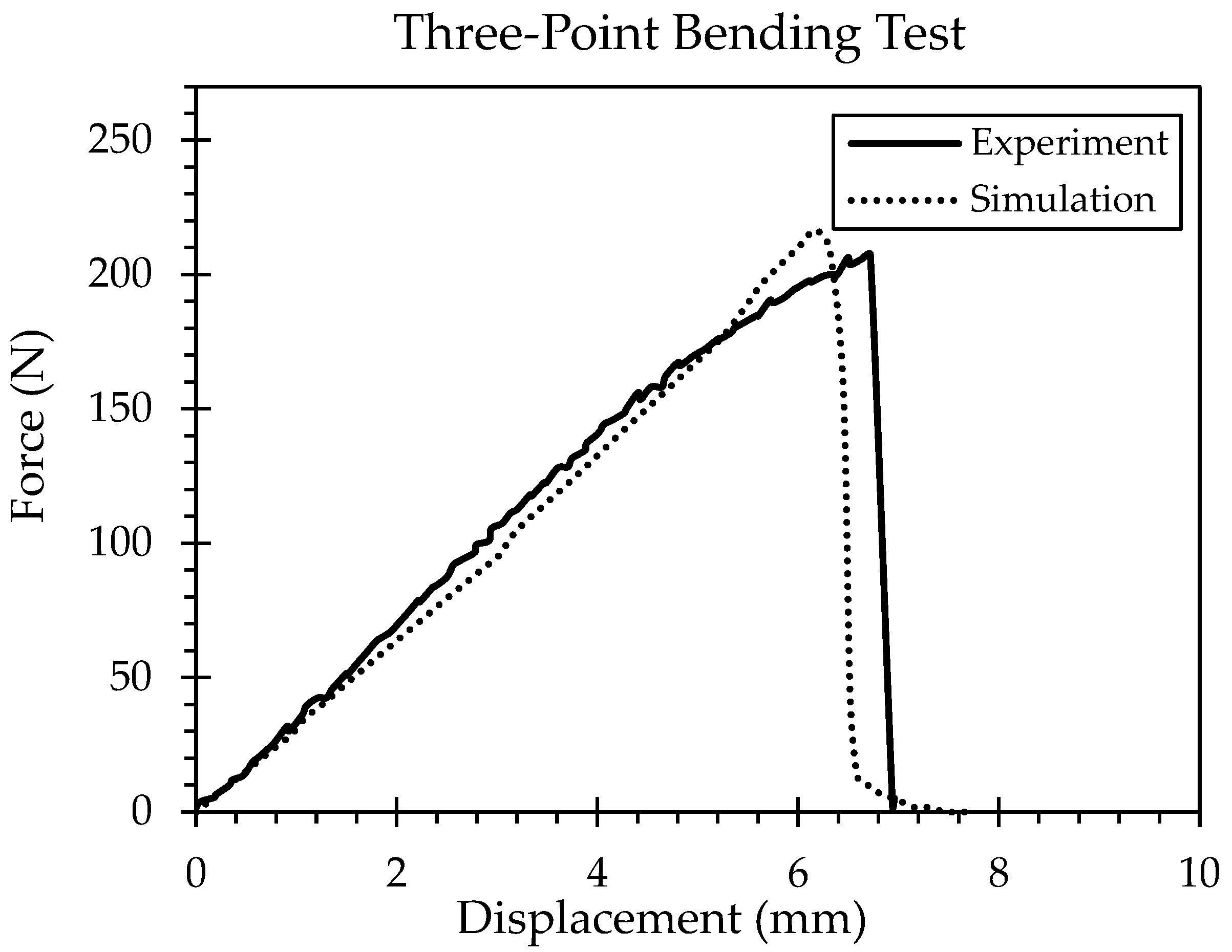

2.3. Numerical Simulation of Three-Point Bending in MSC Marc/Mentat

| Algorithm 1. User Subroutine UACTIVE | ||

| 1: | Variable subroutine uactive (m, n, mode, irststr, irststn, inc, time, timinc) | |

| 2: | Define integer inc, irststn, irststr, m, mode, n, ielem, ie | |

| 3: | real * 8 time, timin, common /mydata/ ielem(60,000) | |

| 4: | dimension m(2), mode(3) // Assign dimension for post result data | |

| 5: | Call integer ie = m(1) | |

| 6: | if ielem(ie) not equal to the stress threshold and mode(1) not equal to 1 | |

| 7: | then, mode(1) = -1 // The deactivation of element | |

| 8: | else mode(1) = 2 // The remain post element will be calculated | |

| 9: | end | |

3. Numerical Simulation and Experimental Process of WHS Model

3.1. Experimental Setup Testing of WHS Component

3.2. Numerical Simulation of Three-Point Bending on WHS Component

4. Numerical Simulation Results of WHS Components

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Material characterization and modeling: PLA specimens fabricated under varying deposition orientations exhibited distinct mechanical responses. Both tensile and three-point bending tests revealed orientation-dependent strength, stiffness, and fracture behavior. The incorporation of experimental data of the 0° deposition orientation, which approximates the FDM process of the WHS component more closely, into the FE model yielded highly consistent results, with simulation errors remaining within acceptable limits (≤10%), thus validating the robustness of the material and damage models.

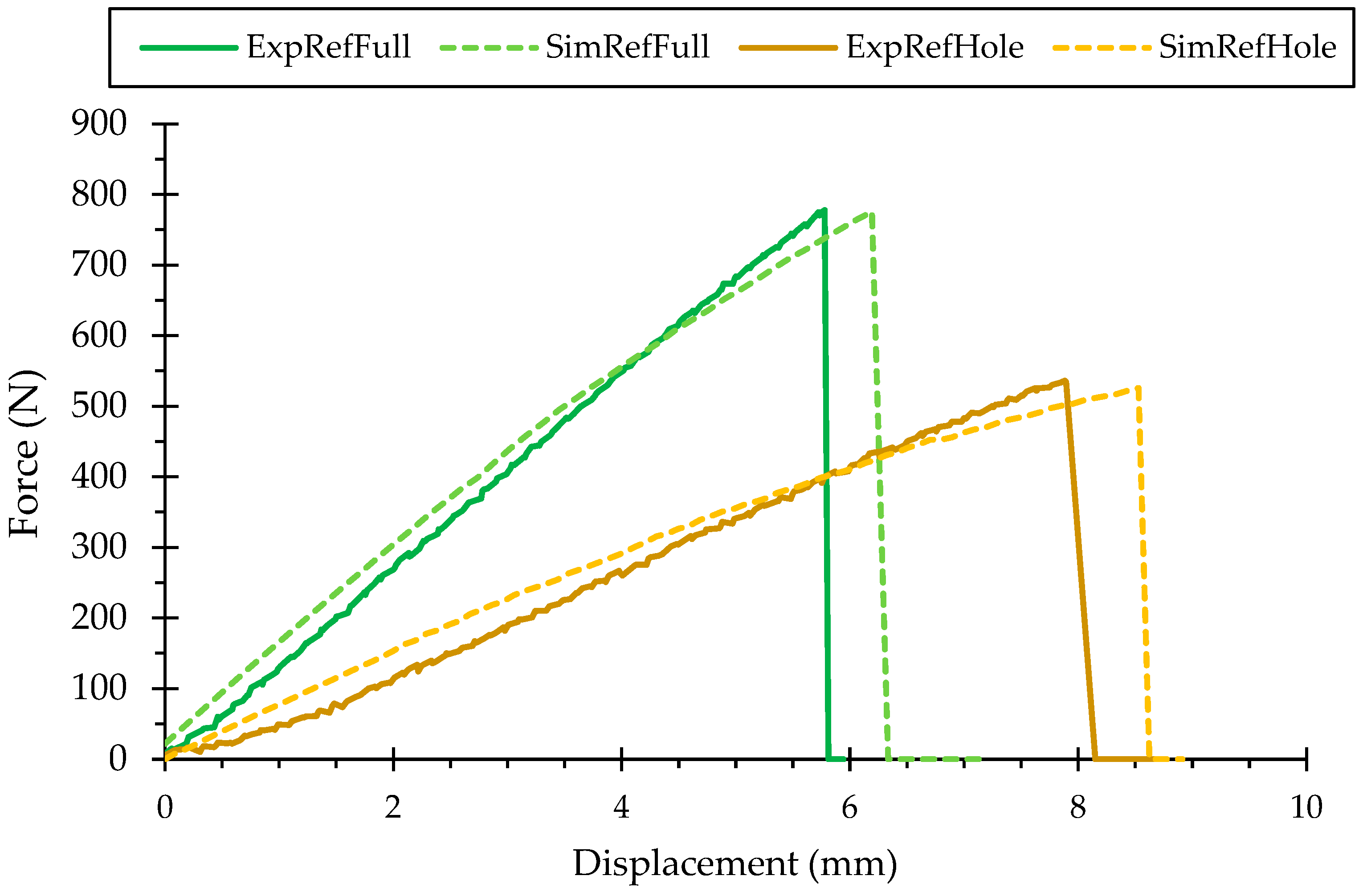

- Numerical–experimental congruence: The implementation of customized subroutines, particularly the UACTIVE algorithms, allowed for effective simulation of stiffness, plasticity, and fracture in PLA-based splints. The force–displacement responses of the WHS obtained from simulations closely matched experimental outcomes, with deviations in peak load and displacement remaining marginal (TB updated). This congruence underscores the predictive capability of the proposed modeling approach.

- WHS simulation and experiment result comparison: The simulation results showed excellent agreement with experimental data, with maximum force deviations of only 1.28% for the full specimen (RefFull) and 1.92% for the specimen with a hole (RefHole). These findings confirm that the numerical model accurately predicts both stiffness and failure behavior.

- Contribution to additive manufacturing in orthopedics: The results substantiate the feasibility of employing FDM with biocompatible PLA for the production of orthopedic support devices. By integrating advanced computational modeling into the design workflow, the iterative trial-and-error process can be significantly reduced, thereby lowering costs and accelerating development cycles.

- Fatigue and durability studies: Long-term performance under cyclic loading and environmental exposure (humidity, body temperature, wear) should be investigated to ensure reliability during extended clinical use.

- Patient-specific customization: The integration of medical imaging data (e.g., CT or MRI scans) into the design pipeline could enable highly personalized splints, tailored to individual patient anatomy and functional requirements.

- Broader numerical framework: Expanding the simulation framework to include viscoelasticity, time-dependent degradation, and multi-material deposition strategies will improve predictive accuracy and enable the design of next-generation orthopedic devices.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bekas, D.; Hou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Panesar, A. 3D printing to enable multifunctionality in polymer-based composites: A review. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 179, 107540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, C.Y.; Chua, C.K.; Dong, Z.L.; Liu, Z.H.; Zhang, D.Q.; Loh, L.E.; Sing, S.L. Review of selective laser melting: Materials and applications. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2015, 2, 041101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonabadi, H.; Chen, Y.; Yadav, A.; Bull, S. Investigation of the effect of raster angle, build orientation, and infill density on the elastic response of 3D printed parts using finite element microstructural modeling and homogenization techniques. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 118, 1485–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanaei, S.; Rastak, M.; El Magri, A.; Vanaei, H.R.; Raissi, K.; Tcharkhtchi, A. Orientation-Dependent Mechanical Behavior of 3D Printed Polylactic Acid Parts: An Experimental–Numerical Study. Machines 2023, 11, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M. Additive Manufacturing Applications in Industry 4.0: A Review. J. Ind. Integr. Manag. 2019, 4, 1930001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raziyan, M.S.; Palevicius, A.; Perkowski, D.; Urbaite, S.; Janusas, G. Development and Evaluation of 3D-Printed PLA/PHA/PHB/HA Composite Scaffolds for Enhanced Tissue-Engineering Applications. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 52900; Terminology for Additive Manufacturing—General Principles—Terminology. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- Kishore, R.; Moorthy, M.V.; Gokul, P.S.; Mugilan; Mugundhan. Additive manufacturing composites of poly lactic acid (PLA). J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2027, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikas, H.; Koutsoukos, S.; Stavropoulos, P.A. Decision support method for evaluation and process selection of Additive Manufacturing. Procedia CIRP 2019, 81, 1107–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, P.; Banerjee, S.S. Fused Deposition Modeling of Thermoplastics Elastomeric Materials: Challenges and Opportunities. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 46, 102177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Abotiheen, M.H. Finite element analysis is a powerful approach to predict manufacturing parameters. J. Univ. Babylon Pure Appl. Sci. 2018, 26, 229–238. [Google Scholar]

- García-Dominguez, A.; Claver, J.; Sebastián, M.A. Integration of Additive Manufacturing, Parametric Design, and Optimization of Parts Obtained by Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM). A Methodological Approach. Polymers 2020, 12, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almonti, D.; Salvi, D.; Mingione, E.; Vesco, S. Lightweight and Sustainable Steering Knuckle via Topology Optimization and Rapid Investment Casting. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S. Finite Element Analysis in Fused Deposition Modeling Research: A Literature Review. Measurement 2021, 178, 109320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samy, A.A.; Golbang, A.; Harkin-Jones, E.; Archer, E.; Tormey, D.; McIlhagger, A.T. Finite element analysis of residual stress and warpage in a 3D printed semi-crystalline polymer: Effect of ambient temperature and nozzle speed. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 70, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chou, K. A parametric study of part distortions in fused deposition modelling using three-dimensional finite element analysis. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2018, 222, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zur, P.; Kołodziej, A.; Baier, A. Finite Elements Analysis of PLA 3D-printed Elements and Shape Optimization. Eur. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2019, 2, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, N.; Yang, G.; Yang, K.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Zhou, J. Implementation of Abaqus User Subroutines and Plugin for Thermal Analysis of Powder-bed Electron-Beam-Melting Additive Manufacturing Process. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 27, 102307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.; Ni, J.; Antonissen, J.; Hamouda, H.B.; Voorde, J.V.; Wahab, M.A. Numerical prediction of Microstructure and Hardness for Low Carbon Steel Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing Components. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2022, 122, 102664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.N.; Manurung, Y.H.P.; Mat, M.F.; Minggu, Z.; Jaffar, A.; Prueller, S.; Leitner, M. FEM Simulation Procedure for Distortion and Residual Stress Analysis of Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 834, 012083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behseresht, S.; Park, H.P. Additive Manufacturing of Composite Polymers: Thermomechanical FEA and Experimental Study. Materials 2024, 17, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boisse, P.; Colmars, J.; Hamila, N.; Naouar, N.; Steer, Q. Bending and wrinkling of composite fiber preforms and prepregs. A review and new developments in the draping simulations. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018, 141, 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, Z.H.; Cheng, F.; Han, N.X.; Zhu, G.M.; Tang, J.N.; Xing, F. Evaluation of the mechanical performance recovery of self-healing cementitious materials—Its methods and future development: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 212, 400–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atakok, G.; Kam, M.; Koç, H. Tensile, three-point bending and impact strength of 3D printed parts using PLA and recycled PLA filaments: A statistical investigation. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 18, 1542–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Tyagi, R.; Ranjan, V.; Sathujoda, P. FEM simulation of three-point bending test of Inconel 718 coating on stainless steel substrate. Vibroengineering PROCEDIA 2018, 21, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón, J.M.; García-Plaza, E.; López, P. Additive manufacturing of PLA structures using fused deposition modelling: Effect of process parameters on mechanical properties and their optimal selection. Mater. Des. 2017, 124, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, A.; Ardiansyah, R.; Isna, L.; Larasati, I. Effect of layer thickness on flexural properties of PLA (PolyLactid Acid) by 3D printing. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1130, 012017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Ishak, M. The Effect of Fused Deposition Modeling Parameters (FDM) on the Mechanical Properties of Polylactic Acid (PLA) Printed Parts. Adv. Appl. Mech. 2024, 123, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Y. Novel mechanical models of tensile strength and elastic property of FDM AM PLA materials: Experimental and theoretical analyses. Mater. Des. 2019, 181, 108089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaya Christiyan, K.G.; Chandrasekhar, U.; Venkateswarlu, K. Flexural Properties of PLA Components Under Various Test Condition Manufactured by 3D Printer. J. Inst. Eng. Ser. C 2018, 99, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D790-20; Standard Test Methods for Flexural Properties of Unreinforced and Reinforced Plastics and Electrical Insulating Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- Rajpurohit, S.; Dave, H.; Bodaghi, M. Classical laminate theory for flexural strength prediction of FDM 3D printed PLAs. Mater. Today Proc. 2024, 101, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Bhattacharya, A. An Insight to the Failure of FDM Parts Under Tensile Loading: Finite Element Analysis and Experimental Study. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2017, 120, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, H.; Prajapati, A.; Rajpurohit, S.; Patadiya, N.; Raval, H. Investigation on tensile strength and failure modes of FDM printed part using in-house fabricated PLA filament. Adv. Mater. Process. Technol. 2020, 8, 576–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karad, A.; Sonawwanay, P.; Naik, M.; Thakur, D. Experimental study of effect of infill density on tensile and flexural strength of 3D printed parts. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2023, 70, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D638-14; Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Plastics. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014.

| Physical Property | Typical Value |

|---|---|

| Density | 1.2 g/cm3 |

| Glass transition temperature | 62.3 °C |

| Melting temperature | 150.9 °C |

| Young’s modulus (X–Y) | 2681 ± 215 MPa |

| Tensile strength (X–Y) | 40 ±1 MPa |

| Elongation at break (X–Y) | 2.5 ± 0.6% |

| Flexural modulus (X–Y) | 2700 ± 154 MPa |

| Flexural strength (X–Y) | 68 ± 2 MPa |

| Young’s modulus (Z) | 2551 ± 335 MPa |

| Tensile strength (Z) | 36 ± 5 MPa |

| Elongation at break (Z) | 6 ± 2.4% |

| Process Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Printing speed | 50 mm/s |

| Extrusion temperature | 205 °C |

| Bed temperature | 60 °C |

| Nozzle diameter | 0.4 mm |

| Layer thickness | 0.32 mm |

| Deposition angle | 0, 45, 90 |

| Material Properties | Value |

|---|---|

| Mass Density | 1.24 g/cm3 |

| Young’s Modulus | 1318 MPa |

| Poisson’s Ratio | 0.3 |

| Tensile Yield Stress | 25 MPa |

| Material Properties | Value |

|---|---|

| Mass Density | 1.24 g/cm3 |

| Flexural Modulus | 1640 MPa |

| Poisson’s Ratio | 0.3 |

| Flexural Yield Stress | 65 MPa |

| Contact Body | Contact Definition |

|---|---|

| NURBS (punch die) | Rigid body |

| Upper die (punch die) | Rigid body |

| Workpiece | Meshed (deformable) |

| Lower supports | Rigid body |

| Material Properties | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Full WHS | WHS with Hole | |

| Mass density | 1.24 g/cm3 | 1.24 g/cm3 |

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Flexural modulus | 2040 MPa | 1840 MPa |

| Flexural yield stress | 65 MPa | 55 MPa |

| Specimen | Peak Force Experiment (N) | Peak Force Simulation (N) | Displacement Experiment (mm) | Displacement Simulation (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full specimen | 780 ± 15 | 770 | 5.9 ± 0.2 | 6.1 |

| With hole | 520 ± 10 | 510 | 8.3 ± 0.3 | 8.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Papadakis, L.; Avraam, S.; Mohd Izhar, M.Z.; Prajadhiana, K.P.; Manurung, Y.H.P.; Photiou, D. Novel Development of FDM-Based Wrist Hybrid Splint Using Numerical Computation Enhanced with Material and Damage Model. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120408

Papadakis L, Avraam S, Mohd Izhar MZ, Prajadhiana KP, Manurung YHP, Photiou D. Novel Development of FDM-Based Wrist Hybrid Splint Using Numerical Computation Enhanced with Material and Damage Model. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing. 2025; 9(12):408. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120408

Chicago/Turabian StylePapadakis, Loucas, Stelios Avraam, Muhammad Zulhilmi Mohd Izhar, Keval Priapratama Prajadhiana, Yupiter H. P. Manurung, and Demetris Photiou. 2025. "Novel Development of FDM-Based Wrist Hybrid Splint Using Numerical Computation Enhanced with Material and Damage Model" Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 9, no. 12: 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120408

APA StylePapadakis, L., Avraam, S., Mohd Izhar, M. Z., Prajadhiana, K. P., Manurung, Y. H. P., & Photiou, D. (2025). Novel Development of FDM-Based Wrist Hybrid Splint Using Numerical Computation Enhanced with Material and Damage Model. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, 9(12), 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120408