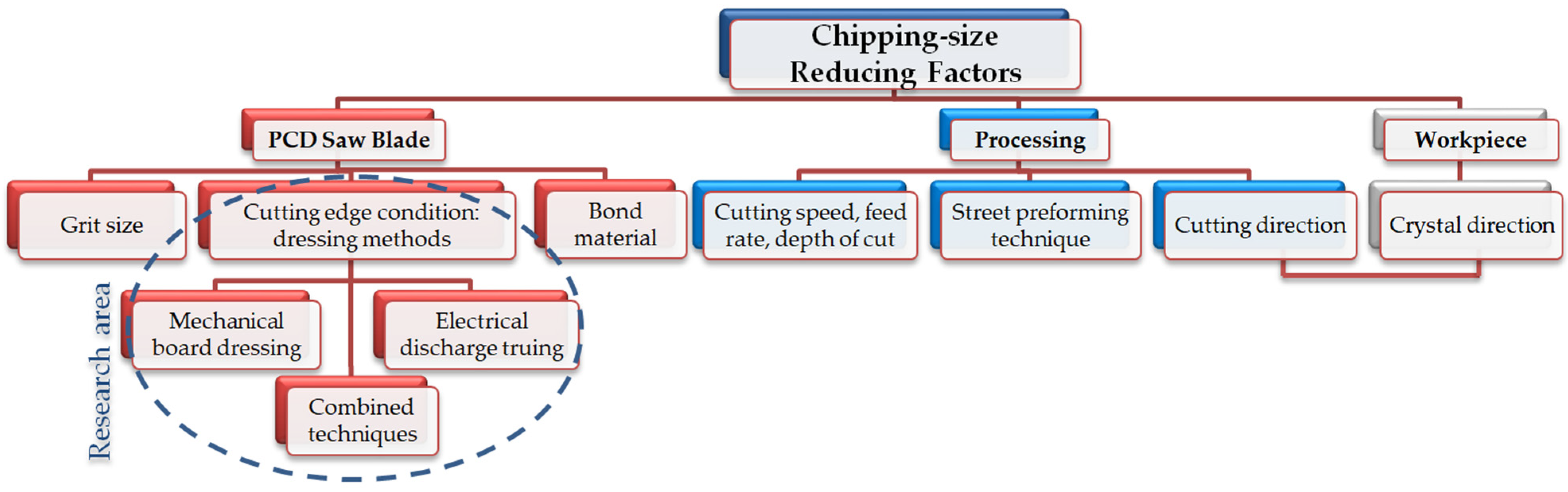

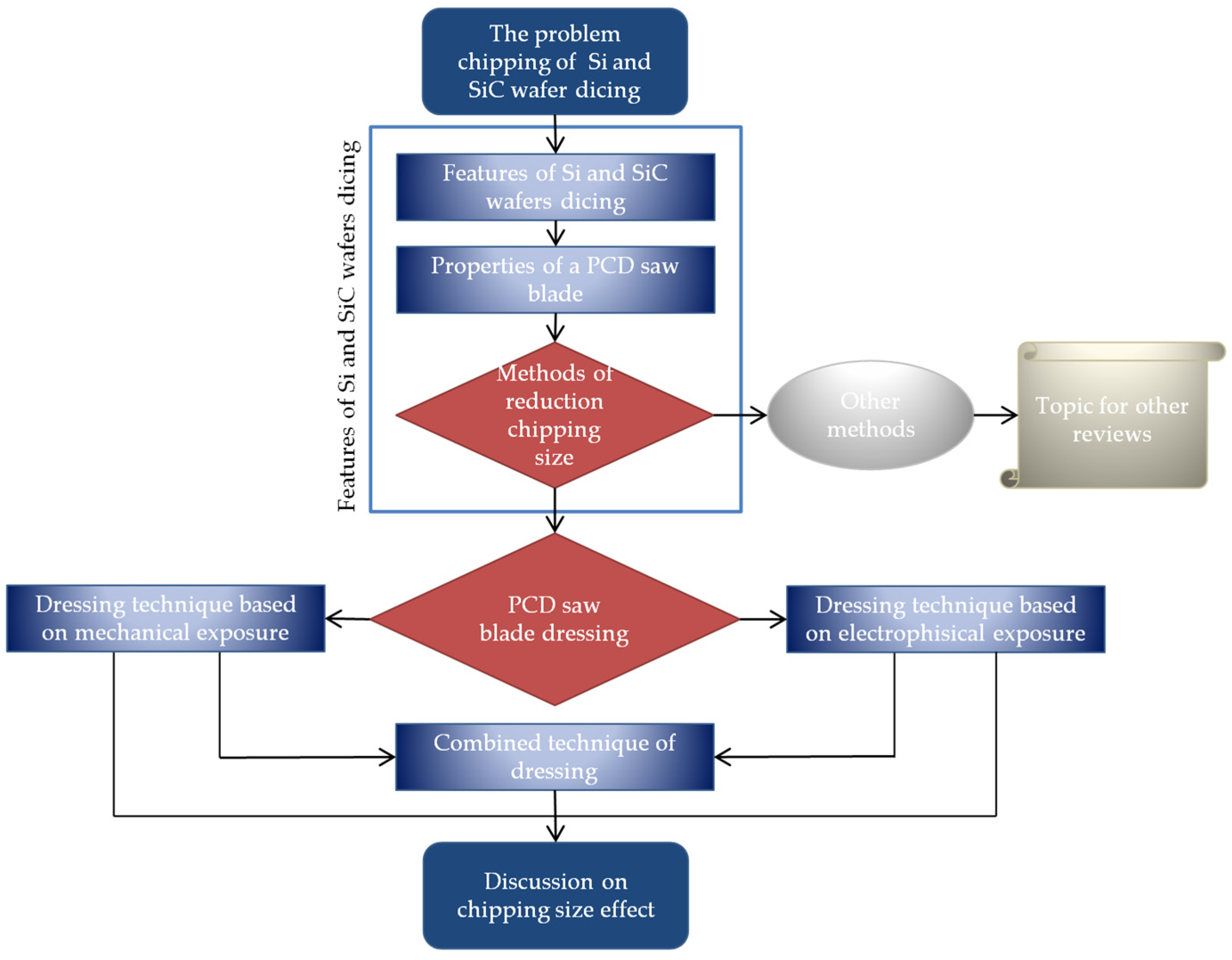

Influence of Dressing Methods on Chipping Size During Si and SiC Die Singulation: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Features of Polycrystalline Diamond Saw Blade, Dicing and Dressing

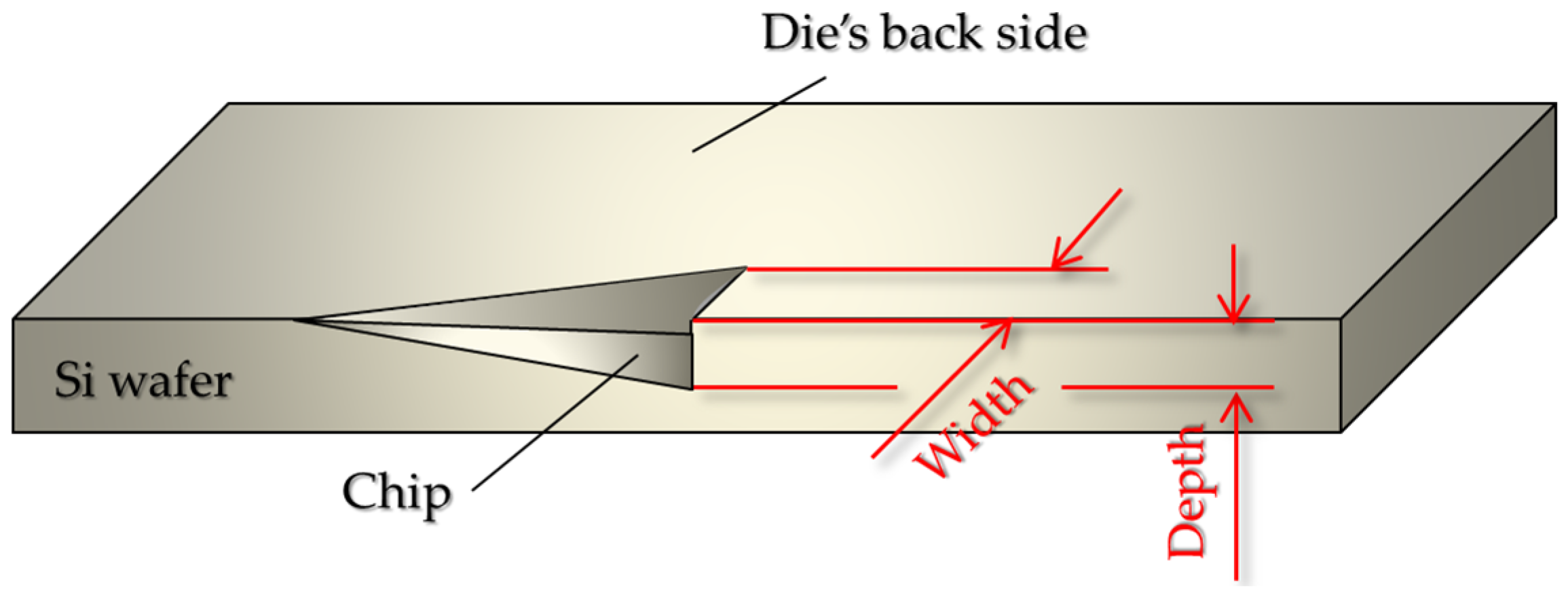

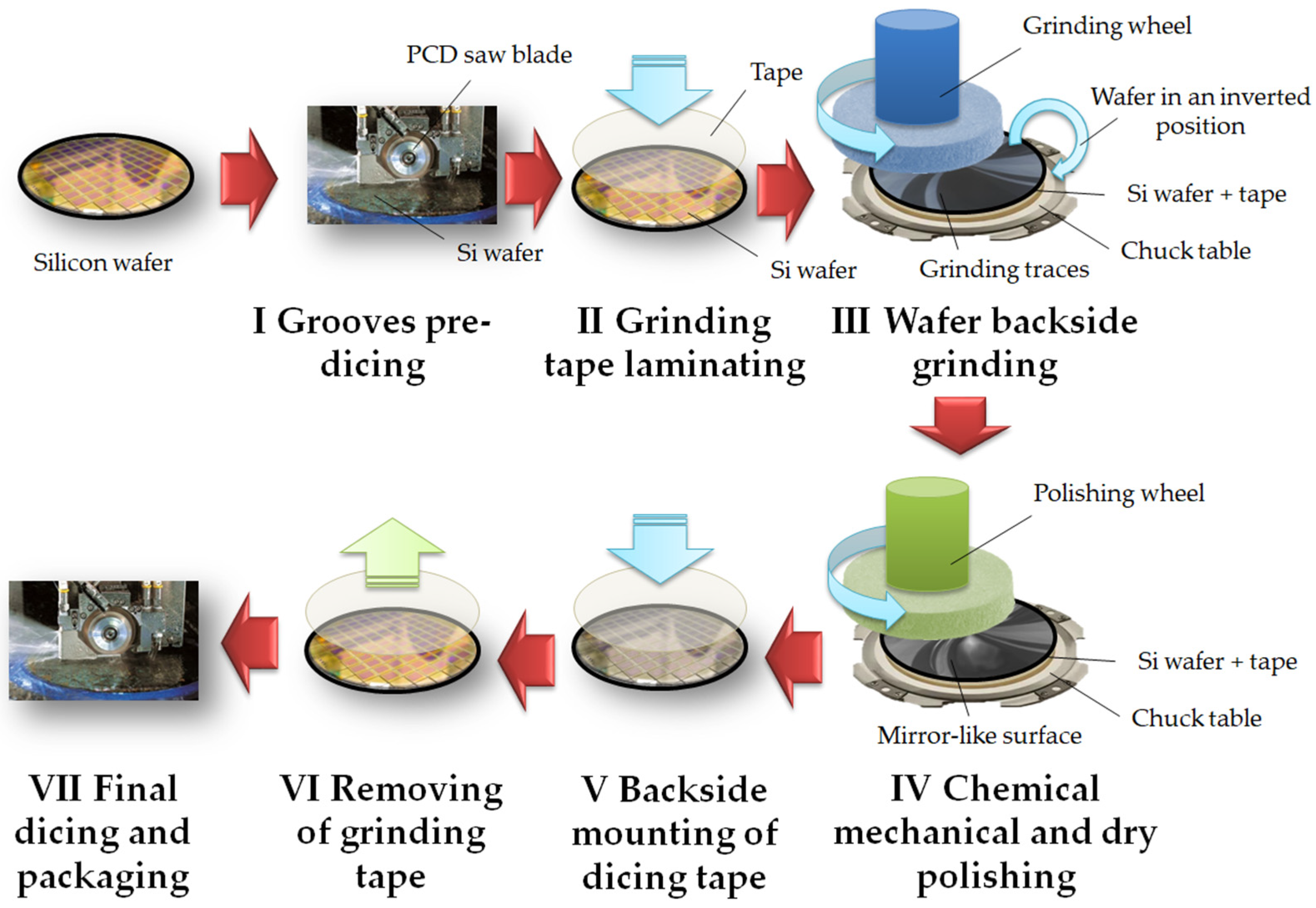

2.1. Features of Dicing as a Step in the Production of Integrated Circuit Packaging

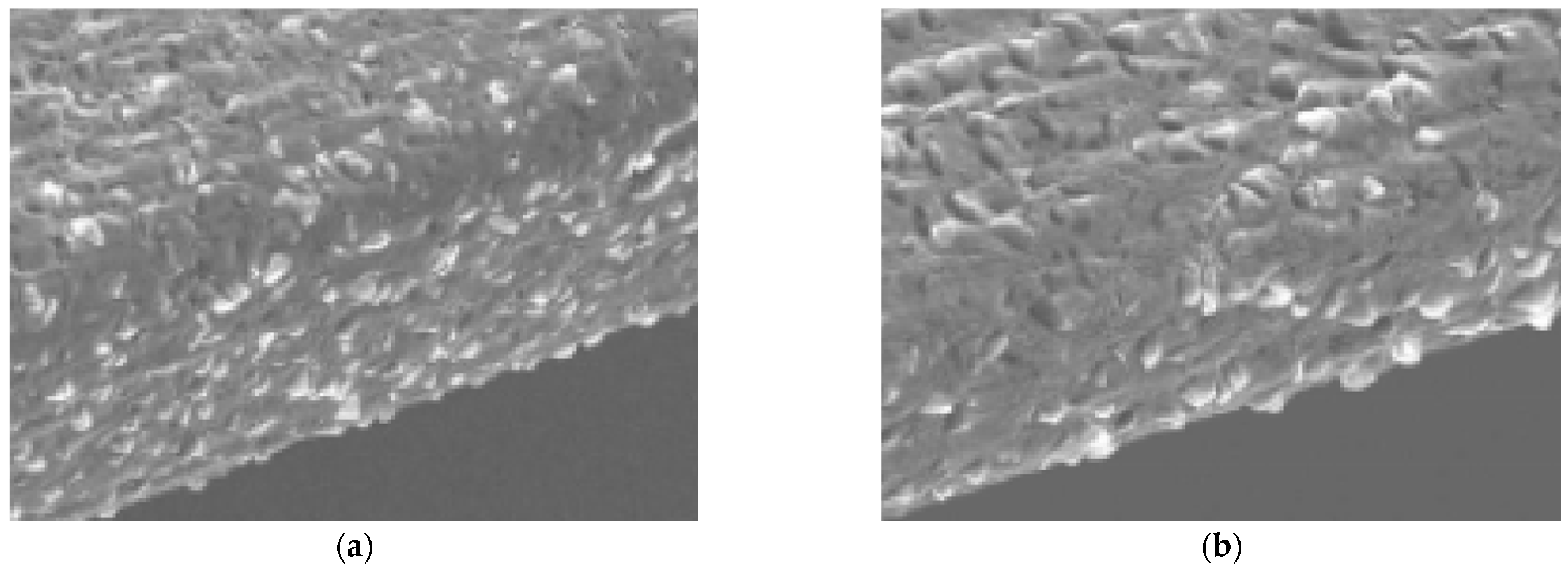

2.2. Properties and Description of a Polycrystalline Diamond Saw Blade

- High hardness and wear resistance, which maintains a sharp cutting edge in machining hard-to-cut materials ((the hardness of the base elements of PCD saw blades is 42–48 HRC, and that is ~405–485 HV when the hardness of polycrystalline diamond grains ranges from 6500 to 7500 HV with a metal (mainly nickel) bond; this value is close to the hardness of pure diamond of 10,000 HV, and that is 30 times harder than the value for hard alloy)) [28]; hardness also depends on the purity, perfection of the crystal structure, and orientation: it is higher in flawless, pure crystals oriented in the direction (along the long diagonal of the cubic diamond lattice) [29];

- Excellent thermal conductivity, which facilitates rapid heat dissipation and reduces temperature on the contact pad between a tool and workpiece; the thermal conductivity of polycrystalline diamond for saw blades is 700 W/m·K, and that is 1.5–9 times higher than that of cemented carbide and even higher than that of polycrystalline cubic boron nitride and copper [30];

- Stability under medium operating conditions: at temperatures under 700 °C and pressure.

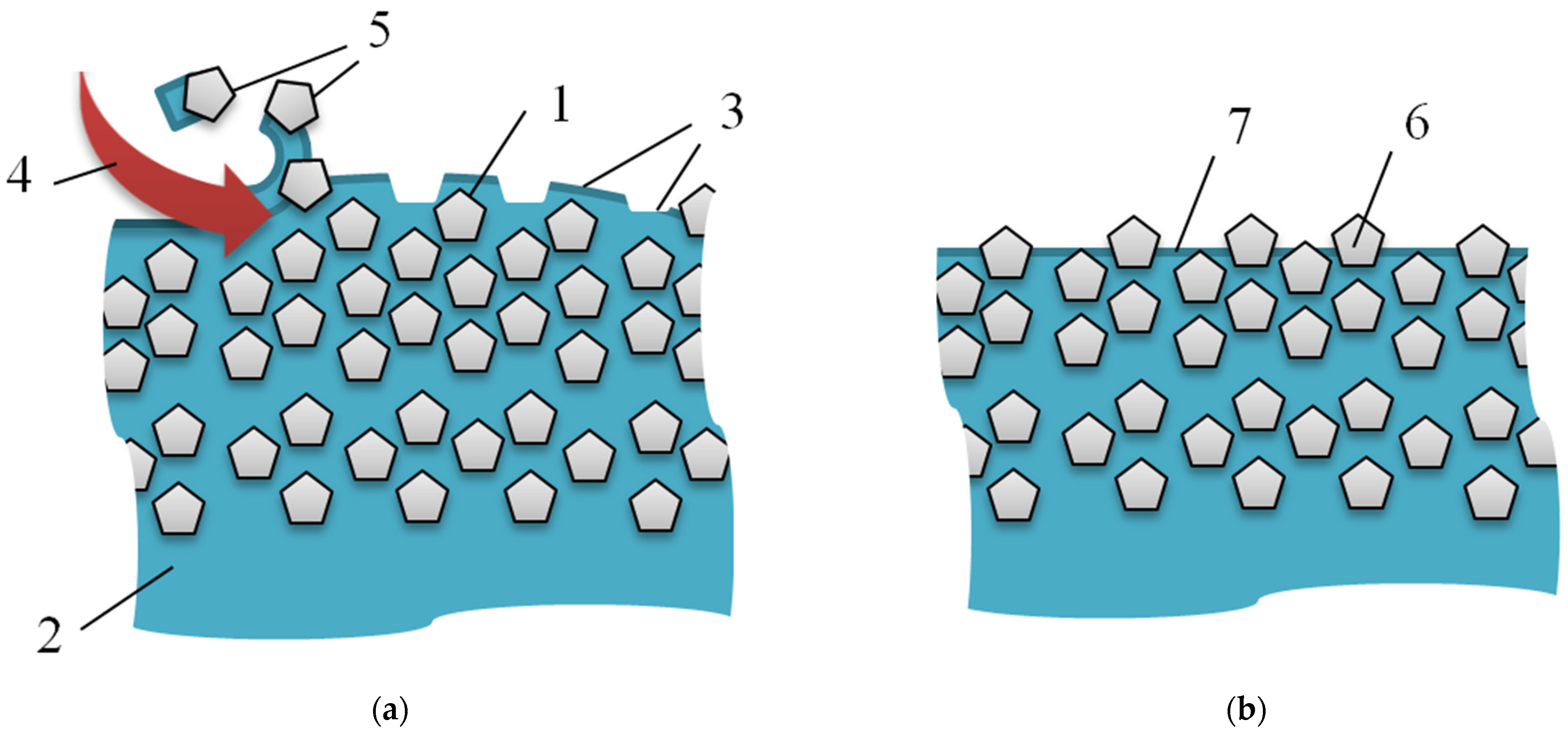

2.3. Dressing of a Polycrystalline Diamond Saw Blade

- Medium material used to dress the blade,

- Dressing modes: feed rate, rotation speed, depth of cut,

- A number of dressing passes.

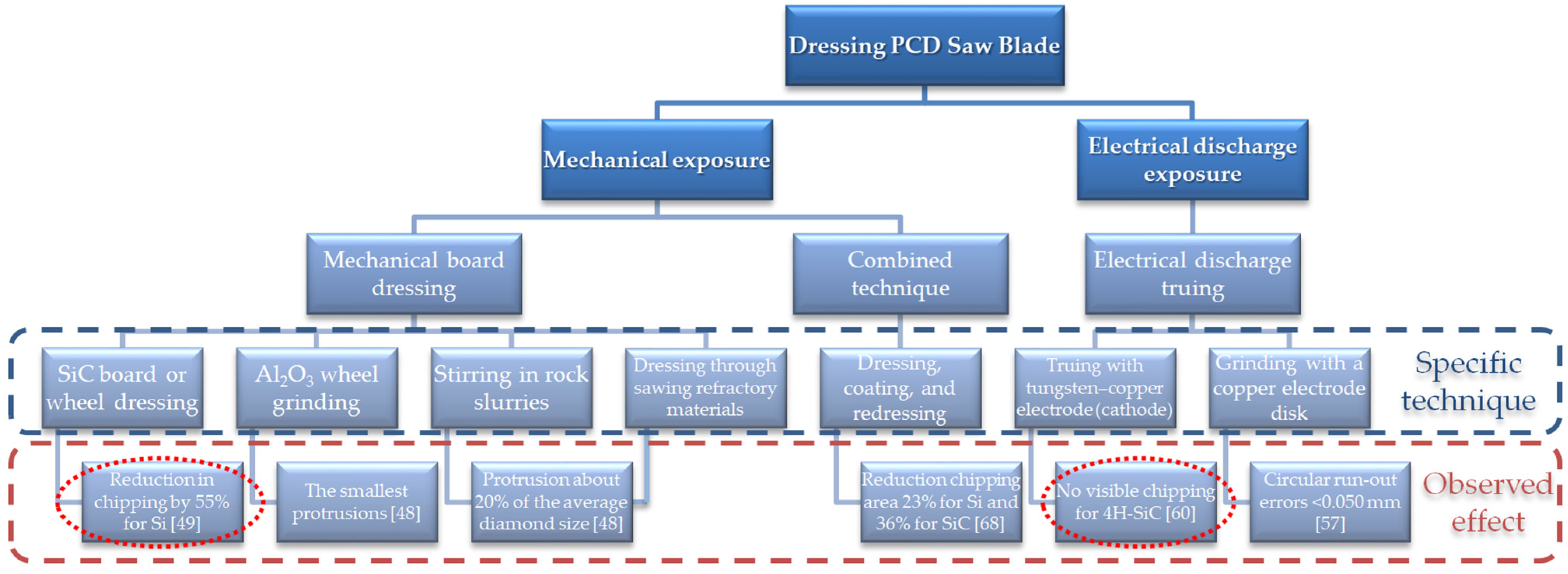

3. Methods of Polycrystalline Diamond Saw Blade Dressing

3.1. Mechanical Board Dressing

- Rough machining using a coarse-grain diamond grinding wheel;

- Semi-finishing using a fine-grain grinding wheel;

- Finishing using a fine-grain grinding wheel.

- insufficient cutting power of the second PCD saw blade;

- improper PCD saw blade dressing (grit exposure);

- improper pre-cut settings; and

- low robustness of the technological window.

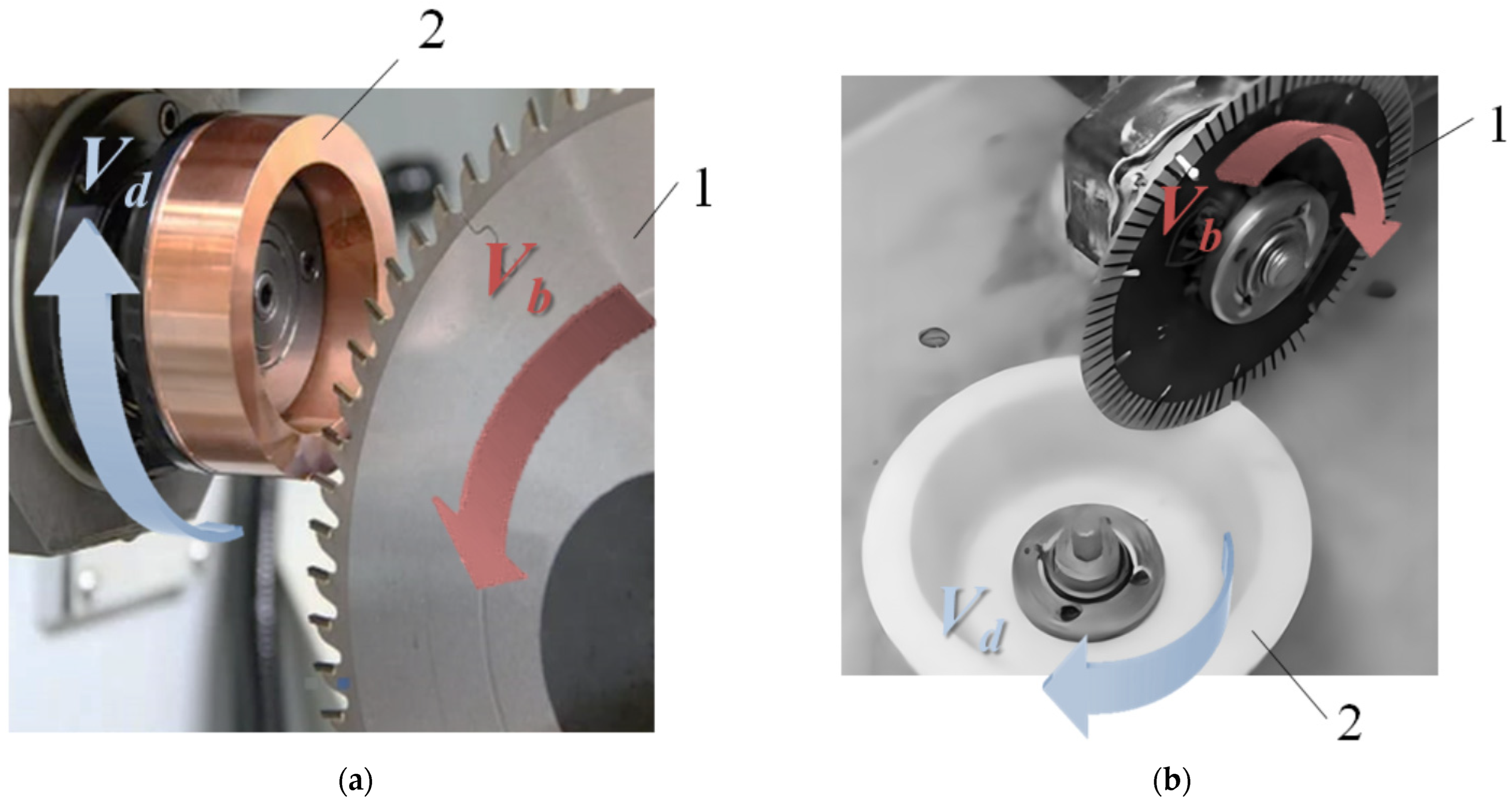

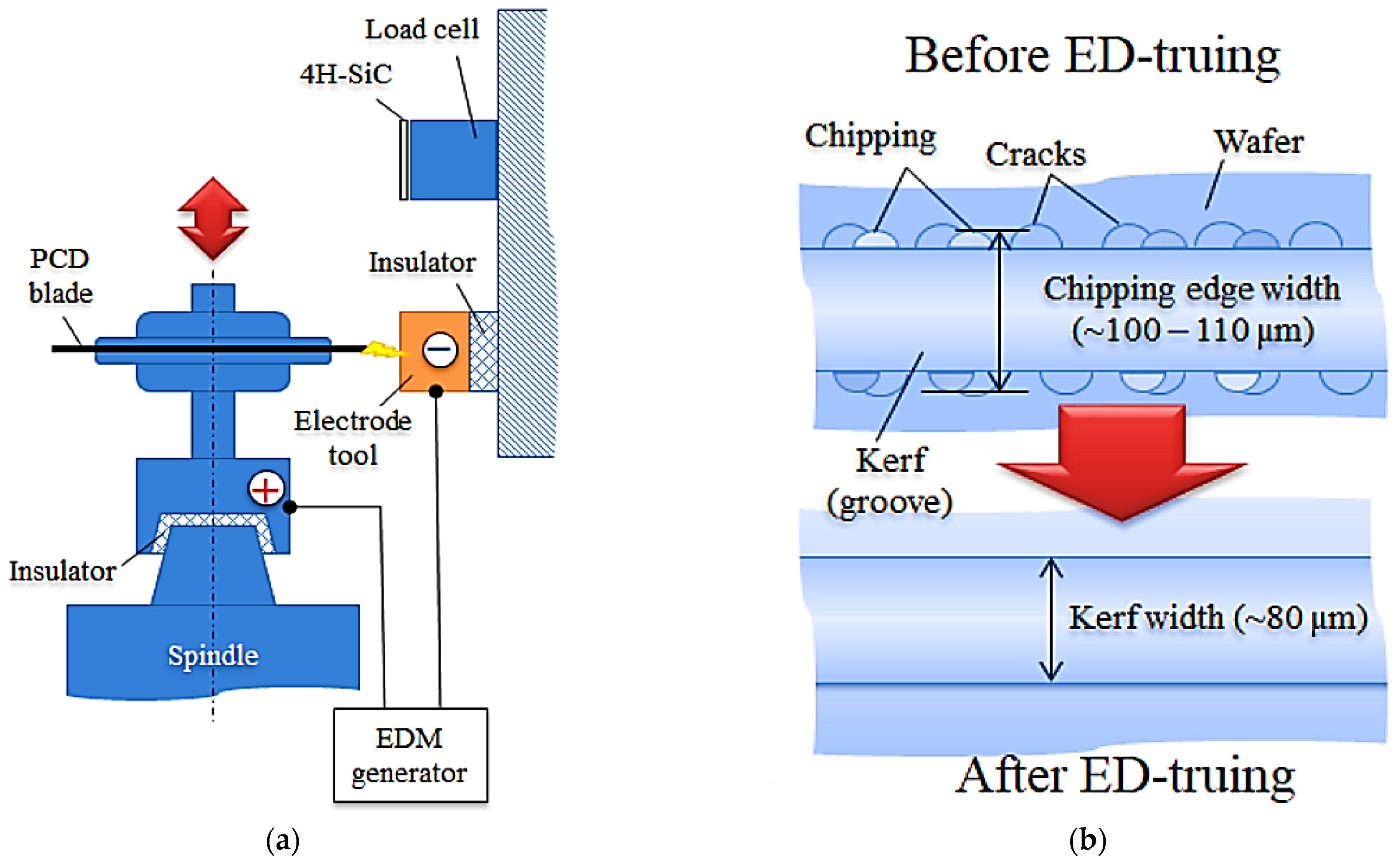

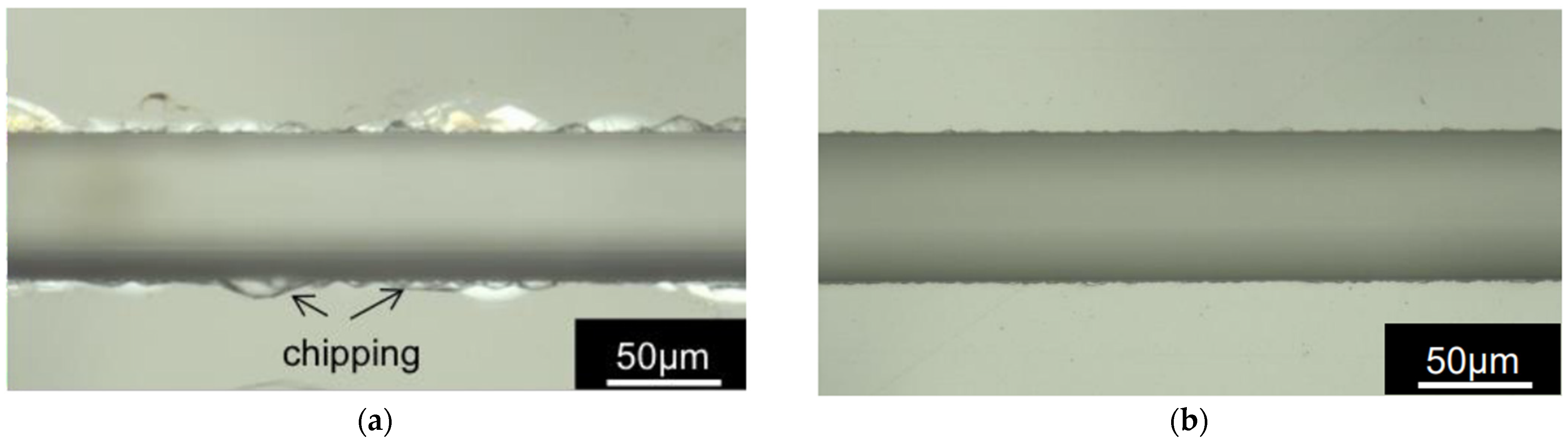

3.2. Electrical Discharge Truing/Grinding

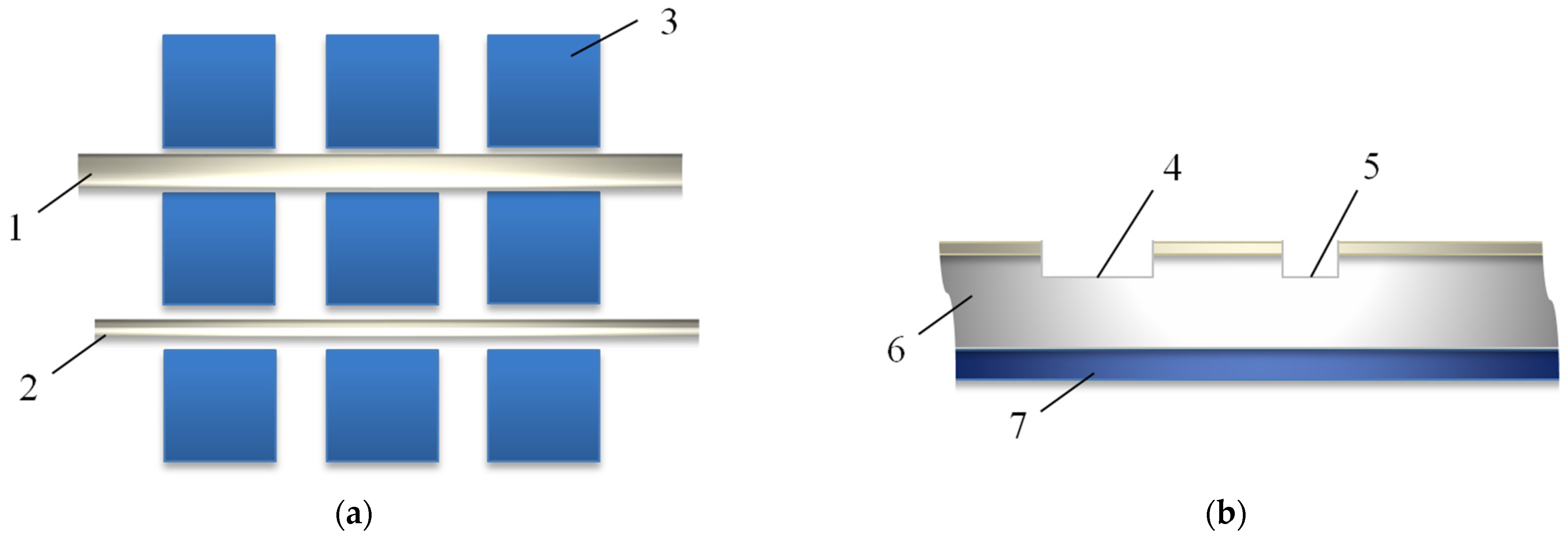

3.3. Mechanical Dressing, Coating, and Redressing Technique

- Silicon wafer (in electronics for the production of integrated circuits and in photovoltaics for traditional solar cells) of 525 µm thick (with a tolerance of ±1%), ~10.16 cm (4 in.) in diameter (with a tolerance of ±1%), surface orientation of <100> (with a tolerance of ±0.5°), p-type (contains boron as a dopant) (for Si wafer S 6075, Otto Chemie Pvt Ltd., Mumbai, India, the specific electrical resistance of more than 200 Ω·cm, roughness parameter Ra of less than 0.8 nm);

- SiC 4H-N wafer (in optoelectronics) of 350 µm thick (with a tolerance of ±25 µm), ~10.16 cm (4 in.) in diameter (with a tolerance of 0.5 mm), surface orientation of <0001> (with a tolerance of ±0.5°), 4H-polytype, n-type (for 4H SiC epitaxial wafers with a single crystal film/epitaxial layer on the SiC substrate for MOS fabrication, where wide-band semiconductor devices are made on this film and SiC is the substrate, in other words, forming heteroepitaxial structures, structures in which the growing layer differs in chemical composition from the substrate material, possible only for chemically non-interacting substances, with films of other wide-bandgap semiconductors (GaN, AlN, ZnO) on a SiC substrate, in the described case, gallium nitride (GaN) is the epitaxial layer, Xiamen Powerway Advanced Material Co., Ltd., Xiamen, China, growth method: CVD [73,74], the specific electrical resistance of 0.015–0.028 Ω·cm, roughness parameter Ra < 1 nm on the C face);

- Sapphire/PSS (in LED manufacturing, sapphire allows for the growth of GaN crystals, which emit light when an electric current is applied, and in optics, due to the high transparency and hardness, sapphire wafers serve as windows and lenses in high-pressure and high-temperature environments, as well as in infrared imaging systems) of 430 µm thick (with a tolerance of ±25 μm), ~50.8 cm (2 in.) in diameter (with a tolerance of ±0.1 mm), surface orientation of <0001> (C-plane, with a tolerance of ±0.2°), (monocrystalline Al2O3, high purity (99.999%), roughness parameter Ra 0.8–1.2 µm); the PSS pattern is 2.6 µm in height and in 2.35 µm in diameter.

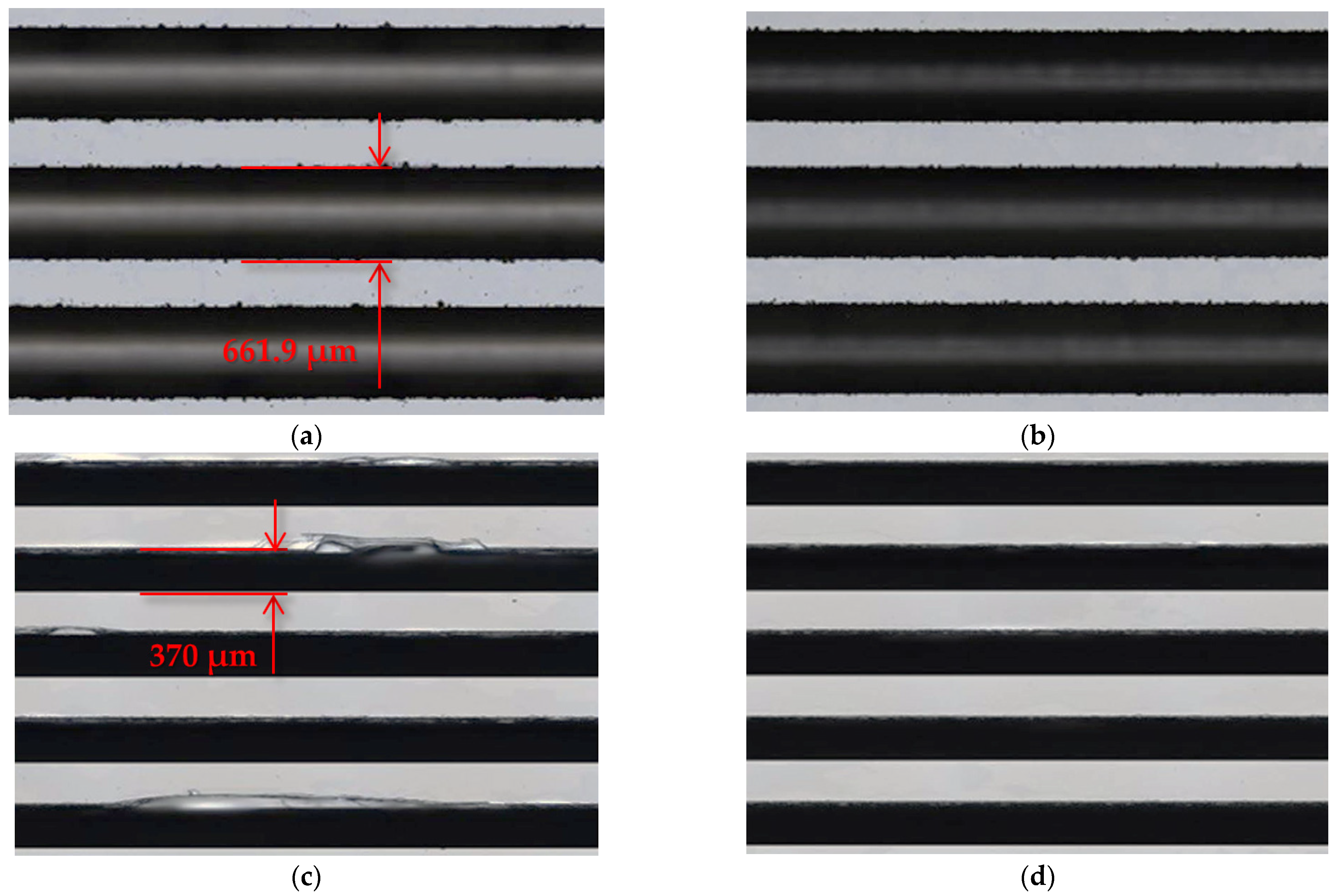

- Direction of <110> with a depth of 400 µm (2 passes of 200 µm of dicing), width of 661.9 µm, 20 kerfs for Si wafer;

- Direction of <> with a depth of 200 µm (2 passes of 100 µm of dicing), width of 370 µm, 20 kerfs for SiC wafer;

- Direction of <> with a depth of 100 µm (2 passes of 100 µm of dicing), width of 315 µm, 20 kerfs for sapphire/PSS.

4. Discussion

- In mechanical dressing, the grit size of the dressing wheel should be higher than that of the PCD saw blades (a SiC board is recommended compared to a Si wafer as a dresser [49]); the grit size of the PCD saw blade is better above >3500;

- In electrical discharge truing/grinding, the specific electrical conductivity of the electrode (cathode) should be higher than those for the bond material of the PCD saw blade (preferably a copper electrode, if possible, due to the properties: copper has high electrical and thermal conductivity, while tungsten has high brittleness, low ductility, and high abrasiveness; the electrical conductivity of tungsten is almost three times lower than that of copper [74]); the recommended factors are the discharge current of 1 A, the circuit voltage of 100 V, and the discharge duration of 0.4 μs;

- During dressing/truing the profile of the PCD saw blade on both the rake and flank faces, approximately 0.05–0.15 mm of bond material should be removed;

- Equal forces of mechanical or electrical exposure should be applied to each cutting face, receiving the same number of passes to sharpen the entire PCD saw blade evenly;

- The profile of the PCD saw blade should remain perpendicular to the dressing/truing surface to ensure proper processing;

- The cutting edge radius should not exceed 0.1–0.2 mm; thus, the dressing/truing should be monitored;

- When sharpening with coolant, the coolant flow should be over the entire grinding wheel surface to avoid thermal shock and damage to the PCD saw blade; the same applies for the electrical discharge truing; it is better when the entire PCD wheel is in dielectric fluid to avoid deviation of the shape and sizes;

- The optimal coolant flow prevents excessive wear of a dresser and damage to the cutting edge due to insufficient fluid or intermittent flow; the optimal flow in electrical discharge machining is necessary to remove debris from the interelectrode gap, avoiding short circuits.

| Dressing Parameters | PCD Saw Blade Dressing Technique | |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Dressing | Electrical Discharge Truing/Grinding | |

| Dressing tool requirements | Higher grit size (>3500), preferably SiC dresser | More electrically conductive than bond material (preferably copper; if increased rigidity is required, tungsten–copper; polarity is negative) |

| Dressing factors | Feed rate of 10–50 mm/s, rotation speed of 15–50 min−1, dress passes of 20–70 lines | Discharge current of 1 A, circuit voltage of 100 V, discharge duration of 0.4 μs, interelectrode gap of 0.050–0.075 mm |

| Coolant/working fluid | Water-based, optimal flow on the contact pad and over the entire blade | Oil-based (hydrocarbons), optimal flow in the interelectrode gap and over the entire blade |

| General safety requirements |

| |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qin, H.; Mo, Y.; Xun, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Y. A Digital-Controlled SiC-Based Solid State Circuit Breaker with Soft Switch-Off Method for DC Power System. Electronics 2019, 8, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Won, J.; Lee, J.; Lee, E. A Study on Statistical Analysis of Si-Wafer Polishing Process for the Optimum Polishing Condition. Key Eng. Mater. 2008, 389–390, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.-J.; Chen, Y.-F.; Cheng, J.-C.; Chiu, C.-L. Optimizing the dicing saw parameters of 60 μm wafer dicing street. Microsyst. Technol. 2018, 24, 3965–3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efrat, U. Optimizing the wafer dicing process. In Proceedings of the 15th IEEE/CHMT International Electronic Manufacturing Technology Symposium, Santa Clara, CA, USA, 4–6 October 1993; pp. 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debao, Y.; Fei, Q.; Jinglong, S.; Zhongkang, W.; Liang, T. Subsurface damage distribution of ground silicon wafers. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Electronic Packaging Technology, Chengdu, China, 12–15 August 2014; pp. 871–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liang, X.; Cheung, C.F.; Wang, C.; Bulla, B. Theoretical and experimental investigation of ultrasonic cutting kinematics and its effect on chip formation and surface generation in high-frequency ultrasonic vibration-assisted diamond cutting. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 5662–5676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Zhu, X.; Chen, J.; Tao, P.; Wu, X. Investigation on the Edge Chipping in Ultrasonic Assisted Sawing of Monocrystalline Silicon. Micromachines 2019, 10, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuegl, M.; Mackh, G.; Meissner, E.; Frey, L. Assessment of dicing induced damage and residual stress on the mechanical and electrical behavior of chips. In Proceedings of the IEEE 65th Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), San Diego, CA, USA, 26–29 May 2015; pp. 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wang, H.; Peng, S.; Cao, Q. Precision Layered Stealth Dicing of SiC Wafers by Ultrafast Lasers. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ma, Z.; Yan, Y.; Yuan, D.; Wang, Y. Study on the Low-Damage Material Removal Mechanism of Silicon Carbide Ceramics Under Longitudinal–Torsional Ultrasonic Grinding Conditions. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Xue, W.; Lou, W.; Liu, M.; Feng, H.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; Wu, S. Study on Anisotropic Mechanical Properties of Single-Crystal Silicon at Different Strain Rates. Micromachines 2025, 16, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.Y.; Wang, Z.W. Studies of chipping mechanisms for dicing silicon wafers. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2008, 35, 1206–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.J.; Billingsley, S.R.; Miura, S. Grinding induced subsurface cracks in silicon wafers. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 1999, 39, 1103–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-W.; Cheng, M.-H. Investigation of chipping and wear of silicon wafer dicing. J. Manuf. Process. 2014, 16, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainth, S.; Sharma, P.; Diwan, P.K.; Pandey, O.P. Shaping the Future: Innovations in Silicon Wafer Production and Finishing. Silicon 2024, 16, 6479–6497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinze, P.; Amberger, M.; Chabert, T. Perfect chips: Chip-side-wall stress relief boosts stability. Future Fab Int. 2008, 25, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Zhu, W.; Li, X.; Cao, W. Designing and Application of Modified SCSO-Based LADRC Controller for Dicing Saw Chuck Table Systems. J. Circuits Syst. Comput. 2024, 33, 2450204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, J.; Gong, Y.; Wang, K. Wear behavior and impact breakage characterization of PCD teeth of circular saw blades during high-speed sawing of hard aluminum alloy. Wear 2024, 556–557, 205534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Hu, J.; Wen, Q.; Cheng, K.; Zheng, P. Investigation on an Innovative Method for High-Speed Low-Damage Micro-Cutting of CFRP Composites with Diamond Dicing Blades. Materials 2018, 11, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Riaz, A.; Chohan, B.S. Precision Machining by Dicing Blades: A Systematic Review. Machines 2023, 11, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolotov, A.N.; Novikov, V.V.; Novikova, O.O. Mineral-ceramic composite material: Synthesis and frictional properties. Obrab.–Met. Work. Mater. Sci. 2020, 22, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, C.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zakharov, O.; Geng, Y.; Zhang, F. Nanoscale insight into brittle-to-ductile transition mechanism of 4H-SiC in single-grit nanogrinding. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 302, 110579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Qiu, S.; Huo, Y.; Zhang, N. High-speed dicing of silicon wafers conducted using ultrathin blades. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 66, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, L.A.O.; Foschini, C.R.; Jasinevícius, R.G.; Fortulan, C.A. Precision dicing of hard materials with abrasive blade. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 86, 2885–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Z.; Yuan, X.; Zhuang, P.; Wu, T.; Feng, S. Study on precision dicing process of SiC wafer with diamond dicing blades. Nanotechnol. Precis. Eng. 2021, 4, 033004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, S.; Morsbach, C.; Rissing, L. Ultra-precision dicing and wire sawing of silicon carbide (SiC). Microelectron. Eng. 2011, 88, 2500–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejun, K.; Wen, Z.; Ling, Z. Friction-Wear Behaviors of Chemical Vapor Deposited Diamond Films at High Temperatures. J. Superhard Mater. 2019, 41, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekimov, E.A.; Sidorov, V.A.; Karabutov, A.A.; Shiryaev, A.A.; Drozdova, E.I.; Lukina, I.N.; Chernogorova, O.P. Electrical Transport, Mechanical and Tribological Properties of Composites Produced by Sintering Shock-Synthesized Nanopolycrystalline Diamond Particles. Inorg. Mater. 2024, 60, 1585–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Zhang, C.; Li, G.; Song, C.; Qin, W.; Wang, T. Mechanisms Behind Graphitization Modification in Polycrystalline Diamond by Nanosecond Pulsed Laser. Materials 2024, 17, 6200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Deng, F.; Deng, W.; Xi, P.; Tan, C.; Lu, X. Optimization of Designing on Cutter Parameters of PCD Saw Blades by Simulation Analysis. J. Superhard Mater. 2019, 41, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, A.T. Dicing advanced materials for microelectronics. In Proceedings of the International Symposium and Exhibition on Advanced Packaging Materials Processes Properties and Interfaces, Irvine, CA, USA, 16–18 March 2005; pp. 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansare, V.V.; Gadakh, V.S.; Patil, S.S. Selection of Multi-point Diamond Dresser for Grinding Process Using Grey Relation Analysis. In Advances in Manufacturing Systems; Kumar, S., Rajurkar, K.P., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.L.; Ge, P.Q.; Bi, W.B.; Zhang, L.; Wang, D.X.; Zhang, Y. 2D/3D ground surface topography modeling considering dressing and wear effects in grinding process. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2013, 74, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Warkentin, A.; Bauer, R.; Gong, Y. Investigation of different grain shapes and dressing to predict surface roughness in grinding using kinematic simulations. Precis. Eng. 2013, 37, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.K.; Mahmud, M.N. Optimization of Semiconductor Device Packaging Singulation Process. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 530, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Shan, C.; Huang, C.; Wang, F. A State-of-the-Art Review of Fracture Toughness of Silicon Carbide: Implications for High-Precision Laser Dicing Techniques. Processes 2024, 12, 2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Li, K.; Dou, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, B. High-Speed Dicing of SiC Wafers with 0.048 mm Diamond Blades via Rolling-Slitting. Materials 2022, 15, 8083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Jiang, X.; Cao, Z.; Liu, H.; Li, D. Simulation and Analysis on the Influence of Diamond Blade Cutting Parameters of Grinding Wheel Dicing Saw. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2179, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, G.; Burckhardt, S. Automatic polishing machine for economic saw blade manufacture. Ind. Diam. Rev. 2001, 61, 135. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Du, M.; Feng, M.; Bao, R.; Jing, L.; Hong, Q.; Xiao, L.; Liu, J. Recent Advances in Precision Diamond Wheel Dicing Technology. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.F.; Abrão, B.S.; Abrão, A.S.; Machado, A.R.; Jackson, M.J.; Hassui, A.; da Silva, R.B. Influence of grinding wheel conditioning on the grindability of Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 125, 1531–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Tian, Y.; Han, J.; Li, L.; Gu, Z.; Hu, X. Development of a new high-shear and low-pressure grinding wheel and its grinding characteristics for Inconel718 alloy. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2022, 35, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.E.; Chin, F.K. Saw chipping improvement to achieve defect free bare die products. In Proceedings of the IEEE CPMT International Electronics Manufacturing Technology IEMT Symposium, Johor, Malaysia, 11–13 November 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, A.; Ehorn, J.; Brand, M.; Bassett, C. Review of wafer dicing techniques for via-middle process 3DI/TSV ultrathin silicon device wafers. In Proceedings of the Electronic Components and Technology Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 26–29 May 2015; pp. 1436–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yuan, L.; Xia, H. The Challenges of Wafer Blade Dicing by Minimize Die Size. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Electronic Packaging Technology ICEPT, Tianjin, China, 7–9 August 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, M.R.; Cheong, K.Y.; Hassan, Z. Fracture strength and microstructural study of ultrathin Si die with Cu backside layer diced with picosecond laser. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 759, 785–796, Erratum in Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 761, 138030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2019.138030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Xu, X. Design of a machine for high efficiency truing and dressing of diamond saw blade. Jingangshi Yu Moliao Moju Gongcheng/Diam. Abras. Eng. 2009, 3, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.Q.; Li, Y.; Xu, X.P. A comparative study on the dressing of metal-bonded diamond saws. Key Eng. Mater. 2006, 304–305, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.W.; Yow, K.Y.; Khoo, R. Developments of blade dressing technique using SiC board for C90 low-k wafer sawing. In Proceedings of the IEEE 13th Electronics Packaging Technology Conference, Singapore, 7–9 December 2011; pp. 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.N.; Volosova, M.A.; Okunkova, A.A.; Fedorov, S.V.; Hamdy, K.; Podrabinnik, P.A.; Pivkin, P.M.; Kozochkin, M.P.; Porvatov, A.N. Wire Tool Electrode Behavior and Wear under Discharge Pulses. Technologies 2020, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnik, Y.A.; Kozochkin, M.P.; Porvatov, A.N.; Okunkova, A.A. On Adaptive Control for Electrical Discharge Machining Using Vibroacoustic Emission. Technologies 2018, 6, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.N.; Kozochkin, M.P.; Fedorov, S.V.; Porvatov, A.N.; Okunkova, A.A. Study of Electroerosion Processing by Vibroacoustic Diagnostic Methods. Meas. Tech. 2015, 58, 878–884, Erratum in Meas. Tech. 2015, 58, 1186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11018-015-0864-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.N.; Nadykto, A.B.; Volosova, M.A.; Zelensky, A.A.; Pivkin, P.M. WEDM as a Replacement for Grinding in Machining Ceramic Al2O3-TiC Cutting Inserts. Metals 2021, 11, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.N.; Kozochkin, M.P.; Porvatov, A.N.; Volosova, M.A.; Okunkova, A.A. Electrical discharge machining of ceramic nanocomposites: Sublimation phenomena and adaptive control. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, L.A.; Montes-Morán, M.A.; Peretyagin, P.Y.; Vladimirov, Y.G.; Okunkova, A.; Moya, J.S.; Torrecillas, R. Zirconia–alumina–nanodiamond composites with gemological properties. J. Nanopart. Res. 2014, 16, 2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volosova, M.; Okunkova, A.; Peretyagin, P.; Melnik, Y.A.; Kapustina, N. On Electrical Discharge Machining of Non-Conductive Ceramics: A Review. Technologies 2019, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ye, P.; Wang, C. Edge fabrication and process optimization of precision woodworking PCD millers with disk electrical discharge machining. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 85, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulshrestha, A.; Mertiya, A.; Unune, D.; Dargar, A. A review on electrical discharge grinding: Current status and future perspectives. Surf. Rev. Lett. 2023, 30, 2330003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Lim, C.; Ding, S.L.; Rahim, M.Z.; Brandt, M.; Mo, J. Experimental Study of Wheel Rotating Speed Effect on Electrical Discharge Grinding. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 697, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Yanagida, D.; Minami, H.; Izumi, Y. Electrical discharge truing of a PCD blade tool on a dicing machine. Procedia CIRP 2020, 95, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaurasia, S.; Debnath, K. Performance Analysis of Different Tool Materials During µ-Electrical Discharge Milling of NiTi Shape Memory Alloy. In Micro Manufacturing; Jain, V.K., Doloi, B., Rao, U.S., Misra, J.P., Eds.; AIMTDR-2023, Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2026; pp. 145–155. [Google Scholar]

- Chemeris, V.S. Wear Resistance of Electrodes of Arc-Extinguishing Devices of SF6 Gas Circuit Breakers. Russ. Electr. Eng. 2025, 96, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, S.A.; Zakharov, A.G.; Pisarenko, I.V. Influence of electrical machining of the surface of a semiconductor sensitive layer of a gas sensor on its electrical properties. Surf. Eng. Appl. Electrochem. 2014, 50, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bańkowski, D.; Młynarczyk, P. Influence of EDM Process Parameters on the Surface Finish of Alnico Alloys. Materials 2022, 15, 7277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasem, I.; Alsakarneh, A. Machine Learning-Based Prediction of EDM Material Removal Rate and Surface Roughness. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmiris-Obratański, P.; Papazoglou, E.L.; Leszczyńska-Madej, B.; Zagórski, K.; Markopoulos, A.P. Surface and Subsurface Quality of Titanium Grade 23 Machined by Electro Discharge Machining. Materials 2022, 15, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttamara, A.; Nakwong, P. Enhancing Wire-EDM Performance with Zinc-Coated Brass Wire Electrode and Ultrasonic Vibration. Micromachines 2023, 14, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.P.; Lai, B.-Z.; Yiu, P.; Shen, Y.-L.; Chang, C.-W. Metallic glass coating for improving diamond dicing performance. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volosova, M.; Grigoriev, S.; Metel, A.; Shein, A. The Role of Thin-Film Vacuum-Plasma Coatings and Their Influence on the Efficiency of Ceramic Cutting Inserts. Coatings 2018, 8, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metel, A.S.; Grigoriev, S.N.; Melnik, Y.A.; Bolbukov, V.P. Broad beam sources of fast molecules with segmented cold cathodes and emissive grids. Instrum. Exp. Tech. 2012, 55, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.; Melnik, Y.; Metel, A. Broad fast neutral molecule beam sources for industrial-scale beam-assisted deposition. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2002, 156, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkinazi, E.E.; Fedorov, S.V.; Martyanov, A.K.; Sedov, V.S.; Khmelnitsky, R.A.; Ralchenko, V.G.; Ryzhkov, S.G.; Khomich, A.A.; Mosyanov, M.A.; Grigoriev, S.N.; et al. Wear of Carbide Plates with Diamond-like and Micro-Nano Polycrystalline Diamond Coatings during Interrupted Cutting of Composite Alloy Al/SiC. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2023, 7, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Gao, J.; Liang, W.; Miao, Q.; Jia, F.; Chang, X.; Lin, H. A Comparison of the Tribological Properties of SiC Coatings Prepared via Atmospheric Plasma Spraying and Chemical Vapor Deposition for Carbon/Carbon Composites. Lubricants 2024, 12, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidyuk, T.M.; Ukhina, A.V.; Gavrilov, A.I.; Shikalov, V.S.; Anisimov, A.G.; Lomovsky, O.I.; Dudina, D.V. Synthesis of Tungsten Carbides in a Copper Matrix by Spark Plasma Sintering: Microstructure Formation Mechanisms and Properties of the Consolidated Materials. Materials 2023, 16, 5385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworska, L.; Klimczyk, P.; Szutkowska, M.; Putyra, P.; Sitarz, M.; Cygan, S.; Rutkowski, P. Thermal resistance of PCD materials with borides bonding phase. J. Superhard Mater. 2015, 37, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Specific Technique | Workpiece | Dicing Machine | PCD Saw Blade Parameters | Dressing Tool | Chipping Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [43] | Two-wheel technique (preliminary dicing and dicing) | Si wafer | DISCO sawing machine with automated vision | Not provided | Not provided | The chipping was worse than before |

Combined approach:

| Si wafer performance improved from 90% to 99.5% (the detected chipping of more than 70 µm reduced from 10% to 0.5%); chipping size reduced from 70 µm to 15 µm (78.6%) | |||||

| Lower feed rate | The chipping was worse than before | |||||

| [48] | Stirring in rock slurries | Ceramic materials | Not provided | Iron- (~50% wt.), copper-, tin-, cobalt- and nickel-based bond, PCD of 40/45 (355–425 μm) | Rock slurries (several hours of stirring) | The optimal performance achieved by dressing with SiC wheels and by sawing refractory materials: the height of grit protrusion of ~20% of the diamond average size |

| Grinding with Al2O3 wheels | M7115 grinder machine | Vitrified Al2O3 wheel (width of 24.5 mm, no coolant) | ||||

| Dressing with SiC wheels | Experimental machine with elastic base | Vitrified SiC wheel | ||||

| Dressing through sawing refractory materials | Experimental sawing machine | Synthetic refractory bricks (50 cm in length, tap water as cutting fluid) | ||||

| [49] | Dressing by SiC dresser board | Si wafer (CMOS 90 nm low-k wafer), ø300 mm, 280 µm thick, saw street of 80 µm | Production line for C90 low-k products in BGA and QFP line | 3500 grit size, standard and soft bond | SiC dresser board (<3500 grit size) | Did not show any positive effect (10 chippings per 10 cut lines) |

| SiC dresser board (>3500 grit size) |

| |||||

| Dressing by Si wafer | Si wafer |

| Ref. | Technique | Workpiece | PCD Saw Blade Parameters | Dressing Tool | Dicing Factors | Chipping Effect | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cutting Speed vc, m/s | Feed Rate f, mm/min | Depth of Cut ap, µm | Spindle Speed n, rpm | ||||||

| [49] | SiC board mechanical dressing | Si wafer (CMOS 90 nm low-k wafer), ø300 mm, 280 µm thick, saw street of 80 µm | 3500 grit size, standard and soft bond | SiC dresser board | Not provided | Not provided | 60–160 µm (for Si wafer) and 25–50 µm (for dicing tape) | 45,000–55,000 and 25,000–35,000 for two saw blades (Z1 and Z2) | Improved top side chipping performance for >3500 grit size (0.77% at 31 passes and 1.73% for control Si wafer at 2500 passes); dressing time less than 1 h comparing to dressing by a Si wafer |

| [60] | Electrical discharge truing with a tungsten–copper electrode wheel | 4H-SiC, 0.34 mm thick, kerf width of 80 µm | Co binding, 50 μm thick, ø50 mm, the diamond grain size of 0.5 μm, (+) polarity | Tungsten–copper electrode wheel, (−) polarity, current: 1 A, voltage: 100 V, pulse duration: 0.4 μs; any dielectric | ~1260 for dicing and truing * | 15 | 50 | 8000 for dicing and truing | No visible chipping in 20 m of dicing after ED-truing, before ED-truing chipping size was 20–30 µm at each side |

| [68] | “Dressing—coating—redressing” technique | Si wafer, SiC wafer, sapphire substrate, patterned sapphire substrates | Fe-Co-Sn bind, 22/36 μm grit, ø58 mm, 0.89 mm thick, 60° chamfer | WA600L whetstone | ~6400 for dressing; ~4600 for dicing * | 300 ** | Not provided | 35,000 for dressing; 25,000 for dicing | Chipping area fractions reduced by 23% for Si, 36% for SiC, 45% for sapphire, 33% for PSS |

| Parameters | PCD Saw Blade Dressing Techniques | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Dressing | Electrical Discharge Truing/Grinding | Mechanical Dressing + Coating + Redressing | |||||||

| Reference | [49] | [60] | [68] | ||||||

| Workpiece | Si wafer | Polymorph of silicon carbide (4H-SiC) | Si wafer | SiC | |||||

| Die street width, µm | 80 | (50) * | ~662 | 370 | |||||

| Dressing tool | Si wafer | SiC board dresser, grit size < 3500 | SiC board dresser, grit size > 3500 | No tool | Tungsten–copper electrode wheel | No tool | Whetstone + Zr-coating | No tool | Whetstone + Zr-coating |

| Chipping size, µm | 120 (1 chipping per 10 lines) | 100–120 (both street edges, 10 chippings per 10 lines) | 60–80 (1 chipping per 10 lines) | 8–12 | 0 | 55.2 | 25 | 150 | 0 |

| Chipping width, µm | 205 | 300 | 145–170 | 60–68 | (50) | ~720 | ~690–715 | 520 | 370 |

| Percent of chipping **, % | 156 | 275 | 81–112.5 | 20–36 | 0 | 8.8 | 4.2–8.0 | 40.5 | 0 |

| Effect of dressing technique ***, % | 43–75 (comparing Si wafer dressing with SiC board dresser, grit size > 3500) | 20–36 | 0.8–4.5 | 40.5 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grigoriev, S.N.; Okunkova, A.A.; Volosova, M.A.; Hamdy, K.; Metel, A.S. Influence of Dressing Methods on Chipping Size During Si and SiC Die Singulation: A Review. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120405

Grigoriev SN, Okunkova AA, Volosova MA, Hamdy K, Metel AS. Influence of Dressing Methods on Chipping Size During Si and SiC Die Singulation: A Review. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing. 2025; 9(12):405. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120405

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrigoriev, Sergey N., Anna A. Okunkova, Marina A. Volosova, Khaled Hamdy, and Alexander S. Metel. 2025. "Influence of Dressing Methods on Chipping Size During Si and SiC Die Singulation: A Review" Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 9, no. 12: 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120405

APA StyleGrigoriev, S. N., Okunkova, A. A., Volosova, M. A., Hamdy, K., & Metel, A. S. (2025). Influence of Dressing Methods on Chipping Size During Si and SiC Die Singulation: A Review. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, 9(12), 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120405