The Effects of Melting Methods and In-House Recycled Content on Climate Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

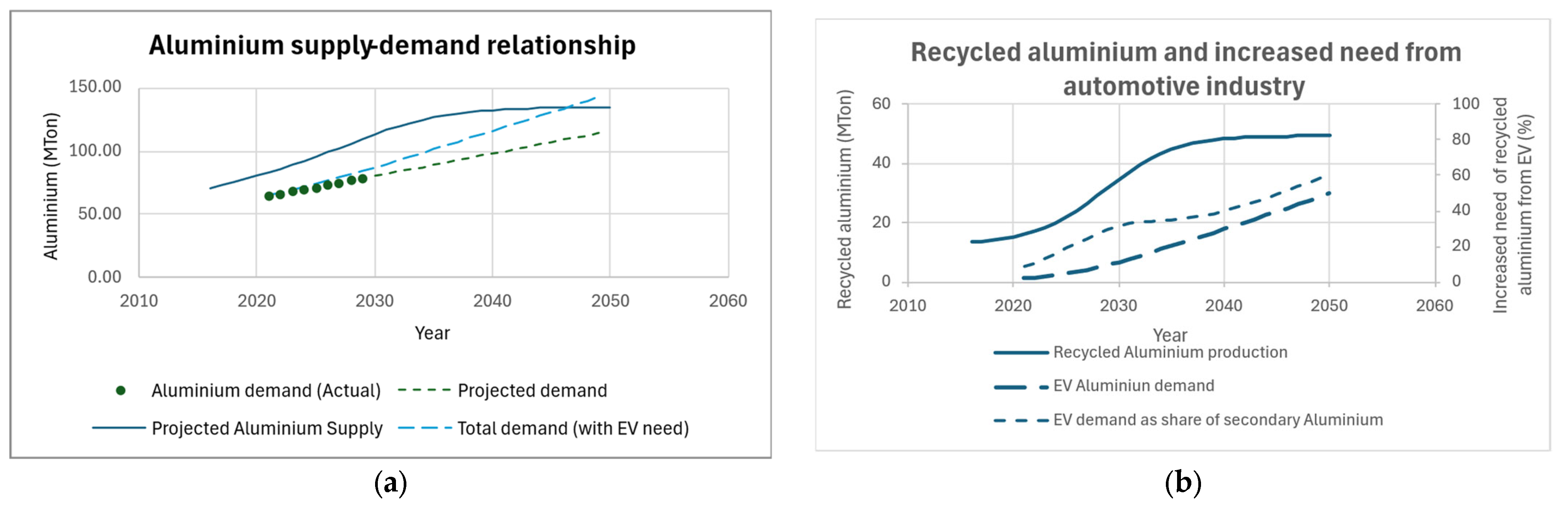

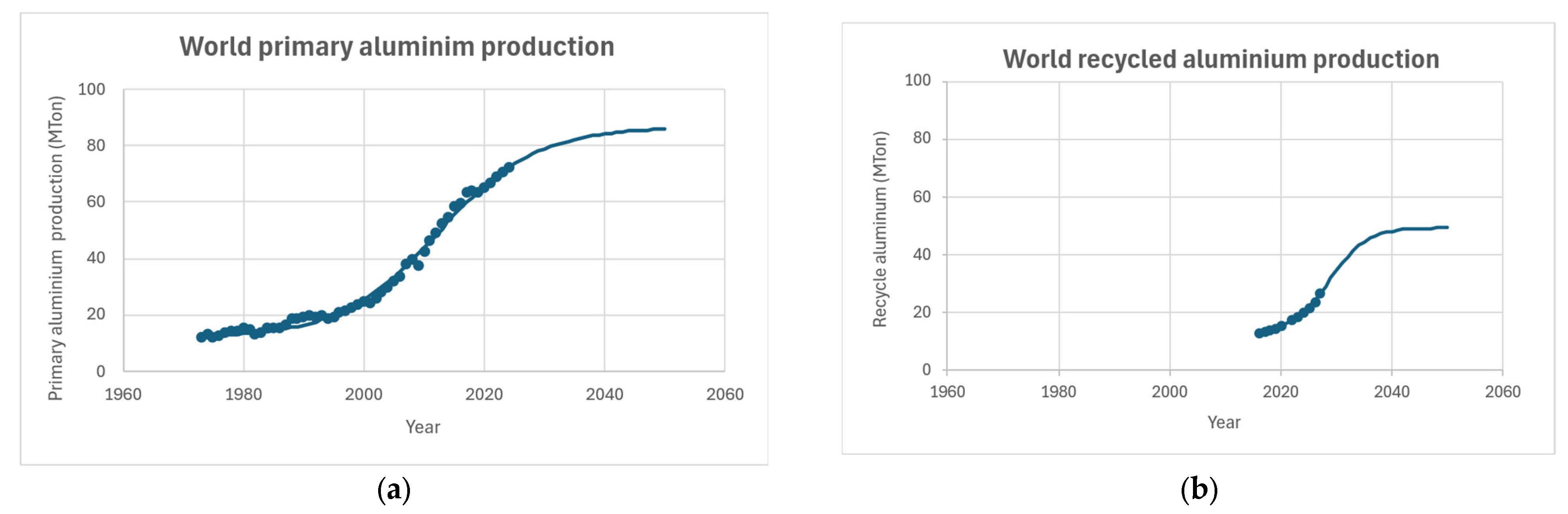

3.1. Aluminium Supply-And-Demand Balance

3.2. Foundry Climate Impact and Material Efficiency Effects

3.2.1. Material Efficiency Effects

3.2.2. Embodied Energy Effects

3.2.3. Climate Impact Effects

3.2.4. Component Quality and Performance Perspectives

- Coarser grains and irregularly sized dendritic cells due to a loss of inoculation effects;

- Increased porosity;

- Coarser intermetallics;

- Burn-off of both alloying and tramp elements.

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

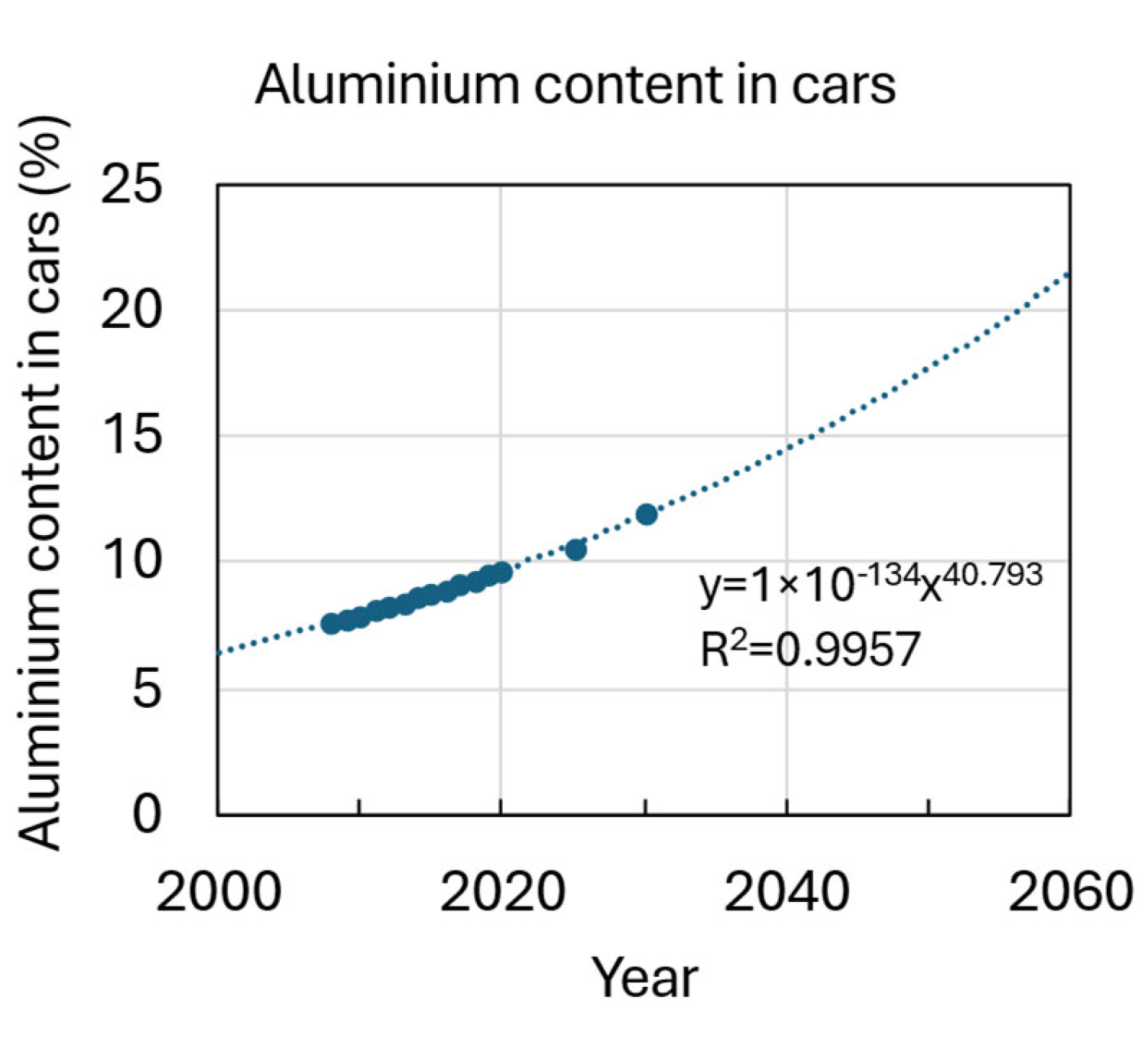

Appendix A.1.1. Automotive Market Evolution

Appendix A.1.2. Automotive Market, Electrification, and Giga/Mega-Casting

| Scenario, S | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Si | Fe | Cu | Mn | Mg | Zn | Al | |

| ICE | 5.16 | 0.52 | 0.72 | 0.35 | 0.75 | 0.41 | Bal. |

| EV | 1.38 | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.22 | 1.46 | 0.13 | Bal. |

| EV + Mega-casting | 3.54 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 1.02 | 0.05 | Bal. |

References

- Jule, G. Charney Carbon Dioxide and Climate: A Scientific Assessment; National Academy of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ripple, W.J.; Wolf, C.; Gregg, J.W.; Levin, K.; Rockström, J.; Newsome, T.M.; Betts, M.G.; Huq, S.; Law, B.E.; Kemp, L.; et al. World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency 2022. Bioscience 2022, 72, 1149–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S.; Bullard, R.; Buonocore, J.J.; Donley, N.; Farrelly, T.; Fleming, J.; González, D.J.X.; Oreskes, N.; Ripple, W.; Saha, R.; et al. Scientists’ Warning on Fossil Fuels. Oxf. Open Clim. Change 2025, 5, kgaf011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpprecht, C.; Miranda Xicotencatl, B.; van Nielen, S.; van der Meide, M.; Li, C.; Li, Z.; Tukker, A.; Steubing, B. Future Environmental Impacts of Metals: A Systematic Review of Impact Trends, Modelling Approaches, and Challenges. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 205, 107572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, B.; Torrance, A.W.; Ripple, W.J. Scientists’ Warning on Technology. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burggräf, P.; Bergweiler, G.; Kehrer, S.; Krawczyk, T.; Fiedler, F. Mega-Casting in the Automotive Production System: Expert Interview-Based Impact Analysis of Large-Format Aluminium High-Pressure Die-Casting (HPDC) on the Vehicle Production. J. Manuf. Process 2024, 124, 918–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartlieb, A.; Hartlieb, M. Light Metal Age June 2023, pp 18. Available online: https://www.lightmetalage.com/news/industry-news/automotive/the-impact-of-giga-castings-on-car-manufacturing-and-aluminum-content/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Rolseth, A.; Carlsson, M.; Ghassemali, E.; Lluís, P.; Jarfors, A.E.W. Impact of Functional Integration and Electrification on Aluminium Scrap in the Automotive Sector: A Review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 205, 107532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cischino, E.; Di Paolo, F.; Mangino, E.; Pullini, D.; Elizetxea, C.; Maestro, C.; Alcalde, E.; Christiansen, J.D. An Advanced Technological Lightweighted Solution for a Body in White. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 14, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timelli, G.; Bonollo, F. Fluidity of Aluminium Die Castings Alloy. Int. J. Cast Met. Res. 2007, 20, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarfors, A.E.W.; Du, A.; Yu, G.; Zheng, J.; Wang, K.; Wannasin, J. Semisolid Materials Processing: A Sustainability Perspective. Solid State Phenom. 2022, 327, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdeş, H.; Tiryakiŏglu, M. On the Relationship between Structural Quality Index and Fatigue Life Distributions in Aluminum Aerospace Castings. Metals 2016, 6, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uludag, M.; Dis, D.; Tiryakioglu, M. On the Interpretation of Melt Quality Assessment of A356 Aluminum Alloy by the Reduced Pressure Test: The Bifilm Index and Its Physical Meaning. Int. J. Met. 2018, 12, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allwood, J.M.; Ashby, M.F.; Gutowski, T.G.; Worrell, E. Material Efficiency: A White Paper. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 362–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, S. Sustainable Manufacturing Through Material Efficiency Management; Akademin foör Innovation, Design Och Teknik: Eskilstuna, Sweden, 2018; Mälardalen University Press Dissertations No. 253; ISBN 978-91-7485-373-5. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1179801/FULLTEXT02.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Hellberg, G. Materials and Manufacturing, Materials Cleanliness Assessment in Rheocasting. Master Thesis, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden, 2022. ISRN: JU-JTH-PRU-2-20220315. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanoff, T.; Tiryakioğlu, M.; Liljenfors, T.; Jarfors, A.E.W.; Seifeddine, S.; Ghassemali, E. On the Effectiveness of Rotary Degassing of Recycled Al-Si Alloy Melts: The Effect on Melt Quality and Energy Consumption for Melt Preparation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Precision Business Insights. Production Volume of Recycled Aluminum Worldwide from 2016 to 2020, with a Forecast from 2022 to 2027, by Region (in 1000 Metric Tons). Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1113774/recycled-aluminum-production-worldwide-by-region/ (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- International Aluminium Primary Aluminium Production. Available online: https://international-aluminium.org/statistics/primary-aluminium-production/?publication=primary-aluminium-production&filter=%7B%22row%22%3A85%2C%22group%22%3Anull%2C%22multiGroup%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22dateRange%22%3A%22monthly%22%2C%22monthFrom%22%3A2%2C%22mo (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Jarfors, A.E.W.; Bogdanoff, T.; Lattanzi, L. Functionally Integrated Castings (Giga-Castings) for Body in White Applications: Consequences for Materials Use and Mix in Automotive Manufacturing. Matériaux Tech. 2025, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista Passenger Cars—Worldwide. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/mmo/passenger-cars/worldwide?currency=USD (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Carlier, M. Impact of COVID-19 on the Automotive Industry Worldwide—Statistics & Facts. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/8749/impact-of-covid-19-on-the-automotive-industry-worldwide/#topicOverview (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Statista Research Department Projected Aluminum Consumption Worldwide 2021–2029. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/863681/global-aluminum-consumption/ (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Ansys® GRANTA Research Selector, 2024; ANSYS, Inc.: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2024.

- Thermo-Calc TACAL8.2. Available online: https://thermocalc.com/products/databases/steel-and-fe-alloys/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Mehrabi, H.; Jolly, M.; Salonitis, K. Road-Mapping Towards a Sustainable Lower Energy Foundry; Setchi, R., Howlett, R.J., Liu, Y., Theobald, P., Eds.; Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 52, ISBN 978-3-319-32096-0. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J. Complete Casting Handbook Metal Casting Processes, Metallurgy, Techniques and Design, 2nd ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-0-444-63509-9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Liljenfors, T.; Jansson, S.; Jonsson, S.; Jarfors, A.E.W. Effect of Na-Based Flux on Melt Quality Assessment of 46,000 Alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 1830–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Energy Security 6 Net-Zero Greenhouse Gas Reporting: Conversion Factors. 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/greenhouse-gas-reporting-conversion-factors-2024 (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Elsayed, M.; Matthews, R.; Mortimer, N. Carbon and Energy Balances for a Range of Biofuels Options. Project no. B/B6/00784/REP URN 03/836. DTI Sustain. Energy Programs, UK 2003, 341. [Google Scholar]

- Grahem, E.; Fulghum, N.; Altieri, K. Global Electricity Review 2025; IEA: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorese, E.; Bonollo, F.; Timelli, G.; Arnberg, L.; Gariboldi, E. New Classification of Defects and Imperfections for Aluminum Alloy Castings. Int. J. Met. 2015, 9, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiryakioglu, M.; Campbell, J. Quality Index for Aluminum Alloy Castings. Int. J. Met. 2014, 8, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiryakioğlu, M. Solubility of Hydrogen in Liquid Aluminium: Reanalysis of Available Data. Int. J. Cast Met. Res. 2019, 32, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiryakioğlu, M. The Effect of Hydrogen on Pore Formation in Aluminum Alloy Castings: Myth versus Reality. Metals 2020, 10, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiryakioğlu, M. On the Heterogeneous Nucleation Pressure for Hydrogen Pores in Liquid Aluminium. Int. J. Cast Met. Res. 2020, 33, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifeddine, S.; Poletaeva, D.; Ghorbani, M.; Jarfors, A.E.W. Heat Treating of High Pressure Die Cast Components: Challenges and Possibilities; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Břuska, M.; Lichý, P.; Cagala, M.; Beňo, J. Influence of Repeated Remelting of the Alloy RR.350 on Structure and Thermo-Mechanical Properties. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 13, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista Research Department Share of Curb Weight of Medium Sized Cars Produced in Western Europe Attributable to Aluminum from 2008 to 2030. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/897794/western-europe-aluminum-as-share-of-car-curb-weight/ (accessed on 7 April 2024).

| Element | Al | Si | Fe | Mg | Ti | Alloy Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | 91.25 | 8.00 | 0.15 | 0.45 | 0.15 | (MJ/kg) | kWh |

| Primary embodied energy (MJ/kg), | 199.00 | 116.00 | 23.20 | 310.00 | 559.00 | 193.14 | 53.4 |

| Secondary embodied energy (MJ/kg), | 7.96 | 4.64 | 0.93 | 12.40 | 22.36 | 7.73 | 2.15 |

| Re-melting and heating to 750 °C, | 1.230 | 0.342 | |||||

| Type of Furnace | Fuel | Capacity/kg | (kgLost/kgAdded) | (JEffective/JTotal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crucible | Gas | 10–1500 | 0.04–0.06 | 0.07–0.19 |

| Induction | Electrical | 1–50,000 | 0.0075–0.0125 | 0.59–0.76 |

| Reverberatory | Electrical | 500–125,000 | 0.01–0.02 | 0.59–0.76 |

| Reverberatory | Gas | 500–125,000 | 0.03–0.05 | 0.30–0.45 |

| Stack melter | Gas | 1000–10,000 | 0.01–0.02 | 0.40–0.45 |

| Furnace | Material Type | Amounts of Returns | Embodied Energy Efficiency | Embodied Energy | Material Efficiency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (MJ/kg) | (kWh/kg) | |||||

| Electric reverberatory furnace | Primary | 20% | 97% | 200 | 55.6 | 99% |

| 60% | 95% | 207 | 57.5 | 98% | ||

| Secondary | 20% | 93% | 10 | 2.8 | 99% | |

| 60% | 89% | 12 | 3.3 | 98% | ||

| Gas reverberatory furnace | Primary | 20% | 92% | 211 | 58.6 | 96% |

| 60% | 85% | 230 | 63.9 | 93% | ||

| Secondary | 20% | 80% | 11 | 3.1 | 96% | |

| 60% | 68% | 15 | 4.2 | 93% | ||

| Induction furnace | Primary | 20% | 98% | 199 | 55.3 | 99% |

| 60% | 96% | 204 | 56.7 | 98% | ||

| Secondary | 20% | 94% | 10 | 2.8 | 99% | |

| 60% | 90% | 12 | 3.3 | 98% | ||

| Crucible furnace | Primary | 20% | 88% | 221 | 61.4 | 95% |

| 60% | 78% | 252 | 70.0 | 90% | ||

| Secondary | 20% | 83% | 17 | 4.7 | 95% | |

| 60% | 73% | 27 | 7.5 | 90% | ||

| Stack furnace | Primary | 20% | 97% | 201 | 55.8 | 99% |

| 60% | 94% | 209 | 58.1 | 98% | ||

| Secondary | 20% | 83% | 11 | 3.1 | 99% | |

| 60% | 73% | 14 | 3.9 | 98% | ||

| Country/Region | CO2ekg/kWh | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electricity | Oil | Natural Gas | LPG | |

| China | 0.528 | 0.260 | 0.202 | 0.230 |

| World | 0.481 | |||

| USA | 0.369 | |||

| EU(27) | 0.291 | |||

| Sweden | 0.041 | |||

| Country/Region | CO2ekg/kWh | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electric Reverberatory Furnace | Induction Furnace | Fossil Base | Gas Reverberatory Furnace | Stack Furnace | Crucible Furnace | |

| China | 0.69 | 0.69 | Oil | 0.57 | 0.58 | 1.53 |

| World | 0.63 | 0.63 | ||||

| USA | 0.49 | 0.49 | Natural gas | 0.44 | 0.45 | 1.19 |

| EU(27) | 0.38 | 0.38 | ||||

| Sweden | 0.05 | 0.05 | LPG | 0.50 | 0.51 | 1.35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jarfors, A.E.W. The Effects of Melting Methods and In-House Recycled Content on Climate Effects. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120398

Jarfors AEW. The Effects of Melting Methods and In-House Recycled Content on Climate Effects. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing. 2025; 9(12):398. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120398

Chicago/Turabian StyleJarfors, Anders E. W. 2025. "The Effects of Melting Methods and In-House Recycled Content on Climate Effects" Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 9, no. 12: 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120398

APA StyleJarfors, A. E. W. (2025). The Effects of Melting Methods and In-House Recycled Content on Climate Effects. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, 9(12), 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120398