1. Introduction

Granite finishing is a critical process in the stone transformation industry, ensuring both aesthetic value and functional durability of products used in architecture, kitchen countertops, landscaping, and urban design [

1,

2,

3]. In regions such as Quebec, Canada, granite contributes significantly to the economy and cultural heritage, being a symbol of architectural identity while also positioning the province as a major exporter in the global market [

4]. The transformation of granite involves diverse machining operations, including sawing, drilling, grinding, and polishing, where surface finish is a decisive criterion for customers [

1,

2,

3].

The surface properties of granite (roughness, gloss, and color) are mainly controlled by abrasive grit size, tool–work interaction, and cutting conditions: finer abrasives favor ductile flow and smoother, glossier surfaces, whereas coarser grits promote brittle fracture [

5,

6]. Granite mineralogy further modulates these mechanisms, with biotite promoting fracture and feldspar/quartz exhibiting more ductile behavior [

7], while spindle speed, contact pressure, and depth of cut govern the transition between brittle and ductile regimes [

8,

9,

10]. Similar trends are observed for carbonate stones, where optimized abrasive formulations significantly enhance marble roughness and gloss [

11].

At the same time, polishing is also associated with the generation of airborne fine particles: inhalable coarse particles (particle sizes 10 µm, PM10), fine particles or particle sizes below 2.5 µm (FP, also known as PM2.5) and ultrafine particles (particle sizes below 100 nm (UFP), all containing crystalline silica. These aerosols present severe occupational hazards, including silicosis, obstructive pulmonary disease, and cardiovascular impacts [

12,

13]. UFPs are of particular concern as they can penetrate alveoli and even cross into systemic circulation [

14,

15]. Despite the use of flooded wet lubrication to reduce dust, studies confirm that silica emissions persist at measurable levels [

16,

17,

18], and recent occupational and environmental investigations show that even with water injection, respirable crystalline silica from granite, marble and especially silica agglomerates remains high, while large marble–granite clusters can drive ambient PM2.5 in surrounding neighborhoods well above WHO guidelines [

19,

20].

Beyond its role in cooling and improving surface finish, lubrication has a decisive influence on the aerosol generation and dispersion. Under full-flood wet polishing conditions, Bahri et al. [

17] showed that the peak FP number concentration for particles with aerodynamic diameter < 1 µm decreases from about 1220 to approximately 198 #/cm

3—an overall reduction of roughly 85% compared with dry polishing. Across the particle-size spectrum, wet cutting maintains FP concentrations around 10 #/cm

3, dropping to only a few tens of particles per cubic centimeter in the largest FP classes (1.5–4 µm), confirming the strong effectiveness of full lubrication in suppressing FP emissions. However, this mitigation does not extend to UFP: while flood lubrication reduces the total FP concentration by about a factor of four, it does not produce a significant decrease in the total number of UFP [

17]. In parallel, minimum quantity lubrication (MQL) strategies also modulate emissions as a function of flow rate. Working on granite polishing, Songmene et al. [

21] observed that higher MQL flow rates substantially reduce UFP emissions but lead to more modest decreases for FP; similar trends were reported by Bahri et al. [

16] and Bahloul et al. [

22]. Bahri et al. [

16] further quantified that increasing the MQL flow from 20 to 60 mL/min reduces FP emissions by about 45% when using a chamfered tool and by 56% with a concave tool. Taken together, these results confirm that full-flood wet polishing remains the most effective strategy for reducing airborne particle emissions, while well-adjusted MQL provides a secondary option when full lubrication is operationally constrained.

Machining parameters play a central role in both surface quality and emissions. Songmene et al. [

21] observed that higher spindle speeds and feed rates improved surface finish but also influenced dust release during plane polishing. Sun et al. [

23] demonstrated that strain rate effects dominate crack propagation and chip size in granite, confirming the strong link between kinematics and removal mechanisms. More recent research has highlighted that spindle speed (

N) is the dominant factor in particle emissions, while feed rate (

Vf) exerts secondary effects [

6,

16,

17].

Tool geometry adds another critical dimension. While many studies focused on plane polishing [

5,

21] fewer investigated profile tools for edge finishing. Yet, the wide range of shapes (eased, beveled, concave, ogee, etc.) alters the contact stress distribution and thus the particle release mechanisms. For example, sharper geometries (Half-Beveled, Eased chamfer) concentrate stress at the contact edge, promoting UFP generation, while curved geometries (Ogee, Eased Concave) distribute stress more uniformly and mitigate emissions [

16,

17,

24]. Moreover, granite type influences particle generation due to differences in quartz content, density, and grain size. White granites rich in quartz generally yield higher FP and UFP emissions than darker anorthosites [

14,

17,

22]. With artificial stones, which are increasingly common due to cost, the health risks are even higher because of elevated crystalline silica content [

25,

26]. Manual edge finishing of such stones generates hazardous exposures comparable or greater than natural granite [

26,

27].

Despite this evidence, systematic studies on wet edge finishing with profile tools remain scarce. Most prior works emphasize surface finish or worker exposure in general, with limited integration of tool geometry, kinematics, grit size, and granite type into a single experimental framework [

16,

17].

In a previous research work [

28], we demonstrated that the geometry of concave and chamfered profiling tools has great effects in achieving quality surface finishes and in controlling the cutting forces. The particle emission and the air quality were not investigated.

The objective of this work is therefore to investigate airborne particle emissions during wet edge finishing of granite using two industrially relevant profile tools (Half-Beveled and Ogee). While surface quality is an important outcome of granite finishing and will be analyzed and discussed in detail in a subsequent paper, the main response variables in the present study are FP and UFP emissions; surface finish is only considered indirectly through the choice of industrially relevant tools and process parameters. By applying a full factorial experimental design and combining statistical modeling with response surface analysis, this study quantifies the effects of spindle speed, feed rate, tool geometry, abrasive grit size, and granite type on FP and UFP emissions. The results aim to provide industrial guidance for tool selection and process optimization to reduce exposure risks, while contributing to the sustainability of granite transformation practices.

3. Results

3.1. Statistical Models of Emissions

The statistical analysis investigated the effect of spindle speed (N) and feed rate (Vf) on fine-particle (Cn_FP) and ultrafine-particle (Cn_UFP) emissions during wet granite edge finishing. Quadratic models were first tested, including squared and interaction terms. When these effects were not significant, simplified linear models were retained to improve robustness and interpretability.

3.1.1. Quadratic Regressions

Second-order models were defined as:

Representative equations included:

Quadratic regressions provided excellent fits for Cn_UFP at G600, particularly for half-beveled tools on both granites ( > 0.98; p < 0.001). In contrast, some fine-particle models (Cn_FP at G150—HB—black) showed weaker performance ( ≈ 0.54), reflecting higher variability.

3.1.2. Linear Regressions

When quadratic or interaction terms were not significant, simplified linear models were used:

Validated forms included:

These models achieved high explanatory power (0.84; 0.96), confirming that linear dependence on N captures most variance in particle concentrations.

3.1.3. ANOVA Synthesis

Across all configurations, spindle speed

N is the dominant factor. For fine particles Cn_FP with grit G150, the contribution of

N ranges from about 75 to 90% depending on the tool and the granite, and it is statistically significant in every case (

p ≤ 0.023). For ultrafine particles Cn_UFP with grit G600,

N contributes between 80 and 92%. Statistical significance is observed for HB-Black (

p = 0.011) and HB-White (

p = 0.009), whereas it is not significant for OG-Black (

p = 0.216) and OG-White (

p = 0.135). These trends are visible in

Figure 7a,b, where

N occupies the largest share of the contributions. Feed rate

Vf remains marginal in all scenarios, with contributions between ~8 and 25% depending on the configuration and without statistical significance. No configuration shows a robust effect of

Vf on Cn_FP or Cn_UFP once the

p-values are considered.

The heatmap of

p-values (

Figure 8) illustrates these results, comparing linear and quadratic models for the concentrations of fine (Cn_FP) and ultrafine particles (Cn_UFP). White cells correspond to effects that are absent from the linear models, whereas colored cells indicate the level of statistical significance. Overall, spindle speed

N is the only factor that regularly approaches or reaches significance. It is significant for Cn_FP (G150) with HB-Black (

p = 0.023), OG-White (

p ≈ 0.000) and OG-Black (

p = 0.007), and for Cn_UFP (G600) with HB-White (

p = 0.009) and HB-Black (

p = 0.011). Conversely, for OG-G600 (black and white),

N is not significant (

p = 0.216 and 0.135). The feed rate

Vf is not significant in any configuration; at best it remains close to the threshold for the linear model of Cn_UFP with HB-G600-Black (

p = 0.051). In the quadratic models, only one case remains significant:

N for Cn_UFP with HB-G600-White (

p = 0.026). All other terms, including

N2,

Vf2 and

N ×

Vf, exhibit high

p-values (often >0.25), which does not justify retaining them in simplified models.

Table 2 summarizes the dominant factors and retained model type per configuration, with quadratic models first tested and linear models only retained when higher-order terms were not significant. Full ANOVA tables are provided in

Appendix A.

Overall, spindle speed (N) was confirmed as the key parameter driving particle emissions, explaining between 75% and 92% of the variance depending on configuration. Feed rate (Vf) played only a secondary role and did not reach statistical significance, except for the anomalous OG—black—G600 case, which is likely linked to local material heterogeneity and transient tool–material interactions. Ultrafine particles (Cn_UFP at G600) were predicted with very high accuracy, particularly with half-beveled tools on both granites ( > 0.98), while fine-particle models (Cn_FP at G150) displayed greater variability, especially when machining black granite with HB tools.

3.2. Influence of Tool Geometry

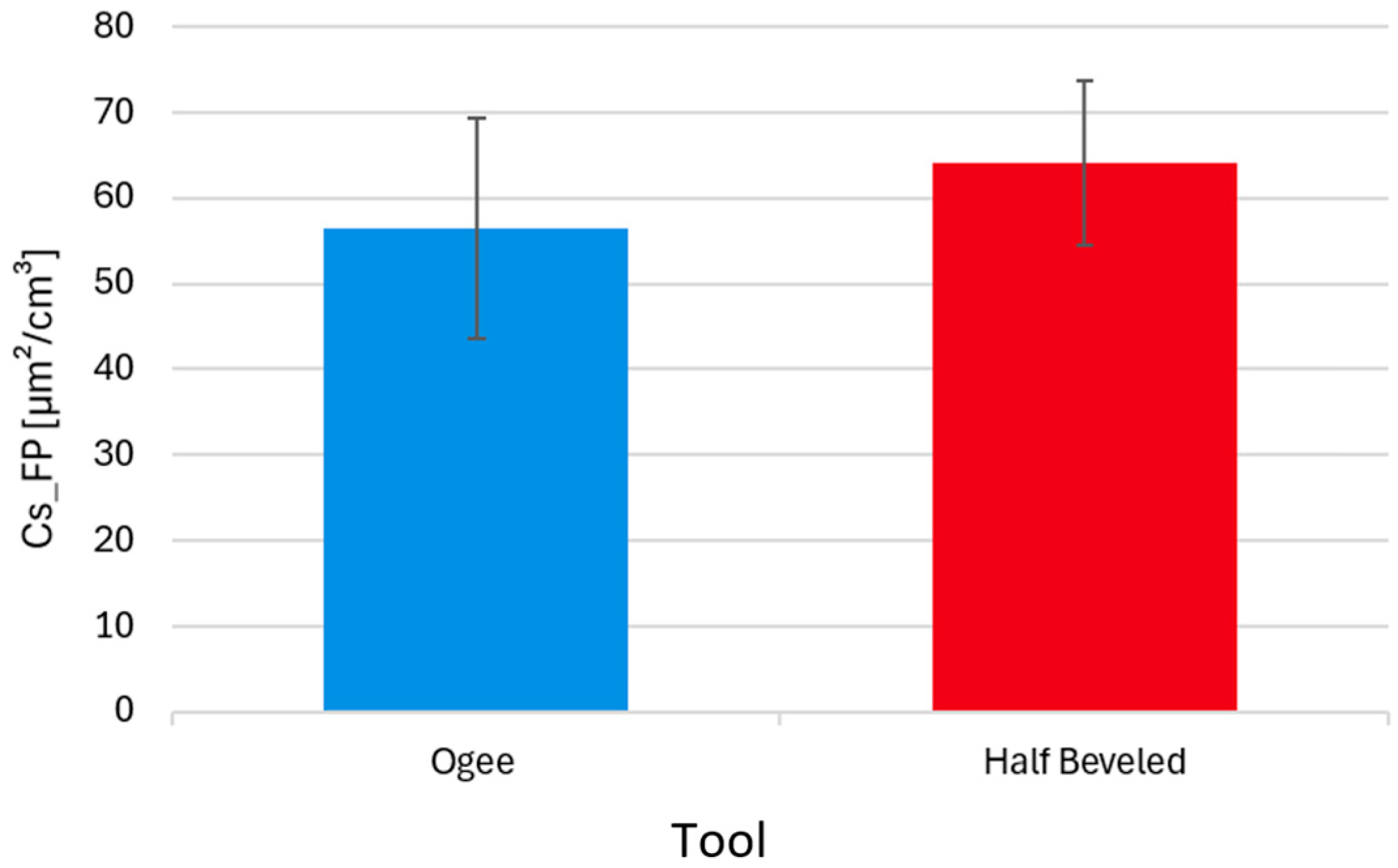

To isolate the influence of tool geometry on particle emissions, a standardized configuration was adopted: white granite, G150 grit for fine particles (FP), G600 grit for ultrafine particles (UFP), spindle speed N = 2500 rpm, and feed rate Vf = 1000 mm/min. White granite was selected for its homogeneity and high quartz content, which improve the stability and reproducibility of measurements. Among the four tested geometries, only the Half-Beveled (HB) and Ogee (OG) tools were retained for comparison, as they exhibit more pronounced features: a sharp, angular geometry with a larger bevel on the HB tool versus a curved, continuous geometry with a deeper profile on the OG tool. This contrast allowed clearer isolation of geometric effects on particle release. Fine particle emissions were quantified using the specific surface concentration (Cs_FP), which provides a more sensitive health-relevant indicator than mass or number concentration alone, as it reflects both particle size distribution and surface area. The use of intermediate cutting conditions avoided extreme behaviors, ensuring realistic and comparable polishing scenarios.

3.2.1. Influence on Fine Particles (FP)

The impact of tool geometry on fine particles (FP) was assessed through the specific surface concentration (Cs_FP) at grit G150.

Figure 9 shows the mean Cs_FP values for the OG and HB tools. A slightly higher average concentration was observed with the HB tool compared to OG, consistent with its sharper bevel inducing more localized fragmentation. However, the error bars representing 95% confidence intervals clearly overlap, indicating that the difference is not statistically significant.

ANOVA confirmed this observation (

Table 3). The

p-value (

p = 0.708) indicates that tool geometry did not exert a statistically significant effect on Cs_FP under the tested conditions. The high variability within both tool groups masked any clear differences. These findings suggest that for FP, the effect of tool geometry is weak compared to other factors such as spindle speed (

N), and that variability dominates the response.

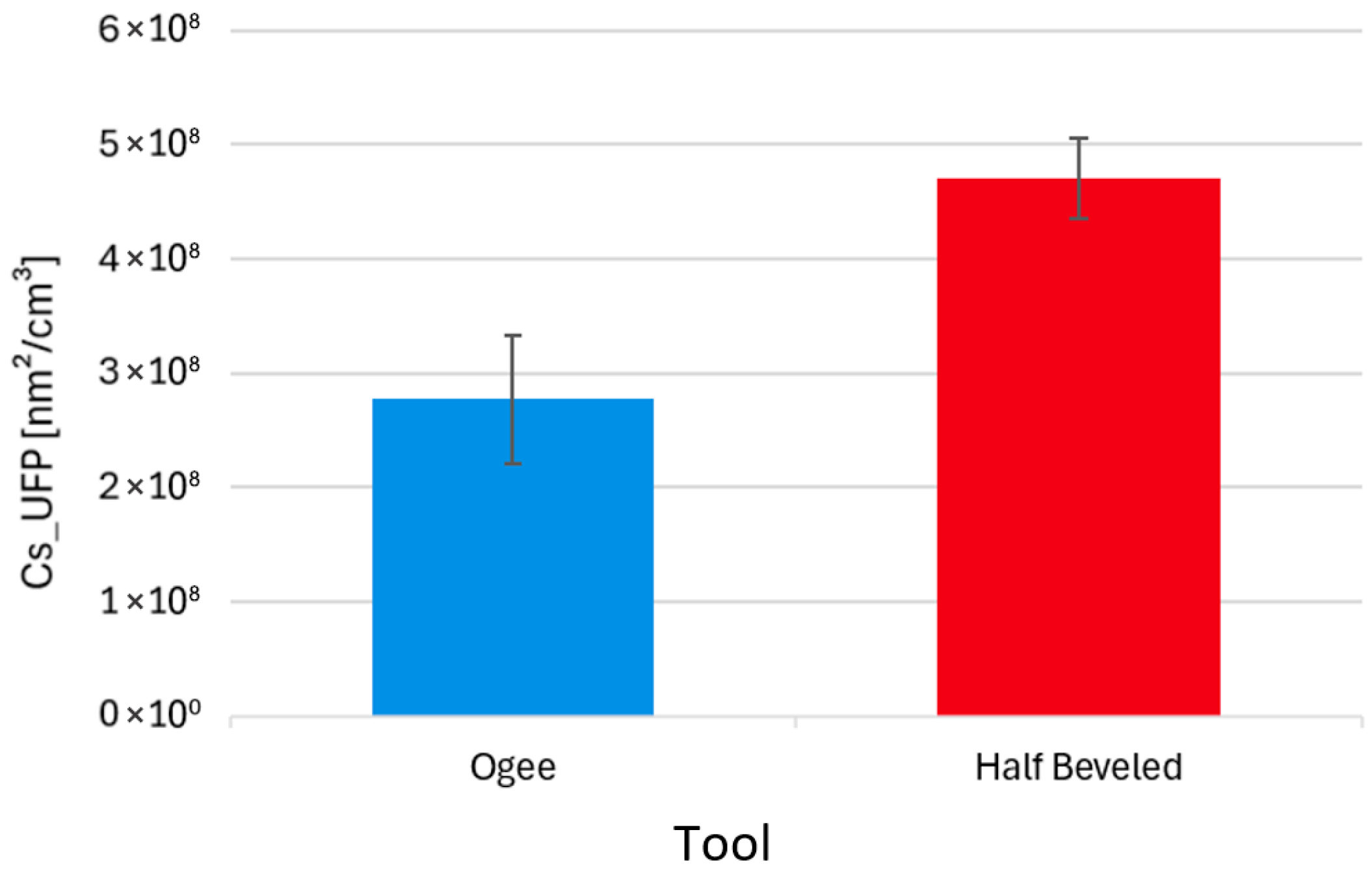

3.2.2. Influence on Ultrafine Particles (UFP)

In contrast, tool geometry exerted a much stronger effect on ultrafine particle (UFP) emissions.

Figure 10 shows the specific surface concentration (Cs_UFP) for the OG and HB tools at grit G600. The HB tool generated substantially higher concentrations than OG, with non-overlapping confidence intervals, highlighting a significant effect.

The ANOVA results (

Table 4) confirmed the graphical evidence, with a highly significant tool effect (

p < 0.001). The HB tool consistently produced higher Cs_UFP values than the OG tool.

This result demonstrates that the sharper bevel geometry of the HB tool promotes higher UFP generation compared to the smoother, continuous OG profile. The explanation lies in the different fragmentation mechanisms: the HB tool induces more localized stress concentrations at the edge–granite contact, enhancing micro-fracturing of mineral grains and releasing larger amounts of ultrafine particles. In contrast, the curved OG geometry distributes stresses more gradually, reducing the intensity of particle detachment.

Overall, these findings highlight that tool geometry plays a minor role in FP emissions but a decisive role in UFP generation, with sharper geometries (HB) being substantially more hazardous in terms of ultrafine particle release.

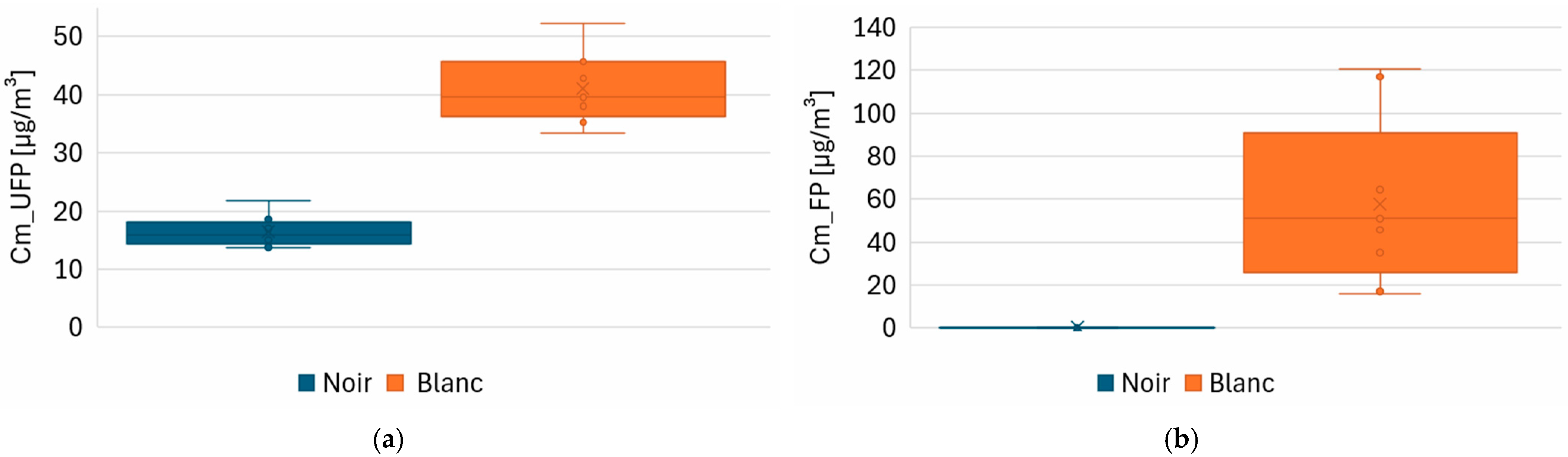

3.3. Influence of Granite Type

To evaluate the effect of granite type (black vs. white) on particle mass concentrations, statistical analyses were performed on nine experimental conditions with varying spindle speeds (N) and feed rates (Vf). The abrasive grit sizes were fixed to G150 for fine particles (FP) and G600 for ultrafine particles (UFP).

Normality tests (Anderson–Darling) were first conducted on the subgroups (black and white granite, separately for Cm_FP and Cm_UFP). The results are summarized in

Table 5. Both Cm_UFP datasets followed normal distributions (

p > 0.10), as did Cm_FP for white granite. However, Cm_FP values for black granite deviated significantly from normality (

p < 0.01).

Based on these results, Student’s t-tests were applied for Cm_UFP (both granites) and for Cm_FP in white granite. For Cm_FP in black granite, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney test was used due to non-normality.

For ultrafine particles, the two-sample t-test revealed a highly significant difference between granite types (p < 0.001). White granite exhibited a mean Cm_UFP of 40.98 μg/m3, more than twice the value of black granite (16.53 μg/m3). The 95% confidence interval of the difference [−29.34; −19.56 μg/m3] excluded zero, confirming the robustness of this result.

For fine particles, white granite also generated significantly higher emissions (57.8 μg /m3) compared to black granite (0.25 μg/m3). The Mann–Whitney test confirmed this difference (p < 0.001), with a 95% confidence interval of the median difference [−115.4; −17 μg/m3].

Figure 11 illustrates these results with boxplots comparing Cm_FP and Cm_UFP across granite types. In both cases, white granite shows clearly higher medians and wider spreads, confirming its greater mass emission potential.

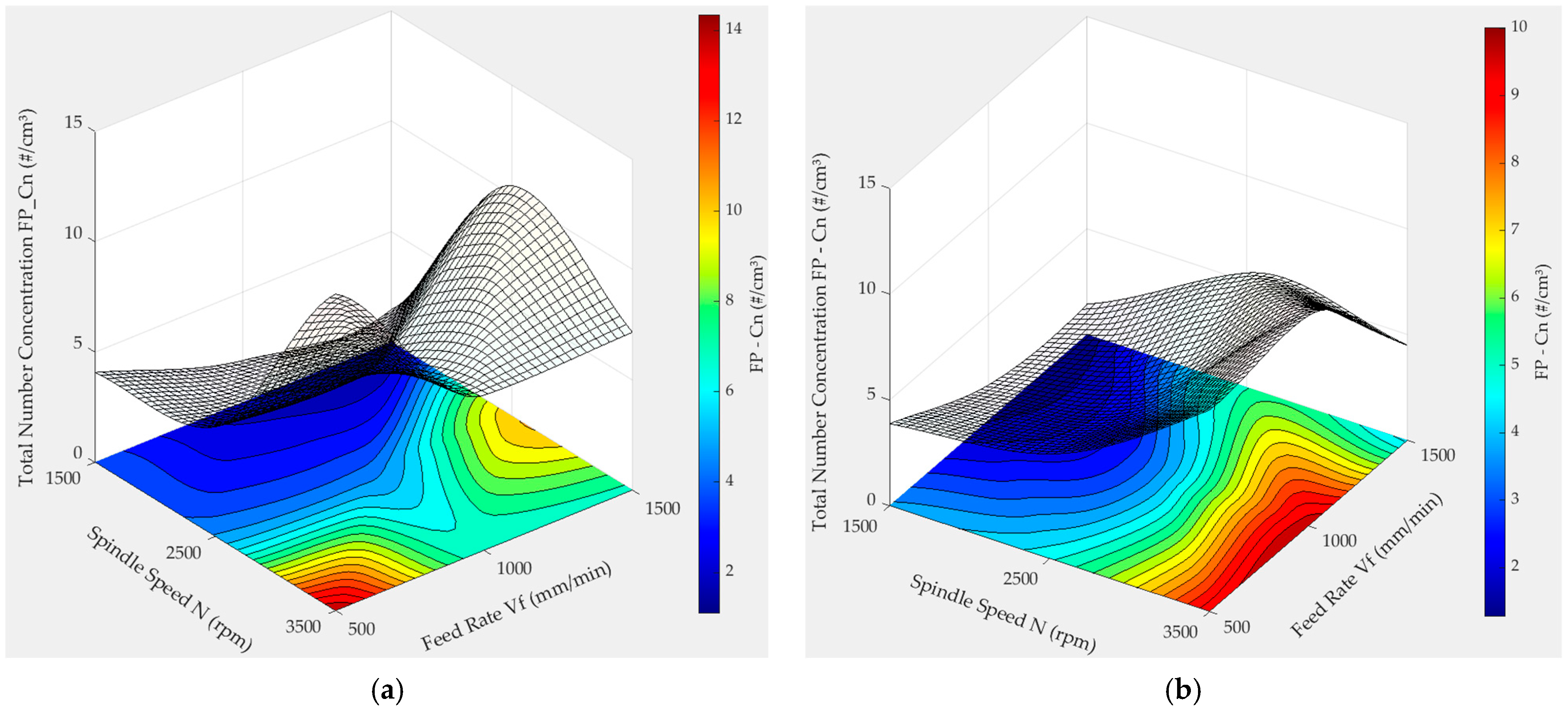

3.4. Response Surfaces

3.4.1. Fine Particle Emissions (Cn_FP)

The response surfaces for fine particles (Cn_FP) highlight the predominant role of spindle speed (

N), with feed rate (

Vf) exerting a secondary and often less consistent influence. Tool geometry further modulates these effects. On black granite (

Figure 12a,b), Half-Beveled tools produce very low and stable emissions, ranging between 0.01 and 0.18 #/cm

3, even at high spindle speeds. By contrast, Ogee tools lead to higher emissions, peaking at approximately 4.3 #/cm

3 under the most aggressive conditions (

N = 3500 rpm,

Vf = 500 mm/min).

On white granite (

Figure 13a,b), interaction effects between

N and

Vf become more pronounced. The Half-Beveled tool reaches a maximum of ~14.0 #/cm

3 at

N = 3500 rpm and

Vf = 500 mm/min, indicating a steep rise in particle release under elevated cutting rates. Ogee tools display a lower maximum (~9.9 #/cm

3 at

N = 3500 rpm and

Vf = 1000 mm/min) but with greater surface instability, suggesting sensitivity to local heterogeneities of the granite. These findings confirm that Ogee tools tend to generate higher FP emissions overall, due to their sharper geometry promoting micro-fracturing, whereas Half-Beveled tools induce smoother cutting with more controlled particle detachment.

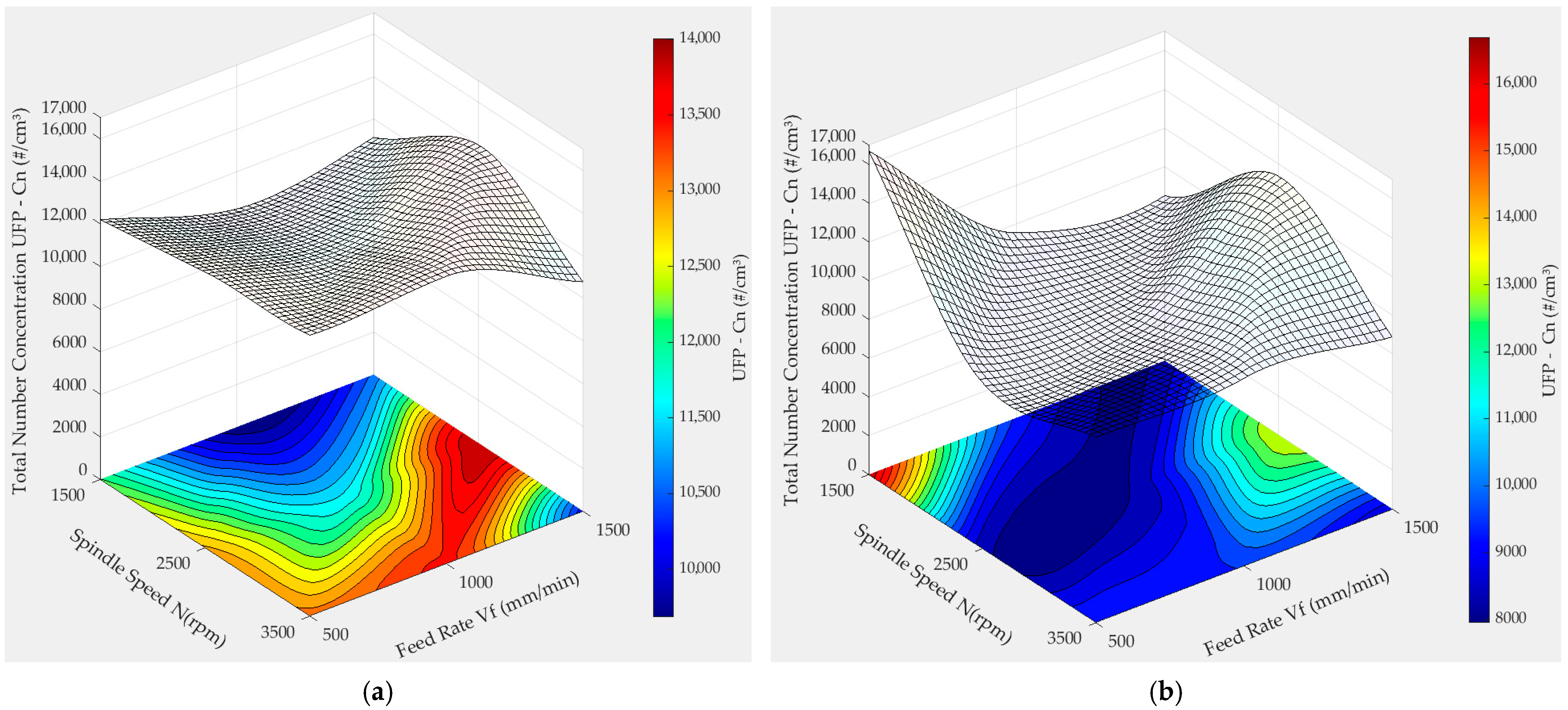

3.4.2. Ultrafine Particle Emissions (Cn_UFP)

Ultrafine particle concentrations are substantially higher than those of FP, reaching levels up to 16,500 #/cm

3 depending on cutting parameters. Spindle speed (

N) emerges as the dominant factor, although interactions with feed rate (

Vf) significantly shape the emission landscape, particularly on white granite. For black granite (

Figure 14a,b), Ogee tools yield the highest emissions (~11,000 #/cm

3 at

N = 1500 rpm,

Vf = 1000 mm/min), while Half-Beveled tools show more moderate values (~6400 #/cm

3), with little sensitivity to

Vf.

On white granite (

Figure 15a,b), Ogee tools produce the most variable response surfaces, with a maximum of ~16,500 #/cm

3 at low spindle speed (1500 rpm) and low feed rate (500 mm/min). This suggests accelerated wear and fracture under these conditions, amplified by the granite’s abrasive quartz structure. Half-Beveled tools again demonstrate more controlled emissions, gradually increasing with

Vf and peaking at ~13,500 #/cm

3, reflecting a more predictable particle release mechanism.

4. Discussion

The statistical analyses confirm spindle speed (

N) as the main driver of particle emissions (Cn_FP and Cn_UFP), while feed rate (

Vf) plays a secondary role. The variance-decomposition pie charts show that

N systematically accounts for most of the explained variance, with

Vf contributing a smaller share, and the

p-value heatmap indicates that

N is the only factor that reaches or approaches significance in several FP and UFP models, whereas

Vf is never statistically significant and higher-order terms (

N2,

Vf2,

N ×

Vf) can be neglected. The few configurations where

N is not significant (e.g., OG with G600) correspond to nearly flat response surfaces under flooded lubrication, where emissions are low and only weakly sensitive to the tested kinematics. Overall, these results support the view that controlling

N is the most effective lever for reducing airborne particles during wet edge finishing, in line with previous observations that kinematic parameters dominate dust generation in stone machining [

6,

21].

The predominance of spindle speed in particle emissions also aligns with results in granite plane polishing reported by [

21], confirming that higher

N increases localized stress and promotes micro-fracturing of mineral grains [

16,

17].

Table 6 synthesizes the main emission trends by configuration, integrating the effects of tool geometry, granite type, and grit size. It shows that the Half-Beveled (HB) tool, particularly with G600 grit on black granite, minimized ultrafine particle emissions (~6400 #/cm

3) with remarkable stability. Conversely, the Ogee (OG) tool on white granite produced the highest UFP concentrations (≥14,000 #/cm

3) and unstable patterns, reflecting strong

N ×

Vf interactions. For fine particles, the lowest levels were observed for HB—G150—black granite (<0.2 #/cm

3), while OG—G150—white granite reached ~9.5 #/cm

3, confirming the significant influence of tool shape.

Cross-analysis of

Table 6 indicates that HB tools provide better emission control, while OG tools tend to amplify particle release due to sharper local stress fields at the granite-tool contact. Half-Beveled tools, while efficient for surface smoothness, tend to emit more UFP due to their sharp bevel edges and concentrated contact zones. Conversely, tools with curved geometries such as the Eased Concave reduce emissions thanks to more distributed stress as shown in earlier work [

28].

The contrast between black and white granite emissions can be interpreted considering their mineralogy and fracture mechanisms. The white granite used here contains about 41% quartz, whereas the black granite is largely composed of plagioclase (~83%) [

21]; since quartz is harder (7 on the Mohs scale) than plagioclase (6–6.5), the white granite tends to fail in a more brittle mode under abrasive contact [

21]. This promotes intergranular micro-cracking and the detachment of numerous small, silica-rich fragments, so that the harder, more SiO

2-rich white granite naturally generates more fine and ultrafine particles than the softer black granite. Consistently,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 show that white granite exhibits higher FP and UFP mass and number concentrations, with steeper response-surface gradients versus

N and

Vf, whereas

Figure 11b and the response surface in

Figure 12a display FP levels close to zero for black granite. These very low FP values indicate that, under edge finishing of black granite with flooded wet lubrication, most fine particles are either not generated (less brittle fracture in the plagioclase-rich matrix) or are efficiently captured by the continuous water film, which promotes agglomeration and settling of debris and reduces airborne FP concentrations down to the APS background. This behavior is consistent with the results of Songmene et al. [

21], who reported that white granite produced more fine particles in dry polishing and more aerosols in MQL than black granite and that most particles were below 2.5 µm. By contrast, Bahri et al. [

16] found higher FP and UFP emissions for black granite during dry edge finishing, despite its lower silica content, suggesting that tool geometry, lubrication regime (dry, MQL, and flooded water), grit size, and differences in microstructure or texture between granites can invert the ranking.

To further explore these patterns, a particle size distribution (PSD) analysis was conducted under optimized (blue curves) and emission-maximizing (red curves) conditions.

For fine particles (FP),

Figure 16 shows a marked peak around 3–4 µm at high spindle speed and low feed rate (

N = 3500 rpm,

Vf = 500 mm/min). These PM2.5 particles are critical because they can penetrate deep into the bronchioles and, in some cases, the alveolar region [

33]. Increasing feed rate (

N = 1500 rpm,

Vf = 1500 mm/min) reduced concentrations and yielded a flatter, more homogeneous distribution, highlighting the importance of adjusting

N and

Vf coupling to minimize respirable particle release.

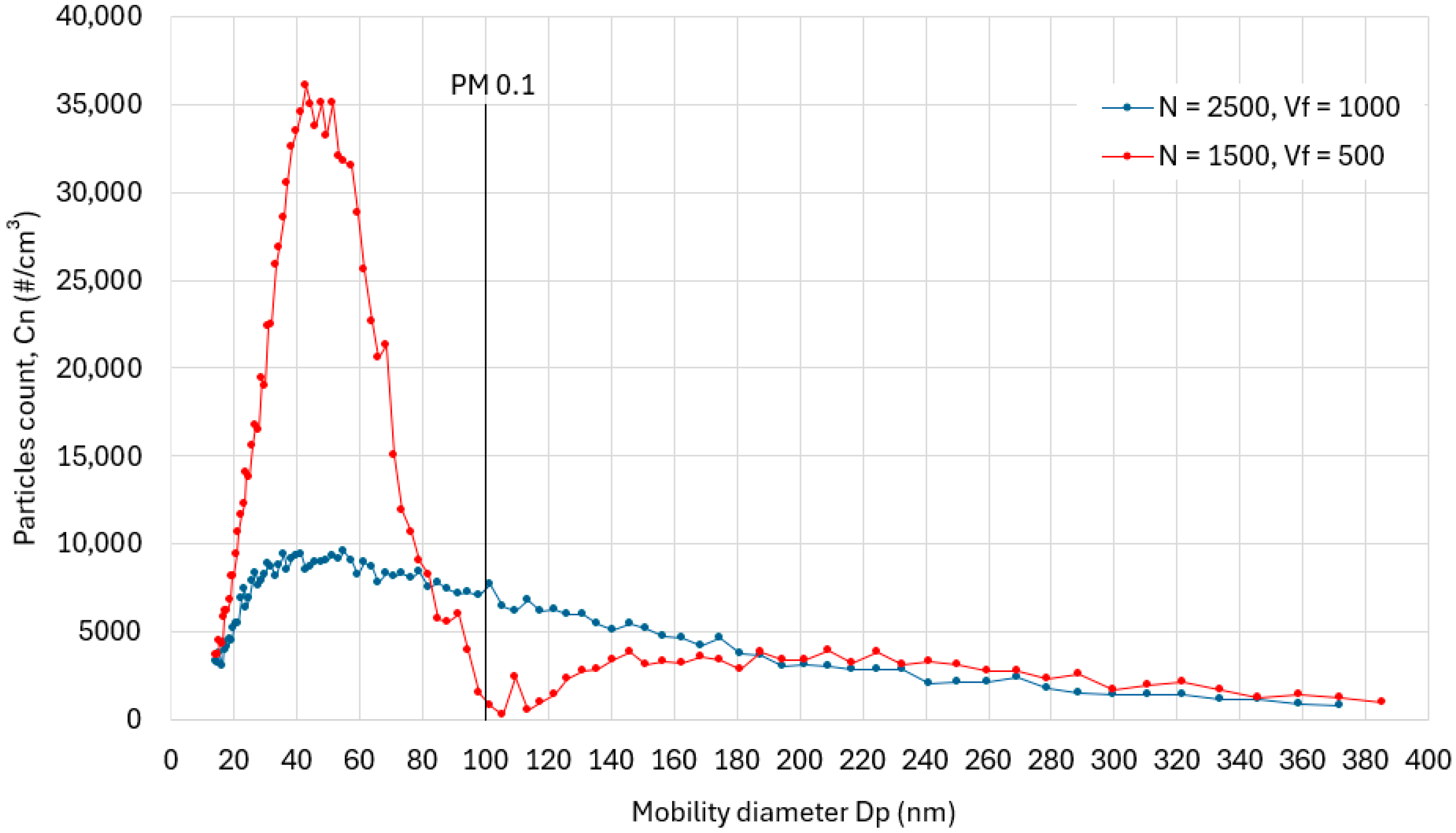

For ultrafine particles (UFP),

Figure 17 (OG—G600—white granite) reveals a dominant peak near 50 nm (PM0.1) under low

Vf and reduced spindle speed, with concentrations exceeding 3.5 × 10

4 #/cm

3. Such particles (< 100 nm) are of particular concern since they penetrate deeply into alveoli, cross biological barriers, and can reach the cardiovascular system [

13,

14]. Optimized conditions (

N = 2500 rpm,

Vf = 1000 mm/min) significantly flattened the distribution, reducing maximum concentrations below 1.0 × 10

4 #/cm

3. This demonstrates that tuning cutting kinematics can effectively mitigate UFP emissions.

Figure 18 shows that effective lubrication and a more favorable machining parameter setting (

N = 2500 rpm,

Vf = 1000 mm/min) clearly lower Cm_UFP compared with the unfavorable case (

N = 1500 rpm,

Vf = 500 mm/min), especially below PM0.1. However, the mass increases with particle diameter and, beyond approximately 220–240 nm, the red curve frequently exceeds the VEMP of 0.05 mg/m

3 (reaching about 0.10–0.12 mg/m

3), while the blue curve reaches or nearly reaches it around 260–320 nm. These measurements correspond to a machining time on the order of 5 min, whereas the VEMP is defined as an 8 h time-weighted average exposure limit. It is therefore not sufficient to optimize

N and

Vf or to switch to wet lubrication alone: sustained compliance with the VEMP requires additional control measures both at the source and in the work environment.

Figure 19 compares the emissions of UFP as a function of grit sizes. At the beginning of edge polishing with the coarse shaping grit G45, both tools generate the highest UFP levels, with Cn_UFP for the Half-Beveled tool almost twice that obtained with finer grits. As the edge profile is progressively matched and the surface becomes smoother with G150–G600, emissions drop sharply (minimum around G150) and then stabilize at intermediate values, reflecting the transition from aggressive stock removal to more stable polishing. This trend is consistent with the strong fluctuations of cutting forces observed at G45, when the high material removal rate and poor initial conformity between tool and edge promote intense micro-fracturing and particle release.