Research on Dynamic Center-of-Mass Reconfiguration for Enhancement of UAV Performances Based on Simulations and Experiment

Highlights

- The center-of-mass (CoM) shifting mechanism can generate stabilizing gravitational torques, effectively reducing angular deviations during propulsion failure, enabling reliable self-righting in a near-horizontal manner, as well as enhancing its aerial maneuverability and braking performance and reducing power consumption.

- Simulation and experimental results confirm that the CoM system provides a fail-safe stabilization feature, which is independent of rotor thrust, and ensures structural protection and operational continuity during emergencies.

- Integrating a dynamic CoM shifting mechanism is a critical design strategy for next-generation UAVs, providing stability even under motor-out or free-fall condi-tions, and substantially improving safety, efficiency, and mission survivability.

- This research establishes a validated framework for gravitational stabilization, demonstrating how active mass reconfiguration can be applied to UAVs to enhance stability, agility, and energy efficiency.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Literature Review

1.3. Innovation, Contributions, and Technical Challenges

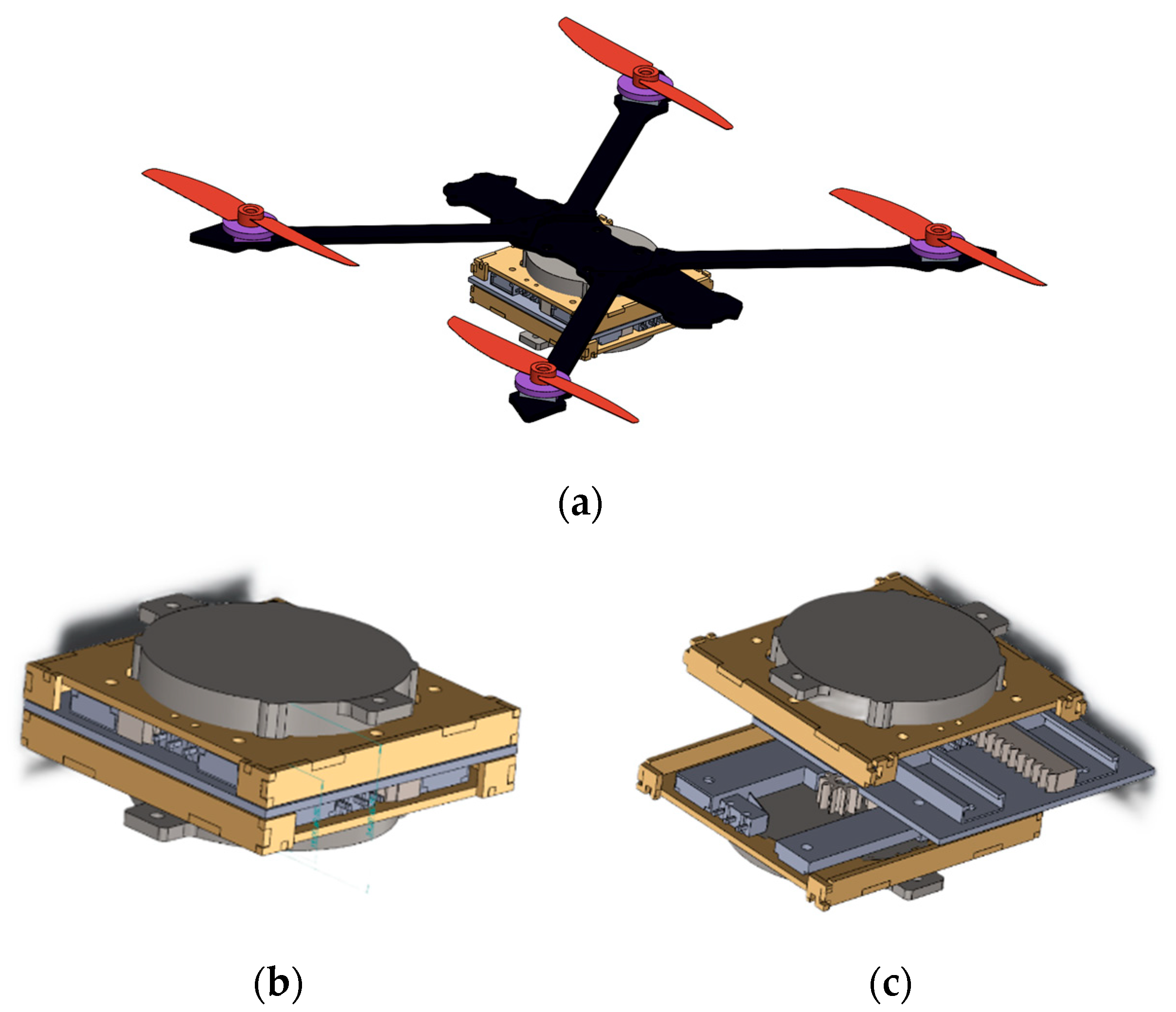

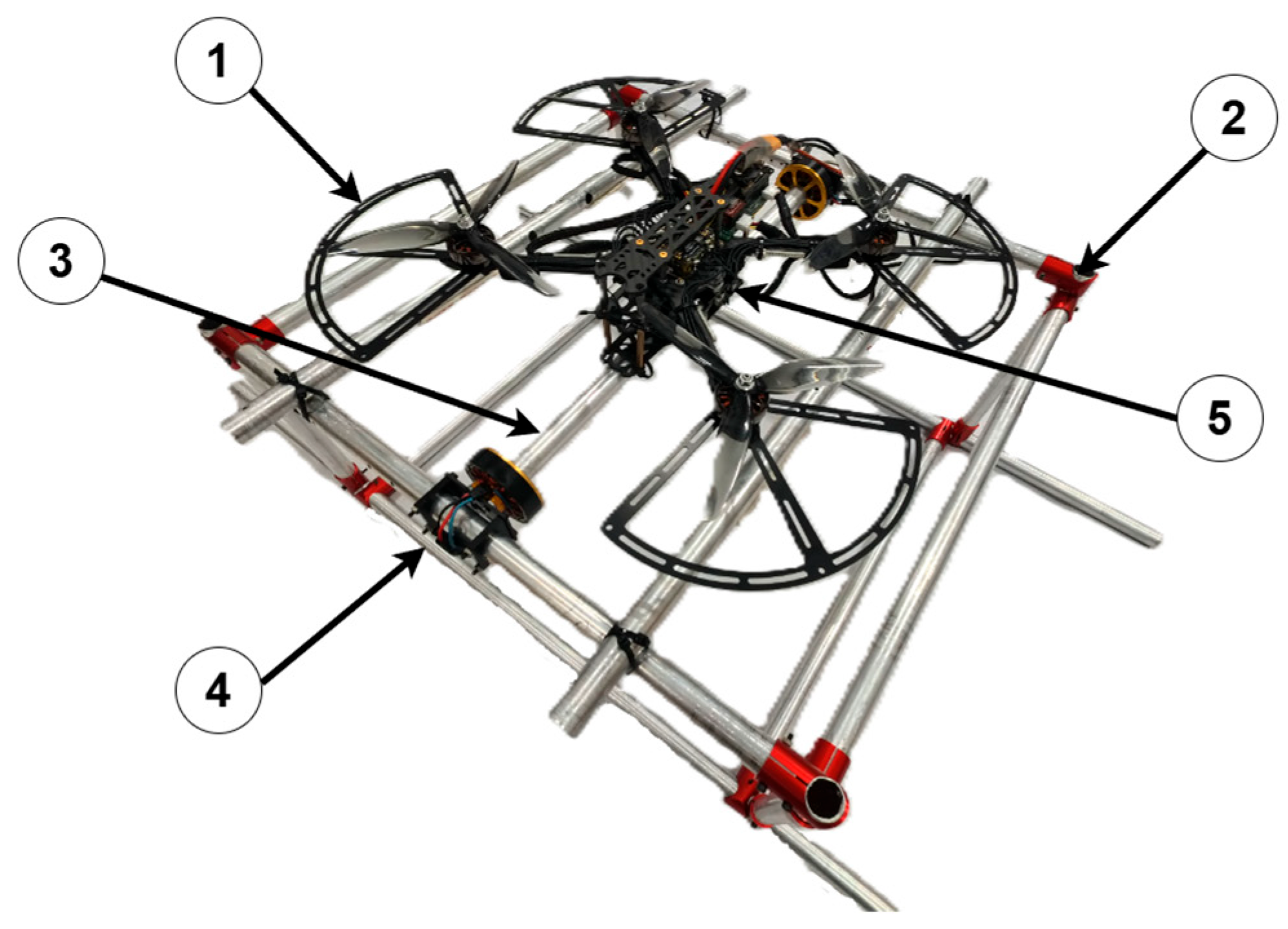

2. Overall Aerial Vehicle System Design and Detailed Hardware Integration

2.1. Airframe and CoM Shifting Device

2.2. Actuation and Motor Sizing

2.3. Homing and Calibration

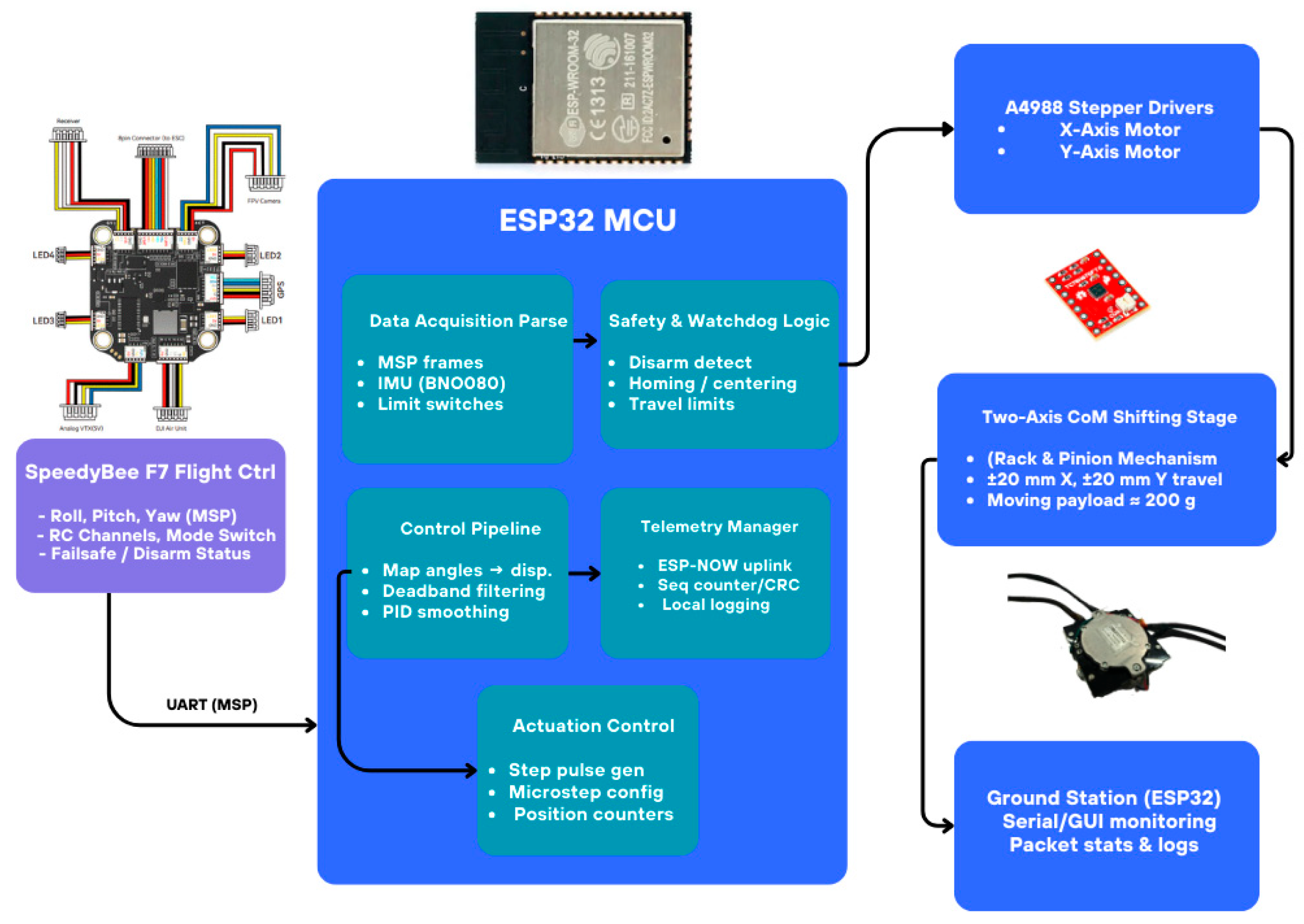

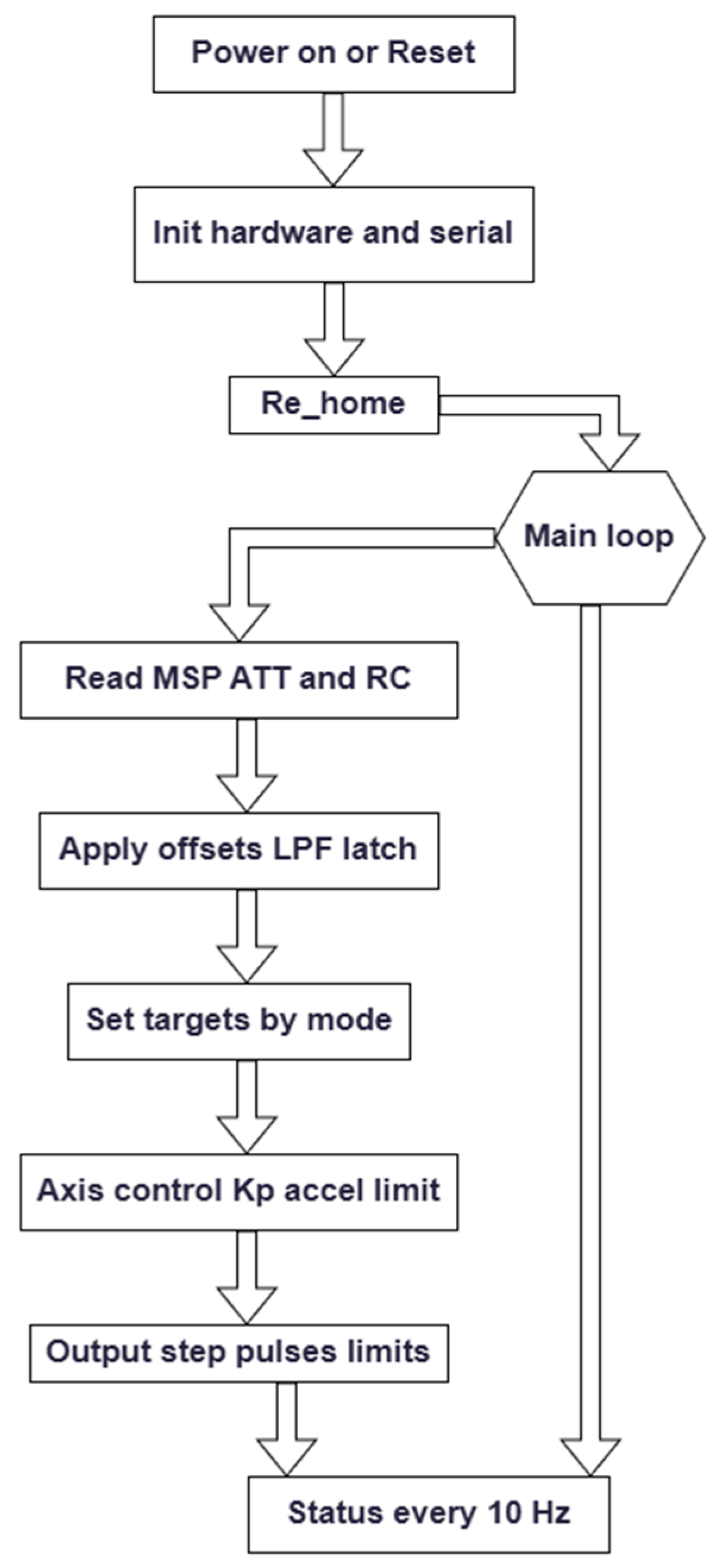

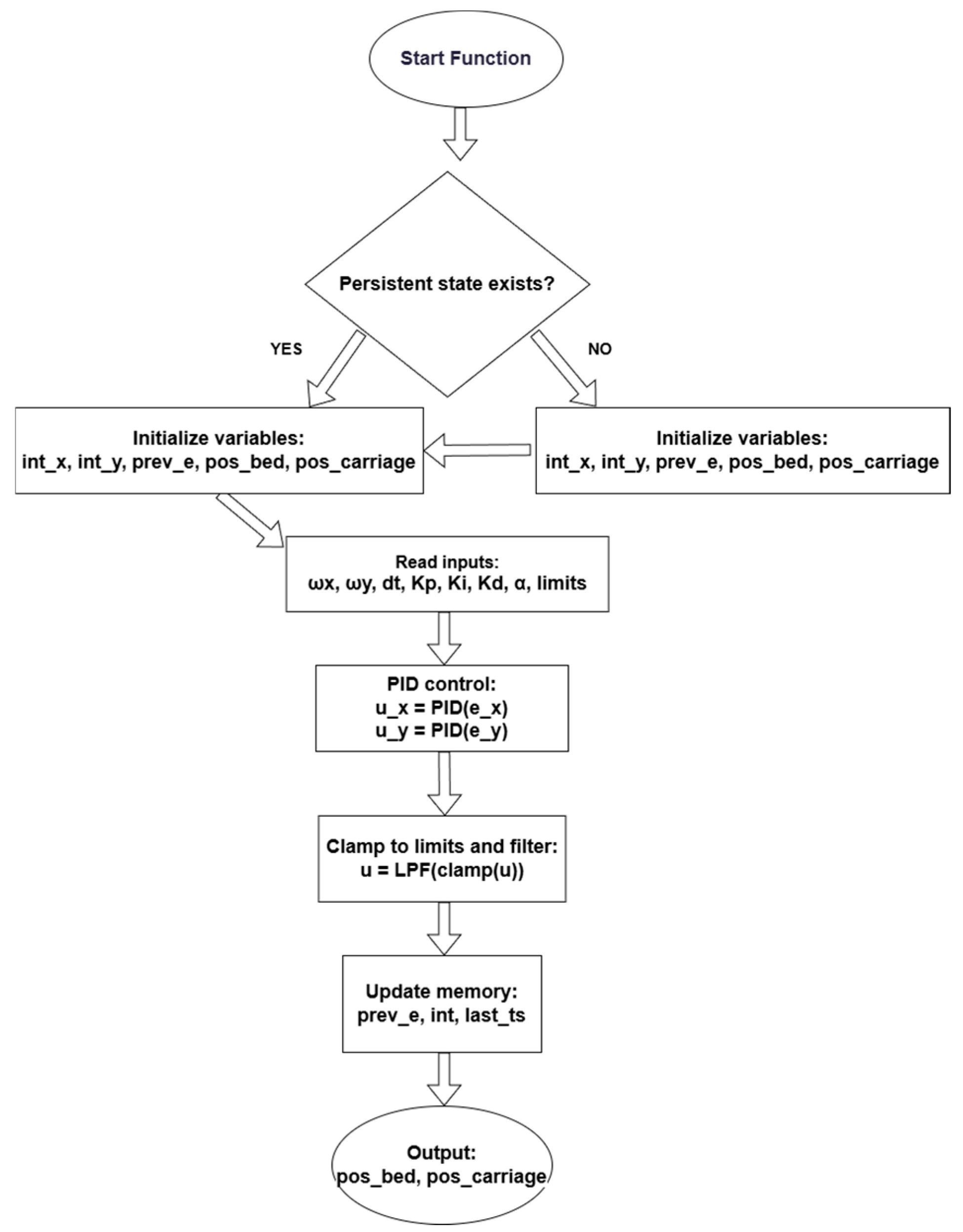

2.4. Control Flow and System Architecture

2.5. Controller Parameter Selection and Tuning Methodology

2.6. Detailed Procedure for CoM Reconfiguration

2.6.1. Attitude Sensing

2.6.2. Error Computation and Filtering

2.6.3. Mapping Orientation Error to CoM Displacement

2.6.4. Motion Execution via Prismatic XY Stage

3. Analytical Modeling of the UAV and Integrated CoM Device

3.1. Concept of CoM

3.2. Rigid-Body Modeling with Moving Mass

3.3. Translational and Rotational Dynamics

3.4. Gravity-Induced Moments

3.5. Allocation Model

3.6. Lagrangian Derivation

3.7. Linearization Around Hover

3.8. Electromechanical Stage Modeling

3.9. State Space Formulation

3.10. Energy and Optimal Allocation

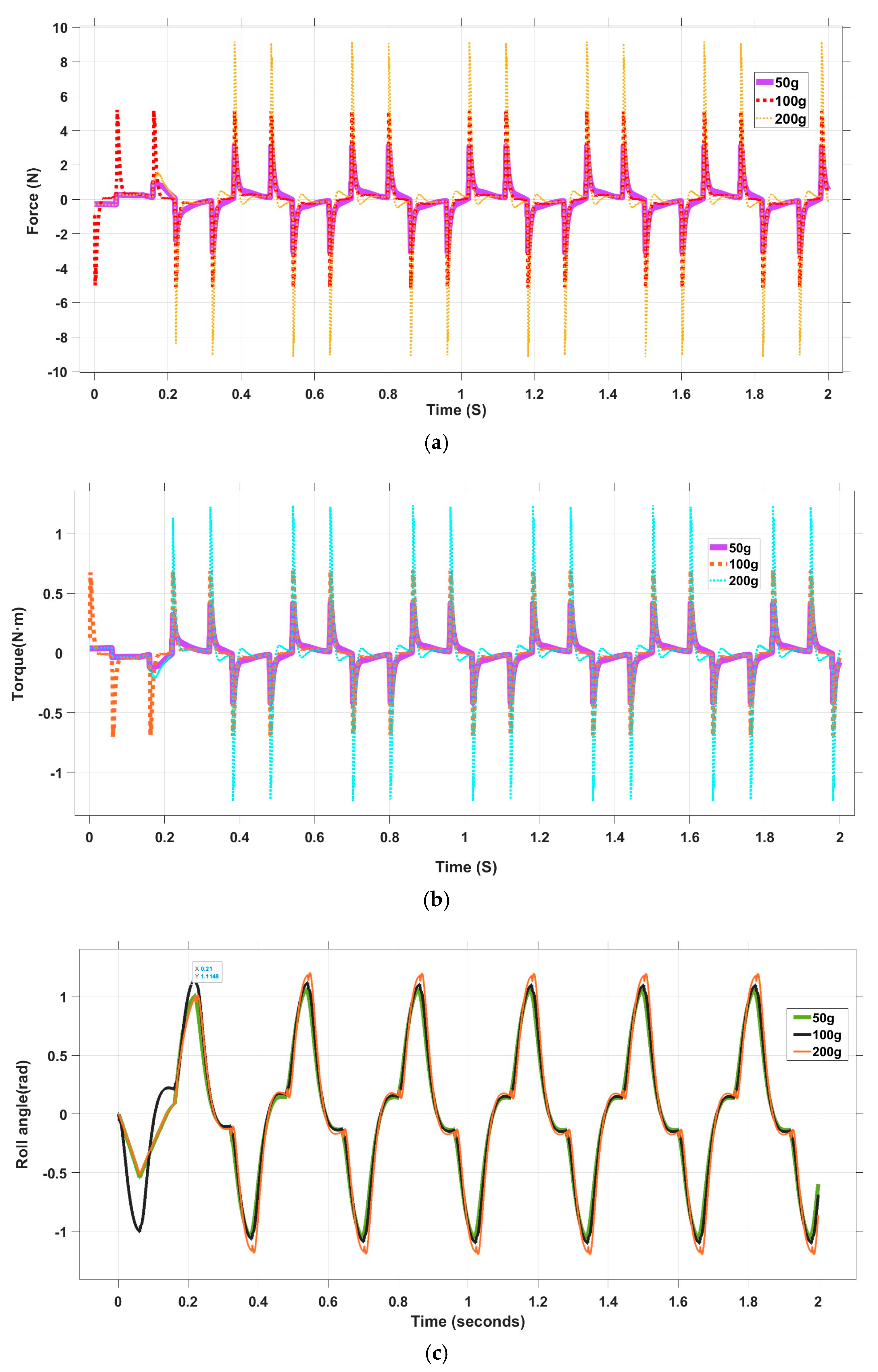

4. Simulation of Roll Stabilization of UAV Based on MATLAB

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.2. Simulation Parameters and Evaluation Metrics

4.3. Results and Battery Efficiency Analysis

4.3.1. CoM Shifting System Performance

4.3.2. Battery Efficiency Analysis with Detailed UAV Parameters

- 1.

- Energy Consumption for Propulsion-Based Stabilization (Eₚ)

- 2.

- Energy Consumption for CoM Device (Ek)

- Energy Calculations for CoM Device

4.3.3. Comparative Energy Consumption: CoM Device vs Thrust-Based Stabilization

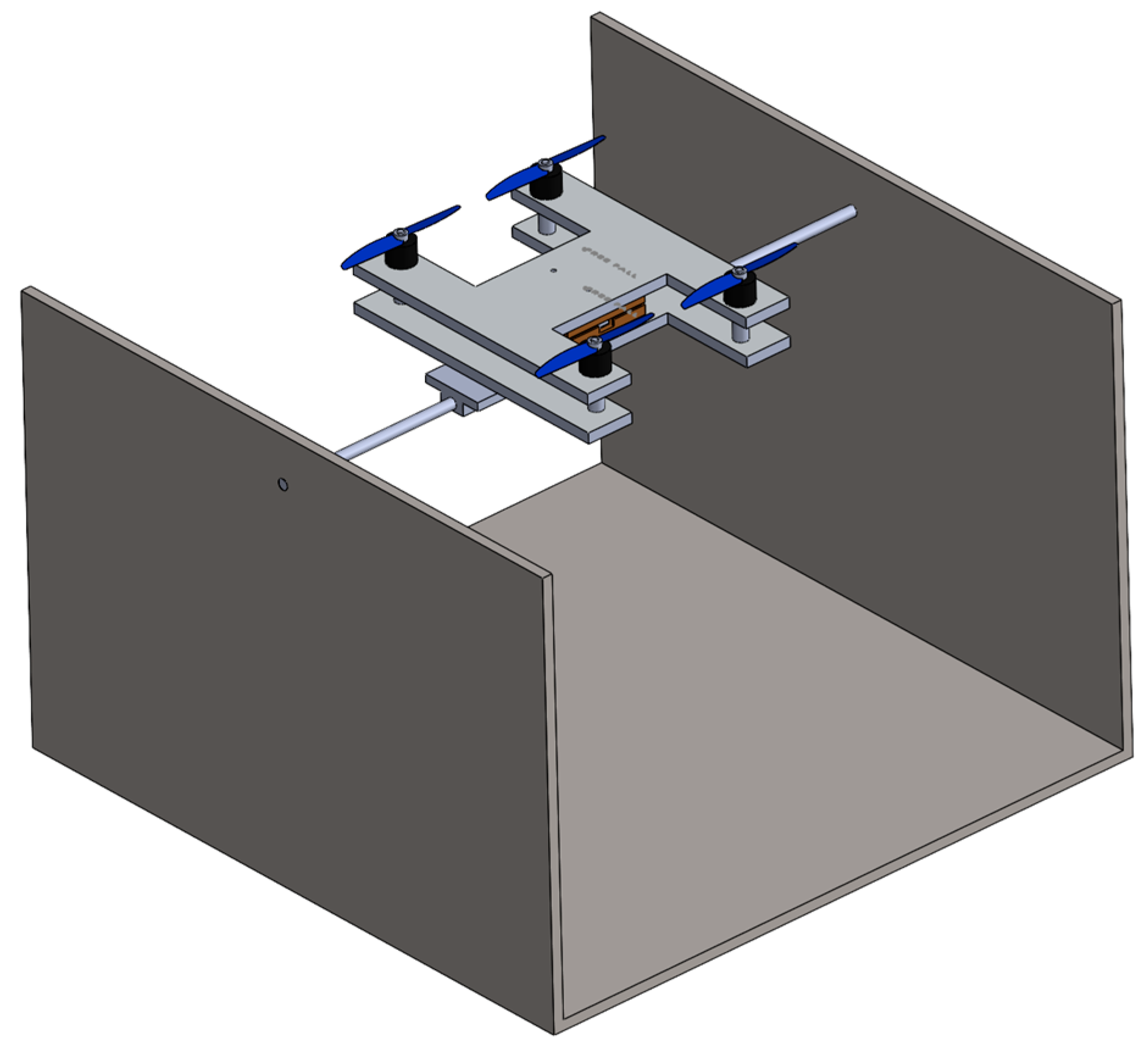

5. Indoor Experimental Evaluation of the UAV Prototype

5.1. Experimental Setup

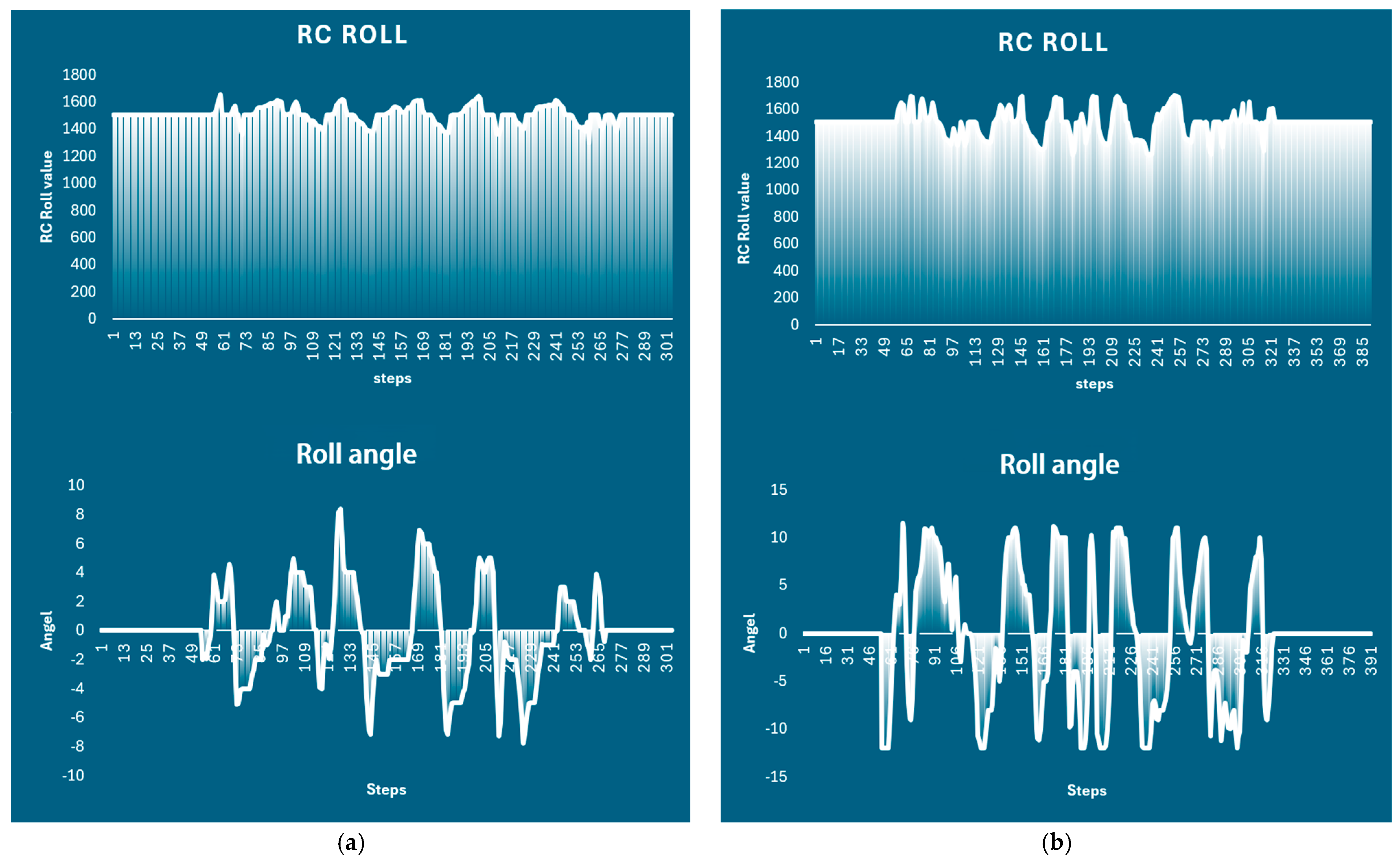

5.2. Baseline Condition (Device Disabled)

5.3. Condition with CoM Device Activated

5.4. Experimental Results and Observations

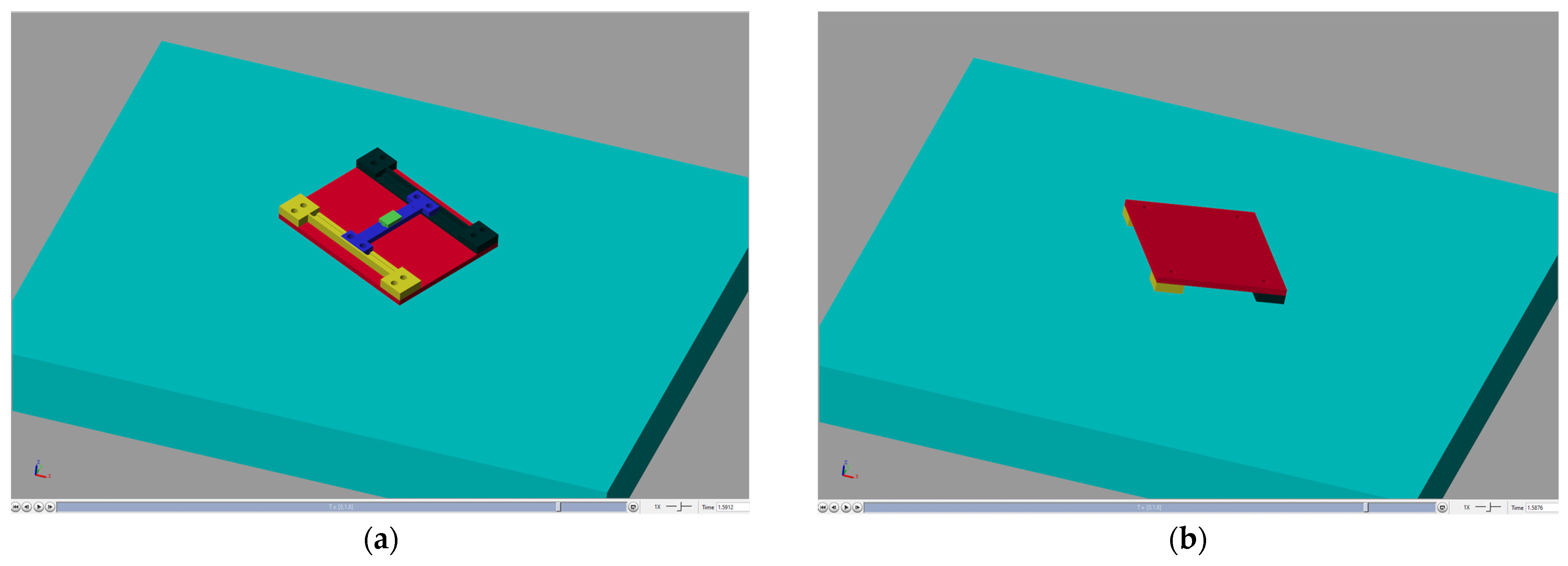

6. Dynamic Free-Fall Simulation of UAV Stabilization Using Center-of-Mass Adjustment

6.1. Simulation Architecture

6.2. Test Scenarios

6.3. Control Algorithm

6.4. Simulation Framework and Comparison

6.5. Results: Free-Fall Stabilization Performance

- Case 1—Without CoM Device

- Case 2—With CoM Device

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Roll, pitch, yaw (Euler angles) | |

| Angular rates | |

| Body angular velocity components | |

| Position and velocity of UAV body origin | |

| Total mass of UAV (incl. CoM device) | |

| Principal moments of inertia | |

| Slider (payload) position in body frame | |

| In-plane displacements | |

| Slider velocities | |

| Shifting payload mass (battery) | |

| Rotor-generated body torques | |

| Gravity torque from CoM shift | |

| In-plane actuator forces at carriage | |

| Motor angle and angular speed | |

| Motor rotor inertia and viscous loss | |

| Inductance and resistance | |

| Torque constant, back-EMF constant | |

| Motor electromagnetic torque | |

| Load torque at motor shaft | |

| Current-limit relation (A4988 driver) | |

| Individual rotor thrusts | |

| Rotor propulsive coefficient | |

| Kinetic and potential energy | |

| Total mechanical energy | |

| State-space matrices (linearized model) | |

| Stage friction coefficients |

Appendix A. Enlarged Simulation Figures

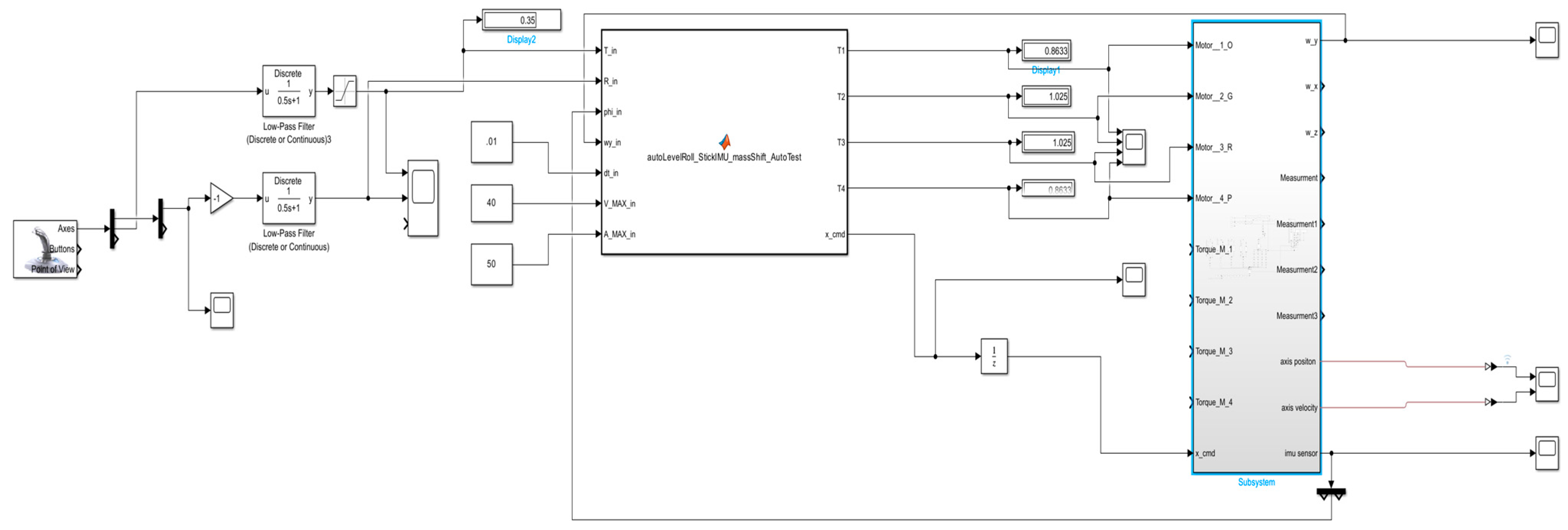

Appendix A.1. Top-Level Simulink Model

Appendix A.2. Internal Subsystem for CoM Shifting Dynamics

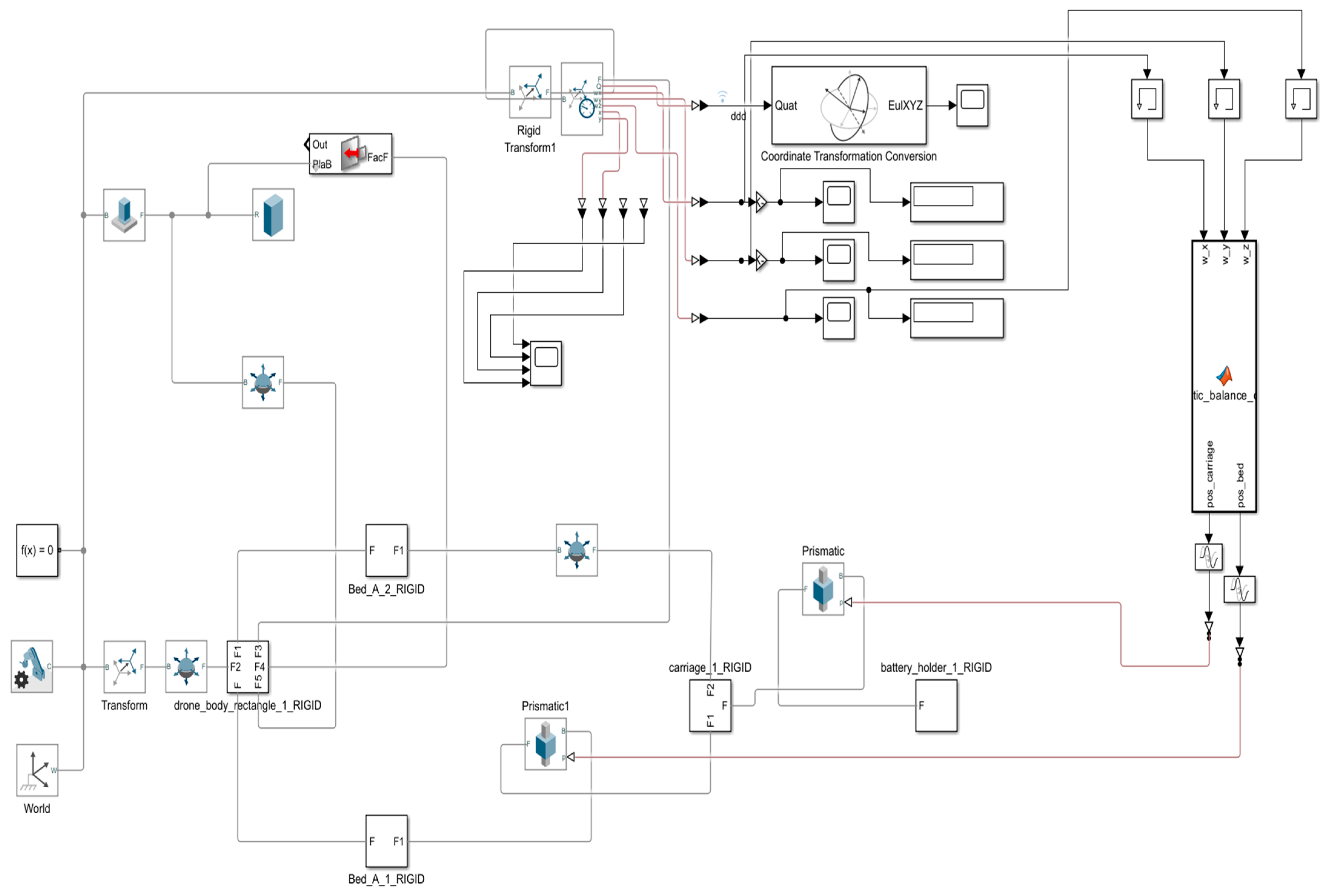

Appendix A.3. Dynamic Model of the UAV Self-Righting Mechanism

References

- Bouabdallah, S.; Murrieri, P.; Siegwart, R. Design and Control of an Indoor Micro Quadrotor. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, New Orleans, LA, USA, 26 April–1 May 2004; IEEE: New Orleans, LA, USA, 2004; Volume 5, pp. 4393–4398. [Google Scholar]

- Farajijalal, M.; Eslamiat, H.; Avineni, V.; Hettel, E.; Lindsay, C. Safety Systems for Emergency Landing of Civilian Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs)—A Comprehensive Review. Drones 2025, 9, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Bhandari, A.; Kumar, P.; Patil, P.P. Modeling and Mechanical Vibration Characteristics Analysis of a Quadcopter Propeller Using FEA. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 577, 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadikhoshkho, Z.; Lipsett, M. Decoupled Control Design of Aerial Manipulation Systems for Vegetation Sampling Application. Drones 2023, 7, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonello, A.M.; Salamat, B. A Swash Mass Unmanned Aerial Vehicle: Design, Modeling and Control. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.06154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Gao, C.; Wang, K.; Jing, W. Attitude Control of a Moving Mass–Actuated UAV Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2022, 35, 04021133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Qin, K.; Tang, F.; Shi, M.; Lin, B. A Novel Attitude Control Strategy for a Quadrotor Drone with Actuator Dynamics Based on a High-Order Sliding Mode Disturbance Observer. Drones 2024, 8, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Hoffmann, G.M.; Waslander, S.L.; Tomlin, C.J. Aerodynamics and Control of Autonomous Quadrotor Helicopters in Aggressive Maneuvering. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Kobe, Japan, 12–17 May 2009; IEEE: Kobe, Japan, 2009; pp. 3277–3282. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, R.M. Principles of Animal Locomotion; Princeton Paperbacks; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-691-12634-0. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, X.; Ge, W.; Miraglia, M.; Inglese, F.; Zhao, D.; Stefanini, C.; Romano, D. Jumping Locomotion Strategies: From Animals to Bioinspired Robots. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaryan, N.; Harutyunyan, M.; Sargsyan, Y. Bio-Inspired Conceptual Mechanical Design and Control of a New Human Upper Limb Exoskeleton. Robotics 2021, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chovancová, A.; Fico, T.; Chovanec, Ľ.; Hubinsk, P. Mathematical Modelling and Parameter Identification of Quadrotor (a Survey). Procedia Eng. 2014, 96, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soe, M.T.; Antony, M.P. Modeling and Control of a Quadcopter: A MATLAB-Based Simulation Framework. 2024, pp. 1–14. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/393067626_Modeling_and_Control_of_a_Quadcopter_A_MATLAB-Based_Simulation_Framework (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Ivaldi, S.; Padois, V.; Nori, F. Tools for Dynamics Simulation of Robots: A Survey Based on User Feedback. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1402.7050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emimi, M.; Khaleel, M.; Alkrash, A. The Current Opportunities and Challenges in Drone Technology. Int. J. Electr. Eng. Sustain. 2023, 1, 74–89. [Google Scholar]

- Pounds, P.; Mahony, R.; Corke, P. Modelling and Control of a Quad-Rotor Robot; Australian Robotics and Automation Association: Perth, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, N.; Hong, S. Fault-Tolerant Control of Quadcopter UAVs Using Robust Adaptive Sliding Mode Approach. Energies 2018, 12, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-J.; Jung, G.-P. A Miniature Jumping Robot Using Froghopper’s Direction-Changing Concept. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Li, J.; Wang, R.; Yang, K. Attitude Control of the Quadrotor UAV with Mismatched Disturbances Based on the Fractional-Order Sliding Mode and Backstepping Control Subject to Actuator Faults. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hehn, M.; D’Andrea, R. A Flying Inverted Pendulum. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Shanghai, China, 9–13 May 2011; IEEE: Shanghai, China, 2011; pp. 763–770. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Yan, L.; Han, Y.; Xie, H.; Zhao, Y. A Survey on the Key Technologies of UAV Motion Planning. Drones 2025, 9, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wan, L.; Li, J.; Hou, K. Adaptive Backstepping Control of Quadrotor UAVs with Output Constraints and Input Saturation. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Song, T.; Yang, B.; Song, G. Fault-Tolerant Control for Multi-UAV Exploration System via Reinforcement Learning Algorithm. Aerospace 2024, 11, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spong, M.W.; Hutchinson, S.; Vidyasagar, M. Robot Modeling and Control; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Falanga, D.; Zanchettin, A.; Simovic, A.; Delmerico, J.; Scaramuzza, D. Vision-Based Autonomous Quadrotor Landing on a Moving Platform. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Safety, Security and Rescue Robotics (SSRR), Shanghai, China, 11–13 October 2017; IEEE: Shanghai, China, 2017; pp. 200–207. [Google Scholar]

| Payload Mass (g) | Maximum Force (N) | Maximum Torque (N·m) | Maximum Roll Angle (rad) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 3.1479 | 0.4174 | 0.90 |

| 100 | 5.1678 | 0.6940 | 1.20 |

| 200 | 9.1835 | 1.2375 | 1.35 |

| Payload Mass (g) | Power Consumption (W) | Time per Adjustment (s) | Energy Consumption (J) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 0.15 | 0.3 | 0.45 |

| 100 | 0.25 | 0.4 | 1.00 |

| 200 | 0.40 | 0.6 | 2.40 |

| Parameter | With CoM Device Disable | With CoM Device Enable |

|---|---|---|

| Max roll deviation (°) | ~90° | <5° |

| Max pitch deviation (°) | ~90° | <5° |

| Final impact orientation | Inverted | Upright |

| Stability retention | <10% | >90% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahmed, A.; Tong, G.; Xu, J. Research on Dynamic Center-of-Mass Reconfiguration for Enhancement of UAV Performances Based on Simulations and Experiment. Drones 2025, 9, 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120854

Ahmed A, Tong G, Xu J. Research on Dynamic Center-of-Mass Reconfiguration for Enhancement of UAV Performances Based on Simulations and Experiment. Drones. 2025; 9(12):854. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120854

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmed, Anas, Guangjin Tong, and Jing Xu. 2025. "Research on Dynamic Center-of-Mass Reconfiguration for Enhancement of UAV Performances Based on Simulations and Experiment" Drones 9, no. 12: 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120854

APA StyleAhmed, A., Tong, G., & Xu, J. (2025). Research on Dynamic Center-of-Mass Reconfiguration for Enhancement of UAV Performances Based on Simulations and Experiment. Drones, 9(12), 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120854