1. Introduction

A quadrotor is an aircraft capable of vertical takeoff and landing [

1]. It is a type of multicopter equipped with four rotors [

2]. Typically, two rotors rotate clockwise, while the other two rotate counterclockwise [

3,

4]. Flight control is achieved by independently varying the speed and torque of each rotor [

5]. The pitch and roll motion of the quadrotor is controlled by changing the net center of thrust, while the yaw motion is controlled by changing the net torque [

6].

The first quadrotors began to be produced by scientists in the early 1900s [

7]. These were manned aircraft operated by a pilot. The first quadrotors were quite large, heavy, and cumbersome. They consumed high fuel and had limited ground clearance. Their range was short [

8]. In the years following World War II, more advanced manned quadrotor prototypes were produced. However, they experienced stability issues, placing a significant burden on the pilot. Furthermore, high costs and some accidents involving manned quadrotors have prevented the mass production of prototypes [

9].

From the 1990s onward, quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) began to develop [

10]. Advances in battery, sensor, software, and hardware technologies have accelerated and simplified the production of quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicles [

11]. Quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicles are much smaller and have a much lower production cost compared to manned quadrotors [

12]. Quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicles can be remotely controlled [

13]. Advancing technology also allows quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicles to be controlled via apps installed on mobile phones [

14]. Furthermore, many quadrotor UAVs are capable of autonomous flight [

15,

16]. Some of the modern quadrotor UAVs have the ability to track the face of the person controlling them remotely [

17,

18]. Small quadrotors that can fly within a room and take off and land in the palm of a hand have become widespread today [

19].

Technological advances have led to an increase in the usage areas of quadrotors. Quadrotors equipped with cameras can be used in areas such as surveillance, hobby photography, and search and rescue operations [

20]. Quadrotors equipped with thermal cameras can detect the body temperature of living creatures, making search operations easier [

21]. Additionally, camera-equipped quadrotors are used by scientists to observe wildlife and by journalists for reporting [

22,

23]. They are also used by security forces for border control and patrols [

24,

25,

26].

Quadrotors that can carry payloads can be used for first aid [

27]. Quadrotors are also used for organ transport between hospitals for transplants [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. Medical quadrotors are also used in operations to transport blood bags and red blood cells [

33,

34,

35]. Thanks to image processing and neural network technologies, quadrotors can detect fires and support firefighting efforts with the payload they carry [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. Payload-carrying quadrotors are also used by cargo companies for cargo delivery [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. Thanks to advanced image processing technologies, cargo drones can deliver cargo to the recipient’s lap or in front of their home [

47,

48]. Quadrotor UAVs carrying payloads are also widely used in agricultural spraying [

49]. Using image processing technologies, they can detect pests on plants. This allows for more accurate and efficient spraying and reduces costs [

50,

51]. Quadrotor UAVs are also widely used in mineral exploration thanks to their advanced image processing technologies and metal detectors [

52,

53,

54]. Quadrotor drones, which carry weapons and ammunition, can be used by security forces against terrorist organizations. These quadrotor drones can track terrorist vehicles, lock on to them, and destroy them [

55,

56,

57]. Furthermore, with their advanced cameras and image processing methods, quadrotor UAVs are widely used in mapping today [

58].

Researchers have written a significant number of review articles on quadrotors. However, most of these review articles focus on quadrotor UAVs within the last 20 years. Therefore, the historical development of quadrotors from the past to the present cannot be fully covered. Idrissi et al. reviewed the development of quadrotor UAVs over the last 18 years. They examined different quadrotor UAV configurations, their mechanical structures, and explained their dynamics. They also addressed simulation tools and control strategies related to quadrotor UAVs [

59]. Sonugur examined the controller designs and simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) methods used in quadrotor UAVs over the last 20 years. He categorized the controller designs he examined into three categories: linear, nonlinear, and intelligent control. He compared the performance metrics of different quadrotors in both controller design and SLAM, and presented the results in tables [

60]. Khalid et al. compared the performance of different control strategies by examining quadrotor UAVs developed over the last 10 years. Their analysis revealed that hybrid control strategies produce improved results compared to conventional control methods [

61]. de Oliveira Evald et al. examined quadrotor UAVs developed over the last 20 years and discussed their attitude control techniques. They categorized attitude controllers into five distinct categories: sliding-mode controllers, higher-order sliding-mode controllers, observer-based controllers, robust controllers, and miscellaneous controllers [

62]. Abro et al. focused on quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicles, which have been developed since the 1990s. They discussed different control strategies for quadrotor UAVs. They addressed PD, PID, MPC, SMC, and reinforcement learning-based control techniques. They also briefly touched on current topics such as autonomous flight, human–UAV interaction, and swarm UAVs [

63].

Some reviews focused on quadrotor UAVs operating in a single domain. Shaipul et al. have written a review article examining payload quadrotor UAVs. They discuss the sectors in which payload quadrotor UAVs can be used, how to upgrade their algorithms, and how to increase their energy efficiency [

64]. Chen et al. wrote a review article on aerial spraying with unmanned aerial vehicles. In their study, they compared the aerial spraying performance of a quadrotor, a hexarotor, and a twin-rotor UAV. They compared the effective wind field and average wind pressure of these UAVs [

65]. Dang et al. wrote a review article on quadrotor UAVs used in mineral exploration. They categorized mines into different categories, such as surface mines, underground mines, and abandoned mines. They explained the type of UAV that should be used for each category [

66]. Ramachandran et al. studied object detection with unmanned aerial vehicles. They classified unmanned aerial vehicles based on their rotor counts as quadrotors, hexarotors, tricopters, and octocopters. Objects in videos captured by these drones’ cameras were detected using different object detection algorithms. The authors compared the advantages and disadvantages of these algorithms [

67]. Shen et al. wrote a review article on the development of hydrogen fuel cell multi-rotor drones. High energy density, strong adaptability to ambient temperatures, and no pollution emissions are presented as advantages of hydrogen fuel cells. Compressed gaseous hydrogen storage methods, liquid hydrogen storage methods, and solid-state hydrogen storage methods are discussed in detail [

68]. Sabour et al. categorize UAVs into six categories based on their intended use: Reconnaissance, Combat, Logistics, Research and Development, Civil and Commercial Applications, and Target and Decoy. They also provide a percentage breakdown of various studies conducted on multi-rotors. Their study focused on the classification and usage areas of UAVs but did not provide information on UAV models or their technical specifications [

69]. Subramaniam et al. analyzed studies examining the aerodynamic performance of various multirotors, such as quadcopters, hexacopters, and octocopters [

70]. Saif et al. wrote a review article examining hybrid power systems developed for multirotor UAVs over the last 20 years [

71]. Throneberry et al. reviewed studies on wake propagation and flow development in multirotor UAVs. The authors examined ground, ceiling, and wall effects within the scope of proximity effects studies. They analyzed hovering flight, forward flight, and vertical flight within the scope of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) [

72].

Table 1 provides a summary of review articles on quadrotors, including the main focus of the articles, the number of examples covered, the years covered, and the reference number of the study.

This study examines in detail the development of quadrotors from their initial invention to the present. This review article examines industrial studies on quadrotors, the technical specifications, production purposes, areas of use, and photographs of landmark quadrotors.

The contributions of this review article can be summarized as follows: Many review articles on quadrotors focus solely on quadrotor UAVs developed in the last 10–20 years. They neglect the historical development of quadrotors and manned quadrotors. This study provides a detailed overview of the development of quadrotors from their initial invention to the present. It examines not only quadrotor UAVs but also both the earliest and current manned quadrotors.

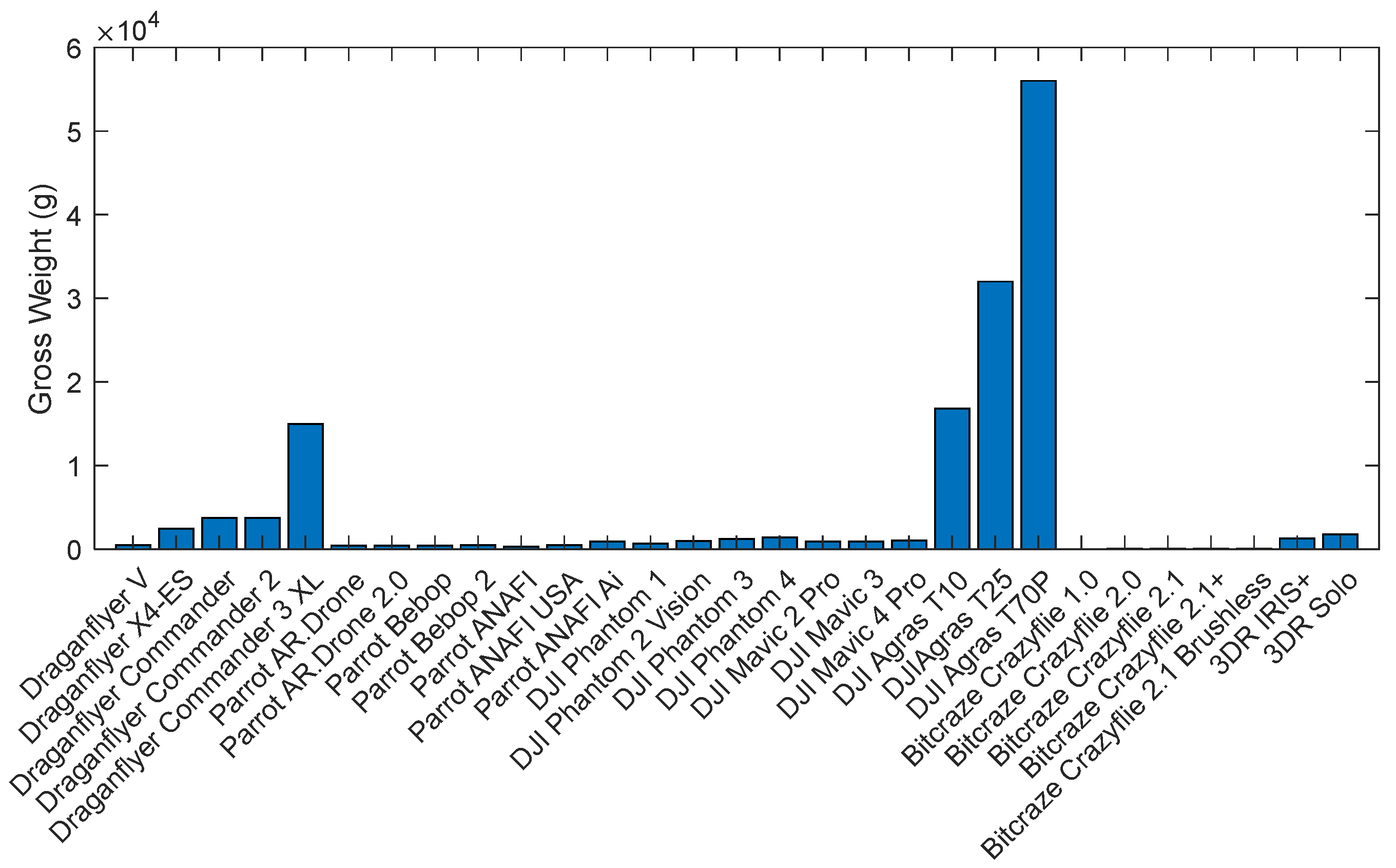

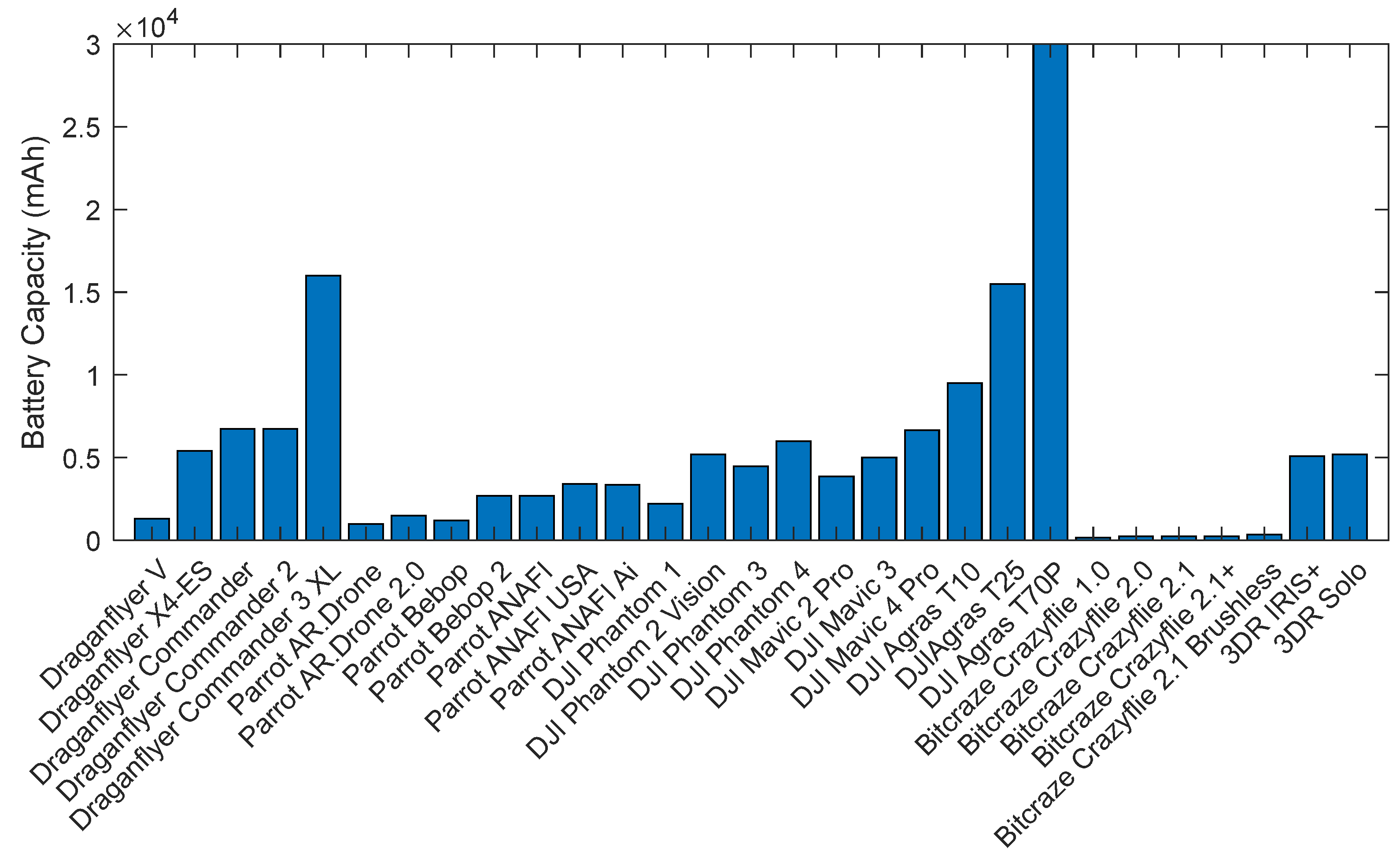

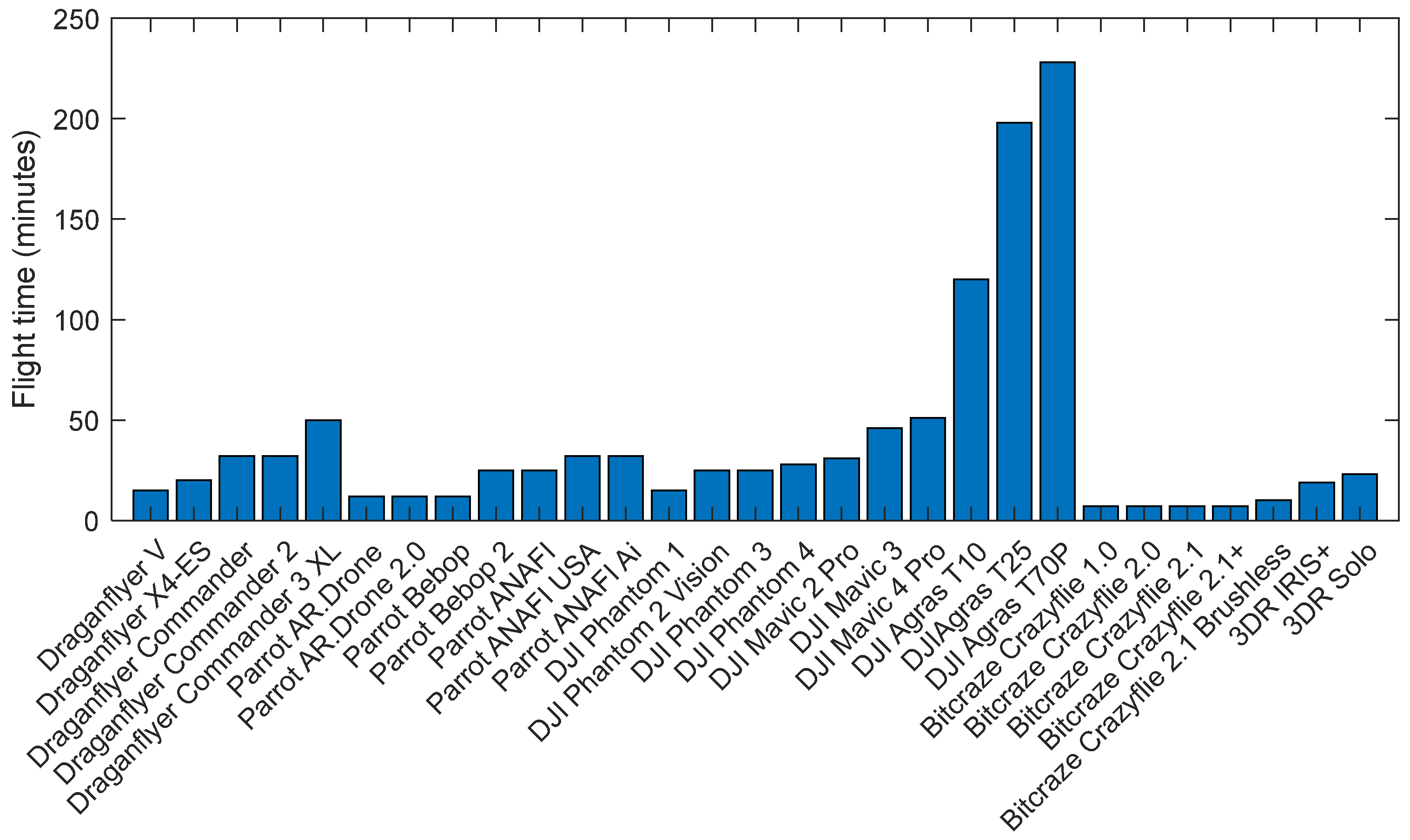

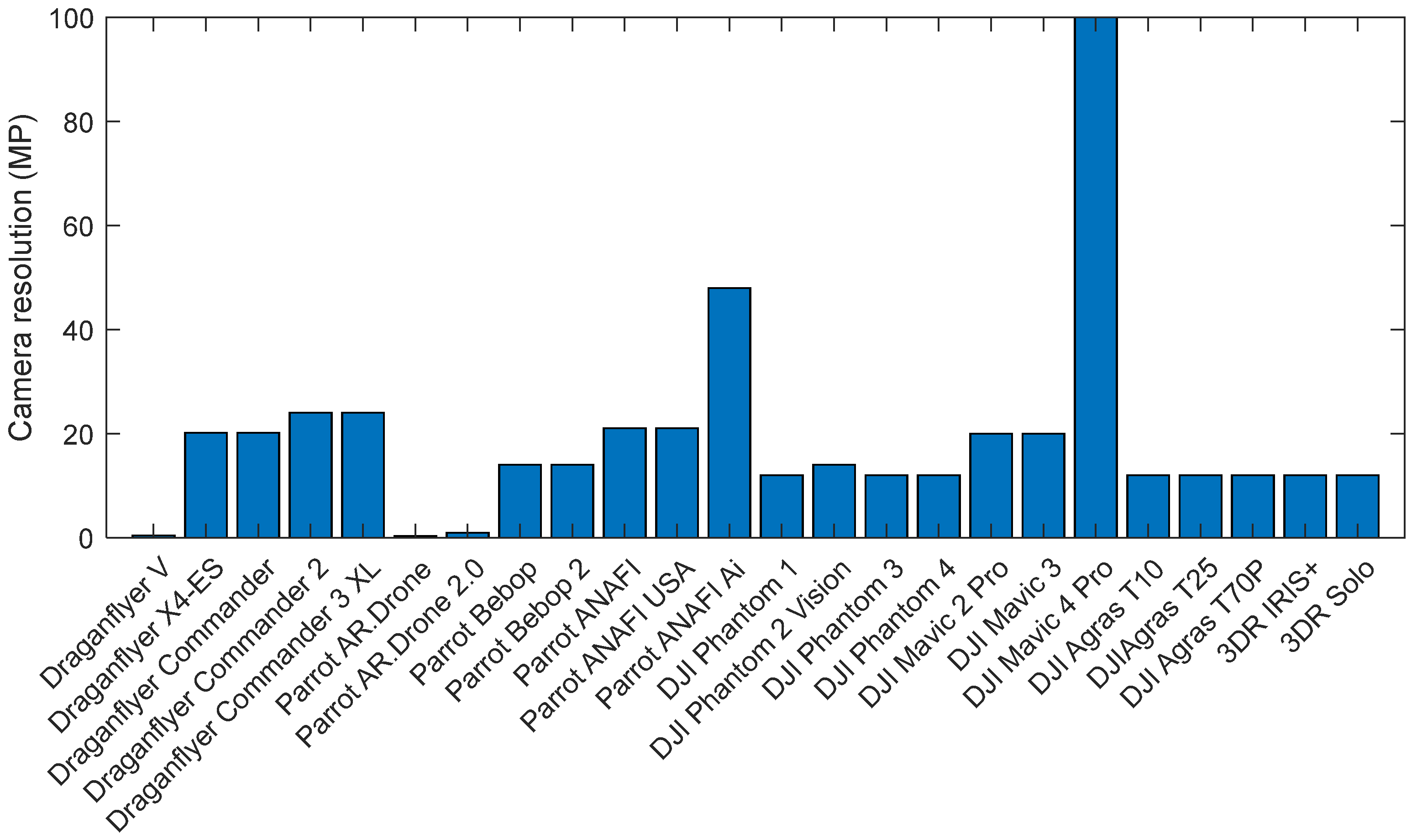

Many review articles on quadrotors mainly focus on the classification of quadrotor UAVs and the control strategies developed for quadrotor UAVs, but their technical specifications are often overlooked. This review article presents in detail the technical specifications of both manned and unmanned quadrotors. The technical specifications of a total of 10 manned quadrotors are presented in tables. Graphs are provided for their weight, powerplant, flight duration, and passenger capacity. The technical specifications of a total of 30 quadrotor UAVs are presented in tables. Graphs are provided for the weight, battery capacity, flight duration, and camera resolution of these quadrotor UAVs.

Some review articles compare quadrotors specialized in a specific area (e.g., payload transport, agricultural spraying, mineral exploration, object detection) with other drones that perform the same function (trirotors, hexarotors, etc.). This review article, instead of focusing on quadrotors specialized in a single area, broadens the scope and addresses all areas of application for quadrotors.

The second section describes the methodology employed in this review. The third section explores the development of manned quadrotors. The technical specifications, production processes, and application areas of these quadrotors are explained. The fourth section discusses quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicles. The operating principles and application areas of quadrotor UAVs are explained. The technical specifications of landmark quadrotor UAVs are reviewed.

Section 5 describes the future directions of manned quadrotors and quadrotor UAVs.

Section 6 presents the conclusions of this review article.

3. Development Stages of the Manned Quadrotors

Historically, the first quadrotors produced were manned quadrotors controlled by a pilot. The production of the first manned quadrotors dates back to the early 20th century. This section describes manned quadrotors in detail, from their earliest production to the present day. The technical specifications of the prototypes, any accidents they were involved in, their intended use, and whether they entered mass production are discussed in detail.

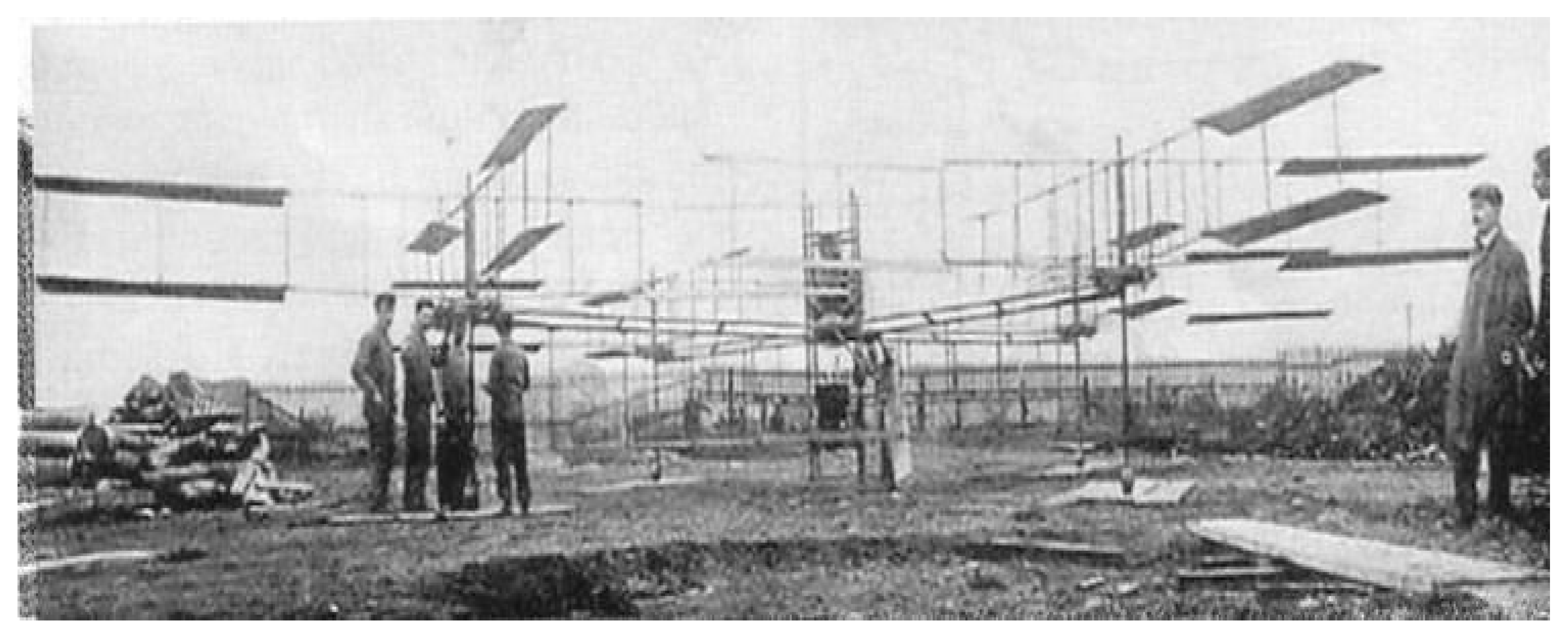

In 1907, French electrical engineer Louis Charles Breguet and his brother, aeronautical engineer Jacques Breguet, along with French psychology professor Charles Richet, developed the first quadrotor, which they named the Bréguet-Richet Gyroplane No. 1. The quadrotor had a seat for the pilot and a central engine. The quadrotor had two steel arms, each constructed in two layers, extending from the center toward the four rotors. To eliminate torque, two rotors rotated clockwise, while the other two rotated counterclockwise. The quadrotor could only move vertically and required four people to maintain stability. The Bréguet-Richet Gyroplane No. 1 rose 0.6 m above the ground on its first attempt. Later improvements allowed it to reach 1.52 m above the ground. Gyroplane No. 1 made its maiden flight on August 24, 1907. A photograph of Gyroplane No. 1 taken in 1907 is shown in

Figure 1. According to the photograph, the person standing on the right is Louis Charles Breguet. The technical specifications of Gyroplane No. 1 are given in

Table 2 [

73].

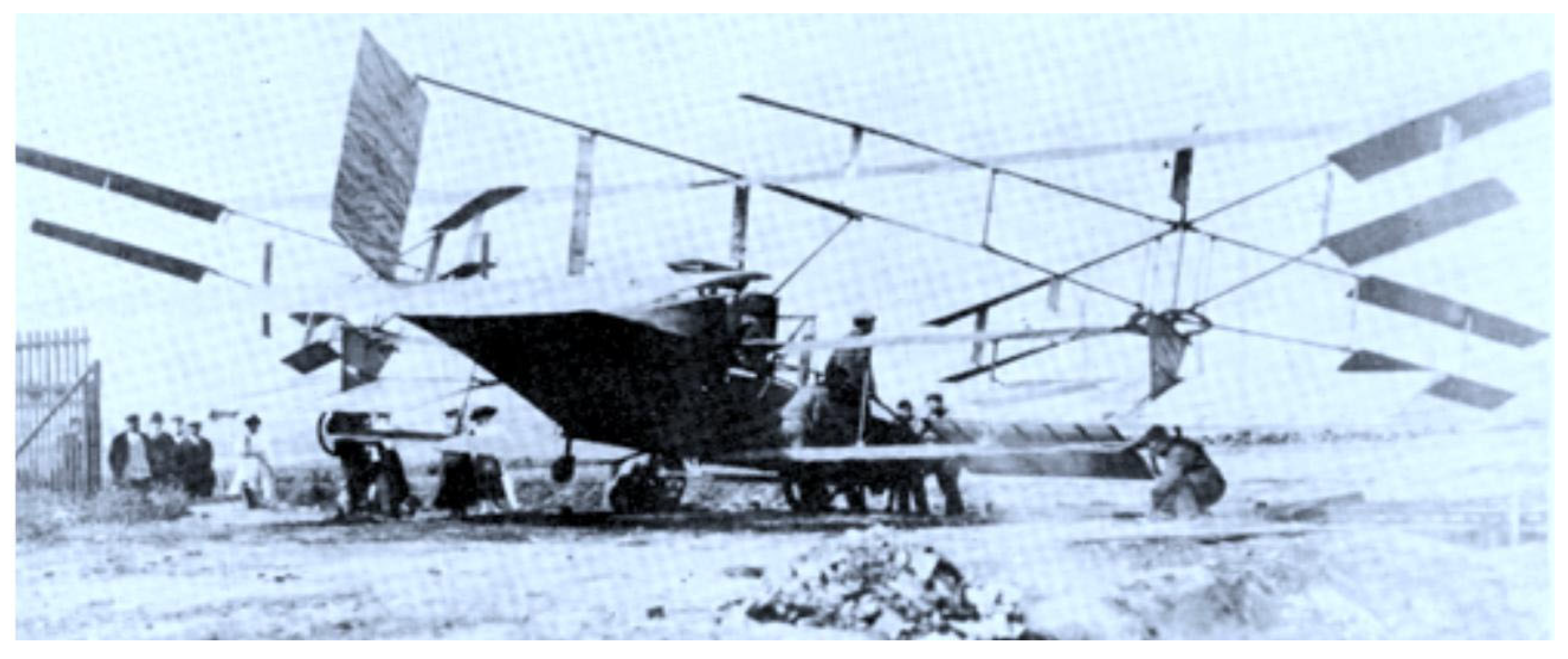

In 1908, the Bréguet-Richet Gyroplane No. 2 was produced, a further development of the existing design. This design used 7.85 m diameter propellers and fixed wings. It was powered by a 55 hp Renault engine. This second version made several successful flights in the summer of 1908 before being severely damaged during a landing on 19 September 1908. After the severe damage, it was repaired and renamed Gyroplane No. 2 bis, making one final flight before April 1909. In April 1909, a severe storm destroyed the company’s quadrotor and all its work [

73]. A photograph of Gyroplane No. 2 taken in 1908 is shown in

Figure 2. The technical specifications of Gyroplane No. 2 are given in

Table 3 [

74,

75].

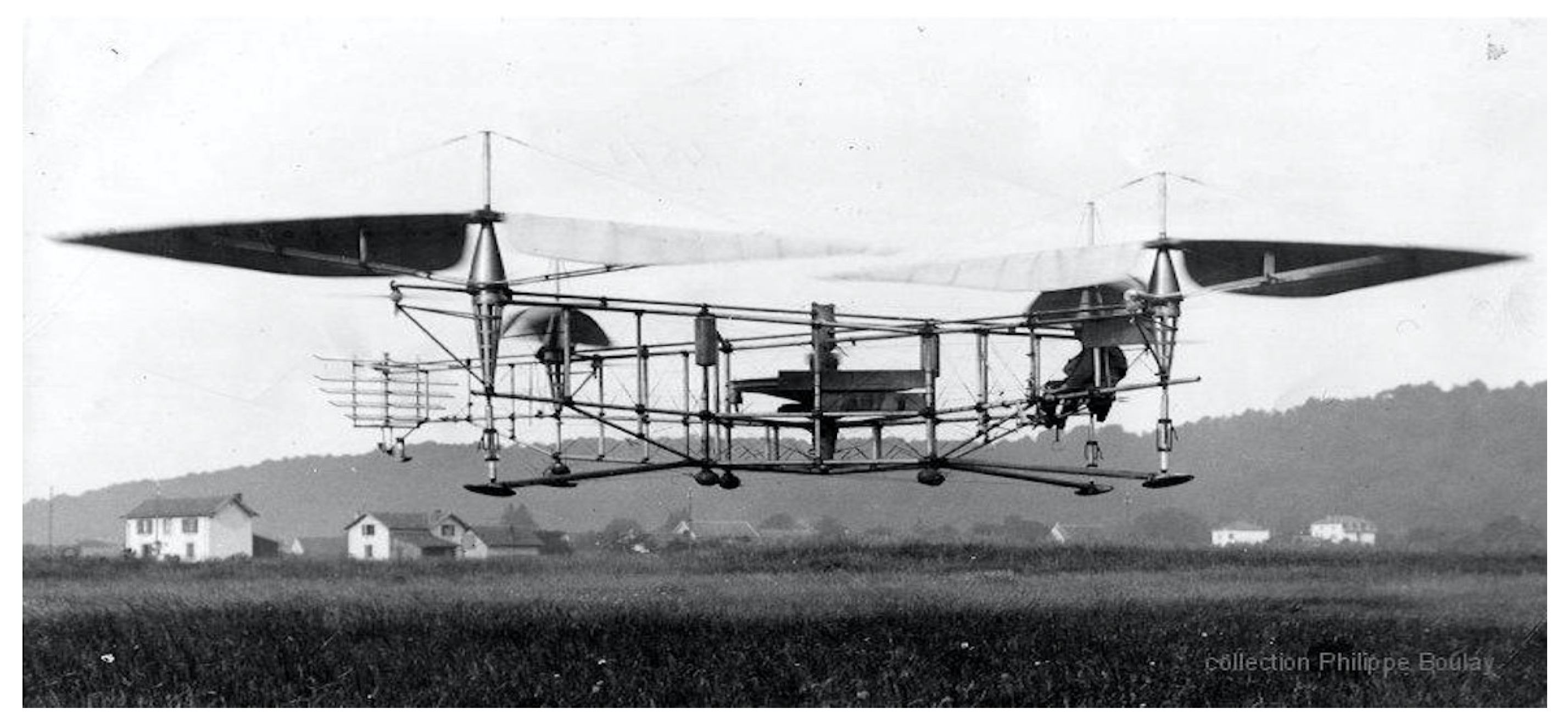

French engineer Etienne Oehmichen, working for Peugeot, began experimenting with rotary-wing designs in the 1920s. His first designs used a 25 hp engine, but this engine failed to generate sufficient lift for takeoff. In 1922, he developed his first notable quadrotor design, the Oehmichen No. 2. It used a 120 hp Le Rhone engine and made its maiden flight on 11 November 1922. The Oehmichen No. 2 later used a 180 hp Gnome engine. The Oehmichen No. 2 had a steel frame. In 1924, the Oehmichen No. 2 broke the record for the longest-flying rotary-wing aircraft by flying 360 m. It later set a new record by flying 525 m. It then followed a triangular trajectory, flying for 7 min and 40 s and covering 1 km. For this achievement, Etienne Oehmichen was awarded 90,000 francs by the French government. In a 1924 flight, the Oehmichen No. 2 remained airborne for 14 min and covered a distance of 1.6 km. In 1924, Etienne Oehmichen successfully completed a flight with the Oehmichen No. 2, carrying two passengers. The technical specifications of the Oehmichen No. 2 are given in

Table 4 [

76,

77,

78]. A photograph of the Oehmichen No. 2 is shown in

Figure 3 [

78].

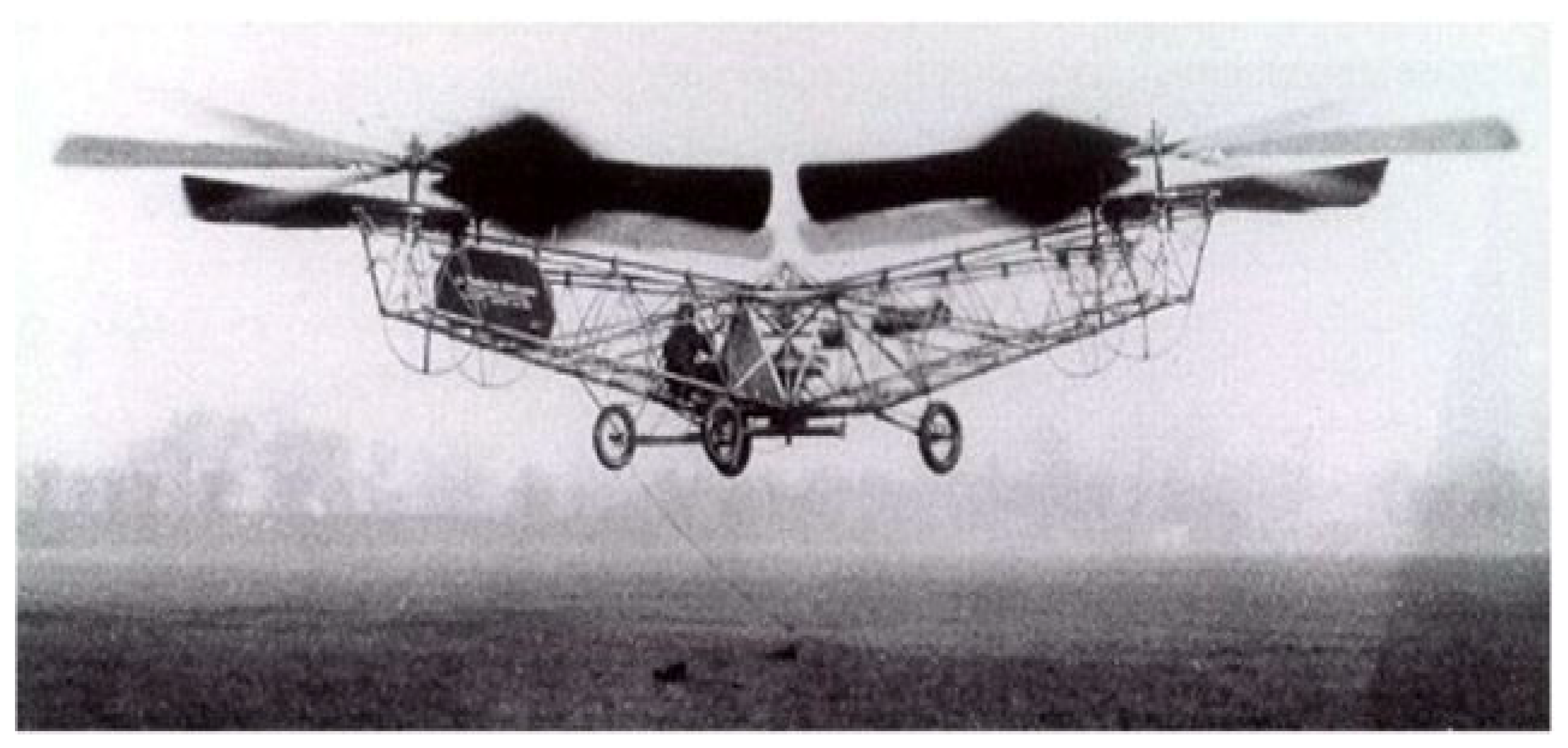

George de Bothezat, a nobleman and scientist of Russian origin, also conducted significant research on quadrotors. He began studying Electrical Engineering at the Kharkiv Polytechnic University in 1902. He then studied Electrical Engineering at the University of Liège in Belgium for two years between 1905 and 1907. He then returned to his homeland and graduated from the Kharkiv Polytechnic University in 1908 with a degree in Electrical Engineering. After graduating, he pursued postgraduate studies at the University of Göttingen and Humboldt University in Berlin. In 1911, he completed his doctorate in aircraft stability at the Sorbonne University. During his academic studies, he focused on winged aircraft rather than general aerodynamic theory. Following the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia in 1918, he emigrated to the United States. There, he taught at MIT and Columbia University and, in 1920, wrote one of the first articles in the scientific literature on rotary-wing unmanned aerial vehicles. At the request of the US Army, he went to Ohio State and began designing one of the first quadrotors. In December 1922, he developed the quadrotor, which he named the “de Bothezat helicopter”. On its first flight, the quadrotor climbed 1.8 m above the ground. In subsequent flights, it reached altitudes of up to 9.1 m. Able to carry a pilot and four passengers, the quadrotor’s maximum speed was determined to be 48 km/h. However, because it could only fly when it caught a favorable wind and was very difficult to control, production of the quadrotor was canceled by the US Army in 1924 [

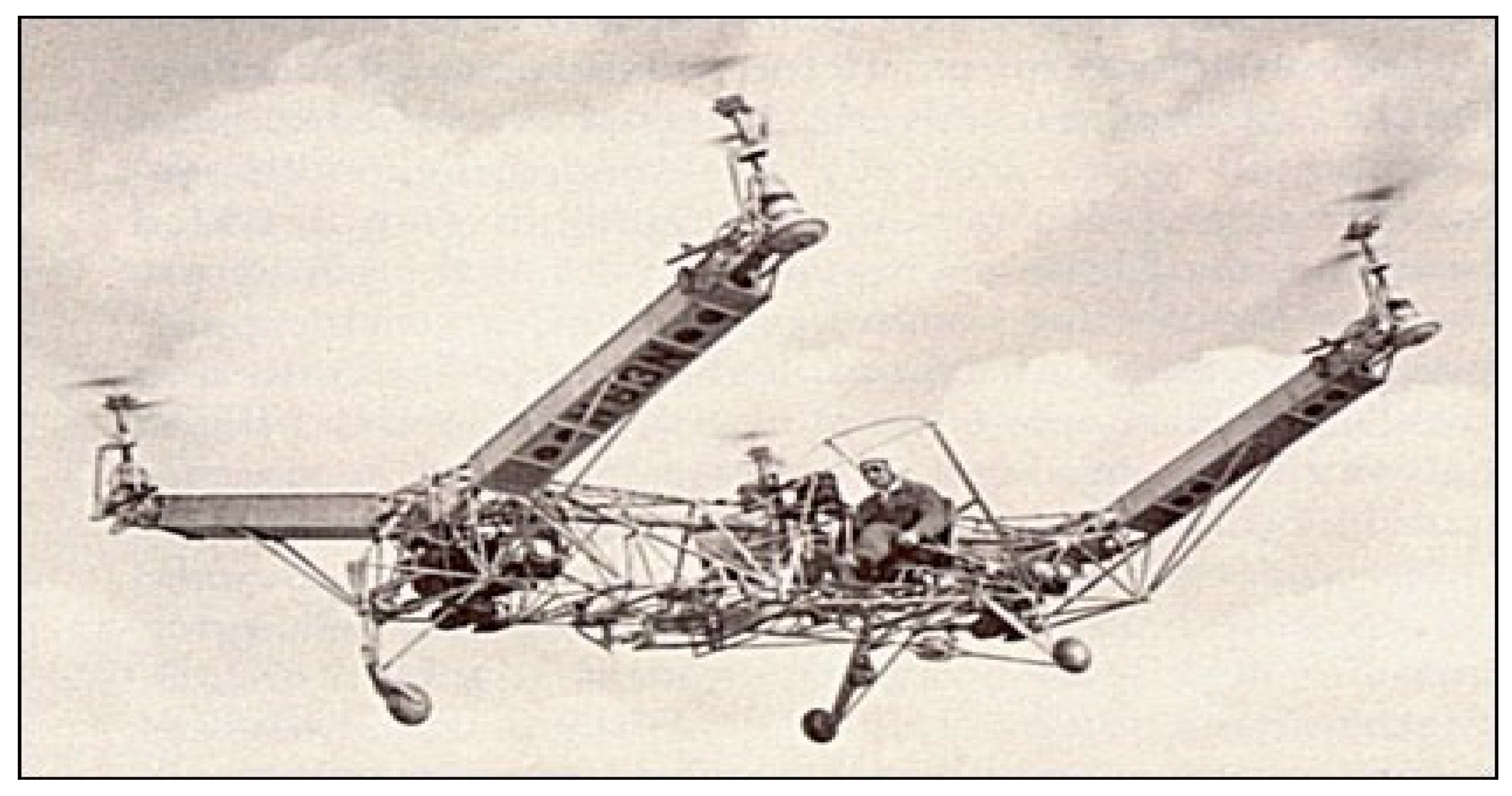

79]. A photograph of the de Bothezat quadrotor taken during a test flight in 1923 is presented in

Figure 4 [

80]. George de Bothezat applied for a patent for the quadrotor he developed in the USA in 1924, and his application was accepted in 1930. The technical specifications of the de Bothezat quadrotor are given in

Table 5 [

81].

The US company Convertawings examined the quadrotors developed by Oehmichen and Bothezat. Using these concepts, they developed a four-propeller concept. In 1955, they produced and successfully flew the first prototype, the Convertawings Model A. The main body of the Convertawings Model A was made of steel, while the arms supporting the four rotors were made of aluminum. The control mechanism was greatly simplified and was achieved by differentially varying the thrust between the rotors. Power was provided by two motors connected to the rotor drive system by multiple V-belts. The shaft and transmission housings provided the interconnection between the four rotors, allowing both motors to operate the quadrotor when needed. Despite successful test flights, production of the Convertawings Model A was discontinued due to budget cuts within the US Army [

82].

Figure 5 shows a photo of the Convertawings Model A taken in 1956 [

83]. The technical specifications of the Convertawings Model A quadrotor are given in

Table 6 [

84].

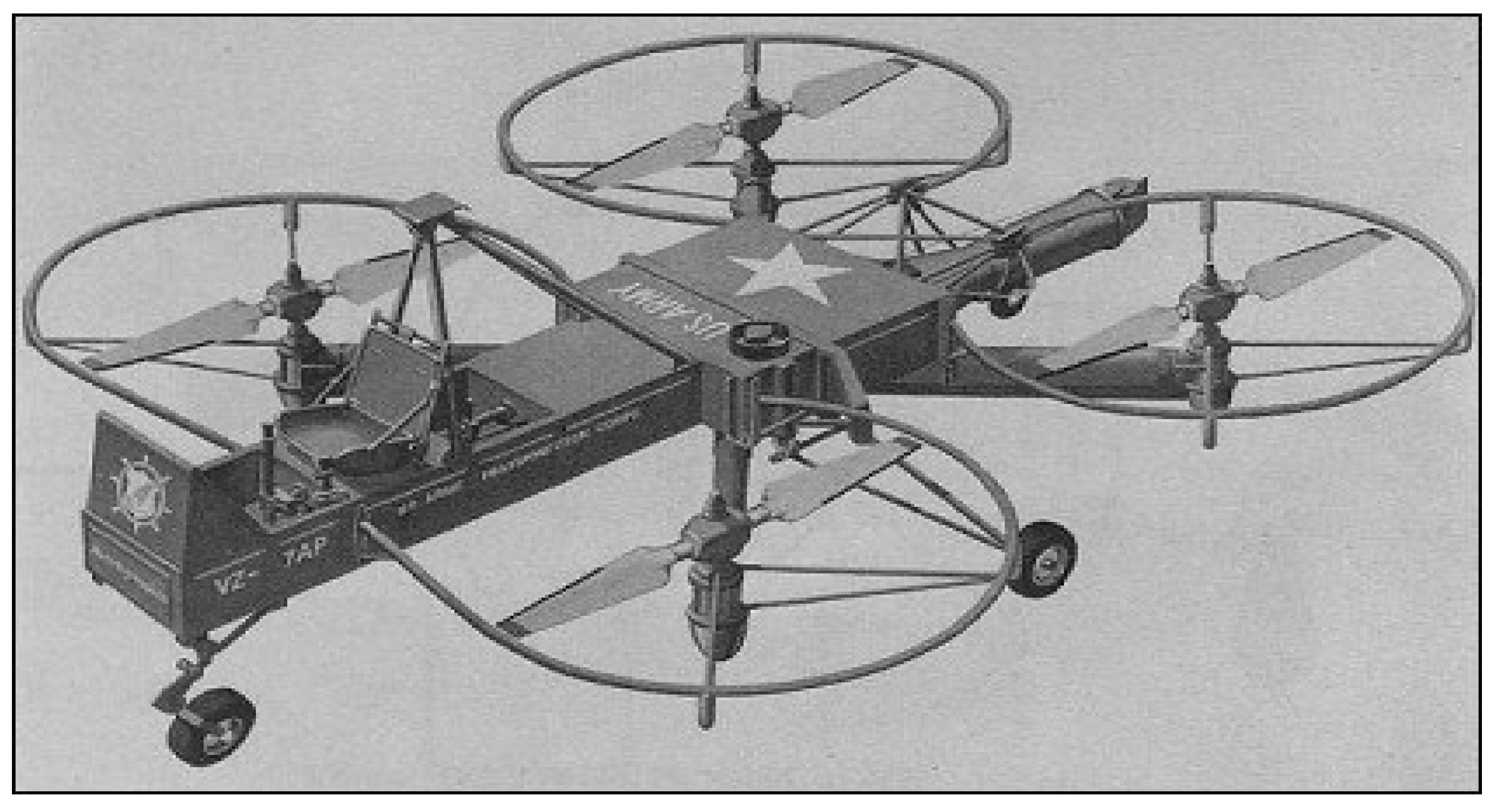

In 1958, the US company Curtiss-Wright produced the Curtiss-Wright VZ-7 quadrotor for use by the US military. The Curtiss-Wright VZ-7 had a pilot’s seat, fuel tanks, and a fuselage with flight controls. The quadrotor, which was controlled by varying the thrust of each propeller, was highly maneuverable and easy to fly. Its cruising speed was 25 mph (40 km/h), and it could reach a maximum speed of 31 mph (50 km/h). It could fly at an altitude of 200 ft (61 m). Although the VZ-7 performed well in tests, its production program was halted in 1960 because it did not meet military standards [

85].

Figure 6 shows a photograph of the Curtiss-Wright VZ-7 quadrotor taken in 1958. The technical specifications of the Curtiss-Wright VZ-7 quadrotor are given in

Table 7 [

86].

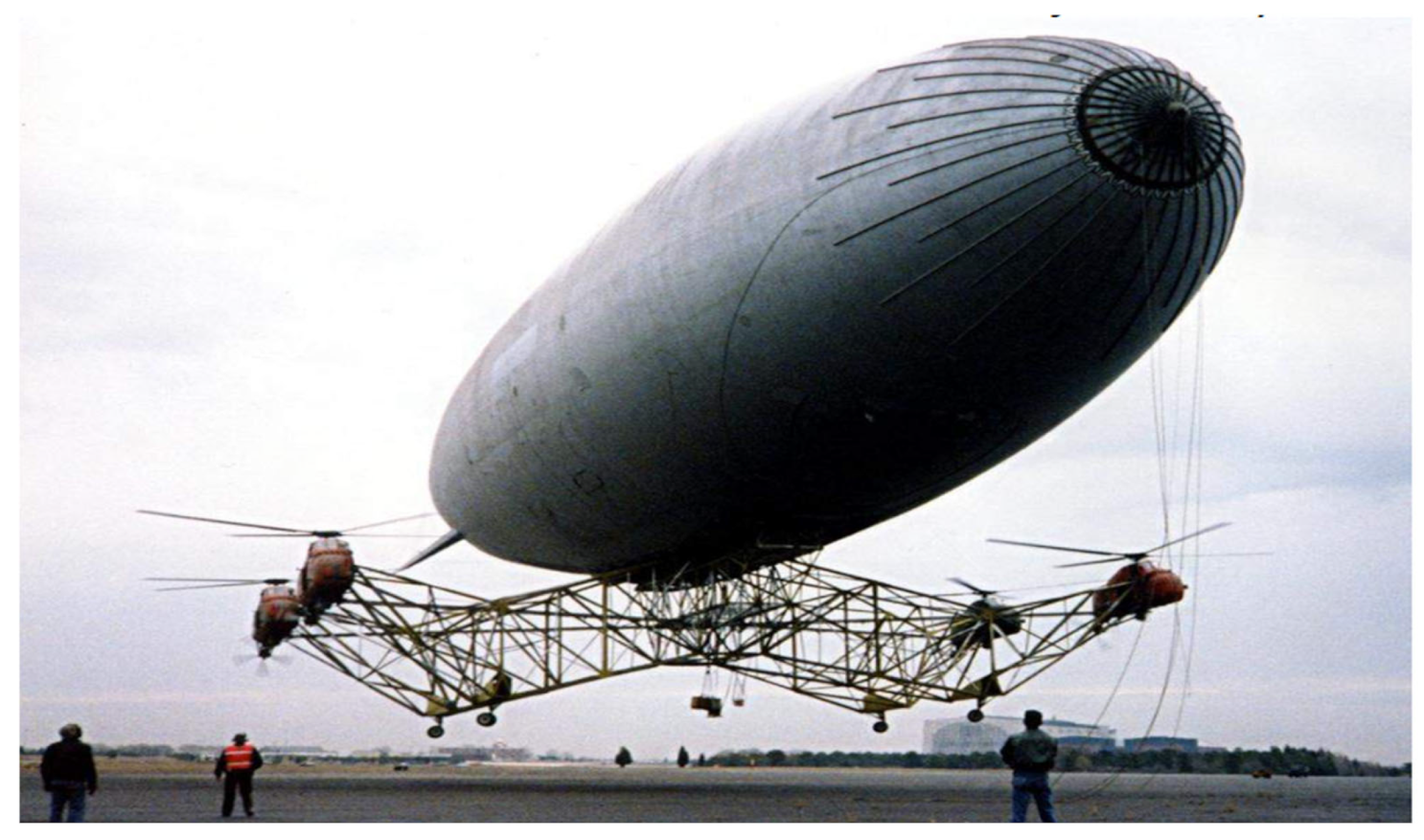

In 1980, the US-based Piasecki Aviation company began designing a quadrotor for the US Navy to lift heavy loads. The Piasecki PA-97 quadrotor was produced for this purpose. The Piasecki PA-97 had an aluminum frame attached to the bottom of a helium-inflated airship. Four Sikorsky H-34J helicopters were attached to the aluminum frame. Criticisms were expressed regarding the structural properties and stress analysis of this frame. It made its first flight on 28 April 1986. On 1 July 1986, a test flight crashed shortly after takeoff, killing one pilot and injuring four others. Production of the Piasecki PA-97 was halted after this accident [

87].

Figure 7 shows a photograph of the Piasecki PA-97 taken in 1986. The technical specifications of the Piasecki PA-97 are given in

Table 8 [

88].

Due to the accidents experienced by pilot-operated quadrotors and their failure to meet US military standards, the use of manned quadrotors in the defense industry was abandoned. This led to the development of quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicles in the 1990s. After a hiatus of approximately 30 years, the mid-2010s saw the introduction of manned quadrotors as air taxis or by aerobatic pilots in demonstration competitions.

Ehang, a Chinese company founded in 2014, began producing manned quadrotors for use as air taxis. In 2015, the company produced the Ehang 184 passenger-carrying quadrotor. The Ehang is an electric quadrotor, controlled by an autopilot and capable of carrying one passenger. It can reach speeds of 130 km/h and operate at altitudes of 500 m. Its range is 16 km. Test flights were conducted in stormy, foggy, and night conditions. It began carrying passengers in 2015 and completed 40 successful trips by February 2018. A total of 40 were produced by July 2018. The Ehang 184 was the first quadrotor to enter mass production among the quadrotors capable of carrying passengers. The technical specifications of the Ehang 184 quadrotor are given in

Table 9 [

89].

Figure 8 shows a photograph of the Ehang 184 quadrotor taken in 2016 [

90].

In 2022, the Swedish company Jetson Aero produced the Jetson One quadrotor. This quadrotor was electric, piloted, and had a flight endurance of 20 min. The quadrotor weighed 115 kg and could reach a speed of 101 km/h. The quadrotor could continue to fly if it lost one of its propellers, but in such a case, it would prompt the pilot to make an emergency landing. Thanks to its onboard LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) sensor, the quadrotor automatically slows down upon approaching the ground, preventing a collision. The company received orders for each Jetson One quadrotor in 2022, priced at

$92,000, and announced delivery in 2023 [

91,

92].

Figure 9 shows a photograph of the Jetson One. The technical specifications of the Jetson One are given in

Table 10 [

92].

Airbus Helicopters began designing a manned quadrotor, called CityAirbus, for use as an air taxi in 2015. Testing of the quadrotor was completed in 2018. It made its maiden flight in 2019. It completed its first crewed flight in 2020. It has completed 242 flights over 1000 km in total. It is designed to carry a total of four passengers and be piloted. In 2021, Airbus announced that it had abandoned the quadrotor design and developed a new design with a fixed wing and V-tail [

93]. In 2025, Airbus announced that it had also abandoned the fixed-wing design and discontinued the air taxi project [

94].

Table 11 provides the technical specifications of CityAirbus [

95].

Figure 10 shows a photo of CityAirbus in 2020 [

96].

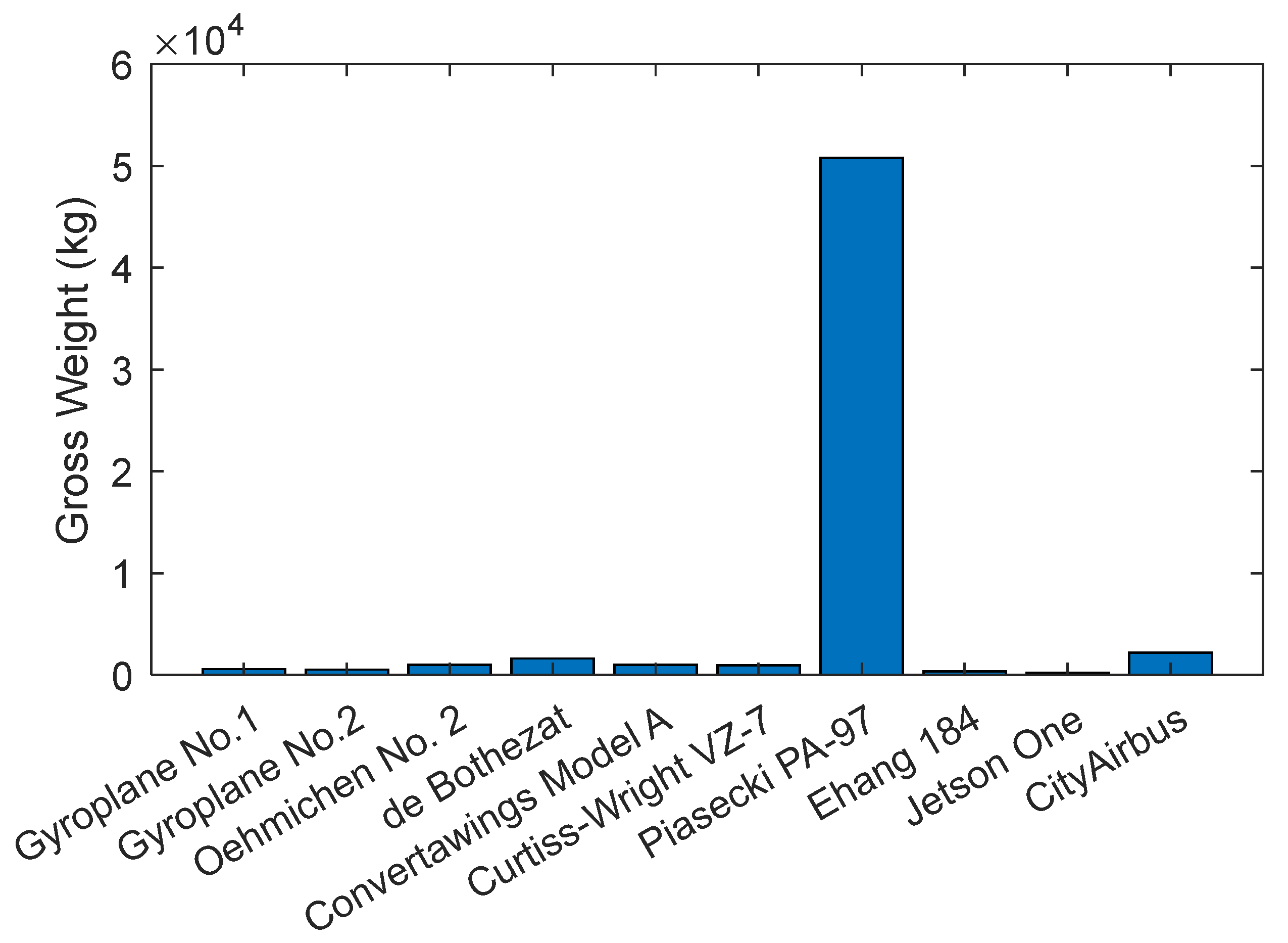

The salient features of manned quadrotors are given in

Table 12. This table highlights the prominent features of manned quadrotor models based on the period in which they were produced.

Table 13 lists selected technical specifications of manned quadrotors. The table lists the weights, power, flight times, and capacities of manned quadrotors. The weight column in

Table 13 shows the gross weights of manned quadrotors. The capacity of a manned quadrotor is given as the total capacity, including passengers and the pilot. The powerplant value of electric motor quadrotors in hp is given in parentheses. Manned quadrotors for which flight time data is not available are marked with a “-” symbol in the table.

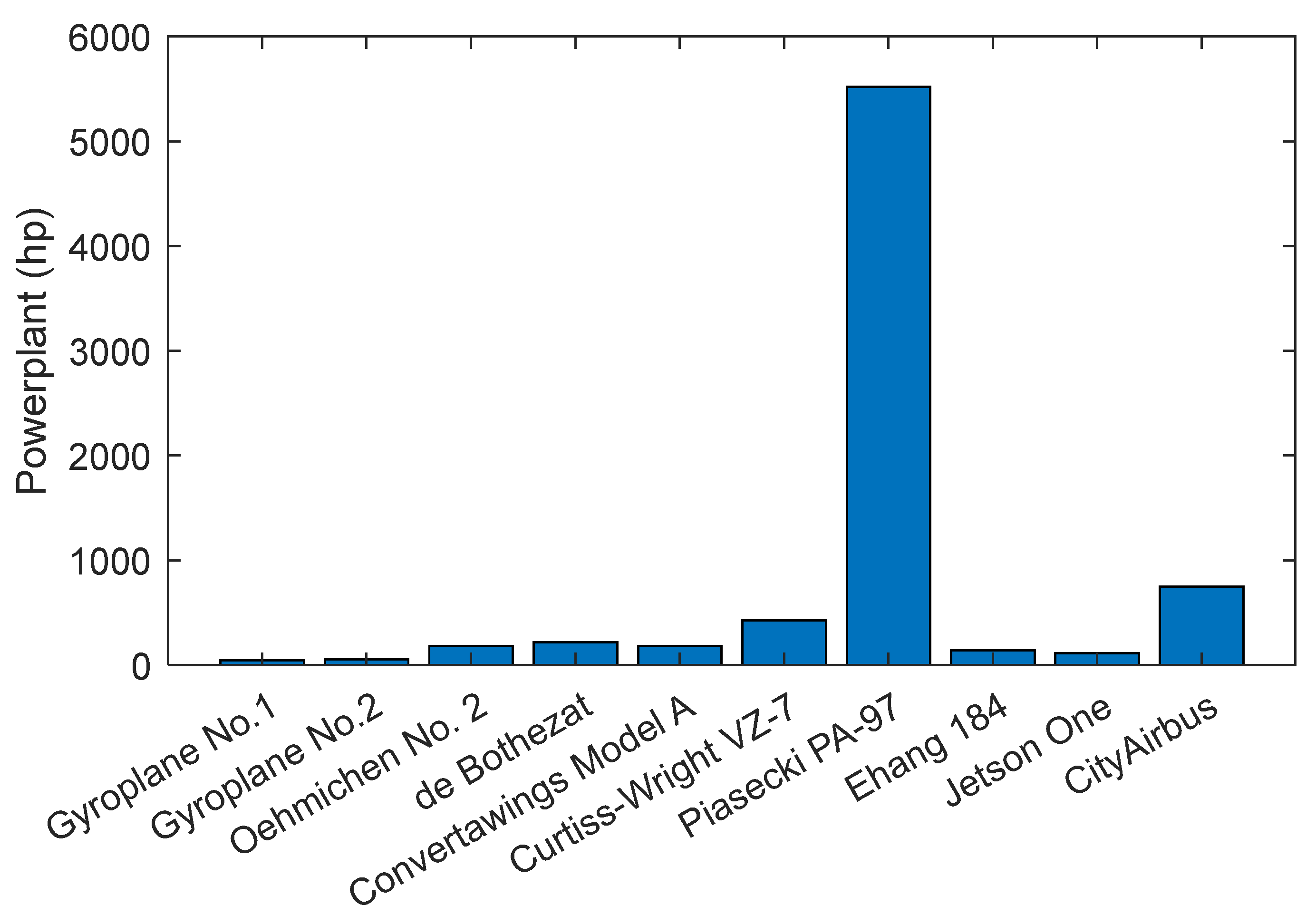

The graph showing the gross weights of manned quadrotors is shown in

Figure 11.

Figure 12 shows the powerplant graph of manned quadrotors. To use a single unit in the graph, the kW values in

Table 13 were converted to hp. 1 kW corresponds to 1.342 hp.

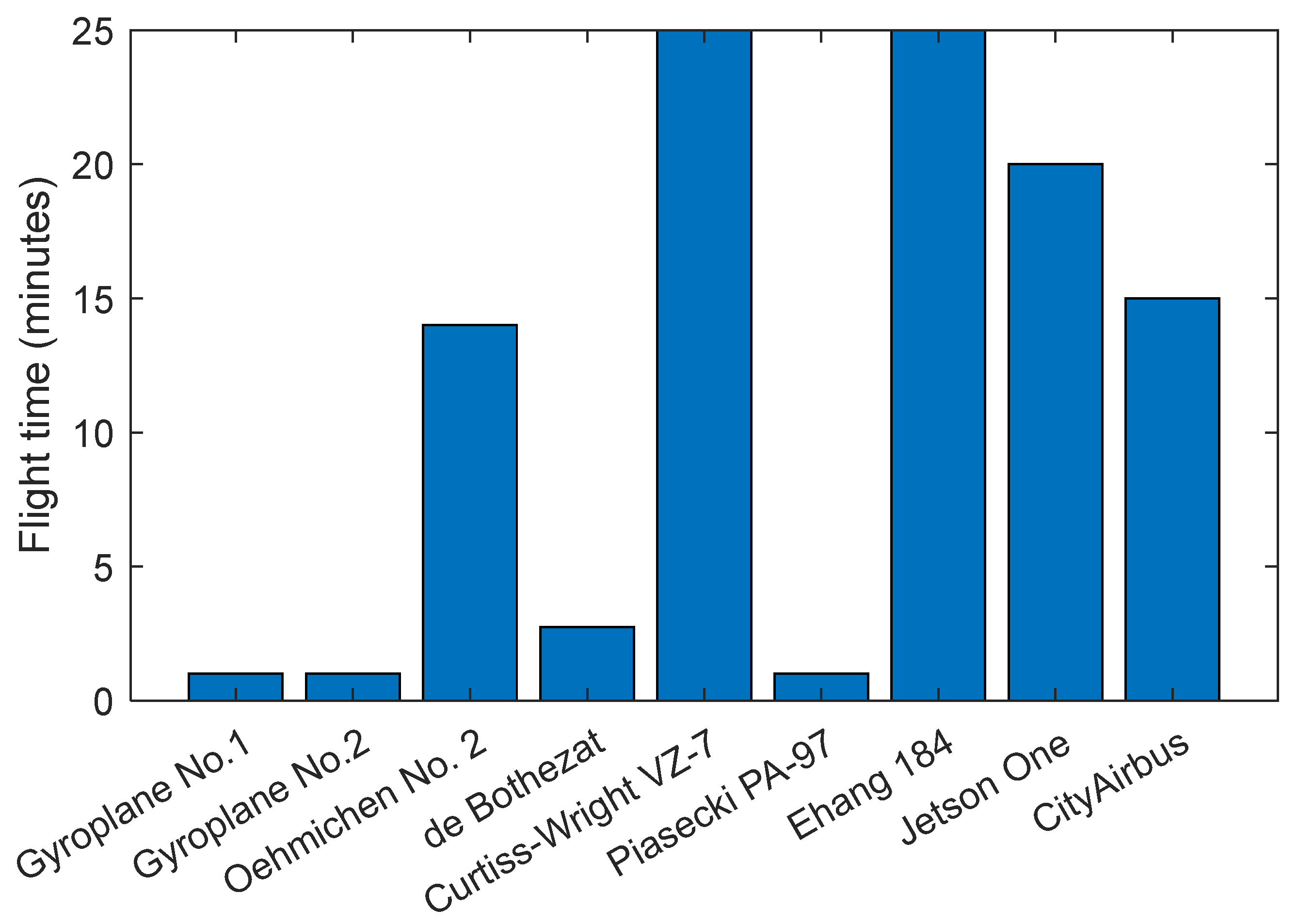

Figure 13 shows the flight times of manned quadrotors. No flight time data was found for the Convertawings Model A, so it is not included in the graph.

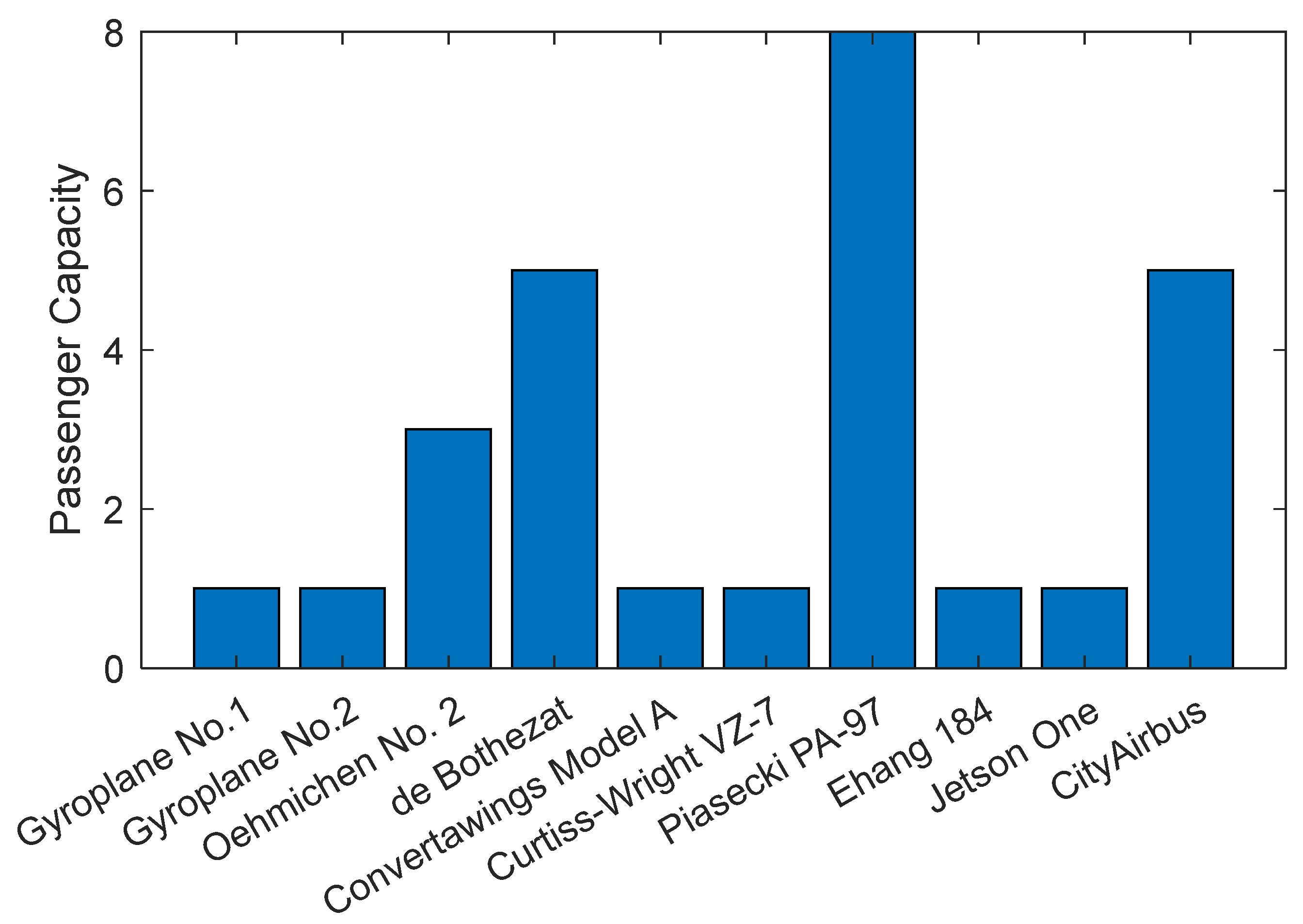

Figure 14 shows the total passenger capacity of manned quadrotors, including the pilot.

When

Figure 11 and

Figure 14 are evaluated together, it is seen that the gross weight and passenger carrying capacity of manned quadrotors are directly proportional. As the passenger-carrying capacity of a manned quadrotor increases, its gross weight also increases. Furthermore, as the gross weight of a manned quadrotor increases, the required engine power also increases. As can be seen from

Figure 12, heavy quadrotors have higher engine power.

Examining the powerplant values of the manned quadrotors in

Figure 12, it is observed that there is a direct proportion between the weight increase and the powerplant value. This is because heavier quadrotors require more power to move. Additionally, starting with the Ehanag 184 manned quadrotor, fossil fuel engine-powered quadrotors have been replaced by electric motor quadrotors.

An examination of the flight times in

Figure 13 reveals a general increasing trend in the flight times of manned quadrotors from Gyroplane No. 1, built in 1907, to the Ehang 184, built in 2015. The de Bothezat and Piasecki PA-97 quadrotors are two examples that contradict this trend. The shorter flight time of the de Bothezat quadrotor than the Oehmichen No. 2 quadrotor is due to the greater number of passengers and its greater weight. The Piasecki PA-97 quadrotor had a very short flight time as it had an accident shortly after take-off. The Jetson One quadrotor’s flight duration is shorter than the Ehang 184. This is due to the Jetson One’s smaller size and lower battery capacity than the Ehang 184. The CityAirbus flight duration is shorter than both the Ehang 184 and the Jetson One. This is due to the CityAirbus’s greater passenger capacity. While the CityAirbus carries five passengers, the Ehang 184 and Jtson One only carry one. The CityAirbus consumes more energy to carry five passengers, which shortens its flight time.

4. Development Stages of the Quadrotor Unmanned Aerial Vehicles

The high production cost, difficulty in controlling, limited range of use, and accidents associated with manned quadrotors have led to almost all manned quadrotors remaining in the prototype stage and not entering mass production. This has paved the way for the development of quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicles. Their small size, low production costs, and ease of control make them advantageous. Advances in hardware, software, sensor, battery, and camera technologies have led to the widespread use of quadrotor UAVs.

The first powered unmanned aerial vehicle was the Aerial Target, a fixed-wing UAV developed by British engineer Low in 1916. Numerous fixed-wing UAVs were produced in the following years, primarily for use in the defense industry [

97]. However, these UAVs do not fall into the quadrotor UAV class because they are fixed-wing, take off from runways, and do not have four rotors. Quadrotor UAVs are UAVs with four rotors capable of vertical takeoff and landing. The development of quadrotor UAVs began in the 1990s. In 1999, the Canadian-based company Draganfly produced the Draganflyer I. In 2001, the company produced the first camera-equipped quadrotor UAV by attaching an integrated camera to the Draganflyer I quadrotor. The Draganflyer I is significant as it became the first quadrotor UAV to achieve large-scale mass production, moving the technology from a research curiosity to a commercial product [

98]. A photograph of the Draganflyer I quadrotor is shown in

Figure 15 [

99].

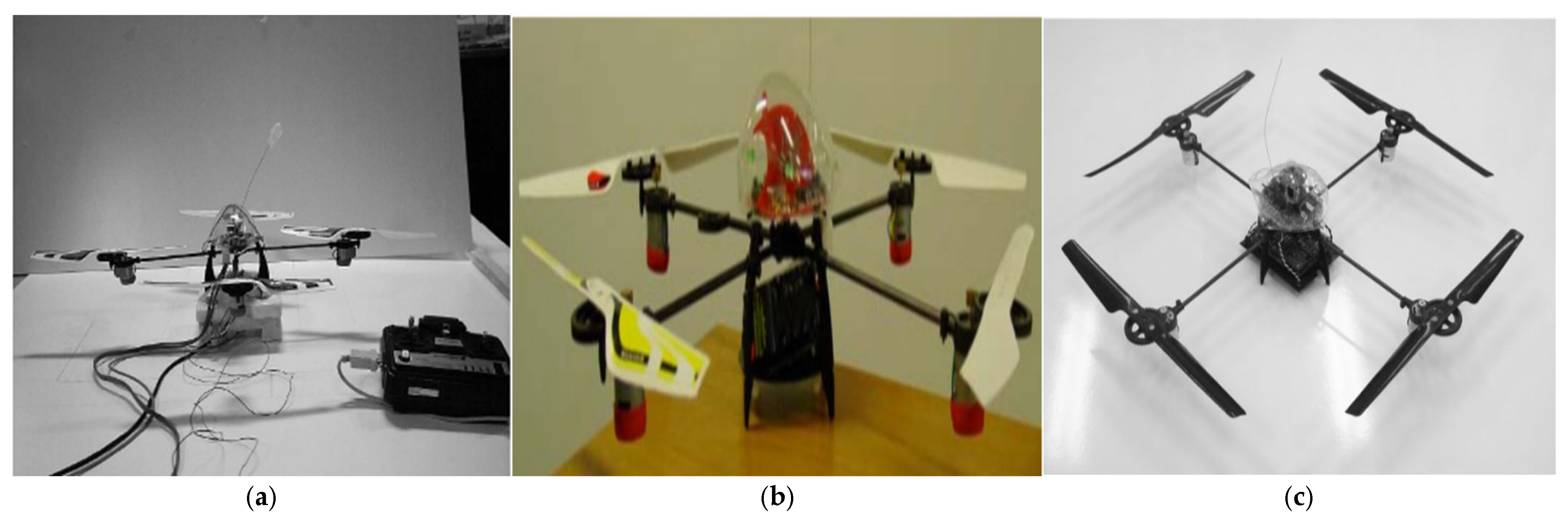

Draganfly launched new models of the Draganflyer quadrotor in the early 2000s, with minor improvements. The series continued from the Draganflyer I, produced in 1999, to the Draganflyer V. Photographs of the Draganflyer III, IV, and V are shown in

Figure 16.

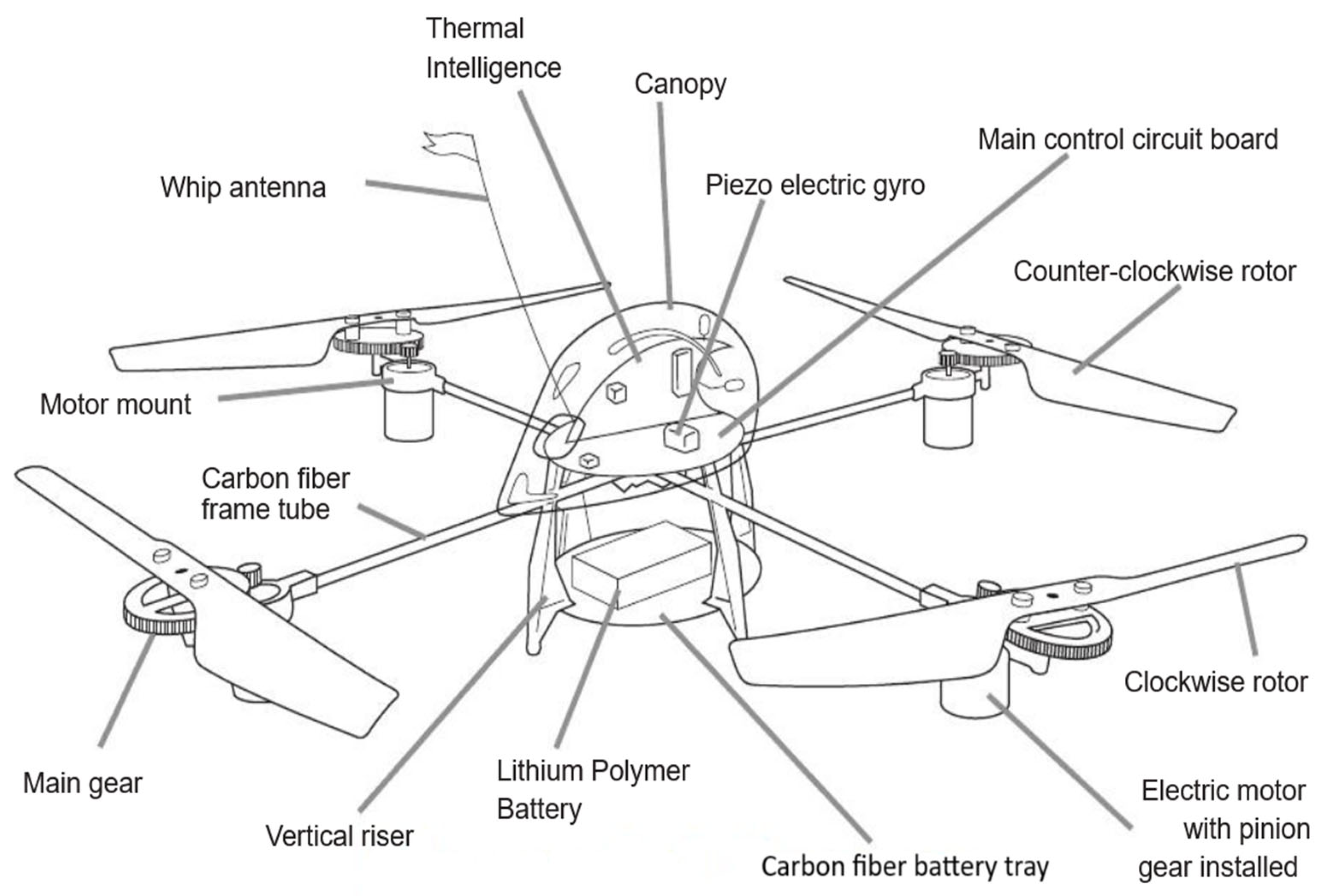

The components of the Draganflyer V are shown in

Figure 17. The Draganflyer V’s technical specifications are provided in

Table 14 [

103].

Draganfly has developed drones with more advanced cameras, real-time video transmission, a larger payload, and longer flight endurance. These drones have been used by US and Canadian police in search and rescue operations and evidence collection since 2009 [

104,

105].

Draganfly company produced the quadrotor called X4-ES in 2013. In 2013, a Draganflyer X4-ES quadrotor was used by the Canadian Mounted Police to locate an injured man whose car had overturned in a remote wooded area in freezing weather. The injured man was located and treated. This marked the first time in history that a search and rescue quadrotor saved a human life [

106]. The technical specifications of the Draganflyer X4-ES are provided in

Table 15 [

107]. A photograph of the Draganflyer X4-ES is shown in

Figure 18 [

108].

Following the X4-ES, Draganfly produced the Draganflyer Commander quadrotor in 2015, which boasted more advanced features. The Draganfly Commander quadrotor boasts longer flight endurance than the X4-ES, smoother takeoffs and landings, and can be controlled via a mobile phone app. It also features two battery packs to protect against battery failure [

109]. The Commander quadrotor was developed for agricultural applications covering up to 100 acres, as well as land surveying, aerial 3D modeling, mapping, and search and rescue applications. The Draganflyer Commander’s technical specifications are provided in

Table 16 [

110].

Draganfly launched the Draganflyer Commander 2 in 2021. Compared to the previous generation, the Commander 2 features new operational capabilities, new sensors, new flight controls, and Mav-Link-based mission planning software. It also features a thermal camera. It was developed for agriculture, mapping, public safety, and photography. Technical specifications of Draganflyer Commander 2 are provided in

Table 17 [

111].

Draganfly company launched the Draganflyer Commander 3 XL quadrotor in 2023. This quadrotor was developed for surveillance, mapping, and search and rescue missions, as well as heavy lifting. It has a payload capacity of up to 10 kg and features a 360-degree camera view. With a flight time of 50 min, it offers a longer flight time than previous Commander-series quadrotors. It can be customized using a variety of communication options such as Microhard PDDL, Herelink Blue, Doodle Labs Helix and DTC BluSDR. Microhard PDDL has a transmission range of up to 2 km, Herelink Blue up to 5 km, Doodle Labs Helix and DTC BluSDR up to 10 km. It has two batteries. Its flight speed of 72 km/h is approximately 1.5 times faster than previous drones in the series. The technical specifications of the Commander 3 XL quadrotor are given in

Table 18 [

112,

113].

Draganfly company launched the Draganflyer Commander 3 XL Hybrid quadrotor in 2024. Because the Commander 3 XL Hybrid operates using gasoline or heavy fuels, it has a much longer flight time than previous drones in the Commander series. The technical specifications of the Commander 3 XL Hybrid quadrotor are given in

Table 19 [

114].

Photographs of the Draganflyer Commander, Commander 2, Commander 3 XL and Commander 3 XL hybrid are shown in

Figure 19.

In 2010, the French company Parrot developed the Parrot AR.Drone, a quadrotor controlled via apps installed on iOS and Android mobile phones and tablets. Its body is made of nylon and carbon fiber for a lightweight design. It has two interchangeable bodies for indoor and outdoor use. The indoor body wraps around the wings for protection. The onboard computer runs a Linux operating system and communicates with the pilot via a self-generated Wi-Fi access point. The rotors are powered by an 11.1-volt lithium polymer battery. It has four 15-watt brushless motors. This provides a flight time of approximately 12 min at 5 m/s. The quadrotor’s body is 57 cm in diameter and has USB and Wi-Fi 802.11b/g interfaces. The front camera is a QVGA sensor with a 93° lens. The vertical camera has a 64° lens, recording up to 60 fps. The technical specifications of the Parrot AR.Drone are provided in

Table 20 [

119].

In 2012, the Parrot AR.Drone 2.0 was released. The camera quality was improved to 720p (0.9 MP). New, more sensitive sensors were used. The Wi-Fi hardware was upgraded to meet the 802.11n standard. The indoor and outdoor versions of the Parrot AR.Drone 2.0 are shown in

Figure 20. The indoor version is shown on the left of

Figure 20, and the outdoor version is shown on the right. The technical specifications of the Parrot AR.Drone 2.0 are provided in

Table 21 [

120].

The Parrot AR.Drone has become one of the best-selling quadrotors in the world, with over 500,000 units sold by 2014 [

121]. The Parrot AR.Drone received the CES (Consumer Electronics Show) Innovations Award in 2010 [

122]. The Parrot AR.Drone was a pivotal model that made drone technology available for the masses. Its control via smartphone apps and its game-like interface created an entirely new consumer market for quadrotors, positioning them as accessible gadgets rather than specialized tools. In 2012, Parrot acquired 57% of the drone company SenseFly, a spin-off of EPFL, and 25% of the photogrammetry company Pix4D, also a spin-off of EPFL [

123]. In 2014, it increased its ownership in Pix4D to 57% [

124]. In 2023, Parrot signed a strategic partnership agreement with Tinamu, a spin-off of ETH Zurich. Under this agreement, Tinamu committed to developing software that would enable Parrot’s drones to self-navigate in challenging indoor environments [

125].

In 2014, Parrot produced the AR.Drone 3.0, codenamed Bebop. The AR.Drone 3.0 featured a more advanced camera than previous versions, a more robust Wi-Fi connection, and could fly up to 2 km using the Skycontroller. It can also be controlled via a mobile application downloaded to Android and iOS mobile phones. Images of the Parrot Bebop and Skycontroller are shown in

Figure 21. The technical specifications of the Parrot Bebop drone are shown in

Table 22 [

126,

127].

Parrot released the Bebop 2 model in 2015. This model has a longer flight time, a more powerful battery, a longer Wi-Fi range, a higher-quality camera, and an image stabilization system. It can also fly faster than the previous model and withstand higher wind speeds, and has a more advanced Skycontroller.

Figure 22 shows the Parrot Bebop 2 drone and the Skycontroller black edition. The technical specifications of the Parrot Bebop 2 drone are shown in

Table 23 [

128,

129].

In 2018, Parrot produced the ANAFI quadrotor with 4K HDR and a 21-megapixel camera. Parrot received

$11 million in funding from the U.S. Department of Defense in 2019 to develop a prototype of a next-generation reconnaissance drone that “can fly continuously for 30 min at a range of up to 3 km,” weighs 3 pounds or less, and “takes less than 2 min to assemble and fit into a soldier’s standard backpack”. A photo of the Parrot ANAFI is shown in

Figure 23 [

130,

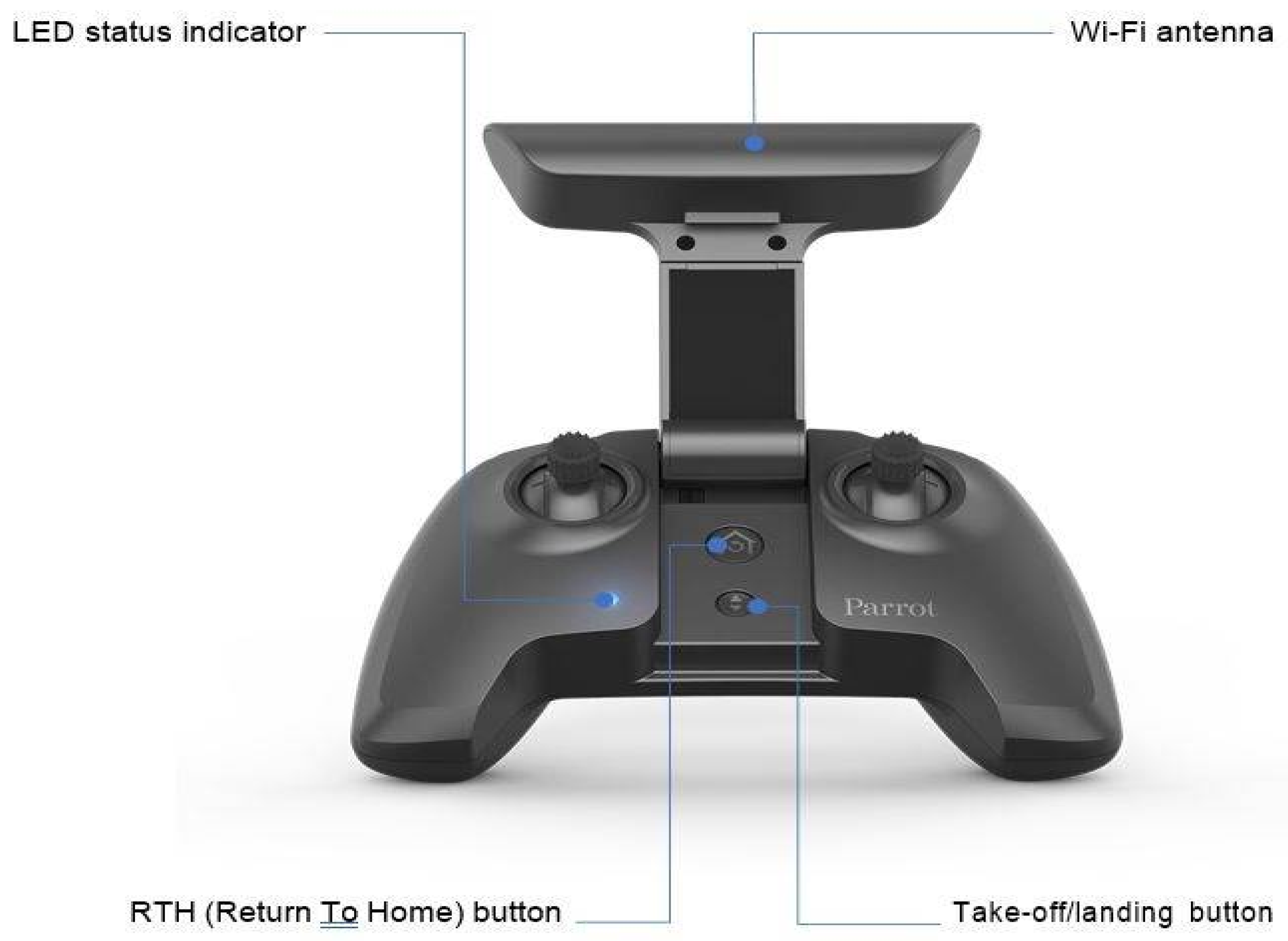

131]. The Parrot ANAFI comes with a Skycontroller 3. By connecting a mobile phone to the Skycontroller 3, a connection is established between the mobile phone’s screen and the quadrotor’s camera.

Figure 24 shows an image of the Skycontroller 3 [

132]. The technical specifications of the Parrot ANAFI are provided in

Table 24 [

133].

In 2020, Parrot produced the ANAFI USA drone. The ANAFI USA drone was used by several NATO countries (the United States, UK, France, Italy, Belgium, Sweden, Finland, Poland, Spain, Luxembourg) and Japan, Australia, Singapore, and Malaysia [

134]. In 2021, Parrot signed a contract with the French army for 300 drones [

135]. The ANAFI USA features a 32× zoom, a thermal camera, and high cybersecurity with data encryption. It is ready for flight in as little as 55 s. The image of the ANAFI USA drone is shown in

Figure 25. The technical specifications of the Parrot ANAFI USA are provided in

Table 25 [

136].

In 2021, Parrot produced the Parrot ANAFI Ai quadrotor for inspection and mapping. ANAFI Ai has a 48 MP camera, 4G connectivity, can perform automated missions and protects user data. The ANAFI Ai is the first drone to utilize 4G connectivity. The ANAFI Ai can automatically find the best trajectory for its mission. The ANAFI Ai features an omnidirectional camera that can rotate in all directions. A photograph of the ANAFI Ai and Skycontroller 4 is given in

Figure 26. Unlike previous controllers, the new Skycontroller 4 offers an HDMI input. It is also compatible with the iPad Mini and larger smartphones [

137]. The technical specifications of the Parrot ANAFI Ai are provided in

Table 26 [

138].

China-based DJI has produced numerous quadrotors for aerial photography and videography. In 2013, it released the DJI Phantom 1. The DJI Phantom 1 did not include a built-in camera. However, a GoPro HERO 3 camera could be optionally mounted on the DJI Phantom 1. The DJI Phantom 1’s technical specifications are listed in

Table 27 [

139]. A photo of the DJI Phantom 1 with a GoPro HERO 3 camera is provided in

Figure 27 [

140].

The DJI Phantom 1 defined the modern consumer drone platform by integrating GPS and sophisticated flight controllers, which provided remarkable stability and ease of use, thereby unlocking the potential for reliable aerial photography and videography.

In late 2013, DJI released the DJI Phantom 2 Vision. The DJI Phantom 2 Vision features a 14 MP camera and a flight time of 25 min. It has a longer flight time than the DJI Phantom 1, a more powerful battery, and is faster and heavier. The technical specifications of the DJI Phantom 2 Vision are provided in

Table 28 [

141]. The image of the DJI Phantom 2 Vision is shown in

Figure 28 [

142].

DJI released the Phantom 3 quadrotor in 2015. The Phantom 3 is faster and weighs more than the Phantom 2. The maximum flight time and dimensions of the Phantom 2 and Phantom 3 are the same. Their operating frequency is the same. The DJI Phantom 3 has a 12-megapixel camera capable of recording 2.7 K video at 30 fps and a 94-degree field of view, ideal for wide-angle shots. A photo of the DJI Phantom 3 is shown in

Figure 29. The technical specifications of the DJI Phantom 3 are shown in

Table 29 [

143].

DJI released the Phantom 4 quadrotor in 2016. Its flight time is longer than that of other quadrotors in the Phantom series. It is faster than all previous quadrotors in the series and has a more powerful battery. It has a 12.4-megapixel camera. The technical specifications of the DJI Phantom 4 are given in

Table 30. A photograph of the DJI Phantom 4 is given in

Figure 30 [

144].

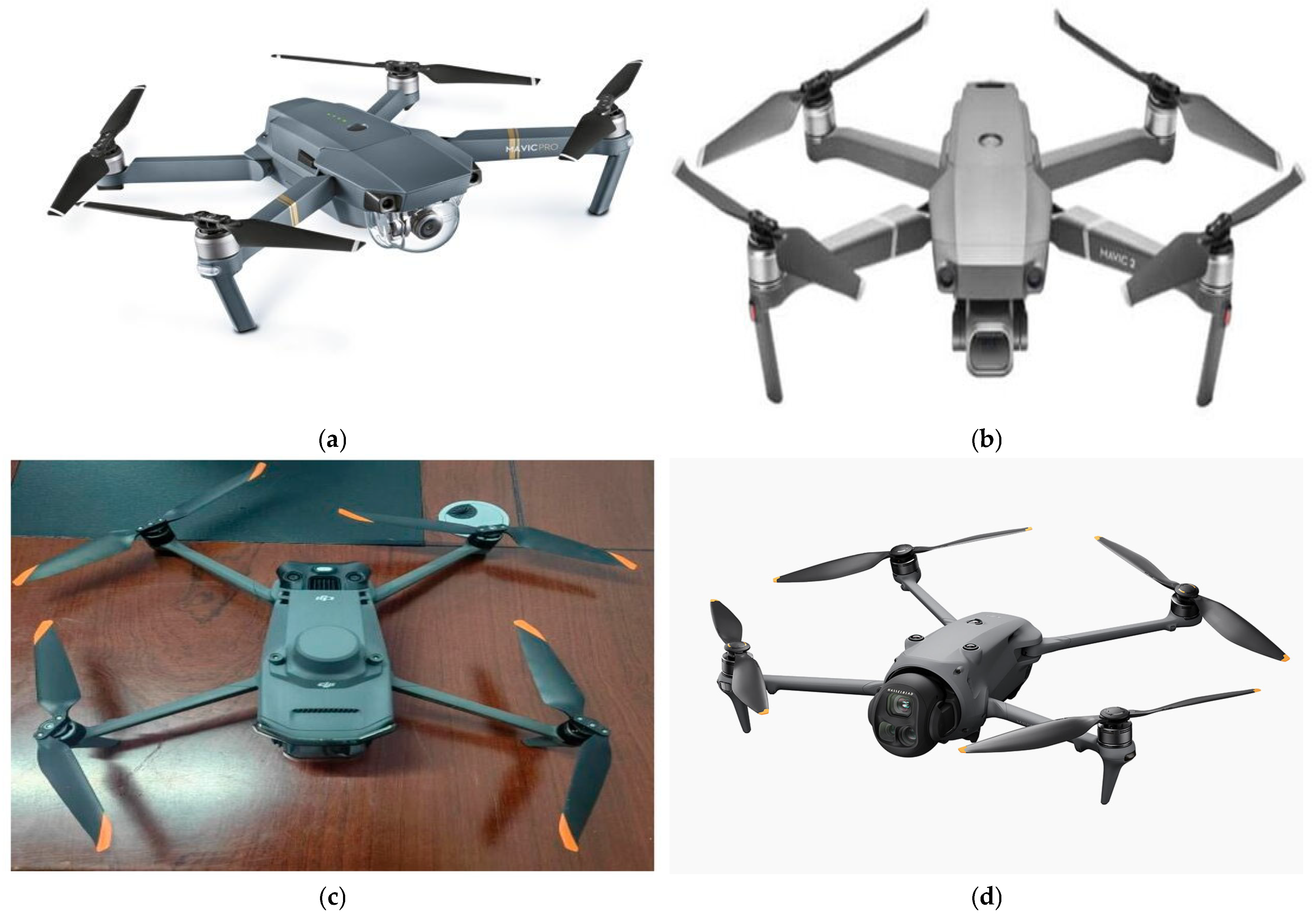

DJI released the Mavic Pro quadrotor in 2016. It features foldable arms for easy transport. The Mavic Pro is equipped with the same 12-megapixel camera as the Phantom 4. It has a 78-degree field of view, as opposed to the Phantom 4’s 94-degree field of view. Its top speed is 65 km/h, its range is 6.9 km, and it is powered by a 3830 mAh battery. It has a flight time of 27 min. The technical specifications of the DJI Mavic Pro quadrotor are given in

Table 31 [

145].

DJI released the Mavic 2 Pro in 2018. The Mavic 2 features 10 obstacle avoidance sensors. The battery capacity has been increased to 3850 mAh. The maximum flight time is 31 min. The Mavic 2 Pro features a 20-megapixel camera. The technical specifications of the DJI Mavic 2 Pro quadrotor are provided in

Table 32 [

146].

DJI released the Mavic 3 quadrotor in 2021. The Mavic 3 has a flight time of 46 min. It features both a wide-angle and a telephoto camera. The wide-angle camera is 20 MP, while the telephoto camera is 12 MP. It connects to a 4G mobile network and can be controlled from a range of up to 15 km. The technical specifications of the DJI Mavic 3 quadrotor are listed in

Table 33 [

147].

DJI released the Mavic 4 Pro in 2025. The Mavic 4 Pro has a 6654 mAh battery and a flight endurance of 51 min. It has three cameras: a variable-aperture 100 MP wide-angle camera capable of 6K video, a 1/1.3” CMOS telephoto camera, and a 1/1.5” CMOS medium telephoto camera. It features a more advanced obstacle avoidance system and satellite-independent return-to-home capability. It also features a 30 km HD video transmission capability. The Mavic 4 Pro’s technical specifications are listed in

Table 34 [

148].

Photos of the DJI Mavic Pro, Mavic 2 Pro, Mavic 3, and Mavic 4 Pro are given in

Figure 31.

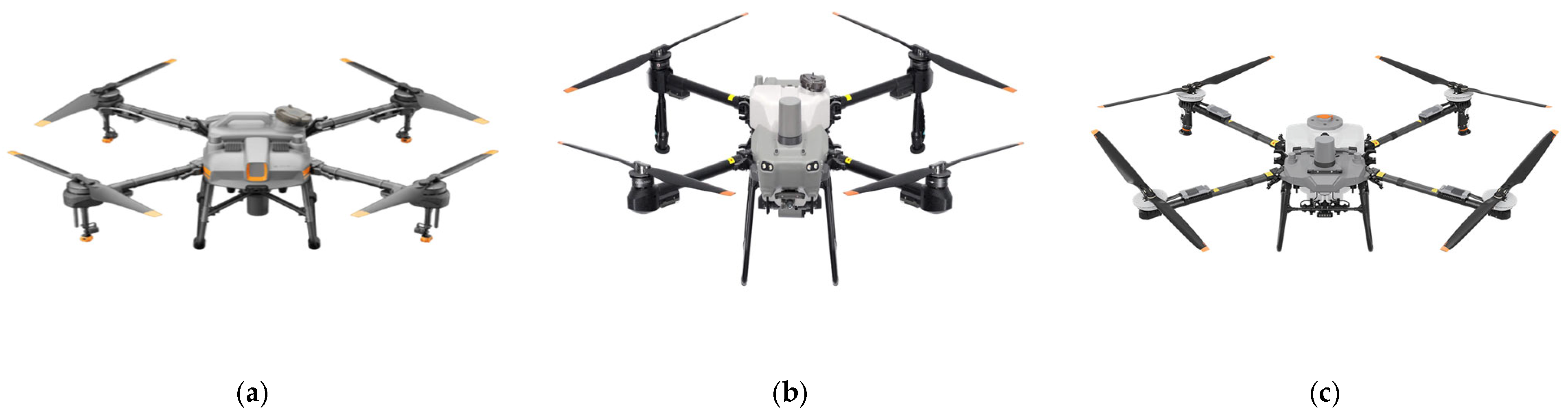

DJI has produced numerous quadrotor, hexarotor, and octorotor UAVs for use in agricultural spraying. In 2020, DJI launched the Agras T10 quadrotor model for agricultural spraying. The T10 features an 8 L tank, omnidirectional obstacle avoidance radar, dual cameras, and four nozzles. It has a 9500 mAh battery. The T10 has a hover time of 17 min with a takeoff weight of 16.8 kg. The technical specifications of the DJI Agras T10 quadrotor are given in

Table 35 [

153].

In 2022, DJI released the Agras T25 model. The Agras T25 can carry a spraying load of up to 20 kg or a spreading load of up to 25 kg. The Agras T25 features front and rear phased array radars, a binocular vision system, and a high-resolution FPV gimbal camera. It has a 15,500 mAh battery. The maximum diagonal wheelbase is 1925 mm. Internal battery operating time is 3 h and 18 min. External battery operating time is 2 h and 42 min. The technical specifications of the Agras T25 are given in

Table 36 [

154].

DJI produced the Agras T70P quadrotor in 2024. It has a 70 L spray tank and a flow rate of 40 L/min. It can carry a 70 kg spreading load and a flow rate of 400 kg/min. It also features obstacle avoidance capabilities. It can reach a maximum speed of 20 m/s and has a lift capacity of 65 kg. The technical specifications of the DJI Agras T70P are listed in

Table 37 [

155].

Photos of the DJI Agras T10, Agras T25, and Agras T70P are provided in

Figure 32.

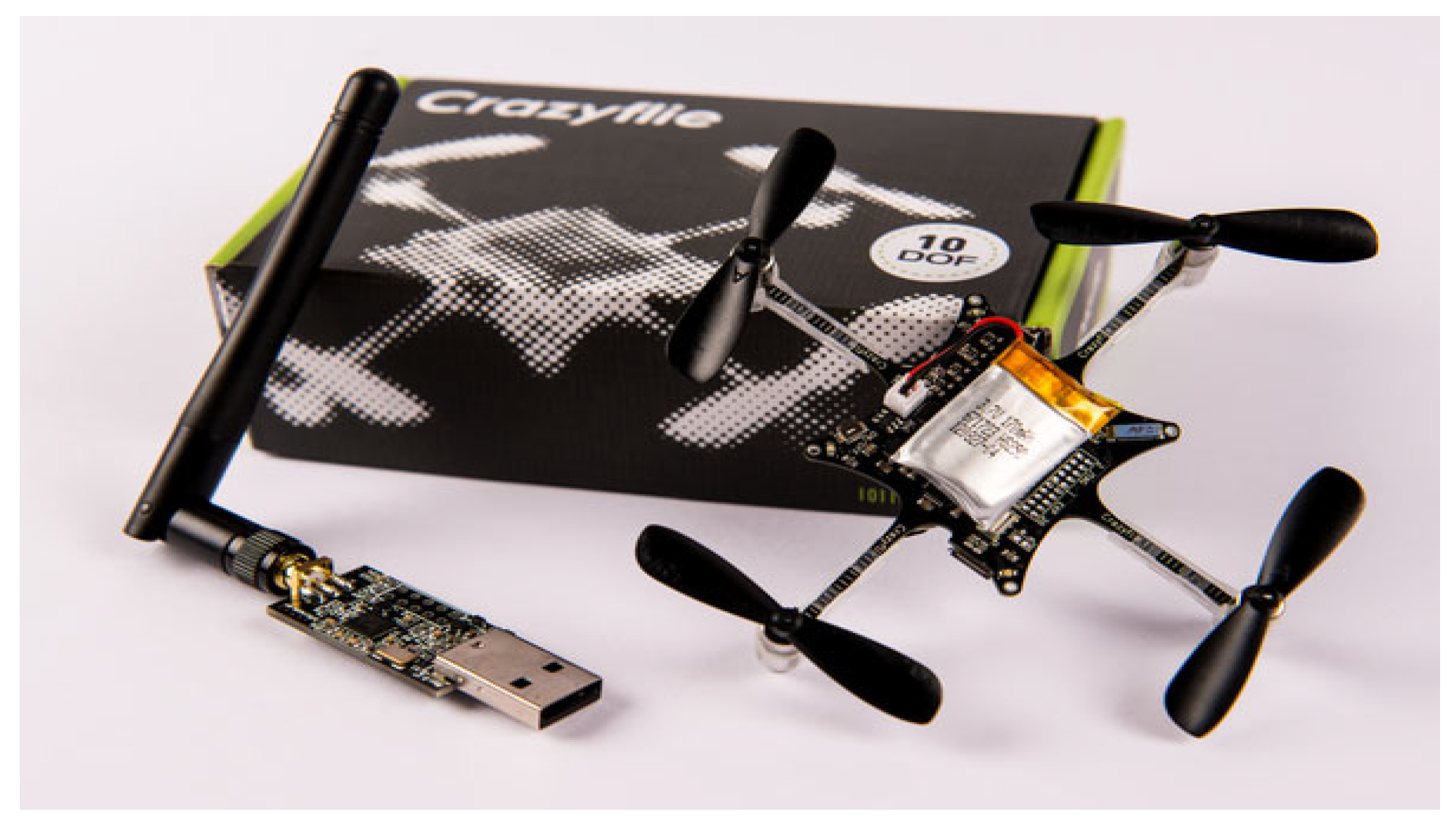

In 2013, the Swedish company Bitcraze produced the Crazyflie nano quadrotor. The Crazyflie is one of the smallest and lightest quadrotor UAVs. The Crazyflie nano-quadrotor established itself not as a commercial product, but as a crucial open-source research platform. Its small size, modularity, and programmability made it the standard for universities and research institutions worldwide for testing control strategies, obstacle avoidance, and pioneering swarm robotics algorithms. The technical specifications of the Crazyflie quadrotor are given in

Table 38 [

159]. A photograph of the Crazyflie quadrotor is shown in

Figure 33 [

160].

Bitcraze produced the Crazyflie 2.0 quadrotor in 2014. It weighs 27 g. It supports wireless control via radio and Bluetooth Low Energy. It has a flight time of 7 min and a charging time of 40 min. iOS and Android mobile apps have been developed for controlling the Crazyflie 2.0. A photo of the Crazyflie 2.0 is shown in

Figure 34. The technical specifications of the Crazyflie 2.0 are given in

Table 39 [

161].

Bitcraze released the Crazyflie 2.1 quadrotor in 2019. It offers improved radio performance and external antenna support. It features a more robust and break-resistant power button. A cable drain is used to prevent cables from weakening and breaking. The IMU and pressure sensor have been improved to improve flight performance. The Crazyflie 2.1 uses the BMI088 and BMP388 sensors, developed specifically for the drone by Bosch Sensortech. These sensors reduce drift [

162]. A picture of the Crazyflie 2.1 is shown in

Figure 35. The technical specifications of the Crazyflie 2.1 are shown in

Table 40 [

163].

Bitcraze released the Crazyflie 2.1+ quadrotor in 2024. The Crazyflie 2.1+ features an upgraded battery and propellers compared to the Crazyflie 2.1, and offers up to 15% improved flight performance. The Crazyflie 2.1+’s battery has been lightened by 1 g to improve flight performance while maintaining the same capacity. The technical specifications of the Crazyflie 2.1+ quadrotor are shown in

Table 41 [

164]. A photograph of the Crazyflie 2.1+ is shown in

Figure 36 [

165].

Bitcraze produced the Crazyflie 2.1 Brushless quadrotor in 2025. Thanks to its brushless motors, the Crazyflie 2.1 Brushless can lift heavier loads and achieve more powerful flights. A photo of the Crazyflie 2.1 Brushless quadrotor is shown in

Figure 37. The technical specifications of the Crazyflie 2.1 Brushless quadrotor are given in

Table 42 [

166].

Founded in 2009 in Berkeley, California, 3D Robotics (3DR) has produced quadrotors for aerial photography and mapping, and has developed the open-source ArduPilot autopilot software that can be used for quadrotors [

167]. Its Iris+ and Solo drones catered to hobbyists, researchers, and developers, promoting a vibrant community and accelerating innovation in autonomous flight algorithms. In 2014, 3D Robotics produced the IRIS+ quadrotor. The IRIS+ could take photos with a mounted GoPro camera. It could reach speeds of 64 km/h and had a range of 3280 ft (1 km). The technical specifications of the IRIS+ quadrotor are shown in

Table 43 [

168]. Iris+ was the first consumer drone capable of tracking its user. A photograph of the IRIS+ quadrotor is shown in

Figure 38 [

169].

3D Robotics produced the Solo Drone quadrotor in 2015. The Solo Drone was designed specifically for the GoPro Hero camera. It was developed to enable professional aerial photography and video capture during flight. Solo can be controlled from a smartphone, with the ability to take photos and record videos with the application installed on Android and iOS devices. The technical specifications of the Solo quadrotor are shown in

Table 44 [

170]. A photograph of the Solo quadrotor is shown in

Figure 39 [

171].

3D Robotics played a critical role in making drone technology more accessible through its open-source ArduPilot 4.6.3 software. ArduPilot enables flight control of multirotor drones, VTOL UAVs, fixed-wing UAVs, and RC helicopters [

172]. ArduPilot autopilot software works with the PID controller [

173]. The first version of ArduPilot was released in 2009 [

174]. Parrot company used ArduPilot autopilot software in its own quadrotors [

175]. In 2016, 3D Robotics left the ArduPilot development community due to a dispute over the licensing of the open-source code. The PX4 Development Team and Community began developing the other mainstream autopilot software, the PX4 autopilot v1.16.0 software, in 2009 [

176]. Like Ardupilot, the PX4 autopilot software was developed to work with a PID controller [

177]. In 2014, the PX4 autopilot development community, 3D Robotics, and the Ardupilot autopilot development community produced the Pixhawk flight controller hardware. The flight controller hardware standardized by Pixhawk is used in academic, professional, and hobbyist applications and is supported by two common autopilot firmware options: PX4 and ArduPilot [

178]. Today, advanced Pixhawk flight controllers contain two microcontrollers. The main flight management processor manages sensor readings, PID adjustments, and other resource-intensive computations. Another management processor handles input/output operations to external motors, switches, and radio control receivers. Onboard sensors include an IMU with a multi-axis accelerometer and gyroscope, a magnetometer, and a GPS unit [

179]. Crazyflie quadrotors use the Crazyflie Bolt flight card and PX4 autopilot software. The flight card and autopilot software used by Crazyflie operate using a PID controller [

180]. The Draganfly company uses the Cube Blue H7 flight control card, which is compatible with the PX4 autopilot software [

181]. Researchers have developed many different linear and nonlinear controllers for quadrotors through simulations and theoretical studies. However, existing flight cards and autopilot software in the industry are designed to work with PID controllers.

An examination of the technical specifications of quadrotor UAVs reveals that early quadrotor UAVs had 2S Li-Po batteries. Quadrotor UAVs produced in later years had 3S and 4S Li-Po batteries, respectively. This suggests that the number of cells in quadrotor UAV batteries has increased over time. Increasing the number of cells in Li-Po batteries allows the battery to produce more power. This allows quadrotors to move faster and maneuver more quickly. Throughout the historical development process, increasing the number of cells in the batteries of quadrotor UAVs has had a positive impact on their speed.

Table 45 shows the prominent features of quadrotor UAV models according to the period in which they were produced.

Table 46 summarizes the selected technical specifications of the quadrotor UAVs presented in this section. Weights, battery capacities, flight times and camera resolutions of Quadrotor UAVs are given.

The graph showing the weights of the quadrotor UAV models is shown in

Figure 40. The weights of quadrotor UAVs are in grams.

The graph of battery capacities for quadrotor UAV models is shown in

Figure 41.

Figure 42 shows the average flight time graph of quadrotor UAV models.

Figure 43 shows the graph of camera resolutions for quadrotor UAV models. Crazyflie quadrotors do not have cameras, so they are not included in the graph.

Figure 40 shows that the weight of quadrotor UAV models produced by quadrotor manufacturers has increased over time. Increasing battery weights, improved hardware, and larger sizes of quadrotor UAVs have led to increased weight.

Figure 41 shows that the battery capacity of each manufacturer’s models has increased over time. This is closely related to the increasing weight of quadrotors and their more advanced hardware. Since increasing weight and improved hardware lead to increased energy consumption, an increase in battery capacity is normal.

The flight duration graph in

Figure 42 shows that the flight duration of each manufacturer’s models has gradually increased over the years. The increased battery capacity of quadrotor UAVs has led to longer flight times. The increased flight duration of Draganfly’s quadrotor UAVs has facilitated search and rescue operations and allowed for the use of quadrotors for longer durations. An examination of DJI’s Agras T10, Agras T25, and Agras T70P quadrotors, produced for use in the agricultural sector, reveals increased flight duration over time. This increased flight duration allows for the spraying and fertilization of larger agricultural areas.

When the camera resolutions in

Figure 43 are examined, it is observed that the camera resolutions of Draganfly quadrotors have increased. Because Draganfly quadrotors are widely used in search and rescue and mapping missions, the increased camera resolution allows the quadrotors to perform their missions more successfully. Parrot quadrotors are widely used by NATO armies. Due to the high military standards, Parrot quadrotors have a higher camera resolution than most other quadrotors. The DJI Mavic 4 Pro, on the other hand, has the highest camera resolution at 100MP, making it easier to use in photogrammetry and 3D mapping. Because the DJI Phantom series quadrotors and 3D Robotics quadrotors use GoPro HERO cameras, the camera resolution is the same across their models. Because the DJI Agras series is designed for agricultural spraying and fertilizing, it does not require a higher camera resolution. Therefore, the DJI Agras series quadrotors feature a 12MP camera.

5. Future Directions

The first manned quadrotors produced exhibited poor flight performance and were destroyed in accidents. Although quadrotors produced for the US military in the 1950s achieved successful flights, they were not mass-produced due to budget cuts and failure to meet military standards. Quadrotor prototypes produced for lifting heavy loads in the 1980s also suffered accidents. Starting in the 2010s, quadrotors began to be used as air taxis. The Chinese company Ehang has successfully mass-produced its autonomous passenger quadrotors. It is anticipated that the use of manned quadrotors as air taxis will become more widespread in the future. Thanks to developing technology, manned quadrotors will be able to carry more passengers and have longer ranges. With the development of autopilot software, manned quadrotors used as air taxis will take passengers to their destinations without a pilot. The proliferation of quadrotors used as air taxis will lead to increased noise pollution. The increasing use of quadrotors as air taxis will require new safety measures, regulation of urban air traffic, the implementation of necessary legal regulations, and the necessary certification processes for flight.

Quadrotor UAVs have gained widespread use thanks to advanced battery, hardware, software, and sensor technologies. Advanced sensors (especially optical flow sensors) and gimbal technologies will enable quadrotor UAVs to transmit more stable video in the future. Advancing 4G and 5G technologies allow quadrotors to transmit video and photos from kilometers away. 6G and beyond technologies will further increase maximum transmission distances. In this way, communication will be possible with quadrotor UAVs at much longer distances, and data transfer will be possible faster and in larger sizes. Communication infrastructure is often damaged during natural disasters. In the future, mobile base stations installed on quadrotor UAVs will be used to ensure rapid communication in natural disaster scenarios.

Developing lithium-ion battery technologies has extended the flight endurance of quadrotor UAVs. In the future, thanks to advancements in hydrogen fuel cell technologies, hydrogen fuel cell-powered quadrotor UAVs will be able to fly longer distances and lift heavier payloads than Li-ion battery-powered quadrotors. In the future, quadrotor UAVs are expected to be used in search and rescue operations at longer distances and with longer flight times. Developing thermal camera technologies facilitates search and rescue operations by detecting the body temperatures of searched individuals. Furthermore, thanks to the development of machine learning technologies, identifying and tracking wanted people and objects will become easier.

Quadrotor UAVs are increasingly being used in the agricultural sector. Thanks to developing artificial intelligence technologies, quadrotor UAVs will create optimal routes to spray and fertilize farmers’ fields. Machine learning technologies can detect pests on plant leaves and fruits. With the use of this technology, quadrotor UAVs used in the agricultural sector will be able to directly target pests on leaves and fruit, using fewer pesticides.

An increase in the number of cargo-carrying quadrotor UAVs is expected in the future. There will also be an increase in the number of quadrotor UAVs transporting organs between hospitals. It is also anticipated that quadrotor UAVs carrying first aid kits will be increasingly used in emergency response.

Autonomous drone swarms that can communicate with each other will facilitate coordinated search-and-rescue operations by scanning large areas. Autonomous drone swarms will facilitate coordinated transportation and coordinated pesticide spraying of agricultural areas. Advances in artificial intelligence, IoT, and edge computing will facilitate real-time on-site data processing and decentralized operation of quadrotors.

GPS signals can be weak or absent indoors, underground, and in urban canyons. In such cases, traditional GPS-based path planning methods are inapplicable. In the future, path planning will be based on real-time position information using a combination of inertial navigation systems (INSs) and visual simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM). This will enable quadrotor UAVs to perform their missions without relying on GPS.

The rapid increase in the number of quadrotor UAVs could lead to cybersecurity and privacy issues. To prevent this, new laws and stricter oversight will be necessary in the future. Many countries have enacted laws prohibiting the flight of quadrotor UAVs over important public buildings and military bases. New laws are expected to be enacted in the future to restrict the flight of quadrotor UAVs to protect the privacy and security of private property belonging to citizens. The increasing number of quadrotor UAVs necessitates certification processes for their use. Quadrotor UAVs will be classified according to their size and intended use, and separate UAV pilot training will be provided for each class. This will ensure that both UAV pilots and the UAVs they operate are registered and potential security issues will be prevented.

6. Conclusions

This review article examines the developmental stages of quadrotors from the past to the present. Quadrotors are examined in two categories: manned quadrotors and quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicles. First, the developmental processes of manned quadrotors are described. The production process, technical specifications, photographs, and historical development of manned quadrotors are presented. In addition, the weight, powerplant, flight duration and passenger capacity data of manned quadrotor models were compiled into a table, and graphs were drawn based on this table. The first quadrotors produced can be characterized by poor stability, difficulty in control, short range, low speed, and limited altitude. Quadrotors produced for use by the US military in the 1950s yielded more successful results. However, their production was discontinued due to budget constraints and failure to meet military standards. Manned quadrotor prototypes produced for heavy-lifting in the 1980s were unsuccessful. The use of quadrotors as air taxis began in the 2010s. Manned quadrotors used for air taxis have achieved successful flights, and some have entered mass production. Furthermore, starting with the Ehanag 184, fossil fuel-powered quadrotors have been phased out and replaced by electric motors. The Ehang 184 manned quadrotor was the first air taxi to enter mass production.

The second stage describes the historical development, technical specifications, and areas of application of quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicles. Mass-produced and widely used quadrotor UAV models are discussed in detail. Graphs for the weight, battery capacity, flight duration, and camera resolution of the quadrotor UAV models are presented. Quadrotor UAVs began production in the late 1990s. The first quadrotor UAVs were used for hobby purposes. Later, these quadrotor UAVs, thanks to the addition of cameras, began to be used for photography and video recording. Technological advancements have led to the widespread use of quadrotor UAVs. Advances in battery technology allow for longer flights for all types of quadrotor UAVs. Advances in camera technology allow quadrotor UAVs to be used in various fields such as reconnaissance, surveillance, scientific research, wildlife monitoring, search and rescue, mapping, aerial photography and mineral exploration.

Increased battery capacities have enabled quadrotor UAVs, used in search and rescue and mapping, to operate for longer periods.

Figure 42 demonstrates the increasing flight durations of quadrotor UAVs produced by Draganfly, Parrot, and DJI. The increasing camera resolution of quadrotor UAVs has enabled them to capture higher-quality images and perform search and rescue and mapping missions more successfully. Furthermore, advances in thermal camera technology have enabled quadrotor UAVs to locate sought-after creatures by detecting their body heat. Thanks to the development of 4G and 5G technologies, quadrotors can transmit images and videos from several kilometers away. Analyzing the tables presented in this article reveals that the range and transmission distance of quadrotor UAVs have increased. These advancements have facilitated the use of quadrotors in search and rescue operations, reconnaissance and surveillance, and mapping.

Advances in sensor and software technologies have enabled quadrotor UAVs to avoid obstacles, fly in flocks, and perform aggressive maneuvers. The capabilities of the Crazyflie series quadrotors, produced by Bitcraze and widely used by researchers, are examples of this development.

Advances in sensor and hardware technologies have increased the stable payload-carrying capacity of quadrotors. They also enable them to perform assigned missions by avoiding obstacles and following optimal trajectories. Today, many loads, such as first aid supplies and cargo, are transported stably by quadrotors. Agricultural spraying quadrotors can spray agricultural crops by calculating optimal trajectories and avoiding obstacles. The Agras series quadrotors produced by DJI have reached the capacity to carry increasing amounts of pesticides and fertilizers. The increased payload capacity of these quadrotors is clearly evident from the data obtained in the tables. The increased battery capacity of these quadrotors makes spraying large agricultural areas easier. Thanks to advanced sensor and camera technologies, they can perform spraying and fertilizing tasks by creating optimal routes and avoiding obstacles.

The Ardupilot and PX4 autopilot software used by quadrotor UAVs, as well as the Pixhawk flight cards, has been developed to work fully with PID controllers. While researchers have conducted theoretical studies and simulations on different controller designs, as discussed in this study, current quadrotor UAVs operate with PID controllers.

To sum up, this review article provided a detailed overview of the major manned quadrotors and quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicles produced from the early 1900s to the present. Their production stages, technical specifications, and areas of use were described, providing a comprehensive perspective for researchers focusing on this topic.