Multi-Object Tracking with Distributed Drones’ RGB Cameras Considering Object Localization Uncertainty

Highlights

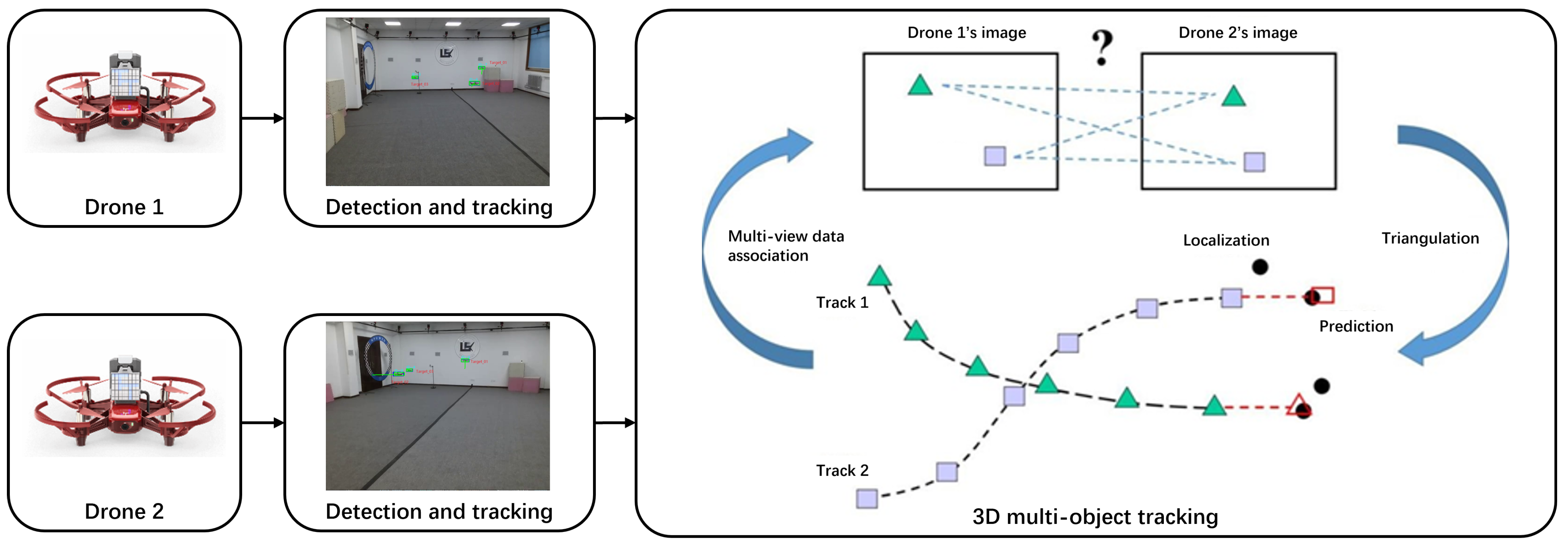

- A comprehensive passive sensing framework for multi-object tracking with distributed drones is presented. The robust localization and tracking of aerial objects can be achieved by exploiting spatio-temporal information to associate targets detected by different views.

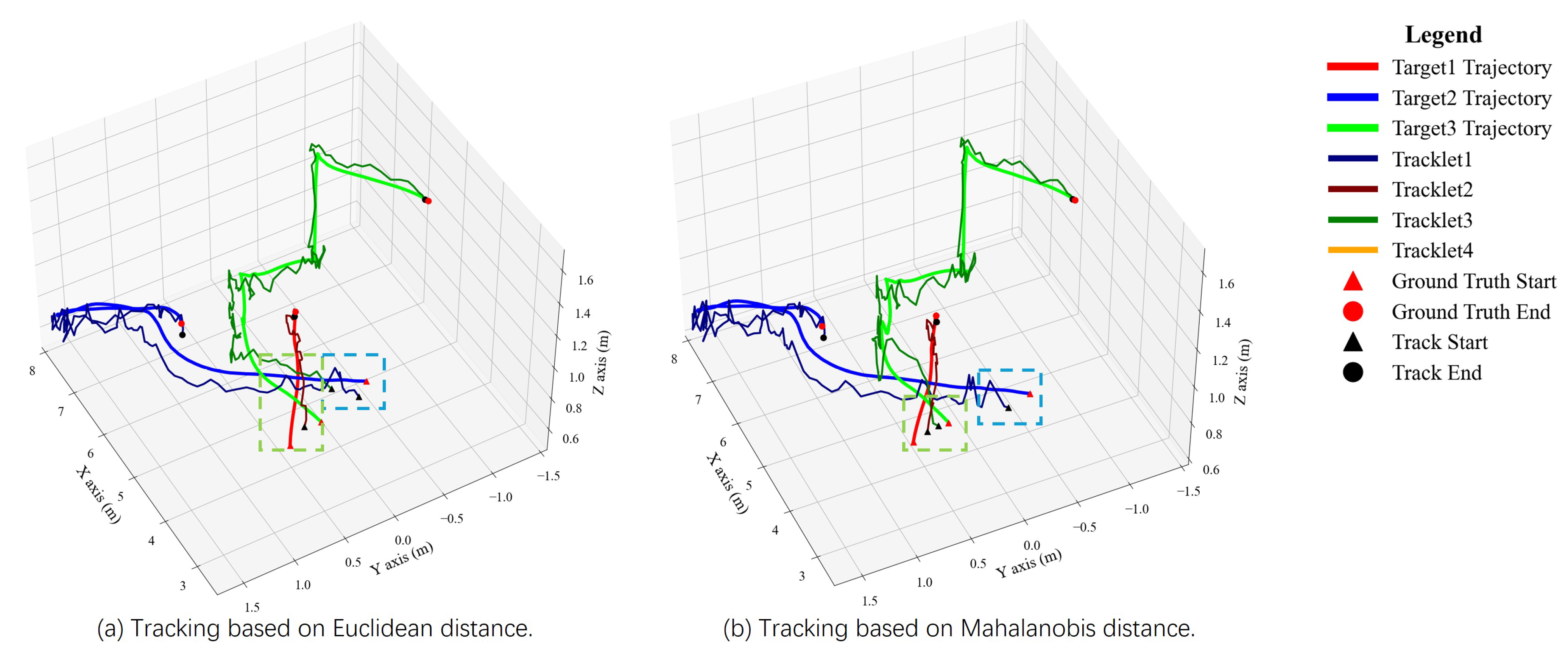

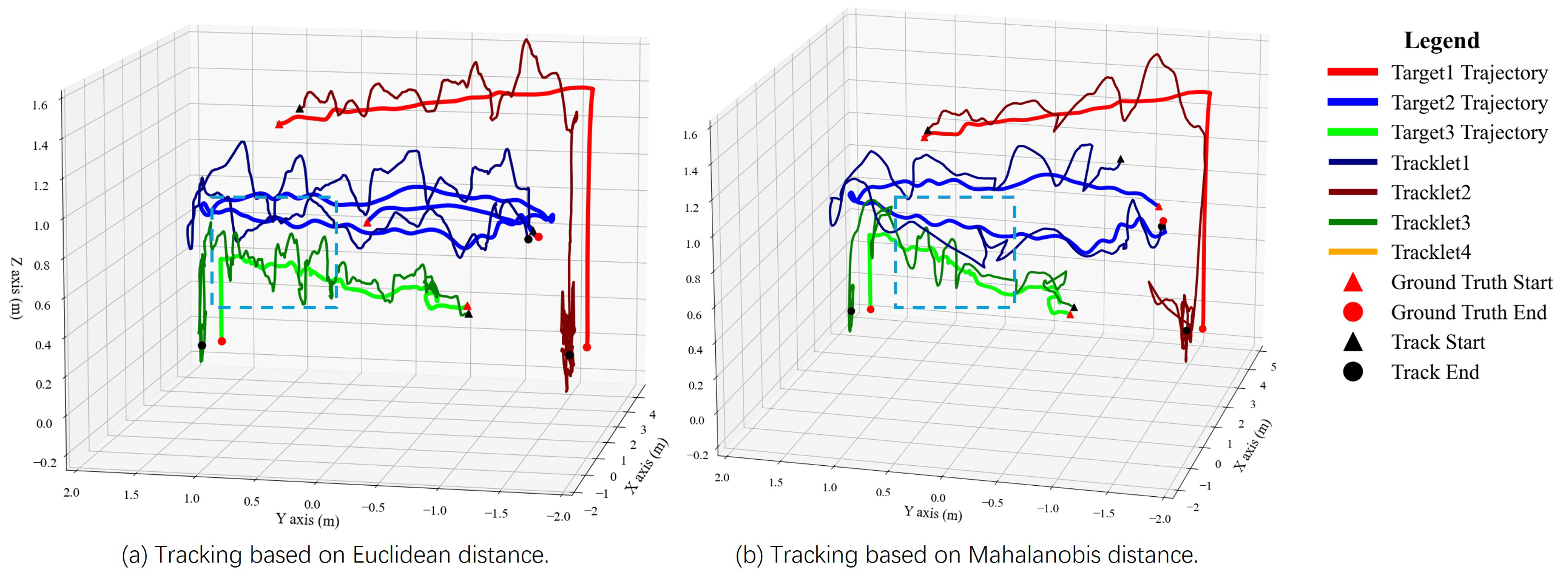

- Object localization uncertainty is modeled in the Kalman filter through carefully designed process and observation noise covariance matrices. The resulting data association, based on the Mahalanobis distance, enhances the performance of multi-object tracking.

- Since aerial objects are always small and share similar appearance features, data association between different viewpoints of passive sensors needs to consider more about the geometric constraints and temporal information.

- The motion of the observer drone necessitates refined modeling of process and observation noise to achieve robust object tracking.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- •

- A comprehensive passive sensing framework for multi-object tracking with distributed drones is presented. By exploiting spatio-temporal information to associate targets detected by different views, the proposed method achieves robust localization and tracking of aerial objects.

- •

- Object localization uncertainty is modeled in the Kalman filter through carefully designed process and observation noise covariance matrices. The resulting data association, based on the Mahalanobis distance, enhances the performance of multi-object tracking.

- •

- The effectiveness of the proposed approach is verified through both simulation and real-world experiments. To benefit the robotics community, the collected dataset will be released at https://github.com/npu-ius-lab/mdmot_bench, accessed on 31 December 2025.

2. Related Work

2.1. Multi-View Data Association

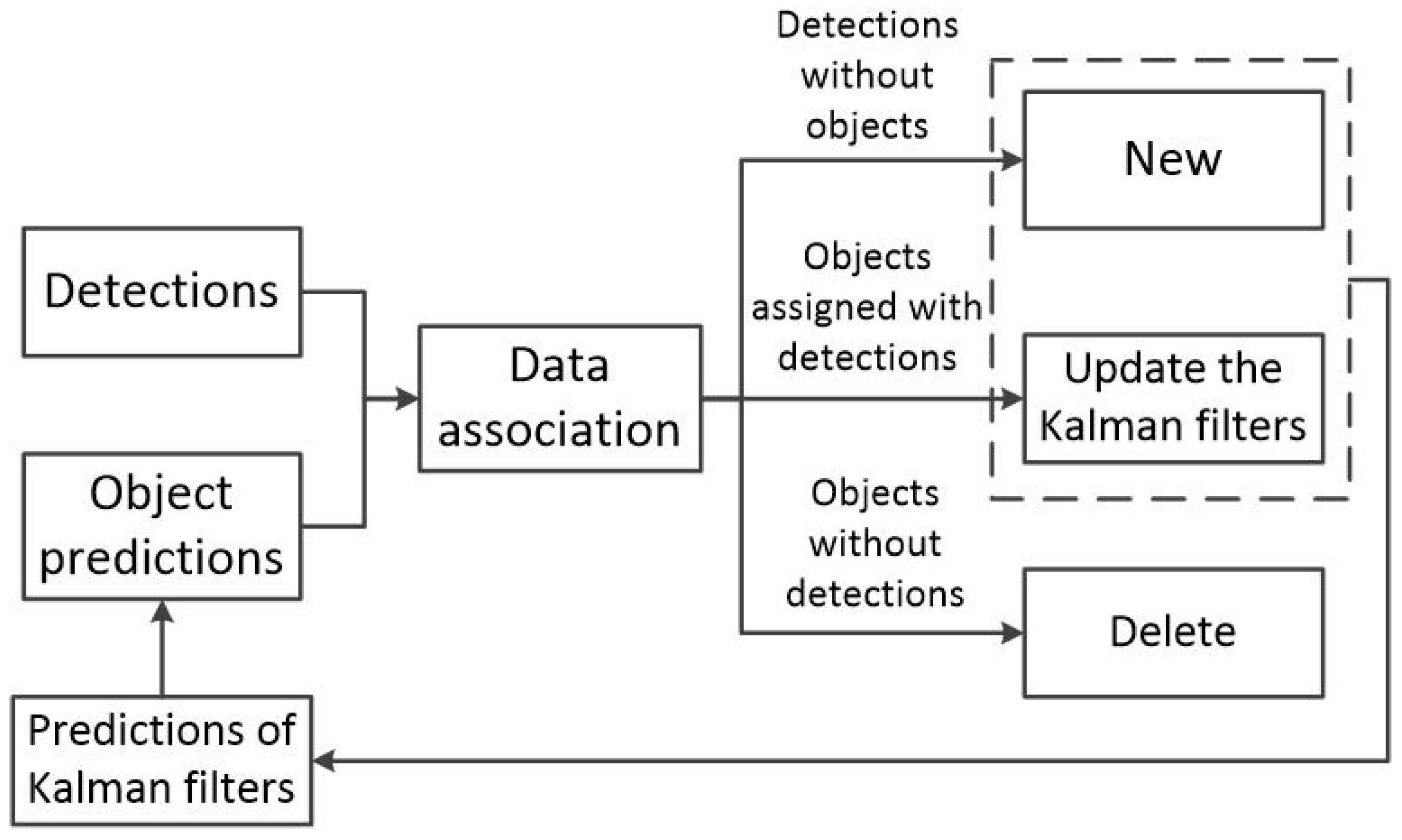

2.2. Multi-Target Tracking

3. Problem Formalization

3.1. Multi-View Data Association

3.2. Multi-Object Tracking

4. Proposed Method

4.1. 2D Multi-Object Tracking

4.2. Multi-View Data Association

4.3. 3D Multi-Object Tracking

- A trajectory is terminated if it remains unmatched for more than frames (set to 30).

- A new trajectory is initialized only if a newly observed point is matched successfully for more than frames (set to 4). Otherwise, it is considered a false alarm and discarded.

5. Experiments

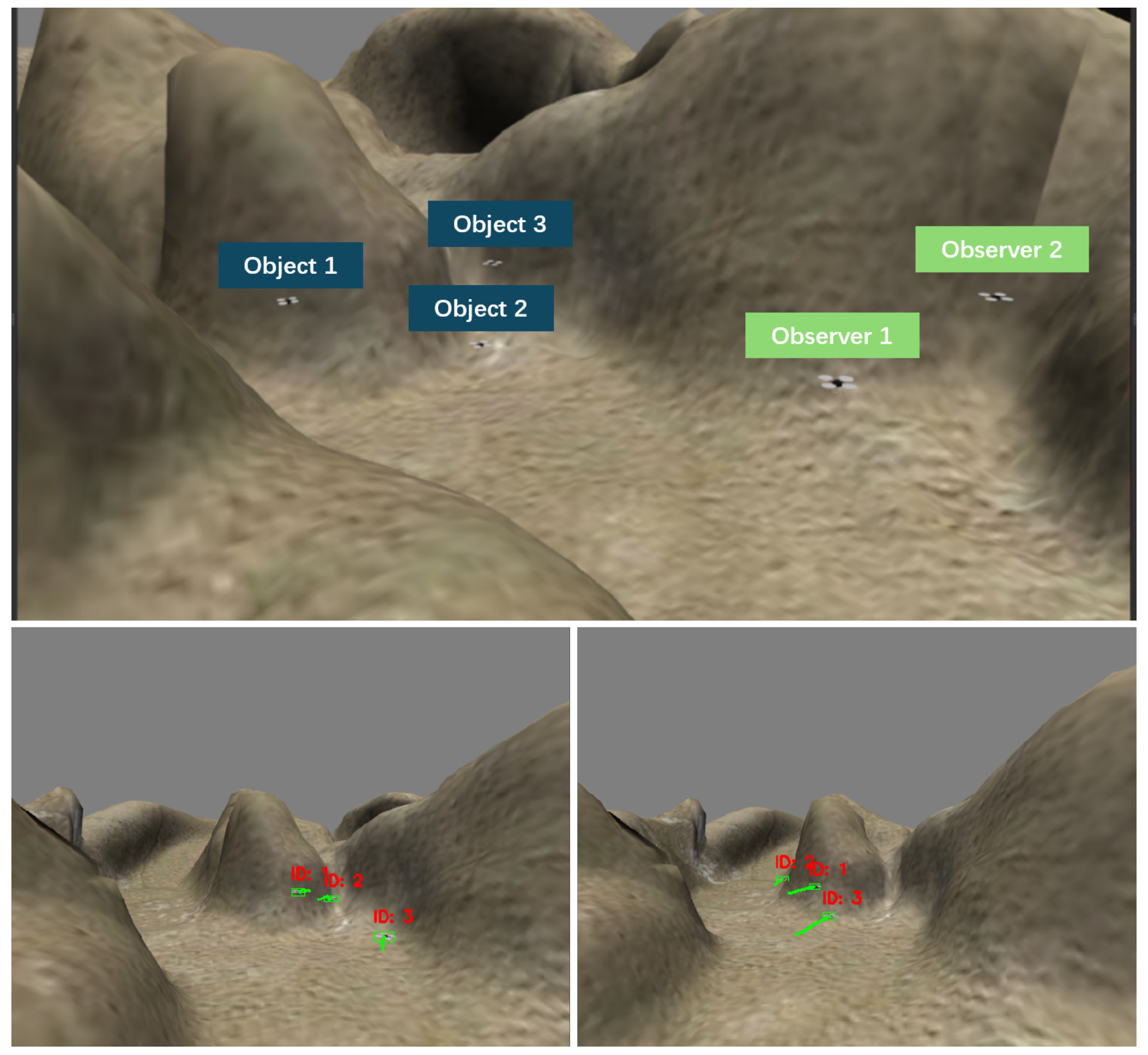

5.1. Experimental Settings

- HOTA provides a comprehensive assessment of algorithm performance by jointly measuring detection accuracy, data association quality, and localization precision, thereby balancing the algorithm’s effectiveness across multiple dimensions.

- IDF1 evaluates the tracker’s ability to handle fragmented trajectories and reflects its stability in dealing with target loss and re-identification.

- MOTA offers an overall assessment of both trajectory continuity and detector performance by quantifying the algorithm’s tracking effectiveness in terms of False Positives (FP), False Negatives (FN), and IDentity switches (IDsw). Specifically, FP denotes the number of times false alarms are incorrectly tracked as real targets, FN represents the number of true targets that are missed, and IDsw counts the occurrences of target identity changes during tracking.

5.2. Experimental Results

5.2.1. Simulation Results

5.2.2. Real-World Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOA | Angle Of Arrival |

| MOT | Multi-Object Tracking |

| KF | Kalman Filter |

| CV | Constant Velocity |

References

- Amosa, T.I.; Sebastian, P.; Izhar, L.I.; Ibrahim, O.; Ayinla, L.S.; Bahashwan, A.A.; Bala, A.; Samaila, Y.A. Multi-camera multi-object tracking: A review of current trends and future advances. Neurocomputing 2023, 552, 126558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, K.; Luo, K.; Luo, X.; Huang, J.; Wu, H.; Hu, R.; Hao, W. Ucmctrack: Multi-object tracking with uniform camera motion compensation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–27 February 2024; Volume 38, pp. 6702–6710. [Google Scholar]

- Gunia, M.; Zinke, A.; Joram, N.; Ellinger, F. Analysis and design of a MuSiC-based angle of arrival positioning system. ACM Trans. Sens. Netw. 2023, 19, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, S. Passive TDOA location algorithm for eliminating location ambiguity. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 2005, 31, 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Wang, X.; Zheng, Z.; Peng, H. Formation maintenance strategy for USV fleets based on passive localization under communication constraints. Ocean Eng. 2025, 340, 122306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oualil, Y.; Faubel, F.; Klakow, D. A fast cumulative steered response power for multiple speaker detection and localization. In Proceedings of the 21st European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO 2013), Marrakech, Morocco, 9–13 September 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Liu, N.; Wang, G.; Qi, L.; Dong, Y. Robust track-to-track association algorithm based on t-distribution mixture model. In Proceedings of the 2017 20th International Conference on Information Fusion (Fusion), Xi’an, China, 10–13 July 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Flood, G.; Elvander, F. Multi-source localization and data association for time-difference of arrival measurements. In Proceedings of the 2024 32nd European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), Lyon, France, 26–30 August 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Fang, B.; Fu, W.; Yang, T. Multi-drone Multi-object Tracking with RGB Cameras Using Spatio-Temporal Cues. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Autonomous Unmanned Systems, Nanjing, China, 8–11 September 2023; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 412–421. [Google Scholar]

- Bewley, A.; Ge, Z.; Ott, L.; Ramos, F.; Upcroft, B. Simple online and realtime tracking. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 25–28 September 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 3464–3468. [Google Scholar]

- Wojke, N.; Bewley, A.; Paulus, D. Simple online and realtime tracking with a deep association metric. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Beijing, China, 17–20 September 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 3645–3649. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, P.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, D.; Weng, F.; Yuan, Z.; Luo, P.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. Bytetrack: Multi-object tracking by associating every detection box. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.; Pang, J.; Weng, X.; Khirodkar, R.; Kitani, K. Observation-centric sort: Rethinking sort for robust multi-object tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 9686–9696. [Google Scholar]

- Aharon, N.; Orfaig, R.; Bobrovsky, B.Z. BoT-SORT: Robust associations multi-pedestrian tracking. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.14651. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Han, G.; Yan, B.; Zhang, W.; Qi, J.; Lu, H.; Wang, D. Hybrid-sort: Weak cues matter for online multi-object tracking. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–27 February 2024; Volume 38, pp. 6504–6512. [Google Scholar]

- Pöschmann, J.; Pfeifer, T.; Protzel, P. Factor graph based 3d multi-object tracking in point clouds. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 25–29 October 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 10343–10350. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Guo, L.; Huang, X. Research and application of multi-target tracking based on GM-PHD filter. Opt. Photonics J. 2020, 10, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, T.; Zhou, X.; Krahenbuhl, P. Center-based 3d object detection and tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 11784–11793. [Google Scholar]

- Varghese, R.; Sambath, M. Yolov8: A novel object detection algorithm with enhanced performance and robustness. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Advances in Data Engineering and Intelligent Computing Systems (ADICS), Chennai, India, 18–19 April 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Luiten, J.; Osep, A.; Dendorfer, P.; Torr, P.; Geiger, A.; Leal-Taixé, L.; Leibe, B. Hota: A higher order metric for evaluating multi-object tracking. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2021, 129, 548–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ristani, E.; Solera, F.; Zou, R.; Cucchiara, R.; Tomasi, C. Performance measures and a data set for multi-target, multi-camera tracking. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardin, K.; Stiefelhagen, R. Evaluating multiple object tracking performance: The clear mot metrics. EURASIP J. Image Video Process. 2008, 2008, 246309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Olson, E. AprilTag 2: Efficient and robust fiducial detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 9–14 October 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 4193–4198. [Google Scholar]

| MOTA ↑ | IDF1 ↑ | HOTA ↑ | FP ↓ | FN ↓ | IDsw ↓ | AssA ↑ | DetA ↑ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static observation conditions. | ||||||||

| Baseline [9] | 80.7 | 70.3 | 70.0 | 161 | 109 | 0 | 62.5 | 78.5 |

| Ours-Q | 99.7 | 97.9 | 81.7 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 82.2 | 81.5 |

| Ours-R | 96.4 | 96.3 | 81.2 | 45 | 3 | 1 | 82.0 | 80.5 |

| Ours | 99.6 | 97.8 | 89.3 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 87.9 | 90.6 |

| Dynamic observation conditions. | ||||||||

| Baseline [9] | 79.6 | 59.6 | 55.5 | 166 | 132 | 0 | 41.0 | 75.2 |

| Ours-Q | 99.0 | 97.5 | 80.9 | 0 | 14 | 1 | 79.8 | 82.0 |

| Ours-R | 56.6 | 66.4 | 58.4 | 619 | 17 | 4 | 58.6 | 58.3 |

| Ours | 99.0 | 97.5 | 82.0 | 0 | 14 | 1 | 80.6 | 83.4 |

| MOTA ↑ | IDF1 ↑ | HOTA ↑ | FP ↓ | FN ↓ | IDsw ↓ | AssA ↑ | DetA ↑ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static observation conditions. | ||||||||

| Baseline [9] | 60.4 | 77.2 | 58.5 | 31 | 152 | 0 | 63.6 | 53.9 |

| Ours-Q | 53.9 | 62.6 | 47.2 | 63 | 144 | 6 | 47.3 | 47.3 |

| Ours-R | 0.4 | 54.9 | 40.6 | 324 | 130 | 6 | 48.4 | 34 |

| Ours | 66.9 | 81.0 | 62.6 | 17 | 136 | 0 | 68.1 | 57.5 |

| Dynamic observation conditions. | ||||||||

| Baseline [9] | 91.3 | 95.7 | 72.8 | 94 | 32 | 0 | 74.5 | 71.1 |

| Ours-Q | 50.9 | 74.7 | 57.3 | 409 | 312 | 3 | 52.8 | 62.3 |

| Ours-R | 37.7 | 38 | 34.8 | 612 | 292 | 16 | 45.7 | 26.6 |

| Ours | 90.9 | 94 | 70.4 | 17 | 144 | 0 | 71.7 | 69.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liao, X.; Fang, B.; Shao, W.; Fu, W.; Yang, T. Multi-Object Tracking with Distributed Drones’ RGB Cameras Considering Object Localization Uncertainty. Drones 2025, 9, 867. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120867

Liao X, Fang B, Shao W, Fu W, Yang T. Multi-Object Tracking with Distributed Drones’ RGB Cameras Considering Object Localization Uncertainty. Drones. 2025; 9(12):867. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120867

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiao, Xin, Bohui Fang, Weiyu Shao, Wenxing Fu, and Tao Yang. 2025. "Multi-Object Tracking with Distributed Drones’ RGB Cameras Considering Object Localization Uncertainty" Drones 9, no. 12: 867. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120867

APA StyleLiao, X., Fang, B., Shao, W., Fu, W., & Yang, T. (2025). Multi-Object Tracking with Distributed Drones’ RGB Cameras Considering Object Localization Uncertainty. Drones, 9(12), 867. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120867