1. Introduction

In mineral exploration, lithology identification and mapping play an essential and irreplaceable role. At present, data collection still relies heavily on manual field surveys. However, in high-altitude prospecting regions characterized by complex terrain and harsh environmental conditions, such surveys encounter considerable challenges, greatly limiting the depth of geological investigation and the efficiency of mineral exploration.

Remote sensing technology, with its unique capability to capture spatial information, offers a promising solution to these obstacles. Early lithology identification efforts relied primarily on satellite imagery [

1], which proved effective on a macro scale. Nevertheless, its relatively low spatial resolution hampers the accurate depiction of fine-scale geological features [

2]. In recent years, the rapid advancement of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology has brought revolutionary changes to geological mapping. Compared with traditional ground surveys or satellite remote sensing, UAVs provide notable advantages—low cost, convenience, and high flexibility—and have been widely applied in diverse fields [

3,

4,

5]. Operating efficiently even in high-altitude and inaccessible areas, UAVs equipped with visible, multispectral, or hyperspectral cameras can capture centimeter-level low-altitude imagery. Such imagery enables precise characterization of lithological details and facilitates the extraction of small-scale geological structures [

6]. Integrating UAV-acquired high-resolution remote sensing images with image classification methods thus allows for reliable lithological discrimination and a comprehensive understanding of mapping areas, overcoming the inherent constraints of manual surveys.

Early lithology extraction from imagery depended largely on manual classification [

7], which is time-consuming, reliant on expert knowledge, and prone to misclassification due to suboptimal feature selection. The emergence of computer-based approaches introduced traditional machine learning algorithms—such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs) and Random Forests (RFs) [

8,

9,

10,

11]—for lithology identification. However, these methods rely on manually engineered features and struggle to handle the complexity of field outcrop scenes.

Recent developments in deep learning, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), have enabled automatic feature extraction without manual intervention, markedly improving classification accuracy and efficiency [

12]. From early shallow architectures such as AlexNet and VGGNet to deeper networks including ResNet and Inception [

13,

14,

15], CNNs have shown strong performance in image classification, object detection, and semantic segmentation. Applied in lithology mapping, Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs) have improved category accuracy [

16], while U-Net has achieved higher segmentation precision in land-cover mapping [

17]. Yet, limitations remain—such as reduced receptive field, blurred boundaries, and high computational costs. The DeepLab series, particularly DeepLabV3+, offers high segmentation accuracy [

18] but still demands considerable computational and memory resources.

Lightweight network architectures, such as MobileNetV2, have been developed to address the high computational demands of processing high-resolution remote sensing imagery. MobileNetV2 utilizes inverted residual blocks and depthwise separable convolutions to reduce parameter count and computational complexity while maintaining strong representational power [

19]. Furthermore, to enhance feature extraction efficiency, attention mechanisms have gained prominence. Among these, the Coordinate Attention (CA) mechanism is particularly notable for its ability to effectively capture spatial and channel-wise relationships by encoding precise positional information into channel attention, which has been shown to improve model performance across various computer vision tasks, including agricultural pest detection, microstructure analysis [

20,

21].

Despite these advances, most lithology identification models are still trained on satellite imagery and rarely on high-resolution UAV oblique photogrammetry data. Even when UAV data are used, complex high-altitude geological environments can pose persistent challenges, such as blurred boundaries, high intraclass texture similarity, class imbalance, and heavy computational costs when applying conventional CNN architectures.

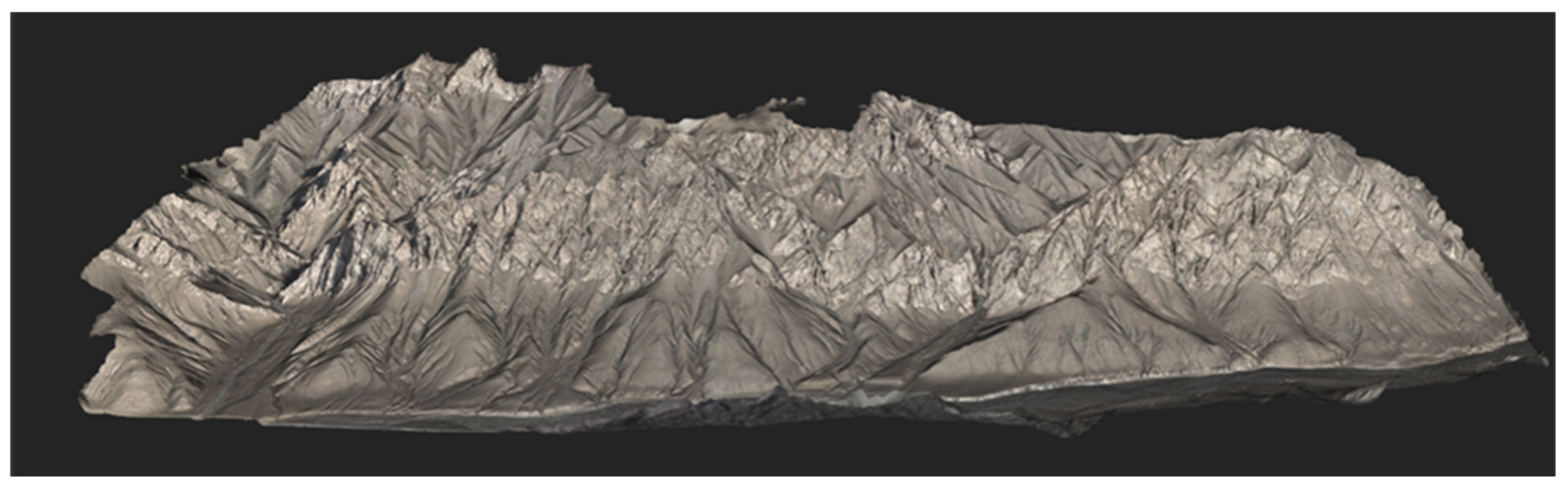

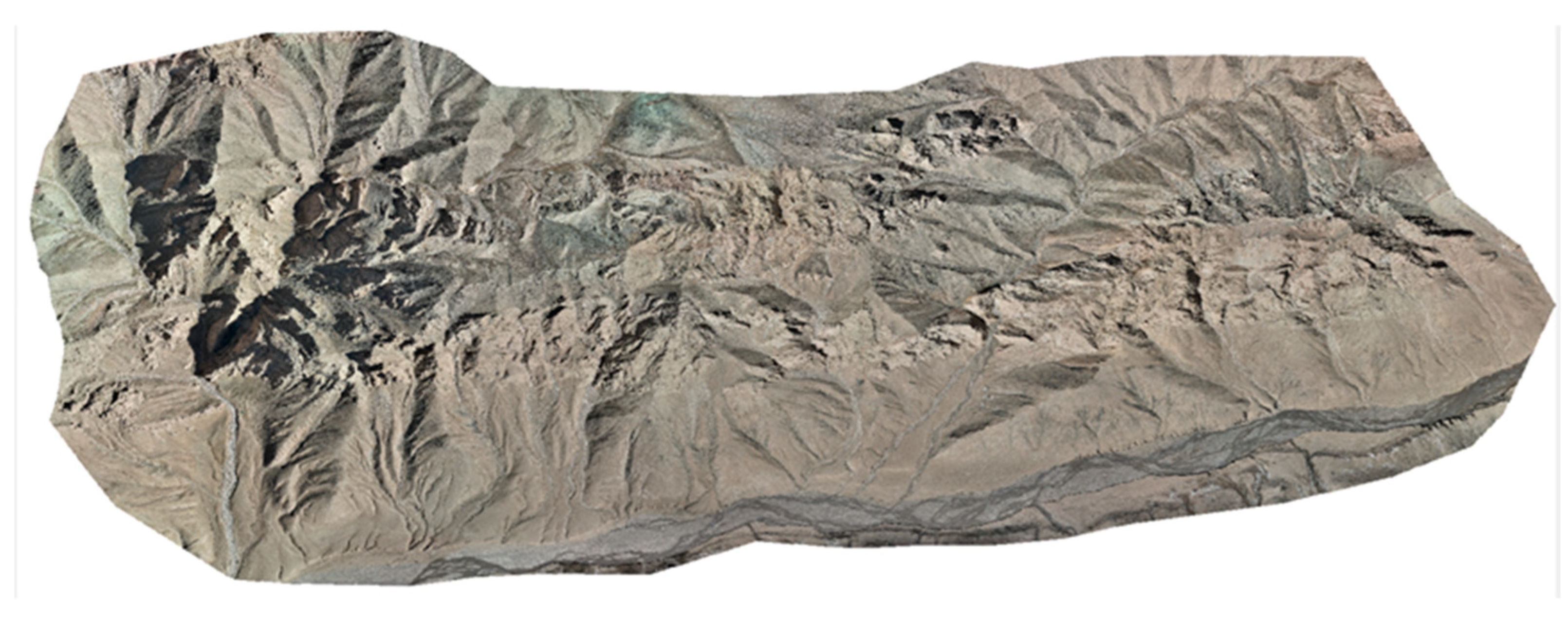

To address these challenges, this study focuses on the Ququleke Mountain region in Qiemo County, Xinjiang, China. A high-resolution orthophoto dataset was constructed using UAV oblique photogrammetry. Building upon the DeepLabV3+ semantic segmentation framework, a Coordinate Attention (CA) mechanism together with a multi-scale feature fusion module was integrated to enhance the extraction of multi-scale information and spatial context. While the CA-DeepLabV3+ framework has demonstrated effectiveness in various remote sensing and computer vision applications, such as impervious surface extraction [

22] and SAR image semantic segmentation [

23], its integration with UAV oblique photogrammetry for lithological mapping represents a pioneering application in a geological context. In addition, a lightweight MobileNetV2 backbone was employed and transfer learning was applied to reduce computational complexity. Comparative experiments against FPN, FCN, U-Net, PSPNet, DeepLabV1, and the standard DeepLabV3+ [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29] were conducted to validate the accuracy and portability of this novel methodology, offering an efficient approach for lithological mapping in complex regions.

3. Experiment and Methods

3.1. Overview of the Proposed Lithology Segmentation Method

To rigorously evaluate the performance and adaptability of the proposed UAV orthophoto-based lithology identification approach, a step-by-step experimental workflow was implemented.

First, high-resolution RGB orthophotos of the Ququleke study area were obtained via UAV oblique photogrammetry. Raw images underwent geometric correction to remove distortions due to flight tilt and terrain relief, followed by color normalization to standardize brightness and contrast across different acquisition sessions. The imagery was then tiled into fixed-size 256 × 256-pixel patches, a format compatible with deep convolutional networks. Combined with precise manual annotation, a lithology semantic segmentation dataset was constructed.

For the semantic segmentation task, DeepLabV3+ was adopted as the baseline model from which modifications were applied. Its original heavy backbone (such as Xception or ResNet) was replaced by the lightweight MobileNetV2 to reduce parameter count and computational complexity—essential for running on limited GPU memory. MobileNetV2 incorporates inverted residual blocks and depthwise separable convolutions, drastically lowering computational cost while maintaining strong representational power.

Transfer learning was employed: initial weights were pre-trained on large-scale image datasets, allowing the model to converge faster and reduce overfitting risk with the relatively small UAV lithology dataset. Mixed-precision training (using AMP in PyTorch) was used to accelerate computation and lower memory usage, enabling larger batch sizes under the same resource constraints.

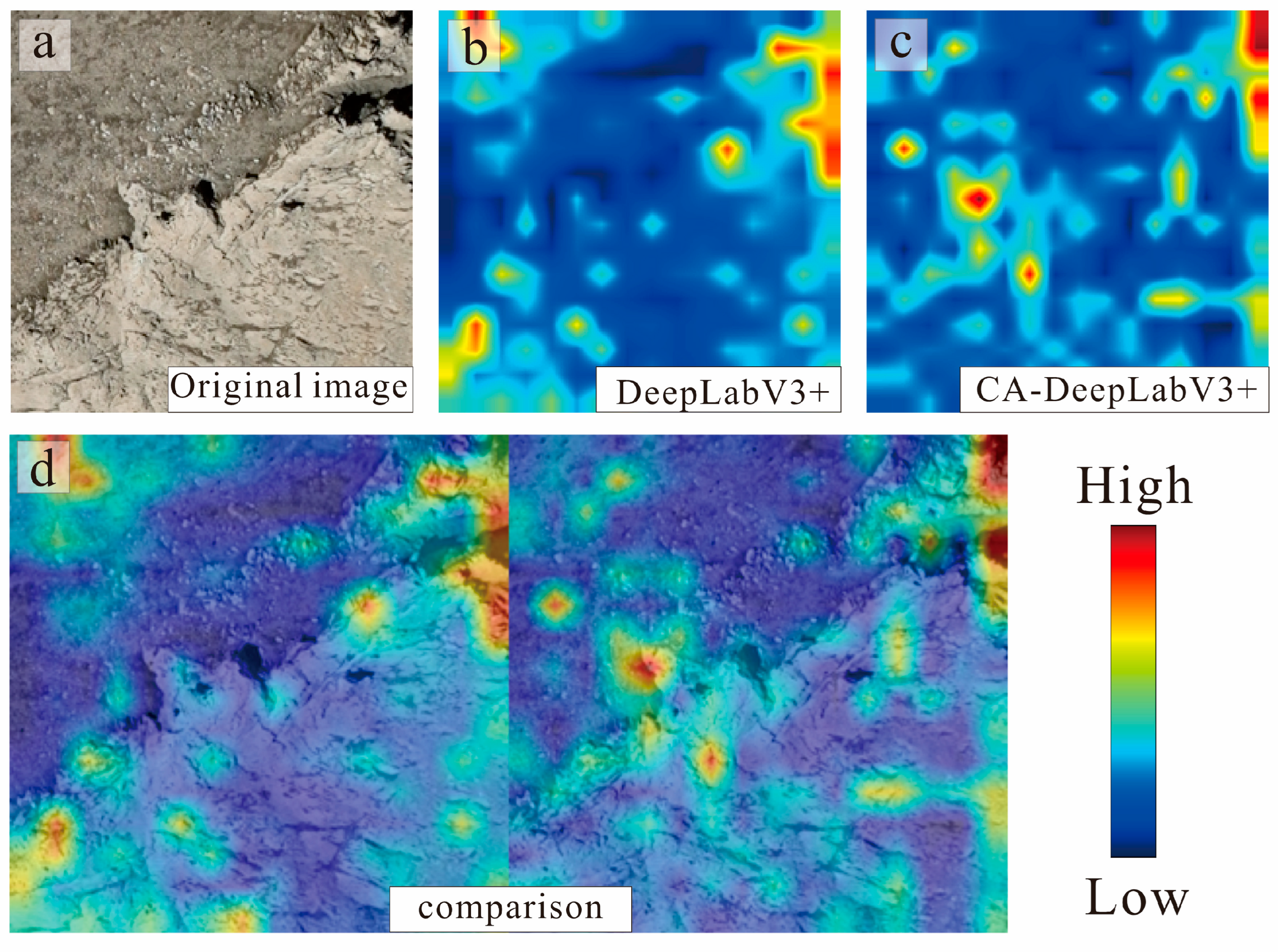

To address the difficulties intrinsic to UAV field outcrop imagery—such as blurred lithological boundaries, high intra-class texture similarity, and loss of fine-scale details—we integrated a Coordinate Attention (CA) module into DeepLabV3+. The CA mechanism augments conventional channel attention by encoding spatial positional information into the attention computation. Specifically, it separates global average pooling into two directions—horizontal (width-wise) and vertical (height-wise)—thereby capturing long-range dependencies with explicit coordinate context [

39]. This allows the network to assign higher weights to channels that are both spatially and semantically relevant, strengthening discrimination of lithologies with irregular boundaries.

For comparison, alternative state-of-the-art segmentation networks—FPN, FCN, U-Net, PSPNet, DeepLabV1, and standard DeepLabV3+—were trained and tested on the same dataset with identical preprocessing and augmentation. This ensured that performance differences reflect architectural strengths rather than data processing bias.

3.2. Semantic Segmentation Model

In recent years, digital image processing techniques have been extensively studied in the field of computer vision, with image segmentation [

40] being one of its key tasks. Image segmentation aims to classify pixels within an image, thereby identifying and separating different targets and regions. For UAV-captured field outcrop imagery, factors such as vegetation cover, rock weathering, and blurred lithological boundaries can reduce the accuracy of traditional segmentation methods. Therefore, this study adopts the DeepLabV3+ network model as the baseline segmentation framework. Proposed by Google in 2018, DeepLabV3+ builds upon an improved encoder–decoder structure and a multi-scale feature fusion strategy, enabling substantial accuracy improvements under complex background conditions. It is particularly suitable for geological imagery tasks where details are abundant and inter-class differences are subtle.

The powerful performance of DeepLabV3+ stems from the automatic feature learning capability of convolutional neural networks (CNNs). For input UAV orthophoto RGB imagery, low-level convolutions extract features such as color, edges, and fine-grained textures; mid-level convolutions capture shape contours and repetitive texture patterns; and high-level convolutions learn patterns and class combinations at a higher semantic level. These hierarchical features collectively provide the multi-scale information required for lithology identification. Unlike traditional handcrafted feature extraction methods, deep learning can directly learn the mapping between features and rock categories from large-scale annotated datasets, thereby enabling UAV imagery-driven automatic lithology recognition and mapping.

To achieve effective extraction and fusion of the aforementioned multi-level features, DeepLabV3+ employs in its encoder a feature extraction network composed of a series of inverted residual blocks. Each residual block consists of a 1 × 1 convolution for channel expansion, a depthwise separable 3 × 3 convolution, and a 1 × 1 convolution for channel reduction. The encoder output is processed by the ASPP (Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling) module, which contains a 1 × 1 convolution layer, three 3 × 3 convolution layers with different atrous rates, and a pooling layer. This multi-scale pooling approach expands the receptive field and integrates semantic information across different scales. In the decoder, the high-level features from the encoder are fused with low-level detail features from the feature extraction network. The fused features are then passed through a 1 × 1 convolution and an upsampling operation to restore spatial resolution, ultimately producing high-precision lithology segmentation results (

Figure 8).

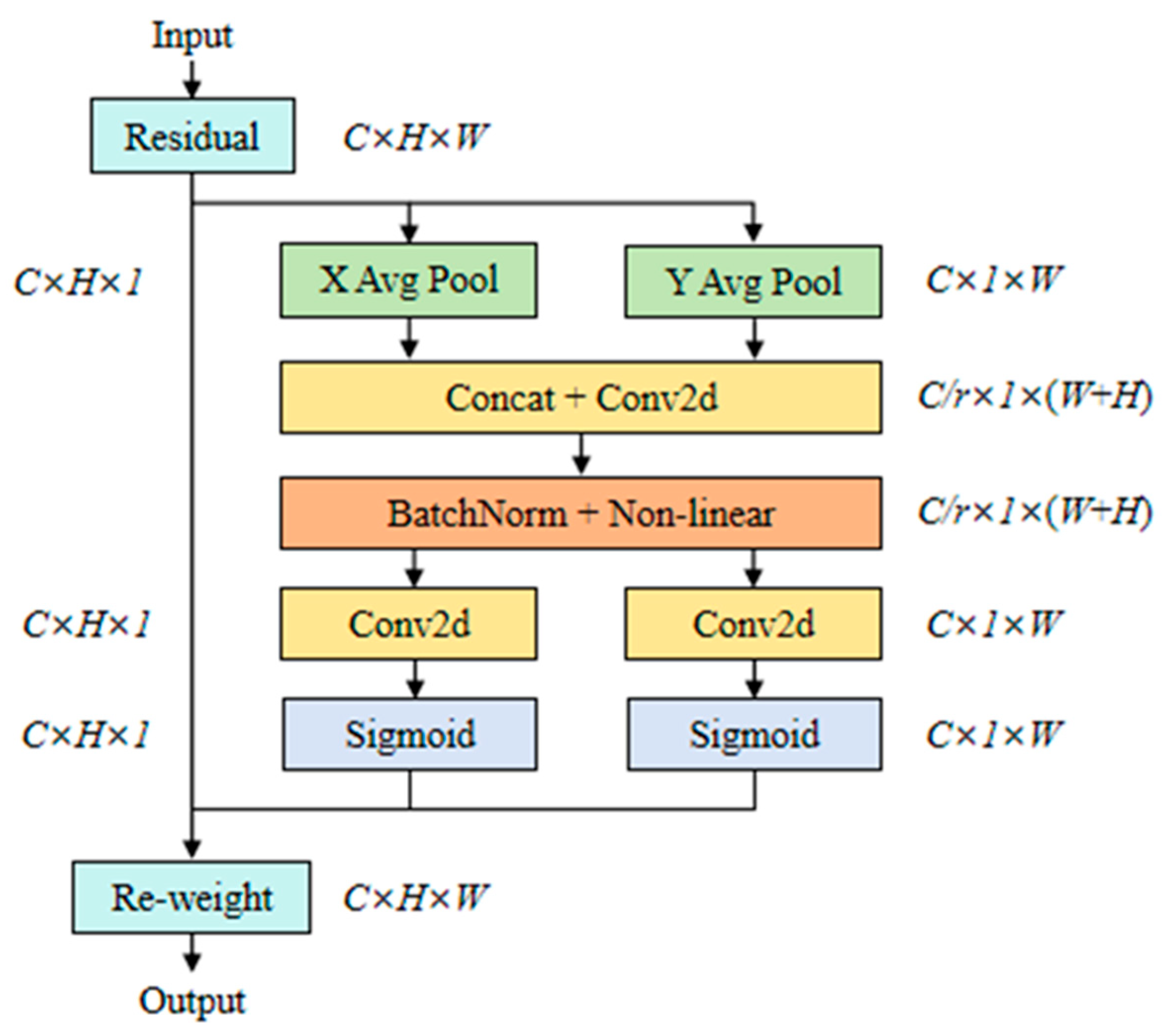

3.3. Coordinate Attention Mechanism

To address the difficulty of classifying boundary pixels for rock lithology in remote sensing imagery, an attention mechanism was incorporated into the DeepLabV3+ network. Specifically, channel attention was applied to high-level features, while spatial attention was applied to low-level features, and the two were then concatenated in series. This design enables more effective extraction of key feature information from remote sensing images, thereby improving the classification accuracy of boundary pixels.

Attention mechanisms widely used in computer vision primarily include spatial attention [

41], channel attention [

42], and hybrid attention [

43]. However, these approaches often focus solely on feature information in either the channel or spatial dimension, without emphasizing the importance of positional information. Positional information is crucial for visual tasks that aim to capture the structural characteristics of a target. Therefore, this study employs the Coordinate Attention (CA) mechanism, which is well-suited for outdoor rock lithology segmentation. CA is an improved attention mechanism designed to capture both channel attention and positional information simultaneously. Unlike traditional channel attention methods (e.g., SE-Net) that rely solely on global average pooling to obtain global channel weights, CA decomposes the global pooling operation and encodes spatial information into the channel attention. This process preserves the position-dependent characteristics of features along the height (H) and width (W) dimensions. Such capability has a significant impact on tasks requiring precise spatial localization, including semantic segmentation and object detection. The structure of the CA module is illustrated in

Figure 9. In this article, the symbols used in the network architecture are defined as follows: C denotes the number of channels in the feature map, H and W denote the height and width, respectively, and r denotes the channel reduction ratio used to control the compression of feature dimensions in the attention module.

For the input image, to avoid compressing all spatial information into the channel dimension and to capture long-range spatial interactions with precise positional cues, global average pooling is applied separately to each column and each row. This produces a width-wise feature vector of length

W and a height-wise feature vector of length

H, as follows:

The outputs are denoted as , representing the global distribution of each channel along the width dimension, and representing the global distribution of each channel along the height dimension.

Subsequently,

and

are concatenated, and passed through a shared 1 × 1 convolution followed by a non-linear activation function to generate the intermediate features:

where

F1 denotes 1 × 1 convolution, reducing the channel dimension to

C/

r × (

H +

W) (with

r being the reduction ratio, typically

r = 8), and

represents a non-linear activation function, such as Sigmoid or ReLU.

The above formulation addresses the embedding of coordinate information. Next, the directionally encoded features are split into horizontal and vertical components to generate attention weights separately. Specifically,

is split into two parts:

and

. Each part is then passed through a 1 × 1 convolution for dimensionality expansion, followed by a sigmoid activation function, resulting in the final attention vectors

and

.

where

Fh and

Fv denote 1 × 1 convolutions that restore the channel dimension to

C, and

: represents the Sigmoid function, which normalizes the weights to the range [0, 1]. The final output feature Y is obtained by the element-wise multiplication of the input X with the attention weights:

In summary, the entire process can be regarded as an automatic learning and optimization procedure for the weight coefficients of individual channels. These weights are adaptively adjusted by the network without manual intervention, thereby enhancing its ability to discriminate between different channel features and increasing the emphasis on informative features. By introducing the Coordinate Attention (CA) module, the model can assign higher weights to channels with strong responses to target features. Although this approach introduces some additional computational cost, the overall performance of the model is significantly improved. On the one hand, by encoding positional information along the height and width dimensions, CA enables the network to account for both spatial layout and channel feature importance during semantic segmentation, thus improving recognition of fine-grained textures and spatial organization. On the other hand, for rock segmentation tasks, lithological features are often associated with spatial distribution patterns (e.g., fracture orientation, bedding position), and CA helps preserve such directional information.

3.4. Experimental Environment and Parameter

The experiments were conducted on a Windows 11 operating system. A virtual working environment was configured using the Anaconda environment manager with Python 3.12.3 and PyTorch 2.6.0. The hardware setup comprised an Intel Core i9-13900HX CPU and an NVIDIA RTX 4060 GPU. The initial learning rate was set to 0.001, with the AdamW optimizer and AMP mixed-precision training employed. Due to limited computational resources, the batch size was set to 8, the number of epochs to 100, and the patch size to 256 × 256, with five target classes in total.

3.5. Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the accuracy of the constructed dataset and the applicability of the deep learning model, the experiments adopted four metrics for lithology identification performance assessment: mean intersection over union (

mIoU), class

IoU (CIoU), overall accuracy (

OA), and mean accuracy (

MeanAcc).

mIoU represents the ratio between the intersection and the union of the predicted and ground-truth regions for each class, averaged across all classes. CIoU denotes the overlap accuracy between the predicted and ground-truth regions for a single class.

OA is defined as the ratio of correctly predicted samples to the total number of samples across the entire test set.

MeanAcc refers to the average recall across all classes, reflecting the model’s ability to correctly capture each lithological category. The calculation formulas are as follows:

where

K denotes the number of labeled categories (including background);

TPk represents the number of correctly predicted pixels for class

k (true positives);

FPk denotes the number of pixels from other classes that are incorrectly predicted as class

k (false positives);

FNk denotes the number of pixels belonging to class

k that are missed by the prediction (false negatives).

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Convergence Analysis

The performance of the proposed CA-DeepLabV3+ model was benchmarked against the baseline DeepLabV3+ and other mainstream semantic segmentation networks, including U-Net, PSPNet, and DeepLabV1.

Figure 10 illustrates the loss curves across training epochs. All models exhibited a rapid loss reduction during the early stage (Epoch < 10), indicating that they quickly learned the basic discriminative features necessary for classifying different lithologies. In the mid-to-late training stage (Epoch 20–100), the rate of loss reduction slowed, approaching a stable convergence value.

CA-DeepLabV3+ demonstrated the most pronounced early-stage improvement: the loss dropped sharply to approximately 0.28 within the first few iterations, markedly faster than in other networks. This suggests that the integration of Coordinate Attention enhances the model’s ability to focus on critical spatial-channel features at an early stage, accelerating convergence. By Epoch 40, the loss fell below 0.20 and steadily decreased to ~0.06—the lowest among all tested architectures. In comparison, DeepLabV1 and standard DeepLabV3+ converged around 0.12–0.13, while U-Net and PSPNet converged more slowly and at higher final losses (>0.16).

Taken together, these results highlight the capacity of CA-DeepLabV3+ to capture key lithological features earlier in training while maintaining stable optimization in later epochs, ultimately achieving a substantially lower convergence loss than alternative methods.

4.2. Comparison Experiments of Backbone Network

To comprehensively evaluate the lightweight nature and practical deployability of the CA-DeepLabV3+ framework as implemented in this study, we conducted an efficiency analysis comparing various backbone networks. This analysis focused on two key metrics: the total number of trainable parameters and the inference time. Such quantification is crucial for understanding the model’s suitability for real-world geological mapping applications, especially in resource-constrained environments.

We integrated the Coordinate Attention mechanism and the DeepLabV3+ decoder structure with five different backbone networks: MobileNetV2 (our primary choice), ResNet50, ResNet101, EfficientNet-B3, and timm-mobilenetv3_large_100. All models were evaluated on the same hardware setup (NVIDIA RTX 4060 GPU, NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with an input image size of 256 × 256 pixels and a batch size of 1. Inference times were averaged over 100 runs after 10 warm-up runs to ensure stable measurements. The results are summarized in

Table 1.

As shown in

Table 1, the choice of backbone network significantly impacts both the model’s parameter complexity and its inference speed. Our primary backbone, MobileNetV2, consistently demonstrates superior efficiency, featuring the lowest parameter count of 4.54 Million and the fastest inference time of 0.0046 s (4.6 ms) per image. This performance is notably better than heavier backbones like ResNet50 (27.08 Million parameters, 0.0052 s) and ResNet101 (46.07 Million parameters, 0.0086 s), which, while offering greater representational capacity, incur substantially higher computational overhead. Even when compared to other lightweight architectures such as EfficientNet-B3 (11.70 Million parameters) and timm-mobilenetv3_large_100 (4.80 Million parameters), MobileNetV2 maintains a competitive edge in inference speed.

This efficiency analysis underscores the practical advantages of our CA-DeepLabV3+ model with the MobileNetV2 backbone. It confirms that our design choice effectively achieves the goal of a lightweight architecture, enabling faster training and inference without compromising accuracy. Such computational efficiency is paramount for deploying deep learning models in large-scale geological surveys where rapid processing and limited hardware resources are common constraints.

4.3. Quantitative Evaluation

As shown in

Table 2, all tested networks achieved relatively high accuracy after sufficient training. Traditional frameworks such as FPN, FCN, and U-Net delivered stable performance in overall accuracy (OA), mean accuracy (MeanAcc), and mean intersection over union (mIoU). Among them, FCN recorded the highest mIoU (92.99%) within traditional architectures, while U-Net attained a slightly higher MeanAcc (95.02%) but a lower mIoU (90.07%), reflecting its limitations in fine-grained boundary extraction. PSPNet, despite its multi-scale pyramid pooling module, produced an mIoU of only 90.03%—likely affected by the high texture complexity and inter-class spectral similarity in field lithology imagery. DeepLabV1 benefited from atrous convolution to expand the receptive field while preserving resolution, yielding OA = 96.68% and MeanAcc = 96.83%, the highest among non-attention models.

In further comparative experiments, standard DeepLabV3+ improved segmentation consistency through the ASPP module and decoder refinement. However, CA-DeepLabV3+ outperformed all baselines across metrics—OA = 97.95%, MeanAcc = 97.80%, mIoU = 95.71%—representing relative gains of +2.87%, +2.76%, and +5.48% over standard DeepLabV3+. These gains confirm that coordinate attention effectively models spatial–channel dependency, enabling more precise boundary localization and detailed texture preservation while maintaining robust global context modeling.

From a feature extraction perspective, embedding coordinate information into channel attention allows simultaneous modeling of long-range contextual dependencies and local structural details. This is particularly advantageous in UAV field imagery, where lithologies often share similar colors/textures and have irregular boundaries. By enriching global semantics with focused positional attention, the CA module reduces misclassification and boosts segmentation accuracy for small targets (

Figure 11). Furthermore, during high-resolution feature reconstruction, CA-DeepLabV3+ achieves enhanced edge preservation owing to its independent horizontal–vertical encoding mechanism, thereby improving the network’s spatial resolution awareness.

4.4. Category-Specific Performance

Table 3 compares CIoU values across lithological categories. Sandstone, marble, and diorite reported consistently high CIoU scores across models, indicating stable and distinguishable spectral-textural properties. Notably, sandstone CIoU exceeded 96% for all methods, with CA-DeepLabV3+ achieving 98.48%. Marble recognition remained strong (>87% CIoU in all cases) due to its distinct brightness and texture, with CA-DeepLabV3+ attaining 94.62%. Diorite, characterized by visible mineral grain patterns, achieved a maximum CIoU of 94.86% in CA-DeepLabV3+, outperforming other models.

Quaternary sediments posed the greatest challenge, with CIoU scores as low as 77–79% for PSPNet and U-Net, and 79.24% for standard DeepLabV3+. Causes include strong spectral resemblance to sandstone, fine-grained structure variability, dust cover from weathering, and blurred visual boundaries. CA-DeepLabV3+ improved Quaternary sediment CIoU to 90.66%, a +11.42% gain over the baseline—and the only score exceeding 90% among all networks—underscoring its effectiveness for visually similar, heterogeneous classes.

By incorporating refined spatial positional encoding into multi-scale contextual extraction, CA guides the network toward key spatial regions during category separation, reducing both false positives and false negatives.

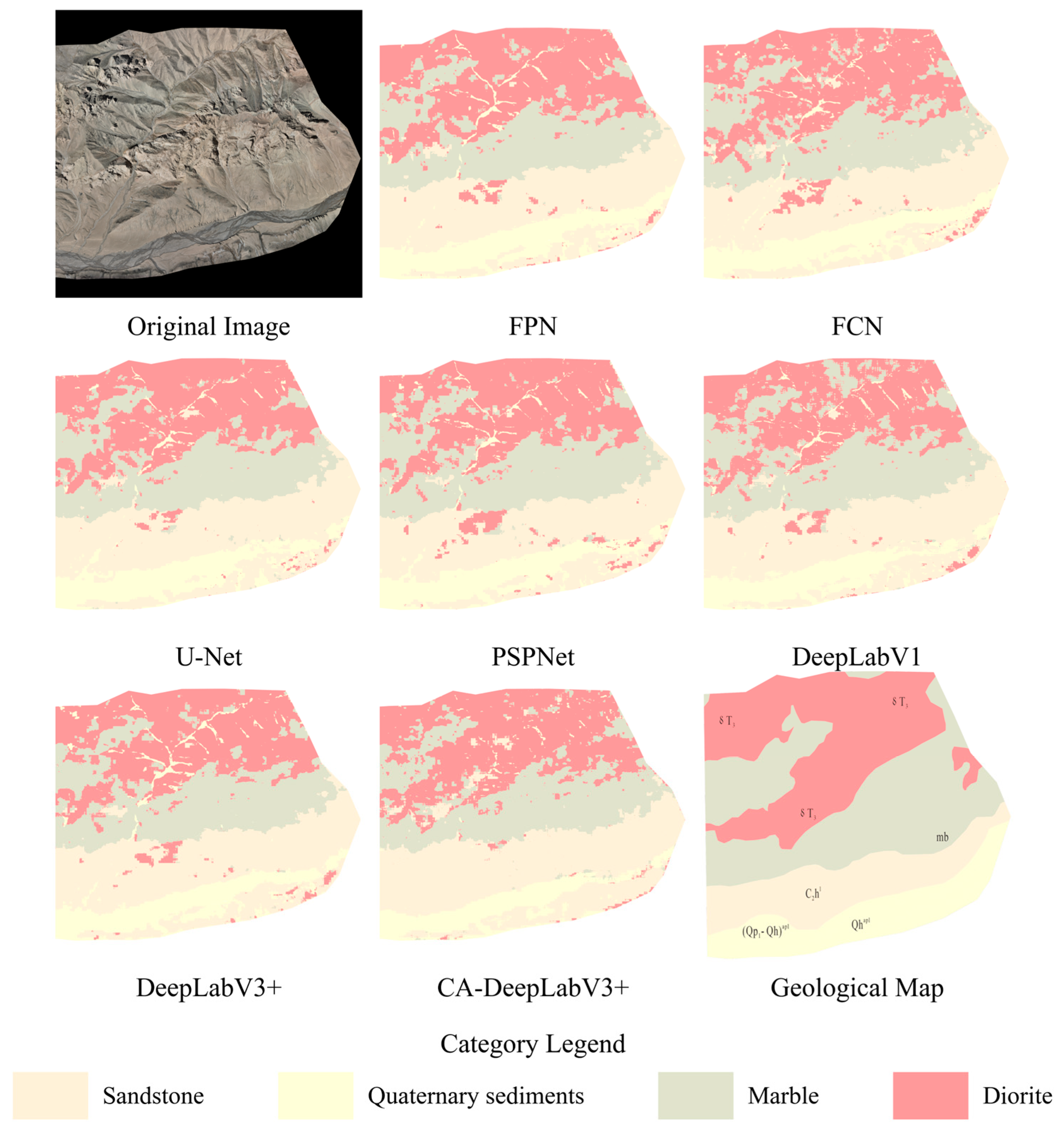

Figure 12 visualizes this improvement: all networks approximated the overall lithology distribution, but CA-DeepLabV3+ achieved the cleanest category boundaries and preserved fine-scale texture details, aligning with quantitative gains. For clearer interpretation of the model’s predictions,

Figure 12 compares the predicted lithological map directly with the detailed geological map of the same area. This visual comparison reveals good agreement in the main lithological boundaries and unit distributions, supporting the reliability of the model’s outputs.

4.5. Field Validation and Error Correction Capability

High-altitude, deeply dissected regions present severe mapping challenges, including steep relief, sparse accessibility, extreme climate, and uneven outcrop visibility [

44]. Conventional surveys often yield discontinuous, sample-based observations that cannot capture complete spatial patterns. Portable UAVs, with low-altitude oblique photogrammetry, offer centimeter-level, multi-view coverage of otherwise inaccessible areas, bridging gaps between field photography and remote sensing continuity [

45].

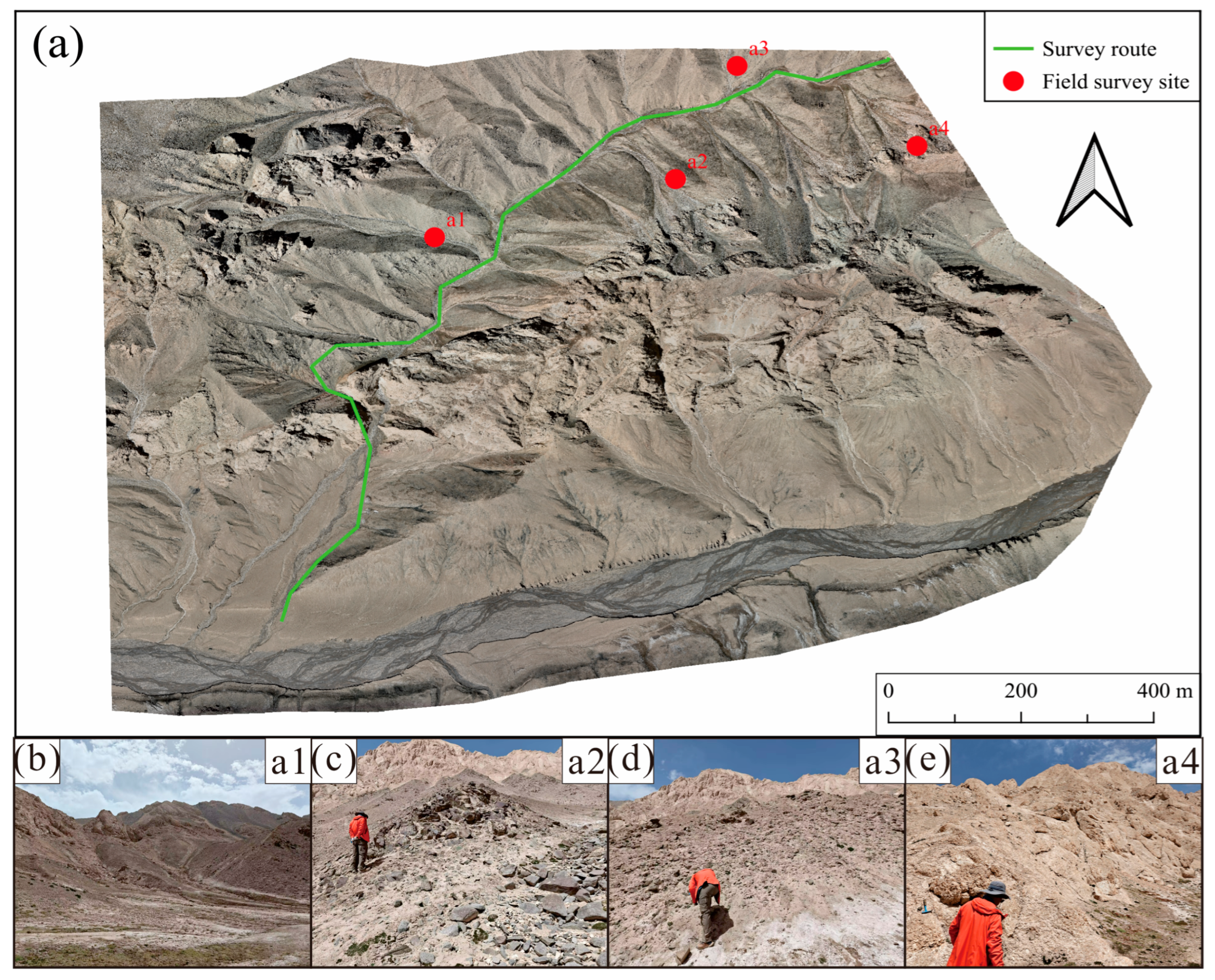

Following model training, a field validation was conducted in a representative lithological zone in the eastern study area (

Figure 13).

The lithological distribution within the validation area exhibits a clear spatial zonation pattern. Marble is widely distributed across mid-to-upper-slope sections and exposed mountain bodies, appearing gray-white to light gray in color with medium-to-thick-bedded structures. Diorite primarily intrudes along fault zones into marble strata, showing a gray-black color and massive structures. Sandstone is concentrated on gentle lower slopes and the mid-sections of valley slopes, characterized by light yellow to brown coloration and thick-bedded structures. Quaternary sediments fill the lowest depressions of river valleys and gullies, consisting mainly of gravel, sand, and silt, with loose structures and poor particle sorting. The lithological contact boundaries and overall distribution patterns are jointly controlled by river valley erosion and tectonic activity.

During the field validation, we identified an area located to the north of the survey route (

Figure 13d) that had been misclassified as marble during the initial manual annotation stage. This misclassification primarily stemmed from visual interpretation errors based on imagery: in the UAV orthophoto, the area exhibited a relatively light tone similar to typical marble, leading to failure in recognizing it as heavily weathered diorite. However, the deep learning-based lithology classification model predicted this area as diorite, and this identification was fully confirmed during the field survey.

This observation indicates that the deep learning model can classify lithologies by leveraging multidimensional image features—such as texture, spatial distribution patterns, and relationships with adjacent strata—and that its predictions can, to a certain extent, correct systematic errors that may arise from manual interpretation. In the context of remote-sensing-based geological surveys, this qualitative demonstration of “automatic error-correction” capability is of considerable significance: on the one hand, it can reduce the influence of subjective human judgment on lithological delineation, thereby enhancing the objectivity and consistency of the results; on the other hand, when field conditions are constrained (e.g., steep terrain, obstructed viewpoints), model predictions can serve as a reliable reference for geologists, reducing redundant fieldwork and the cost of post hoc revisions. Therefore, the practical validation conducted in this study demonstrates the potential of integrating UAV remote sensing with deep learning in geological surveying—not only as a tool for automated recognition, but also as an effective means to improve geological data accuracy and correct human interpretation errors. Crucially, this real-world field validation on unseen terrain served as the ultimate robust assessment of the model’s generalization capabilities, providing strong evidence against overfitting to the training data.

4.6. Practical Implications for Geological Mapping

Combining multi-view, high-resolution UAV imagery with the CA-DeepLabV3+ segmentation framework enables precise lithology identification under extreme topographic constraints. The approach reliably recognizes small-scale lithological variations, leverages the fine detail of UAV data, and addresses limitations of accessibility and coverage in mountainous gorge regions.

Regarding its generalizability, the model typically requires retraining or fine-tuning when applied to new geological settings with different lithologies or significantly varying environmental conditions. This is because deep learning models learn patterns specific to their training data. However, the use of a lightweight backbone (MobileNetV2) and transfer learning facilitates faster adaptation to new datasets. For readers unfamiliar with UAV-based deep learning workflows, it is important to clarify that the initial identification of lithologies in the training area, as detailed in

Section 2.2 relies on a combination of expert geological guidance, existing large-scale geological maps, and meticulous visual interpretation of the UAV orthophotos. In areas entirely lacking prior lithological information, the framework would initially require a geologist to provide a limited set of high-confidence labels for new rock types (e.g., through active learning or weakly supervised methods) to guide the model’s learning process.

However, it is crucial to discuss the method’s applicability under varying conditions. For instance, its performance in areas with dense vegetation cover is inherently limited when relying solely on visible light imagery, as vegetation can obscure underlying lithological features. In such scenarios, integration with multispectral or hyperspectral data, or bare-earth models derived from LiDAR, would be necessary to effectively delineate obscured rock units. Similarly, distinguishing between lithologies that exhibit very subtle visual characteristics, such as various types of quartz schist, mica schist, and calcite schist in metamorphic terrains, presents a significant challenge for RGB-based deep learning models. While the Coordinate Attention mechanism aids in capturing nuanced textural and spatial differences, achieving robust discrimination in these highly ambiguous cases might necessitate incorporating additional geological features or more advanced spectroscopic data.

Despite these considerations, the framework’s demonstrated capability to produce high-precision lithological maps in the complex geomorphic conditions of the Ququleke area is substantial. This methodology can be extended to various applications, including geological mapping, mineral resource prediction, and hazard assessment in other high-altitude, deeply dissected terrains, thereby enhancing both accuracy and efficiency in field geological surveys. Future work will focus on integrating multi-sensor data and advanced annotation strategies to broaden the method’s robustness and applicability across a wider spectrum of complex geological environments.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a novel methodology was presented that pioneers the integration of portable UAV oblique photogrammetry with a Coordinate Attention-enhanced DeepLabV3+ semantic segmentation framework for automated lithological mapping in complex geological scenes. High-resolution UAV orthophotos of the Ququleke area were utilized to construct a pixel-level lithology dataset comprising sandstone, marble, diorite, and Quaternary sediments. The CA-DeepLabV3+ model, an enhanced version of the DeepLabV3+ framework, effectively integrates the Coordinate Attention mechanism to strengthen spatial position encoding and fine-scale feature extraction, crucial for detailed lithological discrimination.

Experimental results confirmed substantial performance improvements, with overall accuracy of 97.95%, mean accuracy of 97.80%, and mIoU of 95.71%, outperforming all comparative models. The CA mechanism effectively preserved boundary details and fine textures, significantly improving the recognition of visually similar lithologies such as Quaternary sediments. Field validation further demonstrated that the model can correct manual mapping errors and deliver reliable lithological interpretation under harsh terrain conditions.

Overall, the proposed UAV-based deep learning approach provides an efficient and accurate solution for automatic lithological mapping in high-altitude and inaccessible regions. It offers a valuable technical reference for geological investigation, mineral resource assessment, and the broader application of low-altitude remote sensing in field geology.