1. Introduction

The gyroplane is similar to a helicopter in having a large rotor on top to generate lift. Unlike helicopters, however, its rotor is driven by the incoming airflow rather than by engine power [

1], which leads to minimal counter-torque and thus does not require an associated torque-balance mechanism. In addition, the large rotor diameter and high-speed rotation provide strong damping and gyroscopic effects, significantly enhancing flight stability [

2]. The development of gyroplanes can be traced back to the pioneering work of Spanish engineer Cierva in the 1920s [

3]. Due to the limitations of the rotor connection structure, which restricted high-speed flight capability, gyroplanes were gradually replaced by helicopters after the 1940s. Nevertheless, because of their mechanical simplicity, excellent low-speed performance, and cost-effectiveness, light gyroplanes once again attracted attention from 1955, marked by the introduction of the Bensen-8M “Gyrocopter” [

4]. Since then, NASA and other institutions [

5] have gradually resumed research on unmanned gyroplane design, modeling, and control.

Dynamic modeling is the foundation of flight control design and simulation. The modeling methods for unmanned gyroplanes have evolved from theoretical aerodynamic analyses to high-fidelity numerical simulations. McCormick’s theory established the basis for gyroplane performance studies [

6] and was later extended to high Reynolds number conditions to capture the transient aerodynamic effects [

7]. Subsequent studies have gradually focused on component-level modeling and flow interactions between the rotor and fuselage [

8,

9]. However, despite the maturity of traditional aerodynamic theories, their limited accuracy and computational complexity have restricted practical applications [

10]. In recent years, geometric mechanics approaches have been proposed to model the nonlinear dynamics of complex rotating systems [

11], which enable structure-preserving numerical simulations. The strong nonlinearity in unmanned gyroplane aerodynamics remains a major challenge to capturing overall aerodynamic dynamics accurately.

Effective dynamic modeling for helicopters typically relies on professional simulation platforms, which are supported by extensive flight test databases. However, due to the slow development of gyroplanes, comparable mature tools are still lacking. To address this limitation, system identification has been recognized as a practical approach for unmanned gyroplane modeling, and the University of Glasgow has achieved significant progress in modeling, flight dynamics, and flight quality analysis [

12,

13,

14]. Thomson and Houston revealed the nonlinear characteristics underlying unmanned gyroplane flight dynamics and improved model accuracy through experimental measurements [

15]. Meanwhile, based on these results, flight quality has been further analyzed [

16,

17], and these analyses provide a foundation for control system design [

18]. Nevertheless, compared with fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters, unmanned gyroplane modeling methods remain of limited reliability and present significant challenges for flight control design.

With the development of unmanned aerial vehicles, the autonomous control of unmanned gyroplanes has gradually become a central topic [

4]. Based on linearized models and simulation environments, traditional proportional-integral-derivative (PID) and nonlinear PID methods have been implemented to improve the stability and safety of unmanned gyroplanes under various flight conditions [

19,

20,

21]. Subsequently, the dynamic behavior of compound gyroplanes has been explored [

22,

23], and a precise altitude control strategy was proposed [

24]. Nevertheless, since the unmanned gyroplane relies on passively driven rotors to generate lift, its dynamics exhibit strong nonlinearity and coupling, which continue to hinder the development of effective control designs [

19,

22,

25]. Firstly, the lack of high-fidelity dynamic models introduces uncertainties into the control system. Furthermore, the three-axis attitude and velocity of the unmanned gyroplane are governed by the rotor disk, resulting in strong coupling among the channels. Finally, the flexible connection between the rotor and the fuselage generates a pendulum effect, leading to a noticeable lag in attitude response.

To address these challenges, this paper developed a high-fidelity aerodynamic model based on system identification, analyzed the unique flight characteristics of unmanned gyroplanes, and subsequently proposed an autonomous flight control system for unmanned gyroplane platforms. The main motivation of this study is to overcome the control coupling, delayed pitch response, and nonlinear throttle-airspeed dynamics, thereby enabling autonomous and precise control of unmanned gyroplane systems. The key contributions are fourfold:

- (1)

A modified identification model structure is developed, which eliminates terms with low coherence or frequency mismatch, thereby improving the accuracy of the identified aerodynamic model.

- (2)

A trim-decoupling feedforward control strategy is proposed, which mitigates the control interference between the longitudinal and lateral channels under a single-actuator configuration.

- (3)

A pitch-damping augmentation control combined with rotor-tilt-based allocation is proposed to achieve efficient and precise airspeed tracking, overcoming the performance degradation of conventional flight control frameworks when applied to unmanned gyroplanes.

- (4)

The proposed control strategy is implemented on an unmanned gyroplane prototype converted from a manned vehicle, enabling fully autonomous flight.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the unmanned prototype gyroplane platform and the modified aerodynamic identification model.

Section 3 presents the evaluation of the identified model and the corresponding modal analysis. In

Section 4, control challenges of unmanned gyroplanes are described, followed by the development of the autonomous flight control system.

Section 5 provides the experimental validation, where the flight data and control performance are analyzed. Finally,

Section 6 summarizes the main conclusions.

2. Configuration for Parameter Identification

Following the objectives described in

Section 1, this section introduces the configuration and methodology used for aerodynamic parameter identification of the unmanned prototype gyroplane. First, the flight test platform and onboard data acquisition system are described. Then, the excitation input design for system identification is presented. Finally, a modified aerodynamic model structure is proposed to enhance model accuracy.

2.1. Flight Test Platform

The unmanned prototype gyroplane used for validation in this study is the Spanish ELA-07 autogyro, manufactured by ELA Aviación of Fuente Obejuna, Córdoba, Spain, with its main parameters listed in

Table 1. The aircraft features a semirigid rotor with fixed pitch blades, a tricycle landing gear, three vertical tails, and a horizontal stabilizer. It is operated via four actuators: a longitudinal rotor tilt stick, a lateral rotor tilt stick, the engine throttle, and the rudder. The empty weight is 258 kg, allowing for a payload of 192 kg, and is powered by a ROTAX 912 engine, manufactured by BRP-Rotax GmbH & Co KG of Gunskirchen, Austria. The actual aircraft is shown in

Figure 1.

A reliable hardware system for synchronous data acquisition is essential for accurate identification, as delays and sampling frequencies of input/output data directly affect the convergence of the identification process. According to engineering practice, the sampling frequency should be at least 25 times the maximum target frequency [

26]. In this study, flight data were recorded at 100 Hz. The data logger, MPC5674 flight control computer, global positioning system (GPS), and attitude sensors were installed near the center of gravity. Considering the actuation mechanisms of the joystick and the rudder, displacement sensors were used to measure the relative deflections of the rotor tilt angles and the rudder surface.

2.2. Input Signal for Parameter Excitation

The typical 2-1-1 square wave, characterized by alternating positive and negative pulses in a 2:1:1 width ratio, was selected as the experimental excitation signal. Its frequency spectrum is broad, allowing sufficient excitation energy within the target modal range by adjusting the pulse width. Two parameters, amplitude and frequency, must be specified.

The amplitude was determined such that the response of the angular rate reached about ±10°/s. The frequency of the 2-1-1 square wave

was designed to be close to the natural frequency

of the aircraft dynamics to adequately excite the motion modes. The following relation is commonly used in engineering practice [

27]

The typical attitude frequency of the unmanned gyroplane is approximately 0.25 Hz [

14]; therefore, the unit pulse width of the 2-1-1 input was set to 1.5 s.

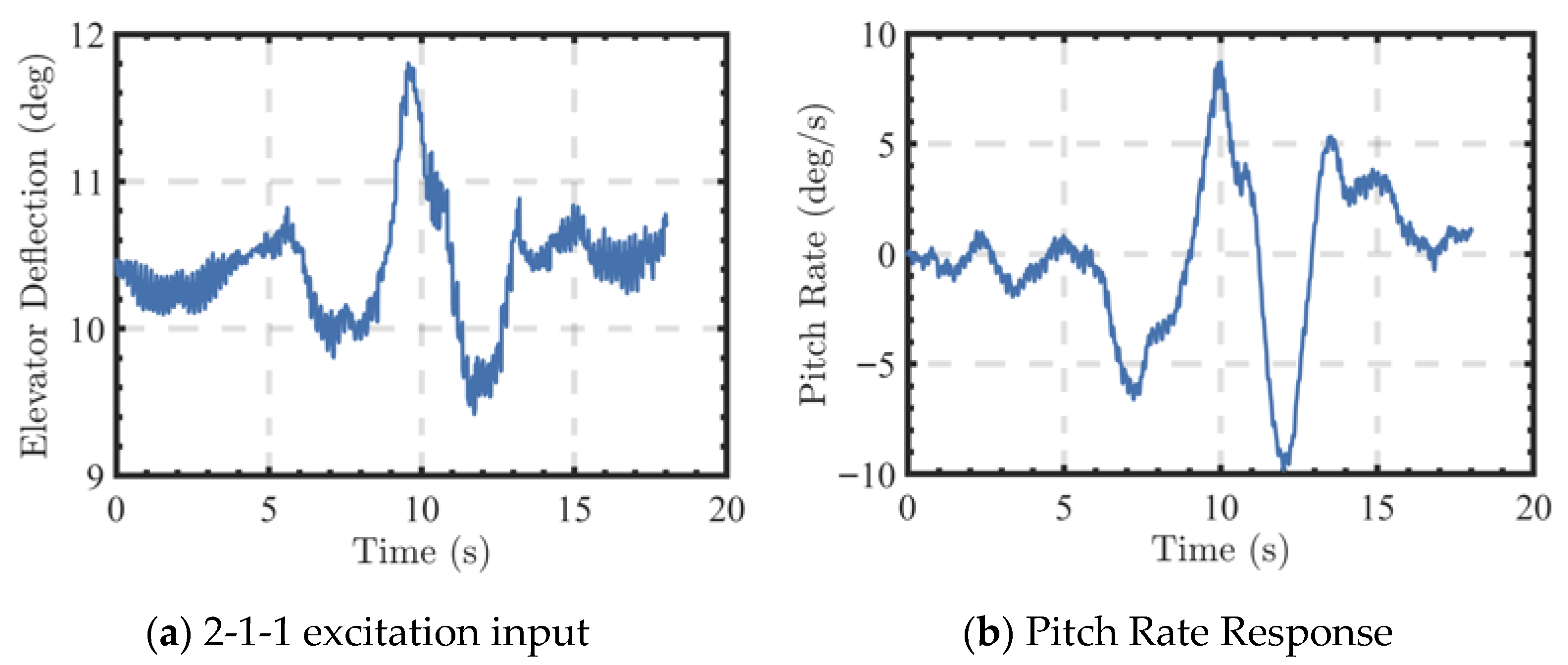

Figure 2 shows the actual rotor longitudinal tilt input and the corresponding pitch rate response during a 2-1-1 excitation test. Each test started and ended in a steady state, and a steady flight of at least 3 s was maintained before and after the excitation.

2.3. Identification Model Structure and Modification

Based on the gyroplane aerodynamic identification model developed in Ref. [

14], a modified model structure is proposed in this section. Flight data were analyzed using coherence functions [

28], and the model formulation is further guided by prior knowledge of the prototype gyroplane.

Considering the six-degree-of-freedom linear aerodynamic model of aircraft, a decoupled model for longitudinal and lateral dynamics is proposed. The state space equation can be described as

where

A is the state transition matrix,

B is the input matrix,

u is the control vector, and

x is the state variables.

For the longitudinal model, the state variables consist of the body-axis forward velocity u, vertical velocity w, pitch angle q, pitch angle rate q, and rotor speed W; and the control variable is the longitudinal deflection of the rotor. For the lateral model, the state variables consist of the sideslip angle b, roll rate p, yaw rate r, and roll angle j; and the control variables are the lateral deflection of the rotor and rudder deflection .

According to the Nyquist criterion and identification practice, a common requirement for ensuring sufficient amplitude and phase resolution is that the identifiable bandwidth should be no less than one-fifth of the sampling frequency [

29]. Given the 100 Hz data-logging rate in our flight tests, the effective update rate of the rotor speed W (below 5 Hz) falls far short of the 20 Hz minimum required for reliable identification. Therefore, with the rotor speed excluded from the state variables, the modified longitudinal aerodynamic model is established as

where

X∗,

Z∗, and

M∗ represent the derivatives of the longitudinal force, vertical force, and pitching moment with respect to the corresponding variable “*”, respectively.

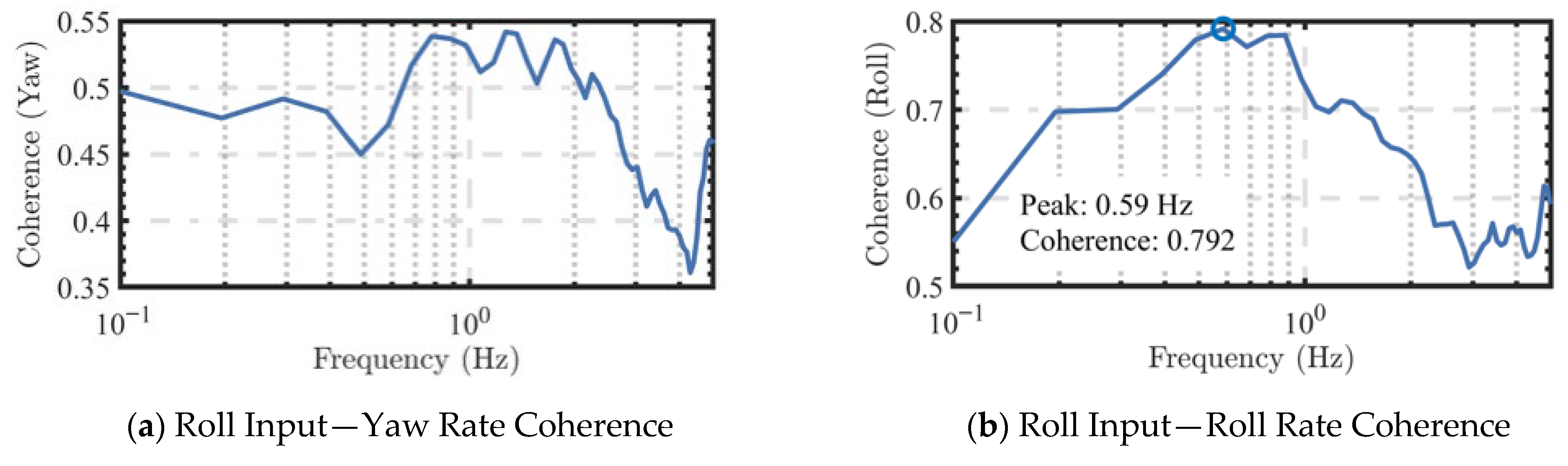

Coherence analysis was conducted to simplify the lateral aerodynamic model.

Figure 3a presents the coherence function between roll excitation and the corresponding yaw rate, while

Figure 3b shows the between roll excitation and roll rate.

Within the frequency range of interest 0.2~2 Hz, the coherence function between roll excitation and yaw rate remained below 0.6, indicating weak correlation. In contrast, the coherence between roll and roll rate exceeded 0.6 and showed no oscillations at low frequencies. Since a coherence level above 0.6 is generally regarded as acceptable for system identification [

30,

31], these results confirm good coherence quality. Therefore, it is suggested that lateral rotor deflection primarily excites roll responses while inducing weak yaw coupling. Similarly, in rudder excitation tests, rudder inputs primarily affect yaw motion and show a slight influence on roll responses.

Thus, the modified lateral aerodynamic model is given as

where

Y∗,

L∗, and

N∗ represent the derivatives of the lateral force, rolling moment, and yawing moment with respect to the corresponding variable “*”, respectively.

3. Evaluation of Aerodynamic Model and Modal Characteristics

According to the model structure defined in

Section 2, the aerodynamic model is decoupled into individual channels and identified using a combined method to ensure both efficiency and accuracy. The equation error method solved via linear regression provided an initial estimate, which was optimized by the maximum likelihood method to minimize the output error [

32]. Based on the identified results, a six-degree-of-freedom model for the unmanned gyroplane was constructed, and its validity and modal characteristics were analyzed, which serves as a basis for flight control law design.

3.1. Time and Frequency Domain Validation

Flight tests were conducted at an airspeed of 31.5 m/s and an altitude of 200 m, with multiple longitudinal and lateral excitations. The aerodynamic force and moment derivatives obtained for each group exhibited an approximately normal distribution with low dispersion. By taking the expected values, the state and input matrices of the state-space functions in Equations (3) and (4) were derived. For the longitudinal model, there is

and for the lateral-directional model, there is

The identified aerodynamic derivatives exhibited physically stable dynamics.

Remark 1. The Dutch-roll mode is typically unstable. However, in Equation (6), the Dutch-roll damping Nr is relatively large, and specifically, Nb > 0, leading to a stable Dutch-roll mode. This stability is attributed to the tail flow generated by the propeller, which increases the rudder damping.

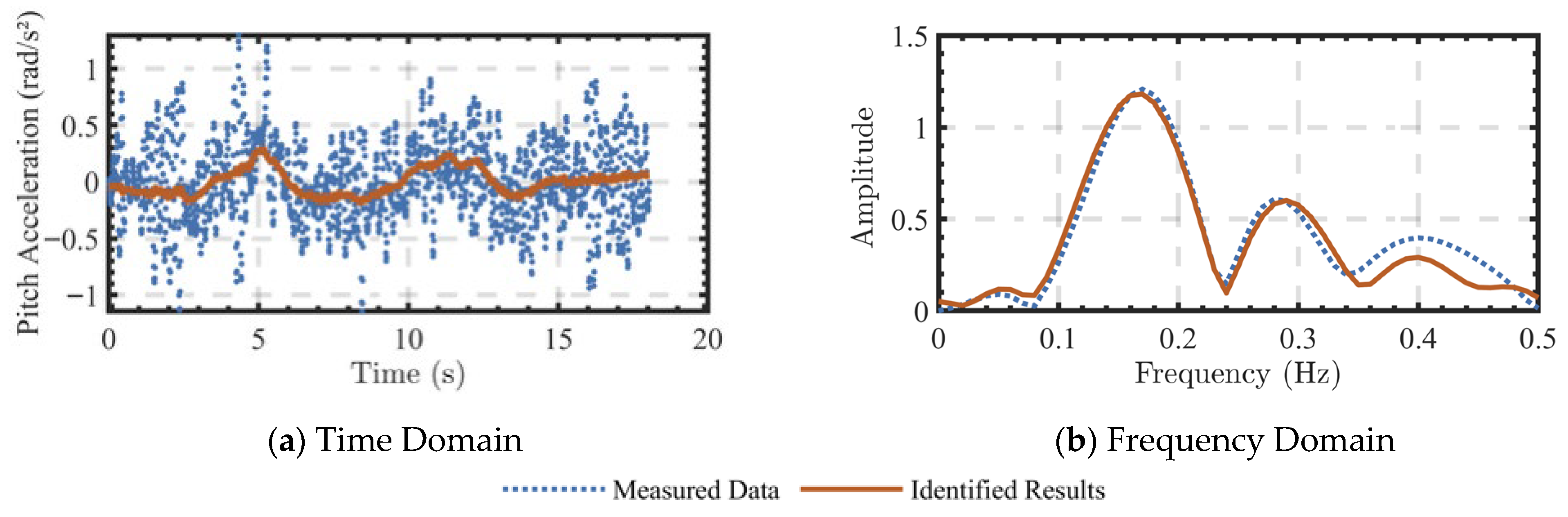

To assess the model’s credibility [

33], simulations were conducted in both the time and frequency domains. Flight data not used for identification were applied as inputs to the identified model given by Equations (5) and (6), and the attitude responses of the model were compared with the actual flight data. The coefficient fitting results for derivatives of the pitch, roll, and yaw moments are presented in

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, respectively. Each figure shows the total response of the linearized system, resulting from the combined contributions of the state-feedback and control input terms. The corresponding attitude responses are shown in

Figure 7. The mean absolute error (MAE), standard deviation (SD), and coefficient of determination between the measured and identified attitude responses are summarized in

Table 2. A positive phase delay indicates that the simulation leads the flight data, whereas a negative phase delay indicates a lag.

As shown in

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, the responses of the identified model and the measured flight data exhibited high consistency under identical excitation. In the time-domain results of

Figure 4a,

Figure 5a and

Figure 6a, the measured and estimated coefficients shared a consistent tendency, although considerable noise was observed in the measurements. To further evaluate the accuracy of parameter identification, frequency-domain fitting was employed, as illustrated in

Figure 4b,

Figure 5b and

Figure 6b, where the spectral characteristics of the measured and estimated parameters showed a high degree of consistency.

Figure 7 demonstrates that the time-domain attitude responses of the pitch, roll, and yaw rates matched well with the measured data. Quantitatively, as shown in

Table 2, all channels achieved low MAE values (within 2 deg/s) and high coefficients of determination (above 0.92), confirming the reliability of the identified aerodynamic model. In particular, compared with the results reported in [

33], where the roll rate exhibited a noticeable phase lag between simulation and measurement, the present model achieved a marked improvement, with the phase delay reduced to 0.08 s.

Overall, the modifications to the aerodynamic model presented in

Section 2.3 were demonstrated to be effective, and the accuracy of the unmanned prototype gyroplane model was confirmed.

3.2. Modal Characteristics Analysis

Based on the identified longitudinal and lateral-directional linear models, the modal characteristics of the unmanned prototype gyroplane were obtained, as shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4. The eigenvalues in

Table 3 and

Table 4 (e.g., −0.040 ± 0.290 i) are complex numbers, where “i” denotes the imaginary unit.

For the longitudinal dynamics, the unmanned prototype gyroplane exhibited both short-period and phugoid modes, similar to those for fixed-wing aircraft [

34]. As shown in

Table 3, the short-period mode had a period of 3.696 s, which was slightly slower than that of fixed-wing aircraft (2–3 s), and a damping ratio of 0.395, indicating good pitch stability. The phugoid period had a period of 21.444 s with a low damping ratio; therefore, additional damping through altitude control is required to satisfy flight quality requirements.

In terms of lateral-directional dynamics, the unmanned prototype gyroplane exhibited typical roll, Dutch-roll, and spiral modes. As shown in

Table 4, the Dutch-roll mode had a pair of negative roots with a period of 3.673 s and a damping ratio of 0.222. This oscillatory mode arises from a coupling between roll, sideslip, and yaw motions when a sideslip disturbance occurs. Its frequency is primarily governed by

Lb and

Nb, while its damping is significantly influenced by yaw damping

Nr and roll damping

Lp. The roll mode had a time constant of 3.34 s, indicating fast convergence due to the large roll damping derivative

Lp. The spiral mode had a long-time constant of 78.994 s, determined by the small roll static stability and large yaw static stability derivatives. Since the spiral mode converged slowly, its impact on short-term flight dynamics was relatively small.

The spiral mode time constant can be calculated analytically [

30]. From Equation (4), by assuming that the

Lr and

Np terms of the unmanned prototype gyroplane are zero, a simplified expression is obtained

where

g is the gravitational acceleration, and

ls is the eigenvalue of the spiral mode.

This analytical approximation is highly effective for estimating the spiral mode eigenvalue. From Equation (7), the spiral eigenvalue ls is influenced by both Lp, Lb, Nb, and Nr. Specifically, the large value of yaw damping Nr and the positive dihedral effect Lb both contribute to the negative eigenvalue, thereby ensuring a stable spiral mode.

In conclusion, the identified aerodynamic parameters accurately reproduce the flight dynamics of the unmanned prototype gyroplane, demonstrating high fidelity across three-axis attitude maneuvers. The modal analysis clarifies the dynamic characteristics of both longitudinal- and lateral-directional modes, thereby establishing a reliable basis for the design of control systems.

6. Conclusions

To address the key issues in aerodynamic modeling and control design of unmanned gyroplanes, a targeted methodology is proposed in this paper.

For aerodynamic modeling, a modified parameter identification structure was developed based on coherence analysis, which effectively improved the modeling accuracy. Both time-domain and frequency-domain validations demonstrated that the identified model reproduces the longitudinal and lateral dynamics with high fidelity. In particular, the coefficients of determination exceeding 0.92 and the small phase delays within ±0.1 s indicate high consistency between the identified model and flight responses, thereby providing a solid foundation for subsequent control design.

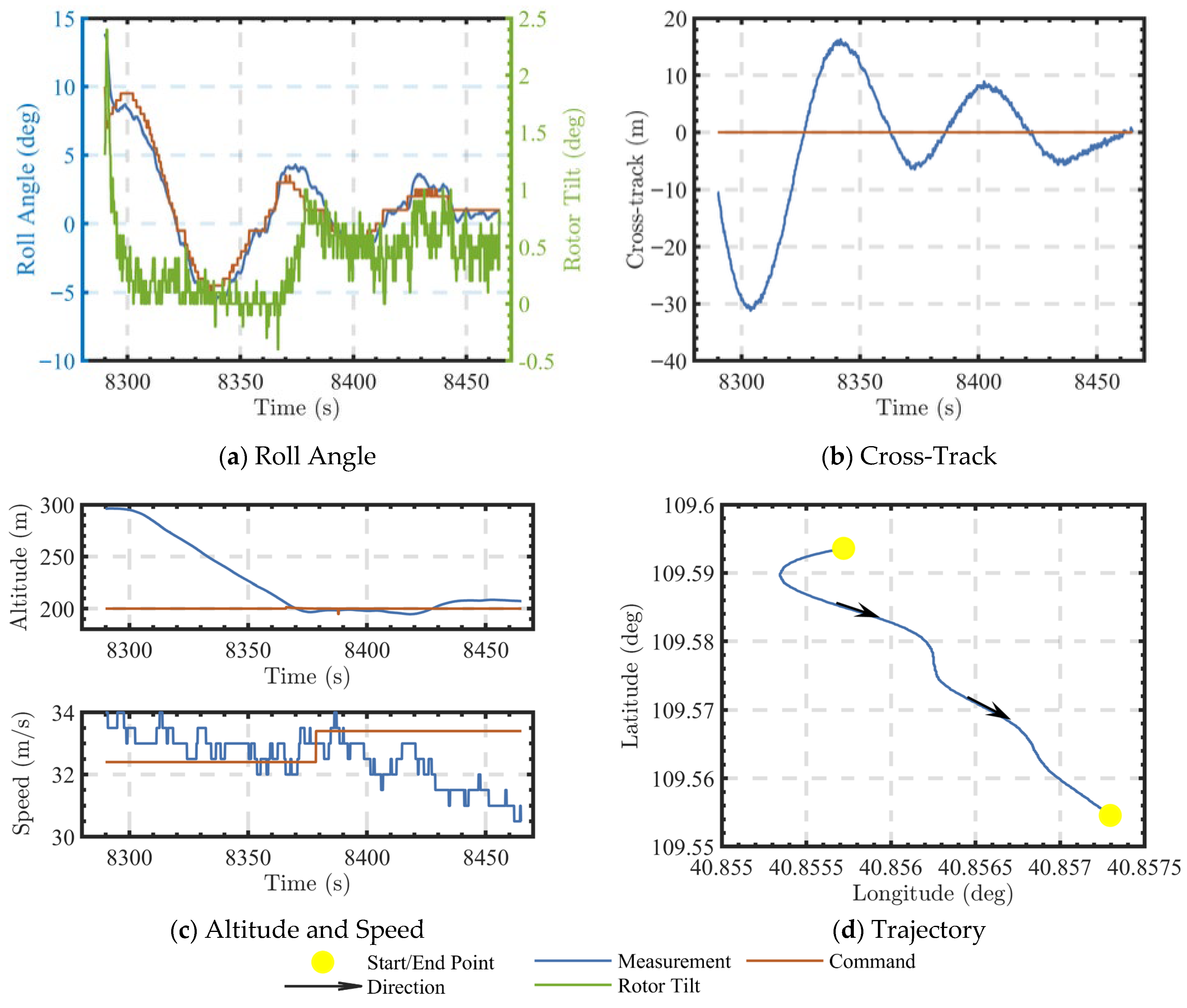

To address the unique flight characteristics of unmanned gyroplanes, a novel autonomous flight control system is proposed. The proposed control strategy achieves longitudinal-lateral decoupling under a single actuator, compensates for throttle-airspeed nonlinearities, and enhances airspeed control performance under delayed pitch dynamics through pitch-damping augmentation. This approach overcomes the limitations of conventional flight control frameworks when applied to unmanned gyroplane platforms and provides theoretical support for achieving efficient control of unmanned gyroplanes.

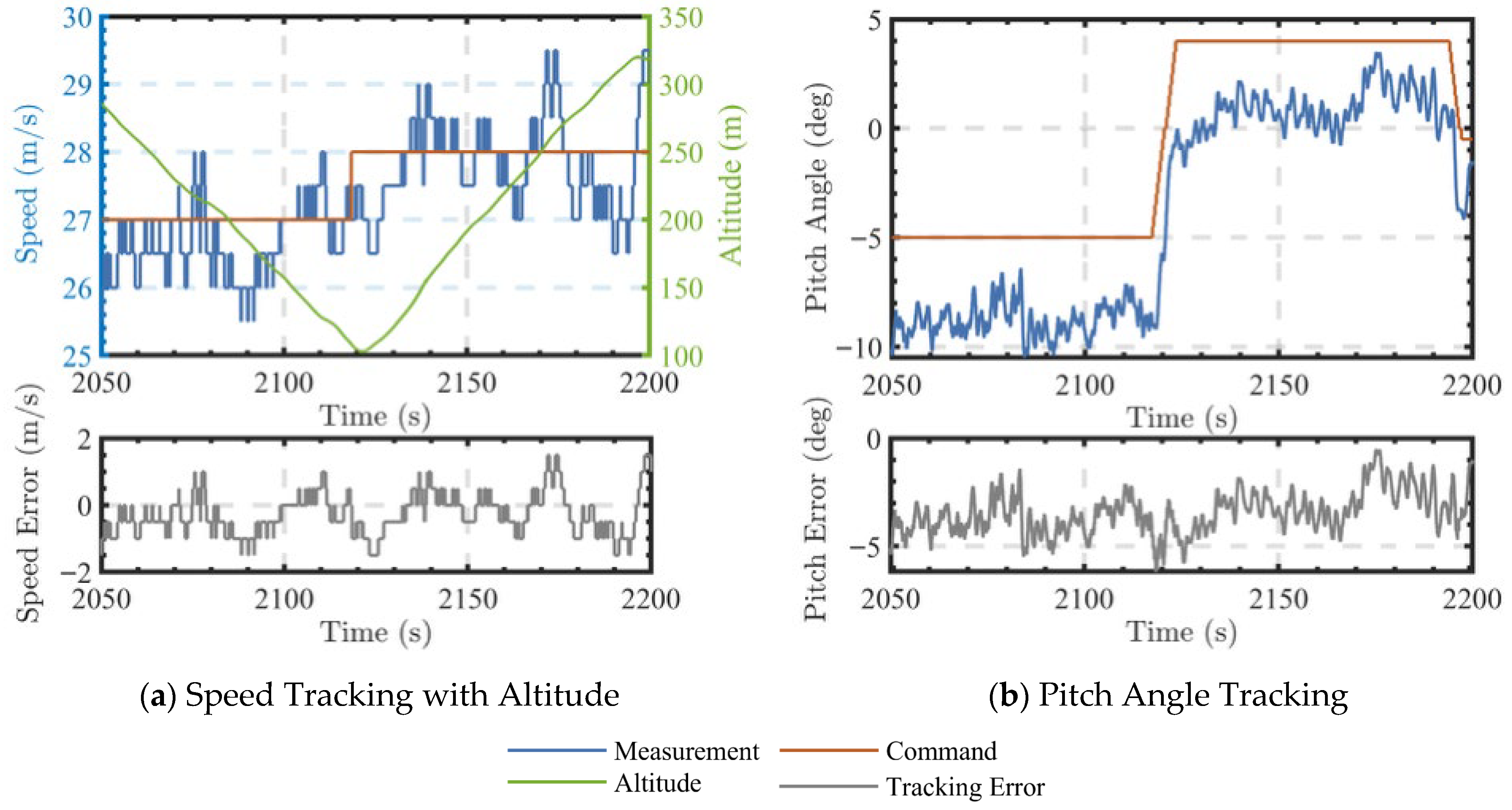

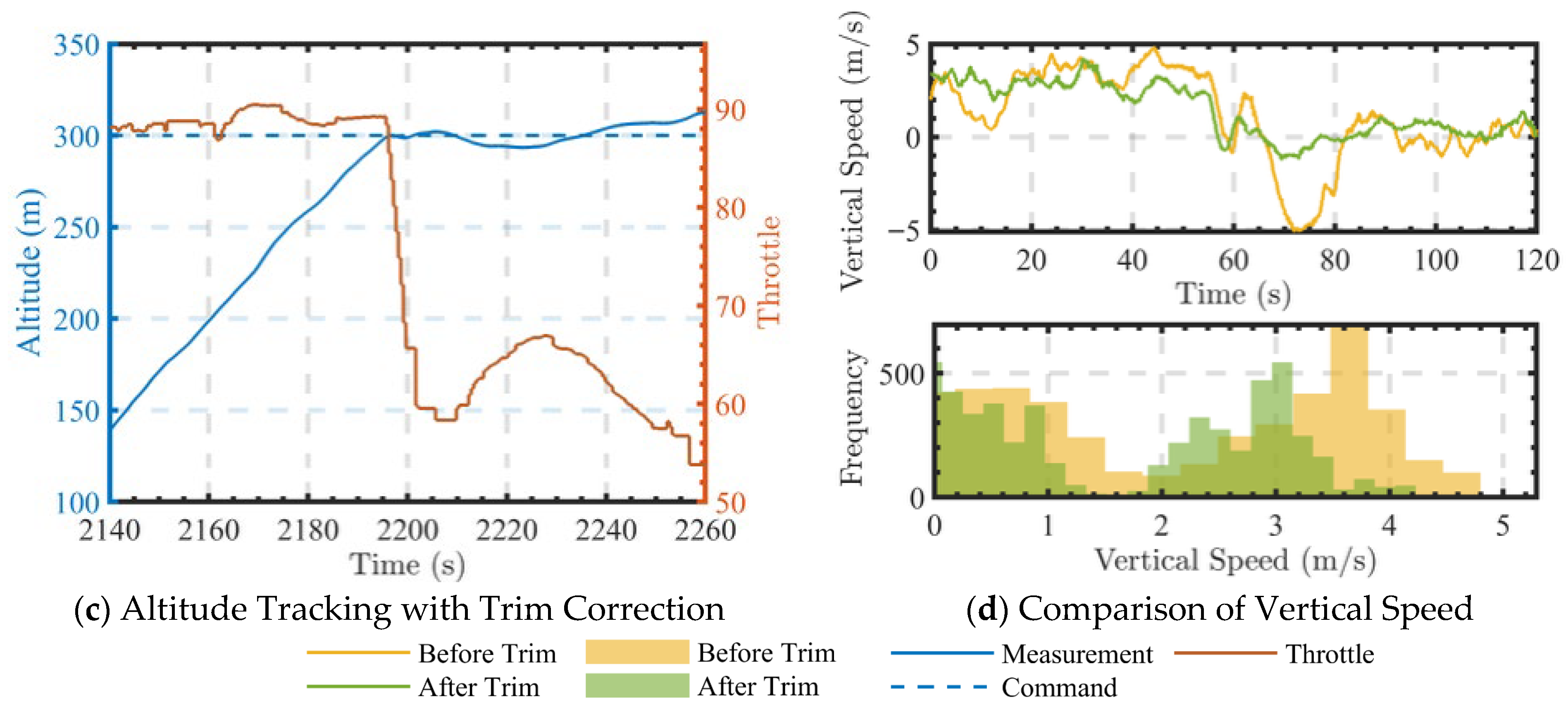

In terms of the practical aspect, the proposed autonomous flight control system was implemented on an unmanned gyroplane prototype converted from a manned platform. Flight tests showed a 40% improvement in climb rate stability with corrected throttle trim, and the airspeed tracking error remained within 1.5 m/s under dynamic conditions, demonstrating the effectiveness and practical applicability of the proposed control strategy. Notably, the high-precision airspeed control effectively prevents unmanned gyroplane stall, ensuring flight safety.

Overall, a comprehensive methodology for high-fidelity aerodynamic modeling and autonomous control of unmanned gyroplanes was established. Both theoretical and experimental results verified its effectiveness, providing a basis for future flight envelope expansion and performance improvements. Future work will focus on extending its applicability by incorporating transient coupling effects into the control framework and investigating the applicability of the total energy control system to the unique rotorcraft dynamics.