WA-LPA*: An Energy-Aware Path-Planning Algorithm for UAVs in Dynamic Wind Environments

Highlights

- Developed a wind-adaptive lifelong planning A* (WA-LPA*) algorithm that couples UAV energy modeling with dynamic wind-field perception to achieve energy-aware path optimization.

- Introduced a composite heuristic integrating wind-alignment and altitude-layer optimization, together with an adaptive replanning mechanism responsive to environ- mental changes.

- The proposed approach enables UAVs to maintain energy-efficient and stable flight performance under complex, time-varying wind conditions.

- This framework offers a practical foundation for real-world UAV deployment and provides methodological guidance for intelligent navigation in energy-constrained aerial systems.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Establishing a detailed energy consumption model for rotorcraft UAVs, which accurately describes the interaction mechanisms among power components under wind-field influences.

- Integrating physically accurate energy models into edge cost functions and designing composite heuristic functions that incorporate wind-field information, combined with a hierarchical height-aware optimization strategy for improved energy efficiency.

- Proposing a dynamic replanning decision algorithm based on wind-field change characteristics, which adaptively selects between global and local adjustment strategies to improve response efficiency.

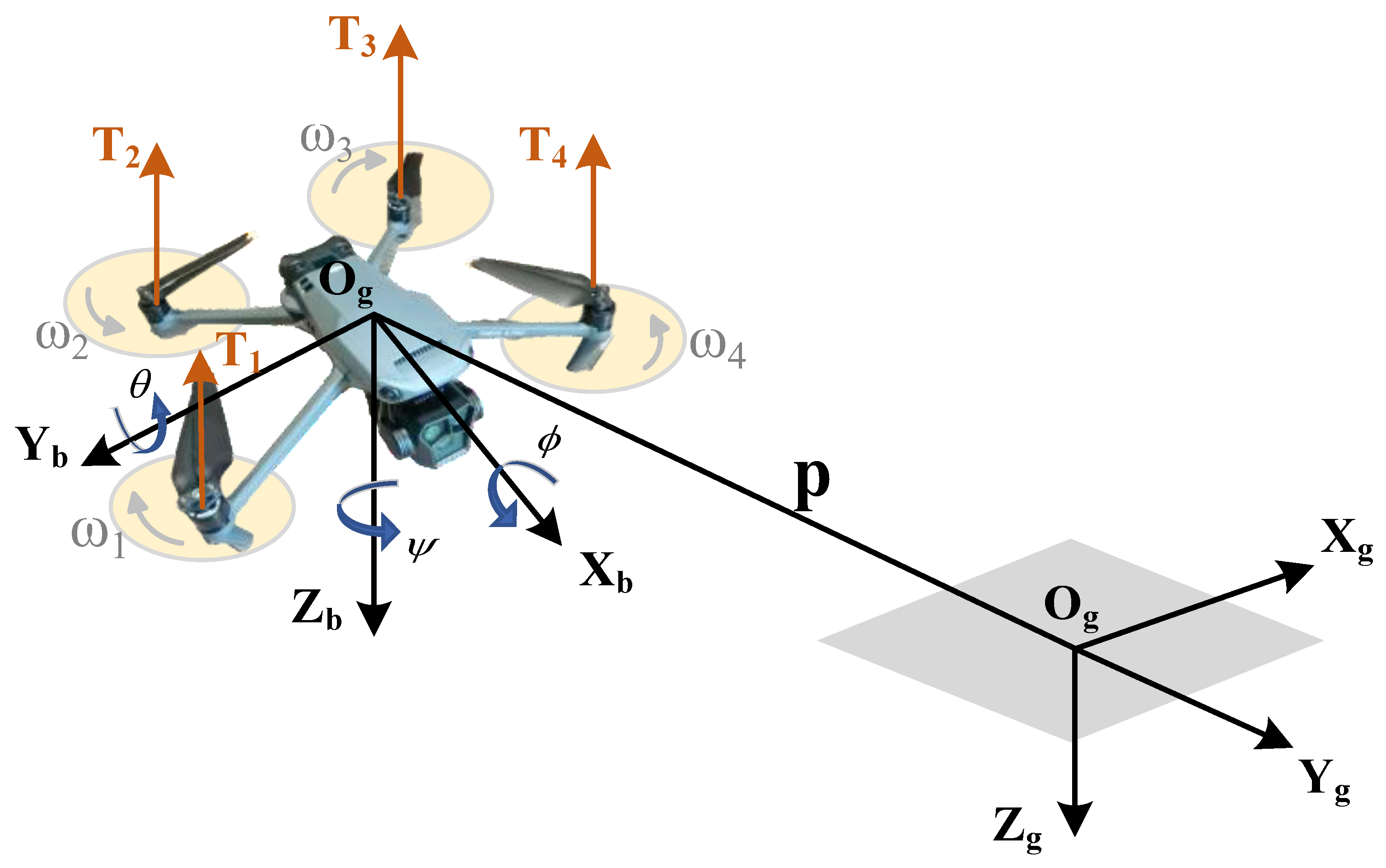

2. Problem Formulation and System Modeling

2.1. Problem Definition

2.2. Dynamic Wind-Field Modeling

2.3. Energy Consumption Modeling for Rotorcraft UAVs Under Wind Disturbances

3. Methodology

3.1. Wind-Adaptive LPA* Algorithm Framework

| Algorithm 1 Wind-Adaptive LPA* Algorithm |

| Require: Start , Goal , Environment Ensure: Optimal energy path

|

3.2. Physically Accurate Edge Cost Function

3.3. Wind-Aware Heuristic Function Design

3.4. Hierarchical Height-Aware Optimization Strategy

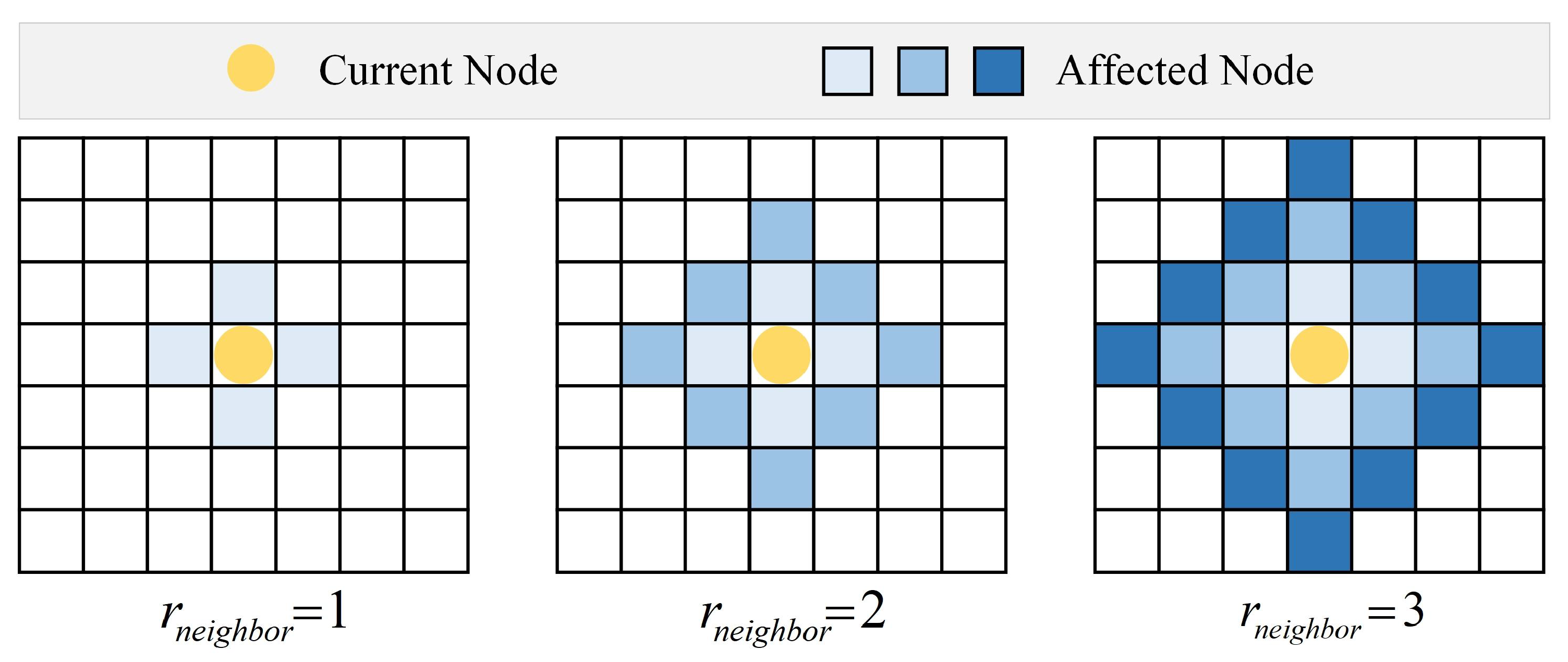

3.5. Dynamic Environment Adaptation Mechanisms

4. Experimental Evaluation

4.1. Simulation Setup

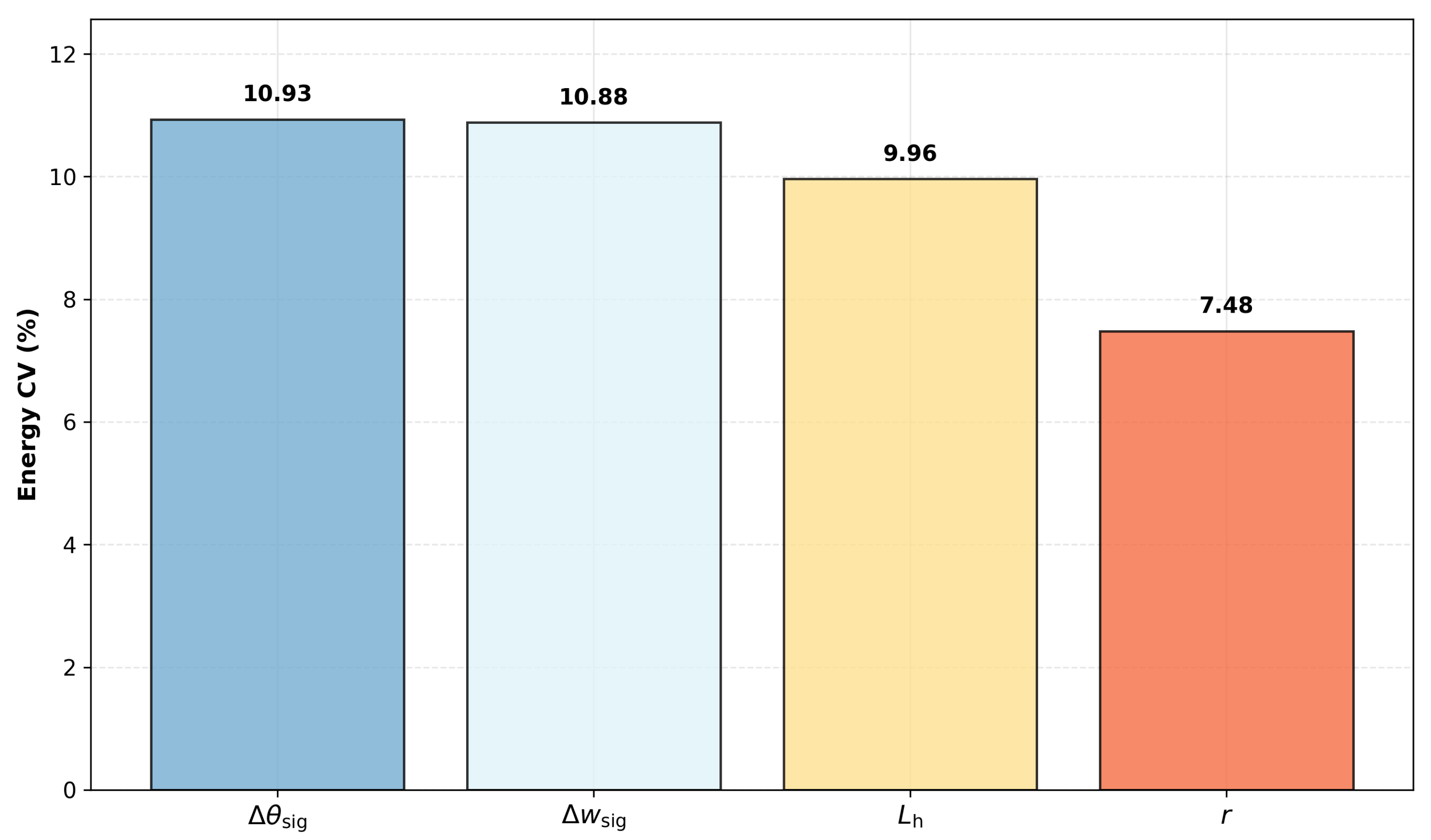

4.2. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

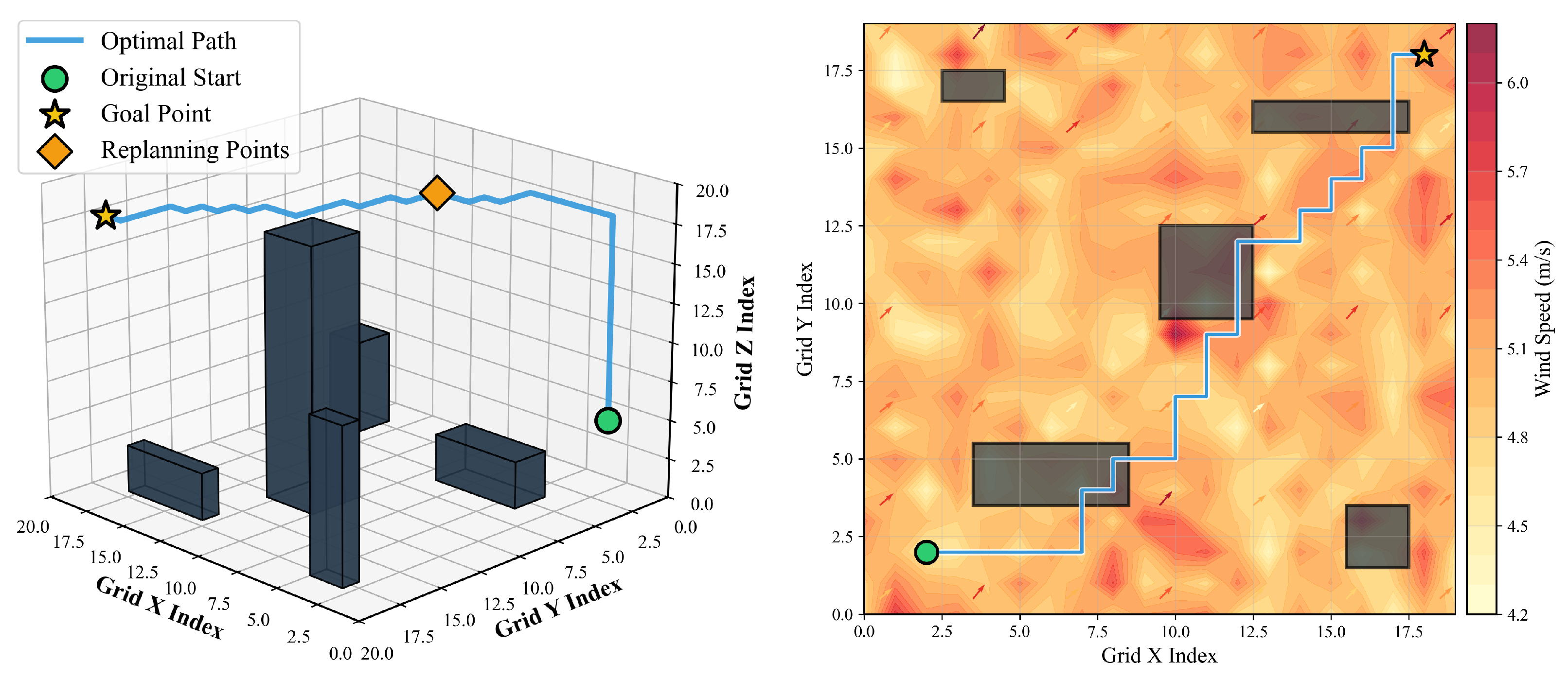

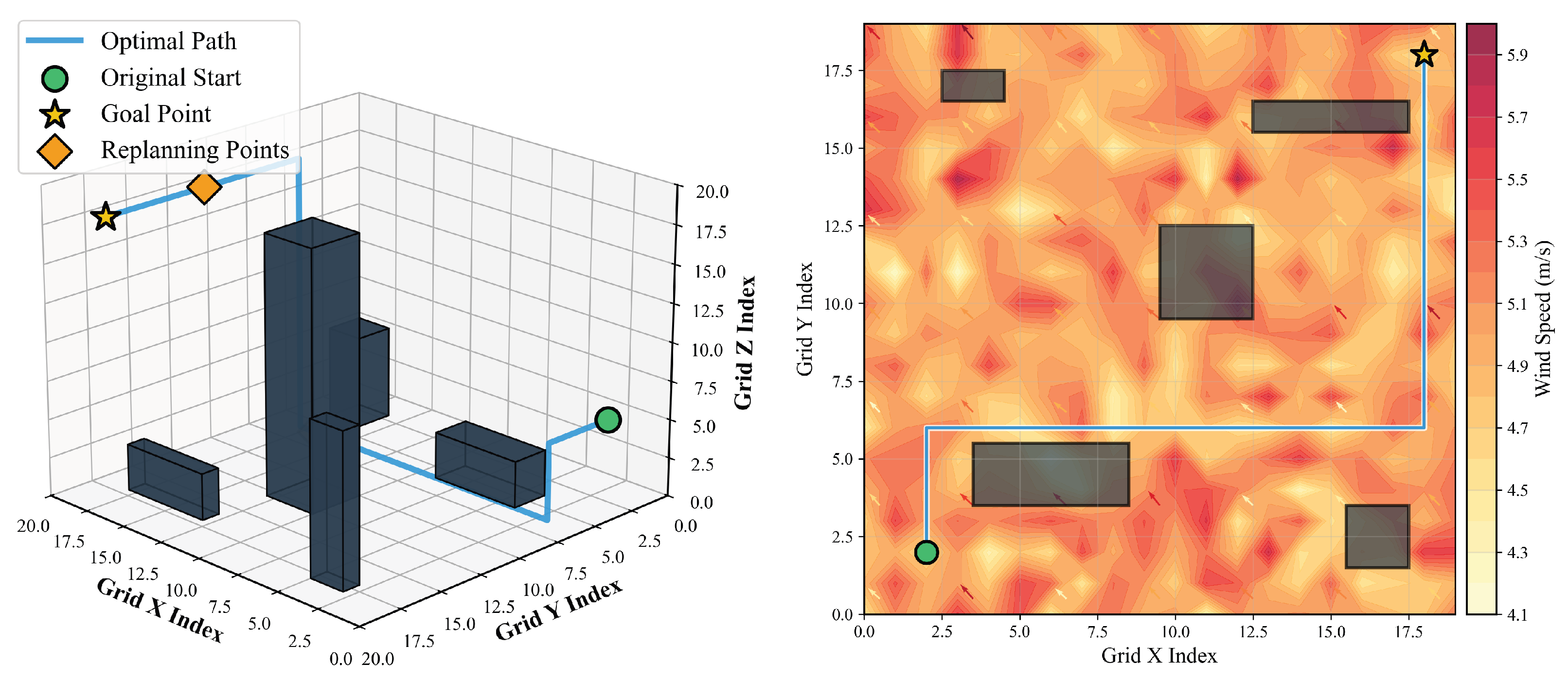

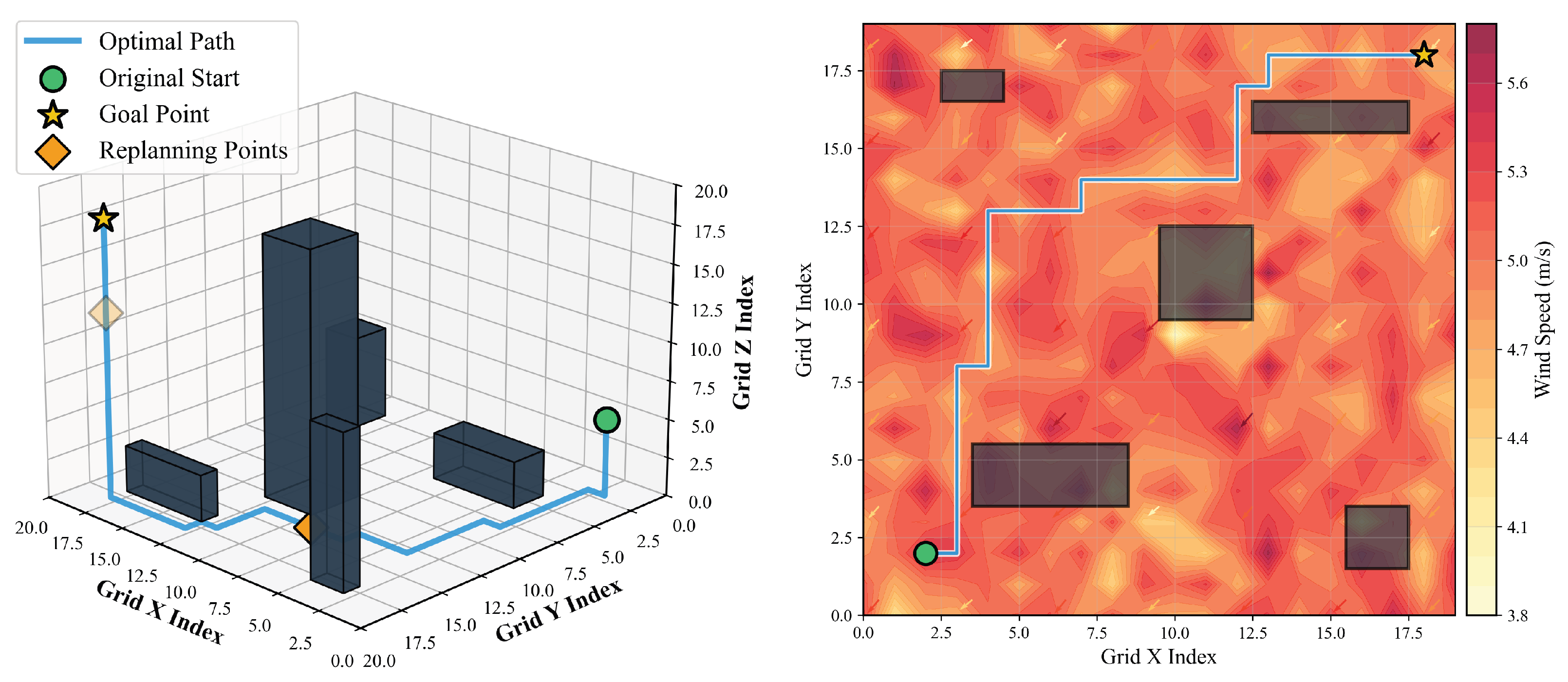

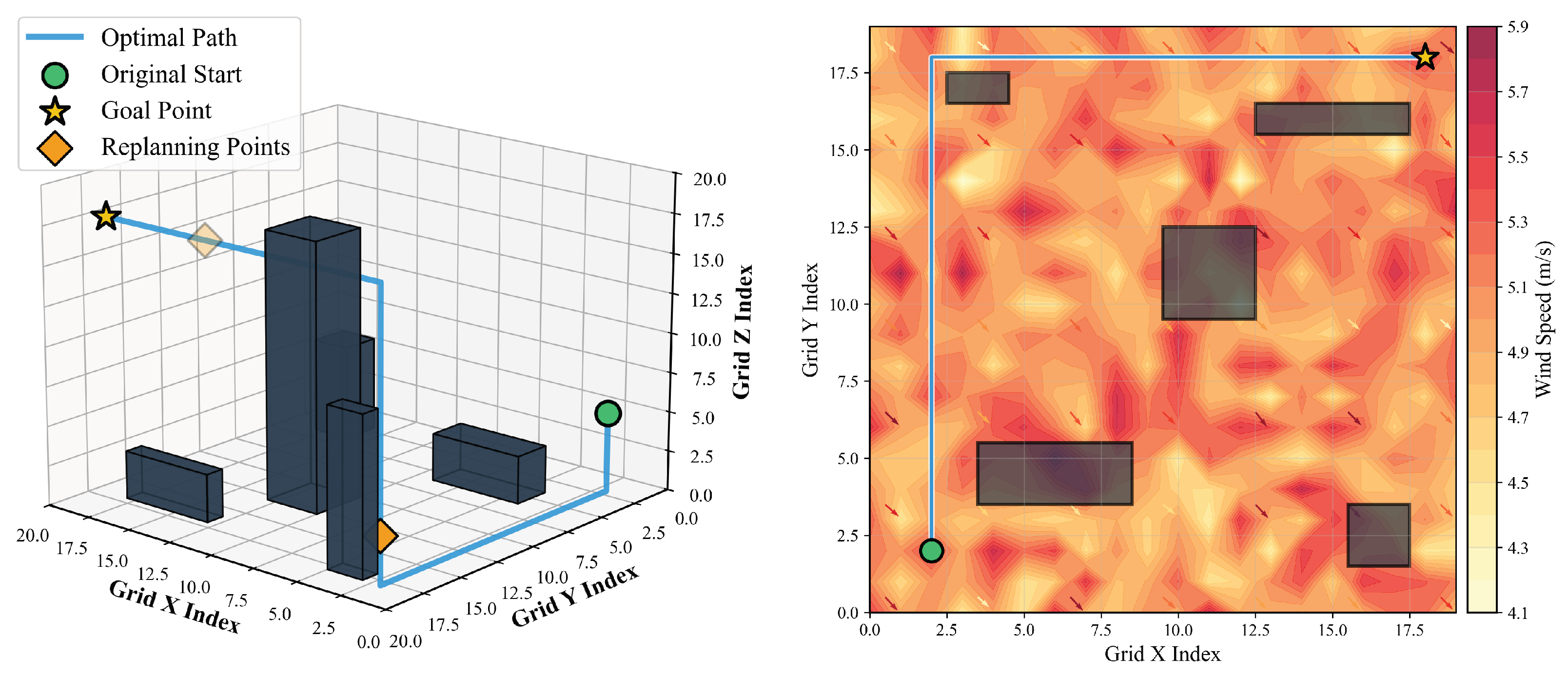

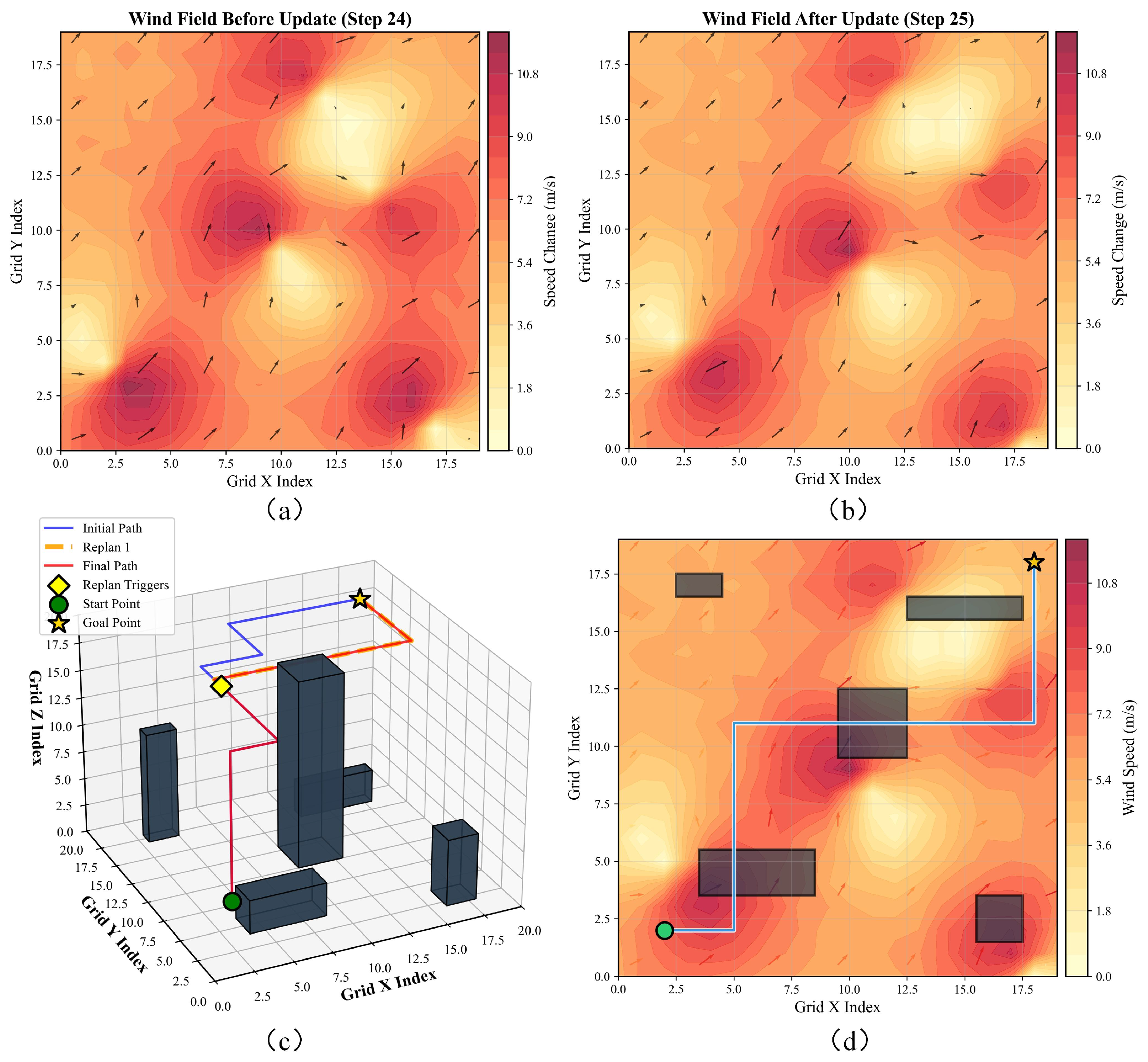

4.3. Wind-Field Adaptability Testing

4.4. Performance Comparison Experiments

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, X.; Wu, Q.; Zhou, K. Path optimization for UAV food delivery under extreme weather conditions with wind disturbance consideration. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 209, 111452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Yang, L.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Hou, W.; Xu, F. An Intelligent 5G Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Path Optimization Algorithm for Offshore Wind Farm Inspection. Drones 2024, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Miao, F.; Mei, X. Facilitating Multi-UAVs application for rescue in complex 3D sea wind offshore environment: A scalable Multi-UAVs collaborative path planning method based on improved coatis optimization algorithm. Ocean Eng. 2025, 324, 120701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Yan, X.; Han, Y. Multi-mechanism swarm optimization for multi-UAV task assignment and path planning in transmission line inspection under multi-wind field. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 150, 111033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Xiao, T.; Du, P.; Zhang, P.; Liu, K.; Tan, L. Improved PSO-Based Two-Phase Logistics UAV Path Planning Under Dynamic Demand and Wind Conditions. Drones 2024, 8, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, L.; Guo, H.; Hu, X. Advances in UAV Path Planning: A Comprehensive Review of Methods, Challenges, and Future Directions. Drones 2025, 9, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Huynh, D.; Do-Duy, T.; Nguyen, L.; Le, M.T.; Vo, N.S.; Duong, T. Real-Time Optimized Path Planning and Energy Consumption for Data Collection in Unmanned Aerial Vehicles-Aided Intelligent Wireless Sensing. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 2753–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombes, M.; Fletcher, T.; Chen, W.; Liu, C. Optimal Polygon Decomposition for UAV Survey Coverage Path Planning in Wind. Sensors 2018, 18, 2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.; Kim, Y. Flight dynamics of aerial vehicle considering time-varying ambient wind. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 126, 107601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Shi, Y.; Cao, H.; Garg, S.; Alrashoud, M.; Shukla, P. AI-Enabled Trajectory Optimization of Logistics UAVs with Wind Impacts in Smart Cities. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 70, 3885–3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, D.; Ali, Z.; Ting, B.; Wang, H. An overview of various kinds of wind effects on unmanned aerial vehicle. Meas. Control 2019, 52, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yan, L.; Han, Y.; Xie, H.; Zhao, Y. A Survey on the Key Technologies of UAV Motion Planning. Drones 2025, 9, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aradi, S. Survey of Deep Reinforcement Learning for Motion Planning of Autonomous Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 740–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewawasam, H.; Ibrahim, M.; Appuhamillage, G. Past, Present and Future of Path-Planning Algorithms for Mobile Robot Navigation in Dynamic Environments. IEEE Open J. Ind. Electron. Soc. 2022, 3, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P.; Nilsson, N.; Raphael, B. A Formal Basis for the Heuristic Determination of Minimum Cost Paths. IEEE Trans. Syst. Sci. Cybern. 1968, 4, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, E. A note on two problems in connexion with graphs. Numer. Math. 1959, 1, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaValle, S. Rapidly-Exploring Random Trees: A New Tool for Path Planning; The Annual Research Report; Iowa State University: Ames, IA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kavraki, L.; Svestka, P.; Latombe, J.C.; Overmars, M. Probabilistic roadmaps for path planning in high-dimensional configuration spaces. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 1996, 12, 566–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Z.; Xiong, G.; Liu, S. A Robot Path Planning Method Based on Improved Genetic Algorithm and Improved Dynamic Window Approach. Sustainability 2022, 15, 4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Yu, W.; Li, G.; Qin, G.; Luo, Y. Particle Swarm Algorithm Path-Planning Method for Mobile Robots Based on Artificial Potential Fields. Sensors 2022, 23, 6082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, W.; Wei, P.; Ying, L.; Liu, Y. Obstacle Avoidance for UAS in Continuous Action Space Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 90623–90634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubí, B.; Morcego, B.; Pérez, R. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Quadrotor Path Following and Obstacle Avoidance. In Deep Learning for Unmanned Systems; Koubaa, A., Azar, A., Eds.; Studies in Computational Intelligence, Volume 984; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Jia, Y.; Qin, Q.; Xu, L.; Zhou, Y. Integrating just-in-time expansion primitives and an adaptive variable-step-size mechanism for feasible path planning of fixed-wing UAVs. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2025, 38, 103566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, R.; Zhao, Y.; Ren, X. Integrating wind field analysis in UAV path planning: Enhancing safety and energy efficiency for urban logistics. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2025, 39, 103605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.; Ng, K.; Lee, C.; Hsu, L.; Keung, K. Wind dynamic and energy-efficiency path planning for unmanned aerial vehicles in the lower-level airspace and urban air mobility context. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 57, 103202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Liu, R. Efficient multi-UAV path planning in dynamic and complex environments using hybrid polar lights optimization. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2025, 37, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Jing, F.; Gao, M. A Dynamic Path Planning Method for UAVs Based on Improved Informed-RRT* Fused Dynamic Windows. Drones 2024, 8, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Peng, X.G.; Lei, X.K.; Wang, H.D.; Jin, Y.C. Knowledge-assisted evolutionary task scheduling for hierarchical multiagent systems with transferable surrogates. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2025, 98, 102107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Xu, X.X.; Zheng, M.Y.; Zhan, Z.H. Evolutionary computation for unmanned aerial vehicle path planning: A survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Rathinam, S.; Likhachev, M.; Choset, H. Multi-Objective Path-Based D* Lite. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 3318–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semiz, F.; Polat, F. Incremental multi-agent path finding. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2021, 116, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stentz, A. Optimal and Efficient Path Planning for Partially-known Environments. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, San Diego, CA, USA, 8–13 May 1994; pp. 3310–3317. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, S.; Likhachev, M.; Furcy, D. Lifelong Planning A*. Artif. Intell. 2004, 155, 93–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Srinivasa, S.; Tsiotras, P. Lazy Lifelong Planning for Efficient Replanning in Graphs with Expensive Edge Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Kyoto, Japan, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 8778–8783. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Han, Q.; Feng, S.; Wang, Z.; Meng, T.; Yang, J. Improvement and Fusion of D* Lite Algorithm and Dynamic Window Approach for Path Planning in Complex Environments. Machines 2024, 12, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Yang, H.; Ma, J.; Xiong, K.; Hu, Q. An Improved D* Lite-Based Dynamic Route Planning Algorithm for Ships in Arctic Waters. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, S.; Koval, A.; Kanellakis, C.; Nikolakopoulos, G. D*+: A Risk Aware Platform Agnostic Heterogeneous Path Planner. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.05563. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Zhan, Z.; Wang, Z. Energy-consumption model for rotary-wing drones. J. Field Robot. 2024, 41, 1940–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.; Coelho, A.; Campos, R. SUPPLY: Sustainable Multi-UAV Performance-Aware Placement Algorithm for Flying Networks. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 159445–159461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, R. Energy Minimization for Wireless Communication with Rotary-Wing UAV. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2019, 18, 2329–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monin, A.; Obukhov, A. Basic Laws of Turbulent Mixing in the Surface Layer of the Atmosphere. Tr. Geofiz. Instituta Akad. Nauk. 1954, 24, 163–187. [Google Scholar]

- Wyngaard, J.; Coté, O.; Izumi, Y. Local Free Convection, Similarity and the Budgets of Shear Stress and Heat Flux. J. Atmos. Sci. 1971, 28, 1171–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Value |

|---|---|---|

| Mass | m | 0.92 kg |

| Ground speed | 15 m/s | |

| Gravitational acceleration | g | 9.81 m/s2 |

| Air density | 1.225 kg/m3 | |

| Number of rotors | 4 | |

| Rotor radius | r | 0.12 m |

| Equivalent frontal area | A | 0.06 m2 |

| Thrust coefficient | 0.0180 | |

| Torque coefficient | 0.0016 | |

| Profile drag coefficient | 0.015 | |

| Average blade drag coefficient | 0.5 | |

| Propeller efficiency | 0.78 | |

| Motor efficiency | 0.82 | |

| Controller efficiency | 0.92 | |

| Electronic power | 6 W |

| Parameter | Value | Planning Time (s) | Energy Consumption (J) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (∘) | 45 | 14.85 ± 2.42 | 328.6 ± 48.2 |

| 90 | 12.73 ± 2.18 | 335.4 ± 40.1 | |

| 135 | 11.54 ± 2.05 | 361.8 ± 42.5 | |

| 180 † | 10.67 ± 1.92 | 415.3 ± 33.7 | |

| (m/s) | 4.0 | 14.85 ± 2.42 | 331.5 ± 49.8 |

| 6.0 | 12.73 ± 2.18 | 357.2 ± 45.4 | |

| 9.0 | 11.54 ± 2.05 | 362.1 ± 42.8 | |

| 10.0 † | 10.67 ± 2.92 | 415.3 ± 33.7 | |

| 12.0 | 9.24 ± 2.86 | 428.7 ± 29.1 | |

| (steps) | 5 | 9.52 ± 1.58 | 430.9 ± 51.6 |

| 10 | 10.08 ± 2.21 | 422.7 ± 44.2 | |

| 15 † | 10.67 ± 2.92 | 415.3 ± 33.7 | |

| 20 | 13.83 ± 3.01 | 363.4 ± 31.5 | |

| 25 | 15.51 ± 3.08 | 342.8 ± 28.9 | |

| r (steps) | 1 † | 10.67 ± 1.92 | 415.3 ± 33.7 |

| 2 | 12.24 ± 2.12 | 362.8 ± 41.1 | |

| 3 | 14.81 ± 2.36 | 359.5 ± 42.8 | |

| 4 | 17.02 ± 2.65 | 351.2 ± 41.7 | |

| 5 | 19.15 ± 2.73 | 347.9 ± 41.3 |

| Scenario | Path Length (m) | Energy Consumption (J) | Energy Efficiency (m/J) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1613.0 | 28,306.9 | 17.549 | |

| 1623.0 | 28,306.9 | 22.751 | |

| 1623.0 | 44,444.5 | 27.384 | |

| 1623.0 | 36,994.5 | 22.794 |

| Scenario | Initial Path Length (m) | Initial Path Energy (J) | Replanning Times | Final Path Length (m) | Final Path Energy (J) | Energy Savings (J) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1613 | 26,269.9 | 1 | 1613 | 25,621.2 | 648.7 |

| 2 | 1613 | 28,317.8 | 1 | 1613 | 28,197.3 | 120.5 |

| 3 | 1613 | 32,368.6 | 1 | 1613 | 32,220.9 | 147.7 |

| 4 | 1629 | 42,059.9 | 2 | 1629 | 39,624.8 | 2385.2 |

| 5 | 1637 | 41,261.3 | 2 | 1623 | 37,523.1 | 3738.2 |

| Algorithm | Planning Time (s) | Path Steps | Path Length (m) | Energy Consumption (J) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional A* | 46 | 34,299.0 | ||

| Standard LPA* | 46 | 33,633.3 | ||

| WA-LPA* | 56 | 31,282.7 |

| Algorithm | Planning Time (s) | Path Steps | Path Length (m) | Energy Consumption (J) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional A* | 46 | 51,276.2 | ||

| Standard LPA* | 46 | 43,943.6 | ||

| WA-LPA* | 70 | 36,181.5 |

| Algorithm | Planning Time (s) | Path Steps | Path Length (m) | Energy Consumption (J) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional A* | 21 | Failed | ||

| Standard LPA* | 46 | 35,847.1 | ||

| WA-LPA* | 56 | 33,724.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lian, F.; Li, B.; Yang, Q.; Zhu, H.; Du, D. WA-LPA*: An Energy-Aware Path-Planning Algorithm for UAVs in Dynamic Wind Environments. Drones 2025, 9, 850. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120850

Lian F, Li B, Yang Q, Zhu H, Du D. WA-LPA*: An Energy-Aware Path-Planning Algorithm for UAVs in Dynamic Wind Environments. Drones. 2025; 9(12):850. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120850

Chicago/Turabian StyleLian, Fangjia, Bangjie Li, Qisong Yang, Hongwei Zhu, and Desong Du. 2025. "WA-LPA*: An Energy-Aware Path-Planning Algorithm for UAVs in Dynamic Wind Environments" Drones 9, no. 12: 850. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120850

APA StyleLian, F., Li, B., Yang, Q., Zhu, H., & Du, D. (2025). WA-LPA*: An Energy-Aware Path-Planning Algorithm for UAVs in Dynamic Wind Environments. Drones, 9(12), 850. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120850