Design and Autonomous Flight Demonstration of a Low-Cost Cardboard-Based UAV

Highlights

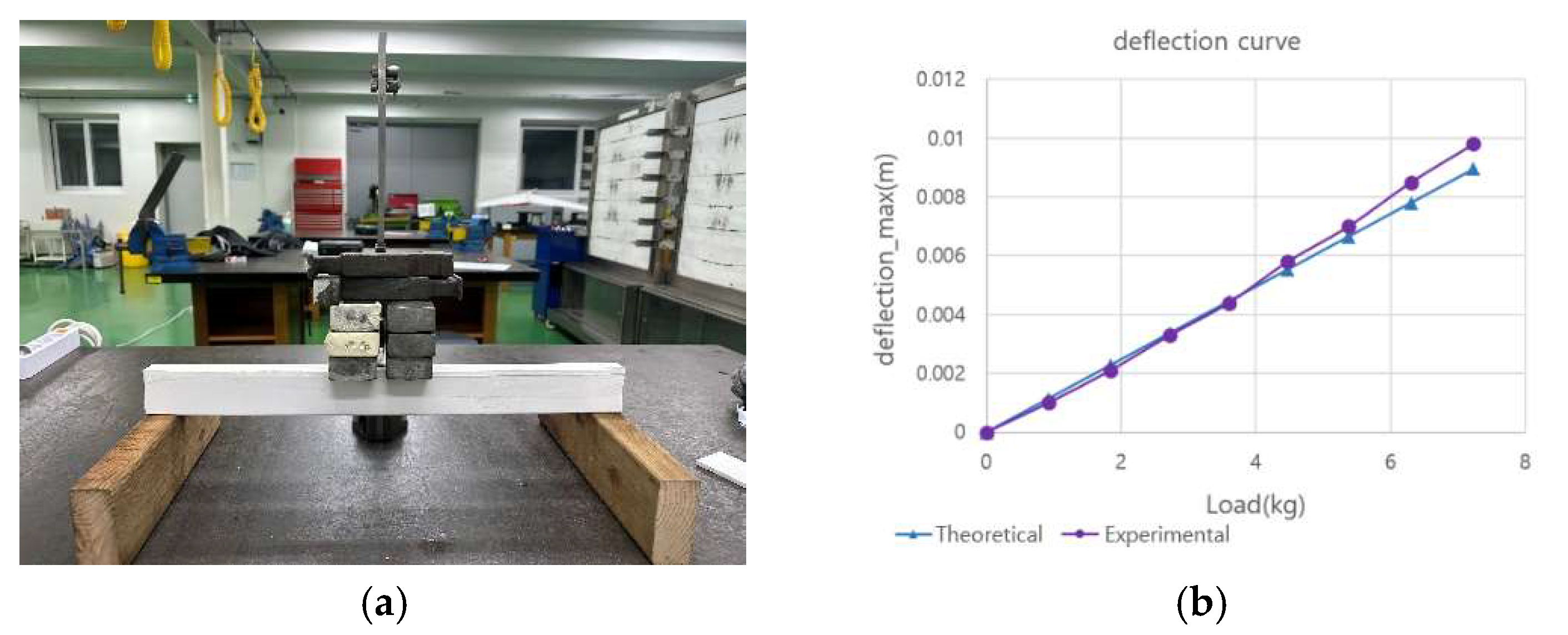

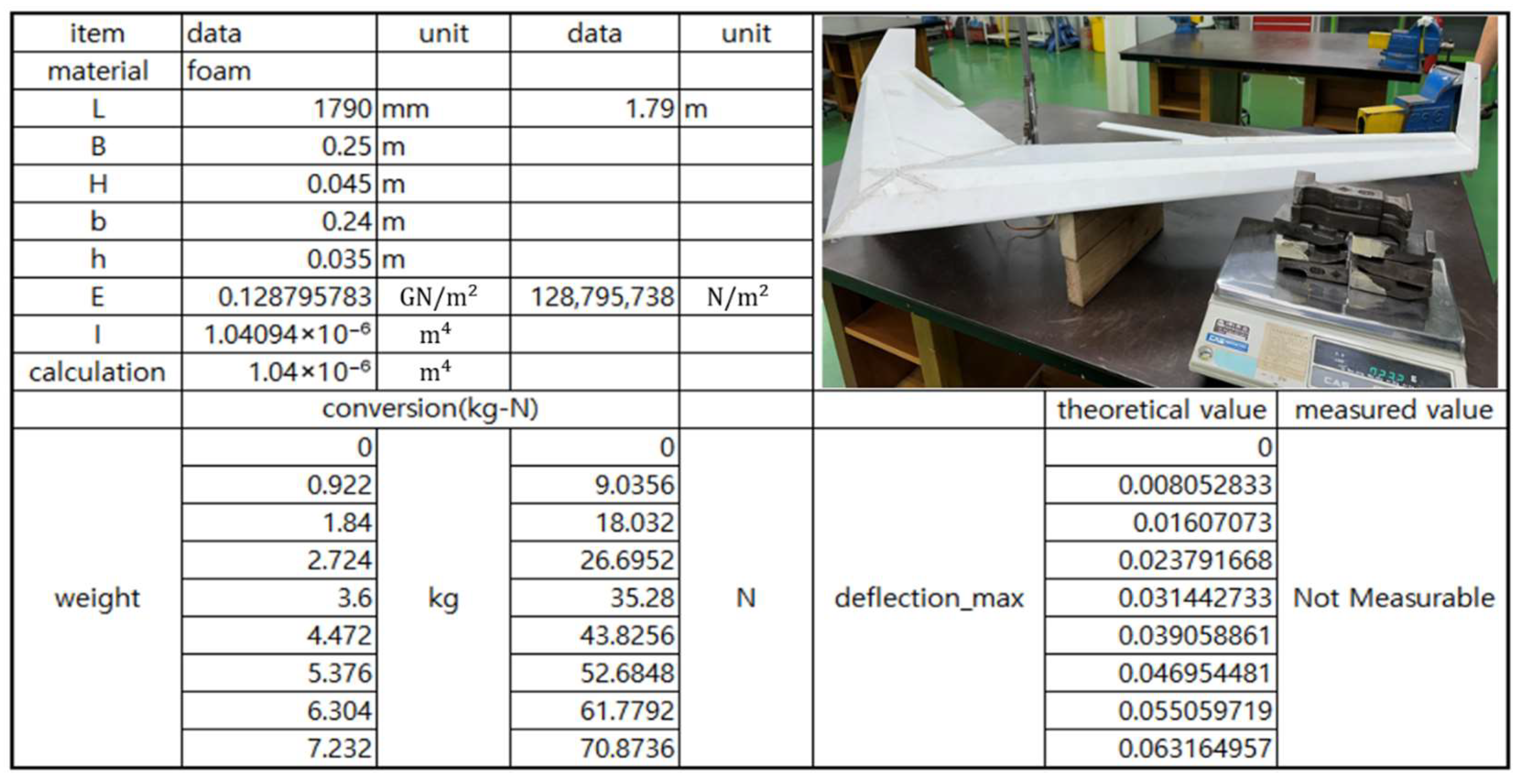

- The cardboard-based UAV structure sustained the 7.2 kgf design load with strong agreement between experimental results and analytical predictions.

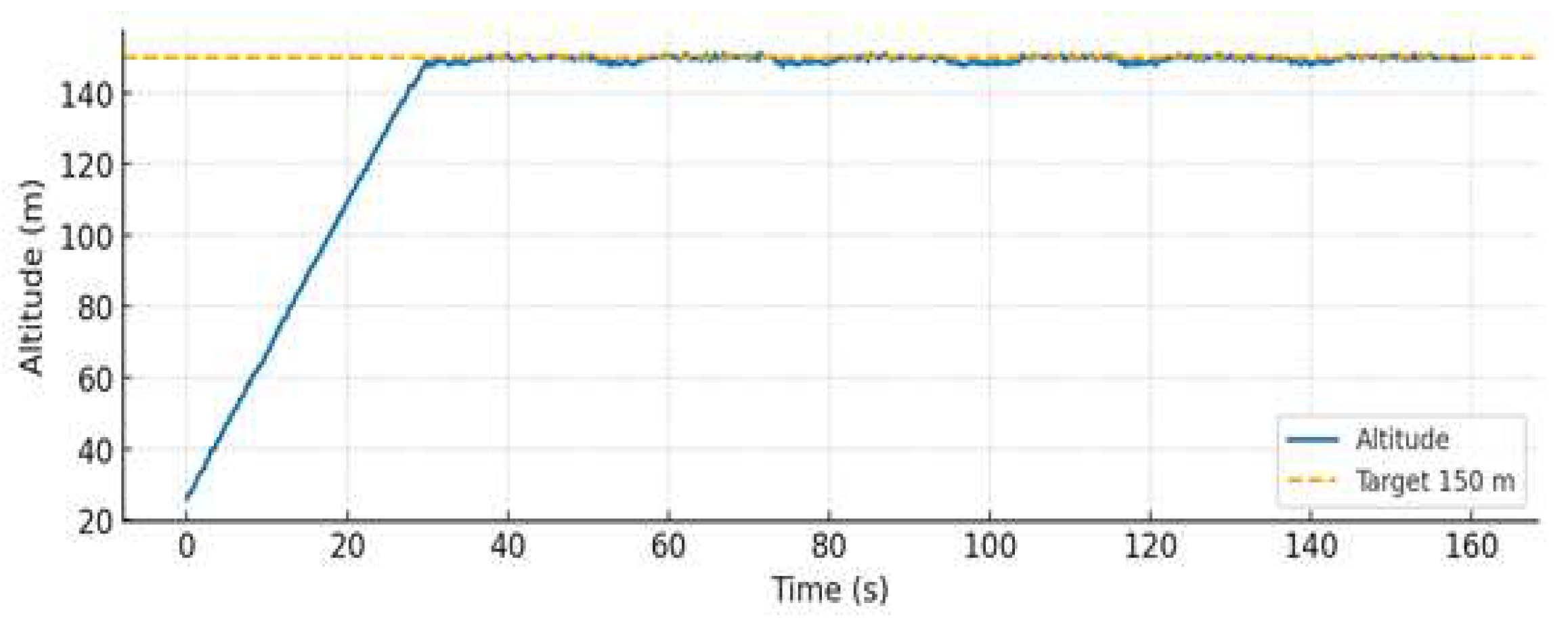

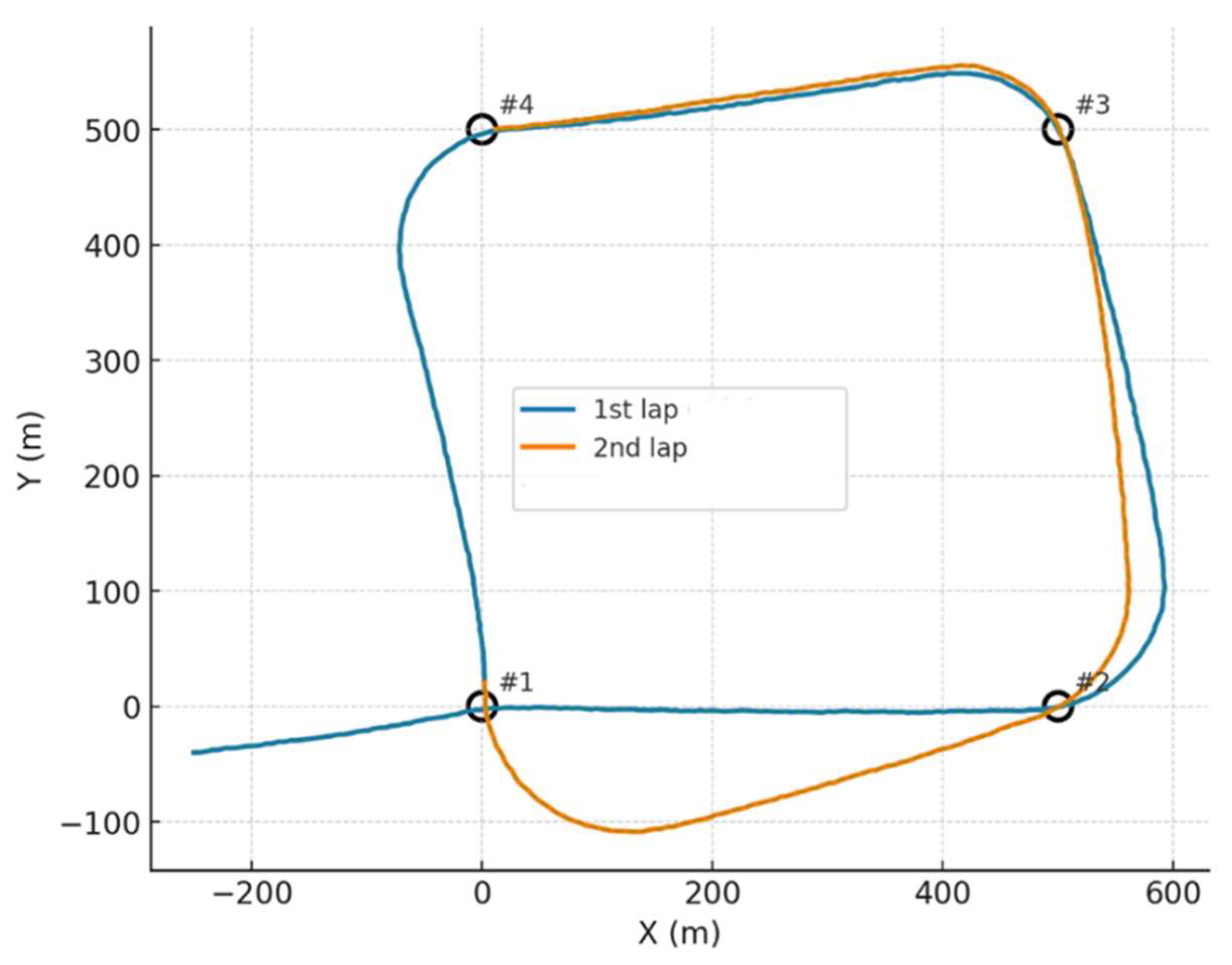

- The custom low-cost avionics (FCC + AHRS) enabled stable autonomous flight, achieving altitude accuracy within ±2 m and path-following errors of approximately ±3 m.

- The proposed platform provides an accessible and low-cost UAV solution for education, rapid prototyping, and research environments.

- It offers a scalable and expendable alternative for disaster response and rapid deployment missions requiring cost-efficiency and operational simplicity.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- a structural test of a cardboard box-type spar to evaluate its stiffness and strength under design loads,

- (ii)

- the development and utilization of a centrifugal acceleration testing apparatus to assess the accuracy of a low-cost inertial sensor, and

- (iii)

- the design and implementation of a custom, low-cost avionics system, including an in-house flight control computer (FCC) and attitude and heading reference system (AHRS), to realize autonomous flight control.

2. Methods

2.1. Design Requirements and Sizing

| Item | Value | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Endurance | Mission | |

| Max speed | 80 km/h (22.2 m/s) | Mission/performance |

| Payload | 1.0 kg | Maximum allowable mission equipment mass (e.g., camera, telemetry module); excludes airframe and propulsion system |

| Structure mass | 2.0 kg | The structure mass of 2.0 kg was derived from a subsystem-level breakdown covering the airframe, propulsion hardware, control mechanisms, avionics, and miscellaneous components (see Table 2). |

| 3.0 kg (W = 29.43 N) | Assumed | |

| Safety factor | 1.2 | Structural |

| Load factor | 2.0 | Structural |

| Stall speed | 10 m/s | Sizing |

| 1.2 | Sizing (conservative) | |

| Air density | 1.225 kg/m3 | Sea level |

| Span | 1.79 m | Given |

| LE sweep | 30 deg | Wing setup |

| Taper ratio | 0.5 | Assumed |

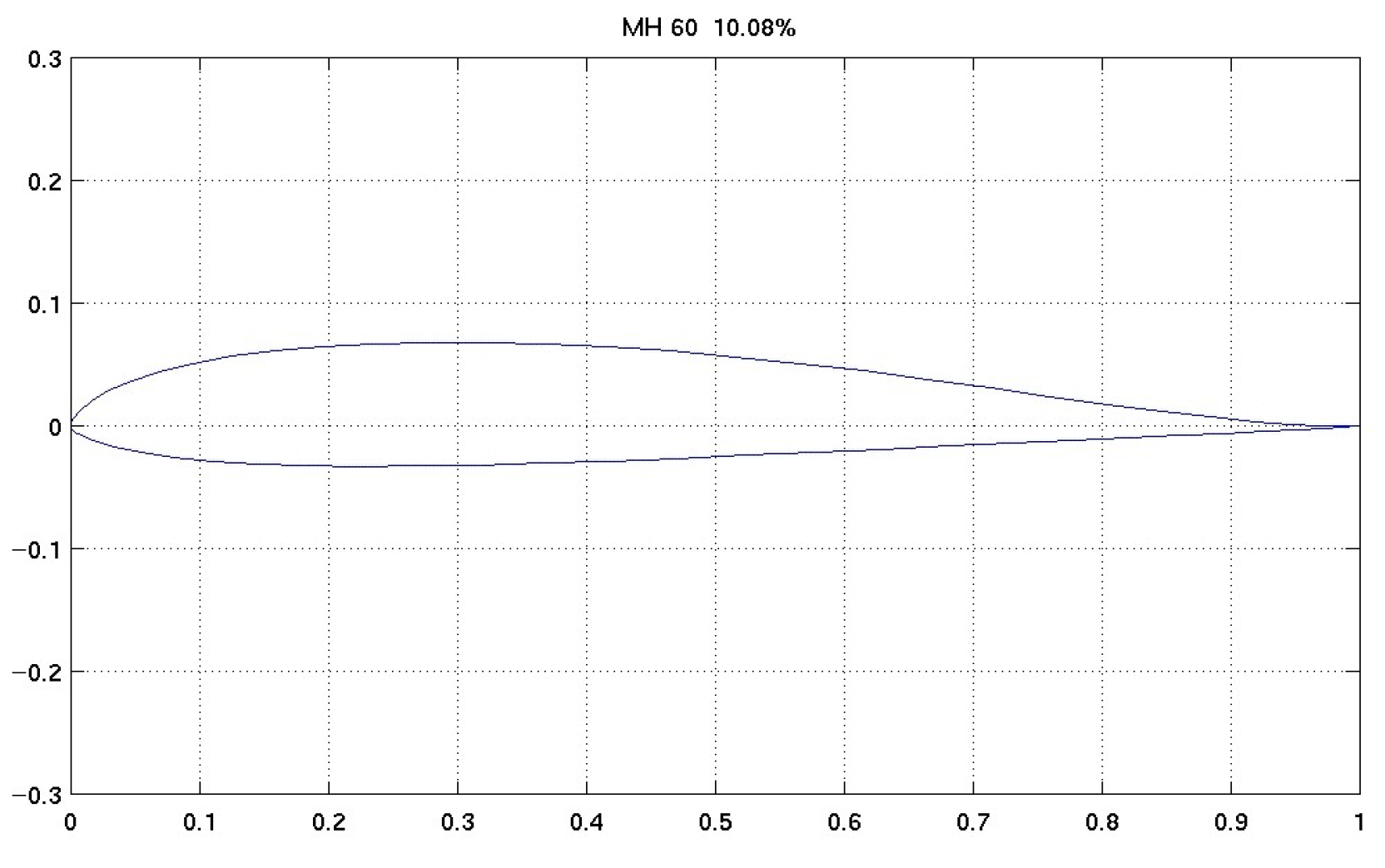

| Airfoil | MH60 (≈10%) | Reflex, tailless use |

| Subsystem | Mass [kg] | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Airframe structure | 1.20 | Wing, fuselage, tail, internal reinforcements |

| Propulsion components | 0.40 | Motor, ESC, propeller, power wiring |

| Control mechanisms | 0.15 | Flight-control computer (FCC), IMU, receiver, power PCB, wiring harness |

| Miscellaneous | 0.05 | Adhesives, tape, small mounts |

| Total | 2.00 kg | Matches structural mass input in Table 1 |

- (1)

- Wing sizing under the stall constraint

- (2)

- Airfoil selection (MH60, low-Re performance)

- (3)

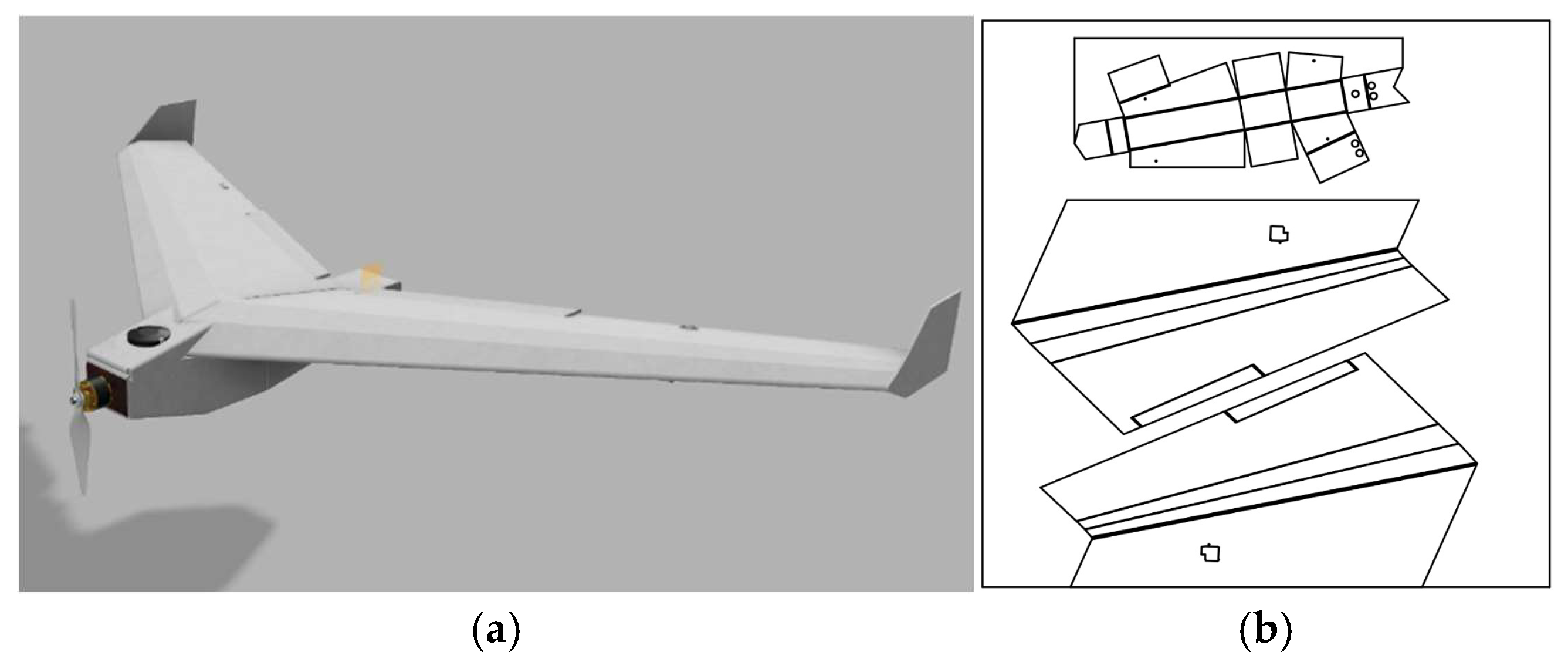

- Wing-tip vertical fins (directional stability)

2.1.1. Cost Considerations

2.1.2. Estimated Maximum Level-Flight Speed

2.2. Structural Design and Testing

2.2.1. Objective

2.2.2. Specimens, Setup, and Measurements

2.2.3. Experimental Validation Under Sweepback Constraint

- (1)

- Short-spar test and formula verification.

- (2)

- Partial-wing deflection measurement and rationality assessment.

- (3)

- Full-span deflection prediction.

2.2.4. Results and Discussion

3. Avionics System Design and Development

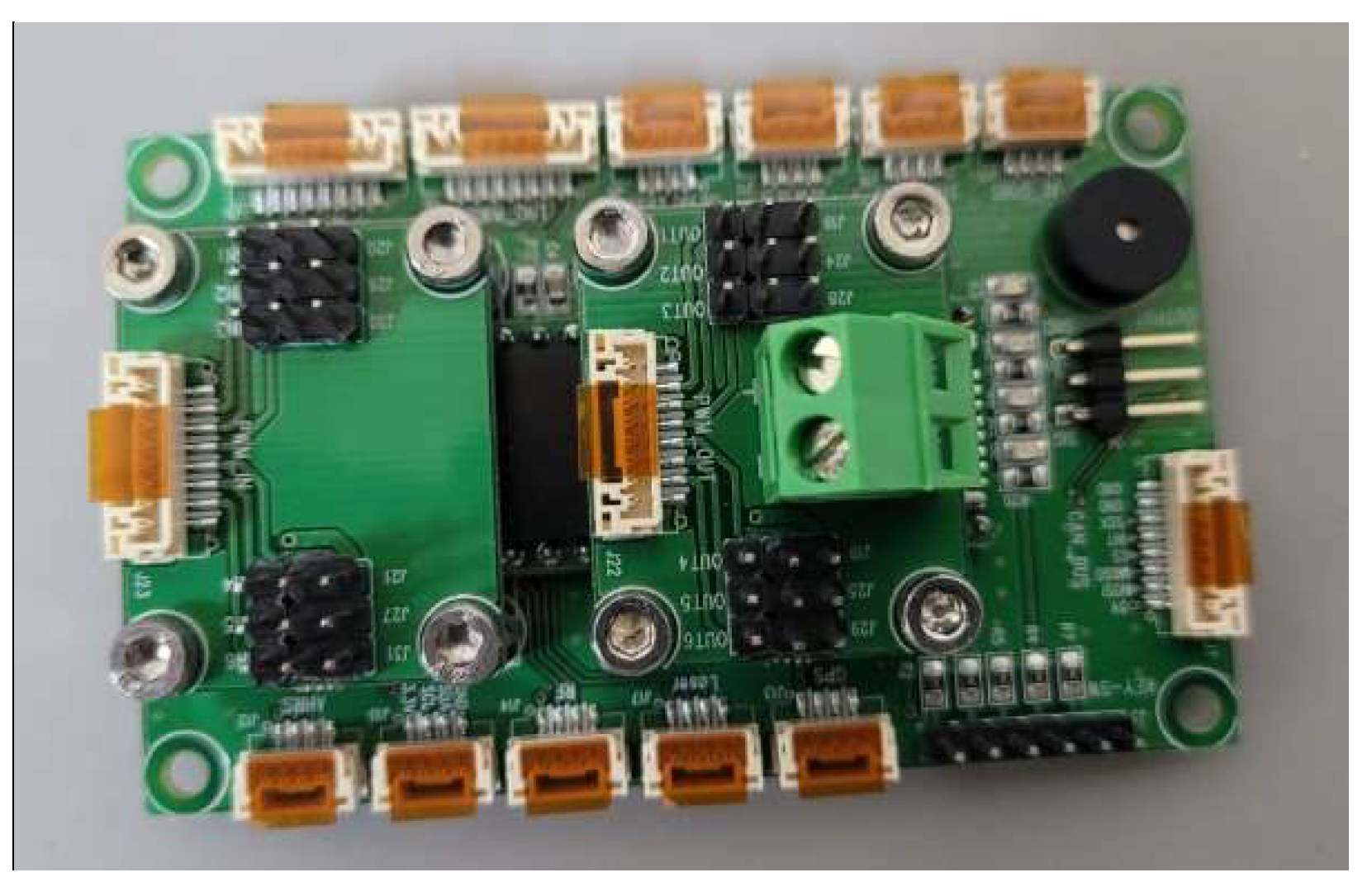

3.1. Flight Control Computer (FCC) Development

3.2. Application and Limitations of a Low-Cost AHRS

3.3. Rotational Simulation and Validation of AHRS Performance

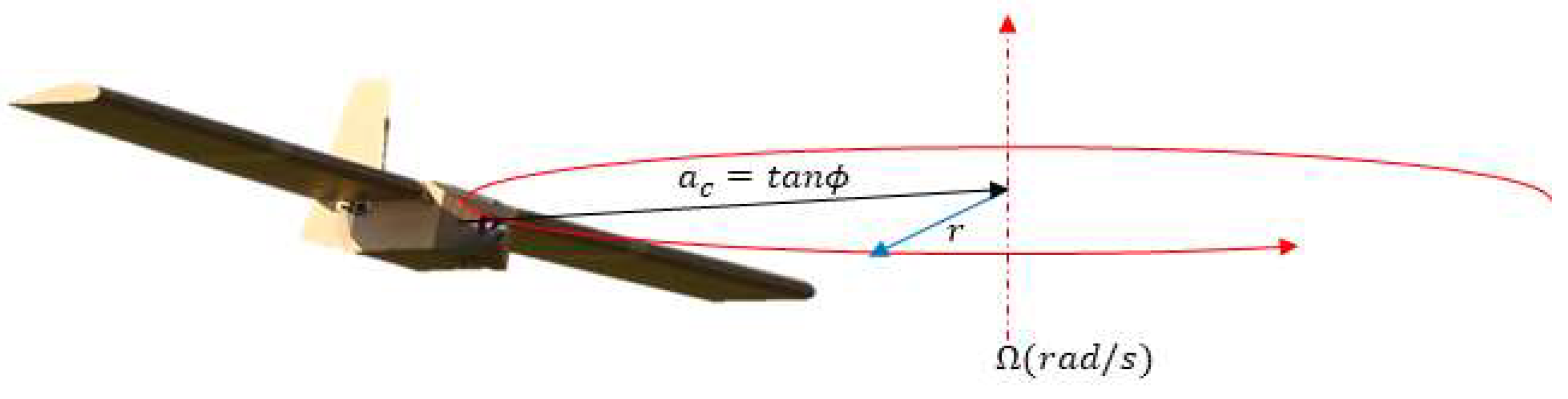

3.3.1. Theoretical Background of Steady Turn

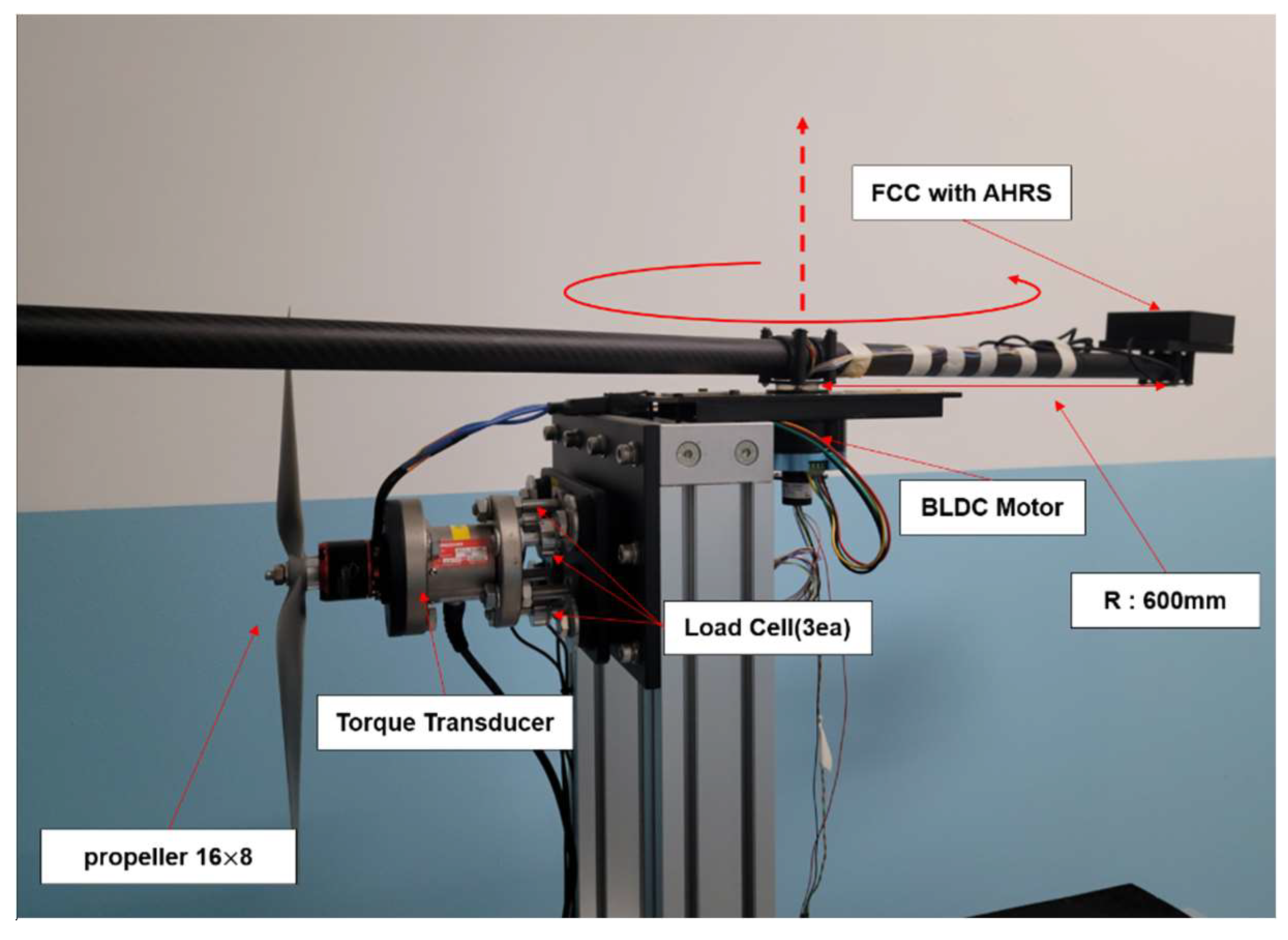

3.3.2. Experimental Setup

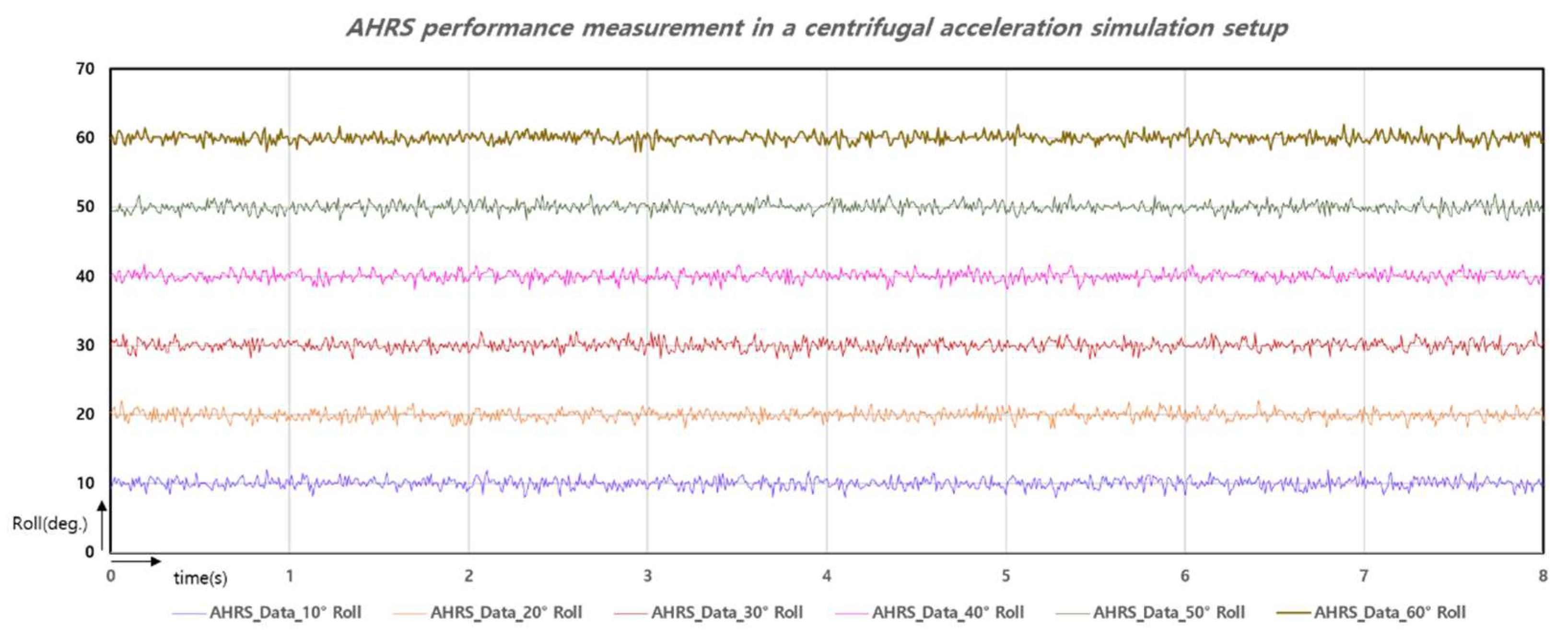

3.3.3. Test Results and Verification

3.4. Summary of Avionics Validation

4. Results

4.1. Flight Test Overview

4.2. Flight Test Environment

4.3. Test Results

4.3.1. Altitude Control Performance

4.3.2. Path-Following Performance

4.3.3. Control Parameters

4.3.4. Comparative Evaluation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haque Nawaz Lashari, H.; Husnain Mansoor Ali, H.M.; Shafiq-Ur-Rehman Massan, S. Applications of unmanned aerial vehicles: A review. J. Ad. Res. Aerosp. 2019, 3, 85–105. [Google Scholar]

- Hassler, S.C.; Baysal-Gurel, F. Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS) Technology and Applications in Agriculture. Agriculture 2019, 9, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed Mohd Daud, S.M. Applications of drone in disaster management: A scoping review. Sci. Justice 2022, 62, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, K.; Lamensch, M. AI, drones future of defense. In MIGS Institute Report; MIGS Institute: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Shahrul Hairi, S.M.F.; Mohd Saleh, S.J.M.; Hamdan, A. A Review on Composite Aerostructure Development for UAV Application. In Green Hybrid Composite in Engineering and Non-Engineering Applications; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 137–157. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. A Low-cost High-Precision Geo-Location Solution for UAVs. In Proceedings of the 15th South East Asian Survey Congress, Darwin, Australia, 15–18 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Šostakaitė, L.; Šapranauskas, E.; Rudinskas, D.; Rimkus, A.; Gribniak, V. Investigating Additive Manufacturing Possibilities for an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle with Polymeric Materials. Polymers 2024, 16, 2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, G.D.; Agarwala, S.; Goh, G.L.; Dikshit, V.; Sing, S.L.; Yeong, W.Y. Additive manufacturing in unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs): Challenges and potential. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2017, 63, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G. Evaluating the Use of a Low-Cost Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Platform in Acquiring Digital Imagery for Emergency Response. In Geomatics Solutions for Disaster Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 117–133. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.-H.; Shin, H.-S.; Tsourdos, A. A design of a short course with COTS UAV system for higher education students. IFAC PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedberg, S.J. Australia’s SYPAQ Delivers Cardboard Drones to Ukraine for Logistics and ISR. Breaking Defense. Available online: https://breakingdefense.com/2023/03/australias-sypaq-delivers-cardboard-drones-to-ukraine-for-logistics-and-isr/ (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- BBC News. Russia’s Intensifying Drone War is Spreading Fear and Eroding Ukrainian Morale. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c0m8gn7grn2o (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Mohsan, S.A.H.; Khan, M.A.; Noor, F.; Ullah, I.; Alsharif, M.H. Towards the Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): A Comprehensive Review. Drones 2022, 6, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudarzi, S. Threat in the Sky: How Cheap Drones Are Changing Warfare. The Bulletin. Available online: https://thebulletin.org/2023/11/threat-in-the-sky-how-cheap-drones-are-changing-warfare/ (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Senewirathna, A.N.; Siriwardana, D. Eyes in the Sky: The Strategic Role of Drones in Modern Warfare and Surveillance. J. Mil. Tech. 2024, 4, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, F.H.; Lanoszka, A. Unconventional airpower: How non-state actors used aerial drone capabilities. Def. Stud. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J. Artificial Intelligence, Drone Swarming and Escalation Risks in Future Warfare. RUSI J. 2020, 165, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giernacki, W.; Skwierczyński, M.; Witwicki, W.; Wroński, P.; Kozierski, P. Crazyflie 2.0 quadrotor as a platform for research and education in robotics and control engineering. In Proceedings of the 2017 22nd International Conference on Methods and Models in Automation and Robotics (MMAR), Miedzyzdroje, Poland, 29 August–1 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, J.; Cox, C.; Bingham, B.; Quigley, M. Design and development of a low-cost, hand-launched UAV for educational and research purposes. In Proceedings of the AIAA Scitech 2021 Forum, Virtual Event, 11–15 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, U.N.; Faruque, I. Multi-IMU Based Alternate Navigation Frameworks: Performance & Comparison for UAS. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 17565–17577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, R. A Low-cost Vision Based Navigation System for Small Size Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Applications. J. Aeronaut. Aerosp. Eng. 2013, 2, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, K.H.; Chong, G.; Li, Y. PID control system analysis, design, and technology. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2005, 13, 559–576. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, G.; Huang, H.; Waslander, S.; Tomlin, C. Quadrotor Helicopter Flight Dynamics and Control: Theory and Experiment. In AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference; AIAA: Hilton Head, SC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Dixon, W.E. Gradient-Free Cooperative Source-Seeking for Multi-Agent Systems under Disturbances and Communication Constraints. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 62, 5763–5772. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Deyst, J.; How, J.P. A New Nonlinear Guidance Logic for Trajectory Tracking. In AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference; AIAA: Providence, RI, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, L.; Tanskanen, P.; Heng, L.; Lee, G.H.; Fraundorfer, F.; Pollefeys, M. PIXHAWK: A System for Autonomous Flight Using Onboard Computer Vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Shanghai, China, 9–13 May 2011; pp. 2992–2997. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, R.; McLain, T. Small Unmanned Aircraft: Theory and Practice; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| Quantity | Value | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Wing area | 0.400 m2 | From stall sizing |

| Root chord | 0.298 m | |

| Tip chord | 0.149 m | |

| MAC | 0.232 m | |

| MAC span station | 0.398 m | |

| MAC LE | 0.230 m | |

| ) | 0.244 | Adequate margin |

| Wing loading | 73.5 N/m2 | At MTOW |

| Vertical tail volume | 0.03 (Target) | Typical 0.02–0.04 |

| Lever arm | 0.30 m (Initial) | To be confirmed |

| Total fin area | 0.0717 m2 | L + R; single ≈ 0.036 m2 |

| Item | Quantity | Unit Price (USD) | Cost (USD) | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardboard | 3 sheet | 2.5 | 7.5 | Commercially available |

| Adhesive (glue) | - | 2.0 | 2.0 | Partial usage cost |

| Laser cutting | - | 8.0 | 8.0 | One-time cutting service |

| Total (airframe) | - | - | 17.5 | Under USD 20 |

| Load (kg) | W (N) | Short Spar L = 0.53 | Full Span L = 1.79 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 0.922 | 9.045 | 1.143 | 8.061 |

| 1.840 | 18.050 | 2.281 | 16.087 |

| 2.724 | 26.722 | 3.377 | 23.815 |

| 3.600 | 35.316 | 4.462 | 31.475 |

| 4.472 | 43.870 | 5.543 | 39.098 |

| 5.376 | 52.739 | 6.664 | 47.003 |

| 6.304 | 61.842 | 7.814 | 55.116 |

| 7.232 | 70.946 | 8.965 | 63.229 |

| Category | Specification | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| MCU | PJRC Teensy 4.1 | 32-bit, 1 MB RAM, 8 MB Flash |

| Sensor (AHRS) | Bosch BNO055 9-axis IMU | Embedded quaternion computation |

| GNSS | u-blox GPS | Position, velocity, time data |

| RC Input | 6 channels (PWM/SBUS compatible) | For receiver input |

| RC Output | 6 channels PWM | For servo/ESC control |

| Interfaces | UART × 4, I2C × 1, USB × 1 | For GCS and sensors |

| Bank Angle (Deg) | 10 | 20 | 30 | 45 | 60 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Required Speed (RPM) | 16.2 | 23.3 | 29.3 | 38.6 | 50.8 |

| Control Component | Parameter | Value | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Altitude PI Controller | 0.80 | Tuned to achieve fast climb response without overshoot. | |

| 0.12 | Eliminates steady-state altitude error. | ||

| Roll PI Controller | 1.10 | Provides sufficient roll authority for turning. | |

| 0.08 | Stabilizes roll angle in gusty conditions. | ||

| Heading (Yaw) PI Controller | 0.60 | Stabilizes course angle under GPS noise. | |

| 0.05 | Prevents long-term drift. | ||

| LOS Guidance Look-ahead distance | 12 m | Ensures smooth path-following without aggressive turns. |

| Metric | This Study | SYPAQ PPDS (2023) |

|---|---|---|

| Structural material cost | USD 17.5 | ~USD 700 |

| Structural weight | ||

| Verified load capability | (payload class) | |

| Altitude control accuracy | Not reported | |

| Path-following error | Not reported | |

| Remarks | Fully autonomous flight | Designed primarily for logistics |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, Y.-D.; Kim, T.-W.; Kim, H.-K. Design and Autonomous Flight Demonstration of a Low-Cost Cardboard-Based UAV. Drones 2025, 9, 848. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120848

Park Y-D, Kim T-W, Kim H-K. Design and Autonomous Flight Demonstration of a Low-Cost Cardboard-Based UAV. Drones. 2025; 9(12):848. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120848

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Yong-Deok, Tae-Wook Kim, and Hun-Kee Kim. 2025. "Design and Autonomous Flight Demonstration of a Low-Cost Cardboard-Based UAV" Drones 9, no. 12: 848. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120848

APA StylePark, Y.-D., Kim, T.-W., & Kim, H.-K. (2025). Design and Autonomous Flight Demonstration of a Low-Cost Cardboard-Based UAV. Drones, 9(12), 848. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120848