Ground Risk Buffer Estimation for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Test Flights Based on Dynamics Analysis

Highlights

- The force characteristics of rotor UAVs and fixed-wing UAVs are analyzed and the falling trajectories are calculated based on the dynamics model analysis.

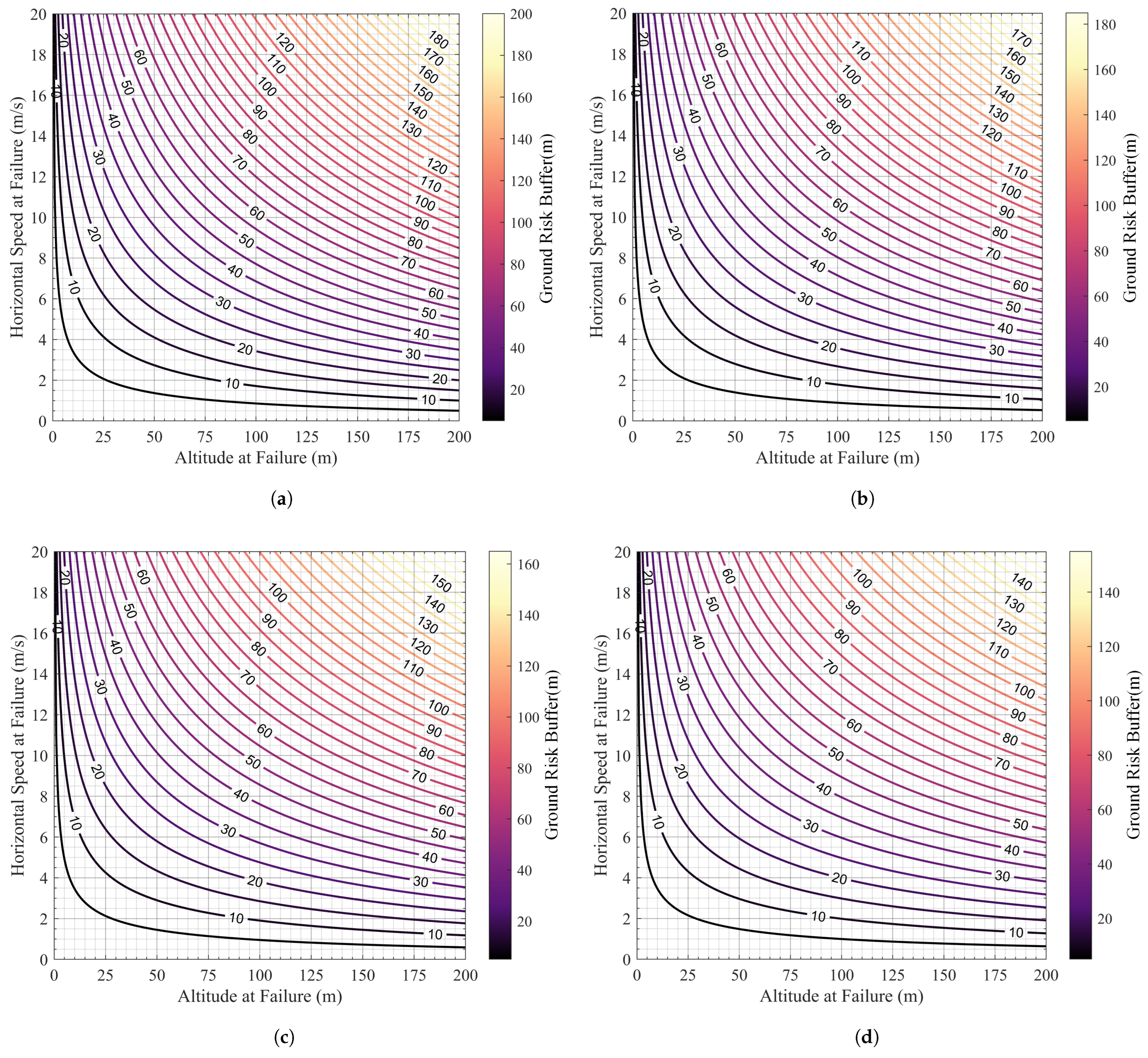

- Both airspace uncertainty and operational risk are considered in test flight and a 3D contour map is generated for quantitative estimation of the ground risk buffer

- The greater safety margin provided by the proposed method is verified using actual test flight certification cases.

Abstract

1. Introduction

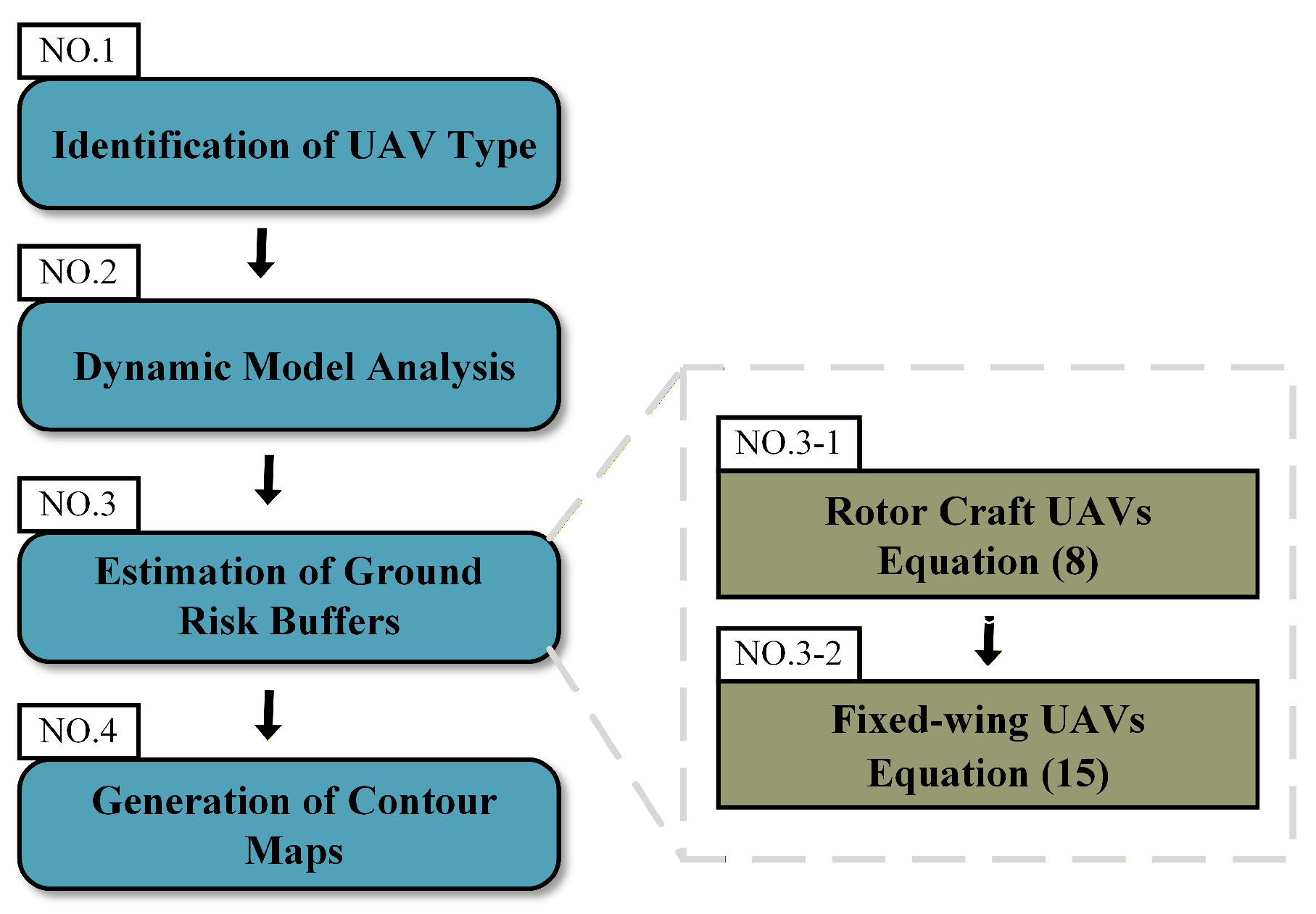

2. Method

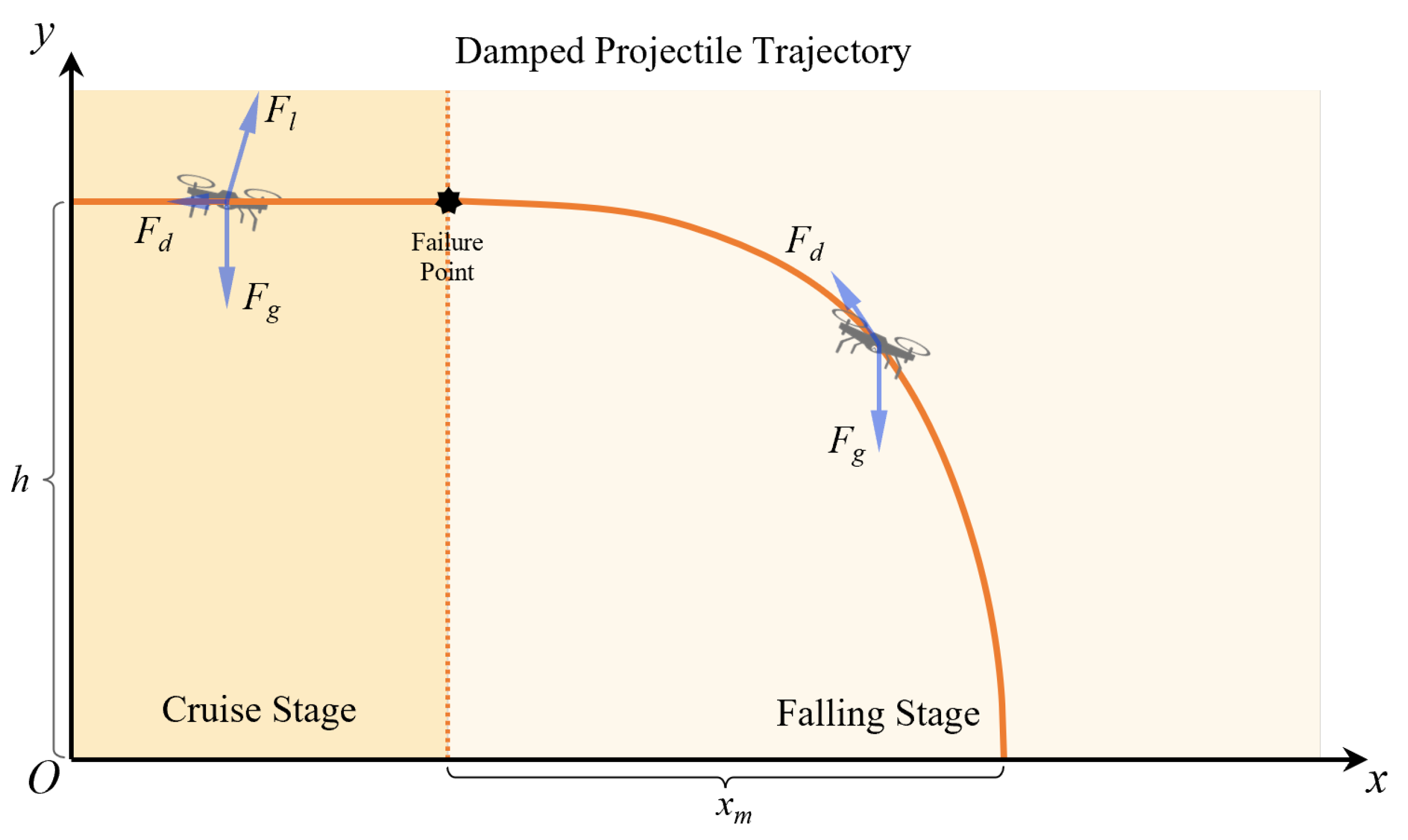

2.1. Rotorcraft UAV

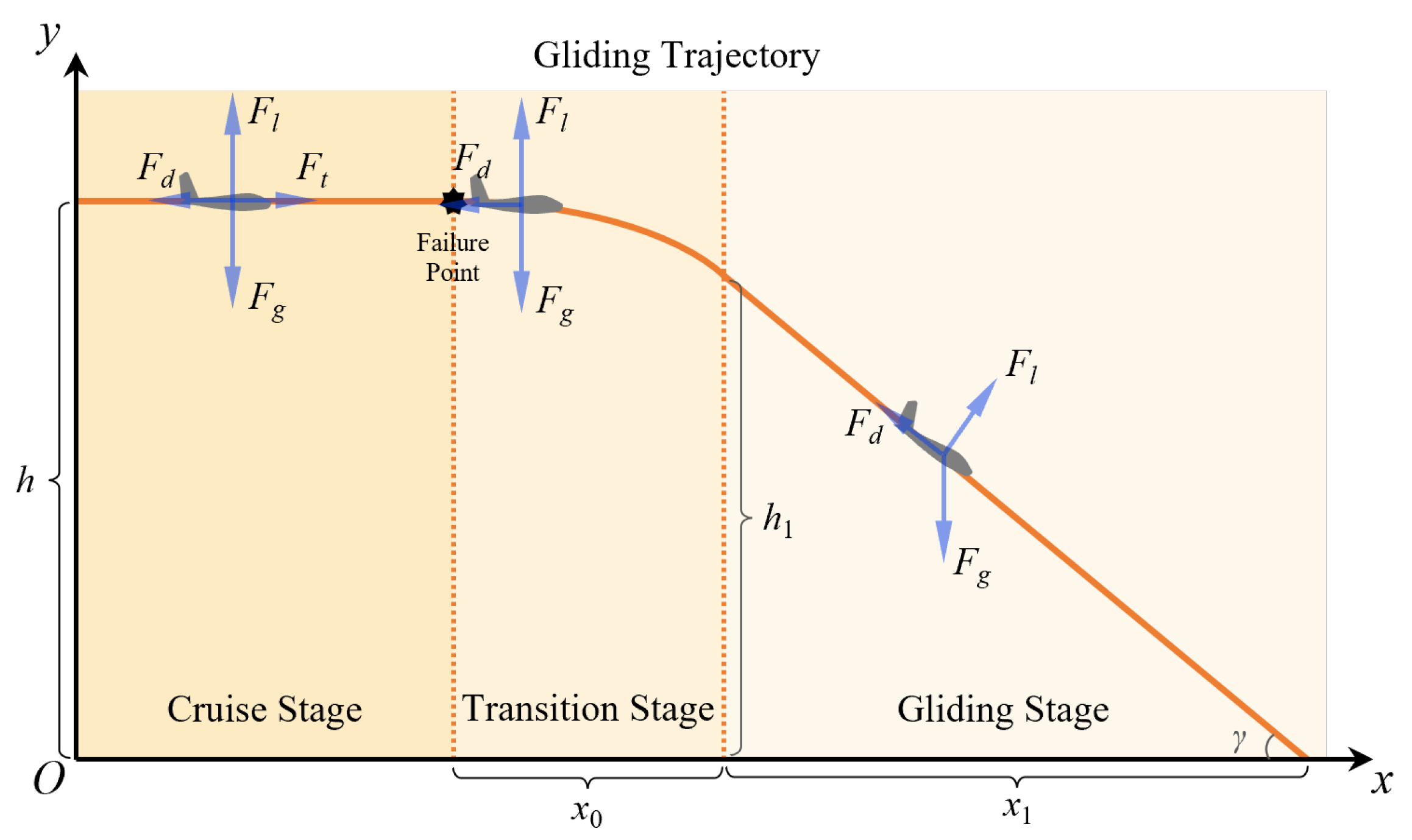

2.2. Fixed-Wing UAV

3. Results

3.1. Rotorcraft UAV Analysis

3.1.1. Simulation Results of Rotorcraft UAV

3.1.2. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

3.1.3. Comparison with Other Methods

3.1.4. Case Analysis of Rotorcraft UAV

3.2. Fixed-Wing UAV Analysis

3.2.1. Simulation Results of Fixed-Wing UAV

3.2.2. Comparison to Other Methods

3.2.3. Case Analysis of Fixed-Wing UAV

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

DURC Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| SORA | Specific Operations Risk Assessment |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| JARUS | Joint Authorities for Rulemaking on Unmanned Systems |

| CAAC | Civil Aviation Administration of China |

| CCAR | China Civil Aviation Regulations |

| TC | Type Certificate |

References

- Tsouros, D.C.; Bibi, S.; Sarigiannidis, P.G. A review on UAV-based applications for precision agriculture. Information 2019, 10, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, D.; Cao, Y.; Zhao, K.; Zhu, L. Optimization strategies of fruit detection to overcome the challenge of unstructured background in field orchard environment: A review. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 1183–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Liang, L.; Ji, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, K.; Shi, F.; Créput, J.C. Exploring the YOLO-FT deep learning algorithm for UAV-Based smart agriculture detection in communication networks. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2024, 21, 5347–5360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torresan, C.; Berton, A.; Carotenuto, F.; Di Gennaro, S.F.; Gioli, B.; Matese, A.; Miglietta, F.; Vagnoli, C.; Zaldei, A.; Wallace, L. Forestry applications of UAVs in Europe: A review. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 38, 2427–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatopoulos, I.; Le, T.; Daver, F. UAV-assisted seeding and monitoring of reforestation sites: A review. Aust. For. 2024, 87, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, D.; Wang, Z.; Sun, H.; Liu, L.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J. Salience feature guided decoupling network for UAV forests flame detection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 270, 126414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadzadeh, S.; de Oliveira, W.J.; de Souza Filho, C.R. UAV-based remote sensing for the petroleum industry and environmental monitoring: State-of-the-art and perspectives. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 208, 109633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Li, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, S.; Yu, D.; Ma, Y. Power line-guided automatic electric transmission line inspection system. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 3512118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Liu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Fang, Y.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Liu, Z. UAV based sensing and imaging technologies for power system detection, monitoring and inspection: A review. Nondestruct. Test. Eval. 2024, 40, 5681–5748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Lu, W.; Sheng, M.; Chen, Y.; Tang, J.; Yu, F.R.; Wong, K.K. UAV-assisted emergency networks in disasters. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2019, 26, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Zou, S.; Peng, H.; Ni, W.; Sun, Y.; Gao, H. Cooperative UAV trajectory design for disaster area emergency communications: A multiagent PPO method. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 11, 8848–8859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuru, K.; Ansell, D.; Khan, W.; Yetgin, H. Analysis and optimization of unmanned aerial vehicle swarms in logistics: An intelligent delivery platform. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 15804–15831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandirola, M.; Casarotti, C.; Peloso, S.; Lanese, I.; Brunesi, E.; Senaldi, I. Use of UAS for damage inspection and assessment of bridge infrastructures. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 72, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Interim Regulation on Civil Unmanned Aircraft Flight Management. 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/202306/content_6888799.htm (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. Regulations on Civil Unmanned Aircraft Operations Safety Management. 2024. Available online: https://xxgk.mot.gov.cn/2020/gz/202401/t20240103_3980656.html (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Aircraft Airworthiness Certification Department of CAAC. AMOS-Certificate Search, 2025. Available online: https://amos.caac.gov.cn/#/certificate (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Dittrich, J. JARUS Guidelines on Specific Operations Risk Assessment (SORA); Technical Report; Joint Authorities for Rulemaking on Unmanned Systems: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shelley, A.V. Ground Risk for Large Multirotor UAVs. 2021. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/53282063/Ground_Risk_Buffer_for_Large_Multirotor_UAVs (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Shelley, A.V. Ground Risk Buffer for Large Helicopter UAVs. 2022. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/71738438/Ground_Risk_Buffer_for_Large_Helicopter_UAVs (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Kim, Y.S.; Bae, J.W. Small UAV failure rate analysis based on human damage on the ground considering flight over populated area. J. Korean Soc. Aeronaut. Space Sci. 2021, 49, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Blom, H.; Rattanagraikanakorn, B. Enhancing safety feedback to the design of small, unmanned aircraft by joint assessment of impact area and human fatality. Risk Anal. 2025, 45, 1115–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Zheng, B.; Mo, M.; Shang, J.; Huang, D. Aircraft-cargo separation rate-driven ground risk–cost optimization for urban logistics UAVs. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 154568–154580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Yang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Guan, X.; Wang, S. Quantitative ground risk assessment for urban logistical unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) based on bayesian network. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Sun, L.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, L.; Ren, G.; Zhou, G.; Chen, X.; et al. Ground risk assessment for unmanned aircraft systems based on dynamic model. Drones 2022, 6, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigante, G.; Bernard, M.; Palumbo, R.; Travascio, L.; Vozella, A. Current approaches in UAV operational risk assessment and practical considerations. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2716, 012055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- la Cour-Harbo, A. Ground impact probability distribution for small unmanned aircraft in ballistic descent. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Athens, Greece, 1–4 September 2020; pp. 1442–1451. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.E.; Shao, P.C. Failure analysis for an unmanned aerial vehicle using safe path planning. J. Aerosp. Inf. Syst. 2020, 17, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Wu, C.; Qiao, L.; Zhang, H. Determination of ground risk buffer for unmanned aerial vehicles based on Monte Carlo simulation. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2025, 25, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Che Man, M.H.; Kumar Sivakumar, A.; Hu, H.; Huat Low, K. Ground crash area estimation of quadrotor aircraft under propulsion failure. J. Air Transp. 2023, 31, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavcar, M. The International Standard Atmosphere (ISA); Anadolu University: Eskisehir, Turkey, 2000; Volume 30, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Shenzhen Dajiang Innovation Technology Co., Ltd. Technologic Parameter of DJI Air 3S. 2024. Available online: https://www.dji.com/cn/air-3s/specs (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Phoenix Wings Co., Ltd. Technologic Parameter of ARK40. 2024. Available online: https://piw-mr-web.inn.sf-express.com/uav/ark-40 (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- XAG Co., Ltd. Technologic Parameter of XAG P30. 2024. Available online: https://www.xa.com/en/p30 (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Shenzhen Dajiang Innovation Technology Co., Ltd. Technologic Parameter of DJI T30. 2024. Available online: https://ag.dji.com/cn/t30/specs (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Arterburn, D.; Ewing, M.; Prabhu, R.; Zhu, F.; Francis, D. FAA UAS Center of Excellence Task A4: UAS Ground Collision Severity Evaluation; Technical Report; United States Federal Aviation Administration, Unmanned Aircraft Systems, Center of Excellence: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Houwen, P. The development of Runge-Kutta methods for partial differential equations. Appl. Numer. Math. 1996, 20, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnick-Cohen, E.; Herrmann, J.W.; Azarm, S. Modeling unmanned aerial system (UAS) risks via Monte Carlo simulation. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Atlanta, GA, USA, 11–14 June 2019; pp. 1296–1305. [Google Scholar]

- Raymer, D. Aircraft Design: A Conceptual Approach; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Name of UAV | Mass (kg) | Area (m2) | Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| DJI Air 3S [31] | 0.724 | 0.0215 | 0.016943 |

| ARK40 [32] | 46 | 1.1272 | 0.013981 |

| XAG P30 [33] | 38.5 | 0.6453 | 0.009563 |

| DJI T30 [34] | 78 | 0.9193 | 0.006725 |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum take-off weight | 113 kg | Frontal area | 1.0516 m2 |

| Minimum take-off weight | 53 kg | Ambient temperature | 15 °C |

| Flight altitude | 40 m | Barometric pressure | 101 kPa |

| Maximum speed | 13.8 m/s | Drag coefficient | 0.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mei, Y.; Chang, H.; Li, L.; Ji, Q.; Zhong, H. Ground Risk Buffer Estimation for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Test Flights Based on Dynamics Analysis. Drones 2025, 9, 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120849

Mei Y, Chang H, Li L, Ji Q, Zhong H. Ground Risk Buffer Estimation for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Test Flights Based on Dynamics Analysis. Drones. 2025; 9(12):849. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120849

Chicago/Turabian StyleMei, Yanan, He Chang, Li Li, Qian Ji, and Hangyu Zhong. 2025. "Ground Risk Buffer Estimation for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Test Flights Based on Dynamics Analysis" Drones 9, no. 12: 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120849

APA StyleMei, Y., Chang, H., Li, L., Ji, Q., & Zhong, H. (2025). Ground Risk Buffer Estimation for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Test Flights Based on Dynamics Analysis. Drones, 9(12), 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120849