A Lightweight Multi-Module Collaborative Optimization Framework for Detecting Small Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Anti-Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Systems

Highlights

- Proposition of YOLO-CoOp, a lightweight multi-module collaborative framework with HRFPN, C3k2-WT, SCSA, and DyATF modules specifically optimized for small UAV detection.

- Achievement of 94.3% precision and 96.2% mAP50 on UAV-SOD dataset with only 1.97 M parameters (24% fewer than baseline), demonstrating superior detection performance with reduced computational requirements.

- Contribution to vision-based detection capabilities in an anti-UAV system by offering a lightweight yet effective framework for small UAV detection.

- Cross-dataset validation experiments demonstrate that the proposed method consistently improves small object detection performance, offering a transferable solution with potential applicability to other domains involving small target detection.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A UAV-SOD dataset is established specifically for solving small UAV detection.

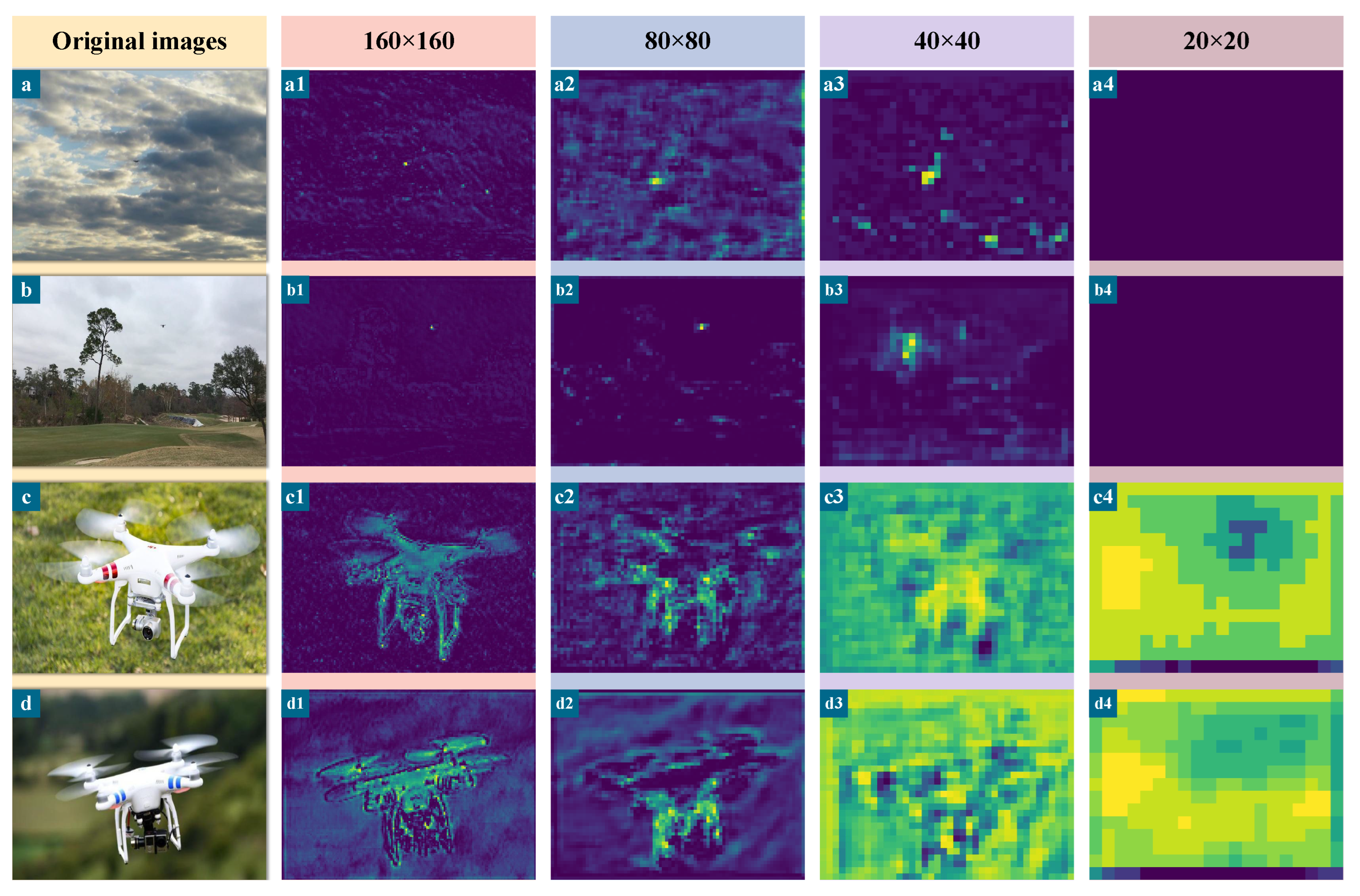

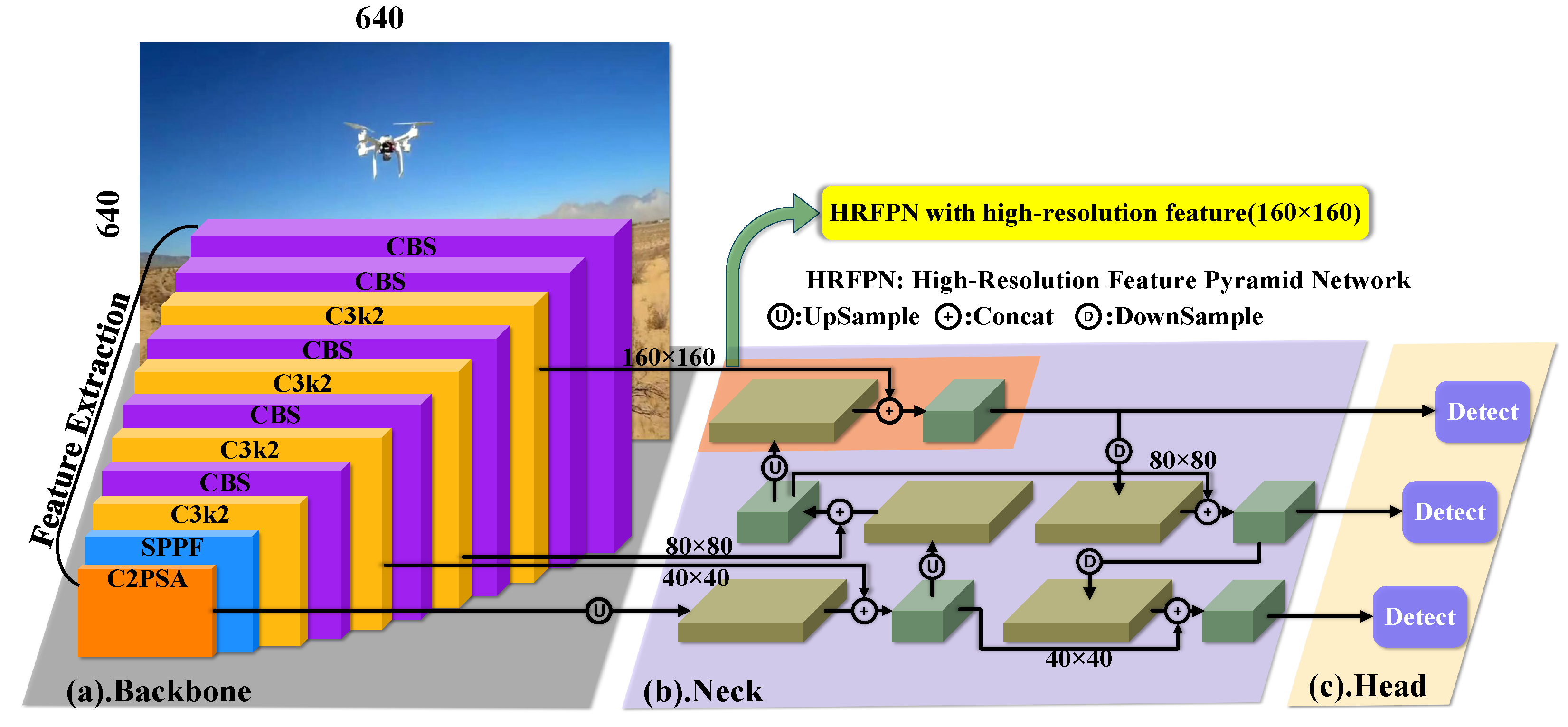

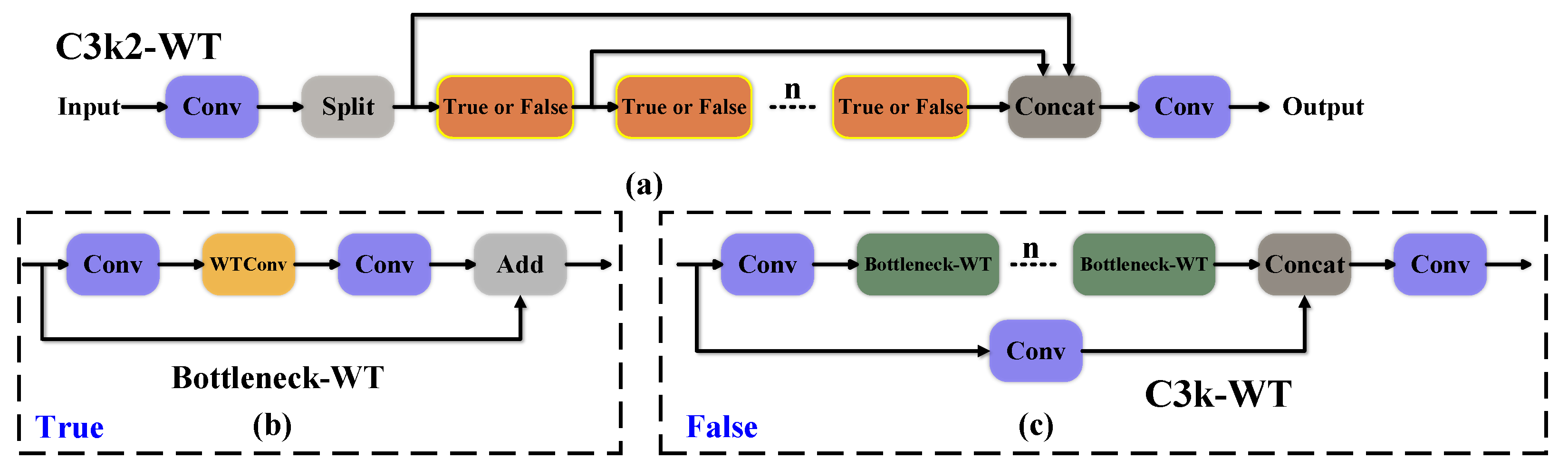

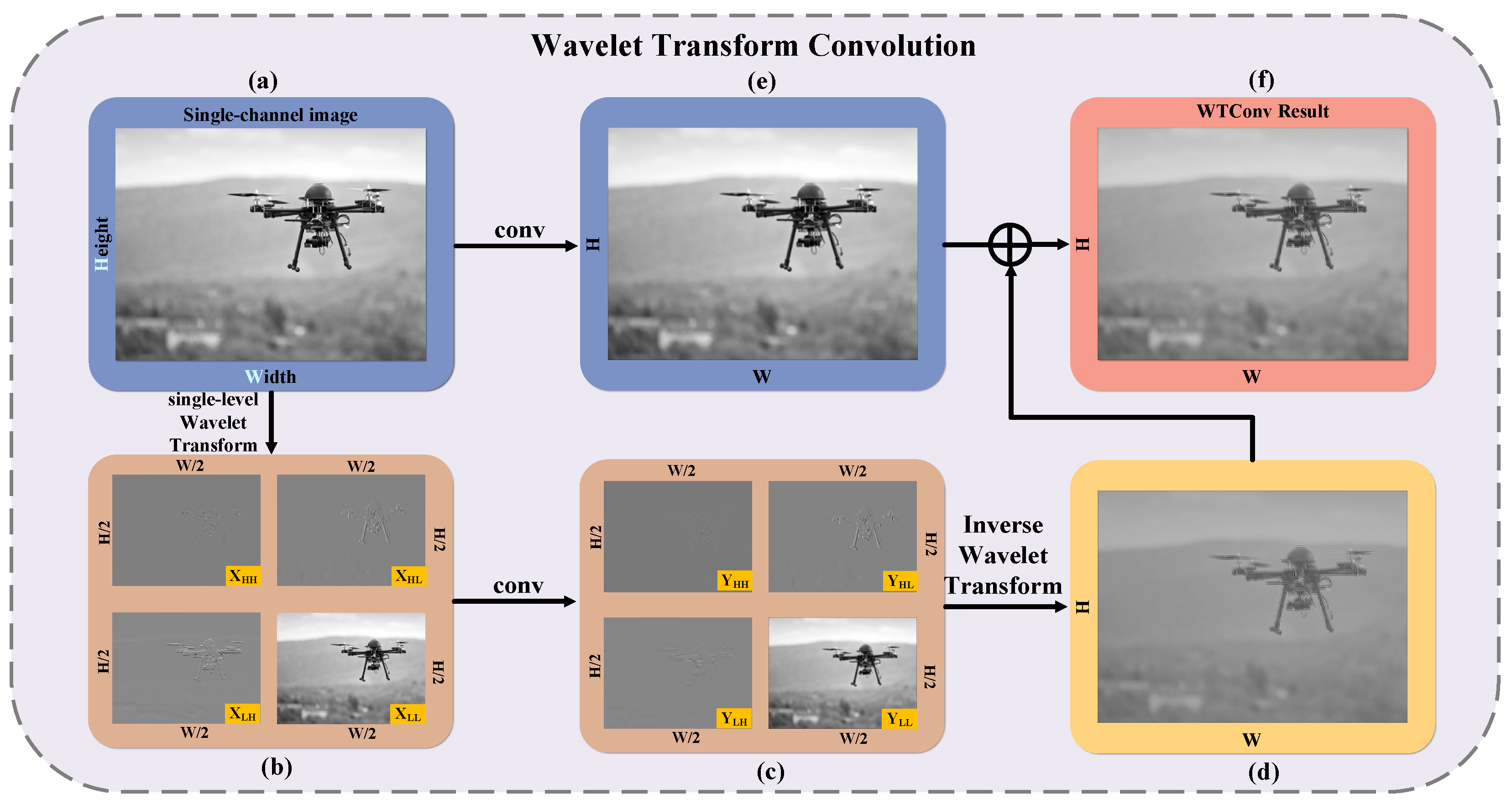

- In the feature extraction stage, feature extraction is enhanced through a C3k2-WT module that integrates wavelet transform convolution (WTConv). It can extract features of different frequencies through small kernel filters. Furthermore, it increases the receptive field of the model without excessively increasing parameters.

- In the feature fusion stage, high-detail and high-resolution feature maps are obtained through the high-resolution feature pyramid network (HRFPN) and Dysample upsampling. They have more detailed information about small UAVs, which help improve UAV detection performance after information fusion.

- In the detection stage, the spatial-channel synergistic attention (SCSA) mechanism integrates spatial and channel information from high-resolution feature maps, allowing the framework to focus more on effective information, and adaptive threshold focal loss (ATFL) assigns higher weights to small UAVs.

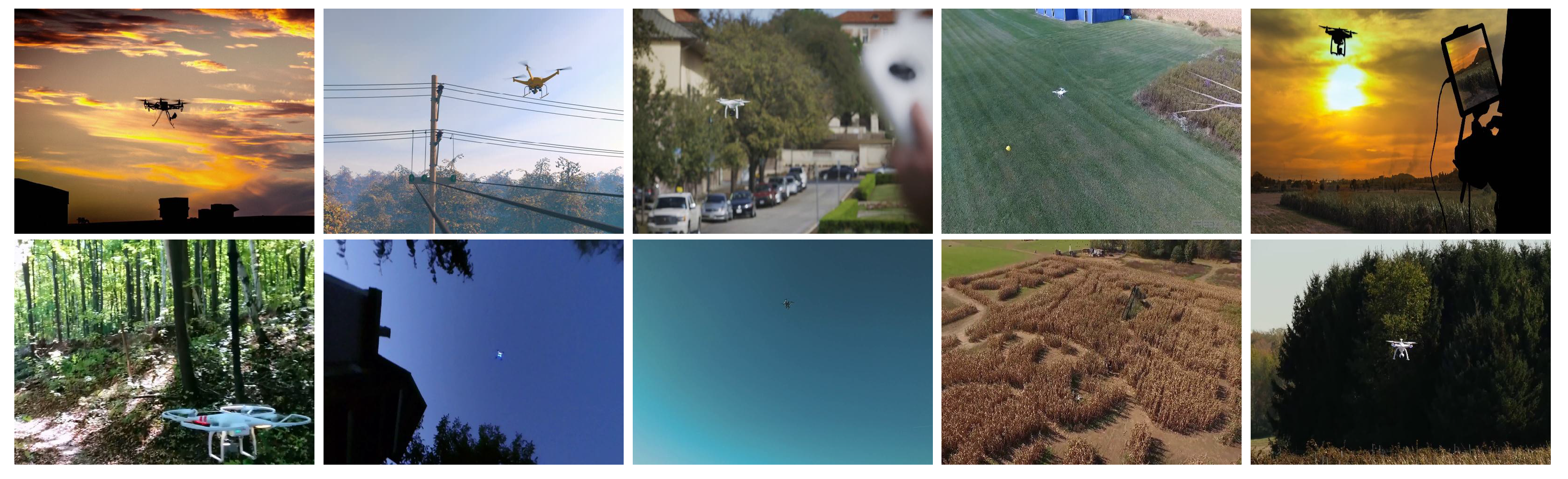

2. Materials

2.1. General UAV Datasets

| Datasets | Target Type | Task | Release Year | Data Quantity | Quantity | Label Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UAV123 [37] | UAV-Aerial | D,T | 2015 | 112,578 | 28 | 112,578 |

| FL-Drones [46] | UAV-target | D,T | 2016 | 8000 | 1 | 8000 |

| DOTA [47] | Aerial images | D | 2018 | 11,268 | 18 | 188,282 |

| Visdrone [38] | UAV-Aerial | D,T | 2019 | 10 | over | |

| UAVDT [39] | UAV-Aerial | D,T | 2018 | 80,000 | 3 | 841,500 |

| AU-AIR [40] | UAV-Aerial | D | 2020 | 32,800 | 8 | over |

| DroneCrowd [41] | UAV-Aerial | D,T | 2021 | 33,600 | 1 | over |

| MOT-Fly [43] | UAV-target | C,D | 2021 | 11,186 | 3 | 23,544 |

| AnimalDrone [42] | UAV-Aerial | D | 2021 | 53,600 | 1 | over |

| Anti-UAV [10] | UAV-target | D,T | 2021 | 580,000 | 1 | 580,000 |

| DUT Anti-UAV [11] | UAV-target | D | 2022 | 10,000 | 1 | over |

| HIT-UAV [48] | UAV-Aerial | D | 2023 | 2898 | 5 | 24,899 |

| DroneSwarms [44] | UAV-target | D | 2024 | 9100 | 1 | 242,200 |

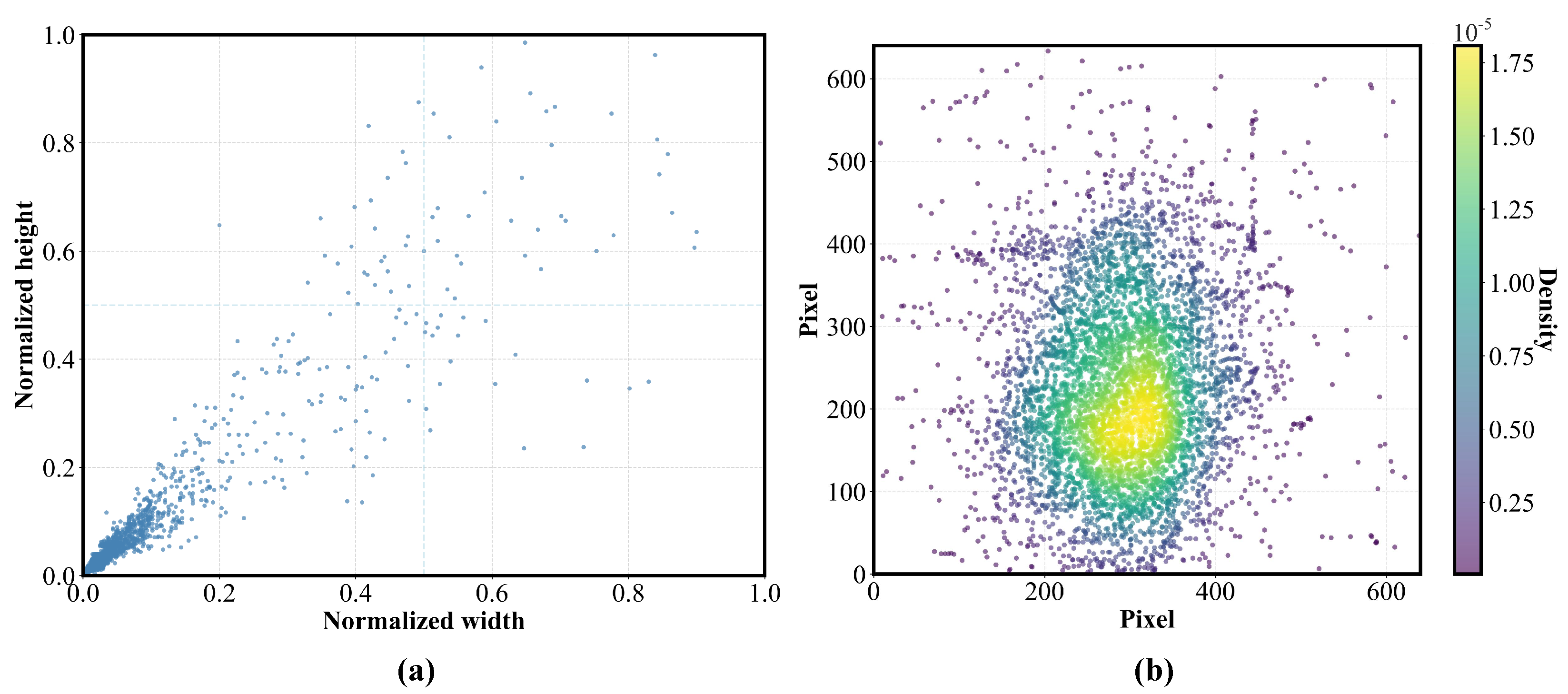

2.2. Analysis of UAV-SOD

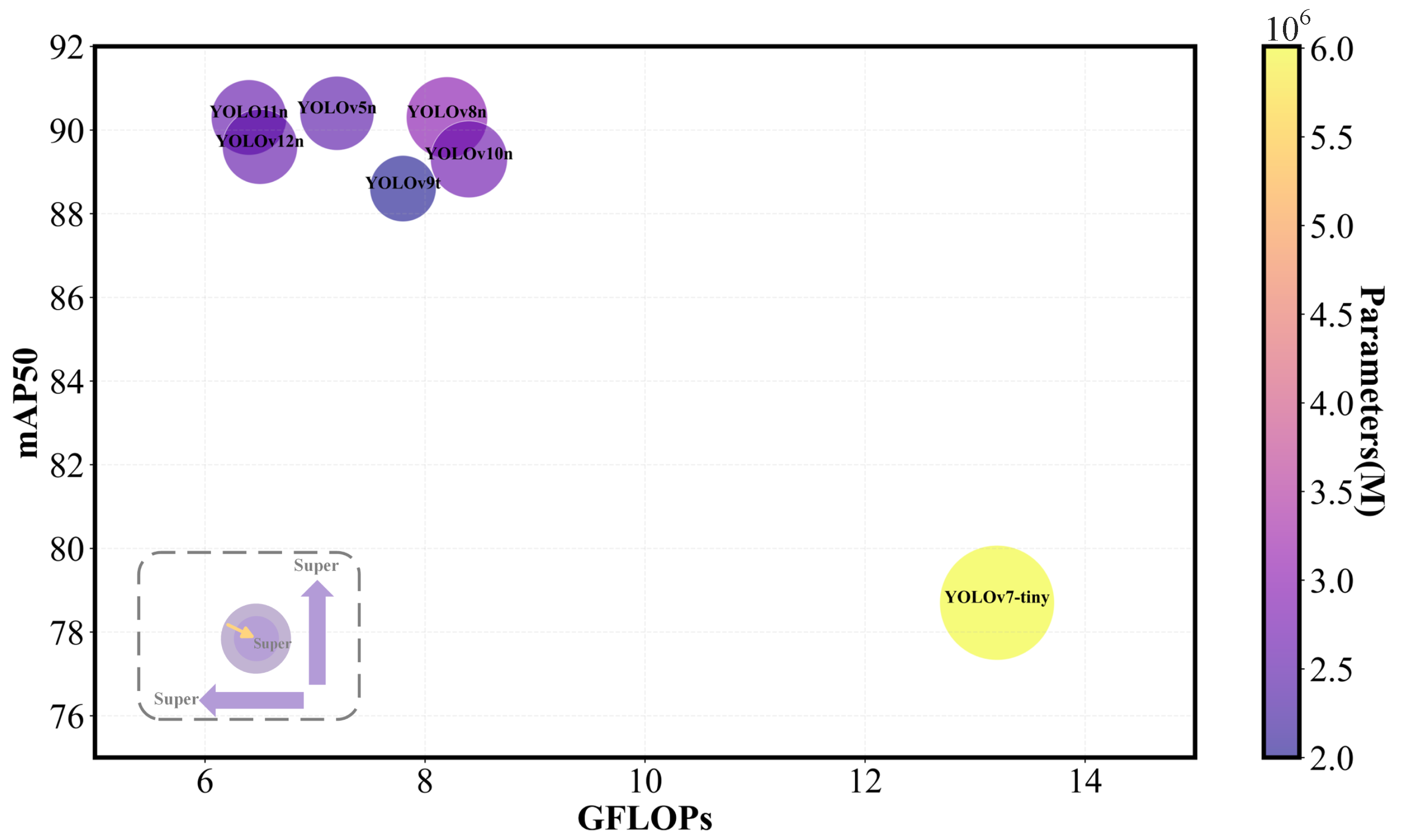

2.3. Basic Framework Selection

3. Methods

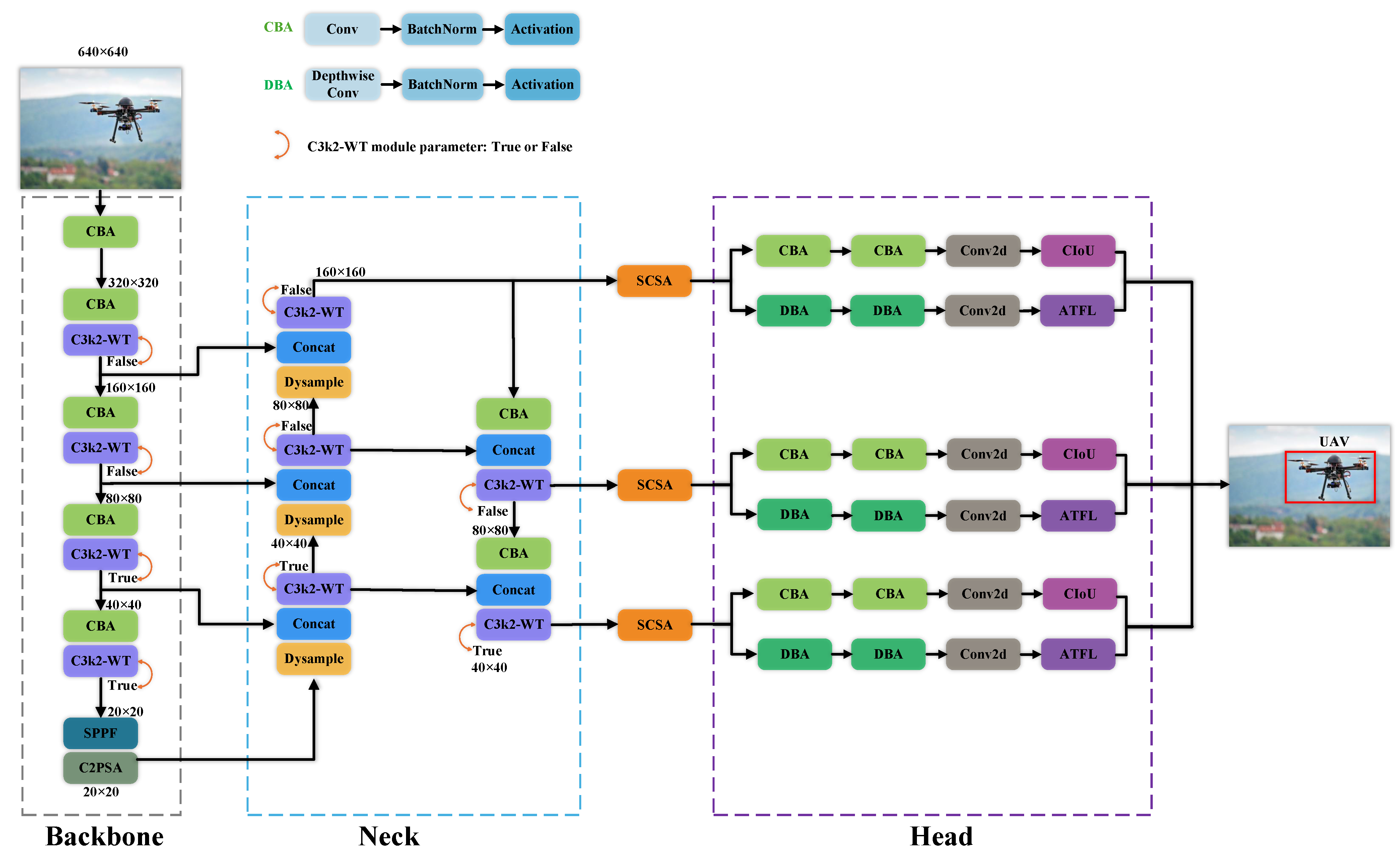

3.1. YOLO-CoOp

3.2. Structure and Principle of HRFPN

3.3. C3k2-WT Module

Receptive Field and Parameter Analysis

- Each level requires sequential DWT → Conv → IWT, increasing latency due to multiple memory reads/writes;

- In modern CNN backbones (e.g., ResNet, ConvNeXt), feature maps in deep stages have low spatial resolution (e.g., ), making infeasible;

- For small UAV detection, where targets often span only a few pixels, a moderate ERF (e.g., to ) is sufficient to capture local context without over-smoothing fine details.

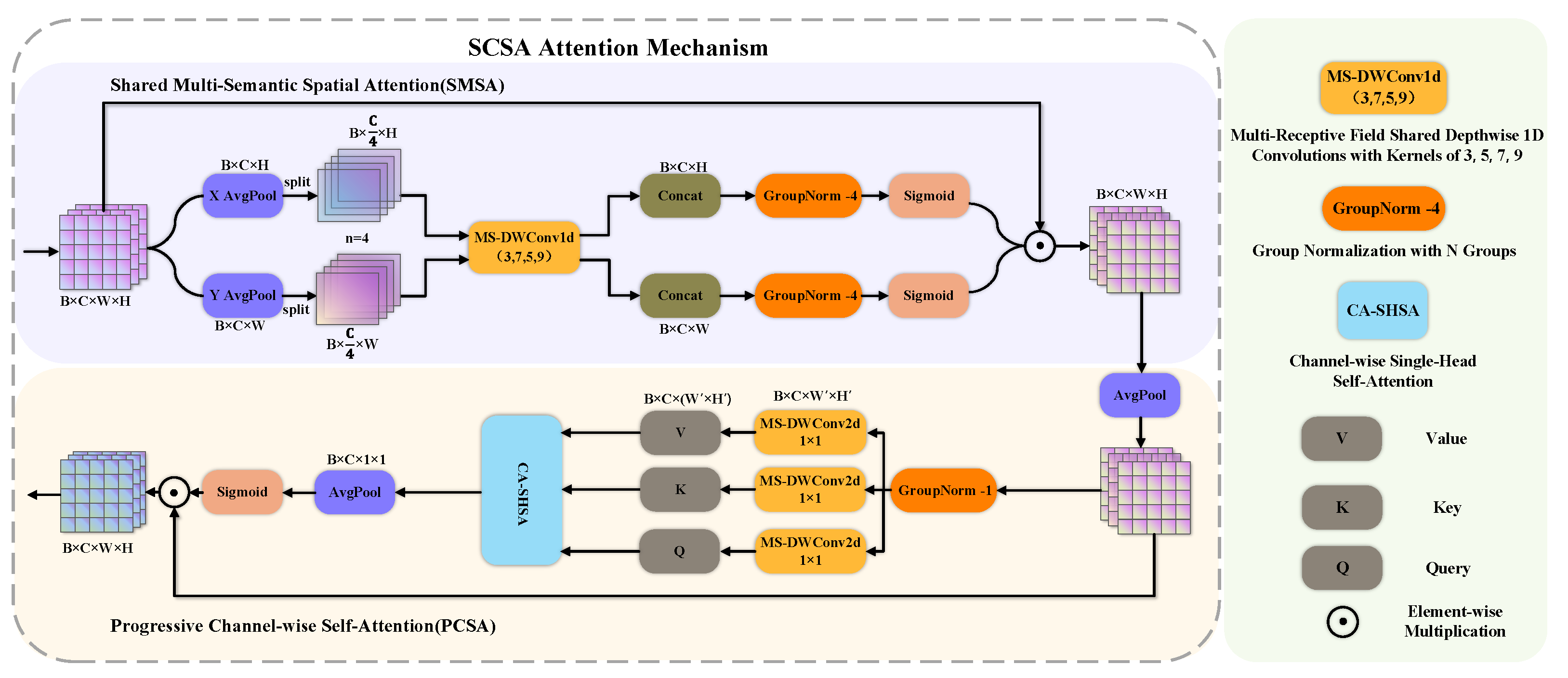

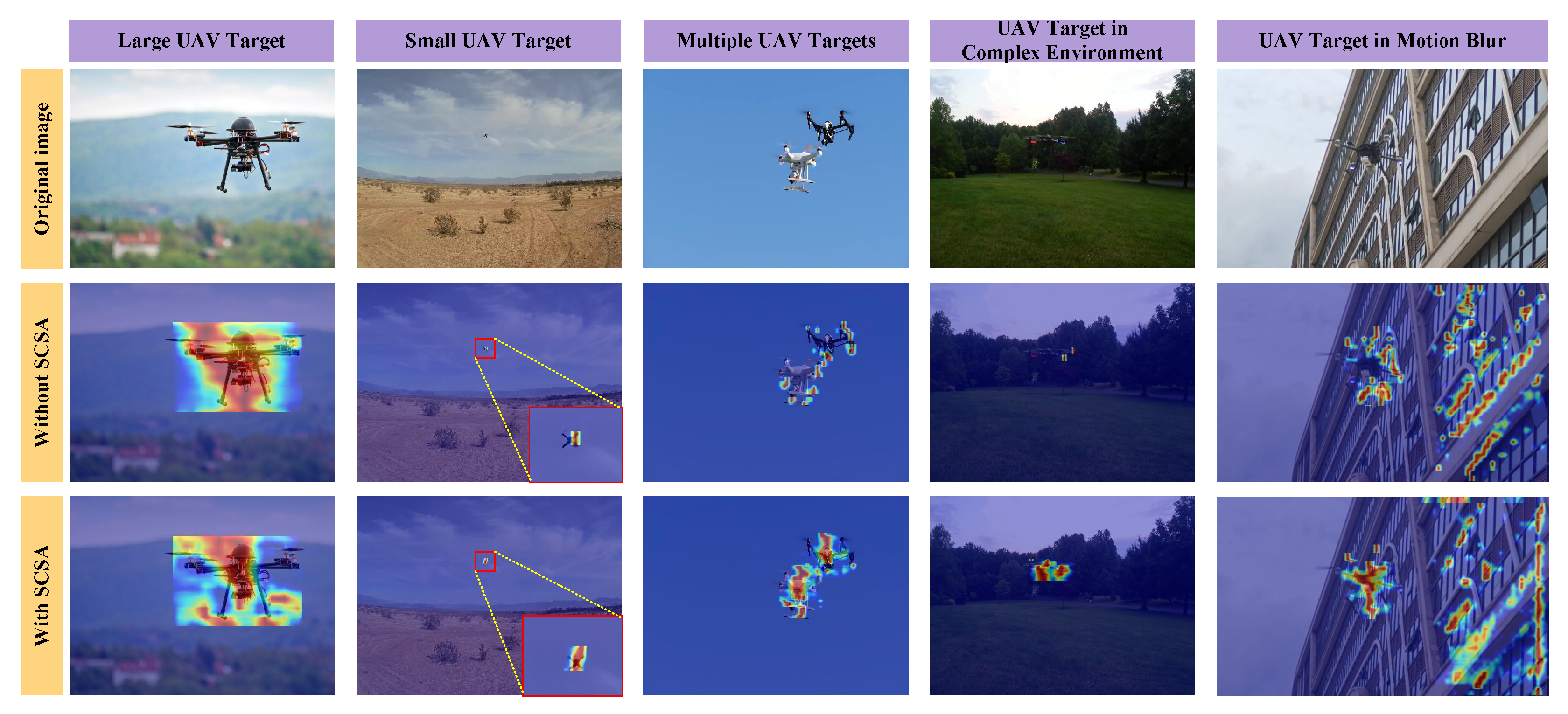

3.4. SCSA Module

3.5. DyATF Collaborative Optimization

3.5.1. Loss Function Optimization

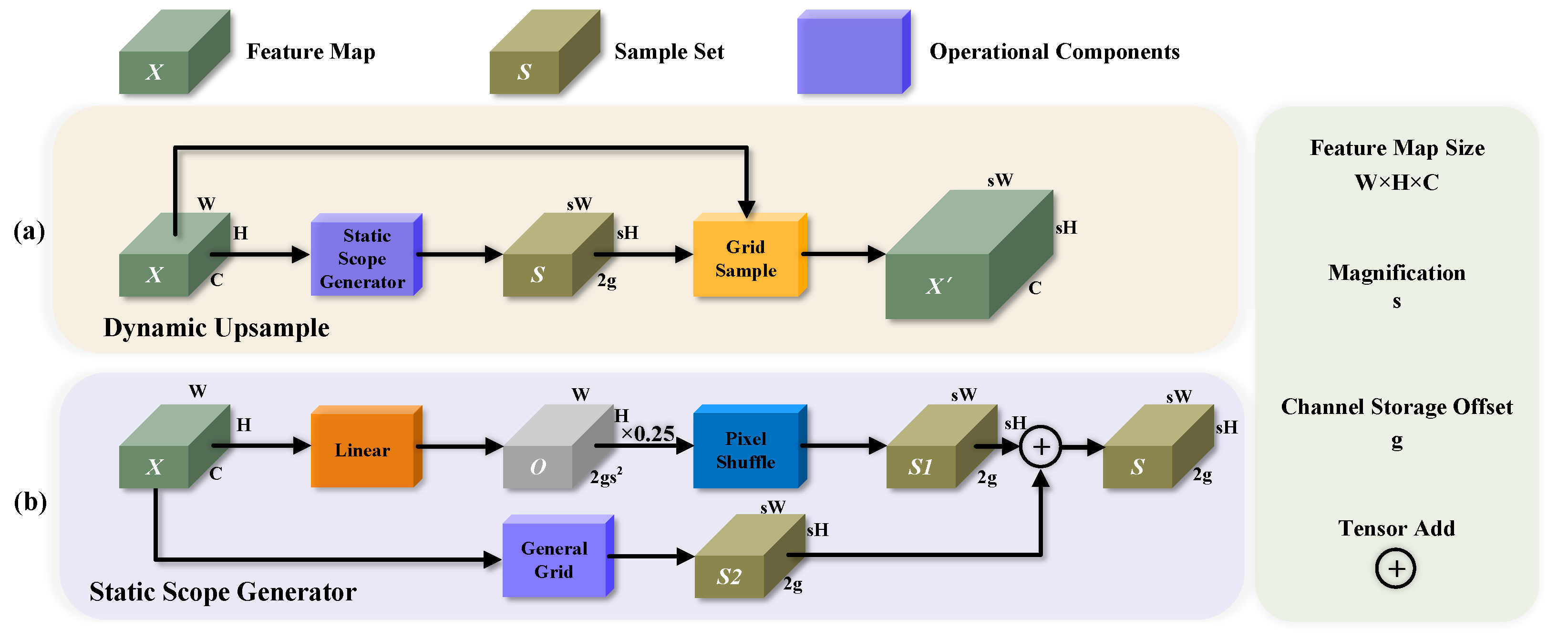

3.5.2. Upsampling Optimization

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Experimental Platform

4.2. Evaluation Indicators

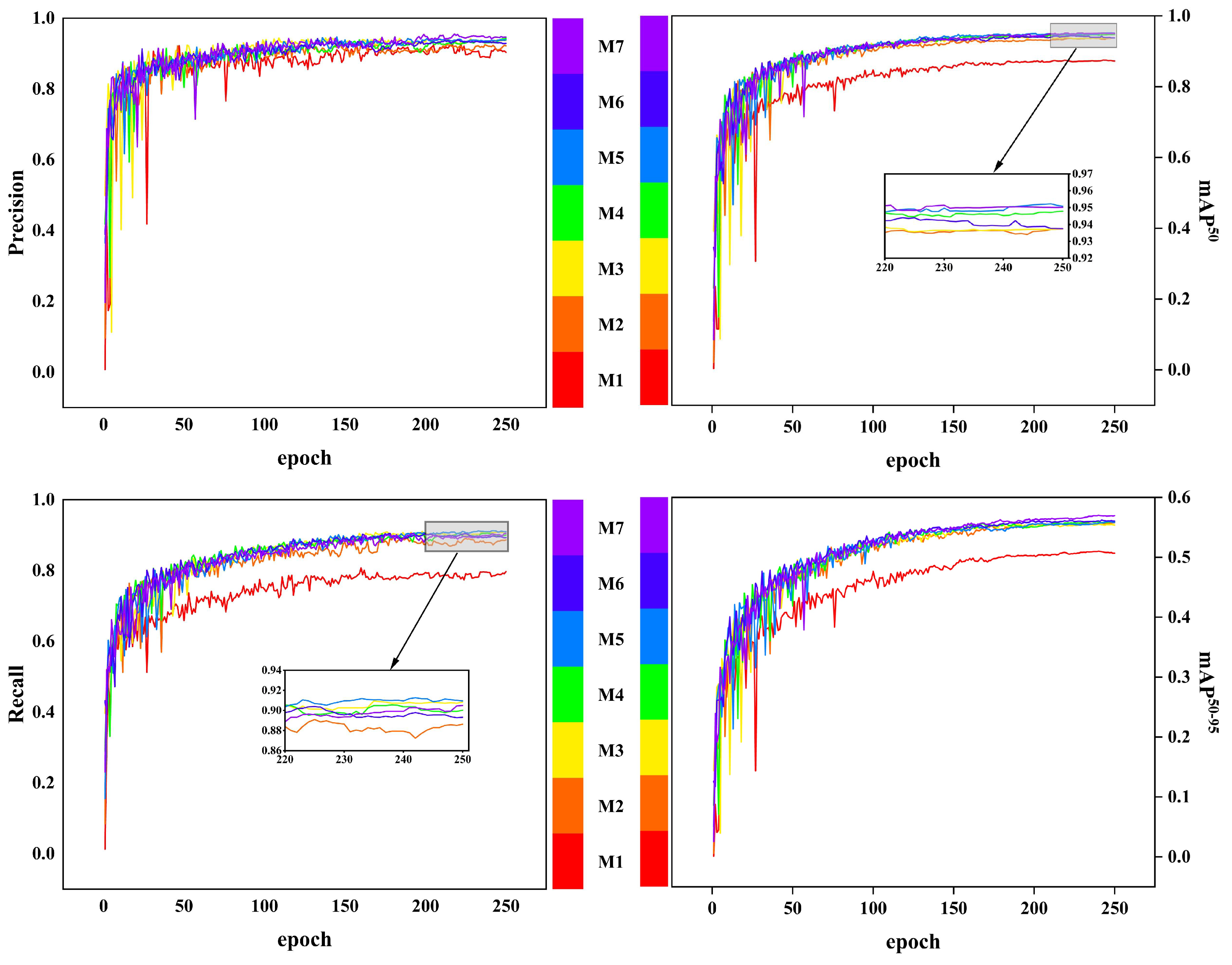

4.3. Ablation Experiments

- M2: Replaced the original FPN with the HRFPN structure.

- M3: Replaced the standard C3k2 module with the proposed C3k2-WT in both the backbone and neck.

- M4: Integrated the SCSA module at the interface between the neck and the detection head.

- M5: Further replaced the default upsampling operator in M4 with Dysample.

- M6: Replaced the standard confidence loss in M4 with the proposed ATFL.

- M7: The final YOLO-CoOp framework, combining all the above modules.

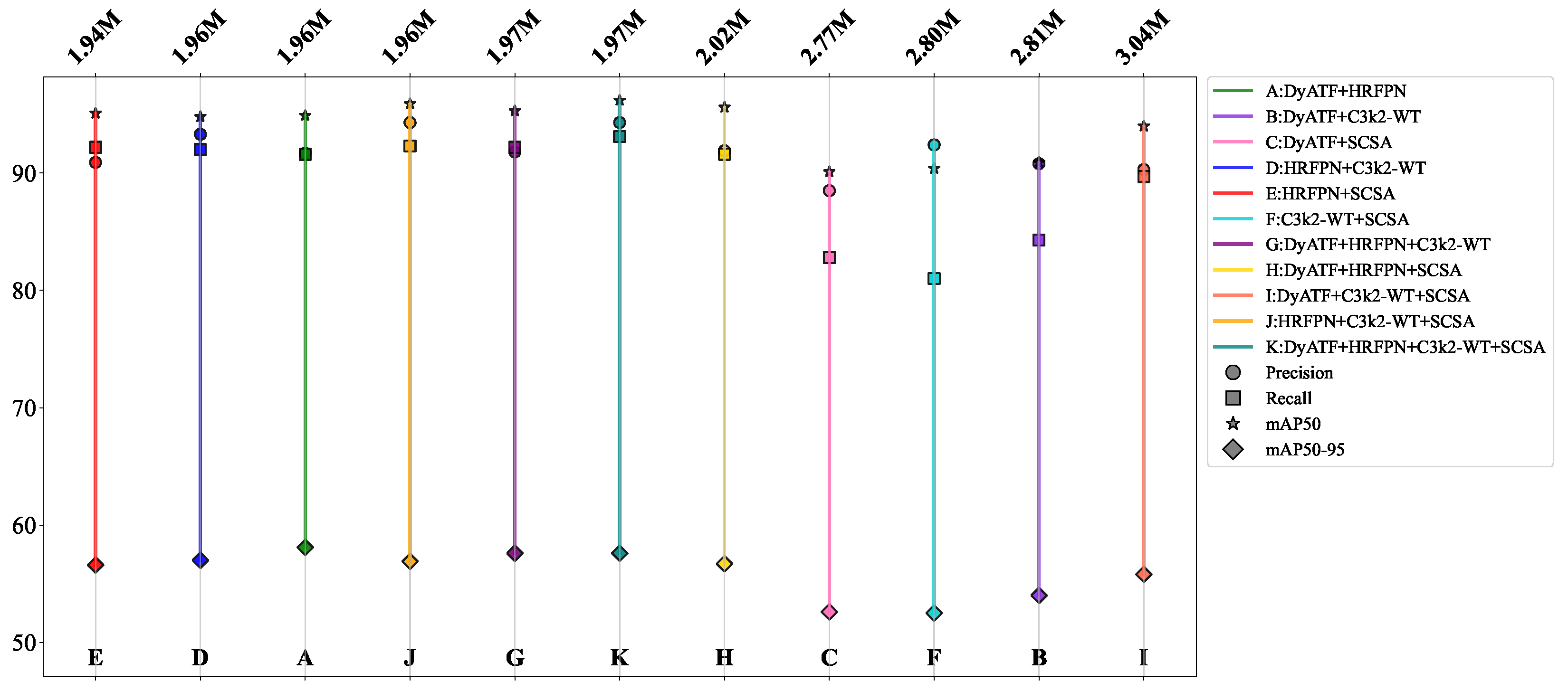

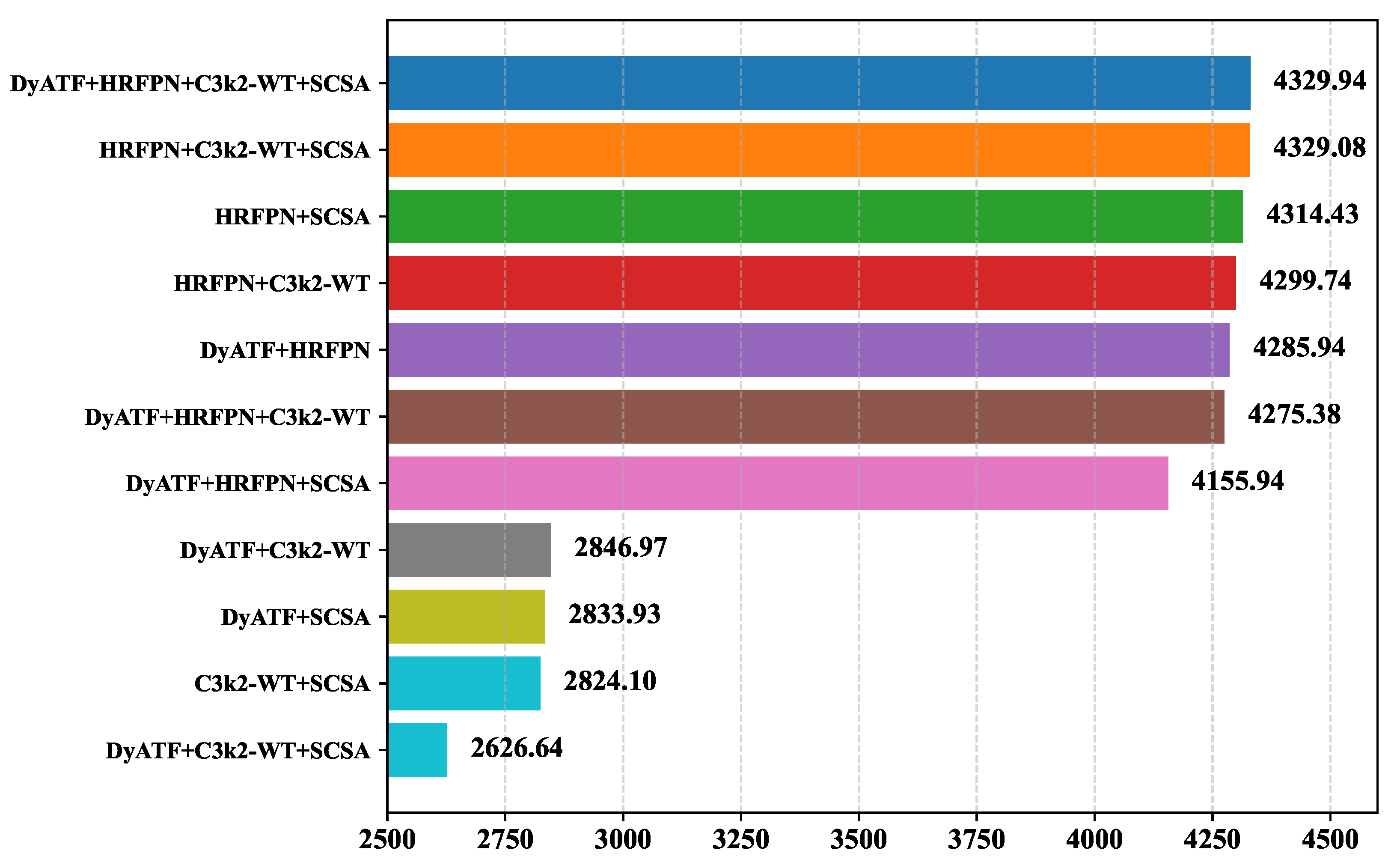

4.4. Collaborative Relationship Validation Experiments

- The HRFPN + DyATF combination achieves the highest mAP50−95 of 58.1%.

- The HRFPN + SCSA combination minimizes the number of parameters to 1.94 M, contributing significantly to model compression.

- The HRFPN + C3k2-WT combination attains the second highest precision of 93.3%, highlighting its effectiveness in improving classification confidence.

- The HRFPN + C3k2-WT + SCSA combination delivers competitive overall performance, ranking among the top configurations.

- The full integration of HRFPN + C3k2-WT + SCSA + DyATF yields the highest precision, recall, and mAP50, while achieving the second highest mAP50−95.

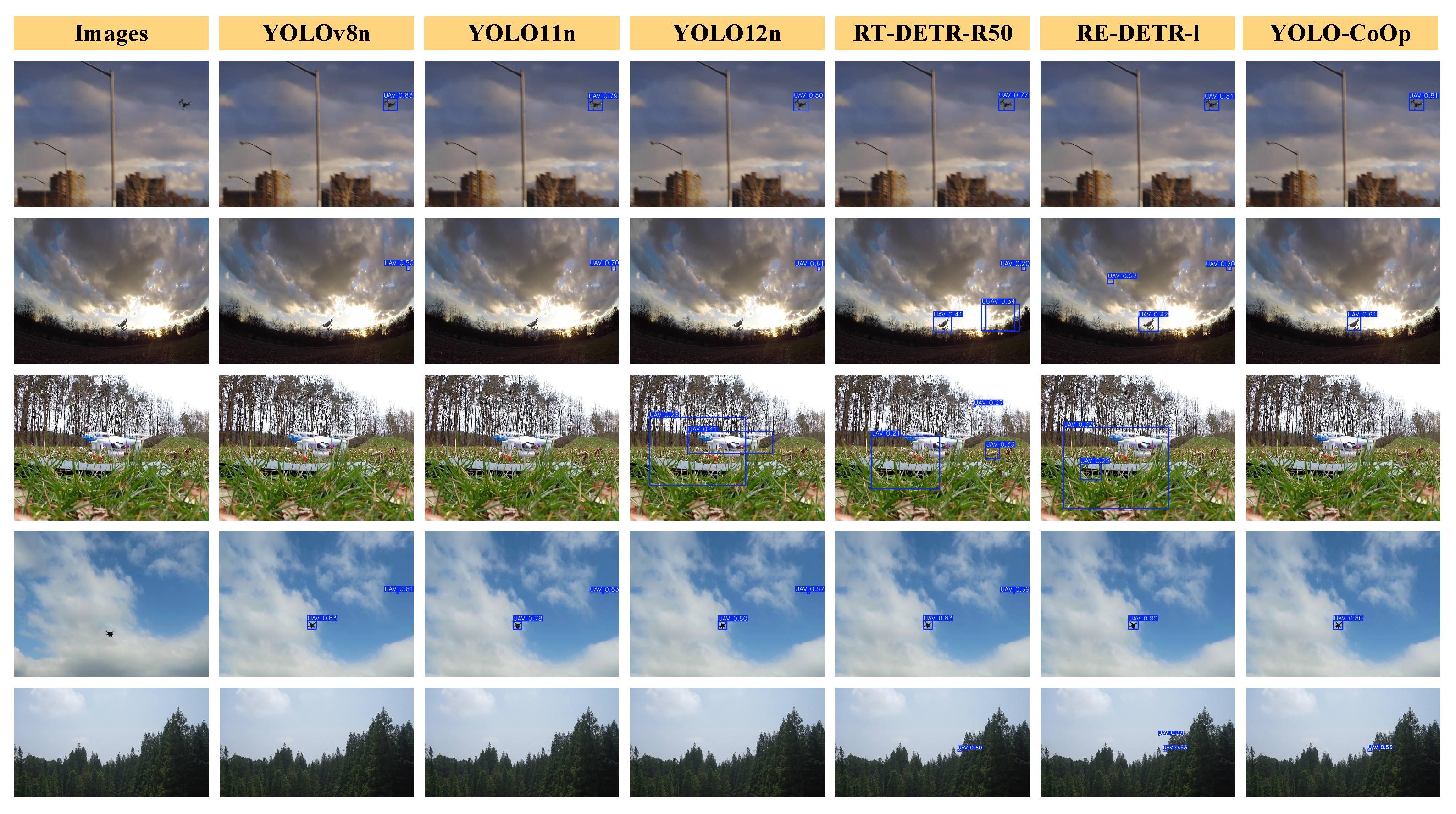

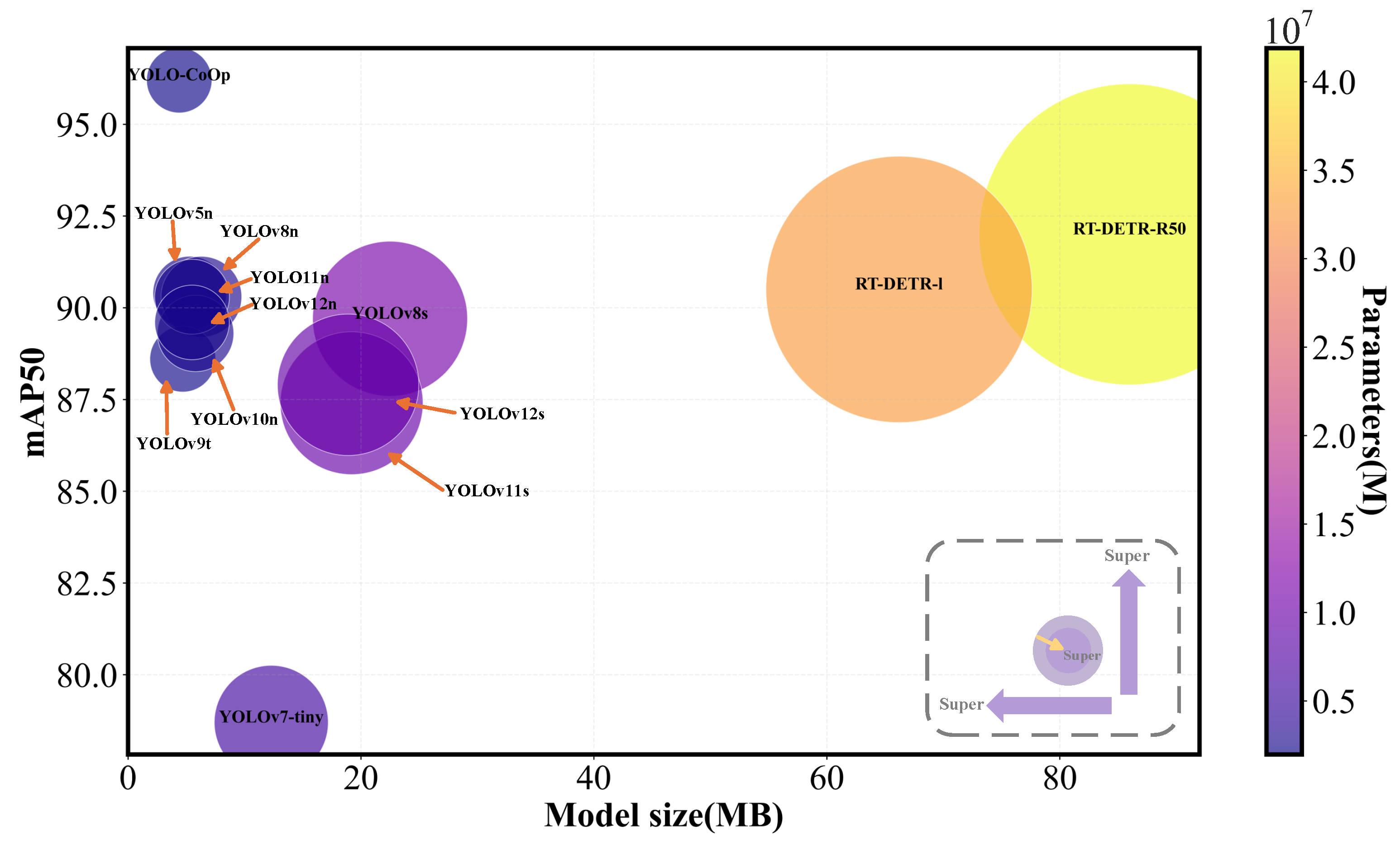

4.5. Comparison Experiments

4.6. Cross-Dataset Validation Experiments

5. Visual Detection in Anti-UAV System

5.1. Experimental Setup

5.2. Quantitative Metrics and Experimental Protocol

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, M.; Zhang, D.; Wang, B.; Li, L. Dynamic Trajectory Planning for Multi-UAV Multi-Mission Operations Using a Hybrid Strategy. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2025, 61, 7369–7386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, D.; Drioli, C.; Ferrin, G.; Foresti, G.L. Acoustic Source Localization from Multirotor UAVs. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 8618–8628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Zhou, X. Autonomous UAV Interception via Augmented Adversarial Inverse Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Autonomous Unmanned Systems (ICAUS 2021); Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 2073–2084. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, B.J.; Stefenon, S.F.; Singh, G.; Freire, R.Z. Hybrid-YOLO for Classification of Insulators Defects in Transmission Lines Based on UAV. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 148, 108982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Qiu, B.; Dong, X.; Ma, J.; Huang, X.; Ahmed, S.; Chandio, F.A. Effect of Operational Parameters of UAV Sprayer on Spray Deposition Pattern in Target and Off-Target Zones During Outer Field Weed Control Application. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 172, 105350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, T.A.; Patrikar, J.; Oliveira, N.L.; Matthews, H.S.; Scherer, S.; Samaras, C. Drone Flight Data Reveal Energy and Greenhouse Gas Emissions Savings for Very Small Package Delivery. Patterns 2022, 3, 100569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchelt, A.; Adrowitzer, A.; Kieseberg, P.; Gollob, C.; Nothdurft, A.; Eresheim, S.; Tschiatschek, S.; Stampfer, K.; Holzinger, A. Exploring Artificial Intelligence for Applications of Drones in Forest Ecology and Management. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 551, 121530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekdad, Y.; Aris, A.; Babun, L.; Fergougui, A.E.; Conti, M.; Lazzeretti, R.; Uluagac, A.S. A Survey on Security and Privacy Issues of UAVs. Comput. Netw. 2023, 224, 109626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vattapparamban, E.; Güvenç, I.; Yurekli, A.I.; Akkaya, K.; Uluağaç, S. Drones for Smart Cities: Issues in Cybersecurity, Privacy, and Public Safety. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing Conference (IWCMC), Paphos, Cyprus, 5–9 September 2016; pp. 216–221. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, N.; Wang, K.; Peng, X.; Yu, X.; Wang, Q.; Xing, J.; Li, G.; Guo, G.; Ye, Q.; Jiao, J.; et al. Anti-UAV: A Large-Scale Benchmark for Vision-Based UAV Tracking. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 25, 486–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Wang, D. Vision-Based Anti-UAV Detection and Tracking. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 25323–25334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souli, N.; Makrigiorgis, R.; Anastasiou, A.; Zacharia, A.; Petrides, P.; Lazanas, A.; Valianti, P.; Kolios, P.; Ellinas, G. Horizonblock: Implementation of an Autonomous Counter-Drone System. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Athens, Greece, 1–4 September 2020; pp. 398–404. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Fan, K.; Ouyang, Q.; Yuan, Y. Acoustic UAV Detection Method Based on Blind Source Separation Framework. Appl. Acoust. 2022, 200, 109057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Wan, Y.; Wu, G.; Li, Y.; Zhou, F.; Wu, Q. An RF-Visual Directional Fusion Framework for Precise UAV Positioning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 36736–36747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tian, J.; Cao, J.; Wang, X. Deep Learning-Based UAV Detection in Pulse-Doppler Radar. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yang, J.; Chen, L.; Li, F.; Feng, Z.; Jia, L.; Li, P. RailVoxelDet: A Lightweight 3-D Object Detection Method for Railway Transportation Driven by Onboard LiDAR Data. IEEE Internet Things 2025, 12, 37175–37189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2012, 25, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtiani, F.; Geers, A.J.; Aflatouni, F. An On-Chip Photonic Deep Neural Network for Image Classification. Nature 2022, 606, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauparas, J.; Anishchenko, I.; Bennett, N.; Bai, H.; Ragotte, R.J.; Milles, L.F.; Wicky, B.I.; Courbet, A.; de Haas, R.J.; Bethel, N.; et al. Robust Deep Learning–Based Protein Sequence Design Using ProteinMPNN. Science 2022, 378, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Ouyang, W.; Wang, X.; Fieguth, P.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Pietikäinen, M. Deep Learning for Generic Object Detection: A Survey. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2020, 128, 261–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Sahoo, D.; Hoi, S.C. Recent Advances in Deep Learning for Object Detection. Neurocomputing 2020, 396, 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich Feature Hierarchies for Accurate Object Detection and Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1440–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot Multibox Detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2016, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Liu, M.; Du, Y.; Zhao, M.; Jia, H.; Guo, Z.; Su, Y.; Lu, D.; Liu, Y. PG-YOLO: An Efficient Detection Algorithm for Pomegranate Before Fruit Thinning. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 134, 108700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kang, X. Mobile-YOLO: An Accurate and Efficient Three-Stage Cascaded Network for Online Fiberglass Fabric Defect Detection. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 134, 108690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zou, Z.; Dan, W. GMS-YOLO: A Lightweight Real-Time Object Detection Algorithm for Pedestrians and Vehicles Under Foggy Conditions. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 23879–23890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.; Leng, C.; Wang, J.; Pei, Z.; Peng, J.; Cheng, I.; Basu, A. MFEL-YOLO for Small Object Detection in UAV Aerial Images. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 291, 128459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, C.; Guo, W.; Zhang, T.; Li, W. CFANet: Efficient Detection of UAV Image Based on Cross-Layer Feature Aggregation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fan, K.; Hou, H.; Liu, C. Real-Time Detection of Drones Using Channel and Layer Pruning, Based on the YOLOv3-SPP3 Deep Learning Algorithm. Micromachines 2022, 13, 2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, S.; Aydin, B. Automated Drone Detection Using YOLOv4. Drones 2021, 5, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Fan, K.; Xu, Z. UAV Identification Based on Improved YOLOv7 Under Foggy Condition. Signal Image Video Process. 2024, 18, 6173–6183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Huang, S.; Jin, D.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Guo, Y. LA-YOLO: An Effective Detection Model for Multi-UAV Under Low Altitude Background. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 055401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Yao, L.; Zhang, C.; Wu, T.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, X.; Zhou, J. Boost UAV-Based Object Detection via Scale-Invariant Feature Disentanglement and Adversarial Learning. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.; Smith, N.; Ghanem, B. A Benchmark and Simulator for UAV Tracking. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2016, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; pp. 445–461. [Google Scholar]

- Du, D.; Zhu, P.; Wen, L.; Bian, X.; Lin, H.; Hu, Q.; Peng, T.; Zheng, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. VisDrone-DET2019: The Vision Meets Drone Object Detection in Image Challenge Results. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshop (ICCVW), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27–28 October 2019; pp. 213–226. [Google Scholar]

- Du, D.; Qi, Y.; Yu, H.; Yang, Y.; Duan, K.; Li, G.; Zhang, W.; Huang, Q.; Tian, Q. The Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Benchmark: Object Detection and Tracking. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 370–386. [Google Scholar]

- Bozcan, I.; Kayacan, E. Au-Air: A Multi-Modal Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Dataset for Low Altitude Traffic Surveillance. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Paris, France, 31 May–31 August 2020; pp. 8504–8510. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, L.; Du, D.; Zhu, P.; Hu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Bo, L.; Lyu, S. Detection, Tracking, and Counting Meets Drones in Crowds: A Benchmark. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 7808–7817. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, P.; Peng, T.; Du, D.; Yu, H.; Zhang, L.; Hu, Q. Graph Regularized Flow Attention Network for Video Animal Counting from Drones. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 5339–5351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Z.; Song, T.; Jin, R.; Jiang, T. An Experimental Evaluation Based on New Air-to-Air Multi-UAV Tracking Dataset. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Unmanned Systems (ICUS), Hefei, China, 13–15 October 2023; pp. 671–676. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, B.; Yao, H.; Zhu, P.; Hu, Q. Visible and Clear: Finding Tiny Objects in Difference Map. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2024, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Yang, J.; Shen, J.; Liang, D.; Ning-Zhong, L.; Zhou, H. TIB-Net: Drone Detection Network with Tiny Iterative Backbone. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 130697–130707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozantsev, A.; Lepetit, V.; Fua, P. Detecting Flying Objects Using a Single Moving Camera. In Proceedings of the IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; Volume 39, pp. 879–892. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, G.S.; Bai, X.; Ding, J.; Zhu, Z.; Belongie, S.; Luo, J.; Datcu, M.; Pelillo, M.; Zhang, L. DOTA: A Large-Scale Dataset for Object Detection in Aerial Images. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 3974–3983. [Google Scholar]

- Suo, J.; Wang, T.; Zhang, X.; Chen, H.; Zhou, W.; Shi, W. HIT-UAV: A High-Altitude Infrared Thermal Dataset for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle-Based Object Detection. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2014, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, W.; Li, Y.; Urtasun, R.; Zemel, R. Understanding the effective receptive field in deep convolutional neural networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1701.04128. [Google Scholar]

- Finder, S.E.; Amoyal, R.; Treister, E.; Freifeld, O. Wavelet Convolutions for Large Receptive Fields. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2024, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 363–380. [Google Scholar]

- Si, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, W.; Dong, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, H. SCSA: Exploring the Synergistic Effects Between Spatial and Channel Attention. Neurocomputing 2025, 634, 129866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Luo, J.; Zhou, M.; Pi, Y. EFLNet: Enhancing Feature Learning Network for Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Lu, H.; Fu, H.; Cao, Z. Learning to Upsample by Learning to Sample. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 2–3 October 2023; pp. 6004–6014. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W.; Caballero, J.; Huszár, F.; Totz, J.; Aitken, A.P.; Bishop, R.; Rueckert, D.; Wang, Z. Real-Time Single Image and Video Super-Resolution Using an Efficient Sub-Pixel Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 1874–1883. [Google Scholar]

| Indicators | Width | Height | Area | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | 4 | 4 | 16 | 1 |

| Median | 16 | 14 | 224 | 1.19 |

| Max | 537 | 462 | 248,094 | 1.16 |

| Mean | 28.57 | 22.56 | 2548.3 | 1.29 |

| Std | 51.09 | 40.24 | 14,512 | 0.43 |

| No. | Training Parameters | Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Epochs | 250 |

| 2 | Batch Size | 16 |

| 3 | Optimizer | Adam |

| 4 | Images Size | |

| 5 | Initial Learning Rate | |

| 6 | Final Learning Rate | |

| 7 | Mosaic | 1 |

| 8 | Close Mosaic | 10 |

| 9 | Momentum | 0.937 |

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 (Ours) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRFPN | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| C3k2-WT | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| SCSA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Dysample | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| ATFL | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Precision | 90.7% | 91.7% | 93.3% | 94.3% | 93.0% | 92.3% | 94.3% |

| Recall | 83.1% | 91.0% | 92.0% | 92.3% | 91.9% | 93.1% | 93.1% |

| mAP50 | 90.3% | 94.5% | 94.8% | 95.9% | 95.6% | 95.4% | 96.2% |

| mAP50−95 | 52.6% | 56.3% | 57.0% | 56.9% | 57.2% | 56.5% | 57.6% |

| Model size | 5.5 MB | 4.3 MB | 4.4 MB | 4.4 MB | 4.4 MB | 4.4 MB | 4.4 MB |

| Parameters | 2.59 M | 1.94 M | 1.96 M | 1.96 M | 1.97 M | 1.96 M | 1.97 M |

| FPS | 83 | 86 | 75.57 | 61.35 | 57.79 | 65 | 56.2 |

| GFLOPs | 6.4 | 9.8 | 10.9 | 10.9 | 10.9 | 10.9 | 10.9 |

| Comb. | DyATF | HRFPN | C3k2-WT | SCSA | Precision | Recall | mAP50 | mAP50−95 | Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two | ✓ | ✓ | 91.7% | 91.6% | 94.9% | 58.1% | 1.96 M | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | 90.8% | 84.3% | 90.9% | 54.0% | 2.81 M | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | 88.5% | 82.8% | 90.1% | 52.6% | 2.77 M | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | 93.3% | 92.0% | 94.8% | 57.0% | 1.96 M | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | 90.9% | 92.2% | 95.1% | 56.6% | 1.94 M | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | 92.4% | 81.0% | 90.4% | 52.5% | 2.80 M | |||

| Three | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 91.8% | 92.2% | 95.3% | 57.6% | 1.97 M | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 91.9% | 91.6% | 95.6% | 56.7% | 2.02 M | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 91.4% | 83.8% | 90.8% | 53.4% | 3.04 M | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 94.3% | 92.3% | 95.9% | 56.9% | 1.96 M | ||

| Four (ours) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 94.3% | 93.1% | 96.2% | 57.6% | 1.97 M |

| Model | Precision | Recall | mAP50 | mAP50−95 | Parameters | Size | GFLOPs | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv5n | 92.5% | 81.7% | 90.4% | 52.7% | 2.50 M | 5.3 MB | 7.2 | 91.12 |

| YOLOv7-tiny | 84.9% | 69.0% | 78.7% | 40.7% | 6.01 M | 12.3 MB | 13.2 | 78.5 |

| YOLOv8n | 90.5% | 83.1% | 90.3% | 53.2% | 3.01 M | 6.3 MB | 8.2 | 97.76 |

| YOLOv8s | 91.9% | 79.6% | 89.7% | 53.1% | 11.1 M | 22.5 MB | 28.6 | 96 |

| YOLOv9t | 87.4% | 81.6% | 88.6% | 51.4% | 2.00 M | 4.7 MB | 7.8 | 55.63 |

| YOLOv10n | 91.2% | 79.3% | 89.3% | 53.1% | 2.70 M | 5.8 MB | 8.4 | 69 |

| YOLO11n | 90.7% | 83.1% | 90.3% | 52.6% | 2.59 M | 5.5 MB | 6.4 | 83 |

| YOLO11s | 87.9% | 78.9% | 87.4% | 50.9% | 9.43 M | 19.2 MB | 21.5 | 85.9 |

| YOLOv12n | 89.7% | 82.9% | 89.6% | 52.0% | 2.57 M | 5.5 MB | 6.5 | 66.46 |

| YOLOv12s | 90.5% | 78.5% | 87.9% | 51.0% | 9.25 M | 18.9 MB | 21.5 | 63.35 |

| RT-DETR-R50 | 93.4% | 88.6% | 92.0% | 41.7% | 41.9 M | 86.0 MB | 130.5 | 39.25 |

| RT-DETR-l | 93.2% | 86.8% | 90.5% | 41.4% | 32.8 M | 66.2 MB | 108 | 42.99 |

| YOLO-CoOp | 94.3% | 93.1% | 96.2% | 57.6% | 1.97 M | 4.4 MB | 10.9 | 56.2 |

| Dataset | Model | Precision | Recall | mAP50 | mAP50−95 | Parameters | Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visdrone | YOLO11n | 43.3% | 32.2% | 31.9% | 18.7% | 2.59 M | 5.5 MB |

| YOLO-CoOp | 45.0% | 35.8% | 36.0% | 21.4% | 1.97 M | 4.4 MB | |

| DUT Anti-UAV | YOLO11n | 89.8% | 78.6% | 86.5% | 56.6% | 2.59 M | 5.5 MB |

| YOLO-CoOp | 93.6% | 84.9% | 91.4% | 60.4% | 1.97 M | 4.4 MB | |

| TIB-Net-Drone | YOLO11n | 83.3% | 79.9% | 82.7% | 35.6% | 2.59 M | 5.5 MB |

| YOLO-CoOp | 89.8% | 92.3% | 92.4% | 38.5% | 1.97 M | 4.4 MB |

| Component | Model/Specification | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Computing Platform | Laptop Computer | NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1650 (4 GB VRAM), Windows 11 Professional |

| Camera Module | Hikvision DS-2ZMN2507C | 2-megapixel (1920 × 1080) 25× optical zoom (4.8–120 mm) 30 fps (60 Hz synchronization) H.265 encoding |

| Tracking Gimbal | HY-MZ17-01A | Horizontal speed: 9–45∘/s Vertical speed: 2.6–13∘/s Positioning accuracy: ±0.1∘ Rotation range: 0–360∘ (horizontal), −60–+60∘ (vertical) Load capacity: ≤20 kg Protection rating: IP66 |

| Distance (m) | Latency (ms) | FPS | GPU Util (%) | GPU Power (W) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 36.13 | 26.0 | 36.52 | 23.13 |

| 40 | 37.22 | 27.2 | 36.42 | 22.67 |

| 60 | 35.39 | 28.2 | 36.72 | 23.25 |

| 80 | 37.47 | 28.1 | 37.46 | 28.07 |

| 120 | 34.49 | 27.7 | 36.00 | 23.59 |

| Zoom (×) | Latency (ms) | FPS | GPU Util (%) | GPU Power (W) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 37.35 | 26.4 | 35.83 | 22.92 |

| 10 | 38.09 | 26.4 | 36.90 | 27.55 |

| 15 | 38.76 | 26.1 | 36.57 | 27.20 |

| 20 | 37.57 | 26.6 | 36.81 | 27.35 |

| 25 | 38.04 | 26.7 | 37.27 | 27.53 |

| Distance (m) | Latency (ms) | FPS | GPU Util (%) | GPU Power (W) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 150 | 36.55 | 27.1 | 35.87 | 23.19 |

| 180 | 37.90 | 26.7 | 35.04 | 28.06 |

| 210 | 35.80 | 28.4 | 38.07 | 28.65 |

| 240 | 37.23 | 27.1 | 37.84 | 28.42 |

| 270 | 35.92 | 27.5 | 36.13 | 24.31 |

| 300 | 36.17 | 27.5 | 35.80 | 23.76 |

| Test Scenario | Latency (ms) | FPS | GPU Util (%) | GPU Power (W) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Target | 49.68 | 20.2 | 37.20 | 20.59 |

| Complex Background | 47.78 | 20.9 | 36.98 | 19.55 |

| High-Speed Maneuver | 47.23 | 20.7 | 36.89 | 21.40 |

| Backlighting | 47.71 | 21.0 | 37.28 | 19.33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, Z.; Fan, K.; Ye, J.; Xu, Z.; Wei, Y. A Lightweight Multi-Module Collaborative Optimization Framework for Detecting Small Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Anti-Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Systems. Drones 2026, 10, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010020

Chen Z, Fan K, Ye J, Xu Z, Wei Y. A Lightweight Multi-Module Collaborative Optimization Framework for Detecting Small Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Anti-Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Systems. Drones. 2026; 10(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Zhiling, Kuangang Fan, Jingzhen Ye, Zhitao Xu, and Yupeng Wei. 2026. "A Lightweight Multi-Module Collaborative Optimization Framework for Detecting Small Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Anti-Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Systems" Drones 10, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010020

APA StyleChen, Z., Fan, K., Ye, J., Xu, Z., & Wei, Y. (2026). A Lightweight Multi-Module Collaborative Optimization Framework for Detecting Small Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Anti-Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Systems. Drones, 10(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010020