Public Acceptance of Remotely Piloted Aircraft (RPA) Operations in Sydney Harbour

Highlights

- Public attitudes toward RPA operations are shaped by how people weigh the perceived benefits against the potential risks, particularly the extent of societal benefits and the level of trust they place in the operators. Privacy risk is significantly more important than mid-air collision and ground impact safety risk.

- These factors help explain why RPA activities related to the government’s environmental monitoring received the strongest public support. In contrast, recreational flying was showed the lowest acceptance, and commercial filming sits between these two.

- Communicating the societal benefits of RPA operations and ensuring high pilot competency are essential for improving public acceptance, as both influence perceived privacy risks and trust.

- As RPA usage grows, continued public education about regulations and responsible operation is critical to discourage unsafe recreational use. Prioritising trust, demonstrating clear benefits, and addressing privacy concerns will be key to strengthening overall acceptance of RPA activities.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Analytical Framework

2.2. Studied Factors

2.3. Literature Gap

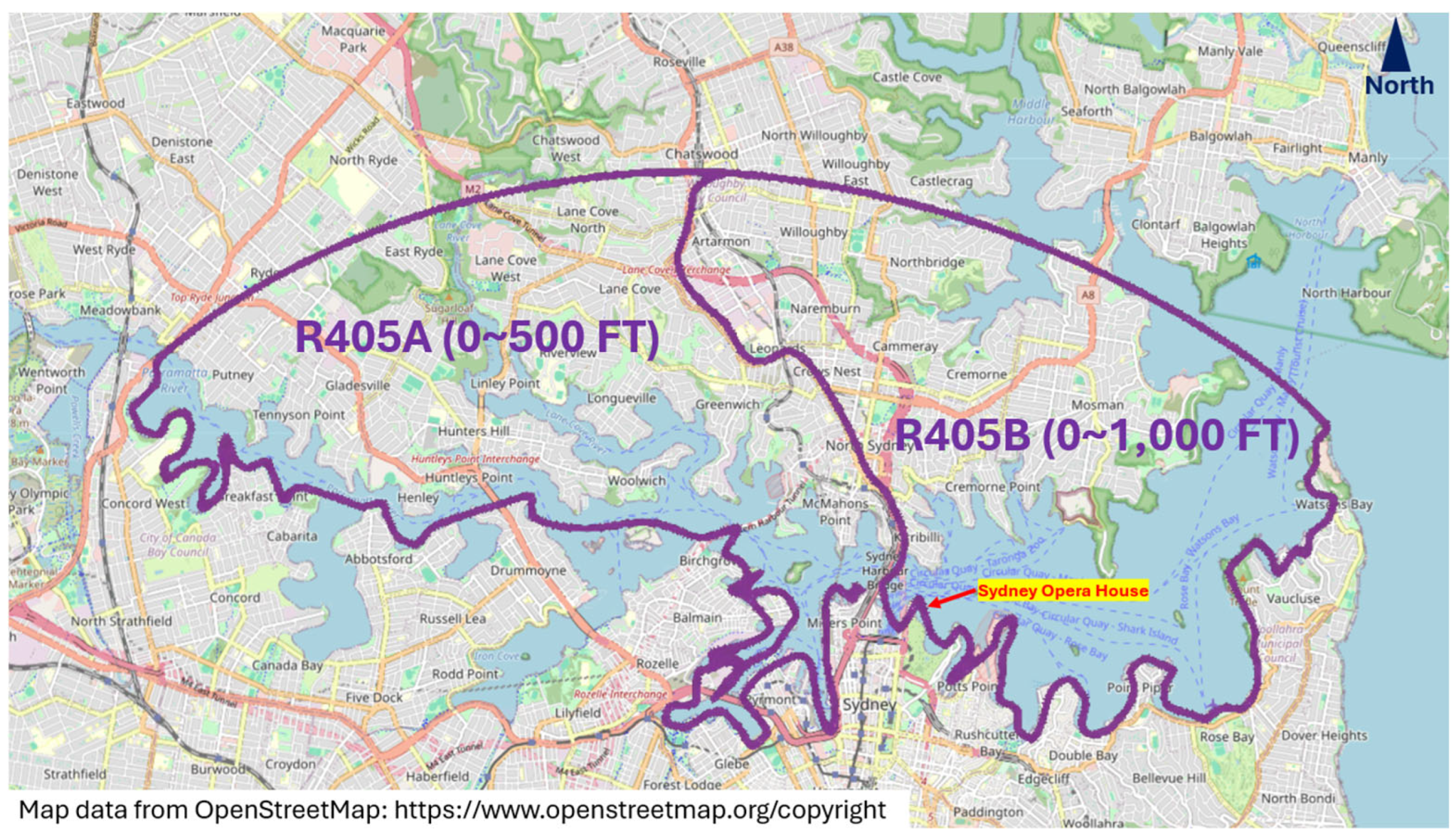

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Survey Design

3.3. Data Analysis Method

4. Results

4.1. Gender

4.2. Age

4.3. Previous Experience

4.4. Knowledge Levels

4.5. Perceived Benefits

4.6. Trust

4.7. Noise

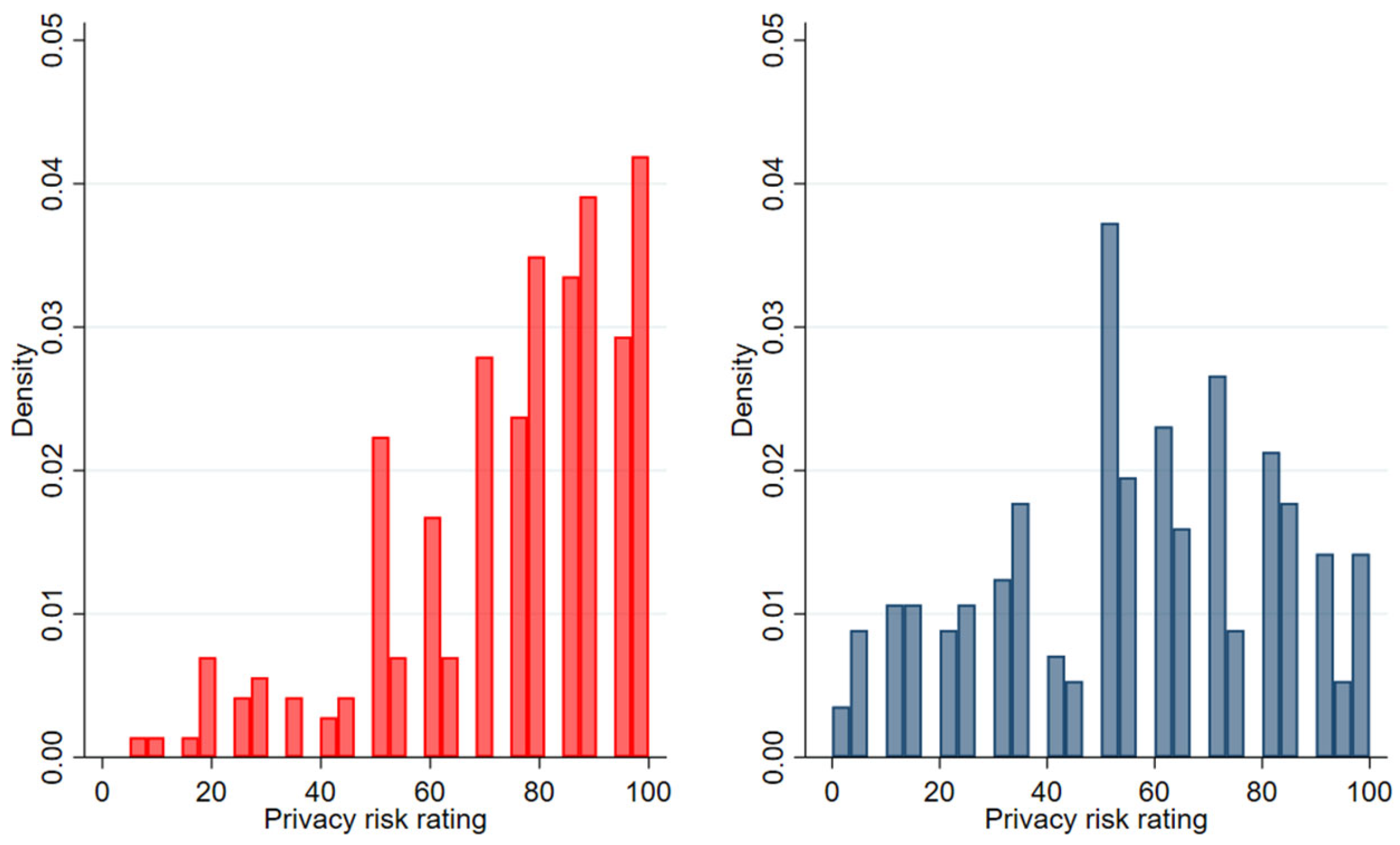

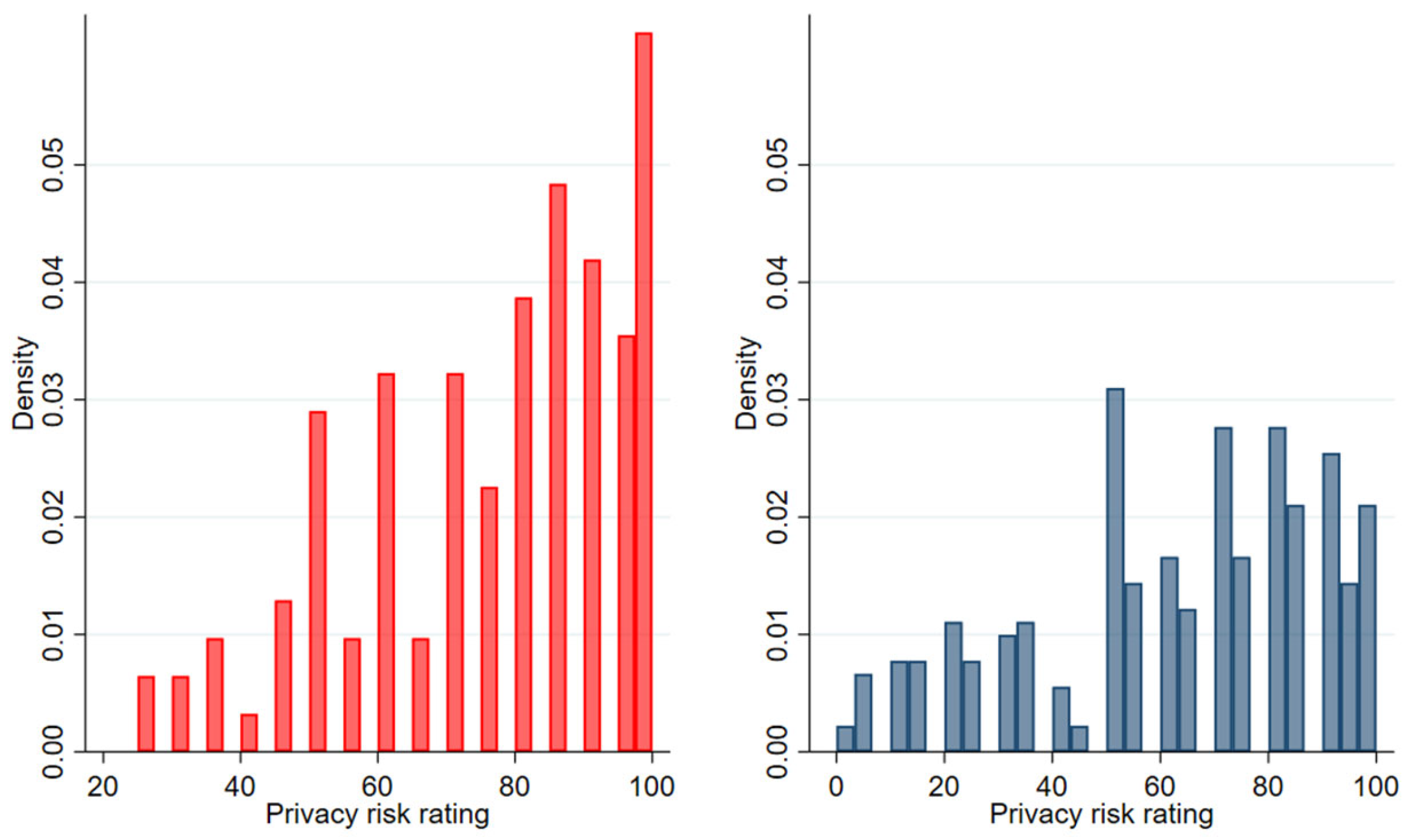

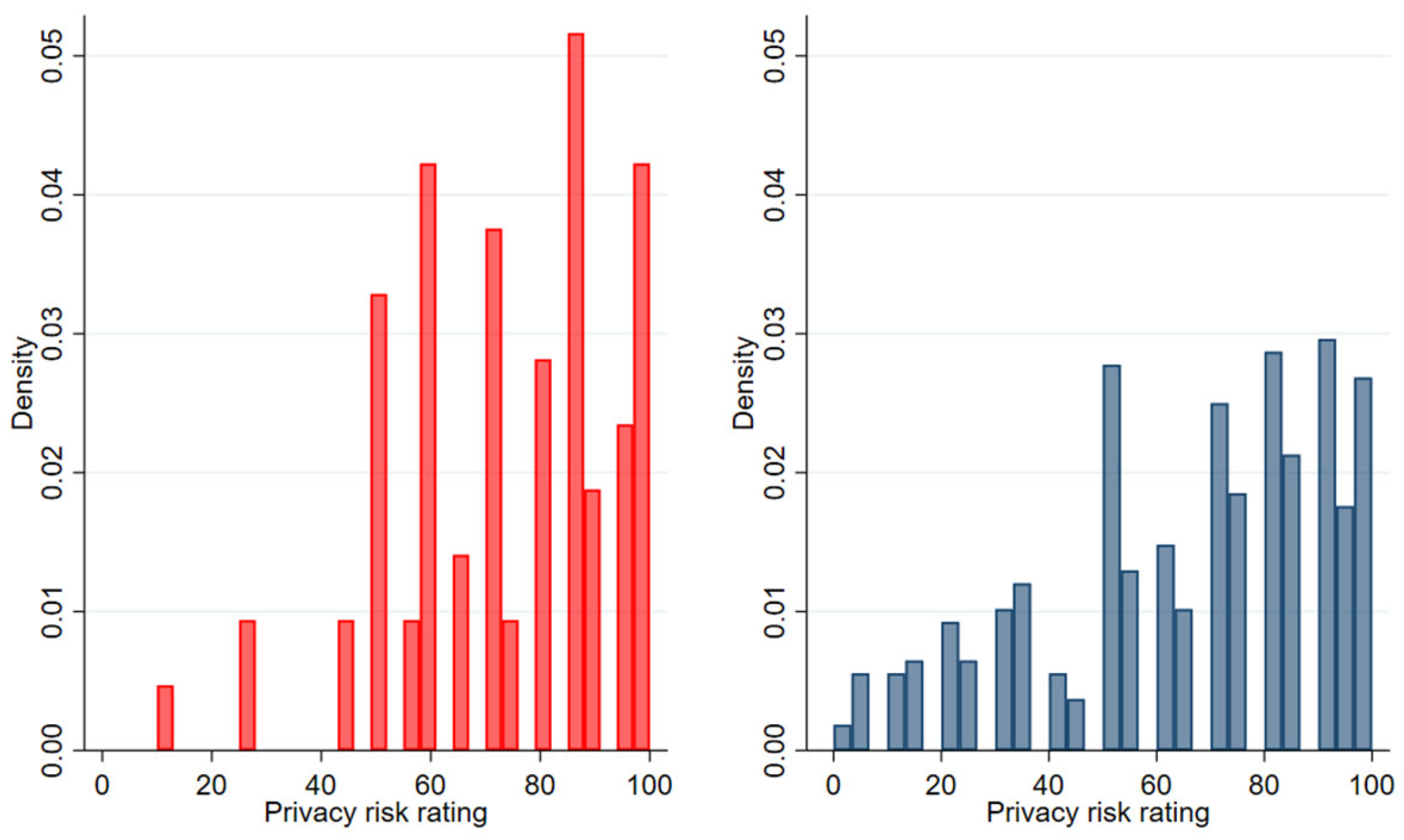

4.8. Risk Perception

4.9. Regression Performance

5. Discussions and Conclusions

5.1. Summary of Findings

5.2. Policy Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- CASA. Beyond Visual Line-of-Sight Operations. Available online: https://www.casa.gov.au/drones/flight-authorisations/beyond-visual-line-sight-operations (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- CASA. Specific Operations Risk Assessment. Available online: https://www.casa.gov.au/drones/flight-authorisations/beyond-visual-line-sight-operations/specific-operations-risk-assessment (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- CASA. Automated Airspace Authorisations. Available online: https://www.casa.gov.au/drones/flight-authorisations/automated-airspace-authorisations (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Crahay, F.-X.; Rampat, R.; Tonglet, M.; Rakic, J.-M. Drones’ Side Effect: Facial and Ocular Trauma Caused by an Aerial Drone. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e238316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasprzyk, P.J.; Konert, A. Reporting and Investigation of Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Accidents and Serious Incidents. Regulatory Perspective. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2021, 103, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarr, A.A.; Tarr, J.-A. Personal Injury, Property Damage, Trespass and Nuisance. In Drone Law and Policy; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 167–182. ISBN 978-1-003-02803-1. [Google Scholar]

- Clothier, R.A.; Greer, D.A.; Greer, D.G.; Mehta, A.M. Risk Perception and the Public Acceptance of Drones. Risk Anal. 2015, 35, 1167–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasri, M.; Maghrebi, M. Factors Affecting Unmanned Aerial Vehicles’ Safety: A Post-Occurrence Exploratory Data Analysis of Drones’ Accidents and Incidents in Australia. Saf. Sci. 2021, 139, 105273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Safany, R.; Bromfield, M.A. A Human Factors Accident Analysis Framework for UAV Loss of Control in Flight. Aeronaut. J. 2025, 129, 1723–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xiao, C.-Y.; Zhang, Z.-G. Analysis and Empirical Study of Factors Influencing Urban Residents’ Acceptance of Routine Drone Deliveries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASA. Annual Report 2022–2023. Available online: https://www.casa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-10/casa-annual-report-2022-2023.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- CASA. Civil Aviation Safety Regulations 1998. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/F1998B00220/latest/text/3 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- CASA. Drone Weight Categories and Requirements. Available online: https://www.casa.gov.au/drones/operator-accreditation-certificate/drone-weight-categories-and-requirements (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- CASA. Drone Rules. Available online: https://www.casa.gov.au/knowyourdrone/drone-rules (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Otway, H.J.; Von Winterfeldt, D. Beyond Acceptable Risk: On the Social Acceptability of Technologies. Policy Sci. 1982, 14, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, B. Public Acceptance of Drones: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practice. Technol. Soc. 2019, 59, 101180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launiala, A. How Much Can a KAP Survey Tell Us about People’s Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices? Some Observations from Medical Anthropology Research on Malaria in Pregnancy in Malawi. Anthropol. Matters 1970, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miethe, T.D.; Lieberman, J.D.; Sakiyama, M.; Troshynski, E.I. Public Attitudes About Aerial Drone Activities: Results of a National Survey. Available online: https://www.unlv.edu/sites/default/files/page_files/27/Research-PublicAttitudesaboutAerialDroneActivities.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Nelson, J.R.; Grubesic, T.H.; Wallace, D.; Chamberlain, A.W. The View from Above: A Survey of the Public’s Perception of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Privacy. J. Urban Technol. 2019, 26, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eißfeldt, H.; Vogelpohl, V. Drone Acceptance and Noise Concerns-Some Findings. In Proceedings of the 20th International Symposium on Aviation Psychology, Dayton, OH, USA, 7–10 May 2019; pp. 198–204. [Google Scholar]

- Boucher, P. ‘You Wouldn’t Have Your Granny Using Them’: Drawing Boundaries Between Acceptable and Unacceptable Applications of Civil Drones. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2016, 22, 1391–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.K.; Ji, Y.G. Investigating the Importance of Trust on Adopting an Autonomous Vehicle. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2015, 31, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.; Bracken-Roche, C. Understanding Public Opinion of UAVs in Canada: A 2014 Analysis of Survey Data and Its Policy Implications. J. Unmanned Veh. Syst. 2015, 3, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellermann, R.; Biehle, T.; Fischer, L. Drones for parcel and passenger transportation: A literature review. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 4, 100088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacSween, S. A Public Opinion Survey-Unmanned Aerial Vehicles for Cargo, Commercial, and Passenger Transportation. In Proceedings of the 2nd AIAA “Unmanned Unlimited” Conference and Workshop & Exhibit, San Diego, CA, USA, 15–18 September 2003; p. 6519. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, S.; Tamilselvan, G.; Winter, S.R.; Milner, M.N.; Anania, E.C.; Sperlak, L.; Marte, D.A. Public Perception of UAS Privacy Concerns: A Gender Comparison. J. Unmanned Veh. Syst. 2018, 6, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakiyama, M.; Miethe, T.D.; Lieberman, J.D.; Heen, M.S.J.; Tuttle, O. Big Hover or Big Brother? Public Attitudes about Drone Usage in Domestic Policing Activities. Secur. J. 2017, 30, 1027–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, Y. Study Reveals Unconscious Gender and Racial Dynamics Influence Drone Use. Available online: https://liberalarts.vt.edu/news/articles/2018/10/study-reveals-unconscious-gender-and-racial-dynamics-influence-d.html (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Gut, K. Drones and Gender. Available online: https://transportgenderobservatory.eu/2021/08/11/drones-and-gender (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Stolz, M.; Papenfuß, A.; Dunkel, F.; Linhuber, E. Harmonized Skies: A Survey on Drone Acceptance across Europe. Drones 2024, 8, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komasová, S.; Tesař, J.; Soukup, P. Perception of Drone Related Risks in Czech Society. Technol. Soc. 2020, 61, 101252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eißfeldt, H. Sustainable Urban Air Mobility Supported with Participatory Noise Sensing. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waris, I.; Ali, R.; Nayyar, A.; Baz, M.; Liu, R.; Hameed, I. An Empirical Evaluation of Customers’ Adoption of Drone Food Delivery Services: An Extended Technology Acceptance Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Dickinson, J.E.; Marsden, G.; Cherrett, T.; Oakey, A.; Grote, M. Public Acceptance of the Use of Drones for Logistics: The State of Play and Moving towards More Informed Debate. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin Tan, L.K.; Lim, B.C.; Park, G.; Low, K.H.; Seng Yeo, V.C. Public Acceptance of Drone Applications in a Highly Urbanized Environment. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucini-Paioni, A.; Busicchia, F.; Rossi-Lamastra, C. What Do People Want? An Analysis of Citizens’ Willingness to Use Advanced Air Mobility in Italy. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2024, 31, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herron, K.G.; Smith, H.C.J.; Silva, C.L. US Public Perspectives on Privacy, Security, and Unmanned Aircraft Systems; Center for Risk and Crisis Management: Wien, Austria; Center for Applied Social Research: Norman, OK, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- End, A.; Barzantny, C.; Stolz, M.; Grupe, P.; Schmidt, R.; Papenfuß, A.; Eißfeldt, H. Public Acceptance of Civilian Drones and Air Taxis in Germany: A Comprehensive Overview. CEAS Aeronaut. J. 2025, 16, 745–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicek, D.; Kantarci, B.; Schillo, S. A Comparative Review of User Acceptance Factors for Drones and Sidewalk Robots in Autonomous Last Mile Delivery. Green Energy Intell. Transp. 2025, 4, 100310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhang, Y. Fostering Drivers’ Trust in Automated Driving Styles: The Role of Driver Perception of Automated Driving Maneuvers. Hum. Factors 2024, 66, 1961–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikaraishi, M.; Khan, D.; Yasuda, B.; Fujiwara, A. Risk Perception and Social Acceptability of Autonomous Vehicles: A Case Study in Hiroshima, Japan. Transp. Policy 2020, 98, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T. Psychological Factors Affecting Potential Users’ Intention to Use Autonomous Vehicles. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Saraceni, A. Consumer Acceptance of Drone-Based Technology for Last Mile Delivery. Res. Transp. Econ. 2024, 103, 101404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhothali, G.T.; Mavondo, F.T.; Alyoubi, B.A.; Algethami, H. Consumer Acceptance of Drones for Last-Mile Delivery in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klauser, F.; Pedrozo, S. Big Data from the Sky: Popular Perceptions of Private Drones in Switzerland. Geogr. Helv. 2017, 72, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xia, H.; Yao, Y.; Huang, Y. Flying Eyes and Hidden Controllers: A Qualitative Study of People’s Privacy Perceptions of Civilian Drones in The US. Proc. Priv. Enhancing Technol. 2016, 2016, 172–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Real, C.; Díaz-Fernández, A.M. Lifeguards in the Sky: Examining the Public Acceptance of Beach-Rescue Drones. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letterman, C.; Schanzer, D.; Pitts, W.; Ladd, K.; Holloway, J.; Mitchell, S.; Kaydos-Daniels, S.C. Unmanned Aircraft and the Human Element: Public Perceptions and First Responder Concerns. In Technical Report; Institution for Homeland Security Solutions: Durham, NC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, A. Public Perception of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Available online: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=atgrads (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Airservices Australia Aeronautical Information Package (AIP). Available online: https://www.airservicesaustralia.com/aip/aip.asp?pg=10 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- CASA. Approval and Permission for Operation of RPA Within Sydney Harbour Restricted Airspace R405A/B Instrument 2023. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/F2023N00533/latest/text (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Guardian Drone Crash on Sydney Harbour Bridge Investigated. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/oct/05/drone-crash-on-sydney-harbour-bridge-investigated (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Insurance Business Australia Far out Friday: Attack of the Drones. Available online: https://www.insurancebusinessmag.com/au/news/breaking-news/far-out-friday-attack-of-the-drones-68015.aspx (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Guardian Footage of Public Drone Landing on Australian Navy Ship Appears on Chinese Social Media. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2024/dec/17/china-drone-landing-australian-navy-ship-weibo-social-media-garden-island-sydney (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- CASA. Drone Flyer Quiz. Available online: https://www.casa.gov.au/webform/droneflyer-quiz (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Hahn, E.D.; Soyer, R. Probit and Logit Models: Differences in the Multivariate Realm. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 2005, 67, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Melo, S.; Silva, F.; Abbasi, M.; Ahani, P.; Macedo, J. Public Acceptance of the Use of Drones in City Logistics: A Citizen-Centric Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Za’im Sahul Hameed, M.; Nordin, R.; Ismail, A.; Zulkifley, M.A.; Sham, A.S.H.; Sabudin, R.Z.A.R.; Zailani, M.A.H.; Saiboon, I.M.; Mahdy, Z.A. Acceptance of Medical Drone Technology and Its Determinant Factors among Public and Healthcare Personnel in a Malaysian Urban Environment: Knowledge, Attitude, and Perception. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1199234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzmann, P.; Wankmüller, C.; Globocnik, D.; Schwarz, E.J. Drones to the Rescue? Exploring Rescue Workers’ Behavioral Intention to Adopt Drones in Mountain Rescue Missions. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2021, 51, 381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiebert, B.; Nouvet, E.; Jeyabalan, V.; Donelle, L. The Application of Drones in Healthcare and Health-Related Services in North America: A Scoping Review. Drones 2020, 4, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira, S.; Cauchard, J.R. Integrating Drones in Response to Public Health Emergencies: A Combined Framework to Explore Technology Acceptance. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1019626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zailani, M.A.; Sabudin, R.Z.A.R.; Rahman, R.A.; Saiboon, I.M.; Ismail, A.; Mahdy, Z.A. Drones for Medical Products Transportation in Obstetric Emergencies: A Systematic Review and Framework For Future Research. Res. Sq 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkert, R.; Bushell, J. Managing the Drone Revolution: A Systematic Literature Review into the Current Use of Airborne Drones and Future Strategic Directions for Their Effective Control. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2020, 89, 101929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.T.; Duarte, S.P.; Melo, S.; Witkowska-Konieczny, A.; Giannuzzi, M.; Lobo, A. Attitudes towards Urban Air Mobility for E-Commerce Deliveries: An Exploratory Survey Comparing European Regions. Aerospace 2023, 10, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.; Biocca, F.; Lee, T.; Park, K.; Rhee, J. Effects of Human Connection through Social Drones and Perceived Safety. Adv. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2018, 2018, 9280581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivošević, J.; Ganić, E.; Petošić, A.; Radišić, T. Comparative UAV Noise-Impact Assessments through Survey and Noise Measurements. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, Y.-T.; Chi Yat, W.; Lau, Y. Preliminary Study of Drone Delivery Systems in Hong Kong. In Artificial Intelligence and Communication Technologies; Hiranwal, S., Mathur, G., Eds.; Soft Computing Research Society: New Delhi, India, 2022; pp. 305–317. ISBN 978-81-955020-5-9. [Google Scholar]

- Torija, A.J.; Li, Z.; Self, R.H. Effects of a Hovering Unmanned Aerial Vehicle on Urban Soundscapes Perception. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 78, 102195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäffer, B.; Pieren, R.; Heutschi, K.; Wunderli, J.M.; Becker, S. Drone Noise Emission Characteristics and Noise Effects on Humans—A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensher, D.A.; Rose, J.M.; Greene, W.H. Applied Choice Analysis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; ISBN 1-316-30034-X. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, D.G.; Bland, J.M. Statistics Notes: Diagnostic Tests 1: Sensitivity and Specificity. BMJ 1994, 308, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASA. Validating the Benefits of Increased Drone Uptake for Australia: Geographic, Demographic and Social Insights. Available online: https://www.drones.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/validating-the-benefits-of-increased-drone-uptake-for-australia-final-report.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025).

| Ref | Factor(s) | Finding(s) |

|---|---|---|

| [7] | Knowledge levels | Due to the lack of knowledge and experience with RPA, the public acceptance toward RPA operations is limited. In general, no significant relationship is observed. |

| [18] | Perceived benefits (+) Knowledge levels (+) Gender (+) | RPA are not well-accepted at present except for public safety and scientific research applications. Commercial and hobby uses are not supported. Knowledge possessed by the public regarding the applications of RPA can affect their acceptance of this technology. The public sees RPA as a risky technology that directly interferes with their privacy. Women are less supportive of RPA use and more concerned about privacy than men. |

| [20] | Perceived benefits (+) Knowledge levels | A large majority know about RPA and associate them with military operations. The greatest support for civil RPA operations in this survey comes from knowing that RPAs are utilised for emergency and environmental activities, while surveillance and package deliveries were less supported. A lack of knowledge of RPA technology was influential in determining the acceptance of RPA in the eyes of the general public, although no relationship has been specified. |

| [21] | Previous experience (+) Knowledge levels (+) | Individuals with previous experience using RPA may have increased knowledge of RPA regulations and are therefore more likely to accept such operations. UAV use for recreational, commercial, or public management purposes poses significant implications for personal privacy, especially for an uninformed public. |

| [22] | Knowledge levels (+) Gender (+) Noise (−) Privacy risk (−) | More than half of participants expressed that noise exposure would be a potential risk of RPA usage, and it was also found that the potential violation of privacy was the highest concern of participants. It was shown that information on RPA has positive effects on both reducing concerns and improving acceptance. Male respondents are more accepting toward civil RPA operations compared to females. Noise concerns are confirmed as an important factor for the acceptance of civil RPA, although the relationship has not been specified. Among those not concerned about noise, their concerns about the violation of privacy are the major factor. |

| [23] | Perceived benefits (+) Trust (+) Privacy risk (−) | Increase in benefits of RPA operations to society increases acceptance. Increase in trust in the user and the level of control and regulations increases acceptance. Risk of privacy breached was of concern to many participants. |

| [25] | Perceived benefits (+) Gender (+) | Public support of RPA leaned toward its usage for emergency services for security and safety, as opposed to private sector use. Men are more likely to accept the use of RPA for law enforcement applications. |

| [26] | Perceived benefits (+) Usefulness (+) Noise (−) | Safety, environmental friendliness, and the usefulness of the technology result in increased acceptance. Higher noise levels lead to lower acceptance. |

| [27] | Social factors | Job losses for pilots resulted in concern among the public, influencing the acceptance of the technology and this is not due to the risks associated with the technology. Social factors have an influence on the acceptance of RPA in the public domain, although no direction has been found. |

| [28] | Gender (+) | Females tend to be more risk-averse and more cautious with privacy concerns. |

| [29] | Age (+) Gender (+) | Older people are more supportive of the use of RPA compared to younger people, especially for rescue and emergency uses. Women are less supportive of RPA use and more concerned about privacy than men. |

| [32] | Age (−) Perceived risks (−) Knowledge levels (+) Noise (−) | Privacy and safety risks emerge as the main concerns, whereas noise is viewed as a relatively minor issue. Greater RPA knowledge levels predict stronger acceptance, while age is the most influential factor shaping perceived risks. |

| [33] | Perceived benefits (+) | There is a high approval rate for RPAs that serve public interests, such as rescue operations and traffic monitoring. In contrast, private RPA operations were met with lower rates of approval, mainly due to privacy concerns. |

| [36] | Knowledge levels (+) | RPA knowledge emerges as one of the strongest predictors of acceptance, with individuals who are more familiar with RPA showing higher support and reduced concern, especially regarding privacy and safety risks. |

| [37] | Perceived risk (−) Perceived benefits (+) Knowledge levels (+) | The public in Singapore generally has good knowledge of RPA, but acceptance varies strongly by context. Acceptance in residential settings is driven primarily by perceived risks, whereas acceptance in commercial, industrial, and recreational areas is shaped more by perceived benefits. The public sees clear advantages in RPA use, yet safety and privacy concerns remain key barriers in sensitive environments. |

| [39] | Perceived benefits (+) | There is greater public support for RPA operations that pose benefits to the society. Many felt that benefits of these RPA operations outweigh the risks. |

| [45] | Perceived risks (−) | Perceived risks (privacy, safety, noise, and financial concerns) do not significantly reduce acceptance overall; however, privacy risk becomes influential among users with previous RPA experience, and safety risk has a stronger negative effect among female respondents. |

| [46] | Perceived risks (−) | Perceived privacy risk is a major barrier to RPA delivery acceptance, as it significantly lowers performance expectancy, effort expectancy, facilitating conditions, and social influence. Conversely, performance expectancy and facilitating conditions exert strong positive effects on attitudes toward RPA delivery, whereas social influence and effort expectancy do not show significant contributions. Consumers are willing to adopt RPA delivery when they view it as beneficial and supported by adequate infrastructure, yet privacy concerns remain the most substantial obstacle to acceptance. |

| [47] | Perceived benefits (+) Privacy risk | Public perception of RPA in Switzerland was dependent on the purpose and location of usage. The public, in general, accepts RPA for military and policing use, but was generally not in favour of commercial and private uses of RPA. Privacy risk only partially explains the social acceptance of RPA usage, although no specific direction has been specified. |

| [49] | Perceived benefits (+) Perceived risks (−) | Perceived benefits (e.g., faster rescue response, improved safety outcomes, enhanced surveillance coverage) significantly increase public acceptance. In contrast, perceived risks (e.g., fears of RPA being dangerous objects, concerns about physical harm, being frightened by low-flying devices, general discomfort with their presence) significantly decrease public acceptance. |

| [50] | Perceived benefits (+) | More than half of the general public supported the applications of RPA, but demonstrated higher support for applications such as homeland security, law enforcement, search and rescue, and commercial applications. |

| [51] | Perceived benefits (+) | Public perception of RPA in carrying cargo and passengers found that there was immense support for RPA in delivering cargo. In contrast, the use of unmanned RPA in transporting passengers was opposed, given that there would not be a pilot onboard to monitor the operation. |

| Factors and the Specificity | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Gender | - |

| 2. | Age | - |

| 3. | Previous experience | Owning a drone; Frequency of drone usage; Frequency of drone encounter |

| 4. | Knowledge levels | Knowledge scores out of 10 |

| 5. | Perceived benefit | I think this drone activity benefits society; Overall, the benefits and usefulness outweigh the risks of this drone activity (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). |

| 6. | Trust | I trust the drone pilot; I trust the drone technology; I trust the organisation overseeing/regulating/governing this activity (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). |

| 7. | Noise | In this situation, drone noise is an issue for me (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). |

| 8. | Risk perception | Mid-air collision (0–100); Ground impact risk (0–100); Privacy risk (0–100). |

| Variable | n | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 202 | 48.61 |

| Female | 192 | 51.14 |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 | 0.25 |

| Age | ||

| 20s | 79 | 20 |

| 30s | 96 | 24.3 |

| 40s | 64 | 16.2 |

| 50s | 47 | 11.9 |

| Over 60s | 109 | 27.6 |

| Yearly income | ||

| Under $30,000 | 21 | 7.85 |

| $30,001–$70,000 | 114 | 28.86 |

| $70,001–$100,000 | 65 | 16.46 |

| $100,001–$140,000 | 79 | 20 |

| $140,000–$200,000 | 64 | 16.2 |

| Over $200,000 | 25 | 6.33 |

| Prefer not to answer | 17 | 4.3 |

| Residential distance from Sydney Harbour | ||

| <2.5 km | 51 | 12.94 |

| 2.5–5 km | 18 | 4.57 |

| 5–7.5 km | 23 | 5.84 |

| 7.5–10 km | 18 | 4.57 |

| Beyond 10 km | 257 | 65.23 |

| Previous experience | ||

| Own a drone | 86 | 21.77 |

| Operated a drone | 141 | 35.57 |

| Encountered a drone | 285 | 72.15 |

| Beach/sea | 67 | 23.28 |

| From my residence | 52 | 18.25 |

| Local parks/fields | 51 | 18.11 |

| National parks/hiking trails | 18 | 6.32 |

| Office | 2 | 0.7 |

| Sporting events | 18 | 6.32 |

| Others | 10 | 3.51 |

| RPA Operation | Proportion of Acceptance | Safety Level Compared to Manned Aircraft | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, It Is Acceptable | No, It Is Too Risky | Riskier | Same Level | Safer | |

| Recreational Flying | 42.8% | 57.2% | 38.5% | 24.5% | 37.0% |

| Commercial Filming | 68.6% | 31.4% | 27% | 29.4% | 43.6% |

| Environmental Monitoring | 82.0% | 18.0% | 21.5% | 33.7% | 44.8% |

| X Variable | Recreational Flying | Commercial Filming | Environmental Monitoring | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | Standard Error | z-Test | p-Value | Odds Ratio | Standard Error | z-Test | p-Value | Odds Ratio | Standard Error | z-Test | p-Value | |

| Age | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Gender (male) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.03 | 0.75 | 1.93 | 0.053 |

| Previous experience (own) | 3.07 | 1.3 | 2.65 | 0.008 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Previous experience encounter | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Knowledge levels | 0.88 | 0.06 | −2.0 | 0.048 | 0.88 | 0.06 | −2.1 | 0.039 | - | - | - | - |

| Trust in pilot | 1.60 | 0.20 | 3.71 | 0.0 | 1.35 | 0.2 | 2.01 | 0.044 | 1.75 | 0.31 | 3.16 | 0.002 |

| Trust in RPA | 1.43 | 0.24 | 2.17 | 0.03 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Trust in organisation | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Benefits the society | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Benefits outweigh the risks | 1.35 | 0.20 | 2.0 | 0.042 | 1.44 | 0.24 | 2.16 | 0.031 | 1.49 | 0.30 | 1.99 | 0.047 |

| Mid-air collision risk | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ground impact risk | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.9 | 0.11 | −2.3 | 0.023 |

| Privacy risk | 0.97 | 0.01 | −3.5 | 0.001 | 0.96 | 0.01 | −4.8 | 0.0 | 0.96 | 0.01 | −3.3 | 0.001 |

| Noise | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| n = 395 LR Chi2(14) = 252.45 p-value = 0.0000 Pseudo-R2 = 0.4681 Log likelihood = −143.44 Area under the ROC curve = 0.92 | n = 395 LR Chi2(14) = 191.59 p-value = 0.0000 Pseudo-R2 = 0.3898 Log likelihood = −149.98 Area under the ROC curve = 0.88 | n = 395 LR Chi2(14) = 144.56 p-value = 0.0000 Pseudo-R2 = 0.3885 Log likelihood = −113.77 Area under the ROC curve = 0.91 | ||||||||||

| Question | TRUE | FALSE | Uncertain | Correct % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Apart from anyone helping you control or navigate your drone; you must fly your drone at least 30 m away from other people. | 59.24% | 7.6% | 33.16% | 59.24% |

| 2 | You can fly within 5.5 km of a controlled airport (e.g., Sydney Kingsford Smith airport) if your drone weighs more than 250 g. | 17.97% | 43.80% | 38.23% | 43.80% |

| 3 | You can only fly one drone at a time. | 52.91% | 9.62% | 37.47% | 52.91% |

| 4 | You can fly a drone in Sydney Harbour during the night if your drone has lights on it. | 18.99% | 36.96% | 44.05% | 36.96% |

| 5 | It is ok to fly your drone in foggy conditions. | 8.61% | 63.29% | 28.10% | 63.29% |

| 6 | You can fly your drone in a populous area (such as a crowded beach) if visibility and conditions are good. | 23.29% | 41.52% | 35.19% | 41.52% |

| 7 | If you intend to fly your drone for or at work (commercially), you must register your drone and obtain an operator accreditation (or remote pilot licence) to fly it. | 67.85% | 5.06% | 27.09% | 67.85% |

| 8 | CASA—the Civil Aviation Safety Authority—oversees drone safety and enforcement in Australia, including breach of privacy. | 60.00% | 5.32% | 34.68% | 60.00% |

| 9 | You can fly a drone in Sydney Harbour over waters as long as it is not over people. | 31.39% | 25.06% | 43.54% | 25.06% |

| 10 | You need to seek permission from CASA to fly a drone in Sydney Harbour for fun if the drone is over 250 g. | 24.30% | 36.20% | 39.50% | 24.30% |

| RPA Operations | Benefit Society | Benefits Outweigh the Risks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disagree (%) | Indifferent (%) | Agree (%) | Disagree (%) | Indifferent (%) | Agree (%) | |

| Recreational flying | 44.81 | 23.8 | 31.39 | 42.28 | 24.81 | 32.91 |

| Commercial filming | 22.28 | 32.15 | 45.57 | 17.97 | 29.37 | 52.66 |

| Environmental monitoring | 8.61 | 16.71 | 74.68 | 9.87 | 19.5 | 70.63 |

| RPA Operations | Trust Pilot | Trust RPA | Trust Organisation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do not trust (%) | Indifferent (%) | Trust (%) | Do not trust (%) | Indifferent (%) | Trust (%) | Do not trust (%) | Indifferent (%) | Trust (%) | |

| Recreational flying | 47.34 | 23.04 | 29.62 | 22.03 | 23.54 | 54.43 | 28.1 | 25.32 | 46.58 |

| Commercial filming | 18.48 | 20.25 | 61.27 | 12.41 | 19.49 | 68.1 | 18.23 | 18.48 | 63.29 |

| Environmental monitoring | 13.42 | 16.45 | 70.13 | 11.65 | 17.21 | 71.14 | 9.11 | 15.7 | 75.19 |

| Factor | Expected Result | Result | Types of Operation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Not applicable | Not significant | Nil |

| Gender | Men are more likely to accept RPA operations | Men are more likely to accept RPA operations | Environmental monitoring |

| Previous experience | Positive | Positive, specifically for those who own RPA | Recreational |

| Knowledge levels | Not applicable | Negative (greater knowledge, less acceptance) | Recreational flying; Commercial filming |

| Trust | Positive | Positive, specifically trust in the pilot | Recreational flying; Commercial filming; Environmental monitoring |

| Perceived benefits | Positive | Positive, specifically for the benefits that outweigh the risks | Recreational flying; Commercial filming; Environmental monitoring |

| Mid-air collision risk | Not applicable | Not significant | Nil |

| Ground impact risk | Not applicable | Negative | Environmental monitoring |

| Privacy risk | Negative | Negative | Recreational flying; Commercial filming; Environmental monitoring |

| Noise | Negative | Not significant | Nil |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Teo, Y.; Koo, T.T.R.; Kuok, R.U.K.; Dunn, M.; Sumaja, K.; D, V. Public Acceptance of Remotely Piloted Aircraft (RPA) Operations in Sydney Harbour. Drones 2026, 10, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010019

Teo Y, Koo TTR, Kuok RUK, Dunn M, Sumaja K, D V. Public Acceptance of Remotely Piloted Aircraft (RPA) Operations in Sydney Harbour. Drones. 2026; 10(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleTeo, Yan, Tay T. R. Koo, Rockie U Kei Kuok, Matthew Dunn, Kadek Sumaja, and Vinod D. 2026. "Public Acceptance of Remotely Piloted Aircraft (RPA) Operations in Sydney Harbour" Drones 10, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010019

APA StyleTeo, Y., Koo, T. T. R., Kuok, R. U. K., Dunn, M., Sumaja, K., & D, V. (2026). Public Acceptance of Remotely Piloted Aircraft (RPA) Operations in Sydney Harbour. Drones, 10(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010019