Adaptive Edge Intelligent Joint Optimization of UAV Computation Offloading and Trajectory Under Time-Varying Channels

Highlights

- The proposed Adaptive UAV Edge Intelligence Framework (AUEIF) effectively decouples the complexities of UAV trajectory, computation offloading, and dynamic air-to-ground communication, significantly improving adaptability and efficiency in multi-UAV MEC systems.

- A hierarchical reinforcement learning (HRL) approach optimizes large-scale action spaces by combining high-level trajectory control with fine-grained offloading and resource allocation, enabling scalable and adaptive decisionmaking across different time scales.

- The AUEIF demonstrates superior performance in task latency reduction and energy efficiency compared to conventional methods, with enhanced robustness under severe channel fading conditions, supporting reliable real-world UAV deployment.

- The integration of dynamic modeling, predictive LSTM-based channel forecasting, and hierarchical learning offers a modular and scalable blueprint for next-generation adaptive MEC systems capable of operating in highly dynamic environments.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We develop a dynamic system model that characterizes the spatio-temporal correlations among UAV mobility, task arrivals, and time-varying wireless channel conditions using a graph-based representation.

- We design a hierarchical reinforcement learning architecture in which a high-level actor–critic module plans coarse UAV trajectories, while a low-level deep Q-network performs fine-grained task offloading and resource allocation in real time.

- We introduce an adaptive channel prediction module based on LSTM to anticipate channel state evolution and enhance decision-making efficiency with respect to latency and energy consumption.

- We conduct extensive simulation studies showing that the proposed AUEIF framework outperforms conventional DRL-based and heuristic approaches in terms of latency, energy efficiency, and policy stability under dynamic channel environments.

2. Related Work

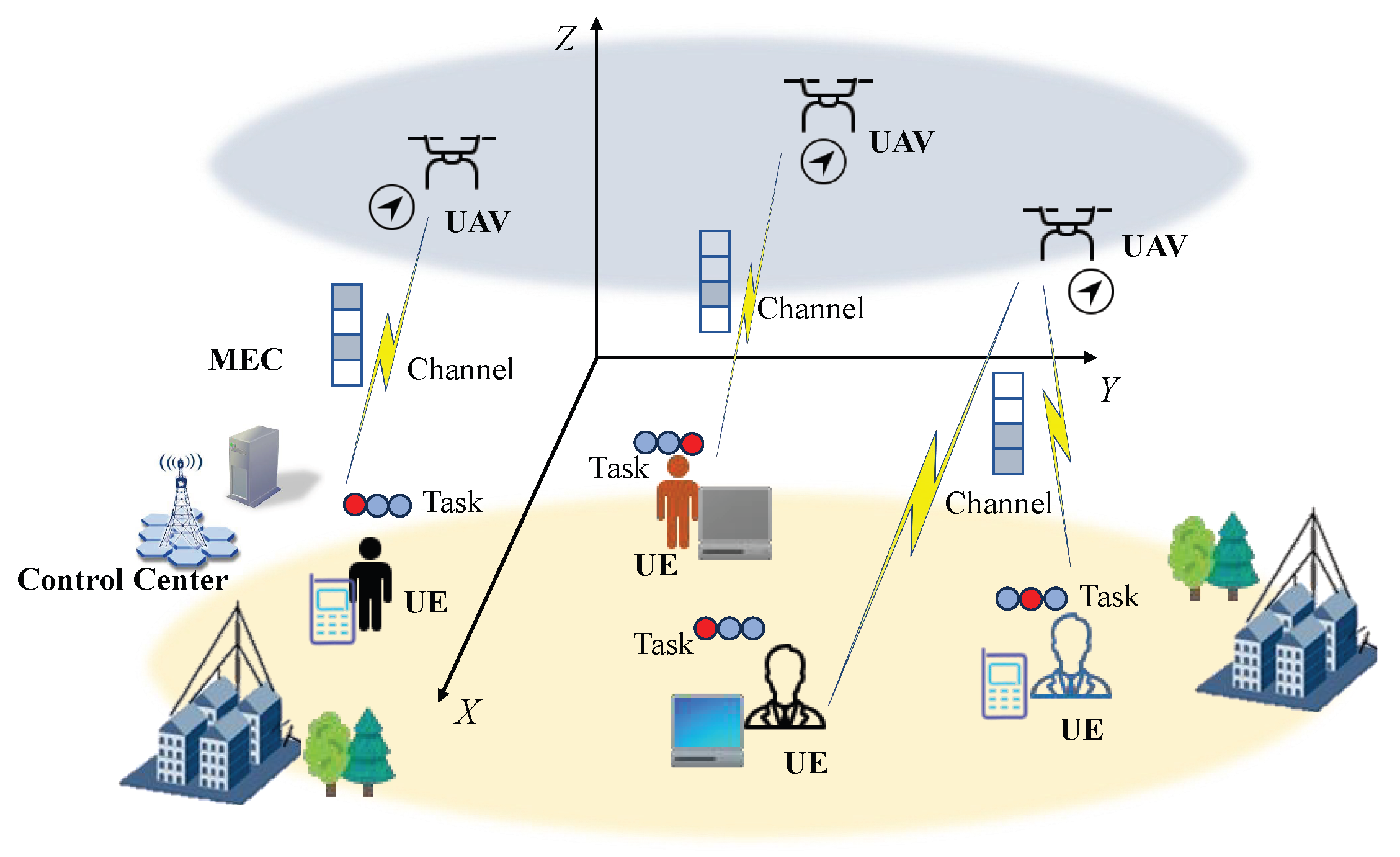

3. System Model

3.1. UAV Three-Dimensional Trajectory and Collision Avoidance

3.2. UAV–UE Communication Model

3.3. Computation Offloading Model

3.4. Weighted System Objective Function

3.5. Problem Formulation

4. Approach Design

4.1. Dynamic Graph Construction

4.2. LSTM-Based Channel Prediction

4.3. Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning Framework

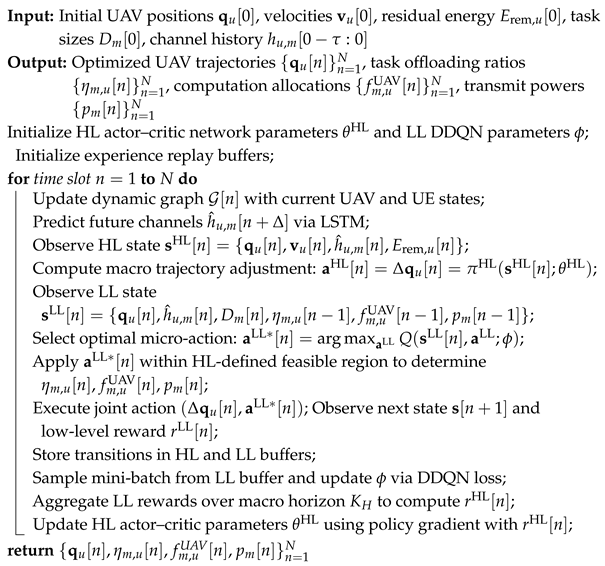

| Algorithm 1: Hierarchical UAV Trajectory and Computation Offloading via HRL |

|

5. Experiment Setting

5.1. System Parameters

5.2. Baseline Methods and Evaluation Metrics

- Random Offloading (RO): UAVs randomly decide task offloading ratios to edge servers and cloud, without trajectory optimization or queue awareness.

- Greedy Trajectory (GT): UAVs always move toward the UE with the largest task queue, without considering channel dynamics or offloading optimization.

- Equal Resource Allocation (ERA): Computation and communication resources are evenly distributed among all UEs and UAVs, without adaptive optimization.

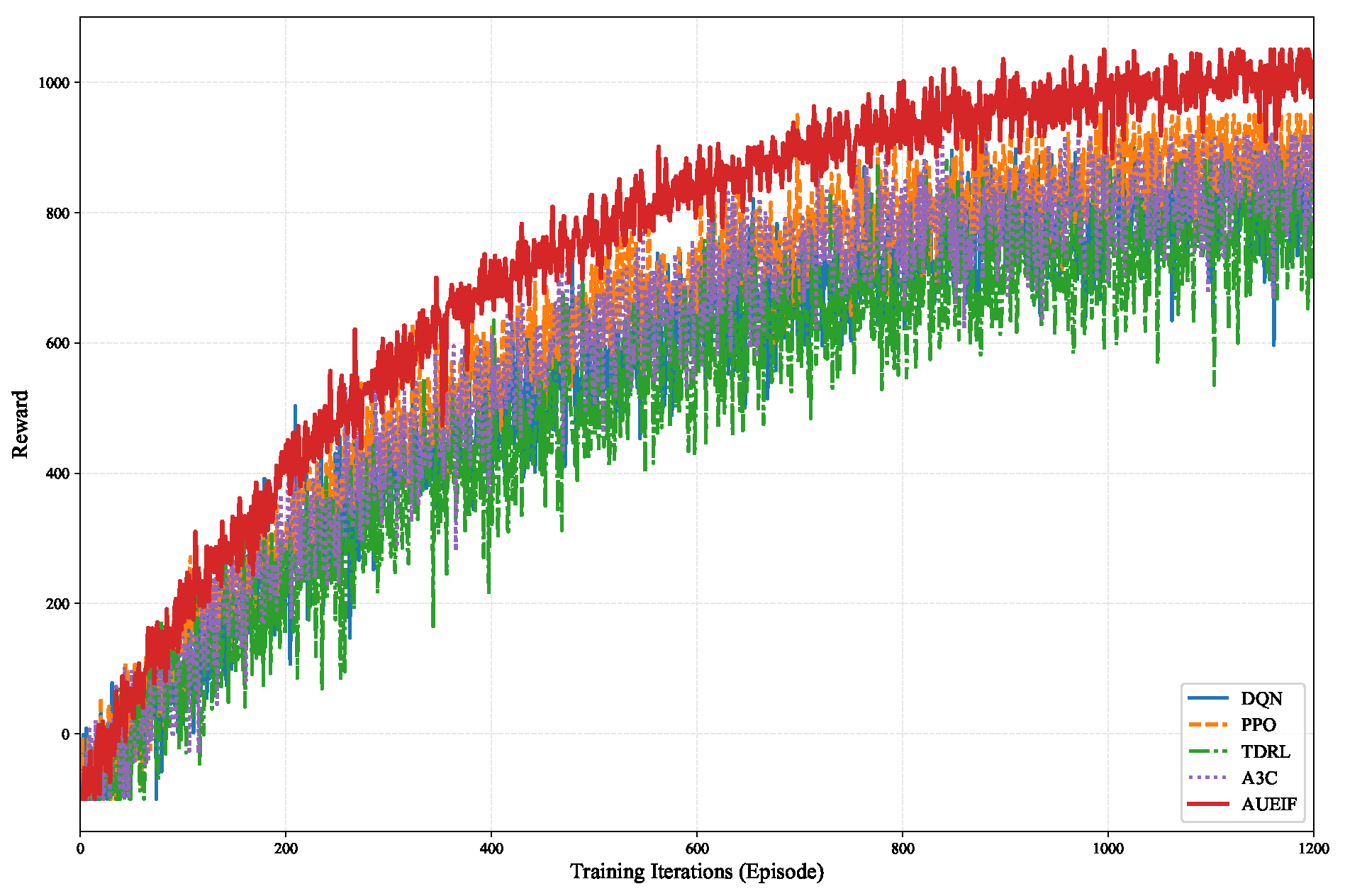

- Time-Driven DRL (TDRL): Deep reinforcement learning algorithm optimizing UAV trajectories, offloading decisions, and transmission power based on time-driven strategy, without task-driven reliability awareness or hybrid action representation.

- Alternating Optimization (AO): Joint optimization of partial offloading, UAV trajectory, user scheduling, edge-cloud computation, and resource allocation using alternating optimization and SCA techniques, without online or task-driven adaptation.

- PLOT without Lyapunov Perturbation (PLOT-NS): Online UAV-MEC algorithm using standard Lyapunov optimization without perturbed control, which may suffer from coupling effects and suboptimal queue stability.

6. Experiment Result

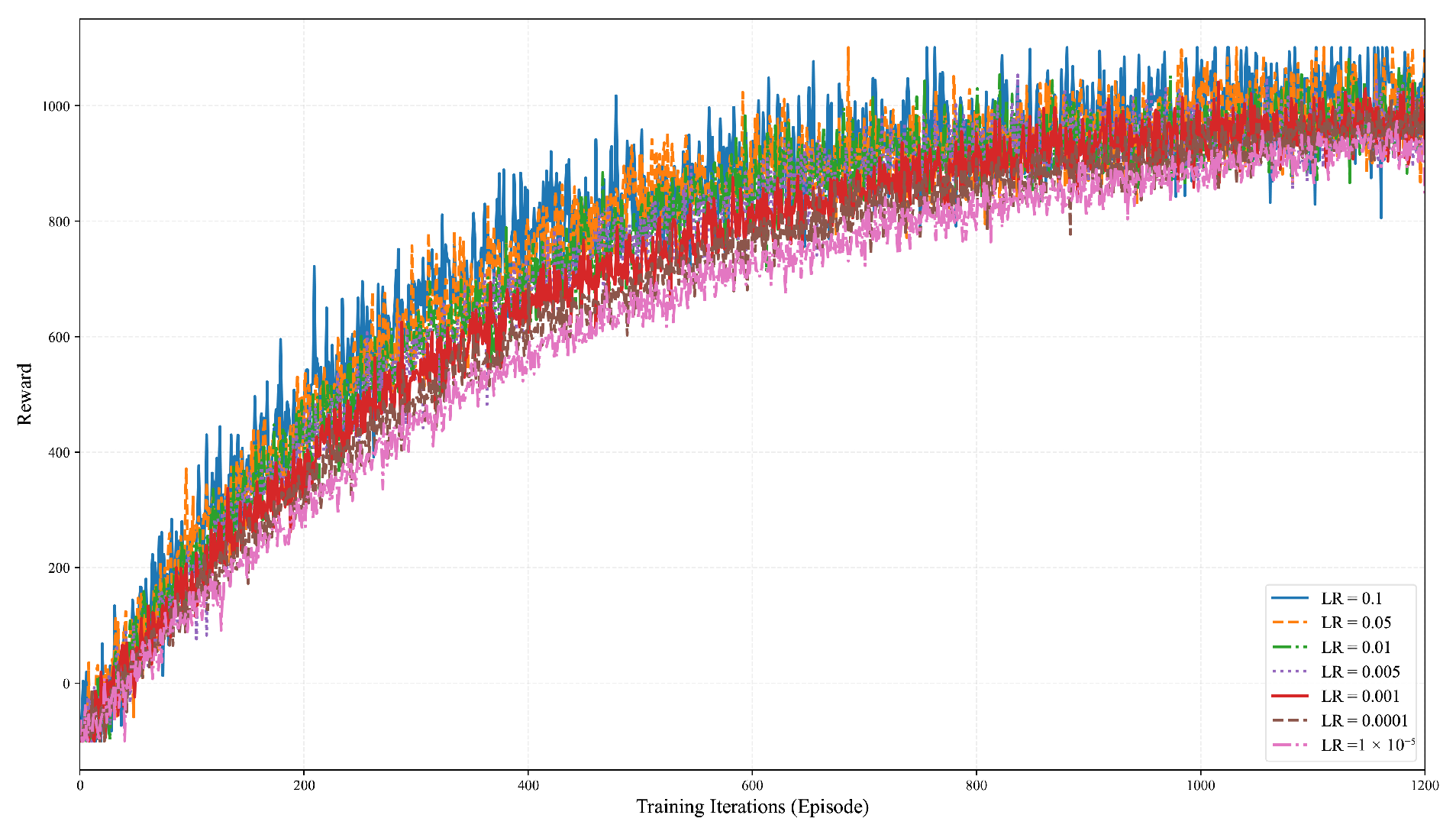

6.1. Convergence Performance Analysis

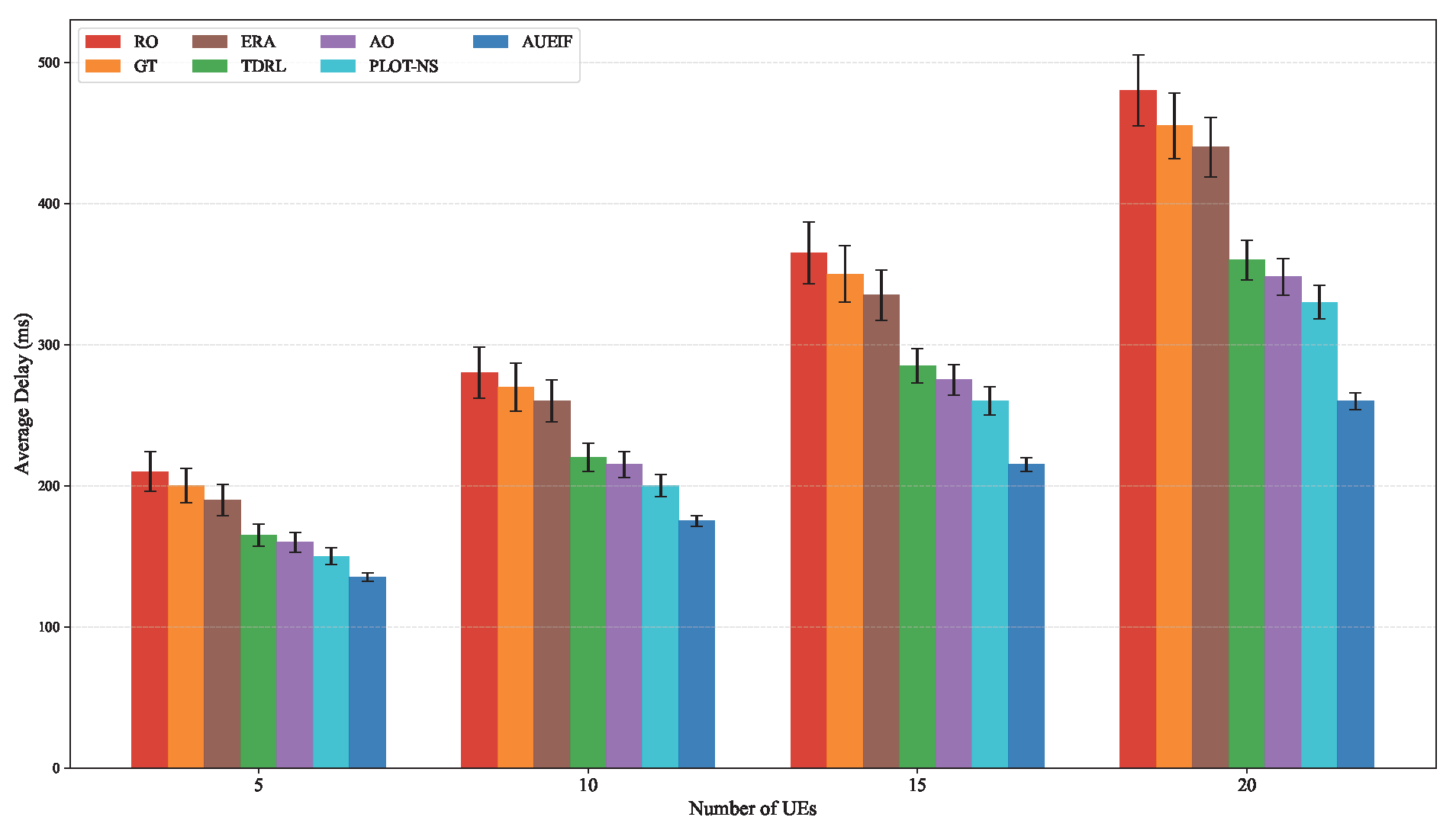

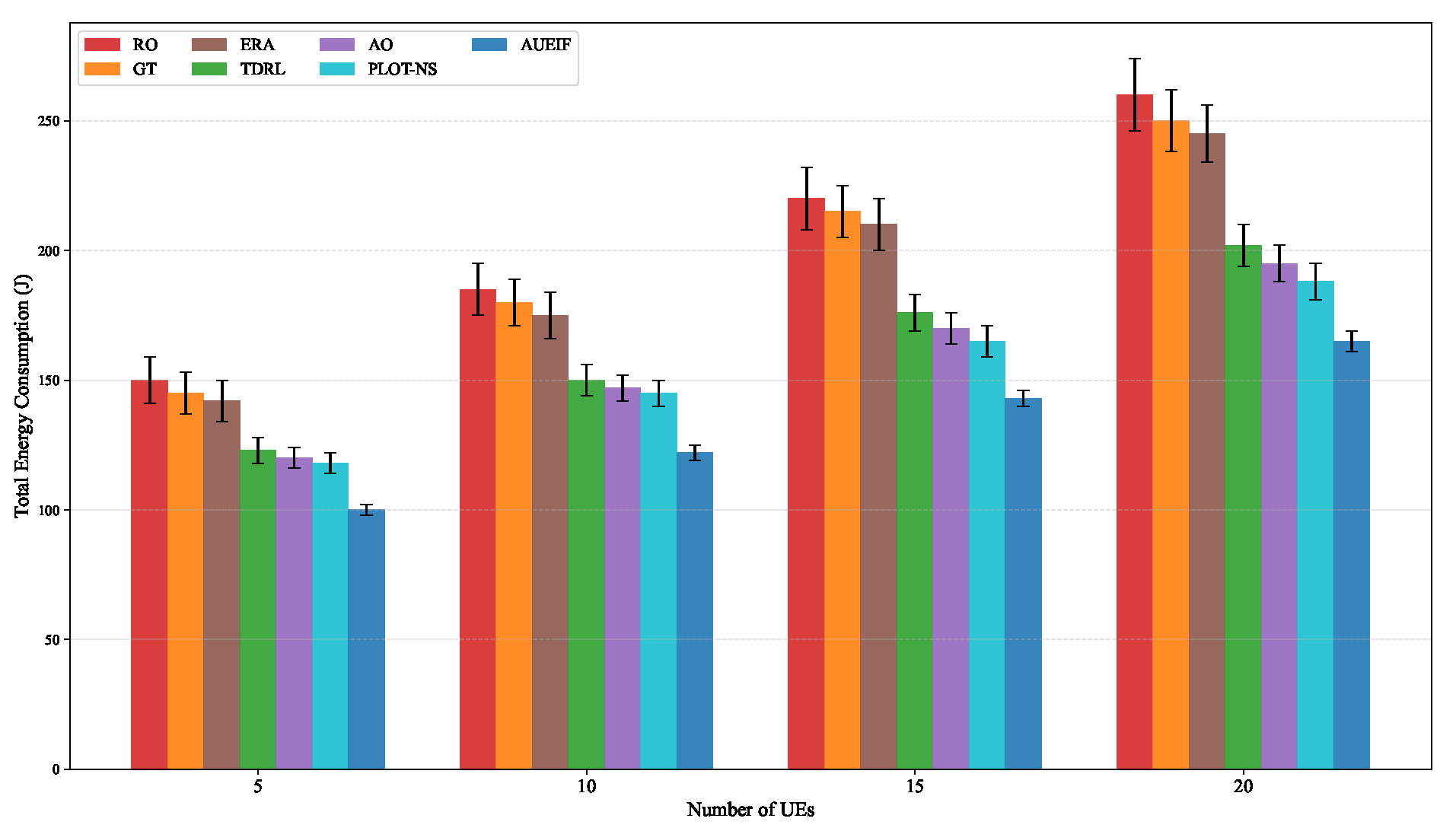

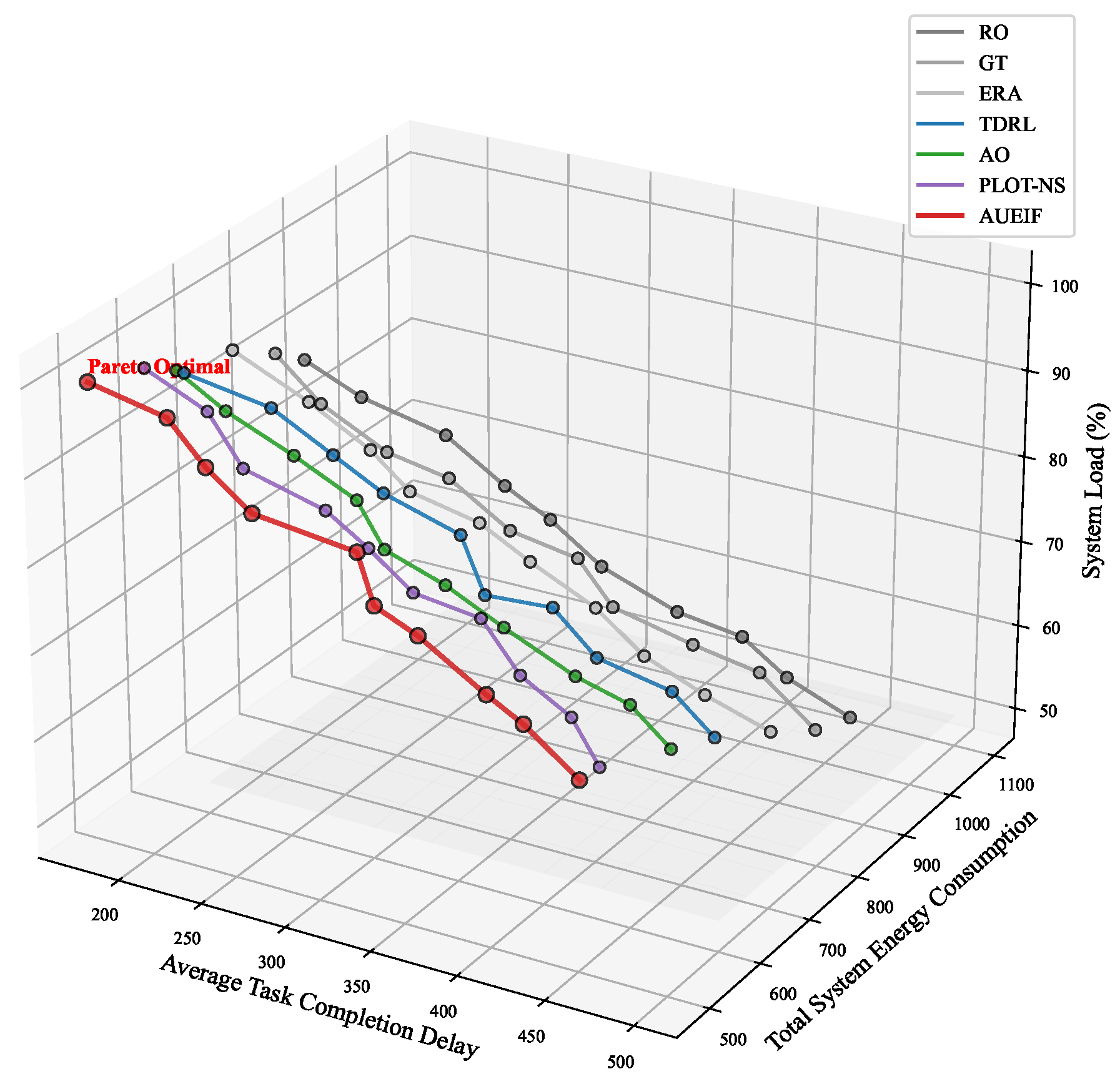

6.2. Differential Performance Analysis Under Varying UE Density

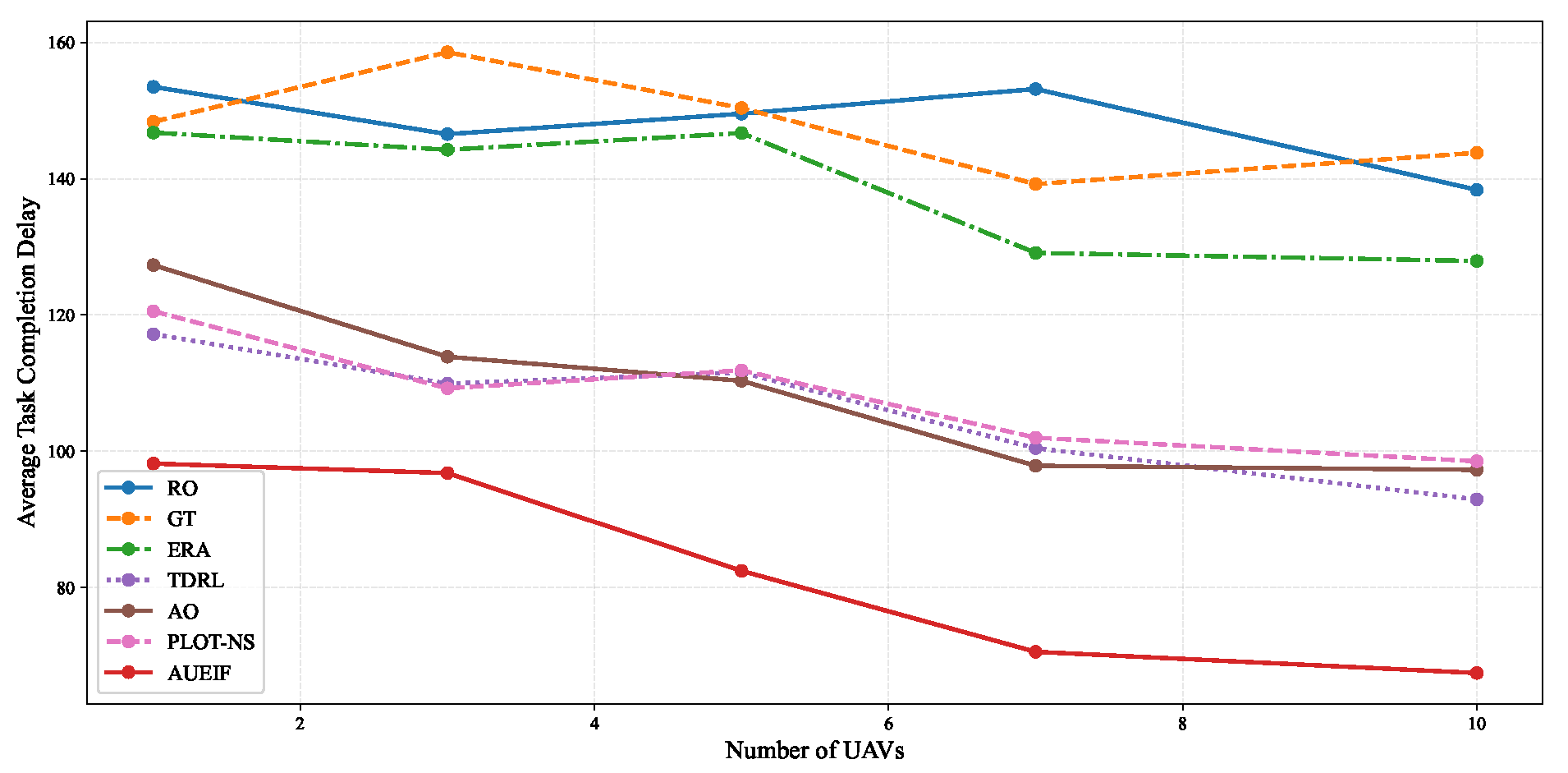

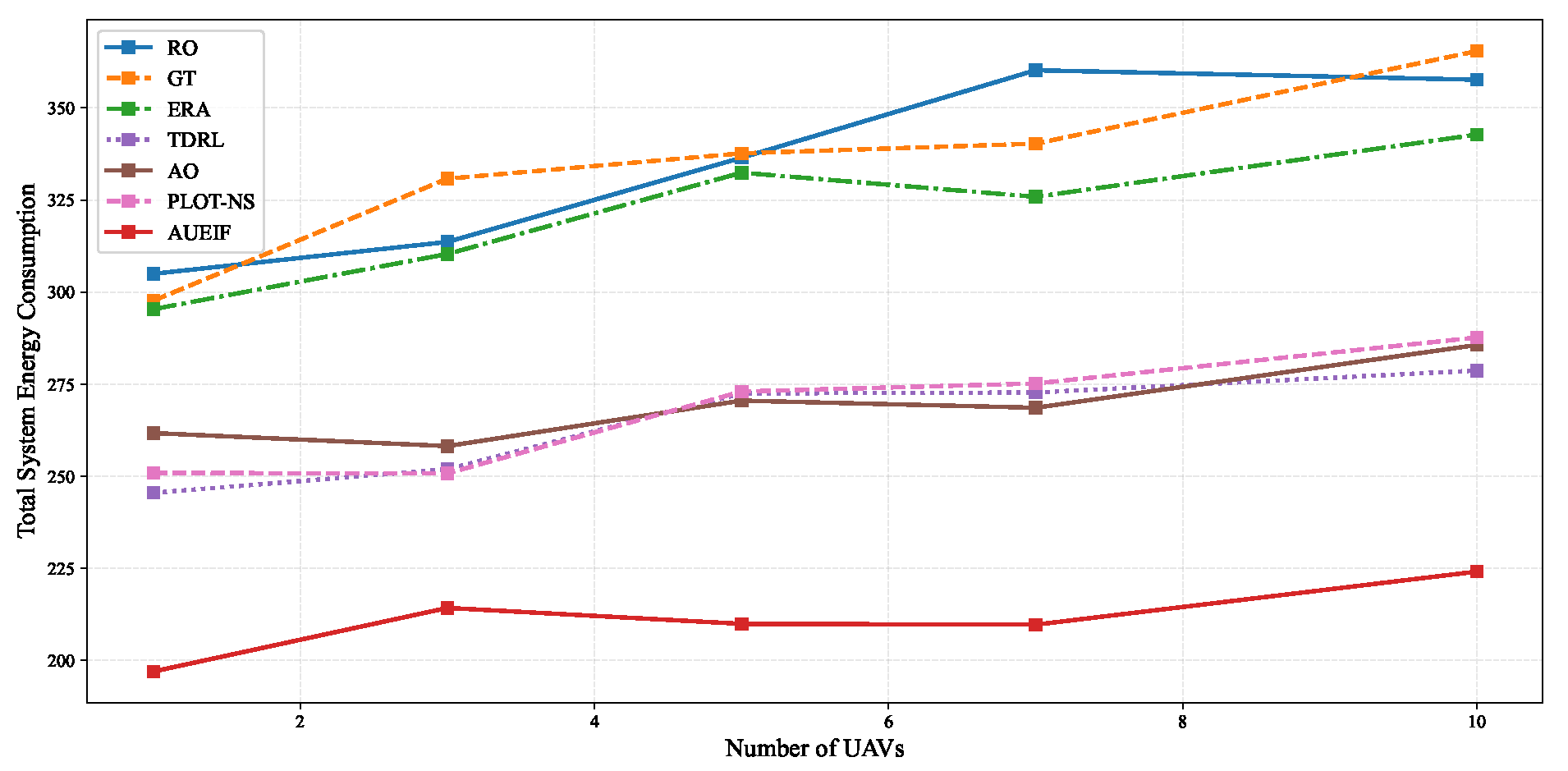

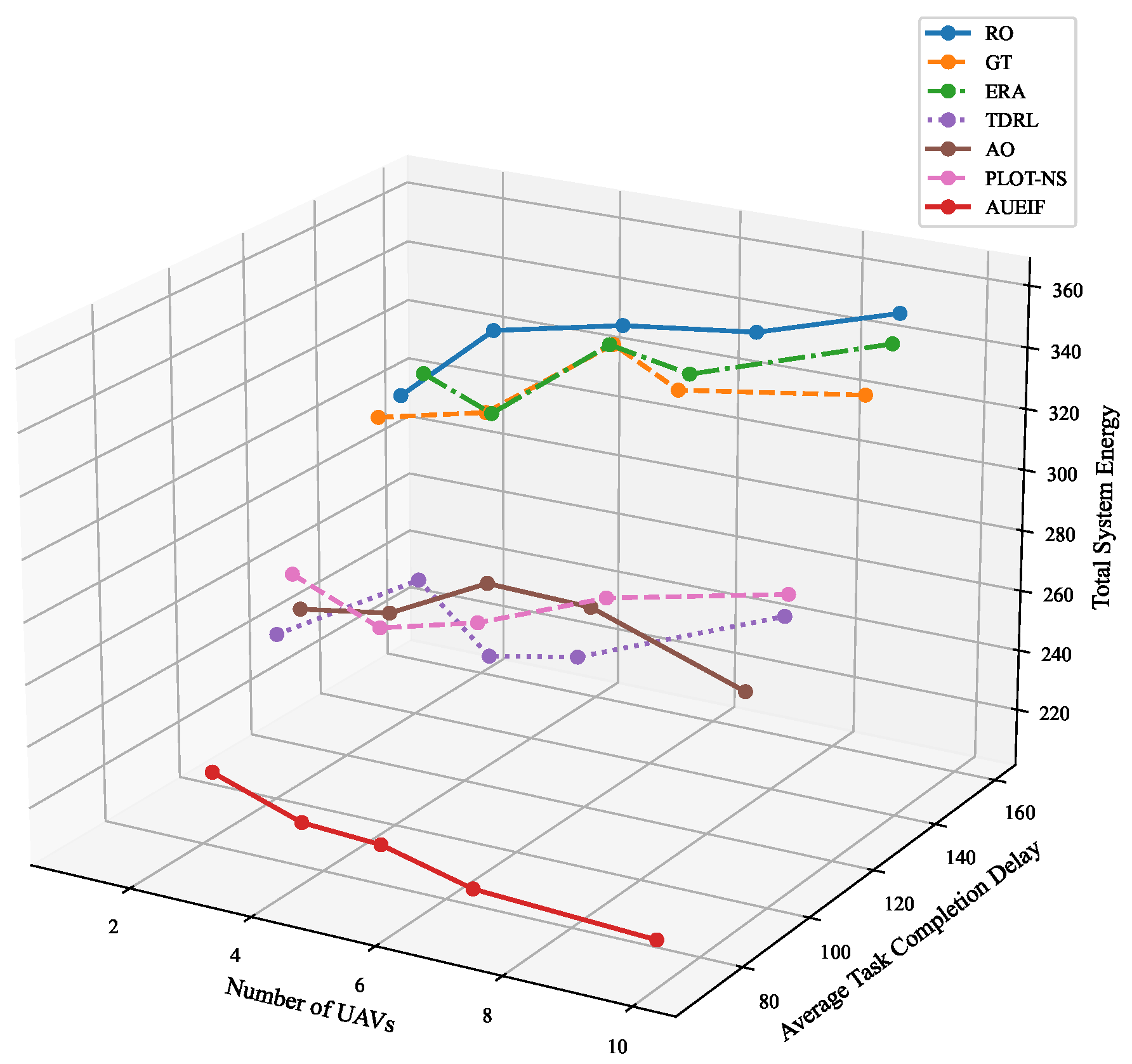

6.3. Differential Performance Analysis Under Varying UAV Density

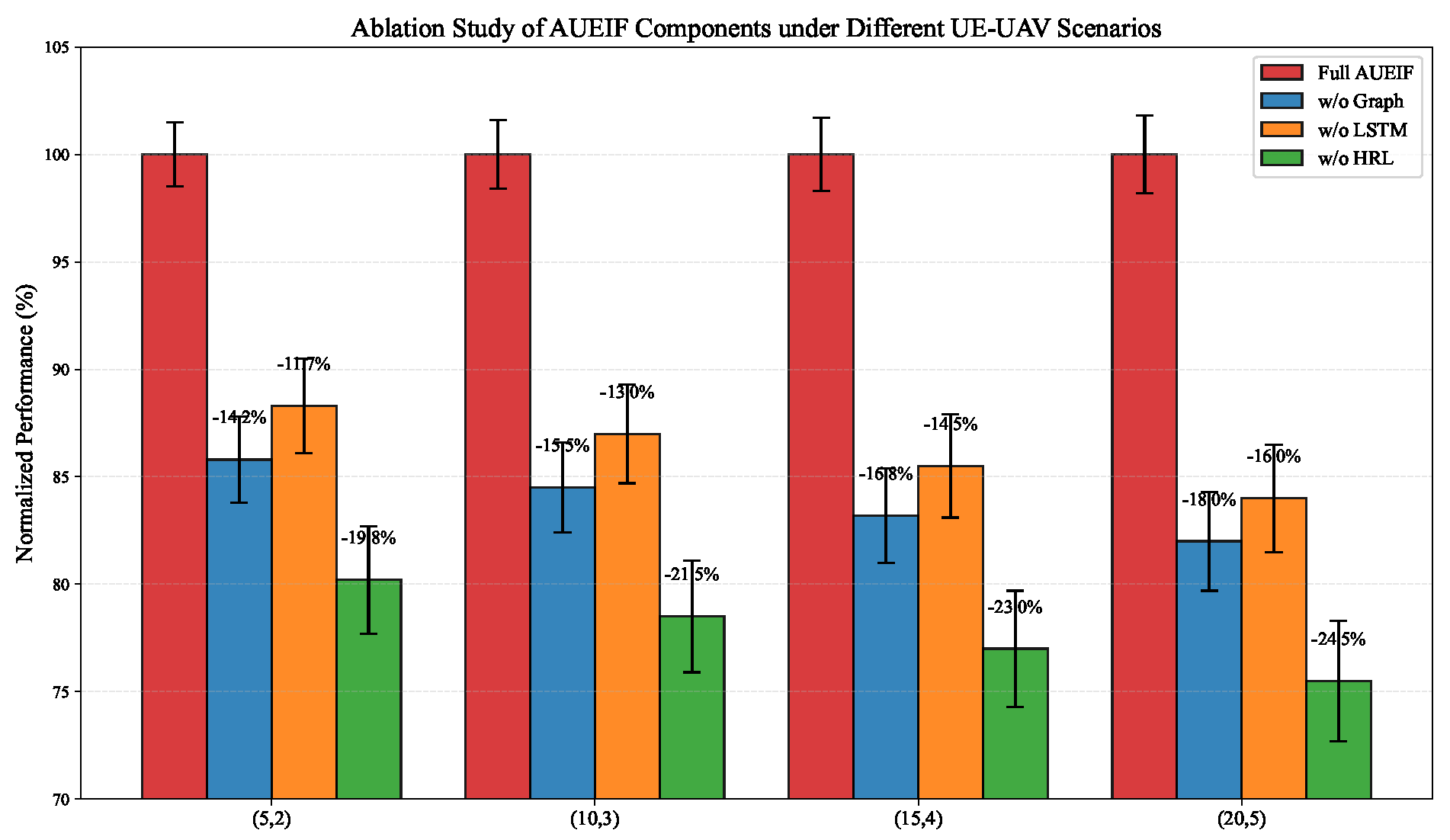

6.4. Ablation Experiment Analysis

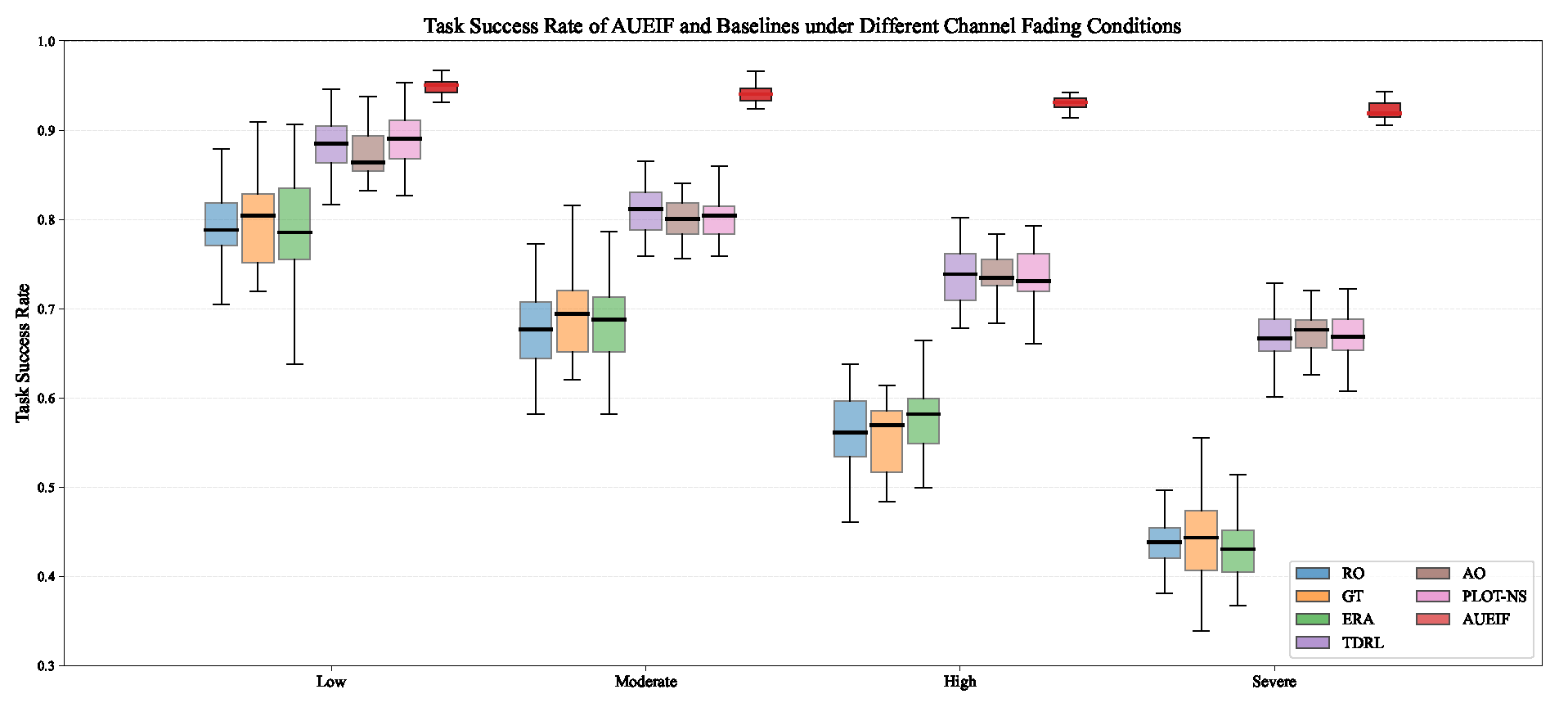

6.5. Robustness of AUEIF Under Varying Channel Fading Conditions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, F.; Luo, J.; Qiao, Y.; Li, Y. Joint UAV Deployment and Task Offloading Scheme for Multi-UAV-Assisted Edge Computing. Drones 2023, 7, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Wei, D.; Li, K.; Liu, W. UAV-Centric Privacy-Preserving Computation Offloading in Multi-UAV Mobile Edge Computing. Drones 2025, 9, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Guo, Y.; Wang, H.; Gu, J.; Liu, J.; Ding, G. Cognitive Jamming-aided UAV Multi-user Covert Communication. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2025; early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Gui, X.; Ren, D.; Li, D. Energy–Latency Tradeoff for Computation Offloading in UAV-Assisted Multiaccess Edge Computing System. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 6709–6719. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Feng, J.; Liu, L.; Pei, Q. Optimizing Resource Utilization in Consumer Electronics Networks Through an Enhanced Grey Wolf Optimization Algorithm With UAV Collaboration. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2025, 71, 7376–7386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Bi, S.; Zhang, Y.-J.A. Dynamic Offloading and Trajectory Control for UAV-Enabled Mobile Edge Computing System With Energy Harvesting Devices. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2022, 21, 10515–10528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Xu, C.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.; Yang, S.; Muntean, G.-M. Reliability-Aware Optimization of Task Offloading for UAV-Assisted Edge Computing. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2025, 74, 3832–3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.D.; Le, L.B.; Girard, A. Integrated Computation Offloading, UAV Trajectory Control, Edge-Cloud and Radio Resource Allocation in SAGIN. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 2024, 12, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Luo, H.; Chen, X.; Shen, H.; Guo, L. Minimizing Response Delay in UAV-Assisted Mobile Edge Computing by Joint UAV Deployment and Computation Offloading. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 2024, 12, 1372–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.; Yang, D.; Xiao, L.; Tao, M. UAV-Assisted MEC Networks with Aerial and Ground Cooperation. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2021, 20, 7712–7727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Ye, Z.; Pei, Y.; Liang, Y.-C.; Niyato, D. Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning for Task Offloading in UAV-Assisted Mobile Edge Computing. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2022, 21, 6949–6960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Pi, D.; Yang, S.; Xu, Y.; Chen, J.; Mohamed, A.W. HNIO: A Hybrid Nature-Inspired Optimization Algorithm for Energy Minimization in UAV-Assisted Mobile Edge Computing. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2022, 19, 3264–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bakhrani, A.A.; Li, M.; Obaidat, M.S.; Amran, G.A. MOALF-UAV-MEC: Adaptive Multiobjective Optimization for UAV-Assisted Mobile Edge Computing in Dynamic IoT Environments. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 20736–20756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Xing, H.; Wang, X.; Luo, S.; Dai, P.; Xiao, Z.; Zhao, B. Evolutionary Multi-Objective Reinforcement Learning Based Trajectory Control and Task Offloading in UAV-Assisted Mobile Edge Computing. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2023, 22, 7387–7405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Mao, H.; Deng, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, H.; Wei, J. Real-Time Radio Map Construction and Distribution for UAV-Assisted Mobile Edge Computing Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 21337–21346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Pi, D.; Yang, S.; Xu, Y.; Wang, B.; Qin, S.; Wang, Y. A Dynamic Optimization Framework for Computation Rate Maximization in UAV-Assisted Mobile Edge Computing. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 11395–11409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiao, L.; Tan, H.; Zhang, R.; Wu, L. User Preference Oriented Service Caching and Task Offloading for UAV-Assisted MEC Networks. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2025, 18, 1097–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Xu, Y.; Loo, J.; Yang, D.; Xiao, L. Joint Computation and Communication Design for UAV-Assisted Mobile Edge Computing in IoT. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 5505–5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wan, Y.; Zhou, F.; Wu, Q.; Hu, R.Q. Resource Allocation and Trajectory Design for MISO UAV-Assisted MEC Networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 4933–4948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, M.; Chen, J.; Yang, L.; Lv, L.; Jiang, H.; Al-Dhahir, N. UAV-Assisted Mobile Edge Computing: Optimal Design of UAV Altitude and Task Offloading. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 23, 13633–13647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Wu, Q.; Kang, J.; Niyato, D.; Leung, V.C. Multi-Objective Optimization for Multi-UAV-Assisted Mobile Edge Computing. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2024, 23, 14803–14820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.; Son, S.; Kim, M.; Lee, J.; Das, A.K.; Park, Y. A Secure Self-Certified Broadcast Authentication Protocol for Intelligent Transportation Systems in UAV-Assisted Mobile Edge Computing Environments. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 19004–19017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yang, D.; Liu, Y.; Tao, M. Joint Resource and Trajectory Optimization for Security in UAV-Assisted MEC Systems. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2021, 69, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Yang, H.; Xiao, L.; Su, W.; Chen, Y.; Xiong, Z. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Resource Management for UAV-Assisted Mobile Edge Computing Against Jamming. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2024, 23, 13358–13374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Zhou, Y.; Tian, D.; Zhou, J.; Sheng, Z.; Shen, X. Weighted Energy-Efficiency Maximization for a UAV-Assisted Multiplatoon Mobile-Edge Computing System. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 18208–18220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, Z.; Guo, K.; Zhang, R.; Quek, T.Q.S. Against Mobile Collusive Eavesdroppers: Cooperative Secure Transmission and Computation in UAV-Assisted MEC Networks. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2025, 24, 5280–5297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulos, P.A.; Fragkos, G.; Tsiropoulou, E.E.; Papavassiliou, S. Data Offloading in UAV-Assisted Multi-Access Edge Computing Systems Under Resource Uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2023, 22, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Tian, D.; Sheng, Z.; Duan, X.; Qu, G.; Leung, V.C. Joint Communication and Computation Resource Scheduling of a UAV-Assisted Mobile Edge Computing System for Platooning Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 8435–8450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Huang, H.; Xiao, F. Bi-Objective Ant Colony Optimization for Trajectory Planning and Task Offloading in UAV-Assisted MEC Systems. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2024, 23, 12360–12377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Sun, G.; Wu, Q.; He, L.; Liang, S.; Pan, H. TJCCT: A Two-Timescale Approach for UAV-Assisted Mobile Edge Computing. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2025, 24, 3130–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Hwang, K.; Wu, D.; Hao, Y.; Chen, M. Drone Swarm Path Planning for Mobile Edge Computing in Industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2023, 19, 6836–6848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liang, X.; Liu, J.; He, X.; Xie, L.; Qu, L.; Feng, G. Optimizing Mobile-Edge Computing for Virtual Reality Rendering via UAVs: A Multiagent Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 35756–35772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yang, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, Y.; Huang, J. Task Offloading and Resource Pricing Based on Game Theory in UAV-Assisted Edge Computing. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2025, 18, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Li, B.; Liu, L.; Fei, Z.; Niyato, D. Trajectory Design and Resource Allocation for Multi-UAV-Assisted Sensing, Communication, and Edge Computing Integration. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2025, 73, 2847–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Description | Symbol | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| U | Number of UAVs | M | Number of UEs |

| T | Total task period (s) | N | Number of time slots |

| Duration of each slot (s) | UAV u 3D position at slot n | ||

| UAV altitude (m) | UAV horizontal coordinates (m) | ||

| Obstacle k center (m) | Obstacle radius (m) | ||

| Min distance to obstacle (m) | Min inter-UAV distance (m) | ||

| UAV velocity (m/s) | Max UAV speed (m/s) | ||

| UAV heading angle (rad) | Max heading angle (rad) | ||

| Flying duration (s) | Hovering duration (s) | ||

| UEs served by UAV u | Offloading fraction of UE m | ||

| Task data size (bits) | Transmission rate (bits/s) | ||

| UAV energy (J) | Flying energy (J) | ||

| Hovering energy (J) | UAV mass (kg) | ||

| Hovering power (W) | UE position (m) | ||

| Channel gain | Reference channel gain | ||

| Path loss exponent | Small-scale fading | ||

| Bandwidth (Hz) | UE transmit power (W) | ||

| Noise power (W) | Number of subchannels | ||

| UAVs serving UE m | UE CPU frequency | ||

| CPU cycles per bit | UE computation energy coefficient | ||

| UAV computation allocation | UAV energy coefficient | ||

| Total UAV CPU capacity | UE local computation latency | ||

| Offloaded latency | UE local computation energy | ||

| Offloading energy | Total system latency | ||

| Total system energy | Weight for UAV energy | ||

| F | Weighted objective | Latency/energy weights | |

| Initial latency weight | System workload utilization | ||

| Remaining UAV energy | Max UAV energy capacity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xie, J.; Xie, D. Adaptive Edge Intelligent Joint Optimization of UAV Computation Offloading and Trajectory Under Time-Varying Channels. Drones 2026, 10, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010021

Xie J, Xie D. Adaptive Edge Intelligent Joint Optimization of UAV Computation Offloading and Trajectory Under Time-Varying Channels. Drones. 2026; 10(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Jinwei, and Dimin Xie. 2026. "Adaptive Edge Intelligent Joint Optimization of UAV Computation Offloading and Trajectory Under Time-Varying Channels" Drones 10, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010021

APA StyleXie, J., & Xie, D. (2026). Adaptive Edge Intelligent Joint Optimization of UAV Computation Offloading and Trajectory Under Time-Varying Channels. Drones, 10(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010021