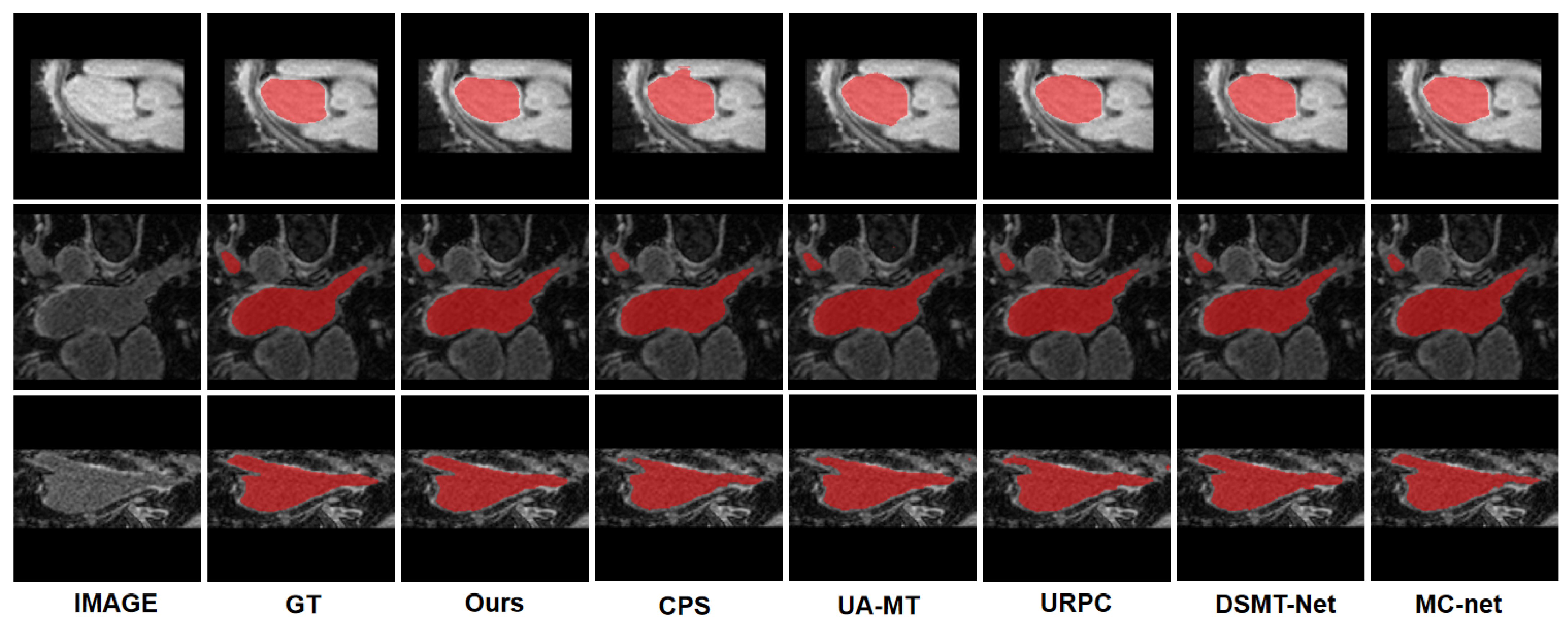

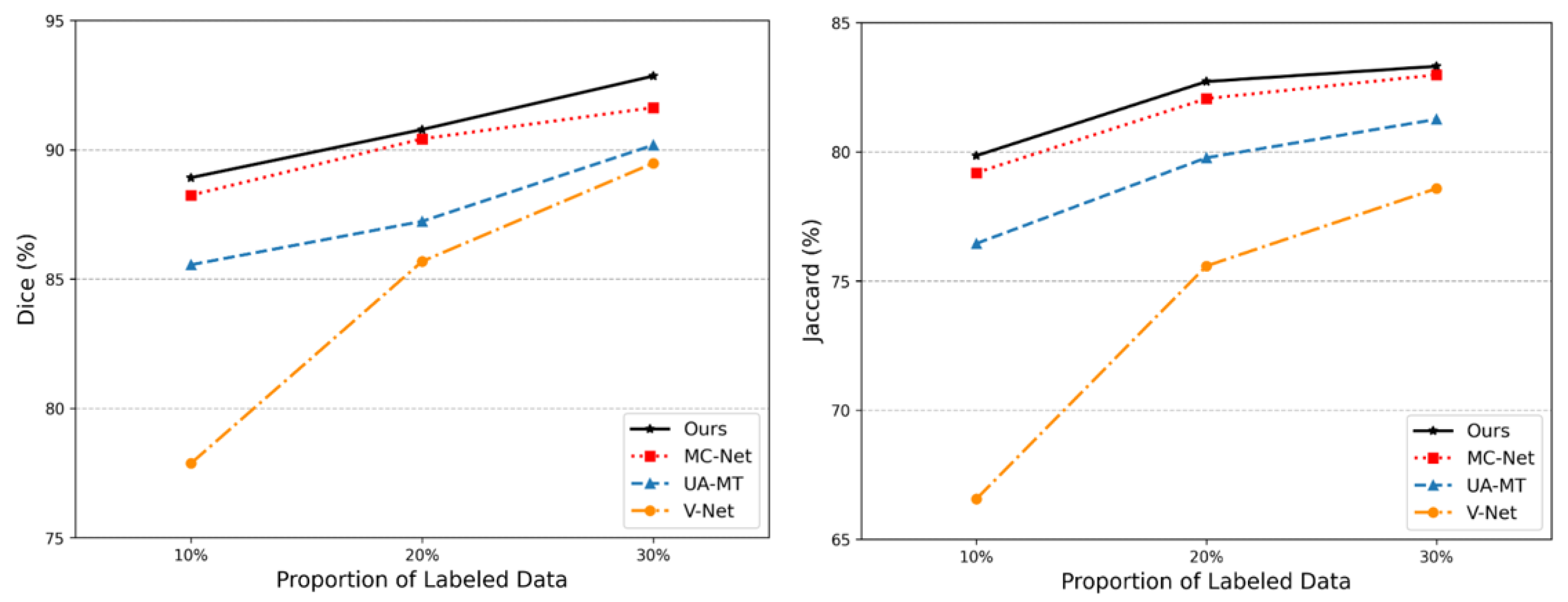

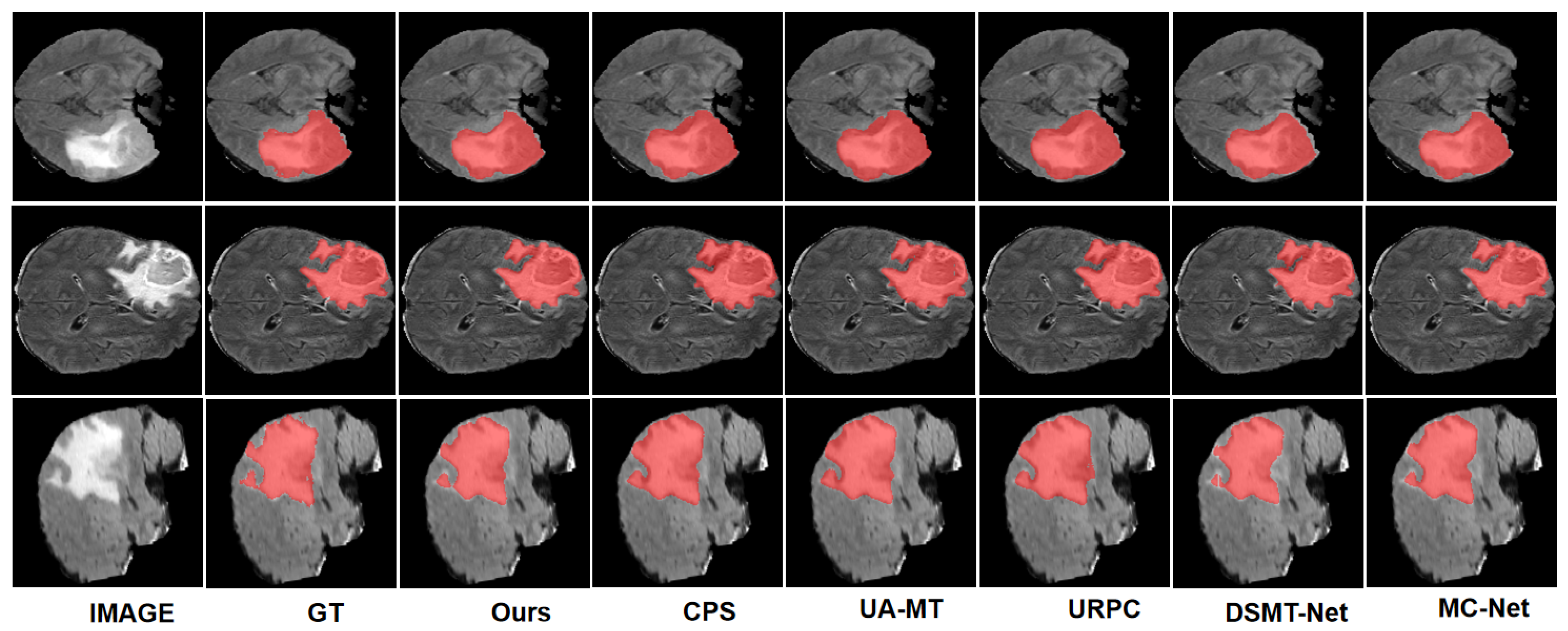

Our framework extends the mainstream Mean Teacher (MT) architecture by integrating hierarchical contrastive learning for the dual-student framework and an independence-inspired model update strategy. These components are complemented by uncertainty-guided dynamic data augmentation and fractal-dimension-weighted consistency regularization. Collectively, they aim to comprehensively enhance the robustness, generalization capability, and feature discriminative power of semi-supervised learning across three dimensions: model updates, data perturbations, and feature learning.

3.1. Independence-Aware Exponential Moving Average

The traditional Mean Teacher (MT) framework relies solely on the prediction consistency between the student network and its teacher network updated via exponential moving average (EMA). This approach is susceptible to model confirmation bias when handling unlabeled data, with the dependency between networks increasing as training iterations progress, leading to cumulative prediction errors. To address this challenge, we introduce an auxiliary student model to provide multi-perspective segmentation predictions. Furthermore, we propose an independence-aware exponential moving average (I-EMA) update strategy based on a linear-independence metric between networks for aggregating and updating teacher model parameters within the dual-student framework.

Intuitively, if one of the two student models exhibits a higher degree of independence from the teacher model in the feature space, it indicates that this student captures complementary representations that are absent in the teacher. Consequently, the teacher should preferentially absorb knowledge from this student to enhance the overall representational diversity and reduce the risk of model collapse. The proposed I-EMA mechanism incorporates such independence information into the exponential moving average update, where a linear-independence-based proxy guides the teacher’s parameter aggregation in a more informed and directional manner.

In the semi-supervised learning (SSL) paradigm for medical image segmentation, the training dataset is inherently imbalanced. For the current task, we construct the dataset to include

N labeled samples and a substantially larger set of

M unlabeled samples, satisfying

. The training data fed into the network are formally defined as the labeled data

and the unlabeled data

. Each input medical volume

x is represented as a three-dimensional volume with spatial dimensions

, and the corresponding ground-truth annotation

y is a binary segmentation mask, denoted as

. Our method employs two distinct student segmentation networks, parameterized by

and

, which are denoted as

and

, respectively. To enhance robustness and enable contrastive representation learning, we apply different data augmentation strategies to the input samples. Specifically, for the student network

, we generate a strongly augmented view using the transformation

; for the student network

, we construct a weakly augmented view using

. The segmentation outputs of the two student networks are denoted as

and

, where the subscripts

l and

u indicate the predictions corresponding to labeled and unlabeled inputs, respectively. In particular, the predictions on the unlabeled data are defined as follows, where the image fed to the strong branch is first subjected to weak augmentations such as flipping and cropping, followed by additional strong augmentation perturbations:

where the functions

and

denote the two student models subjected to strong and weak perturbations, respectively. Together, they collaboratively capture the essential latent features of the volumetric input data.

In teacher–student frameworks, the exponential moving average (EMA) is widely used to improve the stability and generalization ability of the teacher model. Its core idea is to update the teacher parameters by exponentially smoothing the parameters of the student model, which can be expressed as

where

is the smoothing coefficient, and

and

denote the parameters of the teacher and student models at iteration

t, respectively. This strategy effectively smooths the high-frequency noise during student training, allowing the teacher model to provide more stable pseudo-labels in semi-supervised or self-supervised learning.

However, the conventional EMA only performs temporal smoothing without considering the structural independence between networks in the representation space. Previous studies have shown that the main limitation of self-training and Mean Teacher frameworks lies in the strong dependency between the auxiliary and primary networks [

42]. When the representations of two networks become overly similar, the teacher updates tend to be redundant, reducing the diversity of feature representations and constraining the model’s generalization ability.

To alleviate this problem, we introduce the network independence metric proposed in CauSSL [

25] into our dual-student framework, which serves as a computable proxy for the algorithmic independence metric based on Kolmogorov complexity [

43]. This metric follows the principle of independent causal mechanisms (ICM) [

44] and is implemented according to the minimum description length principle [

45]. The detailed implementation will be presented in the following section.

We first map the learned weights of the neural network onto quantifiable mathematical objects. While the 3D convolution operation involves spatial sliding and filtering, its essence, from an algebraic perspective, is a high-dimensional inner product between the input feature patches and the convolutional kernel weights. We construct a pattern basis vector for this mapping; for a 3D convolutional layer, a kernel’s weight dimension is

. We flatten this multi-dimensional weight block into a

dimensional vector

v. In linear algebra,

v serves as a basis vector, representing the specific feature template learned by the network for that output channel. The entire convolutional layer comprises

independent kernels. The detailed procedure is shown in

Figure 3. By stacking these

basis vectors along the row dimension, we obtain a convolutional layer weight matrix

. Each row

of this matrix is a

d-dimensional basis vector for feature detection.

By converting the network weights into the matrix

, we transform the problem of network representational redundancy and independence into an analysis of matrix properties. According to the minimum description length (MDL) principle, if two networks

A and

B are algorithmically independent, the total length required to describe them equals the sum of their separate description lengths. In linear algebra, this is expressed by the matrix rank additivity property:

Specifically, we define the single-layer dependence

using the following formula:

where

is the

j-th basis vector in the student network

weight matrix

, and

is the optimal linear combination approximation vector of

in the teacher network

’s feature space, calculated as

.

To find the most suitable set of linear coefficient matrices , we first fix the parameters of the student network and the teacher network in the current iteration t. Our objective is to find the that maximizes the dependence between the two networks, which is equivalent to finding the that minimizes the linear approximation error. Once this optimal is obtained, we fix it and then proceed to adjust the network parameters by maximizing the principle of independence.

Based on the single-layer dependence, we define the independence proxy

of the student network

relative to the teacher network

as

where

and

are the weight parameters in matrix form within the networks, and

is the number of convolutional layers; only convolutional layers are considered here.

The I-EMA strategy guides the parameter update of the teacher network

in every iteration

t by first calculating the independence weights

and

. We first compute the independence proxy values for the two students

and

relative to the current teacher

:

Subsequently,

and

are normalized using the Softmax function to generate the dynamic weights

and

that guide the aggregation. The Softmax operation ensures that the network with higher independence receives a larger weight:

where

is a temperature parameter used to adjust the strength of the independence difference’s impact on the final weights. We set it 1.1. We directly integrate the independence-weighted aggregation result into the teacher model’s traditional EMA update equation. This parameter update strategy dynamically weights and aggregates knowledge from the students, ensuring that the teacher model prioritizes absorbing knowledge with complementary representations. The final unified I-EMA parameter update equation is

where

is the teacher’s parameters at the next time step,

is the current teacher’s parameters, and

is the traditional EMA smoothing factor. This equation merges the current independence guidance

and

with the historical knowledge

.

This parameter update strategy dynamically aggregates knowledge from the students, ensuring that the teacher model prioritizes absorbing knowledge with complementary representations.

3.2. Hierarchical Contrastive Learning for Dual-Student Framework

In our dual-student framework, the two student networks are fed with differently augmented inputs, representing weak and strong perturbations, respectively. Based on the smoothness assumption, the predictions from networks under different levels of perturbation should remain consistent both at the data level and in the feature space. Therefore, we further introduce contrastive learning at the feature level to enhance the representational consistency and discriminability of the two student networks across different feature subspaces. Specifically, we constrain the feature representations from three complementary perspectives: global consistency, high-confidence alignment, and low-confidence separation. For each student network

and

, we add a projection head

and

after their respective decoder last layers. Let

and

be the final output labels of the two networks. We first enforce global prediction consistency by minimizing the distance between the overall output predictions of the two student networks using the cosine distance constraint:

This term constrains the two networks to maintain similar prediction directions in the global feature space, effectively preventing model divergence.

Subsequently, we implemented a refined, targeted contrastive learning strategy based on voxel confidence. Specifically, we classified all voxels into high-confidence and low-confidence sets according to the uncertainty generated by model predictions.

Figure 1 illustrates the specific implementation method within the hierarchical contrastive learning section. The gray dashed box indicates the high-confidence region, while the star icons represent inter-class prototypes. For the high-confidence set, we introduced a reliability metric based on inter-class separability. This metric guides data partitioning into reliable positive–negative sample pairs, which then undergo typical contrastive push–pull training. This mechanism ensures the network learns tighter intra-class cohesion and sharper inter-class boundaries within regions of high certainty. Conversely, voxels in the low-confidence set often originate from challenging regions like boundaries and ambiguous areas. Despite high uncertainty, the structural and semantic information they contain is crucial for precise segmentation and cannot be ignored. To address this, we enhance the separation of class prototypes through cross-class prototype distance metrics, focusing on prototype-level learning within this dataset. This approach ultimately improves the model’s feature discrimination capability in ambiguous and highly uncertain regions.

To achieve this, we first construct the high-confidence data pool and calculate the necessary uncertainty metrics. We utilize uncertainty metrics from the two student networks to filter reliable voxels and build the high-confidence data pool. We compute the uncertainty

of the prediction result

by performing

T Monte Carlo (MC) dropout forward passes on the student

network. Similarly, we compute the uncertainty

for the student network

. We then define the high-confidence set

:

where

computes the top 30% quantile value. Addressing class imbalance, we introduce a voxel reliability measure based on the proximity to the class prototype, reflecting the desired convergence towards class centers. For each voxel

v within the high-confidence region, the class prototype

is computed by an averaging method.

where

is the prediction mask of the student network S1 for voxels predicted as class

c, and

z represents the feature vectors obtained through the non-linear projection head. We compute the cosine similarity between the voxel feature

and the prototype

of its assigned class

:

if the feature of voxel

v highly matches its class prototype,

approaches

, indicating higher reliability. The reliability

of voxel

v is now directly expressed as the similarity between the voxel feature and its assigned class prototype, multiplied by the pseudo-label

to ensure focus on the predicted class:

In the high-confidence voxel region (

), our primary goal is to enforce consistency between the feature predictions from the two student networks. We utilize the InfoNCE loss function to calculate the contrastive loss

, weighted by the voxel-wise reliability

. The high-confidence contrastive loss is defined as

where

is the anchor feature,

is the voxel reliability weight,

is the temperature parameter, and

is the dynamically selected positive feature. The InfoNCE loss

for the anchor

is given by

where

is the negative sample set, and

is a parameter. We dynamically select the positive sample

, whose choice mechanism is entirely dependent on the prediction consistency between the two student networks. When predictions are consistent

, the positive sample for the anchor feature

is chosen as the average or a random sample from the same-class feature set

of the

network, aiming to achieve mutual knowledge alignment and feature attraction between the student networks. Conversely, when predictions are inconsistent, as the prediction of

is considered less reliable in this scenario, we switch to choosing the average or a random sample from the same-class feature set

of the

, considered less reliable in this scenario network itself, as the positive sample. This strategy enforces the alignment of features with the reliable prototypes generated by

, thereby effectively preventing the introduction of unreliable noise. Finally, the contrastive loss in the high-confidence layer, denoted as

, is defined as the sum of the high-confidence loss terms for the two student networks:

Low-confidence voxels often reflect boundary information or ambiguous regions, yet they hold valuable learning potential. For these regions, we employ a strategy of pushing away the distances between different class prototypes to enhance the model’s discriminative power at class boundaries. We define the prototype separation loss

, which directly uses the cosine similarity between distinct class prototypes

and

. For any two different classes,

and

(

), the prototype repulsion term

is defined as

where

and

are the class prototypes for class

and class

. By minimizing this loss, we successfully enforce maximum separation between different class prototypes in the feature space, thereby strengthening the model’s discriminative capability. Finally, our total contrastive learning loss,

, is defined as a weighted sum of three loss function: the total consistency loss

, the high-confidence contrastive loss

, and the low-confidence prototype separation loss

.

where

,

, and

are hyperparameters that control the weight of each loss term. The pseudocode describing the overall computational procedure is provided in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Hierarchical Contrastive Learning on Dual-Student Framework. |

Input: Unlabeled data ; weak and strong augmentations , ; student networks , ; projection heads , ; total iterations E.

- 1:

for to E do - 2:

Generate a minibatch of unlabeled data . - 3:

for each do - 4:

Obtain augmented inputs: , . - 5:

Compute predictions and . - 6:

Extract projected features and . - 7:

Compute global prediction consistency loss via Equation ( 11). - 8:

Estimate voxel-wise uncertainty via Monte Carlo Dropout. - 9:

Select high-confidence voxels using Equation ( 12). - 10:

Compute class prototypes , via Equation ( 13). - 11:

Compute voxel reliability via Equation ( 15). - 12:

for each voxel do - 13:

Determine positive feature based on prediction consistency. - 14:

Compute InfoNCE contrastive loss via Equation ( 17). - 15:

Obtain high-confidence contrastive losses and via Equation ( 16). - 16:

Compute prototype separation loss via Equation ( 19). - 17:

end for - 18:

Combine feature-level contrastive losses using Equation ( 20) - 19:

end for - 20:

end for

|

To minimize the prediction disparity between the two student networks, we introduce cross-pseudo-supervision at the data level. This strategy facilitates the accurate localization of class prototypes in the feature space, which, in turn, indirectly reduces the cosine distance between the predictions derived from the two perspectives [

46].

where

is cross-entropy loss, and

and

are the predicted pseudo-labels from

and

.

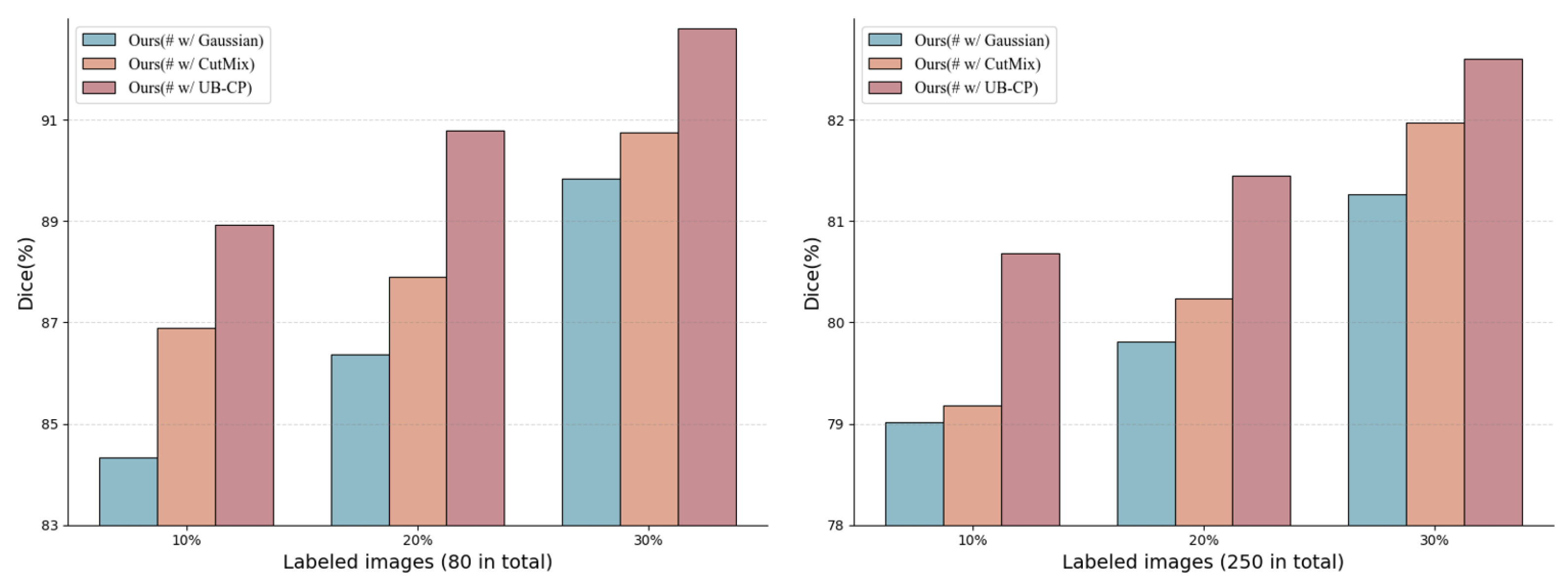

3.3. Uncertainty-Aware Bidirectional Copy–Paste Data Augmentation

To effectively bridge the potential structural and semantic distribution gap between labeled data and unlabeled data , and to mitigate noise interference caused by pseudo-label uncertainty in semi-supervised learning, we propose an uncertainty-guided bidirectional copy–paste (UB−CP) augmentation strategy. The core of this method lies in utilizing the uncertainty estimated via during the warm-up phase to dynamically and selectively guide the copy–paste operations.

During the warm-up phase of

, we employ Monte Carlo Dropout on the teacher network to estimate voxel-level uncertainty by computing the mean prediction entropy across multiple stochastic forward passes. Based on this uncertainty map, we precisely paste the regions with the highest uncertainty from the unlabeled data into the labeled data. This uncertainty-guided mechanism ensures that the regularization loss focuses on the “hard” regions where the model requires further learning. For the labeled data, we still follow the principle of BCP and utilize a zero-centered mask

for the copy–paste operation. During training, we sample one instance from each set to perform the bidirectional copy–paste operation. We copy–paste the labeled data

onto the unlabeled data

. To introduce accurate boundary information from the labeled data and enforce the model to learn boundary features on the unlabeled domain, we adopt the BCP mechanism using a zero-centered mask. To conduct the copy–paste operation between the image pair, we first generate a zero-centered mask

:

where

is the mask where the voxel value indicates whether the voxel originates from the foreground image 0 or the background image 1. The mask

is defined based on a zero-value region with size

:

where

. The parameter

controls the size ratio of the central block, and the resulting mixed volume

is generated by the formula:

This operation pastes the central block of

onto the central region of

. Subsequently, we copy–paste the unlabeled data

onto the labeled data

. This direction aims to transfer the most uncertain unlabeled regions onto the labeled data for proper regularization. We first employ the teacher network

combined with Monte Carlo Dropout to estimate the predictive uncertainty. The average prediction probability

is obtained through

forward passes:

where

N is the number of forward passes, and

is the prediction probability at voxel

v during the

n-th pass of the teacher network.

The voxel-level uncertainty is quantified using the average prediction entropy

:

where

C is the number of segmentation classes, and

is the average probability for class

c at voxel

v.

We define the target volume

for the copied patch as half of the zero-centered region, and the volume of this

is

. By sliding a window over the uncertainty map

U and selecting the two non-overlapping blocks with the highest average uncertainty,

and

, we define the indicator function

for the zero-value regions as

By combining

and

, we obtain the mask

, where the values are set to 1 within the

regions and 0 elsewhere, thus pasting the most uncertain voxel blocks from the unlabeled data onto

, forming the mixed volume

:

For the bidirectionally mixed data

and

, we feed them into the student network

to obtain the corresponding predictions

and

. To ensure data alignment, the supervision labels for consistency learning on the other student network are also constructed by mixing labeled and unlabeled data. Accordingly, the pseudo-labels for the two branches are defined as

where

and

are the binary masks used for region mixing,

denotes the pseudo-labels generated from unlabeled data, and

represents the ground-truth labels from labeled data.

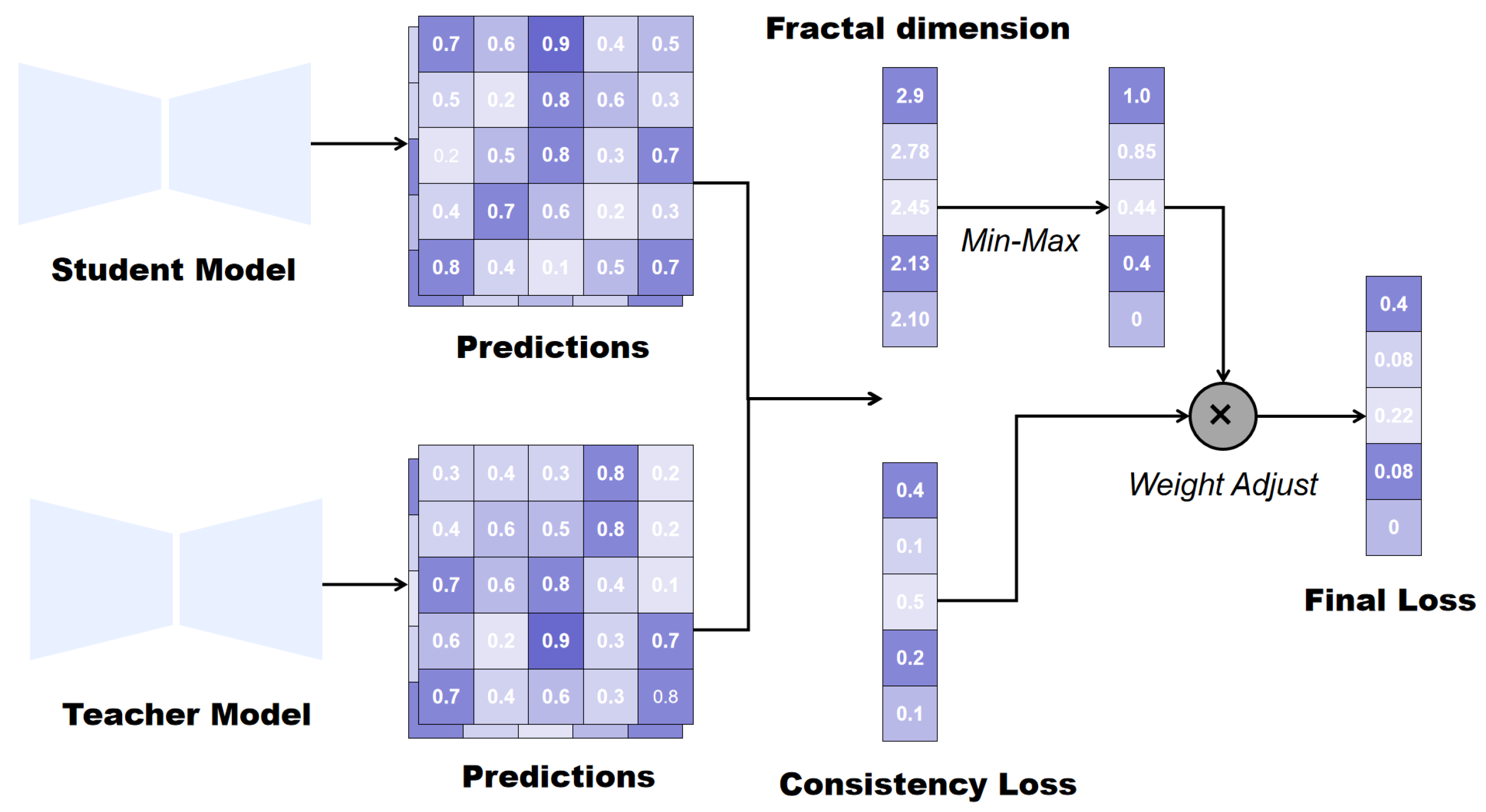

3.4. Fractal-Dimension-Weighted Consistency Regularization

Fractal dimension (FD) serves as a single metric to quantify structural complexity and irregularity, particularly effective for analyzing complex biological structures common in medical images. Regions with higher FD values indicate more intricate structures and irregular textures, often containing richer diagnostic information (e.g., organ boundaries). Standard consistency regularization often overfits simple regions and underperforms in structurally complex areas. We introduce the

to reflect local structural complexity via FD, ensuring stronger supervision signals in challenging regions.

Figure 4 illustrates the process of applying fractal dimensions to consistency regularization.

For an input 3D image volume

, we compute the local fractal dimension

for each voxel position

using the 3D box-counting method. The

is approximated by

where

r denotes the side length of the box, and

represents the minimum number of boxes with scale

r required to cover the non-zero voxels within the local block centered at voxel

v. The computation of

follows the differential box-counting strategy described in [

40]. Specifically, we set the box scale range to

. The result is a fractal-dimension map that precisely matches the spatial dimensions of the input volume.

The biological structures, such as organs, blood vessels, or tumors, although complex, are not ideal mathematical fractals. They exhibit statistical self-similarity within a finite range of scales, resulting in small differences between the calculated FD values. To increase the model’s discriminative power between different regions, we apply Min-Max normalization to the FD values. The processed weights, ranging from 0 to

, provide a clear gradient signal for consistency learning between the models:

where

is the global maximum FD,

is the global minimum FD, and

is a minimal constant.

Assigning higher weights to complex regions forces the student model to focus on aligning its predictions with the teacher model’s distribution in these challenging areas, thereby enhancing consistency along boundaries and complex structural regions. Areas with high FD values are typically critical decision regions in semantic segmentation, yet also the most error-prone. Building upon this weighted learning mechanism, we further incorporate uncertainty estimation by performing alignment only on voxels whose uncertainty falls below a predefined threshold. This approach assigns higher weights to complex regions while preserving numerical smoothness and avoiding excessive bias. The weighted consistency regularization term

is defined as

where

is the indicator function, and the constraint

ensures that the loss is only calculated for voxels

v where the uncertainty

is below the threshold

.

N is the total number of voxels, and

and

are the prediction probability distributions of the teacher and student networks, respectively.

To enable the model to learn more complex knowledge without being overly affected by noise, we empirically set an uncertainty threshold, where

computes the top

quantile value. The Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence

is given by

where

is a minimal constant set to

, introduced to maintain numerical stability.