Denatured Recognition of Biological Tissue Using Ultrasonic Phase Space Reconstruction and CBAM-EfficientNet-B0 During HIFU Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

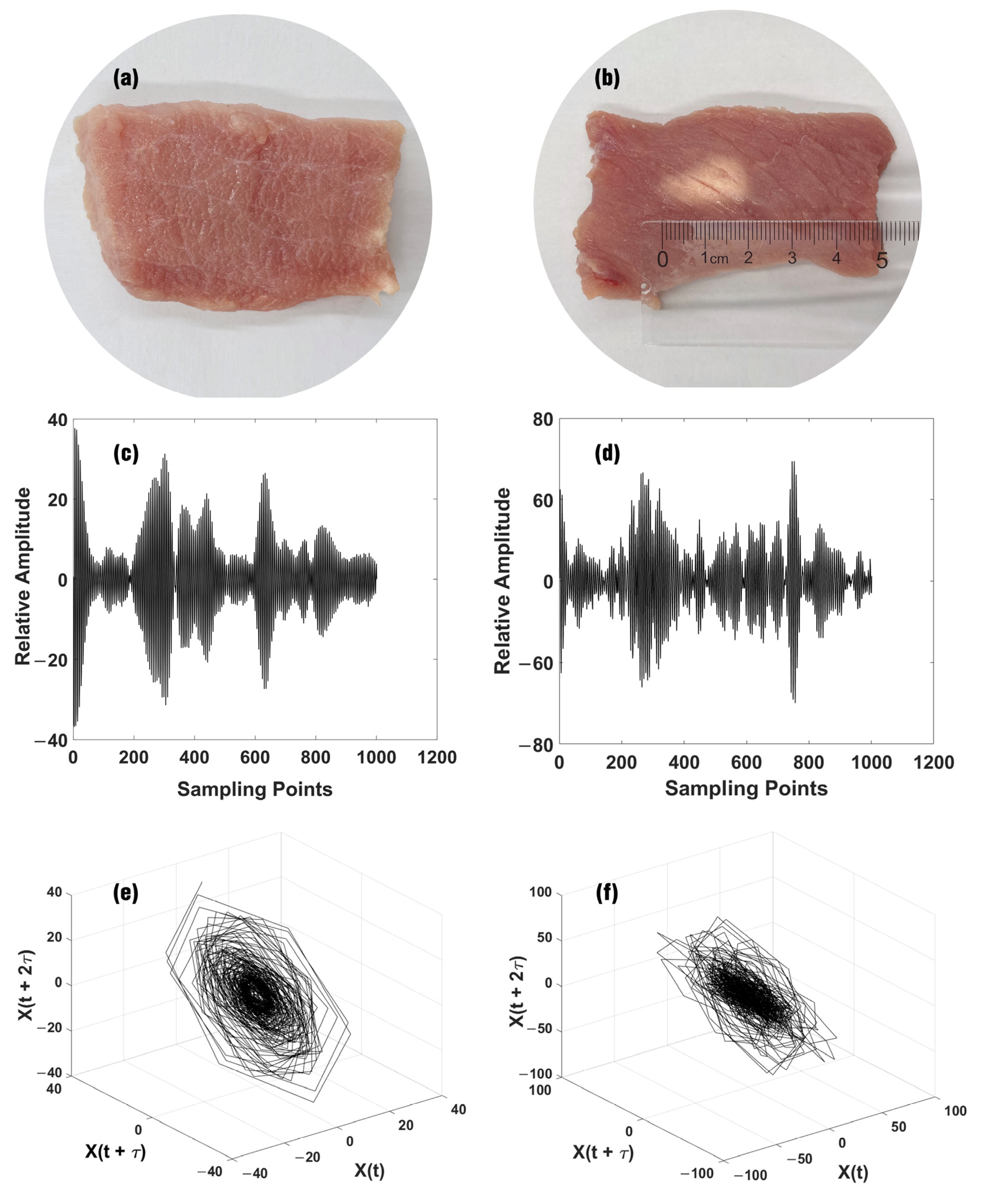

2.1. Phase Space Reconstruction

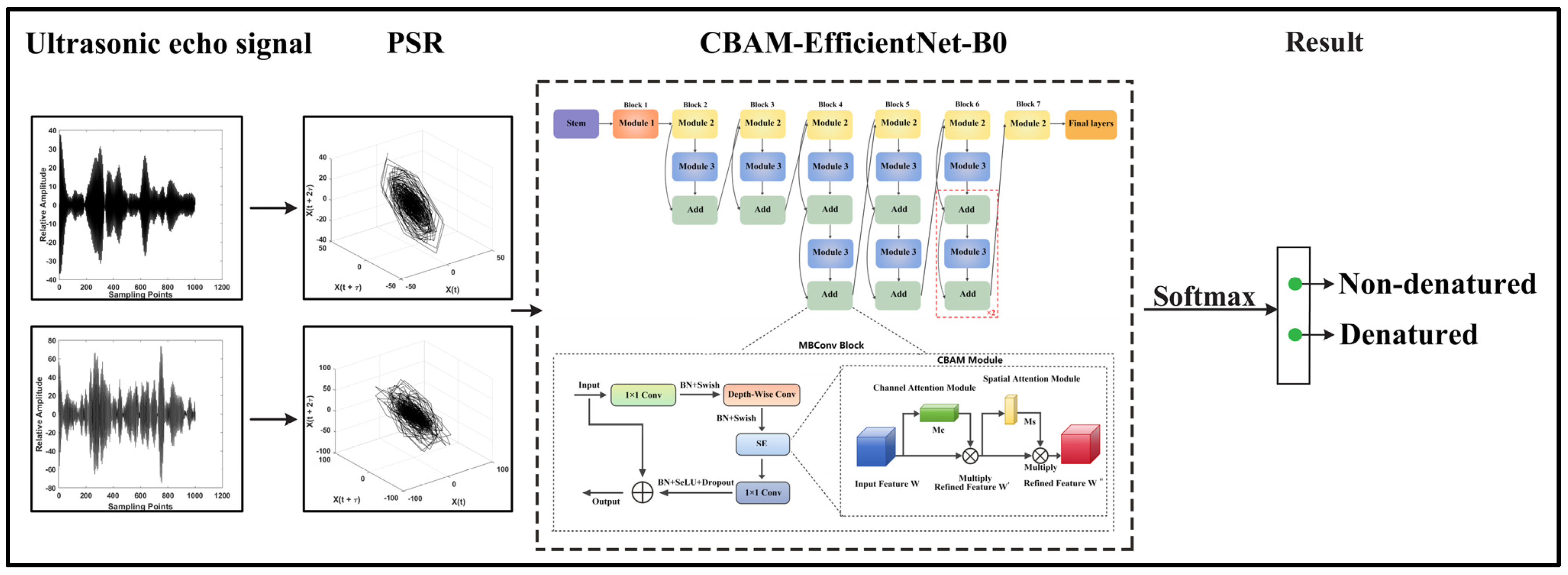

2.2. Framework Overview

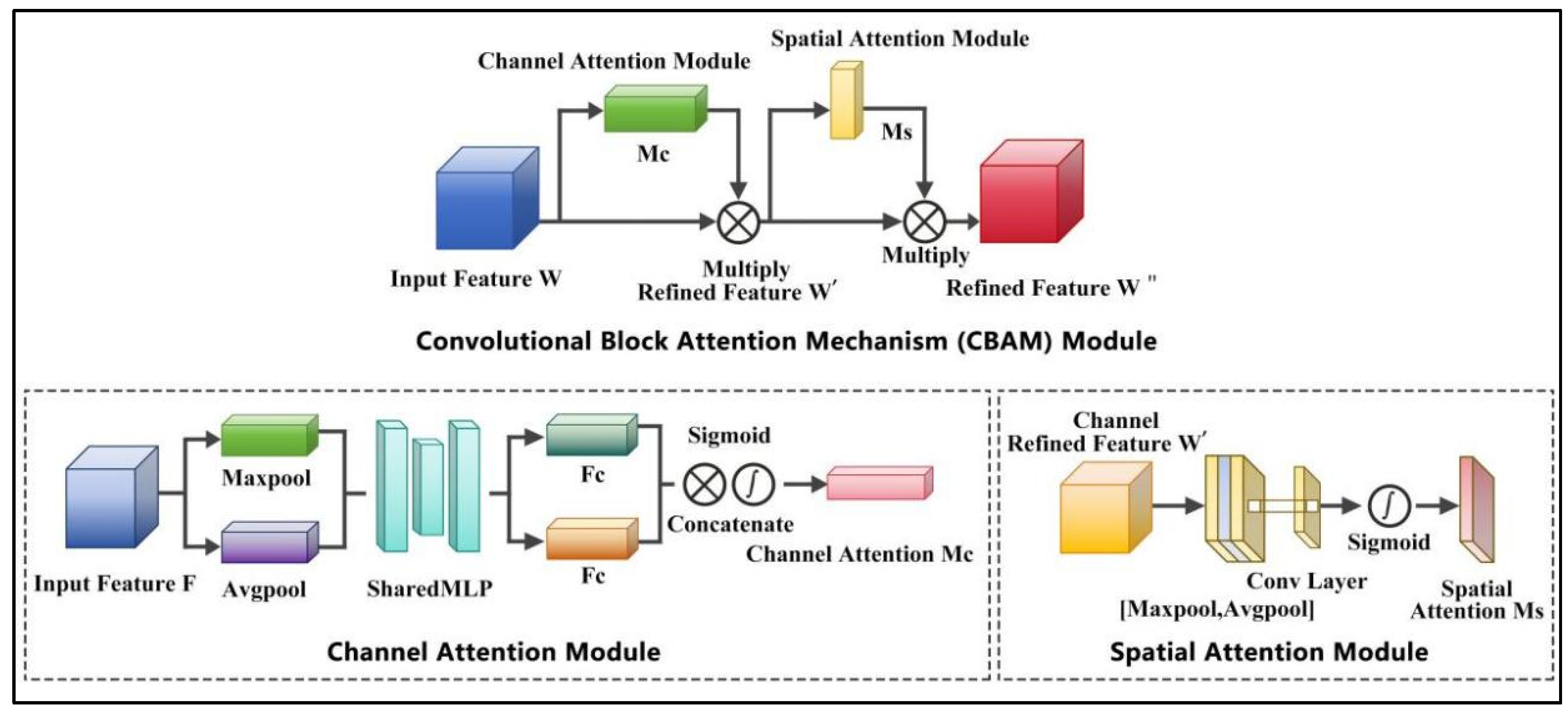

2.2.1. CBAM-EfficientNet-B0 Model

2.2.2. CNN Base Models

2.3. The Proposed Denatured Recognition System Model

- (1)

- In total, 402 echo samples from non-denatured tissues and 1210 echo samples from denatured tissues are gathered. The one-dimensional ultrasonic echo signals are converted into high-dimensional PSR trajectory diagrams by PSR technology to form an ultrasonic echo signal dataset.

- (2)

- Transfer learning is adopted, in which the pre-trained EfficientNet-B0 architecture is utilized as the learning basis to train a new model aimed at identifying HIFU-induced denaturation of biological tissues. Enhance the feature extraction capability by using the CBAM module. The SeLU activation function combined with Dropout is adopted to effectively accelerate model convergence. The cosine annealing strategy is adopted to modulate the learning rate during training, helping the model escape the local optimal solution and achieve better performance.

- (3)

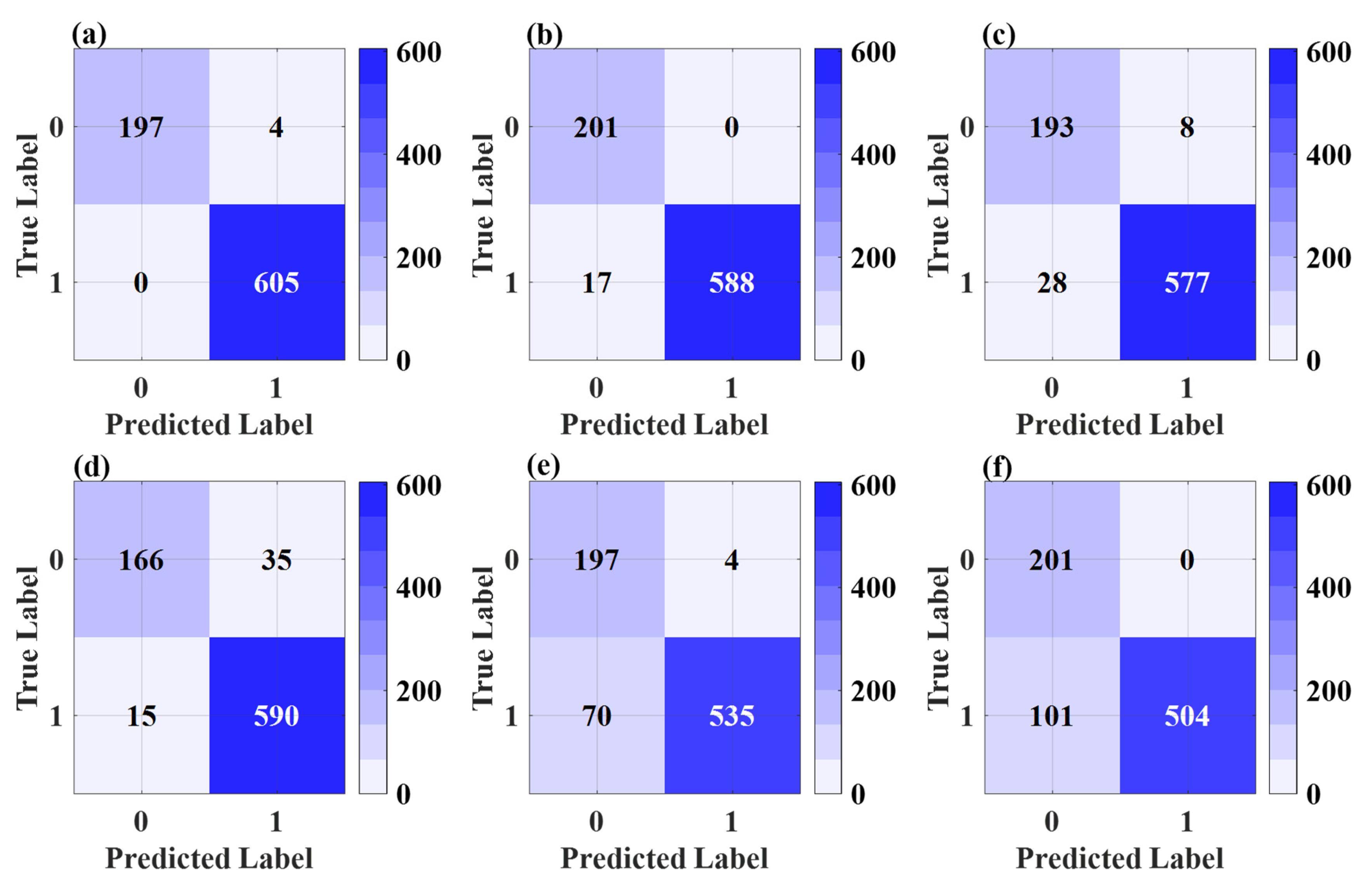

- The ultrasonic echo signals training set is trained using the CBAM-EfficientNet-B0 model. The test set is identified using the trained CBAM-EfficientNet-B0 and other comparison models (VGG16, ResNet18, ResNet101, DenseNet201, EfficientNet-B0). The t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) technique is used to visualize the distribution of denaturation features of different models [46], and the accuracy, standard deviation, precision, recall, and F1-Score of different models are compared to illustrate the advantages of the proposed method.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Experimental Data and Analysis

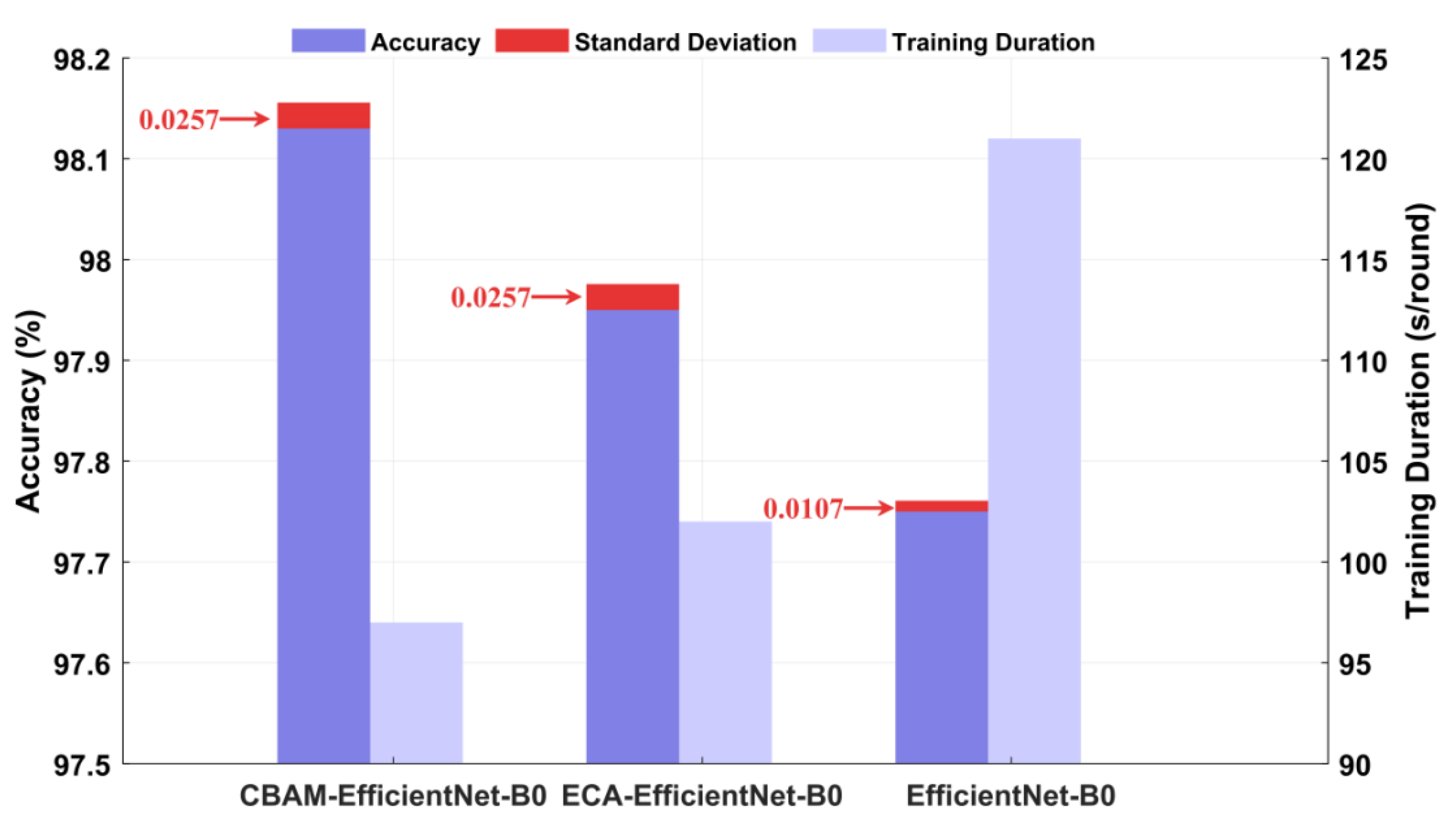

3.2. Ablation Experiment

3.2.1. The Influence of the Attention Mechanism Module on Model Performance

3.2.2. The Influence of Activation Functions on Model Performance

3.2.3. The Influence of Learning Rate Scheduling Strategies on Model Performance

3.3. Training Learning Process

3.4. Recognition Result

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yuldashev, P.V.; Karzova, M.M.; Kreider, W.; Rosnitskiy, P.B.; Sapozhnikov, O.A.; Khokhlova, V.A. “HIFU Beam:” A simulator for predicting axially symmetric nonlinear acoustic fields generated by focused transducers in a layered medium. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2021, 68, 2837–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Li, Q.; Liu, H.; Zeng, Q.; Cai, D.; Xu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Tsui, P.H.; Zhou, X. Suppressing HIFU interference in ultrasound images using 1D U-Net-based neural networks. Phys. Med. Biol. 2024, 69, 075006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, M.; Barrere, V.; Treilleux, I.; Chopin, N.; Melodelima, D. Development of a noninvasive HIFU treatment for breast adenocarcinomas using a toroidal transducer based on preliminary attenuation measurements. Ultrasonics 2021, 115, 106459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, G.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Liao, H. Real-time and multimodality image-guided intelligent HIFU therapy for uterine fibroid. Theranostics 2020, 10, 4676–4691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebeke, L.C.; Gómez, J.D.C.; Heijman, E.; Rademann, P.; Simon, A.C.; Ekdawi, S.; Grüll, H. Hyperthermia-induced doxorubicin delivery from thermosensitive liposomes via MR-HIFU in a pig model. J. Control. Release 2022, 343, 798–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.; Agarwal, A.; Kumaradas, J.C.; Kolios, M.C.; Peyman, G.; Tavakkoli, J.J. Real-time non-invasive control of ultrasound hyperthermia using high-frequency ultrasonic backscattered energy in ex vivo tissue and in vivo animal studies. Phys. Med. Biol. 2024, 69, 215001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karwat, P.; Kujawska, T.; Lewin, P.A.; Secomski, W.; Gambin, B.; Litniewski, J. Determining temperature distribution in tissue in the focal plane of the high (>100 W/cm2) intensity focused ultrasound beam using phase shift of ultrasound echoes. Ultrasonics 2016, 65, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Qian, S.; Tan, Q.; Zou, X.; Liu, B. Temperature measurement using passive harmonics during high intensity focused ultrasound exposures in porcine tissue. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2018, 134, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Xie, W.; Zhou, X.; Tan, J.; Wang, Z.; Du, Y.; Li, Y. Real-time monitoring of high intensity focused ultrasound focal damage based on transducer driving signal. Acta Phys. Sin. 2022, 71, 037201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Cao, J.; Liu, B. Recognition of biological tissue denaturation based on improved multiscale permutation entropy and GK fuzzy clustering. Information 2022, 13, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Hu, W.; Zou, X.; Ding, Y.; Qian, S. Recognition of denatured biological tissue based on variational mode decomposition and multi-scale permutation entropy. Acta Phys. Sin. 2019, 68, 028702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Qian, S.; Zhang, X. Denatured recognition of biological tissue based on multi-scale phase weighted-permutation entropy during HIFU treatment. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2023, 34, 095701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.Q.; Zhang, H.; Liu, B.; Tang, H.; Qian, S.Y. Identification of denatured and normal biological tissues based on compressed sensing and refined composite multi-scale fuzzy entropy during high intensity focused ultrasound treatment. Chin. Phys. B 2021, 30, 028704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.J.; Yuan, Z.Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, J.; Xue, H.H.; Tu, J.; Zhang, D. Method of spatiotemporally monitoring acoustic cavitation based on radio frequency signal entropy analysis. Acta Phys. Sin. 2022, 71, 174301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Liu, G.; Qu, X. Comparing the Influence of Different-Order HIFU Harmonic Superposition on Focal Temperature of Biological Tissue. Iran. J. Med. Phys. 2025, 22, 279–289. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.; Li, Q.; Xu, J.; Tang, M.X.; Wang, Z.; Tsui, P.H.; Zhou, X. Frequency-Domain robust PCA for Real-Time Monitoring of HIFU Treatment. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2024, 43, 3001–3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Sapozhnikov, O.A.; Khokhlova, V.A.; Son, H.; Totten, S.; Wang, Y.N.; Khokhlova, T.D. Dynamic Mode Decomposition Based Doppler Monitoring of De Novo Cavitation Induced by Pulsed HIFU: An In Vivo Feasibility Study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Y.; Xu, J.; Shi, X.; Liu, Y.; Cai, D.; Zhou, X. Study on Preoperative HIFU Focus Prediction Using Harmonic Motion Imaging. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control Joint Symposium (UFFC-JS), Montreal, QC, Canada, 1–4 September 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Payen, T.; Crouzet, S.; Guillen, N.; Chen, Y.; Chapelon, J.Y.; Lafon, C.; Catheline, S. Passive Elastography for Clinical HIFU Lesion Detection. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2023, 43, 1594–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, A.B.; Karim, A.; Ocotl, E.; Dones, J.M.; Chacko, J.V.; Liu, A.; Eliceiri, K.W. Optical imaging of collagen fiber damage to assess thermally injured human skin. Wound Repair Regen. 2020, 28, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Chen, W.L.; Lin, S.J.; Jee, S.H.; Chen, Y.F.; Lin, L.C.; Dong, C.Y. Investigating mechanisms of collagen thermal denaturation by high resolution second-harmonic generation imaging. Biophys. J. 2006, 91, 2620–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galaktionov, I.V.; Kudryashov, A.V.E.; Sheldakova, Y.V.; Byalko, A.A.; Borsoni, G. Measurement and correction of the wavefront of the laser light in a turbid medium. Quantum Electron. 2017, 47, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, N.; Chapman, G.H.; Kaminska, B. Optical Imaging of Structures within Highly Scattering Material Using an Incoherent Beam and a Spatial Filter. In Optical Interactions with Tissues and Cells XXI; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2010; Volume 7562, pp. 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Ling, B.W.K.; Ahmed, W.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, H. Multivariate phase space reconstruction and Riemannian manifold for sleep stage classification. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 88, 105572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Taralova, I.; Loiseau, J.J.; Slavov, T.; Pandey, M. Frequency Domain Identification of a 1-DoF and 3-DoF Fractional-Order Duffing System Using Grünwald–Letnikov Characterization. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, A.; Martinez-Rodrigo, A.; Bertomeu-Gonzalez, V.; Ayo-Martin, O.; Rieta, J.J.; Alcaraz, R. Single-lead electrocardiogram quality assessment in the context of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation through phase space plots. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 91, 105920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, H.; Sadiq, M.T.; Rehman, A.U.; Ghazvini, M.; Naqvi, R.A.; Payan, M.; Bagheri, H. Depression recognition based on the reconstruction of phase space of EEG signals and geometrical features. Appl. Acoust. 2021, 179, 108078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Qiu, W.; Hu, X.; Wang, W. A rolling bearing fault diagnosis technique based on recurrence quantification analysis and Bayesian optimization SVM. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 156, 111506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhou, J.; Gou, F.; Wu, J. TransRNetFuse: A highly accurate and precise boundary FCN-transformer feature integration for medical image segmentation. Complex Intell. Syst. 2025, 11, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenecssha, P.; Balasubramanian, V.K.; Murugappan, M. WBC-KICNet: Knowledge-infused convolutional neural network for white blood cell classification. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 2024, 5, 035086. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Xie, P.; Dai, Z.; Wu, J. Self-supervised tumor segmentation and prognosis prediction in osteosarcoma using multiparametric MRI and clinical characteristics. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2024, 244, 107974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Li, S.; Han, J.; Ren, F.; Yang, Z. Review of Lightweight Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2024, 31, 1915–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Yang, L.T.; Zhang, Q.; Armstrong, D.; Deen, M.J. Convolutional neural networks for medical image analysis: State-of-the-art, comparisons, improvement and perspectives. Neurocomputing 2021, 444, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Luo, T.; Zeng, J.; Gou, F. Continuous refinement-based digital pathology image assistance scheme in medical decision-making systems. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2024, 28, 2091–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Miao, M.; Zhang, K.; Liu, W.; Sheng, Z.; Xu, B.; Hu, W. MSMGE-CNN: A multi-scale multi-graph embedding convolutional neural network for motor related EEG decoding. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 2024, 5, 045047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, P.; Yu, K.; Wei, W.; Tan, Y.; Wu, J. Big data analytics on lung cancer diagnosis framework with deep learning. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2023, 21, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.C.; Joo, Y.; Lee, O.J.; Lee, K.; Song, T.K.; Choi, C.; Yoon, C. Automated classification of liver fibrosis stages using ultrasound imaging. BMC Med. Imaging 2024, 24, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.; Yuan, L.; Li, P.; Liu, P. Real-time automatic assisted detection of uterine fibroid in ultrasound images using a deep learning detector. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2023, 49, 1616–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Huang, L.; Ding, L.; Yan, S. Deep Brain Tumor Lesion Classification Network: A Hybrid Method Optimizing ResNet50 and EfficientNetB0 for Enhanced Feature Extraction. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshminarasimha, K.; Priyeshkumar, A.T.; Karthikeyan, M.; Sakthivel, R. Enhancing Lung Cancer Diagnosis: An Optimization-Driven Deep Learning Approach with CT Imaging. Cancer Investig. 2025, 43, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.; Shaikh, Z.A.; Khan, A.A.; Laghari, A.A. Multiclass skin cancer classification using EfficientNets-a first step towards preventing skin cancer. Neurosci. Inform. 2022, 2, 100034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. A novel ResNet101 model based on dense dilated convolution for image classification. SN Appl. Sci. 2022, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 4700–4708. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Theckedath, D.; Sedamkar, R.R. Detecting affect states using VGG16, ResNet50 and SE-ResNet50 networks. SN Comput. Sci. 2020, 1, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Maaten, L.; Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2008, 9, 2579–2605. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Yang, G.; Yuan, Y.; Sun, J.; Pu, G. Effects of Scale Parameters and Counting Origins on Box-Counting Fractal Dimension and Engineering Application in Concrete Beam Crack Analysis. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xie, H.; Wu, F.; Li, C.; Gao, R. A Novel Box-Counting Method for Quantitative Fractal Analysis of Three-Dimensional Pore Characteristics in Sandstone. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2024, 34, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Class | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBAM-EfficientNet-B0 | Denatured | 0.9934 | 1.0000 | 0.9967 |

| Non-Denatured | 1.0000 | 0.9801 | 0.9899 | |

| EfficientNet-B0 | Denatured | 1.0000 | 0.9719 | 0.9858 |

| Non-Denatured | 0.9220 | 1.0000 | 0.9594 | |

| ResNet101 | Denatured | 0.9863 | 0.9537 | 0.9698 |

| Non-Denatured | 0.8733 | 0.9602 | 0.9146 | |

| DenseNet201 | Denatured | 0.9440 | 0.9752 | 0.9593 |

| Non-Denatured | 0.9171 | 0.8259 | 0.8691 | |

| ResNet18 | Denatured | 0.9926 | 0.8843 | 0.9353 |

| Non-Denatured | 0.7378 | 0.9801 | 0.8419 | |

| VGG16 | Denatured | 1.0000 | 0.8331 | 0.9089 |

| Non-Denatured | 0.6656 | 1.0000 | 0.7992 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, B.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, X. Denatured Recognition of Biological Tissue Using Ultrasonic Phase Space Reconstruction and CBAM-EfficientNet-B0 During HIFU Therapy. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 819. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120819

Liu B, Zhu H, Zhang X. Denatured Recognition of Biological Tissue Using Ultrasonic Phase Space Reconstruction and CBAM-EfficientNet-B0 During HIFU Therapy. Fractal and Fractional. 2025; 9(12):819. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120819

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Bei, Haitao Zhu, and Xian Zhang. 2025. "Denatured Recognition of Biological Tissue Using Ultrasonic Phase Space Reconstruction and CBAM-EfficientNet-B0 During HIFU Therapy" Fractal and Fractional 9, no. 12: 819. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120819

APA StyleLiu, B., Zhu, H., & Zhang, X. (2025). Denatured Recognition of Biological Tissue Using Ultrasonic Phase Space Reconstruction and CBAM-EfficientNet-B0 During HIFU Therapy. Fractal and Fractional, 9(12), 819. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120819