Analysis of Piecewise Terminal Fractional System: Theory and Application to TB Treatment Model with Drug Resistance Development

Abstract

1. Introduction and Motivations

- for all and is continuous and bounded on

- and is a given continuous function;

- is the piecewise derivative of order with classical and ABC fractional derivative defined by

- is the classical derivative of on

- is the ABC fractional derivative on

2. Preliminary and Essential Concepts

- (i)

- ,

- (ii)

- is the ABC-FD on .

- (i)

- (ii)

- , ;

- (iii)

- is a normalization function such that .

3. Main Result

3.1. Existence Result

3.2. Uniqueness Result

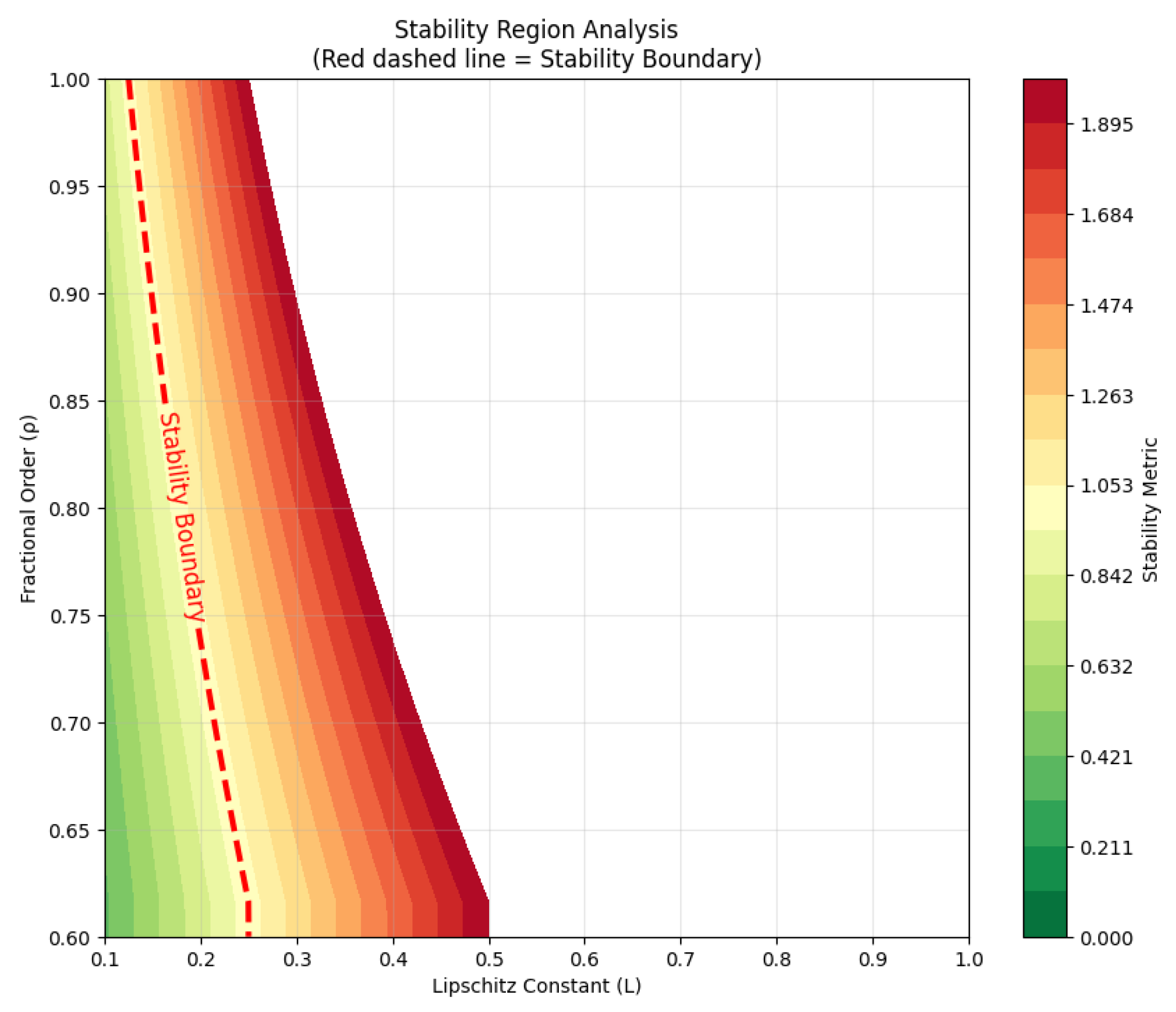

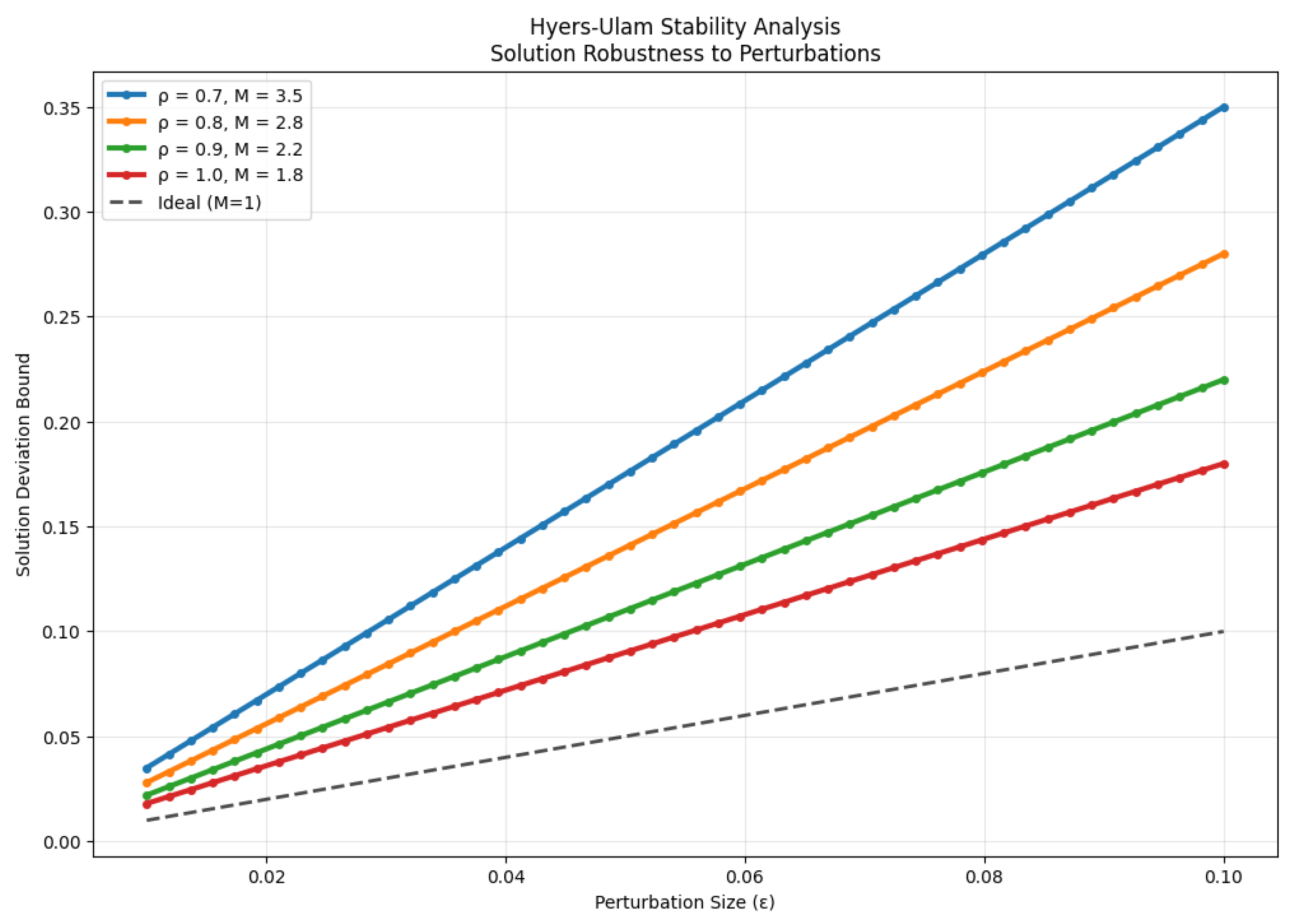

3.3. Hyers–Ulam Stability

- (i)

- (ii)

4. An Example

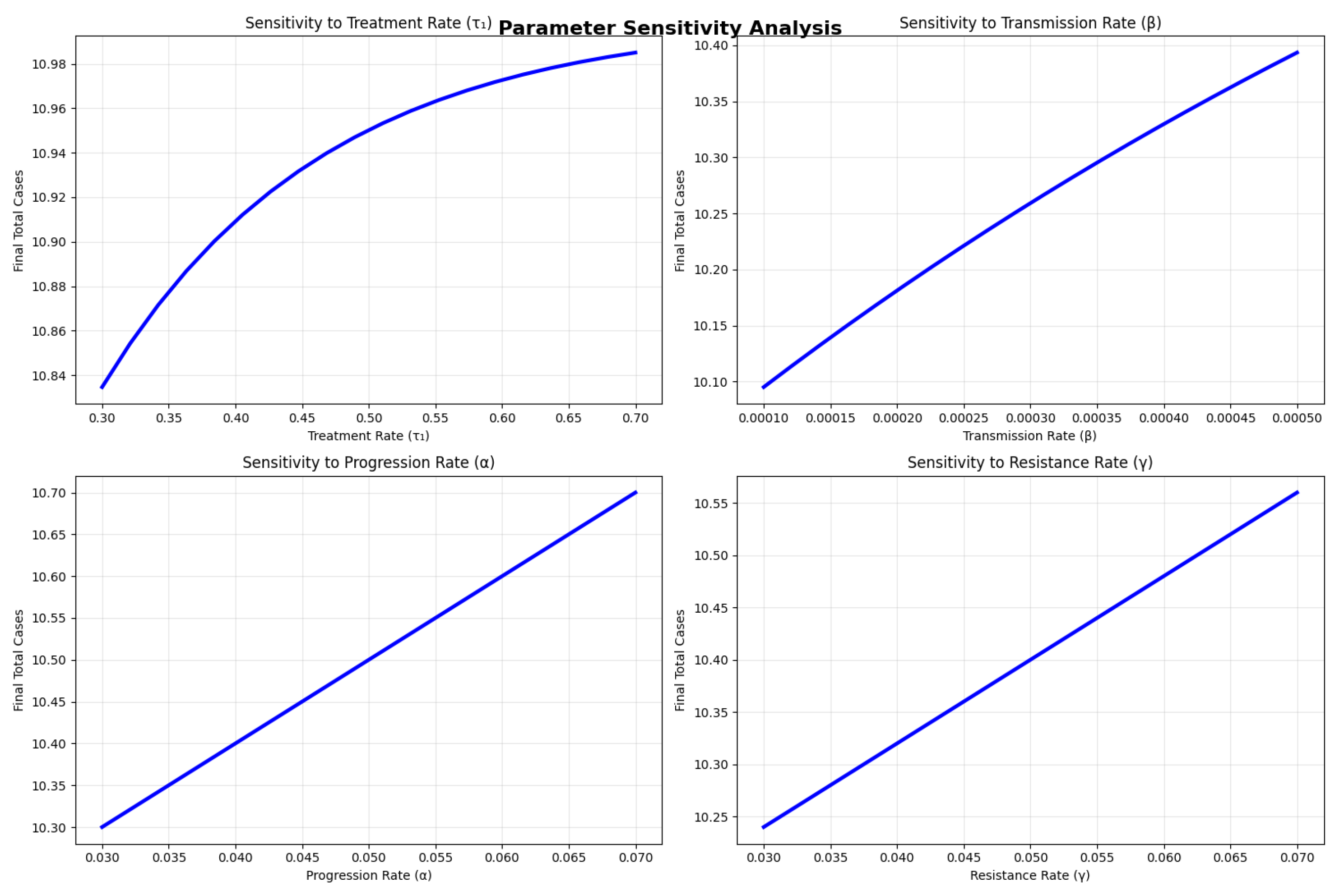

5. An Application to TB Treatment

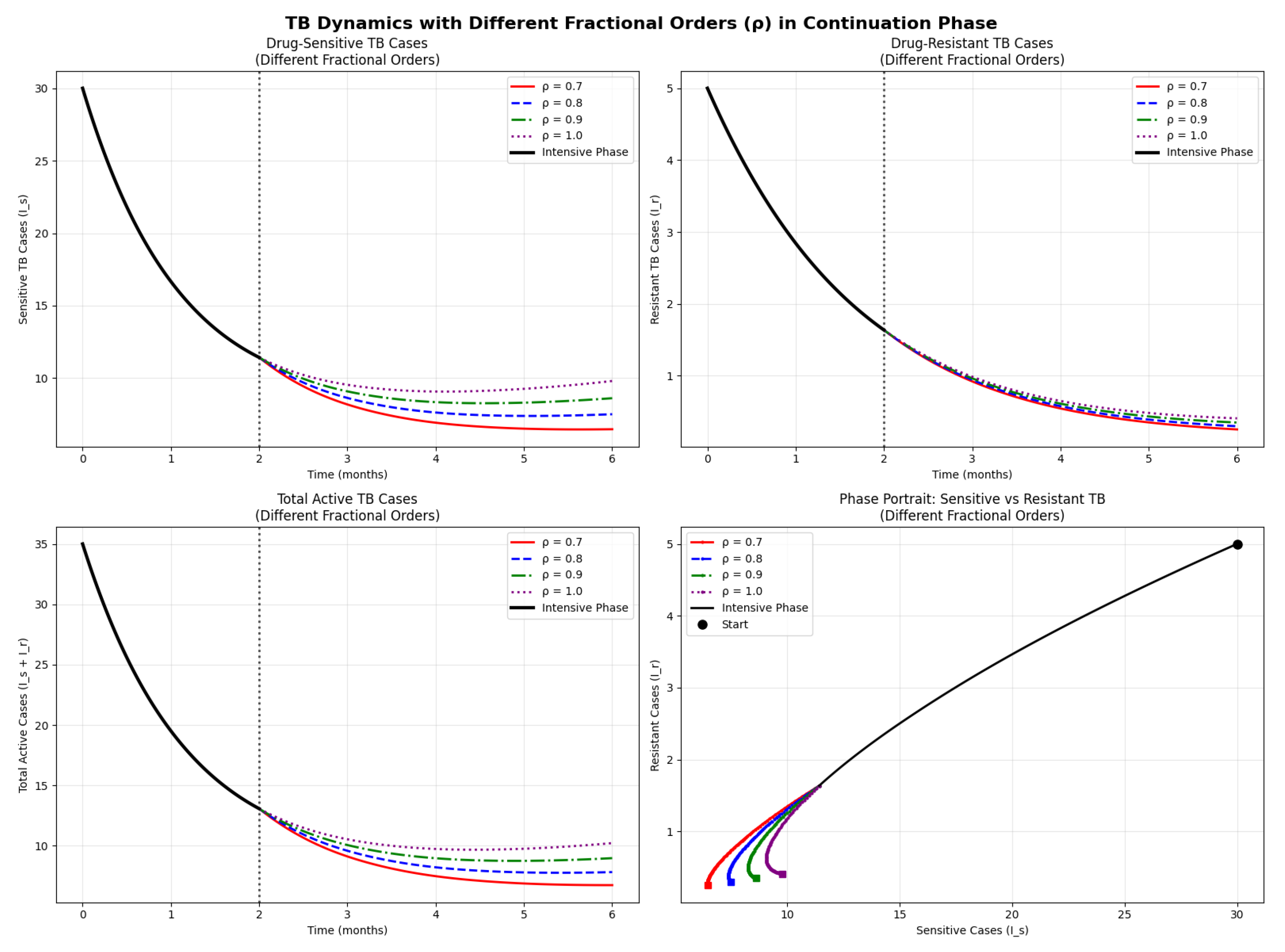

5.1. Phase 1 (Intensive Phase (Classical Dynamics) )

5.2. Phase 2 (Continuation Phase (Fractional Dynamics with Memory) )

5.3. Piecewise Structure Interpretation in Biology

- Phase 1 (): The first intensive phase models the direct, immediate effects of high-potency medication therapy using classical derivatives. This stage is dominated by pharmacodynamics rather than sophisticated immune memory and concentrates on quick bacterial destruction.

- Phase 2 (): To capture the long-term immunological memory effects, such as T-cell memory development, long-lasting medication effects, and the cumulative history of immune responses, the continuation phase uses the ABC fractional derivative. The memory of latent infection dynamics and resistance development routes are denoted by the words ML(L,t) and MR(Ir,t), respectively.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Podlubny, I. Fractional Differential Equations; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Samko, S.G.; Kilbas, A.A.; Marichev, O.I. Fractional Integrals and Derivatives; Gordon and Breach: Yverdon, Switzerland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, K.S.; Ross, B. An Introduction to the Fractional Calculus and Fractional Differential Equations; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Magin, R.L. Fractional Calculus in Bioengineering; Begell House: Redding, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kilbas, A.A.; Srivastava, H.M.; Trujillo, J.J. Theory and Applications of Fractional Differential Equations. In North-Holland Mathematics Studies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Atangana, A.; Baleanu, D. New fractional derivatives with nonlocal and non-singular kernel: Theory and application to heat transfer model. Therm. Sci. 2016, 20, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atangana, A.; Koca, I. Chaos in a simple nonlinear system with Atangana-Baleanu derivatives with fractional order. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2016, 89, 447–454. [Google Scholar]

- Almalahi, M.A.; Aldwoah, K.A.; Shah, K.; Abdeljawad, T. Stability and numerical analysis of a coupled system of piecewise Atangana-Baleanu fractional differential equations with delays. Qual. Theory Dyn. Syst. 2024, 23, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.U.; Farman, M.; Nisar, K.S.; Ahmad, A.; Munir, Z.; Hincal, E. Investigation and application of a classical piecewise hybrid with a fractional derivative for the epidemic model: Dynamical transmission and modeling. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atangana, A.; Koca, I. On the new fractional derivative and application to nonlinear Baggs and Freedman model. J. Nonlinear Sci. Appl. 2016, 9, 2467–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atangana, A. On the new fractional derivative and application to nonlinear Fisher’s reaction- diffusion equation. Appl. Math. Comput. 2016, 273, 948–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trachoo, K.; Chaiya, I.; Phakmee, S.; Prathumwan, D. Dynamics of Bone Remodeling by Using Mathematical Model Under ABC Time-Fractional Derivative. Symmetry 2025, 17, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atangana, A.; Araz, S.İ. New concept in calculus: Piecewise differential and integral operators. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 145, 110638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehestani, H.; Ordokhani, Y.; Razzaghi, M. Piecewise numerical approach for solving piecewise fractional optimal control and variational problems. Numer. Algorithms 2025, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.U.; Tabassum, S.; Althobaiti, A.; Waseem; Althobaiti, S. An analysis of fractional piecewise derivative models of dengue transmission using deep neural network. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 2024, 18, 2340871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.; Abdeljawad, T.; Ali, A. Mathematical analysis of the Cauchy type dynamical system under piecewise equations with Caputo fractional derivative. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 161, 112356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchohra, M.; Bouriah, S.; Nieto, J.J. Terminal value problem for differential equations with Hilfer-Katugampola fractional derivative. Symmetry 2019, 11, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalahi, M.A.; Abdo, M.S.; Panchal, S.K. On the theory of fractional terminal value problem with ψ-Hilfer fractional derivative. AIMS Mathematics 2020, 5, 4889–4908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boichuk, O.; Feruk, V. Terminal value problem for the system of fractional differential equations with additional restrictions. Math. Model. Anal. 2025, 30, 120–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.H.; ur Rehman, M. A note on terminal value problems for fractional differential equations on infinite interval. Appl. Math. Lett. 2016, 52, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, P.A.; Farman, M.; Jamil, K.; Nisar, K.S.; Hashmi, M.A.; Huang, Z. Modeling and analysis using piecewise hybrid fractional operator in time scale measure for ebola virus epidemics under Mittag-Leffler kernel. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisar, K.S.; Farman, M.; Jamil, K.; Akgul, A.; Jamil, S. Computational and stability analysis of Ebola virus epidemic model with piecewise hybrid fractional operator. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banach, S. Sur les opérations dans les ensembles abstraits et leur application aux équations intégrales. Fundam. Math. 1922, 3, 133–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulam, S.M. A Collection of Mathematical Problems; Interscience Publishers: Geneva, Switzerland, 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Rassias, T.M. On the stability of the linear mapping in Banach spaces. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 1994, 122, 733–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Definition | Typical Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Parameters | ||

| Recruitment rate | people/month | |

| Natural mortality rate | 1/month | |

| Transmission Parameters | ||

| Transmission coefficient | 1/(person·month) | |

| Relative transmissibility | dimensionless | |

| Disease Progression Parameters | ||

| Progression rate | 1/month | |

| Disease-induced death rate (sensitive) | 1/month | |

| Disease-induced death rate (resistant) | 1/month | |

| Treatment Parameters | ||

| Treatment rate for sensitive TB | 1/month | |

| Treatment rate for resistant TB | 1/month | |

| Treatment failure/relapse rate | 1/month | |

| Resistance acquisition rate | dimensionless | |

| Clinical Protocol Parameters | ||

| Switching time | month | |

| S | Total treatment duration | month |

| Target (sensitive TB) | people | |

| Target for resistant TB | people | |

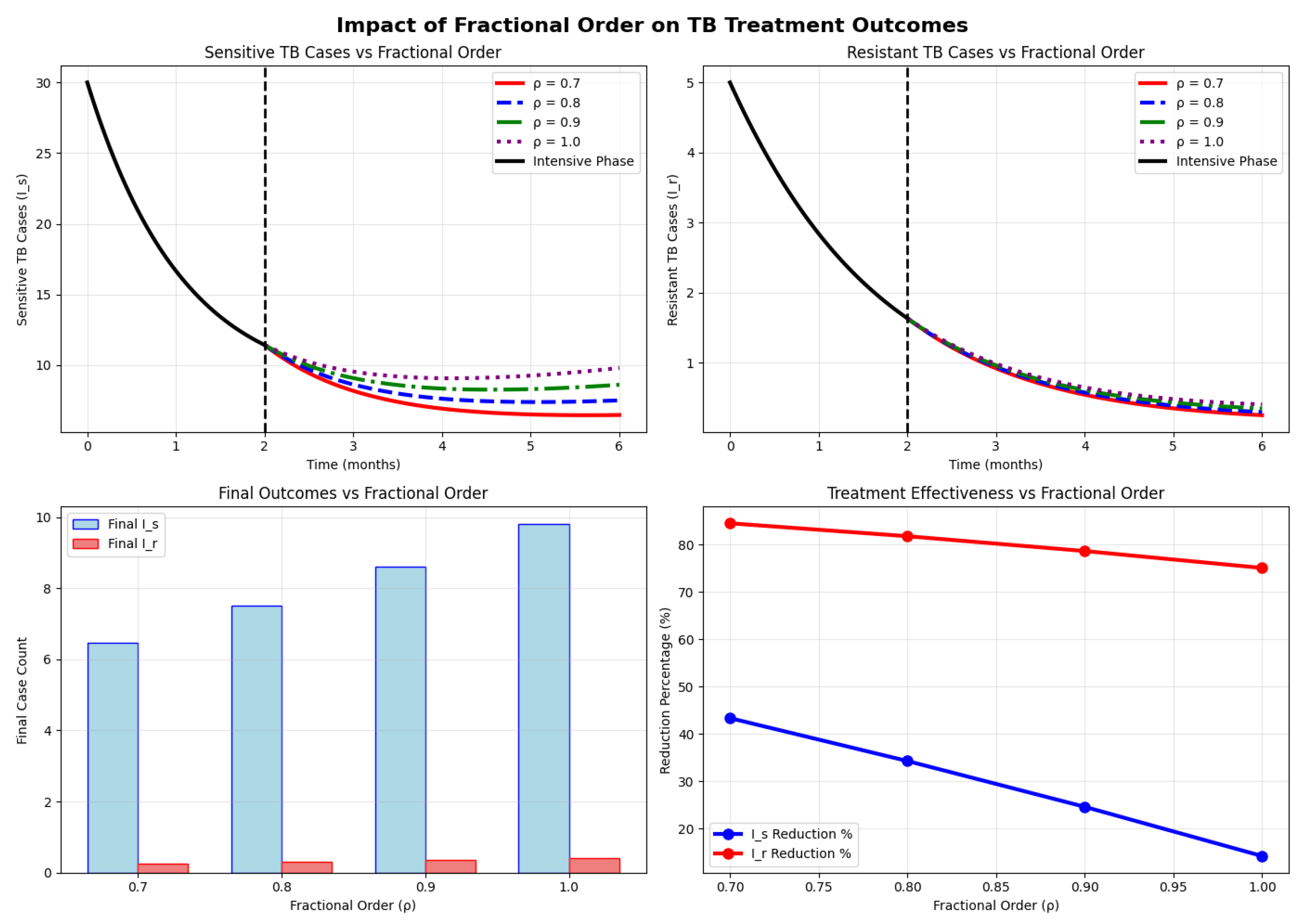

| Fractional Order | Final | Final | Total Reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.7 | 6.48 | 0.25 | 48.5 |

| 0.8 | 7.51 | 0.30 | 40.2 |

| 0.9 | 8.62 | 0.35 | 31.4 |

| 1.0 | 9.80 | 0.41 | 21.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Madani, Y.A.; Almalahi, M.; Rabih, M.; Aldwoah, K.; Qurtam, A.A.; Haron, N.; Adam, A. Analysis of Piecewise Terminal Fractional System: Theory and Application to TB Treatment Model with Drug Resistance Development. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 807. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120807

Madani YA, Almalahi M, Rabih M, Aldwoah K, Qurtam AA, Haron N, Adam A. Analysis of Piecewise Terminal Fractional System: Theory and Application to TB Treatment Model with Drug Resistance Development. Fractal and Fractional. 2025; 9(12):807. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120807

Chicago/Turabian StyleMadani, Yasir A., Mohammed Almalahi, Mohammed Rabih, Khaled Aldwoah, Ashraf A. Qurtam, Neama Haron, and Alawia Adam. 2025. "Analysis of Piecewise Terminal Fractional System: Theory and Application to TB Treatment Model with Drug Resistance Development" Fractal and Fractional 9, no. 12: 807. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120807

APA StyleMadani, Y. A., Almalahi, M., Rabih, M., Aldwoah, K., Qurtam, A. A., Haron, N., & Adam, A. (2025). Analysis of Piecewise Terminal Fractional System: Theory and Application to TB Treatment Model with Drug Resistance Development. Fractal and Fractional, 9(12), 807. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120807