1. Introduction

Magnetic levitation (Maglev) systems have long served as canonical benchmarks in modern control engineering due to their intrinsic nonlinearity, open-loop instability, and sensitivity to parameter variations. Among these, the magnetic-ball suspension (MBS) configuration represents a classical and experimentally tractable example, wherein a steel ball is levitated by an electromagnetic actuator without mechanical contact. Such systems are inherently unstable because the electromagnetic force depends nonlinearly on coil current and ball position, requiring continuous feedback control to maintain equilibrium [

1]. Achieving robust and precise levitation remains a critical challenge that continues to motivate the development of advanced control strategies [

2].

Historically, the control of Maglev systems began with classical linear techniques such as proportional–integral–derivative (PID) controllers because of their conceptual simplicity and ease of real-time implementation [

3,

4]. However, linear PID designs often struggle with the strong nonlinearity of electromagnetic actuation, leading to high overshoot, long settling times, and inadequate robustness under parameter drift or external disturbances [

5]. Consequently, researchers proposed various extensions of PID control, including the proportional–integral–derivative–acceleration (PIDA) and real PIDD

2 structures [

6,

7]. Multi-degree-of-freedom (2-DOF and 3-DOF) PID variants were also developed to improve decoupling between reference tracking and disturbance rejection [

8].

Parallel to these developments, fractional-order control emerged as a powerful paradigm for nonlinear dynamic systems. Fractional-order PID (FOPID) controllers, characterized by non-integer integration and differentiation orders (λ, μ), provide an additional degree of tuning flexibility and can emulate memory and hereditary properties absent in integer-order counterparts. Experimental and simulation studies have demonstrated that FOPID improves robustness and disturbance rejection for Maglev and electromagnetic suspension systems [

9,

10,

11].

In addition to fractional-order control, researchers have explored a wide range of nonlinear and adaptive control strategies, including fuzzy PID [

12], neural-network-based control [

13], adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference systems (ANFISs) [

14], sliding-mode control (SMC) [

15], model-predictive control (MPC) [

16], model-reference adaptive control (MRAC) [

17], and cascaded or lead–lag compensators [

18]. Each method offers improvements in adaptability or robustness but frequently entails higher computational demand and more intricate tuning.

The current literature can broadly be categorized into three methodological clusters: (1) classical and multi-DOF PID controllers, (2) fractional-order and nonlinear PID architectures and (3) optimization-driven intelligent controllers. Studies related to real PIDD

2 [

19] and 2-DOF PID [

20] structures achieve improved transient performance and phase compensation. However, their robustness remains limited under strong nonlinearity. FOPID controllers [

21] were shown to outperform integer PIDs in both stability margins and control effort. Nonlinear augmentations (including fuzzy PID, sigmoid PID, and exponential PID) have been introduced to improve control smoothness [

22,

23,

24].

The integration of metaheuristic algorithms has revolutionized tuning practices for nonlinear control. Algorithms such as particle swarm optimization (PSO) [

25], genetic algorithm (GA) [

26], differential evolution (DE) [

27], manta ray foraging optimization (MRFO) [

19], hunger games search (HGS) [

28], and its hybrid version [

28] have been applied to optimize PID or FOPID parameters for maglev systems, leading to significant performance improvements.

Across these clusters, two key observations emerge. First, while FOPID controllers exhibit enhanced robustness, most existing designs rely on linear or discontinuous nonlinear functions within the control law. These can cause abrupt control actions or chattering during large transients. Nonlinear variants (fuzzy or sigmoid PID) attempt to smooth control responses but often introduce asymmetrical mappings or high computational cost [

29]. There remains an absence of smooth, bounded, and differentiable nonlinear functions (such as the softsign activation function) integrated directly into the FOPID structure for maglev control. Second, the performance of optimization-based controllers largely depends on the algorithm’s exploration–exploitation balance. Conventional algorithms such as PSO, DE, or SCA may converge prematurely or show inconsistent results in high-dimensional spaces [

22,

30]. More recent adaptive optimizers, including the fungal growth optimizer (FGO), inspired by hyphal tip extension, chemotropism, and branching behaviors of fungi, demonstrate dynamic self-adaptation and have achieved superior convergence in engineering optimization tasks [

31]. However, no published study has reported the application of FGO for controller tuning in maglev or similar unstable nonlinear systems. Hence, two intertwined research gaps are evident: (1) the absence of a smoothly nonlinear fractional-order controller for maglev systems, and (2) the unexplored potential of FGO-based tuning for robust control optimization.

To address these gaps, this study proposes a softsign fractional-order PID (Softsign-FOPID) controller, optimized via the FGO, for precise and robust control of the magnetic-ball suspension system. The softsign function provides a bounded and continuously differentiable nonlinearity that smooths control signals while preserving steady-state accuracy. The FGO algorithm ensures adaptive and consistent convergence by balancing global exploration and local exploitation. The main contributions are as follows considering the above discussion:

A first-of-its-kind controller architecture, embedding a softsign nonlinear function within a FOPID structure for Maglev systems.

Integration of the fungal growth optimizer (FGO) for controller tuning—its first reported use in control-system optimization.

Formulation of a composite objective function that penalizes both overshoot and integrated absolute error (IAE), ensuring a trade-off between transient and steady-state behavior.

A comprehensive comparative analysis against contemporary optimizers (GCRA, CFOA, RIME, AHA) and leading literature benchmarks demonstrating superior performance and robustness under fluctuating reference inputs, actuator saturation, external disturbances, and parameter uncertainties.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 explains the FGO algorithm.

Section 3 models the magnetic-ball suspension system.

Section 4 details the Softsign-FOPID controller design and objective-function formulation.

Section 5 presents optimization results and comparative analyses.

Section 6 evaluates robustness under non-ideal conditions.

Section 7 concludes the work and outlines future research perspectives.

2. Fungal Growth Optimizer

Fungal growth optimizer (FGO) [

31] is a recent metaheuristic algorithm inspired by the adaptive behaviors of fungi in nature, particularly hyphal tip extension, chemotropic movement, and branching mechanisms. These behaviors allow fungi to explore and exploit their environment efficiently, making FGO a powerful framework for solving complex, nonlinear optimization problems. FGO starts by initializing a population of agents called hyphae, each representing a candidate solution. The initial positions of these hyphae are randomly generated across the defined search space using Equation (1) where

.

Here, and are the lower and upper bounds of the search space, and is a uniformly distributed random vector. Each hypha then undergoes an iterative growth process. At each iteration , a hypha may either continue growth along its tip, branch laterally, or initiate a new germination depending on its relative performance and a set of stochastic rules.

Exploration in FGO is modeled through directional extension of hyphae toward diverse regions of the search space. The extension is driven by a growth rate

computed by Equation (2):

where

denotes the fitness of the

-th solution,

is a uniformly distributed random number in

and

is the maximum number of iterations. The new direction

is defined by the difference between two randomly selected solution vectors:

Then, the position is updated as in Equation (4).

To enhance exploration selectively in dimensions, a probabilistic filtering mechanism updates only certain components of the position vector (Equation (5)):

where

is the random number for the

dimension and

is a threshold value.

In the FGO, exploitation is modeled based on the chemotropism behavior of fungal hyphae, which enables directional growth toward favorable nutrient sources. This is mathematically expressed by Equation (6):

where

is the current solution,

is a randomly selected solution from the population,

is the global best solution found so far,

,

,

are random values generated from a uniform distribution,

, is a direction control coefficient randomly chosen,

is a predefined threshold constant and

is evaluated as in Equation (7).

This operator balances random directional movement (first term) with greedy attraction to the global best (second term), but the latter is only activated when

, providing conditional exploitation that enhances adaptability and avoids premature convergence. To adjust the aggressiveness of exploitation, an adaptive step size

is defined in Equation (8):

where

and

are random numbers between 0 and 1. The position update rule incorporates both directional movement and a local perturbation vector

where

is a fixed perturbation probability threshold and

is a random number.

and

are two distinct solutions. A greedy selection strategy is adopted as given in Equation (10) where

and

,

are random scaling factors.

To balance exploration and exploitation adaptively, each individual is assigned an exploration probability given in Equation (11):

where

and

denote the best and worst fitness values in the current population,

is a small constant to avoid division by zero. An adaptive factor controlling exploration pressure is defined by Equation (12):

where

is a constant controlling minimum exploitation pressure.

In the later stage of fungal evolution, when the growth of a hypha becomes unstable or encounters stressors such as nutrient deficiency or external environmental perturbations, the hypha may branch or germinate spores to enhance exploration and adaptation. To begin with, two directional growth patterns are considered for generating new hyphae. The first pattern is based on the difference between two randomly selected individuals from the population (Equation (13)).

The direction of the new hypha is then determined by combining these two patterns based on a uniformly distributed random number

.

To account for growth dynamics under varying environmental conditions, the lateral growth rate is defined as in Equation (15):

where

denotes the fitness value of the

-th individual. The Iverson bracket

equals 1 if the condition is true, and 0 otherwise. Using this dynamic growth rate, the updated lateral branching position for each dimension

is formulated as:

where

is a uniformly distributed random value for the

-th dimension. The model also introduces a spore germination mechanism to increase solution diversity. A new hypha is generated using the absolute difference between the mean of three randomly selected individuals and the current solution. Let

,

,

denote randomly chosen individuals; then the spore germination update rule is given by Equation (17).

Here,

is a randomly selected sign that dictates the direction of spore movement, and is the exponential growth rate parameter. Finally, the trade-off between branching and spore germination is determined stochastically. With 50% probability, one of the two perturbation strategies is applied via Equation (18).

The pseudocode in

Figure 1 provides the working principle of FGO explained above.

3. Mathematical Model of the Magnetic Ball Suspension System

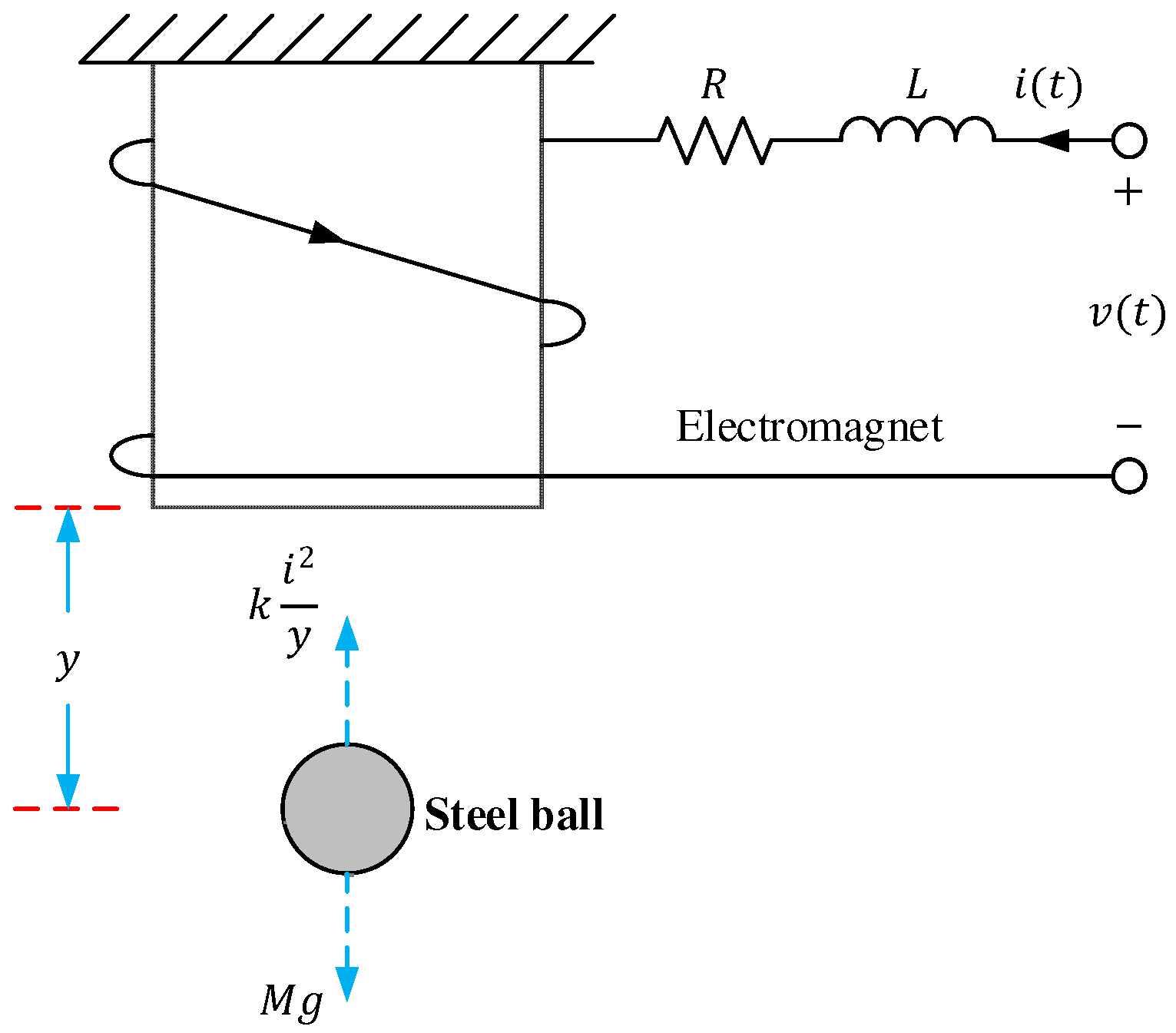

The magnetic ball suspension system, schematically illustrated in

Figure 2, is a classical nonlinear and open-loop-unstable benchmark plant widely used to validate advanced control strategies [

19,

32,

33,

34]. The configuration consists of an electromagnet, a steel ball, and associated circuitry containing a coil of resistance

and inductance

. The system operates by regulating the electromagnetic force that counteracts the gravitational pull acting on the steel ball, thereby maintaining a desired levitation height

.

When a control voltage

is applied to the coil, the resulting current

produces a magnetic flux that generates an upward electromagnetic force proportional to

, where

is the electromagnetic constant depending on the coil geometry and magnetic permeability. The gravitational force

acts in the opposite direction, pulling the ball downward. Consequently, the vertical motion of the ball is governed by Newton’s second law, yielding the nonlinear equation of motion given in Equation (19).

The electrical dynamics of the coil circuit are simultaneously described by the first-order differential equation:

Equations (19) and (20) together form a nonlinear electromechanical system, coupling current and position variables. At steady state, when the ball is suspended at an equilibrium distance

and the current is

, the electromagnetic and gravitational forces balance, i.e.,

. To derive a linearized model suitable for controller design, small perturbations are defined around the equilibrium point:

Substituting (21) into (19) and (20) and neglecting higher-order terms yields the linearized state-space model that captures the local dynamics near equilibrium. Taking the Laplace transform and expressing the system in the transfer-function form gives the open-loop plant representation:

where the parameters are defined as

,

,

. The poles

form a pair of real roots of opposite sign, representing the inherent instability of the levitation system since one of them lies in the right-half of the

-plane [

19,

32,

33,

34]. Using the experimentally established parameter values [

19,

32,

33,

34]—

Ω,

H,

kg,

m/s

2,

kg·m

2/A

2·s

2 and

m—the numerical substitution yields the linearized transfer function of the magnetic ball suspension plant, which can be written explicitly as given in Equation (23).

This third-order transfer function clearly demonstrates the unstable nature of the system due to the positive pole. Therefore, without feedback control, even small deviations from the equilibrium cause the ball to diverge rapidly from its suspended position. The derived model serves as the foundation for developing and tuning advanced controllers such as the FGO-optimized softsign-FOPID proposed in this work. It provides the dynamic representation required for simulating control performance, designing objective functions, and performing stability and robustness analyses.

4. Proposed Control Method

4.1. Theoretical Background and Practical Implementation of FOPID Controllers

Fractional-order control has emerged as an effective extension of classical PID theory, offering enhanced robustness and dynamic flexibility for nonlinear systems [

35]. Unlike conventional PID controllers that employ first-order differentiation and integration, fractional-order PID (FOPID) models generalize these operators to real-valued orders

and

, which enable hereditary and memory characteristics to be reflected in the control action [

36]. The fractional differentiation operator is typically defined using the Grunwald–Letnikov (G–L) framework due to its suitability for numerical implementation [

37]. The

-order derivative of a function

over the interval

is expressed as:

where

,

is the time step, and the binomial term provides fractional-order weighting [

35]. This representation allows the controller to incorporate long-term past information of the error signal, strengthening noise resilience and disturbance rejection.

The transfer function of a FOPID controller is given as:

where

,

, and

denote the proportional, integral, and derivative gains, respectively, while

and

represent the fractional integral and derivative orders [

38,

39]. These additional degrees of freedom improve transient performance without compromising stability, especially for nonlinear and parameter-varying plants.

For real-time applications, rational approximation techniques such as discrete-time G–L implementations are widely adopted, enabling direct digital realization through finite impulse approximations [

35]. This structure has already demonstrated strong robustness against dynamic uncertainties and disturbances in nonlinear power electronics and electromechanical systems, confirming its practicality and effectiveness.

In this study, the FOPID block receives the softened nonlinear error generated by the softsign function, and its contribution is tuned automatically using the FGO. The selection of FOPID is justified by its superior disturbance rejection capability and enhanced transient shaping performance in systems characterized by strong nonlinearities such as magnetic levitation platforms.

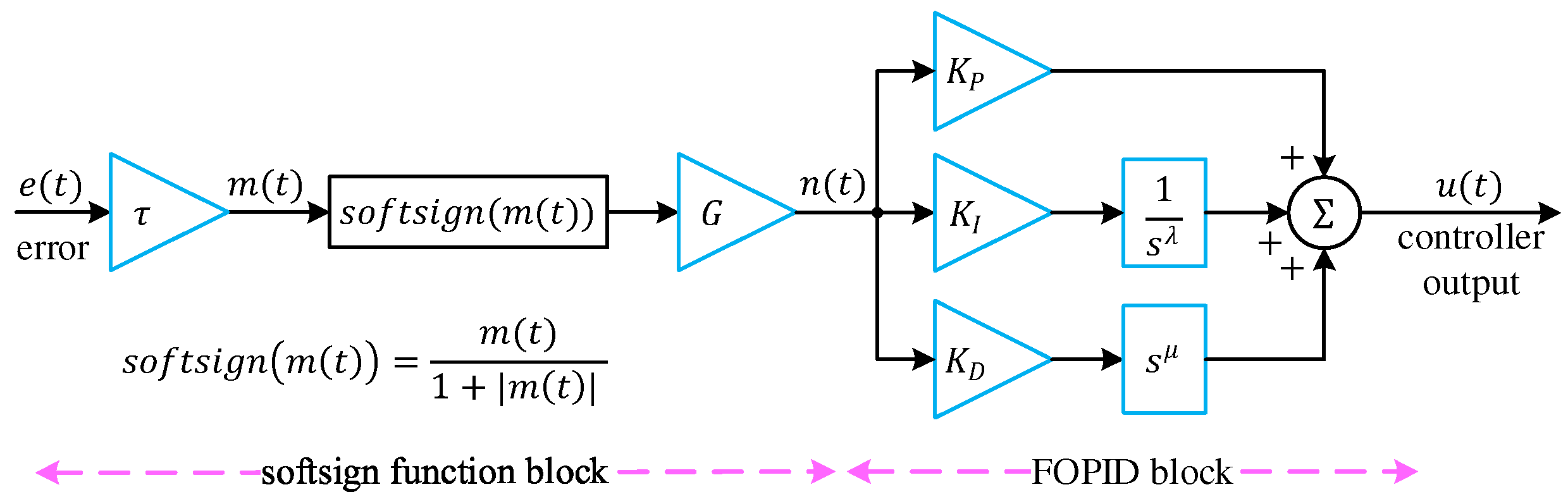

4.2. Novel Softsign Function-Based FOPID Controller

The proposed control structure integrates a nonlinear softsign activation with a FOPID framework to achieve a smooth and adaptive control action for the magnetic ball suspension system. The complete architecture is illustrated in

Figure 3, where the controller receives the position error signal

and produces the control output

through a sequence of nonlinear and fractional operations.

The transfer function of the FOPID controller has already been defined in the previous subsection by Equation (25). This generalized structure provides a wider tuning range than a conventional PID by allowing non-integer exponents that shape the frequency response more flexibly and improve robustness to parameter variations. To introduce nonlinear adaptability, the FOPID stage is preceded by a softsign function [

40] block. The softsign nonlinearity is mathematically expressed as in Equation (26):

which smoothly bounds large input magnitudes within the interval

. Unlike discontinuous functions, the softsign mapping preserves differentiability, ensuring continuous control action without chattering or abrupt saturation. As shown in

Figure 3, the input error

is first scaled by a gain

to produce an intermediate signal

. This signal is then passed through the softsign nonlinearity, yielding expression in Equation (27).

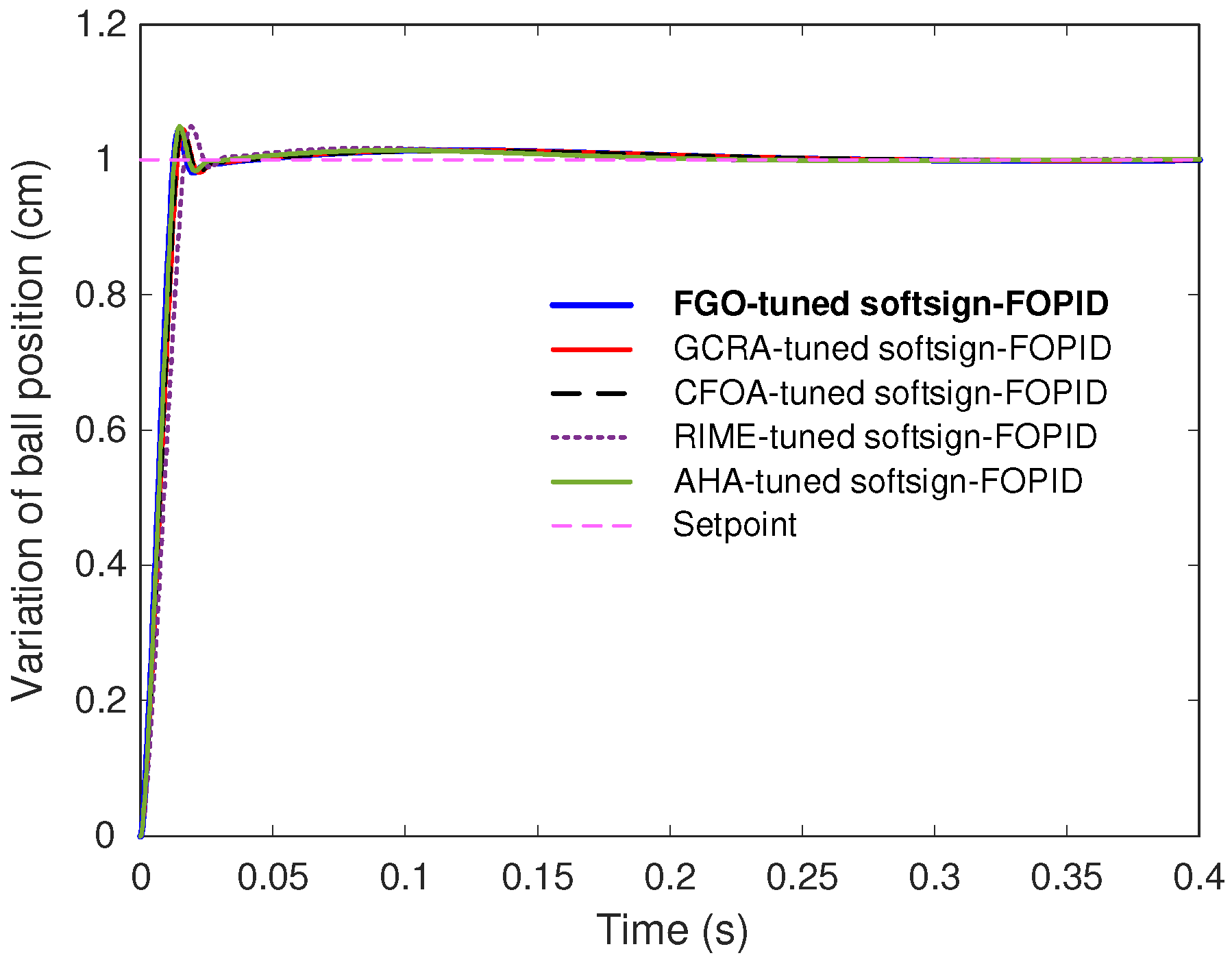

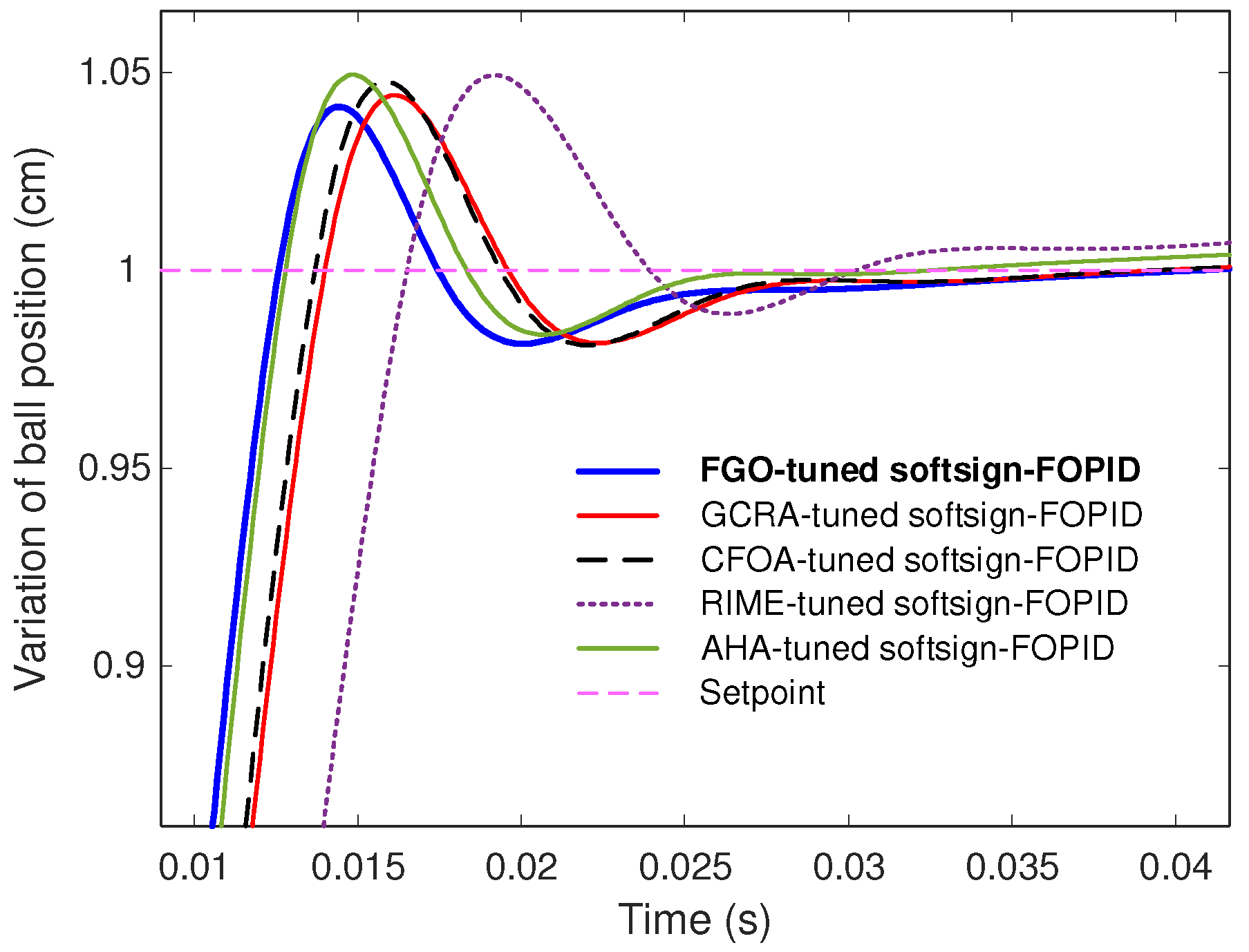

Here, is an additional gain that adjusts the amplitude of the nonlinear output. The resulting signal therefore represents a soft-bounded, gain-scaled version of the error, ensuring that the subsequent control stages receive a moderated input even under large tracking deviations. The signal is then fed into the FOPID block, which consists of three parallel paths corresponding to the proportional, integral, and derivative terms. These branches are weighted by , , and , respectively. The integral branch employs the fractional operator , while the derivative branch uses . The outputs of all three branches are summed at the node to form the overall controller output . This cascaded design combines the benefits of both nonlinear and fractional-order control. The softsign mapping enhances stability and prevents excessive control effort, while the fractional-order dynamics allow fine control of transient and steady-state performance. Consequently, the softsign-FOPID controller achieves superior smoothness, adaptability, and robustness compared with conventional PID-type controllers.

4.3. Discussion on the Potential and Limitations of the Softsign Implementation

The introduction of the softsign function enhances the control performance by smoothly reducing the impact of large error magnitudes and preventing abrupt variations in the control action. This characteristic is particularly advantageous for the magnetic ball suspension system, where rapid error deviations may otherwise induce actuator saturation and excessive transient oscillations. The nonlinear mapping also improves the damping properties of the closed-loop dynamics by moderating the proportional and derivative responses during aggressive transients. As a result, a more stable and energy-efficient behavior is achieved during large tracking deviations and sudden reference changes.

Nevertheless, the effectiveness of the softsign activation remains dependent on appropriate coordination with the fractional orders and gain parameters of the FOPID controller. An excessively strong softsign scaling could reduce the control effort to the extent that responsiveness deteriorates, especially when rapid corrective action is required. Additionally, since the nonlinear shaping modifies the actual error delivered to the fractional branches, the selection of tuning bounds must ensure that the fractional-order dynamics preserve stability and steady-state precision. Despite these considerations, the results demonstrated in

Section 5 and

Section 6 confirm that, when the softsign and FOPID parameters are jointly optimized by FGO, the nonlinear enhancement yields significant improvements in robustness, transient smoothness, and overshoot suppression without compromising steady-state accuracy.

4.4. Proposed Objective Function

To determine the optimal parameters of the proposed softsign-FOPID controller, a composite objective function (OF) has been formulated. The objective function integrates both transient and steady-state performance indices to ensure a well-balanced dynamic response of the magnetic ball suspension system. It is mathematically defined as minimizing the expression in Equation (28).

In this expression, represents the total simulation time, denotes the instantaneous tracking error between the reference position and the actual ball position , and is the peak value of the ball position response. The first term, , penalizes excessive overshoot by driving close to unity, whereas the second term minimizes the accumulated absolute error throughout the simulation. By combining these two criteria, the objective function simultaneously enforces fast convergence and minimal steady-state deviation. A stability factor of has been adopted to assign higher importance to the integral performance index, ensuring smoother error attenuation while maintaining control stability. The total simulation period is fixed at , which is sufficient to capture the complete transient and settling behavior of the system. During the optimization process, the parameters of the softsign-FOPID controller are constrained within predefined practical ranges to preserve stability and realizability.

The corresponding bounds are specified as , , , , , and . Here, , , and correspond to the proportional, integral, and derivative gains of the FOPID controller, while and denote the fractional integral and derivative orders. The parameters and belong to the softsign function block and govern the scaling and amplitude of the nonlinear activation, respectively. These constraints define the feasible search space for the optimization algorithm and ensure that the resulting controller operates within stable and implementable limits. The formulated objective function thus provides a comprehensive performance measure for tuning the softsign-FOPID controller using the fungal growth optimizer described in the subsequent section.

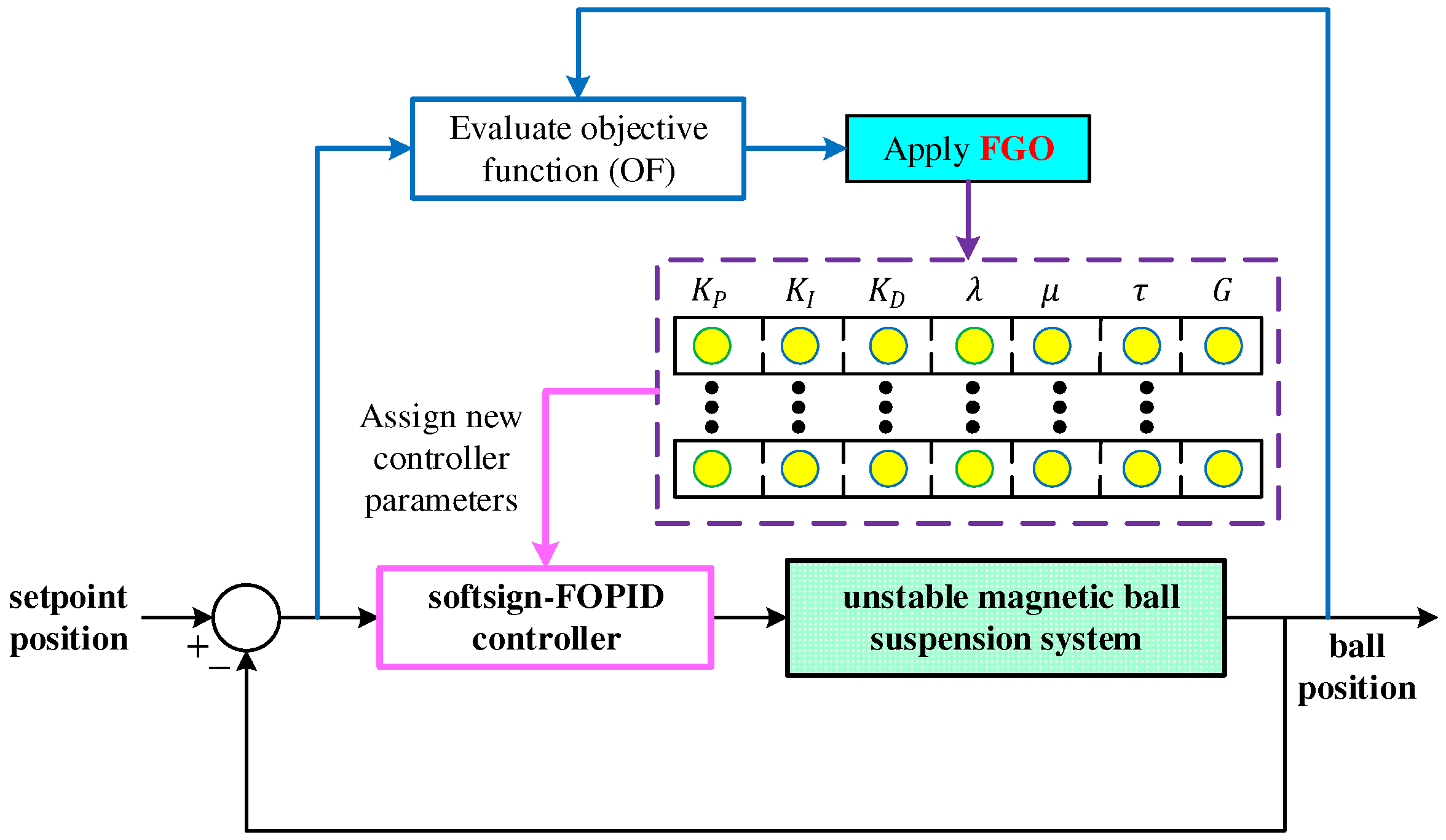

4.5. Implementation of the Proposed Method to the Magnetic Ball Suspension System

The integration of the FGO with the softsign-FOPID controller for the magnetic ball suspension system is schematically illustrated in

Figure 4. The diagram represents the closed-loop optimization and control process, in which the controller parameters are iteratively tuned through the optimization routine until the best performance is achieved according to the defined objective function. In this implementation, the setpoint position is first compared with the measured ball position, producing the instantaneous tracking error signal. This error is then processed by the softsign-FOPID controller, whose structure has been previously described. The controller generates the control effort that drives the electromagnet to stabilize the levitated ball around its desired position.

The optimization process operates concurrently with the control loop. Initially, FGO generates a population of candidate parameter sets for the seven controller variables Each candidate solution corresponds to a different tuning configuration of the softsign-FOPID controller. For every candidate, the control system is simulated, and the resulting transient response is evaluated through the objective function defined in Equation (28). The objective function computes the performance index by using the system output and the instantaneous error. The resulting objective value is then passed to the FGO, where the optimization algorithm updates the controller parameters based on the fungal growth mechanism. The newly generated parameter set is reassigned to the controller, and the process repeats until the termination criterion is met. Through this iterative tuning procedure, the FGO effectively explores the multidimensional parameter space and identifies the optimal combination of controller gains and fractional orders that minimize the objective function. The interaction between the optimizer and the control loop ensures that the system’s transient and steady-state characteristics such as overshoot, rise time, and steady-state error—are simultaneously improved.

6. Evaluation of Control Effectiveness Under Practical Non-Idealities

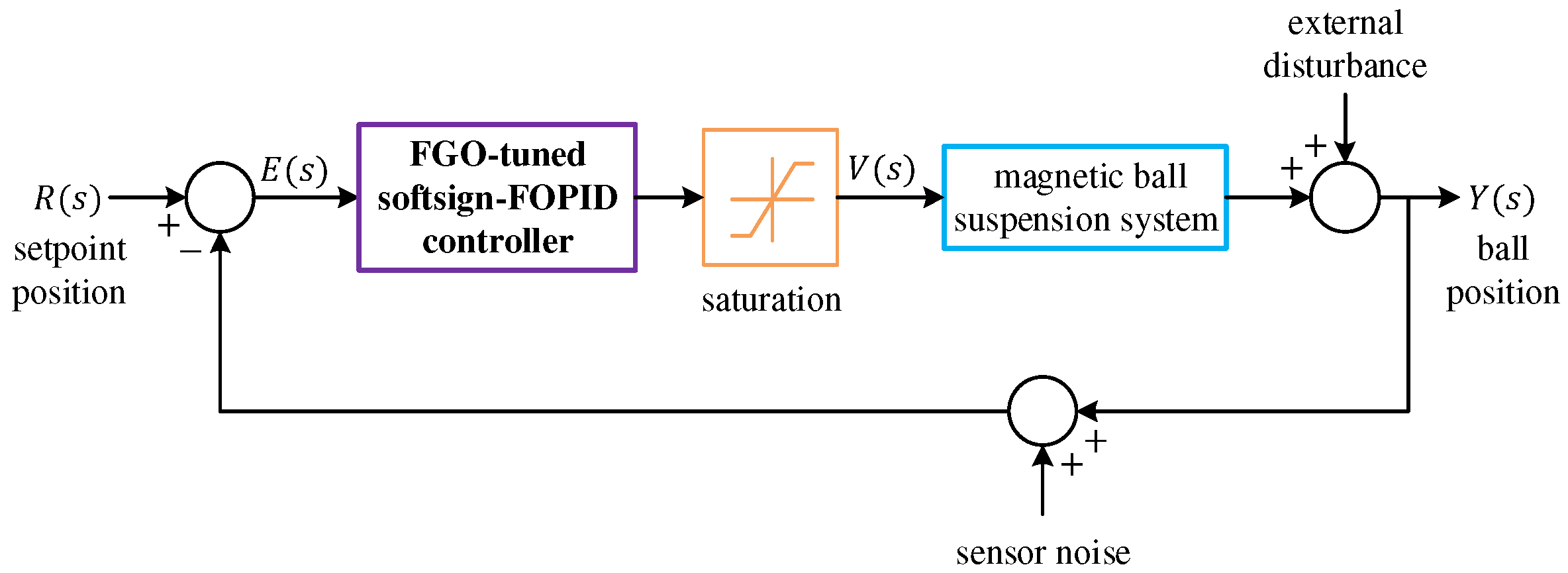

To validate the robustness and real-world applicability of the proposed control framework, the FGO-tuned softsign-FOPID controller was further tested under various practical non-ideal conditions, including actuator saturation, sensor noise, and external disturbances. The simulation setup used for this analysis is illustrated in

Figure 10, which depicts the complete closed-loop configuration employed to assess the controller’s resilience to these non-idealities. As shown in the figure, the setpoint position, denoted as

, represents the desired vertical position of the levitated ball. The difference between the reference input and the measured output

produces the error signal,

, which is processed by the FGO-tuned softsign-FOPID controller. This controller dynamically generates the control action based on the nonlinear fractional-order structure optimized through the fungal growth algorithm, as previously discussed in

Section 4 and

Section 5.

The resulting control signal,

, passes through a saturation block that emulates the physical voltage or current limitations of the electromagnetic actuator. This nonlinearity ensures that the simulated control input does not exceed realistic operational bounds, thereby reflecting the behavior of the actual magnetic suspension hardware. The magnetic ball suspension system receives the saturated control input and produces the actual ball position response,

. To represent the unpredictable conditions encountered in real environments, two major disturbances are introduced into the feedback loop: (1) external disturbance, acting directly on the magnetic actuator output or ball position, simulates external vibrations or air currents that can momentarily alter the levitation stability and (2) sensor noise, added to the feedback measurement path, models the random fluctuations and measurement inaccuracies that typically occur in practical sensing hardware. These perturbations are depicted in

Figure 10 as additive inputs entering the feedback loop at different points; external disturbance applied at the actuator output and sensor noise added to the measured position signal. The combined influence of these effects provides a realistic and comprehensive test environment for evaluating the proposed control strategy.

Through this experimental setup, the effectiveness of the FGO-optimized softsign-FOPID controller can be analyzed not only in terms of nominal system performance but also in its ability to maintain stability, precision, and smoothness under noisy, constrained, and disturbed conditions. The subsequent subsections present detailed analyses of the controller’s behavior under fluctuating reference positions, actuator saturation with external disturbance and sensor noise, and parametric uncertainties, demonstrating its robustness and practical reliability.

6.1. Under Fluctuating Reference Positions

To assess the tracking capability and adaptability of the proposed controller, the FGO-tuned softsign-FOPID was evaluated under time-varying reference inputs. Unlike conventional step commands, the reference trajectory in this test consists of continuously changing and randomly fluctuating position signals to emulate real-world operational scenarios where the target levitation height varies dynamically. The system’s corresponding response is illustrated in

Figure 11. As shown in the figure, the blue curve represents the actual variation in the ball position governed by the FGO-optimized softsign-FOPID controller, while the red dashed curve denotes the randomly fluctuating reference input. Throughout the entire 17 s simulation period, the controlled response accurately follows the reference signal with negligible phase lag and minimal amplitude deviation. This close overlap between the reference and response trajectories demonstrates the strong tracking precision and adaptive nature of the proposed controller.

Even during abrupt reference changes and high-frequency variations, the control signal maintains smoothness without noticeable overshoot or oscillatory divergence. The fractional-order dynamics, combined with the softsign nonlinear activation, enable the controller to dynamically modulate its corrective effort according to the instantaneous rate of change of the input signal. Consequently, the magnetic levitation system remains stable and responsive despite rapid target fluctuations. The results clearly indicate that the proposed FGO-tuned softsign-FOPID controller possesses superior adaptability and robustness in tracking variable reference positions. Its effective balance between fast transient response and stability ensures continuous levitation control performance under non-stationary operating conditions which is an essential requirement for practical magnetic suspension and precision positioning applications.

6.2. Under Actuator Saturation, External Disturbance, and Sensor Noise

In addition to fluctuating reference tracking, the robustness of the FGO-tuned softsign-FOPID controller was evaluated under multiple real-world non-idealities, namely actuator saturation, external disturbances, and sensor noise. This analysis was conducted to verify the controller’s ability to maintain accurate levitation performance when exposed to practical constraints and unpredictable external effects. The corresponding results are illustrated in

Figure 12. In this simulation, the setpoint (depicted by the red dashed line) represents the desired equilibrium position of the magnetic ball, while the blue curve shows the actual system response governed by the proposed controller. Two main disturbance types were introduced during operation: (1) external disturbances were applied directly to the system output to simulate sudden perturbations such as air gusts or electromagnetic fluctuations and (2) sensor noise was added to the feedback loop to emulate high-frequency measurement noise originating from practical sensing hardware. Furthermore, a saturation nonlinearity was incorporated into the actuator model to restrict the control signal amplitude, ensuring that the simulated system adhered to realistic current and voltage limitations of the electromagnetic coil.

As observed in

Figure 12, the system maintained excellent stability and precise position control despite these simultaneous non-ideal conditions. When external disturbances occurred, small transient spikes appeared momentarily in the ball position, but the controller rapidly suppressed them and restored the system to its equilibrium within milliseconds. The smooth response indicates that the proposed control method effectively compensated for the actuator saturation and disturbance effects without introducing sustained oscillations or offset. The presence of sensor noise had negligible influence on the output trajectory, demonstrating the controller’s strong filtering capability. This robustness can be attributed to the synergistic structure of the softsign-FOPID controller, where the nonlinear softsign function limits abrupt control variations while the fractional-order dynamics provide flexible damping and memory properties. The optimized parameters obtained via the fungal growth optimizer (FGO) further ensure balanced adaptability between responsiveness and stability under uncertain conditions. In summary, the performance analysis presented in

Figure 12 confirms that the FGO-tuned softsign-FOPID controller exhibits outstanding robustness and resilience against actuator limitations, environmental disturbances, and measurement noise. These results validate its suitability for real-time magnetic levitation control, where precision and reliability must be preserved even under practical system imperfections.

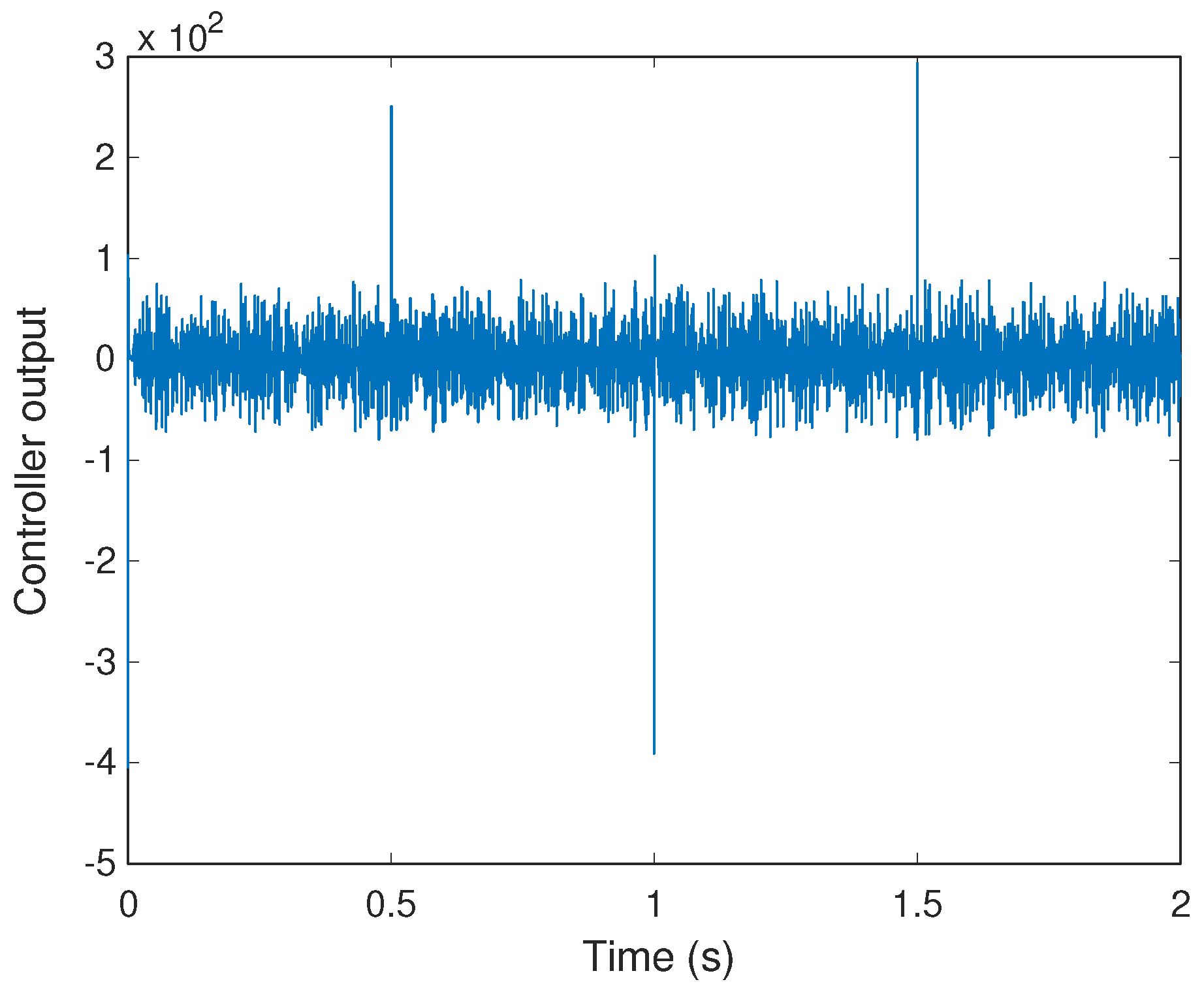

To provide a comprehensive evaluation of the derivative action behavior, the controller output of the FGO-tuned softsign-FOPID structure has been visualized under noisy measurement conditions and disturbance events. The resulting transient output signal is depicted in

Figure 13. The recorded control effort remains bounded throughout operation, confirming that the nonlinear softsign activation effectively moderates high-magnitude variations. Although isolated peaks occur during abrupt disturbance changes, such transient deviations diminish rapidly and do not evolve into sustained high-frequency oscillations. This desirable behavior is attributed to the first-order derivative filtering embedded in the FOPID structure through the FOMCON toolbox [

46] implementation, where a derivative filter time constant of 0.0001 s, an approximation order of 5, and a frequency range of

were selected. This filtering approach limits noise amplification and prevents excessive actuator activity while preserving the beneficial responsiveness of the derivative term. These findings confirm the practical viability of the proposed control strategy, achieving robust stabilization without compromising actuator health or long-term reliability.

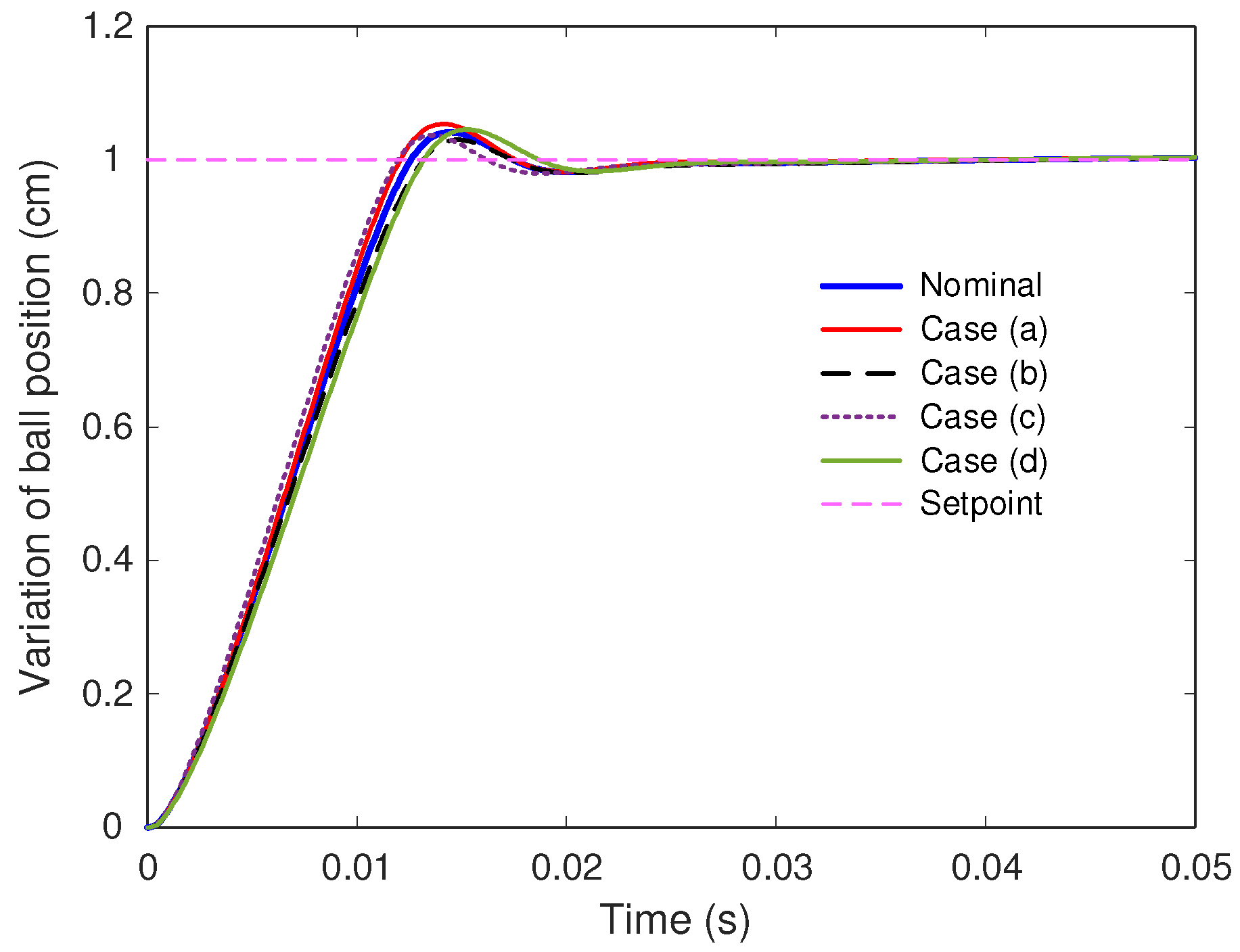

6.3. Robustness Characterization Under Parametric Uncertainties

To further validate the stability and reliability of the proposed control strategy, a robustness analysis was conducted by introducing parametric uncertainties into the magnetic ball suspension system model. This analysis examined the controller’s ability to maintain performance when key system parameters deviated from their nominal values, simulating manufacturing tolerances, environmental variations, or aging effects in the physical components. The parameter configurations adopted for this investigation are summarized in

Table 6, while the corresponding system responses are illustrated in

Figure 14. In this study, the coil resistance (R) and inductance (L) were selected as the uncertain parameters, as they directly influence the electromagnetic force generation and dynamic response of the levitation system. Four perturbed scenarios were defined around the nominal configuration as shown in

Table 6.

The resulting step responses for these cases are shown in

Figure 14, along with the nominal system behavior for reference. As illustrated in the figure, all perturbed cases closely follow the nominal trajectory, with only minor deviations observed during the transient phase. The FGO-tuned softsign-FOPID controller successfully maintained system stability and ensured consistent dynamic performance across all uncertainty scenarios. Despite variations in the electromagnetic parameters, the overshoot, settling time, and steady-state accuracy remained virtually unchanged, highlighting the robustness of the control design. Specifically, slight increases or decreases in resistance and inductance caused negligible shifts in the rise and peak times but did not lead to oscillations or divergence. The softsign nonlinear mapping contributed to this robustness by preventing excessive control effort under altered dynamic conditions, while the fractional-order elements provided inherent adaptability through memory-based error correction. This combination ensured stable levitation control even when the system’s electrical characteristics were significantly perturbed. Overall, the robustness characterization presented in

Figure 14 confirms that the FGO-optimized softsign-FOPID controller maintains excellent performance and resilience under parameter uncertainties. The controller’s adaptive structure and optimally tuned fractional orders enable it to preserve control precision and transient quality without requiring retuning, thereby demonstrating strong suitability for real-world applications of magnetic levitation systems operating under uncertain or variable physical conditions.

7. Conclusions

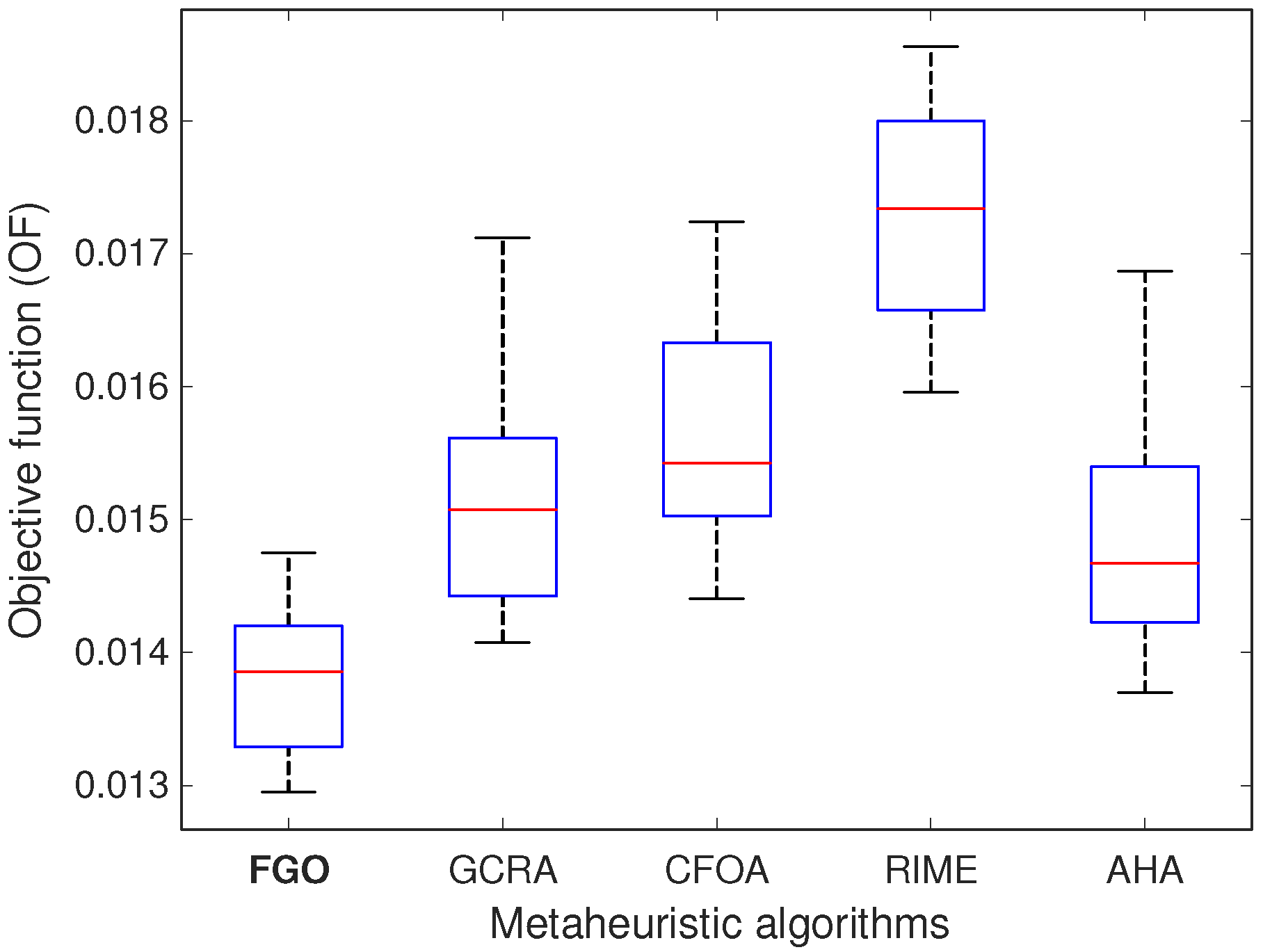

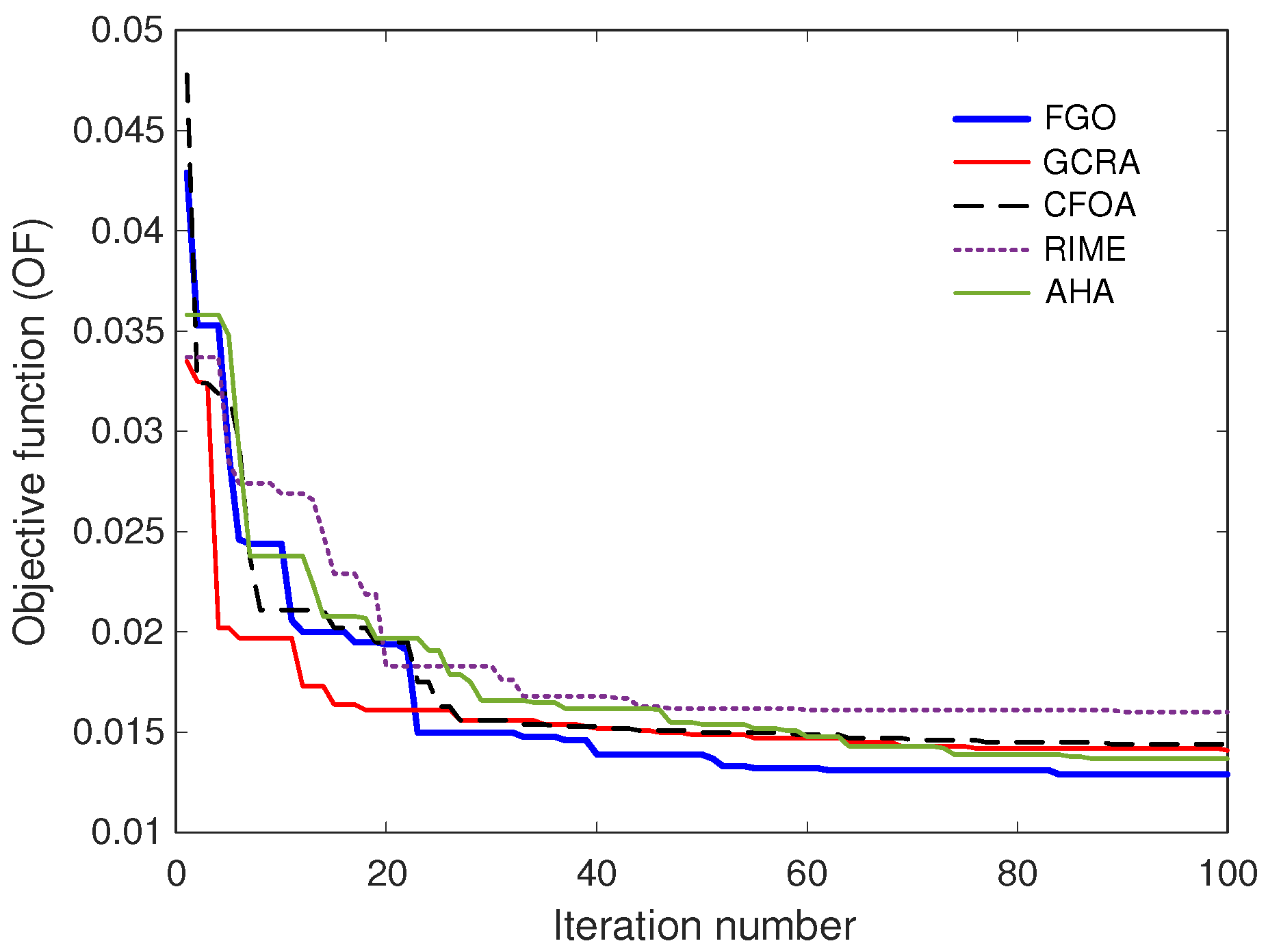

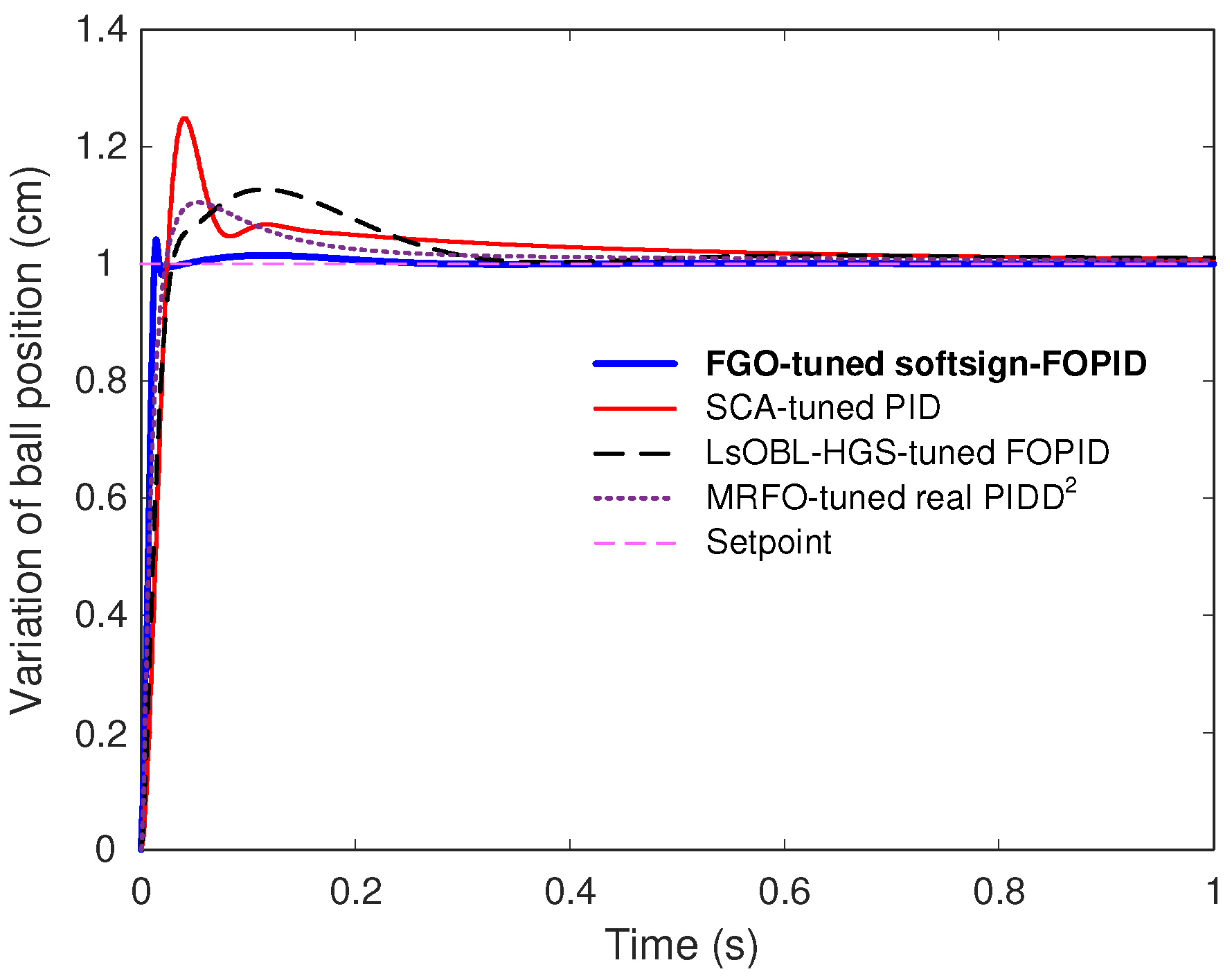

In this study, a novel softsign-FOPID controller was proposed and optimized using the recently developed FGO to achieve high-precision and robust control of an unstable magnetic ball suspension system. The research successfully integrated nonlinear control, fractional calculus, and metaheuristic optimization into a unified framework capable of handling the system’s inherent instability, nonlinearities, and sensitivity to parameter variations. The proposed controller architecture combined the fractional-order PID structure with a softsign nonlinear activation, which introduced a smooth, bounded control effort while maintaining fast dynamic adaptability. This structure effectively mitigated overshoot and chattering issues typically associated with nonlinear controllers and enhanced damping during transient responses. The FGO algorithm was employed to determine the optimal controller parameters by minimizing a composite objective function (OF) that simultaneously considered overshoot suppression and cumulative error minimization. The optimizer’s adaptive balance between exploration and exploitation enabled rapid convergence toward globally optimal solutions with high consistency across multiple independent runs. Comprehensive comparative analyses were carried out against four advanced metaheuristic algorithms (GCRA, CFOA, RIME, and AHA) under identical optimization settings. The statistical results and boxplot comparisons demonstrated that FGO consistently achieved the lowest mean and variance of the objective function, as confirmed by Wilcoxon rank-sum tests with statistically significant improvements (p < 0.05). The convergence characteristics further validated FGO’s superior efficiency and stability during parameter tuning. Time-domain performance assessments indicated that the FGO-tuned softsign-FOPID controller provided the fastest rise time, shortest settling time, and lowest overshoot, outperforming all compared methods. When benchmarked against the best previously reported controllers (namely the SCA-tuned PID, LsOBL-HGS-tuned FOPID, and MRFO-tuned real PIDD2), the proposed controller exhibited superior transient and steady-state performance, confirming its advancement beyond the state of the art in magnetic levitation control. The robustness and practical viability of the proposed control strategy were further validated under several non-ideal operating conditions. The controller maintained excellent performance when subjected to fluctuating reference trajectories, actuator saturation, sensor noise, and external disturbances. Additionally, the robustness characterization under parameter uncertainties demonstrated that even with ±10% variations in resistance and inductance, the closed-loop system remained stable with negligible degradation in transient behavior. These results collectively confirm that the FGO-tuned softsign-FOPID controller possesses strong resilience, adaptability, and precision under realistic implementation constraints. In summary, the proposed FGO-based softsign-FOPID control framework provides a significant improvement over existing control and optimization strategies for magnetic suspension systems. Its design successfully combines the smooth nonlinearity of the softsign function with the memory and flexibility of fractional-order dynamics, optimized through an intelligent, nature-inspired algorithm. The resulting controller exhibits high control precision, rapid convergence, and remarkable robustness, making it a promising candidate for broader applications in nonlinear, unstable, and noise-sensitive systems.