Application of a Fractional Laplacian-Based Adaptive Progressive Denoising Method to Improve Ambient Noise Crosscorrelation Functions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Data

2.2. Method

2.2.1. Review of Seismic Interferometry

2.2.2. CCF Denoising with the FLAPD

2.2.3. Data Processing and Dispersion Curve Measurement

2.2.4. Direct Tomography for S-Wave Velocity

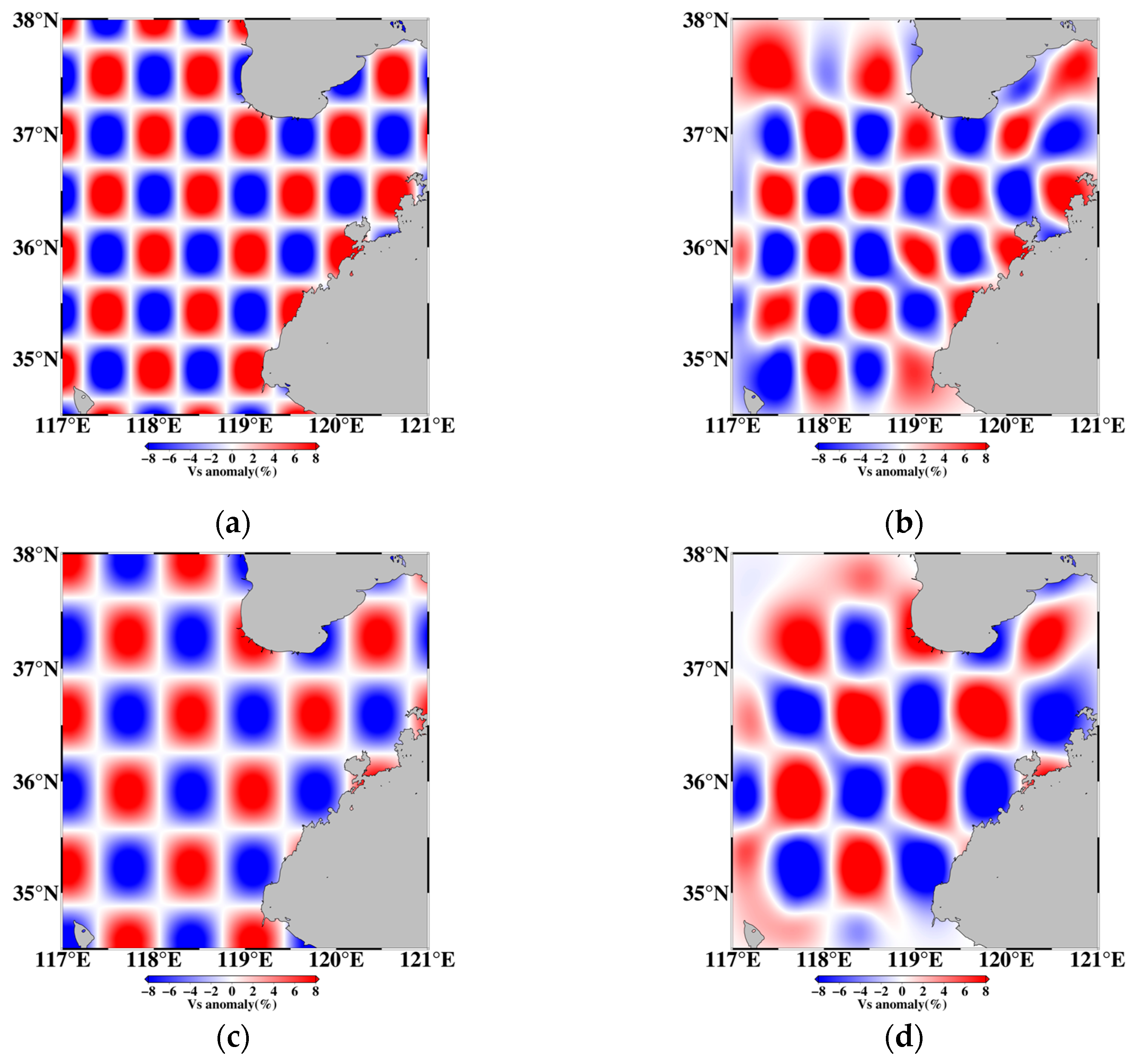

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Performance Advancement over Conventional Processing Workflows

4.2. Comparison with a Representative Multi-Scale Denoising Method

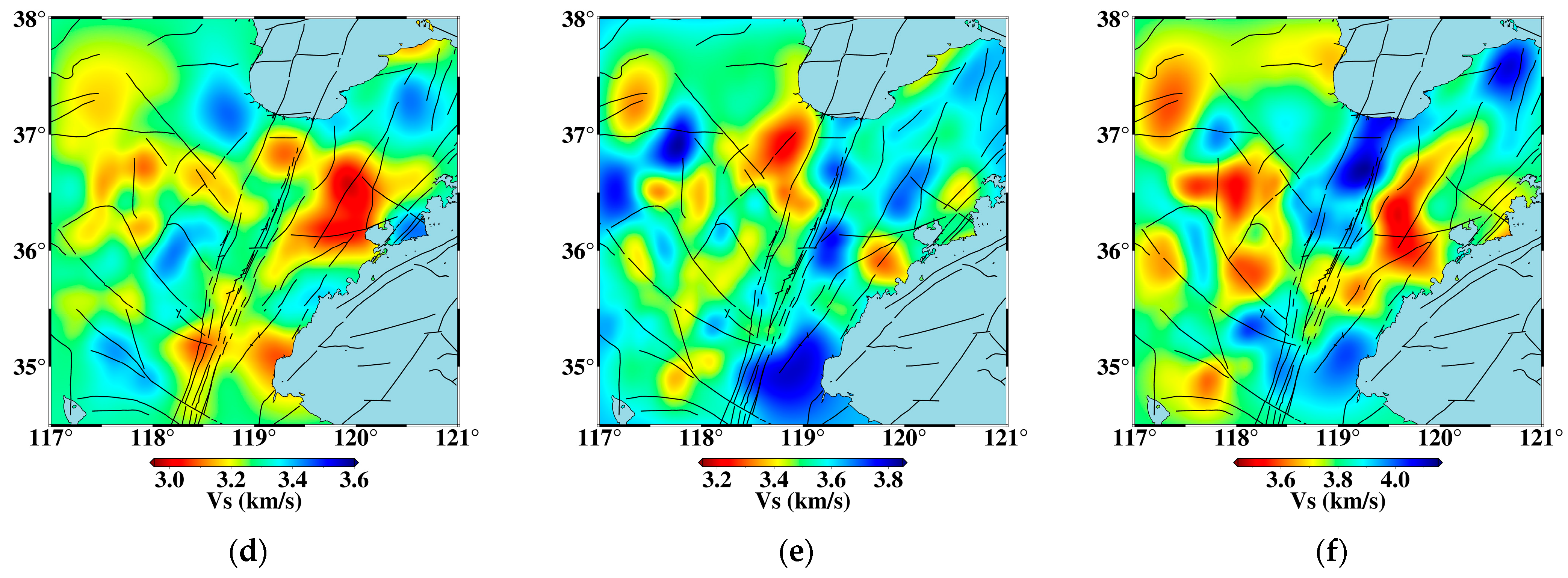

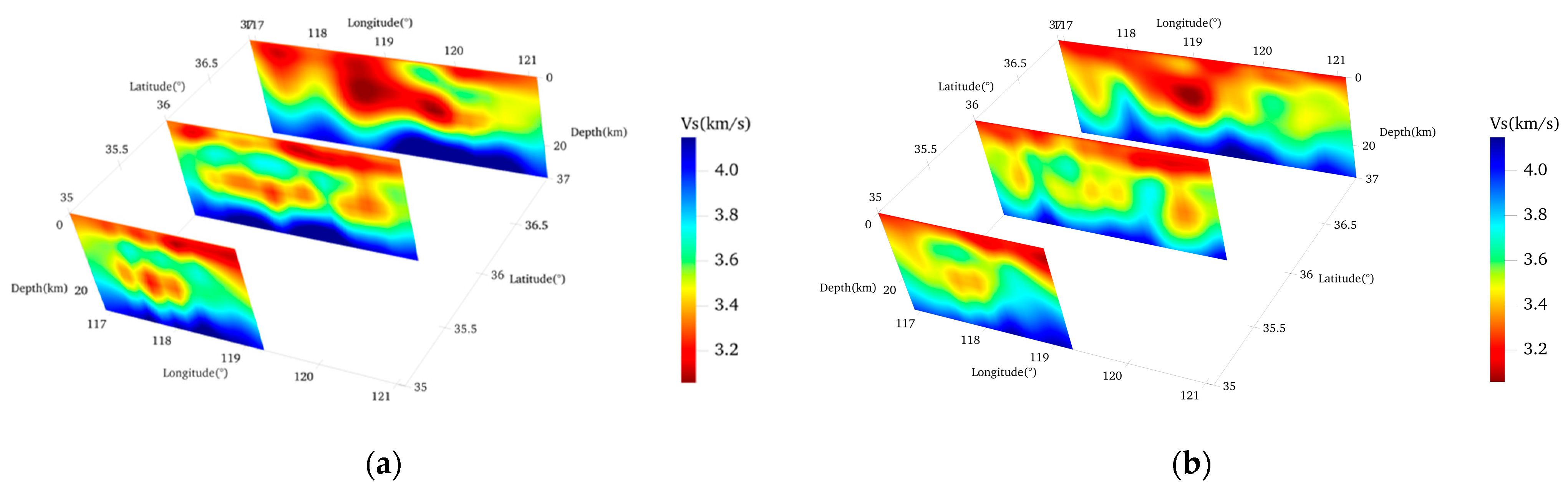

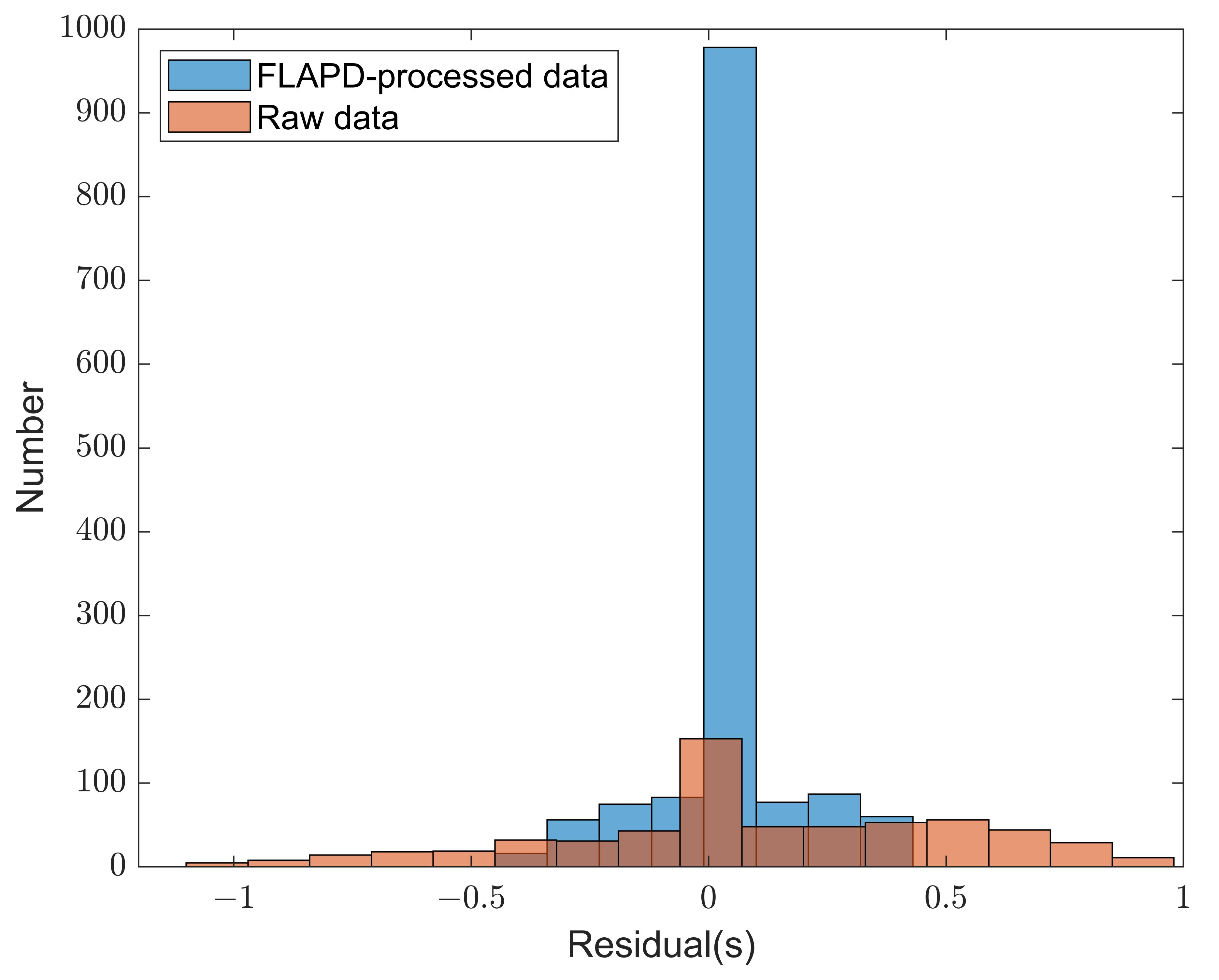

4.3. Comparative Analysis of Inversion Results Pre- and Post-FLAPD Processing

4.4. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The FLAPD method substantially improves the signal-to-noise ratio of CCFs. By integrating a fractional Laplacian mask for multi-scale noise variance estimation and a fractional bilateral kernel for dual-domain iterative denoising, the method effectively suppresses spurious noise while ensuring the high-fidelity preservation of coherent surface wave signals. Comparative analysis verifies its superiority over the Curvelet Transform method in balancing noise attenuation and signal integrity.

- (2)

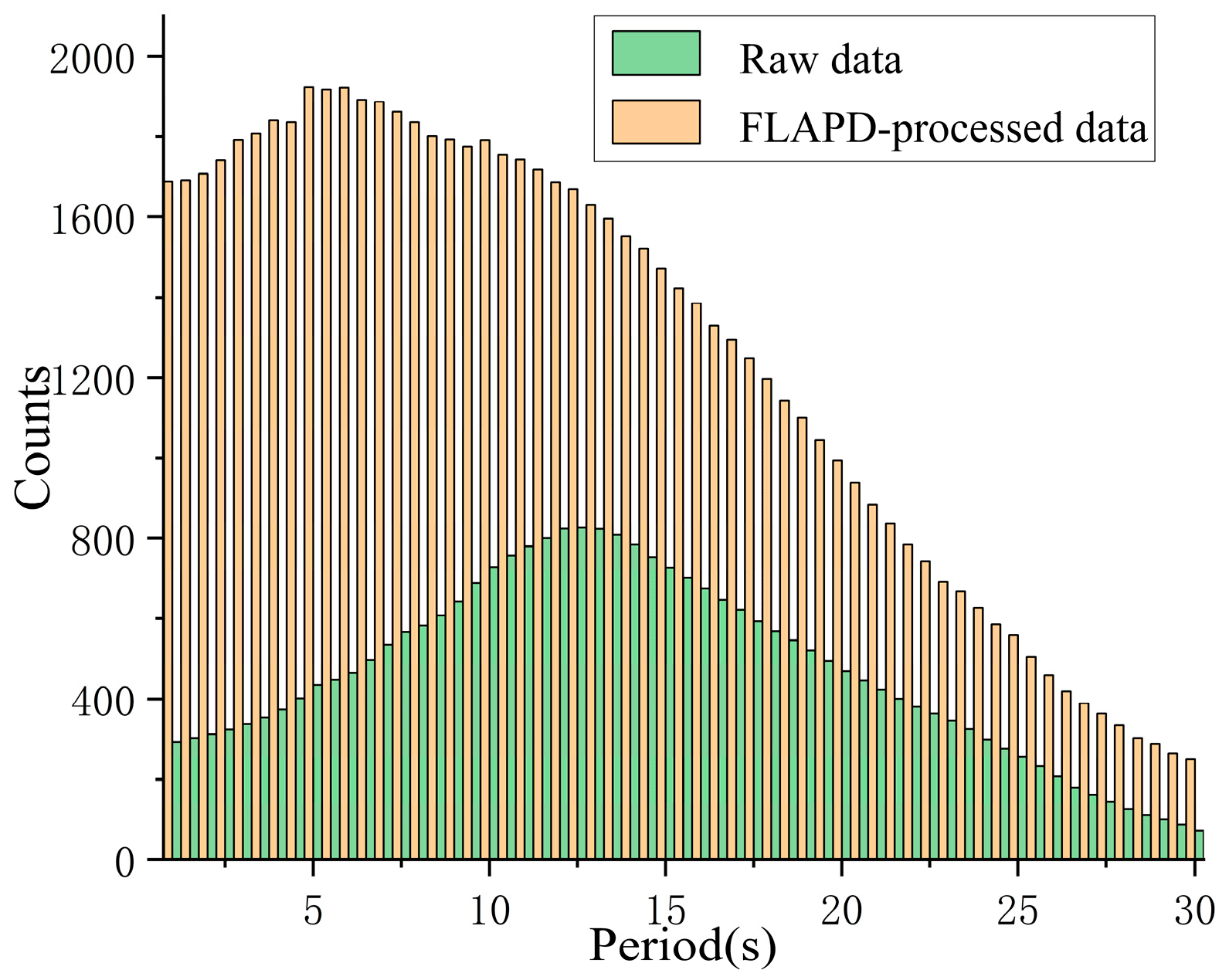

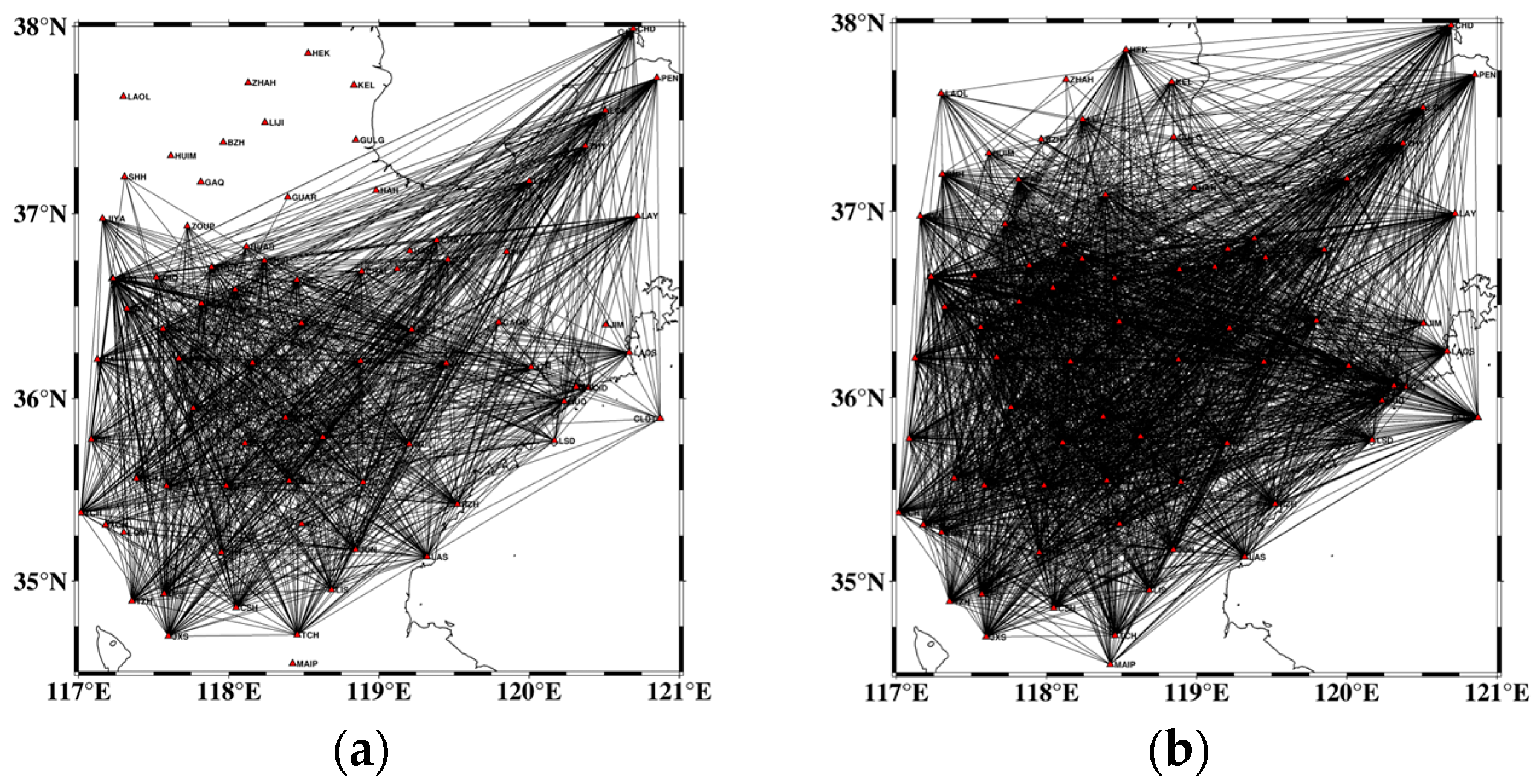

- This denoising process greatly enhances the reliability of surface wave analysis. EGFs extracted from FLAPD-processed CCFs show a significantly higher SNR. Consequently, the number of usable dispersion measurements increased substantially, with an additional 1106 qualified EGFs, thereby expanding the spatial coverage and density of data available for tomographic inversion.

- (3)

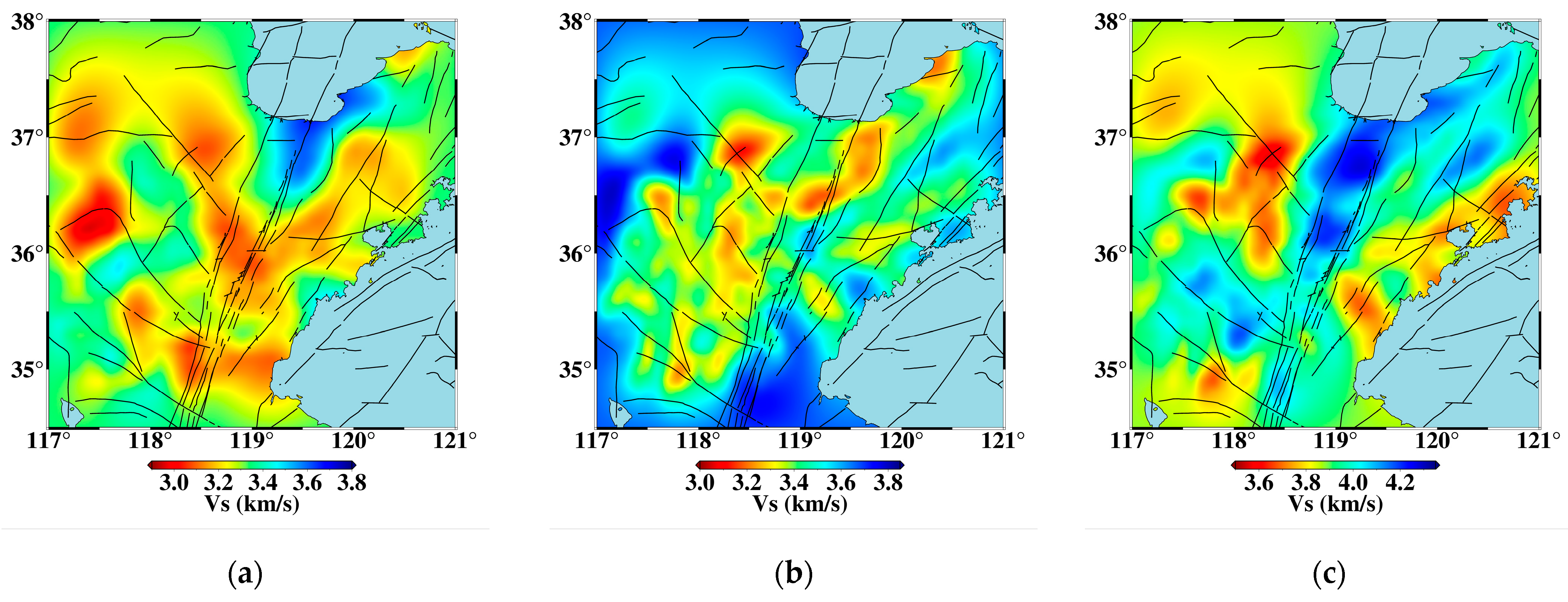

- The enhancement in data quality enables the construction of a more reliable and higher-resolution 3D shear-wave velocity model. Tomographic inversion of the processed data yielded a Vs model with significantly reduced traveltime residuals. The resultant model reveals distinct velocity anomalies that correlate strongly with surface topography, fault structures, and seismicity patterns, providing new geophysical constraints on the differential tectonic processes within the Yishu Fault Zone.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cano, E.V.; Fichtner, A.; Peter, D.; Mai, P.M. The impact of ambient noise sources in subsurface models estimated from noise correlation waveforms. Geophys. J. Int. 2024, 239, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobkis, O.I.; Weaver, R.L. On the emergence of the Green’s function in the correlations of a diffuse field. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2001, 110, 3011–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Fang, G.; Wang, T.; Xia, J.; Hong, Y.; Xi, C.; Liu, Y.; Le, Z. Improving ambient noise crosscorrelations using a polarization-based azimuth filter. Geophysics 2024, 89, Q13–Q24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Miller, R.D.; Park, C.B. Estimation of near-surface shear-wave velocity by inversion of Rayleigh waves. Geophysics 1999, 64, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; van der Hilst, R.D.; de Hoop, M.V. Surface-wave array tomography in SE Tibet from ambient seismic noise and two-station analysis-I. Phase velocity maps. Geophys. J. Int. 2006, 166, 732–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, B.; Xia, J.; Tian, G.; Shi, Z.; Xing, H.; Chang, X.; Xi, C.; Liu, Y.; Ning, L.; Dai, T.; et al. Near-surface imaging from traffic-induced surface waves with dense linear arrays: An application in the urban area of Hangzhou, China. Geophysics 2022, 87, B145–B158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.-C.; Ritzwollerl, M.H.; Townend, J.; Bannister, S.; Savage, M.K. Ambient noise Rayleigh wave tomography of New Zealand. Geophys. J. Int. 2007, 170, 649–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Han, C.; Lindsay, M.D.; Yuan, H.; Zhao, L.; Xiao, W. Imaging Karatungk Cu-Ni Mine in Xinjiang, Western China with a Passive Seismic Array. Minerals 2020, 10, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehly, L.; Campillo, M.; Shapiro, N.M. A study of the seismic noise from its long-range correlation properties. J. Geophys. Res.-Solid Earth 2006, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Luo, Y.H.; Yang, Y.J. Correction of phase velocity bias caused by strong directional noise sources in high-frequency ambient noise tomography: A case study in Karamay, China. Geophys. J. Int. 2016, 205, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.J.; Ritzwoller, M.H. Characteristics of ambient seismic noise as a source for surface wave tomography. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 2008, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.J.; van der Hilst, R.D. Analysis of ambient noise energy distribution and phase velocity bias in ambient noise tomography, with application to SE Tibet. Geophys. J. Int. 2009, 179, 1113–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, V.C. On establishing the accuracy of noise tomography travel-time measurements in a realistic medium. Geophys. J. Int. 2009, 178, 1555–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghisorkhani, H.; Gudmundsson, O.; Roberts, R.; Tryggvason, A. Velocity-measurement bias of the ambient noise method due to source directivity: A case study for the Swedish National Seismic Network. Geophys. J. Int. 2017, 209, 1648–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensen, G.D.; Ritzwoller, M.H.; Barmin, M.P.; Levshin, A.L.; Lin, F.; Moschetti, M.P.; Shapiro, N.M.; Yang, Y. Processing seismic ambient noise data to obtain reliable broad-band surface wave dispersion measurements. Geophys. J. Int. 2007, 169, 1239–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, A.M.; Campillo, M.; Brenguier, F. Denoising seismic noise cross correlations. J. Geophys. Res.-Solid Earth 2009, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seats, K.J.; Lawrence, J.F.; Prieto, G.A. Improved ambient noise correlation functions using Welch’s method. Geophys. J. Int. 2012, 188, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehly, L.; Cupillard, P.; Romanowicz, B. Towards improving ambient noise tomography using simultaneously curvelet denoising filters and SEM simulations of seismic ambient noise. Comptes Rendus Geosci. 2011, 343, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.J.; Lecointre, A.; van der Hilst, R.D.; Campillo, M. Space-time monitoring of groundwater fluctuations with passive seismic interferometry. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmel, M.; Stutzmann, E.; Gallart, J. Using instantaneous phase coherence for signal extraction from ambient noise data at a local to a global scale. Geophys. J. Int. 2011, 184, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Ren, Y.; Gao, H.Y.; Savage, B. An Improved Method to Extract Very-Broadband Empirical Green’s Functions from Ambient Seismic Noise. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2012, 102, 1872–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Xia, J.H.; Xu, Y.X.; Xu, Z.B.; Pan, Y.D. A new passive seismic method based on seismic interferometry and multichannel analysis of surface waves. J. Appl. Geophys. 2015, 117, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ben-Zion, Y.; Zigone, D. Frequency domain analysis of errors in cross-correlations of ambient seismic noise. Geophys. J. Int. 2016, 207, 1630–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.L.; Niu, F.L.; Yang, Y.J.; Xie, J. An investigation of time-frequency domain phase-weighted stacking and its application to phase-velocity extraction from ambient noise’s empirical Green’s functions. Geophys. J. Int. 2018, 212, 1143–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, G.; Brenguier, F.; Campillo, M.; Lynch, R.; Roux, P. Body-wave reconstruction from ambient seismic noise correlations in an underground mine. Geophysics 2015, 80, KS11–KS25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, R.L.; Yoritomo, J.Y. Temporally weighting a time varying noise field to improve green function retrieval. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2018, 143, 3706–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, L.; Stehly, L.; Boué, P.; Lu, Y.; Larose, E.; Campillo, M. Improving ambient noise correlation functions with an SVD-based Wiener filter. Geophys. J. Int. 2017, 211, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonin, N.; Kozloyskaya, E.; Neyalainen, J.; Narkilahti, J. Improving the quality of empirical Green’s functions, obtained by cross-correlation of high-frequency ambient seismic noise. Solid Earth 2019, 10, 1621–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Yang, Y.; Luo, Y. Improving cross-correlations of ambient noise using an rms-ratio selection stacking method. Geophys. J. Int. 2020, 222, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.R.; Niu, F.L.; Qin, L. Denoising Surface Waves Extracted from Ambient Noise Recorded by 1-D Linear Array Using Three-Station Interferometry of Direct Waves. J. Geophys. Res.-Solid Earth 2021, 126, e2021JB021712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Meng, H.R.; Gu, N.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.F.; Ben-Zion, Y. A Frequency Domain Methodology for Quantitative Evaluation of Diffuse Wavefield with Applications to Seismic Imaging. J. Geophys. Res.-Solid Earth 2024, 129, e2024JB028895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Yao, H.J.; Wen, J.; Yang, H.F.; Tian, B.F.; Yan, M.X. Apparent Low-Velocity Belt in the Shallow Anninghe Fault Zone in SW China and Its Implications for Seismotectonics and Earthquake Hazard Assessment. J. Geophys. Res.-Solid Earth 2023, 128, e2022JB025681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.Q.; Yang, J.D.; Qin, N.; Li, Z.C.; Huang, J.P.; Shan, T.T. An Adaptive High-Dimensional Progressive Denoising Method for Seismic Weak Signal Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5935210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, P.; Sabra, K.G.; Kuperman, W.A.; Roux, A. Ambient noise cross correlation in free space: Theoretical approach. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2005, 117, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabra, K.G.; Roux, P.; Kuperman, W.A. Emergence rate of the time-domain Green’s function from the ambient noise cross-correlation function. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2005, 118, 3524–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Yao, H.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Y.-C.; van der Hilst, R.D. Direct inversion of surface wave dispersion for three-dimensional shallow crustal structure based on ray tracing: Methodology and application. Geophys. J. Int. 2015, 201, 1251–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocher, T.M. Empirical relations between elastic wavespeeds and density in the Earth’s crust. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2005, 95, 2081–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, K.; Yang, J.; Zhang, S.; Huang, J.; Wang, W.; Shan, T. Application of a Fractional Laplacian-Based Adaptive Progressive Denoising Method to Improve Ambient Noise Crosscorrelation Functions. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 802. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120802

Yu K, Yang J, Zhang S, Huang J, Wang W, Shan T. Application of a Fractional Laplacian-Based Adaptive Progressive Denoising Method to Improve Ambient Noise Crosscorrelation Functions. Fractal and Fractional. 2025; 9(12):802. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120802

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Kunpeng, Jidong Yang, Shanshan Zhang, Jianping Huang, Weiqi Wang, and Tiantao Shan. 2025. "Application of a Fractional Laplacian-Based Adaptive Progressive Denoising Method to Improve Ambient Noise Crosscorrelation Functions" Fractal and Fractional 9, no. 12: 802. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120802

APA StyleYu, K., Yang, J., Zhang, S., Huang, J., Wang, W., & Shan, T. (2025). Application of a Fractional Laplacian-Based Adaptive Progressive Denoising Method to Improve Ambient Noise Crosscorrelation Functions. Fractal and Fractional, 9(12), 802. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120802