1. Introduction

With the gradual improvement of computers’ ability to process big data, neural networks (NNs) are becoming increasingly widely used in various fields, such as data visualization [

1], intelligent computation [

2,

3,

4], automation [

5,

6], and system stability [

7,

8,

9]. Synchronization, as one of the most typical collective dynamic behaviors in NNs, refers to the phenomenon where the discharge activities or state evolutions of multiple or even all neurons in the network tend to be consistent over time [

10]. In biological brains, synchronization is believed to be closely related to various cognitive functions, such as attention, perceptual binding, memory formation, and information transmission. Understanding and controlling synchronization behaviors are crucial for designing intelligent information processing systems in artificial NNs and neuromorphic computing [

11]. The common synchronization types of NNs include bipartite synchronization [

12], projective synchronization [

13], finite-time synchronization [

14], fixed-time synchronization [

15,

16], etc.

To characterize the change rate of network dynamic behavior over time, traditional integer calculus operators are commonly used for network modeling [

17]. The information propagation efficiency between network nodes is influenced by factors such as network topology, node degree, and inter-node distance [

18]. For many NNs, relying solely on the evolution of the network itself is not enough, and external control inputs need to be applied to achieve the synchronization objective [

19]. The commonly used control methods include feedback control [

20], adaptive control [

21], hybrid control [

22], and event-triggered control [

23]. In reality, finite-time and fixed-time synchronization control technologies offer disturbance rejection capabilities and enhanced robustness, making them applicable across a wide range of fields. Therefore, researchers have paid attention to finite-time and fixed-time synchronization for various NNs and have obtained many important results. For instance, Abdurahman et al. [

24] focused on the fixed-time synchronization patterns of nonlinear coupled NNs under the stability theory and inequality techniques. Qiao et al. [

25] investigated the fixed-time synchronization of coupled delayed networks by intermittent feedback control schemes. The authors in [

26] discussed the fixed-time synchronization of coupled NNs by adaptive feedback control schemes. More fixed-time synchronization results of NNs by means of different control schemes can be found in [

27,

28].

Fractional calculus, as an extension of traditional calculus, includes an integral term from the initial moment to the current moment [

29]. This means that when calculating the fractional derivative at the current time, all information from the entire historical process needs to be considered [

30,

31,

32,

33]. Hence, fractional-order NNs can describe complex processes with memory and historical dependencies, which is difficult to achieve by traditional integer-order NNs [

34]. In reality, the charging and discharging behavior of batteries, as well as the penetration of drugs into tissues, naturally exhibit fractional-order kinetic characteristics. Recently, scholars have extensively investigated various dynamic behaviors of fractional-order delayed NNs, such as synchronization [

35,

36], dissipativity [

37,

38], and stability [

39,

40]. For integer-order systems, the Lyapunov direct method is a powerful tool for proving synchronization stability and designing controllers. But its direct generalization in fractional-order systems faces enormous mathematical challenges. Up to now, many studies on fractional-order NNs have mainly focused on specific kinds of time delays, such as fixed delay [

35,

37], bounded variable delay [

36], and bounded mixed delay [

40].

Proportional delay differs from the fixed delay and the bounded delay mentioned earlier, as it is an unbounded time-varying delay proportional to the current time

u [

41]. This type of time delay is generally defined as

, where

, and has been widely studied in the context of various physical phenomena, biological systems, and synchronization control [

42]. For instance, Xu et al. [

43] investigated the feedback control synchronization of fractional-order proportional delay neural networks (PDNNs) by constructing a graph-theoretical Lyapunov function that includes three-term functions. In [

44], the authors discussed the bipartite synchronization of fractional-order coupled PDNNs based on graph theory and the Razumikhin method. In [

45], He et al. deliberated on the event-triggered synchronization of fractional-order PDNNs with quaternion values utilizing the Razumikhin theorem and stability theory, thereby facilitating the application of the results to image encryption and decryption. Additionally, Duan et al. [

46] solved the finite-time synchronization of complex-valued PDNNs by combining non-smooth theory and complex domain inequalities.

In addition, the limited performance of observers and the sensitivity of systems to external environments may lead to uncertainties in NNs. Deterministic parameters will produce ordered behavior, while uncertainties in the parameters may cause the network to be in an unstable state, thereby increasing control difficulty [

47]. Kong et al. [

48] were devoted to the fixed-time synchronization of Cohen–Grossberg NNs with uncertainties by adaptive control methods. Scholars have studied various synchronization frameworks for NNs with parameter uncertainties and obtained many important synchronization results [

49,

50]. However, both unbounded proportional delay and bounded parameter uncertainty can lead to long-term instability of the system state. To our knowledge, very few works focus on the fixed-time synchronization of fractional-order Hopfield NNs with unbounded proportional delay and bounded uncertainties, using state feedback with negative fractional derivatives. Therefore, a key objective of this work is to design a multi-module feedback controller to mitigate the combined impacts of uncertainties and proportional delay on system stability, which constitutes the primary challenge addressed in this paper.

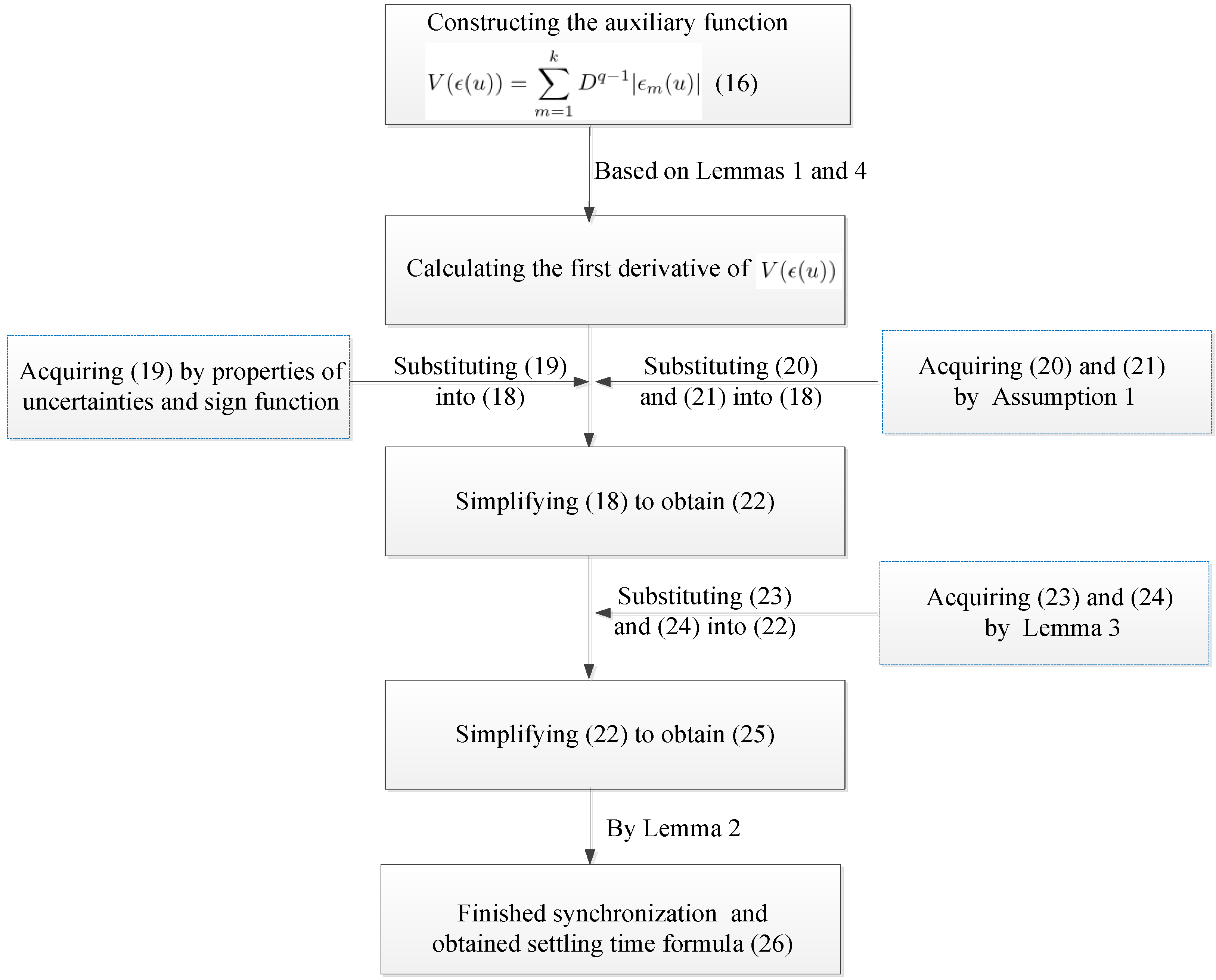

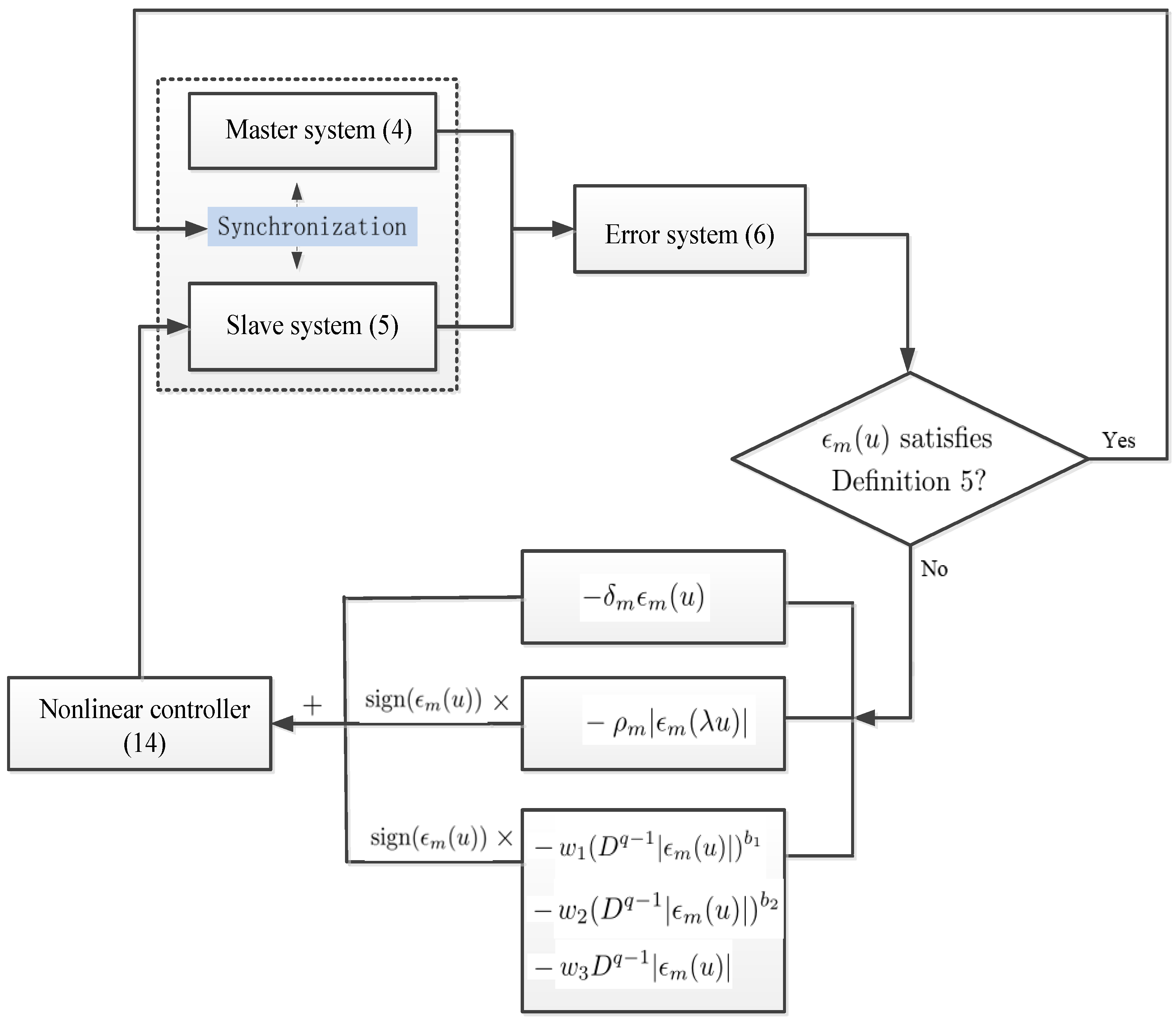

Inspired by the preceding analysis, this paper deliberates on the fixed-time synchronization for fractional-order PDHNNs with parameter uncertainties. The key contributions are summarized as three aspects. First, we consider a fractional-order nonlinear model that accounts for both unbounded delays and bounded uncertainties, which is different from the bounded delayed NNs in [

36,

39]. Second, we design a robust feedback controller that includes three important function modules: a module designed to eliminate the impact of proportional delay on system stability; a module that ensures fixed-time convergence independent of the initial conditions; and a module that expands the selectable range of controller parameters. In existing works [

33,

34,

35,

44], the submodule function in multi-module controllers tends to infinity over time evolution, which affects their generalization and application. Unlike these control strategies, both our controller and Lyapunov function contain negative fractional derivatives of the error function, and each submodule function is bounded. Lastly, by applying the fixed-time stability lemma and fractional Lyapunov function and inequality techniques, the synchronization criteria for PDHNNs are derived under the proposed control schemes, and the calculation formula of the settling time is independent of the initial values of the system.

2. Preliminaries and Fractional-Order PDHNNs

This section provides some fundamental background knowledge about fractional-order integrals and derivatives. Then, fractional-order primary–secondary PDHNNs with parameter uncertainties are given.

Definition 1 ([

29])

. For , the Gamma function is defined as Definition 2 ([

29])

. For a continuous integrable function , the q-order Caputo integral iswhere and . Definition 3 ([

29])

. The q-order Caputo derivative of a function iswhere , and . Especially, when , . Lemma 1 ([

34])

. For the function , , one can obtain Remark 1. Caputo fractional derivatives can be used to model network systems with non-local features. Unlike Riemann-Liouville fractional derivatives, it takes into account the initial conditions of the function, giving them clear physical meaning and making them more practical in engineering applications. To simplify the expression, we denote in the remainder of this article.

Consider fractional-order PDHNNs with unbounded proportional delay and bounded parameter uncertainties as follows:

where

,

.

is the self-regulating coefficient.

is the

mth state variable at instant

u.

represents the nonlinear activation of the

nth neuron.

and

represent the connection weights of the unit

n to the unit

m at instants

u and

, respectively.

denotes the proportional delay factor satisfying

.

describes the transmission delay

, which represents the unbounded time-varying delay.

and

characterize the parameter uncertainties, which satisfy bounded conditions

and

.

stands for the

mth external constant input.

Taking

q-order PDHNNs (

4) as the primary system, then the

q-order secondary system is given by

where

,

, and

is the

mth state variable in the secondary system.

denotes the initial condition and

represents the control input at instant

u.

To derive the error expression between systems (

4) and (

5), we define the synchronization error as

. Then one can get

where

,

.

For convenience, we define and .

Assumption 1. For the activation function , there exist a constant satisfyingfor . Definition 4 ([

38])

. The origin of network system (6) is finite-time stable if there exists satisfyingwhere denotes the settling time. Definition 5 ([

38])

. The origin of network system (6) is fixed-time stable if the origin of (6) is finite-time stable and there is a fixed scalar such that for ∀. Remark 2. From the above two definitions, finite-time synchronization achieves the convergence of the error state of a dynamical system within a time dependent on the initial state, whereas fixed-time synchronization guarantees convergence within a bounded, pre-computable time independent of the initial states.

Remark 3. Finite-time synchronization tasks of fractional-order NNs have been studied in [33,34,35]. In contrast, fixed-time synchronization is a significant development of finite-time synchronization, ensuring that the primary and secondary systems synchronize within a unified time range, and the synchronization results are independent of initial states. The fixed-time synchronization results are particularly suitable for scenarios with strict convergence-time requirements, such as multi-agent systems, drone formations, and robot collaboration. For example, in a drone swarm performing collaborative reconnaissance or material transport, all units must achieve highly consistent posture, position, and velocity information. By treating each drone as a dynamical subsystem, a multi-mode controller can be designed to synchronize the entire swarm within a fixed time, ensuring timely and coordinated task execution. Remark 4. In [30,31], various dynamic behaviors of fractional-order Hopfield NNs have been studied using methods such as bifurcation diagrams and Lyapunov exponent analysis. In [32], fractional-order Hopfield NNs have been applied to achieve medical image encryption. In contrast, this work investigates a more general model that incorporates both unbounded proportional delay and bounded uncertainties, thereby addressing a broader and more practical class of systems. Lemma 2 ([

51])

. Assume is a continuous and unbounded function meeting- (I)

if .

- (II)

Each solution of system (6) satisfies

where , , and . Then the origin of system (6) is fixed-time stable. The settling time can be estimated by Lemma 3 ([

11])

. Let , , and . Then one can obtainand Lemma 4 ([

52])

. For a continuously differentiable function , one can getwhere sign(·) denotes the signum function. Remark 5. Lemma 4 has an extensive application in the synchronization control of fractional-order networks, providing excellent estimation for the fractional derivatives of the absolute value parts, such as [45,53]. In this paper, the lemma plays a crucial role in the stability analysis of error systems based on Lyapunov functions, particularly when dealing with the absolute value function of . 4. Simulation Examples

Two simulation experiments are given to confirm the applicability of synchronization results in Theorem 1 and Corollary 1.

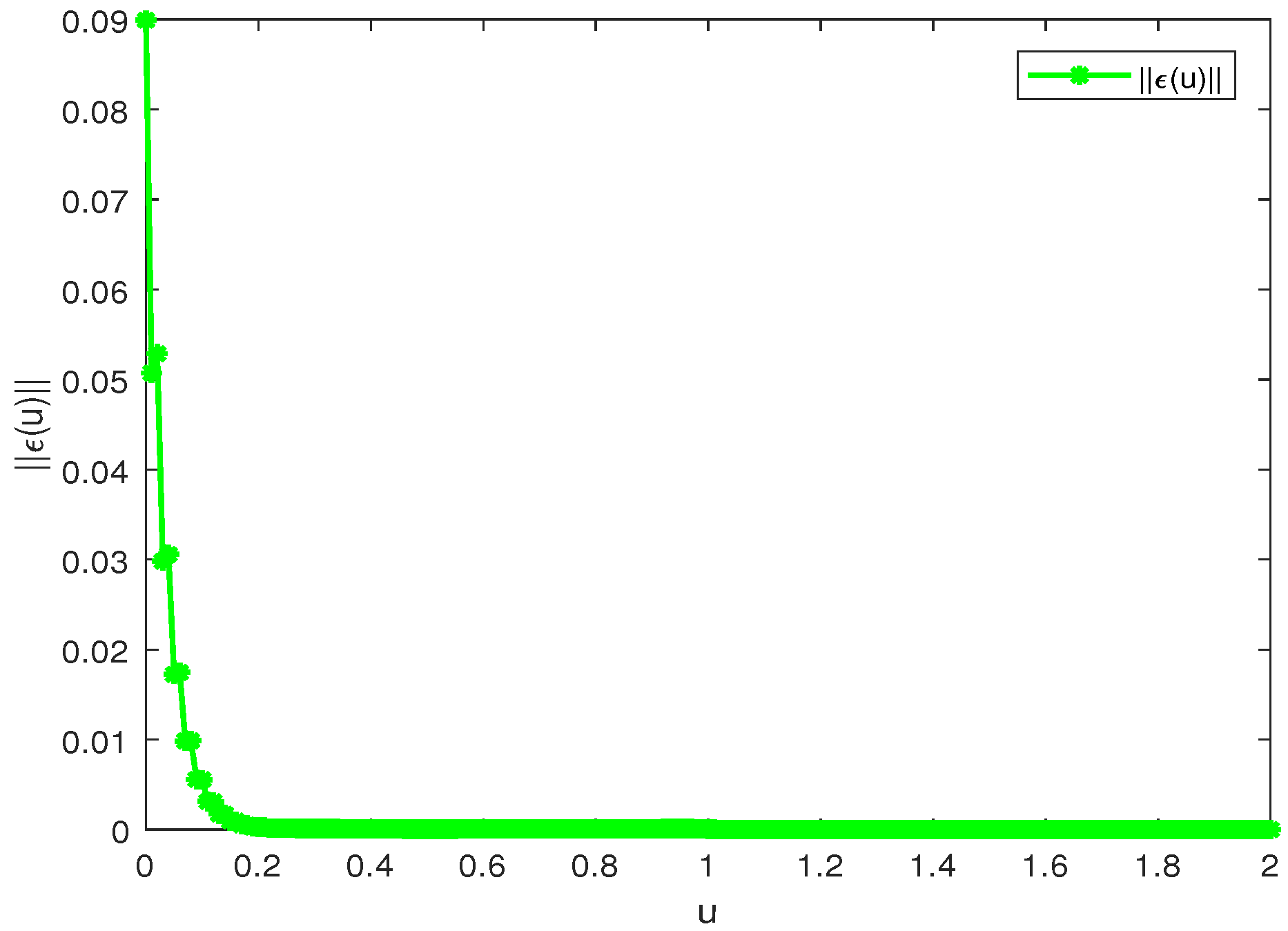

Example 1. Consider 2-dimensional fractional PDHNNs with bounded uncertainties as the primary system, which is described by Then, the consequential secondary system can be defined bywhere , , , . Giving the activation functions , we can check that Assumption 1 holds for . Let parameters , and . Through simple calculations, one can obtain , , , .

It is clear that the above parameter values satisfy the conditions in Theorem 1. According to calculation Formula (

15), the settling time can be estimated as 1.7285 s. The initial conditions are chosen as

. Under the above control parameters, the error evolution of each neuron over time is shown in

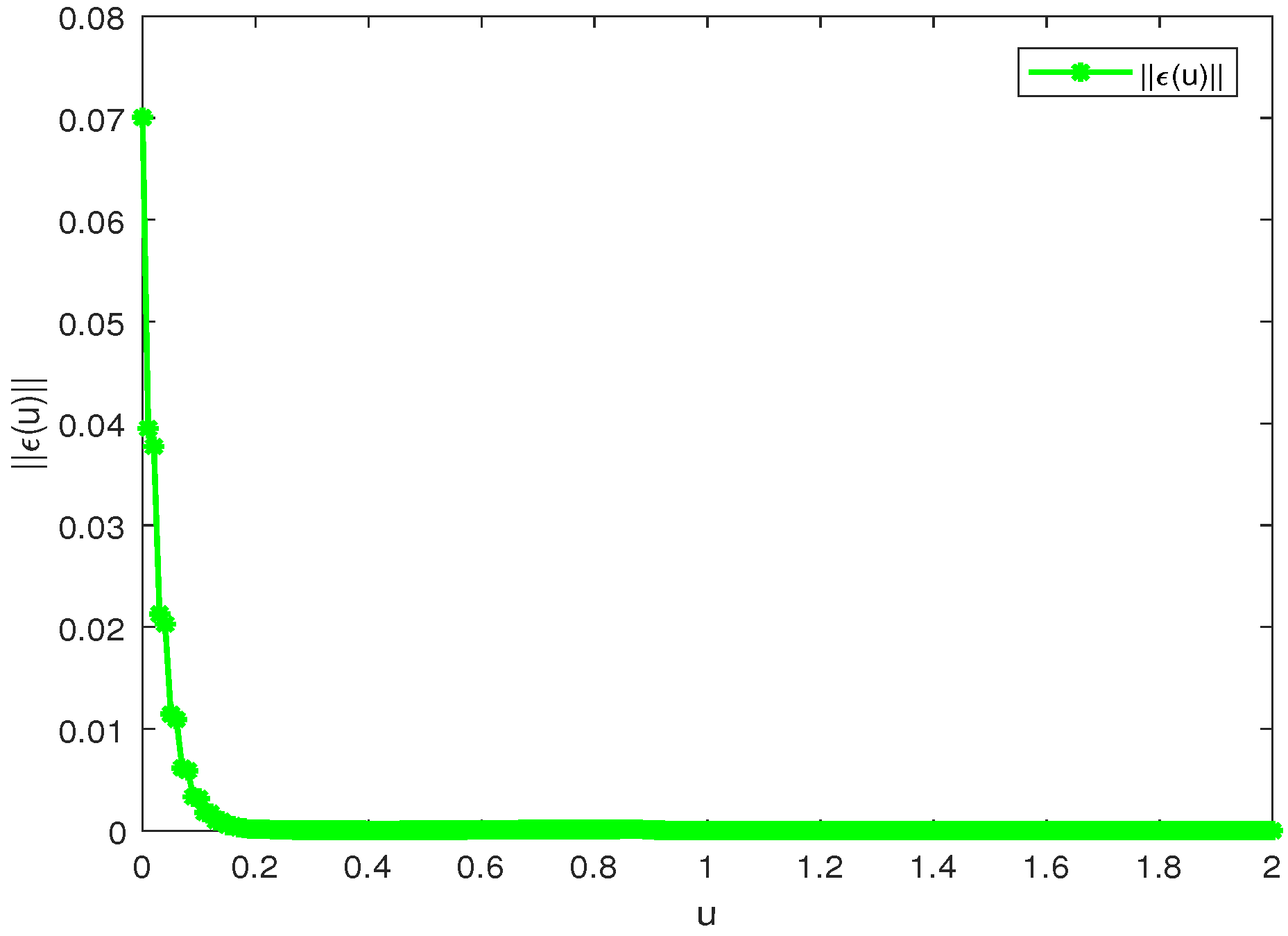

Figure 3. The blue and red dashed lines represent the error states of the first and second neurons, respectively. The evolution of the error norm over time can be seen in

Figure 4. From

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, it is evident that the errors of primary–secondary systems (

30) and (

31) converge to zero within the specified time, indicating that the network achieves synchronization within a fixed time.

To assess the impact of parameter changes on synchronization capability, we focus on studying the uncertainties and the strength of feedback control. To simultaneously evaluate the robustness of our controller, initial values were randomly selected from the range of

. Two types of experiments use different initial values, and experiments of the same type use the same initial values to ensure experimental fairness. The coefficients of parameter uncertainties are selected as 0.1, 0.2, and 0.3, respectively. As shown in

Figure 5, the larger the coefficient, the longer the time spent for the system to achieve synchronization. In addition, we adjust the control strength

under the same initial conditions and observe its impact on system synchronization.

Figure 6 shows that as the control strength increases, the time for the primary–secondary networks to achieve synchronization gradually decreases. The above experiments indicate that our control method is not limited by the changes of initial conditions and parameters. As long as the parameters satisfy the conditions of Theorem 1, the fixed-time synchronization task of fractional PDHNNs can be completed.

To observe the influence of control parameters on the settling time, we first adjust

with a step size of 0.2 and keep the other parameters unchanged. The results in

Table 1 indicate that as

increases, the settling time actually decreases. Similarly, using step sizes of 0.2 and 0.5 to change the parameters

and

, one can see that the larger

and

are, the shorter the settling time, as shown in

Table 2 and

Table 3. Furthermore, adjusting the parameter

from 0.65 to 0.95 with a step size of 0.05, it is not difficult to find that the settling time is proportional to the parameter

, as shown in

Table 4. Eventually,

Table 5 shows that selecting a larger parameter

is beneficial to shorten the settling time. The above discussion provides a guide on how to select control parameters to derive small settling time. In practical applications, it is necessary to select control parameters in conjunction with control cost.

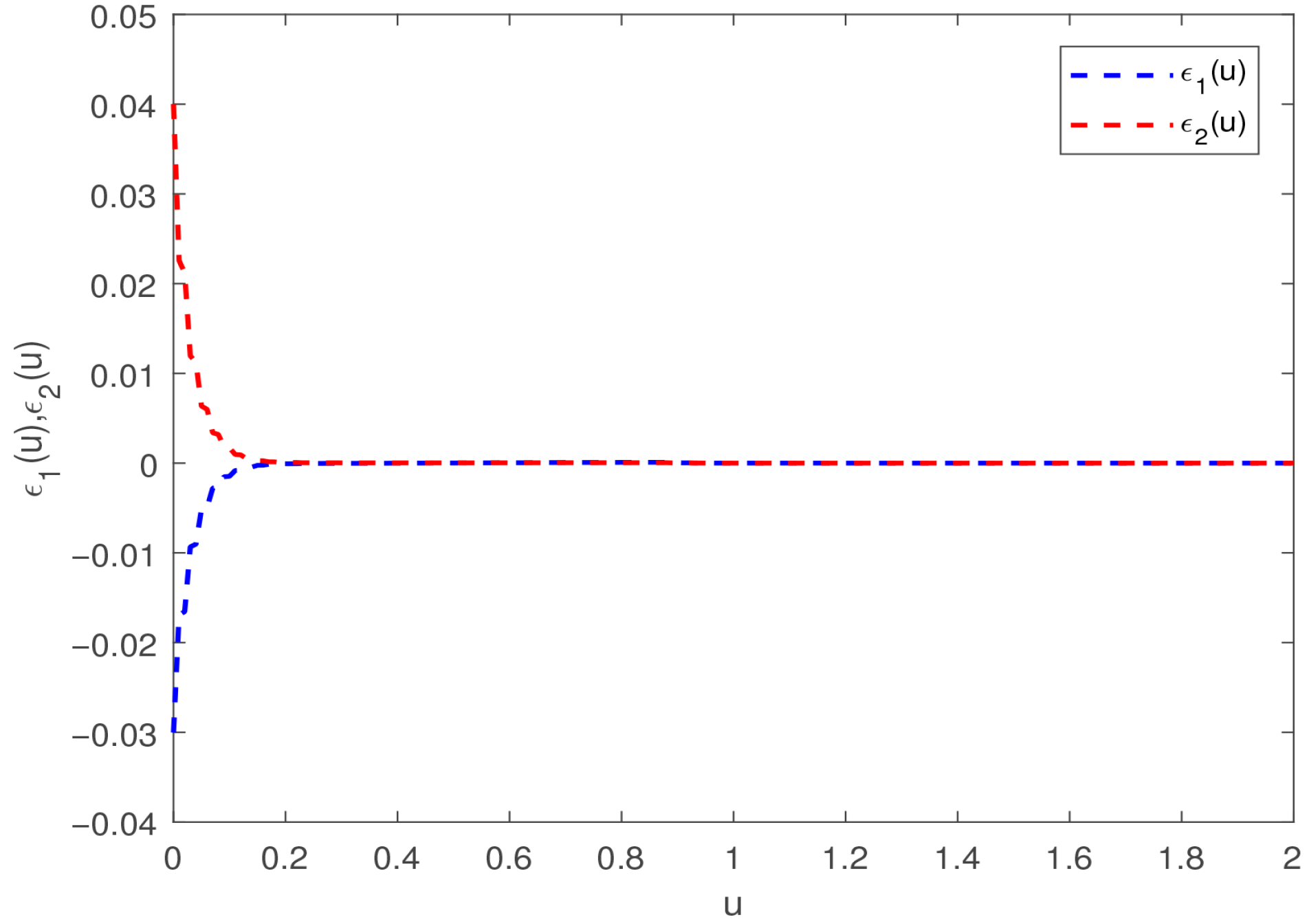

Example 2. Consider 2-dimensional fractional PDHNNs without uncertainties as the primary system, described as follows: Then, the consequential secondary system can be given bywhere , , . The activation functions are , which satisfy Assumption 1 for . Let parameters , and . Through simple calculations, one can get , , , and .

The above inequalities demonstrate that the selected parameters satisfy the conditions in Corollary 1. By calculation Formula (

15), the settling time can be estimated as 1.5671 s. The initial conditions are chosen as

and

. Under the nonlinear controller with the above parameters,

Figure 7 gives the time evolution of neuron errors

and

between systems (

32) and (

33).

Figure 8 depicts the corresponding time evolution of error norm

. As shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, the fixed-time synchronization of controlled systems can be achieved within the settling time. For convenience in observing the variation of the error,

Table 6 presents the state of the changes in the error norm. As can be seen, the error norm

gradually converges to zero within 0.21 s.

To compare the performance of different feedback controllers, we take into account the average convergence time and variance. Considering that some control strategies cannot address the synchronization problem in unbounded-delay networks, the system and controllers do not account for proportional delay. Randomly select initial values from [−0.3, 0.3], and execute six times for each controller under the same conditions. From

Table 7, the multi-mode controller proposed in this paper has advantages in average convergence time and variance. The convergence time of our controller is

lower than the second-place controller, and the variance is

smaller than the nonlinear feedback controller in [

34].

Remark 10. For the numerical simulation of fractional-order delayed systems, we employ the Adams–Bashforth–Moulton method [54] to solve the differential equations within the MATLAB R2020b environment. The implementation involves two key steps. First, the time domain is uniformly discretized, and the product rectangle formula is applied to estimate the fractional-order integral, yielding an initial approximate solution (the predictor). Subsequently, a corrected solution is computed using the product trapezoidal formula, which refines the initial estimate for higher accuracy (the corrector). The predictor-corrector steps ensure the robustness and accuracy of the simulation results.