Fractional Modeling and Stability Analysis of Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus Disease: Insights for Sustainable Crop Protection

Abstract

1. Introduction

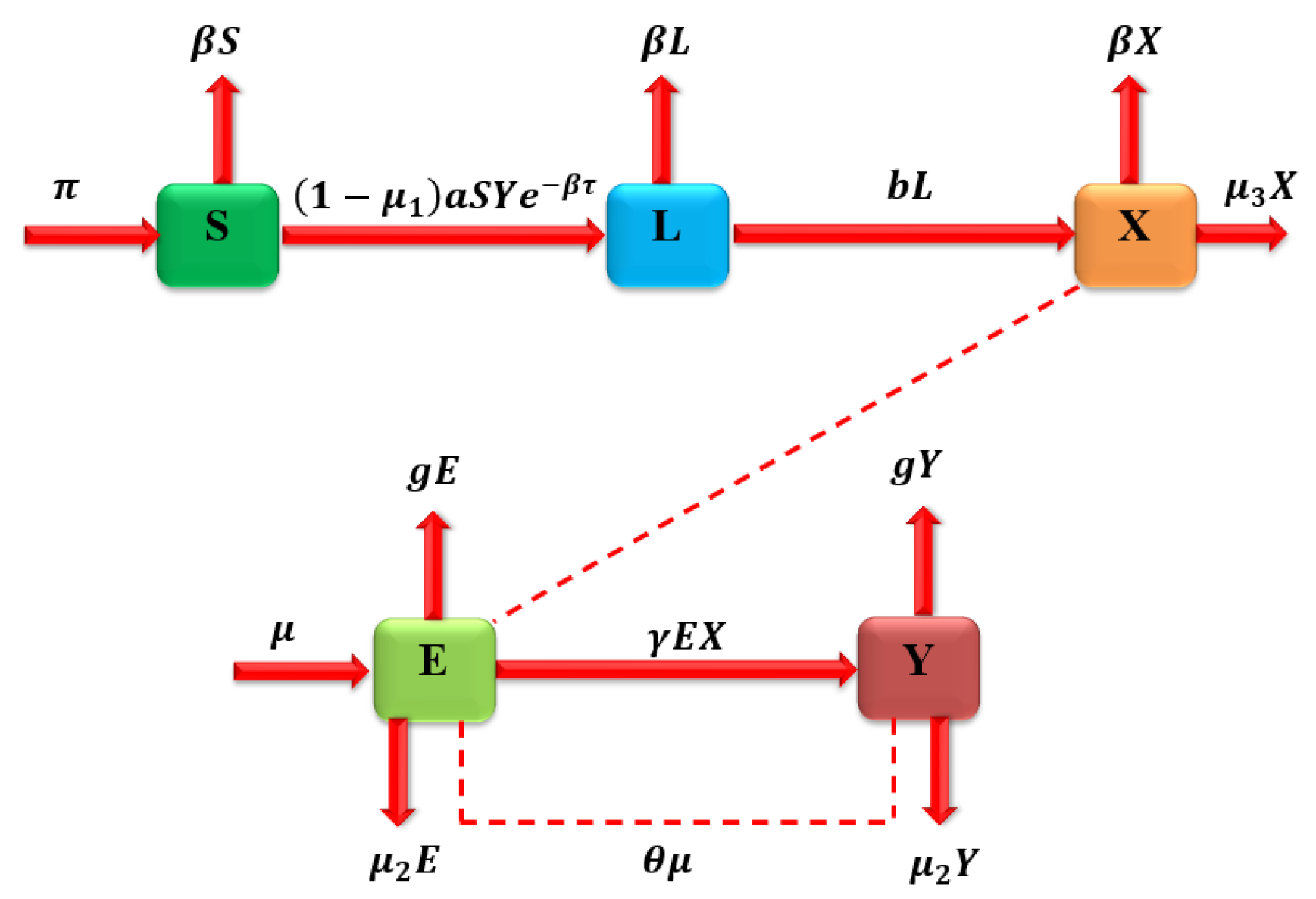

2. Basic Preliminary

3. Model Formulation

4. Properties

4.1. Positivity and Boundedness

4.2. Existence and Uniqueness

5. Equilibrium States and Reproduction Number

6. Stability Analysis

6.1. Local Stability Analysis

6.2. Global Stability Analysis

7. Sensitivity Analysis

8. Grünwald–Letnikov Nonstandard Finite Difference Scheme

8.1. Positivity and Boundedness of the Scheme

8.2. Stability

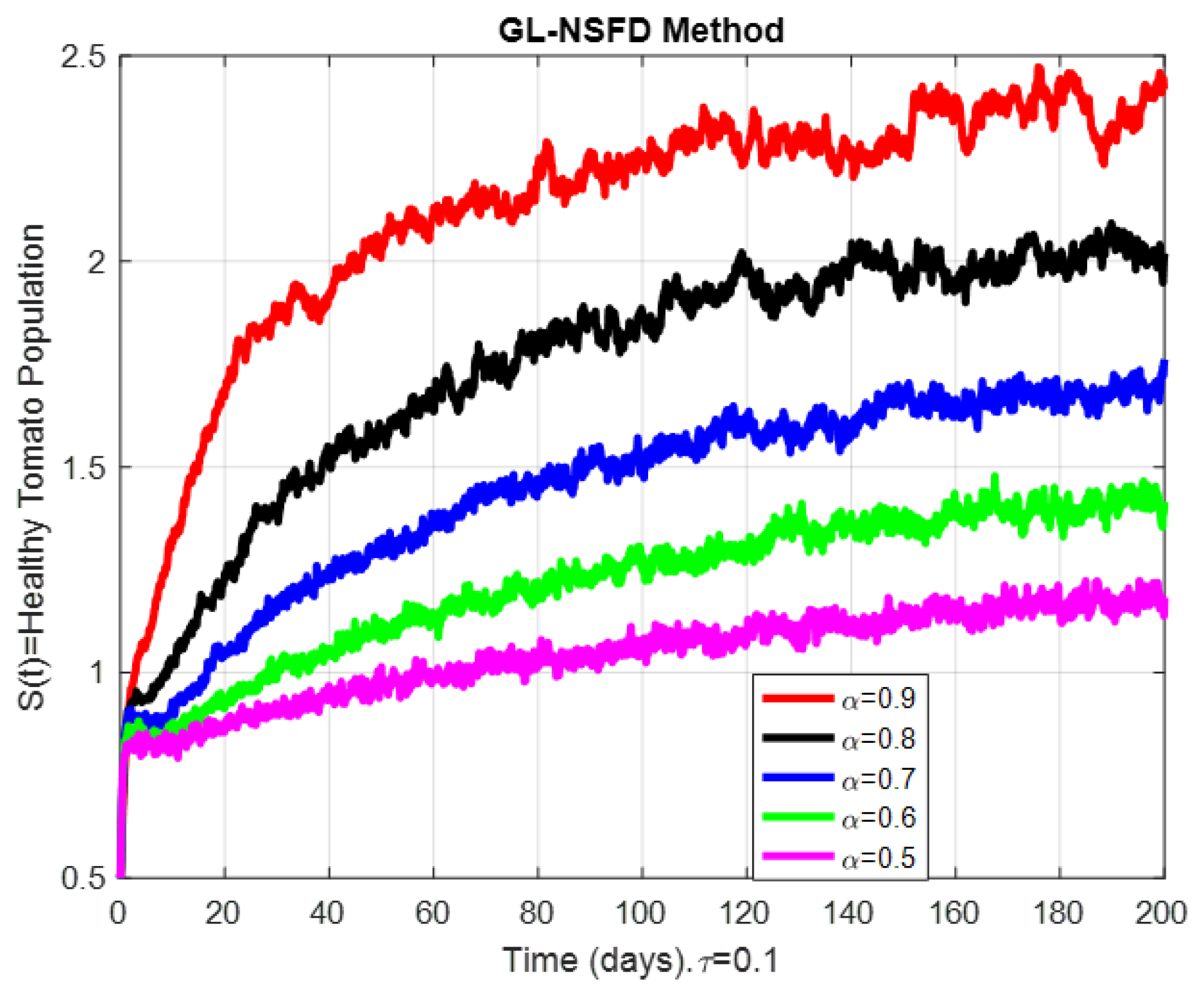

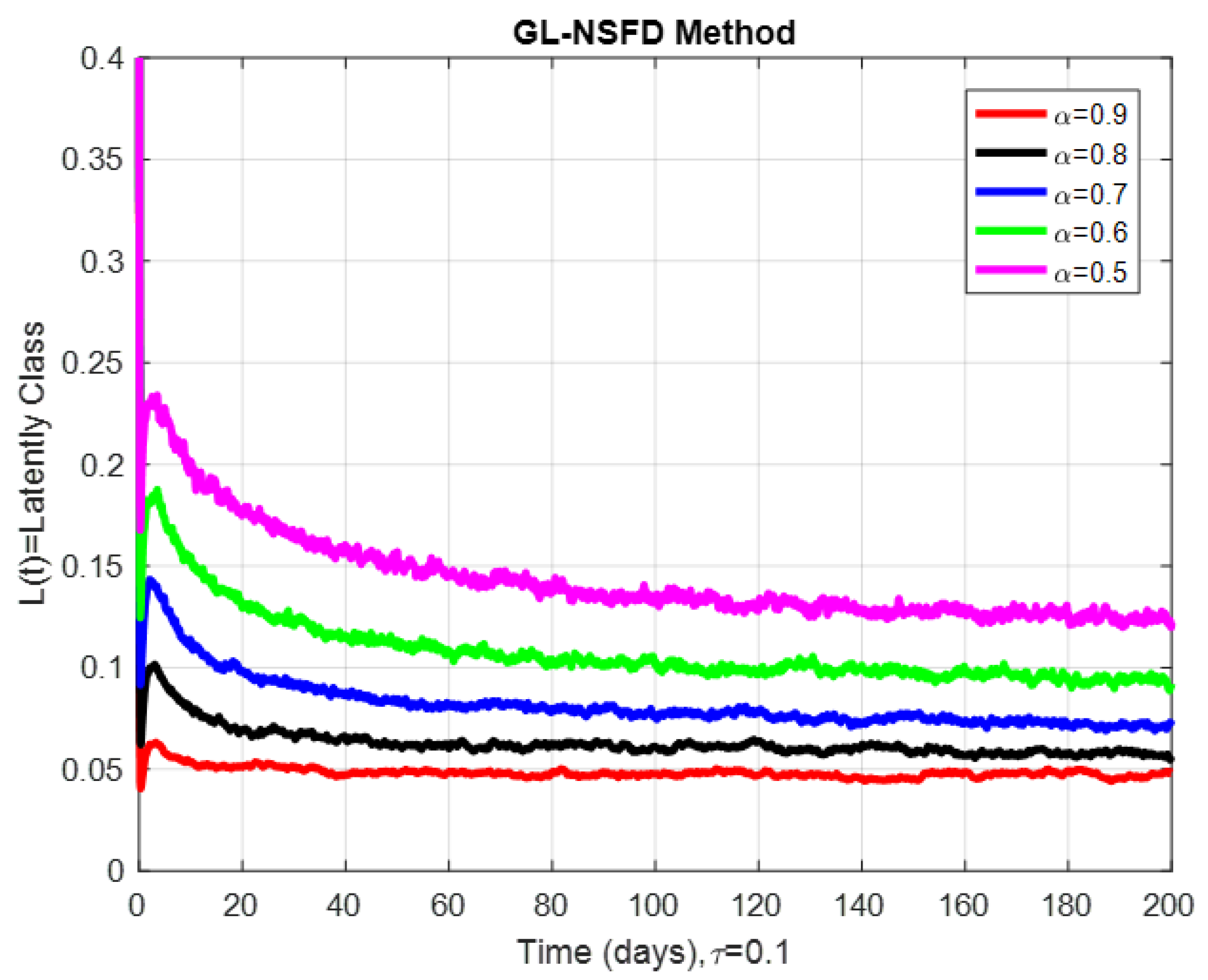

9. Numerical Simulation and Discussion

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hugo, A.; Lusekelo, E.M.; Kitengeso, R. Optimal control and cost effectiveness analysis of tomato yellow leaf curl virus disease epidemic model. Appl. Math. 2019, 9, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, H.; Wei, L. Tomato yellow leaf curl virus detection based on cross-domain shared attention and enhanced BiFPN. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 85, 102912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmati, F.; Behjatnia, S.A.A.; Moghadam, A.; Afsharifar, A. Induction of systemic resistance against cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) and tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV) in tomato. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2025, 71, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gong, P.; Zhao, S.; Li, F.; Zhou, X. Functional Characterization of Dual-Initiation Codon-Derived V2 Proteins in Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeda, S.; Fortes, I.M.; Rodríguez-López, M.J.; Fernández-Muñoz, R.; Moriones, E. Resistance to the insect vector Bemisia tabaci enhances the robustness and durability of tomato yellow leaf curl virus resistance conferred by Ty-1. Plant Dis. 2025, 109, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Bag, S.; McAvoy, T.; Torrance, T.; Cloud, C.; Simmons, A.M. A shift in begomovirus Coheni populations associated with tomato yellow leaf curl disease infecting tomato cultivars in the southeastern united States. Plant Pathol. 2025, 74, 1277–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Mu, S.; Peng, Y.; Wu, D.; Yang, L.; Li, Q.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, J. Discovery of Arbutin as Novel Potential Antiviral Agent Against Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 3967–3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhang, L.; Yan, X.T.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, X.Y.; Chen, J.P.; Liu, S.S.; Wang, X.W. Suppression of TGA2-mediated Salicylic Acid Defence by Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus C2 via Disruption of TCP7-like Transcription Factor Activity in Tobacco. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 4039–4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brites, N.M.; Braumann, C.A. Profit Optimization of Stochastically Fluctuating Populations under Harvesting: The Effects of Allee Effects. Optimization 2022, 71, 3277–3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo-Varela, G.; Diaz-Infante, S. Threshold behaviour of a stochastic vector plant model for tomato yellow curl leaves disease: A study based on mathematical analysis and simulation. Int. J. Comput. Math. 2024, 101, 1430–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Septiana, A.Z.; Mahfut, M.; Handayani, T.T.; Suratman. Survey of Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV) infection on Solanum lycopersicum L. in Lampung, Indonesia. AIP Conf. Proc. 2024, 2970, 050027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Matroushi, A.R.; e Ammara, U.; Shahid, M.S.; Khan, J.; Al-Sadi, A.M. Genetic diversity and infectivity analysis of tomato yellow leaf curl virus Oman and its associated betasatellite. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2024, 70, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchant, W.G.; Brown, J.K.; Gautam, S.; Ghosh, S.; Simmons, A.M.; Srinivasan, R. Non-feeding transmission modes of the tomato yellow leaf curl virus by the whitefly Bemisia tabaci do not contribute to reoccurring leaf curl outbreaks in tomato. Insects 2024, 15, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Gao, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, K.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, D.; Chen, J.; Peng, J.; Gao, Y.; Du, J.; et al. D-limonene affects the feeding behavior and the acquisition and transmission of tomato yellow leaf curl virus by Bemisia tabaci. Viruses 2024, 16, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koeda, S.; Kitawaki, A. Breakdown of Ty-1-based resistance to tomato yellow leaf curl virus in tomato plants at high temperatures. Phytopathology 2024, 114, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaertner, N.F.; Maio, F.; Arroyo-Mateos, M.; Luna, A.P.; Sabarit, B.; Kwaaitaal, M.; Eltschkner, S.; Prins, M.; Bejarano, E.R.; van den Burg, H.A. A SUMO interacting motif in the Replication initiator protein of Tomato yellow leaf curl virus is required for viral replication. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.M.; Xie, T.; He, Y.Z.; Cuellar, W.J.; Wang, X.W. Heat stress promotes the accumulation of tomato yellow leaf curl virus in its insect vector by activating heat shock factor. Crop Health 2024, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbar, Y.; Aldosary, S.F. A general epidemic model with variable-order fractional derivatives and Lévy noise: Dynamical analysis and application to historical influenza data. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 130, 459–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petráš, I. Fractional-Order Nonlinear Systems: Modeling, Analysis and Simulation; Nonlinear Physical Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Podlubny, I. Fractional Differential Equations: An Introduction to Fractional Derivatives, Fractional Differential Equations, to Methods of Their Solution and Some of Their Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998; Volume 198. [Google Scholar]

- Kilbas, A. Theory and Applications of Fractional Differential Equations; North-Holland Mathematics Studies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 204. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Podlubny, I. Stability of fractional-order nonlinear dynamic systems: Lyapunov direct method and generalized Mittag–Leffler stability. Comput. Math. Appl. 2010, 59, 1810–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butter, N.; Rataul, H. The virus-vector relationship of the Tomato leafcurl virus (TLCV) and its vector, Bemisia tabaci Gennadius (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae). Phytoparasitica 1977, 5, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Turechek, B.W.; Adkins, S.; Luo, W.; Mellinger, H.C.; Smith, H.; Kousik, C.S.; Roberts, P.; Parks, F.; Lucas, L.; et al. Satellite-based Crop Identification and Risk Profiling for Area Wide Management of Whitefly and Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus in Southwest Florida. Plant Dis. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, F. A survey on the stability of fractional differential equations: Dedicated to Prof. YS Chen on the Occasion of their 80th Birthday. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2011, 193, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamir, M.; Nadeem, F.; Abdeljawad, T.; Hammouch, Z. Threshold condition and non pharmaceutical interventions’s control strategies for elimination of COVID-19. Results Phys. 2021, 20, 103698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhe, H.W.; Gebremeskel, A.A.; Melese, Z.T.; Al-arydah, M.; Gebremichael, A.A. Modeling and global stability analysis of COVID-19 dynamics with optimal control and cost-effectiveness analysis. Partial. Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 2024, 11, 100843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitnis, N.; Hyman, J.M.; Cushing, J.M. Determining important parameters in the spread of malaria through the sensitivity analysis of a mathematical model. Bull. Math. Biol. 2008, 70, 1272–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, R.; Kalla, S.L.; Tang, Y.; Huang, J. The Grünwald–Letnikov method for fractional differential equations. Comput. Math. Appl. 2011, 62, 902–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweilam, N.; Nagy, A.; Elfahri, L. Nonstandard finite difference scheme for the fractional order Salmonella transmission model. J. Fract. Calc. Appl. 2019, 10, 197–212. [Google Scholar]

- Narasegowda Maruthi, M.; Czosnek, H.; Vidavski, F.; Tarba, S.Y.; Milo, J.; Leviatov, S.; Mallithimmaiah Venkatesh, H.; Seetharam Padmaja, A.; Subbappa Kulkarni, R.; Muniyappa, V. Comparison of resistance to Tomato leaf curl virus (India) and Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (Israel) among Lycopersicon wild species, breeding lines and hybrids. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2003, 109, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Description | Experimental Basis/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Rate at which healthy tomato plants are introduced into the field | Assumed | |

| Constant removal rate of all plant classes due to the fixed crop cycle duration | [1] | |

| a | Rate at which healthy plants become latently infected due to contact with infective vectors | [5,14] |

| b | Rate at which latently infected plants become infectious (inverse of mean latent period) | [3,15] |

| Rate at which non-infective vectors acquire infection from infectious plants | [23] | |

| Constant rate of incoming vectors from external sources | Assumed | |

| Fraction of immigrating vectors that are infective | [1] | |

| g | Natural death rate of the vector population | [5] |

| Intensity of protective netting to reduce vector immigration | [1] | |

| Intensity of insecticide spraying to decrease vector abundance | [24] | |

| Intensity of infected plant removal and safe disposal measures | [1] |

| Parameter | Value | Sensitivity Index |

|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | ||

| 0.4348 | ||

| 0.5 | ||

| 0.5 | ||

| 0.5 | ||

| −0.125 | ||

| −0.10437 | ||

| −0.0555 | ||

| −0.2727 | ||

| −0.2727 | ||

| −0.083 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alsulami, M.; Raza, A.; Lampart, M.; Shafique, U.; Rezk, E.G. Fractional Modeling and Stability Analysis of Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus Disease: Insights for Sustainable Crop Protection. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 754. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120754

Alsulami M, Raza A, Lampart M, Shafique U, Rezk EG. Fractional Modeling and Stability Analysis of Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus Disease: Insights for Sustainable Crop Protection. Fractal and Fractional. 2025; 9(12):754. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120754

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlsulami, Mansoor, Ali Raza, Marek Lampart, Umar Shafique, and Eman Ghareeb Rezk. 2025. "Fractional Modeling and Stability Analysis of Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus Disease: Insights for Sustainable Crop Protection" Fractal and Fractional 9, no. 12: 754. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120754

APA StyleAlsulami, M., Raza, A., Lampart, M., Shafique, U., & Rezk, E. G. (2025). Fractional Modeling and Stability Analysis of Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus Disease: Insights for Sustainable Crop Protection. Fractal and Fractional, 9(12), 754. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120754