Sedimentary Paleo-Environment and Reservoir Heterogeneity of Shale Revealed by Fractal Analysis in the Inter-Platform Basin: A Case Study of Permian Shale from Outcrop of Nanpanjiang Basin

Abstract

1. Introduction

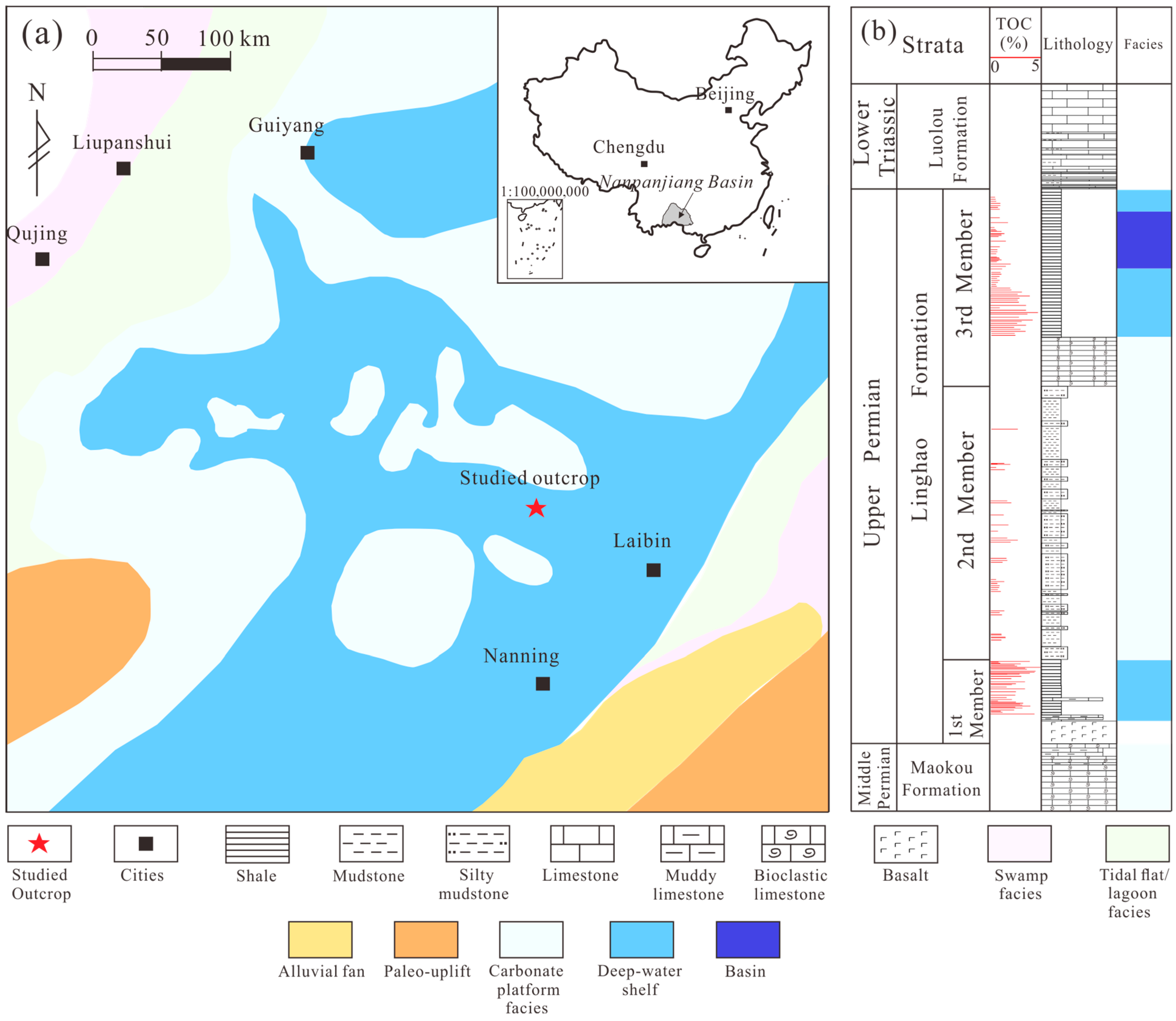

2. Geological Setting

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Sedimentary Environments Conditions

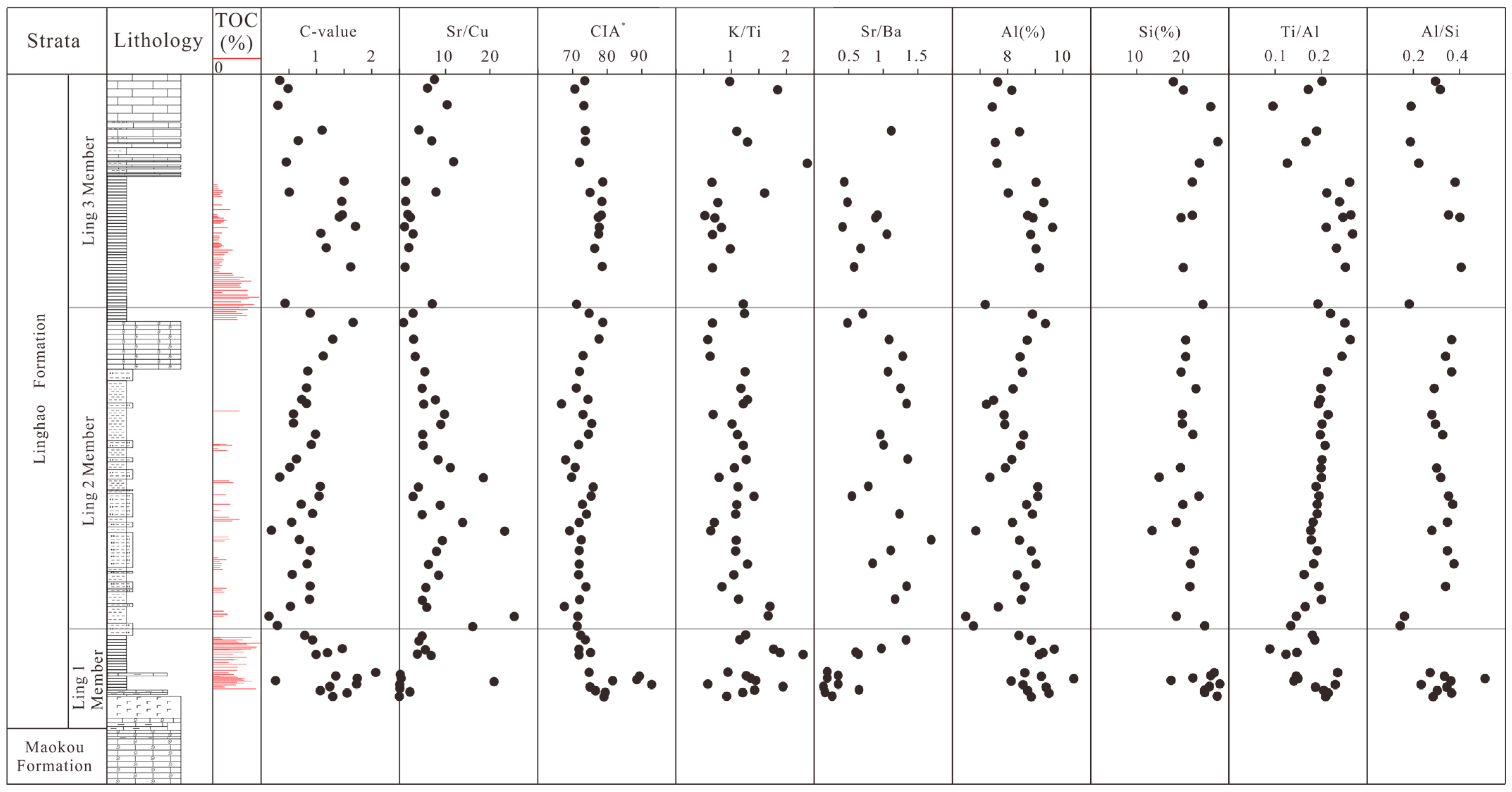

4.1.1. Paleo-Climate, Paleoweathering, and Paleosalinity

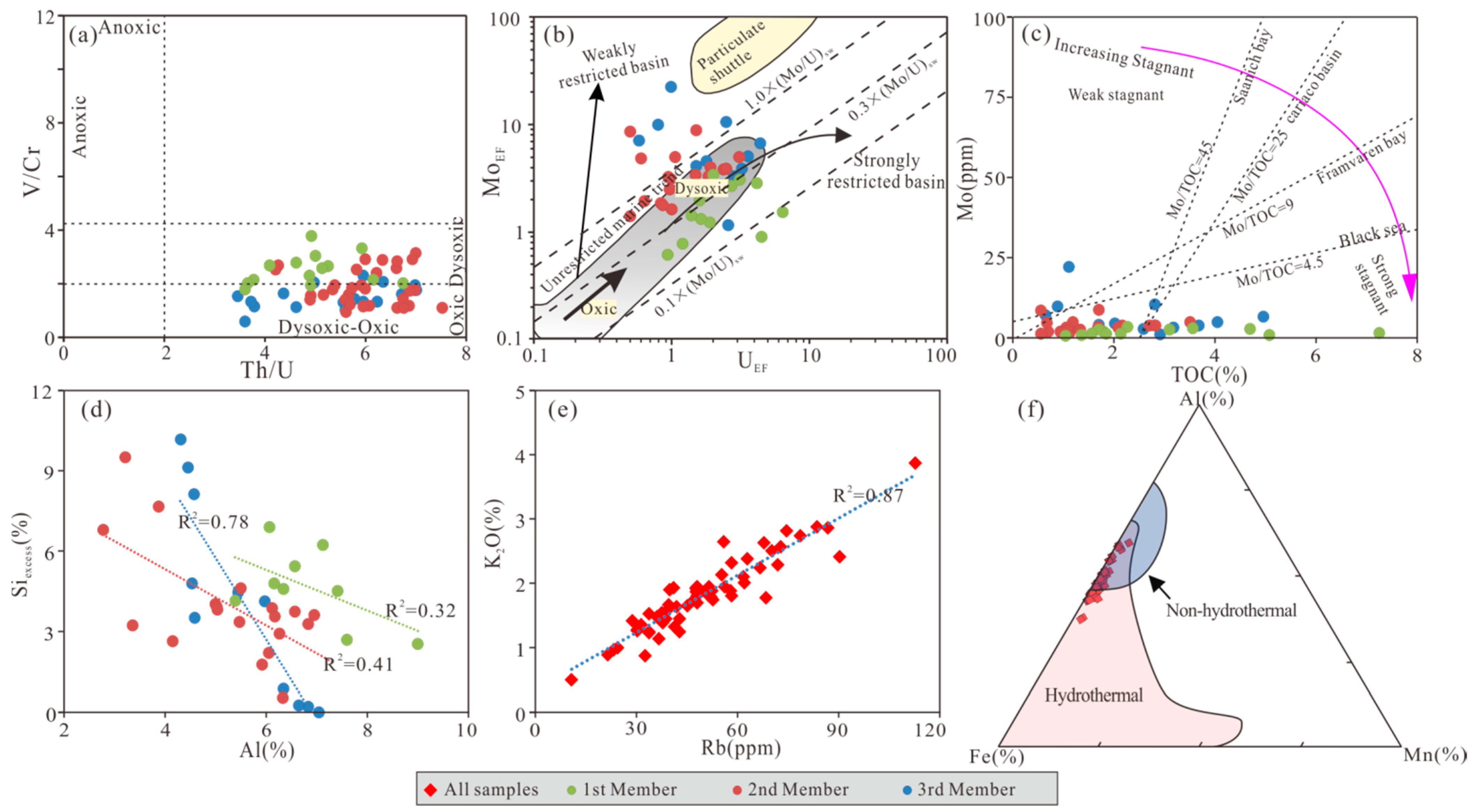

4.1.2. Input of Terrestrial Debris

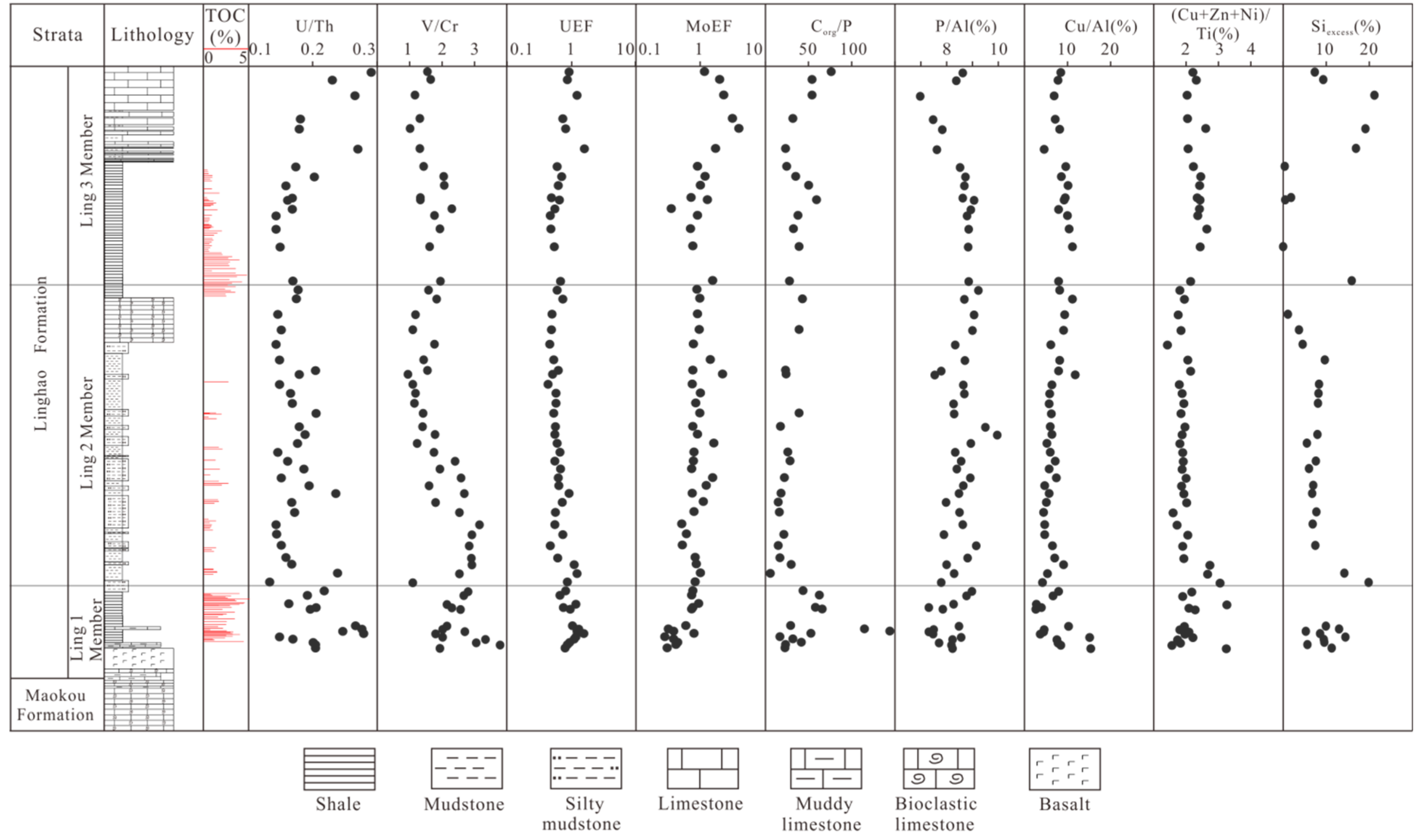

4.1.3. Paleo-Redox Conditions

4.1.4. Paleo-Productivity

4.2. Reservoir Characteristics

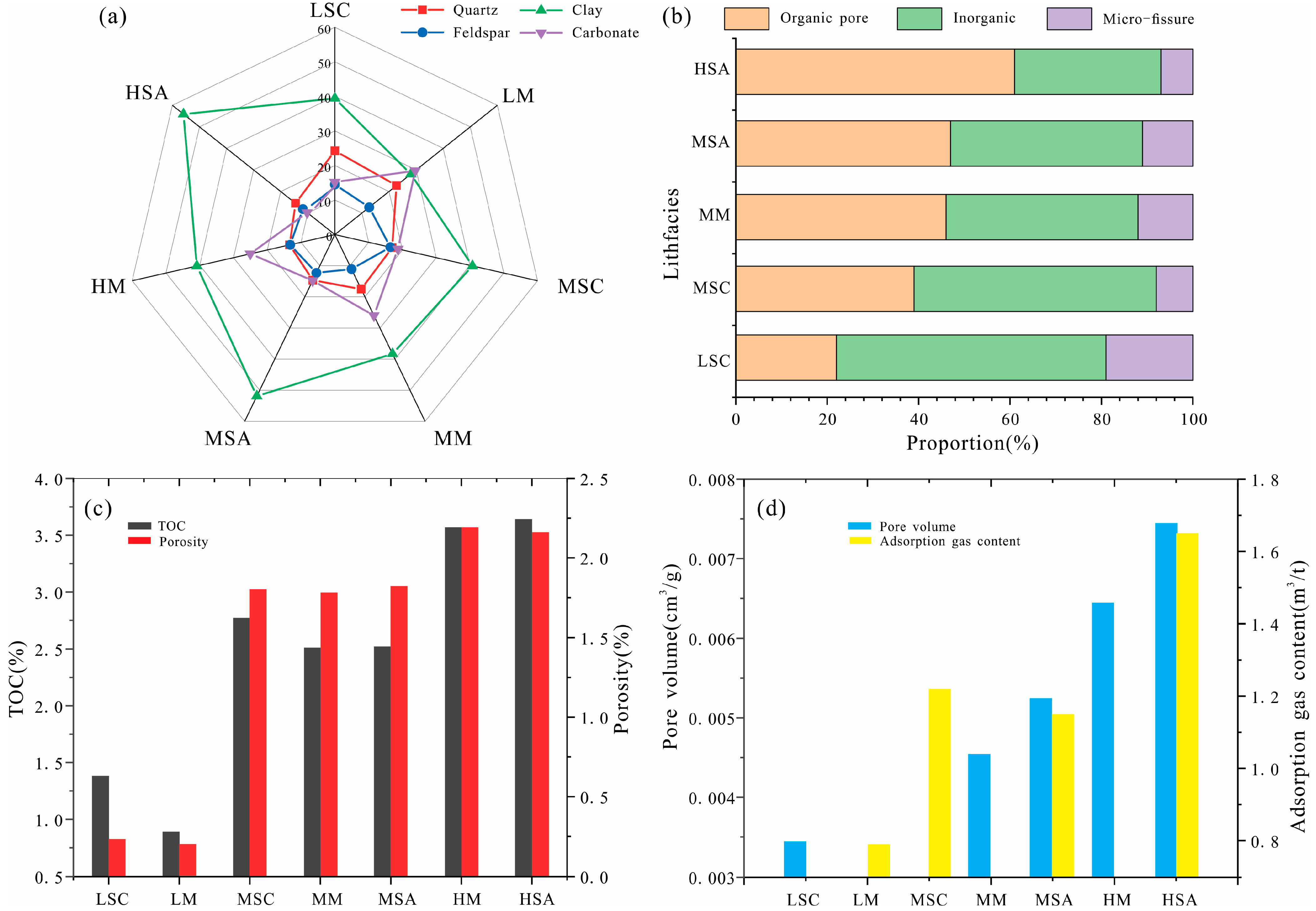

4.2.1. Shale Lithofacies Classification

4.2.2. SEM Analysis

4.2.3. Reservoir Parameter Characteristics

4.3. Reservoir Heterogeneity Characterization

4.3.1. Calculation of Fractal Dimension Based on NMR Data

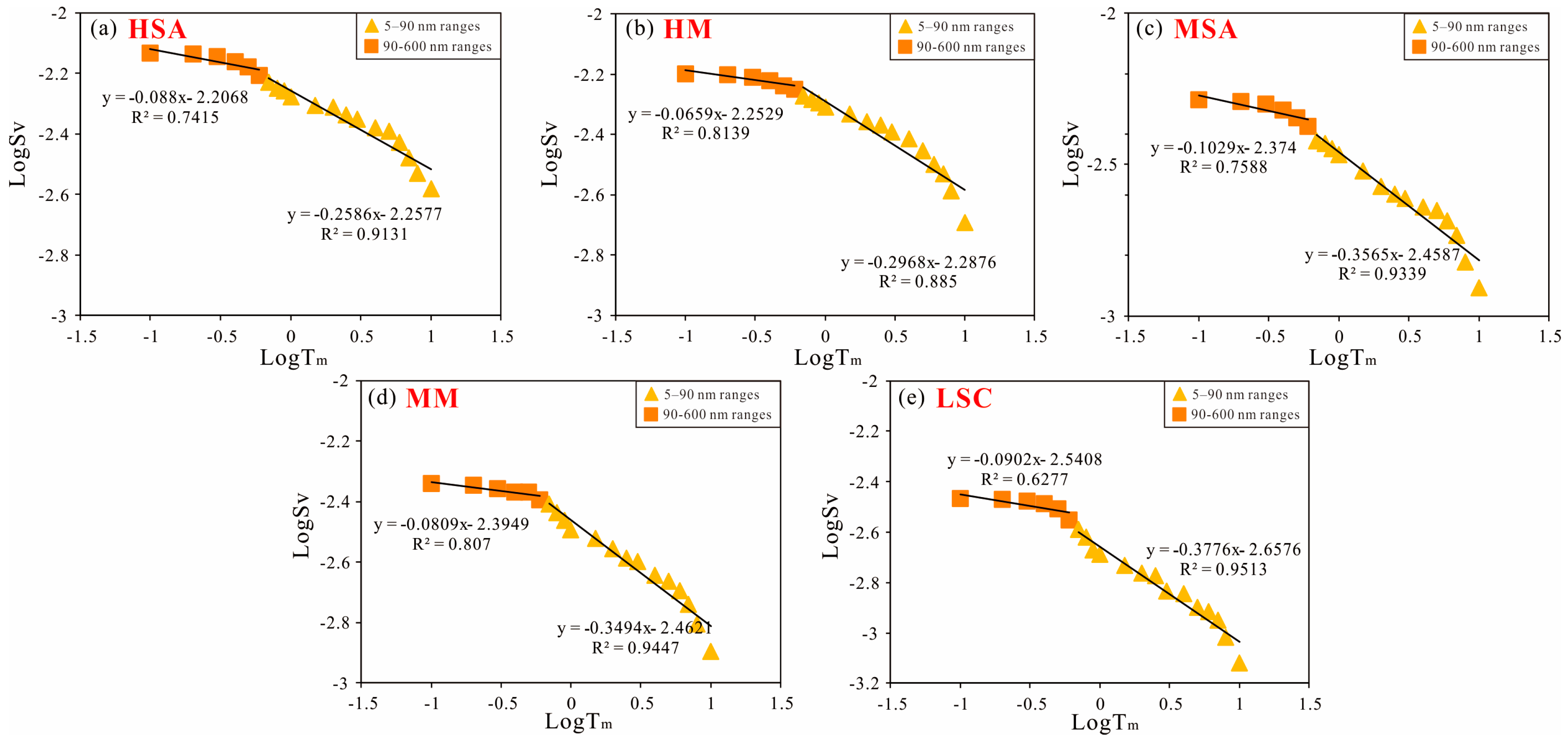

4.3.2. Fractal Dimension Based on NMRC

5. Discussion

5.1. Formation Model of Different Shale Lithofacies

5.1.1. Controlling Factors for the Organic-Rich Shale

5.1.2. Formation Model of Organic-Rich Shale

5.2. Evaluation of Shale Reservoirs with Different Lithofacies and Heterogeneity

5.2.1. Comparison of Macroscopic Parameters of Reservoirs and Influencing Factors

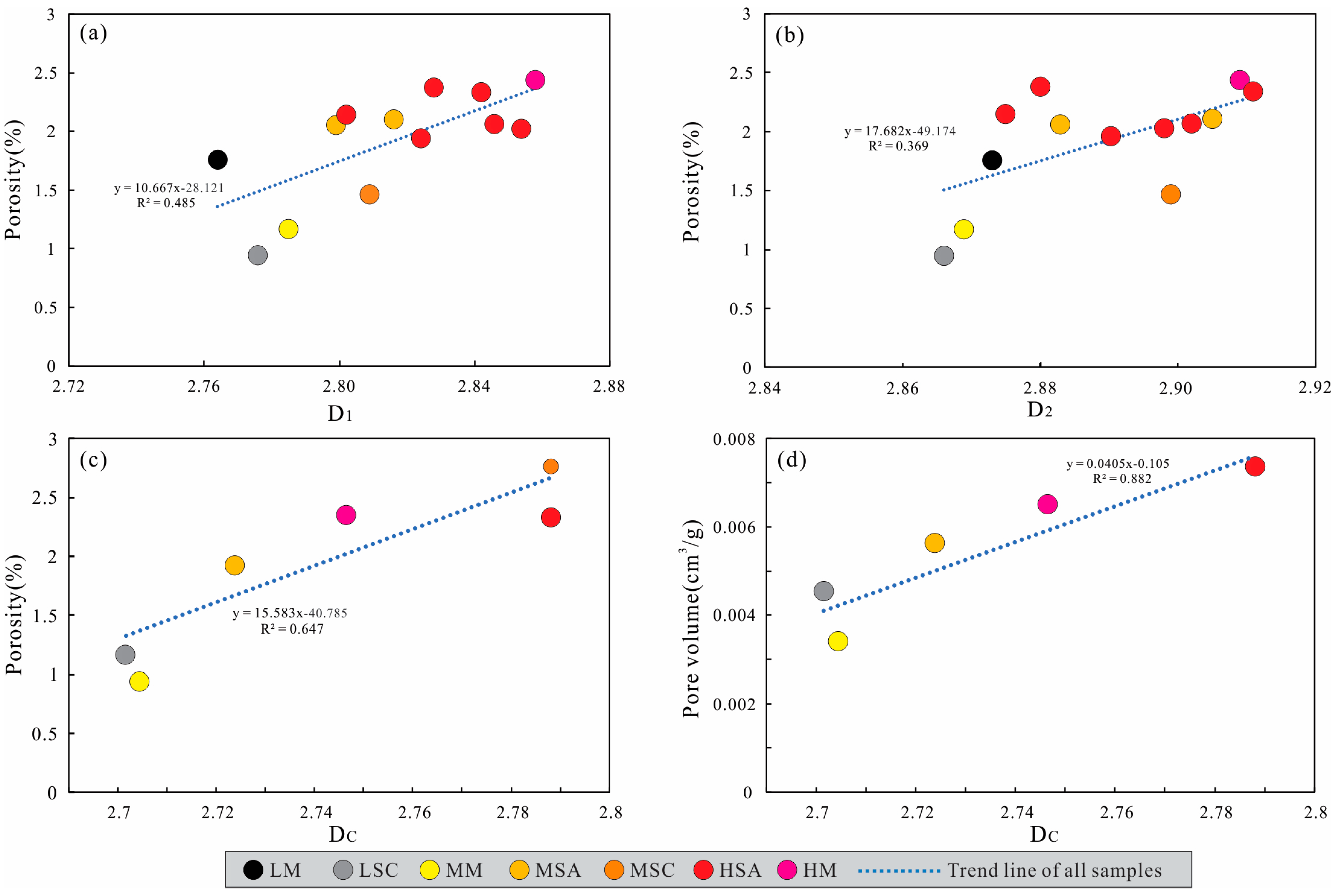

5.2.2. Relationships Between Fractal Dimension, Physical Properties, and Pore Structure

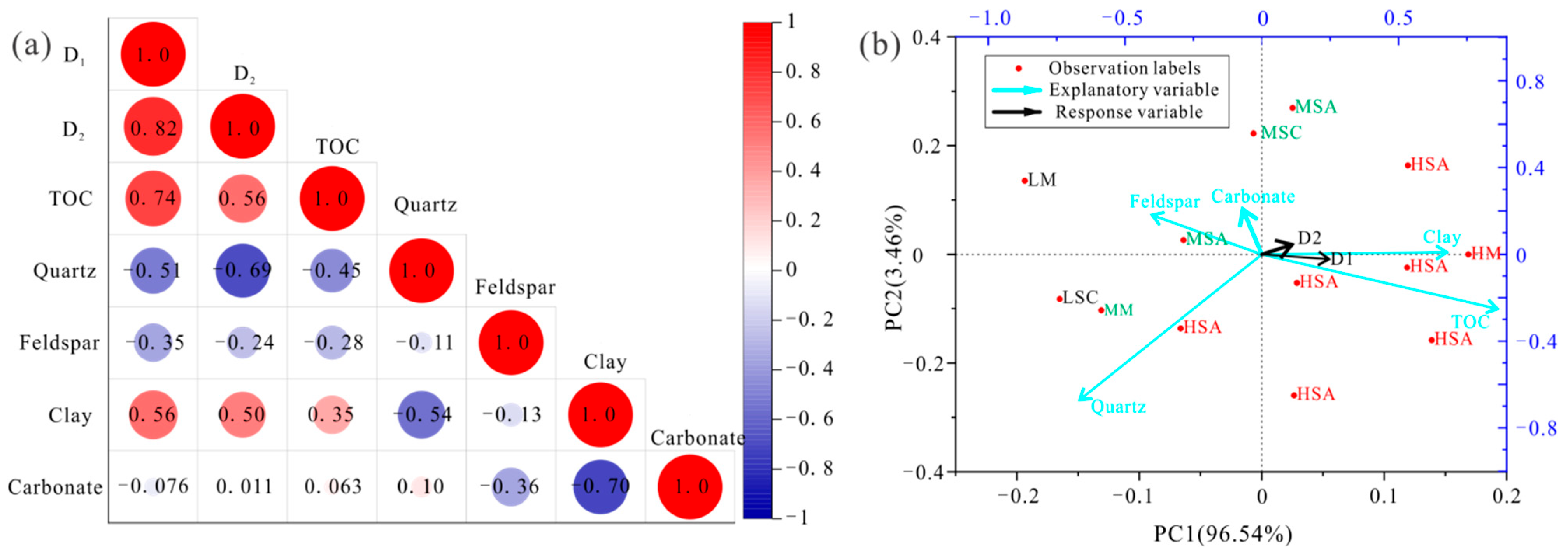

5.2.3. Influencing Factors of Fractal Dimension

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The Linghao organic-rich shale in the inter-platform basin was concentrated in the 1st Member (average 2.57%) and the lower part of the 3rd Member (average 2.88%). The high TOC shale in the 1st Member was formed in a humid environment with intense weathering, significant input of fine-grained clastic material from basin margins, high bottom-water reducibility, increased phosphorus cycling, and moderate to low productivity. The early paleo-environmental conditions of the 3rd Member were similar to those of the 1st Member, but its higher paleo-productivity and sedimentation rates significantly facilitated organic matter accumulation.

- (2)

- The inter-platform basin shale developed seven types of lithofacies. The organic-rich shale in the 1st Member mainly consisted of mixed lithofacies with medium to high carbon content, while those in the lower part of the 3rd Member were primarily composed of high-carbon silicious-bearing argillaceous lithofacies and medium-carbon silicious-bearing argillaceous lithofacies. The high-carbon lithofacies exhibited the most favorable reservoir properties, with an average porosity of 2.14%, permeability of 0.036 mD, and pore volume reaching 0.0074 g/cm3. The predicted total gas content can reach up to 3.28 m3/t, indicating that the HSA lithofacies represent the most prospective shale type in the study area.

- (3)

- Using a fractal model, this study fitted the NMR relaxation spectra and divided the fractal dimension D into D1 (T2 < T2c, indicating the fractal dimension of adsorption pores) and D2 (T2 > T2c, indicating the fractal dimension of seepage pores). D1 ranged from 2.76 to 2.86 (average 2.82), and D2 ranged from 2.87 to 2.91 (average 2.89). The higher average value of D2 suggested that the distribution of movable fluid pores in inter-platform basin shales were more complex. The fractal dimension Dc derived from NMRC varied from 2.70 to 2.79 (average 2.73), indicating a slightly lower degree of heterogeneity and pore complexity. Comparison among lithofacies revealed that both fractal models indicated higher fractal dimensions in high-carbon shale than in medium- and low-carbon lithofacies, implying that high-carbon shale possessed more complex pore structures.

- (4)

- A lithofacies development model for the Linghao Formation shale was established. The paleo-environment directly controlled the mineral composition and lithofacies types of the Linghao Formation, thereby influencing reservoir properties, gas-bearing capacity, and pore volume. High-carbon shale was characterized by higher pore volume and porosity, as well as larger fractal dimensions, indicating stronger heterogeneity. Correlation and redundancy analyses revealed that high clay mineral content and TOC were the primary factors increasing the pore heterogeneity in inter-platform basin shale. Conversely, higher feldspar and quartz content were detrimental, while carbonate minerals had a minor impact. Moreover, the heterogeneity of adsorption pores has a greater influence on the reservoir characteristics of different lithofacies.

- (5)

- This study demonstrated that fractal dimensions served as quantitative indicators of shale heterogeneity controlled by the interplay of mineral composition and TOC. Integrating fractal analysis with conventional reservoir parameters provided a novel tool for evaluating pore-scale complexity and understanding the depositional and compositional controlled on reservoir quality, offering new insights for shale gas exploration in the Permian Linghao Formation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zou, C.; Dong, D.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Cheng, K. Geological characteristics and resource potential of shale gas in China. Petrol. Explor. Dev. 2010, 37, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Tan, W.C.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Niu, P.F.; Qin, Q.R. Mineralogical and lithofacies controls on gas storage mechanisms in organic-rich marine shales. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 3846–3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Zhao, Q.; Cong, L.Z.; Wang, H.Y.; Shi, Z.S.; Wu, J.; Pan, S. Development progress, potential and prospect of shale gas in China. Nat. Gas Ind. 2021, 41, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y.; Cai, G.; Hu, D.; Wei, Z.; Liu, R.; Han, J.; Fan, Z.; Hao, J.; Jiang, Y. Geochemical and geological characterization of Upper Permian Linghao Formation shale in Nanpanjiang Basin, SW China. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 883146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Hu, D.; Wei, Z.; Liu, R.; Hao, J.; Han, J.; Fan, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Q. Sedimentology and geochemistry of the Upper Permian Linghao Formation marine shale, central Nanpanjiang Basin, SW China. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 914426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Zhang, L.; Hu, Q.; Pan, Z.; Yu, B.; Sun, L.; Bai, L.; Connell, L.D.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, G. Pore connectivity and water accessibility in Upper Permian transitional shales, southern China. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2019, 107, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Dong, T.; He, S.; Zhai, G.; Guo, X.; Hou, Y.; Yang, R.; Han, Y. Sedimentological and geochemical characterization of the Upper Permian transitional facies of the Longtan Formation, Northern Guizhou Province, Southwest China: Insights into paleo-environmental conditions and organic matter accumulation mechanisms. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2020, 118, 104446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algeo, T.J.; Maynard, J.B. Trace-element behavior and redox facies in core shales of Upper Pennsylvanian Kansas-type cyclothems. Chem. Geol. 2004, 206, 289–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweere, T.; van den Boorn, S.; Dickson, A.J.; Reichart, G.J. Definition of new trace-metal proxies for the controls on organic matter enrichment in marine sediments based on Mn, Co, Mo and Cd concentrations. Chem. Geol. 2016, 441, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Gan, Y.; Ju, Y.; Shao, C. Influence of sedimentary environment on the brittleness of coal-bearing shale: Evidence from geochemistry and micropetrology. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2020, 185, 106603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Hu, D.; Wei, Z.; Wei, X.; Liu, R.; Wang, D.; Jiang, Y. Nanoscale pore characteristics of the Jurassic Dongyuemiao Member lacustrine shale, Eastern Sichuan Basin, SW China: Insights from SEM, NMR, LTNA, and MICP experiments. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 10, 1055541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Fan, X.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Zhu, L.; Wan, C.; Chen, Z. Differential impact of clay minerals and organic matter on pore structure and its fractal characteristics of marine and continental shales in China. Appl. Clay Sci. 2022, 216, 106334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, S.; Wu, F.; Miao, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, X. Differences of marine and transitional shales in the case of dominant pore types and exploration strategies, in China. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2022, 103, 104628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Oyediran, I.A.; Huang, R.; Hu, F.; Du, T.; Hu, R.; Li, X. Study on pore structure characteristics of marine and continental shale in China. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 33, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Hou, M.; Liu, X.; Huang, S.; Chao, H.; Zhang, R.; Deng, X. Geological and geochemical characteristics of marine-continental transitional shale from the Upper Permian Longtan Formation, Northwestern Guizhou, China. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2018, 89, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wu, C.; Li, T.; Wang, H. Multiple geochemical proxies controlling the organic matter accumulation of the marine-continental transitional shale: A case study of the Upper Permian Longtan Formation, Western Guizhou, China. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2018, 56, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Q.; Dong, D.; Sun, S.S.; Hu, L.; Qi, L.; Li, C.; Chen, C.; Chen, X. Fractal characteristics of organic-rich shale pore structure and its geological implications: A case study of the Lower Silurian Longmaxi Formation in the Weiyuan block, Sichuan Basin. Nat. Gas Ind. 2024, 44, 108–118. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Guo, S.; Shi, D.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, G. Investigation of pore structure and fractal characteristics of marine continental transitional shales from Longtan Formation using MICP, gas adsorption, and NMR (Guizhou, China). Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2019, 107, 555–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zuo, Y.; Wu, Z.; Liu, H.; Xi, S.; Shui, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, R.; Lin, J. Fractal analysis of pores and the pore structure of the Lower Cambrian Niutitang shale in northern Guizhou province: Investigations using NMR, SEM and image analyses. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2019, 99, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, H.; Shang, Y.; Cui, G. Fractal characterization of the pore-throat structure in tight sandstone based on low-temperature nitrogen gas adsorption and high-pressure mercury injection. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; He, S.; Radwand, A.E.; Xie, J.T.; Qin, Q.R. Quantitative analysis of pore complexity in lacustrine organic-rich shale and comparison to marine shale: Insights from experimental tests and fractal theory. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 16171–16188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, S.; Xia, P.; Hao, F.; Tian, J.; Fu, Y.; Wang, K. Pore Fractal Characteristics between Marine and Marine–Continental Transitional Black Shales: A Case Study of Niutitang Formation and Longtan Formation. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, D.; Feng, X.; Zhao, F.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lin, R.; Du, W.; Fan, Q.; Song, Y.; et al. Heterogeneity characteristics and its controlling factors of marine shale reservoirs from the Wufeng−Longmaxi Formation in the Northern Guizhou Area. Geol. China 2024, 51, 780–798. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Han, D.; Lin, W.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Xiao, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X. Pore Structure and Fractal Characteristics of Coal-Bearing Cretaceous Nenjiang Shales from Songliao Basin, Northeast China. J. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2024, 9, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhong, B.; Yang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Xiang, J.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, H. Multiscale Fractal Evolution Mechanism of Pore Heterogeneity in Hydrocarbon Source Rocks: A Thermal Simulation Experiment in the Xiamaling Formation. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Guan, Q.; Yin, X.; Gu, Y. Pore Evolution and Fractal Characteristics of Marine Shale: A Case Study of the Silurian Longmaxi Formation Shale in the Sichuan Basin. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciążela, J. Editorial for the Special Issue “Recent Advances in Exploration Geophysics”. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Yan, Q.; Xiang, Z.; Xia, L.; Jiang, W.; Wei, W.; Li, X.; Zhou, B. Sedimentary characteristics of the Early-Middle Triassic on the South Flank of the Xilin Faulted Block in the Nanpanjiang Basin and its tectonic implications. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2018, 34, 2119–2139. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 29172-2012; Practices for Core Analysis. China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Mitchell, J.; Webber, J.B.W.; Strange, J.H. Nuclear magnetic resonance cryoporometry. Phys. Rep. 2008, 461, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, K.; Fu, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Zhang, X.; Qi, L.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, Z. Connectivity of pores in shale reservoirs and its implications for the development of shale gas: A case study of the Lower Silurian Longmaxi Formation in the southern Sichuan Basin. Nat. Gas Ind. 2019, 39, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.Y.; Zhao, J.H.; Wang, H.J.; Liao, J.D.; Liu, C.M. Distribution and application of trace elements in Junggar Basin. Nat. Gas Explor. Dev. 2007, 30, 4, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Xie, G.; Shen, Y.; Liu, S.; Hao, W. Trace and rare earth element (REE) characteristics of mudstones from Eocene Pinghu Formation and Oligocene Huagang Formation in Xihu Sag, East China Sea Basin: Implications for provenance, depositional conditions and paleoclimate. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2018, 92, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wu, S.H.; Xia, D.L.; You, X.L.; Zhang, H.M.; Lu, H. Major and trace element geochemistry of the lacustrine organic-rich shales from the Upper Triassic Chang 7 Member in the southwestern Ordos Basin, China: Implications for paleoenvironment and organic matter accumulation. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2020, 111, 852–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, H.W.; Young, G.M. Early Proterozoic climates and plate motions inferred from major element chemistry of lutites. Nature 1982, 299, 715–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.P.; Hu, G.; Cao, J.; Yang, R.F.; Liao, Z.W.; Hu, C.W.; Pang, Q.; Pang, P. Enhanced hydrological cycling and continental weathering during the Jenkyns Event in a lake system in the Sichuan Basin, China. Glob. Planet. Change 2022, 216, 103915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Algeo, T.J. Elemental proxies for paleosalinity analysis of ancient shales and mudrocks. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2020, 287, 341–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.Y.; Zhao, X.Z.; Li, J.Z.; Pu, X.G.; Tao, X.W.; Shi, Z.N.; Sun, Y.Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, R.; Lin, J. Paleoenvironmental modes and organic matter enrichment mechanisms of lacustrine shale in the Paleogene Shahejie Formation, Qikou Sag, Bohai Bay Basin. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 9046–9068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condie, K.C. Chemical composition and evolution of the upper continental crust: Contrasting results from surface samples and shales. Chem. Geol. 1993, 104, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.W.; Hu, Z.Q.; Feng, D.J.; Wang, Q.R. Sedimentology and sequence stratigraphy of lacustrine deepwater fine-grained sedimentary rocks: The Lower Jurassic Dongyuemiao Formation in the Sichuan Basin, Western China. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2022, 146, 105933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupker, M.; France-Lanord, C.; Galy, V.; Lavé, J.; Kudrass, H. Increasing chemical weathering in the Himalayan system since the Last Glacial Maximum. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2013, 365, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribovillard, N.; Algeo, T.J.; Lyons, T.; Riboulleau, A. Trace metals as paleoredox and paleoproductivity proxies: An update. Chem. Geol. 2007, 232, 12–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algeo, T.J.; Liu, J.S. A re-assessment of elemental proxies for paleoredox analysis. Chem. Geol. 2020, 540, 119549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algeo, T.J.; Ingall, E. Sedimentary Corg:P ratios, paleocean ventilation, and Phanerozoic atmospheric pO2. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2007, 256, 130–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algeo, T.J.; Lyons, T.W. Mo–total organic carbon covariation in modern anoxic marine environments: Implications for analysis of paleoredox and paleohydrographic conditions. Paleoceanography 2006, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathy, D.; Wagreich, M.; Gier, S.; Mohamed, R.S.A.; Zaki, R.; El Nady, M.M. Maastrichtian oil shale deposition on the southern Tethys margin, Egypt: Insights into greenhouse climate and paleoceanography. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2018, 505, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoepfer, S.D.; Shen, J.; Wei, H.Y.; Tyson, R.V.; Ingall, E.; Algeo, T.J. Total organic carbon, organic phosphorus, and biogenic barium fluxes as proxies for paleomarine productivity. Earth Sci. Rev. 2015, 149, 23–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Wang, C.; Liang, X.; Wang, G.; Jiang, S. Paleodepositional conditions and organic matter accumulation mechanisms in the Upper Ordovician-lower Silurian Wufeng-Longmaxi shales, Middle Yangtze region, South China. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2022, 143, 105823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yang, H.; Liu, H.; Jiao, Y. The depositional mechanism of hydrothermal chert nodules in a lacustrine environment: A case study in the middle Permian Lucaogou Formation, Junggar Basin, Northwest China. Minerals 2022, 12, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Li, Z.; Shi, W.; Yang, X.; Wang, X.; Young, S. Differential sedimentary mechanisms of Upper Ordovician-lower Silurian shale in southern Sichuan Basin, China. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2023, 148, 106040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucks, R.G.; Reed, R.M.; Ruppel, S.C.; Hammes, U. Spectrum of pore types and networks in mudrocks and a descriptive classification for matrix-related mudrock pores. AAPG Bull. 2012, 96, 1071–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Gan, H.; Luo, M.; Huang, Y. Gas-prospective area optimization for Silurian shale gas of Longmaxi Formation in southern Sichuan Basin, China. Interpretation 2015, 3, SJ49–SJ59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Weller, A. Fractal dimension of pore-space geometry of an Eocene sandstone formation. Geophysics 2014, 79, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Hu, W.; Cao, J.; Sun, F.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Z. Micro/nanoscale pore structure and fractal characteristics of tight gas sandstone: A case study from the Yuanba area, northeast Sichuan Basin, China. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2018, 98, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zheng, M.; Bi, H.; Wu, S.; Wang, X. Pore throat structure and fractal characteristics of tight oil sandstone: A case study in the Ordos Basin, China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2017, 149, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wang, R.; Shen, B.; Wang, G.; Wan, C.; Wang, Q. Geological characteristics, resource potential, and development direction of shale gas in China. Petrol. Explor. Dev. 2025, 52, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Wei, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, T.; Liu, X. Deep shale gas exploration in complex structure belt of the southeastern Sichuan Basin: Progress and breakthrough. Nat. Gas Ind. 2022, 42, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Capblancq, T.; Luu, K.; Blum, M.G.B.; Bazin, E. Evaluation of redundancy analysis to identify signatures of local adaptation: A comparison with other genome-scan methods. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2018, 18, 1223–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Lithofacies | TOC (%) | Quartz (%) | Feldspar (%) | Clay (%) | Carbonate (%) | Organic Pore | Inorganic Pore | Micro-Fracture | Porosity (%) | Permeability (mD) | Pore Volume | Adsorption Gas Content |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSC | 1.35 | 24.25 | 14.49 | 39.42 | 15.19 | 22 | 59 | 19 | 0.21 | 0.0015 | 0.0034 | |

| LM | 0.86 | 22.76 | 12.69 | 28.05 | 29.67 | 0.18 | 0.0025 | 0.78 | ||||

| MSC | 2.74 | 16.97 | 16.43 | 40.73 | 18.67 | 39 | 53 | 8 | 1.78 | 0.0022 | 1.21 | |

| MM | 2.48 | 17.54 | 11.08 | 38.32 | 26.00 | 46 | 42 | 12 | 1.76 | 0.0048 | 0.0045 | |

| MSA | 2.49 | 14.66 | 12.30 | 51.88 | 14.79 | 47 | 42 | 11 | 1.80 | 0.0023 | 0.0052 | 1.14 |

| HM | 3.54 | 13.40 | 13.25 | 40.88 | 25.05 | 2.17 | 0.0063 | 0.0064 | ||||

| HSA | 3.61 | 14.49 | 11.81 | 55.89 | 10.21 | 61 | 32 | 7 | 2.14 | 0.036 | 0.0074 | 1.64 |

| Sample No. | Lithofacies | T2C (ms) | T2 < T2c | T2 > T2c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | R2 | D2 | R2 | |||

| S1 | LSC | 7.5 | 2.78 | 0.916 | 2.87 | 0.959 |

| S2 | LM | 2.7 | 2.84 | 0.844 | 2.91 | 0.993 |

| S3 | HSA | 1.8 | 2.85 | 0.886 | 2.90 | 0.974 |

| S4 | HSA | 2.1 | 2.82 | 0.862 | 2.91 | 0.954 |

| S5 | HSA | 2.4 | 2.85 | 0.867 | 2.90 | 0.986 |

| S6 | HSA | 5.5 | 2.80 | 0.805 | 2.88 | 0.961 |

| S7 | HSA | 3.7 | 2.83 | 0.878 | 2.88 | 0.981 |

| S8 | HSA | 4.2 | 2.82 | 0.896 | 2.89 | 0.988 |

| S9 | HM | 1.7 | 2.80 | 0.912 | 2.88 | 0.993 |

| S10 | MSA | 9.2 | 2.76 | 0.899 | 2.87 | 0.968 |

| S11 | MSA | 4.5 | 2.81 | 0.875 | 2.90 | 0.943 |

| S12 | MSC | 0.9 | 2.86 | 0.897 | 2.91 | 0.963 |

| S13 | MM | 3.6 | 2.79 | 0.901 | 2.87 | 0.975 |

| Sample ID | Lithofacies | 5 nm < r < 90 nm | 90 nm < r < 600 nm | Dc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dc1 | R2 | Dc2 | R2 | |||

| S1 | LSC | 0.378 | 0.916 | 0.09 | 0.959 | 2.70 |

| S3 | HSA | 0.259 | 0.886 | 0.088 | 0.974 | 2.79 |

| S9 | HM | 0.297 | 0.862 | 0.066 | 0.954 | 2.75 |

| S10 | MSA | 0.357 | 0.867 | 0.103 | 0.986 | 2.72 |

| S13 | MM | 0.349 | 0.805 | 0.081 | 0.961 | 2.71 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, M.; Yu, X.; Liu, S.; Cheng, Y.; Guo, J.; Wang, Z.; Duan, X. Sedimentary Paleo-Environment and Reservoir Heterogeneity of Shale Revealed by Fractal Analysis in the Inter-Platform Basin: A Case Study of Permian Shale from Outcrop of Nanpanjiang Basin. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 795. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120795

Wang M, Yu X, Liu S, Cheng Y, Guo J, Wang Z, Duan X. Sedimentary Paleo-Environment and Reservoir Heterogeneity of Shale Revealed by Fractal Analysis in the Inter-Platform Basin: A Case Study of Permian Shale from Outcrop of Nanpanjiang Basin. Fractal and Fractional. 2025; 9(12):795. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120795

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Meng, Xinan Yu, Shu Liu, Yulin Cheng, Jingjing Guo, Zhanlei Wang, and Xingming Duan. 2025. "Sedimentary Paleo-Environment and Reservoir Heterogeneity of Shale Revealed by Fractal Analysis in the Inter-Platform Basin: A Case Study of Permian Shale from Outcrop of Nanpanjiang Basin" Fractal and Fractional 9, no. 12: 795. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120795

APA StyleWang, M., Yu, X., Liu, S., Cheng, Y., Guo, J., Wang, Z., & Duan, X. (2025). Sedimentary Paleo-Environment and Reservoir Heterogeneity of Shale Revealed by Fractal Analysis in the Inter-Platform Basin: A Case Study of Permian Shale from Outcrop of Nanpanjiang Basin. Fractal and Fractional, 9(12), 795. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120795