1. Introduction

This article reports the following novel findings: Under the Laplace transform, fractal operators defined on physical fractal spaces exhibit form invariance. Based on this form invariance, a set of operational rules for operator algebra can be established, thereby providing a logical foundation for the theory of fractal operators.

In recent years, we have abstracted physical fractal space through the analysis of biological structures and dynamic processes within living organisms [

1,

2,

3,

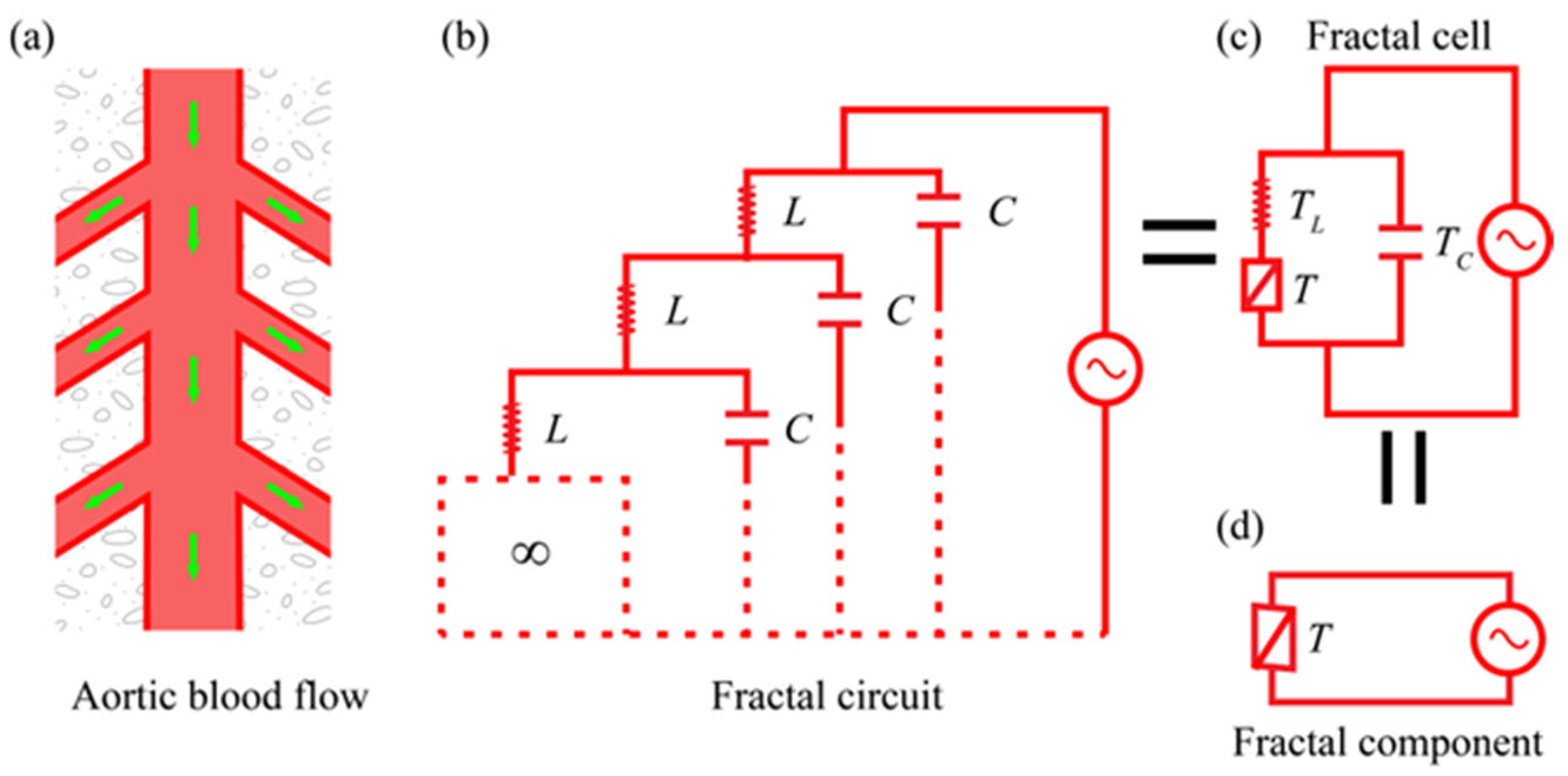

4]. Based on the physical fractal space, fractal operators can be derived, which are non-integer order operators. For example, the fractal characteristics of aortic hemodynamic images give rise to the formation of physical fractal space, as illustrated in

Figure 1. In our proposed model [

3,

4], the fractalization process primarily involves the following steps:

By leveraging the concept of infinite differentiation, the finite elastic cavity model of arterial vessels is refined into an infinite micro-elastic cavity model.

The coupled motion of the vessel wall and blood flow within this micro-elastic cavity is conceptualized as a ratchet-like mechanism—where the periodic oscillatory motion of the vessel wall is converted into unidirectional (the direction away from the heart) blood flow.

Under this ratchet mechanism, the blood flow within the micro-elastic cavity can be categorized into three distinct types. The first corresponds to axial flow along the vessel, the second refers to radial flow perpendicular to the vessel axis (as shown in

Figure 1a), and the third involves flow through branching vessels. Among these, the axial flow is governed by the inertia of the blood, while the radial flow is regulated by the elasticity of the vessel wall.

By employing the electrical–mechanical analogy method, the inertial component of axial blood flow is analogous to an inductance element L, and the elastic component of radial blood flow corresponds to a capacitance element C.

As a result, a fractal circuit is established (

Figure 1b), effectively realizing the fractalization of aortic hemodynamics.

The fractal circuit as a whole is equivalent to a fractal component (

Figure 1d). The constitutive relation of the fractal component is

where

denotes the current on the fractal element,

denotes the potential on the fractal element, and

represents the fractal admittance operator of the fractal element (or fractal circuit), which is hereinafter referred to as the fractal operator.

p is the time differential operator. In our earlier research, we employed Heaviside’s definition:

Equation (2) indicates that the differential operator

p is entirely equivalent to the time derivative

and represents a strictly localized concept. This definition of the differential operator

p, as presented in Equation (2), is also employed in the work of Courant and Hilbert [

5].

We have confirmed that within the physical fractal space, the fractal operators are the time fractional-order operators [

2]. In Equation (1), the fractal operator

is the fractional-order operator in hemodynamics. Based on the definition provided in Equation (2), we derived the following algebraic expression for the fractal operator [

3]:

where

and

are the operators corresponding to the inductance element and the capacitance element, respectively, and

represents the characteristic time of the aortic blood flow response. It is particularly noteworthy that Mikusiński, in his treatise [

6], mentioned the operator

.

The fractal operator in Equation (3) shares a characteristic with the operators found in muscle fibers and nerve fibers [

1,

2]: all of these operators are square-root-type operators involving the differential operator

p. Specifically, they function as non-rational “apparent 1/2-order fractional operators.” Since

p denotes a first-order derivative, its square root formally corresponds to a 1/2-order derivative. However, the expression under the square root in Equation (3) is not

p itself, but a more complex expression dependent on

p; hence, the term “apparent 1/2-order” is adopted. In recent years, the field of fractional calculus has experienced significant growth, with scholars exploring it from various theoretical and applied perspectives [

7,

8,

9]. However, it is difficult to provide a direct or systematic interpretation for the computation of the radical-type operator discussed above.

Our previous research has demonstrated that the “2” of the square root (i.e., the 2nd root) in Equation (3) arises from the 2-fork structure depicted in

Figure 1b, that is, the topological index 2. The same is true for the fractal operators observed in muscle and nerve fibers. In general, since the topological index governs the apparent order of the system, fractal operators

derived from diverse physical fractal structures are all inherently irrational fractional-order operators. Therefore, every study related to physical fractals will inevitably involve the computation of the irrational operator

.

However, in our previous research, the non-rational and fractional fractal operators face significant calculational challenges.

One major challenge lies in the inadequate handling of initial value conditions. Equation (2) imposes a constraint that the input signal must satisfy the zero initial value condition, which is a highly restrictive requirement. In the field of biomechanics, however, most deformations and movements do not conform to the zero initial value condition. Therefore, defining the differential operator p under non-zero initial value conditions has become a fundamental and pressing issue.

Another challenge pertains to the lack of a solid theoretical foundation for the fractal operator

. Although the fractal operator has been derived (as shown in Equation (3)), its intrinsic nature remains unclear. To enable calculation, we have directly adopted the operational calculus theories proposed by Heaviside [

10] and Mikusiński [

6]; however, the logical consistency of this approach is questionable. We could enforce the computation of

to a certain extent, while we lacked clarity regarding its mathematical nature. For instance, when considering the operator

in Equation (3) applied to a function

, it becomes highly challenging to precisely explain what the result is. Analogous situations arise in other problems of physical fractals as well. In fact, similar challenges were encountered by Heaviside [

10], as well as Courant and Hilbert [

5]. Courant and Hilbert explicitly noted in their treatise that meanings of

could not be clearly interpreted [

5].

Addressing these challenges necessitates a reconstruction of the operator theory, particularly through the introduction of new conceptual frameworks—the axiomatic approach and the principle of invariance under transformation groups.

Interestingly, the redefinition of the differential operator p is deeply related to the reconstruction of the operator theory. The redefinition of operator p provides the foundation for uncovering the invariance properties of the operator .

Historically, the theory of operator algebras originated from Heaviside’s operational calculus [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. In its early development, this theory lacked a rigorous logical foundation and therefore faced considerable criticism, although it proved effective in solving numerous practical problems [

5]. In the mid-20th century, Mikusiński [

6] constructed a more comprehensive framework for operator algebras. The central idea of his approach was that “the action of an operator on a function is equivalent to the convolution of the operator’s kernel function with the function being acted upon.” Since its introduction, the operator algebra system based on Mikusiński’s theory has been extensively studied and applied [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Courant and Hilbert’s [

5] operator theory system also shares similarities with Mikusiński’s. Nevertheless, Mikusiński’s method for determining kernel functions primarily relied on series expansions, which were cumbersome in practical applications. On the other hand, Mikusiński’s method still involved ambiguously defined concepts. As previously noted, this approach was insufficient to establish a complete logical foundation for the study of fractal operators.

In our recent study [

22], it was observed that the operator domain and the function domain following the convolution operation should be treated as two distinct entities, which exhibit a certain homomorphic relationship. This perspective contrasts significantly with Mikusiński’s approach of unifying the operator kernel function within a single domain, thereby establishing a foundational framework for the present work. Nevertheless, we believe that Jiang et al.’s [

22] logical explanation of the relationship between the operator domain and function domain remains insufficiently thorough.

This paper presents a theoretical framework for operator algebras based on the idea of invariance under transformation groups. The proposed system reformulates differential operators and operator theory, clarifies previously ambiguous concepts, ensures the consistency and coherence of operator algebra and kernel function operations, and thereby provides a solid logical foundation for both current and future research on fractal operators.

2. The Idea of Invariance Under Transformation Groups

Felix Klein’s [

23] idea of “invariance under transformation groups” [

24,

25,

26,

27], which first appeared in his inaugural lecture at the University of Erlangen, was subsequently referred to as “Erlanger Programm”. Historically, the “Erlanger Programm” has exerted a profound influence on the fields of mathematics, physics, and mechanics [

28].

The transformation groups mentioned by Klein represent a broad notion, typically encompassing various forms of continuous mathematical transformations. Klein’s idea of “invariance under transformation groups” could serve as a powerful tool for the construction of the operator theory.

We have noted that in the study of fractal operators

, the Laplace transform and its inverse have proven to be valuable tools. This paper will reveal and address the conceptual challenge behind this practicality. Traditionally, researchers have viewed the Laplace transform and its inverse primarily as analytical techniques [

29,

30]. In contrast to the traditional views, this paper places the Laplace transform and its inverse as core components of both the operator concept and the operator calculation.

Although Klein’s idea of “invariance under transformation groups” is widely applicable, few scholars have posed the following question: What form of invariance exists under the Laplace transformation group? Alternatively, what insights emerge when the Laplace transform is examined in conjunction with the principle of “invariance under transformation groups”? Remarkably, this approach proves highly effective and offers a novel pathway for defining fractal operators.

Under the Laplace transform, the original time-domain function

is converted into its corresponding image function

in the Laplace domain, that is

Generally speaking, from a mathematical perspective, the original function and the image function are two completely different functions. It is obvious that the Laplace transform always transforms one original function into another completely different image function. What we always see is “change”. That is to say, under the Laplace transform, change is the norm. Now, we go against the grain and pursue the invariance under the Laplace transform.

Our investigation begins with the derivative and integral theorems of the Laplace transform. The methodology employed is inductive in nature; specifically, a fundamental postulate starting from the integer-order derivative and integral theorems is proposed. This process constitutes

Section 3,

Section 4,

Section 5 and

Section 6. Subsequently, starting from

Section 7, the postulate serves as the foundation for constructing a comprehensive system of operator theory. The logical progression of our research mirrors the systematic approach Darwin [

31] utilized in formulating the theory of evolution.

Our strategy is not to directly analyze the fractal operator itself, but rather to consider it as a subset within the broader set of all operators. In the analysis of the mathematical properties presented in the main sections of this chapter, can represent general functional operators related to the fundamental differential operator p.

3. Invariance Under Laplace Transform from the Derivative Theorem

3.1. Invariance in the First-Order Derivative Theorem

Mikusiński [

6] introduced the function class

. A function

considered in the interval

belongs to class

if

- (i)

it has at most a finite number of points of discontinuity in every finite interval;

- (ii)

the integral has a finite value for every .

The functions discussed in this article are also confined to the class .

One of the important properties of the Laplace transform is its derivative theorem.

Under the condition that the initial value is zero, i.e., the condition that

, Equation (5) reduces to

which is extensively utilized in mechanical analysis.

However, the assumption of a zero initial value condition is a very restrictive constraint. To break this constraint, we introduce the fundamental concepts from the theory of generalized functions. Taking into account the properties of the Dirac function

, we have

and then the derivative theorem (Equation (5)) can be reformulated as follows

Equation (8) provides us with an opportunity to reshape the operator

p. The operator

p is then defined as follows:

By comparing Equation (9) and Equation (2), it becomes evident that Equation (2) is merely a special case of Equation (9). Specifically, if the function satisfies the zero initial condition, that is, if , then Equation (9) reduces to Equation (2).

Substituting Equation (9) into Equation (8) obtains that

Under non-zero initial value conditions, Equation (10) can be referred to as the “first-order derivative theorem of the fundamental operator p”.

It can be seen that, based on the definition of the operator

p provided by Equation (9), the first-order derivative theorem can be expressed in a remarkably concise form (Equation (10)). Furthermore, Equation (10) demonstrates a high degree of symmetry:

Compared to Equation (5), Equation (10) exhibits a significantly higher degree of symmetry. That is, under the Laplace transform of , the original function is transformed into the image function , and the operator p is transformed into the complex variable s without altering its form.

Equation (9) can be regarded as the standard definition of the operator p, which brings the following enlightenment:

That is to say, the operator p is a modification of the time derivative . In general, the operator p does not equate to the classical time derivative .

- 3.

The initial value affects the definition of the operator p. Such a phenomenon is exceedingly rare in the existing definitions of operators in the past.

- 4.

As previously stated, the time derivative is a strictly localized concept; however, the operator p behaves differently. The presence of the initial value breaks the localized constraint, indicating that the operator p exhibits certain non-local characteristics.

It is particularly noteworthy that the equivalent definition of Equation (9) also appears in Mikusiński’s operator theory [

6]. To ensure the commutativity of operator operations, Mikusiński introduced the following definition: If the function

has a continuous derivative

in

, then

where

is the value of the function

at

. Mikusiński had already recognized that the initial value

influences the definition of the operator

p. With regard to Equation (13), Mikusiński explicitly pointed out that

. In Mikusiński’s treatise, objects with

are functions, which follow convolution multiplication, whereas those without

are constants, which follow algebraic multiplication. However, this notation, as introduced by Mikusiński, is cumbersome and potentially ambiguous, leading to various misunderstandings. Subsequently, Luo, one of the authors of this paper, clarified the precise meaning of Equation (13) and employed the generalized function

to reformulate the definition in the following manner:

That is Equation (9). This expression provides an important insight: the logical foundation of the operator p lies in the theory of generalized functions.

In textbooks, the derivative theorem (Equation (5)) of the Laplace transform is widely recognized as a powerful tool for solving differential equations. However, this section introduces two novel fundamental functions of the derivative theorem that extend beyond its conventional usage. The first function is to reformulate the differential operator p (Equation (9)), while the second is to reveal a previously unemphasized invariant property (Equation (10)). Further invariant properties are presented in the following sections.

3.2. Invariance in the Second-Order Derivative Theorem

Furthermore, we can pay attention to the second derivative theorem of the Laplace transform:

Under the condition that the initial values are zero, i.e., when

and

, Equation (15) reduces to

This equation is extensively utilized in dynamic analysis. In the field of dynamics, the second-order time derivative is inherently associated with fundamental concepts such as acceleration and inertial force.

It is important to note that Equation (16) requires not only the function’s initial value to be zero but also the initial value of its first derivative to be zero. If the initial conditions are not met, the following approach can be adopted.

Equation (15) lacks conciseness and requires restructuring. By relocating the initial value terms from the right-hand side to the left-hand side of Equation (15) and incorporating the invariance property (Equation (10)) of the first-order derivative theorem, we derive that

Then we introduce the definition formular

Equation (18) can be considered as the standard formulation of the quadratic power operator

. It should be noted that the quadratic power operator

can be decomposed as follows:

The combination of Equations (9) and (19) could alternatively derive Equation (18).

Equation (18) exhibits that the operator

is a modification of the second-order derivative

, and the two correction terms are defined using generalized functions. By substituting Equation (18) into Equation (17), we can obtain

That is the “second-order derivative theorem of the fundamental operator p”.

It can be seen that, based on the definition of the operator

provided by Equation (18), the second-order derivative theorem can be expressed in a remarkably concise form (Equation (20)). Furthermore, Equation (20) demonstrates a high degree of symmetry:

Equation (20) exhibits the formal invariance once more, that is, under the Laplace transform of , the original function is transformed into the image function , and the operator is transformed into the complex function without altering its form.

By comparing Equation (20) with Equation (10), it can be seen that if we introduce the transformation

then Equation (10) is transformed into Equation (20).

3.3. Invariance in the nth-Order Derivative Theorem

The above invariance can be extended to the higher-order derivative theorem:

Under the zero initial value conditions that

,

,

, and

, Equation (21) reduces into

Certainly, the requirement that the initial values of all orders of derivatives of a function are zero constitutes a highly stringent condition, which is generally difficult to satisfy by functions.

By relocating the initial value term from the right-hand side to the left-hand side of Equation (21), we obtain that

Then we introduce the definition formular

Substituting Equation (24) into Equation (23) obtains that

That is the “nth-order derivative theorem of the fundamental operator p”.

It can be seen that, based on the definition of the operator provided by Equation (24), the nth-order derivative theorem can be expressed in a remarkably concise form (Equation (25)).

From the first-order derivative theorem to the

nth-order derivative theorem, we have observed a remarkable symmetry or invariance:

That is, the nth power operator on the left-hand side of Equation (25) always corresponds to the nth power of the complex variable s on the right-hand side. Apparently, and are formally identical as “power functions”.

Equation (25) can also be interpreted in the following formal manner: Under the Laplace transform, the original function on the left-hand side is transformed into the image function on the right-hand side, and the nth power operator on the left-hand side is transformed into the nth power of the complex variable s on the right-hand side without altering its form.

It can be observed that the classical concept of time derivatives, , , …, , are all localized concepts. Clearly, they are not “well-behaved” concepts, which means that under the Laplace transform, these concepts do not exhibit form invariance.

In contrast, the aforementioned power operator concepts, , , …, , are all non-localized concepts. Obviously, they are all “well-behaved” concepts, which refers to the property that under the Laplace transform, these concepts exhibit a high degree of form invariance.

It should be noted that in the above analysis, the power operator

requires

. At the end of this section, let us examine a special case. If there is

in Equation (25), then we obtain

i.e.,

That is the Laplace Transform in Equation (4). It can be seen that the Laplace transform becomes a specific case of the nth-order derivative theorem of the operator p when .

4. Invariance of Polynomial-Type Operators Under the Laplace Transform Group

We introduce the

nth power polynomial-type operator

:

where

is a combination of integer-order power operators and therefore remains an integer-order operator. It can be mathematically derived that

In the operation of Equation (29), the order of the integral transformation

and the summation operation

was interchanged. Since the number of terms

n of the polynomial is finite, the commutativity of the above operation sequence is valid. Note that

we can derive that

where

is a polynomial function defined on the complex plane. Notably, under the Laplace transform, the polynomial-type operator

and the polynomial function

on the complex plane exhibit identical mathematical forms and demonstrate the following elegant symmetry:

5. Invariance of the Integral Operator Under the Laplace Transform Group

The previous analysis primarily focused on the invariance of the differential operators (i.e., the positive-integer-power operators) under the Laplace transform. This section extends the discussion to the invariance of the integral operators (i.e., the negative-integer-power operators) under the Laplace transformation.

In addition to the derivative theorem, the Laplace transform also has the integral theorem. Once the differential operator

p is defined, the integral operator can be defined as

. According to the integral theorem of the Laplace transform, we can obtain that

Equation (32) is an equivalent form of the Laplace transform integral theorem, and the property of invariance is explicitly evident. Similarly, we can obtain

Consider operator polynomials of the following form:

Since

is an integral operator,

is also a polynomial-type integral operator, whose Laplace transform function is:

Similarly to Equation (31), we can derive that

i.e.,

6. The Formal Invariance Postulate Under the Laplace Transform Group

All the operators in

Section 3,

Section 4 and

Section 5 are integer-order operators. Next, we attempt to extend the symmetry of integer-order operators to fractional-order operators.

Specifically, we propose the postulate of “formal invariance of operators under the Laplace transform group”:

Postulate 1. The function-type operator defined on the operator domain and the image function on the Laplace domain exhibit complete consistency in their mathematical forms under the action of the Laplace transform group, i.e.,

The symbol “” in Equation (38) signifies that not only are the left and right sides equal in, but also that the left-hand side is defined through the right-hand side. The definitional formular indicates that under the Laplace transform of , the original function is transformed into the image function , and the operator is transformed into the complex function without altering its form. In other words, by simply replacing the parameter operator p in the operator with the complex variable s, we can obtain the corresponding complex function .

Through this definitional formula (38), both the connotation and denotation of the operator are established. In fact, Equation (38) does not directly provide the meaning of the operator , but it stipulates the invariance of the operator , thereby indirectly defining .

It is important to note that the postulate does not make a distinction between integer-order and fractional-order operators. Therefore, the postulate applies universally to all types of operators, including fractal operators, non-rational operators, and fractional operators.

We refer to Equation (38) as a postulate because we hold the view that such invariance must be a mathematical necessity. Since the postulate is derived from the previous conclusions by the method of induction, the reliability of the postulate has been supported by the previous sections. In present, we accept it as a “fact”.

Invariance is also symmetry. The postulate (Equation (38)) stipulates the form invariance of the operator , from which novel invariant properties of can be derived. The postulate defines a specific type of symmetry, through which additional symmetric properties can be uncovered.

7. The Kernel Function of the Operator

Based on the postulate (Equation (38)), a series of propositions can be logically deduced, thereby enabling the construction of a comprehensive system of operator theory.

In Equation (38), if the original function

is taken as the Dirac function

, then there is:

Thus, Equation (38) yields that

This equation is a corollary of the postulate (Equation (38)), or alternatively, Equation (40) is a special case of the postulate (Equation (38)).

Equation (40) is valid for all types of operators, including fractal operators, non-rational operators, and fractional operators. Then consider the inverse Laplace transform of Equation (40),

where

is the inverse Laplace transform.

is termed the kernel function of the operator

. Equation (41) is already familiar to us, previously derived during our study of fractal operators. Equation (41) can be formally regarded as the definition of the kernel function

for the operator

, and this definition is applicable to all types of operators, including fractal operators, irrational operators, and fractional-order operators.

Equations (40) and (41) demonstrate a one-to-one correspondence between the operator and its kernel function . Specifically, given the operator , applying the inverse Laplace transform (as shown in Equation (41)) results in the corresponding kernel function . Conversely, given the kernel function , applying the Laplace transform (as shown in Equation (40)) results in the operator .

The above proposition can be further generalized: a complex function in the Laplace domain always corresponds to an operator that maintains the same apparent mathematical form.

Equations (40) and (41) describe the most fundamental intrinsic properties of the operator under both non-zero and zero initial conditions. Therefore, we propose the following: if the basic operator p is properly defined, the apparent forms of the property of the operator remain consistent under both zero and non-zero initial conditions.

8. The Convolution Theorem of the Kernel Function

Based on the postulate (Equation (38)), the following significant result can be derived. Perform the inverse Laplace transform on both sides of Equation (40):

Substituting Equations (41) and (44) into Equation (43), the convolution theorem of the operator can be obtained, that is

where

is the convolution of the two functions. The convolution theorem associated with operator

clearly elucidates the fundamental nature of the operator: the action of the operator

on a function

can be expressed as the product of

and

, which is equivalent to the convolution of the kernel function

with the given function

. Equation (45) is valid for all types of operators, including fractal operators, irrational operators, and fractional-order operators.

Equation (45) used to be introduced in Mikusiński’s treatise “Operational Calculus” [

6], where he defined the operator

based on Equation (45) and considered the equation as the logical cornerstone of operator theory. In contrast, within the context of this paper, Equation (45) is derived as a theorem from the postulate (Equation (38)).

Equation (45) is equivalent with the postulate (Equation (38)). Performing the Laplace transform on both sides of Equation (45) obtains that

That is Equation (38).

The postulate (Equation (38)) and Mikusiński’s definition formula (45) are mutually necessary and sufficient conditions. Specifically, Mikusiński’s definition formula (45) can be derived by applying the inverse Laplace transform to the postulate (Equation (38)); conversely, the postulate (Equation (38)) can be obtained by performing the Laplace transform on formula (45). Therefore, these two expressions can also be described as having a “mutually inverse relationship” or “dual relationship.”

Although Equations (38) and (45) are mutually inverse, certain distinctions between them are noteworthy. At first glance, Equation (38) appears more concise. In transitioning from the left-hand side to the right-hand side of Equation (38), no new symbols are introduced. The fewer symbols used, the greater the perceived simplicity, and consequently, the more convenient the formula is for practical applications.

The postulate (Equation (38)) introduces the concept of form invariance, constituting the most fundamental type of invariance. All other forms of invariance, which are less fundamental, can be derived from this primary principle. Furthermore, the expression in Equation (38) exhibits a higher degree of symmetry. Greater symmetry not only enhances the simplicity of the form but also contributes to the simplicity of the logic.

Mikusiński’s definition formula (45) is primarily intended to clarify the connotation and denotation of the operator . However, this formula introduces a kernel function that requires separate definition. This introduces a certain degree of logical inconsistency and diminishes its practical convenience. Therefore, it is recommended that Equation (38) be adopted as the preferred definition formula for the operator.

Based on the above analysis, the meaning of the following irrational operators can be clearly elucidated. The 1/2-order integral operator is

defined by the postulate (Equation (38)), that is

Performing the inverse Laplace transformation gets

For the non-integer

satisfying

, it can be derived by the postulate (Equation (38)) that

Then performing the inverse Laplace transformation gets

To the Fractional integral operators in exponential form, it can be derived by the postulate that

Performing the Laplace transformation gets

It should be noted that, historically, Courant and Hilbert [

10] maintained that the meaning of

could not be adequately explained. Indeed, within the classical theory of operational calculus, the interpretation of

posed significant difficulties, and the more complex

was even less amenable to clear explanation. However, with the aid of the proposed postulate, previously uninterpretable irrational operators can now be rigorously defined and clearly understood.

9. The Operator Algebra Induced by the Postulate

The postulate (Equation (38)) is so powerful that it can conveniently derive the algebraic operation rules on the operator domain. The rule governing the addition operation of operators is as follows:

where

are

constants. Equation (53) demonstrates that the operations of summation and Laplace transformation are commutative in order.

Operator multiplication satisfies the commutative and associative laws:

The inverse Laplace transform of Equation (54) gives that

Equation (55) demonstrates that the product of two operators entirely corresponds the convolution of their corresponding kernel functions.

Equations (54) and (55) can lead to a series of theorems. By introducing the inverse operator, if two operators

and

are inverses of each other, that is, the product of the two operators

and

is the identity operator 1, i.e.,

then Equation (54) gives that

Equation (57) gives that if two operators

and

are inverses of each other, then their corresponding image functions

and

are also inverses of each other. Meanwhile, Equation (55) gives that

That is, if two operators and are inverses of each other, then their corresponding kernel functions and are duals.

If two operators

and

are equal to each other, that is,

then, from Equation (54), the quadratic power operator can be defined, and the operation rules of the power operator can be established:

From Equation (55) we get

where

is termed the second-order self-convolution, i.e.,

Equation (62) is precisely the expression derived by Luo et al. [

32].

Based on Equations (54) and (55), the power operation rules of the

nth power operator can be further derived as follows:

where the operation result of

times self-convolution of the kernel function

with itself is called the

nth-order self-convolution of

, i.e.,

Equations (63)–(65) are also expressions used to be derived by Luo et al. [

32].

From this, we can see the power of the axiomatic approach: based on a single postulate (Equation (38)), the previously scattered research results can be perfectly unified into a unified and systematic whole.

10. Application to the Fractal Operator of the Arterial Blood Flow

By utilizing the operator theory framework established previously, we can systematically interpret and compute the fractal operator associated with arterial blood flow, as presented in Equation (3).

When the sign

in Equation (3) is taken as positive, the operator in the equation is

According to Equation (41), which is derived by the postulate (Equation (38)), it can be obtained that the kernel function of this operator is

where

is the first-order Bessel function. Thus, based on Equations (1) and (45), the calculation formula for the arterial blood flow rate is given by

where

and

are the current and voltage of the physical fractal circuit in

Figure 1, simulating the flow rate and the blood pressure, respectively.

is the characteristic time, where the inductance

L and capacitance

C are, respectively, used to simulate the inertia of blood flow and the elasticity of the vessel wall.

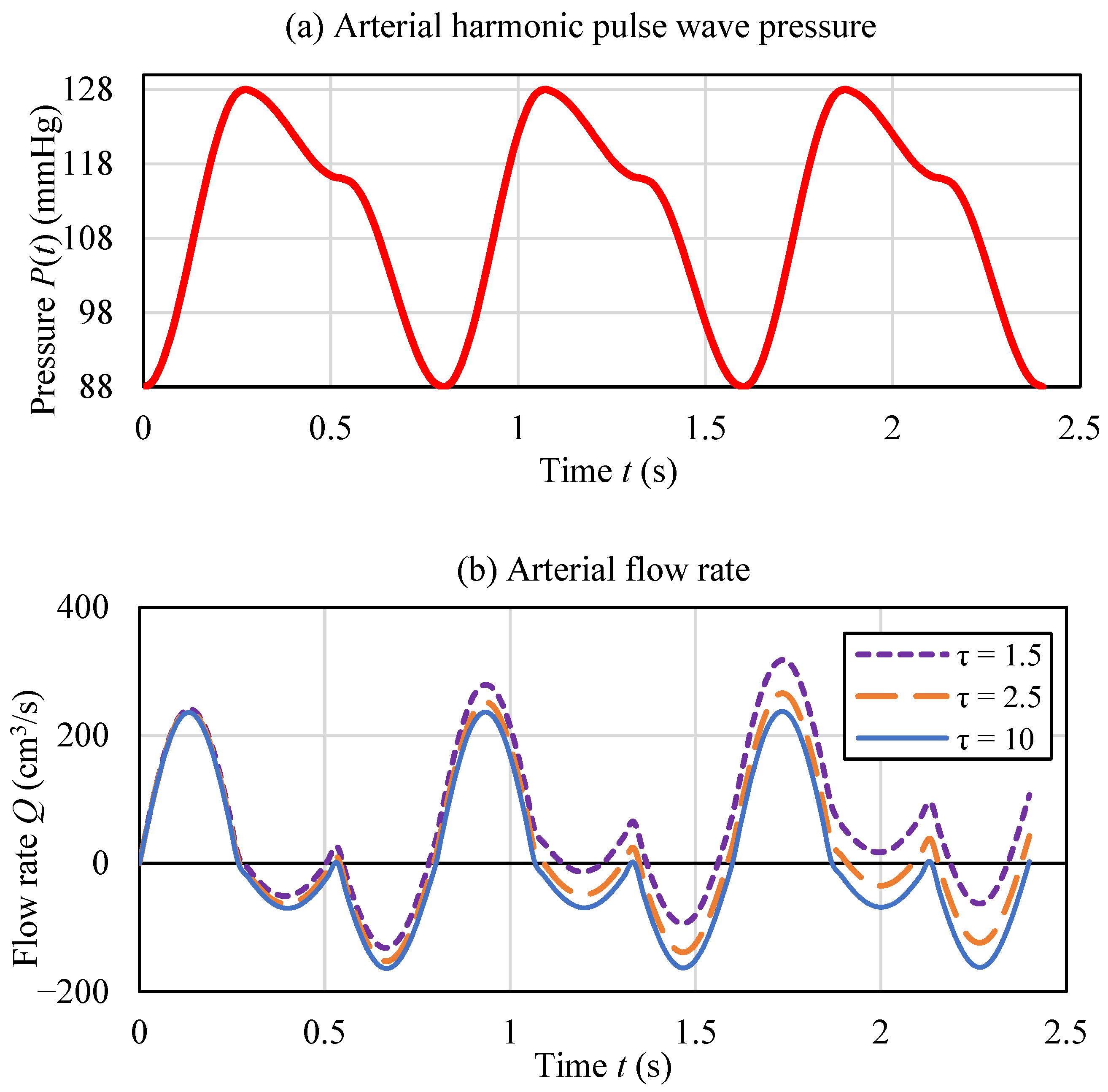

The Bessel function is incorporated into the kernel function and serves to modulate blood flow dynamics. Based on Equation (68), the computed arterial blood flow profiles are presented in

Figure 2b. In the numerical computation, we let

. The aortic blood pressure data depicted in

Figure 2a are sourced from reference [

33]. The expression of the blood pressure of

Figure 2a is

where the constants are

,

,

and

.

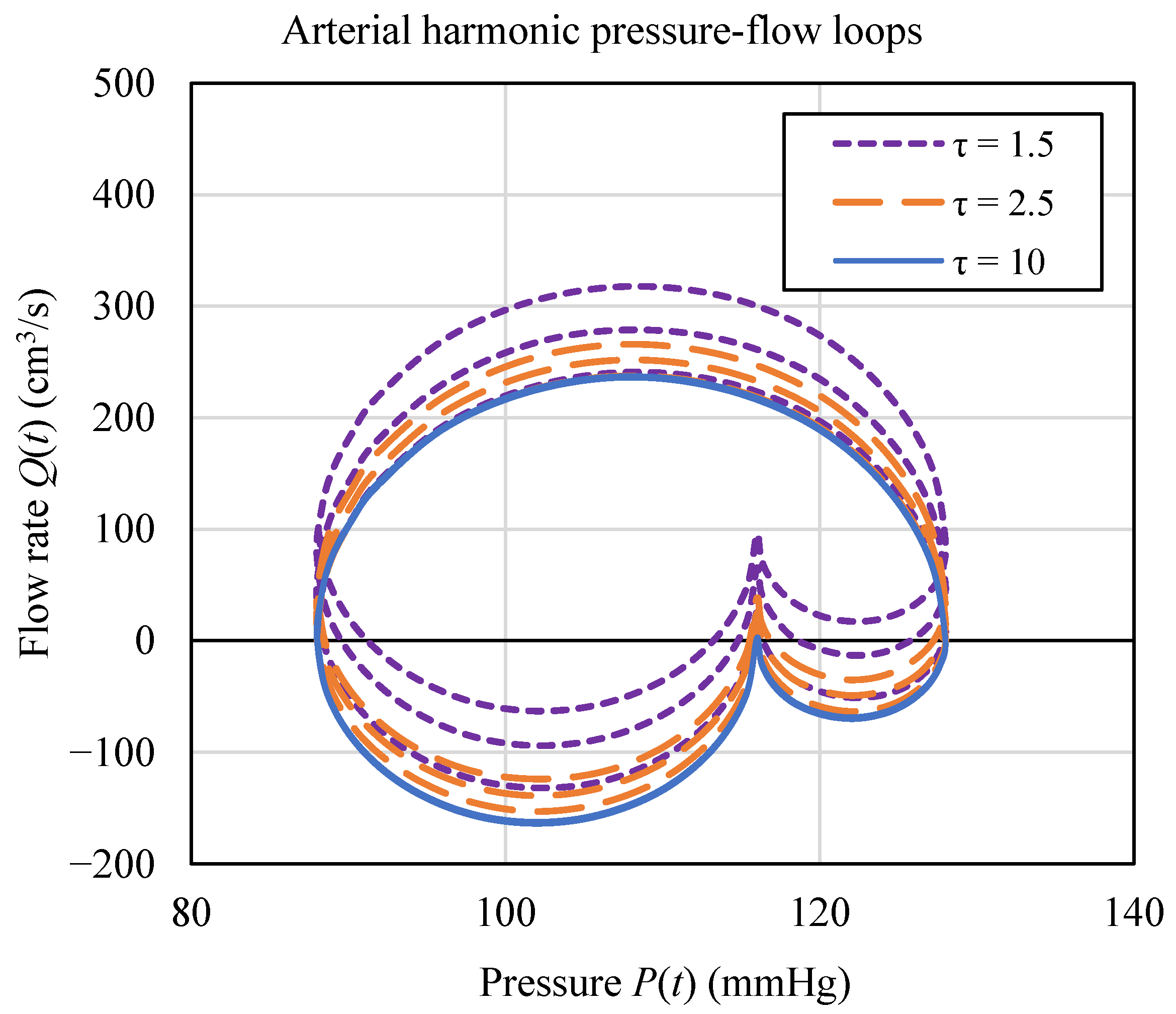

If we use the horizontal axis to represent blood pressure and the vertical axis to represent blood flow rate, the data shown in

Figure 2 can also be plotted as in

Figure 3.

As illustrated in

Figure 2b and

Figure 3, blood flow decreases with increasing characteristic time, indicating that, under constant vascular wall elasticity, greater blood inertia results in reduced flow.

Following the calculations, the physical fractal circuit model of arterial blood flow yields simulation results that capture the hysteresis loop phenomenon in hemodynamics—specifically, a phase difference between the peak values of blood flow rate and blood pressure (

Figure 2b), as well as the formation of a closed-loop pattern in the blood flow–blood pressure relationship graph (

Figure 3). This hysteresis behavior aligns with the experimentally observed hemodynamic data reported in reference [

34] and the simulated results in reference [

35]. The presence of negative blood flow values in

Figure 2b and

Figure 3 corresponds to the physiological phenomenon of blood reflux, consistent with the signals measured in reference [

36]. These results validate the effectiveness of the proposed physical fractal circuit and support the theoretical correctness of the operator framework based on the underlying postulate.

In reference [

3], Peng et al. employed the series expansion method within Mikusiński’s operational calculus to compute the operator and derived corresponding arterial blood flow profiles. It can be seen that although different methods were adopted, the main characteristics of the blood flow rate reflected by the calculation results of this paper are consistent with those of Peng et al. [

3]. Compared to the method used by Peng et al. [

3], the approach presented in this paper demonstrates two distinct advantages. First, the derivation of the operator kernel function in this work is significantly more straightforward, whereas the procedure adopted by Peng et al. [

3] involves considerable computational complexity. Second, the interpretation of operators and kernel functions in this study is conceptually clearer than that within the Mikusiński framework. Furthermore, the method based on inverse Laplace transformation offers greater universality and can be readily extended to analyze various types of operators, such as the dual fractal operators discussed in the subsequent section.

11. Application to Dual Fractal Operators

Zhou et al. [

4] previously investigated a pair of symmetrical fractal operators

and

, which are discussed as follows:

The symmetry between Equations (70) and (71) is evident. By substituting “” with “”, the fractal operator represented in Equation (70) can be converted into its corresponding symmetric operator shown in Equation (71), and vice versa.

According to the postulate (Equation (38)), the Laplace domain image functions

and

corresponding to the fractal operators

and

are given as follows:

Equations (72) and (73) are derived from the postulate (Equation (38)). In fact, by substituting “” with “”, the image function (Equation (72)) can be transformed into its symmetric counterpart (Equation (73)), and conversely, Equation (73) can also be transformed back into Equation (72).

According to Equation (41), the symmetrical kernel functions

and

of operators

and

are

Equations (74) and (75) are also guaranteed by the postulate (Equation (38)). In fact, by substituting “” with “”, the kernel functions (Equation (74)) can be transformed into its symmetric counterpart (Equation (75)), and conversely, Equation (75) can also be transformed back into Equation (74).

It should be noted that the kernel function , i.e., , consists of the first-order Bessel function and the negative power exponential function. Similarly, the symmetric kernel function , i.e., , is composed of the modified first-order Bessel function and the negative power exponential function. The symmetry observed between the kernel functions and corresponds to the symmetry between the Bessel function and the modified Bessel function.

The symmetry in the two sets of expressions is a natural consequence of the axiomatic operator theory. Indeed, this symmetry is inherently consistent: through the introduction of a complex transformation , one set of expressions can be directly derived from the other, thereby providing indirect evidence that the validity of the postulate is preserved.

12. Conclusions

The central focus of this article is the postulate (Equation (38)), specifically, the form invariance of the operator under the Laplace transform, which has been derived from the properties of integer-order operators. Based on this postulate, a rigorous and practically applicable operator framework has been systematically developed, enabling the generalization from rational to irrational operators. The validity of the resulting operator system strongly supports the hypothesis that the form invariance of under the Laplace transform reflects an intrinsic and objective characteristic, thereby directly revealing the fundamental nature of the operator .

A rigorous definition of the operator p is logically essential, and its foundation lies in the derivative and integral theorems of the Laplace transform. Indeed, only after the operator p has been precisely defined can the inductive derivation of the invariance postulate proceed in a logically sound manner.

It is worth noting that when Mikusiński introduced the concept of the operator, he did not explicitly define what the operator “is”; instead, he started from what the operator “is not”—“considering the ratio of two functions and , i.e., , if it is not a function, then it is an operator”. From the perspective of transformation , Mikusiński’s definition is formally acceptable but logically ambiguous. In contrast, the axiomatic definition presented in this paper offers a clear and logically coherent characterization of the operator: the quantity that remains invariant in form under the Laplace transform is, by definition, the operator.

In addition to elucidating the nature of the operator, the postulate (Equation (38)) enables the systematic derivation of its algebraic operational rules, thereby significantly streamlining the analytical framework of the original research methodology. In prior studies on physical fractal spaces, the absence of a formal operator theory necessitated an indirect quantitative approach: the core concept of the fractal operator was addressed through complex series expansions to approximate the corresponding kernel function. This limitation severely constrained the method’s practicality and generalizability. With the establishment of the postulate, however, the derived operator system now allows for a direct and efficient computation of the fractal operator’s kernel function, yielding results that are both mathematically rigorous and consistent with observed physical phenomena, such as the hysteresis loop effect in blood flow dynamics.