Fractional-Order Stress Relaxation Model for Unsaturated Reticulated Red Clay Slope Instability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory of Fractional Calculus

- (1)

- Riemann–Liouville definition

- (2)

- Caputo definition

- (3)

- Grünwald–Letnikov definition

3. Materials and Methods

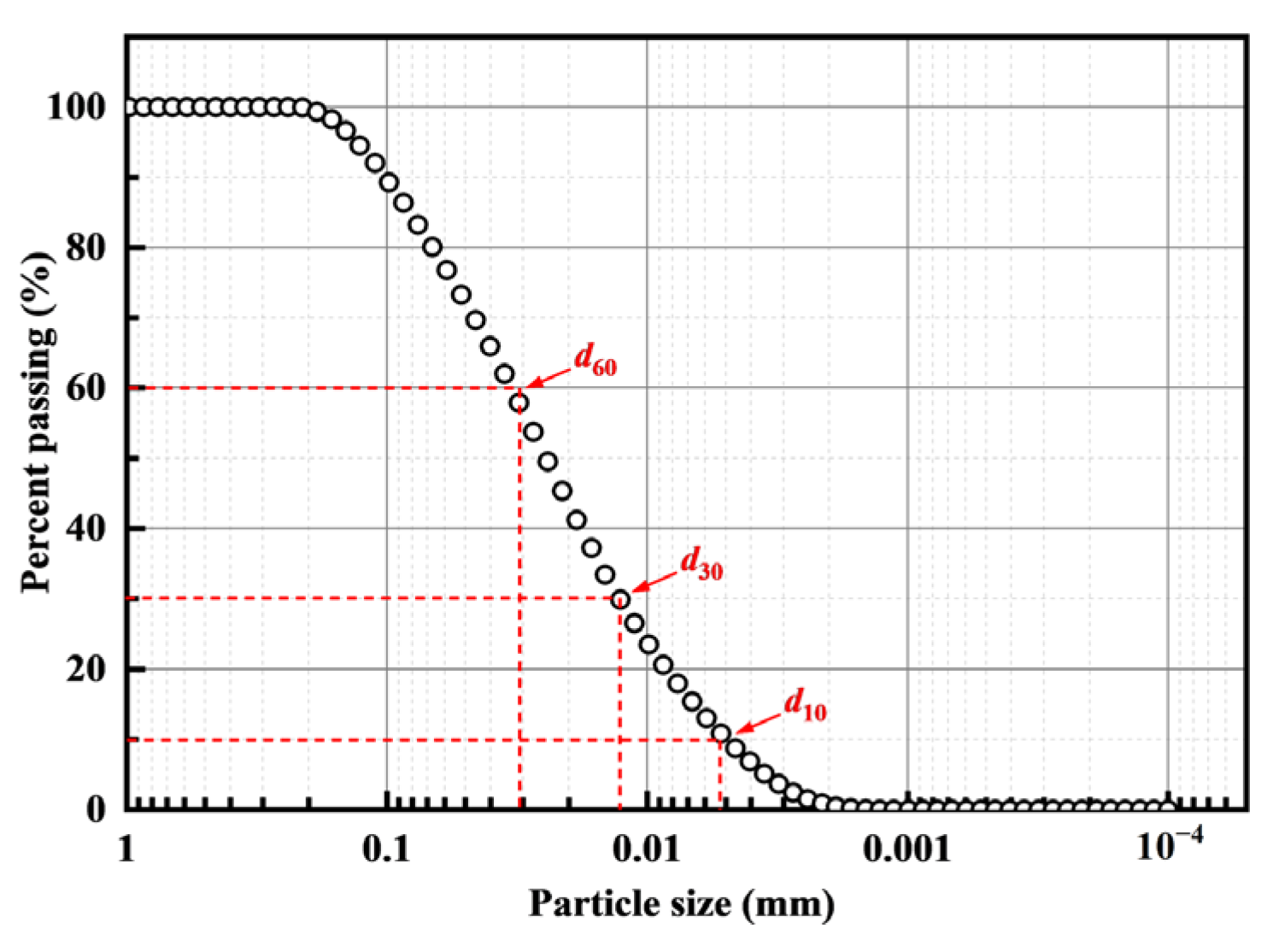

3.1. Materials

3.2. Specimen Preparation

3.3. Experiment Procedures

4. Results and Discussion

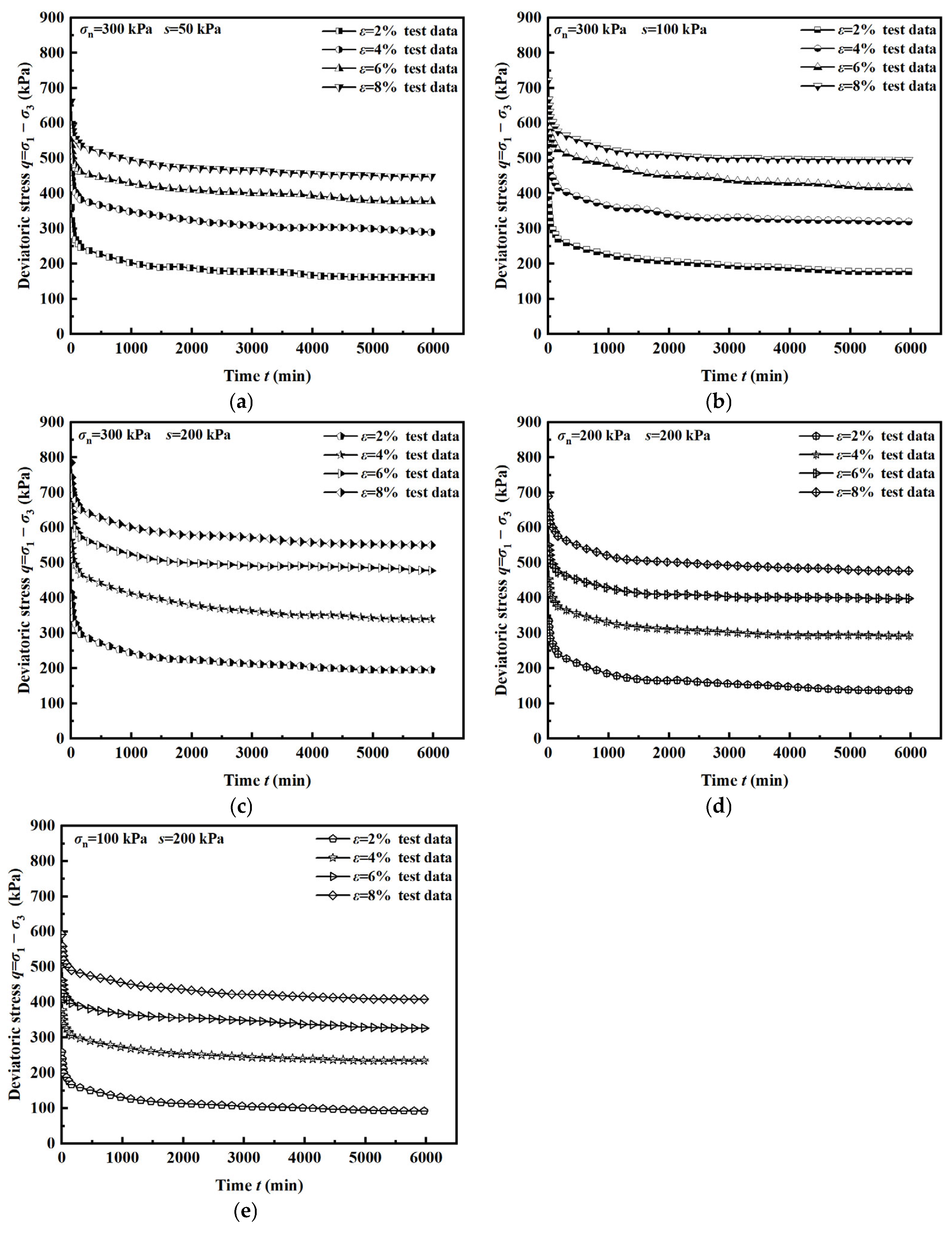

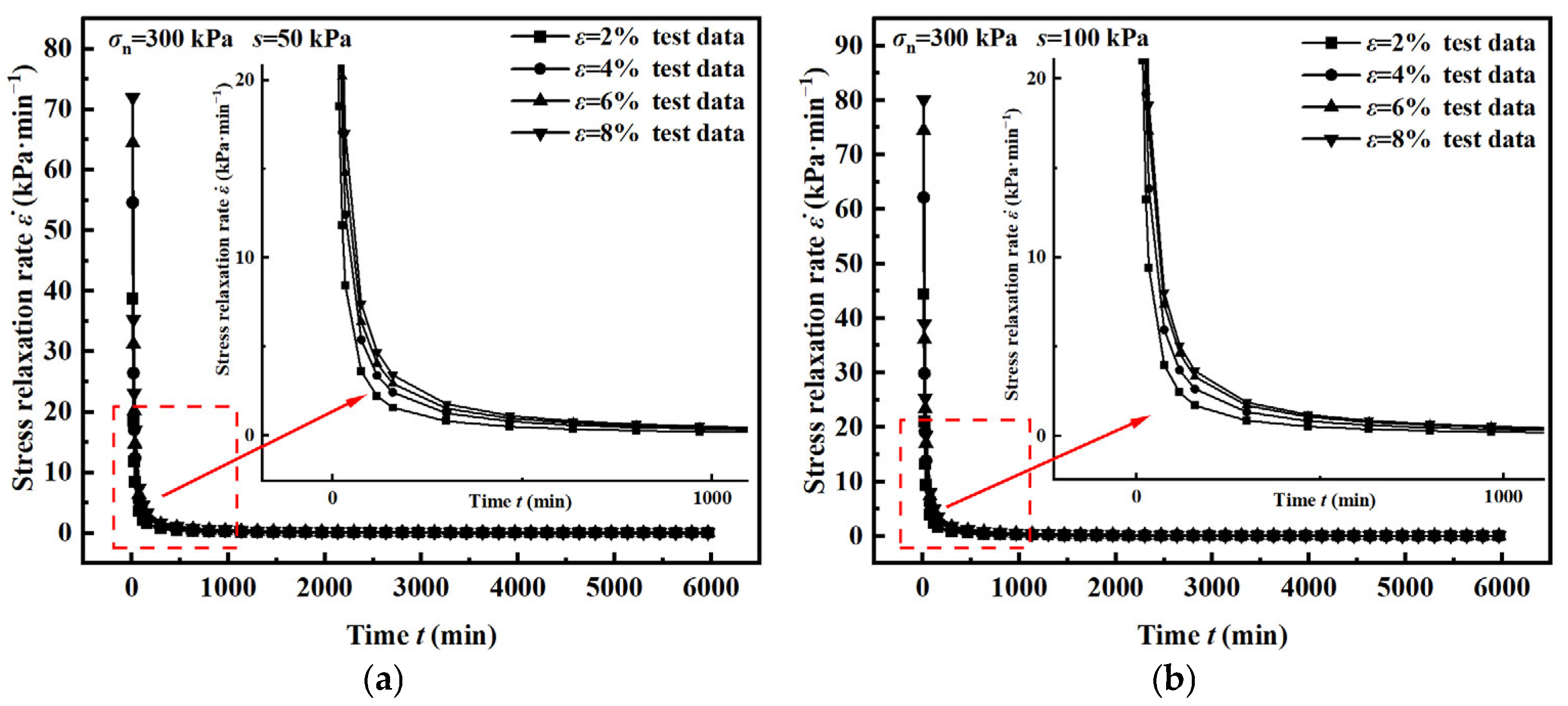

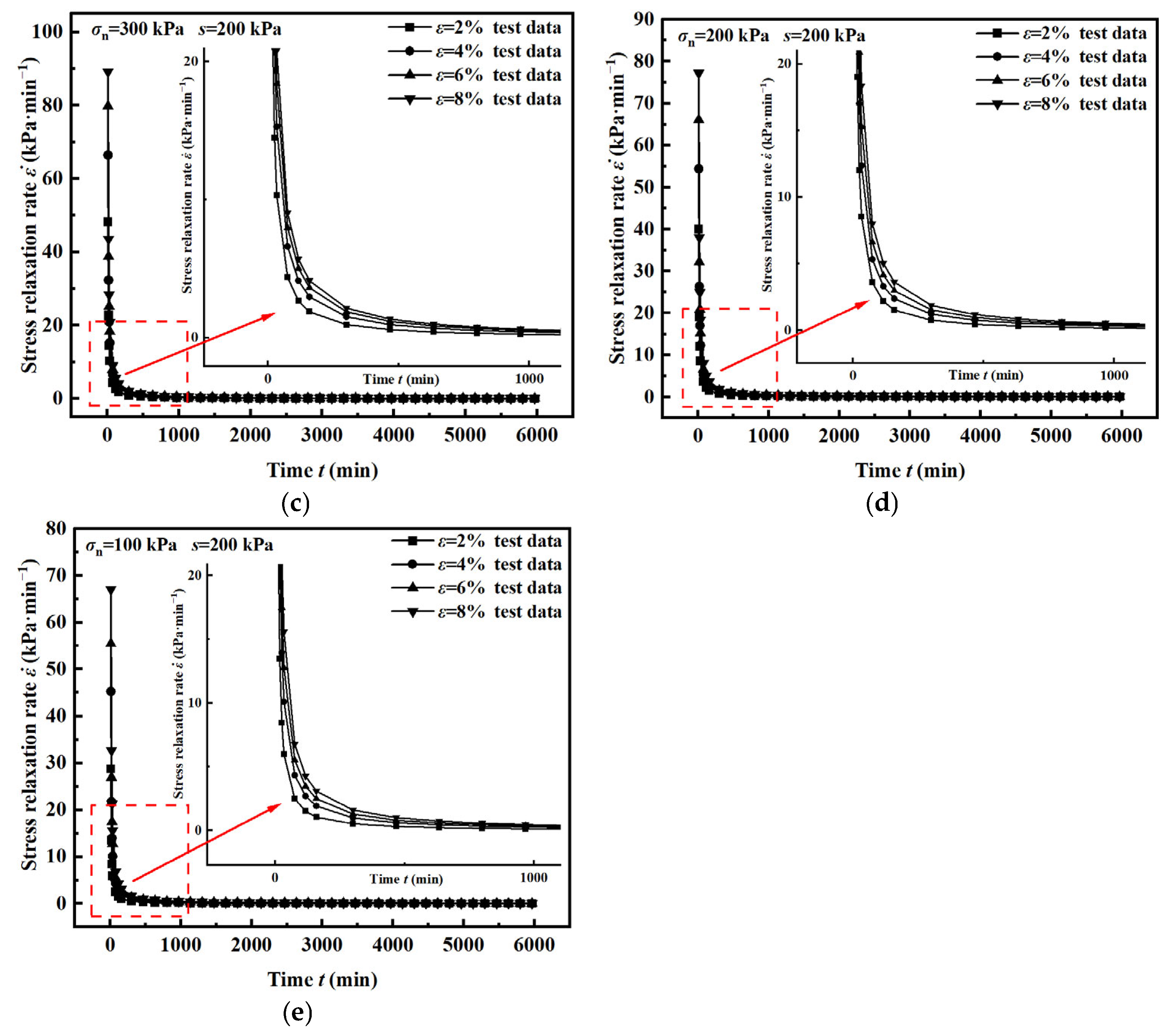

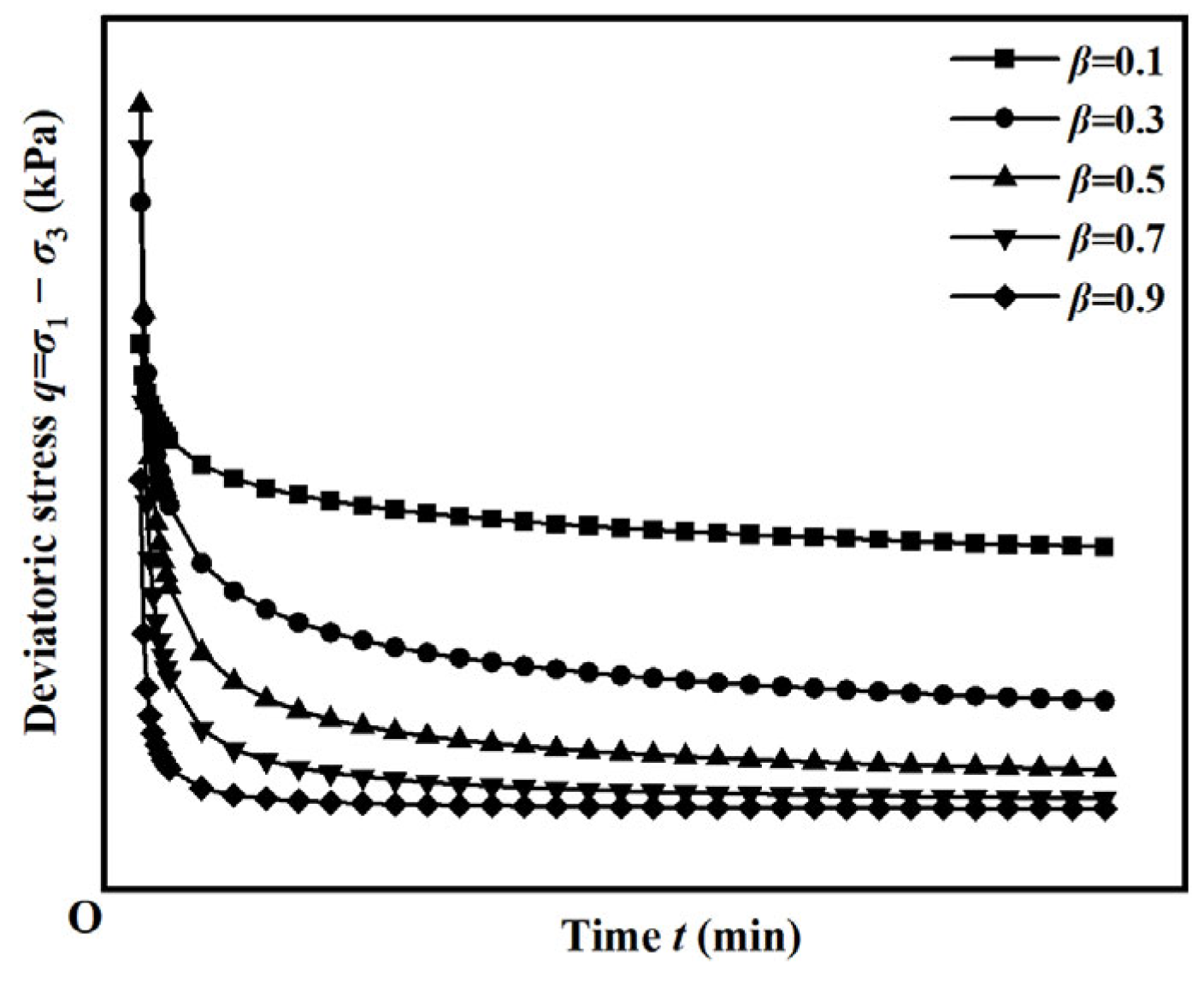

4.1. Stress Relaxation Curve and Rate Curve Characteristics

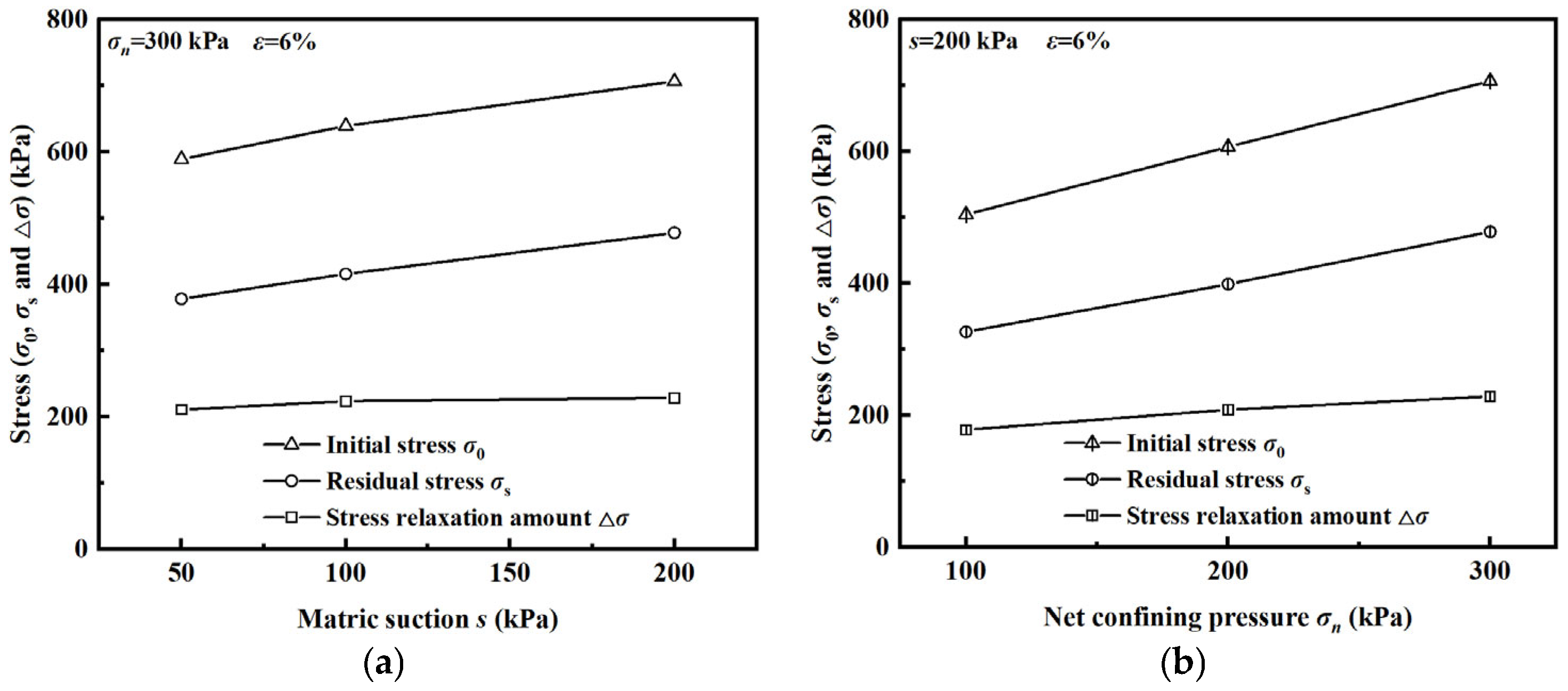

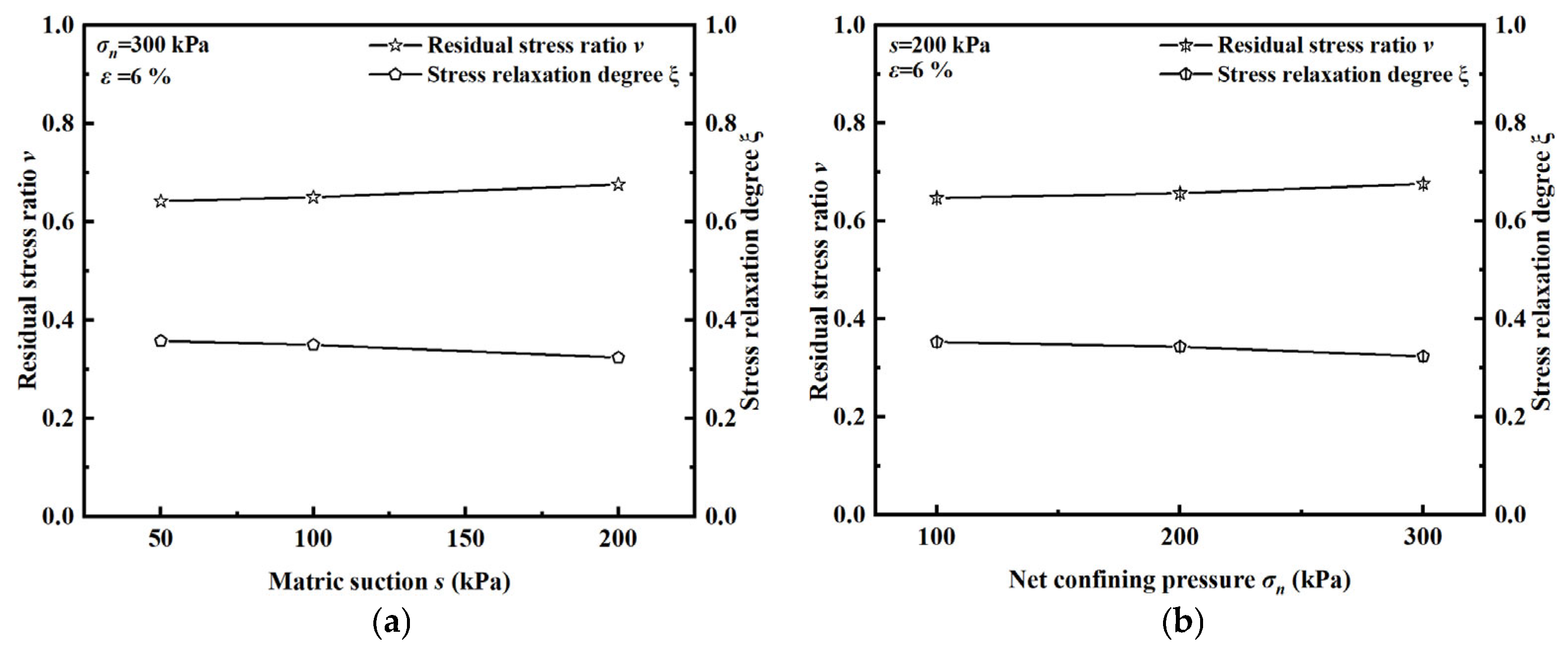

4.2. Influence of Matric Suction and Net Confining Pressure

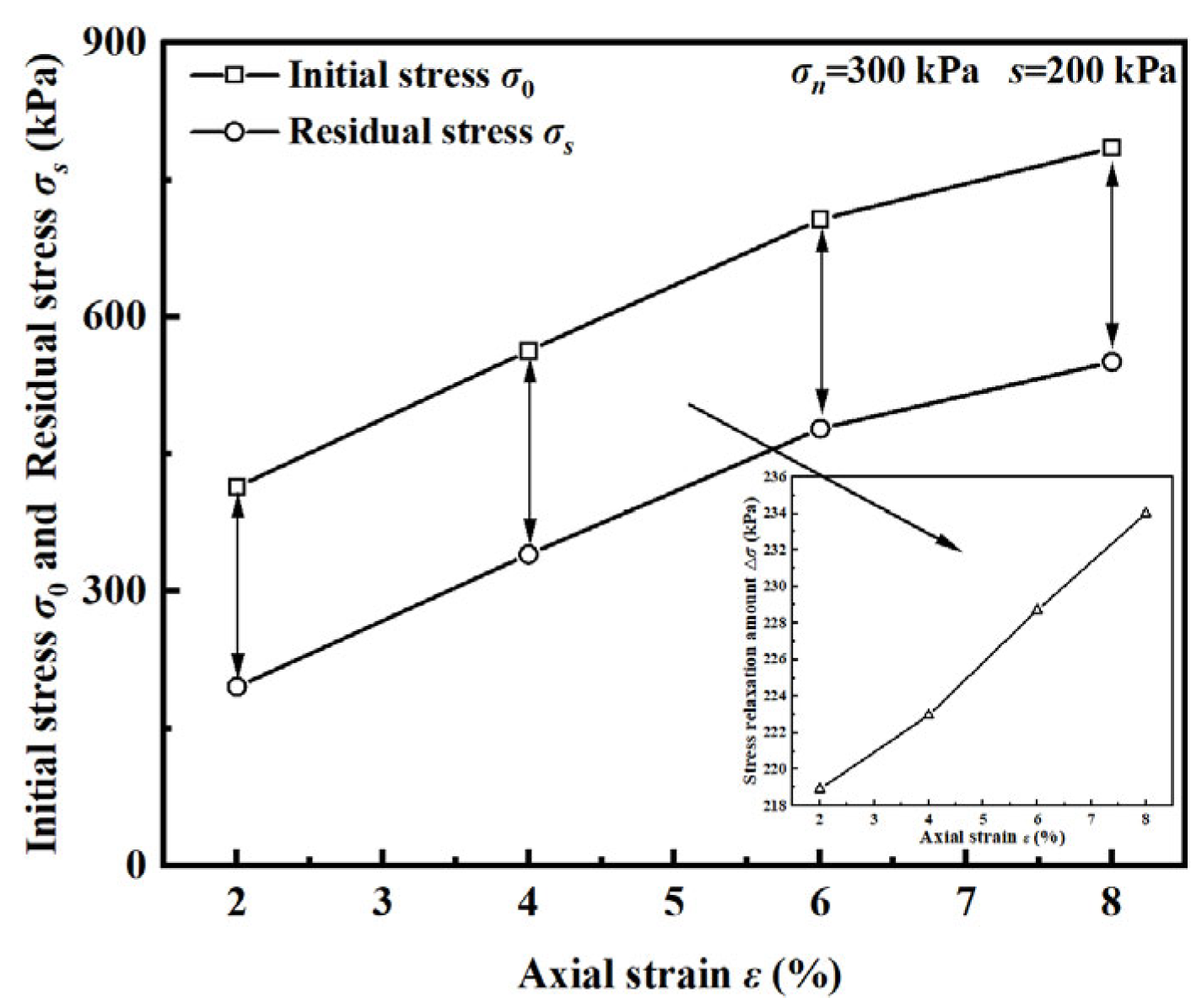

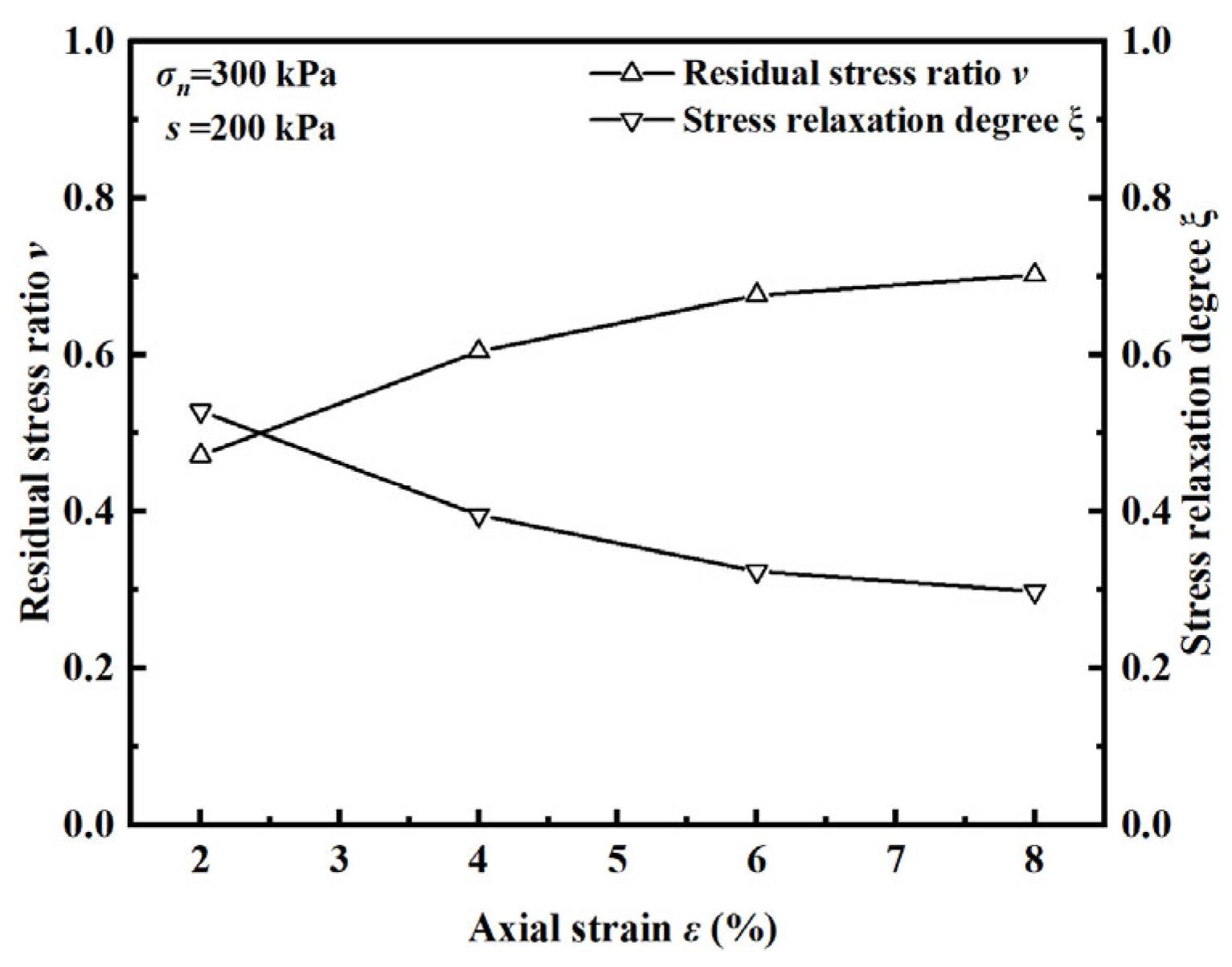

4.3. Influence of Strain Level on Stress Relaxation

5. Stress Relaxation Model Establishment

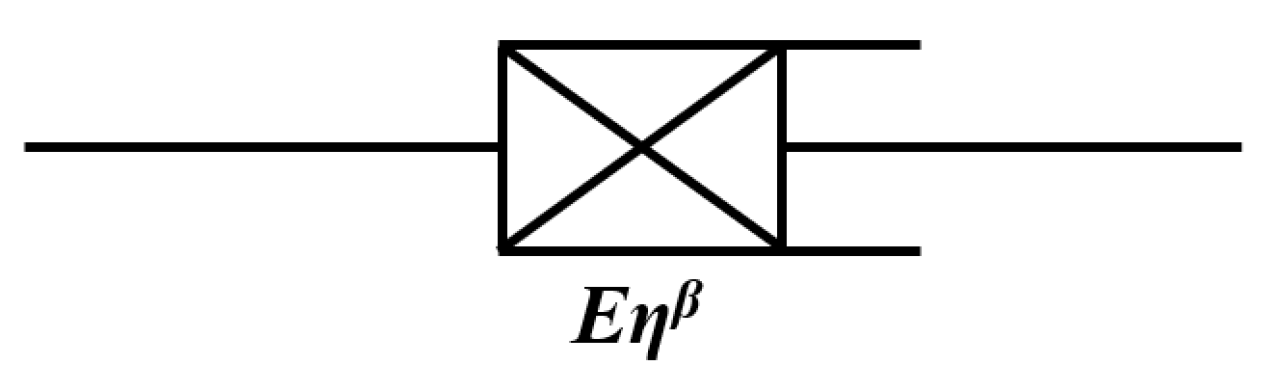

5.1. Koeller Dashpot

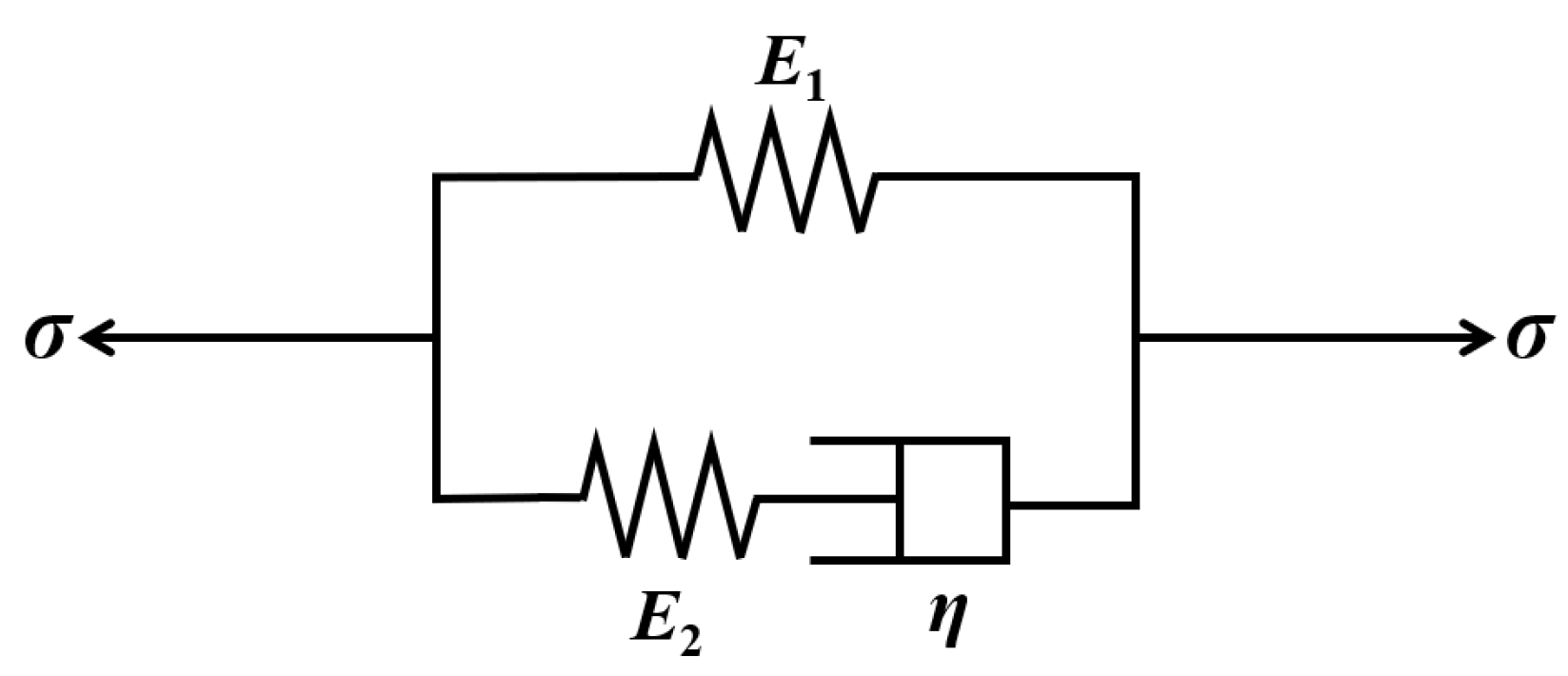

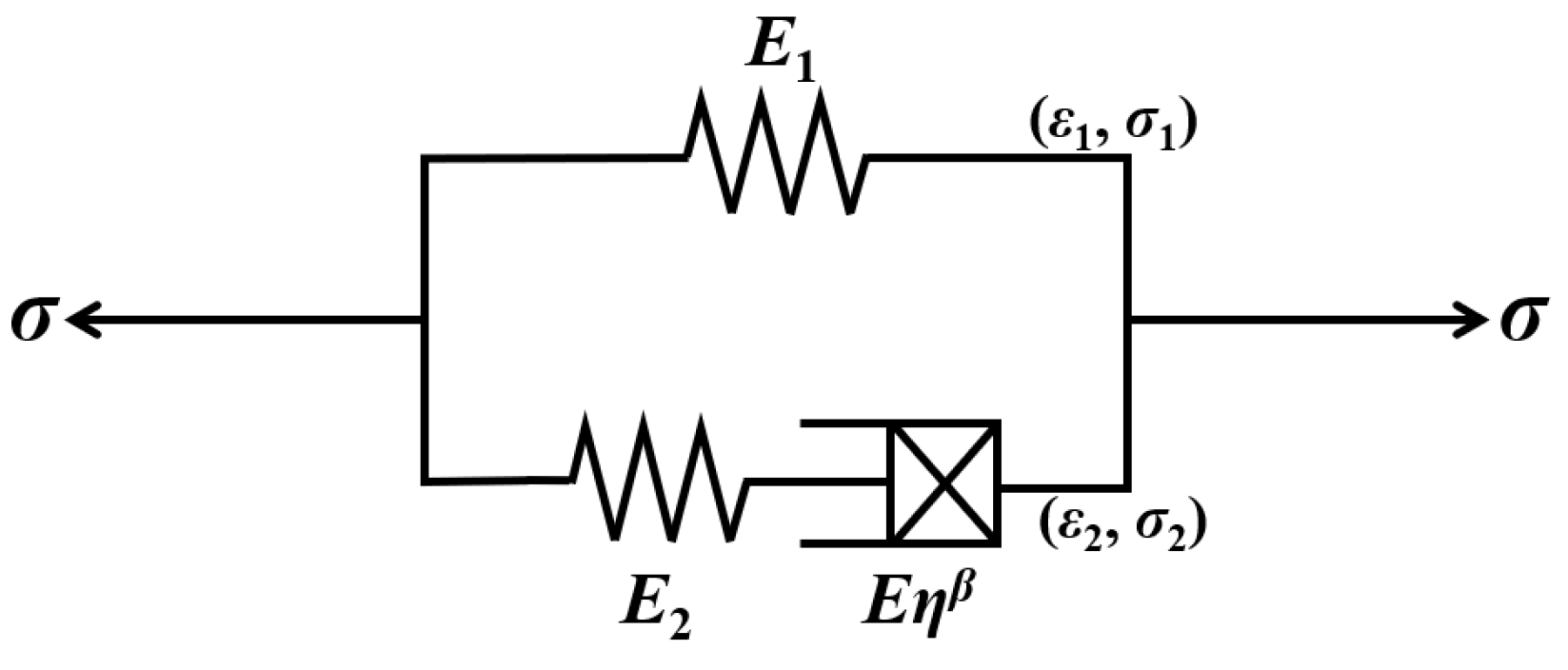

5.2. Fractional Stress Relaxation Model

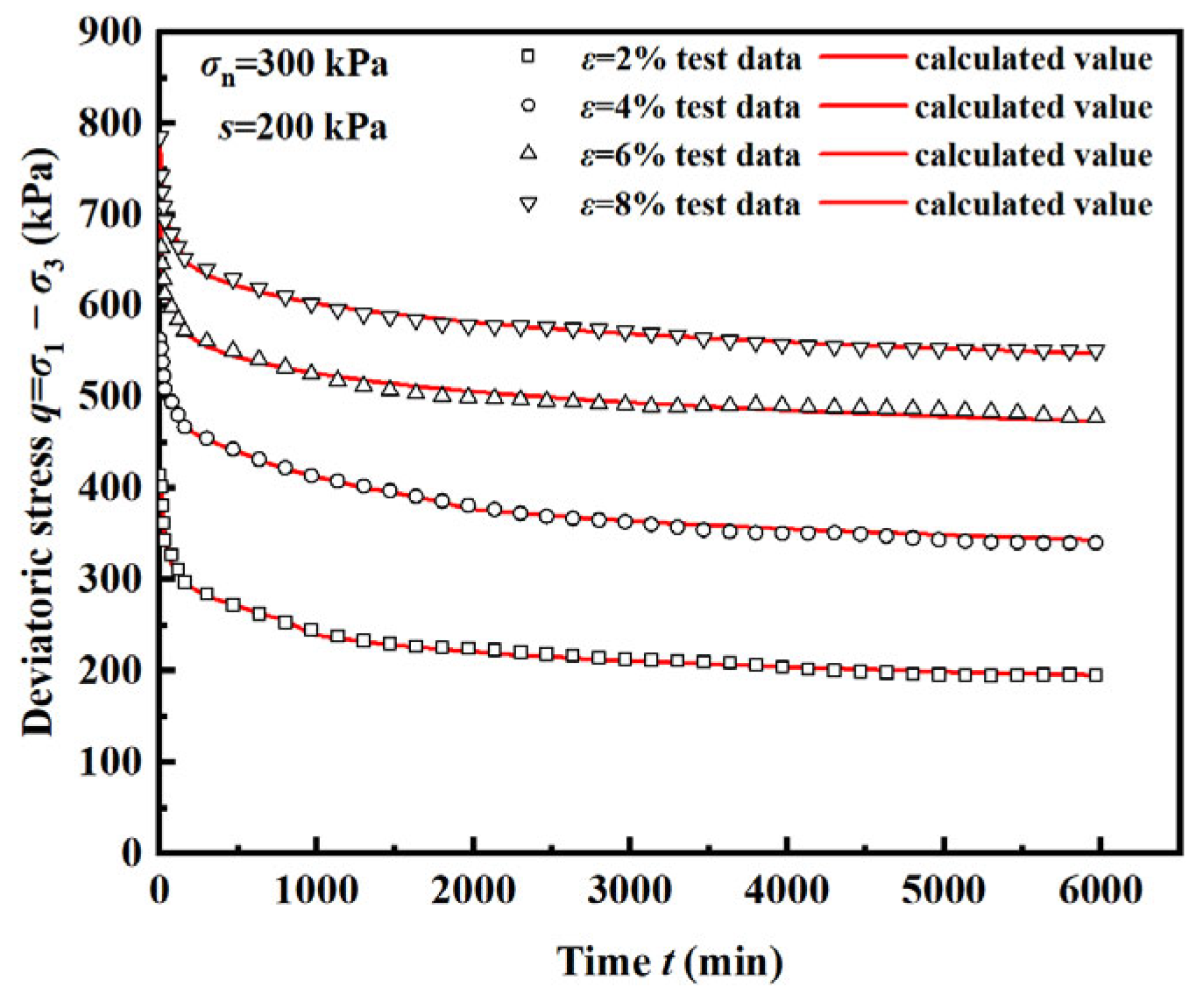

5.3. Parameter Identification and Model Verification

- (1)

- Global scatter search (GSS)—a population-based “global generic” optimizer—generated 600 starting points within the physically admissible box E1, E2 ∈ [10, 1000] kPa; Eη ∈ [500, 30,000] kPa·min; β ∈ [0.05, 0.3]; k ∈ [0.05, 0.3]. Population size = 80, mesh size = 15, stall iterations = 100.

- (2)

- The best 5% of GSS individuals were refined with Levenberg–Marquardt (initial μ = 0.01, scale factor = 10, max iterations = 300, function tolerance = 10−8).

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- In the decay relaxation phase, the deviatoric stress decreases as the accumulated deformation energy is consumed over time. During the stabilizing relaxation phase, the deviatoric stress tends to stabilize at a steady value because the particles with broken connections within the soil body are reconnected by constant adjustment and reach equilibrium. The change in deviatoric stress during relaxation is positively correlated with the strain level. The stress relaxation process in unsaturated reticulated red clay is a process in which cracks within the soil body increase and consume deformation energy with time.

- (2)

- The sharpest relaxation occurs immediately after load application, during which 80–90% of the initial stress dissipates within a brief interval. Once relaxation initiates, the specimen cannot fully discharge the energy introduced by deviatoric loading through further deformation. As a result, many cracks appear inside the specimen, breaking the connection between soil particles, reducing the strength of the specimen, and releasing the energy generated by the deviatoric stress compression. As energy is progressively dissipated, the rate of stress relaxation diminishes and eventually approaches zero. Both matric suction and net confining pressure exert a pronounced influence on the relaxation index.

- (3)

- The FPTh model based on the Caputo fractional derivative can accurately predict the instantaneous elasticity, attenuation relaxation, and long-term residual three-stage response of networked red soil under the suction–stress coupling path. Its fractional memory core is naturally embedded in the deformation history, allowing strength attenuation prediction without the need for additional cyclic parameters. The model can be written into user subroutines and embedded into finite elements to output the residual stress ratio of the unit in real time during any rainfall infiltration suction redistribution steps, driving the dynamic update of the sliding surface strength field. This provides a dynamic threshold that can be adjusted over time for the slope safety factor and provides a direct and quantitative theoretical basis for the standardized time-varying strength reduction factor.

- (4)

- The FPTh model reliably predicts stress relaxation under monotonic loading and constant suction; its constant-order Caputo kernel, however, cannot remember cyclic mechanical or hydraulic paths. Future studies, variable-order fractional operators, hydro-mechanical coupling, and hybrid integer–fractional frameworks will be explored to quantify path-dependent hysteresis.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khan, M.S.; Nobahar, M.; Stroud, M.; Amini, F.; Ivoke, J. Evaluation of Rainfall Induced Moisture Variation Depth in Highway Embankment Made of Yazoo Clay. Transp. Geotech. 2021, 30, 100602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Huang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Liu, G.; Hu, C.; Liu, J. Experimental and Microscopic Analysis for Impact of Compaction Coefficient on Plastic Strain Characteristic of Soft Clay in Seasonally Frozen Soil Regions. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Li, R.; Chen, F.; Cao, K.; Guo, L.; Qiu, Q. Mechanical Properties and Microscopic Fractal Characteristics of Lime-Treated Sandy Soil. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jia, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D. Research Status and the Prospect of Fractal Characteristics of Soil Microstructures. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirizadeh, S.; Sarikhani, R.; Jamshidi, A.; Dehnavi, A.G. Physico-Mechanical Properties of the Sandstones and Effect of Salt Crystallization on Them: A Comparative Study between Stable and Unstable Slopes. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, F.; Zhang, F.; Hussain, M.A.; Abbas, H.; Alrefaei, A.F.; Albeshr, M.F.; Iqbal, J.; Ghani, J. Landslide Susceptibility Assessment along the Karakoram Highway, Gilgit Baltistan, Pakistan. Sci. Remote Sens. 2021, 9, 100132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Hou, D.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, X. Experimental Study on Instability Mechanism and Critical Intensity of Rainfall of High-Steep Rock Slopes under Unsaturated Conditions. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2023, 33, 1243–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Yu, Q.; Ma, Q.; Guo, L. Study on the Heat and Deformation Characteristics of an Expressway Embankment with Shady and Sunny Slopes in Warm and Ice-Rich Permafrost Regions. Transp. Geotech. 2020, 24, 100390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Dong, J.; Leng, W.; Yang, Q. Characterization of Resilient Behavior of a Fine-Grained Subgrade Filler under Graded Variable Confining Pressure. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e04960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showkat, R.; Babu, G.S. Deterministic and Probabilistic Analysis of the Response of Shallow Footings on Unsaturated Soils Due to Rainfall. Transp. Geotech. 2023, 43, 101150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, D.; Ishikawa, T.; Si, J.; Tokoro, T. Effect of Complex Climatic and Wheel Load Conditions on Resilient Modulus of Unsaturated Subgrade Soil. Transp. Geotech. 2024, 45, 101186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Zhang, T.; Cui, H.; Yin, X.; Zhang, W. Numerical Investigation of Post-Earthquake Rainfall-Induced Slope Instability Considering Strain-Softening Effect of Soils. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 171, 107938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Hazarika, H.; Liu, G.; Kochi, Y.; Furuichi, H.; Matsumoto, D. Seismic Behavior of Highway Embankment Reinforced with Remedial Countermeasures on Saturated Loose Sandy Layer. Transp. Geotech. 2024, 45, 101183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Qi, J.; Yao, X. Stress Relaxation Characteristics of Warm Frozen Clay under Triaxial Conditions. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2011, 69, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, M.T. Secondary Creep Approximations of Ice-Rich Soils and Ice Using Transient Relaxation Tests. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2013, 88, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lade, P.V.; Karimpour, H. Stress Relaxation Behavior in Virginia Beach Sand. Can. Geotech. J. 2015, 52, 813–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xu, X.; Li, J.; Shen, F.; Li, Y. An Experiment Study on Stress Relaxation of Unsaturated Lime-Treated Expansive Clay. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Hong, J.; Song, E. DEM Study on the Macro- and Micro-Responses of Granular Materials Subjected to Creep and Stress Relaxation. Comput. Geotech. 2018, 102, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.; Prasad, M.; Abbud-Madrid, A.; Dreyer, C.B. Penetration and Relaxation Behavior of Dry Lunar Regolith Simulants. Icarus 2019, 328, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xia, Z. DEM Study of Creep and Stress Relaxation Behaviors of Dense Sand. Comput. Geotech. 2021, 134, 104142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Chu, X. Influence of Particle Shape on Creep and Stress Relaxation Behaviors of Granular Materials Based on DEM. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 166, 105941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jariyatatsakorn, K.; Kongkitkul, W.; Tatsuoka, F. Prediction of Creep Strain from Stress Relaxation of Sand in Shear. Soils Found. 2024, 64, 101472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; Lu, J.; Yao, A.; Li, H.; Gong, Y.F. Nonlinear Elastic Deformation Model of Belled Uplift Piles under the Coupling Effects of Groundwater and Shear Strain Relaxation. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 171, 106411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jiang, X.; Sun, R.; Gu, H.; Fu, Y.; Qiu, Y. Stability Analysis of Unsaturated Soil Slopes with Cracks under Rainfall Infiltration Conditions. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 165, 105907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, A.; Kumar, A.; Toll, D.G. The Bounding Effect of the Water Retention Curve on the Cyclic Response of an Unsaturated Soil. Acta Geotech. 2023, 18, 1901–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delcourt, R.T.; de Campos, T.M.P.; dos Santos Antunes, F. Interrelationship among Weathering Degree, Pore Distribution and Water Retention in an Unsaturated Gneissic Residual Soil. Eng. Geol. 2022, 299, 106570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathipour, H.; Tajani, S.B.; Payan, M.; Chenari, R.J.; Senetakis, K. Influence of Transient Flow during Infiltration and Isotropic/Anisotropic Matric Suction on the Passive/Active Lateral Earth Pressures of Partially Saturated Soils. Eng. Geol. 2022, 310, 106883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, M.; Rezania, M.; Mousavi Nezhad, M. Rate Dependency and Stress Relaxation of Unsaturated Clays. Int. J. Geomech. 2019, 19, 04019128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Liang, J.; Du, X.; Ma, C.; Gao, Z. Fractional Elastoplastic Constitutive Model for Soils Based on a Novel 3D Fractional Plastic Flow Rule. Comput. Geotech. 2019, 105, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Song, H.; Zhou, H.; Xie, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, W. A Fractional Derivative Insight into Full-Stage Creep Behavior in Deep Coal. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, H.M.; Fernandez, A. Operational Calculus for Caputo Fractional Calculus with Respect to Functions and the Associated Fractional Differential Equations. Appl. Math. Comput. 2021, 409, 126400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, M. Numerical Investigation of Water Migration in a Closed Unsaturated Expansive Clay System. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2023, 82, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Sumelka, W.; Gao, Y. Fractional Plasticity for Over-Consolidated Soft Soil. Meccanica 2022, 57, 845–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, D.; Han, C.; Shao, Y. A Caputo Variable-Order Fractional Damage Creep Model for Sandstone Considering Effect of Relaxation Time. Acta Geotech. 2022, 17, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, R. A Caputo Fractional Derivative of a Function with Respect to Another Function. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2017, 44, 460–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Sun, Y. Stress-Fractional Modelling of the Compressive and Extensive Behaviour of Granular Soils. Comput. Geotech. 2020, 120, 103407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainardi, F. Fractional Calculus and Waves in Linear Viscoelasticity: An Introduction to Mathematical Models; World Scientific: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Yang, Y. Matric Suction Creep Characteristics of Reticulated Red Clay. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22, 3837–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, T. Experimental and Discrete Element Modeling Study on Suction Stress Characteristic Curve and Soil–Water Characteristic Curve of Unsaturated Reticulated Red Clay. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2022, 81, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Likos, W.J. Suction Stress Characteristic Curve for Unsaturated Soil. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2006, 132, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, J.Z.; He, Y. Impact of the Loading Rate on the Unsaturated Mechanical Behavior of Compacted Red Clay Used as an Engineered Barrier. Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 80, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Chen, C.; Du, C. Interface Stress Relaxation Behavior of Grouted Anchors in Red Clay: Experimental Study and a Disturbed State Concept-Based Theoretical Model. Acta Geotech. 2023, 18, 3287–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xu, X.; Liu, Q.; Ding, Y.; Shen, F. A Nonlinear Fractional-Order Damage Model of Stress Relaxation of Net-Like Red Soil. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, S.; Nie, Z.; Hu, Q. A Disturbed State Concept-Based Stress-Relaxation Model for Expansive Soil Exposed to Freeze–Thaw Cycling. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2020, 24, 2621–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattah, M.Y.; Al-Omari, R.R.; Hameedi, M.K. Tracing of Stresses and Pore Water Pressure Changes during a Multistage Modified Relaxation Test Model on Organic Soil. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lv, J.; Huang, J.; Tang, Y. A Fast Euler–Maruyama Method for Riemann–Liouville Stochastic Fractional Nonlinear Differential Equations. Physica D 2023, 446, 133685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.W.; Chen, W.B.; Yue, Z.Q. Consolidation of Multilayered Soil with Fractional Derivative Viscoelasticity due to Surface Loading and Internal Pumping. Transp. Geotech. 2023, 42, 101083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, M. Linear Models of Dissipation whose Q is almost Frequency Independent—Part II. Geophys. J. Int. 1967, 13, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeller, R.C. Applications of Fractional Calculus to the Theory of Viscoelasticity. J. Appl. Mech. 1984, 51, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.J. A Nonlinear Damage Model for Structural Clay. J. Hydrosci. Eng. 1993, 3, 247–255. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, X.; Tian, S.; Tang, L.; Li, S. A Damage-Softening and Dilatancy Prediction Model of Coarse-Grained Materials Considering Freeze–Thaw Effects. Transp. Geotech. 2020, 22, 100307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Wang, X.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, F. Triaxial Creep Test and Damage Model Study of Layered Red Sandstone under Freeze–Thaw Cycles. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Properties | Value |

|---|---|

| Water content (%) | 24.3 |

| Density (g/cm3) | 1.9 |

| Specific gravity | 2.71 |

| Liquid limit (%) | 40.8 |

| Plastic limit (%) | 22 |

| Air-entry value (kPa) | 55 |

| Cohesion (kPa) | 59 |

| Friction angle (°) | 20.3 |

| Effective size (mm) | 0.047 |

| Control size (mm) | 0.694 |

| NO. | Net Confining Pressure σn (kPa) | Matric Suction s (kPa) | Confining Pressure σ3 (kPa) | Strain Level (ε%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | 300 | 50 | 350 | 2, 4, 6, 8 |

| R2 | 300 | 100 | 400 | |

| R3 | 300 | 200 | 500 | |

| R4 | 200 | 200 | 400 | |

| R5 | 100 | 200 | 300 |

| σn (kPa) | s (kPa) | ε (%) | E1 (kPa) | E2 (kPa) | Eη (kPa·min) | β | k | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 | 200 | 2 | 221.09 | 736.26 | 14,786.97 | 0.1207 | 0.1285 | 0.9975 |

| 4 | 157.16 | 416.16 | 10,966.62 | 0.1203 | 0.1437 | 0.9969 | ||

| 6 | 120.55 | 168.82 | 4283.98 | 0.1169 | 0.1636 | 0.9955 | ||

| 8 | 99.91 | 72.08 | 1343.46 | 0.1234 | 0.1819 | 0.9973 |

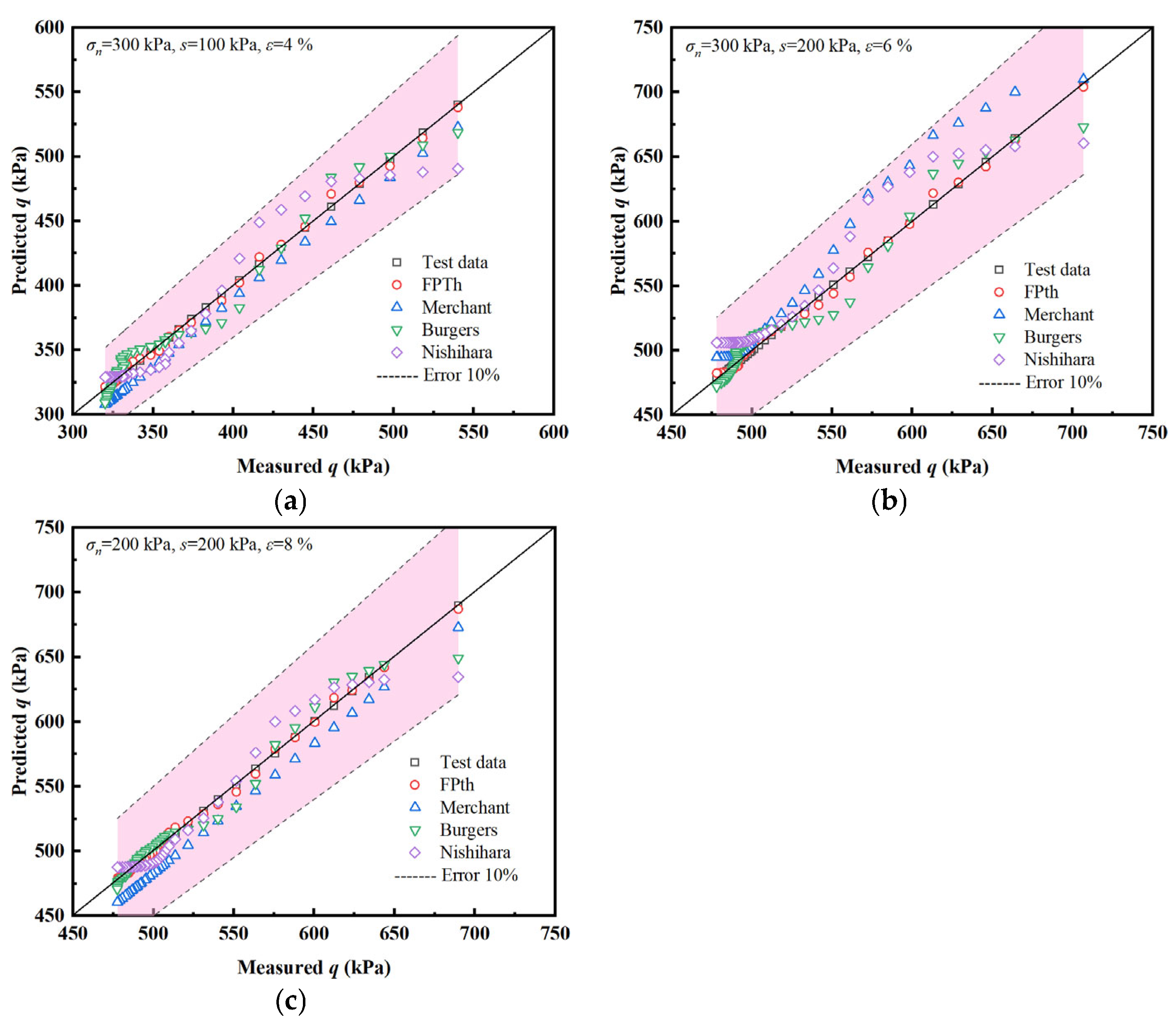

| Net Confining Pressure and Matric Suction | Stress Relaxation Models | R2 | RMSE | SSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| σn = 300 kPa, s = 100 kPa, ε = 4% | Merchant | 0.9305 | 17.2 | 12,721.12 |

| Burgers | 0.9713 | 9.90 | 4214.43 | |

| Nishihara | 0.9402 | 14.29 | 8780.78 | |

| FPTh | 0.9964 | 3.16 | 429.38 | |

| σn = 300 kPa, s = 200 kPa, ε = 6% | Merchant | 0.9325 | 16.80 | 12,136.32 |

| Burgers | 0.9701 | 9.62 | 3979.41 | |

| Nishihara | 0.9498 | 12.47 | 6686.54 | |

| FPTh | 0.9955 | 3.24 | 451.40 | |

| σn = 200 kPa, s = 200 kPa, ε = 8% | Merchant | 0.9332 | 16.96 | 12,368.59 |

| Burgers | 0.9715 | 9.02 | 3498.50 | |

| Nishihara | 0.9486 | 12.11 | 6306.04 | |

| FPTh | 0.9977 | 2.29 | 225.50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, C.; Li, J. Fractional-Order Stress Relaxation Model for Unsaturated Reticulated Red Clay Slope Instability. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120786

Zhang C, Li J. Fractional-Order Stress Relaxation Model for Unsaturated Reticulated Red Clay Slope Instability. Fractal and Fractional. 2025; 9(12):786. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120786

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Chuang, and Jianzhong Li. 2025. "Fractional-Order Stress Relaxation Model for Unsaturated Reticulated Red Clay Slope Instability" Fractal and Fractional 9, no. 12: 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120786

APA StyleZhang, C., & Li, J. (2025). Fractional-Order Stress Relaxation Model for Unsaturated Reticulated Red Clay Slope Instability. Fractal and Fractional, 9(12), 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120786