1. Introduction

The mathematical notion of convexity occupies a pivotal role in engineering and mathematics, as it supports a wide range of theoretical and applied phenomena. The core of convex analysis are convex sets and convex functions that are essential tools in simplifying very complicated systems and optimizing complex mathematical models. By virtue of their well-behaved nature, especially the fact that there is a global minimum problems in convex functions become much easier to handle, and hence are central in optimization. Besides its interest for its own sake as pure mathematics, convexity has deep implications in most fields like control theory, economics, and systems engineering. In control theory, for instance, convexity guarantees that the designs for systems are stable and robust over a wide range of operating conditions. In economics, convexity also plays a role in the description of consumer preferences and analysis of market behavior, hence enabling efficient decision-making and resource allocation. It is interesting to note that convexity has practical applications in addition to being a theoretical or academic idea. Convex structures are frequently encountered by engineers and practitioners who are attempting to maximise system performance in order to increase operational efficiency and dependability. Convex functions are essential to integral inequalities, which may be the most aesthetically beautiful use of convexity. In mathematical analysis, integral inequalities are essential, particularly when it comes to bounding or approximating integral values. The

inequality, which gives estimates of the average value of a convex function over a specified interval, is one of the most significant of these [

1,

2,

3]. The topic is a rich and potent area of current mathematics research because of the relationship between convexity and integral-type inequalities.

Fractional calculus that generalizes classical calculus to non-integer order derivatives and integrals has emerged as a hot topic in recent years due to its ability to model systems with memory and with hereditary characteristics. It emerges as a valuable tool in physics, engineering, and even perhaps surprisingly in computer science [

4]. Its increasing relevance is not only restricted to practical sciences; fractional calculus has also been instrumental in the building of inequality theory. Fractional integral inequality is now a favorite and rapidly developing field of research in recent years. Sarikaya et al. [

5] added an important contribution by using the

fractional integrals framework to establish the generalized

inequality. Their research enhanced the mathematical techniques employed in dynamic systems analysis and the theory of inequality analysis by creating tighter bounds in analytical terms and greater understanding of the behavior of convex functions. Recent studies also broadened this field with new methods for fractional integral operators and inequalities. Nápoles-Valdés and Bayraktar in 2025 [

6], explored Caputo-weighted integrals and their uses, citing the potential to generalize traditional results and refine analytical procedures in fractional frameworks. Similarly, Guzmán and Nápoles-Valdés in 2025 [

7], explored

-type fractional integral inequalities, formulating new bounds and extensions that close the gap between classic analysis and modern fractional theory. These advances in their entirety enrich the knowledge of the structural features and uses of fractional integral inequalities in mathematics analysis and applied sciences.

After the landmark discovery of the

inequalities for the

fractional integrals, important advances have been made in extending

-type inequalities to several fractional integral definitions. Researchers have explored these inequalities in the context of numerous fractional operators, including the generalized proportional fractional integrals [

8], Sarikaya fractional integrals [

9], Katugampola fractional integrals [

10],

k-fractional integrals [

11],

-

-fractional integrals [

12],

-fractional integrals [

13], generalized

-fractional integrals [

14] and conformable fractional integrals [

15]. Alongside these developments, a wide array of inequalities of fractional order has also been established, reflecting the growing depth and diversity of the field. These include fractal Hadamard-Mercer-type inequalities [

16], Simpson-type inequalities [

17], Euler-Maclaurin-type inequalities [

18], Bullen-type inequalities [

19], and Ostrowski-type inequalities [

20], among others. For readers seeking a comprehensive overview of recent advancements in fractional integral inequalities, several up-to-date contributions are recommended, such as those found in [

21,

22,

23] and the references therein.

A collection of random variables parameterized by time or space describing the change of a system under uncertainty is referred to as a stochastic process in statistics and probability theory. They characterize the apparently random change of a system, often over different time or space separations. The term “stochastic” qualifies processes that occur at unpredictable or irregular rates. Stochastic processes can be used to simulate random change over time in systems. For instance, there are many random parameters that may result in fluctuations of bacterial growth, but long-term forecasting is not impossible. Just as thermal noise within electrical systems produces random changes in voltage or current, such apparently random behavior can be represented by simple stochastic processes, and these can offer insight into the behavior of the system.

Physicists and mathematicians have traditionally used stochastic processes as mathematical models to describe a wide range of phenomena, including changes in population in ecosystems, randomly diffusing gas molecules, and stock price fluctuation. Stochastic models, which have many uses in research and engineering, can often be used to model these processes and other elements like molecular interactions whenever there is unpredictability. They mimic population dynamics or the emergence of diseases in biology, and they depict systems based on the mobility of various molecules in physics. The importance of stochastic processes lies in their ability to systematically explain systems that behave randomly. They are vital in domains where randomness or particular results at every stage are critical, such as computer science, data transfer, cryptography, and signal processing. They are therefore essential for conducting research and resolving practical issues. Scientists and engineers are able to forecast future trends, optimize systems, and design solutions that consider environmental uncertainties by numerically simulating these processes. System state prediction, data compression algorithms, and secure communication through cryptography are other significant applications. Recent developments in fractional stochastic processes provide a strong foundation for our study. Jiang and Miao [

24] examined anomalous stochastic processes via generalized fractional calculus, offering models for non-classical diffusion behavior. Sahebi Fard et al. [

25] introduced a financial market model using the

-Caputo fractional derivative, effectively capturing memory and hereditary effects in market dynamics. Guidoum et al. [

26] analyzed fractional and higher-order moments of stochastic differential equations, highlighting the behavior of moments under fractional dynamics. These works collectively illustrate the breadth and applicability of fractional stochastic modeling.

Convex stochastic processes, which generalize the concept of classical convex functions to stochastic processes systems including randomness were initially introduced by Nikodem [

27] in 1980. Further, he found that such stochastic processes exhibit a number of properties similar to classical convex functions. The Jensen convex mapping, central to the theory of inequalities, is one such useful tool in this respect. A number of crucial inequalities can be obtained from this mapping, and their applicability to stochastic processes was demonstrated by Skowronski [

28] in 1992. Expanding on these concepts, Kotrys [

29] showed that, in particular, for convex stochastic processes, the upper and lower bounds of the

inequality may be found using integral operators. Kotrys’s work showed how the

inequality, an important result in convex analysis, could be adapted for stochastic processes. There have been a great many papers in the literature over the last few years on all sorts of convexity for stochastic processes. Okur et al. [

30] used the idea of p-convexity, which is a particular kind of convexity, to construct the

inequality for stochastic processes. Erhan [

31] made a further contribution by building these inequalities with the use of another version of convexity called s-convexity. Budak et al. [

32] generalised the work of other academics by presenting these inequalities using the concept of h-convexity. As mentioned in the sources [

33,

34,

35], there have been many research investigating different kinds of convexity for individuals who are interested in the most recent developments in stochastic processes. Further broadening the applicability of these mathematical ideas, Tunç in [

36] made a substantial contribution by developing the Ostrowski-type inequality particularly for h-convex functions. Zhao et al. [

37] have connected inequality to interval mathematics, putting these inequality within the context of interval analysis. Using interval analysis as a foundation, Afzal et al. [

38] presented the notion of stochastic processes before the end of 2022. They also created new versions of the Jensen and

inequalities that are particularly designed for stochastic processes, fusing these two mathematical ideas in an innovative way. A novel mathematical framework called the

-G-convex stochastic process was presented by Eliecer et al. [

39]. It incorporates functions

and

together with a parameter

to extend classical convexity to stochastic processes. By this approach, they were able to establish some inequalities associated with stochastic analysis. By utilizing fractional operators in order to use fractional calculus on the

-convex stochastic process, Cortez [

40] generalized this work and obtained more inequalities. These developments strengthen mathematical models in many disciplines through the power of estimating systems subject to fractional dynamics and uncertainty. Hafiz [

41] discussed the applications of fractional calculus to stochastic processes, paving the way for modeling stochastic processes reliant on memory. Kotrys [

42] extended classical inequalities such as Jensen,

, and Fejér inequalities to strongly convex stochastic processes, providing vital information regarding probabilistic convexity theory. Further advances were made by Agahi and Babakhani [

43], who introduced fractional-order forms of Jensen and

inequalities for convex stochastic processes to make them more effective in stochastic modeling fields. Fu et al. [

44] subsequently investigated n-polynomial convex stochastic processes and presented

-type inequalities for such functions, which determined the domain of stochastic optimization and uncertainty modeling. The work in general stresses the importance of convexity in stochastic situations and its use in mathematical inequalities, probability theory, and optimization in practice.

Superquadraticity gives tighter and more reliable bounds than ordinary convexity, considerably enhancing integral inequality theory. This is extremely welcomed in applications of applied mathematics, where a better approximation means increased model accuracy, and for optimisation tasks, where boundary estimate quality decides the optimum solution. Thus, superquadraticity broadens the theory basis of inequality structures and enhances their applicability. It effectively presents a robust analytical foundation for the development and use of integral inequalities in a wide range of mathematical and applied problems.

The concept of superquadraticity extending the traditional convexity was first introduced by Abramovich et al. [

45]. This initial work prepared the ground for a wider analytical framework that could provide tighter inequalities compared to those obtained from regular convex functions. Abramovich and co-authors [

46] later introduced a formal definition for superquadratic functions together with essential theoretical observations that further enhanced the understanding of this function class. Working from this basis, Li and Chen [

47] took the theory further by applying the fractional view of

-type inequalities through

fractional integrals, representing a huge step beyond superquadraticity to the world of fractional calculus. More was done by Alomari et al. [

48], who brought about the concept of h-superquadraticity, studied their structural properties and defined a new subclass within the larger family. In a valuable work in interval analysis and generalized function theory, Khan and Butt [

49] introduced cr-order interval-valued superquadratic functions and their fractional counterparts, emphasizing their applicability through multiple illustrations. Following this endeavor, Khan et al. [

50] introduced the

-superquadratic function, an even broader concept that includes examples, fundamental characteristics, integral inequalities, and real-world applications, thus enriching superquadraticity’s functional atmosphere. Continuing their exploration of information-theoretic applications, Butt and Khan [

51] developed information inequalities for superquadratic functions using the tools of interval calculus, connecting functional inequalities with measures of information. A foundational theoretical advance was made by Banić et al. [

52], who refined classical inequalities and solidified the theoretical underpinnings of superquadratic functions, paving the way for future researchs in the study of superquadratic stochastic processes.

In the aforementioned, we have discussed several well-known stochastic extensions of convexity, such as convex stochastic processes, p-convex, s-convex, h-convex, -G-convex, and n-polynomial convex stochastic processes, each providing generalizations within the convexity framework. However, the recently developed concept of (P, m)-superquadraticity serves as a refinement of convexity, offering significantly sharper bounds than those obtained from the classical and modern variants of convexity. Despite its strong potential, neither a stochastic formulation of (P, m)-superquadraticity nor its fractional counterpart has appeared in the literature. To fill this gap, the present work introduces the new class of (P, m)-superquadratic stochastic processes, establishes their key properties, develops Jensen-type and -type inequalities of integer order, and further generalizes them to fractional -type inequalities via stochastic fractional integrals. Moreover, we provide the first applications of this new class in information theory, demonstrating its analytical strength and broad applicability beyond the traditional convexity-based stochastic models.

The paragraph that follows provides an explanation of the paper’s structure:

Following the review of the required background knowledge and pertinent data regarding convexity, superquadraticity, convex stochastic processes and their inequalities in

Section 1 and

Section 2, we use 2D and 3D graphical representations to analyze the stochastic version of superquadraticity and their features. More importantly, in

Section 3, we develop new Jensen’s and

-type inequalities. Then, in

Section 4, Inequalities of

-type are obtained in fractional form. To evaluate the effectiveness of the results, examples and graphic descriptions of the findings are also taken into account. How the findings may be used to information theory is covered in

Section 5. In the final section,

Section 6, a clear and concise conclusion is drawn, accompanied by an overview of potential future developments inspired by the current work.

2. Preliminaries

The terms of significance for fractional integrals, convexity, and superquadraticity are defined in this section along with the associated inequalities.

Definition 1 ([

3])

. Let the function be a convex then is valid for every , , and The ’s inequality is a fundamental mathematical result that establishes both lower and upper bounds for mean values. In inequality theory, it is among the first types of inequality to use convex functions. For error calculations that use numerical integration, such as the trapezoidal and midpoint formulae, this inequality is an essential tool. This well-known finding is defined as follows.

Theorem 1 ([

3])

. ’s inequality states that if the function , is convex in , where . The following statement satisfies:

∀

. Definition 2. -fractional integrals with order with are defined asandThe notations and are the left and right sided operators. Where Γ

is a stated as gamma function and given by . Definition 3. A function is superquadratic, ifholds for every , , where and is a constant. Remark 1. If the inequality (

3)

is reversed then Ψ

is called subquadratic. As an example, we may use

. The function

is superquadratic for

and

, but subquadratic for

. Let

in this instance. At

, equality is also preserved in (

3).

More precisely, any randomly chosen superquadratic function meets the three supplementary conditions outlined in Lemma 1:

Lemma 1. Let be a superquadratic function, then

.

Provided that Ψ is differentiable at and satisfies , it follows that .

If Ψ is positive and on , then Ψ is convex.

Two major inequalities that contribute to the growth and development of superquadraticity are inequalities of Jensen’s and ’s types, which are the most significant and frequently applied results.

Theorem 2 ([

46])

. Let be a superquadratic thenholds for all and , where = , and . Banić et al. [

52] contributed to the field of superquadraticity by formulating the following

-type inequalities.

Theorem 3. Let be a superquadratic on J = then The line of support concept of superquadraticity is defined in Definition 3. In the following, we offer an additional definition.

Definition 4 ([

45])

. Let be a superquadratic function then holds for every and . Remark 2. Subquadraticity of the function Ψ

corresponds to the reversal of the inequality sign in (

6)

. Theorem 4 ([

47])

. Let be a superquadratic function on J = then where and are given in Definition 2. Definition 5 ([

50])

. A function is called (P, m)-superquadratic on for and ; if holds for any and . Ψ

is defined as a (P, m)-subquadratic function whenever its negation satisfies the (P, m)-superquadratic condition. Definition 6 ([

27])

. A mapping is considered a random variable if it is -measurable. It is defined on the probability space , where ∏

denotes the set of all possible outcomes, is a σ-algebra representing the collection of measurable events (subsets of ∏

), and is a probability measure that assigns probabilities to these events. Example 1. Imagine a coin toss in which , includes complete subsets of ∏, and assigns a probability of to each conceivable circumstance. So, and would be the definitions of a random variable Ψ.

Definition 7 ([

27])

. If for all , is a random variable, then a map is called a stochastic process. Example 2. Think about taking daily readings of the temperature at noon for a week. ∏ can represent all possible weather conditions in this instance, represents each day of the week, and gives the temperature on day , provided that ω is met. As a random variable, for each fixed day shows how the temperature varies under different meteorological conditions. Temperature variation over time, as influenced by changes in , is modeled by the stochastic process .

Definition 8 ([

27])

. A stochastic process , is called to be continuous on , if for every , we haveThe notation is used to represent convergence in probability within a probability space. Definition 9 ([

27])

. A stochastic process , is called to be mean-square continuous on , if for every , we have Where the random variable’s expectation is represented by . Remark 3. Probability continuity is obviously shown by mean-square continuity, while the contrary is not true.

Definition 10 ([

27])

. A stochastic process is called to be mean-square differentiable on at , if a random variable is given. This means that: Definition 11 ([

27])

. A stochastic process , is called to be mean-square integrable on , if for every , with , , , partitions , and then It indicates that the stochastic process’s mean-square integral is , and it may be expressed as Remark 4. The mean-square continuity of the stochastic process Ψ is sufficient to ensure the existence of the mean-square integral.

Remark 5. It asserts that if for all , then the following holds: Lemma 2 ([

29])

. Let a stochastic process be defined by , where are such that and . If , then the following holds:where and denote random variables. Definition 12 ([

29])

. We define a process to be convex stochastic on if, for every , the following condition is satisfied: for any .If is chosen in (

11)

, the process Ψ

is referred to as Jensen convex. Furthermore, if Ψ

exhibits convexity, then its negation is regarded as a concave stochastic process. For more interesting characteristics, the reader is referred to [28]. Lemma 3 ([

28])

. If and , then the following inequalities hold. where , and , are the right and left derivatives of Ψ

. Theorem 5 ([

28])

. It states that if a convex stochastic process is mean-square continuous and satisfies Jensen’s convexity on J, then the following inequalities holdsfor every Definition 13 ([

41])

. Let be a stochastic process satisfying the conditions stated in Definition 11. Then, the mean-square stochastic fractional integrals of order , denoted by and , are defined for Ψ

as follows.and 3. Analysis of Integral Inequalities Involving (P, m)-Superquadratic Stochastic Processes

In this section, we begin by introducing the definition of an (P, m)-superquadratic stochastic process, which generalizes the concept of an (P, m)-convex stochastic process. This generalization allows for the development of more refined results. Based on this definition, we investigate its properties and establish associated integral inequalities.

Definition 14. Let be a (P, m)-superquadratic stochastic process over , Where for thenholds for every and . If

is chosen in (

14), then the process

is termed as Jensen-(P, m)-superquadratic. If the process

is classified as (P, m)-superquadratic, then

is then termed as (P, m)-subquadratic stochastic process.

Example 3. A process Ψ

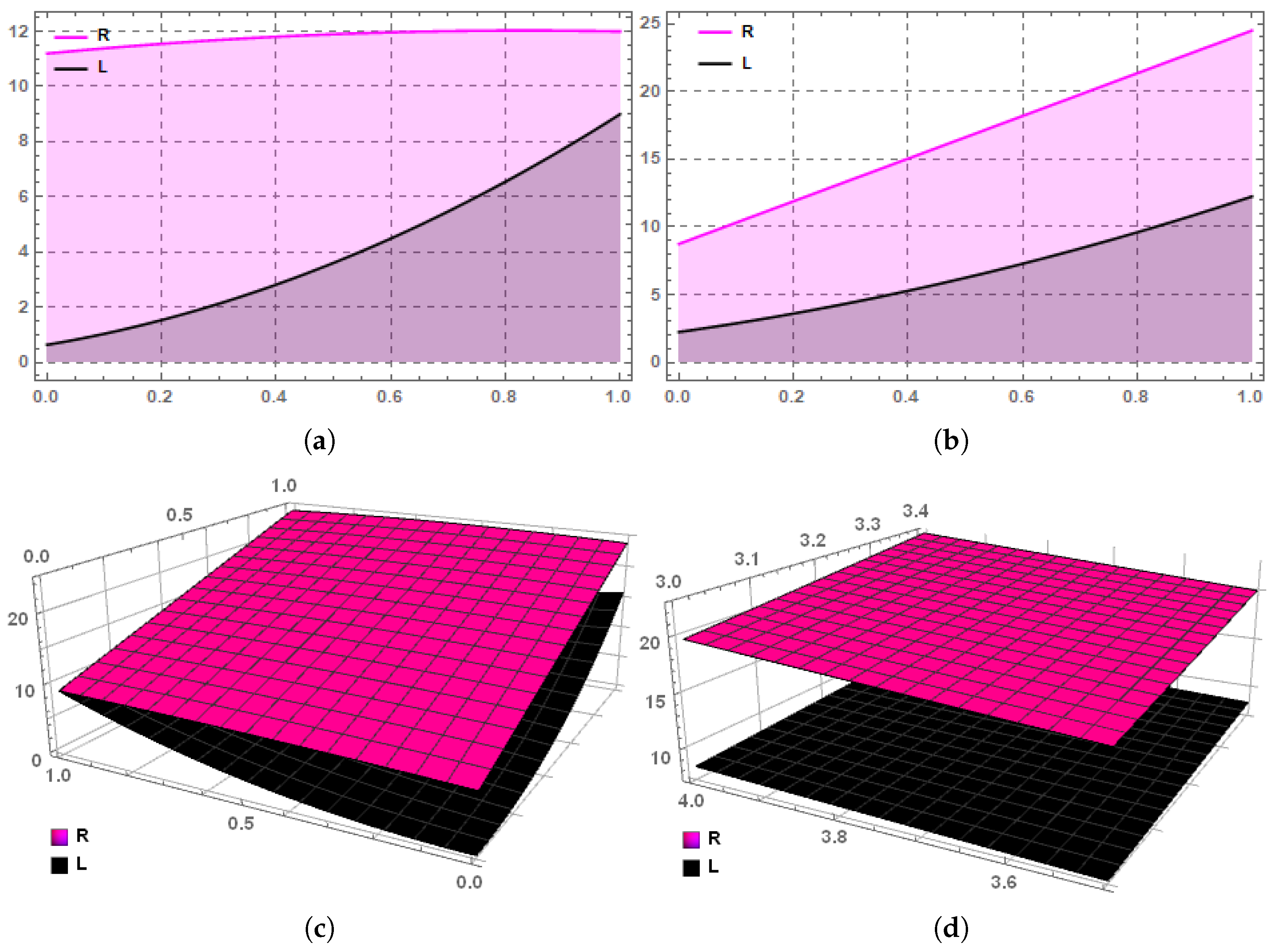

: defined by for is a (P, m)-superquadratic stochastic process for every . The graphs in Figure 1 illustrate the validity of Definition 14 via the process Ψ

considering different values of the parameters that go into it. Let R and L denote the right and left sides of the expression (14) respectively. It has been shown in the in Figure 1 that pink color represents the right term of the Definition 14 while black color represents the left term of the Definition 14. We noticed that for various values of the parameters m, and and β, the pink color always occurs above the black color. It implies that the Definition 14 holds true. Next, we investigate the core properties that define and characterize (P, m)-superquadratic stochastic processes.

Proposition 1. If are (P, m)-superquadratic stochastic processes, then and , where are (P, m)-superquadratic stochastic processes.

Proof. Let

and be (P, m)-superquadratic stochastic processes, we have

and

now

Thus we have

Similarly

Thus we have

Therefore, (

15) and (

16) jointly imply that both

and

satisfy the definition of m-superquadratic stochastic processes. □

Proposition 2. Let be the (P, m)-superquadratic stochastic processes, then is a (P, m)-superquadratic stochastic process.

Proof. Since one derives that

Consequently,

is a (P, m)-superquadratic stochastic process. □

Theorem 6. Let be a (P, m)-superquadratic stochastic process and for all , thenholds, for every . Proof. Let the stochastic process

is a (P, m)-superquadratic, then

Setting

Next putting

and

in (

20), we get

Substituting

,

and

in (

19), we get

It implies that

Inequality (

21) can be written as follows

Hence this concludes the proof. □

Next we provide the proof of an inequality of Jensen’s type for (P, m)-superquadratic stochastic processes.

Theorem 7. Let be a (P, m)-superquadratic stochastic process thenholds , such that , where . Proof. We prove this result by using the principle of mathematical induction, therefore by taking

in (

23), we have

Which reflects the Definition 14. Thus the statement (

23) is true for

= 2.

Next we assuming the validity of (

23) for

, it follows that:

now let us prove that (

23) is valid for

where

, then it implies that

using (

24) in (

25), then we obtain

Hence the proof. □

Theorem 8. The following statements are true for and ∀ , , and

- 1.

, where =Set of (P, m)-superquadratic stochastic processes.

- 2.

The process Ψ holds the result given below: - 3.

For , the process Ψ holds the inequality given below: - 4.

For the inequality given below holds:

Proof. It is straightforward that (1) ⇔ (2) ⇔ (3) and (3) ⇔ (4). Since

there exists a scalar

such that

. Consequently, the following results can be established.

Since it follows that

Hence, (4) is satisfied (4) ⇒ (1). In view of the assumption

it can be applied to

Hence the proof. □

Next we offer the ’s inequality for (P, m)-superquadratic stochastic processes.

Theorem 9. Let Ψ

: be a mean-square integrable (P, m)-superquadratic stochastic process, thenholds and . Proof. Since

is a (P, m)-superquadratic stochastic process therefore we have

Replacing

by

and

by

in (

27), we get.

After mean-square integration of (

28) w.r.t

over

, we have

It implies after change of variables and simple calculations that

Thus

Since

is an (P, m)-superquadratic stochastic process, it follows that

integrating (

30) w.r.t

over

and after simple calculation and change of variables we get

Combining (

29) and (

31), we get what we want. □

Corollary 1. When the inequality in (

26)

is reversed, it gives rise to an inequality of -type characterizing (P,m)-subquadratic stochastic processes. To verify Theorem 9, we present the following example involving (P,m)-superquadratic stochastic process.

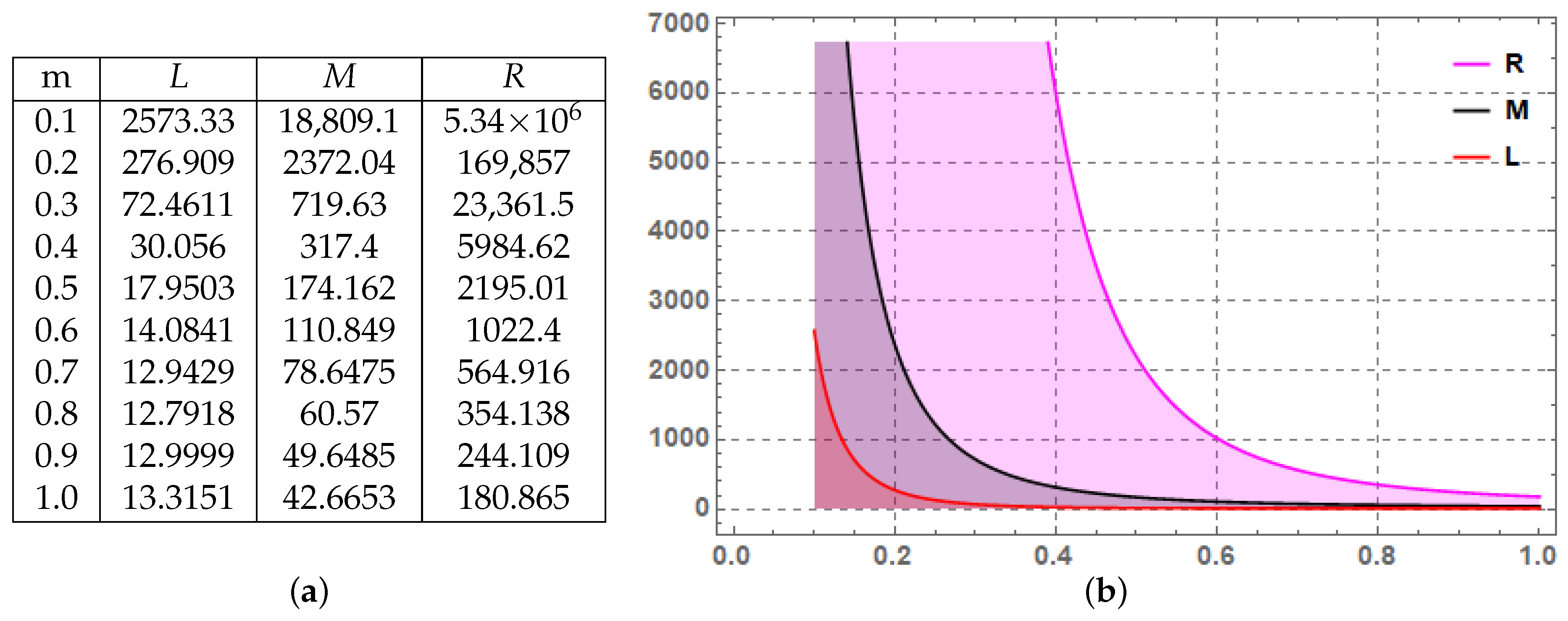

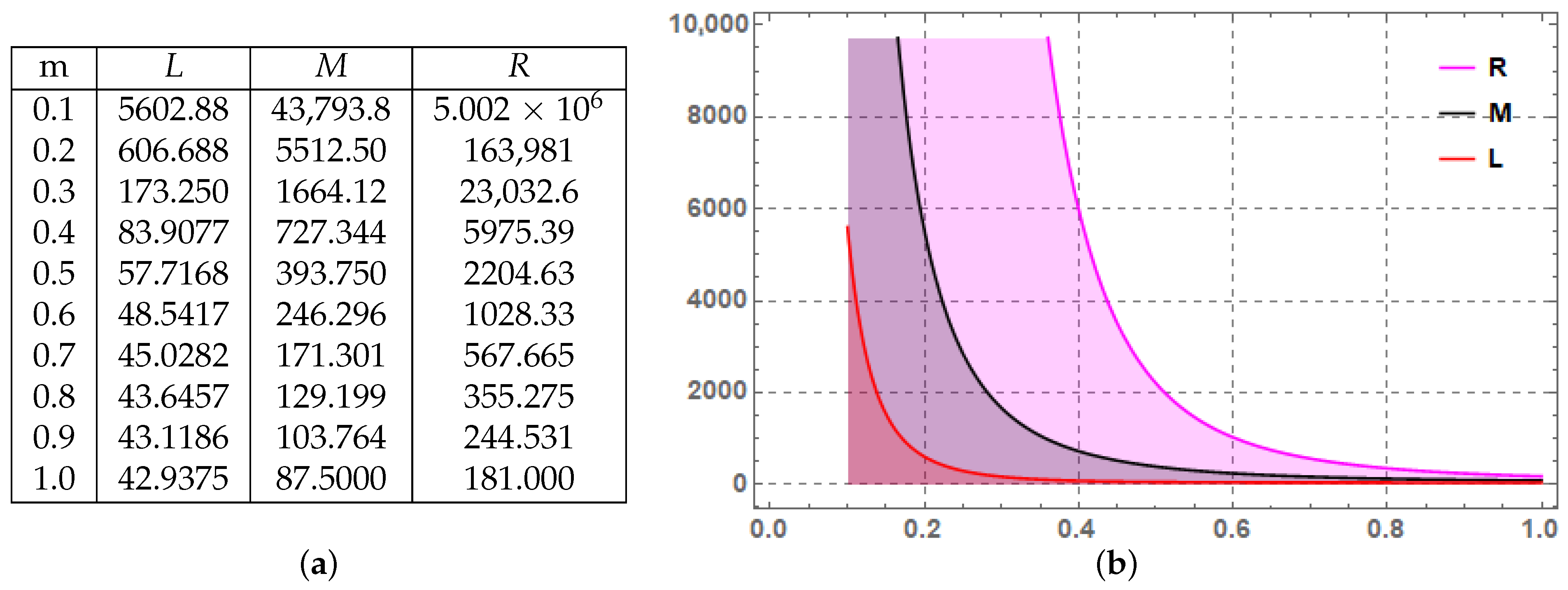

Example 4. Consider the same process as given in Example 3, then we have the Figure 2a,b given by Figure 2, depict the right, middle and left terms, which are denoted by R, M and L respectively for Theorem 9. In the aforementioned Example 4, the graph consists of three colors: pink, black and red. Pink, black and red stands for the right, middle and right terms of Theorem 9, respectively. It is obvious from Theorem 9 that right term is always greater than the middle and middle term is greater than the left term, therefore the graph’s pink color always occur above the black, and black always occur above the red color for various values of the parameters involved in it. This graphically confirms that the established result is true.