1. Introduction

Hydrocarbon resources in shale are a significant component of unconventional oil and gas resources [

1]. The successful implementation of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing technologies in North America has been the catalyst for the global petroleum industry revolution, with particularly remarkable achievements in the development of marine shale oil plays, resulting in substantial increases in both production and reserves. In contrast to North America, China’s shale oil resources are discovered in the continental lacustrine strata of Permian to Cretaceous periods [

2,

3]. Continental lacustrine basins include both rift basins and sag basins [

4,

5,

6]. For example, the Cretaceous Qingshankou shale in the Songliao Basin and the Permian Fengcheng and Lucaogou shale in the Junggar Basin were deposited in rift basins, whereas the Jurassic lacustrine shales in the Sichuan Basin accumulated in a sag basin [

7,

8,

9]. Reported cases indicate that the interaction between tectonics and sedimentation in lake-basins is significant [

10,

11,

12], which results in notable differences in hydrocarbon enrichment and exploitation potential among distinct structural units and sedimentary facies within the basins [

13,

14].

By the end of 2024, more than 1500 horizontal wells for continental shale oil had been completed in China, with annual production exceeding 6.1 million tons, making a significant contribution to the stability of the country’s crude oil output [

15]. However, the vertical heterogeneity in lithology and composition of lacustrine shales leads to rapid and uneven changes in shale oil content and composition [

16,

17], complicating the prediction of geological sweet spots. As the primary reservoir for shale oil, the pore characteristics and fluid storage states in shale formations are crucial for the extraction and production of shale oil [

18,

19]. The pore structure in oil shale is complex, encompassing various types at nanoscale, microscale, and macroscopic levels, all of which relate to the storage and movement of oil [

20]. Additionally, shale oil exists in various forms within shale reservoirs. The movable portion primarily resides in inorganic pores or fractures as free shale oil, while adsorbed shale oil clings to mineral surfaces or organic matter, which complicates large-scale production. The storage states of different fluids directly impact the extraction efficiency and production capacity of shale oil. Previous studies have largely focused on the macro-scale prediction of high-quality lacustrine shale reservoirs [

17,

18,

19]. While the spatial distribution of fractures is also recognized as significant for oil and gas flow, there is a lack of fluid analysis results for microscale pore-fracture. Consequently, the impact of pore-fractures on oil storage and migration has been overlooked.

Unlike carbonate and sandstone reservoir [

21,

22], oil shale exhibits dual characteristics as both reservoirs and source rocks. This results in a diverse range of pore structures, irregular pore-size distributions, and complex inter-pore connectivity. In terms of research methods, scholars, both domestically and internationally, often utilize various microscopic imaging techniques to qualitatively assess the developmental features of these reservoirs at the pore scale [

23]. Field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) is a widely applied two-dimensional method for pore characterization, offering a broad pore-size coverage, high magnification, large depth of field, wide viewing area, and relatively simple sample preparation. Owing to these advantages, FE-SEM has been extensively applied to the characterization of nanoscale pore structures [

24]. In contrast, three-dimensional observation methods, such as focused ion beam scanning electron microscopy (FIB-SEM) and X-ray computed tomography (CT), enable three-dimensional reconstruction of pore networks, allowing for more accurate characterization of pore morphology and connectivity across different pore types [

23,

25]. In addition, low-temperature nitrogen adsorption (LTNA) and mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) are commonly employed to quantify pore volume (PV), pore-size distribution (PSD), and specific surface area (SSA) in hydrocarbon reservoirs [

26,

27]. Due to fundamental differences in experimental principles, these methods differ in their applicable pore-size ranges and measurement precision. MIP relies on externally applied pressure to force mercury into pore spaces by overcoming surface tension, making it particularly suitable for characterizing mesopores and macropores. In contrast, gas adsorption techniques are based on capillary condensation and volumetric equivalence principles and are more effective for the characterization of micropores to mesopores. Integrating data from both methods provides a comprehensive full-scale pore-size characterization, which is regarded as one of the most effective experimental approaches for investigating shale nanopore systems. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) technology characterizes pore systems by applying an external magnetic field and analyzing the relaxation behavior of H nucleus within fluid, thereby enabling evaluation of pore connectivity, fluid content, and pore-size distribution [

2,

28]. Furthermore, when combined with drying and stepwise centrifugation experiments, NMR techniques can distinguish fluid occurrence characteristics within different pore-size ranges [

29].

Previous studies have established a consensus on the micro-pore structures of lacustrine shale. The interplay between inorganic pores, fracture networks, and the evolution of OM plays a crucial role in controlling the presence of oil. During the early to mid-maturity stage (Ro values of 0.4% to 1.0%), IP, such as intergranular pores between quartz and dissolution pores, accounts for 70% to 80% of the total space [

1,

2,

3]. Rigid inorganic mineral frameworks play a crucial role in the preservation of organic matter and the development of organic matter–hosted pores. Bedding-parallel fractures and shrinkage fractures not only provide effective storage space for shale oil and gas but also act as migration pathways, thereby improving shale reservoir quality [

30,

31]. Hu et al. [

32] reported that, within small-scale lithofacies assemblages of Jurassic oil shale intervals in southwest China, millimeter-scale laminae and centimeter-scale thin-bedded calcitic shell fragments exhibit well-developed intragranular pores, commonly infilled with dark organic matter, which can serve as an effective storage space for hydrocarbons. Wei et al. [

33] emphasized that clay mineral-dominated laminae are the primary contributors to OM enrichment and pore scale in shales, exhibiting the highest hydrocarbon generation potential and hydrocarbon-bearing capacity, whereas felsic detrital laminae supply brittle minerals and contribute positively to reservoir quality by enhancing constructive storage properties. However, the existing studies lack an in-depth exploration of the migration laws of lacustrine shale oil, and the understanding of the control relationship between pores and fluids is insufficient, which restricts the optimization of exploration and development technologies. Secondly, the differences in occurrence mechanisms between the shale oil of the Da’anzhai Member and other lacustrine shale oils have not been clarified, and a refined occurrence model suitable for this area has not been established. The application of fractal theory in the coupling analysis of the internal structure and oil-bearing state of lacustrine shale is not systematic, and a universal evaluation method has not been formed.

Based on the above contents, this study, through the combined technology of gradient centrifugation and gradient drying NMR, clarifies the pore-size boundaries of three occurrence states of shale oil in the Da’anzhai Member for the first time, filling the gap in the research on the microscopic occurrence mechanism in this area. On this basis, a quantitative relationship model between fractal dimension and shale oil occurrence state is established, and the control mechanism of pore complexity on fluid mobility is revealed. Finally, by comprehensively utilizing the synergistic effect of OM abundance, mineral composition, and internal structure, a multi-factor coupled shale oil occurrence control model for this area is constructed, which provides a new theoretical support for the evaluation and development of similar lacustrine oil shale. In addition, the results of this study also have comparative reference value for the oil shale exploration and exploitation of other lake-basins in China, such as Songliao and Junggar Basins.

3. Samples and Methods

3.1. Sample

Eight core samples from the Da’anzhai shale in the Central Sichuan Basin were collected for experiments of internal structure and pore-fluid classification. During the sample collection process, sedimentary facies belts and lithological variations were comprehensively considered. The collected samples encompass three representative lithofacies types: (1) black to dark gray massive shales deposited in deep- to semi-deep lacustrine settings; (2) dark gray to gray shales frequently interbedded with thin- to medium-bedded shell layers, corresponding to the marginal zones of high-energy shell shoals or shallow-lacustrine microfacies; and (3) shale intervals containing shell-rich laminae developed in low-energy shell shoal microfacies. Collectively, these samples cover major shale lithotypes of the Da’anzhai shale and faithfully capture its typical sedimentary characteristics (

Table 1).

3.2. Experiments

These samples were crushed to <100 mesh and weighed 3 g. The powder samples were reacted with acid for 24 h to remove carbonate components and dried at 100 °C for 24 h. Then, TOC contents were determined by a Var10EL-III Elemental Analyzer, produced by Element (Berlin, Germany). The mineral composition experiment was conducted at the China Petroleum Exploration and Development Research Institute by a Rigaku X-ray diffractometer, produced by Rigaku (Tokyo, Japan).

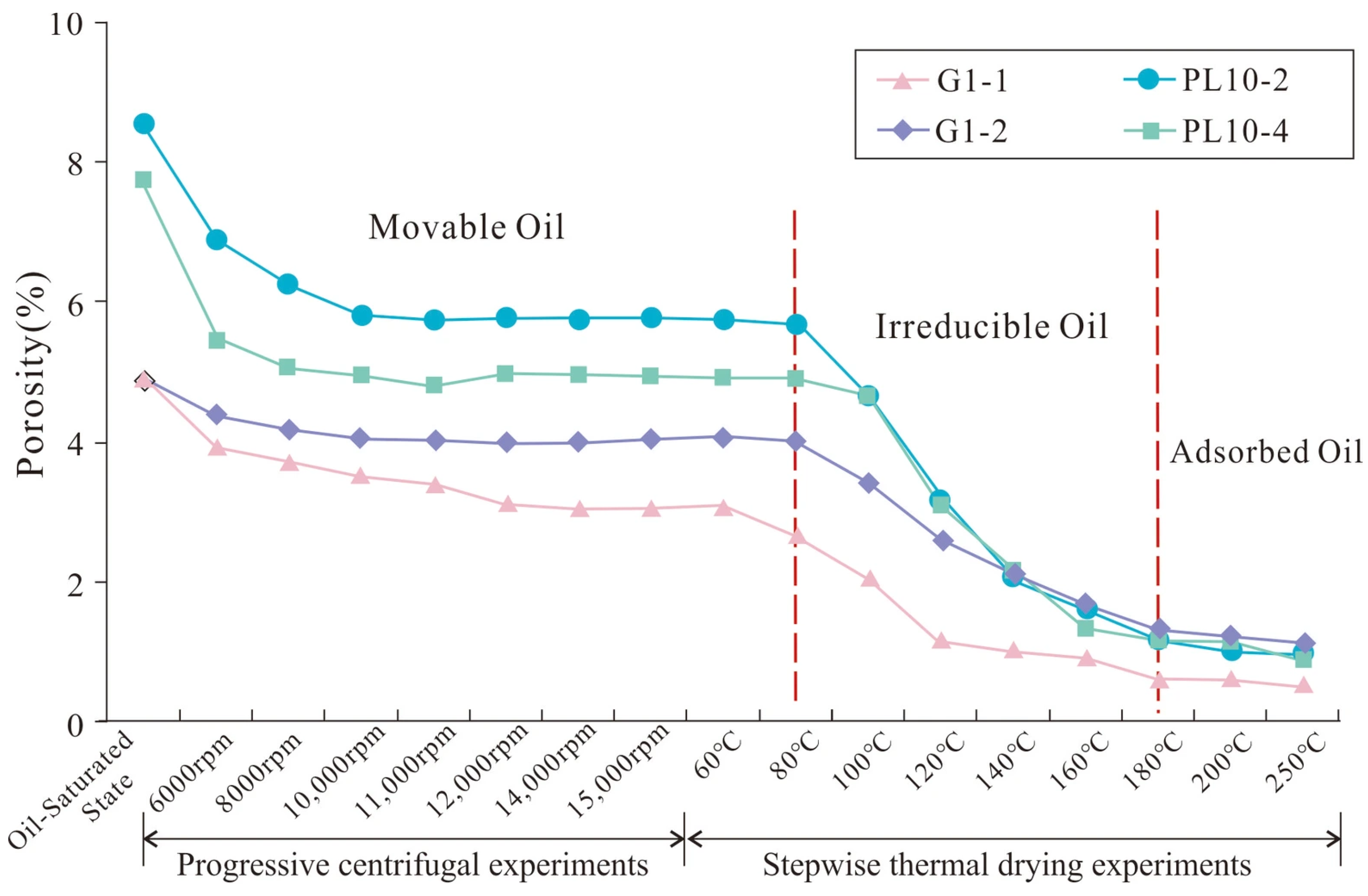

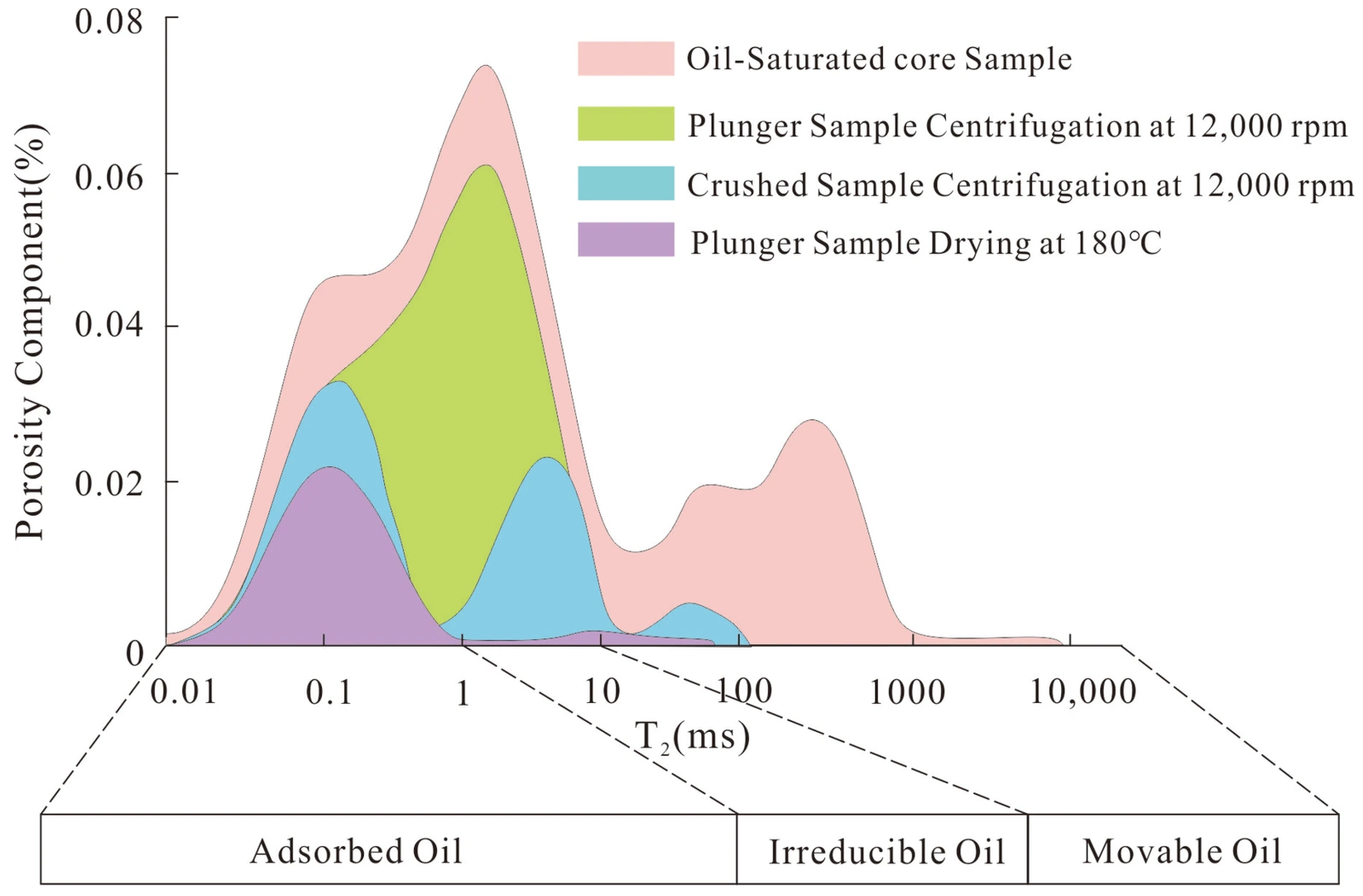

Based on the types of occurrence and flow behavior, shale oil can be categorized into two types: movable part and immovable part. The occurrence types of shale oil are classified as free oil and adsorbed oil. Free oil includes bound oil, which flows with difficulty due to capillary forces and other constraints, and movable oil, which can flow freely under reservoir conditions. Adsorbed oil typically resides on the surfaces of OM and minerals, making it difficult to extract due to the effects of surface adsorption energy. According to these classification criteria, movable oil refers to the easily flowable portion of free oil, while immovable oil encompasses adsorbed oil and bound oil within free oil. Movable oil is the portion that can be effectively extracted. In this study, the NMRC12-010V NMR nanopore analyzer (produced by Suzhou Numag Technology Company, Suzhou, China) was utilized to conduct the analysis. The experiment was conducted at a controlled temperature of 30 °C. The testing parameters were set as follows: echo time of 0.055 ms, number of echoes at 12,000, number of accumulations at 64, and a waiting time of 4000 ms. The centrifugation experiments were carried out using the LG-25M ultra-centrifuge (produced by Sichuan Shuke Instrument Company, Chengdu, China) with a maximum speed of 21,000 rpm. To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of the experimental data, dimethyl silicone oil was used prior to NMR measurements to calibrate the NMR frequency offset and pulse width of the instrument. The following quality control procedures were implemented in this study: measurement stability was assessed through ten repeated tests, for which the relative deviation of the first echo amplitude was required to be less than 3%, corresponding to a relative deviation of less than 3% for the standard reference sample. For the measured rock samples, the relative deviation of the NMR first echo amplitude was required to be less than 5%.

3.3. Fractal Dimension Calculation Based on NMR Data

The analysis of shale pore fractal characteristics is primarily based on fractal geometry theory, which provides an effective framework for describing self-similar and irregular structures. In characterizing shale pore systems, the fractal dimension (D) is commonly used to quantitatively evaluate pore geometric complexity and surface morphology. Multiple experimental techniques, combined with corresponding fractal models, have been widely applied to characterize internal structure and heterogeneity. Fractal analyses based on LTNA primarily target micro- and mesopores, typically using the Frenkel–Halsey–Hill (FHH) model to fit adsorption isotherms and calculate dimensions (D1 and D2). This approach effectively describes nanoscale pore surface roughness and structural complexity. MIP, often coupled with the Menger sponge model and the Washburn equation, is used to construct fractal models for macropores, providing insight into pore geometry, connectivity, and permeability. Hydrogen relaxation in NMR depends on pore surface roughness and complexity within the shale matrix. Accordingly, NMR T2 curves of hydrogen-bearing fluids can be used to obtain fractal dimensions and characterize pore surface features. NMR techniques exploit the relationship between relaxation time spectra and pore-size distributions, and, combined with the power-law behavior of fractal systems, allow for the construction of fractal models for shale pore networks. The D value typically ranges from 2 to 3. Values approaching 2 indicate simpler pore structures with smoother surfaces, whereas values nearing 3 indicate highly complex and heterogeneous pore systems.

The application of fractal theory enables more accurate characterization of the spatial distribution, connectivity, and heterogeneity in reservoir pores, supporting the precise assessment and development of shale reservoirs. In the Da’anzhai lacustrine shale, the lower limit of industrially recoverable pore size has been determined as 30 nm, and the lower threshold for pores containing movable oil is 350 nm. This range is well within the detection window of NMR (10 nm–10 μm). Accordingly, this study integrates NMR measurements with fractal modeling to investigate microscopic pore structure characteristics. Reservoir heterogeneity is evaluated by analyzing the NMR T2 spectra of oil-saturated shale samples and by calculating the corresponding fractal dimensions.

Fractal models for reservoir pores generally include two types: the box-counting model and the real PSD model. In the latter [

34], the

D value is determined using the following equation:

r represents the pore radius (nm).

represents the maximum pore radius.

represents the PSD density function.

is the number of actual pores smaller than

r. The three-dimensional fractal model of pore structure based on NMR and the real pore-size distribution model is typically established using Equation (1) as the foundation [

35]:

In this formula, refers to the transverse relaxation time of the sample (ms). represents the cumulative fraction of PV with less than or equal to a given value. The data are segmented and fitted in double-logarithmic coordinates versus to determine the fitting range for different pore-size intervals. Linear regression is then performed on each segment using the least squares method, and the coefficient of determination (R2) is calculated to retain the most reliable fits. Finally, the D for each PSD interval is obtained directly from the slope of the corresponding fitted line.

5. Discussion

5.1. Control Factors of Shale Oil Occurrence State

The occurrence of shale oil is a critical factor that restricts the exploration, development, and evaluation of unconventional hydrocarbon resources. In the Sichuan Basin, the fluid occurrence in the Jurassic Da’anzhai Formation shale can be classified into three types: movable oil, bound oil, and adsorbed oil. These different types of shale oil are primarily distributed within nanopores and microfractures. Numerous studies indicate that the oil occurrence is influenced by various geological conditions, with the petrophysical characteristics of the shale reservoir, pore structure, and fluid properties being the main factors. Specifically, factors such as OM abundance, mineral composition, and pore structure determine the oil occurrence and influence the migration patterns of fluids during development. Therefore, systematically studying the factors and mechanisms that influence the oil occurrence is crucial for its exploration and exploitation.

5.1.1. Organic Matter Abundance

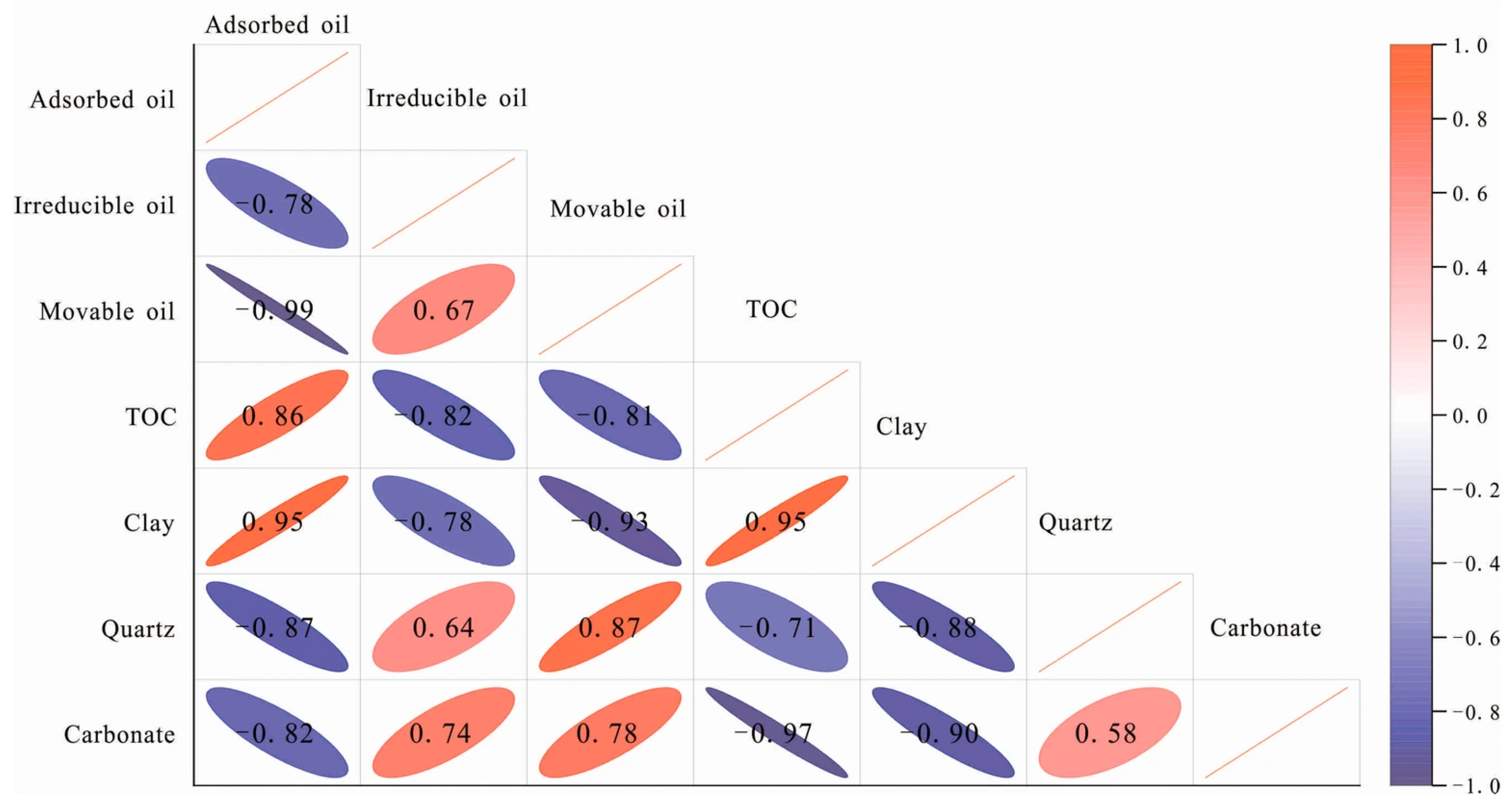

The OM abundance is one of the key geological factors controlling the occurrence of shale oil. OM influences the hydrocarbon generation potential, the development of reservoir porosity, and the adsorption capacity of shale, thereby constraining the occurrence and distribution characteristics of shale oil. An analysis of the correlation between the oil occurrence and total organic carbon (TOC) content in the Da’anzhai shale indicates a clear relationship between TOC levels and the different occurrences of shale oil (

Figure 7). TOC is positively correlated with adsorbed-oil content, with a correlation coefficient of R

2 = 0.86. This is attributed to the higher clay mineral content and well-developed OMPs in high TOC shales. Clay minerals exhibit strong adsorption abilities, which complicate the flow of shale oil and provide more space for the accumulation of adsorbed-oil. Conversely, TOC shows a negative correlation with movable oil and bound oil, with correlation coefficients of R

2 = 0.82 and R

2 = 0.81, respectively. In high TOC shales, OMPs are often isolated, and the complex pore structure along with lower pore connectivity restricts the migration of movable oil. Thus, the influence of TOC on the oil occurrence is dual-faceted. On one hand, higher TOC levels can generate more shale oil, which may increase the amount of movable-oil to some extent. On the other hand, the high quantity of OM, similar to clay minerals, has a strong adsorption capacity, leading to the accumulation of adsorbed-oil, which hinders the flow of shale oil.

5.1.2. Mineral Composition of Lacustrine Shale

The mineral composition of shale is a key factor that influences the oil occurrence. Different types of minerals significantly affect the shale oil occurrence and distribution by altering the internal structure, mechanical properties, and fluid-rock interactions within the shale. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the mechanisms by which various mineral components in shale influence the occurrence of shale oil differ significantly. The unique layered structure of clay minerals, characterized by a high SSA and surface activity, enhances the storage of adsorbed-oil. In contrast, brittle minerals like quartz affect the storage capacity and migration efficiency of movable oil by controlling the brittleness index and the extent of fracture development in the shale. The influence of mineral composition on the occurrence of shale oil is both multi-scaled and complex. Different minerals further impact the dynamic distribution of fluids during development by altering the mechanical properties and pore structure. This study focuses on the control mechanisms of clay and brittle minerals on the oil occurrence and their geological significance. By integrating experimental analysis with theoretical models, it reveals the intrinsic relationship between mineral composition and shale oil occurrence, providing a scientific basis for the evaluation and efficient exploitation of shale oil reservoirs.

The content of clay minerals shows a negative correlation with both movable and bound oil content (

Figure 7), with a particularly strong negative correlation for movable oil, indicated by correlation coefficients of R

2 = 0.93 and R

2 = 0.78, respectively. In contrast, an obvious positive correlation exists with the content of adsorbed-oil (

Figure 7), with a correlation coefficient of R

2 = 0.95. This study posits that the lacustrine shale contains a significant number of micro- and nanometer-scale pores and microfractures within its clay minerals. These pores offer critical storage space for adsorbed shale oil. The clay minerals possess numerous nanometer-scale pores, characterized by a high specific surface area and strong adsorption capability. Consequently, the flow of shale oil within the reservoir encounters substantial resistance, leading to a decrease in movable oil content. Moreover, the layered structure and development of micropores in clay minerals enhance the complexity of the internal structure, indicating that clay minerals significantly influence the storage state of shale oil.

The quartz content is positively correlated with both movable-oil and bound-oil content (

Figure 7). The correlation between quartz content and bound oil is particularly strong, with correlation coefficients of 0.64 and 0.87, respectively. In contrast, there is a significant negative correlation between quartz content and adsorbed oil, with a correlation coefficient of 0.87. Similar to quartz, carbonate minerals show a positive correlation with movable and bound oil, while exhibiting a significant negative correlation with adsorbed oil (

Figure 7). Brittle minerals, primarily quartz, carbonate, and feldspar, are prone to fracture under diagenetic or tectonic stress, and also generate a large number of complex inorganic pores through dissolution. Consequently, intergranular pores, intragranular pores, and microfractures formed by brittle fractures and diagenesis frequently develop between mineral grains. These secondary pore structures provide effective migration pathways for shale oil that was originally in a bound state. They also offer significant storage space for movable oil, substantially enhancing the flow properties and reservoir capacity of shale oil. As the amount of brittle minerals increases, the mobility of shale oil improves, while the relative content of adsorbed shale oil tends to decrease. This indicates that the pores developed within quartz are conducive to the storage and migration of movable oil. Furthermore, a higher content of brittle minerals in shale reservoirs significantly promotes reservoir development by increasing porosity and permeability, thus providing favorable geological conditions for shale oil extraction. This understanding offers important theoretical insights for the evaluation and development of shale oil reservoirs. Investigating the influence of brittle minerals on the storage state of shale oil can enhance our understanding of its migration mechanisms, providing valuable references for the exploration and development of unconventional hydrocarbon.

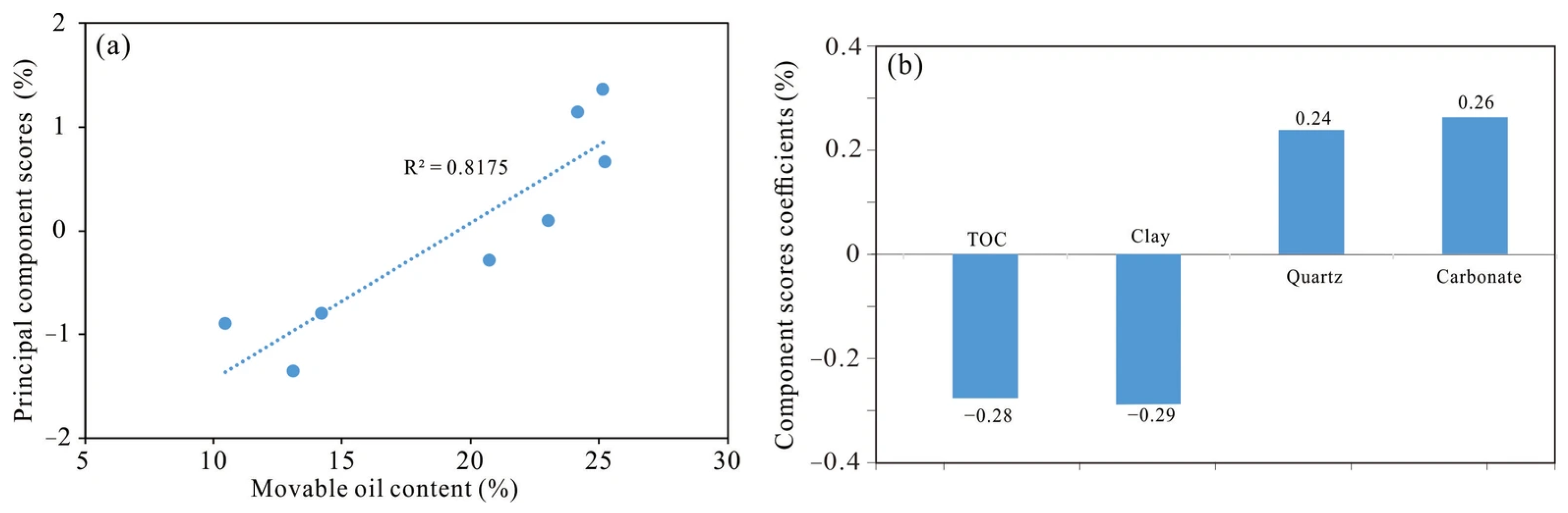

In addition, principal component analysis (PCA) was employed in this study, using clay, carbonate mineral, quartz, and TOC as input variables. Principal component scores were calculated for different samples, and the component exhibiting a strong correlation with movable oil was selected (

Figure 8a), from which the corresponding component score coefficients were obtained (

Figure 8b). The results indicate that high carbonate and quartz contents are favorable for the movable-oil enrichment, whereas high TOC and high clay mineral contents exert a negative influence.

5.1.3. Pore Structure

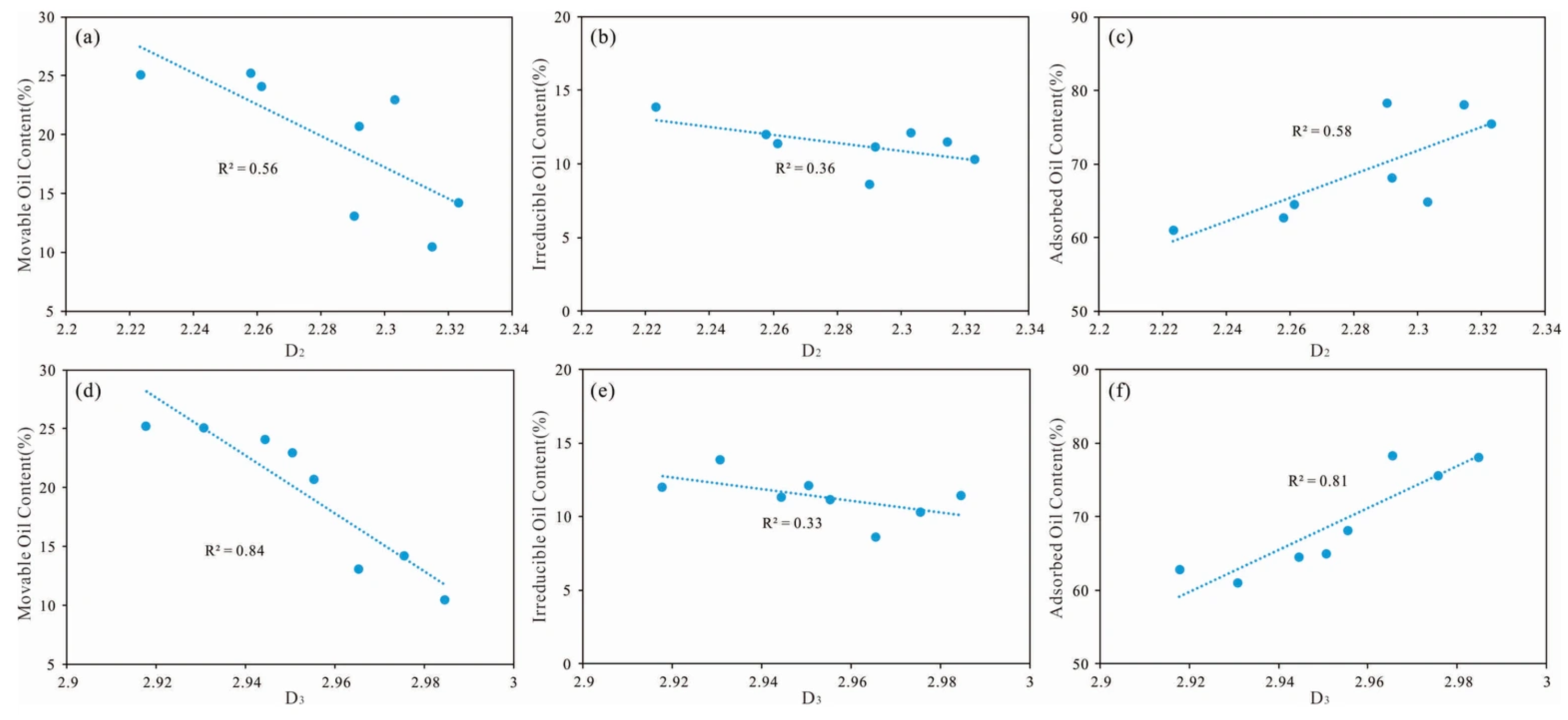

Mineral composition in shale is a crucial factor influencing storage state of shale oil. Its complexity directly affects the oil occurrence and oil-flow behavior. In Da’anzhai shale, macropores exhibit higher fractal dimensions, reflecting more diverse pore types and more complex pore structures, whereas mesopores show lower fractal dimensions, indicating weaker pore heterogeneity. A lower

D2 indicates a simpler internal structure in the lacustrine shale, which favors the storage and migration of movable oil. Conversely, a high

D3 suggests a more complex internal structure with smaller pores, which may be more conducive to the storage of adsorbed oil. The pore structure of lacustrine shale reservoirs is complex and exhibits strong heterogeneity.

D2 is negatively correlated with both movable-oil and bound-oil content, with correlation coefficients of 0.56 and 0.36, respectively (

Figure 9a,b). In contrast,

D2 shows a positive correlation with adsorbed-oil content (

Figure 9c).

D3 is also negatively correlated with both movable-oil and bound-oil content, with correlation coefficients of 0.84 and 0.33, respectively (

Figure 9d,e). Additionally,

D3 exhibits a positive correlation with adsorbed-oil content (

Figure 9f). As the fractal dimension increases, the heterogeneity of the internal structure intensifies, leading to a more complex fluid storage state and potentially reduced fluid migration capacity. An increase in the complexity of the shale pore surface provides greater adsorption space for shale oil, resulting in a significant rise in the amount of adsorbed oil. Conversely, an increase in the fractal dimension indicates the development of more complex pore structures, with enhanced internal connectivity and increased surface roughness, which promotes shale oil adsorption and consequently reduces the proportion of movable oil.

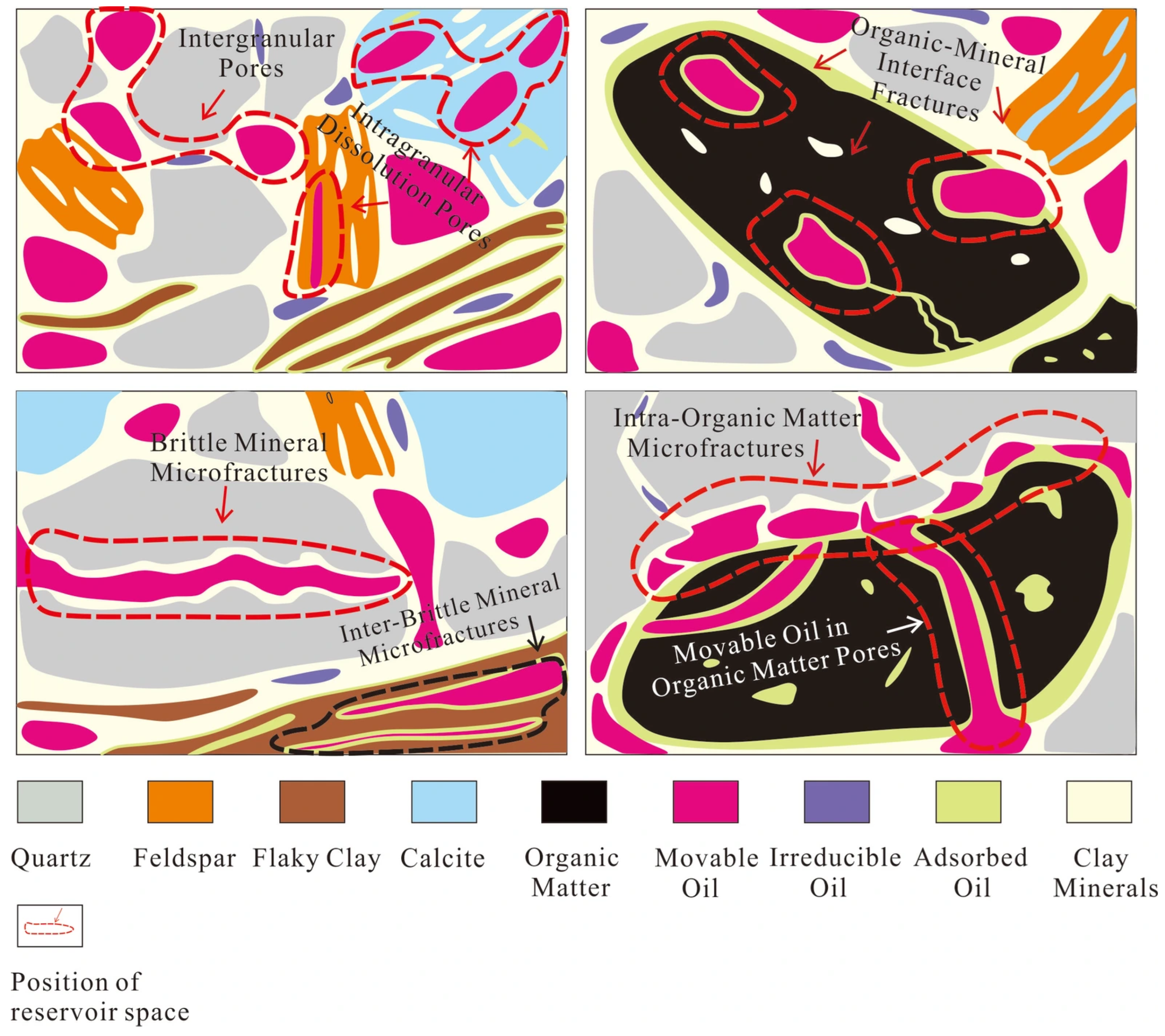

5.2. Model of Shale Oil Occurrence State

The internal structure of shale governs the storage state and migration efficiency of hydrocarbon, directly affecting the distribution patterns and recoverability. This study constructs a model for the storage state in lacustrine shale oil based on a systematic analysis of the OM geochemical characteristics, microscopic structure, and oil storage types of the Da’anzhai Member (

Figure 10). This model systematically reveals how the microscopic pore features of lacustrine shale reservoirs affect various storage states of shale oil, providing theoretical support and guidance for evaluating the resource potential and efficient exploitation of shale oil. As previously mentioned, movable shale oil primarily exists as spherical droplets within pores and micro-fractures larger than 350 nm. The types of pores hosting movable oil mainly include intergranular and intragranular pores associated with brittle minerals, as well as dissolution pores within feldspar or calcite and other inorganic pores. These inorganic pores are well-connected and widely distributed, particularly common in interbedded and thinly layered shale formations. The micro-fractures hosting movable oil exhibit two primary characteristics. The first type is formed by the fracturing of brittle minerals or other dissolution processes. These fractures not only provide pathways for shale oil migration but also serve as major reservoir spaces for hydrocarbon. The second type is OM-related fractures, formed during the thermal evolution of kerogen into oil, where organic matter undergoes significant expansion and contraction, creating organic pores and associated micro-fractures. Additionally, the interface between organic matter and adjacent minerals can form shrinkage fractures, which can be filled with substantial amounts of shale oil. Shale oil located within these pore-fracture configurations exhibits high flow capabilities. For example, some samples contain numerous micro-fractures, resulting in a significantly higher content of movable oil compared to other samples.

Bound oil primarily exists within OMP and IPs ranging from 30 nm to 350 nm in diameter. The bound-oil content shows a certain correlation with the abundance of brittle minerals such as quartz and exhibits a weak positive correlation with fractal dimensions D2 and D3. This characteristic suggests that the storage state of bound oil may be influenced by the pore-fracture system developed in brittle minerals, with the pore structure also playing a significant role in its distribution. Under suitable hydraulic fracturing conditions, it is possible to effectively access the storage spaces of bound oil, facilitating the industrial extraction of shale oil. Adsorbed shale oil exists as a nanometer-thin oil film within pores smaller than 30 nm. Due to the interplay of van der Waals and Coulomb forces, adsorbed oil molecules are densely and orderly arranged on the surfaces of clay minerals or OM, exhibiting physical properties similar to solid hydrocarbons. This unique storage state results in adsorbed oil exhibiting almost no flow capacity, making it challenging to mobilize effectively.

China is rich in oil shale resources. Taking the shale reservoir of the Da’anzhai Member as an example, this paper analyzes the fractal characteristics of pore structure and the controlling factors of oil-bearing occurrence states. Compared with the Qingshankou lacustrine shale in North China, the shale reservoir of the Da’anzhai Member has three occurrence states: movable oil, irreducible oil, and adsorbed oil. Moreover, the movable oil is mainly stored in macropores and microfractures in both. However, the shale in North China has a higher content of brittle minerals and a relatively larger proportion of movable oil, which is related to the difference in mineral composition caused by sedimentary environment. Compared with the Da’anzhai lacustrine shale, the Lucaogou lacustrine shale in the Junggar Basin has the same variation trend of fractal dimension (macropore fractal dimension > mesopore fractal dimension), while the Lucaogou lacustrine shale has relatively lower pore complexity and correspondingly lower proportion of adsorbed oil. The core controlling factors affecting the occurrence state of shale oil (such as OM abundance, mineral composition, internal structure) are universal in other lacustrine shales; as such, this study can provide a reference for the evaluation of the occurrence state of similar lacustrine oil shale.

6. Conclusions

(1) Based on nuclear magnetic resonance experiments conducted under gradient centrifugation and drying, lacustrine shale oil can be classified into three states: movable oil, bound oil, and adsorbed oil. Movable oil is primarily located in microfractures and large pores (>350 nm) within the shale reservoir, making it the main target for industrial extraction. Bound oil is mainly occurred in mesopores and micropores (30 nm to 350 nm) as well as in narrow pore structures between rock grains, and can potentially be developed through engineering measures such as fracturing. Adsorbed oil is tightly bound to the surfaces of OM and clay minerals, making it difficult to release effectively using conventional techniques.

(2) The abundance of OM, the mineral composition of lacustrine shale, and the pore structure collectively influence the occurrence of shale oil. Although a high TOC value increases the amount of movable oil, the strong adsorption characteristics of kerogen and OM lead to the accumulation of adsorbed oil, which inhibits the flow of shale oil. Clay minerals further restrict the flow of shale oil by enhancing adsorption, whereas brittle minerals promote the flow of movable oil by expanding the pore space.

(3) Based on fractal geometry theory and multi-scale testing results, the D value of large pores in lacustrine shale is relatively high, indicating complex pore shapes. However, as pore complexity increases, the amount of adsorbed oil significantly rises, resulting in a decreased proportion of movable oil. D1 represents the D value of micropores in lacustrine shale. Since the effective range for fractal dimensions is between 2 and 3, and D1 falls well below this range, it indicates that the micro-pore system does not exhibit typical fractal characteristics. D2 indicates the D value of pores in the Da’anzhai shale, which lies within the effective range, suggesting that the mesopore system demonstrates clear fractal characteristics. D3 represents the D value of macropores and micro-fractures in lacustrine shale, and also falls within the effective range. The fractal dimension of D3 is significantly higher than that of D2, suggesting that the macropore system is characterized by greater structural complexity and heterogeneity, whereas the mesopore structure is relatively simpler. This finding is closely related to the migration mechanisms of shale oil, as a higher D value reveals that complex internal structures and configurations facilitate the movement of shale oil.