Composite Fractal Index for Assessing Voltage Resilience in RES-Dominated Smart Distribution Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

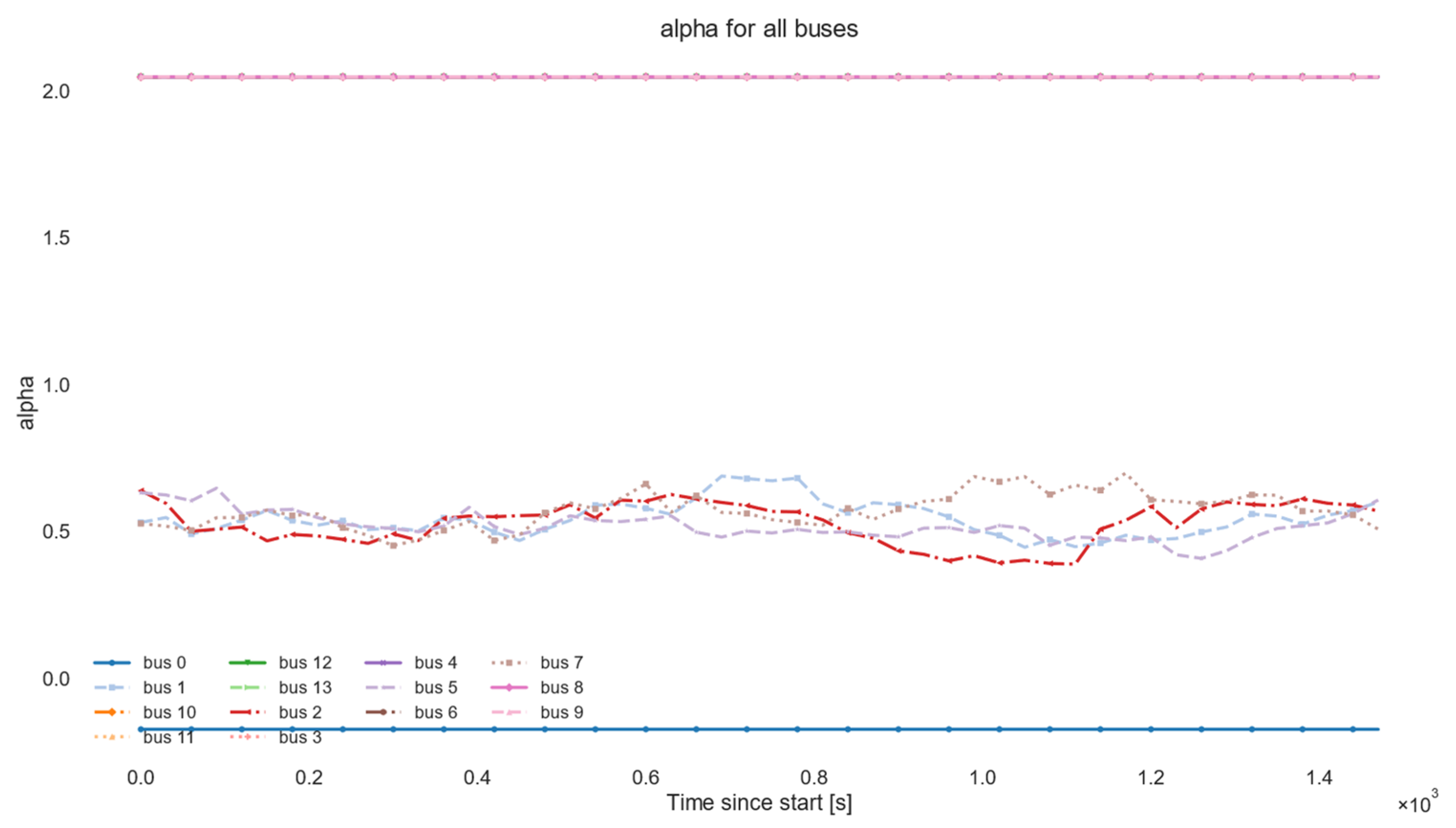

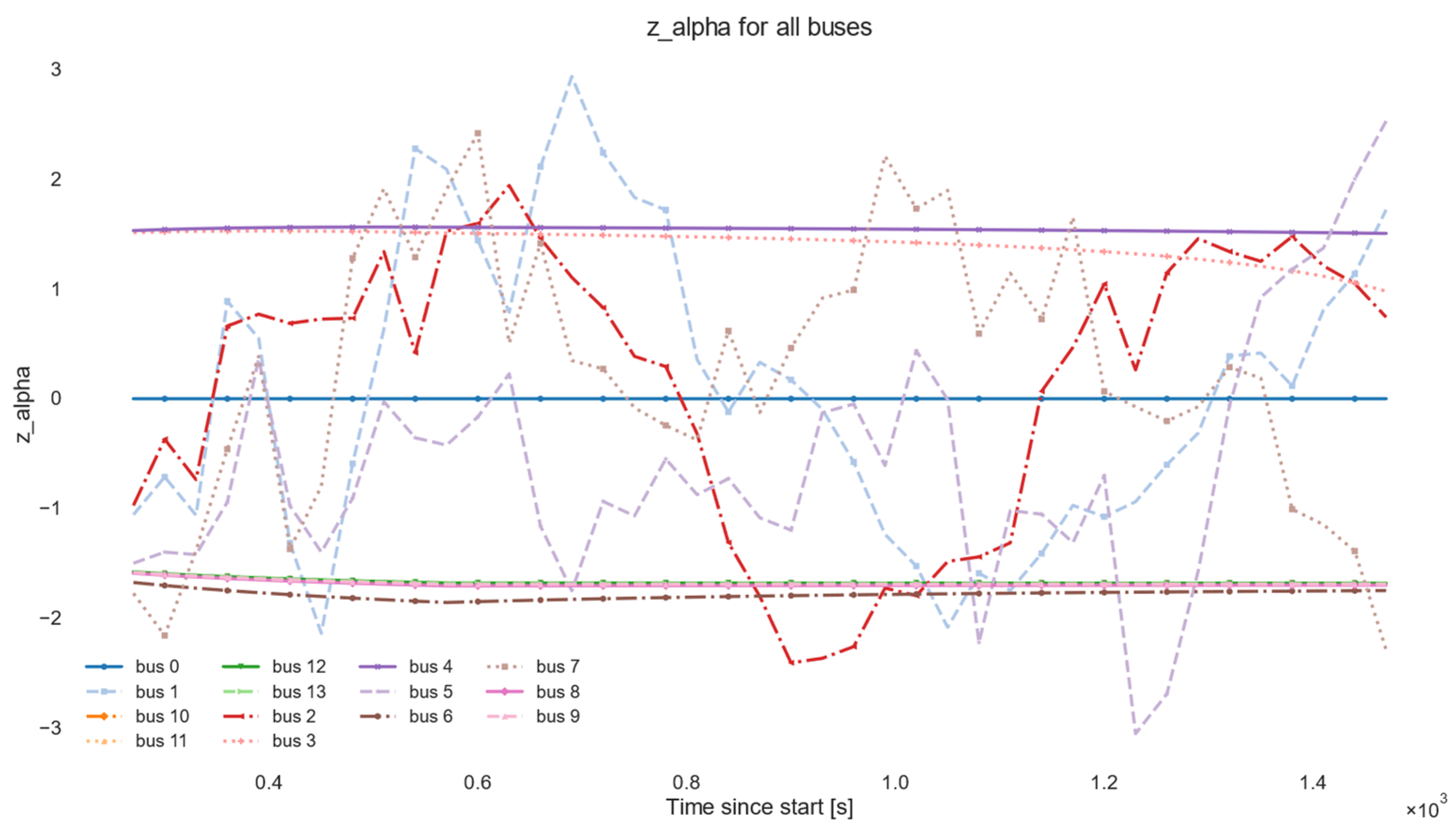

- α from Detrended Fluctuation Analysis (DFA)—a proxy of long-term correlations;

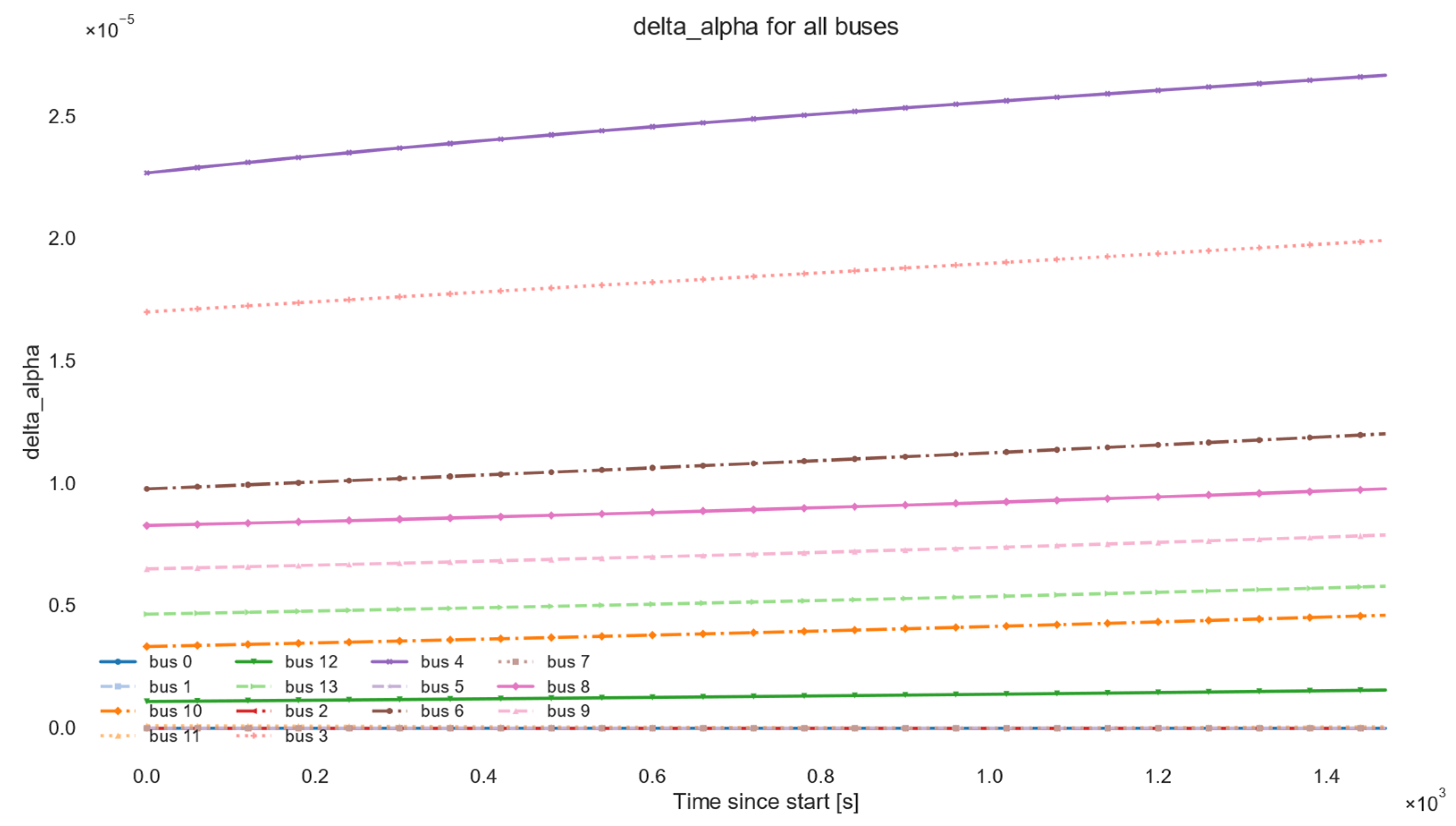

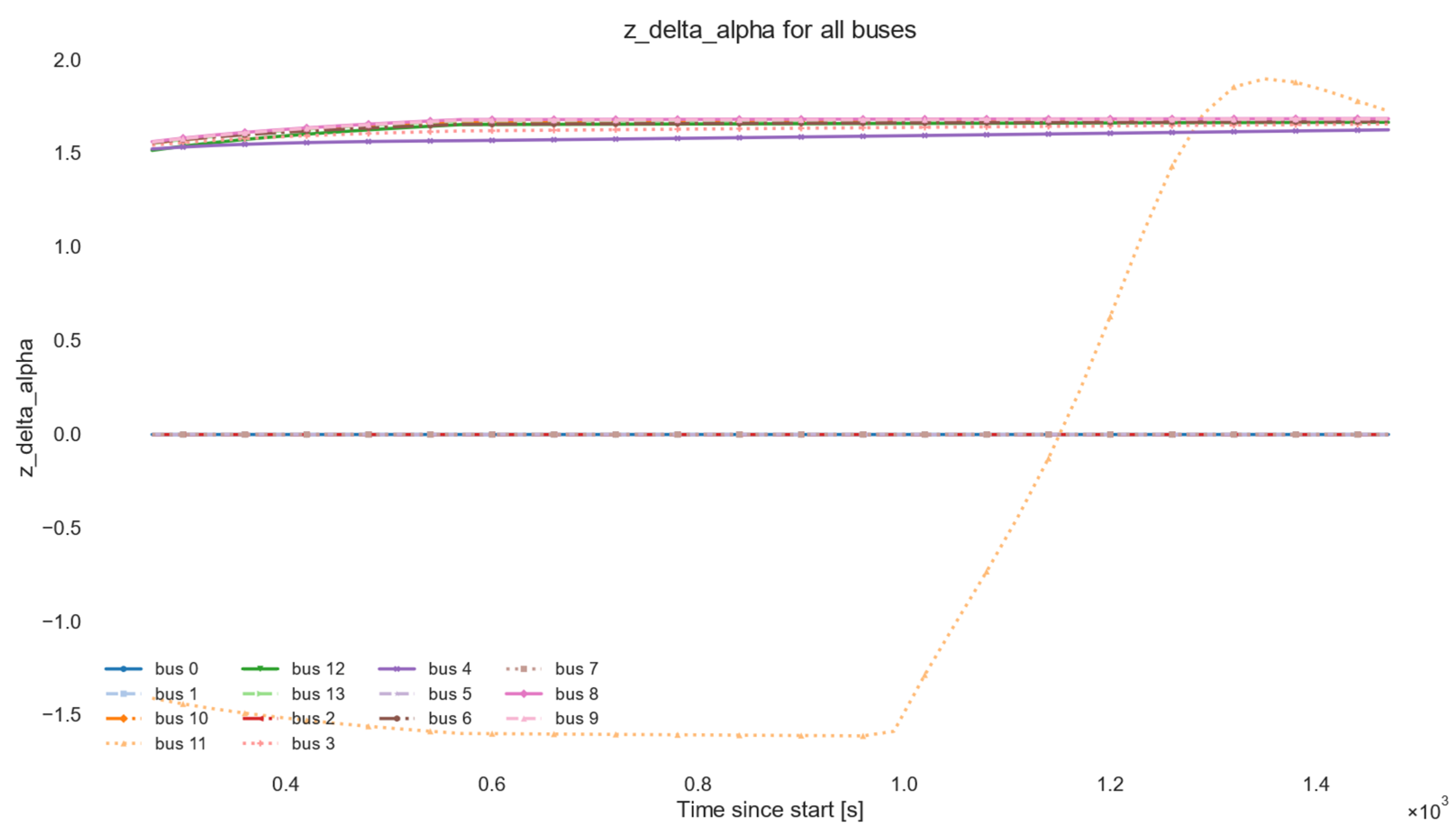

- Δα—the width of the multifractal spectrum from Multifractal Detrended Fluctuation Analysis (MFDFA);

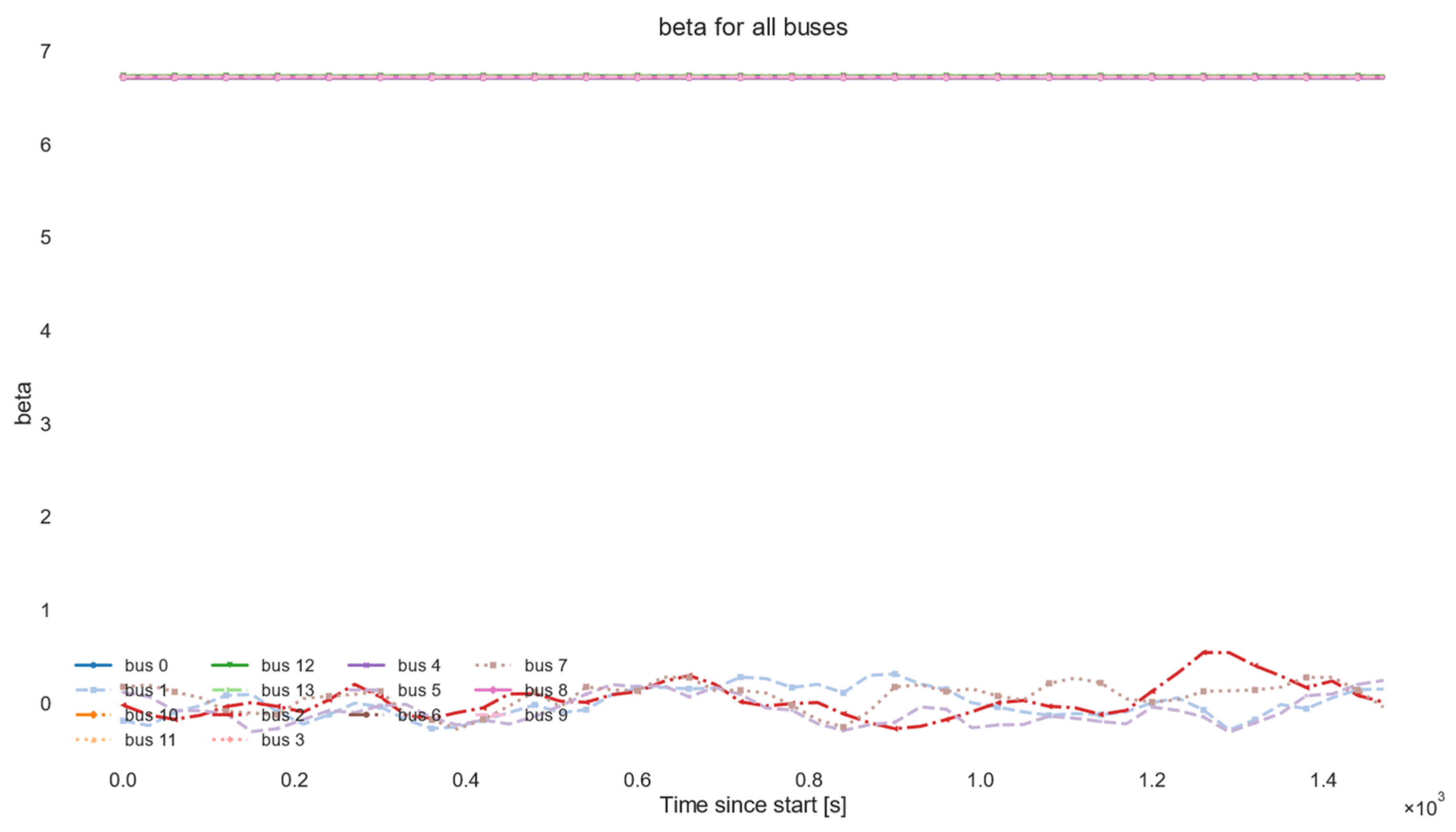

- β—slope of the power spectrum in a given frequency band (1/f “reddening”);

- a classical L-index, all z-scaled and combined into a per-node score.

- (a)

- early warning—fractal signatures grow before static margins are exhausted;

- (b)

- spatial localization by nodes/feeders;

- (c)

- compatibility with existing indices that can be merged for a better balance between sensitivity and specificity.

- A unified per-node composite index (CFI/FVSI_Fr) that merges DFA α, MFDFA Δα, and the spectral slope (β and L-index) into a standardized score for a voltage resilience assessment.

- An online monitoring chain with sliding window estimation, adaptive z-scaling, and change detection, designed to work on PMU/micro-PMU and high-frequency SCADA streams.

- A reproducible implementation in a Python v 3.10 script, as well as guidelines for integration into operational environments and simulations with gradual loading towards the Q–V/P–V “nose”.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Classical Approaches to Voltage Stability Assessment (VSA)

2.2. Data-Driven and Machine Learning (ML) Approaches

2.3. Early Signals from “Complex Systems”: Critical Delay

2.4. Fractal and Multifractal Methods for Variability Analysis

2.5. Literature Gap and Motivation for a Composite Fractal Index

3. Methodology: Composite Fractal Index (CFI/FVSI_Fr)

3.1. Notation and Data Model

3.2. Fractal and Spectral Observables

3.2.1. DFA Exponent α

3.2.2. Multifractal Width Δα (MFDFA)

3.2.3. Spectral Slope β

3.3. Standardization and Composition

3.4. Change Detection and Alarm Rules

3.5. Parameter and Scale Selection

- Intervals/step: .

- Scales S: log-uniform, in seconds where ; in samples and Ns ≥ 4 is required.

- Moments Q: symmetric set, {−3, −2, …, 2, 3}.

- Frequency band: for PMU; adaptation according to .

- Minimum samples: .

- Z-window: steps.

3.6. Numerical Robustness and Missing Data

3.7. Computational Complexity

4. Online Computational Pipeline, Windows, and Thresholding

4.1. General Scheme

4.1.1. Preprocessing

- detrend (polynomial order m, usual m = 1);

- outlier suppression (Hampel, window , threshold nσ);

- check for minimum samples M ≥ Mmin.

4.1.2. Feature Extraction

- DFA αi,t on scales S (in samples) with the condition Ns ≥ 4 s ≤ M/4.

- MFDFA width Δαi,t through Q {−3, …, 3}.

- Spectral slope βi,t from regression of logP(f) on [fmin, fmax]

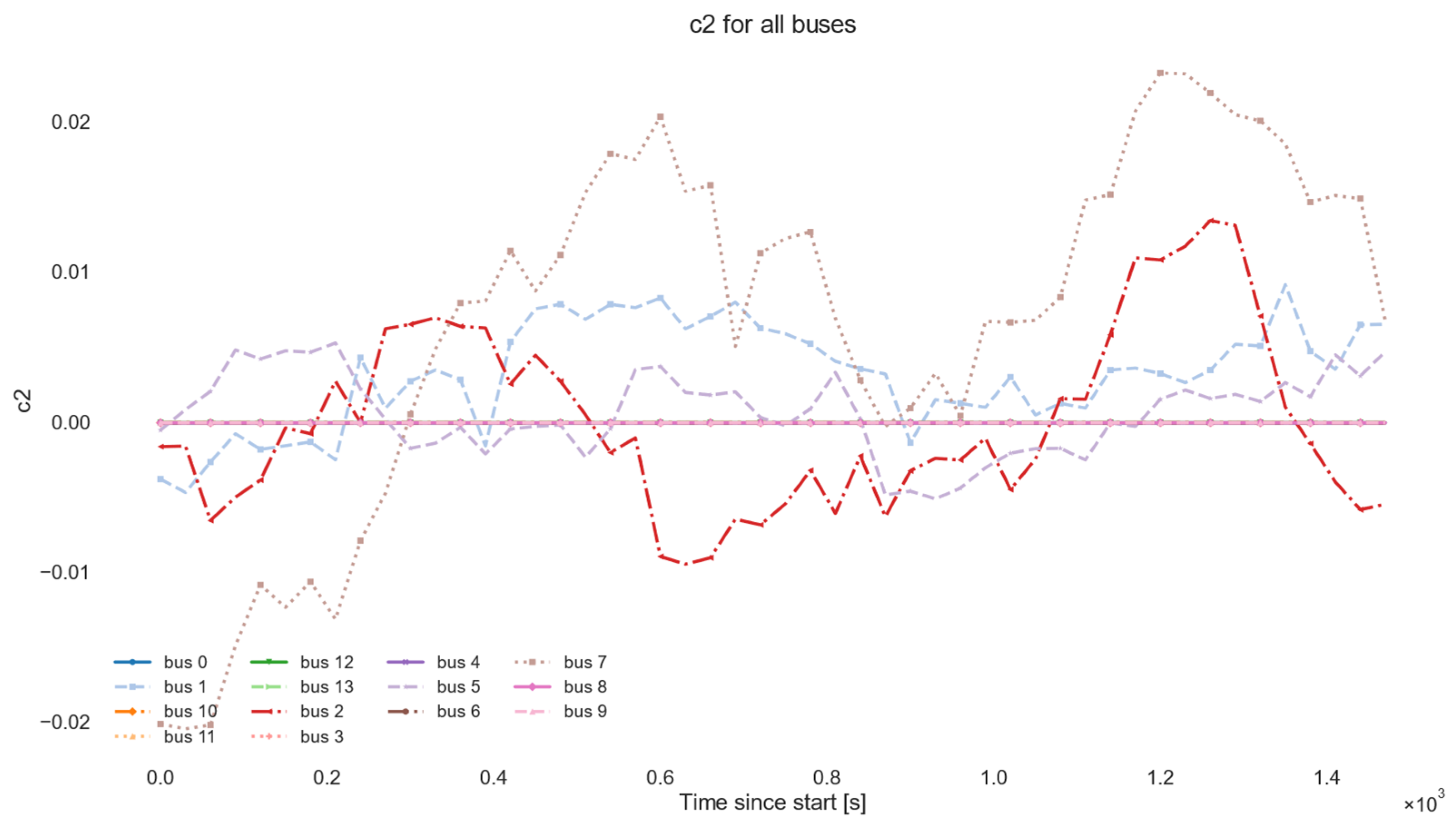

- multi-scale , structural functions .

- Classical Li,t averaged in the window.

4.1.3. Standardization

4.1.4. Composite Score (CFI/FVSI_Fr)

4.1.5. Change Detection/Alarms

- EWMA: , alarm at ;

- CUSUM (one-sided): , alarm at ;

- persistence: requirement for ≥K consecutive exceedances.

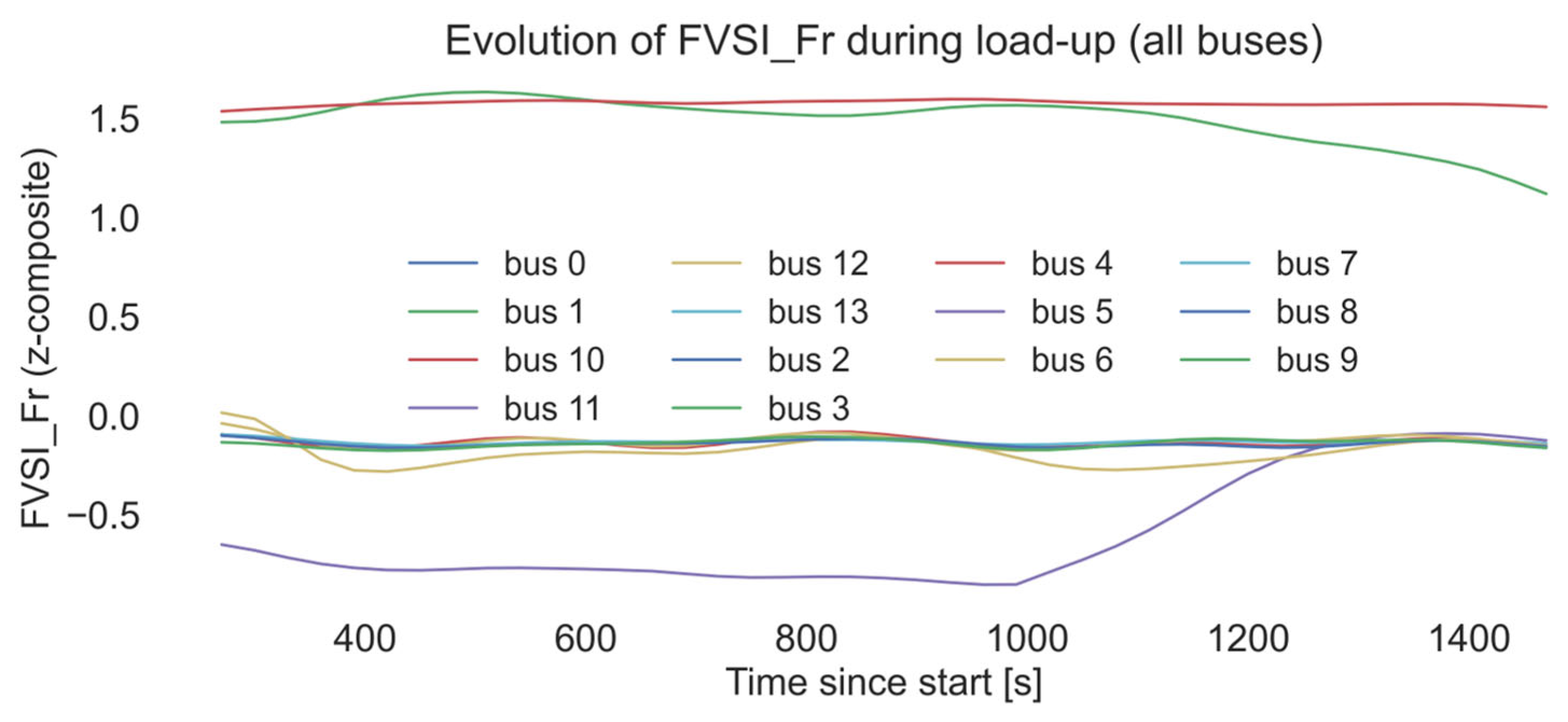

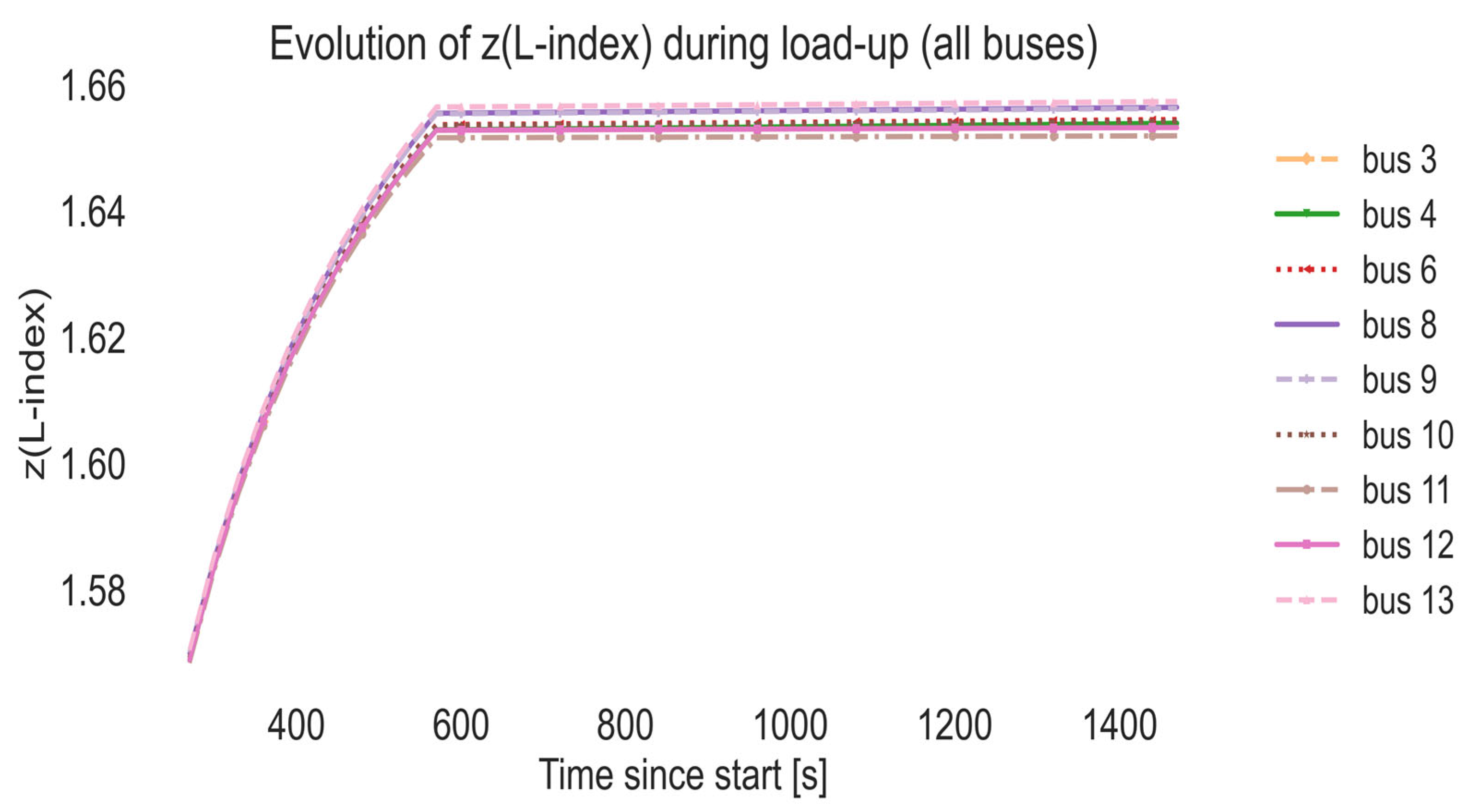

4.1.6. Output and Visualization: Recording of CFIi,t Alarm Flags, Aggregates by Feeder; Heat Maps (Node × Time)

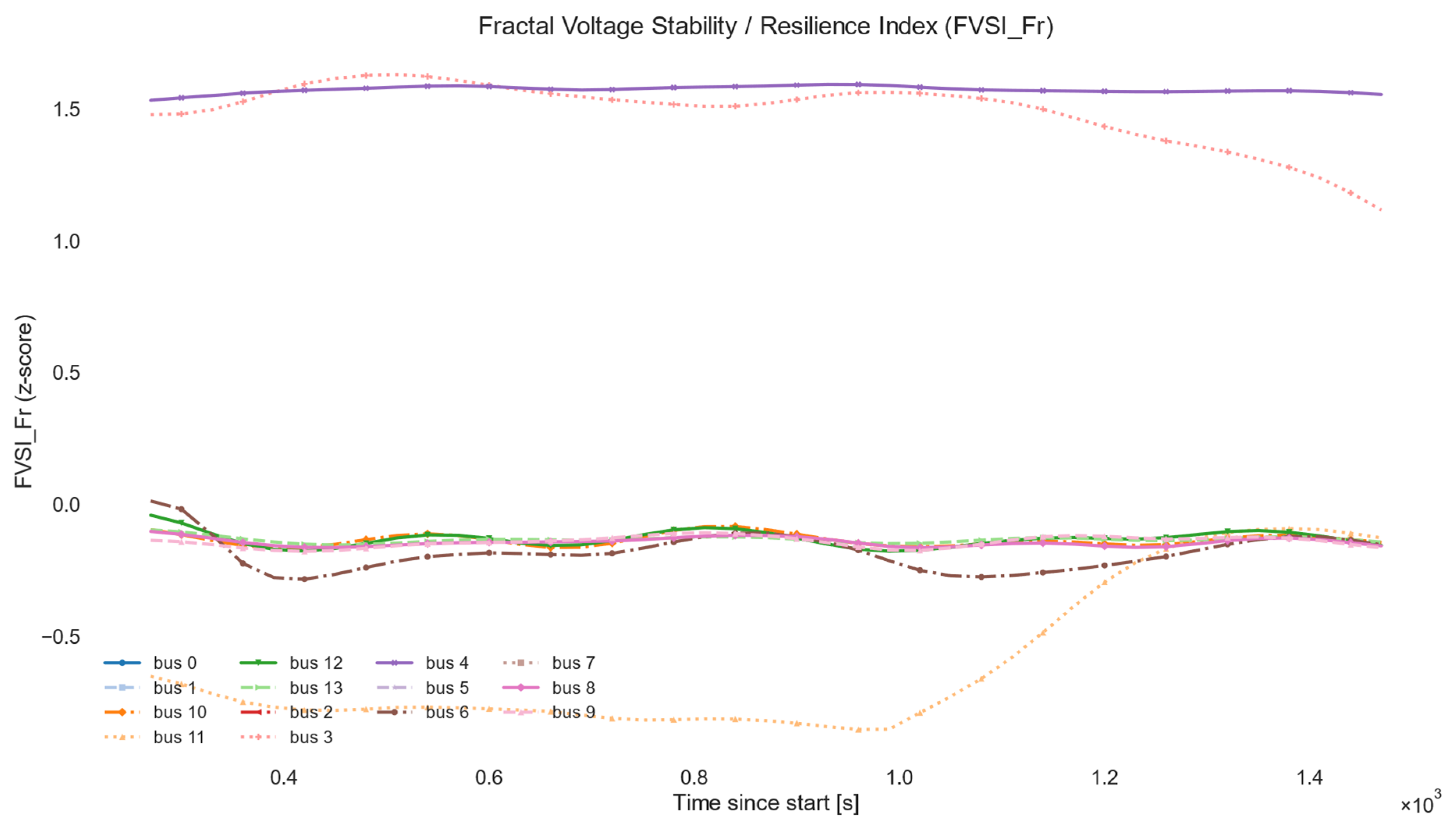

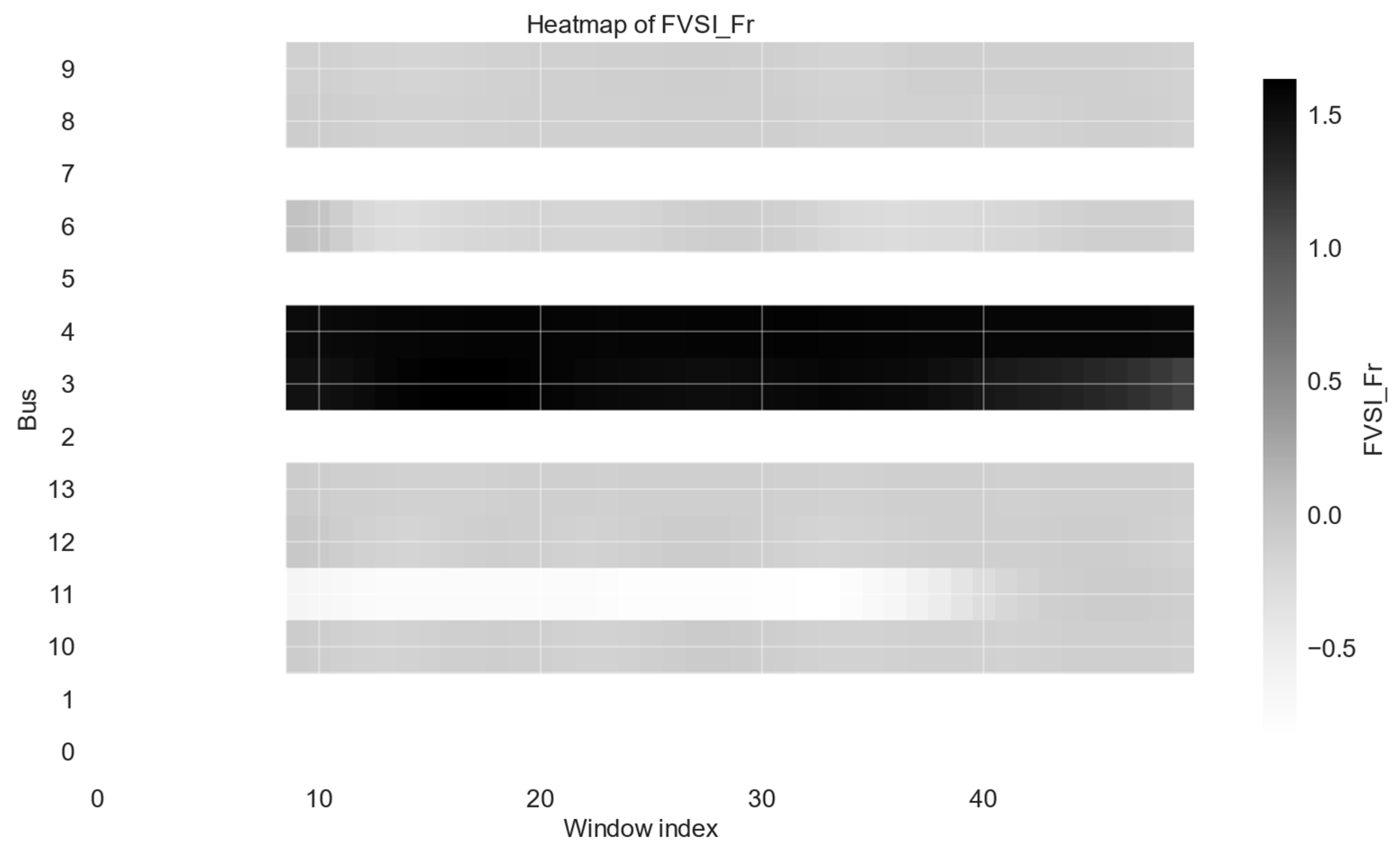

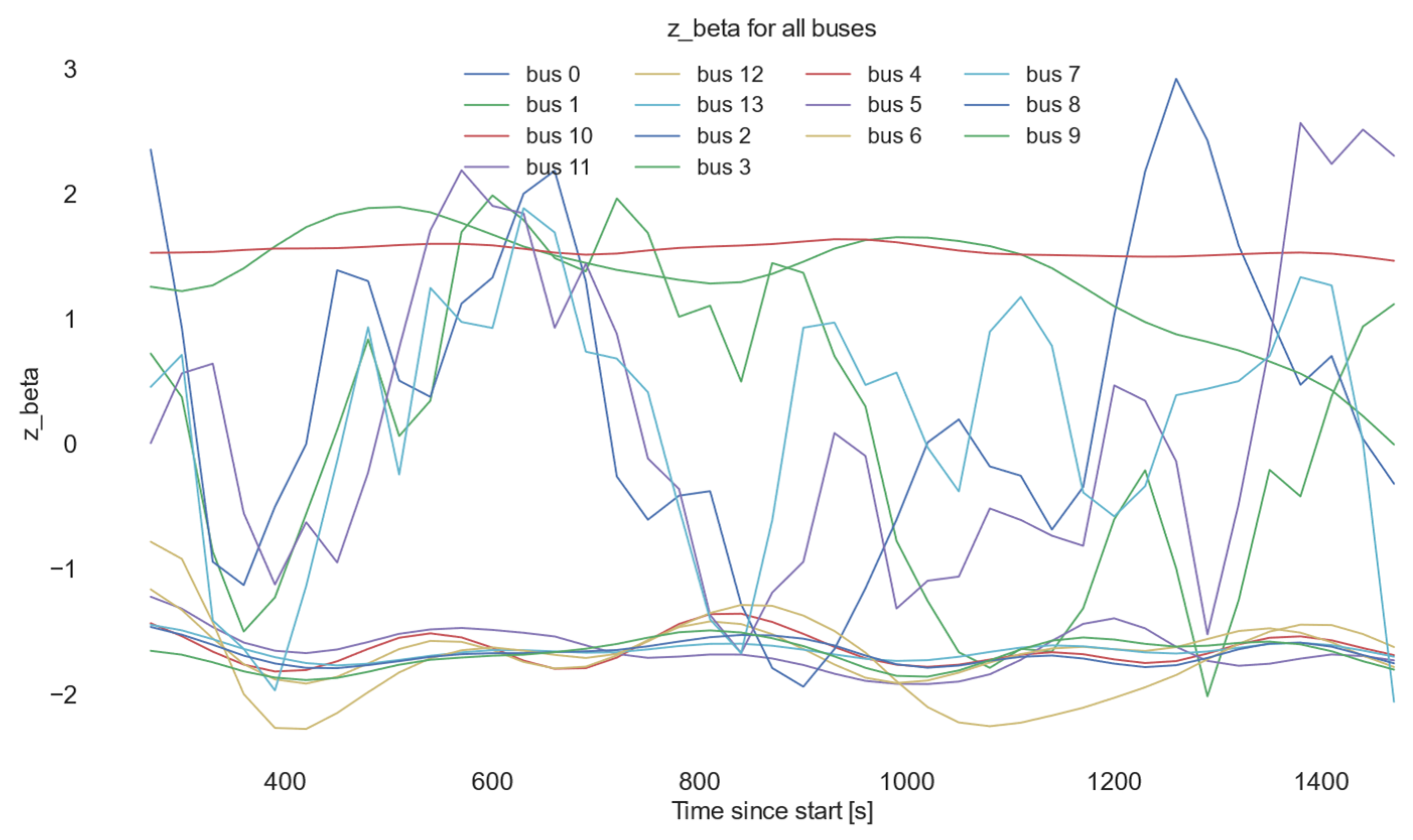

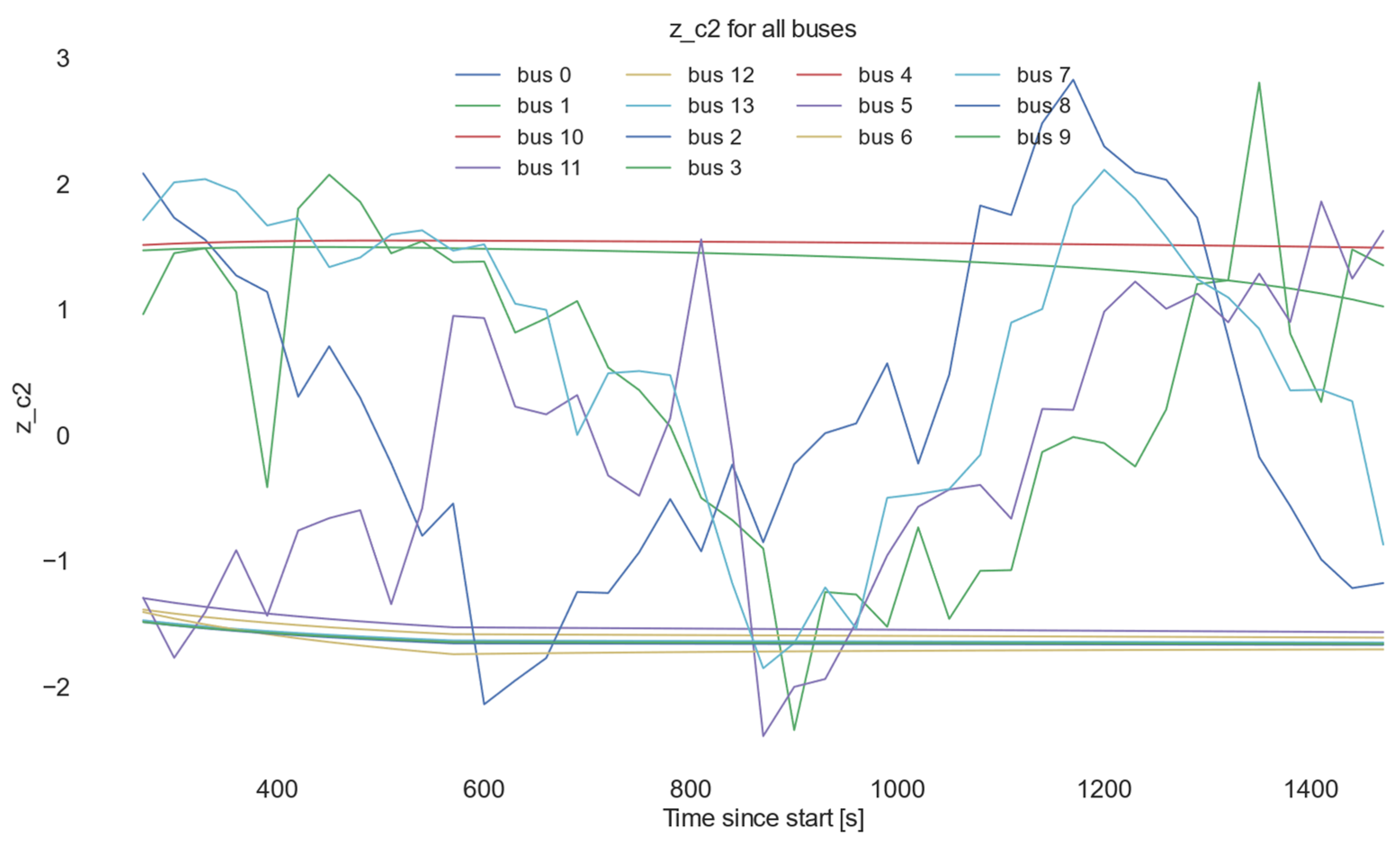

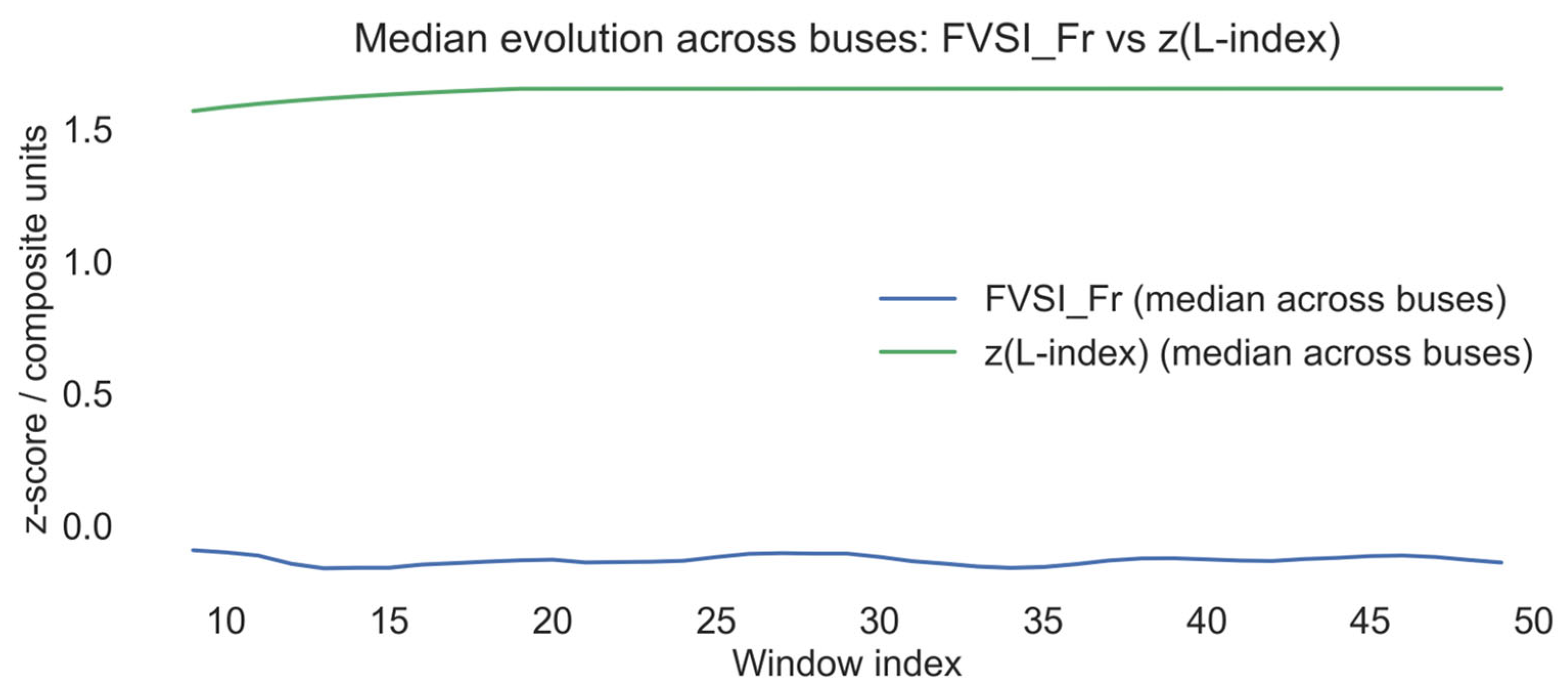

- System level:

- -

- a common plot of FVSI_Fr for all nodes showing temporal alignment of deviations;

- -

- heat maps (node × window) for FVSI_Fr and selected z-features that highlight synchronized degradations and spatial “hot spots”.

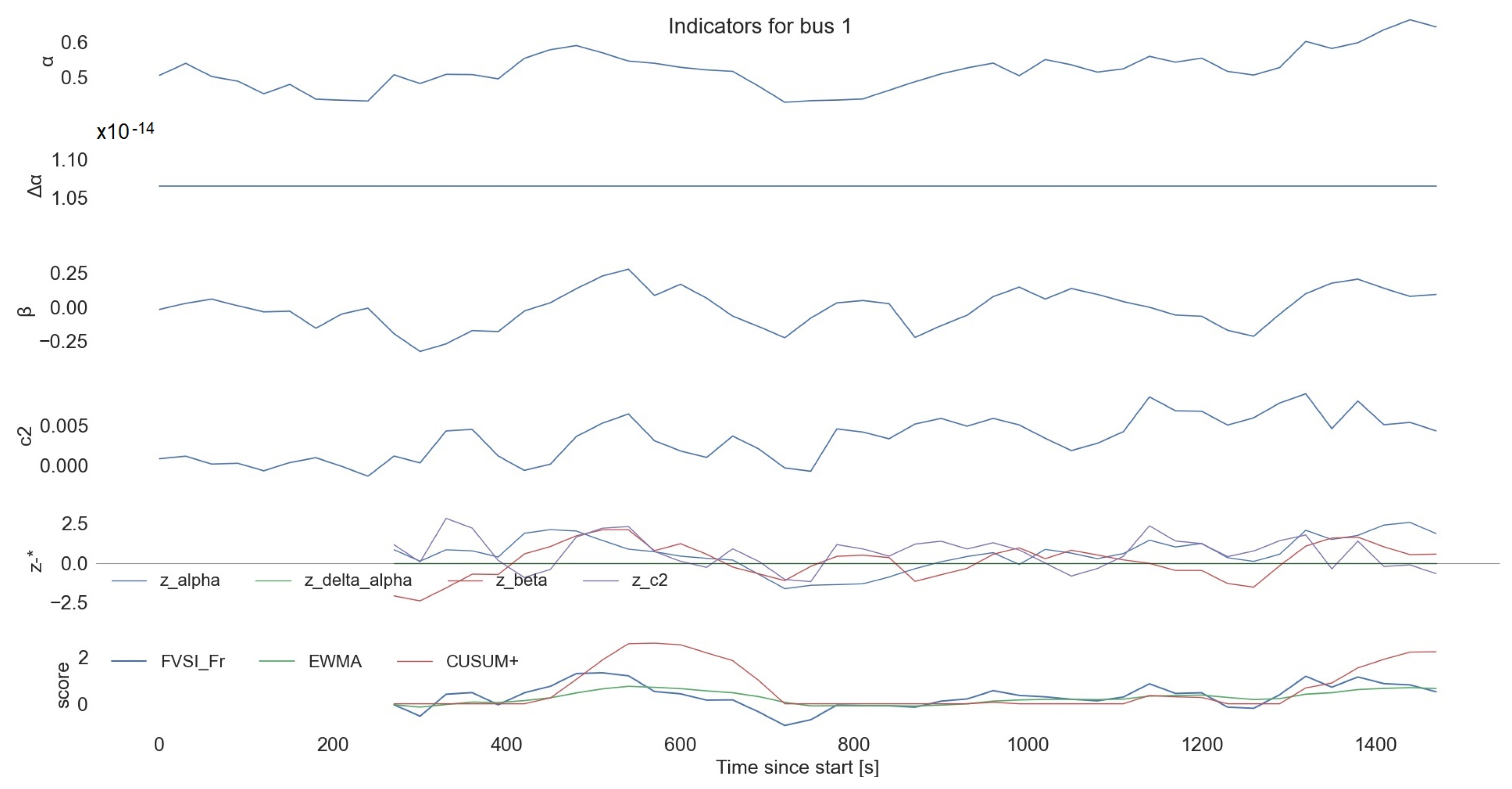

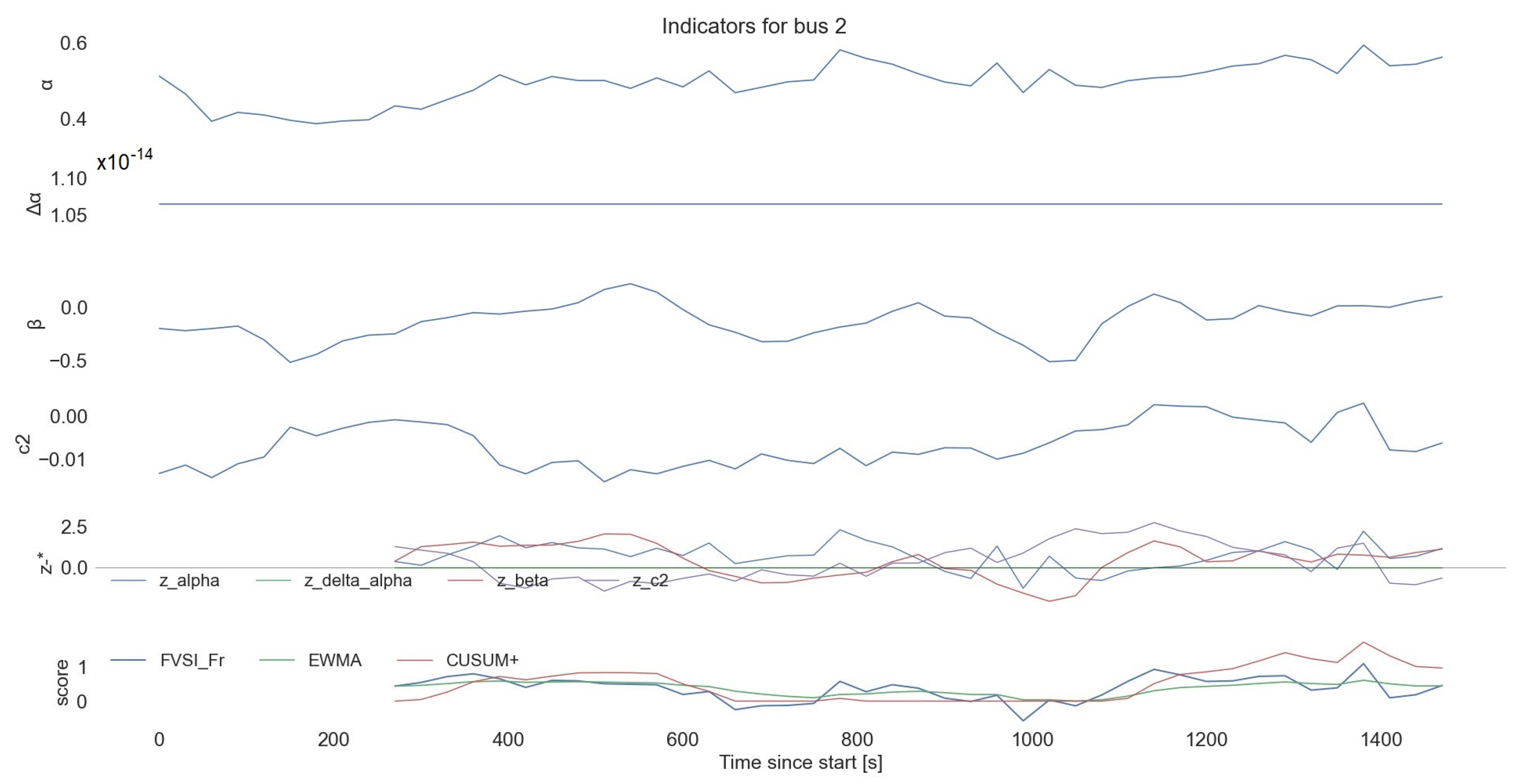

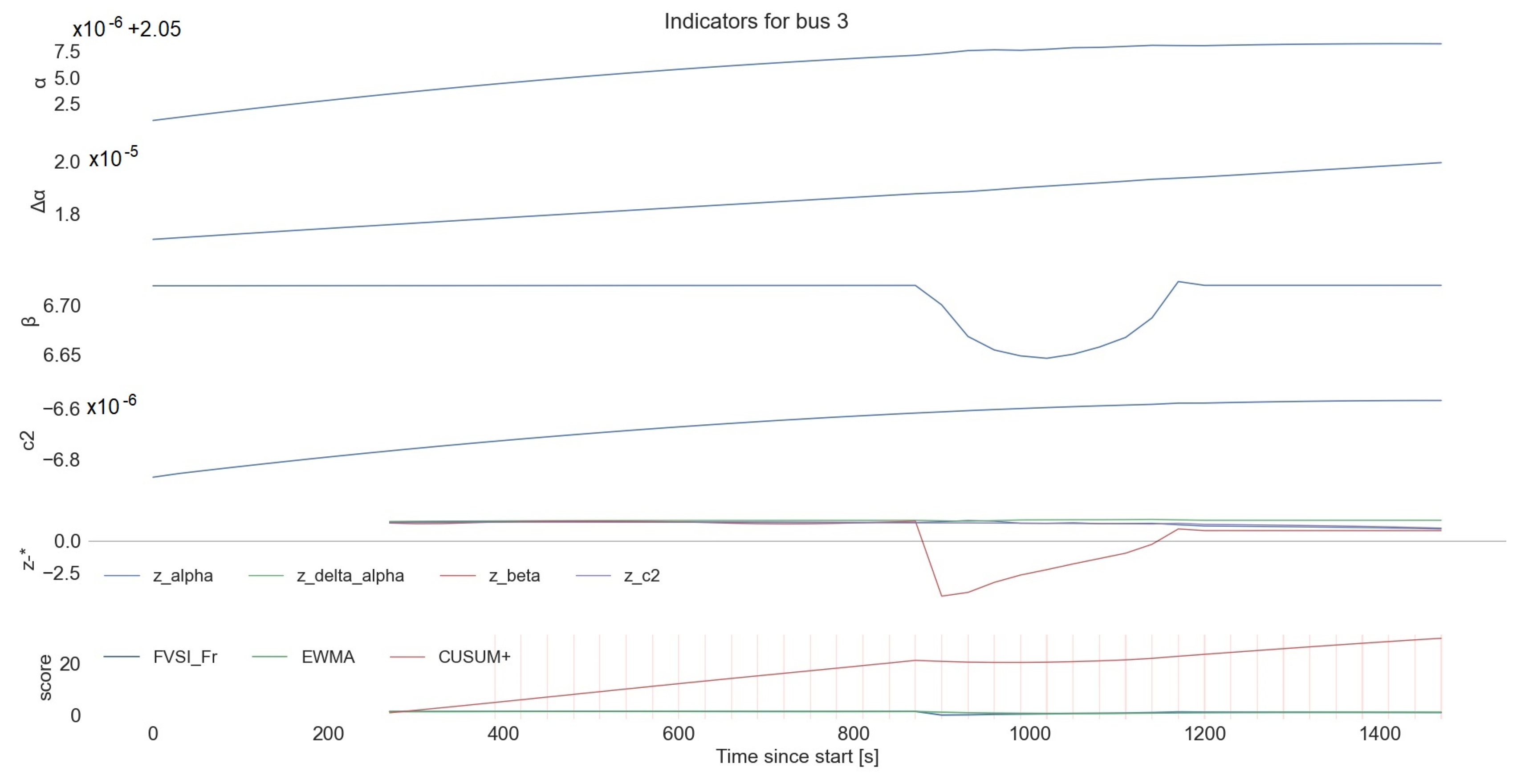

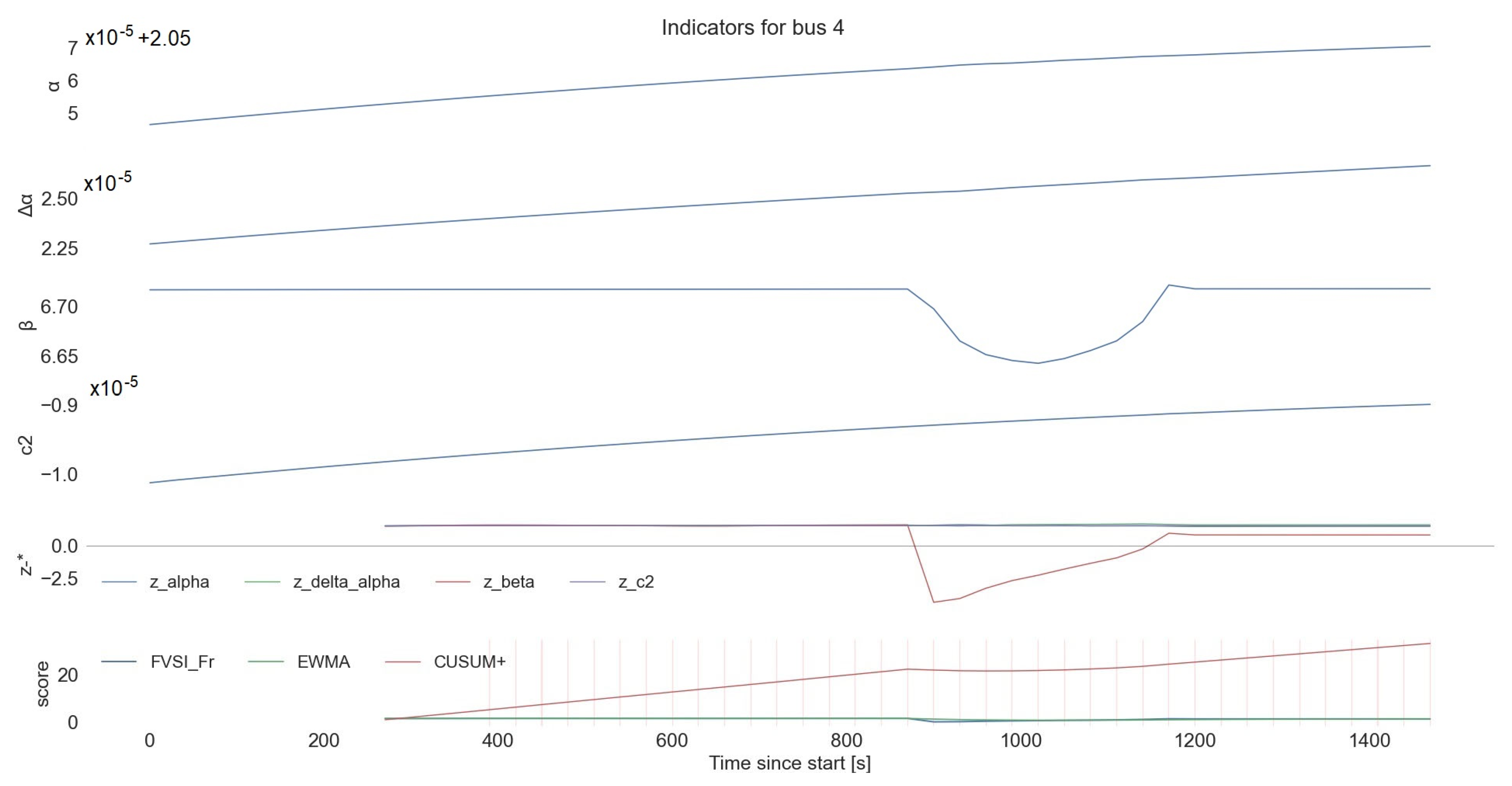

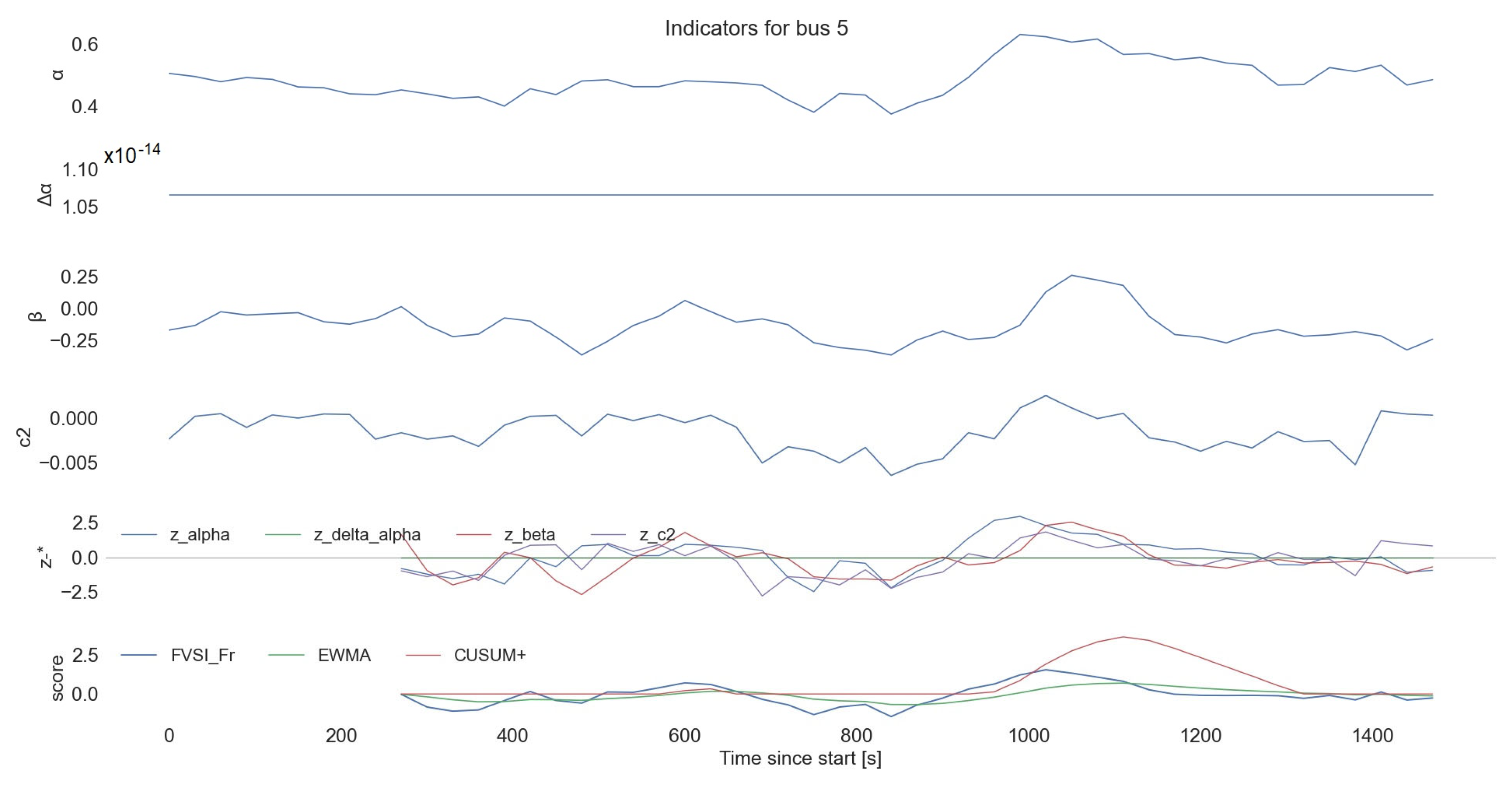

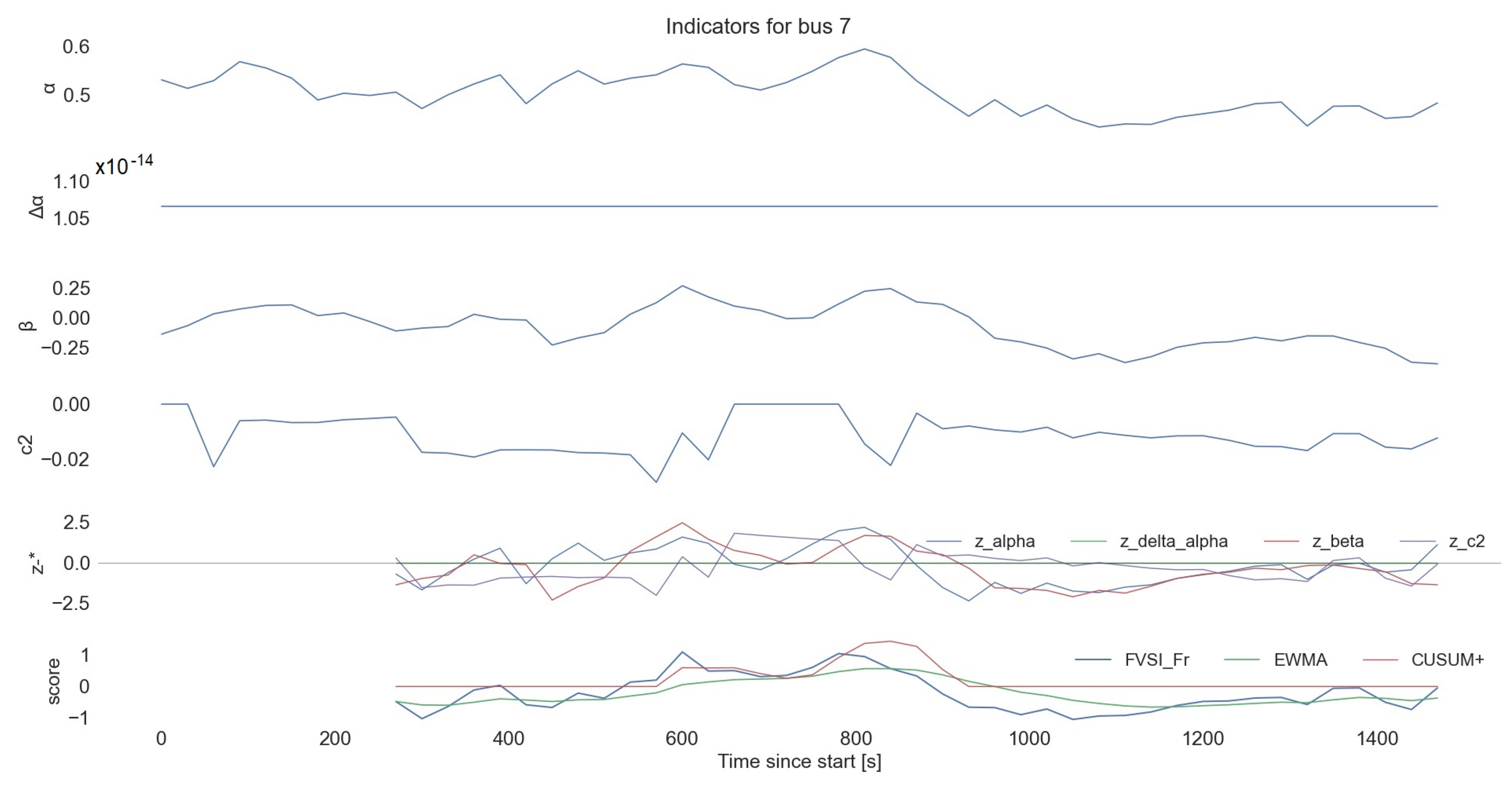

- Node level:

- -

- multi-panel bus plots that stack raw features;

- -

- z-features (denoted by “z-*”, which means rolling z-scores for a bus relative to a local baseline) and FVSI_Fr with EWMA/CUSUM overlays;

- -

- alarm windows are shaded for quick triage.

4.2. Window and Scale Selection

- Length W/step Δ: W = 120 ÷ 600 s (300 s), Δ = 10 ÷ 60 s (30 s). Larger W, lower noise, but higher latency; smaller Δ, denser time axis, but more correlation between windows.

- Scales S for DFA/MFDFA: in seconds s ∈ [smin, smax] with smin ≈ max(0.5, 5/fs), smax = min(30, W/4); log-uniform ≈16 scales, transformed into samples s − [sfs], with filter Ns ≥ 4.

- Moments Q: symmetric discrete set (−3:1:3).

- Frequency band for β: [fmin, fmax] = [0.01, 1] Hz for PMU; adapts to fs.

- Minimum number of samples: Mmin∈ [256, 512] for regression stability.

4.3. Robustness and Missing Data

4.4. Threshold and Calibration

- Rolling z-scaling (online) with window Mz ∈ [15, 30] steps;

- First N windows (or selected “healthy” interval) as base period, classical or robust (median/MAD).Threshold.

- EWMA: selection of λ ∈ [0.1, 0.3] and threshold by percentiles of “healthy” periods (e.g., 99th), with correction for desired false-positive.

- CUSUM: choose a drift k (0.3–0.7 z-units) and a threshold h (4–8) for a desired in-control average length to false alarm (ARL).

- Persistence: require CFI > γ in ≥K consecutive windows (K = 3 ÷ 5) stabilizes alarms.

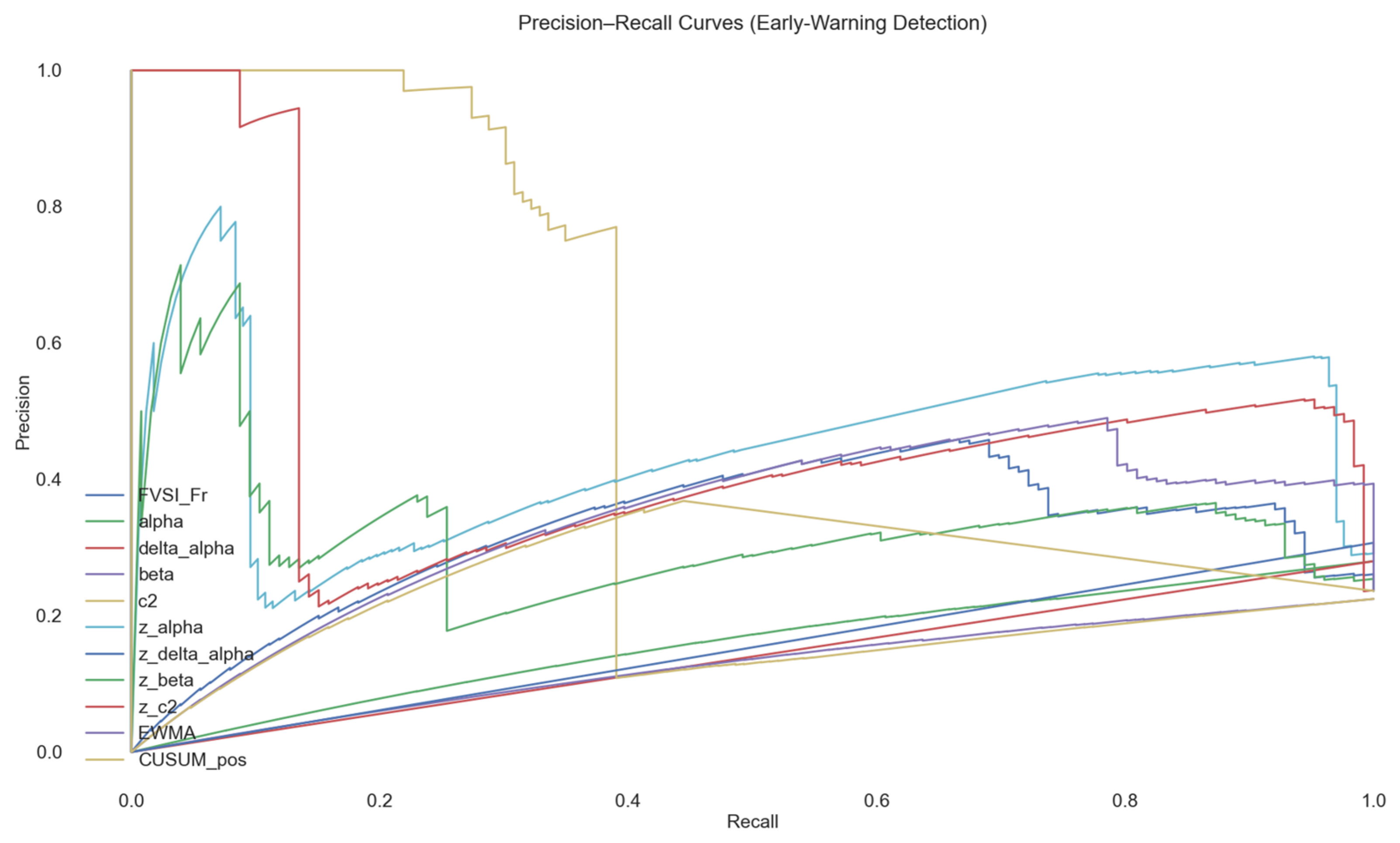

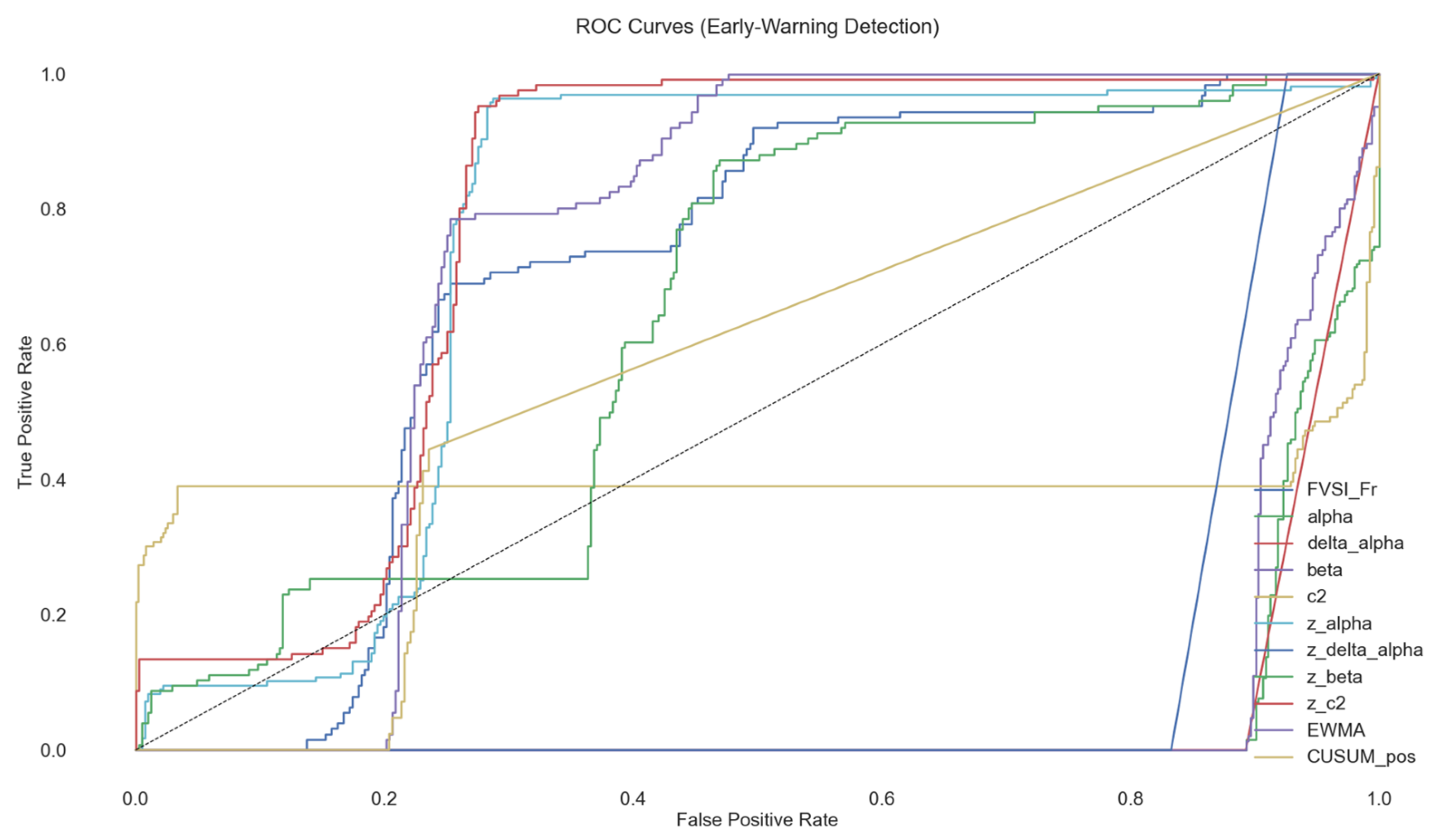

- Cross-validation: given labeled events (disturbances/load surges/constraints on Q), search for (λ, τ, k, h, K) that optimize Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC)/Precision Recall (PR) for early warning (time to incident at fixed False Positive Rate (FPR)).

4.5. Aggregation by Nodes and by Feeder

- Feeder aggregates: or upper quantile (e.g., 90th) for feeder “hotness”.

- Spatial persistence: feeder level alarm at ≥q nodes in alarm (q fixed or function of size/centrality).

- Weights: by load/centrality/historical vulnerability.

4.6. Computational Cost and Parallelization

4.7. Recommended Settings

- W = 300 s, Δ = 30 s, Mmin = 256;

- S: 16 log-scales in [0.5, min(30, W/4)] s, Q = {−3, …, 3};

- [fmin, fmax] = [0.01, 1] Hz;

- z-scaling: rolling with Mz = 20;

- EWMA: λ = 0.2, = 3 z-units;

- CUSUM: k = 0.5, h = 5;

- : 8 rocks in [0.5, 30] s and ≤W/4.

4.8. Interpretation and Reliability

4.9. Output Artifacts and Integration

5. Case Studies: Experimental Design, Objectives, and Evaluation

5.1. Objectives and Hypotheses

5.2. Simulation Studies

5.2.1. Why Simulations

5.2.2. Scenarios and Generative Model

- S1 (load → PV-nose): P ↦ κP, Q ↦ κQ with step Δκ, until miniVi < 0.9 p.u. or CPF reaches the nose.

- S2 (Q-constraints): fixed load near the limit; stepwise saturation of the Q-capabilities of Inverter-Based Resource (IBR)/compensation.

5.2.3. Definition of “Truth”

5.2.4. Evaluation Protocol

5.3. Field Data from RES-Dominated Feeders

5.3.1. Motivation

5.3.2. Data and Labels

5.3.3. Protocol and Evaluation

5.4. Baselines and Ablations

- Univariate early signals: DFA α, MFDFA Δα, spectral β, variance/autocorrelation.

- Classical indicator: local L-index (if available).

- CFI ablations: no ; weight variations w; different bands for β.

5.5. Statistical Methodology

5.6. Sensitivity and Robustness

- Windows (W,Δ) ∈ {(180, 10), (300, 30), (480, 60)};

- Bands for β: [0.02, 0.5] Hz, [0.005, 0.3] Hz;

- Baseline: rolling vs. first N (classical/robust);

- Noise σ and missingness ρ in [0.10%];

- Persistence K ∈ {2, 3, 5}; EWMA/CUSUM parameters (λ, τ, k, h).

5.7. Operational Perspective

- Timeliness: how early does the CFI alert to a critical situation (minute scale);

- Reliability: what is the false alarm rate at target thresholds (e.g., ≤1–3/day/feeder);

- Localization: to what extent is high CFI concentrated in vulnerable sub-areas (supporting V/Q interventions).

5.8. Limitations and Validity

6. Results

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| ARL | Average Run Length |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| CFI | Composite fractal index |

| CPF | Continuation Power Flow |

| CUSUM | Cumulative SUM |

| DER | Distributed Energy Resource |

| DFA | Detrended Fluctuation Analysis |

| EWMA | Exponentially Weighted Moving Average |

| FPR | False Positive Rate |

| FVSI | Fast Voltage Stability Index |

| IBR | Inverter-Based Resource |

| LT | Lead Time |

| MFDFA | Multifractal Detrended Fluctuation Analysis |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| OLTC | On-Load Tap Changer |

| PMU | Phasor Measurement Unit |

| PR | Precision Recall |

| PSD | Power Spectral Density |

| RES | Renewable energy sources |

| RMU | Ring Main Unit |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SCADA | Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition |

| STATCOM | Static Synchronous Compensator |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TPR | True Positive Rate |

| VSA | Voltage Stability Assessment |

References

- Peng, C.; Buldyrev, S.V.; Havlin, S.; Simons, M.; Stanley, H.E.; Goldberger, A.L. Mosaic organization of DNA nucleotides. Phys. Rev. E 1994, 49, 1685–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Havlin, S.; Stanley, H.E.; Goldberger, A.L. Quantification of scaling exponents and crossover phenomena in nonstationary heartbeat time series. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 1995, 5, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantelhardt, J.W.; Zschiegner, S.A.; Koscielny-Bunde, E.; Havlin, S.; Bunde, A.; Stanley, H. Multifractal detrended fluctuation analysis of nonstationary time series. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2002, 316, 87–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, H.; Abry, P.; Jaffard, S. Bootstrap for Empirical Multifractal analysis. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2007, 24, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lade, S.J.; Gross, T. Early warning signals for critical transitions: A Generalized modeling approach. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012, 8, e1002360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dakos, V.; Carpenter, S.R.; Brock, W.A.; Ellison, A.M.; Guttal, V.; Ives, A.R.; Kéfi, S.; Livina, V.; Seekell, D.A.; Van Nes, E.H.; et al. Methods for detecting early warnings of critical transitions in time series illustrated using simulated ecological data. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundur, P. Power System Stability and Control. 1994. Available online: https://www.accessengineeringlibrary.com/content/book/9781260473544 (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Ajjarapu, V.; Christy, C. The Continuation Power Flow: A tool for steady state voltage stability analysis. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 1992, 7, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, I.; Terziev, A. Environmental Impact and Risk Analysis of the Implementation of Cogeneration Power Plants through Biomass Processing. In Innovative Renewable Waste Conversion Technologies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutsem, T.; Vournas, C. Voltage Stability of Electric Power Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, V.M.; De Brito, H.R.; Uhlen, K.O. Comparative analysis of online voltage stability indices based on synchronized PMU measurements. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2024, 40, 101544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, T.a.V.; Haneesh, K.M. Voltage stability analysis using L-Index under various transformer Tap Changer settings. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Circuit, Power and Computing Technologies (ICCPCT), Nagercoil, India, 18–19 March 2016; Volume 18, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahab, S.; Sankaran, A. Multifractal Applications in Hydro-Climatology: A Comprehensive Review of Modern Methods. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guariglia, E.; Guido, R.C.; Dalalana, G.J.P. From Wavelet Analysis to Fractional Calculus: A Review. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre, J.C.; Pavón-Domínguez, P.; Dorronsoro, B.; Galindo, P.L.; Ruiz, P. Multi-Signal Multifractal Detrended Fluctuation Analysis for Uncertain Systems—Application to the Energy Consumption of Software Programs in Microcontrollers. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossie, M.A.; Yetayew, T.T.; Bitew, G.T.; Yenealem, M.G.; Beza, T.M. Machine learning algorithms for voltage stability assessment in electrical distribution systems. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podolsky, D.; Turitsyn, K.; Podolsky, D.; Turitsyn, K. Critical slowing-down as indicator of approach to the loss of stability. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Smart Grid Communications (SmartGridComm), Venice, Italy, 3–6 November 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Sign Retention in Classical MF-DFA. Fractal Fract. 2022, 6, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhu, X.; He, C.; Hu, J.; Fan, J. Critical slowing down theory provides early warning signals for sandstone failure. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 934498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, G.; Qiu, L.; Zhang, B.; Sun, Y.; Gui, Z.; Zhang, Q. A Modified Multifractal Detrended Fluctuation Analysis (MFDFA) Approach for Multifractal Analysis of Precipitation in Dongting Lake Basin, China. Water 2019, 11, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappa, H.; Thakur, T. Voltage instability detection using synchrophasor measurements: A review. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2020, 30, e12343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, G.; Kralov, I.; Koprev, I.; Vasilev, H.; Naydenova, I. Coal Share Reduction Options for Power Generation during the Energy Transition: A Bulgarian Perspective. Energies 2024, 17, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhong, C.; Yue, K.; Zheng, Y.; Jiang, W.; Wang, J. Modified MF-DFA Model Based on LSSVM Fitting. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorska, I.; Puchalski, A. Rotating Machinery Diagnosing in Non-Stationary Conditions with Empirical Mode Decomposition-Based Wavelet Leaders Multifractal Spectra. Sensors 2021, 21, 7677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, P.G.; Anvari, M.; Kantz, H. Identifying characteristic time scales in power grid frequency fluctuations with DFA. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2020, 30, 013130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalalfeh, L.; Bogdan, P.; Jonckheere, E. Evidence of long-range dependence in power grid. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), Boston, MA, USA, 17–21 July 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluszczyński, R.; Drożdż, S.; Kwapień, J.; Stanisz, T.; Wątorek, M. Disentangling Sources of Multifractality in Time Series. Mathematics 2025, 13, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanjani, M.G.M.; Mazlumi, K.; Kamwa, I. Combined analysis of distribution-level PMU data with transmission-level PMU for early detection of long-term voltage instability. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2019, 13, 3634–3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Cho, H.; Park, B.; Nam, S.; Hur, K.; Lee, B. Enhancement of linearity and constancy of PMU-based voltage stability index: Application to a Korean wide-area monitoring system. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2020, 14, 3357–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilakarathne, C.; Meegahapola, L.; Fernando, N. Real-time voltage stability assessment using phasor measurement units: Influence of synchrophasor estimation algorithms. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 119, 105933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boričić, A.; Torres, J.L.R.; Popov, M. Comprehensive Review of Short-Term Voltage Stability Evaluation Methods in Modern Power Systems. Energies 2021, 14, 4076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, H.S.; Vokony, I. Voltage stability indices—A comparison and a review. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2022, 98, 107743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baleboina, G.M.; Mageshvaran, R. A survey on voltage stability indices for power system transmission and distribution systems. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1159410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, Z.; Du, Z.; Zhong, G.; Gao, J.; Zhen, H. Transient voltage stability assessment and margin calculation based on disturbance signal energy feature learning. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1479478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndour, M.; Padberg-Gehle, K.; Rasmussen, M. Spectral Early-Warning Signals for Sudden Changes in Time-Dependent Flow Patterns. Fluids 2021, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morr, A.; Boers, N. Detection of approaching critical transitions in natural systems driven by red noise. Phys. Rev. X 2024, 14, 021037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proverbio, D.; Skupin, A.; Gonçalves, J. Systematic analysis and optimization of early warning signals for critical transitions using distribution data. iScience 2023, 26, 107156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sklab, L.; Retière, N. Multifractal analysis of French medium voltage distribution networks. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2024, 38, 101372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, K.; Patil, A.; Satyapal, K.S.; Diggikar, S.; Mohan, N. Synchrophasor driven voltage stability assessment using adaptive deep learning based tools on temporal ensembling and data augmentation. Int. J. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2024, 11, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Parameter | Symbol/Field | Default Value | CLI Flag | Justification/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time windows | Window length | Tω | 300 s | win_sec | Accuracy–latency tradeoff; gives ≥10–15 cycles at 0.05–0.1 Hz fluctuations. |

| Window step | ΔT | 30 s | step_sec | 10× overlap for smooth tracking and early warning. | |

| Sampling | Discretization estimate | fs | median of Δt | built-in | Robust estimate from timestamps; requires monotonic ts. |

| DFA/MFDFA | Scale range | S | 0.5–30 s (log–diff, 16 levels) | built-in | Covers subsecond to tens of seconds dynamics. |

| Detrending polynomial | m | 1 (linear) | built-in | Standard for energy series; avoids overfitting. | |

| MFDFA moments | Q | 13 levels in [−3, 3] | built-in | Balance between stability and spectral resolution. | |

| Spectral analysis | Frequency band | [fmin, fmax] | 0.01–1.0 Hz | fmin, fmax | Covers most driving/loading oscillations. |

| PSD estimator | - | Welch; fallback: periodogram | automatic | Noise-resistant; fallback for non-SciPy environments. | |

| Structure functions | c2 scales | smin, smax, Ns | 0.5–30 s, Ns = 8 | c2_smin, c2_smax, c2_nscales | Multiscale without external wavelets. |

| Preprocessing | Hampel filter | window/σ | 21; 3.0σ | hampel, hampel_win, hampel_nsigma | Suppresses outliers/spikes from measurements. |

| Standardization | z-score window | - | 20 windows | zwin | Local baseline for adaptation to slow trends. |

| Composite | Weights | ωα, ωΔα, ωβ, ωc2 | 0.28/0.28/0.24/0.20 | built-in | Balances sensitivities; sum = 1. |

| Hybrid | L-index blending | λ | 0.25 | built-in | By default we use 0.75CFI + 0.25·(zL), if (L) is available. |

| Alarms | EWMA coeff. | αEWMA | 0.2 | ewma_alpha | Smooth filter for persistent changes. |

| EWMA threshold | - | 3.0 z | ewma_thr | “3σ” rule for rare events. | |

| CUSUM drift/barrier | k, h | 0.5; 5.0 | cusum_k, cusum_h | One-sided positive collapse detection. | |

| Minimum data | Minimum samples in window | - | 256 | min_samples | Reliable estimates for DFA/PSD. |

| Time axis | Time format | - | seconds since start | ts_mode | Interbus friendlycomparison and visualization. |

| Element | Busbar | Rating/Limits | Mode/Control | Role in Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLTC (Substation) | 650 | ΔU step ≈ 1.25%, range ± 10% | AVR by U | Primary Voltage Regulation |

| PV1 | 634 | Pmax = 0.6 MW; ±Qlim = 0.3 Mvar | cosφ ≈ 1; Q(V) limits | RES node; local sensitivity |

| PV2 | 675 | Pmax = 0.4 MW; ±Q_lim = 0.2 Mvar | cosφ ≈ 1; Q(V) limits | RES at “weak” end of feeder |

| Shunt capacitor | 611 | Q_rated = 0.3 Mvar | fixed | Local Q-support |

| STATCOM | 675 | ±0.5 Mvar | U-control | Fast Q-regulation in case of disturbances |

| PMU/SCADA points | 632, 634, 671, 675, 680 | quantities: V, (Q if available) | logging @ cadence 1 s | Time series source |

| “Critical” buses | 675, 680 | - | - | End of feeder/limited Q-support |

| Parameter | Value (Default) | Justification/Role |

|---|---|---|

| Total duration (sym.) | 1800 s | 30 min, enough windows |

| Logging cadenc | 1 s | PSD to 1 Hz, stable sampling |

| Window (win_sec) | 300 s | ~5 min for DFA/MFDFA/PSD |

| Step (step_sec) | 30 s | 10× overlap, smoother trajectories |

| Frequency band (PSD) | 0.01–1.0 Hz | low-frequency fluctuations of U |

| Z-score window (zwin) | 20 windows | local baseline |

| c2 scales | 0.5–30 s; N = 8 | multiscale for intermittency |

| Min. samples/window | 256 | reliable scale fitting |

| EWMA | α = 0.2; threshold = 3.0 z | smoothing and alarm threshold |

| CUSUM+ | k = 0.5; h = 5.0 | one-sided upward drifts |

| FVSI_Fr weights | α:0.28, Δα:0.28, β:0.24, c2:0.20 | balanced composite index |

| Method | AUC_ROC | AUC_PR |

|---|---|---|

| zα | 0.757801 | 0.472624 |

| zΔα | 0.120393 | 0.306985 |

| zβ | 0.642721 | 0.332238 |

| zc2 | 0.786241 | 0.477187 |

| Δα | 0.053571 | 0.280000 |

| β | 0.068792 | 0.128585 |

| 0.397831 | 0.470573 | |

| EWMA | 0.735599 | 0.340511 |

| FVSI_Fr | 0.695312 | 0.320928 |

| CUSUM | 0.557837 | 0.230300 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Stanchev, P.; Hinov, N. Composite Fractal Index for Assessing Voltage Resilience in RES-Dominated Smart Distribution Networks. Fractal Fract. 2026, 10, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract10010032

Stanchev P, Hinov N. Composite Fractal Index for Assessing Voltage Resilience in RES-Dominated Smart Distribution Networks. Fractal and Fractional. 2026; 10(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract10010032

Chicago/Turabian StyleStanchev, Plamen, and Nikolay Hinov. 2026. "Composite Fractal Index for Assessing Voltage Resilience in RES-Dominated Smart Distribution Networks" Fractal and Fractional 10, no. 1: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract10010032

APA StyleStanchev, P., & Hinov, N. (2026). Composite Fractal Index for Assessing Voltage Resilience in RES-Dominated Smart Distribution Networks. Fractal and Fractional, 10(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract10010032