Your Eyes Under Pressure: Real-Time Estimation of Cognitive Load with Smooth Pursuit Tracking

Abstract

1. Introduction

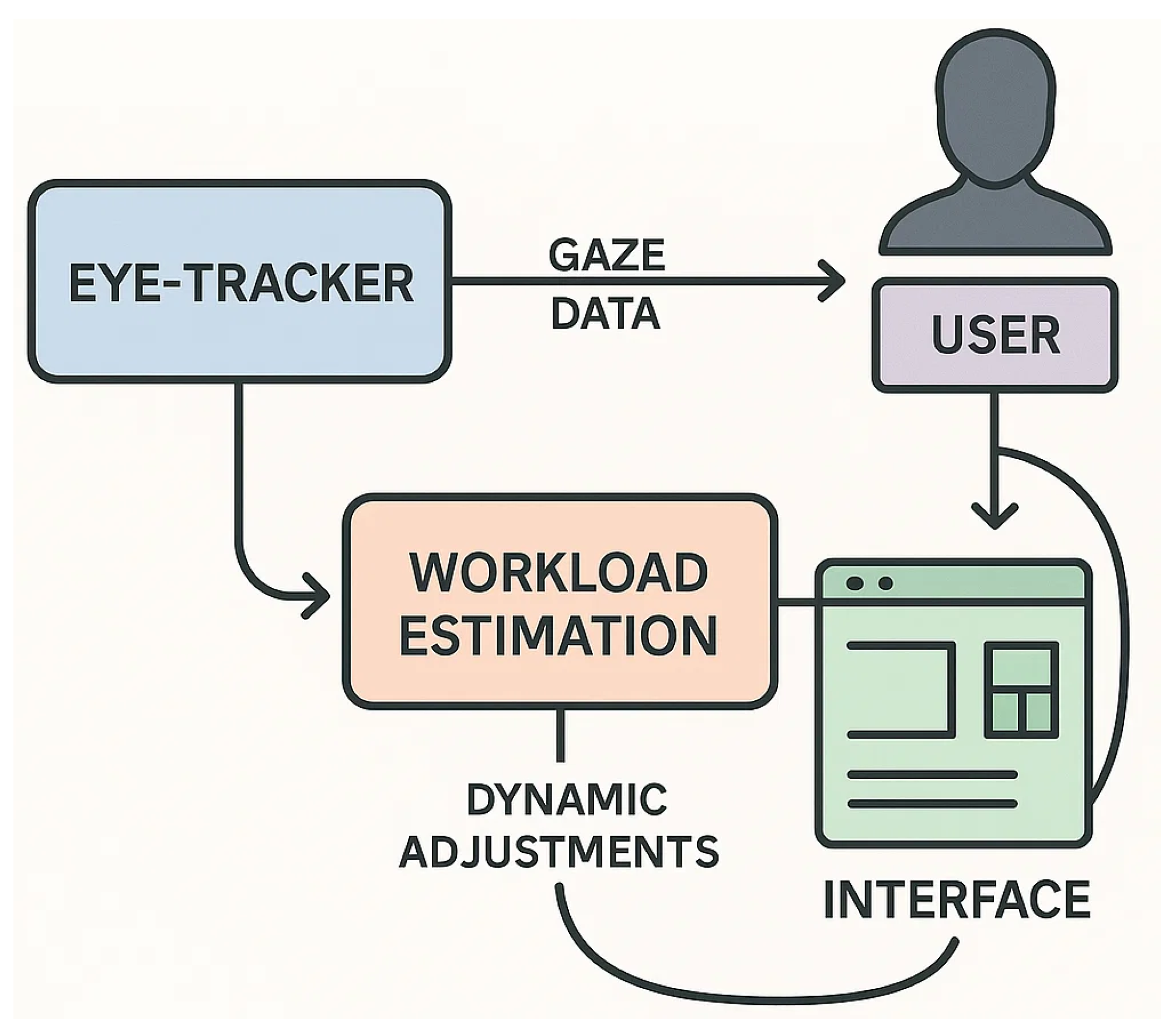

1.1. Adaptive Stress-Aware Systems

1.2. Cognitive Workload Estimation via Eye-Tracking

2. Materials and Method

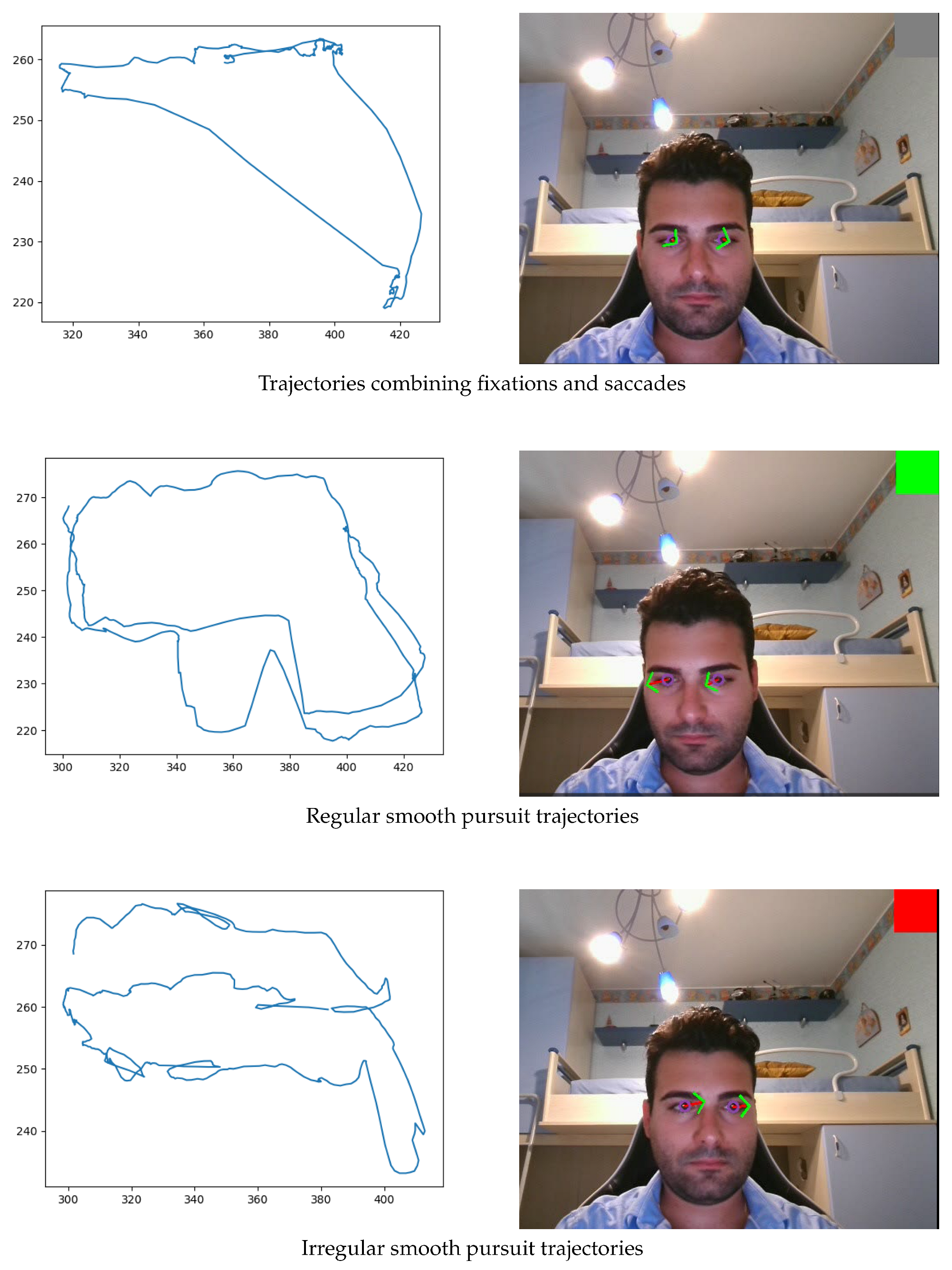

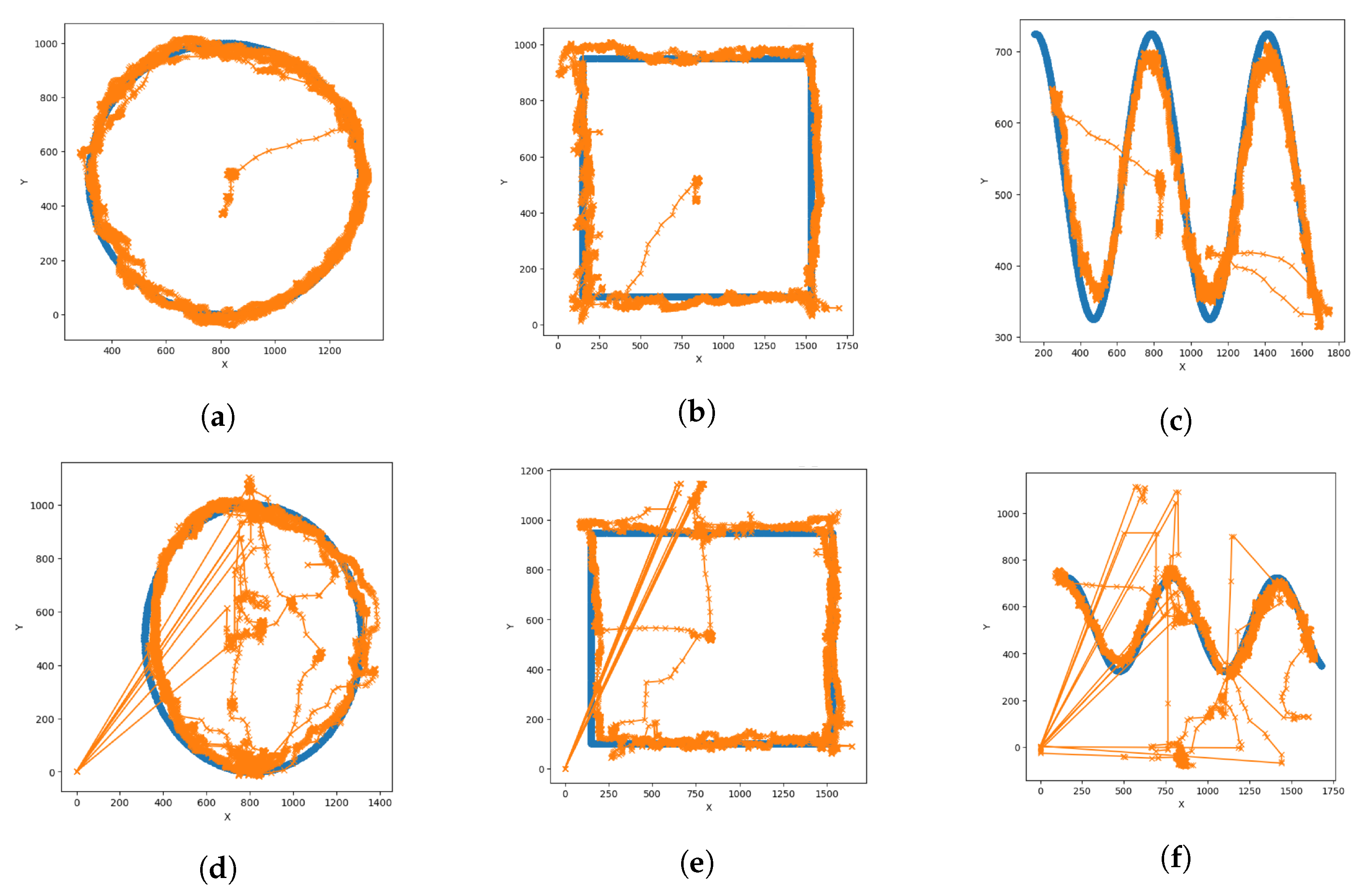

2.1. Kosch-Based Pursuit Deviation Model

- Three candidates were removed: candidate 9 was excluded because some of the corresponding files were found to be corrupted, whereas candidates 11 and 17 were removed following a careful visual inspection of the eye movement data, which revealed improper calibration of the eye-tracking device. It is worth noting that the author reported the exclusion of only two participants, without specifying which ones.

- Min-Max normalization of the x and y coordinates of the target trajectory (with parameter saving and application), followed by the application of the same normalization parameters to the gaze coordinates.

- Feature extraction by computing the Euclidean distance between the normalized coordinates of the moving target and the eye movements:where p and q represent the normalized coordinate vectors of the target and the gaze points, respectively.

- Smoothing of the Euclidean distance signal using a moving average filter with a 250-sample window (equivalent to one second) and a stride of one.

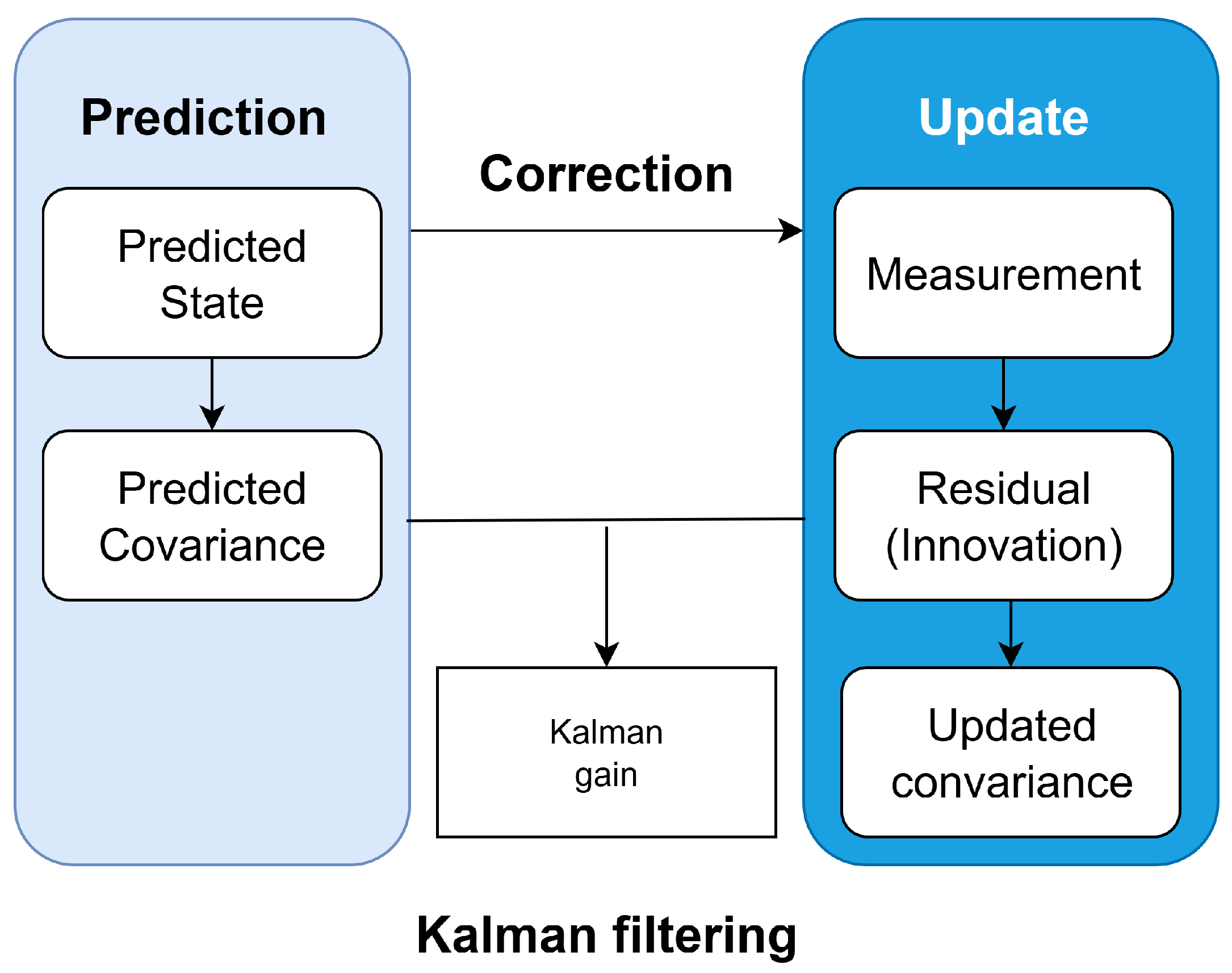

2.2. Kalman-Based Virtual Trajectory Model

2.3. Lightweight B-Spline Approximation

Adaptive Thresholding and Real-Time Application

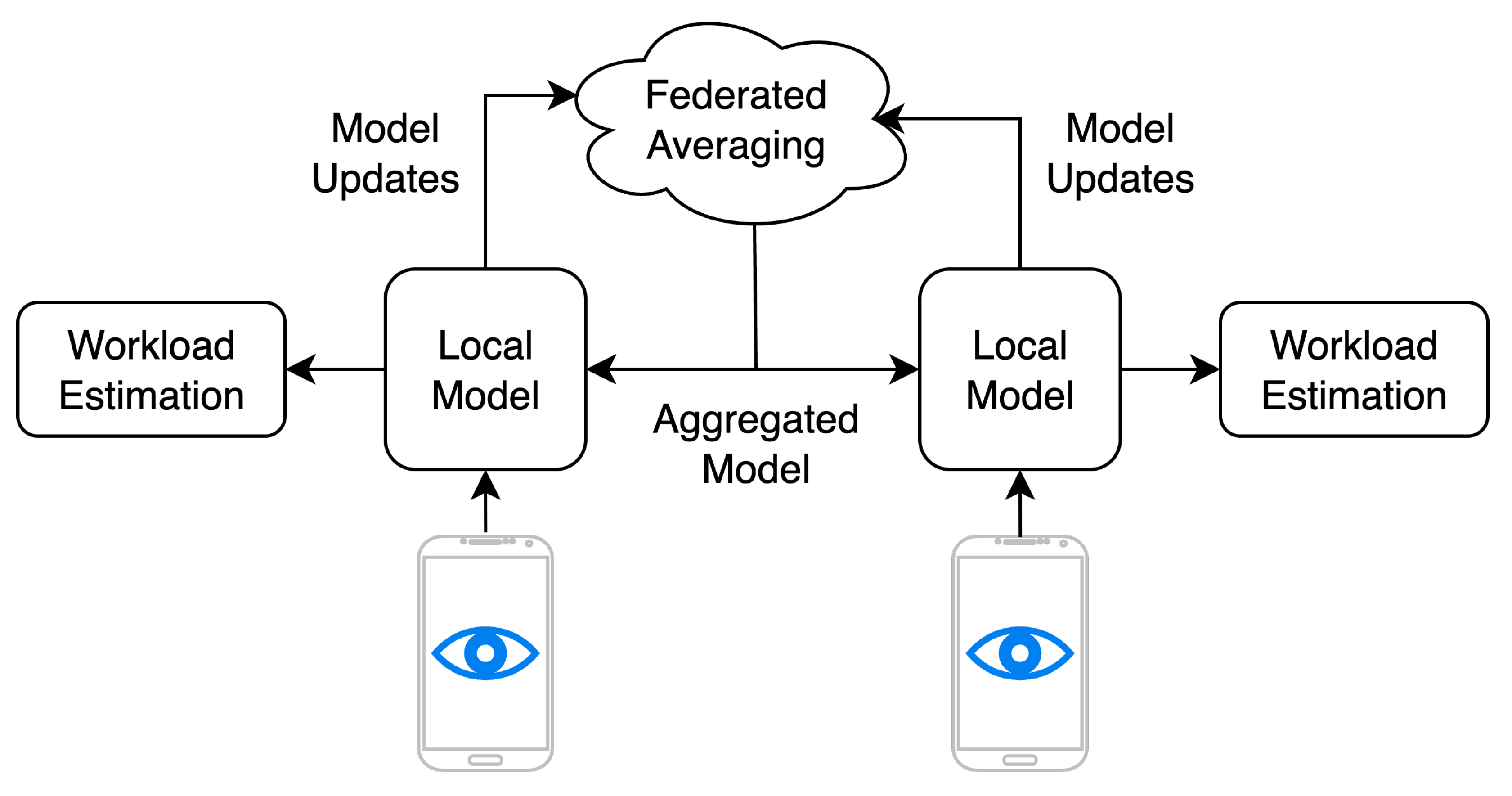

2.4. Federated Learning Extension

3. Results

- Accuracy: measures the overall proportion of correctly classified instances, considering both positive and negative classes.where (True Positives) and (True Negatives) represent correctly predicted samples, while (False Positives) and (False Negatives) correspond to misclassified instances.

- Precision: quantifies the reliability of positive predictions, indicating the fraction of samples classified as positive that are truly positive.A higher Precision implies fewer false alarms in detecting high workload instances.

- Recall (Sensitivity): expresses the model’s ability to correctly identify all positive cases.A higher Recall indicates a better capability to detect true positive samples without missing any.

- F1-score: represents the harmonic mean between Precision and Recall, balancing false positives and false negatives.This metric is particularly informative when there is an uneven class distribution.

- Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC): provides a balanced measure of classification quality, even in the presence of class imbalance, reflecting the correlation between predicted and actual labels.The MCC ranges from (total disagreement) to (perfect prediction), with 0 indicating random classification.

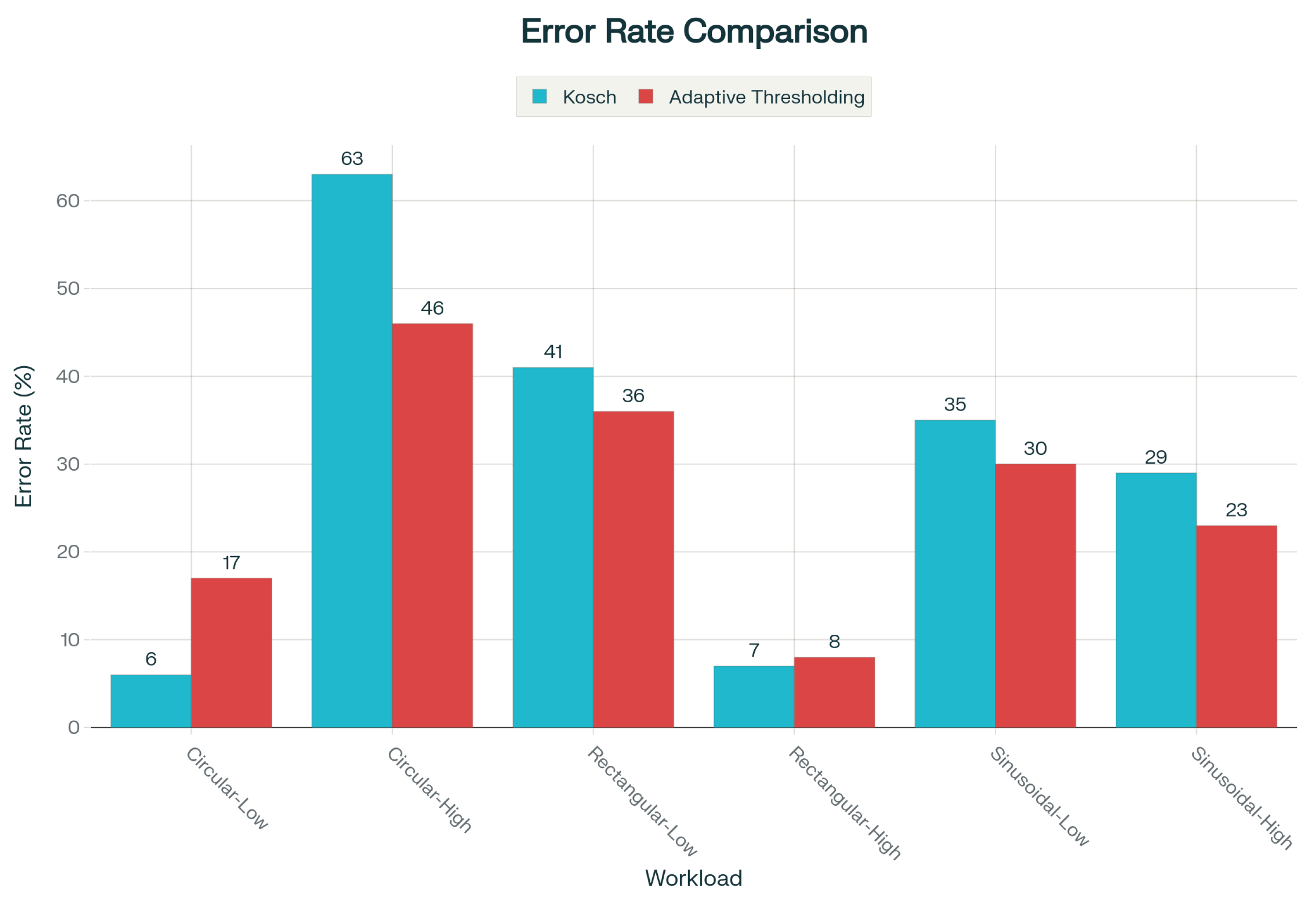

- Circular trajectories: 0.0203

- Sinusoidal trajectories: 0.0252

- Rectangular trajectories: 0.0272

4. Future Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

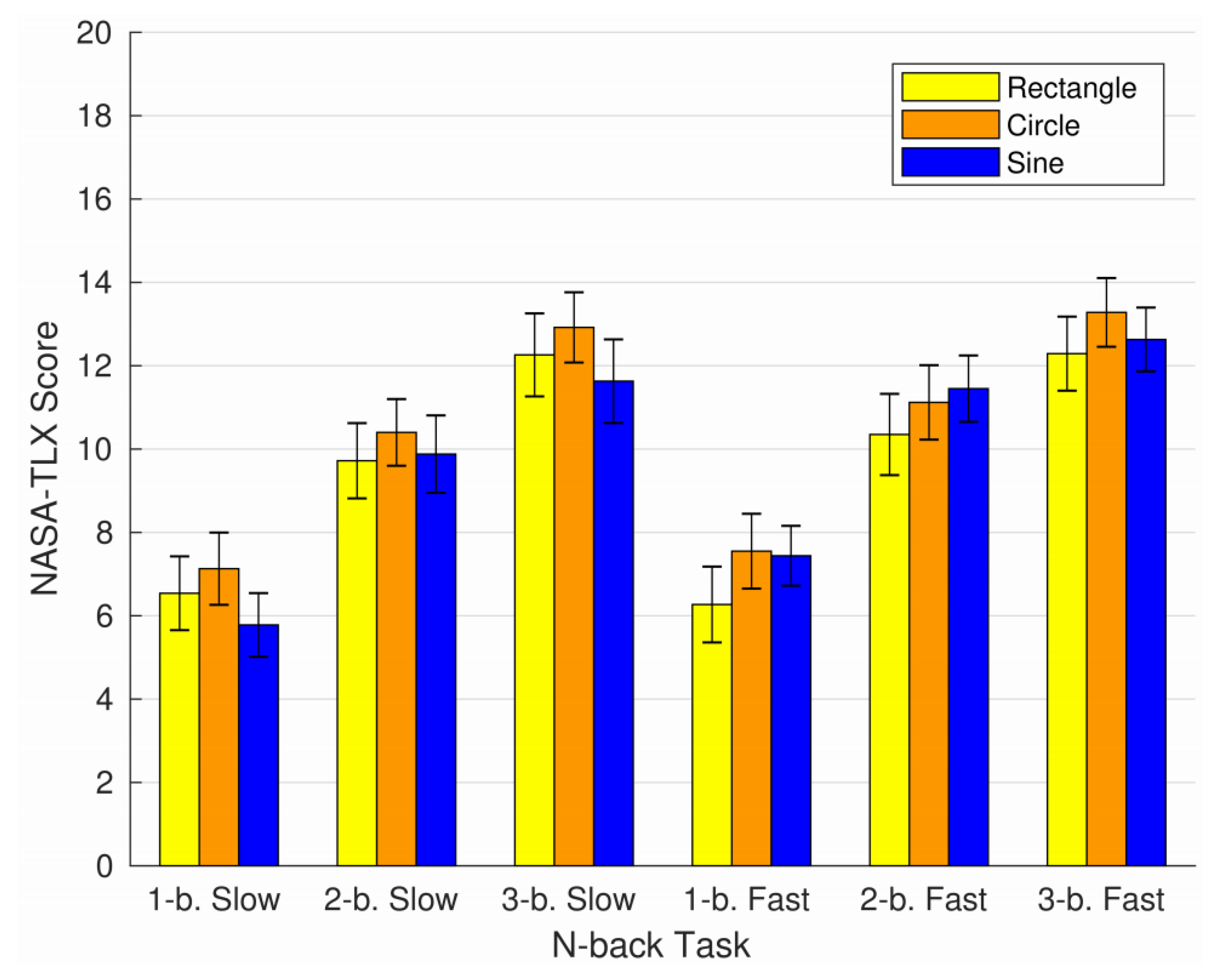

- Hart, S.G.; Staveland, L.E. Development of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): Results of Empirical and Theoretical Research. Adv. Psychol. 1988, 52, 139–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonenko, P.; Paas, F.; Grabner, R.; van Gog, T. Using Electroencephalography to Measure Cognitive Load. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 22, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ider, Ö.; Kusnick, K. Heart rate dynamics for cognitive load estimation in a driving context. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 79728. [Google Scholar]

- Just, M.A.; Carpenter, P.A. Eye fixations and cognitive processes. Cogn. Psychol. 1976, 8, 441–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stasi, L.L.; Catena, A.; Canas, J.J.; Macknik, S.L.; Martinez-Conde, S. Saccadic velocity as an arousal index in naturalistic tasks. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2013, 37, 968–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, J.A.; Walrath, L.C.; Goldstein, R. The endogenous eyeblink. Psychophysiology 1984, 21, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, J. Task-evoked pupillary responses, processing load, and the structure of processing resources. Psychol. Bull. 1982, 91, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korda, Z.; Walcher, S.; Körner, C.; Benedek, M. Effects of internally directed cognition on smooth pursuit eye movements: A systematic examination of perceptual decoupling. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2023, 85, 1159–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosch, T.; Hassib, M.; Woźniak, P.W.; Buschek, D.; Alt, F. Your Eyes Tell: Leveraging Smooth Pursuit for Assessing Cognitive Workload. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems CHI’18, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-Vector Networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasri, M.; Kosa, M.; Chukoskie, L.; Moghaddam, M.; Harteveld, C. Exploring Eye Tracking to Detect Cognitive Load in Complex Virtual Reality Training. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality, Bellevue, WA, USA, 21–25 October 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, S.D.; Putnam, V.; Conati, C. Predicting Confusion from Eye-Tracking Data with Recurrent Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 Symposium on Eye Tracking Research and Applications, Denver, CO, USA, 25–28 June 2019; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.A.; Asadi, H.; Qazani, M.R.C.; Lim, C.P.; Nahavandi, S. Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) and Eye Tracking for Cognitive Load Classification in a Driving Simulator Using Deep Learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.06349. [Google Scholar]

- Oppelt, M.P.; Foltyn, A.; Deuschel, J.; Lang, N.R.; Holzer, N.; Eskofier, B.M.; Yang, S.H. ADABase: A Multimodal Dataset for Cognitive Load Estimation. Sensors 2022, 23, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ktistakis, E.; Skaramagkas, V.; Manousos, D.; Tachos, N.S.; Tripoliti, E.; Fotiadis, D.I.; Tsiknakis, M. COLET: A Dataset for Cognitive WorkLoad Estimation Based on Eye-Tracking. In Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine; Technical Report; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zaniolo, L.; Garbin, C.; Marques, O. Deep learning for edge devices. IEEE Potentials 2023, 42, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A.K.; Talwalkar, A.; Smith, V. Federated learning: Challenges, methods, and future directions. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2020, 37, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hard, A.; Rao, K.; Mathews, R.; Ramaswamy, S.; Beaufays, F.; Augenstein, S.; Eichner, H.; Kiddon, C.; Ramage, D. Federated Learning for Mobile Keyboard Prediction. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Paris, France, 21–22 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; He, B.; Song, D. Model-contrastive federated learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 10713–10722. [Google Scholar]

- Arivazhagan, M.G.; Aggarwal, V.; Singh, A.K.; Choudhary, S. Federated Learning with Personalization Layers. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.00818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman, R.E. A New Approach to Linear Filtering and Prediction Problems. J. Basic Eng. 1960, 82, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, G.; Bishop, G. An Introduction to the Kalman Filter; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Department of Computer Science: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mourikis, A.I.; Roumeliotis, S.I. A multi-state constraint Kalman filter for vision-aided inertial navigation. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Rome, Italy, 10–14 April 2007; pp. 3565–3572. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Song, L.; Zhang, M. Real-time facial landmark tracking using Kalman filter and cascaded regression. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2020, 138, 150–157. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, H. Real-time hand tracking using extended Kalman filter and dynamic motion model. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2019, 78, 32527–32546. [Google Scholar]

- de Boor, C. A Practical Guide to Splines; Applied Mathematical Sciences; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1978; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Picard, R.W. Affective Computing; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wickens, C.D.; Hollands, J.G.; Banbury, S.; Parasuraman, R. Applied Attention Theory; Human Factors and Ergonomics Series; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cowie, R.; Douglas-Cowie, E.; Tsapatsoulis, N.; Votsis, G.; Kollias, S.; Fellenz, W.; Taylor, J.G. Emotion recognition in human-computer interaction. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2001, 18, 32–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Tian, T. Affective computing: A review. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2005, 3784, 981–995. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi, Y.; Singh, A.; Kim, M.; Johnson, A.; Jeong, H. Effects of Head-locked Augmented Reality on User’s Performance and Perceived Workload. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.14068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehler, B.; Reimer, B.; Coughlin, J.C. The impact of incremental increases in cognitive workload on physiological arousal and performance in young adult drivers. Transp. Res. Rec. 2009, 2138, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacef, K.; Zaïane, O.; Pechenizkiy, M. Student modeling and cognitive load in adaptive learning systems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Educational Data Mining (EDM), Cordoba, Spain, 1–3 July 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nasri, M. Towards Intelligent VR Training: A Physiological Adaptation Framework for Cognitive Load and Stress Detection. In Proceedings of the 33rd ACM Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization UMAP’25, New York, NY, USA, 16–19 June 2025; pp. 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, R.W. Automating the Recognition of Stress and Emotion: From Lab to Real-World Impact. IEEE MultiMedia 2016, 23, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drole, K.; Doupona, M.; Steffen, K.; Jerin, A.; Paravlic, A. Associations between subjective and objective measures of stress and load: An insight from 45-week prospective study in 189 elite athletes. Front. Psychol. 2025, 15, 1521290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirschbaum, C.; Pirke, K.M.; Hellhammer, D.H. The ‘Trier Social Stress Test’—A Tool for Investigating Psychobiological Stress Responses in a Laboratory Setting. Neuropsychobiology 1993, 28, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLeod, C.M. Half a Century of Research on the Stroop Effect: An Integrative Review. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 109, 163–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronwall, D.M.A. Paced Auditory Serial-Addition Task: A measure of recovery from concussion. Percept. Mot. Skills 1977, 44, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dedovic, K.; Renwick, R.; Mahani, N.K.; Engert, V.; Lupien, S.J.; Pruessner, J.C. The Montreal Imaging Stress Task: Using Functional Imaging to Investigate the Effects of Perceiving and Processing Psychosocial Stress in the Human Brain. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2005, 30, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embrey, J.R.; Mason, A.; Newell, B.R. Too hard, too easy, or just right? The effects of context on effort and boredom aversion. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2024, 31, 2801–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saskovets, M.; Lohachov, M.; Liang, Z. Validation of a New Stress Induction Protocol Using Speech Improvisation (IMPRO). Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wel, P.; Steenbergen, H. Pupil dilation as an index of effort in cognitive control tasks: A review. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2018, 25, 2005–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshkati, N. Heart Rate Variability and Mental Workload Assessment. In Advances in Psychology; Human Mental Workload; Hancock, P.A., Meshkati, N., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1988; Volume 52, pp. 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, P.J.; Bradley, M.M.; Cuthbert, B.N. International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Affective Ratings of Pictures and Instruction Manual; Technical Report A-8, University of Florida; NIMH, Center for the Study of Emotion & Attention: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, A.M.; McMillan, K.M.; Laird, A.R.; Bullmore, E. N-back Working Memory Paradigm: A Meta-analysis of Normative Functional Neuroimaging Studies. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2005, 25, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Béquet, A.J.; Hidalgo-Muñoz, A.R.; Jallais, C. Towards Mindless Stress Regulation in Advanced Driver Assistance Systems: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 609124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Conde, S.; Macknik, S.L.; Martinez, L.M. Computational and Cognitive Neuroscience of Vision; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- König, P.; Wilming, N.; Kietzmann, T.C.; Ossandón, J.P.; Onat, S.; Ehinger, B.V.; Gameiro, R.R.; Kaspar, K. Eye Movements as a Window to Cognitive Processes. J. Eye Mov. Res. 2016, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bläsing, D.; Bornewasser, M. Influence of Increasing Task Complexity and Use of Informational Assistance Systems on Mental Workload. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Cedillo, A.; Gavrila, N.; Mishra, A.; Geangu, E.; Foulsham, T. Cognitive load affects gaze dynamics during real-world tasks. Exp. Brain Res. 2025, 243, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stasi, L.; Marchitto, M.; Antolí, A.; Cañas, J. Saccadic peak velocity as an alternative index of operator attention: A short review. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 63, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvucci, D.D.; Goldberg, J.H. Identifying fixations and saccades in eye-tracking protocols. In Proceedings of the 2000 Symposium on Eye Tracking Research & Applications; Association for Computing Machinery: Palm Beach Gardens, FL, USA; pp. 71–78. [CrossRef]

- Komogortsev, O.V.; Holland, C.D.; Karpov, A. Classification algorithm for eye movement-based biometrics. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2013, 8, 865–879. [Google Scholar]

- López, A.; Ferrero, F.J.; Qaisar, S.M.; Postolache, O. Gaussian Mixture Model of Saccadic Eye Movements. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Medical Measurements and Applications (MeMeA), Messina, Italy, 22–24 June 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, Z.; Kuntzelman, K.; Dodd, M.; Johnson, M. Convolutional neural networks can decode eye movement data: A black box approach to predicting task from eye movements. J. Vis. 2021, 21, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Behren, A.L.; Sauer, Y.; Severitt, B.; Wahl, S. CNN-based estimation of gaze distance in virtual reality using eye tracking and depth data. In Proceedings of the 2025 Symposium on Eye Tracking Research and Applications ETRA’25, New York, NY, USA, 26–29 May 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasneci, E.; Gao, H.; Ozdel, S.; Maquiling, V.; Thaqi, E.; Lau, C.; Rong, Y.; Kasneci, G.; Bozkir, E. Introduction to Eye Tracking: A Hands-On Tutorial for Students and Practitioners. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.15435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eye Tracking: The Complete Pocket Guide-iMotions—imotions.com. Available online: https://imotions.com/blog/learning/best-practice/eye-tracking/?srsltid=AfmBOoqaaAN6p1fMJIsgqM-7CEPgNN8_rFbJd5UgFnfO67ryRMZa7YJw (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Holmqvist, K.; Nyström, M.; Andersson, R.; Dewhurst, R.; Jarodzka, H.; Van de Weijer, J. Eye Tracking: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods and Measures; Holmqvist, K., Nyström, N., Andersson, R., Dewhurst, R., Jarodzka, H., Van de Weijer, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.K.; Nicolescu, M.; Nicolescu, M. Enhancing Robotic Task Parameter Estimation Through Unified User Interaction: Gestures and Verbal Instructions in Collaboration. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Robotics and Automation Sciences (ICRAS), Tokyo, Japan, 21–23 June 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation); Official Journal of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; pp. 1–88. [Google Scholar]

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; y Arcas, B.A. Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS), Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 20–22 April 2017; pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Beutel, D.J.; Topal, T.; Mathur, A.; Qiu, X.; Fernandez-Marques, J.; Gao, Y.; Sani, L.; Li, K.H.; Parcollet, T.; de Gusmão, P.P.B.; et al. Flower: A Friendly Federated Learning Framework. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2007.14390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, S.; Esbensen, K.; Geladi, P. Principal Component Models in Shape Analysis; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bookstein, F.L. Morphometric Tools for Landmark Data: Geometry and Biology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Trajectory | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 | MCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circular-Slow | 0.74 | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.44 |

| Circular-Fast | 0.84 | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.61 |

| Rectangular-Slow | 0.71 | 0.88 | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.31 |

| Rectangular-Fast | 0.90 | 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.76 |

| Sinusoidal-Slow | 0.76 | 0.88 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.41 |

| Sinusoidal-Fast | 0.97 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.88 |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 | MCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kosch | 0.82 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.26 |

| KF-based Model | 0.68 | 0.94 | 0.67 | 0.77 | 0.30 |

| B-Spline Approximation | 0.68 | 0.94 | 0.68 | 0.79 | 0.29 |

| Adaptive Thresholding | 0.75 | 0.94 | 0.75 | 0.83 | 0.36 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dell’Acqua, P.; Garofalo, M.; La Rosa, F.; Villari, M. Your Eyes Under Pressure: Real-Time Estimation of Cognitive Load with Smooth Pursuit Tracking. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2025, 9, 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc9110288

Dell’Acqua P, Garofalo M, La Rosa F, Villari M. Your Eyes Under Pressure: Real-Time Estimation of Cognitive Load with Smooth Pursuit Tracking. Big Data and Cognitive Computing. 2025; 9(11):288. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc9110288

Chicago/Turabian StyleDell’Acqua, Pierluigi, Marco Garofalo, Francesco La Rosa, and Massimo Villari. 2025. "Your Eyes Under Pressure: Real-Time Estimation of Cognitive Load with Smooth Pursuit Tracking" Big Data and Cognitive Computing 9, no. 11: 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc9110288

APA StyleDell’Acqua, P., Garofalo, M., La Rosa, F., & Villari, M. (2025). Your Eyes Under Pressure: Real-Time Estimation of Cognitive Load with Smooth Pursuit Tracking. Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 9(11), 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc9110288