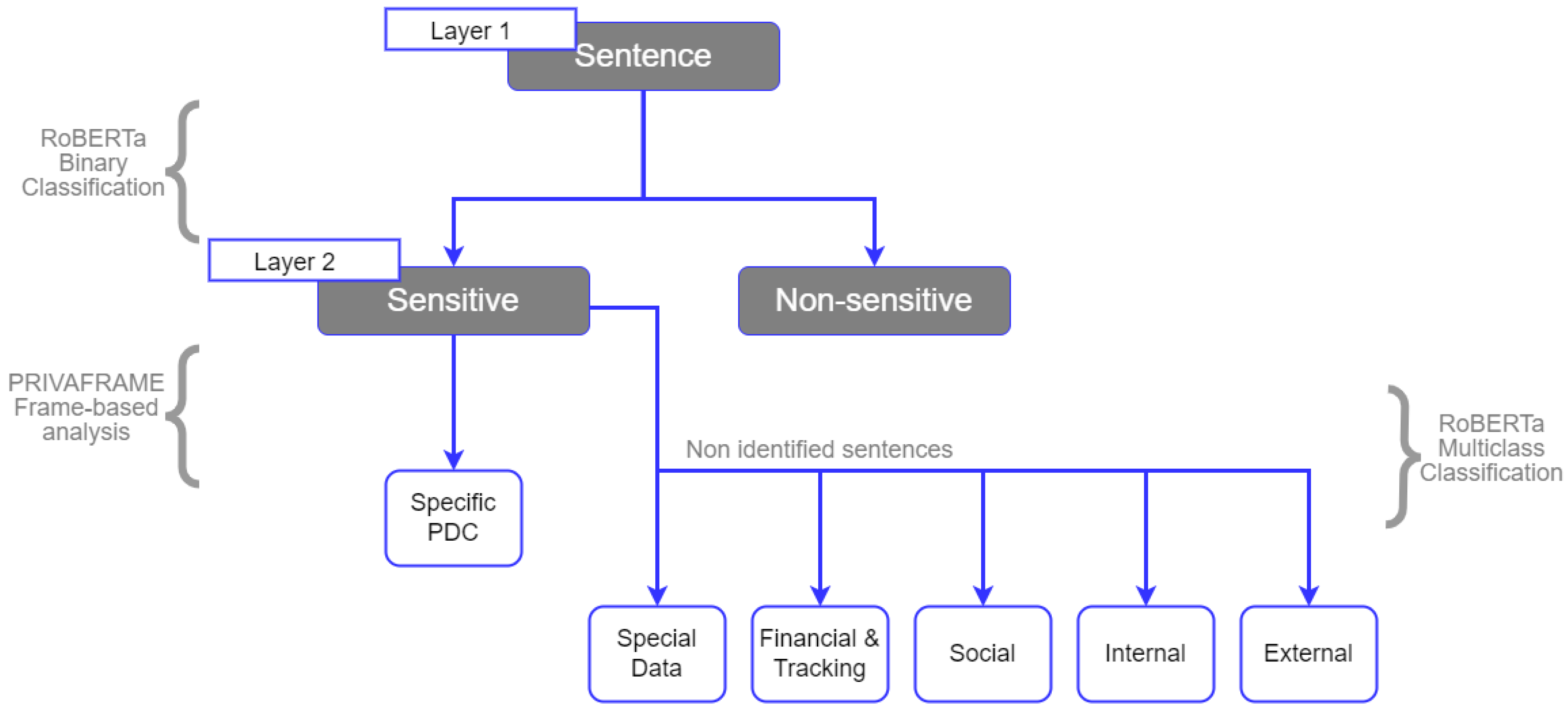

5.1. Experimental Process

PRIVAFRAME experiment. For the evaluation of the model, SPeDaC3 was used. The resource presents only one labeled PDC per sentence. First, 34% of the dataset was used for preliminary tests to refine the model during its design, and the PDCs were analyzed in a balanced way. The rest of SPeDaC3 constituted the test set, which included 3671 sentences. Those sentences were multi-tagged; e.g., sentence-level labels were added when they included more than one specific PDC. Furthermore, some PDCs were merged by similarity, e.g.,

Criminal Charge,

Conviction and

Pardon, which were considered under the more generic

Criminal PDC. The target labels were in total 33. The detailed distribution can be seen in Table 6. The test-set can be found in the PRIVAFRAME repository:

https://github.com/Gaia-G/PRIVAFRAME, accessed on 3 August 2022. Due to the aforementioned ethical concerns (

Section 3.2), the evaluation labeled dataset and the developed python script can be downloaded in order to replicate the experimental process once an ethical use agreement is signed by interested parties.

The knowledge graph currently includes the representation of broad-boundaries categories as well. These have not been evaluated yet, as they would require a newly labeled dataset.

For the dataset analysis, the tool used was FRED [

41]. FRED [

42] is an automatic reader for the Semantic Web: it is able to analyze natural language text and transform it into linked data (RDF, resource description framework, and OWL knowledge graphs). It is implemented in Python and available as a REST service and as a suite of Python libraries (fredlib). FRED can get and return Framester alignments. After extracting frames and WordNet synsets with FRED, the semantic elements identified in each sentence were automatically matched to the compositional frames of our knowledge graph, and each sentence was labeled accordingly with the prediction of one or more PDCs.

Comparison experiment. As underlined in

Section 2 and

Section 3, one of the major problems in the SID task lies in the lack of a common benchmark. Related studies differ greatly in terms of language, domain and approach adopted. With the construction and evaluation of the SPeDaC datasets [

25], a new benchmark on PDCs domain has been proposed. In the previous study, SPeDaC1 and SPeDaC2 were evaluated with a neural network approach. The same approach, based on the RoBERTa transformer model, was used on the PRIVAFRAME evaluation dataset as a comparison model.

The dataset was randomly split into training, validation and test sets (see

Table 5). A single label sentence-level annotation was used (the annotation can be found in the dataset at the aforementioned GitHub repository) for the multiclassification task.

The RoBERTa-base model used presents pre-trained weights and 768 hidden dimensions; the maximum sequence length was set to 256 and the train lot size to 8. AdamW optimizer [

43] was used to optimize the model, and a learning rate of 1e-5 was set. The performance was evaluated by the loss of binary cross entropy.

5.2. Experimental Results

PRIVAFRAME experiment. Concerning correctly identified labels, even on multi-labeled sentences, the model achieved an accuracy of 78%; 75% of the sentences (single and multi-labeled) obtained complete identification of the PDCs labels, and 10.2% obtained partial correctness (e.g., not all the labels of the sentence have been predicted). However, it was necessary to analyze the fine-grained analysis performed by the model. You can see the number of detected labels (true positives, TP) for each PDC and an overview in

Table 6. In the table you can also see the number of false positives (FP): the model reached a precision of 60%.

Some PDCs were almost always identified, e.g.,

Disability,

Name,

Personal Possession and

Relationship; and we can observe particularly critical categories, e.g.,

Political Affiliation,

Professional Certification,

Professional Evaluation and

Reference.

Table 7 presents an overview.

The model performances on the PDCs are calculated in terms of accuracy (the ratio between correct predictions and total predictions for each category).

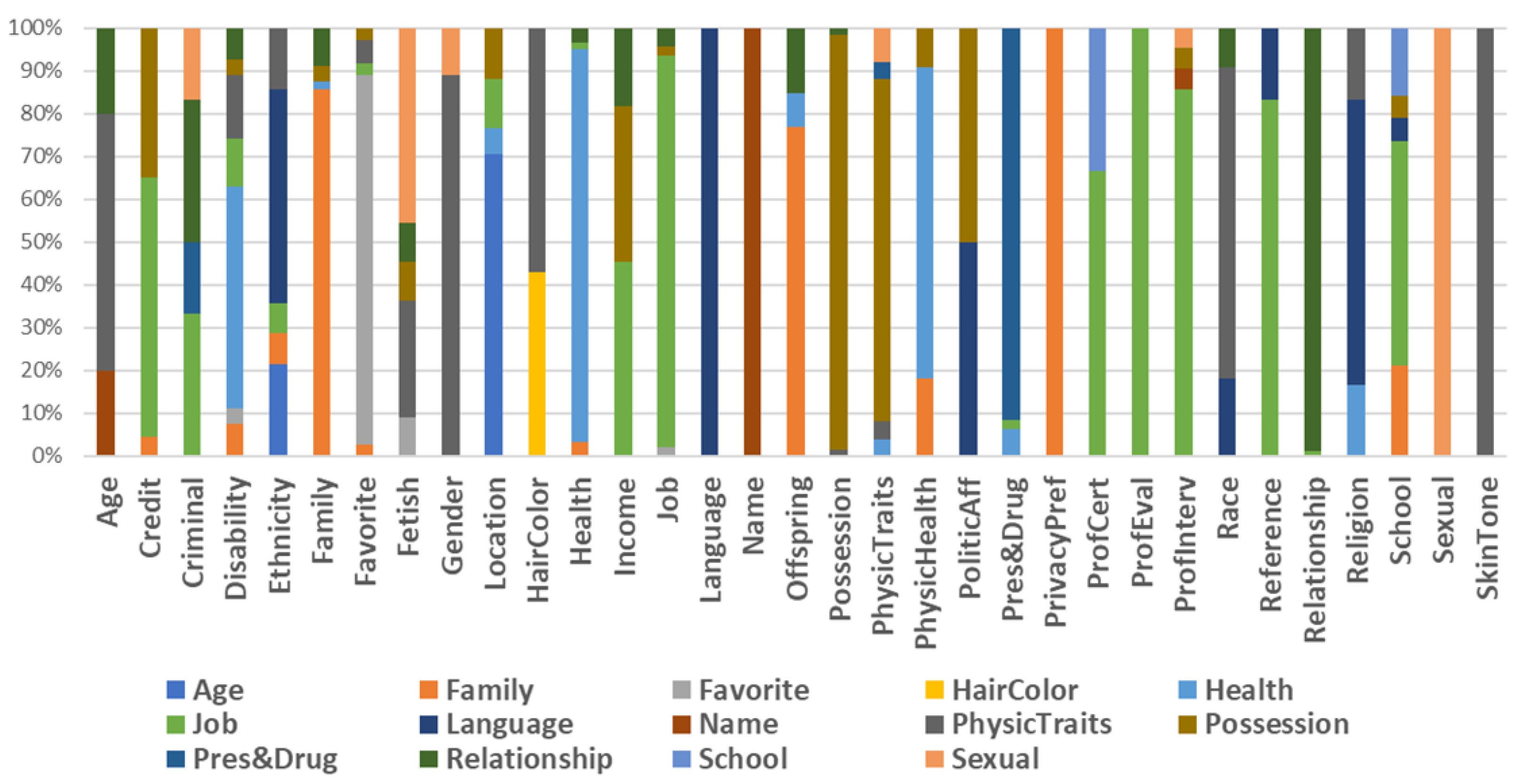

Comparison experiment. The multiclassification model achieved 66% accuracy. As

Figure 3 shows, not all the PDCs can be found in the predictions. Some PDCs were well classified, e.g.,

Favorite,

Health,

Job,

Language,

Possession,

Prescription & Drug Test Result,

Relationship and

Sexual. Others received a logically justifiable classification; e.g.,

Offspring was often classified as

Family, and

Skin Tone was classified as

Physical Traits. Finally, there are categories for which an erroneous classification could instead be observed:

Disability and

Religion were often classified as

Language, and

Criminal was often classified as

Health.

Table 8 presents the comparison data.

Error analysis. The rule-based model can be fully explained through an in-depth analysis of the extracted frames, and consequently of the assumptions made. We can identify three main types of recurring hypothesized errors due to the following reasons: (a) Failure of FRED on frames extraction; (b) Lacks or complexity in compositional frame modeling; (c) Errors due to the structure of the sample sentences to be identified (too complex or with few distinctive features). Some errors may likewise be due to dataset labeling errors, but these cannot be assumed as recurring for specific categories. In the error analysis, for each point analyzed we will report in brackets the type(s) of error hypothesized (a, b, or c). The PDCs which report an evident criticality (−55% of TP sentences) can be first observed:

Age (a,c): Age labeling is often not correctly defined. Analyzing the error frequently in detail: it seems to have been due to the failure of FRED in frames’ extraction. In fact, it is possible to observe sentences, e.g., “[…] i am a 31 year old woman,” being correctly identified, and at the same time sentences, e.g., “Hi My name is Megisiana (Megi) I am 13 years old […],” in which the label Age is missing. Sometimes, the problem was also due to the structure of the sentence, which does not contain sufficient elements for identification, e.g., “I am 24 male.”

Physical Traits (b): The generic category includes specific PDCs, namely, Height, Weight, Tattoo and Piercing. If the PDC Height is often identified, this not happens for Weight. There are no significant complexities concerning the variety or structure of the sentences. The compositional frame is very articulated, with both AND and OR relationships. FRED identifies some of the interested frames but rarely manages to reconstruct the complete composition. A more generic rule could be modeled, losing a few points in precision. As for the Tattoo and Piercing PDCs, the problem lies in the fact that compositional frames to adequately represent the categories could not be found. However, these categories were not even identified on a more generic level, such as Physical Traits. Again, a different modeling strategy should be investigated.

Political Affiliation, Privacy Preference, Professional Certification, Professional Evaluation, Race and Reference (b,c): these PDCs are represented by rather articulated compositional frames. As it can be seen, they had a very low number of or zero FP. In particular, sentences that represent Professional Certification, e.g., “I had a diploma”, often have the double labeling School and Personal Possession; Professional Evaluation was often confused with Professional Interview. The sentences representing Reference often were labeled with School and Professional. In these cases, more generic modeling, or a merging of specific PDCs into one could address the problem. It is also advisable to increase the number of sample sentences. Those tested are structurally complex and very varied from each other.

Problems related to FRED’s missed frame extraction (a) are also highlighted for PDCs e.g., Gender and Religion, in which sentences with recurring structures and LUs were not always identified. Other PDCs could perhaps improve their accuracy through an expansion of the LUs with which they are represented (b), e.g., Ethnicity, Family, Parent & Sibling, Physical Health and Sexual. Others may appear in the form of structurally more varied sentences and are represented by more complex and sometimes too articulated compositional frames, so it would be advisable first of all to intervene in modeling (b,c), e.g., Credit & Salary, Fetish and Professional Interview.

In relation to the precision score, there are some PDCs that produce a large number of FP compared to the number of TP, e.g., Age, Credit & Salary, Demographic, Country & Location, Job, Professional, Employment & Work History and Personal Possession. In particular, the following observations are highlighted:

Age: The sentences in which Age is present as FP contain elements related to age not directly attributable to the subject. Age could refer to non-animated things (e.g., the car purchased by the subject) or events (e.g., “My Mum had bowel cancer about 7 years ago”) or subjects not directly identifiable (e.g., “I am married with 2 children,” where the information directly associated with the subject concerns the Family PDC).

Credit & Salary: The compositional frame Earnings_and_Losses tends to expand its labeling to sentences that contain LUs attributable to gain and loss in a broad sense.

Demographic, Country & Location: FP often concern sentences that present personal information about the individual’s history (Work Employment, Health History), in which some information concerning the individual’s movements could be presumed; or, information belonging to the Car Owned or House Owned PDCs in which, in the same way, movements or transfers are mentioned (e.g., “I bought a home and after 6 years of living there I rented it to my first tenant”; “I trained and worked as an electrician for six years before deciding to go to college”).

Job, Professional, Employment & Work History: Many identifications are confused with the Family and Relationship PDCs’ presence, as the profession of a family member or of a person with whom the interested subject has a relationship is made explicit; or with the Prescription & Drug Test Result PDC, because the figure of the attending physician is appointed. In addition, there are many sentences that are labeled with the PDC School that also have the Professional label. The confusion could be reduced by introducing more specific rules that represent the PDC.

Personal Possession: This category has a highest number of FP. Personal Possession and Ownership are very generic PDCs; it is sufficient for identification that in the sentence the subject refers to something that belongs to him, not necessarily material (e.g., “I have a terrible headache”). If we observe the FP of the more specific Car Owned, House Owned and Apartment Owned, the FP are significantly reduced to 33.

For number 5, and in part for number 3, the problem, therefore, lies in the too much potential extension of the PDC, and certainly, the identification becomes more precise when it is reduced to more detailed sub-PDCs. Problems 1, 2 and 4 should instead be faced with the design of additional rules that strengthen the labeling (presumably consequently finding an accuracy decrease).

Finally, the results of the deep learning model on fine-grained PDCs identification are presented. The BERT-based model returns as output only a some of the labels on which it is trained, and mostly tends not to recognize very specific PDCs. E.g., Disability, Offspring, Income Bracket and Physical Health do not produce any output. The model provides a single label classification, but above all, it strongly depends on the training sentences that are provided to it. It is not difficult to think how much its performance could increase if larger training sets were provided for each of the proposed labels. However, if, as in this case, the labeled data available are likely to be scarce compared to the number of labels to be identified, the knowledge graph approach is more accurate.