Reynolds Sensitivity of the Wake Passing Effect on a LPT Cascade Using Spectral/hp Element Methods †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

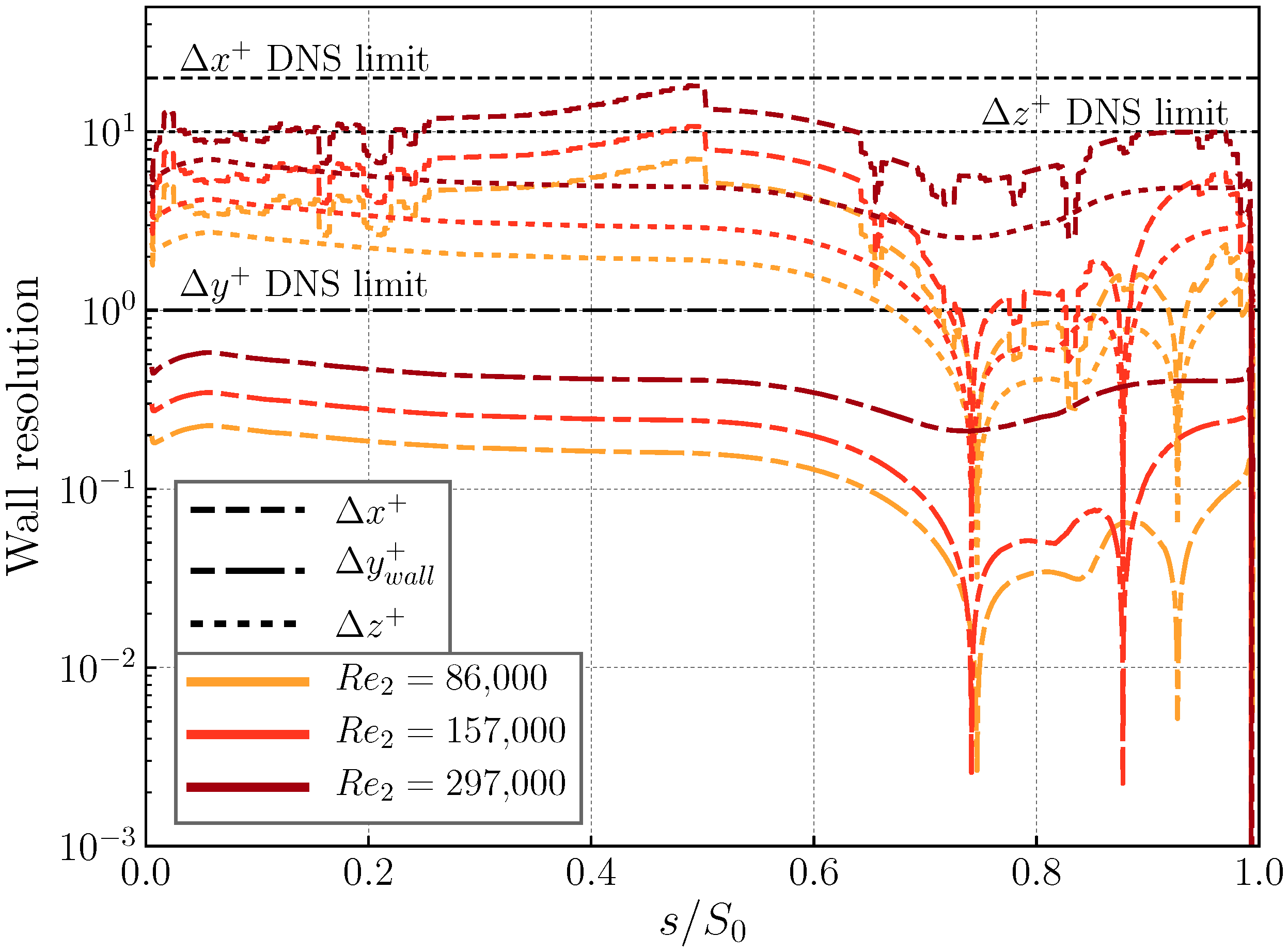

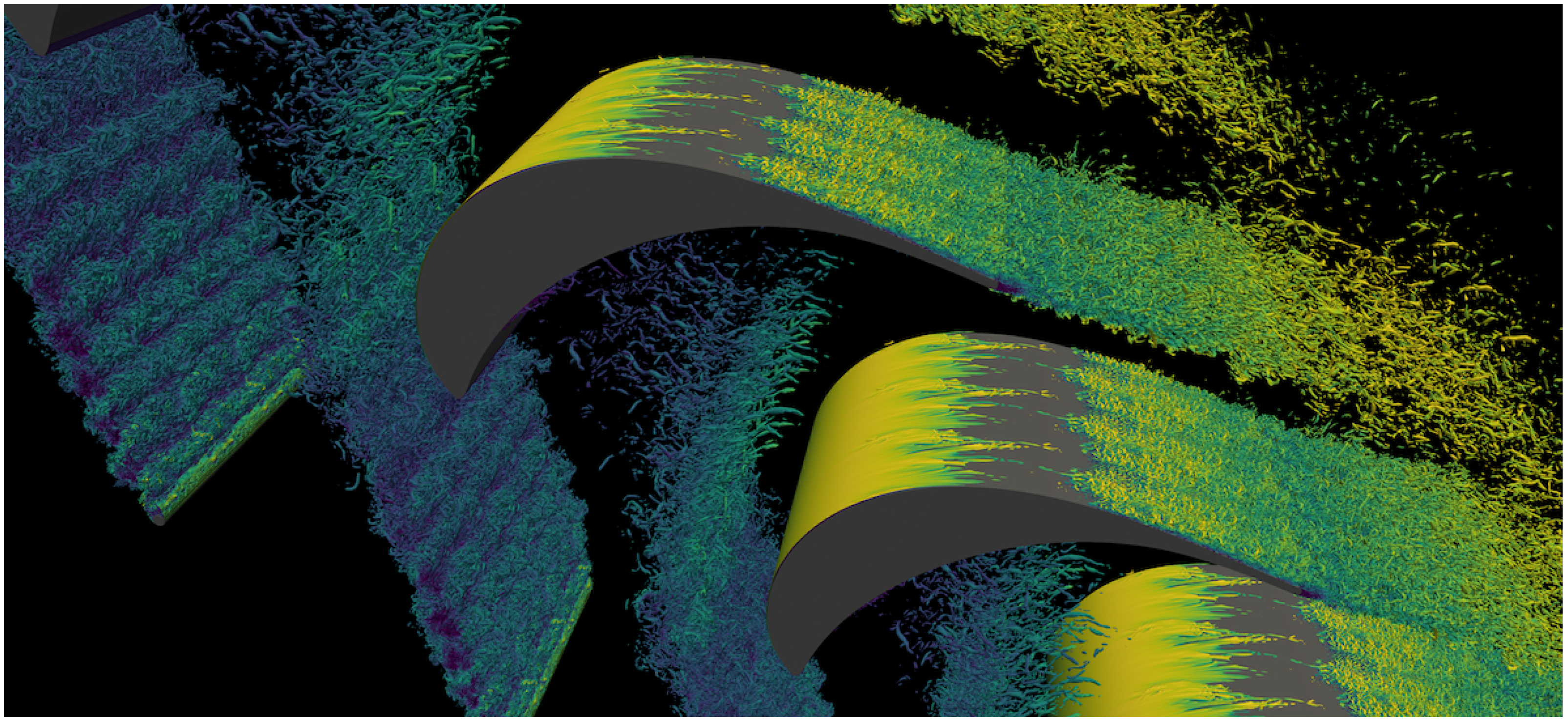

2. Methods

2.1. Numerical Approach

2.2. LPT Setup with Wake Passing

2.3. Modelling the Bar Passing Effect

2.4. Low-Speed Experimental Testing of LPTs

3. Results

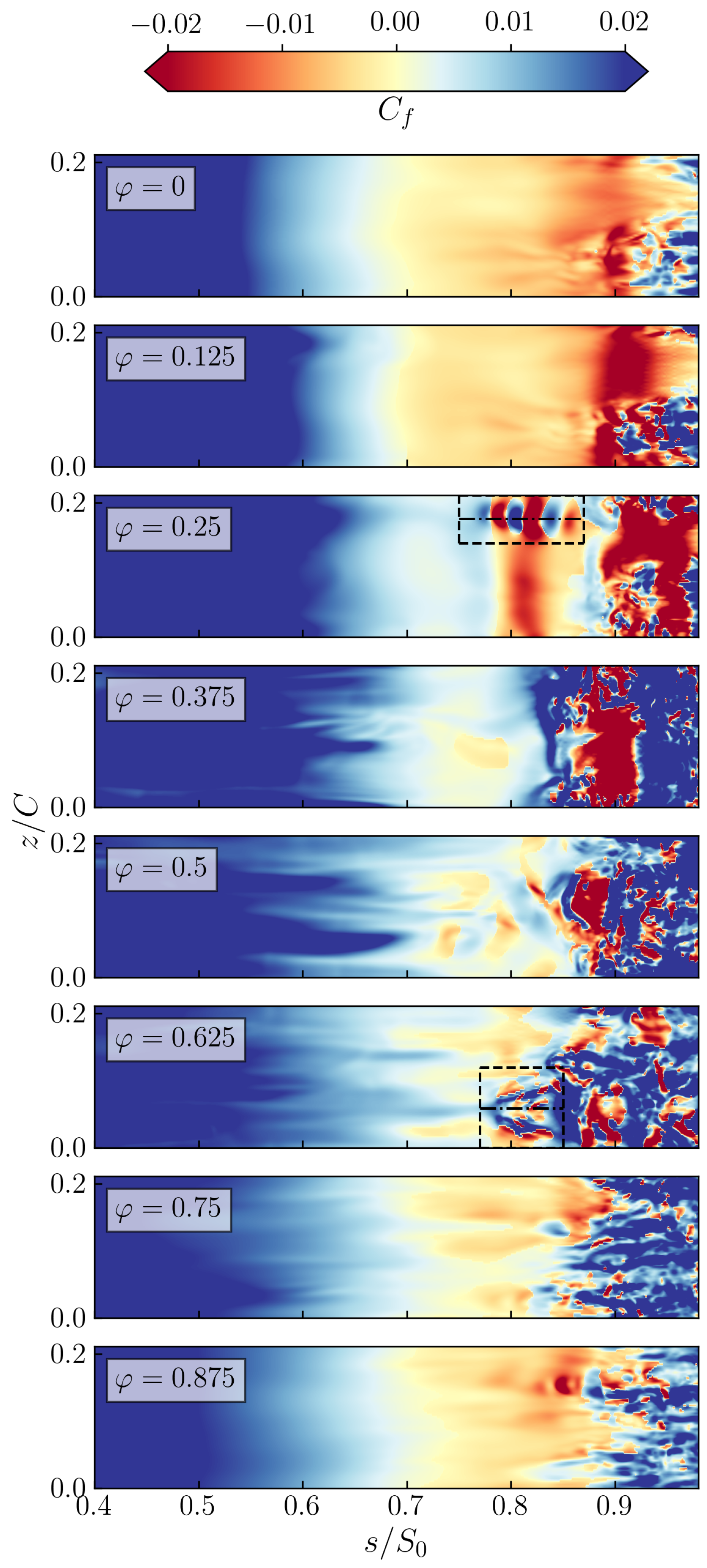

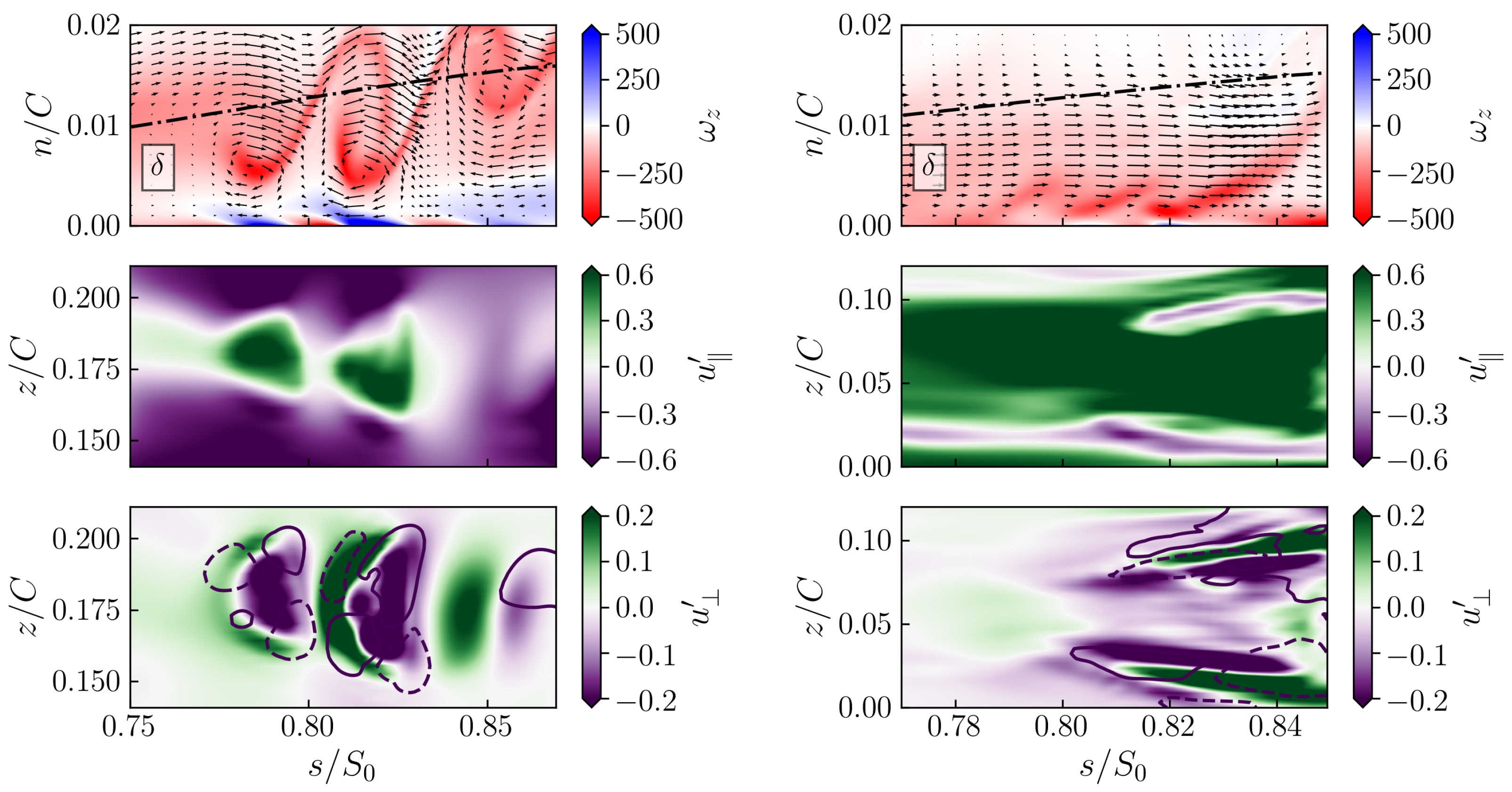

3.1. Evidence of the Transition Mechanism

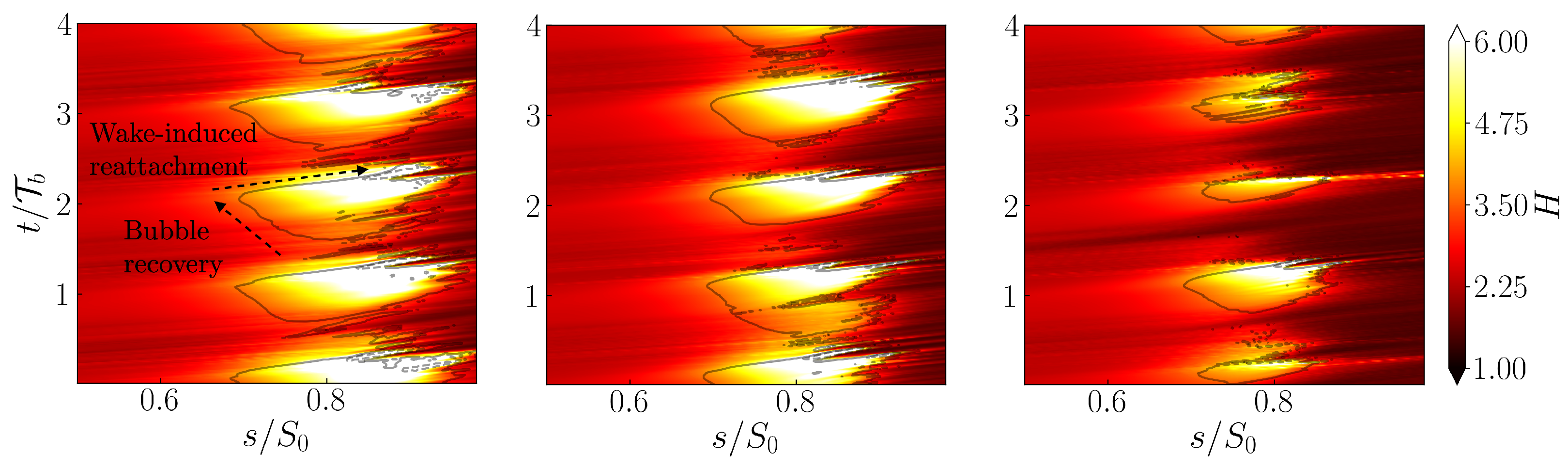

3.2. Space-Time Boundary Layer Behaviour

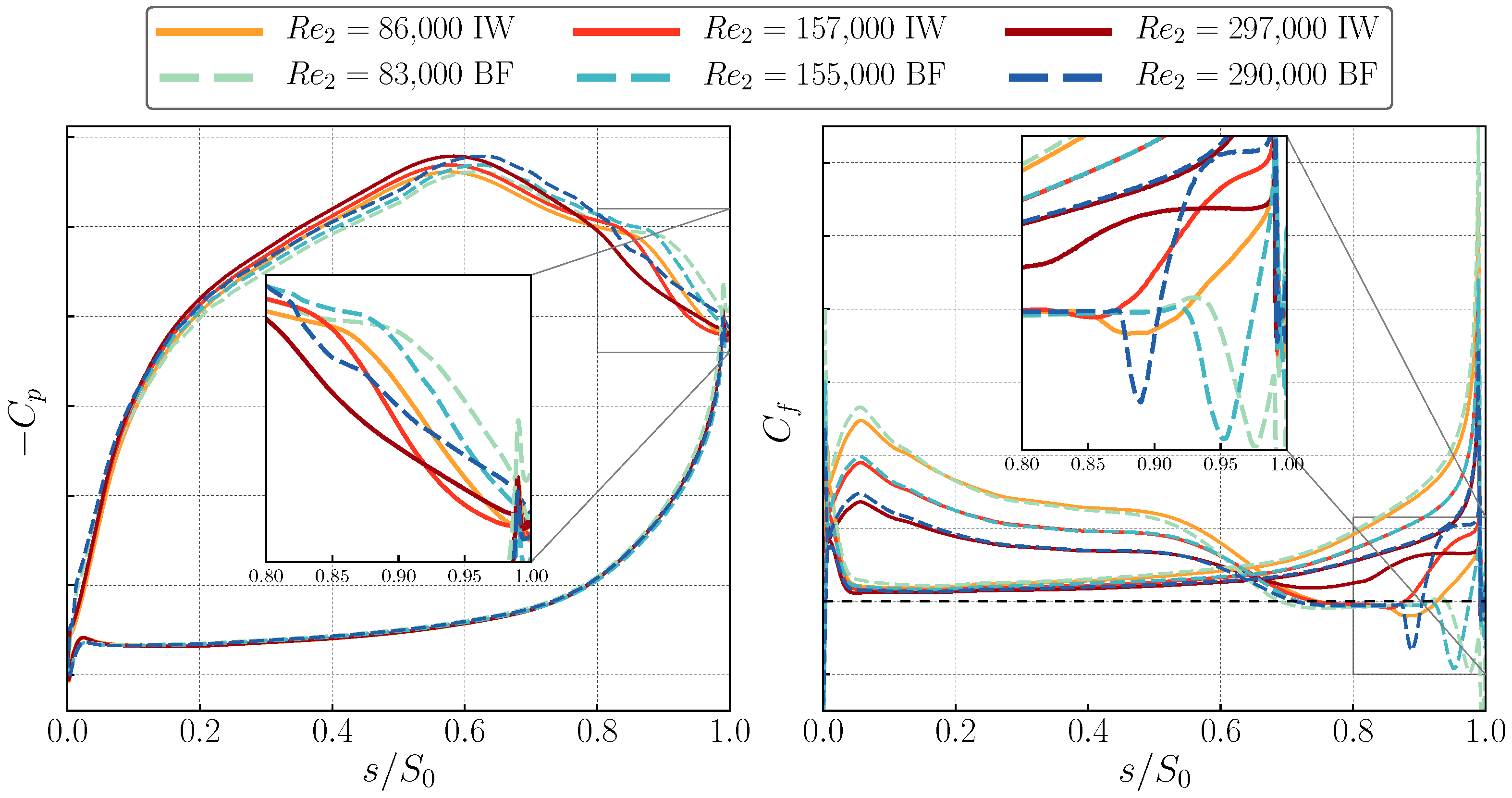

3.3. Blade Wall Distributions

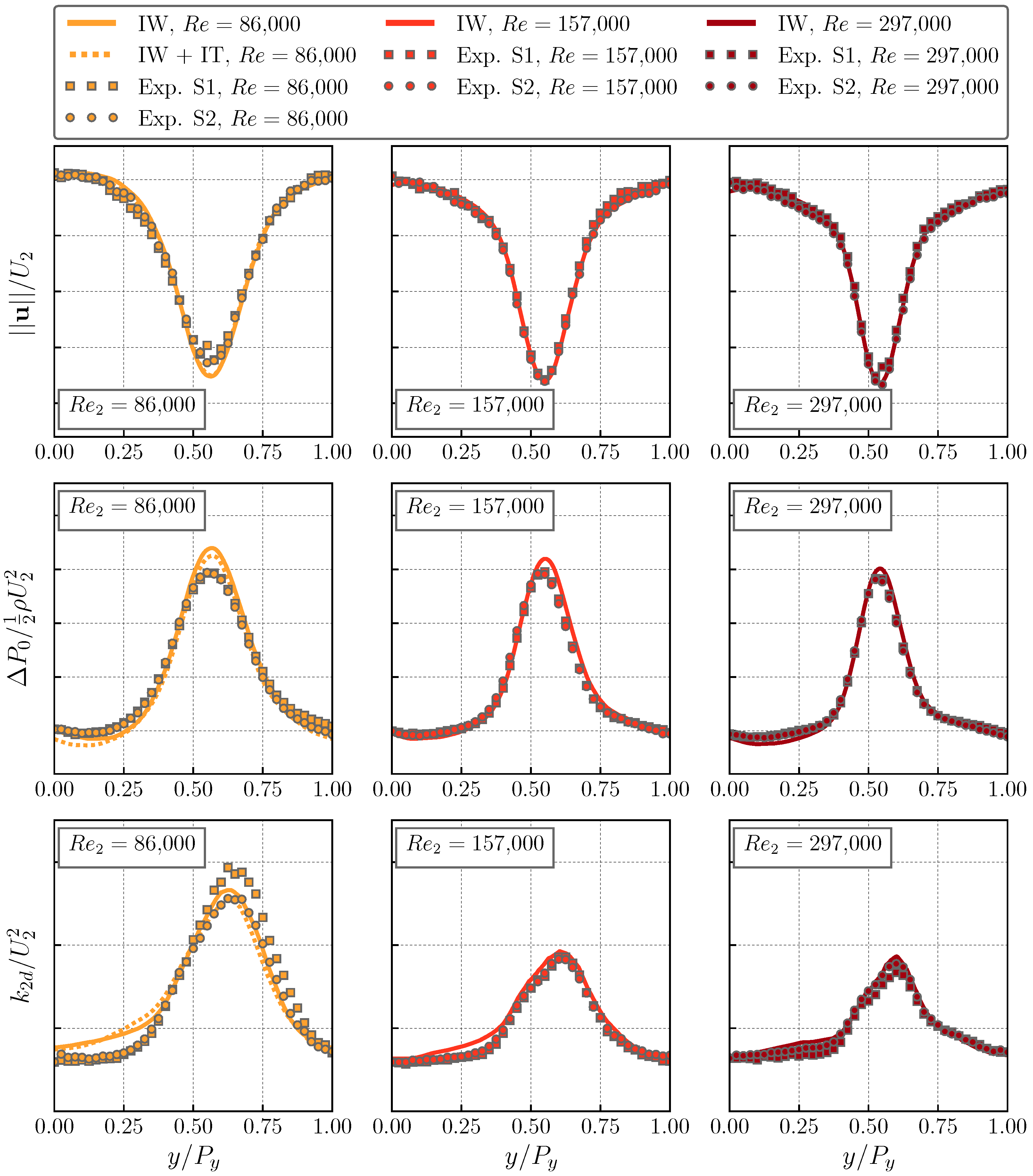

3.4. Wake Traverses and Experimental Comparison

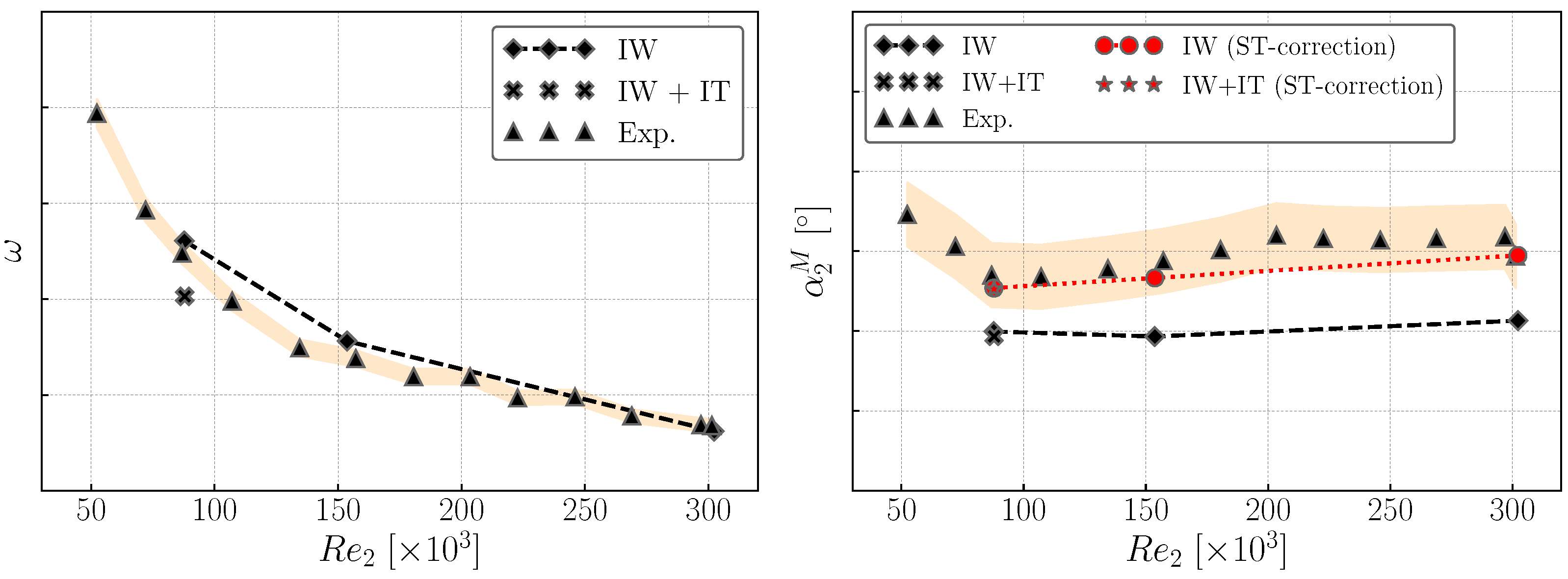

3.5. Mixed-Out Measurements

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations and Nomenclature

Abbreviations

| BF | Body Forcing |

| BL | Boundary Layer |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| DNS | Direct Numerical Simulation |

| IW | Inflow Wakes |

| IT | Inflow Turbulence |

| LDA | Laser Doppler Anemometry |

| LES | Large-Eddy Simulation |

| LPT | Low Pressure Turbine |

| RANS | Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes |

| SVV | Spectral Vanishing Viscosity |

| TI | Turbulence Intensity |

| URANS | Unsteady RANS |

Nomenclature

| Flow angle | |

| Total pressure loss coefficient | |

| Flow coefficient | |

| Wake passing phase | |

| Blade (axial) chord length | |

| Skin friction coefficient | |

| Static pressure coefficient | |

| Reduced frequency | |

| H | Boundary layer shape factor |

| k | Turbulence kinetic energy |

| Turbulence length scale | |

| Spanwise domain size | |

| n | Blade wall-normal distance |

| Number of Fourier planes | |

| p | Pressure |

| P | Polynomial order |

| Bars pitch | |

| Blade pitch | |

| Reynolds number | |

| Suction surface perimeter | |

| Time | |

| Wake passing period | |

| Bar speed | |

| Mixed-out exit velocity | |

| Reference inlet speed |

References

- Wu, X.; Jacobs, R.G.; Hunt, J.C.R.; Durbin, P.A. Simulation of boundary layer transition induced by periodically passing wakes. J. Fluid Mech. 1999, 398, 109–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, X.; Durbin, P.A. Evidence of longitudinal vortices evolved from distorted wakes in a turbine passage. J. Fluid Mech. 2001, 446, 199–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelassi, V.; Wissink, J.G.; Fröhlich, J.; Rodi, W. Large-Eddy Simulation of Flow Around Low-Pressure Turbine Blade with Incoming Wakes. AIAA J. 2003, 41, 2143–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelassi, V.; Wissink, J.G.; Rodi, W. Direct numerical simulation, large eddy simulation and unsteady Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes simulations of periodic unsteady flow in a low-pressure turbine cascade: A comparison. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part A J. Power Energy 2003, 217, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissink, J.G. DNS of separating, low Reynolds number flow in a turbine cascade with incoming wakes. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2003, 24, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissink, J.G.; Rodi, W. Direct numerical simulation of flow and heat transfer in a turbine cascade with incoming wakes. J. Fluid Mech. 2006, 569, 209–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, H.P.; Howell, R.J. Bladerow Interactions, Transition, and High-Lift Aerofoils in Low-Pressure Turbines. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2005, 37, 71–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelassi, V.; Chen, L.; Pichler, R.; Sandberg, R.D. Compressible Direct Numerical Simulation of Low-Pressure Turbines—Part II: Effect of Inflow Disturbances. J. Turbomach. 2015, 137, 071005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, R.D.; Michelassi, V.; Pichler, R.; Chen, L.; Johnstone, R. Compressible Direct Numerical Simulation of Low-Pressure Turbines—Part I: Methodology. J. Turbomach. 2015, 137, 051011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Denton, J.D. The 1993 IGTI Scholar Lecture: Loss Mechanisms in Turbomachines. J. Turbomach. 1993, 115, 621–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelassi, V.; Chen, L.; Pichler, R.; Sandberg, R.; Bhaskaran, R. High-Fidelity Simulations of Low-Pressure Turbines: Effect of Flow Coefficient and Reduced Frequency on Losses. J. Turbomach. 2016, 138, 111006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassinelli, A.; Montomoli, F.; Adami, P.; Sherwin, S.J. High Fidelity Spectral/hp Element Methods for Turbomachinery. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2018: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition, Oslo, Norway, 11–15 June 2018; Volume 2C: Turbomachinery. p. GT2018-75733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassinelli, A.; Xu, H.; Montomoli, F.; Adami, P.; Vazquez Diaz, R.; Sherwin, S.J. On the Effect of Inflow Disturbances on the Flow Past a Linear LPT Vane Using Spectral/hp Element Methods. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2019: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 17–21 June 2019; Volume 2C: Turbomachinery. p. GT2019-91622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassinelli, A.; Mateo Gabin, A.; Montomoli, F.; Adami, P.; Vazquez Diaz, R.; Sherwin, S.J. Reynolds Sensitivity of the Wake Passing Effect on a LPT Cascade Using Spectral/hp Element Methods. In Proceedings of the European Turbomachinery Conference ETC14 2021, Gdansk, Poland, 12–16 April 2021. Paper No. 606. [Google Scholar]

- Moxey, D.; Cantwell, C.D.; Bao, Y.; Cassinelli, A.; Castiglioni, G.; Chun, S.; Juda, E.; Kazemi, E.; Lackhove, K.; Marcon, J.; et al. Nektar++: Enhancing the capability and application of high-fidelity spectral/hp element methods. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2019, 249, 107110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karniadakis, G.E.; Israeli, M.; Orszag, S.A. High-order splitting methods for the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations. J. Comput. Phys. 1991, 97, 414–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guermond, J.L.; Shen, J. Velocity-Correction Projection Methods for Incompressible Flows. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2003, 41, 112–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadmor, E. Convergence of Spectral Methods for Nonlinear Conservation Laws. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1989, 26, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, R.C.; Sherwin, S.J.; Peiró, J. Eigensolution analysis of spectral/hp continuous Galerkin approximations to advection-diffusion problems: Insights into spectral vanishing viscosity. J. Comput. Phys. 2016, 307, 401–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moura, R.C.; Aman, M.; Peiró, J.; Sherwin, S.J. Spatial eigenanalysis of spectral/hp continuous Galerkin schemes and their stabilisation via DG-mimicking spectral vanishing viscosity for high Reynolds number flows. J. Comput. Phys. 2020, 406, 109112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengaldo, G.; De Grazia, D.; Moxey, D.; Vincent, P.E.; Sherwin, S.J. Dealiasing techniques for high-order spectral element methods on regular and irregular grids. J. Comput. Phys. 2015, 299, 56–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cassinelli, A. A Spectral/Hp Element DNS Study of Flow Past Low-Pressure Turbine Cascades and the Effects of Inflow Conditions. Ph.D. Thesis, Imperial College London, London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, L. Using isotropic synthetic fluctuations as inlet boundary conditions for unsteady simulations. Adv. Appl. Fluid Mech. 2007, 1, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama, Y.; Yamamoto, R. Simulation method to resolve hydrodynamic interactions in colloidal dispersions. Phys. Rev. E 2005, 71, 036707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luo, X.; Maxey, M.R.; Karniadakis, G.E. Smoothed profile method for particulate flows: Error analysis and simulations. J. Comput. Phys. 2009, 228, 1750–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Triantafyllou, M.S.; Constantinides, Y.; Karniadakis, G.E. A spectral-element/Fourier smoothed profile method for large-eddy simulations of complex VIV problems. Comput. Fluids 2018, 172, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez Diaz, R.; Torre, D. The Effect of Mach Number on the Loss Generation of LP Turbines. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2012: Turbine Technical Conference and Exposition. Volume 8: Turbomachinery, Parts A, B, and C, Copenhagen, Denmark, 11–15 June 2012; pp. 1131–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, M.; Hodson, H.P. Low Speed vs High Speed Testing of LP Turbine Blade-Wake Interaction. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Measuring Techniques in Transonic and Supersonic Flow in Cascades and Turbomachines, Cambridge, UK, 23–24 September 2002; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Marconcini, M.; Rubechini, F.; Pacciani, R.; Arnone, A.; Bertini, F. Redesign of High-Lift Low Pressure Turbine Airfoils for Low Speed Testing. J. Turbomach. 2012, 134, 051017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, R.G.; Durbin, P.A. Simulations of bypass transition. J. Fluid Mech. 2001, 428, 185–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, T.A. From streaks to spots and on to turbulence: Exploring the dynamics of boundary layer transition. Flow Turbul. Combust. 2013, 91, 451–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sandberg, R.D. Bypass transition in boundary layers subject to strong pressure gradient and curvature effects. J. Fluid Mech. 2020, 888, A4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.C.; Durbin, P.A. Perturbed vortical layers and shear sheltering. Fluid Dyn. Res. 1999, 24, 375–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durbin, P.; Wu, X. Transition Beneath Vortical Disturbances. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2007, 39, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, T.A.; Durbin, P.A. Continuous mode transition and the effects of pressure gradient. J. Fluid Mech. 2006, 563, 357–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zaki, T.A.; Durbin, P.A. Floquet analysis of secondary instability of boundary layers distorted by Klebanoff streaks and Tollmien-Schlichting waves. Phys. Fluids 2008, 20, 124102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolinches-Gisbert, M.; Robles, D.C.; Corral, R.; Gisbert, F. Prediction of Reynolds Number Effects on Low-Pressure Turbines Using a High-Order ILES Method. J. Turbomach. 2020, 142, 031002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey Marioni, Y.; de Toledo Ortiz, E.A.; Cassinelli, A.; Montomoli, F.; Adami, P.; Vazquez, R. A Machine Learning Approach to Improve Turbulence Modelling from DNS Data Using Neural Networks. Int. J. Turbomach. Propuls. Power 2021, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Re2 | (IW, IW+IT) | (IW) | (IW) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (-based) | 0.624132 | 0.627675 | 0.633188 |

| 0.705339 | 0.706414 | 0.708116 | |

| 1.17731 | 1.17414 | 1.16966 | |

| 33.86 | 33.96 | 34.08 | |

| Compute time for | 8 h 40 min | 8 h 40 min | 10 h 45 min |

| Parameter | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.919 | 5.388 | 2.516 | |

| 0.563 | 0.757 | 0.841 | |

| 0.129 | 0.171 | 0.187 | |

| −1.164 | −1.564 | −1.734 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-ND) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cassinelli, A.; Mateo Gabín, A.; Montomoli, F.; Adami, P.; Vázquez Díaz, R.; Sherwin, S.J. Reynolds Sensitivity of the Wake Passing Effect on a LPT Cascade Using Spectral/hp Element Methods. Int. J. Turbomach. Propuls. Power 2022, 7, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijtpp7010008

Cassinelli A, Mateo Gabín A, Montomoli F, Adami P, Vázquez Díaz R, Sherwin SJ. Reynolds Sensitivity of the Wake Passing Effect on a LPT Cascade Using Spectral/hp Element Methods. International Journal of Turbomachinery, Propulsion and Power. 2022; 7(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijtpp7010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleCassinelli, Andrea, Andrés Mateo Gabín, Francesco Montomoli, Paolo Adami, Raul Vázquez Díaz, and Spencer J. Sherwin. 2022. "Reynolds Sensitivity of the Wake Passing Effect on a LPT Cascade Using Spectral/hp Element Methods" International Journal of Turbomachinery, Propulsion and Power 7, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijtpp7010008

APA StyleCassinelli, A., Mateo Gabín, A., Montomoli, F., Adami, P., Vázquez Díaz, R., & Sherwin, S. J. (2022). Reynolds Sensitivity of the Wake Passing Effect on a LPT Cascade Using Spectral/hp Element Methods. International Journal of Turbomachinery, Propulsion and Power, 7(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijtpp7010008