Experimental Validation of an Analytical Condensation Model for Application in Steam Turbine Design †

Abstract

1. Introduction

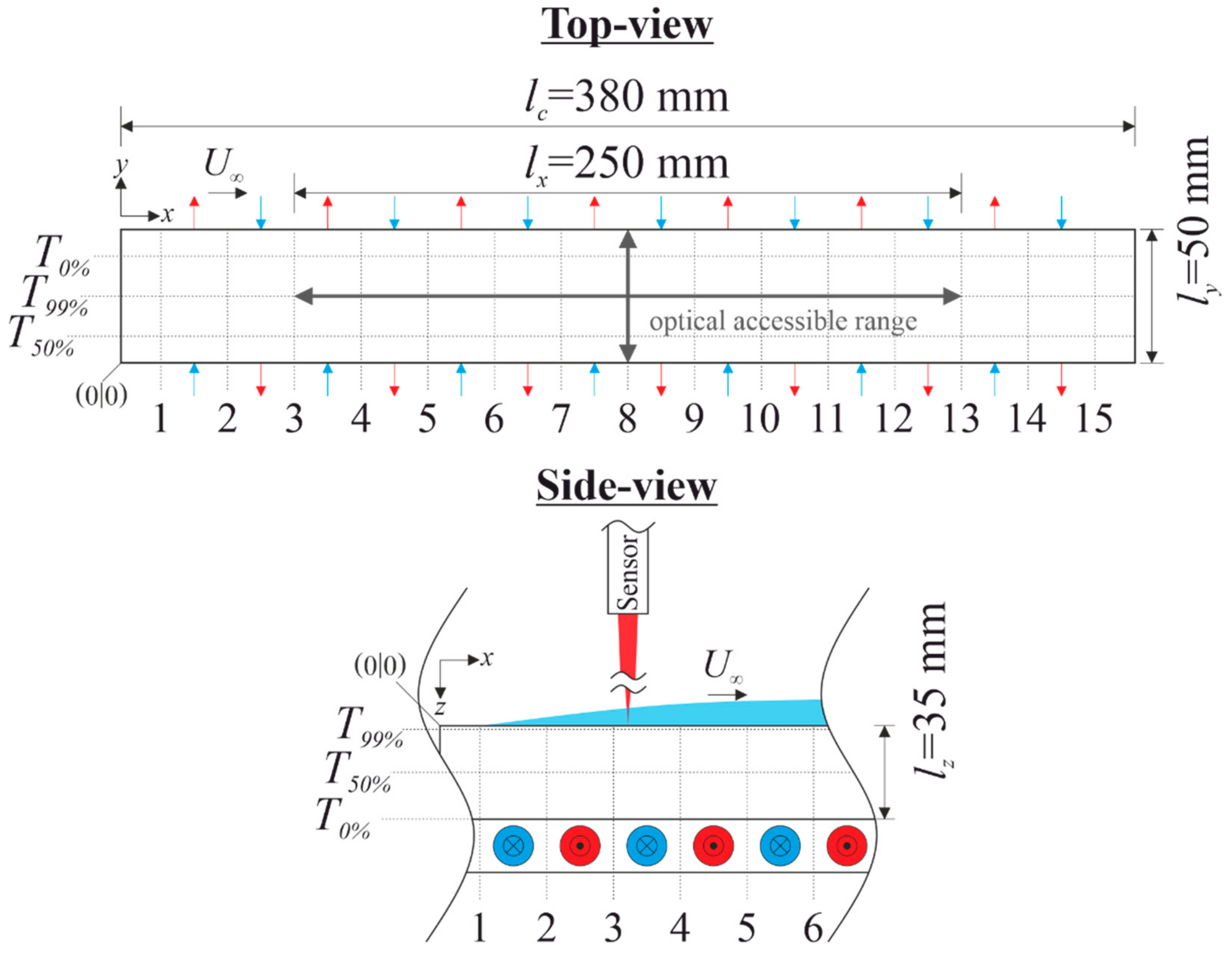

2. Analytical Model

3. Experimental Investigation

4. Experimental Results and Inaccuracy Consideration

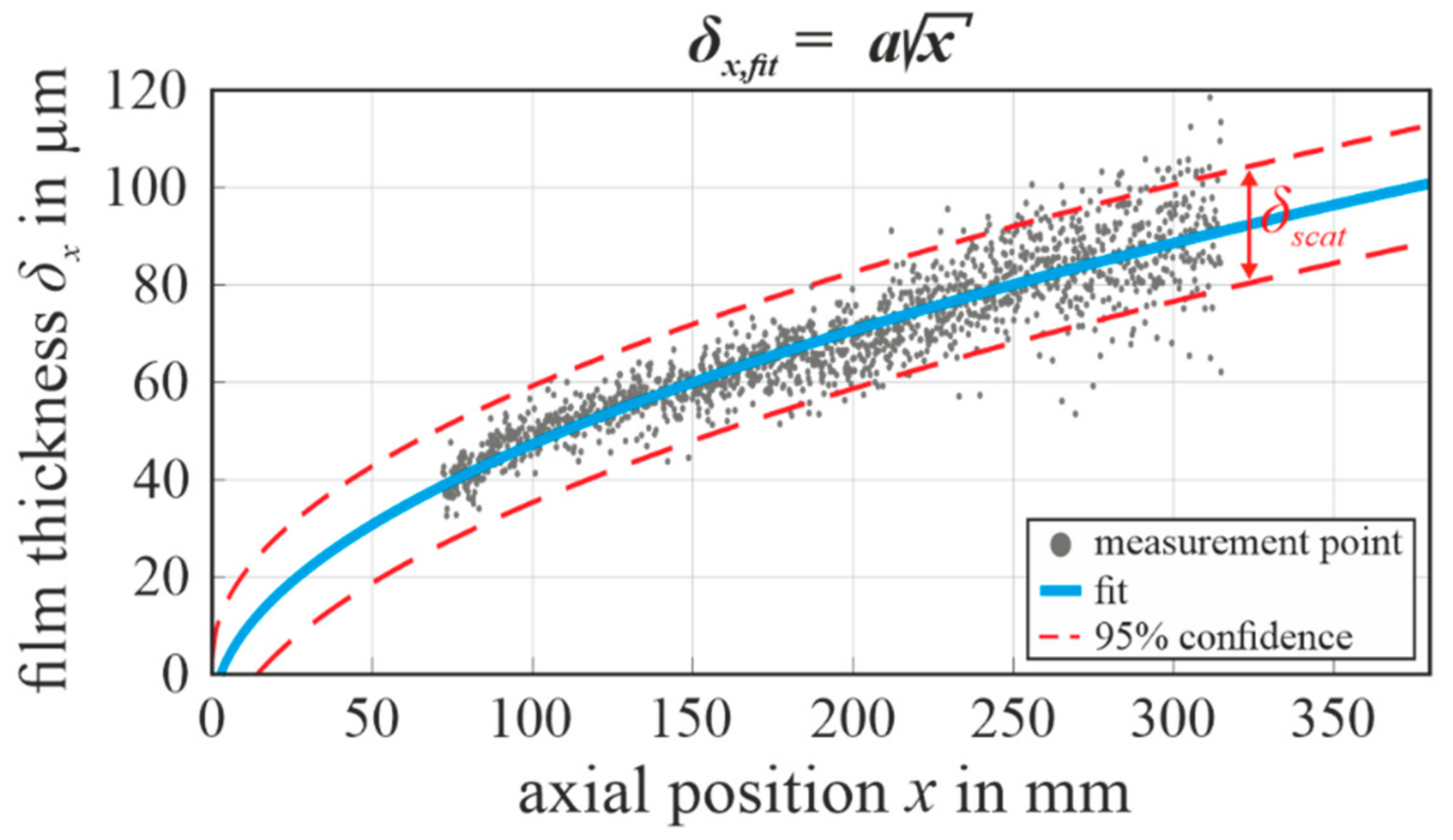

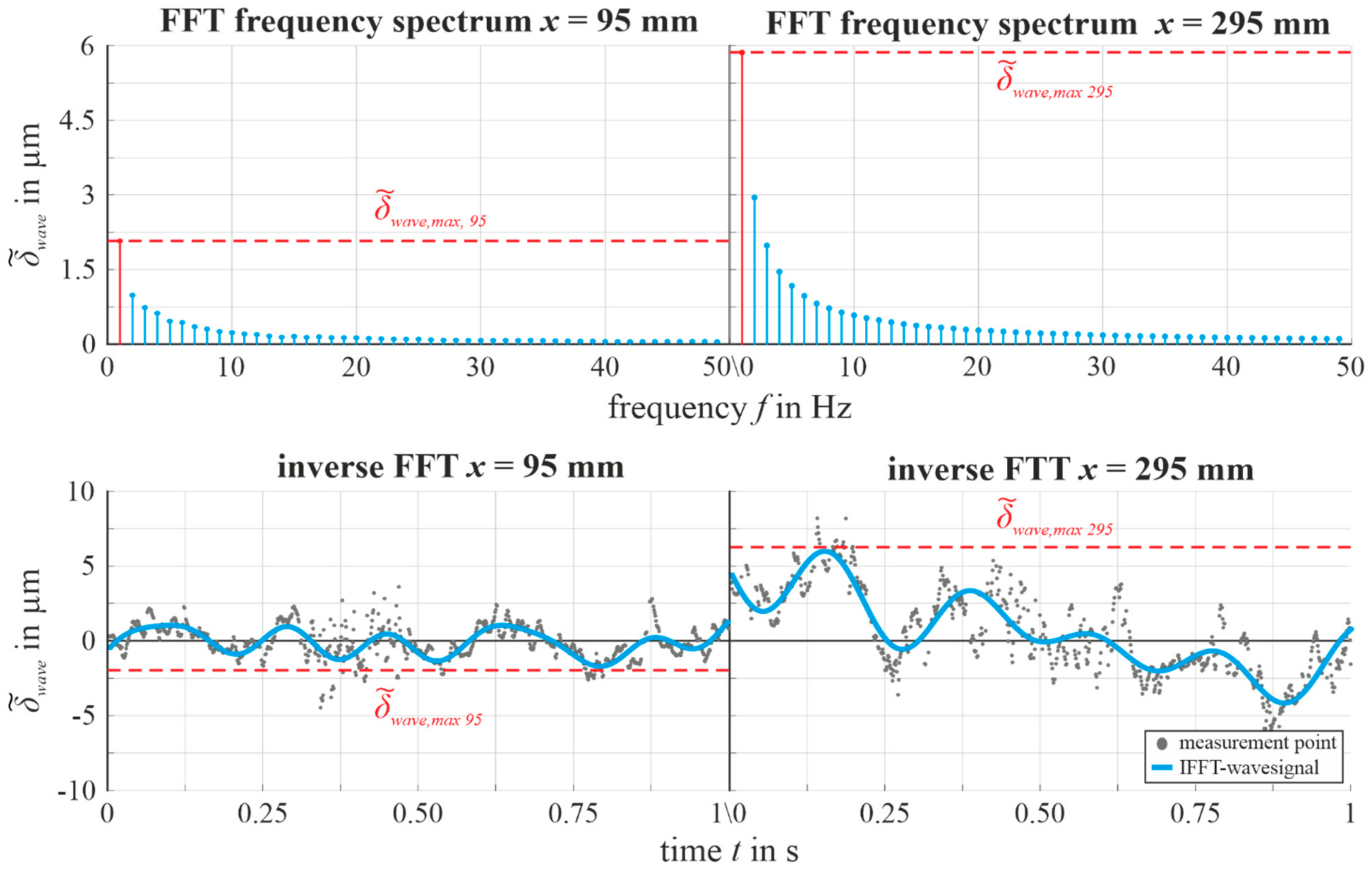

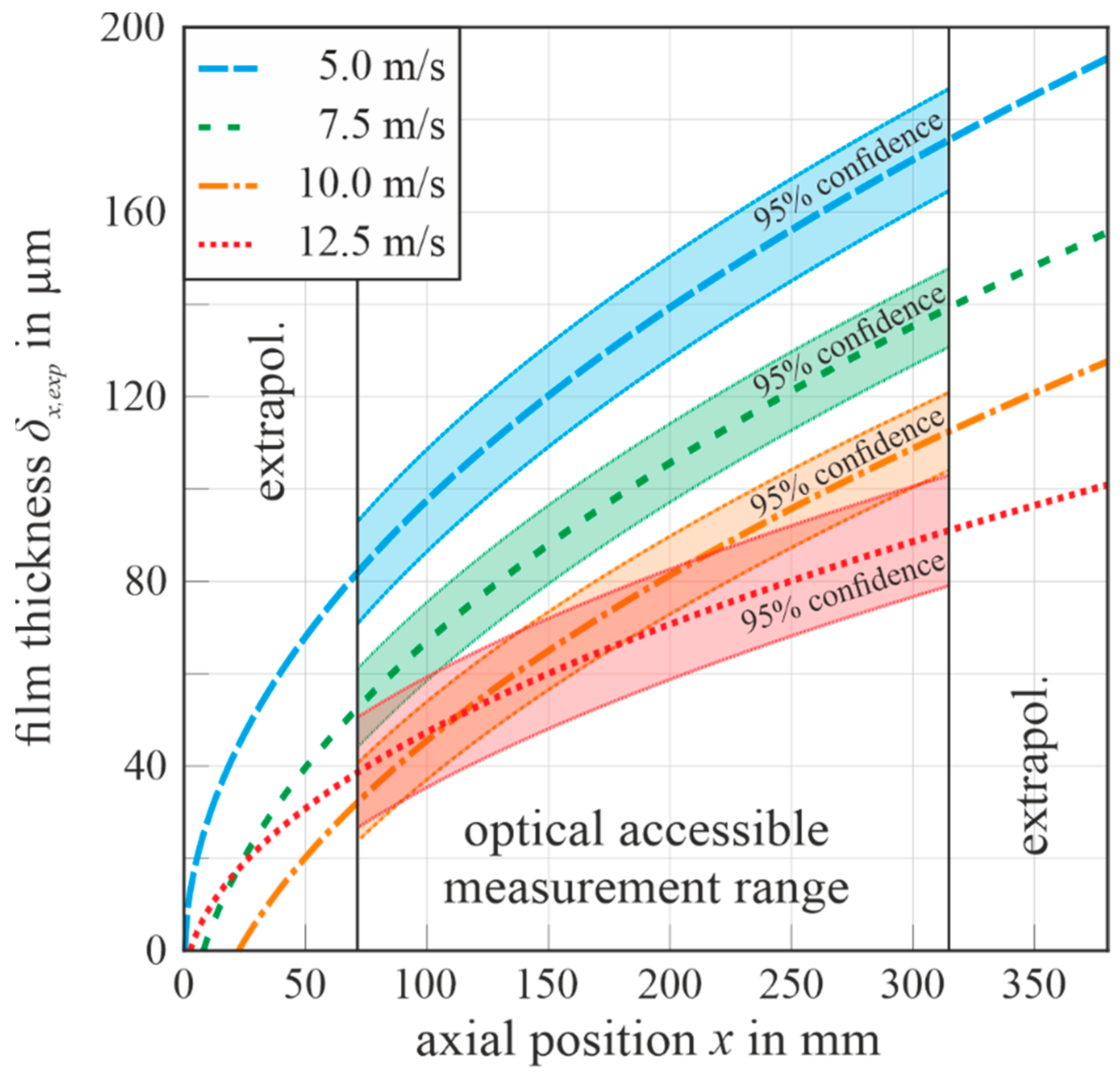

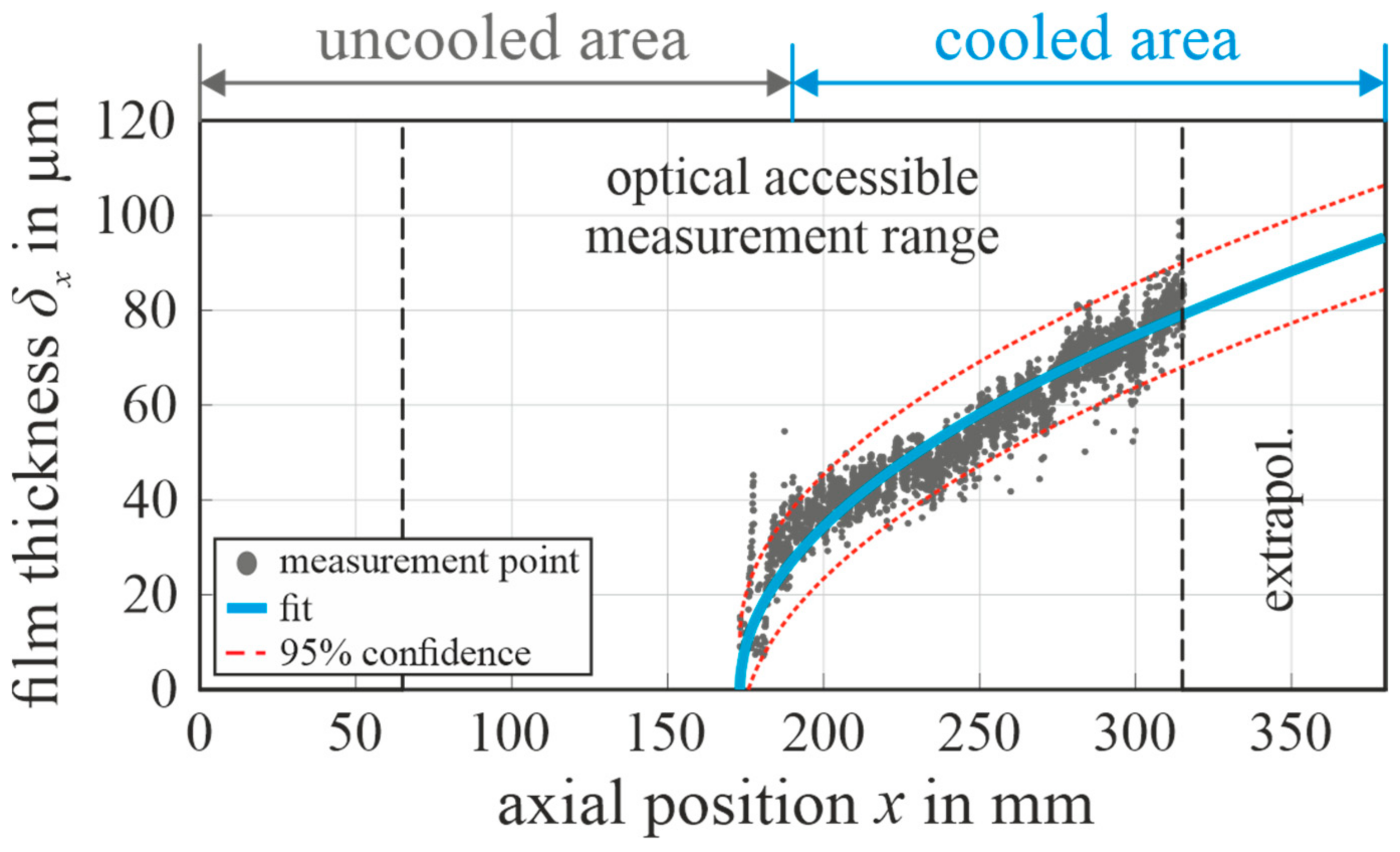

4.1. Liquid Film Thickness

4.2. Heat Transfer Coefficient

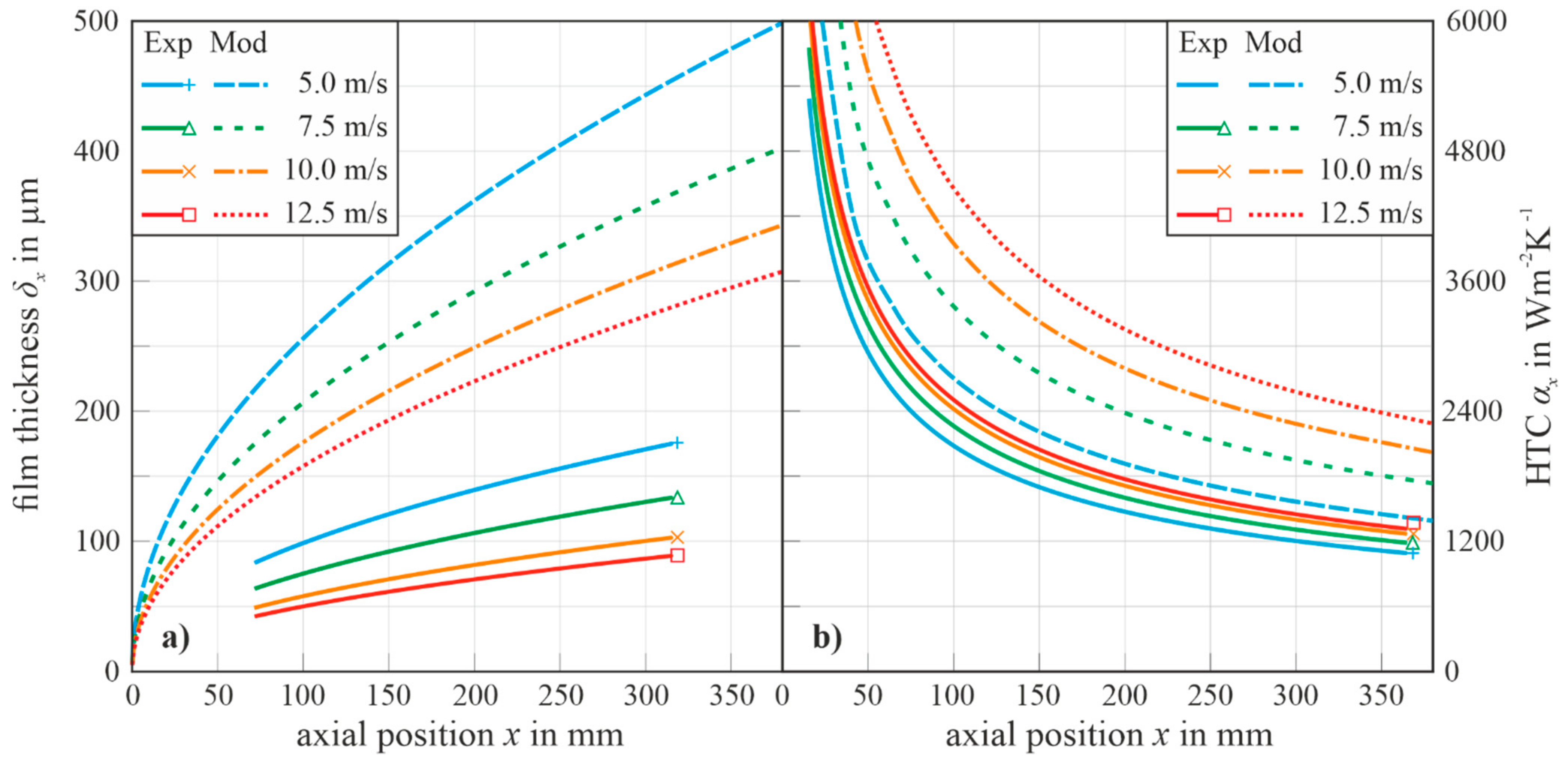

5. Model Validation

6. Conclusions and Outlook

- increases as a square root-function of the progressing overflow position for all velocities.

- The decrease in leads to an increase in the .

- Regarding , the model overestimates the thickness values regarding factor 2.3 compared to the experimental results due to the deferred steam temperature condition between the model and experiment.

- shows a regressive decline depending on an increasing axial position, .

- An evident inverse relation between and can be spatially observed. Additionally, both quantities are a function of .

- The axial gradient of is predicted to be higher than the experimental results.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| area | Reynolds number | ||||

| specific heat at const. pressure | steam temperature | ||||

| enthalpy | steam velocity | ||||

| mass flow rate | axial position | ||||

| Nusselt number | heat transfer coefficient | ||||

| length | film thickness | ||||

| steam pressure | similarity variable | ||||

| Prandtl number | thermal conductivity | ||||

| heat flux density | dynamic viscosity | ||||

| heat flux/cooling capacity | kinematic viscosity | ||||

| Koh coefficient | density | ||||

| correlation coefficient | shear stress | ||||

| average roughness value |

Indices

| steam flow conditions | scattering | ||

| cooling plate | wavelet | ||

| error/inaccuracy | wall | ||

| evaporation | direction x—horizontal parallel to flow | ||

| experimental | direction y—horizontal orthogonal to flow | ||

| gaseous | direction z—vertical orthogonal to flow | ||

| liquid | Pos. at meas. plate height | ||

| maximum | Pos. at meas. plate height | ||

| middle | Pos. at below meas. surface | ||

| minimum | dimensionless | ||

| model | amplitude | ||

| saturation | average |

References

- Cess, R.D. Laminar-film condensation on a flat plate in the absence of a body force. Z. Angew. Math. Phys. 1960, 11, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, J. Film condensation in a forced-convection boundary-layer flow. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1962, 5, 941–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.; Narain, A.; Mitra, S. Forced Flow of Vapor Condensing Over a Horizontal Plate (Problem of Cess and Koh): Steady and Unsteady Solutions of the Full 2D Problem. J. Heat Transf. 2010, 132, 101502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusselt, W. Die Oberflächenkondensation des Wasserdampfes. VDI-Zs 1916, 60, 541–546. [Google Scholar]

- Narain, A.; Liang, Q.; Yu, G.; Wang, X. Direct Computational Simulations for Internal Condensing Flows and Results on Attainability/Stability of Steady Solutions, Their Intrinsic Waviness and Their Noise Sensitivity. J. Appl. Mech. 2004, 71, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Phan, L.; Narain, A. Nonlinear Stability of the Classical Nusselt Problem of Film Condensation and Wave Effects. J. Appl. Mech. 2006, 74, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, E.M.; Gregg, J.L. A Boundary-Layer Treatment of Laminar-Film Condensation. J. Heat Transf. 1959, 81, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapp, F.F.; Schuster, S.; Hecker, S.; Brillert, D. The Multi-Phase Flow Test Facility “EMMA” to Investigate Local Heat Transfer Coefficients and Liquid Water Films at Wet Steam Conditions [GT2020-16307]. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2020, London, UK, 22–26 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Precitec Optronik GmbH. Overview Interferometric Point Sensors—CHRocodile 2 LR; Gaggenau: Bad Rotenfels, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- DIN–German Institute for Standardization. Material Numbers–Part 4: System of the Principal Groups 2 and 3: Non-Ferrous Metals; DIN EN 17007-4; Beuth Verlag GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Batz + Burgel GmbH & Co. KG Material Data Sheet: EN AW–2007 (AlCu4PBMgMN- 3.1645); Batz + Burgel GmbH & Co.: Friedberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- DIN–German Institute for Standardization. Designation Systems for Steels–Part 2: Numerical System; DIN EN 10027; Beuth Verlag GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- DEW–Deutsche Edelstahlwerke, Specialty Steel GmbH & Co. KG. Technical Data Sheet, X6CrNiMoTi17-12-2, 1.4571; DEW–Deutsche Edelstahlwerke, Specialty Steel GmbH & Co. KG: Witten, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Diller, T.E. Advances in Heat Flux Measurements. Adv. Heat Transf. 1993, 23, 279–368. [Google Scholar]

- Lapp, F.F.; Schuster, S.; Hecker, S.; Brillert, D. Experimental validation of an analytical condensation model for the improvement of steam turbine design regarding flexibility requirements. In Proceedings of the 14th European Conference on Turbomachinery Fluid Dynamics & Thermodynamics, ETC2020-562, Gdansk, Poland, 12–16 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-ND) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lapp, F.F.; Schuster, S.; Hecker, S.; Brillert, D. Experimental Validation of an Analytical Condensation Model for Application in Steam Turbine Design. Int. J. Turbomach. Propuls. Power 2022, 7, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijtpp7010009

Lapp FF, Schuster S, Hecker S, Brillert D. Experimental Validation of an Analytical Condensation Model for Application in Steam Turbine Design. International Journal of Turbomachinery, Propulsion and Power. 2022; 7(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijtpp7010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleLapp, Florian Felix, Sebastian Schuster, Simon Hecker, and Dieter Brillert. 2022. "Experimental Validation of an Analytical Condensation Model for Application in Steam Turbine Design" International Journal of Turbomachinery, Propulsion and Power 7, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijtpp7010009

APA StyleLapp, F. F., Schuster, S., Hecker, S., & Brillert, D. (2022). Experimental Validation of an Analytical Condensation Model for Application in Steam Turbine Design. International Journal of Turbomachinery, Propulsion and Power, 7(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijtpp7010009