Abstract

Background: Our understanding about knowledge, attitudes and perceptions (KAP) of immigrants regarding human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is poor. We present the first systematic review on KAP of immigrant parents towards HPV vaccine offered to their children. Methods: Major bio-medical databases (Medline, Embase, Scopus and PsycINFO) were searched using a combination of keyword and database-specific terms. Following identification of studies, data were extracted, checked for accuracy, and synthesised. Quality of the studies was assessed using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale and the Joanna Briggs Institute Qualitative Assessment tool. Results: A total of 311 titles were screened against eligibility criteria; after excluding 292 titles/full texts, 19 studies were included. The included studies contained data on 2206 adults. Participants’ knowledge was explored in 16 studies and ranged from none to limited knowledge. Attitudes about HPV vaccination were assessed in 13 studies and were mixed: four reported negative attitudes fearing it would encourage sexual activity; however, this attitude often changed once parents were given vaccine information. Perceptions were reported in 10 studies; most had misconceptions and concerns regarding HPV vaccination mostly influenced by cultural values. Conclusion: The knowledge of HPV-related diseases and its vaccine among immigrant parents in this study was generally low and often had negative attitude or perception. A well-designed HPV vaccine health educational program on safety and efficacy of HPV vaccination targeting immigrant parents is recommended.

1. Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is a sexually transmitted disease and both women and men are rapidly exposed to it after the onset of sexual intercourse [1,2]. Oncogenic HPV can cause cervical, anogenital, head and neck cancers [3,4].

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer found in women and the third most frequent cause of death with approximately 570,000 cases and 311,000 deaths in 2018 worldwide [5,6]. In developed countries nearly half of the cervical cancer cases are diagnosed in women aged less than 50 years old [6,7]. Rates of HPV infection vary greatly between geographic regions and population groups. In developed countries, cervical cancer has been declining for many years largely due to the cervical cytology screening programme which is now being replaced by HPV screening. However, cervical cancer is increasing in developing countries where nationwide cervical cancer screening is currently unavailable. It is the second most common cancer in countries with a lower human development index ranking and is the most common cancer in about 28 countries [6,8]. The high-risk types, HPV 16 and HPV 18, cause 70% of all invasive cervical cancers and HPV types: 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58 together can cause 95% of cervical cancers.

HPV vaccination is the most effective method of preventing HPV infection [9]. The immunity gained via HPV vaccination is mainly responsible for the reduction in HPV infection and related cancers [10]. The main goal of this vaccination is to avoid persistent infections that may progress to an invasive carcinoma [10,11]. HPV vaccine is safe, well tolerated and has the potential to significantly reduce the incidence of HPV-associated precancerous lesions [12,13]. It can also effectively protect against certain HPV types that can lead to genital warts. This vaccine is most beneficial if delivered prior to the commencement of sexual activity [13,14]. During the last 12 years, over 80 countries have introduced national HPV vaccination programs [15]. The United States of America (USA), Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom (UK) were among the first countries to introduce HPV vaccine into their national immunization programs (Table 1). All countries programs target young adolescent girls, with some countries also having programs for adolescent males [16]. Specific target age groups differ as do catch-up vaccination recommendations. The majority of countries are delivering vaccine through school-based programs, health centres or primary care providers [15]. National HPV vaccination programs of two or three dose schedules have demonstrated a dramatic impact on population level HPV prevalence, persistent HPV infection, genital warts, and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia [17]. The coverage of HPV vaccine achieved by the national programs has been highly variable within the countries [13]. During the past ten years, since HPV vaccine was licensed, there has been an increase in immigrants from different cultures and languages travelling to the Western countries. Most of the immigrants originate from socio-economically underprivileged countries [17,18], and do not have a nationally funded HPV vaccination program (Table 1); therefore, it is reasonable to believe that most immigrants do not have a background knowledge about HPV vaccination.

Table 1.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination programs in several countries that receive high numbers of immigrants from developing countries.

Knowledge and understanding of HPV infection and HPV vaccine are important factors in decision-making about disseminating the vaccine [13]. Since the licensure of HPV vaccine in 2006, research regarding the uptake of HPV vaccine among ethnic minorities, immigrants and refugees, has been limited [18,19]. This is attributed to factors such as language barrier and cultural differences, legal issues, religion, education, lack of specialized migrant health services and lack of awareness among migrants of their rights [20]. To our knowledge, there is no systematic study on immigrant parents’ knowledge, attitudes and perceptions (KAP) towards HPV vaccination. This study aims to address this research gap by systematically synthesising published data on immigrant parents’ KAP towards HPV disease and vaccination offered to their children to inform future efforts to increase HPV vaccine coverage.

2. Materials and Methods

Literature searches were performed using OVID Medline (1946–April 2019), OVID Embase Classic (1947–April 2019), PsycINFO (1806–May 2019) and SCOPUS (1945–May 2019). The searches used a combination of data base-controlled vocabulary terms and text word terms. These included “Papillomavirus vaccines”, “Human Papillomavirus vaccine”, “knowledge, attitudes, perceptions”, “emigrants”, “immigrants”, “population groups”, “ethnic groups”, “refugees”, “mothers”, “fathers” and “parents”. Searches were conducted from 2007 to 2019. The final search was conducted on 1 May 2019. No language or date restrictions were applied. The OVID Medline search strategy used is available upon application to authors. We additionally searched the reference lists of review articles to identify original research articles describing knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of HPV vaccine among immigrant parents.

For inclusion in this review, papers needed to discuss knowledge or attitudes or perceptions of immigrant parents (defined as parents who have been permanently living in a foreign country along with their children) and/or primary immigrant caregivers towards HPV vaccine. Papers were excluded if they did not include the views of parents or only discussed other childhood vaccines. Perception was defined as how parents interpreted/perceived HPV vaccine in light of their life experiences, and attitude was defined as their reactions to those perceptions. After screening the titles, full texts were retrieved and reviewed, and data were extracted in an Excel sheet by the first author. The data collection form included the author, year, country of study, method, population, result of the study. Another author (HR) checked data abstraction and any discrepancy was resolved through discussion then data were synthesised. The quality of included studies was assessed by Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp and by Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews Checklist for Qualitative Research https://joannabriggs.org/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Qualitative_Research2017_0.pdf.

3. Results

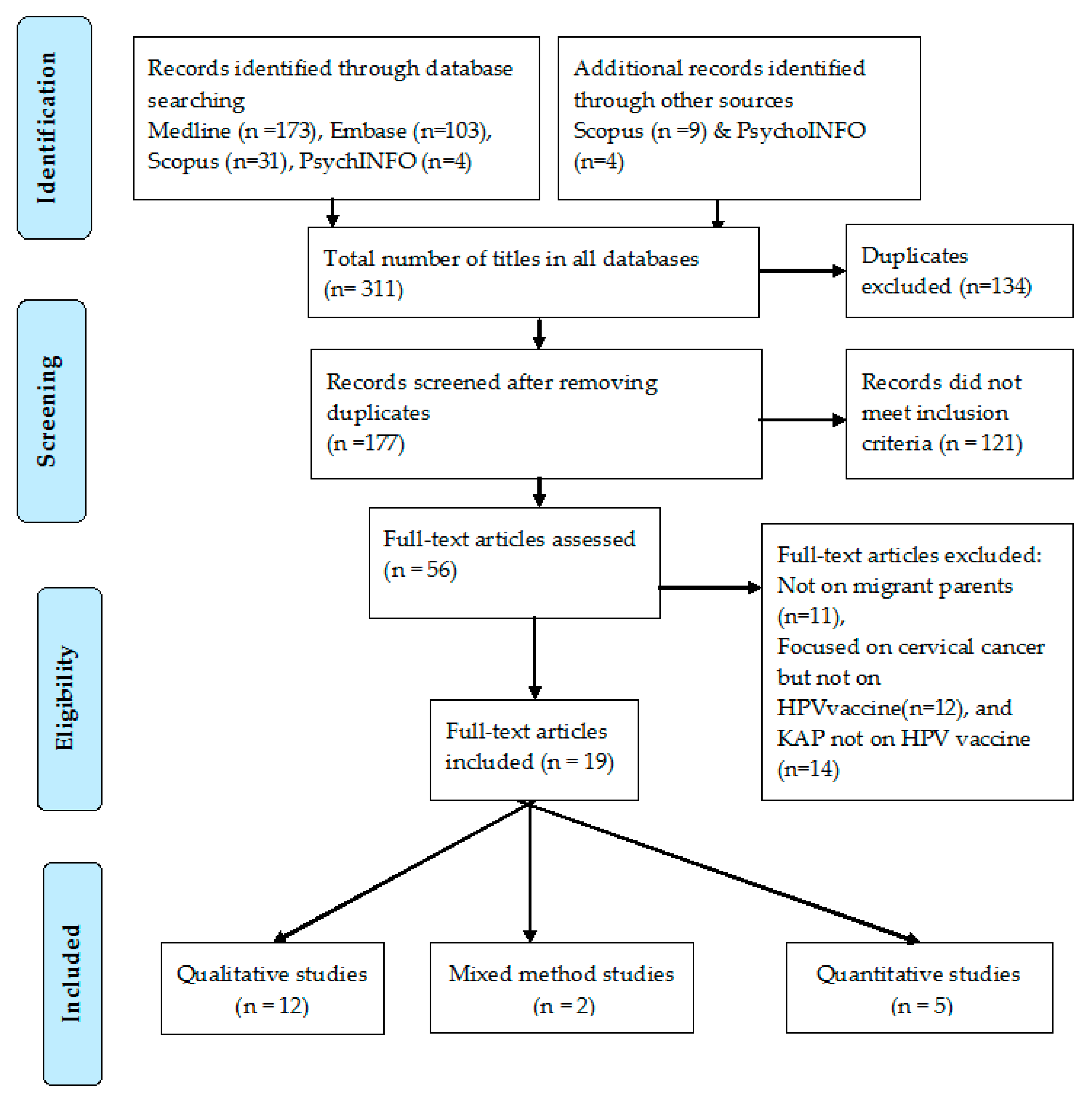

In this systematic review, 311 titles from four databases were retrieved in total. There were 134 duplicates leaving 177 records to be screened. Of 177 titles, 121 were excluded for not meeting inclusion criteria. The full texts of the remaining 56 titles were assessed. Of these 36 studies were determined to be out of scope of this systematic review and excluded with reasons, the remaining 19 articles met the eligibility criteria of the systematic review as shown in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1). There were 12 qualitative studies and five quantitative studies and two mixed method studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the systematic review.

Total number of participants in all included studies was 2206 (M = 74, F = 1976 in addition to 156 parents with gender unclassified) with a male to female ratio of 1:27, where data were provided. Where age of interviewees was mentioned, the range varied from 18 to 66 years. Twelve studies were conducted in the USA, three in the UK, one in the Netherlands, one in Denmark, one in Sweden, and one in Puerto Rico. Six studies were conducted in community organizations including faith-based centres like churches and mosques [21,22,23,24,25,26], eight in health and social service agencies [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34], two in schools and/or community groups [35,36], another two in social clubs [37,38], and one in a household [39].

Of the 19 studies, 16 reported on knowledge of the immigrant parents about HPV vaccine (Table 2), 13 reported their attitudes (Table 3) and 10 recorded perceptions (as defined by study author) towards HPV vaccine (Table 4). Four studies reported knowledge and attitudes [21,27,30,37] and one reported knowledge and perceptions [26], seven studies reported on all three outcomes (knowledge, attitude and perceptions) [22,23,29,35,36,38,39].

Table 2.

Studies reporting knowledge of immigrants about HPV vaccine (16 articles).

Table 3.

Studies reporting attitudes of immigrants about HPV vaccine (13 articles).

Table 4.

Studies reporting perceptions of immigrants about HPV vaccine (12 articles).

All included studies discussed the KAP of immigrant populations. If the study author(s) used the term “ethnic minority” to represent, we have similarly reported this term in the result tables.

For knowledge, the level of parents’ knowledge about HPV disease and HPV vaccine ranged from no knowledge in 11 studies [21,22,23,24,26,27,29,33,35,37,39] to limited knowledge regarding HPV and HPV vaccine, as they heard about the vaccine but they did not know HPV vaccine’s purpose, the eligibility requirements for the vaccine, and the vaccine’s dosing/schedule requirements in three studies. Five studies revealed that some participants had not heard of HPV disease or HPV vaccine [27,33,35,39]. There were four studies that reported participants had no prior knowledge of HPV as a sexually transmitted disease or as a cause of cancer [25,30,32]. In four studies, participants described a lack of information and knowledge about the purpose of HPV vaccination, and HPV transmission [21,29,37]. Two studies found participants had limited knowledge regarding the relation between sexual transmission of HPV and cervical cancer [22,36] (Table 2).

In regards to attitudes towards HPV disease and HPV vaccine (Table 3), a number of non-vaccinating ethnic minority parents had negative attitudes to HPV vaccination thinking it would encourage unsafe sexual practices and promiscuity [22,30,35]. However, three studies showed that once parents were informed about the vaccine during the focus groups, they became keen to vaccinate their children [34,36,37]. Non-vaccinating and partially vaccinating parents from various ethnic backgrounds expressed concerns about potential side effects [35]; religious values and cultural norms also influenced vaccine decision-making [28,29], and a majority of participants (regardless of vaccination status) had a more positive attitude towards vaccination when they received information about HPV vaccine (Table 3).

Participants had misperceptions about HPV vaccine. The main reasons for declining HPV vaccine were their religious belief and culture; in particular, their belief that abstinence from sex before marriage would provide protection from disease [22,31,36]. Awareness of a health intervention is recognised as necessary but not sufficient condition for performing a health behaviour. As women become aware of HPV vaccine, they may have additional questions or concerns that may function as barriers to getting their daughters vaccinated [31] (Table 4).

Most studies were of generally good quality. When scored against the checklist used, ten qualitative studies received eight out of a possible 10 points, and one 10 of 10 [37]. Four of the eight quantitative observational studies scored eight of nine points, and the other scored seven of nine points (Table 5).

Table 5.

Quality assessment of the included studies.

4. Discussion

This systematic review identifies gaps in knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about HPV infection and its vaccine among immigrant parents in western countries. Our analyses indicate that although HPV vaccine has been in use for over a decade, information about this vaccine, and HPV infection in general, and its relation to cancer in particular, does not appear to have been well disseminated to immigrant parents. Most participants in 12 included studies had no knowledge about HPV vaccine (Table 2), one third of participants in two studies reported receiving no information about HPV vaccine, [27,35]. All participants in one study have not even heard of the vaccine [29]. This systematic review showed participants had both negative and positive attitudes towards HPV vaccination, and most participants had misconceptions about HPV vaccination.

In concordance with our systematic review findings, semi-structured interviews conducted with non-parent immigrant participants also showed limited knowledge about HPV infection its vaccine. For example, a study conducted in a Western Canadian province, found participants had limited knowledge about HPV. Most women perceived their risk of HPV to be low but reported willingness to receive the vaccine when recommended by their doctors [19]. Similarly [35], in Italy, knowledge and attitude toward HPV infection and vaccination among non-parent immigrants and refugees was low [40]. In Sweden, adolescent school students were interviewed in relation to their beliefs and knowledge about HPV prevention: HPV vaccination was found to be associated with ethnicity and the mothers’ education level; i.e., girls with a non-European background, including those of Arabic background, and with a less educated mother were less likely to have received the vaccine. Vaccinated girls perceived HPV infection as more severe, had more insight into women’s susceptibility to the infection, perceived more benefits of the vaccine as protection against cervical cancer and had a higher intention to engage in HPV-preventive behaviour [41].

Furthermore, another systematic review that explored knowledge and attitudes of Iranian people towards HPV vaccination found that the overall knowledge and awareness about HPV vaccination was low; however, their attitude toward HPV vaccination was positive and strong [42]. This corroborates the findings from three studies included in our systematic review that showed positive attitude towards HPV vaccines once parents were informed about it during focus groups. [34,36]. This could possibly explain why the negative attitude to HPV vaccination found in most of the studies included in our systematic review was stemmed from poor knowledge/misconceptions and may change after providing the right information.

Unlike the immigrants, mainstream populations of USA had better knowledge and more positive attitudes toward HPV vaccine. A quantitative study conducted in Southern California compared knowledge and acceptability between US-born African Americans and African immigrants, and between US-born Latinas and Latina immigrants. African and South American immigrants were less likely to know where they can get/refer for HPV vaccine and less likely to have heard about HPV vaccine than South Americans and US-born Africans [43]. Similarly, a study in Denmark found that refugee girls, mainly from Muslim countries, had significantly lower HPV immunization uptake compared to Danish born girls, indicating that refugee girls may face challenges to access and use of immunization services [44].

A study in 2018 indicated that the increase in refusal and hesitancy of Muslim parents to accept childhood vaccination was identified as one of the contributing factors in the increase of vaccine-preventable diseases cases in several countries such as Afghanistan, Malaysia and Pakistan. News disseminated via some social media outlets claiming that the vaccine has been designed to weaken Muslims, reinforced the suspicion and mistrust of vaccines by parents [45]. A qualitative study of the views of young non-parent Somali men and women in the USA demonstrated that the participants had limited knowledge about the vaccination and had suspicions concerning the effectiveness or value of immunization, with most participants stating that the Somali community was mostly Muslim and did not engage in sexual activity before marriage [46]. A cross-sectional study included in our systematic review conducted to evaluate awareness of women from major UK ethnic minority groups (Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Caribbean, African and Chinese women) toward HPV vaccination identified that those from non-Christian religions were less accepting of the vaccine (17–34%). The study concluded that some cultural barriers could be addressed by tailored information provided to ethnic minority groups [47].

Attitudes toward HPV vaccine are important in HPV vaccine uptake. Our systematic review revealed certain attitude-related barriers to vaccine acceptability for adolescents, particularly vaccine hesitancy among some mothers. A qualitative study reported that Latin American immigrant mothers of adolescent daughters expressed more hesitancy regarding adolescent vaccines compared to childhood vaccines expressed an increased sense of belief in their ability to determine what is best for their children [48]. In contrast to the negative attitudes of immigrant parents as found in most of the included studies in our systematic review, most mainstream non-immigrant women had positive attitudes about receiving an HPV vaccine and high intention to receive the vaccine both for themselves and their daughters [49]. Variables associated with intention to vaccinate included knowledge, personal beliefs, confidence that others would approve of vaccination, and having a higher number of sexual partners [49]. However, negative or variable attitudes of parents to vaccinate their children have been reported in a systematic review involving Turkish population [50]. The systematic review showed that between 14.4% and 68.0% of Turkish parents were willing to have their daughters vaccinated with HPV vaccine and between 11.0% and 62.0% parents were willing to have their sons vaccinated [50], suggesting a negative attitude may not be just a phenomenon of immigrants, many non-immigrants in their own countries too may have negative attitudes towards HPV vaccination. However, since this attitude appeared amenable to change in our systematic review, innovative simple interventions may improve attitudes to HPV vaccination. For instance, a higher vaccination rate was achieved at three clinics in Texas, USA among children and adolescents through the involvement of patient navigators. The patient navigators met the parents of unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated children while they waited for their children’s health providers in private clinic rooms to confirm the need for additional HPV vaccine doses. Parents of children who needed ≥ 1 dose were offered personal counselling and given handouts in English or Spanish on HPV vaccine. Following such counselling about 67% parents got their children vaccinated either immediately or at a follow-up visit soon thereafter, indicating that providing counselling in a clinic setting can improve vaccination acceptance [51].

To our knowledge this is the first systematically conducted review of HPV vaccination knowledge, attitudes and perceptions among immigrants. Most included studies were of acceptable quality. We failed to identify research regarding knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of immigrant parents towards HPV vaccine in developing countries. Some papers did not clearly distinguish between attitudes and perceptions as outcomes. However, these studies suggest that tailored educational programs to improve KAP on HPV vaccine among immigrant parents may be a valuable intervention for HPV vaccination uptake.

5. Conclusions

Parental knowledge and attitudes towards HPV vaccine have been examined in many recent studies and lower uptake of HPV vaccine among immigrants, refugees and ethnic minorities has been documented. Our results support the pressing need to develop an intervention aimed to improve HPV vaccination uptake in these populations. More research is needed in the design and evaluation of tailored educational resources for ethnic minority groups, particularly in the framework of the vaccination programme.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.N., H.R. and S.R.S.; methodology, F.N., C.K. and H.R.; software, F.N.; validation, F.N., M.T., C.K., H.R., R.B. and S.R.S.; formal analysis, F.N., H.R. and C.K.; investigation, F.N., H.R. and C.K.; resources, F.N., H.R., C.K. and S.R.S.; data curation, F.N., H.R., and S.R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, F.N., H.R. and C.K.; writing—review and editing, F.N., H.R., C.K., M.T., R.B. and S.R.S.; visualization, F.N., H.R. and C.K.; supervision, F.N., M.T., C.K., H.R., R.B. and S.R.S.; project administration, S.R.S.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Trish Bennett, Manager the Children’s Hospital at Westmead Library for assistance with the literature searches.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Martins, T.R.; Mendes de Oliveira, C.; Rosa, L.R.; de Campos Centrone, C.; Rodrigues, C.L.; Villa, L.L.; Levi, J.E. HPV genotype distribution in Brazilian women with and without cervical lesions: Correlation to cytological data. Virol. J. 2016, 13, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocjan, B.J.; Bzhalava, D.; Forslund, O.; Dillner, J.; Poljak, M. Molecular methods for identification and characterization of novel papillomaviruses. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, H.; Donovan, B.; Wand, H.; Read, T.R.; Regan, D.G.; Grulich, A.E.; Fairley, C.K.; Guy, R.J. Genital warts in young Australians five years into national human papillomavirus vaccination programme: National surveillance data. Bmj 2013, 346, f2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monsonego, J.; Bosch, F.X.; Coursaget, P.; Cox, J.T.; Franco, E.; Frazer, I.; Sankaranarayanan, R.; Schiller, J.; Singer, A.; Wright, T.C., Jr.; et al. Cervical cancer control, priorities and new directions. Int. J. Cancer 2004, 108, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achampong, Y.; Kokka, F.; Doufekas, K.; Olaitan, A. Prevention of Cervical Cancer. J. Cancer Ther. 2018, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, F.X.; Burchell, A.N.; Schiffman, M.; Giuliano, A.R.; de Sanjose, S.; Bruni, L.; Tortolero-Luna, G.; Kjaer, S.K.; Munoz, N. Epidemiology and natural history of human papillomavirus infections and type-specific implications in cervical neoplasia. Vaccine 2008, 26 (Suppl. 10), K1-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Zulueta, M.; Alvarez-Paredes, L.; Rodriguez Diaz, J.C.; Paras-Bravo, P.; Andrada Becerra, M.E.; Rodriguez Ingelmo, J.M.; Ruiz Garcia, M.M.; Portilla, J.; Santibanez, M. Prevalence of high-risk HPV genotypes, categorised by their quadrivalent and nine-valent HPV vaccination coverage, and the genotype association with high-grade lesions. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotherton, J.M.; Gertig, D.M.; May, C.; Chappell, G.; Saville, M. HPV vaccine impact in Australian women: Ready for an HPV-based screening program. Med. J. Aust. 2016, 204, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cervantes, J.L.; Doan, A.H. Discrepancies in the evaluation of the safety of the human papillomavirus vaccine. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2018, 113, e180063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, S.M.; Paavonen, J.; Jaisamrarn, U.; Naud, P.; Salmeron, J.; Chow, S.N.; Apter, D.; Castellsague, X.; Teixeira, J.C.; Skinner, S.R.; et al. Prior human papillomavirus-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccination prevents recurrent high grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia after definitive surgical therapy: Post-hoc analysis from a randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 139, 2812–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garland, S.M.; Cornall, A.M.; Brotherton, J.M.L.; Wark, J.D.; Malloy, M.J.; Tabrizi, S.N. Final analysis of a study assessing genital human papillomavirus genoprevalence in young Australian women, following eight years of a national vaccination program. Vaccine 2018, 36, 3221–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brotherton, J.M.L.; Bloem, P.N. Population-based HPV vaccination programmes are safe and effective: 2017 update and the impetus for achieving better global coverage. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 47, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taberna, M.; Mena, M.; Pavon, M.A.; Alemany, L.; Gillison, M.L.; Mesia, R. Human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 2386–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, K.E.; LaMontagne, D.S.; Watson-Jones, D. Status of HPV vaccine introduction and barriers to country uptake. Vaccine 2018, 36, 4761–4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, V.Y.; Booy, R.; Skinner, R.; Edwards, K.M. The effect of exercise on vaccine-related pain, anxiety and fear during HPV vaccinations in adolescents. Vaccine 2018, 36, 3254–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, L.E.; Tsu, V.; Deeks, S.L.; Cubie, H.; Wang, S.A.; Vicari, A.S.; Brotherton, J.M. Human papillomavirus vaccine introduction—The first five years. Vaccine 2012, 30 (Suppl. 5), F139–F148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepka, D.; Bodson, J.; Lai, D.; Sanchez-Birkhead, A.C.; Davis, F.A.; Lee, D.; Tavake-Pasi, F.; Napia, E.; Villalta, J.; Mukundente, V.; et al. Diverse caregivers’ hpv vaccine-related awareness and knowledge. Ethn. Health 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McComb, E.; Ramsden, V.; Olatunbosun, O.; Williams-Roberts, H. Knowledge, Attitudes and Barriers to Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine Uptake Among an Immigrant and Refugee Catch-Up Group in a Western Canadian Province. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2018, 20, 1424–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofters, A.K.; Vahabi, M.; Fardad, M.; Raza, A. Exploring the acceptability of human papillomavirus self-sampling among Muslim immigrant women. Cancer Manag. Res. 2017, 9, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragones, A.; Genoff, M.; Gonzalez, C.; Shuk, E.; Gany, F. HPV Vaccine and Latino Immigrant Parents: If They Offer It, We Will Get It. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2016, 18, 1060–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, D.P.; Thomas, T.L. Cultural Values Influencing Immigrant Haitian Mothers’ Attitudes Toward Human Papillomavirus Vaccination for Daughters. J. Black Psychol. 2013, 39, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenfield, L.S.; Page, L.C.; Kay, M.; Li-Vollmer, M.; Breuner, C.C.; Duchin, J.S. Strategies for increasing adolescent immunizations in diverse ethnic communities. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, S47–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kepka, D.; Ding, Q.; Bodson, J.; Warner, E.L.; Mooney, K. Latino Parents’ Awareness and Receipt of the HPV Vaccine for Sons and Daughters in a State with Low Three-Dose Completion. J. Cancer Educ. 2015, 30, 808–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodson, J.; Warner, E.L.; Kepka, D. Moderate Awareness and Limited Knowledge Relating to Cervical Cancer, HPV, and the HPV Vaccine Among Hispanics/Latinos in Utah. Health Promot. Pract. 2016, 17, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque, J.S.; Raychowdhury, S.; Weaver, M. Health care provider challenges for reaching Hispanic immigrants with HPV vaccination in rural Georgia. Rural Remote Health 2012, 12, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn, B.A.; Tsui, J.; Singhal, R.; Sanchez, L.; Nonzee, N.J.; Chang, L.C.; Taylor, V.M.; Bastani, R. Factors associated with HPV awareness among mothers of low-income ethnic minority adolescent girls in Los Angeles. Vaccine 2015, 33, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albright, K.; Barnard, J.; O’Leary, S.T.; Lockhart, S.; Jimenez-Zambrano, A.; Stokley, S.; Dempsey, A.; Kempe, A. Noninitiation and Noncompletion of HPV Vaccine Among English- and Spanish-Speaking Parents of Adolescent Girls: A Qualitative Study. Acad. Pediatrics 2017, 17, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salad, J.; Verdonk, P.; de Boer, F.; Abma, T.A. “A Somali girl is Muslim and does not have premarital sex. Is vaccination really necessary?” A qualitative study into the perceptions of Somali women in the Netherlands about the prevention of cervical cancer. Intern 2015, 14, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.D.; De Jesus, M.; Mars, D.; Tom, L.; Cloutier, L.; Shelton, R.C. Decision-making about the HPV vaccine among ethnically diverse parents: Implications for health communications. J. Oncol. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, A.S.; Bruce, C.M.; Tiro, J.A. Understanding how mothers of adolescent girls obtain information about the human papillomavirus vaccine: Associations between mothers’ health beliefs, information seeking, and vaccination intentions in an ethnically diverse sample. J. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 926–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopfer, S.; Garcia, S.; Duong, H.T.; Russo, J.A.; Tanjasiri, S.P. A Narrative Engagement Framework to Understand HPV Vaccination Among Latina and Vietnamese Women in a Planned Parenthood Setting. Health Educ. Behav. 2017, 44, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colon-Lopez, V.; Quinones, V.; Del Toro-Mejias, L.M.; Conde-Toro, A.; Serra-Rivera, M.J.; Martinez, T.M.; Rodriguez, V.; Berdiel, L.; Villanueva, H. HPV Awareness and Vaccine Willingness Among Dominican Immigrant Parents Attending a Federal Qualified Health Clinic in Puerto Rico. J. Immigr. Minority Health 2015, 17, 1086–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, R.B.; Pierre-Joseph, N.; Marquez, C.; Iloka, S.; Clark, J.A. Parents’ opinions of mandatory human papillomavirus vaccination: Does ethnicity matter? Women’s Health Issues 2010, 20, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forster, A.S.; Rockliffe, L.; Marlow, L.A.V.; Bedford, H.; McBride, E.; Waller, J. Exploring human papillomavirus vaccination refusal among ethnic minorities in England: A comparative qualitative study. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 1278–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandahl, M.; Tyden, T.; Gottvall, M.; Westerling, R.; Oscarsson, M. Immigrant women’s experiences and views on the prevention of cervical cancer: A qualitative study. Health Expect. 2015, 18, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeraiq, L.; Nielsen, D.; Sodemann, M. Attitudes towards human papillomavirus vaccination among Arab ethnic minority in Denmark: A qualitative study. Scand. J. Public Health 2015, 43, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mupandawana, E.T.; Cross, R. Attitudes towards human papillomavirus vaccination among African parents in a city in the north of England: A qualitative study. Reprod Health 2016, 13, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlow, L.A.; Wardle, J.; Forster, A.S.; Waller, J. Ethnic differences in human papillomavirus awareness and vaccine acceptability. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2009, 63, 1010–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, F.; Gualdieri, L.; Santagati, G.; Angelillo, I.F. Knowledge and attitudes toward HPV infection and vaccination among immigrants and refugees in Italy. Vaccine 2018, 36, 7536–7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandahl, M.; Larsson, M.; Dalianis, T.; Stenhammar, C.; Tyden, T.; Westerling, R.; Neveus, T. Catch-up HPV vaccination status of adolescents in relation to socioeconomic factors, individual beliefs and sexual behaviour. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taebi, M.; Riazi, H.; Keshavarz, Z.; Afrakhteh, M. Knowledge and Attitude Toward Human Papillomavirus and HPV Vaccination in Iranian Population: A Systematic Review. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2019, 20, 1945–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashing, K.T.; Carrington, A.; Ragin, C.; Roach, V. Examining HPV- and HPV vaccine-related cognitions and acceptability among US-born and immigrant hispanics and US-born and immigrant non-Hispanic Blacks: A preliminary catchment area study. Cancer Causes Control 2017, 28, 1341–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moller, S.P.; Kristiansen, M.; Norredam, M. Human papillomavirus immunization uptake among girls with a refugee background compared with Danish-born girls: A national register-based cohort study. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2018, 27, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.; Lee, K.S.; Bukhsh, A.; Al-Worafi, Y.M.; Sarker, M.M.R.; Ming, L.C.; Khan, T.M. Outbreak of vaccine-preventable diseases in Muslim majority countries. J. Infect. Public Health 2018, 11, 153–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratt, R.; Njau, S.W.; Ndagire, C.; Chaisson, N.; Toor, S.; Ahmed, N.; Mohamed, S.; Dirks, J. “We are Muslims and these diseases don’t happen to us”: A qualitative study of the views of young Somali men and women concerning HPV immunization. Vaccine 2019, 37, 2043–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlow, L.A.; Wardle, J.; Waller, J. Attitudes to HPV vaccination among ethnic minority mothers in the UK: An exploratory qualitative study. Hum. Vaccines 2009, 5, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter, J.E.; Viana De, O.M.S.; Jimenez, L.; Avila, A.A.; Sutter, C.J.; Sutter, R. Vaccine-related attitudes and decision-making among uninsured, Latin American immigrant mothers of adolescent daughters: A qualitative study. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019, 15, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, J.A.; Rosenthal, S.L.; Hamann, T.; Bernstein, D.I. Attitudes about human papillomavirus vaccine in young women. Int. J. STD AIDS 2003, 14, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, S.; Akkaya, R.; Karasahin, K.E. Analysis of community-based researches related to knowledge, awareness, attitude and behaviors towards HPV and HPV vaccine published in Turkey: A systematic review. J. Turk. Ger. Gynecol. Assoc. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenson, A.B.; Rupp, R.; Dinehart, E.E.; Cofie, L.E.; Kuo, Y.F.; Hirth, J.M. Achieving high HPV vaccine completion rates in a pediatric clinic population. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019, 15, 1562–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).