A High Burden of Infectious Tuberculosis Cases Among Older Children and Young Adolescents of the Female Gender in Ethiopia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Settings

2.2. Interventions

2.3. Data Source

2.4. Data Quality

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

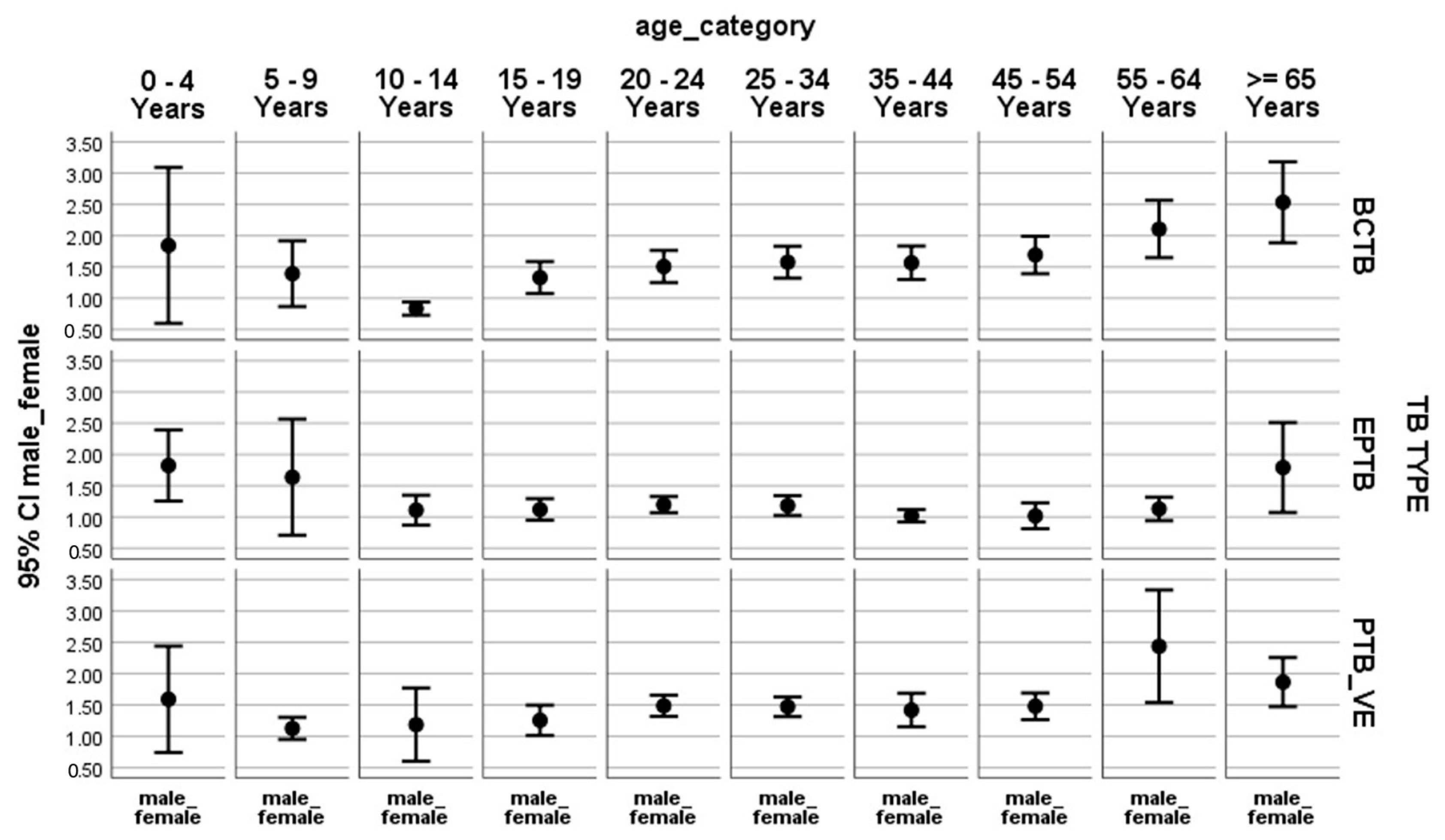

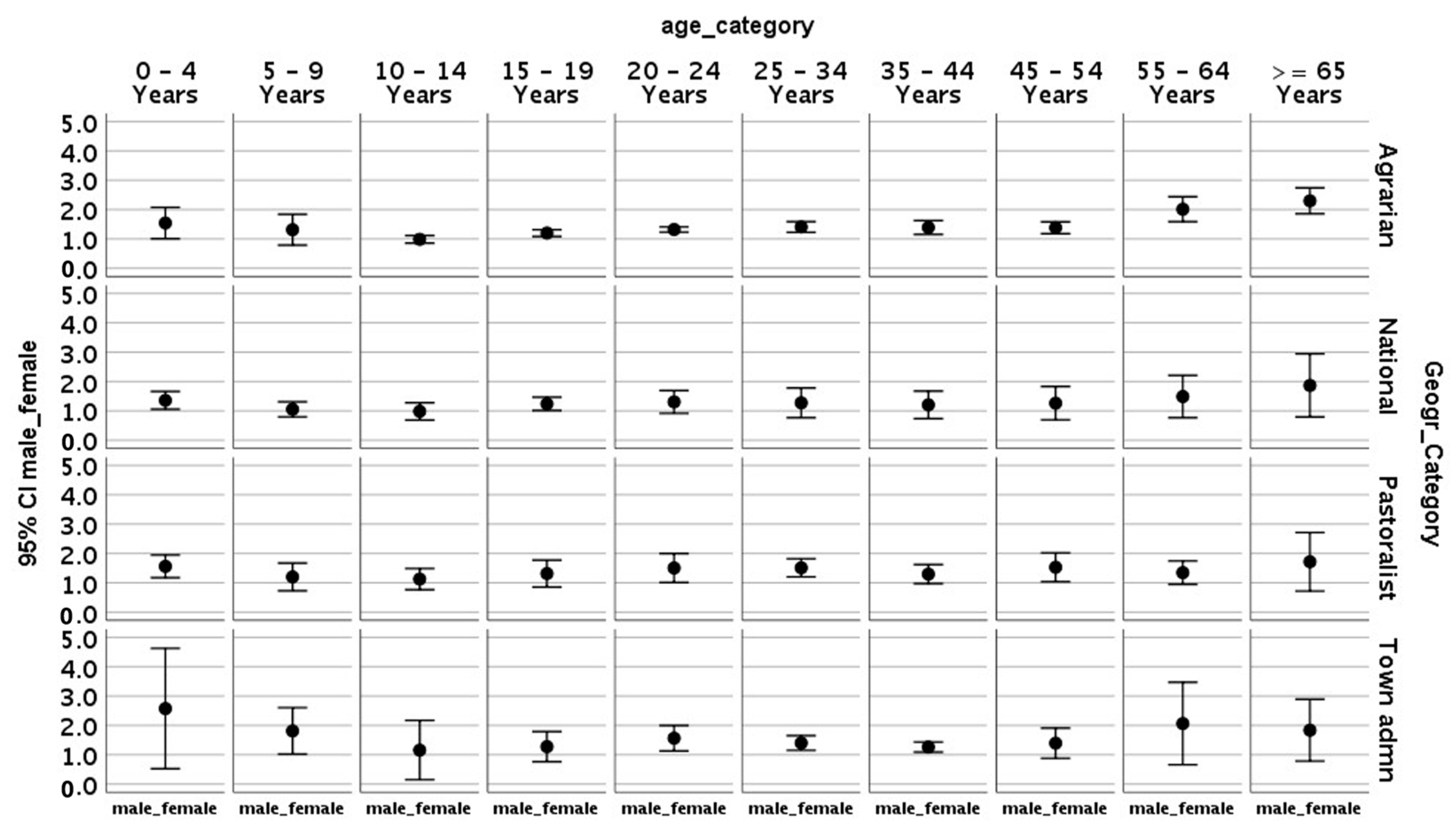

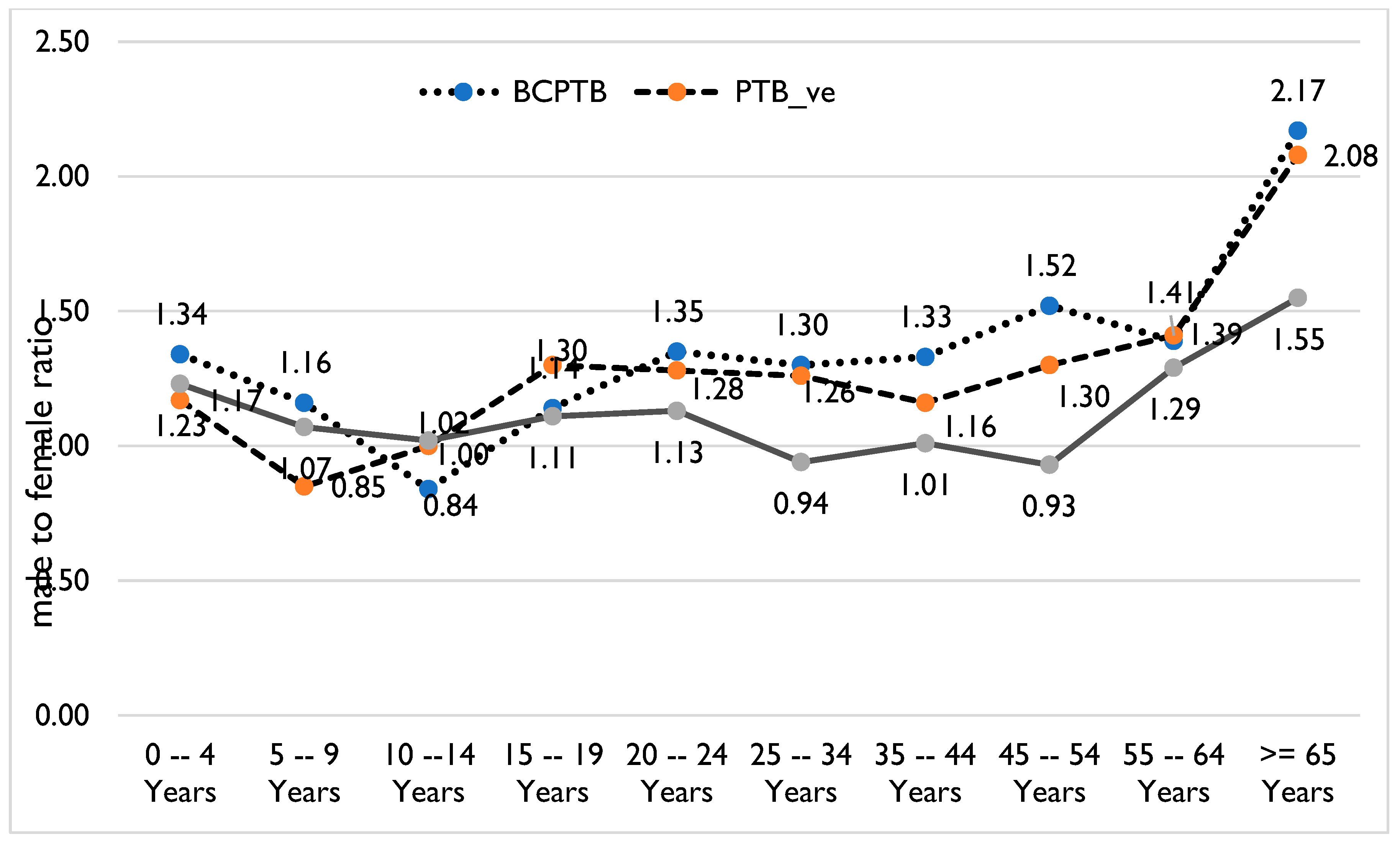

3. Results

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BCPTB | Bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary TB |

| DHIS2 | Health District Health Information System 2 |

| EPTB | Extra-pulmonary TB |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| LQAS | Lot quality assurance sampling |

| TB | Tuberculosis |

| UNHLM | United Nations High-Level Meeting |

References

- Sahu, S.; Ditiu, L.; Zumla, A. After the UNGA High-Level Meeting on Tuberculosis—What next and how? Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e558–e560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Roadmap Towards Ending Children and Adolescent TB in Ethiopia, 2019. National Roadmap Towards Ending Childhood and Adolescent TB in Ethiopia. Available online: https://ephi.gov.et/ (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Laycock, K.M.; Enane, L.A.; Steenhoff, A.P. Tuberculosis in adolescents and young adults: Emerging data on TB transmission and prevention among vulnerable young people. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laycock, K.M.; Eby, J.; Arscott-Mills, T.; Argabright, S.; Caiphus, C.; Kgwaadira, B.; Lowenthal, E.D.; Steenhoff, A.P.; Enane, L.A. Towards quality adolescent-friendly services in TB care. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2021, 25, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, S.S.; Waterous, P.M.; Atieno, V.F.; Bernays, S.; Bondarenko, Y.; Cruz, A.T.; de Oliveira, M.C.; Barrientos, H.D.; Enimil, A.; Ferlazzo, G.; et al. Caring for adolescents and young adults with tuberculosis or at risk of tuberculosis: Consensus statement from an international expert panel. J. Adolesc. Health 2023, 72, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, W.; Cao, G.; Jing, W.; Liu, J.; Liang, W.; Liu, M. Global burden of tuberculosis in adolescents and young adults: 1990–2019. Pediatrics 2024, 153, e2023063910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enane, L.A.; Lowenthal, E.D.; Arscott-Mills, T.; Matlhare, M.; Smallcomb, L.S.; Kgwaadira, B.; Coffin, S.E.; Steenhoff, A.P. Loss to follow-up among adolescents with tuberculosis in Gaborone, Botswana. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2016, 20, 1320–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. 2019. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2019-UNAIDS-data_en.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- World Health Organization. Global TB Report 2023. 2023. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/373828/9789240083851-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Peer, V.; Schwartz, N.; Green, M.S. Gender differences in tuberculosis incidence rates—A pooled analysis of data from seven high-income countries by age group and time period. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 997025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marçôa, R.; Ribeiro, A.I.; Zão, I.; Duarte, R. Tuberculosis and gender-Factors influencing the risk of tuberculosis among men and women by age group. Pulmonology 2018, 24, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, A.; Liu, X.; You, N.; Wang, Z.; Chen, C.; Zhu, L.; Martinez, L.; Lu, W.; Liu, Q. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection in School Contacts of Tuberculosis Cases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2024, 110, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, A.; Merker, M.; Collins, J.M.; Addise, D.; Aseffa, A.; Petros, B.; Ameni, G.; Niemann, S. Molecular epidemiology and drug resistance patterns of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex isolates from university students and the local community in Eastern Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, A.; Collins, J.M.; Aseffa, A.; Ameni, G.; Petros, B. Prevalence of pulmonary tuberculosis among students in three eastern Ethiopian universities. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2018, 22, 1210–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CSAIJ Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey; Central Statistical Agency: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; The DHS Program ICF: Calverton, MD, USA, 2016.

- Ethiopian Public Health Institute. HIV Related Estimates and Projections in Ethiopia for the Year 2021–2022. Available online: https://ephi.gov.et/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/HIV-Estimates-and-projection-for-the-year-2020-and-2021.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Miller, P.B.; Zalwango, S.; Galiwango, R.; Kakaire, R.; Sekandi, J.; Steinbaum, L.; Drake, J.M.; Whalen, C.C.; Kiwanuka, N. Association between tuberculosis in men and social network structure in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danarastri, S.; Perry, K.E.; Hastomo, Y.E.; Priyonugroho, K. Gender differences in health-seeking behaviour, diagnosis and treatment for TB. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2022, 26, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jode, H.D.; Flintan, F.E. How to do Gender and Pastoralism; IFAD: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Uplekar, M.; Atre, S. Health systems and tuberculosis control. In Essential Tuberculosis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 367–373. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, S.S.; Jamal, W.Z.; Zaidi, S.M.; Siddiqui, J.U.; Khan, H.M.; Creswell, J.; Batra, S.; Versfeld, A. Barriers to access of healthcare services for rural women—Applying gender lens on TB in a rural district of Sindh, Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, Y.; Gelaw, Y.A.; Hill, P.S.; Taye, B.W.; Van Damme, W. Community health extension program of Ethiopia, 2003–2018: Successes and challenges toward universal coverage for primary healthcare services. Glob. Health 2019, 15, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humayun, M.; Chirenda, J.; Ye, W.; Mukeredzi, I.; Mujuru, H.A.; Yang, Z. Effect of gender on clinical presentation of tuberculosis (TB) and age-specific risk of TB, and TB-human immunodeficiency virus coinfection. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofac512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehraj, J.; Khan, Z.Y.; Saeed, D.K.; Shakoor, S.; Hasan, R. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis among females in South Asia—Gap analysis. Int. J. Mycobacteriol. 2016, 5, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Tuberculosis in Women. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/ (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Seddon, J.A.; Chiang, S.S.; Esmail, H.; Coussens, A.K. The wonder years: What can primary school children teach us about immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis? Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, K.J.; Cruz, A.T.; Seddon, J.A.; Ferrand, R.A.; Chiang, S.S.; Hughes, J.A.; Kampmann, B.; Graham, S.M.; Dodd, P.J.; Houben, R.M.; et al. Adolescent tuberculosis. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, S.S.; Dolynska, M.; Rybak, N.R.; Cruz, A.T.; Aibana, O.; Sheremeta, Y.; Petrenko, V.; Mamotenko, A.; Terleieva, I.; Horsburgh, C.R.; et al. Clinical manifestations and epidemiology of adolescent tuberculosis in Ukraine. ERJ Open Res. 2020, 6, 00308-2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchakounte Youngui, B.; Tchounga, B.K.; Graham, S.M.; Bonnet, M. Tuberculosis infection in children and adolescents. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, A.J.; Roddy Mitchell, A.; Melville, R.E.; Hui, L.; Tong, S.Y.; Dunstan, S.J.; Denholm, J.T. Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in pregnancy: A systematic review. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0003578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathad, J.S.; Yadav, S.; Vaidyanathan, A.; Gupta, A.; LaCourse, S.M. Tuberculosis infection in pregnant people: Current practices and research priorities. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Chauhan, V.; Kumar, R.; Beri, G. Adolescent females are more susceptible than males for tuberculosis. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2021, 13, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Total New TB # Cases | Male | % Male | Female | % Female |

| New TB cases | 282,979 | 162,197 | 57.3 | 123,970 | 42.7 |

| Relapse TB cases | 7471 | 4354 | 58.3 | 3117 | 41.7 |

| All TB cases (new and relapse TB cases) | 290,450 | 166,479 | 57.3 | 127,087 | 42.7 |

| TB cases with HIV-positive status and on ART by age category | 13,515 | 6418 | 47.5 | 7097 | 52.5 |

| 0–4 years | 303 | 205 | 67.7 | 98 | 32.3 |

| 5–14 years | 588 | 263 | 44.7 | 325 | 55.3 |

| ≥15 years | 12,624 | 5950 | 47.1 | 6674 | 52.9 |

| TB cases by age group | |||||

| 0–4 years | 7776 | 4411 | 56.7 | 3365 | 43.3 |

| 5–9 years | 7781 | 3981 | 51.2 | 3800 | 48.8 |

| 10–14 years | 11,603 | 5508 | 47.5 | 6095 | 52.5 |

| 15–19 years | 30,625 | 16,808 | 54.9 | 138,817 | 45.1 |

| 20–24 years | 50,152 | 28,624 | 57.1 | 21,528 | 42.9 |

| 25–34 years | 73,498 | 42,380 | 57.7 | 31,118 | 42.3 |

| 35–44 years | 45,376 | 25,886 | 19,490 | 43 | |

| 45–54 years | 27,687 | 16,271 | 58.8 | 11,416 | 41.2 |

| 55–64 years | 16,489 | 10,148 | 61.5 | 6341 | 38.5 |

| ≥65 years | 11,992 | 8180 | 68.2 | 3812 | 31.8 |

| BCPTB | 108,671 | 62,333 | 57.4 | 46,339 | 42.6 |

| Clinical PTB | 108,671 | 32,660 | 57.5 | 24,176 | 42.5 |

| EPTB | 63,172 | 33,068 | 52.3 | 30,104 | 47.7 |

| Relapse | 7471 | 4354 | 58.3 | 3117 | 41.7 |

| TB cases by region | |||||

| Sidama | 17,041 | 10,030 | 58.9 | 7011 | 41.1 |

| Gambella | 2447 | 1564 | 63.9 | 883 | 36.1 |

| Dire Dewa | 3078 | 1824 | 59.3 | 1254 | 40.7 |

| Amhara | 36,768 | 20,653 | 56.2 | 16,115 | 43.8 |

| South West Ethiopia Region (SWEP) | 6544 | 3647 | 55.7 | 2897 | 44.3 |

| Harari | 1560 | 887 | 56.9 | 673 | 43.1 |

| Addis Ababa | 15,374 | 8049 | 52.4 | 7325 | 47.6 |

| Afar | 5215 | 3172 | 60.8 | 2043 | 39.2 |

| Somali | 14,654 | 8172 | 55.8 | 6482 | 44.2 |

| Central Ethiopia Region (CER) | 10,395 | 5723 | 55.1 | 4672 | 44.9 |

| South Ethiopia Region (SER) | 16,230 | 9143 | 56.3 | 7087 | 43.7 |

| Benishangul Gumuz | 1805 | 1130 | 62.6 | 675 | 37.4 |

| Oromia | 97,514 | 54,042 | 55.4 | 43,472 | 44.6 |

| (a) | ||||||||

| Variables | COR (for the ratio between males and females) | 95% CI | p-Value | |||||

| Age Category | ||||||||

| <5 years | 1 | |||||||

| 5–9 years | −1.151 | −1.899 | −0.403 | 0.003 | ||||

| 10–19 years | −1.432 | −2.087 | −0.778 | 0 | ||||

| Adult >20 years | 0.085 | −0.481 | 0.651 | 0.769 | ||||

| Type of TB | ||||||||

| Clinical PTB | 1 | |||||||

| BCPTB | 0.201 | −0.206 | 0.608 | 0.333 | ||||

| EPTB | −0.869 | −1.283 | −0.454 | 0 | ||||

| Region | ||||||||

| City administration | 1 | |||||||

| Amhara | −0.263 | −0.979 | 0.453 | 0.472 | ||||

| Benishangul Gumuz | 0.274 | −0.442 | 0.99 | 0.453 | ||||

| Gambella | −0.103 | −0.837 | 0.632 | 0.784 | ||||

| National | −0.182 | −0.897 | 0.534 | 0.619 | ||||

| Southern Nations and Nationality and Peoples Region (SNNPR) | −0.37 | −0.912 | 0.172 | 0.181 | ||||

| Oromia | −0.146 | −0.862 | 0.57 | 0.689 | ||||

| Pastoralist | 0.107 | −0.414 | 0.629 | 0.687 | ||||

| Sidama | 0.208 | −0.508 | 0.924 | 0.568 | ||||

| Geographic Category | ||||||||

| City administration | 1 | |||||||

| Agrarian | −0.102 | −0.522 | 0.319 | 0.635 | ||||

| National | −0.178 | −0.893 | 0.538 | 0.627 | ||||

| Pastoralist | 0.081 | −0.485 | 0.647 | 0.779 | ||||

| (b) | ||||||||

| Variables | COR (for the ratio * between males and females) | 95% CI | p-value | AOR (for the ratio between males and females) | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

| Age Category | ||||||||

| <5 years | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 5–9 years | −1.151 | −1.899 | −0.403 | 0.003 | −1.258 | −2.007 | −0.509 | 0.001 |

| 10–19 years | −1.432 | −2.087 | −0.778 | 0 | −1.527 | −2.182 | −0.872 | 0 |

| Adult >20 years | 0.085 | −0.481 | 0.651 | 0.769 | 0.013 | −0.553 | 0.579 | 0.964 |

| Type of TB | ||||||||

| Clinical PTB | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| BCPTB | 0.201 | −0.206 | 0.608 | 0.333 | 0.16 | −0.246 | 0.567 | 0.439 |

| EPTB | −0.869 | −1.283 | −0.454 | 0 | −0.928 | −1.342 | −0.513 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dememew, Z.; Deribew, A.; Zegeye, A.; Janfa, T.; Kegne, T.; Alemayehu, Y.; Gebreyohannes, A.; Deka, S.; Suarez, P.; Datiko, D.; et al. A High Burden of Infectious Tuberculosis Cases Among Older Children and Young Adolescents of the Female Gender in Ethiopia. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2025, 10, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10030079

Dememew Z, Deribew A, Zegeye A, Janfa T, Kegne T, Alemayehu Y, Gebreyohannes A, Deka S, Suarez P, Datiko D, et al. A High Burden of Infectious Tuberculosis Cases Among Older Children and Young Adolescents of the Female Gender in Ethiopia. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2025; 10(3):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10030079

Chicago/Turabian StyleDememew, Zewdu, Atakilt Deribew, Amtatachew Zegeye, Taye Janfa, Teshager Kegne, Yohannes Alemayehu, Asfawosen Gebreyohannes, Sidhartha Deka, Pedro Suarez, Daniel Datiko, and et al. 2025. "A High Burden of Infectious Tuberculosis Cases Among Older Children and Young Adolescents of the Female Gender in Ethiopia" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 10, no. 3: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10030079

APA StyleDememew, Z., Deribew, A., Zegeye, A., Janfa, T., Kegne, T., Alemayehu, Y., Gebreyohannes, A., Deka, S., Suarez, P., Datiko, D., & Schwarz, D. (2025). A High Burden of Infectious Tuberculosis Cases Among Older Children and Young Adolescents of the Female Gender in Ethiopia. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 10(3), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10030079