The Concentration of Urban Functions Within Transformed City Areas Due to the Deployment of a Multimodal Transit Hub—A Case Study: Barcelona, Berlin, and London

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (I)

- What urban functions develop within urban transformation areas with MTHs and within MTHs themselves? To address this question, it is hypothesized that urban transformation areas are developed according to 15MC principles, as they encompass all of its urban functions, while an MTH has at least one urban function—commerce.

- (II)

- What is the urban structure of transformed areas with an MTH? As a possible answer, it is assumed that commercial and working areas concentrate around MTHs, while other urban functions are spread throughout the area.

- (III)

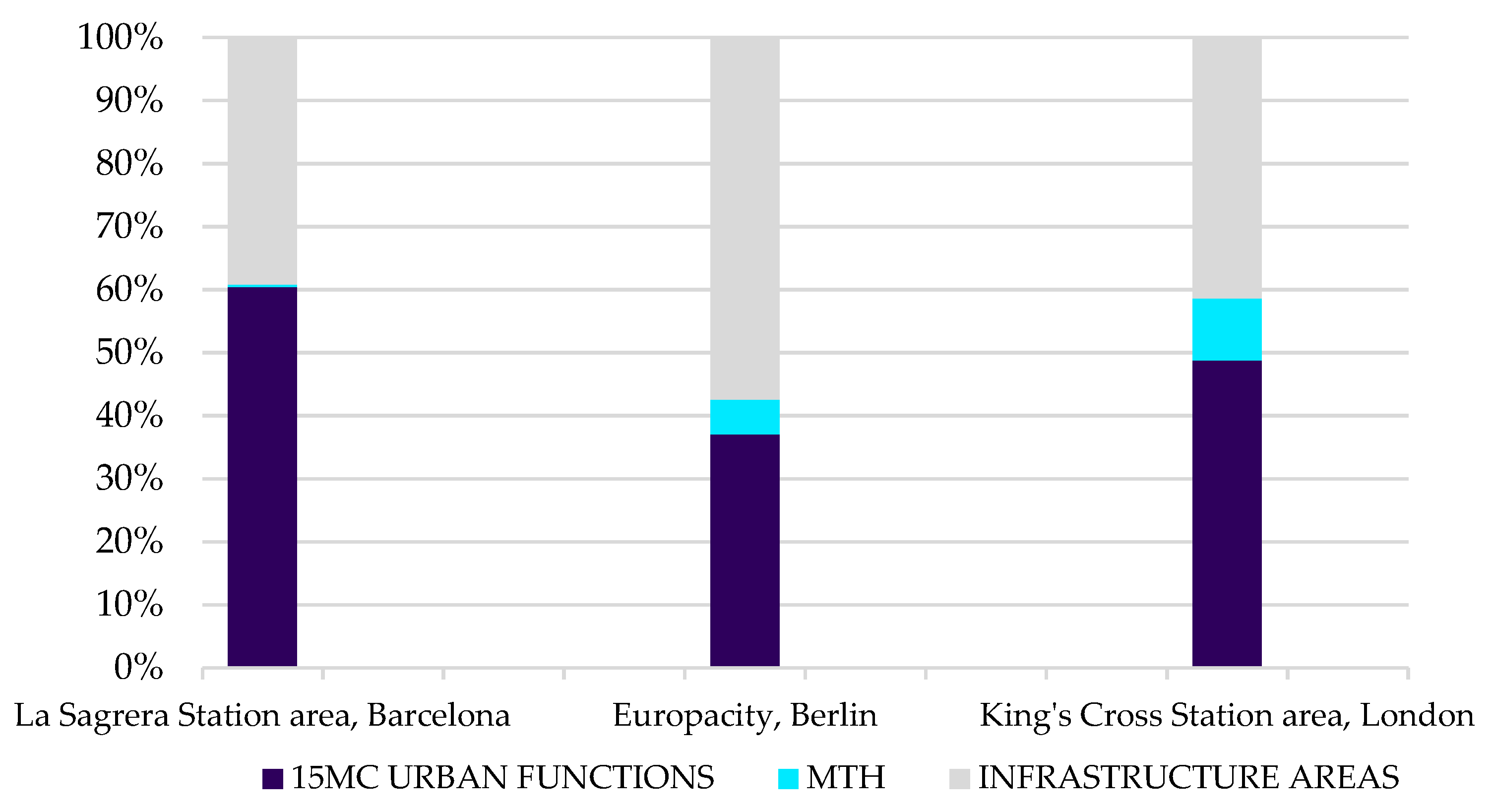

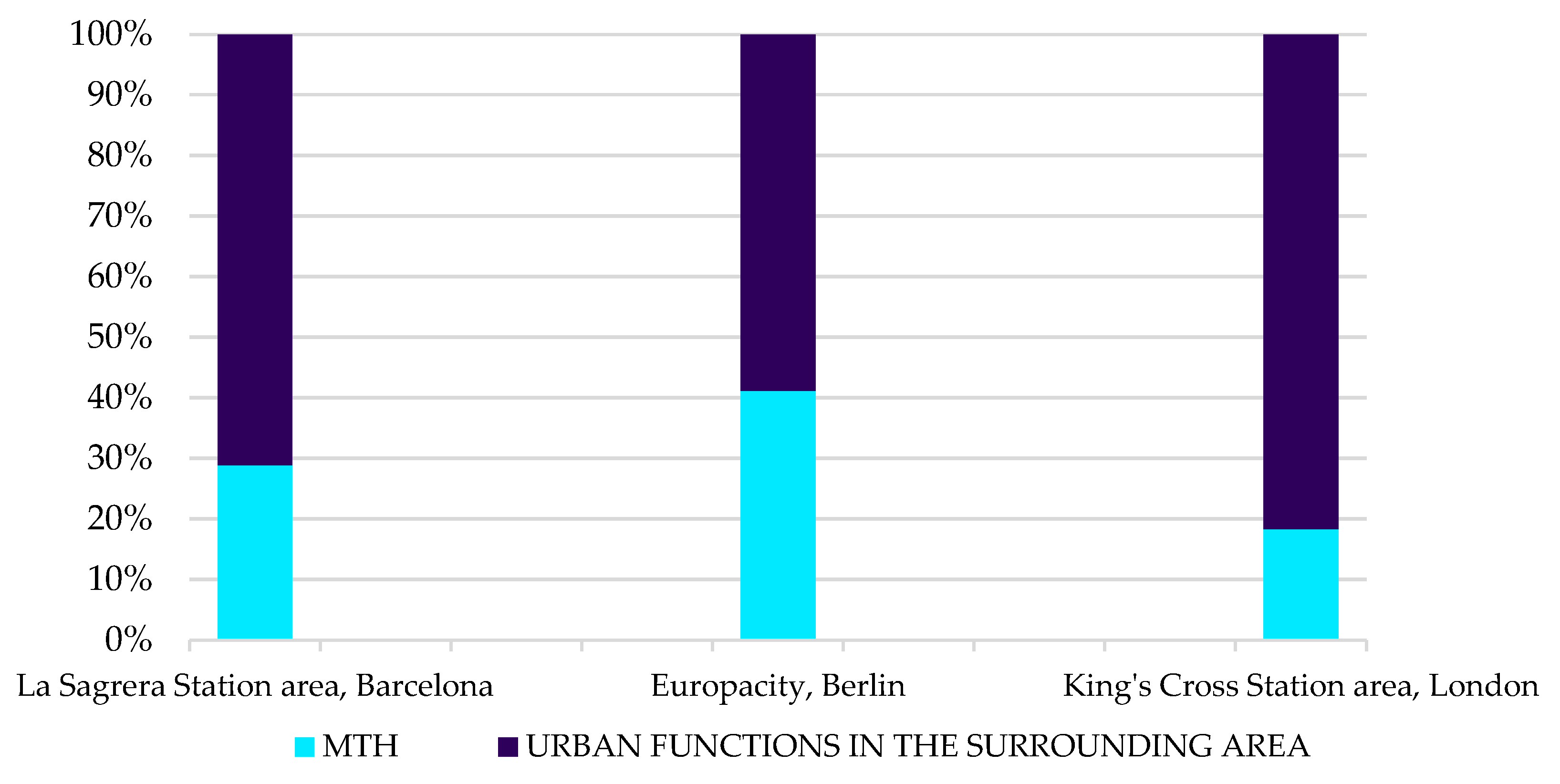

- What insights are provided by the economic value of urban functions in transformed city areas with MTHs into the significance of these projects? In exploring this question, it is proposed to compare the economic values of urban functions and MTHs. It is expected that the economic value of urban functions within transformed city areas with MTHs will show that investments are largely directed toward the development of urban functions in the surrounding areas of MTHs.

2. Materials and Methods

Mapping Urban Functions in Urban Transformation Areas and Within MTHs

3. Results

3.1. La Sagrera Station, Barcelona

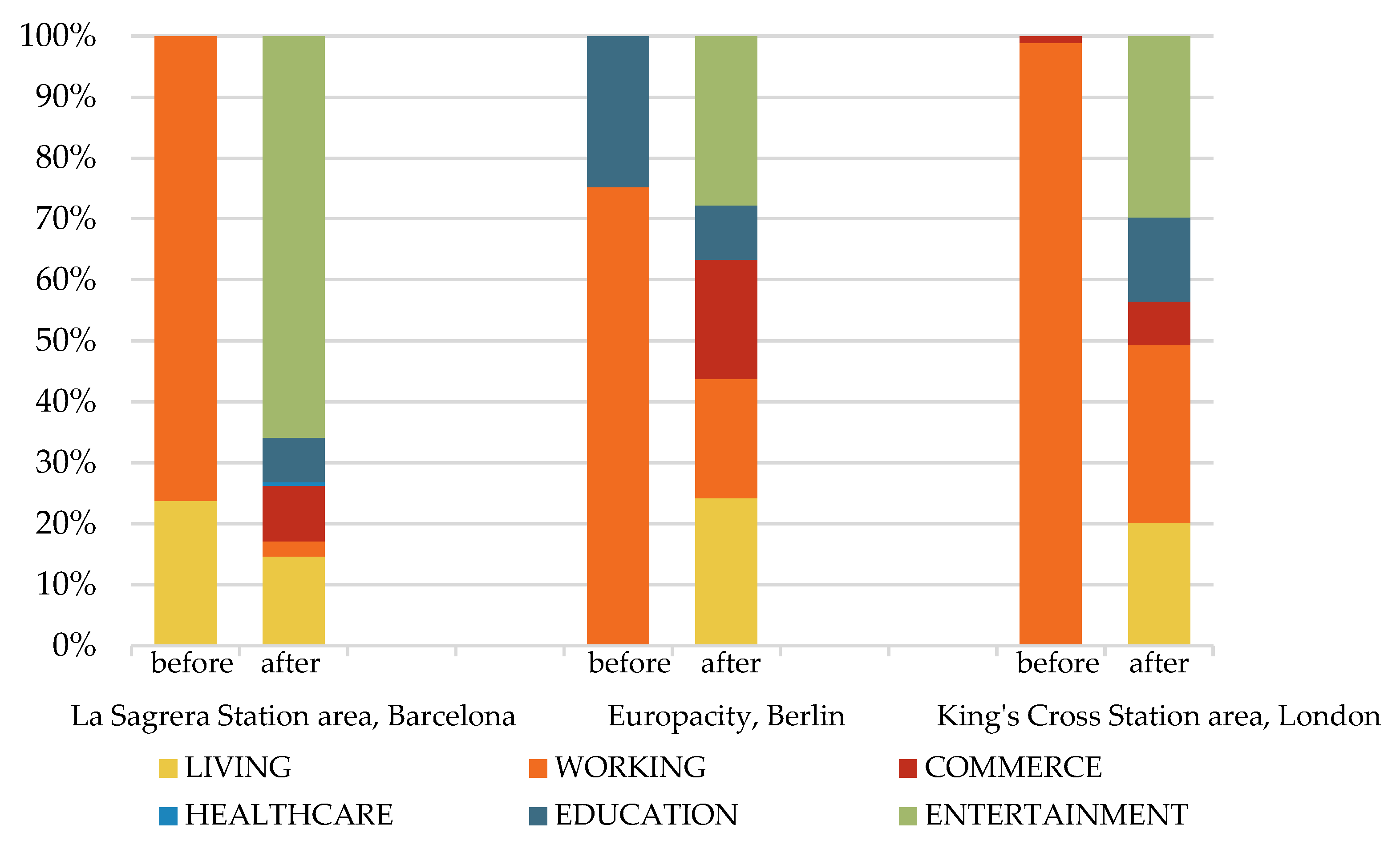

3.1.1. Urban Functions Within the La Sagrera Station Area

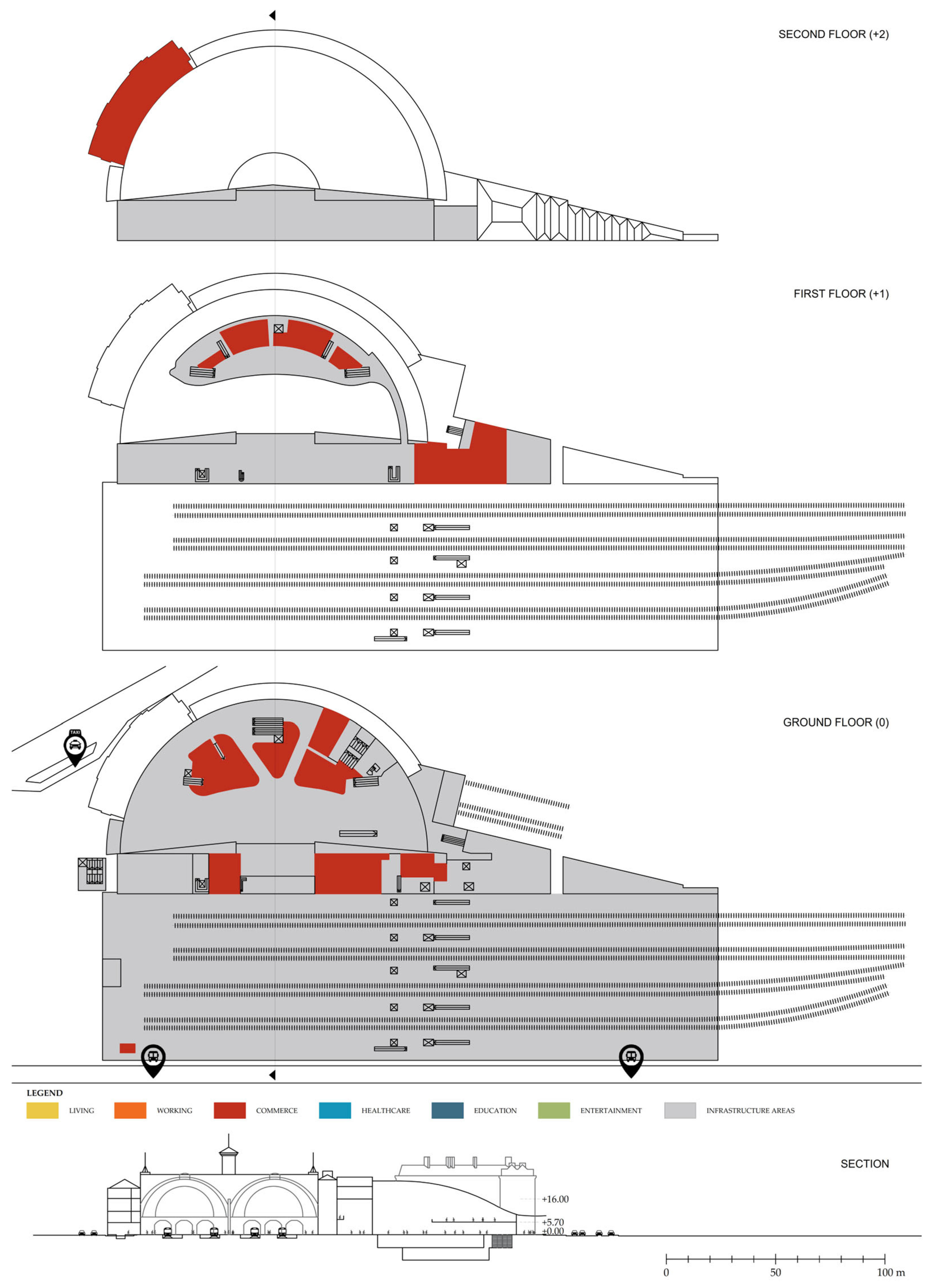

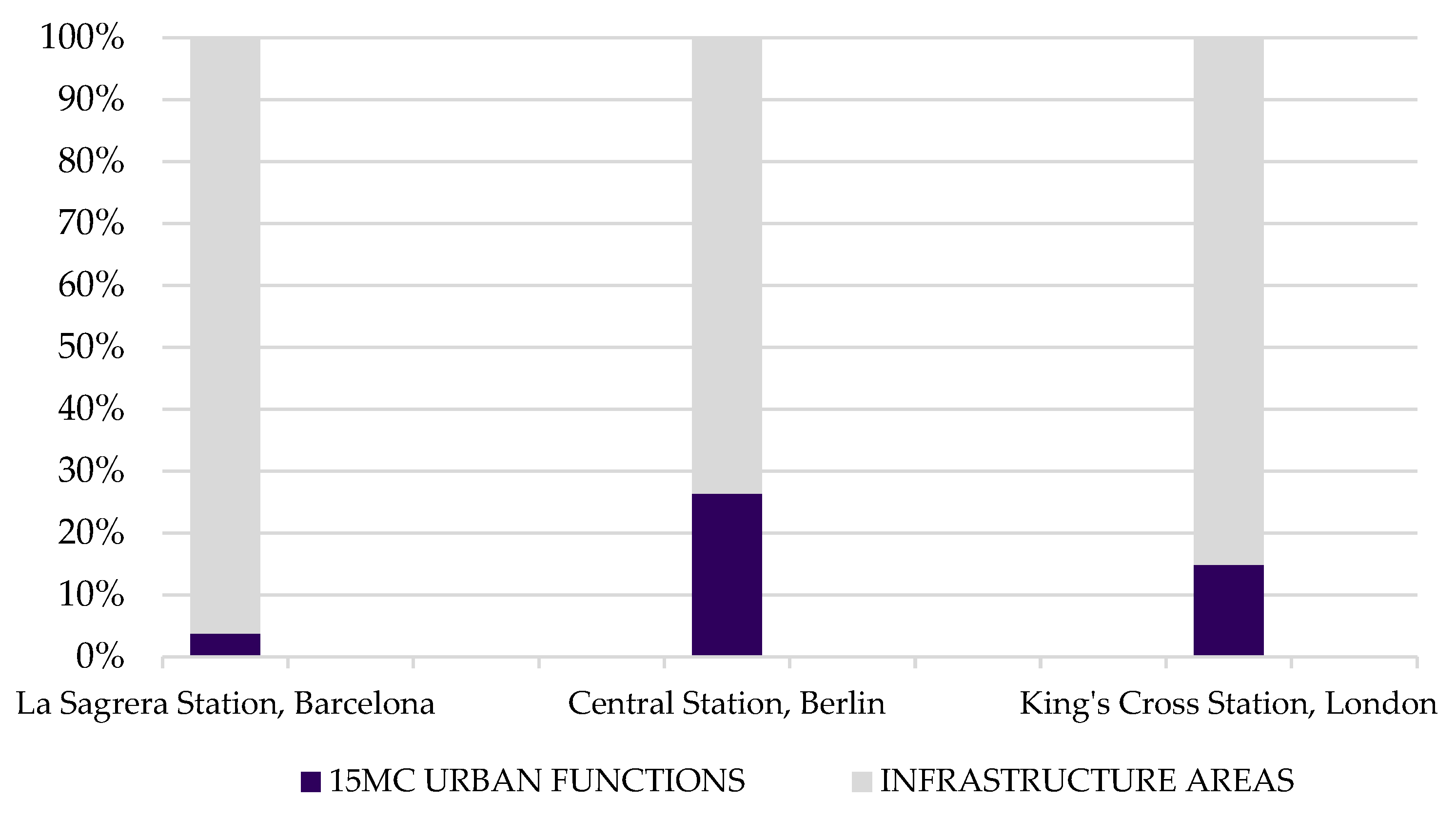

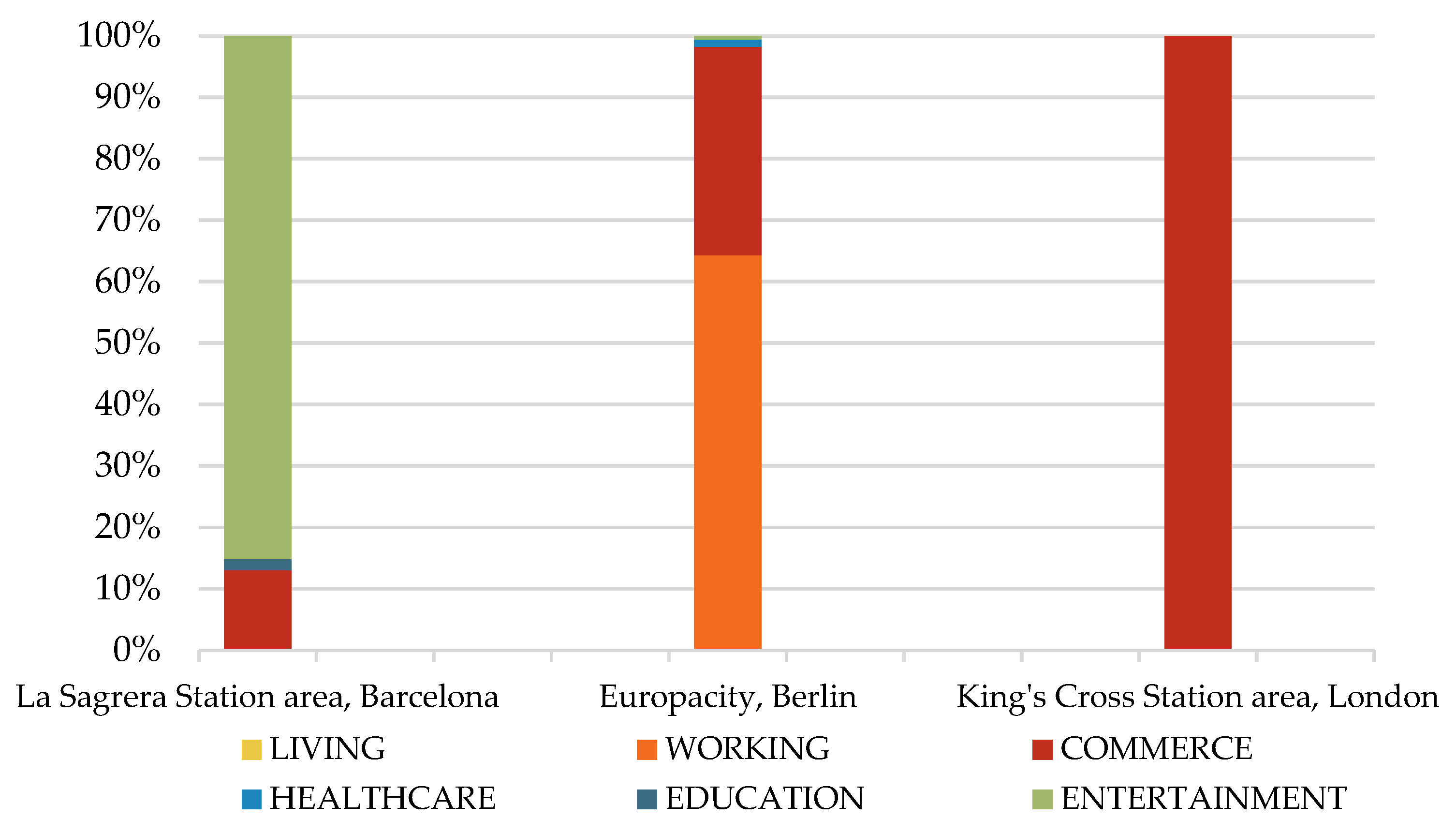

3.1.2. Urban Functions Within La Sagrera Station

3.1.3. Estimated Investment Values for the Transformation of La Sagrera Station Area

3.2. Central Station, Berlin

3.2.1. Urban Functions Within the Heidestrasse Area (Europacity)

3.2.2. Urban Functions Within Berlin Central Station

3.2.3. Estimated Investment Values for the Transformation of Heidestrasse Area (Europacity)

3.3. King’s Cross Station, London

3.3.1. Urban Functions Within the King’s Cross Area

3.3.2. Urban Functions Within King’s Cross Station

3.3.3. Estimated Investment Values for the Transformation of the King’s Cross Area

4. Discussion

4.1. Concentration of Urban Functions Supports Urban Diversity

4.2. Prevalence of Investment in Urban Transformation Area over MTH

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hernández, S.; Monzón, A. Key factors for defining an efficient urban transport interchange: Users’ perceptions. Cities 2016, 50, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litman, T. Land use impact costs of transportation. Word Policy Pract. 1995, 1, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camagni, R. Sustainable urban development: Definition and reasons for a research programme. Int. J. Environ. Pollut. 1998, 10, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aono, S. Identifying Best Practices for Mobility Hubs Prepared for TransLink; University of British Columbia: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wenner, F.; Thierstein, A. High speed rail as urban generator? An analysis of land use change around European stations. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2021, 30, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukić, T.; Mrđa, A.; Perkov, K. Urbana Obnova, Urbana Regeneracija Donjega Grada, Gornjega Grada i Kaptola/Povijesne Urbane Cjeline Grada Zagreba, 1st ed.; University of Zagreb, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Urban Planning, Spatial Planning and Landscape Architecture: Zagreb, Croatia, 2020; ISBN 978-953-8042-63-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini, L. Nodes and places: Complexities of railway station redevelopment. Eur. Plan. Stud. 1996, 4, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, L. Spatial Development Patterns and Public Transport: The Application of an Analytical Model in the Netherlands. Plan. Pract. Res. 1999, 14, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caset, F.; Marques Teixeira, F.; Derudder, B.; Boussauw, K.; Witlox, F. Planning for nodes, places, and people in Flandres and Brussels: An empirical railway station assessment tool for strategic decision-making. J. Transp. Land Use 2019, 12, 811–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicki, M.; Hauller, S.; Bernauer, T.; Kaufmann, D. Beyond a transport node? What residents want from transforming railway stations? Eur. Plan. Stud. 2024, 32, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzón, A.; Hernández, S.; Di Ciommo, F. Efficient urban interchanges: The City-HUB model. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 14, 1124–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, A.; Blaschke, T. A Generic Classification Scheme for Urban Structure Types. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N. Urban form revisited—Selecting indicators for characterizing European cities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 96, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yuan, J. Is There a Regulation in the Expansion of Urban Spatial Structure? Empirical Study from the Main Urban Area in Zhengzhou, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peimani, N.; Kamalipour, H. Assembling Transit Urban Design in the Global South: Urban Morphology in Relation to Forms of Urbanity and Informality in the Public Space Surrounding Transit Stations. Urban Sci. 2022, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, R.R. The Central Business District Core-Frame Concept and Some of Its Implications. Yearb. Assoc. Pac. Coast Geogr. 1960, 22, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, I. Railway station, The Image of the City, and transit-oriented development: An appraisal of the cognitive value of transit hubs. Asian Geogr. 2023, 42, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noaime, E.; Alalouch, C.; Mesloub, A.; Hamdoun, H.; Gnaba, H.; Alnaim, M.M. Urban Centrality as a Catalyst for City Resilience and Sustainable Development. Land 2025, 14, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartosiewicz, B.; Marcińczak, S. Investigating polycentric urban regions: Different measures—Different results. Cities 2020, 105, 102855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sýkora, L.; Mulíček, O.; Maier, K. City regions and polycentric territorial development: Concepts and practice. Urban Res. Pract. 2009, 2, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosten, W.J. Railway stations and a geography of networks. In Proceedings of the 6th Annual Congress of the Netherlands Research School for Transport, Infrastructure and Logistics, Hague, The Netherlands, 30 October 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Garda, E.; Gerbino, A.; Mangosio, M. Italian railway stations heritage. Int. J. Herit. Archit. Stud. Repairs Maint. 2017, 2, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Reeves, C.D.; Dalton, R.C.; Pesce, G. Context and Knowledge for Functional Buildings from the Industrial Revolution Using Heritage Railway Signal Boxes as Exemplar. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2020, 11, 232–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustin, R. From the Archive: Christaller’s Central Place Theory. Teach. Geogr. 2020, 45, 12–14. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26890772 (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Ahac, M.; Gašparović, S.; Šmit, K. Infrastructure in Post-industrial Urban Landscapes. In The Reimagining of Urban Spaces. A Journey Through Post-Industrial Cityscapes; Lakušić, S., Pavičić, J., Stojčić, N., Scholten, P.W.A., van Sinderen Law, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2024; pp. 135–148. ISBN 978-3-031-75649-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bellet Sanfeliu, C.; Santos Ganges, L. The high-speed rail project as an urban redevelopment tool. The cases of Zaragoza and Valladolid. Belgeo 2016, 3, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Dai, S.; Xia, H. Reuse of Abandoned Railways Leads to Urban Regeneration: A Tale from a Rust Track to a Green Corridor of Zhangjiakou. Urban Rail Transit 2020, 6, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, L.; Spit, T. Cities on Rails: The Redevelopment of Railway Stations and their Surroundings, 1st ed.; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 1998; ISBN 978-0-419-22760-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bodnár, B.; Csomós, G. Exploring the relationship between the creation of an intermodal passenger terminal and the urban development of Debrecen: A case study. Quaest. Geogr. 2019, 38, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, F.; de Abreu e Silva, J. Smart Cities: Definitions, Evolution of the Concept and Examples of Initiatives. In Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure; Leal Filho, W., Azul, A., Brandli, L., Özuyar, P., Wall, T., Eds.; Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-319-71059-4. [Google Scholar]

- Gargiulo, C.; de Ciutiis, F. Urban Transformation and Property Value Variation. The Role of HS Stations. TeMa-J. Mobil. Land Use Environ. 2010, 3, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichiensan, V.; Wasuntarasook, V.; Hayashi, Y.; Kii, M.; Prakayaphun, T. Urban Rail Transit in Bangkok: Chronological Development Review and Impact on Residential Property Value. Sustainability 2022, 14, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrezion, G.; Pels, E.; Rietveld, P. The Impact of Railway Stations on Residential and Commercial Property Value: A Meta-analysis. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2007, 35, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, S.; Lamson-Hall, P.; Blei, A.; Shingade, S.; Kumar, S. Densify and Expand: A Global Analysis of Recent Urban Growth. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumakoshi, Y.; Koizumi, H.; Yoshimura, Y. Diversity and density of urban functions in station areas. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2021, 89, 101679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. Next-Gen TOD: Transforming Transit Oriented Development to Embrace New Challenges and Opportunities. Urban Rail Transit 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibri, S.E.; Krogstie, J.; Kärrholm, M. Compact city planning and development: Emerging practices and strategies for achieving the goals of sustainability. Dev. Built Environ. 2020, 4, 100021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobniak, A.; Stangel, M. Fostering Local Urban Centers in relation to district train stations as a part of the transition from a post-industrial to a sustainable city: A case study of Katowice. Bull. Geogr. Socio-Econ. Ser. 2024, 64, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, L.; D’Autilia, R.; Marrone, P.; Montella, I. Graph Representation of the 15-Minute City: A Comparison between Rome, London, and Paris. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocca, A. Public space and 15-minutes city. A conceptual exploration for the functional reconfiguration of the proximity city. Tema. J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2021, 14, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolański, M. The Potential Role of Railway Stations and Public Transport Nodes in the Development of “15-Minute Cities”. Infrastructures 2023, 8, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, Z.; Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R.; Lassaube, U.; Chabaud, D.; Moreno, C. Mapping the Implementation Practices of the 15-Minute City. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 2094–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.; Sykes, O. The concept of polycentricity in European spatial planning: Reflections on its interpretation and application in the practice of spatial planning. Int. Plan. Stud. 2004, 9, 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, P. Planning for Polycentricity in European Metropolitan Areas-Challenges, Expectations and Practices. Plan. Pract. Res. 2013, 28, 400–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.; Hoyler, M.; Derudder, B.; Liu, X.; Meijers, E. Governing polycentric urban regions. Territ. Politics Gov. 2023, 11, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, J.F.; Silva, C.; Seisenberger, S.; Büttner, B.; McCormick, B.; Papa, E.; Cao, M. Classifying 15-minute Cities: A review of worldwide practices. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2024, 189, 104234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Song, W.; Dong, X. Evaluating the Space Use of Large Railway Hub Station Areas in Beijing toward Integrated Station-City Development. Land 2021, 10, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso de Matos, A.; Sobrino Simal, J.; de Lima Lourencetti, F. The Lisbon and Seville stations: Their place within railway station typology and their impact on the organization of urban space; EdA Esempi di Architettura: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-Pandemic Cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Ortiz, C.; Marquet, O.; Mojica, L.; Vich, G. Barcelona under the 15-Minute City Lens: Mapping the Accessibility and Proximity Potential Based on Pedestrian Travel Times. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elldér, E. The 15-minute city dilemma? Balancing local accessibility and gentrification in Gothenburg, Sweden. Transp. Res. Part D 2024, 135, 104360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadoppoulus, E.; Sdoukopoulos, A.; Politis, I. Measuring compliance with the 15-minute city concept: State-of-the-art, major components and further requirements. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.meet.barcelona/en/visit-and-love-it/points-interest-city/la-sagrera-99400387329?utm (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Baron, N. Who killed Barcelona’s High Speed Station Promises? Infrastructure political capture, scaling narratives and the urban fabric. Eur. J. Geogr. 2019, 10, 6–22. Available online: https://eurogeojournal.eu/index.php/egj/article/view/64/211 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- PPIAF Global Infrastructure Hub. Available online: https://www.gihub.org/quality-infrastructure-database/case-studies/sagrera-railway-station/ (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- The New Gate to Europe. Available online: http://barcelonacatalonia.cat/b/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/The-new-gate-to-Europe.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Diari Ara. Available online: https://en.ara.cat/society/barcelona-is-promoting-the-construction-of-one-of-the-new-neighborhoods-around-sagrera_1_5348692.html (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- La Vanguardia. Available online: https://www.lavanguardia.com/vida/20120806/54333460667/parque-sant-andreu-sagrera-plaza-mil-banderas.html (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Railway Gazette International. Available online: https://www.railwaygazette.com/in-depth/stations-barcelonas-next-rail-hub-nears-completion/67792.article (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Available online: https://www.bauwelt.de/themen/Die-Berliner-Luftfahrtsammlung-Berlin-Aviatisches-Museum-Johannisthal-Luftfahrtmuseum-Krakau-2095938.html (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Berlin Heidestrasse Master Plan. Available online: https://www.berlin.de/sen/stadtentwicklung/staedtebau/umfeld-hauptbahnhof/europacity/ (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Berlin.de. The Official Website of Berlin. Available online: https://www.berlin.de/en/attractions-and-sights/3561731-3104052-berlin-hauptbahnhof.en.html (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- SPIEGEL International. Available online: https://www.spiegel.de/international/spiegel/berlin-s-new-train-station-a-glass-armadillo-for-germany-s-capital-a-417598.html (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- CA IMMO. Available online: https://www.caimmo.com/en/portfolio/project/europacity-1/ (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Property Developments. Available online: https://propertydevelopments.com/listing/europacity/ (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Kings Cross. About the Development. Available online: https://www.kingscross.co.uk/about-the-development (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- London Plan 2004. Available online: https://www.london.gov.uk/programmes-strategies/planning/london-plan/past-versions-and-alterations-london-plan/london-plan-2004 (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- King’s Cross Opportunity Area Planning & Development Brief. Available online: https://www.camden.gov.uk/documents/20142/3797089/King%27s+Cross+Opportunity+Area+Planning+and+Development+Brief.pdf/c11edd6b-a2e4-8f7a-083b-00b6a4c04b86 (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- PPIAF. Railway Reform: Toolkit for Improving Rail Sector Performance, 2nd ed.; PPIAF: Washington, DC, USA; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 453–465. Available online: https://www.ppiaf.org/sites/ppiaf.org/files/documents/toolkits/railways_toolkit/index.html (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Dragan, W. Development of the urban space surrounding selected railway stations in Poland. Environ. Socio-Econ. Stud. 2017, 5, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnellan, C. Building the historic environment values and uses—Urban regeneration at King’s Cross Central, London. In Living (World) Heritage Cities. Opportunities, Challenges, and Future Perspectives of People-Centered Approaches in Dynamic Historic Urban Landscapes, 1st ed.; De Waal, M.S., Rosetti, I., De Groot, M., Jinadasa, U., Eds.; Sidestone Press: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 67–74. ISBN 978-94-6426-144-8. [Google Scholar]

- NetworkRail. Available online: https://www.networkrailconsulting.com/our-capabilities/network-rail-projects/kings-cross-station-redevelopment-programme/ (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Studylib. Available online: https://studylib.net/doc/18919024/non-technical-summary? (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- UrbanPlan. Available online: https://urbanplan.uli.org/resources/overview/project-snapshots/kings-cross/ (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Martínez-Corral, A.; Cárcel-Carrasco, J.; Colmenero Fonseca, F.; Kannampallil, F.F. Martínez-Corral, A.; Cárcel-Carrasco, J.; Fonseca, F.C.; Kannampallil, F.F. Urban–Spatial Analysis of European Historical Railway Stations: Qualitative Assessment of Significant Cases. Buildings 2023, 13, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M. King’s Cross: Renaissance for Whom? In Urban Design and the British Urban Renaissance; Punter, J., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 9780415443036. [Google Scholar]

- El Distrito de Sant Martí de Barcelona Será un Nuevo Polo de Vivienda Pública Con 2.089 Inmuebles Protegidos. Available online: https://elpais.com/espana/catalunya/2025-04-15/el-distrito-de-sant-marti-de-barcelona-sera-un-nuevo-polo-de-vivienda-publica-con-2089-inmuebles-protegidos.html (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- What Is Europacity? Available online: https://www.berlin.de/stk-mitte/unsere-stadtteilkoordinationen/stk-moabit-ost/aktuelles/artikel.821050.php? (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Exploded Time Bomb in Europacity. Available online: https://www.bmgev.de/mieterecho/alle-ausgaben/2024/me-single/article/geplatzte-zeitbombe-in-der-europacity/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Ballymore JV Picked for £500m King’s Cross Scheme. Available online: https://www.constructionenquirer.com/2024/10/10/ballymore-jv-picked-for-500m-kings-cross-scheme/? (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Acorn House. Available online: https://www.buildington.co.uk/buildings/4369/england/london-wc1x/314-320-gray-s-inn-road/acorn-house? (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Site W2N Kings Cross Regeneration. Available online: https://www.originhousing.org.uk/new-housing-developments/argent-triangle-w2n/? (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- R8 King’s Cross. Available online: https://www.buildington.co.uk/buildings/10330/england/london-n1c/york-way/r8-king-s-cross? (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Brenner, D. King’s Cross Railway Lands: A “Good Argument” For Change? DPU Working Paper No. 171; Development Planning Unit|The Bartlett|University College London: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, F.; Pafka, E. Shopping morphologies of urban transit station areas: A comparative study of central city station catchments in Toronto, San Francisco, and Melbourne. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 96, 103156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tong, D.; Liu, Y. Optimizing the spatial relocation of hospitals to reduce urban traffic congestion: A case study of Beijing. Trans. GIS 2019, 23, 365–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, M.; Smith-Collin, J. How do transportation barriers affect healthcare visits? Using mobile-based trajectory data to inform health equity. Transp. Res. Intedisciplinary Perspect. 2025, 30, 101345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gestaltung Kunst-Campus in Berlin Abgeschlossen—Eingang für Neues Stadtquartier. Available online: https://www.caimmo.com/de/presse/news/artikel/ca-immo-initiiert-szenetreffpunkt-in-der-berliner-europacity/ (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Martins da Conceição, A.L. From City’s Station to Station City. An Integrative Spatial Approach to the (Re)Development of Station Areas; Delft University of Technology, Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment: Delft, The Netherlands, 2015; ISBN 978-94-6186-409-3. [Google Scholar]

- K’oyoo, E.O. Sense of Place: Concepts, Importance and Methods of Study. Afr. Habitat Rev. J. 2025, 20, 3136–3146. [Google Scholar]

- Engel & Völkers Berlin Brandenburg Real Estate. Available online: https://www.engelvoelkersberlin.com/insights/europacity/? (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Mansion Global. Available online: https://www.mansionglobal.com/amp/articles/kings-cross-its-ongoing-renaissance-has-it-rising-as-a-london-hot-spot-01654340620? (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Jones Lang LaSalle Investments. Available online: https://internationalresidential.jll.com.hk/aktuelles/article/kings-cross-offers-some-of-the-best-residential-investment-prospects-in-london? (accessed on 27 July 2025).

| 15MC Urban Function * | La Sagrera Station Area, Barcelona (AR = 160 ha) | Europacity, Berlin (AR = 60 ha) | King’s Cross Station Area, London (AR = 34 ha) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | |

| Living (ha) | 6.40 | 14.19 | 0.00 | 5.39 | 0.00 | 3.34 |

| Working (ha) | 20.47 | 2.36 | 6.91 | 4.34 | 8.79 | 4.84 |

| Commerce (ha) | 0.00 | 8.82 | 0.00 | 4.34 | 0.10 | 1.18 |

| Healthcare (ha) | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Education (ha) | 0.00 | 6.99 | 2.28 | 1.98 | 0.00 | 2.29 |

| Entertainment (ha) | 0.00 | 63.72 | 0.00 | 6.18 | 0.00 | 4.93 |

| 15MC Urban Function * | La Sagrera Station, Barcelona (AR = 28.89 ha) | Central Station, Berlin (AR = 6.50 ha) | King’s Cross Station, London (AR = 4.78 ha) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Living (ha) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Working (ha) | 0.00 | 1.10 | 0.00 |

| Commerce (ha) | 0.95 | 0.58 | 0.71 |

| Healthcare (ha) | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| Education (ha) | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Entertainment (ha) | 6.19 ** | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| City | Year of Completion | Urban Transformation Area | Total Gross Area Within the Urban Transformation Area (GFA) * | Total Estimated Value for Construction of Buildings | Estimated Investment Value Per Square Meter of GFA | Total Area Under Public Open Spaces ** | Total Estimated Investment Value for Public Open Spaces | Estimated Investment Value Per Square Meter of Public Open Space | Overall Estimated Investment Value *** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barcelona | 2029–2050 | 160 ha | 942,935 m2 | EUR 1.46B | EUR 1548 | 128.56 ha | EUR 140.10M | EUR 109.00 | EUR 1.60B |

| Berlin | 2010–2027 | 60 ha | 819,000 m2 | EUR 916.75M | EUR 1119 | 94.45 ha | EUR 83.25M | EUR 68.13 | EUR 1.00B |

| London | 2011–2025 | 34 ha | 713,090 m2 | EUR 2.74B | EUR 3847 | 29.74 ha | EUR 56.73M | EUR 190.75 | EUR 2.80B |

| City | Years of Construction | The Total Gross Area of the MTH Building (GFA) * | Total Estimated Investment Value | Estimated Investment Value Per Square Meter of the MTH Building |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barcelona | 2010–2026 | 28.89 ha | EUR 650M | EUR 2249 |

| Berlin | 1995–2006 | 6.50 ha | EUR 700M | EUR 10,769 |

| London | 2007–2012 | 4.78 ha | EUR 630M | EUR 13,179 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anton, L.; Šmit, K.; Gašparović, S. The Concentration of Urban Functions Within Transformed City Areas Due to the Deployment of a Multimodal Transit Hub—A Case Study: Barcelona, Berlin, and London. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 327. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9080327

Anton L, Šmit K, Gašparović S. The Concentration of Urban Functions Within Transformed City Areas Due to the Deployment of a Multimodal Transit Hub—A Case Study: Barcelona, Berlin, and London. Urban Science. 2025; 9(8):327. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9080327

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnton, Lucija, Krunoslav Šmit, and Sanja Gašparović. 2025. "The Concentration of Urban Functions Within Transformed City Areas Due to the Deployment of a Multimodal Transit Hub—A Case Study: Barcelona, Berlin, and London" Urban Science 9, no. 8: 327. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9080327

APA StyleAnton, L., Šmit, K., & Gašparović, S. (2025). The Concentration of Urban Functions Within Transformed City Areas Due to the Deployment of a Multimodal Transit Hub—A Case Study: Barcelona, Berlin, and London. Urban Science, 9(8), 327. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9080327