Exploring Features of Pocket Parks That Related to Restorative Effects: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method: A Systematic Review

3. Results

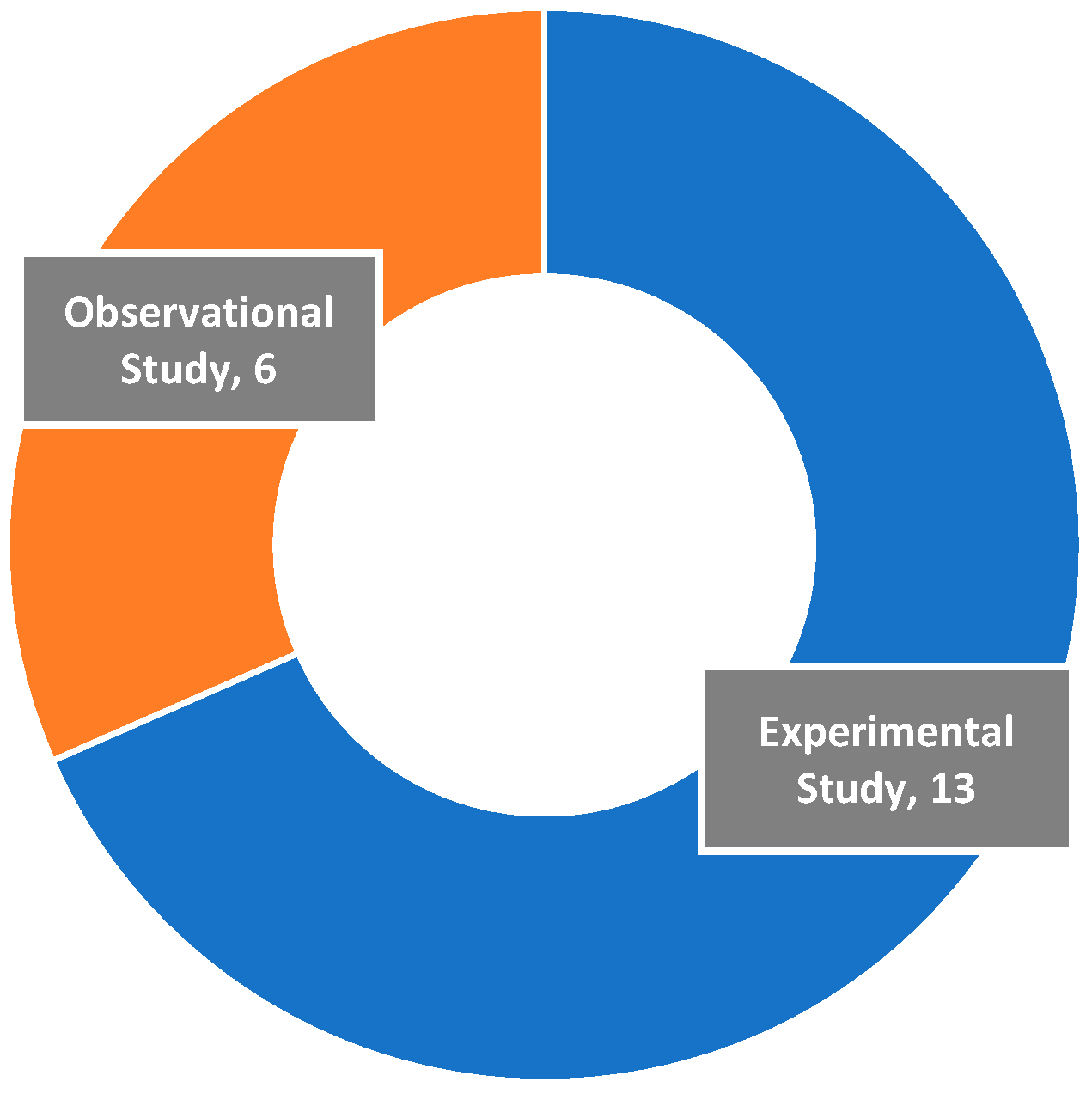

3.1. Study Characteristic

3.2. Assessment of Pocket Park Features

3.3. Assessment of Restoration

3.3.1. Subjective Measures

3.3.2. Objective Measures

3.4. Associations Between Pocket Park Features and Restoration

3.4.1. Visual Natural Features and Restoration

3.4.2. Facility Features and Restoration

3.4.3. Spatial Form Features and Restoration

3.4.4. Sound Features and Restoration

4. Discussion

4.1. Developing of Research over Time

4.2. Methodologies in Studying the Relationship Between Pocket Park Environments and Restoration

4.3. Existing Knowledge of Pocket Park Environments and Restoration

4.4. Limitations of This Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Syamili, M.; Takala, T.; Korrensalo, A.; Tuittila, E.-S.J.U.F. Happiness in urban green spaces: A systematic literature review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 86, 128042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.T.; Gaston, K.J. Human–nature interactions and the consequences and drivers of provisioning wildlife. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 373, 20170092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steptoe, A.; Kivimäki, M. Stress and cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2012, 9, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajoo, K.S.; Karam, D.S.; Abdullah, M.Z. The physiological and psychosocial effects of forest therapy: A systematic review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 54, 126744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Papa, F.; Jaini, P.A.; Alpini, S.; Kenny, T. An epigenetics-based, lifestyle medicine–driven approach to stress management for primary patient care: Implications for medical education. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2020, 14, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, G.; Zhang, W.; Xu, R.; Wang, C.; Guo, Y.; Li, S. Attributable risks associated with hospital outpatient visits for mental disorders due to air pollution: A multi-city study in China. Environ. Int. 2020, 143, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.Y.; Li, X.J.; Yang, T.T.; Tan, S.H. Research on the Relationship between the Environmental Characteristics of Pocket Parks and Young People’s Perception of the Restorative Effects-A Case Study Based on Chongqing City, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, A.; Musacchio, L. Designing Small Parks: A Manual for Addressing Social and Ecological Concerns; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Naghibi, M.; Faizi, M.; Ekhlassi, A. Design possibilities of leftover spaces as a pocket park in relation to planting enclosure. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 64, 127273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordh, H.; Alalouch, C.; Hartig, T. Assessing restorative components of small urban parks using conjoint methodology. Urban For. Urban Green. 2011, 10, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschardt, K.K.; Schipperijn, J.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Use of small public urban green spaces (SPUGS). Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narandžić, T.; Ljubojević, M. Urban space awakening–identification and potential uses of urban pockets. Urban Ecosyst. 2022, 25, 1111–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerishnan, P.B.; Maruthaveeran, S.; Maulan, S.J.U.f. Investigating the usability pattern and constraints of pocket parks in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 50, 126647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Qu, H.; Ma, Y.; Wang, K.; Qu, H. Restorative benefits of urban green space: Physiological, psychological restoration and eye movement analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 301, 113930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordh, H.; Ostby, K. Pocket parks for people—A study of park design and Use. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.B.; Lin, X.Q.; Lin, S.M.; Chen, Z.Y.; Fu, W.C.; Wang, M.H.; Dong, J.W. Pocket Parks: A New Approach to Improving the Psychological and Physical Health of Recreationists. Forests 2023, 14, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschardt, K.K.; Stigsdotter, U.K.; Schipperrijn, J. Identifying Features of Pocket Parks that May Be Related to Health Promoting Use. Landsc. Res. 2016, 41, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Oh, W.; Ooka, R.; Wang, L. Effects of Environmental Features in Small Public Urban Green Spaces on Older Adults’ Mental Restoration: Evidence from Tokyo. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordh, H.; Hartig, T.; Hagerhall, C.M.; Fry, G. Components of small urban parks that predict the possibility for restoration. Urban For. Urban Green. 2009, 8, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.P.; Deng, X.; Cui, Y.Q.; Zhao, X. A Study of Soundscape Restoration in Office-Type Pocket Parks. Buildings 2024, 14, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesi, L.; Costa, P. Small Green Spaces in Dense Cities: An Exploratory Study of Perception and Use in Florence, Italy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, D.; Bild, E.; Tarlao, C.; Guastavino, C. Soundtracking the Public Space: Outcomes of the Musikiosk Soundscape Intervention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschardt, K.K.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Associations between park characteristics and perceived restorativeness of small public urban green spaces. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 112, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordh, H.; Hagerhall, C.M.; Holmqvist, K. Exploring View Pattern and Analysing Pupil Size as a Measure of Restorative Qualities in Park Photos. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Landscape and Urban Horticulture, Bologna, Italy, 9–13 June 2010; pp. 767–772. [Google Scholar]

- Naghibi, M.; Farrokhi, A.; Faizi, M. Small Urban Green Spaces: Insights into Perception, Preference, and Psychological Well-being in a Densely Populated Areas of Tehran, Iran. Environ. Health Insights 2024, 18, 11786302241248314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cegarra-Navarro, J.G.; Ruiz, F.J.A.; Martinez-Caro, E.; Garcia-Perez, A. Turning heterogeneity into improved research outputs in international R&D teams. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Han, M. Pocket parks in English and Chinese literature: A review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 61, 127080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerishnan, P.B.; Maruthaveeran, S. Factors contributing to the usage of pocket parks―A review of the evidence. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 58, 126985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Guo, R.; Guo, F.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Z. Pocket parks-A systematic literature review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 083003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menardo, E.; Brondino, M.; Hall, R.; Pasini, M. Restorativeness in natural and urban environments: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Rep. 2021, 124, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.M.; Trojan, J. The Restorative Value of the Urban Environment: A Systematic Review of the Existing Literature. Environ. Health Insights 2018, 12, 1178630218812805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordh, H.; Hagerhall, C.M.; Holmqvist, K. Tracking Restorative Components: Patterns in Eye Movements as a Consequence of a Restorative Rating Task. Landsc. Res. 2013, 38, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschardt, K.K.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Evidence for Designing Health Promoting Pocket Parks. Int. J. Archit. Res. 2014, 8, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudeau, C.; Steele, D.; Guastavino, C. A Tale of Three Misters: The Effect of Water Features on Soundscape Assessments in a Montreal Public Space. Front Psychol 2020, 11, 570797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.W.; Han, L.R.; Hao, R.S.; Mei, R. Understanding the relationship between small urban parks and mental health: A case study in Shanghai, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 78, 127784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Shao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, L. Developing a Pocket Park Prescription Program for Human Restoration: An Approach That Encourages Both People and the Environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.Y.; Qiu, B.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, J.G. Restorative Effects of Pocket Parks on Mental Fatigue among Young Adults: A Comparative Experimental Study of Three Park Types. Forests 2024, 15, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltz, J.; Grahn, P. Perceived sensory dimensions: An evidence-based approach to greenspace aesthetics. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 59, 126989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidlow, C.; van Kempen, E.; Smith, G.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Kruize, H.; Gražulevičienė, R.; Ellis, N.; Hurst, G.; Masterson, D.; Cirach, M. Development of the natural environment scoring tool (NEST). Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidlow, C.J.; Ellis, N.J.; Bostock, S.J.L. Development of the neighbourhood green space tool (NGST). Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 106, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saelens, B.E.; Frank, L.D.; Auffrey, C.; Whitaker, R.C.; Burdette, H.L.; Colabianchi, N. Measuring physical environments of parks and playgrounds: EAPRS instrument development and inter-rater reliability. J. Phys. Act. Health 2006, 3, S190–S207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, Ö. How to measure soundscape quality. In Proceedings of the Euronoise 2015 Conference, Maastricht, The Netherlands, 31 May–3 June 2015; pp. 1477–1481. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shacham, S. A shortened version of the Profile of Mood States. J. Personal. Assess. 1983, 47, 305–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takayama, N.; Korpela, K.; Lee, J.; Morikawa, T.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Park, B.-J.; Li, Q.; Tyrvainen, L.; Miyazaki, Y.; Kagawa, T. Emotional, Restorative and Vitalizing Effects of Forest and Urban Environments at Four Sites in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 7207–7230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begum, M.R.; Hossain, M.A. Validity and reliability of visual analogue scale (VAS) for pain measurement. J. Med. Case Rep. Rev. 2019, 2, 394–402. [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers, P.; Smits, N.; Donker, T.; Ten Have, M.; de Graaf, R. Screening for mood and anxiety disorders with the five-item, the three-item, and the two-item Mental Health Inventory. Psychiatry Res. 2009, 168, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimura, T.; Okanoya, K. Heart rate variability predicts emotional flexibility in response to positive stimuli. Psychology 2012, 3, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, P.J. The emotion probe: Studies of motivation and attention. Am. Psychol. 1995, 50, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Sun, X. Electrophysiological measures applied in user experience studies. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedblom, M.; Gunnarsson, B.; Iravani, B.; Knez, I.; Schaefer, M.; Thorsson, P.; Lundström, J.N. Reduction of physiological stress by urban green space in a multisensory virtual experiment. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.-C.; Li, D.; Jane, H.-A. Wild or tended nature? The effects of landscape location and vegetation density on physiological and psychological responses. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 167, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, U.K.; Senthil, R. Analysis of urban residential greening in tropical climates using quantitative methods. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2024, 31, 44096–44119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Hong, B. Pocket park in urban regeneration of China: Policy and perspective. City Environ. Interact. 2023, 19, 100109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Zhu, X. Lighting the night: Unveiling the restorative potential of urban green spaces in nighttime environments. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 107, 128769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngesan, M.R.; Karim, H.A.; Zubir, S.S. Human behaviour and activities in relation to Shah Alam urban park during nighttime. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 68, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Green, R.J.J.U.F. The effect of exposure to nature on children’s psychological well-being: A systematic review of the literature. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 81, 127846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurumi, T.; Managi, S. Environmental value of green spaces in Japan: An application of the life satisfaction approach. In Wealth, Inclusive Growth and Sustainability; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019; pp. 195–224. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R.; Wilson, E.O. The Biophilia Hypothesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Berto, R. Exposure to restorative environments helps restore attentional capacity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, C.L.; Horn, S.A. To nature or not to nature: Associations between environmental preferences, mood states and demographic factors. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, A.; Iwankowski, P. Where do we want to see other people while relaxing in a city park? Visual relationships with park users and their impact on preferences, safety and privacy. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 73, 101532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farage, M.A.; Miller, K.W.; Ajayi, F.; Hutchins, D. Design principles to accommodate older adults. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2012, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.; Smith, A.; Humphryes, K.; Pahl, S.; Snelling, D.; Depledge, M. Blue space: The importance of water for preference, affect, and restorativeness ratings of natural and built scenes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, J. The Experience of Landscape; Revised Edition; Wiley: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Appleton, J. The Experience of Landscape; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, G.R.; Pheasant, R.J.; Horoshenkov, K.V. Predicting perceived tranquillity in urban parks and open spaces. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2010, 38, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Kang, J. Towards the evaluation, description, and creation of soundscapes in urban open spaces. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2007, 34, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlinarić, A.; Horvat, M.; Šupak Smolčić, V. Dealing with the positive publication bias: Why you should really publish your negative results. Biochem. Medica 2017, 27, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauge, N.R.; Paul, M. The prevalence of and factors associated with inclusion of non-English language studies in Campbell systematic reviews: A survey and meta-epidemiological study. Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, 129. [Google Scholar]

| Author(s) and Year | Region | Sample Characteristics | Sampling | Data Collection | Tools Used for Restorative Outcome Assessment | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nordh et al., 2009 [19] | Sweden | Undergraduate and graduate students; M + F; and mean age = 26 | Random sample volunteers; n = 52 (M = 13, F = 39) | Measurement of pocket park features + Questionnaire (close-ended); and photographs (72 pocket parks) | Percentage of park components (hardscape, grass, lower ground vegetation, flowering plants, bushes, trees, and water) in relation to the total image, total ground surface of the park image, and visible ground surface of the park image; PRS (fascination, being-away); and self-designed questionnaire for the measurement of preference | There was a strong relationship between restoration likelihood and all environmental components, except flowering plants. Higher grass coverage was strongly correlated with increased restorative potential scores. Visibility of shrubs and trees was also a key predictor of restorative potential. While perceived park size significantly positively affected restorative potential, smaller parks with multiple positive environmental attributes achieved similar high restorative potential scores to larger parks. ‘Fascination’ was significantly correlated with water features and park size. ‘Being-away’ was significantly correlated with grass, shrubs, and trees. |

| Nordh, Hagerhall, and Holmqvist, 2010 [24] | Sweden | University students; M + F; and mean age = 23 | No sampling method; n = 33 (M = 9, F = 24) | Questionnaire (close-ended) + measurement of physiological response indicators; and photographs (38 pocket parks) | Self-designed questionnaire (a rating task where subjects indicate on a scale from 0 to 10 their ability to rest and recover focus in the environment shown in the photo); and pupil size | When assessing the restorative quality of parks, individuals primarily focused on components such as benches and other people. Heatmaps indicated that the majority of attention was concentrated within the park’s interior space, which was defined by the tree canopy acting as a ceiling, shrubs or trees as walls, and grass or other hard materials as the floor, with less attention given to areas outside the park’s perimeter. |

| Nordh, Alalouch, and Hartig, 2011 [10] | Norway | Residents in Oslo; M + F; and age between 19 and 75 years (mean = 43, ±12.9) | Random sample volunteers; n = 154 (M = 50, F = 104) | Web-based questionnaire (close-ended); and presented pairs of park environments with descriptive text, without using photos | Six park components (the components were grass, bushes, trees, flowerbeds, water features, and the number of other people in the park); and self-designed questionnaire for the assessment of the relative importance of park components in terms of restorative effects | When choosing a rest place in a pocket park, grass, trees, and the presence of other people were the most influential factors in summer. In terms of planning, the findings suggested that structural elements such as grass and trees should be prioritized over decorative elements such as flowers and water features. |

| Nordh, Hagerhall, and Holmqvist, 2013 [32] | Sweden | University students; M + F; and mean age = 23 | Random sample volunteers; n = 33 (M = 9, F = 24) | Questionnaire (close-ended) + measurement of physiological response indicators; and photographs (38 pocket parks) | Self-designed questionnaire (a rating task where subjects indicate on a scale from 0 to 10 their ability to rest and recover focus in the environment shown in the photo); eye dwell time in areas of interest; and eye fixation number in areas of interest | Participants focused the most on trees, benches, and bushes, which were important components for assessing whether an environment possessed restorative qualities. A positive correlation was found between grass and the likelihood of restoration. Although the other variables (water, hardscape, lower ground vegetation, flowering plants, bushes, trees, visually dominant element, other people and benches) did not have a significant association with restoration likelihood, it was notable that, except for water, the relationship appeared to be negative. |

| Nordh and Ostby, 2013 [15] | Norway | University students; M + F; and mean age = 29 | Random sample volunteers; n = 58 (M = 6, F = 52) | Questionnaire (close-ended + open-ended); and photographs (72 pocket parks) | Self-designed questionnaire (rating task where subjects indicate on a scale from 0 to 10 their ability to rest and recover focus in the environment shown in the photo); and self-designed open-ended questionnaire on the park components contributing to restorative experience | The most frequently mentioned factors contributing to high ratings of restoration likelihood were ‘a lot of grass’, ‘a lot of flowers/plants’, and ‘water features’. Additionally, participants emphasized the importance of park design on restoration likelihood, including enclosures, comfortable seating, and a calm atmosphere. The most commonly stated factors contributing to low ratings for restoration likelihood were “a lot of traffic”, “a lot of hard surfaces”, and “poorly shielded from the surroundings”. |

| Peschardt and Stigsdotter, 2013 [23] | Denmark | Park users; and M + F | Random sample; n = 686 | Onsite questionnaire + measurement of pocket park feature; and real landscape (nine pocket parks) | Eight park characteristics from PSD (serene, space, nature, rich in species, refuge, culture, prospect, and social); and PRS (being-away, extent, fascination, and compatibility) | Average park users’ perceptions of restorativeness were significantly influenced by ‘social’ and ‘serene’ factors. The most stressed park users exhibited a stronger preference for the ‘nature’ characteristic. |

| Peschardt and Stigsdotter, 2014 [33] | Denmark | Park users; M + F; and age between 28 and 65 years | Random sample; n = 6 (M = 5, F = 1) | Onsite interview; and real landscape (one pocket park) | Self-designed interview for the measurement of users’ restorative experiences | In terms of rest and restitution, park users considered sun, shade, and planting to be important. Varied terrain created fascination and provided opportunities for restoration. |

| Peschardt, Stigsdotter, and Schipperrijn, 2016 [17] | Denmark | Park users; and M + F | Random sample n = 214 | Onsite questionnaire (close-ended + open-ended) + measurement of pocket park features; and real landscape (nine pocket parks) | Noise level; noise type; green ground cover percentage; eye-level green percentage; tree canopies percentage; size and shape of pocket park; nine park components from EAPRS (paved trail, unpaved trail, café, historical feature, table, other seating, flowerbeds and special shrubs, view outside park, and playground); and PRS (being-away, extent, fascination, and compatibility) | The feature positively associated with ‘rest and restitution’ was ‘green ground cover’, while factors such as ‘noise level’, ‘tables’, ‘views outside the park’, and ‘playgrounds’ were negatively correlated with ‘rest and restitution’. |

| Steele et al., 2019 [22] | Canada | Park users; and M + F; | Random sample; n = 213 (197 onsite questionnaires + 16 interviews) | Onsite questionnaire (close-ended + open-ended) + onsite interview + observations; and real landscape (one pocket park) | SSQP; sound appropriateness scale; self-designed questionnaire for the assessment of mood; PRSS (fascination, being-away, and compatibility); and sound source identification and evaluation | Musikiosk significantly enhanced the mood of both users and non-users, with a particularly notable increase in mood among Musikiosk users. Musikiosk not only made people stay longer, but also attracted new visitors to the park and fostered a lasting sense of belonging and safety. Although the presence of Musikiosk did not significantly alter the restorative evaluation of the park’s soundscape, users reported new experiences of relaxation and restoration facilitated by Musikiosk. |

| Trudeau, Steele, and Guastavino, 2020 [34] | Canada | Park users; M + F; and age between 18 and 84 years (mean = 38 ± 15) | Random sample; n = 274 (M = 111, F = 154, other/no answer = 9) | Onsite questionnaire (close-ended + open-ended) + measurement of pocket park features; and real landscape (one pocket park) | SSQP; sound level measurements; perceived loudness measurement; sound list; and PRSS (being-away) | Respondents perceived all three designs of the lightly audible small water features as pleasant and appropriate for their activities, offering an opportunity for respite. The presence of misters did not have a significant impact on how respondents rated their sense of being-away. |

| Chiesi and Costa, 2022 [21] | Italy | Park users; M + F; and age between 10 and 90 years | Random sample; n = 480 (430 onsite questionnaires + 50 interviews) | Observation + onsite interview + onsite questionnaire (close-ended + open-ended); and real landscape (10 pocket parks) | Self-designed interview and questionnaire for the measurement of users’ practices and restorative opportunities | Green spaces (natural sounds, human sounds, green plants, outdoor resting areas) had a positive impact on people’s health and well-being. |

| Lu et al., 2022 [18] | Japan | Park users; M + F; and age over 60 years | Random sample; n = 202 (M = 127, F = 75) | Onsite questionnaire (close-ended) + measurement of microclimate and pocket park features; and real landscape (three pocket parks) | Microclimate measurement (air temperature, relative humidity, global temperature, wind velocity, and PET); environmental feature recording (sky view factor, aspect ratio, boundary enclosure, green view index, colorfulness index, water feature, trail pavement condition, and bench quantity); ROS; and subjective vitality scores | A space with a high sky view factor correlated with greater psychological restoration for elderly individuals. Enhanced boundary enclosure and increased seating quantity were both positively associated with such restoration. The colorfulness index and gravel roads significantly positively contributed to the subjective vitality of older adults. PET was shown to negatively impact mental restoration in older adults in autumn. The presence of large areas of water decreased subjective vitality among elderly Japanese participants. The green view index showed an inverted U-shaped relationship with psychological restoration, with Restoration Outcome Scale (ROS) scores peaking at an index value of 0.4. |

| Wang et al., 2022 [35] | China | Park users; M + F; and above 18 years old | Random sample; n = 322 (M = 148, F = 174) | Onsite questionnaire (close-ended) + measurement of pocket park features; and real landscape (10 pocket parks) | MHI-5; eight domains from NEST (access, recreational facilities, amenities, aesthetics–natural features, aesthetics–non–natural features, in-civilities, significant natural features, and usability) | Usability, natural aesthetics, and a civilized environment improved mental health, while entertainment facilities in pocket parks negatively affected mental health. |

| Huang et al., 2023 [16] | China | University students; M + F; and mean age = 24.6 ± 3.2 | Random sample volunteers; n = 50 (M = 22, F = 28) | Questionnaire (close-ended) + measurement of physiological response indicators + measurement of pocket park features; and videos (10 pocket parks) | POMS; PRS (being away, extent, fascination, compatibility); environmental preference scale; PPG; EMG; EDA; SCL; HRV; site area of pocket park; site and shape of pocket park; and 12 park components from EAPRS (percentage paved, canopy density, green visibility, scenic beauty, spatial containment, wide field of vision, topographic changes, cultural elements, leisure facility, special vegetation, distributing space, and off-site interference) | The environmental features of pocket parks, such as larger site areas, higher scenic beauty, low paving ratios, open vistas, cultural elements, topographic variations, special vegetation, and distribution spaces, enhanced the psychological benefits for recreational users. Environments with low canopy density and high green visibility rates contributed to the suppression of negative emotions. Pocket parks with high canopy density and significant off-site disturbances were detrimental to the positive physiological responses of users, while those with high green visibility, aesthetic beauty, and unique vegetation were more likely to confer health benefits upon users. |

| Peng et al., 2023 [7] | China | College students who are in periods of examination or job hunting | No sampling method; n = 60 | Questionnaire (close-ended) + measurement of pocket park features; and photographs (25 pocket parks) | Self-designed questionnaire for the measurement of the restorative effect (restorative effect and environmental preferences); 14 landscape indicators (tree and shrub area, lawn area, water area, plant species, subject color, terrain, green ratio, hard-pavement area, surrounding-element, area of relaxation facilities, texture of relaxation facilities, area of activity places, and area of entertainment and fitness facilities) | Environments that people liked had a good restorative effect. Key environmental features that produced a restorative effect included naturalness, being away, fascination, and privacy. In terms of the restorative effect, tree and shrub area, water area, plant species, and green ratio were all positively correlated, while the surrounding element area and area of activity places were negatively correlated. |

| Yin et al., 2023 [36] | China | Park users; M + F; and age between 22 and 55 years | Random sample; n = 232 | Onsite questionnaire (close-ended) + measurement of pocket park features; and real landscape (10 pocket parks) | RCS (being-away, extent, fascination, and compatibility); and percentage of 11 landscape indicators (pavement, landscape constructions, fence, vegetation, decorative lamp, signage, terrain, sky, person, rider, and surrounding vehicles) in relation to the total image | Four landscape features, including vegetation, terrain, decorative lamps, and pavement, provided users with restorative experiences. The presence of others impeded restoration by reducing feelings of being away, fascination, and compatibility, while riders and surrounding vehicles negatively affected environmental fascination and compatibility. |

| Naghibi, Farrokhi, and Faizi, 2024 [25] | Iran | Urban residents; M + F; and mean age = 22.84 ± 1.5 | Random sample volunteers; n = 25 (M = 15, F = 18) | Questionnaire (close-ended) + measurement of physiological response indicator; and images (five pocket parks) | EEG and POMS | Under-bridge spaces with naturalistic features could alleviate stress, enhance creativity and clarity of thought, improve well-being, and accelerate healing. Tunnel vision might offer an escape from urban compression and provide a peaceful space for urban residents. |

| Wang et al., 2024 [20] | China | University students; and M + F | Random sample volunteers; n = 167 (M = 86, F = 81) | Questionnaire (close-ended) + measurement of pocket park spatial and soundscape characteristics; and spatial abstraction model (12 office-type pocket parks) | PRSS (fascination, being-away-to, being-away-from, compatibility, and coherency); location, sizes, and visual landscape features of the pocket parks; environmental sound pressure level; composition of soundscape elements; and perception evaluation of soundscape | Among the soundscape restoration features in office-type pocket parks, “attractiveness” significantly outweighed “coordination” and “disengagement”. Birdsong and small fountain sounds had substantial restorative effects. The use of birdsongs in green and gray spaces as well as the sound of small fountains in blue spaces contributed to the restoration of the environment. The design of a restoring soundscape for office-type pocket parks with high spatial enclosures should focus on reducing the adverse effects of negative sounds. The greater the enclosure in office-type pocket parks, the less restorative the soundscape will be. |

| Xu et al., 2024 [37] | China | Undergraduate and graduate students; M + F; and age between 19 and 25 years | Random sample volunteers; n = 80 (M = 40, F = 40) | Onsite questionnaire (close-ended) + measurement of physiological response indicators + measurement of pocket park features; and real landscape (three pocket parks) | BP; HR;HRV; FS-14; VAS; 10 landscape indicators (plant color, vegetation coverage, plant species, spatial privacy, comfort of rest facilities, orientation of rest facilities, number of activity areas, types of recreational fitness facilities, quantity of recreational fitness facilities, and surrounding environmental cleanliness); and PRS (being-away, extent, fascination, and compatibility) | Plant color, vegetation coverage, comfort of rest facilities, and plant species were found to be more predictive of the recovery capacity from mental fatigue, while factors such as surrounding environmental cleanliness and spatial privacy did not show significant predictive effects. In terms of mental fatigue recovery, vegetation coverage was more important than plant color or species. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Feng, L.; Yan, A. Exploring Features of Pocket Parks That Related to Restorative Effects: A Systematic Review. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9080326

Zhang Y, Feng L, Yan A. Exploring Features of Pocket Parks That Related to Restorative Effects: A Systematic Review. Urban Science. 2025; 9(8):326. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9080326

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yawei, Lu Feng, and Aibin Yan. 2025. "Exploring Features of Pocket Parks That Related to Restorative Effects: A Systematic Review" Urban Science 9, no. 8: 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9080326

APA StyleZhang, Y., Feng, L., & Yan, A. (2025). Exploring Features of Pocket Parks That Related to Restorative Effects: A Systematic Review. Urban Science, 9(8), 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9080326