Abstract

As contemporary role models in the digital space, influencers are seen as one of the actors able to engage users with their posts, which also affects the image of a destination, and thus contributes to the co-creation process. At the same time, less information seems to be available on what elements influencers use and to what extent they influence the engagement of their followers. Through content analysis, the contributions to this image have been analysed by comparing different types of destinations and influencers. The results show that natural resources and undiscovered destinations generate a high level of engagement, a key element for co-creation. In addition, influencers, as the ambassadors of destinations, can have a positive impact on their sustainable development.

1. Introduction

The paradigm shift in the early 2000s involved a move from a supplier-centred to a customer-centred market [1,2]. This shift is reflected in approaches such as service-dominant logic, which describes the creation of value through the interactions of different actors [3]. This is also the case for co-creation, which involves the inclusion of public input into the design of products or services [4,5]. This involvement of customers can lead to greater personalization, satisfaction, loyalty and innovation, and thus to the creation of long-term shared value [6,7].

Advancing technological development, including the internet and social media, has opened up a digital space [8] that acts as a catalyst for co-creation. More and more people spend their time online and can therefore be reached almost anywhere, anytime [9]. Companies use this direct accessibility for their marketing purposes [10], so it is not surprising that the profiles of companies as well as the profiles of individuals can be found on different platforms [11]. Also represented here are destinations, whose image is marketed through their digital presence [12], which in turn is fundamental for their differentiation [13], tourists’ travel decisions [14], long-term competitiveness [15,16,17] and destination development [18]. In this context, research efforts focus on a wide variety of destination types, including urban destinations [19,20]. In the case of urban destinations, which have a wide range of facets, it has been shown that, among other things, emotional attachment and solidarity with a city are decisive factors for the destination image, so this emotional component seems even more important for published content and the corresponding differentiation in a market full of offers [21].

Users of digital platforms can interact with destination management organisations’ (DMOs) content in the form of ‘likes’ and comments [22]. These interactions are an important source of information for DMOs in relation to various metadata [23], as they provide direct insight into tourists’ experiences, opinions and ratings of the destination [24], which in turn can serve as a basis for collaborative [25] and sustainable [18] development. For this reason, companies are interested in users interacting with their content as frequently and for as long as possible, which is why destinations are increasingly relying on social media influencers [26,27]. Due to their apparent authenticity and accessibility, they have become contemporary role models [28,29] and can therefore lead to a high level of engagement [30] and to co-creation.

First, efforts in relation to engagement and co-creation in the context of destination image can be found in the academic literature:

Cheung et al. [31] address the question of which elements of social media marketing positively contribute to engagement and thus to co-creation. The results of their research show that entertainment, personalization and electronic word of mouth (eWOM) contribute to this process.

In their work, Jakkola and Alexander [32] examine, among other things, which elements are among the key drivers that motivate customers to engage within the multi-stakeholder service system. They conclude that the feeling of empowerment, together with the feeling of having some control over the company’s processes, are among the main motives for engagement.

Glyptou [33] analyses the extent to which crises affect willingness to engage, co-creation, destination image and travel intention. Here it is shown that, in the face of crises, it is important to encourage potential visitors to travel to a destination, as they focus on their own experiences and adventures once they arrive.

The existing literature shows that engagement is a determining factor for co-creation and the resulting destination image [34,35]. At the same time, technological advances offer new opportunities for co-creation in a digital space where influencers are seen to play an important role in creating targeted content and engaging and influencing other users, making them interesting actors for marketing, especially social media marketing [26,27]. Although they seem to be one of the most important contemporary actors, they seem to have received little attention in terms of engagement and co-creation in the context of destination branding. The aim of this research is therefore to better understand which elements used by these actors generate a high level of engagement and co-creation and what reactions they provoke in relation to different types of destinations. Therefore, the following research questions are posed:

- RQ1: What elements of destination image do influencers use in different types of tourism destinations?

- RQ2: Which elements of destination image generate high engagement?

- RQ3: Which elements of the destination image generate which reactions?

Content analysis will serve as the methodology because it can contribute to a deeper understanding of elements and processes [36] and conclusions can be drawn for research [37]. In addition, large volumes and diverse types of data (textual, visual and audio) can be analysed [38]. It allows for an in-depth understanding of what elements attract users and potential tourists and to what extent. At the same time, the choice of influencers‘ content as a research object offers the possibility to obtain the most authentic possible insight into users’ reactions, opinions and emotions. Furthermore, the elements used by influencers can be evaluated in terms of their impact and thus contribute to the operationalization of these elements.

From the analysis of the elements used by influencers, this research makes important contributions to the academic literature in the field of social media marketing and destination management. In this way, engagement processes and the resulting co-creation could be optimised and thus contribute to more effective destination marketing.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Image of Tourist Destinations as a Key Factor

Tourism destinations have been one of the main objects of research during the last few decades [39,40,41,42]. They are understood as holistic tourism systems within a geographical area, which aim to contribute to the satisfaction of their visitors through their products and services [43]. There are several categorizations to differentiate the different types of destination, with one of the models being Buhalis’ differentiation [44] where the author differentiates tourist destinations according to the criterion of their main attraction and distinguishes between urban, coastal, mountain, rural, unexplored and exotic destinations [44]. These characteristic attractions of a destination can be of different natures. They can be related to natural resources, to the general and tourist infrastructure, but also to the environment of a place. According to Beerli Martín [45], these dimensions contribute to and shape the image of a tourist destination.

Destination image has been mentioned since the early 1970s and since then various definitions can be found in the academic literature [46,47]. Here, the aspect of geographical distance is adopted and the destination image is the idea that an individual has of a place where he or she does not usually reside [46]. There are also definitions that adopt the cognitive aspect of destination image [48]. Over time, the destination image is the set of mental representations in the form of ideas, feelings and impressions that an individual harbours towards a destination [49,50] and it is emerging that this image can sequentially contain cognitive, affective and conative components [51,52].

Based on these definitions, it is understood that the destination image is a set of ideas and that it is an intangible element of a destination [53]. This intangible construct can not only arise from information published by the destinations themselves but should be understood as a mosaic that can be composed of many different sources, such as the media (television, radio, etc.), but also the stories of acquaintances. Consequently, this means that the image of a destination can be formed in the mind of a person without having visited the destination [52].

In a market of tourist attractions, the image of a destination thus takes on the role of a differentiating factor [13] and can therefore influence the perception and travel decision of potential tourists and thus plays a key role [54].

2.2. Engagement and Co-Creation as a Contemporary Base

With the paradigm shift at the beginning of the century, the previously supplier-centric market is now customer-centric, with the customer now having the power of choice in an oversupplied market. This is seen, among other things, in the design of products and services, where the focus is no longer on production and delivery, but on an exchange between the different stakeholders, which is expected to lead to the creation of synergies [1,2,3].

This development can also be observed in marketing. The classic marketing mix for marketing products, consisting of the classic 4 Ps (product, price, place, promotion), has been expanded over time to include, in the context of marketing services, additional elements such as people, process and physical evidence to adapt to the now relation-oriented marketing [1,55].

As a result, co-creation, which aims to achieve collaborative value creation by involving the population in product and/or service design processes, has developed and made its way into the academic literature [4,5]. In relation to destination image, public entities such as residents and tourists and, in addition, influencers can be involved [56,57]. Due to this collaborative creation, products and services can achieve a higher degree of personalisation and thus also customer satisfaction, so this can lead to long-term value creation [6].

Zhang [58] explains that co-creation also offers scope for innovation, which can be further enhanced by new technological possibilities. He also stresses that this collaborative process is a business-to-customer relationship in which the literature has mainly focused on positive outcomes, although negative eventualities, such as co-construction, must also be considered.

One of the determining factors for the development of the research seems to be the commitment of the customer in the co-creation process. Engagement here means not only participation and involvement, but also the interaction between customers and a specific object of engagement, such as a brand [59]. On this basis, important information about (potential) customers can be collected [23], which in turn can contribute to the co-creative development of the resulting processes [25]. When applied to destination image, this could mean the active involvement of (potential) tourists in the process of destination image creation.

2.3. Influencers as Ambassadors in the Digital Age

Technological advances have created digital spaces [8], which act as catalysts for co-creation. One of these digital spaces is social networks, where users spend much of their time, with Instagram being the most popular platform [9]. On this platform, users’ private profiles can be found, as well as the profiles of companies [11], including destination management organisations (DMOs) that use it to promote the image of their destination [12].

The platforms offer various opportunities for engagement: users can engage in direct interaction with the DMOs by liking and commenting on their posts [22]. This data, in turn, can be obtained and used from these digital spaces [23] and thus contribute to the co-creative development [25] of the destination’s image, among other things.

With the advent of social media, new actors have also emerged in this network: influencers. They are considered modern role models who appear particularly authentic and trustworthy to their followers due to their apparent accessibility [28,29], which in turn can make them interesting for marketing.

While influencers were initially considered role models in the context of fashion, they have become role models in all kinds of fields, including tourism [26]. In this case, it is assumed that influencers can reinforce the image that social media users have of a destination and thus encourage them to visit it [60]. This may be because influencers, with their individual and seemingly authentic appearance, contribute to bridging the trust gap among their followers and become catalysts for bookings [35]. Here, they can act in terms of the marketing mix [1,55], particularly regarding promotion and people, as they can reach many potential customers and serve the relationship component due to their parasocial relationship with their users. In this way, influencers can on the one hand contribute to a high level of engagement between their followers and a destination [30] and on the other hand become ambassadors of the destination [61].

One tool for this is the algorithms used by the platforms. These are pre-programmed rules that are based on the preferences of users and, among other things, those of their contacts, and determine what content is displayed to users and, as a result, who can achieve greater visibility and thus reach and engagement [62]. They are therefore also referred to as the rules of a game that can be learned through experience, within which influencers can focus on authentic interaction or visibility optimising strategies and thus operationalise them. In relation to influencers, the algorithms also lead to user gratification, as they are shown exactly the content that is optimally tailored to them. At the same time, this leads to users seeing it as normal to follow influencers and purchase the items they promote, which in turn provides insight into the importance of algorithms and their use by influencers [63,64].

Due to the possibility of using algorithms for monetary purposes, various challenges have arisen, some of which are ethical in nature. For example, a lack of transparency in publications within the context of paid partnerships can lead to unrealistic lifestyles being promoted and vulnerable groups being exploited, which is why the authors, in addition to calling for clear regulations at the legal level, also appeal directly to influencers and advocate honest communication and clear labelling to maintain their credibility and the trust of their community and thus be able to influence their followers in an ethically correct manner [65,66].

Kilipiri Papaioannou [67] point out that influencers could use their ability to influence their followers in a positive way to promote less visited destinations, thereby contributing to a more balanced visitor flow and thus to the positive development of tourism. Applied to a wide range of destination types, this could counteract mass tourism in urban metropolises and increase distribution to surrounding areas, which in turn could benefit from these visitor numbers. In addition, more sustainability-conscious tourists seeking authentic experiences could be attracted, which in turn would incorporate local actors into the tourism value chain, benefiting all local stakeholders directly and indirectly [20]. In this way, influencers could contribute to environmental protection by promoting natural resources, which in turn has a direct and indirect positive impact on the local economy and thus on society in the long term, thereby contributing to the sustainable development of destinations. In this sense, previous research shows that influencers should create content that encourages interaction, as this can lead to visibility on the one hand, but also to the strengthening of a sense of community and belonging, which can turn followers into customers and, in the long run, into ambassadors as well [35].

Femenia-Serra Gretzel [26] highlight that influencers have two decisive characteristics for marketing. First, they already have a following that includes specific demographic groups. At the same time, influencers have the ability to present themselves well, which can have an impact on destination presentation.

This representation of the destination could counteract the problems underlying place marketing and branding, such as politicisation, imbalance in the distribution of power, and a lack of participation and identification of the local population with the identity of the destination, which, due to its scope, extends beyond various levels of government and beyond the economic sphere [68,69].

Place marketing refers to the processes by which territorial units such as cities, regions or countries are marketed using marketing principles and techniques, including the development of tourism products to attract potential tourists [70].

Part of place marketing, although also used as a synonym, is place branding, which refers to control processes at the political level and thus affects the identity of a territorial unit [71]. Within this framework, a wide variety of tangible and intangible measures are implemented to attract specific target groups to serve interests such as economic growth and tourism development. This is achieved, among other things, by involving various stakeholders and is intended to create a positive and coherent overall impression of a destination among the respective target groups [68].

Part of these efforts involve advertising measures in the form of social media marketing by influencers. Here, these actors can contribute to the positive overall impression of a destination through their posts and thus contribute to the goal of place branding, attracting potential tourists through promotion, which is why social media marketing by influencers has become an integral part of place branding and place marketing [72,73].

To counteract the possible negative effects of place marketing and branding, DMOs and influencers should therefore focus on an authentic and diverse representation of the destination, based on transparent and participatory social media marketing to build a place brand, which can contribute to a positive overall impression among the respective target groups and the competitiveness of the destination [68,69].

According to the authors, this can break down the stereotypes of a destination or direct visitors from overcrowded areas to previously less travelled destinations. In this way, influencers become actors capable of channelling and disseminating a destination’s message appropriately. Furthermore, it is evident that the feeling of empowerment, together with the feeling of having some control over the company’s processes [32], as well as entertainment, personalisation and eWOM [31] contribute to user engagement on social networks.

While the literature recognises the key role of influencers as contemporary role models and potential destination (image) ambassadors [61] through their ability to influence the perceived image of potential tourists [74], information on the elements they should use to do so remains scarce. Backaler [75] stresses that, in practice, both the expertise and the appropriate tools to carry out proper and successful influencer marketing are often lacking. Bastrygina Lim [35] stress that effective influencer marketing in the dynamic world of social media requires an agile and responsive system that adapts to current trends and developments.

Therefore, the aim of this research is to analyse and extract the most impactful elements for engagement and subsequent co-creation in the context of destination image. This, in turn, can contribute to the operationalisation and thus effective marketing by influencers in cooperation with DMOs.

3. Materials and Methods

In order to gain a deeper understanding of influencers’ engagement and co-creation in relation to the image of tourism destinations, content analysis was used as the main methodology. This technique allows for a structured examination of various types of content in order to gain a detailed understanding of both textual and audio-visual elements [36,38].

In the present study, publications by influencers were analysed in the second half of 2024, distinguishing between micro-influencers, macro-influencers and mega-influencers, in accordance with the classification proposed by Conde and Casais [76]. The inclusion criteria are the number of followers and the public visibility of the profile. The platform chosen for the analysis is Instagram, due to its popularity and the possibility of sharing both visual and textual content [9].

The search of this platform focuses on publications related to different types of tourist destinations. For its classification, the typology proposed by Buhalis [44] is adapted, who distinguishes six types of destinations according to their main attraction: urban, coastal, mountain, rural, undiscovered and exotic exclusive. This categorisation has two advantages: on the one hand, it allows for a greater diversity of results and facilitates generalisation; on the other hand, it allows for more specific comparisons between the different types of destinations. Buhalis [44] defines tourist destinations as geographical units recognised by visitors, managed through planning and marketing actions within a legal framework. The selection was made based on the main attractions of the destination and its presence in the academic literature, or, in the case of unknown destinations, based on visitor numbers, resulting in the following list:

- Urban destination: New York, noted for its extensive cultural, leisure and shopping offerings, is widely cited in the literature as a cosmopolitan icon [77,78,79], and is adopted here as the urban case study.

- Coastal destination: The Amalfi Coast in Italy is a recurring example in tourism research for its cultural and natural resources [80,81], and is selected as the coastal destination case study.

- Mountain destination: The Alps, also mentioned by Buhalis [44] and extensively addressed in previous research [82,83], are chosen as the representative of this category.

- Rural destination: Iceland, with a strong agricultural component and a gradual adaptation to tourism [84], is considered a suitable case study of a rural destination.

- Undiscovered destination: Tuvalu in the Pacific received just over 3000 visitors in 2023 [85], making it a suitable example of an unexplored destination.

- Exotic exclusive destination: Fiji, already present in academic studies as an exotic destination [86], is incorporated as the representative case study in this category.

The Instagram search bar was used to search for publications. For each destination, the first three posts from the Instagram search were selected, prioritising the first image in cases of multiple posts. Posts that contained commercial collaborations or competitions, identified as such by being marked or mentioned in the description, were excluded. In total, 52 posts were collected, with 3 images per influencer type and destination, except for Tuvalu and Fiji, where only 2 mega-influencer posts were found.

The analysis of these posts focused on the elements present in the images, using, as a reference, the dimensions of the perceived image of the destination proposed by Beerli and Martin [45]: natural resources, general infrastructure, tourism infrastructure, tourism leisure and recreation, culture, history and art, political and economic factors, natural environment, social environment and atmosphere of place. Natural resources include climate, beaches, landscape and biodiversity. The authors refer to general infrastructure as transport, health, telecommunications and development. Tourist infrastructure, on the other hand, refers to tourist facilities such as accommodation, restaurants and information centres. Tourist leisure and recreation includes leisure and sports facilities such as parks, nightlife and shopping. Culture, history and art represents cultural attractions, traditions and lifestyles. Political and economic factors refer to political stability, security, the economy and price levels. The natural environment describes, among other things, environmental quality, cleanliness and traffic congestion. The social environment refers to the hospitality of the locals, social conditions and communication. The atmosphere of the place describes the general impression of a destination, such as whether the place is perceived as relaxed, family-friendly or exciting. Given the focus on influencers, an additional dimension called ‘influencer’ was incorporated, which considers aspects such as their presence and interaction in the publication.

Analysing these elements can therefore help us to gain an understanding of which elements generate particularly high engagement and, as a result, trigger co-creation. This knowledge can in turn help to show which resources can be valorised and thus underline that they are worth protecting. In the case of natural resources, this could have a positive impact on the environment. Furthermore, knowing which elements are particularly popular with followers could facilitate cooperation between influencers and DMOs, which in turn could bring economic benefits due to more targeted work. Both factors can in turn have a positive impact on the quality of life of residents, so that knowledge relating to the attributes described can have an overall positive effect on sustainable development.

Based on these dimensions, an analysis was carried out both quantitatively—through the number of ‘likes’ and comments—and qualitatively, focusing on cognitive, affective and, in part, conative elements. Afterwards, an overview of the results was created, differentiated by destination type and influencer type, which compared the results and categorised them as high, medium and low. For example, the number of codes at the affective level for micro, macro and mega influencers was compared, and the influencer type with the most codes was labelled ‘high’ at the affective level, while the influencer type with the fewest codes was labelled ‘low’.

To analyse the selected publications, the software Atlas.ti™25, which enables artificial intelligence-assisted analysis [87], was used. The use of this tool made it possible to analyse large amounts of data in a structured way. In addition, it allows for the coding of the elements of publications, the deepening of the subject matter, as well as the recognition of patterns and correlations and the deduction of possible causalities and interrelationships. Beyond this research, the approach used can be replicated with this tool, so that it can also serve as a basis for further elaborations [88].

This methodological approach has made it possible to obtain differentiated results in terms of engagement and co-creation, depending on the type of influencer and destination analysed, thus providing a more nuanced view of their influence on the construction of the tourism image.

4. Results

4.1. Results of the Image Analysis

The coding of the images according to the dimensions represented in the images, according to Beerli and Martin [45], yielded the following results (see Table 1):

Table 1.

Codes per dimensions according to Beerli and Martín [45] per destination and influencer type.

The results showed that, out of a total of 362 codes, by far the largest number of codings were found in the images of New York and the Amalfi Coast. These were followed by Iceland and the Alps, followed by Tuvalu and Fiji, in that order. The results of the analysis show that most of the codes are related to influencers. There are also a large number of codes related to the natural environment and natural resources, as well as to the atmosphere. The codes related to the social environment are in the centre of the field. The dimensions related to general infrastructure and tourism, as well as culture, history and art, contain fewer codes. The lowest number of codes corresponds to political and economic factors, as well as to tourist leisure and recreational activities.

With regard to the codes used by the type of influencer, the majority of the 362 total codes are found among macro-influencers, with 134 codes. Micro-influencers and mega-influencers follow shortly after with 116 and 112 codes, respectively. Furthermore, the results show that the distribution of codes for one dimension is relatively balanced when comparing the different types of influencers (see Table 1).

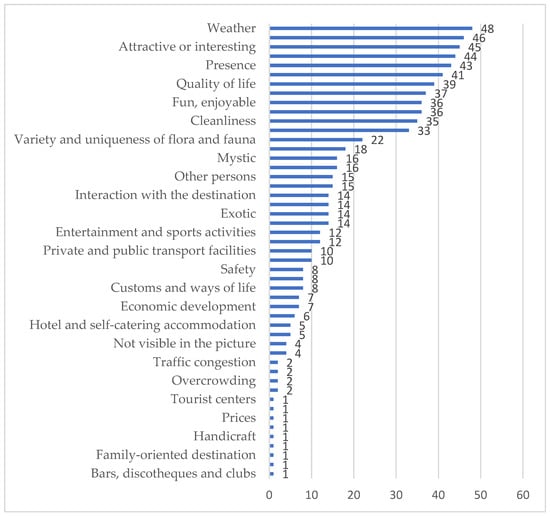

The breakdown of the attributes used in the different dimensions according to Beerli and Martin [45] shows that time comes first and can be seen in almost all photo posts. A similar thing happens with the visibility of influencers, who appear in almost every photo. In addition, the attributes of attractiveness, scenic beauty and quality of life of the respective destination are often found. In particular, relaxing and fun or pleasant can be found as atmospheric attributes. The lowest number of attributes is found in the tourist infrastructure, such as bars, discos and clubs, as well as in the general infrastructure (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Codes per dimension according to Beerli and Martín [45].

4.2. Results of the Reaction Analysis

The quantitative interaction, calculated based on the number of likes and comments on each post in relation to the number of followers and expressed both in absolute terms and as a percentage, yields the following results (see Table 2):

Table 2.

Engagement by likes and comments.

The mountain destination, the Alps, has the highest share with a like rate of just under 10%. It is followed shortly after by the Amalfi Coast with 8.8%, followed by New York with 7.7%. The exotic destination of Fiji and the undiscovered destination of Tuvalu lag far behind with 3.1% and 2.6%. The ‘like’ rate in relation to influencers shows that micro-influencers reach the highest values with just under 15%. This is followed by macro-influencers with just over 3%, followed by mega-influencers with just under 2%.

In terms of the comment rate, the results are significantly lower. Again, the Alps, as the mountain destination, have the highest share with 0.28%. This is followed by the urban destination New York with 0.19%, the rural destination Iceland with 0.17%, closely followed by the exotic destination Fiji with 0.16%. This is followed by the undiscovered destination of Tuvalu with 0.13% and the Amalfi Coast with 0.11%. In terms of comment rate, macro-influencers have the highest share with 1.3%, followed by micro-influencers with 0.4% and mega-influencers with 0.03%. The quantitative engagement calculated on the basis of the average number of likes and comments in relation to influencers from Table 2 can be summarised in the following table (see Table 3):

Table 3.

Relative engagement by destination and influencer type.

The results for the top ten themes show that users comment especially on the themes of admiration, beauty, compliments, location, love, nature, photography, travel, Tuvalu and wealth. In a comparison of the destinations, comments on New York contain the most codes on the different themes. The lowest number of codes is found for Fiji. It is noteworthy that the destination itself is a central theme in the comments on the destination Tuvalu. In a comparison of influencer types, the lowest number of topic codes in proportion to the number of followers is found among micro-influencers and the highest number of codes among mega-influencers.

In general, it can be seen that admiration and beauty are particularly frequently found as topics in response to the images posted. The situation is similar with the theme of love. Travel plays an important role for almost all of them (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Top 10 topics per destination and influencer type.

The top ten emotions expressed provide information about the feelings commenters have towards the destinations and influencers. They indicate that admiration, appreciation, concern, curiosity, excitement, frustration, gratitude, happiness, joy and love can be found in varying degrees across destinations and types of influencers. Comparing destinations, the most emotions are expressed towards Tuvalu. Iceland and the Alps follow closely behind. New York and Fiji place at the bottom. Overall, admiration and beauty are the top emotions for all destinations. Love and appreciation are among the most popular. Tuvalu shows a high level of curiosity and concern while Iceland also reflects a high level of happiness.

In terms of influencer types, it appears that macro-influencers are the most popular influencers. This is followed by mega-influencers and, at a considerable distance, micro-influencers. Here too, the focus is on admiration and emotion, followed by love and appreciation. The latter is proportionally very pronounced among micro-influencers. Compared with mega-influencers, macro-influencers have a particularly high proportion of happiness with a particularly low proportion of concern and vice versa (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Top 10 emotions per destination and influencer type.

The summary of the results provides an overview of the correlations between the factors relating to the engagement created by influencers in the context of the destination image (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Overview of the results.

In the case of the urban destination, New York, the results point to the fact that the dimensions represented in the images focus on influencers, the natural environment and natural resources. This leads to a comparatively moderate level of engagement in the form of ‘likes’ and comments. In the comments, there is a comparatively high diversity of topics on a cognitive level with a low emotionality on an affective level. In the coastal destination, Amalfi Coast, it is observed that the focus is also on influencers and the natural environment. This results in a high proportion of likes with a low proportion of comments. The comments show a low abundance of topics at the cognitive level with a moderate abundance at the affective level. The Alps as a mountain destination are represented by attributes of the influencers’ dimensions, but also of the natural environment, natural resources, social environment and the atmosphere of the place. This seems to lead to a high level of engagement, which manifests itself in a moderate variety of themes at the cognitive level and a high emotional intensity at the affective level. For the rural destination of Iceland, influencers, natural resources, the natural environment and the atmosphere of the place are also the most represented dimensions. This translates into a high level of engagement with a medium cognitive and high affective level. In the case of the undiscovered destination Tuvalu, the dimensions influencer, natural environment, the atmosphere of the place and general infrastructure are particularly represented, and a low level of engagement is observed, characterised by a moderate level of reaction at the cognitive level and a very high level of reaction at the affective level. Finally, it is observed that the exotic destination of Fiji is mainly represented by attributes from the influencer, place atmosphere, natural environment and natural resources dimensions. This tends to lead to a low level of engagement, which is characterised by a low level of cognitive and affective reactions.

These results allow us to understand the engagement generated by the publications according to the type of destination and influencer (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Engagement per destination and influencer type.

5. Discussion

The results show that, in most cases, influencers appear in the images and often occupy a central position. Elements related to nature and the environment are also frequently identified, as well as atmospheric attributes, while components directly linked to tourism and leisure are scarce or non-existent. Urban and coastal destinations have a higher concentration of visual attributes associated with the destination image compared with other categories. When comparing the different types of influencers, it can be seen that in all cases their figure is the main motif of the image. However, attributes related to the natural environment, natural resources and the atmosphere of the place are regularly identified. Macro-influencers stand out as having both a greater diversity and a higher density of attributes in their publications. Regarding Beerli and Martin’s attributes that shape the destination image [45], this may indicate that influencers create a destination image characterised by naturalness, authenticity and interaction in harmony with nature by presenting natural resources and conveying elements of positive affect.

From the analysis of engagement—measured by ‘likes’ and comments—certain dimensions were identified which generate greater interaction. In this sense, rural and mountain destinations obtain the highest levels of engagement, partly because in the corresponding images the presence of the influencer tends to be less prominent or absent, and natural elements take centre stage. In contrast, social attributes linked to culture, history, politics or economics appear marginal or non-existent. The latter are more frequently observed in exotic or little-explored destinations, which, however, register relatively low levels of engagement. A similar trend is evident among the different types of influencers: micro-influencers generate the highest degree of engagement, probably due to a focus more on the natural environment and less on themselves or the structural elements of the destination. In contrast, mega-influencers, who show a lower level of engagement, tend to include more attributes related to infrastructure or structural elements, while natural aspects are less prominent.

From a cognitive, affective and partly conative perspective, users’ reactions also allow relevant conclusions to be drawn. The comments and emotions expressed in relation to visual attributes reveal that beauty is a cross-cutting theme in all types of destination and influencer. In urban, coastal and exotic destinations, themes such as love, praise and admiration are frequently addressed. On an emotional level, predominant feelings such as admiration, emotion and affection towards influencers are identified. In their posts, rural and mountain destinations are associated with themes such as photography, travel and nature, and, in addition to the aforementioned feelings, happiness also appears frequently as an emotion expressed by users. This suggests that destinations characterised by a high proportion of natural attributes not only generate positive emotional reactions, but also inspire comments oriented towards the travel experience, which can be interpreted as a conative manifestation in the form of desire or intention to travel.

In the case of the underexplored destination, its appearance as one of the main themes in the comments stands out. It is possible to infer that unfamiliarity with the destination generates a high level of interest, which translates into significant engagement on the part of users, driven by emotions such as curiosity and excitement.

This is consistent with the existing literature, which shows the cognitive, affective and conative components of destination image and the importance of destination image as a construct of an individual before they have visited the destination as a differentiating factor [13,51,52,53].

Similar trends are observed when analysing influencer types. Cognitive reactions to micro- and macro-influencers are marked by themes such as beauty, praise and wanderlust. In the case of mega-influencers, comments on beauty, admiration and love predominate, and the most frequent emotional reactions are admiration and excitement. It is worth noting that macro-influencers generate the most intense emotional reactions, including explicit expressions of happiness. This allows us to infer that publications with a high content of natural resources encourage not only reflection on the destination, but also a positive emotional connection with it, thus contributing to the affective and conative construction of the image of the tourist destination.

This, in turn, allows conclusions to be drawn about the marketing mix [1,55]. The results show that the elements mentioned generate a high level of engagement, which in turn is significant for the promotion of a destination. Furthermore, it underscores the assumption that influencers, in their role as role models [26], can contribute to more users wanting to engage in nature-based tourism by showcasing natural resources, which in turn can contribute to the valorisation and protection of these elements. On an economic level, this can contribute to the creation of jobs for the local population, which in turn can improve the quality of life for the entire community at the destination and thus contribute to its sustainable development, which is in line with the relevant literature [20,35].

6. Conclusions

The aim of this article was to deepen the understanding of how images posted by influencers affect user engagement on social networks and, consequently, the co-creation processes and the perceived image of tourist destinations. Through a dual content analysis method, focusing on both the visual aspects of Instagram posts and the reactions generated by users, differentiated results were obtained by comparing different types of destinations and influencers. These findings provide new insights for both the academic literature and professional practice in tourism marketing.

It has been found that, when comparing different destinations, influencers primarily focus on elements that can be attributed to the natural environment, depicting them to convey the atmosphere of the destination.

The results indicate that the depiction of the influencer does not necessarily seem to be required for high engagement. Here, too, it is evident that the depiction of natural resources can generate increased engagement.

Based on these destinations, it was also possible to deduce that the natural elements could elicit positive affective and conative reactions. Beauty was identified in relation to the destination and admiration in relation to the influencer. Furthermore, curiosity and excitement were identified, which suggests that there is a certain willingness to travel, which in turn can be located on a conative level.

These results suggest that influencers can stimulate the engagement of social platform users by using certain attributes in their publications and at the same time contribute to a positive affective connection with a destination, so that they co-create its image in the digital space. The potential impact at the conative level can also bring these effects into the real world through the possible implementation in the form of users travelling to the destination.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

From a theoretical point of view, it seems that the natural and aesthetic elements of the publications, as well as the undiscovered destinations, elicit a particularly high level of engagement and serve as a key element for co-creation, whereas the tourism infrastructure and the historical–cultural and political–economic elements elicit a lower level of engagement. Influencers’ posts seem to contribute to the perceived image of the destination, but also to its co-creation through engagement, which is in line with the existing literature [25]. Moreover, the admiration that users feel for influencers goes hand in hand with their role as role models for their followers [28,29]. This highlights their role as ambassadors of a destination [61] and its image.

6.2. Practical Implications

On a practical level, influencers seem to be a key figure for destination promotion due to their role as role models and DMOs should rely on influencer marketing to reach target groups directly and engage them cognitively and emotionally, with macro-influencers seeming to elicit the highest level of affective responses. The integration of the destination’s natural resources can attract a nature-savvy target group [20] and contribute to the protection of natural resources, as well as to the diversion and distribution of visitors and thus to the sustainable development of destinations, which is in line with Kilipiri Papaioannou [67].

6.3. Limitations

Considering the limited number of images posted and the dynamism of the platform, the results should be considered a snapshot.

6.4. Future Research

Future research could focus on which natural elements encourage engagement. In addition, a comparative analysis of destinations in the same category would be interesting to obtain more differentiated results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.D.-P. and A.S.-T.; methodology, J.M.D.-P. and A.S.-T.; software, J.M.D.-P.; validation, J.M.D.-P. and A.S.-T.; formal analysis, J.M.D.-P.; investigation, J.M.D.-P. and A.S.-T.; resources, not applicable; data curation, J.M.D.-P.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.D.-P. and A.S.-T.; writing—review and editing, A.S.-T.; visualisation, J.M.D.-P.; supervision, A.S.-T.; project administration, A.S.-T.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used Atlas.ti [version 25.0.1.32924] for the purposes of data storage, data analysis and data coding. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AP | Atmosphere of the Place |

| CHA | Culture, History and Art |

| DMO | Destination Management Organisation |

| eWOM | Electronic Word of Mouth |

| GI | General Infrastructure |

| INF | Influencer |

| NE | Natural Environment |

| NRs | Natural Resources |

| PEFs | Political and Economic Factors |

| SE | Social Environment |

| TI | Tourism Infrastructure |

| TLR | Tourism, Leisure and Recreation |

References

- Gronroos, C. From Marketing Mix to Relationship Marketing: Towards a Paradigm Shift in Marketing. Asia-Aust. Mark. J. 1994, 2, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Petrick, J.F. Tourism Marketing in an Era of Paradigm Shift. J. Travel Res. 2008, 46, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.F.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing. J. Market. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandsen, T.; Honingh, M. Definitions of Co-Production and Co-Creation; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, S.P.; Supramaniam, S. Value co-creation research in tourism and hospitality management: A systematic literature review. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 58, 96–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaca, J.A.; Miguel, L.P. The Influence of Personalization on Consumer Satisfaction: Trends and Challenges; IGI Global: Hershey, PN, USA, 2024; pp. 256–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, I.S.; McKercher, B.; Cheung, C.; Law, R. Tourism and online photography. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datareportal. Digital 2024: Global Overview Report. 2024. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2024-global-overview-report (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Skinner, H.; Williams-Burnett, N.; Fallon, J. Exploring reality television and social media as mediating factors between destination identity and destination image. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 24, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baányai, E. The integration of social media into corporate processes. Soc. Econ. 2016, 38, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, S.; Page, S.J.; Buhalis, D. Social Media as a Destination Marketing Tool: Its Use by National Tourism Organizations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2012, 16, 211–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S. The relationship between destination images and sociodemographic and trip characteristics of international travellers. J. Vacat. Mark. 1997, 3, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talavera, A.S.; Darias, A.J.R.; Rodríguez, P.D.; Domínguez, Á.M.R. Innovación con compromisos. Retos en la renovación de la imagen en destinos turísticos maduros (Fuerteventura, Islas Canarias). In Destinos Turísticos Maduros Ante el Cambio: Reflexiones desde Canarias; Talavera, A.S., Martin, R.H., Eds.; Instituto de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales: La Laguna, Spain, 2010; pp. 137–160. [Google Scholar]

- Olívia, J.; Marques, G.S.; Ferreira, A.M.; Costa, C. Co-creation: The travel agencies’ new frontier. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2011, 1, 229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Graziano, T.; Albanese, V.E. Online Place Branding for Natural Heritage: Institutional Strategies and Users’ Perceptions of Mount Etna (Italy). Heritage 2020, 3, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Haro, M.A.; Martinez-Ruiz, M.P.; Martinez-Cañas, R.; Ruiz-Palomino, P. Benefits of Online Sources of Information in the Tourism Sector: The Key Role of Motivation to Co-Create. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2051–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberato, D.; Sousa, B.B.; Paiga, H.F.C.; Liberato, P. Exploring wine tourism and competitiveness trends: Insights from portuguese context. E-Rev. Estud. Intercult. 2023, 11, 1–34. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.22/22778 (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Pettersen-Sobczyk, M. Influencer Marketing in the Promotion of Cities and Regions. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2023, XXVI, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, M.; Vollero, A.; Vitale, P.; Siano, A. Urban and rural destinations on Instagram: Exploring the influencers’ role in #sustainabletourism. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 104915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, D.; Kaplanidou, K.; Apostolopoulou, A. Destination Image Components and Word-of-Mouth Intentions in Urban Tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2015, 42, 503–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinikainen, H.; Munnukka, J.; Maity, D.; Luoma-Aho, V. ‘You really are a great big sister’–parasocial relationships, credibility, and the moderating role of audience comments in influencer marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 2020, 36, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micera, R.; Crispino, R. Destination web reputation as “smart tool” for image building: The case analysis of Naples city-destination. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2017, 3, 406–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Monterrubio, N.; Huertas, A. The image of Barcelona in Online Travel Reviews during 2017 Catalan independence process. Commun. Soc. 2020, 33, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, J.M.; Ismail, H.; Lee, S. From desktop to destination: User-generated content platforms, co-created online experiences, destination image and satisfaction. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Femenia-Serra, F.; Gretzel, U. Influencer Marketing for Tourism Destinations: Lessons from a Mature Destination; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Veirman, M.; Cauberghe, V.; Hudders, L. Marketing through Instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. Int. J. Advert. 2017, 36, 798–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie-Carson, L.; Magor, T.; Benckendorff, P.; Hughes, K. All hype or the real deal? Investigating user engagement with virtual influencers in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2023, 99, 104779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. Influencers on Instagram: Antecedents and consequences of opinion leadership. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroudi, P.; Marvi, R.; Colmekcioglu, N. Antecedents and consequences of co-creation value with a resolution of complex P2P relationships. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 4355–4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.L.; Pires, G.; Iii, P.J.R.; Leung, W.K.; Chang, M.K. The role of social media elements in driving co-creation and engagement. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2021; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, E.; Alexander, M. The Role of Customer Engagement Behavior in Value Co-Creation: A Service System Perspective. J. Serv. Res. 2014, 17, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glyptou, K. Destination Image Co-creation in Times of Sustained Crisis. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2020, 18, 166–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Sánchez, P.P.; Correia, M.B.; Jambrino-Maldonado, C.; de las Heras-Pedrosa, C. Instagram as a Co-Creation Space for Tourist Destination Image-Building: Algarve and Costa del Sol Case Studies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastrygina, T.; Lim, W.M.; Jopp, R.; Weissmann, M.A. Unraveling the power of social media influencers: Qualitative insights into the role of Instagram influencers in the hospitality and tourism industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 58, 214–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, S. Content analysis: Concepts, methods and applications. Nurse Res. 1997, 4, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stemler, S. An overview of content analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2001, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, J. Encyclopedia of Tourism; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P.L. Perceived changes in holiday destinations. Ann. Tour. Res. 1982, 9, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Can. Geogr. Géographe Can. 1980, 24, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Recomendaciones Internacionales para Estadísticas de Turismo 2008; United Nations: Madrid, Spain; New York, NY, USA, 2010. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/publication/seriesm/seriesm_83rev1s.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Alcañiz, E.B.; Aulet, X.F.; Simo, L.A. Marketing de destinos turísticos: Análisis y estrategias de desarrollo. In Marketing de Destinos Turísticos: Análisis Y Estrategias de Desarrollo; ESIC Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D. Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli, A.; Martín, J.D. Factors influencing destination image. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 657–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.D. Image-A Factor in Tourism. Ph.D. Thesis, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, J.D. Image as a factor in tourism development. J. Travel Res. 1975, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. A Systems Model of the Tourist’s Destination Selection Decision Process with Particular Reference to the Role of Image and Perceived Constraints. (Volume I and II); Texas A&M University: College Station, TX, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Baloglu, S.; McCleary, K.W. A model of destination image formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 868–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. An Assessment of the Image of Mexico as a Vacation Destination and the Influence of Geographical Location Upon That Image. J. Travel Res. 1979, 17, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W.C. Tourism Development: Principles, Processes, and Policies; VanNostram Reinhold: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gartner, W.C. Image formation process. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1994, 2, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glosario de Términos de Turismo. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/es/glosario-terminos-turisticos (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Rodríguez, A.J.; Díaz, P.; Ruiz-Labourdette, D.; Pineda, F.D.; Schmitz, M.F.; Santana, A. Selection, design and dissemination of Fuerteventura’s projected tourism image (Canary Isles). WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2010, 130, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. Marketing Management, 15th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shoukat, M.H.; Shah, S.A.; Ali, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Mapping Stakeholder Role in Building Destination Image And Destination Brand: Mediating Role of Stakeholder Brand Engagement. Tour. Anal. 2022, 28, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De las Heras-Pedrosa, C.; Millan-Celis, E.; Iglesias-Sánchez, P.P.; Jambrino-Maldonado, C. Importance of SocialMedia in the Image Formation of Tourist Destinations fromthe Stakeholders’ Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Tourist co-creation and tourism marketing outcomes: An inverted U-shaped relationship. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 166, 114105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Juric, B.; IIic, A. Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omeish, F.; Sharabati, A.-A.A.; Abuhashesh, M.; Al-Haddad, S.; Nasereddin, A.Y.; Alghizzawi, M.; Badran, O.N. The role of social media influencers in shaping destination image and intention to visit Jordan: The moderating impact of social media usage intensity. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2024, 8, 1701–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, F. Destination branding through social media: Juxtaposition of foreign influencer’s narratives and state’s presentation on the event of Pakistan Tourism Summit 2019. Qual. Mark. Res. 2023, 26, 428–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, S. Cuando los algoritmos son editores: Cómo las redes sociales, la IA y la desinformación alteran el consumo de noticias. Comun. Medios 2024, 33, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Xie, Q. Influencer Marketing in Web 3.0: How Algorithm-Related Influencer following Norms Affect Influencer Endorsement Effectiveness. J. Promot. Manag. 2023, 30, 444–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, K. Playing the visibility game: How digital influencers and algorithms negotiate influence on Instagram. New Media Soc. 2019, 21, 895–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroja, S. The Ethics of Influencer Marketing: Transparency and Disclosure. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Innov. Res. 2025, 12, h285–h293. [Google Scholar]

- Shekhar, P. Ethical Imperatives in Influencer Marketing: Navigating Transparency, Authenticity, and Consumer Trust. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2024, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilipiri, E.; Papaioannou, E.; Kotzaivazoglou, I. Social Media and Influencer Marketing for Promoting Sustainable Tourism Destinations: The Instagram Case. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucarelli, A. Place branding as urban policy: The (im)political place branding. Cities 2018, 80, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Kalandides, A. Rethinking the place brand: The interactive formation of place brands and the role of participatory place branding. Environ. Plan. A 2015, 47, 1368–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Gertner, D. Country as Brand, Product, and Beyond: A Place Marketing and Brand Management Perspective. J. Brand Manag. 2002, 9, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anholt, S. Definitions of place branding–Working towards a resolution. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2010, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U. Influencer Marketing in Travel and Tourism; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbuchea, A. Territorial Marketing based on Cultural Heritage. Manag. Mark. 2014, 12, 135–151. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, T.; Kumar, J.; Yee, W.F.; Hussin, S.R.; Neethiahnanthan, A.R. Camera to Compass: Unravelling the Impact of Travel Vlogs on Tourist Visit Intentions. Acad. Tur. 2024, 17, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backaler, J. Digital Influence: Unleash the Power of Influencer Marketing to Accelerate Your Global Business; Palgrave Macmillan Cham: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, R.; Casais, B. Micro, macro and mega-influencers on instagram: The power of persuasion via the parasocial relationship. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 158, 113708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Wong, J.; Brakewood, C. Use of Mobile Ticketing Data to Estimate an Origin–Destination Matrix for New York City Ferry Service. Transp. Res. Rec. 2016, 2544, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, W.J.; Jang, S. Destination image differences between visitors and non-visitors: A case of New York city. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 12, 642–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdić, K.; Čaušević, A.; Banda, A.; Božović, T. Perceptions about New York City as a Tourist Destination. S. Asia. J. Soc. Stud. Econ. 2024, 21, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscitelli, M. Preservation of paths for a sustainable tourism in the Amalfi coast. Int. J. Herit. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 1, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Clarizia, F.; De Santo, M. A Contextual Approach for Coastal Tourism and Cultural Heritage Enhancing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, M.L. Traditional Landscape and Mass Tourism in the Alps. Geogr. Rev. 1982, 72, 395–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.; Kastenholz, E.; Abrantes, J.L. Place attachment, destination image and impacts of tourism in mountain destinations. Anatolia 2013, 24, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Hall, C.M. Contested Development Paths and Rural communities: Sustainable Energy or Sustainable Tourism in Iceland? Sustainability 2019, 11, 3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Social Statistics Release. Migration. Visitor Arrivals. Available online: https://stats.gov.tv/news/social-statistics-release/ (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Cottrell, S.P.; Bricker, K.S. Service quality and its effect on customer loyalty among Incentive travel recipients: A comparison among Fiji and Kenya travelers. In Proceedings of the 6th World Leisure Congress: Leisure and Human Development, Bilbao, Spain, 3–7 July 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Atlas.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH.Atlas.ti. 2024, 24.2.0.32043. Available online: https://atlasti.com/?_gl=1*53bg7t*_up*MQ..*_ga*ODUwNDc1NzYyLjE3NTE2NDQxNDk.*_ga_K459D5HY8F*czE3NTE2NDQxNDgkbzEkZzEkdDE3NTE2NDQyNjIkajYwJGwwJGg4MTk5NzA5NjI (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research—Part 2: Handling Qualitative Data. Available online: https://atlasti.com/guides/qualitative-research-guide-part-2 (accessed on 22 September 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).