Unpacking Violence: Examining Socioeconomic, Psychological, and Genetic Drivers of Gun-Related Homicide and Potential Solutions

Abstract

1. Background

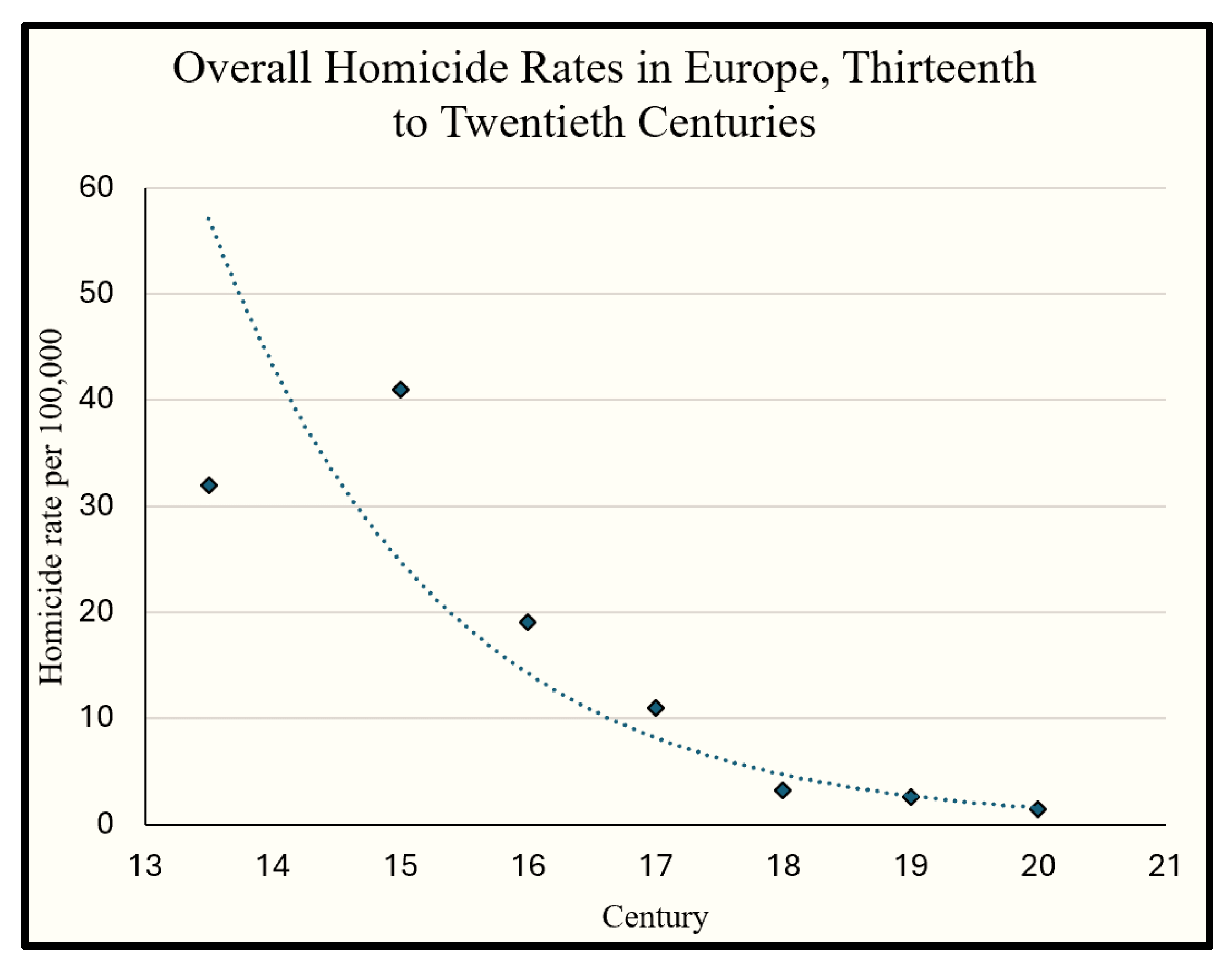

1.1. Historic Violence

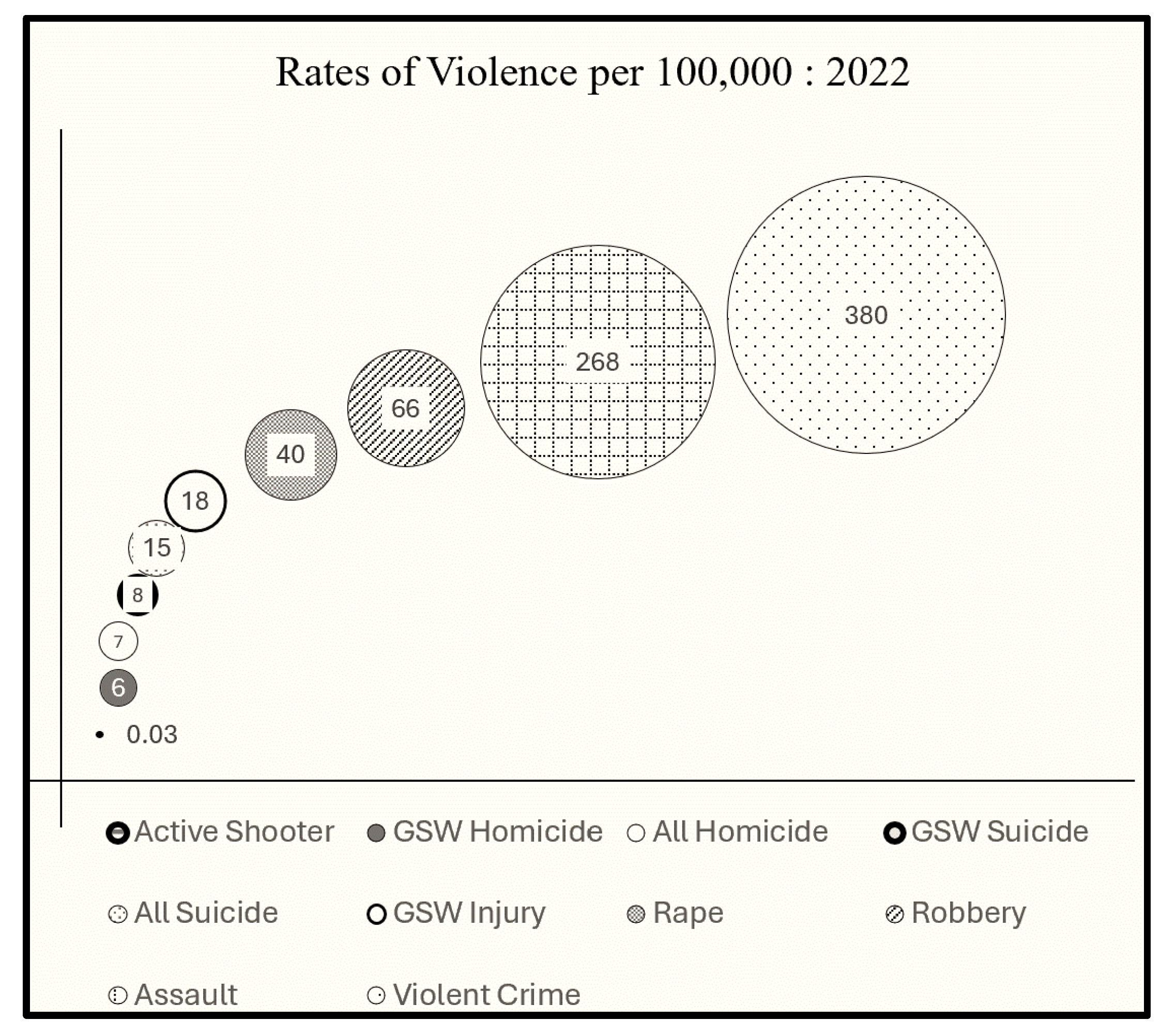

1.2. Violent Crime in the U.S.

1.3. Ethnicity of Homicide

1.4. Biological and Social Factors in Male Violence

1.5. The Origins of Violence—Childhood Trauma and Poverty

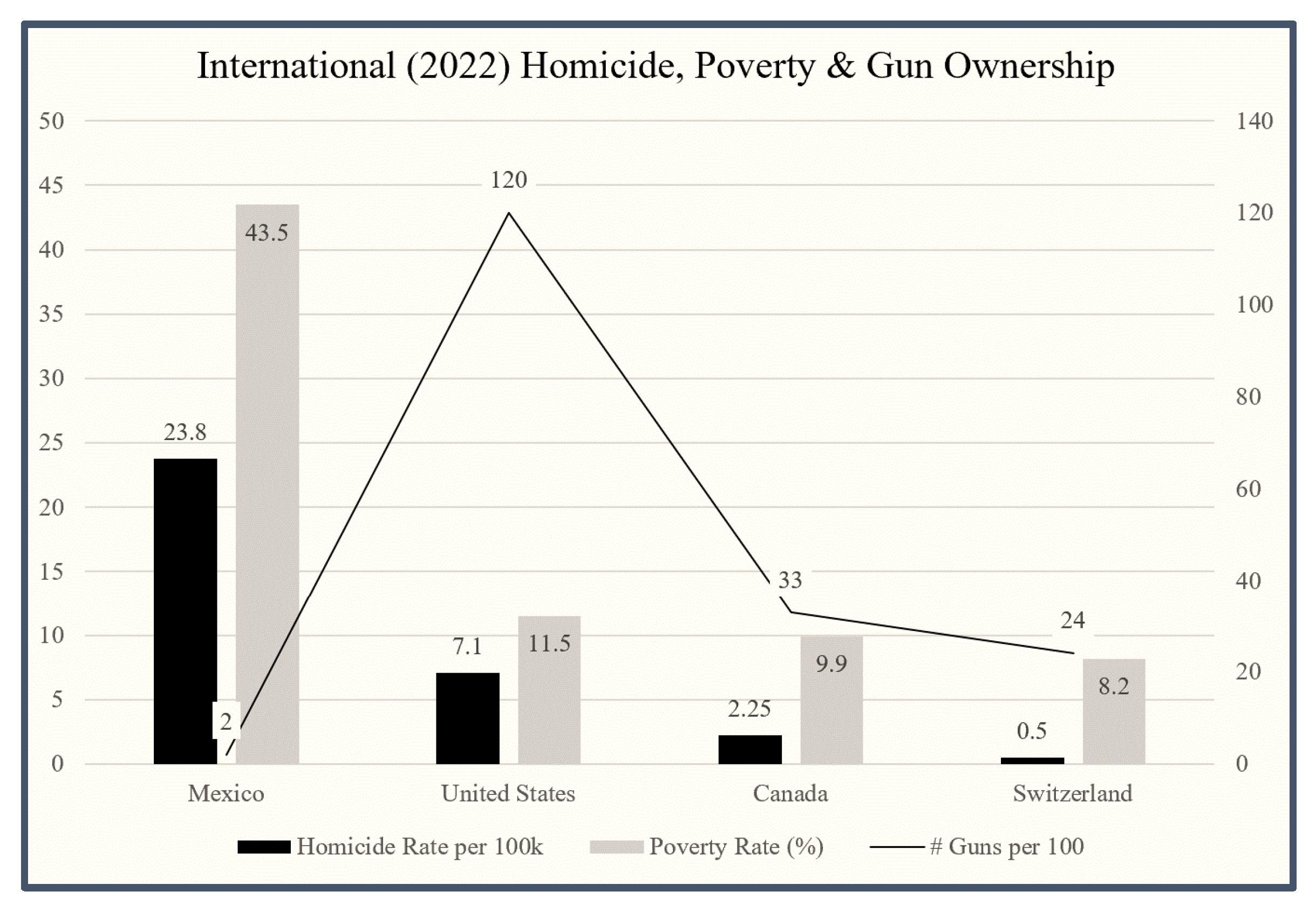

1.6. Gun Ownership, Violence, and Poverty: A Comparative Global Perspective

1.7. Sources of Crime Guns

1.8. Understanding Mass Shootings: Patterns, Causes, and Prevention Challenges

1.9. Modern Challenges in Gun Violence Prevention

2. Conclusions

Policy Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alfonseca, K. About 11,600 People Have Died in US Gun Violence so Far in 2024. ABC News Website. Published 12 April 2024. Available online: https://abcnews.go.com/US/gun-violence-claimed-lives-5000-people-2024/story?id=107262776 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Forbes Staff. U.S. Mass Shootings Hit 3-Year Low in Early 2024. Forbes Website. Published February 8, 2024. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/mollybohannon/2024/02/13/us-mass-shootings-hit-3-year-low-for-first-six-weeks-of-2024-but-deaths-remain-high/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Bohannon, J. Social science. Bold plan, uncertain future for gun violence research. Science 2013, 340, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treisman, R. The Surgeon General Declared Gun Violence a Public Health Crisis. What Does That do? Health 25 June 2024. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2024/06/25/nx-s1-5018625/surgeon-general-vivek-murthy-gun-violence-public-health-crisis (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death, 2018–2023, Single Race; CDC WONDER Online Database: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation Crime Data Explorer, FBI Uniform Crime Reporting Program; Federal Bureau of Investigation: Clarksburg, WV, USA, 2024.

- Census Table P1: Total Population; United States Census Bureau: Suitland-Silver Hill, MY, USA, 2022.

- Starr, M. Oxford Was the Murder Capital of Late Medieval England, And It Was All Because of Students. Humans September 28, 2023. Available online: https://www.sciencealert.com/oxford-was-the-murder-capital-of-late-medieval-england-and-it-was-all-because-of-students (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- Eisner, M. Long-term historical trends in violent crime. Crime Justice 2003, 30, 83–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spierenburg, P. Long-term trends in homicide: Theoretical reflections and Dutch evidence, fifteenth to twentieth centuries. In Civilization of Crime: Violence in Town and Country Since the Middle Ages; Johnson, E.A., Monkkonen, E.H., Eds.; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 1996; pp. 63–105. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, N. The Civilizing Process: Sociogenetic and Psychogenetic Investigations, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, N. The History of Manners: The Civilizing Process, Vol. 1; Jephcott, E.F.N., Translator; Urizen Books: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington, D.P. Predictors, Causes, and Correlates of Male Youth Violence. Crime Justice 1998, 24, 421–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfredson, M.R.; Hirschi, T. A General Theory of Crime; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Eisner, M. How to Reduce Homicide by 50% in the Next 30 Years. Igarapé Institute. August 2015. Available online: https://igarape.org.br/en/how-to-reduce-homicide-by-50-in-the-next-30-years/ (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Eisner, M.P. From Swords to Words: Does Macro-Level Change in Self-Control Predict Long-Term Variation in Levels of Homicide? Crime Justice 2014, 43, 65–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.; Smith, E.L. Homicide Trends in the United States, 1980–2008: Annual Rates for 2009 and 2010; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; NCJ 236018. Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/htus8008.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. About the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program; U.S. Department of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. Available online: https://ucr.fbi.gov/leoka/leoka-2010/aboutucrmain (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Rennison, C.M. Rape and Sexual Assault: Reporting to Police and Medical Attention, 1992–2000; Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, August 2002; NCJ 194530. Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/rsarp00.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Schleimer, J.P.; Rencken, C.A.; Miller, M.; Swanson, S.A.; Rowhani-Rahbar, A. Confounder selection in firearm policy research: A scoping review. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2025, 194, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. Expanded Homicide Data Table 6: Murder, Race and Sex of Victim by Race and Sex of Offender, 2011. In Crime in the United States, 2011; U.S. Department of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. Available online: https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2011/crime-in-the-u.s.-2011/tables/expanded-homicide-data-table-6 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Huhtaniemi, I. Chapter 8—Testosterone and Aggression, in Good and Bad Testosterone; Huhtaniemi, I., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, J. Testosterone and human aggression: An evaluation of the challenge hypothesis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2006, 30, 319–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabbs, J.M., Jr.; Jurkovic, G.J.; Frady, R.L. Salivary testosterone and cortisol among late adolescent male offenders. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1991, 19, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, A. Biosocial models of deviant behavior among male army veterans. Biol. Psychol. 1995, 41, 271–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, D. Chapter 13—Warriors and Worriers, in Our Genes, our Choices, 2nd ed.; Goldman, D., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Cao, C.; Wang, M.; Ji, L.; Cao, Y. Monoamine oxidase a (MAOA) and catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT) gene polymorphisms interact with maternal parenting in association with adolescent reactive aggression but not proactive aggression: Evidence of differential susceptibility. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 812–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetler, D.A.; Davis, C.; Leavitt, K.; Schriger, I.; Benson, K.; Bhakta, S.; Wang, L.C.; Oben, C.; Watters, M.; Haghnegahdar, T.; et al. Association of low-activity MAOA allelic variants with violent crime in incarcerated offenders. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2014, 58, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalaker, J. Poverty in the United States in 2022; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Report No. R48055. Available online: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R48055 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Pare, P.P.; Felson, R. Income inequality, poverty and crime across nations. Br. J. Sociol. 2014, 65, 434–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M. Concentrated Poverty, Race, and Homicide. Sociol. Q. 2000, 41, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, W. Poverty, Inequality, and City Homicide Rates. Criminology 2006, 22, 531–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Egger, P.H.; Guo, Y. Is poverty the mother of crime? Evidence from homicide rates in China. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanier, P.; Maguire-Jack, K.; Walsh, T.; Drake, B.; Hubel, G. Race and ethnic differences in early childhood maltreatment in the United States. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2014, 35, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Child Maltreatment 2020; Child Maltreatment; U.S. Department of Health & Human Services: Washington, DC, USA; Administration for Children and Families: Washington, DC, USA; Administration on Children, Youth and Families: Washington, DC, USA; Children’s Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Wolff, N.; Shi, J.; Siegel, J.A. Patterns of victimization among male and female inmates: Evidence of an enduring legacy. Violence Vict. 2009, 24, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, N.; Shi, J. Childhood and adult trauma experiences of incarcerated persons and their relationship to adult behavioral health problems and treatment. Electronic 2012, 9, 1660–4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widom, C. Child abuse, neglect and violent criminal behavior. Criminology 2006, 27, 251–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stensrud, R.; Gilbride, D.; Bruinekool, M. The Childhood to Prison Pipeline: Early Childhood Trauma as Reported by a Prison Population. Rehabil. Couns. Bull. 2018, 62, 003435521877484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, D.J.; Glaze, L.E. Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates; Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report; U.S. Department of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; Report No. NCJ 213600. Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/mental-health-problems-prison-and-jail-inmates (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Williams, A.; Evans, C.; Nehra, D.; Stadeli, K.M.; Bulger, E.M.; Dicker, R. Building community: Community engagement models for violence prevention. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2024, 9, e001483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SWITZERLAND CRIME STATISTICS—Switzerland—Homicide Rate. WORLD DATA ATLAS 24 May 2024. Available online: https://knoema.com/atlas/Switzerland/Homicide-rate#:~:text=In%202022%2C%20homicide%20rate%20for,per%20100%2C000%20population%20in%202022 (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Naghavi, M.; Marczak, L.B.; Kutz, M.; Shackelford, K.A.; Arora, M.; Miller-Petrie, M.; Aichour, M.T.E.; Akseer, N.; Al-Raddadi, R.M.; Alam, K.; et al. Global Mortality from Firearms, 1990–2016. JAMA 2018, 320, 792–814. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- The Long-Term Decline of Gun Ownership in America: 1973 to 2018; Violence Policy Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Estimating Global Civilian-Held Firearms Numbers. Global Firearms Holdings 2021. Available online: http://www.smallarmssurvey.org/fileadmin/docs/T-Briefing-Papers/SAS-BP-Civilian-Firearms-Numbers.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- America’s Complex Relationship with Guns. 2017America’s Complex Relationship with Guns. 2017. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2017/06/22/americas-complex-relationship-with-guns/ (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Crime and Violence Statistics (2018–2023). 2024. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Annual Crime Reports. Retrieved from. 2024. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/sspc (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Calderón, L.Y.; Heinle, K.; Kuckertz, R.E.; Rodríguez Ferreira, O.; Shirk, D.A. (Eds.) Organized Crime and Violence in Mexico: 2021 Special Report; Justice in Mexico, Department of Political Science & International Relations, University of San Diego: San Diego, CA, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-0-9988199-3-8. [Google Scholar]

- Shrider, E.A.; Creamer, J. Poverty in the United States: 2022. U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, P60-280. U.S. Government Publishing Office; September 2023. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2023/demo/p60-280.html (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Statistics Canada. Canada’s Official Poverty Dashboard of Indicators: Trends, May 2025. Catalogue no. 11-627-M2025019. Released 1 May 2025. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2025019-eng.htm (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Federal Statistical Office (Switzerland). Poverty in Switzerland: Income Poverty Based on the Social Subsistence Level–Trends and Group Differences. May 2025. Available online: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics/economic-social-situation-population/economic-and-social-situation-of-the-population/poverty-deprivation/poverty.html (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Mexico’s Poverty Rate Declines from 50% to 43.5% in Four Years as Remittances Almost Double. World News 2023, 10 August 2023. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/mexico-poverty-rate-declines-9fedcf8f40f62971beff2f9ffa47f190 (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. National Firearms Commerce and Trafficking Assessment (NFCTA): Crime Guns—Volume Two; U.S. Department of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.atf.gov/firearms/national-firearms-commerce-and-trafficking-assessment-nfcta-crime-guns-volume-two (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Rand, M.R. Guns and Crime: Handgun Victimization, Firearm Self-Defense, and Firearm Theft; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, April 1994; NCJ 147003. Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/guns-and-crime-handgun-victimization-firearm-self-defense-and-firearm-theft (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Cook, P.J.; Parker, S.T.; Pollack, H.A. Sources of guns to dangerous people: What we learn by asking them. Prev. Med. 2015, 79, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alper, M.; Glaze, L. Source and Use of Firearms Involved in Crimes: Survey of Prison Inmates, 2016; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; NCJ 251776. Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/source-and-use-firearms-involved-crimes-survey-prison-inmates-2016 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. Active Shooter Incidents 20-Year Review, 2000–2019; US Department of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- FBI. Active Shooter Incidents in the United States in 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/active-shooter-incidents-in-the-us-2022-042623.pdf/view (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Geller, L.B.; Booty, M.; Crifasi, C.K. The role of domestic violence in fatal mass shootings in the United States, 2014–2019. Inj. Epidemiol. 2021, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzl, J.M.; Piemonte, J.; McKay, T. Mental Illness, Mass Shootings, and the Future of Psychiatric Research into American Gun Violence. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2021, 29, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Association, A.P. One-Third of US Adults Say Fear of Mass Shootings Prevents Them from Going to Certain Places or Events; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, M.H. Mass murder, mental illness, and men. Violence Gend. 2015, 2, 51–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, J.; Simons, A.; Craun, S. A Study of the Pre-Attack Behaviors of Active Shooters in the United States Between 2000 and 2013; Federal Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Department of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/pre-attack-behaviors-of-active-shooters-in-us-2000-2013.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Gamache, K.; Platania, J.; Zaitchik, M. An examination of the individual and contextual characteristics associated with active shooter events. Open Access J. Forensic Psychol. 2015, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health Records in NICS Focus Group. Reporting Mental Health Records to the NICS Index; SEARCH: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.search.org/resources/mental-health-records-in-nics/ (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Kalesan, B.; Mobily, M.E.; Keiser, O.; Fagan, J.A.; Galea, S. Firearm legislation and firearm mortality in the USA: A cross-sectional, state-level study. Lancet 2016, 387, 1847–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, D.; Crifasi, C.K.; Vernick, J.S. Effects of the repeal of Missouri’s handgun purchaser licensing law on homicides. J. Urban Health. 2014, 91, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santaella-Tenorio, J.; Cerdá, M.; Villaveces, A.; Galea, S. What Do We Know About the Association Between Firearm Legislation and Firearm-Related Injuries? Epidemiol Rev. 2016, 38, 140–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, D.M.; Braga, A.A.; Piehl, A.M.; Waring, E.J. Reducing Gun Violence: The Boston Gun Project’s Operation Ceasefire; US Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs: Washington, DC, USA, 2001.

- Engel, R.S.; Tillyer, M.S.; Corsaro, N. reducing gang violence using focused deterrence: Evaluating the Cincinnati Initiative to Reduce Violence (CIRV). Justice Q. 2013, 30, 403–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, C.G.; Klein, H.J.; Wolff, K.T. Quasi-experimental designs for community-level public health violence reduction interventions: A case study in the challenges of selecting the counterfactual. J. Exp. Criminol. 2017, 13, 319–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Offender Ethnicity | % | per 100k | per 100k of That Race |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 22% | 1.19 | 2.0 |

| African American | 52% | 2.89 | 21.2 |

| Hispanic | 12% | 0.79 | 4.2 |

| Asian | 1% | 0.06 | 0.9 |

| American Indian | 1% | 0.07 | 5.1 |

| Unknown | 11% | 0.92 | NA |

| Victim Ethnicity | % | per 100k | per 100k of that Race |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 25% | 0.96 | 2.3 |

| African American | 56% | 3.14 | 23.1 |

| Hispanic | 14% | 0.01 | 5.1 |

| Asian | 1% | 0.08 | 1.2 |

| American Indian | 2% | 0.08 | 5.9 |

| Unknown | 2% | 0.14 | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Menezes, J.; Batra, K. Unpacking Violence: Examining Socioeconomic, Psychological, and Genetic Drivers of Gun-Related Homicide and Potential Solutions. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060190

Menezes J, Batra K. Unpacking Violence: Examining Socioeconomic, Psychological, and Genetic Drivers of Gun-Related Homicide and Potential Solutions. Urban Science. 2025; 9(6):190. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060190

Chicago/Turabian StyleMenezes, John, and Kavita Batra. 2025. "Unpacking Violence: Examining Socioeconomic, Psychological, and Genetic Drivers of Gun-Related Homicide and Potential Solutions" Urban Science 9, no. 6: 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060190

APA StyleMenezes, J., & Batra, K. (2025). Unpacking Violence: Examining Socioeconomic, Psychological, and Genetic Drivers of Gun-Related Homicide and Potential Solutions. Urban Science, 9(6), 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060190