Sustainable Tourism Practices and Challenges in the Santurbán Moorland, a Natural Reserve in Colombia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Theoretical Framework for Sustainable Tourism: Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) Criteria

Sustainable Tourism and Protected Areas Criteria

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Area and Data Collection

3.2. Survey Development

3.3. Interviews and Observations

3.4. Documentary Analysis

3.5. Sample Selection

3.6. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

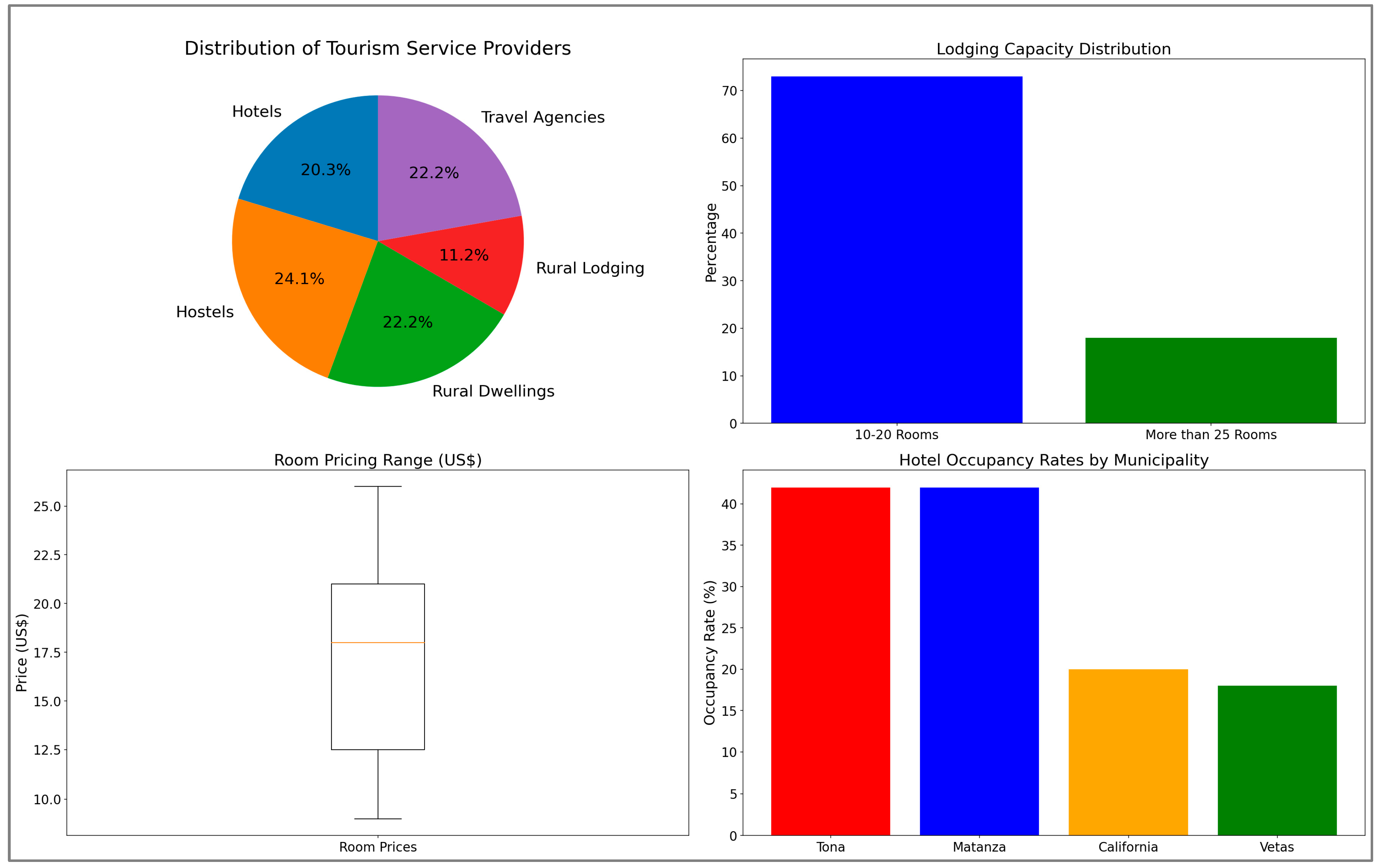

4.1. Provider Profile

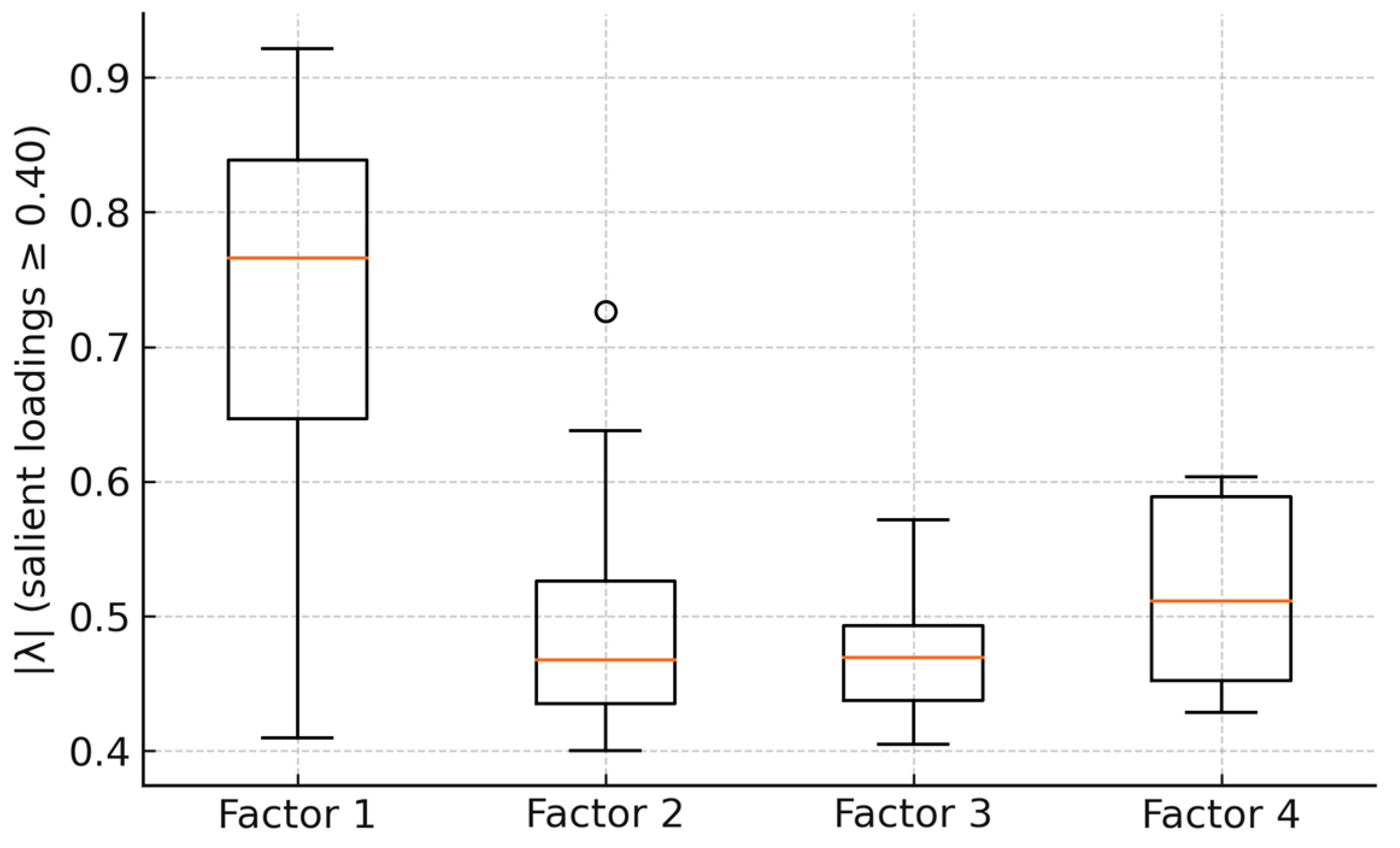

4.2. Statistical Analysis of Sustainability Factors

4.3. Sustainable Management

4.4. Conservation and Biodiversity

4.5. Social Impact and Participation

4.6. Waste Reduction and Efficiency

4.7. Overall Sustainability Practices

5. Discussion

5.1. Sustainable Management and Institutional Capacity

5.2. Environmental Conservation and Resource Use

5.3. Social Engagement and Community Integration

5.4. Waste Management and Infrastructure Gaps

5.5. Institutional Support and Sectoral Planning

5.6. Opportunities for Sustainable and Inclusive Tourism

6. Conclusions

7. Recommendations for Practice and Research

- Develop continuous training programs for tourism service providers (TSPs) on sustainability practices, in collaboration with local universities and research institutions.

- Design a guide of best practices specifically tailored to páramo ecosystems, offering clear guidelines to minimize environmental impact, conserve biodiversity, and promote responsible tourism.

- Promote public–private partnerships aimed at financing sustainable tourism infrastructure, including waste management systems, eco-friendly transportation, and renewable energy solutions.

- Implement fiscal incentives and financial benefits for TSPs that obtain recognized environmental certifications, encouraging greater adherence to sustainable tourism standards.

- Encourage longitudinal research initiatives to monitor and evaluate the long-term impacts of sustainable practices on ecosystem conservation and community development in the Santurbán Moorland.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FONTUR: Tourism Continues to Reactivate: In April, the Number of Nonresident Visitors Continued to Increase. 2023. Available online: https://fontur.com.co/en/node/1343?q=es%2Fcomunicados%2Fturismo-sigue-reactivandose-en-abril-continuo-el-aumento-de-numero-de-visitantes-no (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Rangel-Ch, J.O. La región paramuna y franja aledaña en Colombia. In Colombia Diversidad Biótica III: La Región de Vida Paramuna; Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Editorial Unibiblos: Bogotá, Colombia, 2000; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Marín, C.; Parra, S. Bitácora de flora. In Guía Visual de Plantas de Páramos de Colombia; Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt: Bogotá, Colombia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Flórez, M.F.; Linares, J.F.; Carrillo, E.; Mendes, F.M.; de Sousa, B. Proposal for a Framework to Develop Sustainable Tourism on the Santurbán Moor, Colombia, as an Alternative Source of Income between Environmental Sustainability and Mining. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Romero, A. ¿De quién es el páramo de Santurbán? Ancestralidad minera como narrativa de defensa del territorio en el municipio de Vetas, Santander. CS 2022, 36, 147–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism. Tourism Continues to Recover, as Confirmed by Figures from the Satellite Account to 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.mincit.gov.co/prensa/noticias/turismo/turismo-recuperandose-cifras-cuenta-satelite-2022 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Sarmiento Pinzón, C.E.; Sarmiento Giraldo, M.V.; León Moya, O.A.; Cadena Vargas, C.E.; Cuervo, Á.; Marín, C.; Jiménez, D.; Jaramillo, O.; Ramírez Aguilera, D.P.; Corzo, L. Aportes a la Delimitación del Páramo Mediante la Identificación de los Límites Inferiores del Ecosistema a Escala 1: 25.000 y Análisis del Sistema Social Asociado al Territorio: Complejo de Páramos Jurisdicciones Santurbán–Berlín Departamentos de Santander y Norte de Santander; Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt: Bogotá, Colombia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.E.; Doh, M.; Park, S.; Chon, J. Transformation planning of ecotourism systems to invigorate responsible tourism. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.; Masron, T.; Ahmad, A. Cultural heritage tourism in Malaysia: Issues and challenges. In SHS Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2014; p. 01059. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, X.; Yao, Y.; Li, J. Sociocultural impacts of tourism on residents of world cultural heritage sites in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, F.; Ziritt, G.; Silva, H. Sustainable Tourism: Perceptions, citizen welfare and local development. Venez. Manag. Mag. 2019, 24, 104–130. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Barriga, A. Tourism Management Perceptions in two Ecuadorian Biosphere Reserves: Galapagos and Sumaco. Investig. Geogr. 2017, 93, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Baloch, Q.B.; Shah, S.N.; Iqbal, N.; Sheeraz, M.; Asadullah, M.; Mahar, S.; Khan, A.U. Impact of tourism development upon environmental sustainability: A suggested framework for sustainable ecotourism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 5917–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, M.F.; Diop-Sall, F.; Leroux, E.; Vachon, M.-A. How do tourism sustainability and nature affinity affect social engagement propensity? The central roles of nature conservation attitude and personal tourist experience. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 200, 107503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chica, M.; Hernández, J.M.; Perc, M. Sustainability in tourism determined by an asymmetric game with mobility. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 355, 131662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P. Investigación sobre la huella ecológica del turismo: El caso de Langzhong en China. Obs. Medioambient. 2019, 22, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Rubio, K.; Delgado-Cruz, A.; Vargas-Martínez, E.E. Adoption of green technologies and their influence on environmental responsibility practices. Perceptions of hotel workers. Estud. Gerenciales 2021, 37, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R.B. Sustainability assessment: Basic components of a practical approach. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2006, 24, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa-Cruz, F.G.; López-Guzmán, T. Culture, tourism and world heritage sites. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 24, 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Gregori, P.E.M.; Martín, J.C.; Oyarce, F.; García, R.M. Turismo y patrimonio. El caso de Valparaíso (Chile) y el perfil del turista cultural. PASOS. Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2019, 17, 901–914. [Google Scholar]

- Yuedi, H.; Sanagustín-Fons, V.; Coronil, A.G.; Moseñe-Fierro, J.A. Analysis of tourism sustainability synthetic indicators. A case study of Aragon. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, M.A.; Isa, S.M.; Kiumarsi, S. Sustainable tourism practices and business performance from the tour operators’ perspectives. Anatolia 2021, 32, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondirad, A.; Tolkach, D.; King, B. Stakeholder collaboration as a major factor for sustainable ecotourism development in developing countries. Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera de la Barrera, J.; Martínez Buendía, J.M.; Martínez García, L. Software de sostenibilidad turística para el cumplimiento de la NTS colombiana (Tourism Sustainability Software for Compliance with the Colombian NTS). Tur. Soc. 2021, 28, 187–205. [Google Scholar]

- Balas, M.; Abson, D.J. Characterising and identifying gaps in sustainability assessments of tourism-a review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 43, 101004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Argota, M.A.; Anieva, M.B.M.; Olvera, J.V.B.; Pérez, M.B.B. Prácticas de turismo sostenible desde la gobernanza en las mipymes de Jardín (Colombia) y Tepotzotlán (México) en el período 2019-2021. Rev. CEA 2023, 9, e2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.C.; Veiga, C.; Santos, J.A.C.; Águas, P. Sustainability as a success factor for tourism destinations: A systematic literature review. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2022, 14, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council, G.S.T. GSTC Tour Operator Criteria; Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC): Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Toselli, C.; Takáts, A.; Traverso, L. Análisis de la sostenibilidad en emprendimientos turísticos ubicados en áreas rurales y naturales. Estudios de caso en la provincia de Entre Ríos, Argentina. Cuad. Tur. 2020, 45, 461–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Sahu, N.C.; Sahoo, D.; Yadav, D.K. Analysis of barriers to sustainable tourism management in a protected area: A case from India. Benchmarking Int. J. 2018, 25, 1956–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, L.J.; Weaver, D.B. Using residents’ perceptions research to inform planning and management for sustainable tourism: A study of the Gold Coast Schoolies Week, a contentious tourism event. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 660–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivars-Baidal, J.; Vera-Rebollo, J.F. Sostenibilidad y Resiliencia de los Destinos Turísticos Litorales: Apuntes Desde el Enfoque de los Destinos Inteligentes; Universitat de València: Valencia, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tejera, J. Una Alternativa de Turismo Sostenible y Comunitario Frente a la Megaminería en el Páramo de Santurbán. Alba Sud, 2015. Available online: https://www.albasud.org/noticia/es/820/una-alternativa-de-turismo-sostenible-y-comunitario-frente-a-la-megaminer-a-en-el-p-ramo-de-santurb-n (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Araos, F. Navigating in open waters: Tensions and agents in marine conservation in the Patagonia of Chile. Rev. De Estud. Soc. 2018, 64, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colparques. Santurbán Páramo Natural Reserve. Available online: http://www.colparques.net/SANTURBAN (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Guauque, C. Representaciones sociales del territorio en el Comité para la Defensa del Agua y el Páramo de Santurbán Colombia (2010–2017). Derecho Real. 2018, 16, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Villamizar, R.; Mejía-Jerez, A.; Acevedo-Tarazona, Á. Territorialidades y representaciones sociales superpuestas en la dicotomía agua vs. oro: El conflicto socioambiental por minería industrial en el páramo de Santurbán. Territorios 2020, 150–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón, L.N.G. Los páramos en Colombia, un ecosistema en riesgo. Ingeniare 2015, 19, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina Benavides, R.A.; Campos Gaona, R.; Sánchez Guerrero, H.; Giraldo Patiño, L.; Atzori, A.S. Sustainable feedbacks of colombian paramos involving livestock, agricultural activities, and sustainable development goals of the agenda 2030. Systems 2019, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera, G.M.; Hofstede, R.; Bremer, L.L.; Asbjornsen, H.; Carabajo-Hidalgo, A.; Celleri, R.; Crespo, P.; Esquivel-Hernandez, G.; Feyen, J.; Manosalvas, R. Frontiers in páramo water resources research: A multidisciplinary assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Tarazona, Á. Bucaramanga, entre la sobreexplotación minera o la preservación del agua en el páramo de Santurbán. Entramado 2020, 16, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo Tarazona, Á.; Correa Lugos, A.D. Pensar na mudança socioambiental: Uma aproximação de ações coletivas pelo páramo de Santurbán (Santander, Colômbia). Rev. Colomb. Sociol. 2019, 42, 157–175. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, J.d.J.N. El páramo de Santurbán, donde el agua es oro. Aibi Rev. Investig. Adm. Ing. 2017, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, J.D.M.; Rodríguez, R.S. A profile of corporate social responsibility for mining companies present in the Santurban Moorland, Santander, Colombia. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2016, 6, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Pugliese, C.E.; Machuca-Martínez, F.; Pérez-Rincón, M. Water footprint in gold extraction: A case-study in Suárez, Cauca, Colombia. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacca Contreras, R.E.; García Mantilla, E.; Pinto Mantilla, J.A. Los ambivalentes resultados de una lucha socioambiental: Parque Natural Regional Páramo de Santurbán, Colombia. Soc. Ambiente 2018, 17, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, R.A.; Albahri, A.S.; Alwan, J.K.; Al-Qaysi, Z.T.; Albahri, O.S.; Zaidan, A.A.; Alnoor, A.; Alamoodi, A.H.; Zaidan, B.B. How smart is e-tourism? A systematic review of smart tourism recommendation system applying data management. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2021, 39, 100337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.G.; London, S.; Rojas, M. El turismo como fuente de crecimiento económico: Impacto de las preferencias intertemporales de los agentes. Invest. Econ. 2014, 73, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, R.; Knowles, N.; Pöll, K.; Rutty, M. Impacts of climate change on mountain tourism: A review. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 32, 1984–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peniche, S.; Laure, A.; Cázares, L. El Impacto Ambiental del Turismo Internacional: Caso de la Huella de Carbono de los Vuelos Internacionales Hacia Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco, México; Universidad de Alicante, Instituto Universitario de Investigaciones Turísticas: Alicante, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zohrabi, M. Mixed method research: Instruments, validity, reliability and reporting findings. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2013, 3, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polkinghorne, D.E. Language and meaning: Data collection in qualitative research. J. Couns. Psychol. 2005, 52, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarkar, S.P.; Kumbhar, R. Text mining: An analysis of research published under the subject category ‘Information Science Library Science’in Web of Science Database during 1999–2013. Libr. Rev. 2015, 64, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, S.J.; Pullon, S.R.H.; Macdonald, L.M.; McKinlay, E.M.; Gray, B. V: Case study observational research: A framework for conducting case study research where observation data are the focus. Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 1060–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Marchi, D.; Becarelli, R.; Di Sarli, L. Tourism sustainability index: Measuring tourism sustainability based on the ETIS toolkit, by exploring tourist satisfaction via sentiment analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ramakrishna, S.; Hall, C.M.; Esfandiar, K.; Seyfi, S. A systematic scoping review of sustainable tourism indicators in relation to the sustainable development goals. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 1497–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Torres-Delgado, A.; Crabolu, G.; Palomo Martinez, J.; Kantenbacher, J.; Miller, G. The impact of sustainable tourism indicators on destination competitiveness: The European Tourism Indicator System. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 1608–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Tourism Indicator System: ETIS Toolkit for Sustainable Destination Management; EU Publications Office: Brussel, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Asmelash, A.G.; Kumar, S. Assessing progress of tourism sustainability: Developing and validating sustainability indicators. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimbaljević, M.; Pantelić, M.; Kovačić, S.; Vukosav, S. Destination competitiveness and sustainability indicators: Implementation of the European Tourism Indicator System (ETIS) in Serbia. Менаџмент хoтелијерству туризму 2023, 11, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajnović, A.; Zdrilić, I.; Miletić, N. ETIS indicators in sustainable tourist destination-Example of the island of Pag. J. Account. Manag. 2020, 10, 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- MEDUSA Project. Final Report: Mediterranean Sustainable Adventure Tourism. Available online: https://www.enicbcmed.eu/sites/default/files/2023-03/MEDUSA%20-%20Final%20report.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Sors, J.C. Measuring Progress Towards Sustainable Development in Venice: A Comparative Assessment of Methods and Approaches; Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei (FEEM): Milano, Italy, 2001; p. 275133. [Google Scholar]

- Modica, P.; Capocchi, A.; Foroni, I.; Zenga, M. An assessment of the implementation of the European tourism indicator system for sustainable destinations in Italy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubiaga, M.; Sopelana, A.; Gandini, A.; Aliaga, H.M.; Kalvet, T. Sustainable Cultural Tourism: Proposal for a Comparative Indicator-Based Framework in European Destinations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusch, P.; Fusch, G.E.; Ness, L.R. Denzin’s paradigm shift: Revisiting triangulation in qualitative research. J. Sustain. Soc. Chang. 2018, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Abadía, B.; International, R.B.-W. Disputes over Territorial Boundaries and Diverging Valuation Languages: The Santurban Hydrosocial Highlands Territory in Colombia; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2016; Volume 41, pp. 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livia, W.P.; Reyes, C.A.R.; Galvis, C.S. Un parque temático de geomineria en el distrito minero de Vetas-California (Santander): Un enfoque integrado para evaluar el geoturismo y el potencial de la geoeducación. Rev. Inst. Investig. Fac. Minas Metal. Cienc. Geogr. 2023, 26, e25391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.R.; Shekhar, S.; Vidyarthi, A.; Prakash, R.; Gowri, R. Hyper-Parameter Tuning with Grid and Randomized Search Techniques for Predictive Models of Hotel Booking. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Communication and Computers (ELEXCOM), Roorkee, India, 26–27 August 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Egger, R. Software and Tools. In Applied Data Science in Tourism: Interdisciplinary Approaches, Methodologies, and Applications; Egger, R., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 547–588. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, I.; Khojasteh, J. Python packages for exploratory factor analysis. Struct. Equ. Model. 2021, 28, 983–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M.C.; Henderson, J. A review of exploratory factor analysis in tourism and hospitality research: Identifying current practices and avenues for improvement. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 154, 113328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rheeders, T.; Meyer, D.F. The development of a regional tourism destination competitiveness measurement instrument. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 4, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njeri, M.; Khader, M.; Ali, F.; Line, N.D. Revisiting internal consistency in hospitality research: Toward a more comprehensive assessment of scale quality. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 36, 3072–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Chanes, D.; González-Núñez, J.C.; Ruiz-Fuentes, L.R. Validation of an instrument for measuring the competitiveness of tourism service enterprises: The case of Mexico and Peru. Qual. Quant. 2024, 58, 3769–3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-W.; Lu, W.-M. A comparison of chance-constrained data envelopment analysis, stochastic nonparametric envelopment of data and bootstrap method: A case study of cultural regeneration performance of cities. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 316, 1179–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Ekka, P. Statistical analysis of the impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on the small and large-scale tourism sectors in developing countries. Enviroment Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 9625–9659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lin, H.; Hu, B.; Zhou, Z.; Agyeiwaah, E.; Xu, Y. Advancing the understanding of the resident pro-tourism behavior scale: An integration of item response theory and classical test theory. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widaman, K.F.; Helm, J.L. Exploratory Factor Analysis and Confirmatory Factor Analysis; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Scheyvens, R.; Biddulph, R. Inclusive tourism development. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zárate-Rueda, R.; Beltrán-Villamizar, Y.I.; Murallas-Sánchez, D. Socioenvironmental conflicts and social representations surrounding mining extractivism at Santurban. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvan, E.; Ring, A.; Leisch, F.; Dolnicar, S. Tourist segments’ justifications for behaving in an environmentally unsustainable way. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1506–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuera, H.J.G.; Rogelja, T.; Secco, L. Policy framework as a challenge and opportunity for social innovation initiatives in eco-tourism in Colombia. Policy Econ. 2023, 157, 103076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel de Oliveira, D.; Pitarch-Garrido, M.D. Measuring the sustainability of tourist destinations based on the SDGs: The case of Algarve in Portugal: Tourism Agenda 2030. Tour. Rev. 2023, 78, 475–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achmad, W.; Yulianah, Y. Corporate social responsibility of the hospitality industry in realizing sustainable tourism development. Enrich. J. Manag. 2022, 12, 1610–1616. [Google Scholar]

- Chaabane, W.; Nassour, A.; Bartnik, S.; Bünemann, A.; Nelles, M. Shifting towards sustainable tourism: Organizational and financial scenarios for solid waste management in tourism destinations in Tunisia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E.; Panyik, E. Content, context and co-creation: Digital challenges in destination branding with references to Portugal as a tourist destination. J. Vacat. Mark. 2015, 21, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J.; Page, S.J.; Bentley, T. Towards sustainable tourism planning in New Zealand: Monitoring local government planning under the Resource Management Act. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 867–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, A.; Pantziou, E.F.; Dimara, E.; Skuras, D. Resources and activities complementarities: The role of business networks in the provision of integrated rural tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2007, 9, 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamonde-Rodríguez, M.; García-Delgado, F.J.; Šadeikaitė, G. Sustainability and tourist activities in protected natural areas: The case of three natural parks of Andalusia (Spain). Land 2022, 11, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez Martínez, G.A.; Vázquez Solís, V. Evaluación de recursos naturales y culturales para la creación de un corredor turístico en el altiplano de San Luis Potosí, México. Investig. Geogr. 2017, 94, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkumienė, D.; Atalay, A.; Safaa, L.; Grigienė, J. Sustainable Waste Management for Clean and Safe Environments in the Recreation and Tourism Sector: A Case Study of Lithuania, Turkey and Morocco. Recycling 2023, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senkiv, M.I.; Tserklevych, V.S. Prerequisites of development of an accessible tourism for everyone in the European Union. J. Geol. Geogr. Geoecol. 2021, 30, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, S.J.; Ferreira, J.J.M. Entrepreneurial artisan products as regional tourism competitiveness. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 652–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Blye, C.-J.; Halpenny, E. Impacts of environmental communication on pro-environmental intentions and behaviours: A systematic review on nature-based tourism context. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 1921–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, D.V.; Stangl, B.; Thi Tran, D. Digitalization of information provided by destination marketing organizations in developing regions: The case of Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2023, 28, 324–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Díaz, J.S.; Ordoñez Delgado, N.; Bolívar Gamboa, A.; Bunning, S.; Guevara, M.; Medina, E.; Olivera, C.; Olmedo, G.F.; Rodríguez, L.M.; Sevilla, V. Estimación del carbono orgánico en los suelos de ecosistema de páramo en Colombia. Ecosistemas 2020, 29, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Description |

|---|---|

| Sustainable Management System | Implementation of a sustainable management system covering environmental, social, cultural, economic, quality, human rights, health, safety, security, and risk and crisis management. |

| Legal Compliance | Adherence to local, national, and international legislation and regulations. |

| Sustainability policy reporting and communication | Communication of sustainability policies, actions, and performance to stakeholders. |

| Staff Commitment | Staff commitment to the sustainable management system and regular training. |

| Customer Experience | Measures to ensure customer satisfaction in relation to sustainability. |

| Accurate promotion | Use of accurate and transparent promotional materials and marketing communications. |

| Construction and Infrastructure | Consideration of aspects related to planning, design, construction, and operation of buildings and infrastructure. |

| Property rights and freshwater | Compliance with legal requirements and respect for community and indigenous rights in the acquisition of property and water rights. |

| Information and interpretation | Providing information and interpretation of the natural environment, local culture, and cultural heritage, along with promoting appropriate behavior during the visit. |

| Commitment to Destiny | Participation in the planning and sustainable management of the tourism destination. |

| Local Employment | Providing equal employment and professional development opportunities for residents. |

| Local Consumption | Priority to local and fair-trade suppliers in the acquisition of products and services. |

| Local Entrepreneurs | Support local entrepreneurs in the sale of sustainable products and services. |

| Exploitation and harassment | Implementation of policies against exploitation and harassment, especially of vulnerable groups. |

| Equal opportunity | Offering equal employment opportunities without discrimination. |

| Type | California | Vetas | Suratá | Matanza | Tona |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hotel | 4 | - | - | 2 | 5 |

| Hostel | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Tourist housing | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| Rural Lodging | - | - | 3 | - | 3 |

| Travel Agency | 2 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 8 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 21 |

| Item Code | Skewness | Kurtosis | Skewness OK | Kurtosis OK |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | 0.26 | 1.87 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Item 2 | −7.14 | 52.02 | ✗ | ✗ |

| Item 3a | −0.27 | 1.42 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Item 3b | −0.02 | 1.87 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Item Code | Factor | Mean (M) | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.3.1 | Sustainable Management | 4.96 | 0.27 |

| 2.3.1 | Conservation and Biodiversity | 3.17 | 1.60 |

| 3.2.2 | Social Impact and Participation | 3.43 | 1.07 |

| 4.1.1 | Waste Reduction and Efficiency | 3.13 | 1.54 |

| Item Text | Dominant Factor | Loading |

|---|---|---|

| The company complies with tourism regulations | Sustainable Management | 0.98 |

| Water-saving toilets have been installed | Conservation and Biodiversity | 0.93 |

| The company prioritizes local suppliers | Social Impact and Participation | 0.95 |

| Waste is separated for recycling | Waste Reduction and Efficiency | 0.81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Flórez, M.; Pacheco, E.T.; Carrillo, E.; Villa, M.; Mendes, F.M.; Rivera, M. Sustainable Tourism Practices and Challenges in the Santurbán Moorland, a Natural Reserve in Colombia. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060188

Flórez M, Pacheco ET, Carrillo E, Villa M, Mendes FM, Rivera M. Sustainable Tourism Practices and Challenges in the Santurbán Moorland, a Natural Reserve in Colombia. Urban Science. 2025; 9(6):188. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060188

Chicago/Turabian StyleFlórez, Marco, Elizabeth Torres Pacheco, Eduardo Carrillo, Manny Villa, Francisco Milton Mendes, and María Rivera. 2025. "Sustainable Tourism Practices and Challenges in the Santurbán Moorland, a Natural Reserve in Colombia" Urban Science 9, no. 6: 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060188

APA StyleFlórez, M., Pacheco, E. T., Carrillo, E., Villa, M., Mendes, F. M., & Rivera, M. (2025). Sustainable Tourism Practices and Challenges in the Santurbán Moorland, a Natural Reserve in Colombia. Urban Science, 9(6), 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060188