Abstract

This study examines access to rental housing in the metropolitan area of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, linking it to socio-economic inequalities and the increasing precarization. In recent years, housing affordability has worsened due to rising rents, stagnant wages, and speculative dynamics—particularly those linked to tourism and platform-based economies. Drawing on official data from the State Reference System for Rental Housing Prices (SERPAVI) and income statistics at the census tract level, this research quantifies housing affordability and spatial disparities through indicators such as economic effort rates. The analysis identifies patterns of exclusion and urban fragmentation, showing that large sectors of the population—especially those earning the minimum age—face severe barriers to accessing adequate housing. The findings highlight the insufficiency of current public policies and propose the expansion of social rental housing and stricter rental market regulation as necessary steps to ensure fairer urban conditions.

1. Introduction

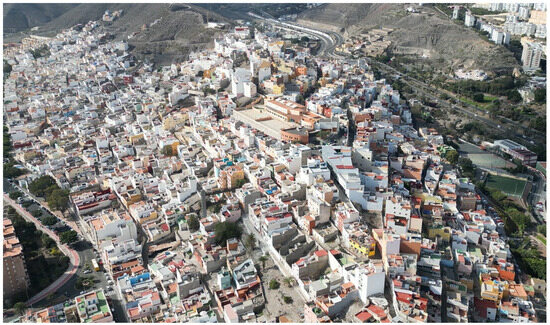

Access to housing is one of the hot topics in Spain. The Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS, Sociological Research Center) (2025) has already identified it as the first greatest concern among Spaniards. Moreover, this issue has extended beyond public debate to become a catalyst for active protests (Figure 1). Its scale has transformed it into a cross-cutting, intergenerational, and multi-scalar challenge. However, its impact varies depending on specific conditions and levels within these dimensions, meaning that inequality in housing access is shaped both by individual circumstances and by broader environmental factors [1,2].

Inequality in housing access is, therefore, a reflection of broader socio-economic disparities [3,4]. The scientific literature has demonstrated that socio-economic disparities are most pronounced in large cities and metropolitan areas [5,6,7]. Economies of scale within capitalism give rise to elites, primarily urban, that operate on a global scale. These dominant classes depend on a proletariat that is drawn to cities due to their economic diversification, which aligns with workers’ skills and aspirations. While urban environments may meet or come close to meeting workers’ salary expectations, the high cost of living depletes their income, erodes their ability to save, and restricts their access to mortgage financing. This dynamic pushes a segment of the working class into precarity, particularly in contexts of rising property prices, high interest rates, inflation, and unstable employment. As a result, a new social class—the precariat [8,9]—has emerged, gradually displacing the middle class.

In this study, the concept of the precariat is approached from a housing-centered and income-based perspective. Rather than adopting a broad sociological definition encompassing labour instability, identity fragmentation, or political disengagement—as originally proposed by Standing [8]—our analysis focuses specifically on the tension between income levels and housing access. In this context, the precariat is understood as a growing segment of the waged population whose capacity to access adequate housing has become increasingly compromised by inflationary dynamics in the real estate market.

This residentially oriented form of precarity arises from a structural mismatch between stagnant or slowly rising wages and the sharp increase in rental prices, particularly in touristified urban areas. Housing affordability thus becomes the key axis of vulnerability: when a basic need such as housing is rendered inaccessible to employed individuals due to price dynamics, precarity is no longer restricted to the unemployed or socially excluded.

At the political level, this phenomenon aligns with the decline of the welfare state and the rise of neoliberal or ultra-liberal paradigms. Within this economic, sociological, and political context, access to housing has become increasingly difficult, particularly for the most vulnerable social classes [10,11]. The significance of this issue lies in the fact that, from a strictly economic perspective, housing is an essential and durable consumer good, spatially scarce due to its fixed and unalterable location, and characterized by a slow production process. Furthermore, housing is legally recognized as a fundamental right under the Spanish Constitution of 1978 (Article 47), which mandates that public authorities safeguard and guarantee its protection [12]. In addition, housing is also regarded as an investment asset, which can, in turn, be transformed into a speculative asset. Thus, its role as a basic necessity—explicitly recognized as a right in the constitutions of 78 countries [13]—coexists, contrasts, and competes with its economic function [14]. In a capitalist system dominated by free-market dynamics, a crisis of housing availability emerges. At times, this crisis is driven by artificial scarcity, exacerbated by the prioritization of housing as an economic asset over its recognition as a fundamental right. In this context, profitability takes precedence over social need, shaping supply, while price serves as a barrier to housing access. This situation is further aggravated by the growing demand for housing.

Figure 1.

(a) Protests against gentrification in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (Canary Islands), Spain; (b) Demonstration in support of the right to housing in Madrid, Spain [15].

Figure 1.

(a) Protests against gentrification in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (Canary Islands), Spain; (b) Demonstration in support of the right to housing in Madrid, Spain [15].

Not only at the national level but also internationally, housing needs arise from factors such as urban population growth, immigration inflows [16], and the decline in average household size—driven by the rapid shift from traditional family structures to more diverse and fluid household arrangements [17,18]. Additionally, competition from tourist rentals reduces the availability of housing for residential use [19], while, to a lesser extent, temporary rentals catering to the creative class, including digital nomads, also leave an imprint on the market [20,21]. This situation reflects a broader lack of strategic governance in tourism development, particularly in regulating the spread of short-term rentals, which has further intensified housing affordability issues in touristic metropolitan areas like Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. In the rental market, additional factors come into play, such as the growing presence of large property owners and their speculative practices, which are increasingly facilitated by the digital and platform economy [22].

Given the structural and situational specificities of the housing market—characterized by inelastic supply and demand—a convergence of factors has led to the current housing crisis and emergency in Spain. This article is based on the hypothesis that socio-economic inequality is a key determinant of housing access at the intra-urban scale. In the current context of inflationary pressure in Spain, rental housing has become the only viable option for a large segment of the population, particularly the most vulnerable groups. This trend is deepening residential segregation and emerging as a major driver of urban fragmentation (especially in cities where tourist demand competes with residential use). Supporting this argument, the Bank of Spain [23] reports that 46% of Spain’s rental population was at risk of poverty or social exclusion between 2015 and 2023—the highest percentage in the European Union (EU). This is even though, according to the same 2022 report, two-thirds of Spaniards aged 18 to 34 still live with their parents. Furthermore, the significance of this issue is reinforced by its broader implications for socio-economic inequality. As stated by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights: “housing is not adequate if its cost threatens or compromises the occupants’ enjoyment of other human rights” [24] (p. 5).

Consequently, the main objective of this study is to analyze the economic effort required to access rental housing across different areas of the urban space, using the metropolitan area of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria—which encompasses the municipalities of Arucas, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Santa Brígida, and Telde—as a case study. The study aims to identify existing and emerging patterns of residential segregation and spatial fragmentation in the city by mapping areas where housing is financially inaccessible to increasingly precarized segments of the population.

This study is structured as follows: after the introduction, a theoretical and contextual section examines the dominance of mercantilist hegemony within the conceptual duality of housing, as well as the increasing entrenchment of precarity. Additionally, it provides an overview of the rental market at regional, national, and local scales. Next, the methodological section outlines the data sources and analytical processes employed. The results section presents a spatial analysis comparing income levels with housing access in the metropolitan area of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. Finally, the conclusions offer proposals and insights within the broader context of the ongoing housing access crisis.

2. Conceptual and Contextual Perspectives

2.1. The Two Faces of Housing: A Social Right or a Speculative Asset

The paradigm of housing as a right has significant implications for the analysis of the real estate market. This socio-political perspective is essential for understanding the housing context in countries such as Spain, Brazil, Argentina, South Africa, and Portugal, among others. However, this theoretical right has inherent limitations: it does not guarantee access to housing, as no political consensus exists for its full implementation. In Spain, the right to adequate housing is enshrined in the Constitution as a guiding principle but lacks full justiciability [12]. In other words, although public authorities are obligated to provide housing, individuals cannot legally claim it through the courts. This contradiction weakens the constitutional mandate, making it neither immediate nor absolute.

Such barriers constrain housing as a social right while simultaneously reinforcing its status as a market commodity, subject to speculation [25,26] and to the fluctuating economic and political conditions of both nations and urban spaces [27].

Thus, the problem of housing access intensifies during inflationary and speculative cycles, making it difficult to effectively uphold the legal notion of the right to housing [28,29], particularly for the most vulnerable groups [30].

Recently, one of the key drivers of this dynamic has been the platform economy. The emergence of new actors, such as Airbnb, has further commodified housing, transforming urban areas into trendy spaces in Europe and other parts of the world. These transformations are often celebrated for their economic vitality but rarely assessed in terms of how the redistribution of their benefits compares to the social costs they generate—particularly at the intra-urban scale, where their uneven impacts on neighborhoods and residents become most apparent. For example, recent research has shown that online reviews—particularly their volume, valence, and perceived helpfulness—can significantly influence hotel booking prices through mechanisms of social proof and digital reputation [31]. Al-though focused on the hospitality sector, these findings are highly relevant in urban contexts, where reputation systems and user-generated content increasingly shape housing values and access in areas affected by tourism and short-term rentals. In Latin American cities like Mexico City and Buenos Aires, new urban fabrics have developed, specifically designed to cater to high-income demand. This process has led to socio-spatial exclusion and the displacement of vulnerable populations [32,33]. In many cases, the economic gains associated with tourism—such as increased revenues and job creation—are not matched by compensatory policies aimed at mitigating its social costs, particularly those linked to housing exclusion. This imbalance is further exacerbated by the lack of effective wealth redistribution mechanisms, which could otherwise help ensure that the benefits of tourism are more equitably shared across society.

Also, these urban transformations, while shaped by global investment trends, also reflect inter-municipal learning and policy diffusion. Cities facing comparable housing pressures often replicate regulatory strategies adopted by their peers.

A similar dynamic has been observed in other domains, such as the digital economy, where peer effects have been shown to influence regional development trajectories. Recent research highlights how mutual learning and policy benchmarking can reshape territorial development patterns, including positions within the digital value chain [34]. This analogy helps explain the convergence of housing policies and urban responses across different metropolitan contexts. Some regional governments, including the Canary Islands, are now attempting to address these distortions through specific legislative proposals aimed at the sustainable management of tourism-related housing.

In this context, the new housing market has become increasingly internationalized and oriented toward alternative uses, such as tourism, fostering a competitive environment that has diminished housing affordability for local population—both in terms of homeownership and rental [35,36]. This phenomenon reshapes the geographic distribution of residents, displacing vulnerable groups to the urban periphery or deteriorated areas [37,38].

This inflationary housing cycle is not unique. The current situation coincides with rising prices of other essential consumer goods within a globally unstable geopolitical context, which contrasts with stagnant wage dynamics. As a result, financial insecurity has increased for both households and individuals, hindering the formation of new independent households [39]. In summary, this has led to a dual yet interconnected process of rising costs and growing precariousness. In Spain, this dynamic has manifested as a housing affordability crisis that is both socially pervasive and geographically widespread. In some areas, the degree of polarization becomes so extreme that it creates prohibitively expensive urban spaces.

This shift from difficulty to outright impossibility in accessing housing is not only a social issue but also an economic one, affecting private entities as well. In response, the market—both in this and previous periods—has adopted self-preservation mechanisms. The financialization of housing has served as a strategy to maintain a solvent and stable demand in the homeownership market. However, financialization theory argues that the expansion of mortgage credit, institutional real estate investment, and property speculation—particularly in high-demand urban areas—have transformed housing into a vehicle for wealth accumulation rather than a fundamental necessity [40,41]. This underscores the absence of a social perspective in such a solution; instead, it exacerbates, entrenches, and perpetuates precariousness while generating profit from it [42].

Currently, the core issue is that, given the depth and extent of socio-economic precariousness, financialization has become an insufficient mechanism. Households are increasingly unable to accumulate the necessary savings to qualify for home purchase financing, while the rental market—characterized by growing price volatility—has become largely inaccessible.

In this new context, public housing policy has remained on its traditional course, primarily addressing emergency situations and the most vulnerable groups. Rather than challenging the market-driven approach to housing, it functions as a reactive measure to its consequences.

There are examples of this approach worldwide. Canada’s National Housing Strategy, inspired by European models, aims to eradicate homelessness and housing insecurity with a clear social perspective [43]. In France, however, public housing policies have failed to reduce income-based residential segregation, as the concentration of social housing in specific districts has deepened inequalities rather than alleviating them [44]. This approach to public housing effectively restricts it as a right only for the most vulnerable, while reinforcing its status as a market commodity for the rest of the population.

Through these two mechanisms—financialization and traditional public policy—housing is doubly embedded within the logic of investment and capital accumulation. This has led to an exclusionary and fragmented urban landscape that favours higher-income groups while further marginalizing vulnerable populations [36,45].

Meanwhile, the social base requiring these policies has expanded [46], heightening the risk that public resources will be insufficient to meet growing demand. This large-scale issue has already manifested in extreme forms in countries like Brazil, where vast segments of the population face persistent vulnerability, and public policies have produced only limited and palliative results, failing to address housing shortages or mitigate socio-spatial inequality [47].

However, alternative perspectives on the issue have emerged. Recently, initiatives operating outside the institutional framework have gained traction, advocating for housing as a fundamental and universal right while seeking to restore the social function of property. For instance, social mobilization and housing rights campaigns in Ireland have successfully increased public awareness of the issue, serving as a crucial first step toward political recognition [48]. Another example is the Coalition for the Right to Housing and the City, which promotes a transnational approach by connecting activists from various European countries to resist the commodification of housing [49]. In Spain, Catalonia has been at the forefront of developing specific legislation to address housing emergencies. This effort has been reinforced by collaboration between social service professionals and local administrations, although administrative fragmentation remains a significant obstacle to its full implementation [45].

Following Catalonia’s lead, the Spanish government approved a law recognizing the right to housing. This legislation opens the possibility for an approach that goes beyond a focus on vulnerable individuals, instead addressing housing as a structural and cross-cutting issue. Whether due to an inability or unwillingness to function as a welfare state, Spain’s current government appears to be shifting toward a more interventionist model—although this remains to be seen. The law includes provisions for rental price controls, but its implementation depends on consensus between local and regional administrations [50]. This framework is operationalized through the designation of stressed residential market areas, where market conditions are assessed in relation to the financial burden on households and individuals seeking to access housing. In the Canary Islands, only one municipality—Las Palmas de Gran Canaria—has requested such a designation, yet it is still awaiting a response from the competent regional government.

2.2. Rental Market Situation in the European Union, Spain, and the Canary Islands

The rental housing market in the EU is heterogeneous; however, in recent years, it has followed a global trend of rising prices. According to the Housing Anywhere International Rent Index for the second quarter of 2024—which analyzes rental prices in 28 European cities, including three in Spain (Madrid, Barcelona, and Valencia)—rents have increased by 4.3% year-on-year [51]. The highest rental prices are found in the Netherlands and Germany. Meanwhile, although Italian and Spanish cities still have slightly lower prices, they have experienced the most significant increases between 2023 and 2024, narrowing the gap with Central Europe.

Spain has traditionally favoured homeownership, largely due to a housing model centered on promoting free-market housing [52]. However, this trend has shifted, as the proportion of homeowners has declined by 1.8% since 2017 [53], amounting to a total decrease of 6% over the past two decades [23,54]. Despite this, Spain remains far from the levels observed in the most developed EU countries, such as Germany and Austria, where only 50% of the housing stock is owner-occupied. In 2023, Spain’s homeownership rate stood at 75.3%, slightly above the EU average (75%) and, along with Portugal’s, was among the highest in Western Europe. Meanwhile, Eastern European countries continue to exhibit the strongest preference for homeownership.

Several factors have contributed to this shift, including rising home prices in recent years [55], difficulties in accessing mortgage loans, and job insecurity. According to the Bank of Spain, the inflation-adjusted price of new housing in 2023 matched 2007 levels, when prices peaked during the so-called real estate bubble [56]. Furthermore, the Bank of Spain reported that homeownership stood at 74% in 2024, reinforcing the trend toward rental market expansion [54].

According to Eurostat data, rental prices increased by an average of 18% between 2010 and 2023 [53]. A significant part of this rise is attributed to the growing prevalence of short-term rentals, which affect the overall market by both inflating average rent prices and reducing the supply of available housing. The same source indicates that rental price increases across the EU have been even more pronounced than those recorded in Spain, where rents rose by 28% between 2015 and 2022 [54]. Strong housing demand has fuelled speculation in the real estate sector, with gross rental yields for residential properties estimated to range between 5% and 6% annually—nearly double the returns offered by banks for an equivalent capital investment.

In this context of high real estate profitability, rental prices have followed a parallel upward trajectory. The European rental market faces persistent challenges related to price inflation—28% between 2010 and 2022—which some researchers cautiously associate with the expansion of short-term rental platforms [57]. The issue has gained such prominence that the Court of Justice of the EU has intervened to uphold the right of states to regulate the vacation rental market [58].

For instance, Germany sets reference prices by zones based on rental costs and tenants’ financial burden, designating stressed residential market areas where housing expenses exceed the national average. Similarly, France employs rental regulation mechanisms that link rent adjustments to the Consumer Price Index (CPI), allowing cities to establish final reference prices. Other countries, such as Austria and the Netherlands, exercise greater control through their extensive stock of social rental housing, which accounts for at least 25% of the total supply—a significantly higher share than in Spain.

So far, Spain, like Portugal, has been a relatively non-interventionist state, despite having a very low percentage of social rental housing—around 80,000 units, according to the Ministry of Housing and Urban Agenda, representing just 2.5% of the total housing stock. The main policy measures in the Iberian countries have been rental assistance programs and, in Spain’s case, the recently enacted Right to Housing Law. This legislation introduces measures to cap rental prices in designated areas, following the examples of Germany and France.

At the national level, the rental housing market in Spain exhibits a clear dichotomy [55]. While the eastern coastal regions, Madrid, and both island archipelagos have the highest Rental Housing Price Index (IPVA) values, inland Spain and Cantabria report the lowest figures. On a provincial scale, 11 regions exceed the national average (115.7), including Barcelona, Madrid, Toledo, Guadalajara, Valencia, Alicante, Castellón, the Balearic Islands, Granada, Málaga, Seville, and Santa Cruz de Tenerife. Meanwhile, the province of Las Palmas, with an index of 115.06, falls just below the national average.

According to the Rental Observatory, five autonomous communities have an average rental price exceeding EUR 1000 per month: the Balearic Islands, Madrid, Catalonia, the Basque Country, and the Canary Islands. This source also indicates that in several Spanish provinces, rent accounts for more than 35% of household income, with Guipúzcoa, Barcelona, Málaga, and Las Palmas standing out at 38%, and the Balearic Islands at 39%. In response to rising rental costs, alternative residential models have gained traction, particularly co-living [59]. In fact, areas with lower rental prices tend to have fewer shared households, whereas in high-rent locations, a greater number of people share apartments.

The data confirm that the Canary Islands is one of the most stressed housing markets, particularly in the two capital islands. The surge in short-term rental properties followed the enactment of Decree 113/2015 of May 22, which regulates vacation rentals in the Canary Islands [60]. Short-term tourist rentals appear to have contributed to a reduction in the availability of residential rental housing, although the extent of this impact varies geographically. Despite all this, the Canary Islands have not yet established rental limits beyond those dictated by the market itself. Currently, a project is being prepared for the designation and declaration of stressed areas, which would allow for capping prices. In this sense, state intervention is minimal and is limited to providing rental assistance.

In Santa Cruz de Tenerife and Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, it is estimated that between 20% and 25% of the housing stock is allocated to the rental market, exceeding the national average, mainly due to the enormous weight of tourist activity, as well as a lower income of citizens in relation to the rest of Spain. This conditions a greater weight of the rental market in these cities due to the high prices of buying a property. In 2023, 10% of these rental properties in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria were short-term vacation rentals [54,60], a factor that has inevitably influenced rental prices. In this regard, studies in the United States suggest that a 1% increase in Airbnb listings leads to a 0.02% rise in rental prices [61]. This illustrates how the benefits of tourism are not distributed evenly, especially when its expansion is not accompanied by redistributive housing policies or public safeguards for long-term residents. Given the rapid growth of short-term rentals in the study area, applying this trend would indicate a significant increase in rental prices in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria.

3. Sources and Methods

This study draws on official sources for rental prices and income data. In Spain, the lack of comprehensive rental market data has historically posed a significant limitation. However, this gap was recently addressed with the enactment of the Right to Housing Law in 2023, whose preparatory efforts led to the creation of a national rental price database.

The State Reference System for Rental Housing Prices (SERPAVI, by its Spanish acronym), managed by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Agenda, serves as a key source of information on rental prices. The dataset provides data at multiple spatial scales, including national, regional, provincial, municipal, district, and census tract levels. For this study, the most detailed unit—census tracts—was used, enabling intra-urban analyses of rental housing supply, price distribution, affordability disparities, and other key factors.

The data are sourced from Personal Income Tax (IRPF, by its Spanish acronym) declarations, which record rental income from properties used as primary residences, along with information on housing size and price by property type. This allows for the classification of two main housing categories for each geographic unit of analysis: single-family housing and multi-family housing. Each category includes variables such as the number of rental units, median monthly rent per square meter (in euros), the 25th and 75th percentiles of monthly rent per square meter, median monthly rent (in euros), and its 25th and 75th percentiles. However, when sample sizes are too small, associated data on rental prices, total amounts, and housing size are omitted due to statistical insignificance and confidentiality requirements.

The metropolitan area of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria exhibits heterogeneity in both urban development patterns and predominant housing types. Multi-family housing is the dominant typology, resulting in high-density residential and demographic zones, particularly in the capital city. In contrast, single-family housing is more prevalent in the periphery, where settlement patterns are more dispersed. However, pockets of single-family homes also exist within denser urban areas, either coexisting with multi-family buildings or forming small clusters. The distribution of rental housing types in the SERPAVI database aligns with the predominant housing typology in each area. In other words, areas where SERPAVI data indicate a predominance of multi-family rental housing also exhibit a higher concentration of this typology in the built environment. Consequently, the analysis has been adjusted to account for both housing typologies, as their relative weight in the real estate market varies across different geographic zones.

There are two primary limitations associated with this data source, both linked to potential discrepancies between market realities and recorded data. The first limitation concerns a possible time lag in rental price reporting, which may be particularly significant in speculative market conditions. The second limitation relates to price reporting itself, as declared rental income directly affects landlords’ tax obligations. Higher rental income results in higher tax liabilities, which in some cases has incentivized tax evasion. This is particularly prevalent in rentals to foreign tenants who are not required to declare income in Spain—an increasingly common phenomenon in the Canary Islands due to the high level of European immigration, both permanent and seasonal. While the full extent of this issue is difficult to quantify, its occurrence cannot be ruled out. In extreme cases, rental transactions remain entirely undeclared, unregulated, and unregistered, meaning such properties and their prices are absent from the SERPAVI database. This represents a third limitation of the data source.

Despite these challenges, the SERPAVI database remains an essential tool for analyzing Spain’s rental market and housing accessibility, particularly in informing public policy. It is the only legally recognized reference for identifying stressed residential market areas, as this designation requires official validation. The integration of SERPAVI data with income statistics allows for a comprehensive assessment of housing affordability. This study incorporates data on the national minimum wage (SMI, by its Spanish acronym) provided by the Spanish government (along with its periodic updates), regional gross average wages from the National Statistics Institute’s (INE, by its Spanish acronym) Wage Structure Survey, and median household income figures from the INE’s Atlas of Household Income Distribution, all analyzed at the same spatial level—census tracts. Together, these data sources enable the calculation of economic effort ratios for individuals and households, supporting the designation of stressed residential market areas. Therefore, a practical and legal approach has been applied in selecting and handling data sources, ensuring spatial consistency across all variables.

To operationalize the concept of the precariat, we define it as those individuals or households who, despite being economically active, earn an income equivalent to or below the Spanish Minimum Wage (SMI) and reside in areas where the median rental cost of housing exceeds 30% of their monthly gross income. This threshold is not arbitrary: it follows the legal criterion established by Spain’s Right to Housing Law (Ley 12/2023), which defines “stressed residential market areas” as those where rental housing costs exceed 30% of average household income—thereby recognizing this proportion as an indicator of financial unsustainability. This benchmark had already been applied by Royal Decree 42/2022, regulating the Youth Rental Voucher, which used the same 30% threshold to assess rental burden and eligibility. This definition is applied spatially through census tract-level data, where these conditions can be jointly verified: low reported income, high rental burden, and concentration in specific neighborhoods characterized by structural disadvantage.

To ensure a more accurate assessment of the current situation, an adjustment factor has been applied to official rental price data based on municipal-level information from the Idealista real estate portal for the years 2022 to 2025. This adjustment provides an approximate update on housing affordability conditions, particularly for specific groups, such as the most vulnerable segment of the working class—those earning the SMI. However, because data of Idealista are drawn from a limited and changing sample of active listings, and its intra-urban divisions do not correspond to official cartographic units, direct use of its averages would distort the spatial analysis. For this reason, a single correction factor at the municipal scale was applied uniformly to SERPAVI’s tract-level data. This preserves internal spatial consistency while offering a cautious and realistic approximation of recent price evolution.

Nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge that the limitations of the SERPAVI dataset—particularly those related to delays in data availability or declaration, as well as possible tax evasion—may have implications for the robustness of the results. While some of these issues are mitigated through the application of an adjustment factor based on municipal-level data from the Idealista real estate portal, such measures cannot fully eliminate potential biases. These biases may affect the accuracy of rental price estimates and, consequently, the reliability of affordability indicators. These limitations may skew the findings by systematically underestimating rental prices in certain areas, especially where informal or undeclared rentals are more frequent. However, it is not possible to accurately estimate the degree of this distortion, as the level of irregularity is neither homogeneous nor stable over time but instead depends on the individual behaviour and decisions of property owners. As a result, the spatial representation of affordability may be biased, potentially underrepresenting areas of acute housing stress. The findings should therefore be interpreted with appropriate caution. We believe that the correction factor (especially temporary in a highly speculative market), introduced by the real estate web Idealista, has been a pragmatic solution to improve the strength of the analysis. We say this because Idealista is one of the leading portals in Spain, with a quarter of a century of history and more than 40 million visits a year on its website, broadly complementing the reality of the Spanish real estate market and, with limitations as we said, providing the public source SERPAVI, with more realistic data.

4. Results

4.1. Income Distribution and Residential Rental Market

This section provides a brief overview of income distribution in the metropolitan area under study, as it is a key determinant of access to residential rentals. As previously discussed, income levels play a crucial role in shaping an exclusionary and fragmented urban landscape, benefiting higher-income groups while simultaneously creating vulnerable sectors [23,36,45].

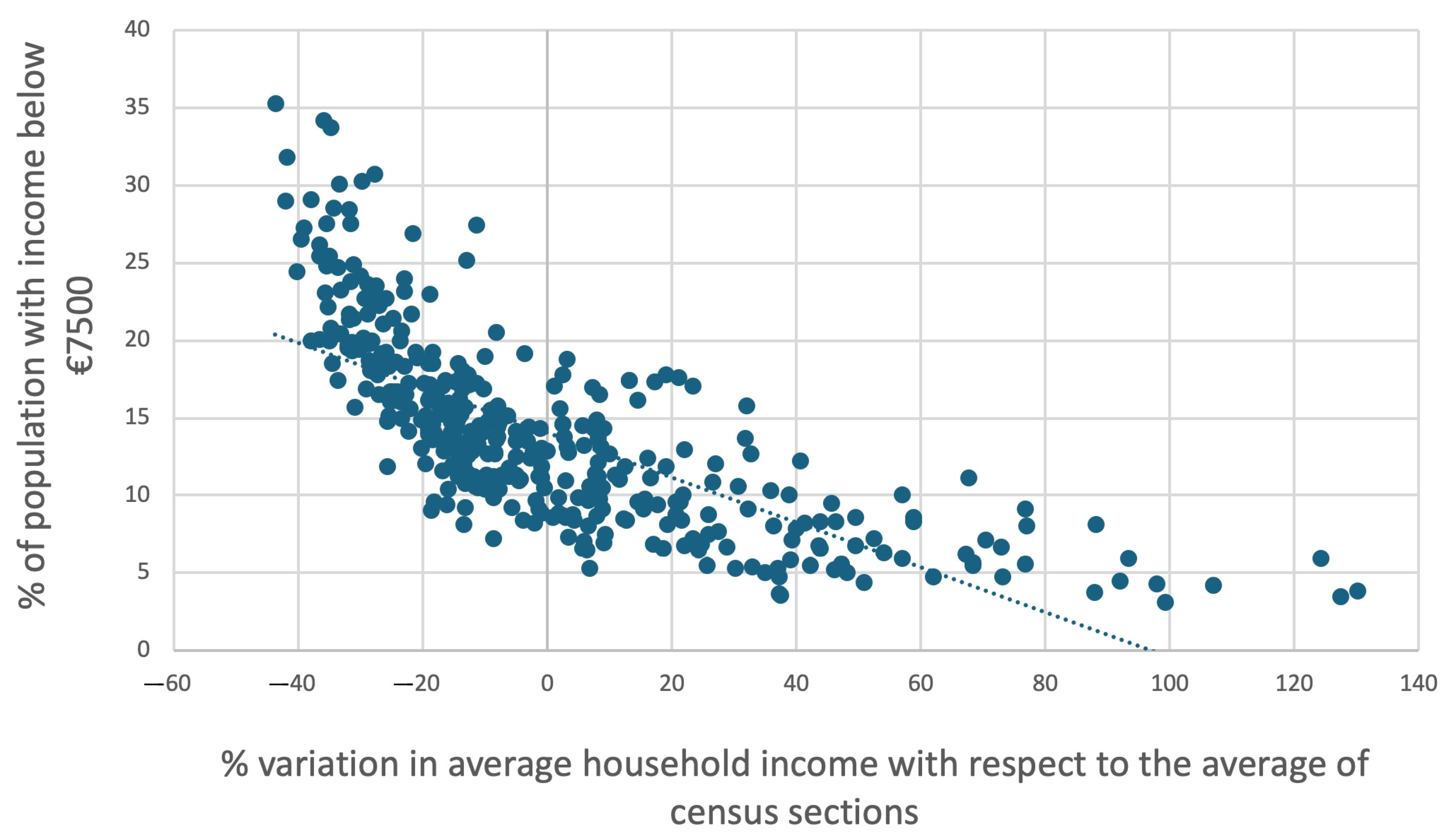

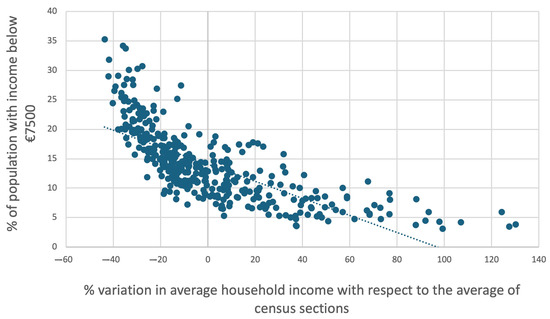

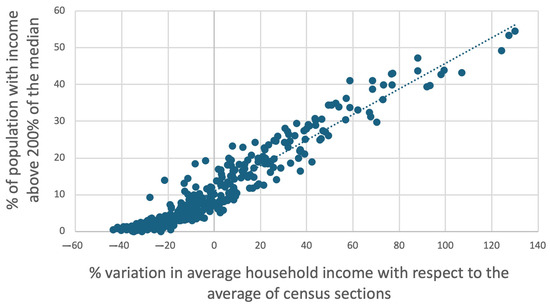

In this regard, analyzing a key variable from the Atlas of Household Income Distribution for 2022 [62]—specifically, the population at highest risk of economic vulnerability, defined as households with annual incomes below EUR 7500—reveals that this group is largely concentrated, as expected, in census tracts with the highest levels of housing precariousness. In other words, these groups tend to cluster in areas where average household income is between 20% and 40% lower than the metropolitan average, while their presence declines significantly in more affluent districts. However, even in census tracts with higher-than-average income levels, there are still residents with very low earnings (Figure 2, bottom right). This pattern aligns with intense gentrification processes, particularly in areas such as Puerto–Canteras and Guanarteme, which have been subjected to significant urban development pressure. These neighborhoods, which until two decades ago exhibited signs of vulnerability, now experience ongoing tensions between long-term residents—particularly the elderly, who resist displacement—and the growing influx of speculative capital seeking to transform these traditional districts.

Figure 2.

Correlation between the population with per consumption unit income below EUR 7500 and the average household income by census tract in the metropolitan area of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (2022) [62].

The most vulnerable census tracts—those falling between −20% and −40% of the average household income across all tracts—tend to be concentrated in the most disadvantaged and exclusionary districts. These are precisely the areas that will later be identified as having the lowest rental prices, although they have also experienced a significant increase in costs. Nevertheless, household incomes below EUR 7500 already imply a substantial financial burden for families facing rental payments. These census tracts include areas such as Las Rehoyas, Jinámar, Las Remudas, and Schamann, among others. Here, the indicators also show lower wages, higher unemployment rates, and consequently lower average social benefits, as well as the lowest pension levels in the region.

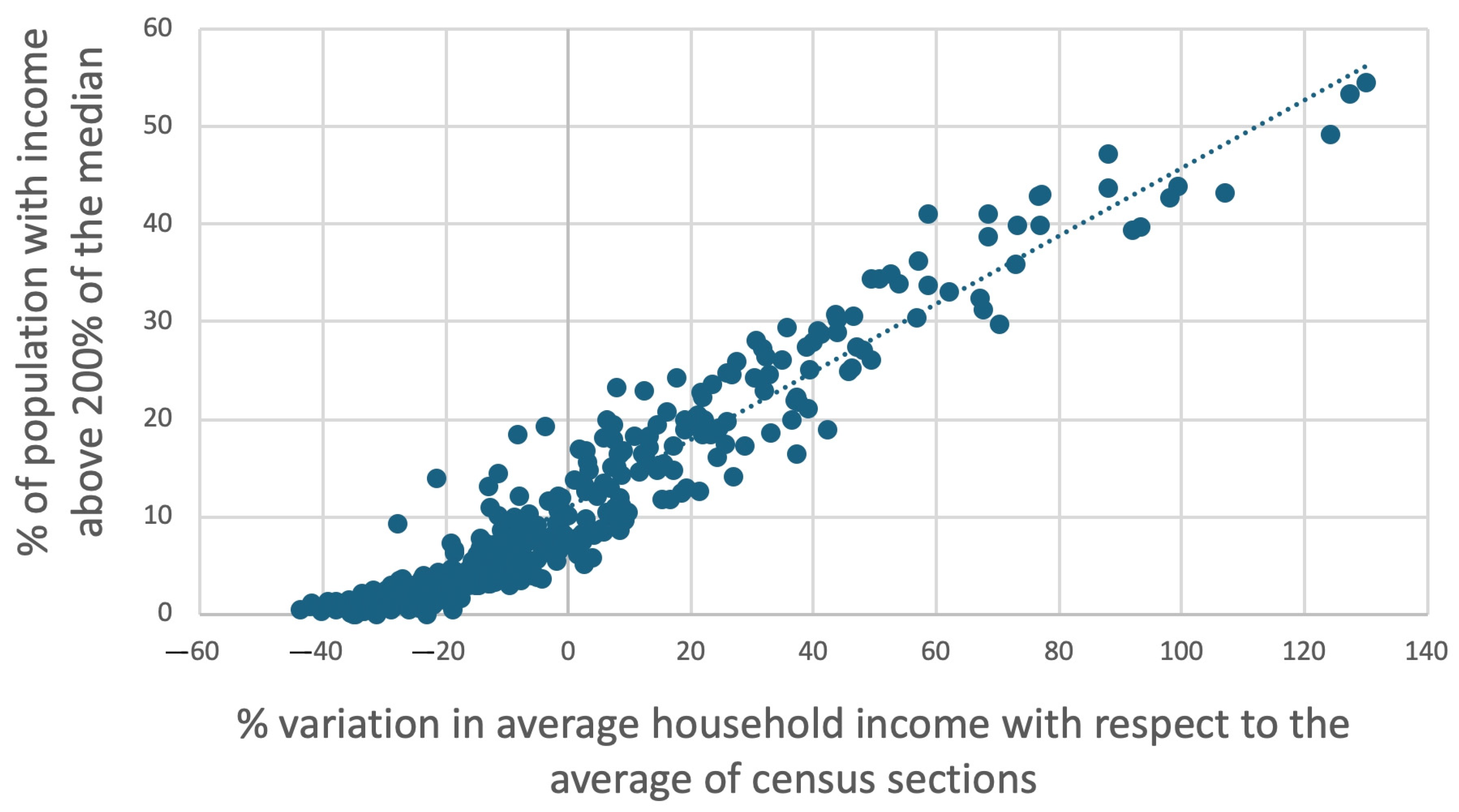

Conversely, census tracts where per consumption unit incomes exceed 200% of the average household income tend to be concentrated along the coastal strip, with notable areas including Las Canteras, Avenida Marítima, and La Minilla (in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria), or Playa del Hombre, Mar Pequeña, and La Garita (in Telde). Similarly, high-end residential areas in Santa Brígida, such as Tafira Alta, Monte Lentiscal, El Reventón, and Bandama, along with select locations prized for scenic views or excellent accessibility to the city center—such as Altavista, 7 Palmas, and Ciudad del Campo—constitute the census tracts positioned toward the center-right of Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Correlation between the population with per consumption unit income exceeding 200% of the median and the average household income by census tract in the metropolitan area of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (2022) [62].

In summary, these are areas where building density generally decreases, forming what is known as the dispersed city, except for the enclaves of Las Canteras and Avenida Marítima, mentioned above. All these areas share a common pattern: high household income levels and very high rental prices for both multi-family and single-family housing, making them inaccessible to a large segment of the population—particularly those earning the SMI, as analyzed below.

4.2. Rental Market Dynamics and Land Prices

The SERPAVI data allows for an analysis of the rental market in the metropolitan area of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, based on information from 24,525 multi-family housing units and 3027 single-family homes. The 2021 Housing Census indicates that there were 42,933 rental properties in the study area. Therefore, even with a one-year discrepancy (SERPAVI data correspond to 2022), the SERPAVI records represent 64.17% of the total rental housing stock. These records are even more representative, as census data also include other types of rentals, such as short-term leases.

According to SERPAVI, the Canary Islands ranks as the seventh Spanish autonomous community in terms of the number of multi-family rental housing units (88,043). However, in terms of median rental price (EUR/m2), it holds the fourth position at EUR 6.96/m2, surpassed only by the Community of Madrid (11.09 EUR/m2), Catalonia (9.04 EUR/m2), and the Balearic Islands (EUR 8.60/m2). When considering single-family homes, the Canary Islands moves up to third place in median rental price (5.59 EUR/m2), ranking behind only the Community of Madrid (EUR 6.75/m2) and the Balearic Islands (5.93 EUR/m2). In other words, the Canary Islands is only surpassed by Spain’s two most populous and economically developed regions, as well as the other Spanish island region, which is also heavily influenced by tourism.

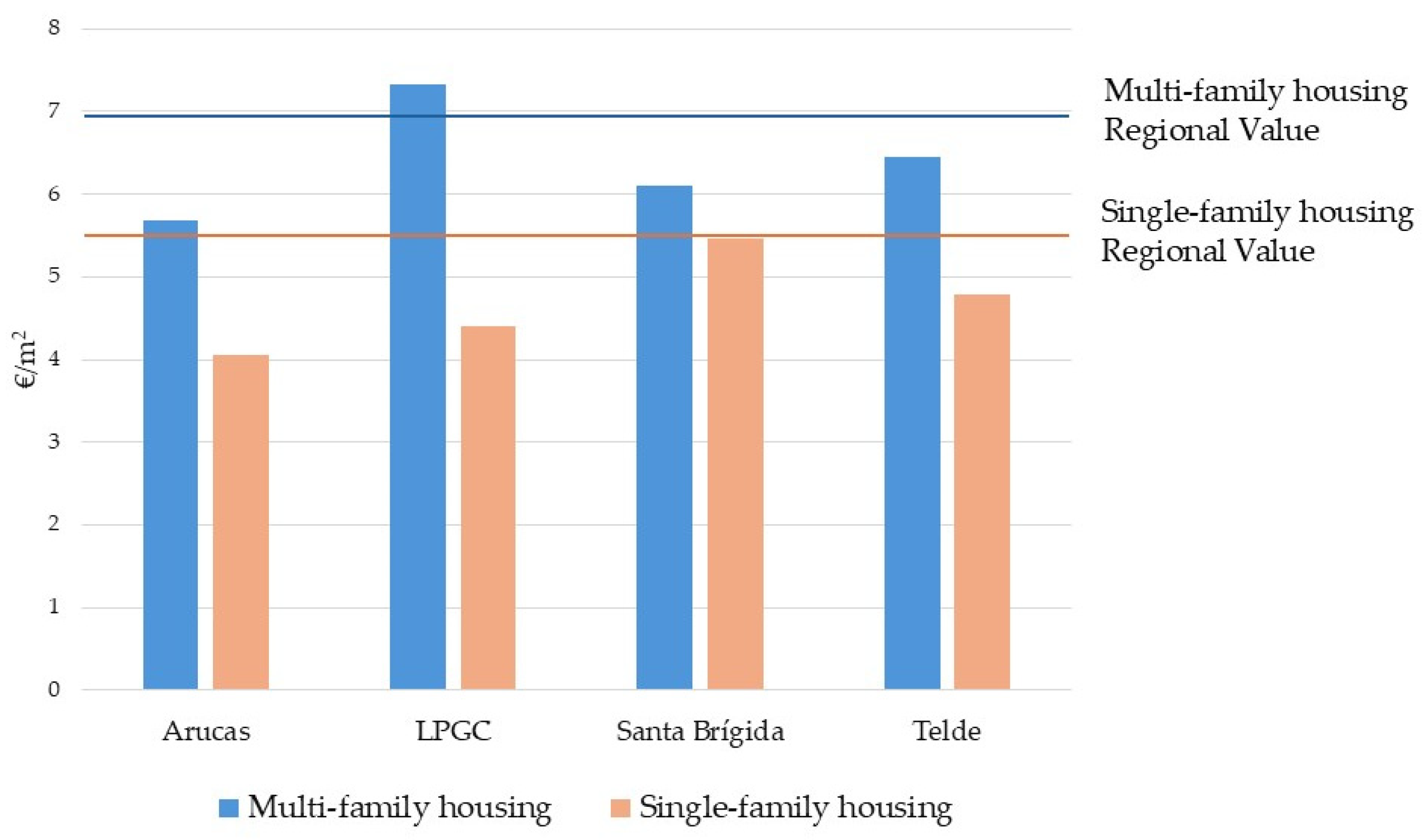

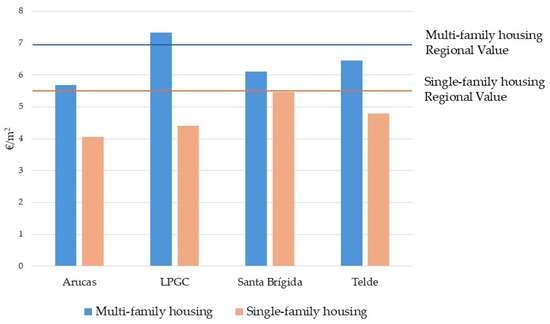

Focusing on the municipalities within the study area, only Las Palmas de Gran Canaria exceeds the regional median rental price for multi-family housing (7.32 EUR/m2), while the satellite municipalities within the metropolitan area remain below this value (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Rental price per square meter by housing typology [63].

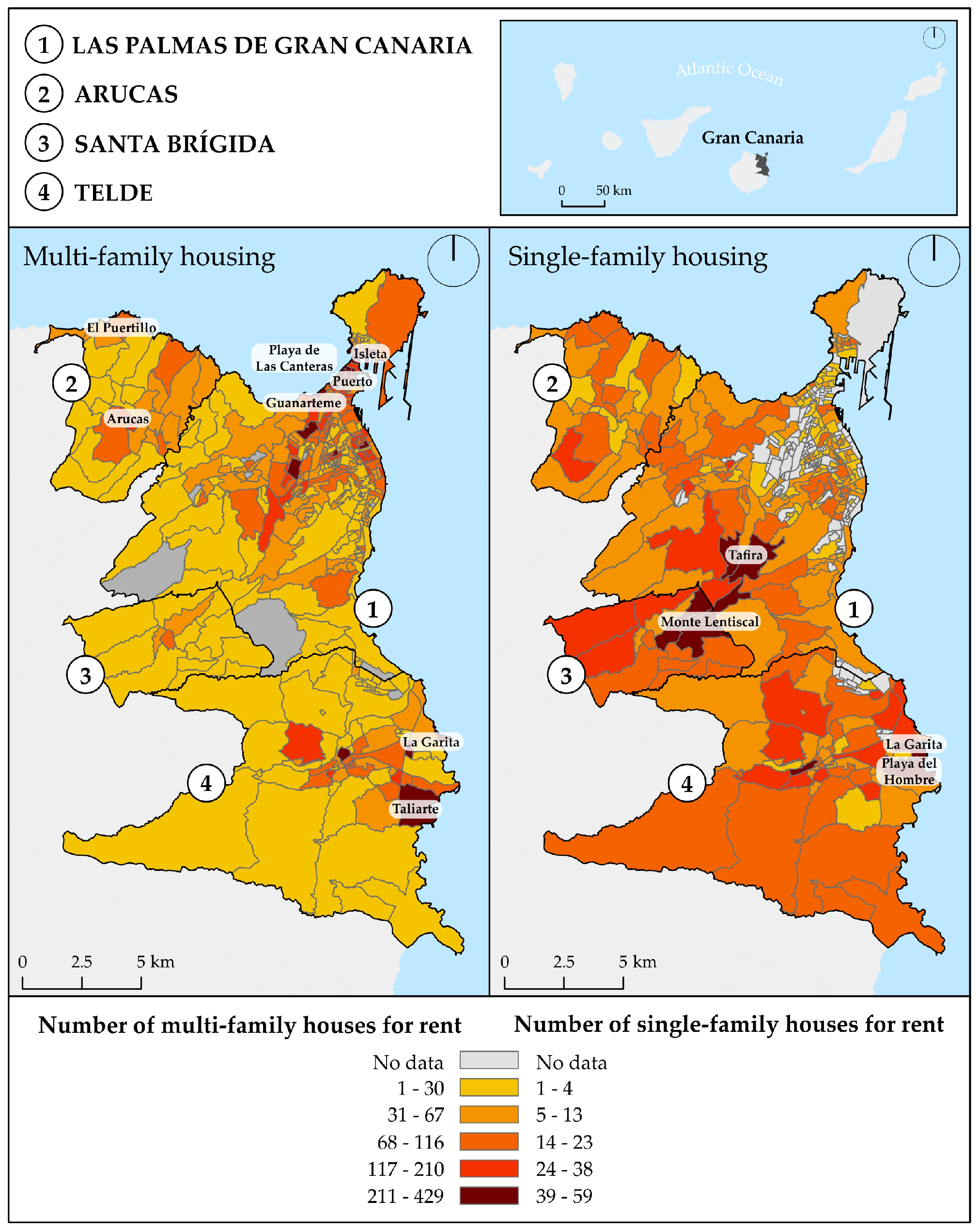

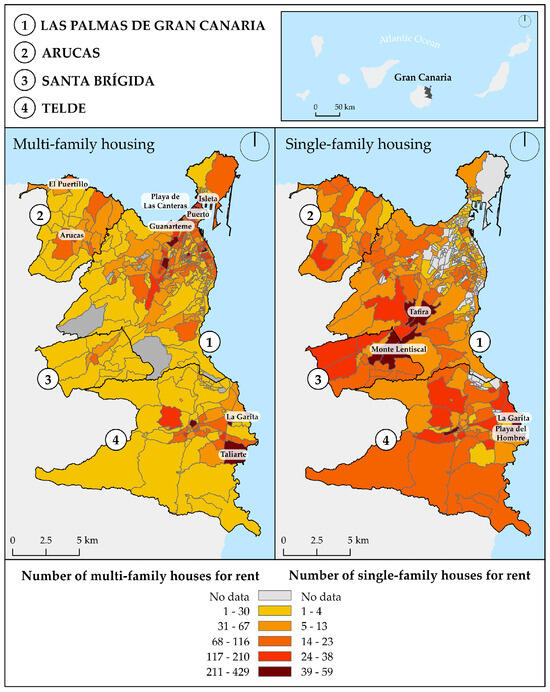

This analysis can be interpreted at two different scales. On a regional scale, the distribution of rental prices reveals a significant influence of tourism, as the most expensive municipalities in the archipelago are tourist destinations: Mogán (12.20 EUR/m2), Tías (9.09 EUR/m2), Puerto de la Cruz (9.02 EUR/m2), and Adeje (9 EUR/m2). On the other hand, within the study area, only the capital city (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria) has a notable tourism sector and infrastructure, yet this is only enough for it to rank 21st out of 88 municipalities in the Canary Islands in terms of multi-family rental prices. The impact of tourism is not only reflected in rental price levels but also in the spatial distribution of multi-family rental housing at the intra-municipal scale (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Number of rental housing units by housing type in the metropolitan area of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria [63].

In this case, traditional sun-and-beach tourist areas and their surroundings stand out, including Playa de Las Canteras, the Puerto–Isleta area, and Guanarteme in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, as well as coastal locations in Telde, such as La Garita–Playa del Hombre and Taliarte, and in Arucas, particularly El Puertillo. This suggests that tourism is not the only key factor—although it is particularly significant in Las Canteras—but that improved road accessibility since the mid-1980s, and especially in the 1990s, between Las Palmas de Gran Canaria and the coastal areas of Telde and Arucas, has also played an important role. These infrastructure improvements increased the value of residential land, which was initially more affordable for residents relocating from the island’s capital. This period coincides with population decline in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria between the 1981 and 2001 censuses, followed by a subsequent increase recorded only in 2011, driven mainly by the development of new residential areas in the upper part of the city after the ring road was inaugurated between 1999 and 2003. Meanwhile, neighboring municipalities experienced rapid population growth—particularly Telde, where the population increased by two-thirds between 1981 and 2021. This demographic expansion intensified demand for residential land, contributing to rising housing costs over time.

Despite this, at the metropolitan scale, rental prices for multi-family housing follow a clear center–periphery pattern: rents in the capital city are significantly higher than in surrounding municipalities.

However, in the case of single-family housing, this pattern does not hold. Initially, lower land prices in coastal areas, especially in Telde, where single-family housing is predominant, have allowed for larger housing plots per household, often with adjacent open spaces, attracting higher-income residents. The spatial distribution of rental units recorded by SERPAVI at the intra-municipal level also reflects the prevalence of single-family housing in peripheral areas. Meanwhile, in central urban areas such as Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, single-family homes are present but typically clustered in traditional housing neighborhoods—a pattern also observed in some lower-income peripheral areas. These differences within single-family housing typologies are reflected, for instance, in median housing size, which is larger in satellite municipalities (Arucas: 175 m2; Santa Brígida: 165 m2) than in the capital city (162 m2). Along with factors such as housing age, these differences may contribute to variations in rental prices.

In this context, the inverse relationship between housing size and price per square meter must be considered. This generally reduces rental costs per unit of surface area compared to multi-family housing, although the total rental price remains higher, making single-family homes less accessible overall. In this way, there is a clear difference in rental prices depending on the type of construction, for example, on the coast of Telde, where we have a well-marked fragmentation of diffuse cities (with single-family housing for rent), with preferably medium and high rents. In contrast, multi-family houses, several hundred meters from the coastline, have an ostensibly lower rental price, not only because of a worse situation rent in relation to the former, but also because they have a smaller usable area, marking a clear fragmentation even within a few hundred meters within the same district. This can represent quite important differences in housing units, as we say, only a few hundred meters away (Figure 6).

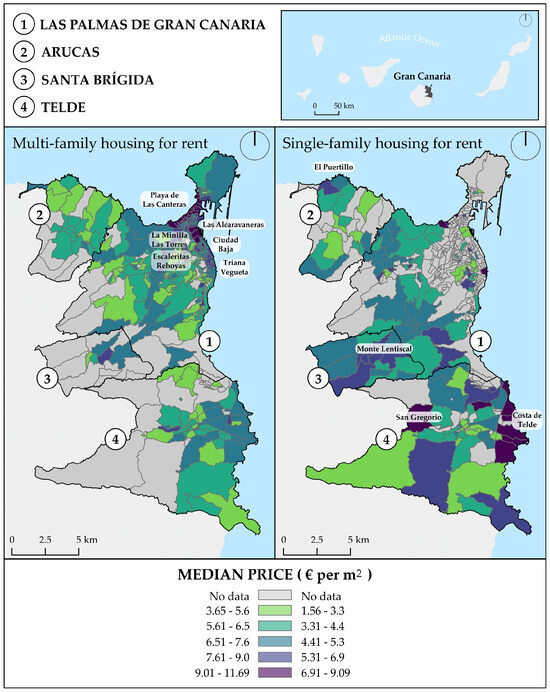

Figure 6.

Rental price per square meter by housing type in the metropolitan area of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria [63].

Following this logic, the data indicate a strong spatial correlation between high income levels and a high concentration of single-family homes, which also exhibit elevated rental prices (EUR/m2). This pattern is particularly evident in the border area between Las Palmas de Gran Canaria and Santa Brígida, as well as along the northern coastal sector of Telde. However, a local-scale analysis reveals that none of the four municipalities in the study area reach the regional average for rental prices. The highest values are once again concentrated in tourist-oriented municipalities, where foreign demand exerts considerable pressure on the rental market, making housing unaffordable for residents—especially in prime coastal areas that benefit from a mild year-round climate.

Overall, this trend aligns with the fact that Santa Brígida—the municipality with the highest average income in the Canary Islands—also has the greatest concentration of single-family housing and the highest rental prices. This high cost is further reinforced by the fact that its census tracts record some of the highest median prices per square meter for this housing typology within the study area. Nonetheless, the highest rental values are primarily found along the Telde coastal sector, near the beaches, as well as in semi-rural inland areas such as Santa Brígida, where additional factors—including the presence of golf courses and luxury residential developments (Caldera de Bandama)—contribute to high rental prices. Similarly, in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, rental prices are elevated in certain urban areas, likely due to gentrification processes driven by different factors: in the north, particularly in Guanarteme, as a result of touristification [64]; and in the historic district of Vegueta, due to tourism-driven heritage conservation efforts [65]).

The rental price distribution map per unit of surface area for multi-family housing reveals certain price-level and geographic trends, largely driven by the speculative processes previously discussed. However, the sample size is significantly larger (84.25% of census tracts have data for multi-family housing, compared to 33.60% for single-family housing), making it more spatially representative and analytically complex.

This cartographic analysis illustrates how these processes extend across a broader segment of the rental housing stock within this typology. Regarding touristification, the urban beach of Las Canteras constitutes a high-value shoreline, where rental prices progressively—but gradually—diminish toward the interior. However, high prices persist along three axes to the south, although not necessarily due to tourism.

The first of these, to the west, is associated with the new peripheries (Las Torres–La Minilla), where recent multi-family housing developments are characterized by high construction quality and proximity to key urban assets, including Las Canteras Beach, major facilities such as an island-wide hospital, and a large shopping center, as well as positional value linked to panoramic views.

The second, the eastern axis, popularly known as Ciudad Baja, forms a high-price corridor that has gained significant real estate value due to its high concentration and variety of services and amenities, including social clubs, a marina, and another small urban beach (Las Alcaravaneras). This axis extends along a rapid-connection highway toward the historic city center, encompassing the Triana and Vegueta neighborhoods. In both axes, the high rental price per square meter, combined with large median-sized multi-family housing units, places the median rental price among the highest in the city, making it one of the least affordable areas.

Finally, a third, spatially intermittent axis is located between the previous two, running north–south. This axis consists of fragmented urban spaces (Escaleritas–Las Rehoyas) and revalued multi-family housing due to its proximity and strong connectivity to central areas. However, in this case, the key factor influencing the high price per square meter is housing size. This area has a high concentration of small multi-family units (subsidized housing between 45 and 65 m2). The apparent contradiction in price levels follows an inverse scale effect: since costs do not decrease proportionally with size, the price per square meter remains high, yet the total rental cost remains relatively affordable, making it an accessible option for lower-income individuals.

In the satellite municipalities, such as Santa Brígida and Telde, the highest median rental prices for multi-family housing (EUR /m2) are found in their urban centers. However, due to low availability and limited demand for this housing typology in these areas, they do not hold a significant position within the metropolitan area’s multi-family housing market.

At the national level, all these municipal values rank among the highest. The four municipalities of the metropolitan area fall within the top decile for median rental price per square meter in both housing typologies, except for Arucas, which is positioned in the second decile for single-family housing.

4.3. Housing Affordability and Economic Effort in Access to Rental Housing

The analysis of rental prices within their broader social and economic contexts highlights several key issues.

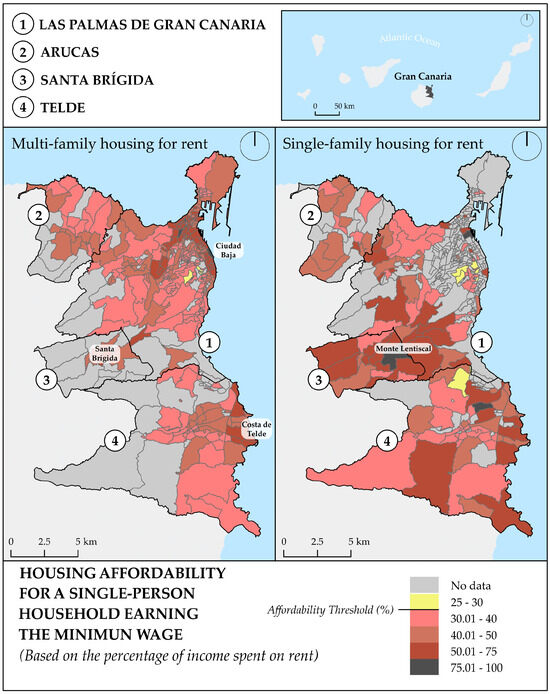

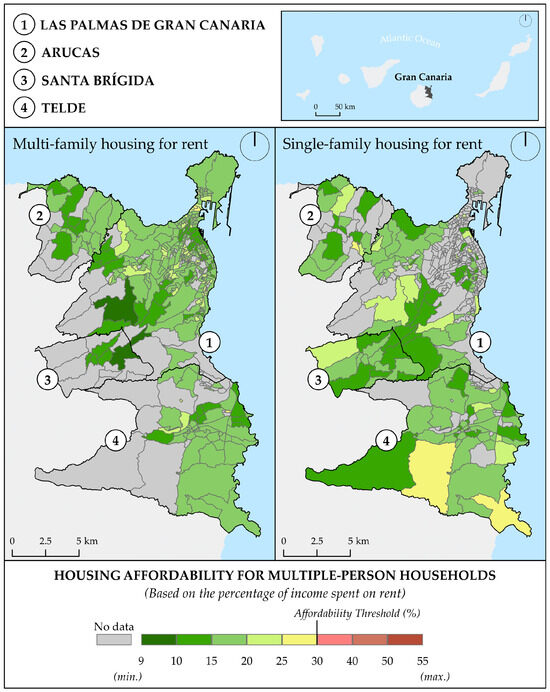

Focusing on some of the most vulnerable segments of the working class, a generalized lack of affordability is evident for those earning the SMI. In general terms, we observe how households rented with SMI income tend to be farther from the coast, especially when the type of rental housing is single-family. On the other hand, multi-family rental homes with SMI income are a little closer to the coastal strip, although, as can be seen in the map, this residential modality does not prevail on the coasts of the municipalities in our study either (Figure 7). In the absence of municipal-level data, the INE reports that in 2022, 17.10% of Spanish workers earned the SMI or less [66]. Consequently, the total population falling within this income bracket is necessarily larger, as it also includes non-working individuals, dependents, and other economically inactive groups.

Figure 7.

Affordability of the rental market for single-person households earning the SMI in the metropolitan area of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (2022) [63].

In 2022, the SMI was set at EUR 1166.66 gross per month. Comparing this figure with the average rental cost in the metropolitan area and applying the recommended affordability threshold (30% of income), it becomes clear that only 0.87% of the census tracts with available data would be considered affordable for multi-family housing, and 4.88% for single-family housing. In both cases, these areas are primarily composed of social housing or, predominantly, self-built homes (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Self-built homes in Risco de San Juan, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (2025) [67].

Moreover, a severe state of unaffordability is observed in approximately one-fifth of the census tracts (21.18%), where the median rental price exceeds half of the SMI. For multi-family housing, these census tracts are primarily concentrated along the previously mentioned eastern and western axes, particularly in the new pericentral areas and the high-price corridor of Ciudad Baja, with some locations experiencing critical conditions where rent exceeds 75% of income. Additionally, the urban centers of Santa Brígida and the Telde coastline present even more severe affordability issues, particularly for single-family housing. In this typology, 38.71% of census tracts fall into the previously defined severe unaffordability category.

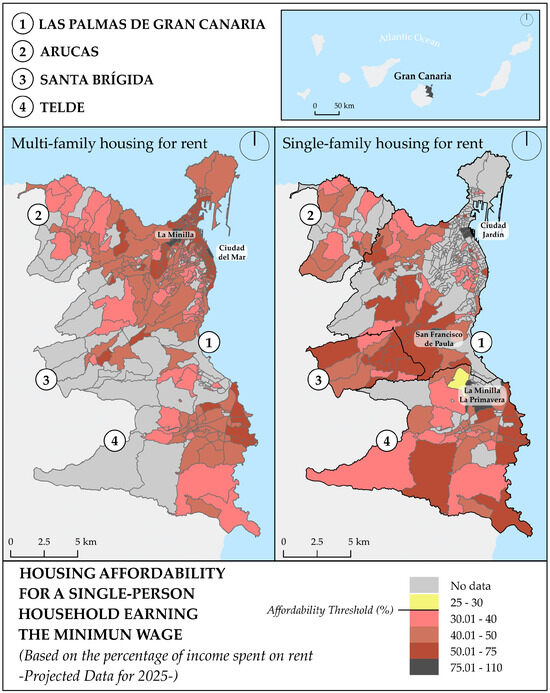

Given the time lag in data collection, the ongoing inflationary process, and the significant rise in rental prices, a correction factor has been applied using data from the real estate portal Idealista (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Affordability of the rental market for single-person households earning the SMI in the metropolitan area of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (2025) [63].

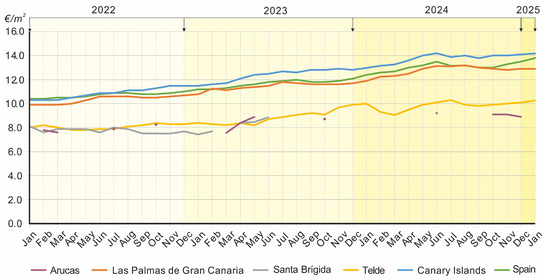

From 2022 to 2025, the Government of Spain increased the SMI to EUR 1381.33 gross per month, representing an 18.40% increase. However, in the absence of more up-to-date official data, Idealista estimates that national rental prices have risen by 32.69% over the same period, leading to greater strain on housing accessibility. According to this source, rental price increases have been geographically uneven. In the Canary Islands (Figure 10), rental prices have risen above the national average (37.86%), once again driven by the strength of the tourism sector. Meanwhile, in the study area, no municipality has reached the national average. In larger municipalities, such as the capital (30.30%) and Telde (28.75%), rental price increases have outpaced the rise in the SMI, exceeding it by more than 10 percentage points. In contrast, in Arucas (14.10%) and Santa Brígida (13.58%), rental price increases have remained below the SMI growth rate.

Figure 10.

Evolution of rental housing prices in the metropolitan area of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, the Canary Islands, and Spain [68].

As a result, the updated scenario indicates that for multi-family housing, there is no longer a single affordable census tract, with some areas where rental costs exceed 100% of the SMI (103.76%). The lack of balanced tourism planning—particularly in coastal and central areas—has further intensified this scenario by reallocating housing stock to short-term tourist rentals. This situation is even more severe for single-family housing, where the rental burden reaches 108.68% of the SMI. In this typology, only 1.56% of census tracts have rental prices within the affordability threshold, meaning that the required effort remains below 30% of the SMI. In other words, while market pressure intensifies in the most populated areas, increasing the number of severely strained cases (>75%), smaller peripheral municipalities with lower demographic weight have experienced a slight reduction in rental market pressure. However, prices remain beyond affordability levels. In these areas, the housing stock has not been shielded from the broader dynamics linked to tourism and external investment, which continue to exert upward pressure on prices without mechanisms to return value to local communities.

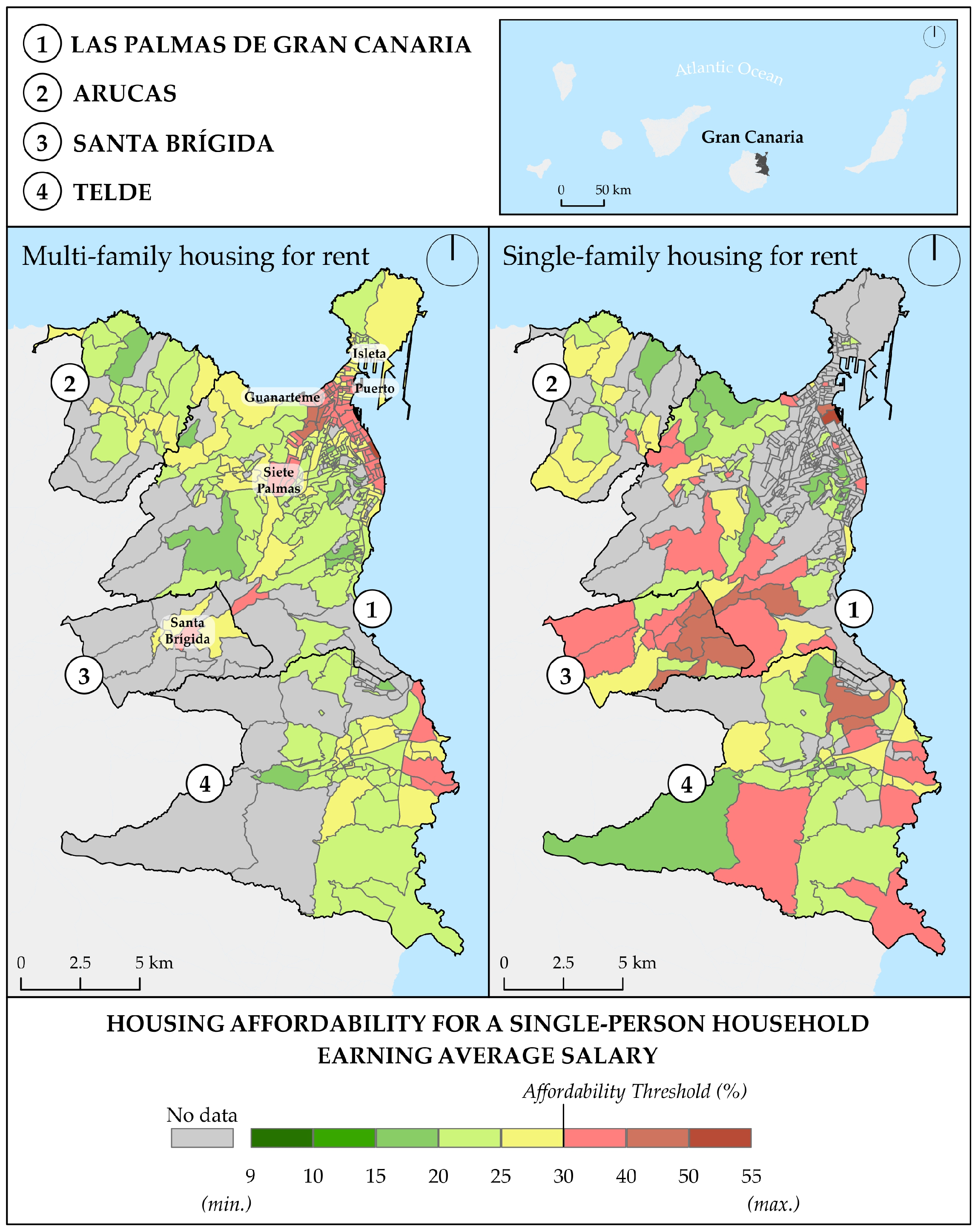

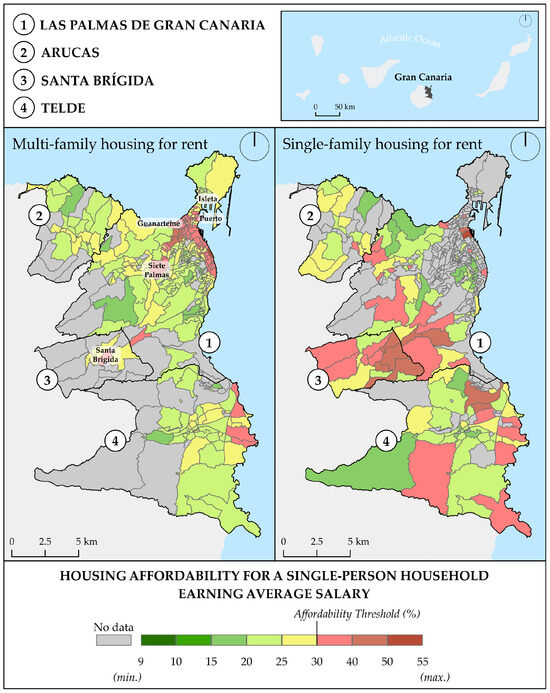

Conversely, when considering average salaries, it becomes evident that housing stress is also escalating to higher socio-economic strata (Figure 11). This impact is especially striking on the coast of Telde in single-family houses, exceeding 30% of the family income (red on the map). On the other hand, in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, this stress is identified, even broadly along its coastline and the modern commercial area of Mesa y López, in multi-family houses, with a smaller surface area. In short, the red stain on the map has spread even among the middle classes, highlighting an evident mechanism of urban fragmentation driven by high rental prices. In the absence of more geographically detailed data, the INE, through the Wage Structure Survey, provides the gross annual average salary by autonomous community. For the Canary Islands, which has the second-lowest salary level in Spain, the gross annual average salary in 2022 was EUR 23,096.92 (EUR 22,574.98 for women; EUR 23,588.70 for men), equivalent to EUR 1924.74 gross per month.

Figure 11.

Affordability of the rental market for single-person households earning the average salary in the metropolitan area of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (2022) [63].

At this salary level, housing unaffordability for multi-family housing becomes more localized, once again concentrating along the axes of new pericentral areas and the high-price corridor of Ciudad Baja in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, as well as in the coastal areas of Telde and the urban center of Santa Brígida. In contrast, for single-family housing, unaffordability extends across a wider area.

However, it is important to consider that inflation between 2022 and 2025, along with the uneven evolution of wages, could lead to the expansion of borderline unaffordable areas into the peripheral zones of the capital and Telde, as well as Arucas and Santa Brígida. Since this analysis is based on average salary levels, it suggests a trend toward widespread market stress affecting a large proportion of the population.

In any case, whether considering the SMI or the average salary, it is essential to acknowledge that housing cost estimates may be underestimated, as the comparison is made between gross income and final rental expenses.

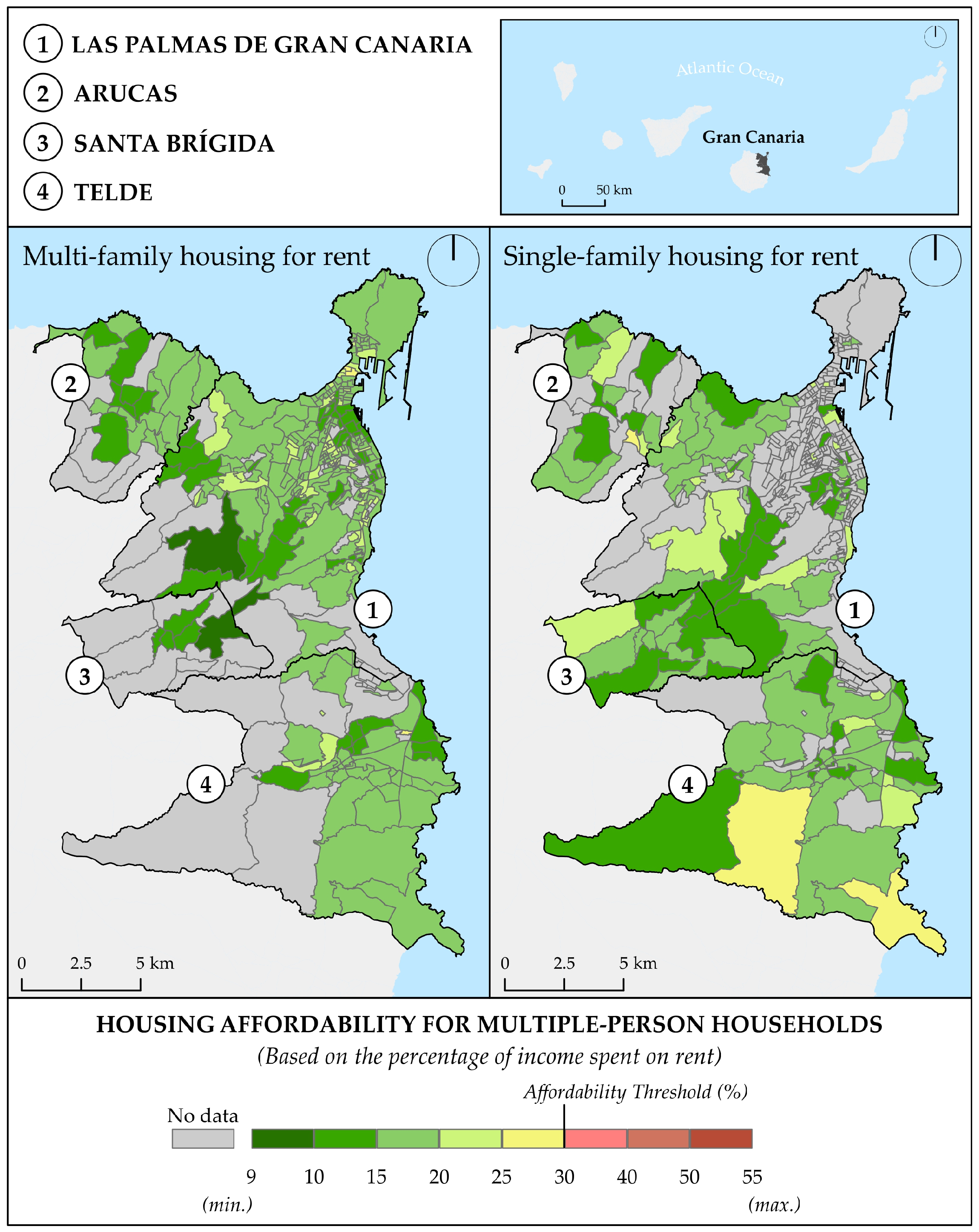

For this reason, the most accurate approach to measuring rental effort and affordability—both economically and geographically—is the comparison between average net household income and average rental prices at the census tract level (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Affordability of the rental market for households based on income level and rental price by census tract in the metropolitan area of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (2022) [63].

The map reflects a relatively favourable scenario in terms of affordability, with no census tracts experiencing severe market stress. However, this apparent stability is the result of urban metabolism, in which the population redistributes according to its economic capacity. This dynamic conceals the persistence of vulnerability and geographic immobility, as precarized groups remain in areas that do not exceed their affordability threshold, even though the data may suggest they are at the limit. However, these areas are often characterized by small or deteriorated housing conditions, in contrast to high-income households, which retain access to higher-quality living spaces. Moreover, the lowest-income census tracts are those closest to the affordability threshold, whereas wealthier populations are in a more advantageous position to withstand the inflationary crisis in the metropolitan area of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria.

Finally, in recent years—as rental prices have risen sharply without a corresponding increase in wages—the growing vulnerability in access to rental housing has increasingly been addressed through the expansion of co-living arrangements in major Western cities [59]. In the metropolitan area of Gran Canaria, and more specifically in the municipality of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, this phenomenon is also evident. Although a detailed analysis of this issue falls beyond the scope of this study, it could nonetheless serve as a useful indicator—along with the proliferation of motorhomes and recreational boats in the La Luz and Las Palmas marina being used as permanent residences—of the vulnerability situations previously discussed. This reality compels many individuals to seek alternative housing solutions rather than opting for the traditional rental of a property by a single person or family, particularly in areas where, as mentioned, rental costs exceed 30–35% of income. These processes suggest that while tourism and urban attractiveness generate economic activity, they may also intensify socio-territorial exclusion unless accompanied by compensatory public action. For all these reasons, the protests in the Canary Islands against tourism, especially against holiday homes, are taking on a greater dimension. This is the result of the significant increase in rental prices, without being accompanied by the same trend in wages and, therefore, in average income.

5. Conclusions

The housing crisis in the metropolitan area of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria is closely linked to preexisting socio-economic inequalities. This study highlights that in an economic context marked by inflation and the continuous rise in residential rental prices, the most vulnerable social groups have been pushed into precariousness due to their inability to secure affordable housing.

The analyzed data indicate that precarized groups are concentrated in the most vulnerable areas of the city, where wages are lower and unemployment is higher. This has also resulted in lower rental prices in these areas, although they are increasingly unaffordable for residents. This has created a vicious cycle that traps the precarized population in disadvantaged areas, further increasing their vulnerability, segregation, and fragmentation.

The residential rental crisis has contributed to the emergence of a new social class characterized by economic instability. Precariousness, once primarily associated with employment, has now extended to housing.

In the study area, housing challenges and rising prices seem to be increasingly associated with the impact of tourism and platform economies on the rental market, as recent social movements have brought public attention to this issue. The expansion of peer-to-peer (P2P) rentals appears to have reshaped part of the housing supply, with some properties previously available for long-term residential use being converted into short-term tourist accommodations. This trend is often described as part of a broader process of touristification, which may be contributing to growing pressure on the local population’s access to affordable housing. So far, public policies have proven insufficient to effectively address the issue. The lack of effective rental market regulation has allowed large property holders and real estate speculators to dominate the market. Additionally, Spain’s low percentage of social housing (only 2.5%) has forced many people to rely on the private rental market, where prices remain unaffordable for a large portion of the population. While tourism remains a key economic pillar in the Canary Islands, its growing influence on the housing market raises essential questions about the trade-off between economic vitality and social sustainability. Addressing this balance should be central to future housing and urban policy. In this context, the Canary Islands have recently approved fast-track procedures for urban development licenses to mitigate the housing shortage. Simultaneously, new draft legislation proposes that the number of beds in short-term vacation rentals should not exceed 10% of the total residential population within each census tract, as a means to regulate tourism pressure and ensure housing availability for residents.

Regarding spatial segregation and urban fragmentation in the study area, the data reflect how economic inequalities influence the geographic distribution of the population. Higher-income groups are concentrated in central or coastal areas, while precarized groups remain confined to less desirable districts, further perpetuating exclusionary dynamics. This segregation not only has economic implications but also social and political consequences. Future urban strategies must therefore integrate both housing and tourism policies, with recent legislative steps in the Canary Islands offering a starting point for more sustainable coexistence.

The limitations of the SERPAVI dataset—especially regarding temporal delays, underreporting, and spatial inconsistencies—reflect the constraints of an analytical framework shaped by the official data used by public administrations. Since SERPAVI is the only legally recognized source for identifying stressed residential market areas, its limitations condition both analysis and policymaking. This makes it necessary to complement the official framework with alternative strategies—such as triangulation with high-resolution data from real estate portals, targeted fieldwork, or the use of web scraping techniques—to enhance the spatial, temporal, and quantitative coverage of available data. Developing and applying these approaches represents a valuable line of work for future research, with the potential to improve the precision and depth of housing affordability assessments.

In short, without well-designed public intervention, this fragmentation will only continue to worsen, with serious consequences for social cohesion and equitable access to resources and opportunities. Expanding the supply of social rental housing, following the example of France, Germany, and the Netherlands, which have a significantly larger stock of social housing than Spain, is a necessary step, especially considering that public housing in Spain has fallen significantly in percentage terms since the 2008 real estate crisis, to represent only 2.5% of the total housing stock in Spain in 2022. This crisis led to the disappearance of official credit and a deep crisis in the savings banks, which were the credit institutions that financed social housing until then, which slowed the materialization of loans. In this context, the introduction of recently approved measures to encourage the private sector to build housing developments, such as the tax incentive by which investors reduce their tax base (Canary Islands Investment Reserve, RIC), is in line with reducing the stress of the rental real estate market in the Islands. The strictest regulations of the rental market would also go along this line. Rental price regulation is justified by the high percentage growth in prices, especially in the last five years, which has far exceeded wages. Therefore, the threshold of rents not exceeding 30% of household income, recommended in the Spanish government’s 2023 Housing Law, has been more easily exceeded, demonstrating the difficulty the population faces in accessing decent and affordable housing. Also, the controls on short-term rental platforms, and financial support for the most vulnerable sectors, could lay the foundation for the much-needed stabilization of the rental market in metropolitan areas such as Las Palmas de Gran Canaria.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.J.B. and J.Á.H.L.; methodology, V.J.B. and J.Á.H.L.; software, V.J.B. and C.M.M.; validation, V.J.B. and J.Á.H.L.; formal analysis, V.J.B.; investigation, V.J.B. and J.Á.H.L.; resources, V.J.B. and J.Á.H.L.; data curation, V.J.B., C.M.M., J.Á.H.L. and A.Á.R.O.; writing—original draft preparation, V.J.B., J.Á.H.L. and A.Á.R.O.; writing—review and editing, J.Á.H.L.; visualization, V.J.B.; supervision, J.Á.H.L.; project administration, V.J.B., J.Á.H.L., A.Á.R.O. and C.M.M.; funding acquisition, V.J.B., J.Á.H.L., A.Á.R.O. and C.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the “ERDF A way of making Europe” project: “Cities in transition. Urban fragmentation and new socio-spatial patterns of inequality in the post-pandemic context” (PID2021-122410OB-C31).

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arundel, R.; Torrado, J.M.; Duque-Calvache, R. The spatial polarization of housing wealth accumulation across Spain. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2024, 56, 1686–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrabadi, M.T.; Larimian, T.; Timmis, A.; Yigitcanlar, T. Mapping four decades of housing inequality research: Trends, insights, knowledge gaps, and research directions. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 113, 105693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewilde, C.; Lancee, B. Income Inequality and Access to Housing in Europe. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2013, 29, 1189–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Shahar, D.; Warszawski, J. Inequality in housing affordability: Measurement and estimation. Urban Stud. 2015, 53, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.E.; Rasmussen, D.W.; Haworth, C.T. Income Inequality and City Size. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1977, 59, 244–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum-Snow, N.; Pavan, R. Inequality and City Size. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2013, 95, 1535–1548. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/43554846 (accessed on 17 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hilman, R.M.; Iñiguez, G.; Karsai, M. Socioeconomic biases in urban mixing patterns of US metropolitan areas. EPJ Data Sci. 2022, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standing, G. El Precariado: Una Nueva Clase Social, 2nd ed.; Editorial Pasado y Presente: Barcelona, Spain, 2013; p. 302. ISBN 9788494100819. [Google Scholar]

- Hey, A.P.; Grimaldi, A.I. New Class Divisions? Elites and the Precariat at the Extremes of Social Class in the UK. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Soc. 2019, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.Y.; Park, J.; Kim, H.S. Emerging trends in housing policy in the UK: Focusing on its ongoing neoliberal transformation since 2010. Space Soc. 2015, 25, 227–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Feliciantonio, C.; Aalbers, M.B. The Prehistories of Neoliberal Housing Policies in Italy and Spain and Their Reification in Times of Crisis. Hous. Policy Debate 2017, 28, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macho Carro, A. El examen de proporcionalidad de los desalojos forzosos y su recepción en el ordenamiento español. Rev. Derecho Político 2023, 116, 297–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile. Comparador de Constituciones del Mundo: Derecho a la Vivienda. Available online: https://www.bcn.cl/procesoconstituyente/comparadordeconstituciones/materia/shelter (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Sánchez Ballesteros, V. Los límites de la función social de la propiedad en la modelización de las facultades del propietario como garantía de acceso a la vivienda digna para todos y la libertad de empresa. Rev. Derecho Civ. 2023, 10, 141–174. Available online: https://www.nreg.es/ojs/index.php/RDC/article/view/832 (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Image by Víctor Jiménez Barrado (a), and EFE Agency (b), 2024.

- Wang, X.-R.; Hui, E.C.-M.; Sun, J.-X. Population migration, urbanization and housing prices: Evidence from the cities in China. Habitat Int. 2017, 66, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arancibia, A. The Lifestyles of Space Standards: Concepts and Design Problems. Urban Plan. 2024, 9, 7800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Chen, R.; Xiong, B.; Jia, N.; Guo, X.; Yin, C.; Song, W. The Impact of Household Dynamics on Land-Use Change in China: Past Experiences and Future Implications. Land 2024, 13, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Cuevas, P.; Fernández Tabales, A. De la función residencial a la función turística en los espacios urbanos: Medición de los factores causantes a partir de herramientas digitales. Boletín Asoc. Geógrafos Españoles 2023, 99, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, E. Digital nomads in siliconising Cluj: Material and allegorical double dispossession. Urban Stud. 2019, 57, 3078–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parreño Castellano, J.M.; Domínguez Mujica, J.; Moreno Medina, C. Reflections on Digital Nomadism in Spain during the COVID-19 Pandemic—Effect of Policy and Place. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, I.A.; Rolnik, R.; Marín-Toro, A. Gestão neoliberal da precariedade: O aluguel residencial como nova fronteira de financeirização da moradia. Cad. Metrópole 2022, 24, 451–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banco de España-BdE. El mercado del alquiler de vivienda residencial en España: Evolución reciente, determinantes e indicadores de esfuerzo. In Documentos Ocasionales 2432; Banco de España: Madrid, Spain, 2024; pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Acioly, C.; Madhuraj, A. The Housing Rights Index: A Policy Formulation Support Tool; United Nations Human Settlements Programme-UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018; p. 25. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020/01/housing_rights_index_jan_7_low_resolution.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- López Ramón, F. El derecho subjetivo a la vivienda. Rev. Española Derecho Const. 2014, 102, 49–91. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2488729 (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Castelo Vargas, B.A. Configuración constitucional do dereito á vivenda. Cad. Dereito Actual 2013, 1, 29–36. Available online: https://www.cadernosdedereitoactual.es/index.php/cadernos/article/view/2 (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Barragán Robles, V.; Rodríguez Súárez, N.; Abellán Muñoz, J.C. Tenemos derecho, reivindicamos vivienda. La mercantilización como límite de los derechos humanos. Cuad. Relac. Laborales 2020, 38, 339–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debruche, A.F. Le droit au logement au Brésil: Entre intervention gouvernementale et théorie civile-constitutionnelle engagée. Les Cah. Droit 2020, 61, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’Igna Ecker, D. Desnaturalizando o Direito Social à moradia no Brasil: Ocupações urbanas como estratégia de assistência ao social. Diálogo 2021, 46, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurlat Aimar, J.S. El derecho a la vivienda en la jurisprudencia de la ciudad autónoma de Buenos Aires. Glosas hacia su reconocimiento pretoriano. Rev. Fac. Derecho 2021, 51, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Choeh, J.Y. Exploring the influence of online word-of-mouth on hotel booking prices: Insights from regression and ensemble-based machine learning methods. Data Sci. Financ. Econ. 2024, 4, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta Núñez, A.; Bélanger, H. Las desigualdades sociales y urbanas en la Ciudad de México: ¿Dónde queda el derecho a la vivienda? Kultur 2020, 7, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubens Cenci, D.; Seffrin, G. Mercantilização do espaço urbano e suas implicações na concepção de cidades justas, democráticas, inclusivas e humanas. Rev. Direito Cidade 2019, 11, 418–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Guo, F.; Du, Z. Learning from Peers: How Peer Effects Reshape the Digital Value Chain in China? J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, J.; Martínez, P.; Sequera, J. The neoliberal tenant dystopia: Digital polyplatform rentierism, the hybridization of platform-based rental markets and financialization of housing. Cities 2023, 137, 104245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majerowitz, M.; Allweil, Y. Housing in the Neoliberal City: Large Urban Developments and the Role of Architecture. Urban Plan. 2019, 4, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozo Carollo, I.; Morandeira-Arca, J.; Etxezarreta-Etxarri, A.; Izagirre-Olaizola, J. Is the effect of Airbnb on the housing market different in medium-sized cities? Evidence from a Southern European city. Urban Res. Pract. 2023, 17, 260–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay-Tamajón, L.; Lladós-Masllorens, J.; Meseguer-Artola, A.; Morales-Pérez, S. Analyzing the influence of short-term rental platforms on housing affordability in global urban destination neighborhoods. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2022, 22, 444–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biljanovska, N.; Fu, C.; Igan, D. Housing Affordability: A New Dataset. IMF Working Paper, WP/23/247; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Tulumello, S.; Dagkouli-Kyriakoglou, M. Housing Financialization and the State, in and Beyond Southern Europe: A Conceptual and Operational Framework. Hous. Theory Soc. 2024, 41, 192–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenyon, G.E.; Arribas-Bel, D.; Robinson, C.; Gkountouna, O.; Arbués, P.; Rey-Blanco, D. Intra-urban house prices in Madrid following the financial crisis: An exploration of spatial inequality. Npj Urban Sustain. 2024, 4, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, E.; López Martínez, A.; Ruíz Arias, M. Financiarización de la vivienda para alquiler y la precarización de las familias de bajos ingresos en Medellín (Colombia). Boletín Asoc. Geógrafos Españoles 2023, 96, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DesBaillets, D.; Hamill, S.E. Coming in from the Cold: Canada’s National Housing Strategy, Homelessness, and the Right to Housing in a Transnational Perspective. Can. J. Law Soc./Rev. Can. Droit Société 2022, 37, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaubrun-Diant, K.; Maury, T. Implications of homeownership policies on land prices: The case of a French experiment. Econ. Bul. 2021, 41, 1256–1265. Available online: https://www.accessecon.com/Pubs/EB/2021/Volume41/EB-21-V41-I3-P106.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Forns i Fernández, M.V. El paper dels serveis socials locals en l’aplicació de les polítiques d’habitatge en un context de crisi de l’estat del benestar. Una mirada des de Catalunya. Rev. Catalana Dret Públic 2023, 66, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listerborn, C. The new housing precariat: Experiences of precarious housing in Malmö, Sweden. Hous. Stud. 2021, 38, 1304–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, E. Regularización de Asentamientos Informales en América Latina; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; p. 52. ISBN 978-1-55844-202-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, V. The political frame of a housing crisis: Campaigning for the right to housing in Ireland. J. Civ. Soc. 2023, 19, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]