The Reciprocal Relationship Between Neighborhood Social Cohesion and Leisure-Time Physical Activity for Older Adults

Abstract

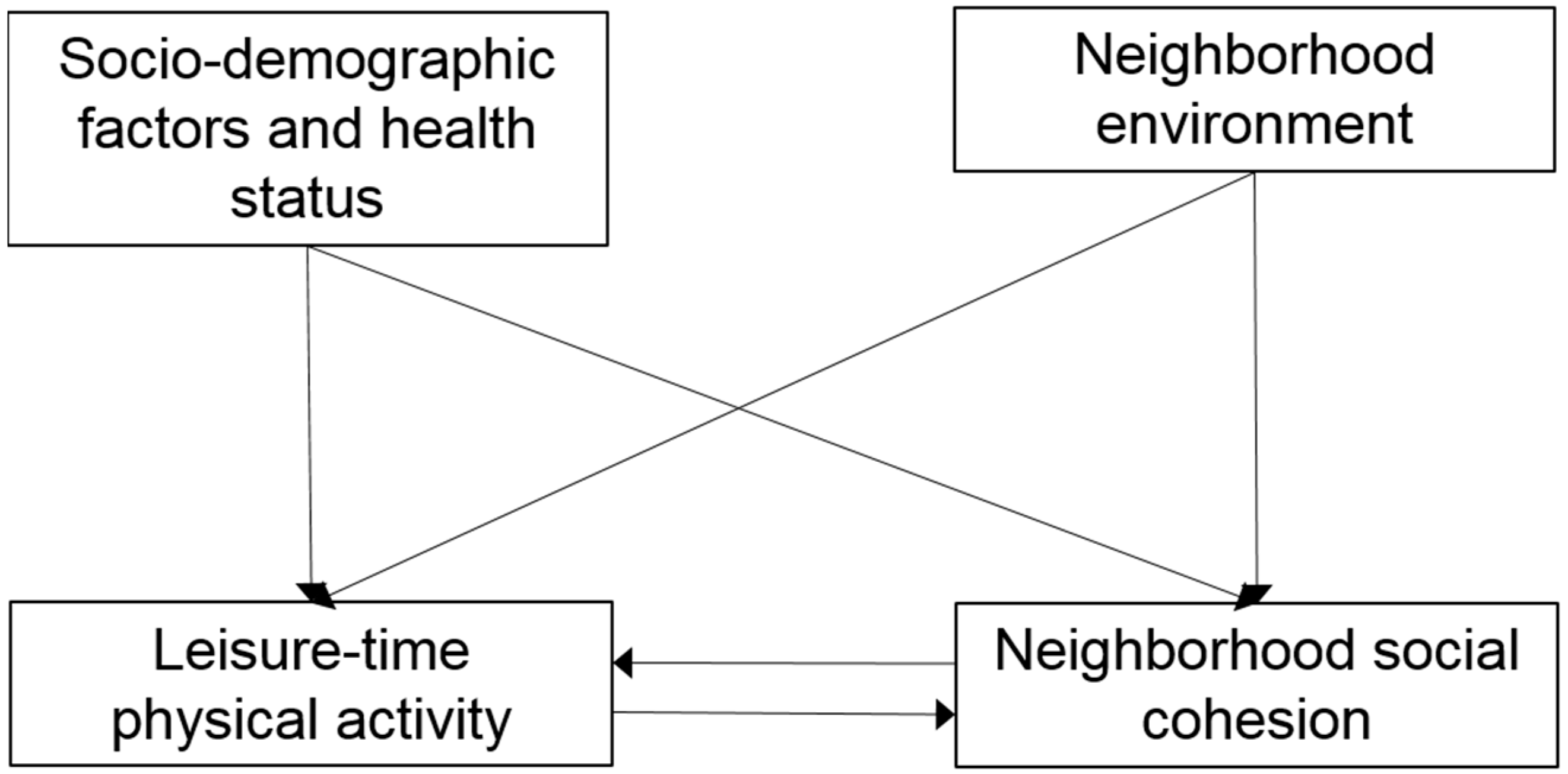

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Selection

2.2. Variables and Measurements

2.3. Statistical Analyzes

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pollack, C.E.; von dem Knesebeck, O. Social capital and health among the aged: Comparisons between the United States and Germany. Health Place 2004, 10, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Ageing; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report; Depatment of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McCormack, G.R.; Shiell, A. In serach of causality: A systematic review of the relationship between the built environment anf physical activity among adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.M.; Blaha, M.J.; Nasir, K.; Rivera, J.J.; Blumenthal, R.S. Effects of physical activity on cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 2012, 109, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical Activity Trends—United States, 1990–1998; Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2001; pp. 166–169. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop, D.D.; Song, J.; Arntson, E.K.; Semanik, P.A.; Lee, J.; Chang, R.W.; Hootman, J.M. Sedentary time in US older adults associated with disability in activities of daily living independent of physical activity. J. Phys. Act. Health 2015, 12, 93–101. [Google Scholar]

- van Stralen, M.M.; De Vries, H.; Mudde, A.N.; Bolman, C.; Lechner, L. Determinants of initiation and maintenance of physical activity among older adults: A literature review. Health Psychol. Rev. 2009, 3, 147–207. [Google Scholar]

- Cannuscio, C.; Block, J.; Kawachi, I. Social capital and successful aging: The role of senior housing. Ann. Intern. Med. 2003, 139, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kawachi, I.; Berkman, L.F. Social ties and mental health. J. Urban Health 2001, 78, 458–467. [Google Scholar]

- Lucumí, D.I.; Gomez, L.F.; Brownson, R.C.; Parra, D.C. Social capital, socioeconomic status, and health-related quality of life among older adults in bogota (Colombia). J. Aging Health 2015, 27, 730–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnam, R.D. Making Democracy Work; University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi, I.; Kennedy, B.; Glass, R. Social capital and self-rated health: A contextual analysis. Am. J. Public Health 1998, 89, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar]

- Leyden, K.M. Social capital and the built environment: The importance of walkable neighborhoods. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1546–1551. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi, I.; Kennedy, B.P.; Lochner, K.; Prothrow-Stith, D. Social capital, income inequality, and mortality. Am. J. Public Health 1997, 87, 1491–1498. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Phillipson, C.; Bernard, M.; Phillips, J.; Ogg, J. The Family and Community Life of Older People; Routledge: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, F. The Great Disruption: Human Nature and the Reconstitutionof Social Order; Profile Books: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, L.C.; Shapiro, S.; German, P. Determinants of physical activity initiation and maintenance among community-dwelling older persons. Prev. Med. 1999, 29, 422–430. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Fisher, K.J.; Bauman, A.; Ory, M.G.; Chodzko-Zajko, W.; Harmer, P.; Bosworth, M.; Cleveland, M. Neighborhood influences on physical activity in middle-aged and older adults: A multilevel perspective. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2005, 13, 87–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, C.E.; Dugan, E. Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. J. Aging Health 2012, 24, 1346–1363. [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy, K.R.; Bibeau, D.; Steckler, A.; Glanz, K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.; Zhu, X. Impacts of residential self-selection and built environments on children’s walking-to-school behaviors. Environ. Behav. 2015, 47, 268–287. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Yu, C.; Lee, C.; Lu, Z.; Mann, G. A retrospective study on changes in residents’ physical activities, social interactions, and neighborhood cohesion after moving to a walkable community. Prev. Med. 2014, 69, S93–S97. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C. Environmental supports for walking/biking and traffic safety: Income and ethnicity disparities. Prev. Med. 2014, 67, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Conn, V.S.; Marian, A.M.; Burks, K.J.; Rantz, M.J.; Pomeroy, S.H. Integrative review of physical activity intervention research with aging adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003, 51, 1159–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Lindström, M.; Hanson, B.S.; Östergren, P.O. Socioeconomic differences in leisure-time physical activity: The role of social participation and social capital in shaping health related behaviour. Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 52, 441–451. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Bij, A.K.; Laurant, M.G.H.; Wensing, M. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for older adults: A review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002, 22, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Survey Description, National Health Interview Survey, 2013; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey, 2013. Public-Use Data File and Documentation; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, J.A.; Sallis, J.F.; Conway, T.L.; Saelens, B.E.; Frank, L.D.; Kerr, J.; Cain, K.L.; King, A.C. Interactions between psychosocial and built environment factors in explaining older adults’ physical activity. Prev. Med. 2012, 54, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, E.B.; Ramsey, L.T.; Brownson, R.C.; Heath, G.W.; Howze, E.H.; Powell, K.E.; Stone, E.J.; Rajab, M.W.; Corso, P. The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity: A systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002, 22, 73–107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- King, A.C.; Castro, C.; Wilcox, S.; Eyler, A.A.; Sallis, J.F.; Brownson, R.C. Personal and environmental factors associated with physical inactivity among different racial–ethnic groups of US middle-aged and older-aged women. Health Psychol. 2000, 19, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routasalo, P.; Tilvis, R.S.; Kautiainen, H.; Pitkala, K. Effects of psychosocial group rehabilitation on social functioning, loneliness and well-being of lonely, older people: Randomized controlled trial. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 297–305. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, K.J.; Li, F.; Michael, Y.; Cleveland, M. Neighborhood-level influences on physical activity among older adults: A multilevel analysis. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2004, 12, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.; Wang, B. Influence of Neighborhood Walkability on Older Adults’ Walking Behavior, Health, and Social Connections in Third Places. Findings 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, T.D.; Wu, F.; Mody, D.; Bushover, B.; Mendez, D.D.; Schiff, M.; Fabio, A. Associations between neighborhood social cohesion and physical activity in the United States, National Health Interview Survey, 2017. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2019, 16, E163. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, K.; Overdorf, V. Incentives for exercise in younger and older women. J. Sport Behav. 1994, 17, 87. [Google Scholar]

- King, A.C.; Taylor, C.B.; Haskell, W.L.; DeBusk, R.F. Identifying strategies for increasing employee physical activity levels: Findings from the Stanford/Lockheed exercise survey. Health Educ. Behav. 1990, 17, 269–285. [Google Scholar]

- King, A.C.; Jeffery, R.W.; Fridinger, F.; Dusenbury, L.; Provence, S.; Hedlund, S.A.; Spangler, K. Environmental and policy approaches to cardiovascular disease prevention through physical activity: Issues and opportunities. Health Educ. Behav. 1995, 22, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Norman, I.J.; While, A.E. Physical activity in older people: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jette, A.M.; Rooks, D.; Lachman, M.; Lin, T.H.; Levenson, C.; Heislein, D.; Giorgetti, M.M.; Harris, B.A. Home-based resistance training: Predictors of participation and adherence. Gerontologist 1998, 38, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emery, C.F.; Hauck, E.R.; Blumenthal, J.A. Exercise adherence or maintenance among older adults: 1-year follow-up study. Psychol. Aging 1992, 73, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, P.; Lord, S.R. Predictors of adherence to a structured exercise program for older women. Psychol. Aging 1995, 10, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiles, J.L.; Leibing, A.; Guberman, N.; Reeve, J.; Allen, R.E. The meaning of “aging in place” to older people. Gerontologist 2012, 52, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brawley, L.R.; Rejeski, W.J.; Lutes, L. A group-mediated cognitive-behavioral intervention for increasing adherence to physical activity in older adults. J. Appl. Biobehav. Res. 2000, 5, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.L.; Mills, K.M.; King, A.C.; McLellan, B.Y.; Roitz, K.B.; Ritter, P.L. Evaluation of CHAMPS, a physical activity promotion program for older adults. Ann. Behav. Med. 1997, 19, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.C. Interventions to promote physical activity by older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oman, R.F.; King, A.C. Predicting the adoption and maintenance of exercise participation using self-efficacy and previous exercise participation rates. Am. J. Health Promot. 1998, 12, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarnio, M.; Winter, T.; Kujala, U.M.; Kaprio, J. Familial aggregation of leisure-time physical activity: A three generation study. Int. J. Sports Med. 1997, 18, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simoes, E.J.; Byers, T.; Coates, R.J.; Serdula, M.K.; Mokdad, A.H.; Heath, G.W. The association between leisure-time physical activity and dietary fat in American adults. Am. J. Public Health 1995, 85, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kerr, J.; Duncan, S.; Schipperjin, J. Using global positioning systems in health research: A practical approach to data collection and processing. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Variable | Measurement | General Adult (N = 34,412) | Older Adult (N = 7714) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted % (n) or M (SD) | 95% CI | Weighted % (n) or M (SD) | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

| Neighborhood social cohesion (L) | ||||||

| How much do you agree or disagree with the following statements about your neighborhood? | ||||||

| People in this neighborhood help each other out | 1 = definitely disagree; 2 = somewhat disagree; 3 = somewhat agree; 4 = definitely agree | 3.09 (0.90) | 3.08–3.10 | 3.27 (0.87) | 3.25–3.29 | <0.001 *** |

| There are people I can count on in this neighborhood | 3.17 (0.96) | 3.16–3.18 | 3.42 (0.85) | 3.40–3.44 | <0.001 *** | |

| People in this neighborhood can be trusted | 3.14 (0.93) | 3.13–3.15 | 3.39 (0.84) | 3.37–3.41 | <0.001 *** | |

| This is a close-knit neighborhood | 2.77 (1.02) | 2.76–2.78 | 2.96 (0.99) | 2.94–2.99 | <0.001 *** | |

| Leisure-time physical activity | ||||||

| Vigorous leisure-time physical activity | Minutes per week (continuous) | 103.72 (223.14) | 101.33–106.12 | 57.57 (174.27) | 53.57–61.57 | <0.001 *** |

| Light or moderate leisure-time physical activity | Minutes per week (continuous) | 126.34 (238.25) | 123.78–128.90 | 116.22 (233.07) | 110.88–121.55 | <0.001 *** |

| Leisure-time strengthening activity | Times per week (continuous) | 1.13 (2.73) | 1.10–1.16 | 0.87 (2.55) | 0.81–0.92 | <0.001 *** |

| Socio-demographic factors and health status | ||||||

| Male | 44.61 (15,351) | 44.08–45.13 | 40.20 (3101) | 39.11–41.29 | <0.001 *** | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 59.50 (20,474) | 58.98–60.02 | 70.72 (5455) | 69.70–71.73 | <0.001 *** | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 14.91 (5130) | 14.53–15.28 | 13.18 (1017) | 12.43–13.94 | ||

| Hispanic | 17.19 (5916) | 16.79–17.59 | 9.92 (765) | 9.25–10.58 | ||

| Other | 8.40 (2892) | 8.11–8.70 | 6.18 (477) | 5.65–6.72 | ||

| Education level | ||||||

| Less than high school | 13.07 (4488) | 12.71–13.43 | 18.72 (1439) | 17.85–19.60 | <0.001 *** | |

| High school | 47.76 (16,400) | 47.23–48.29 | 49.08 (3772) | 47.96–50.20 | ||

| College | 24.96 (8571) | 24.50–25.42 | 18.43 ((1416) | 17.56–19.29 | ||

| Graduate school | 14.21 (4880) | 13.84–14.58 | 13.77 (1058) | 12.99–14.54 | ||

| Married | 42.97 (14,749) | 42.45–43.50 | 41.57 (3199) | 40.47–42.67 | ||

| Family income | ||||||

| $0–$34,999 | 43.00 (13,909) | 42.46–43.54 | 53.53 (3726) | 52.36–54.71 | <0.001 *** | |

| $35,000–$74,999 | 30.85 (9979) | 30.34–31.35 | 30.45 (2119) | 29.36–31.53 | ||

| $75,000–$99,999 | 9.91 (3205) | 9.58–10.23 | 6.68 (465) | 6.09–7.27 | ||

| $100,000 and over | 16.24 (5256) | 15.85–16.65 | 9.34 (650) | 8.66–10.02 | ||

| Weight status | ||||||

| Normal weight | BMI < 25 | 36.91 (11,505) | 36.38–37.45 | 36.03 (2508) | 34.91–37.16 | <0.001 *** |

| Overweight | BMI ≥ 25 and < 30 | 35.45 (11,047) | 34.91–35.98 | 37.37 (2601) | 36.23–38.51 | |

| Obesity | BMI ≥ 30 | 27.64 (8615) | 27.14–28.14 | 26.59 (1851) | 25.56–27.63 | |

| General Adult (N = 34,412) | Older Adult (N = 7714) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Loading | S.E. | Factor Loading | S.E. | |

| Neighborhood social cohesion a | ||||

| People in this neighborhood help each other out | 0.860 *** | 0.002 | 0.865 *** | 0.004 |

| There are people I can count on in this neighborhood | 0.849 *** | 0.002 | 0.839 *** | 0.005 |

| People in this neighborhood can be trusted | 0.814 *** | 0.002 | 0.799 *** | 0.005 |

| This is a close-knit neighborhood | 0.786 *** | 0.003 | 0.772 *** | 0.006 |

| Cronbach’s α | 0.896 | 0.888 | ||

| Predictor | Dependent Variable | General Adult (N = 34,412) | Older Adult ((N = 7714) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Coefficients | R 2 | Standardized Coefficients | R 2 | ||

| Vigorous leisure-time physical activity | Neighborhood social cohesion | 0.005 | 0.069 | 0.012 | 0.043 |

| Light or moderate leisure-time physical activity | 0.023 | 0.023 * | |||

| Leisure-time strengthening activity | 0.003 | 0.024 | |||

| Gender (male) | −0.003 | −0.035 | |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Non-Hispanic black | −0.106 *** | −0.091 *** | |||

| Hispanic | −0.153 *** | −0.119 *** | |||

| Other | −0.064 *** | −0.033 ** | |||

| Education level | |||||

| Less than high school | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| High school | 0.026 ** | 0.025 * | |||

| College | 0.021 * | 0.032 * | |||

| Graduate school | 0.021 * | 0.056 * | |||

| Marital status (married) | 0.071 *** | 0.050 * | |||

| Family income | |||||

| $0–$34,999 | −0.135 *** | −0.058 * | |||

| $35,000–$74,999 | −0.070 *** | −0.019 | |||

| $75,000–$99,999 | −0.018 * | 0.004 | |||

| $100,000 and over | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Weight status | |||||

| Normal weight | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Overweight | 0.002 | −0.025 | |||

| Obesity | −0.029 *** | −0.037 * | |||

| Neighborhood social cohesion | Vigorous leisure-time physical activity | 0.004 | 0.172 | 0.011 | 0.104 |

| Light or moderate leisure-time physical activity | 0.227 *** | 0.221 *** | |||

| Leisure-time strengthening activity | 0.266 *** | 0.141 *** | |||

| Gender (male) | 0.088 *** | 0.056 *** | |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.016 ** | 0.029 * | |||

| Hispanic | 0.028 ** | 0.022 * | |||

| Other | 0.021 * | 0.027 * | |||

| Education level | |||||

| Less than high school | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| High school | 0.029 ** | 0.039 * | |||

| College | 0.046 *** | 0.052 ** | |||

| Graduate school | 0.030 ** | 0.065 *** | |||

| Marital status (married) | 0.008 | 0.010 | |||

| Family income | |||||

| $0–$34,999 | −0.065 *** | −0.058 * | |||

| $35,000–$74,999 | −0.034 *** | −0.042 | |||

| $75,000–$99,999 | −0.003 | 0.016 | |||

| $100,000 and over | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Weight status | |||||

| Normal weight | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Overweight | −0.022 ** | −0.018 * | |||

| Obesity | −0.037 *** | −0.023 * | |||

| Neighborhood social cohesion | Light or moderate leisure-time physical activity | 0.022 *** | 0.098 | 0.022 *** | 0.091 |

| Vigorous leisure-time physical activity | 0.248 *** | 0.224 *** | |||

| Leisure-time strengthening activity | 0.102 *** | 0.099 *** | |||

| Gender (male) | 0.024 * | 0.048 *** | |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Non-Hispanic black | −0.048 *** | −0.045 ** | |||

| Hispanic | −0.036 *** | −0.022 * | |||

| Other | −0.010 | −0.005 | |||

| Education level | |||||

| Less than high school | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| High school | 0.023 * | 0.011 | |||

| College | 0.026 ** | 0.02 * | |||

| Graduate school | 0.018 * | 0.024 | |||

| Marital status (married) | 0.004 | 0.005 | |||

| Family income | |||||

| $0–$34,999 | −0.014 | −0.069 ** | |||

| $35,000–$74,999 | −0.002 | −0.044 | |||

| $75,000–$99,999 | −0.001 | −0.031 | |||

| $100,000 and over | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Weight status | |||||

| Normal weight | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Overweight | −0.006 | −0.014 | |||

| Obesity | −0.022 ** | −0.031 * | |||

| Neighborhood social cohesion | Leisure-time strengthening activity | 0.003 | 0.129 | 0.024 | 0.058 |

| Vigorous leisure-time physical activity | 0.280 *** | 0.148 *** | |||

| Light or moderate leisure-time physical activity | 0.099 *** | 0.102 *** | |||

| Gender (male) | 0.042 *** | 0.030 * | |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.009 | −0.013 | |||

| Hispanic | 0.001 | −0.005 | |||

| Other | −0.012 | −0.009 | |||

| Education level | |||||

| Less than high school | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| High school | 0.032 ** | 0.024 * | |||

| College | 0.073 *** | 0.041 * | |||

| Graduate school | 0.060 *** | 0.052 ** | |||

| Marital status (married) | −0.021 | −0.024 | |||

| Family income | |||||

| $0–$34,999 | −0.068 *** | −0.084 ** | |||

| $35,000–$74,999 | −0.054 *** | −0.067 ** | |||

| $75,000–$99,999 | −0.021 ** | −0.021 * | |||

| $100,000 and over | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Weight status | |||||

| Normal weight | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Overweight | −0.025 *** | −0.014 | |||

| Obesity | −0.049 *** | −0.038 * | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, C.-Y. The Reciprocal Relationship Between Neighborhood Social Cohesion and Leisure-Time Physical Activity for Older Adults. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9040108

Yu C-Y. The Reciprocal Relationship Between Neighborhood Social Cohesion and Leisure-Time Physical Activity for Older Adults. Urban Science. 2025; 9(4):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9040108

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Chia-Yuan. 2025. "The Reciprocal Relationship Between Neighborhood Social Cohesion and Leisure-Time Physical Activity for Older Adults" Urban Science 9, no. 4: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9040108

APA StyleYu, C.-Y. (2025). The Reciprocal Relationship Between Neighborhood Social Cohesion and Leisure-Time Physical Activity for Older Adults. Urban Science, 9(4), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9040108