Abstract

Urban parks provide areas for human wellbeing and green space benefits in densely populated landscapes but cannot accomplish all their goals in isolation. They require assistance from collaborations to address challenges. The need for these collaborations is often codified in planning documents. We assisted Rock Creek Park (National Park Service, Washington, D.C.) in their considerations of where to place “partnerships” in their strategic plan by sourcing and summarizing goal topics, hierarchies, and relationships from peer park plans. Using textual coding and network analysis approaches, we examined strategic planning documents from park system entities across the 20 largest urban areas in the United States. We found that, topically, Rock Creek Park’s five initial strategic planning goal topics—safety, access, stewardship, community engagement, and employee engagement—were common and both inward and outward-facing goals. Hierarchically, “partnerships” was routinely considered as a primary goal (a stand-alone topic) and as an integrated secondary goal (supportive within other topics). Additionally, we identified “community building” as an important, outward facing “assistance” goal, differentiated from “partnerships” in audience and encompassing how a park shows up for the urban community and demonstrates its value to the region. We discuss these findings toward urban park planning processes.

1. Introduction

Urban parks are vital components of the cityscape, providing recreation and green space benefits in heavily developed areas. Yet, urban parks are also challenged by this complex geography of political boundaries, overlapping interests, high population densities, and the need to accomplish many goals through collaboration. When defining their approaches to collaboration in strategic plans that capture visions of desired conditions, questions arise of what topics to include, whether to include them as overarching goals or as approaches to other goals, and how these intersect with the needs for assistance. We address this challenge in this study, through a review of urban park strategic planning documents and an applied focus on the utility for one such urban park’s collaboration and strategic planning—Rock Creek Park in Washington, D.C., U.S. Though our focus of the research and application is within the U.S., our findings about urban park plan goal structure transcend one country and are of use for urban parks and associated urban planners worldwide.

1.1. Urban Parks and Their Collaborative Efforts

Urban parks play a special role in cityscapes. With two-thirds of the world’s population predicted to live in urban areas by 2050 [1], the role and importance of these parks is expected to become even more pronounced. They provide a third space (separate from home or work) for urban residents to increase their quality of life and wellbeing through recreating and engaging with natural and/or cultural features and themes [2]. They also play important roles in climate change mitigation [3,4], species biodiversity [5], and an extensive range of human wellbeing and ecosystem conservation goals [6,7,8,9,10]. Initiatives such as the U.S. National Park Service’s Urban Agenda highlight these roles, and, importantly, the connections that urban parks and programs create with local, urban populations [11,12]. Specifically, this federal attention on national parks in U.S. urban areas showcased these spaces’ role in providing recreation, education, and ecology benefits to the larger cityscape [12]. It also emphasized the need for these parks to maintain and enhance their relevance with local populations by understanding community visions for a vibrant and livable cityscape and where parks and related programs fit into this [11,12,13]. This is especially salient given the body of work on constraints to urban park visitation by locals and efforts to negotiate and navigate these constraints for reasons of equity, inclusion, and access across a diverse urban population [14,15,16,17]. Though the Urban Agenda has sunset, the emphasis on these themes (i.e., core concepts enhanced public relevance, aligned internal resources and connections, and a strengthened culture of collaboration internally and with communities) continues to resonate across U.S. cityscapes [13].

It is vital to recognize that urban parks cannot accomplish all their goals in isolation; they require collaborative assistance [18,19]. This is pragmatic for park functions but also aspirational toward goals of local relevance and engagement [13,20,21,22]. For example, collaborations that focus on multiple points of resonance across the local population (i.e., building deep and broad connections) [23] can assist in strengthening stewardship connections within a local community and, thus, ultimately aid an urban park in its mission, even if the initial collaboration was not focused on a specific park need. Indeed, community-focused park collaborations in urban areas are imperative [24]. Collaborative efforts in the Washington, D.C., area on improving National Park Service interpretation and cultural resources collaborative efforts and with the local community [25] exemplify how efforts around principles of collaboration competencies can benefit urban park systems and their city context [26,27]. Similarly, “parknerships” in the San Franscico Bay Area among the National Park Service, other park agencies, and community partners demonstrate how considering the urban context, cultivating a collaborative mindset, establishing a supported structure, and embracing the unknown through trialing creative ideas can assist parks to progress sustainably toward a common goal of public relevance [22]. This type of approach—collaborations beyond park boundaries and encompassing on a regional scale—is increasingly vital in our complicated world and in response to issues such as climate change [28,29], park integrity and policy compliance [30], spatial scales of social inequities [31], conceptualizations of urban sustainability [32,33], and social-ecological systems [34].

Collaborations may happen spontaneously, but they are also carefully attended to in planning efforts to increase efficiency and efficacy. The inclusion of partnerships and wider community-focused engagements in planning has been a noted area for improvement [13,20,35,36]. In-depth consideration of specific communities and the inclusion of whole communities is essential in urban park planning and innovative means can assist in this effort (e.g., a park “card game” to surface community priorities [35], community-led events in parks in low-income neighborhoods to further inclusive park design [37]). However, before engaging communities in the actual actions, goals and objectives should be framed in planning efforts [22,38]. Identifying collaborations or assistance generally as a goal is a common approach, as is the insertion of collaborations/assistance as a supporting objective across goals. Differentiating the types of collaboration is also useful for clarity of intent and specific callouts for integrating community voices [13,22]. However, questions remain about inspiration and implementation across urban park contexts, as this information remains scarce [38]: How do we frame the need for collaborative assistance and related partnerships and community-centered engagements in planning efforts?

1.2. The Case of Washington, D.C., U.S., Urban National Parks, Including Rock Creek Park

There are several urban parks throughout the U.S. capital and greater region, 90% of which are managed by the National Park Service and total 20% of the city area [39]. For example, there are 25 parks managed by the National Park Service within D.C. and another 15 in the immediate region. All these offer visitors with opportunities for historic and cultural engagement, nature appreciation, and a third space for passing time. They also relate interpretative themes that resonate with local communities and the nation’s stories. Anacostia Park, for example, contains the 11th Street Bridge, which was once a dividing line for racial segregation within the city. The integral partnerships with multiple entities and community organizations have centered on deepening understanding of this geography and connections across it through planning efforts [40]. These partnerships have furthered these goals but also highlighted persistent racial and class tensions within this context, speaking to the need for enhancing community engagement and acknowledging power structures and injustices in planning efforts [40].

The National Park Service’s Urban Agenda, an initiative to focus on the 40% of the agency’s portfolio that exists in urban areas [11], also focused on national parks in the D.C. area in the years around the 2016 National Park Service Centennial. The D.C. Urban Fellow worked explicitly to enhance collaborations among parks and communities, and recommended that community building is crucial, with a pronounced need for National Park Service advocates to work with, and for, underrepresented urban communities for equitable investment of park planning and access across the D.C. landscape [39]. Other examinations of the cities included in the Urban Agenda found similar themes. For example, work on how the National Park Service can enhance its regional relevance on cityscapes centered the concept of examining community needs and goals alongside those of the National Park Service when planning and implementing efforts [13], enacting these dual partnership and community building efforts through collaborations with diverse entities [21] and through cultures of trust [20], and undertaking organizational changes to shift how resources within the agency are allocated to promoting internal and external collaborations [41].

Rock Creek Park is a National Park Service park in Washington, D.C., that is comprised of a large land area of natural and cultural features, as well as 99 scattered small parcels (e.g., statues, roundabout green spaces) [42]. The park was established in 1890, along the Rock Creek waterway, a tributary of the Potomac River. In 1933, Rock Creek Park merged into the National Capital Parks unit of the National Park Service, which is a group of D.C. area parks administrated within regional approaches. Today, the main park unit is 1754 acres and consistently receives around 2 million visitors per year [43]. The park itself has several features attracting visitors and partners, such as an extensive trail system, a golf course, an amphitheater, historic structures (e.g., mills, bridges), and a diversity of maintained and natural habitats. Paved roadways are popular for commuting and pleasure driving within D.C., and portions are closed to vehicles on the weekends to facilitate recreation on these miles of pavement.

Our case study centered on addressing questions from Rock Creek related to how and where to include partnerships as a goal topic in their next strategic plan. The park works in collaboration with hundreds of existing partners, from formal agreements for ongoing functions to ad hoc assistance in a singular project or event. Other organizations and groups are also functioning as “unofficial” collaborators within Rock Creek to support the park’s capacity and would prefer clarity on role definition. Beyond this, the park is aware of still other organizations and entities who may be potential partners in assisting the park in fulfilling its mission and meeting its corresponding priorities. In Rock Creek’s planning process, a question was whether to explicitly name “partnerships” as a goal in the strategic plan or instead embed partnership considerations within the other goals as a support. This can be considered as a question of hierarchy: Should the topic of partnerships be a primary or secondary goal? This question resonates beyond Rock Creek Park, as other urban parks consider whether to allocate devoted attention to partnerships as a stand-alone goal of primary importance, or as a secondary goal woven across and throughout primary goals on different topics.

1.3. Study Aim

We present the following analysis and discussion of urban park strategic goals and hierarchy to assist the park in this decision. To do so, we examined strategic planning documents from park and park system entities across the 20 largest urban areas in the U.S. At Rock Creek Park, five primary goals had been initially identified: (1) safety, (2) access, (3) stewardship, (4) community engagement, and (5) employee engagement. Partnerships as a primary goal would imply that it would be an additional sixth topic. Partnerships as a secondary goal would imply that this topic should be discussed as supportive within the existing five primary goals. For clarity, we align our presentation of results examining goal hierarchies and goal relationships in urban park strategic plans, centering on the topic of “assistance” that includes partnerships. Our trifold guiding question concerned how urban park strategic goals are framed:

- How are urban park strategic goals framed topically—inward and outward facing?

- How are urban park strategic goals framed hierarchically—primary and secondary?

- How are urban park strategic goals framed relationally—between and within goals?

We interpret these results toward the needs and potential actions of Rock Creek and share more broadly what the goals’ framings and relationships suggest about prioritized efforts for park-community collaborations across urban park systems throughout the U.S. and beyond.

2. Materials and Methods

To address this need and associated questions, we examined park strategic plans in urban areas across the U.S. and analyzed their goals’ primary and supportive topics qualitatively and quantitatively. Strategic plans represent specific efforts to produce a concentrated and prioritized set of desired conditions and actions toward these conditions by an organization [44]. In the context of parks and recreation, strategic plans tend to contain goals and objectives, baseline and forecasted data, suites of alternatives with preferred one(s) identified, and an evaluation process/schedule [38]. We constrained our scope to strategic plans meeting at least the condition of goals and objectives, for parity of comparison across plans and to the intent of Rock Creek Park.

2.1. Scope and Inclusion Criteria

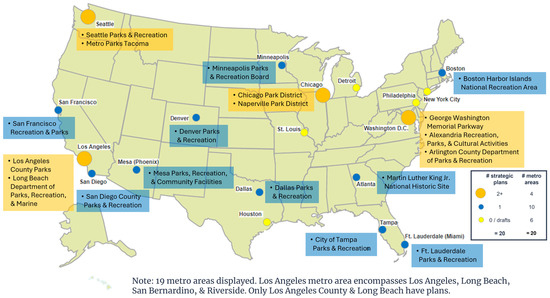

First, we defined our “urban” scope as the 20 most populous metropolitan areas in the U.S., based on the 2020 U.S. Census [45]. This parameter of 20 metropolitan areas was chosen in conversation with Rock Creek Park staff, to encompass metropolitan areas similar in size to Washington, D.C. and potentially with similar park planning topics and complexities. Second, within these 20 metropolitan areas, we harvested publicly available strategic plans of all available jurisdictional levels, available as of our January 2022 data collection (all 20 plans cited as [46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65]) (Figure 1). This encompassed county and regional park systems, city park districts, Metropark systems, and urban National Park Service parks. In this way, a metropolitan area could be represented in our dataset through multiple park jurisdictions and strategic plans.

Figure 1.

Distribution and park agencies of the 20 strategic plans within the 20 most populous U.S. metropolitan areas analyzed in this study. Number is abbreviated as “#” in the figure.

Third, if a jurisdiction had more than one version of a strategic plan available, we harvested the most recent plan at the time of data collection. In this dataset, the plans’ creation dates range from 2002 to 2021 and cover different amounts of time, from exact and near-term (e.g., 5- or 10-year strategic plans) to undefined (i.e., no sunset date). This yielded our dataset of 20 strategic plans, with six metropolitan areas having no park strategic plans or only draft plans (not considered in our analysis), 10 areas having one plan, and four areas having two or more plans (Figure 1). There are some notable omissions. For example, the New York City Parks Department has many forward-looking plans, including initiatives for an equitable future [66], but does not have a structured strategic plan that fits into the scope of this study.

2.2. Goal Coding Approach

We manually examined the 20 plans using a qualitative content analysis approach [67] and derived quantitative metrics from this textual information (e.g., counts of occurrences). The coding approach centered on six a priori codes, representing the initial strategic goals of Rock Creek Park: safety, access, stewardship, community engagement, and employee engagement, plus partnerships. Starting with these codes allowed us to examine how common these goals were across other parks’ plans, and how these other parks were referring to and prioritizing them.

Beyond these six codes, we used an iterative coding approach, re-evaluating each strategic plan as more goal content areas were found in other plans and the coding structure, thus, expanded [67,68]. This meant that each plan was reviewed and recoded multiple times until no new codes were added for goals. The wording related to each goal varied, and plans referred to “goals” as goals, priorities, themes, objectives, etc. Our iterative coding approach and deep familiarity with the data allowed us to understand the breadth of language and intention addressing a particular coded goal. Beyond internal team check-ins for bias and consistency, we also engaged in routine expert consultation with other academics and park practitioners, which assisted in the validity of our coding approach.

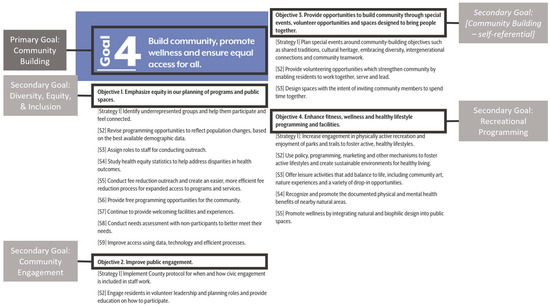

Because the intention of this work was to examine primary and secondary goals, we coded for these two levels across the plans using this iterative, validated format. Primary goals were often overarching themes with a broad or main goal to achieve, while secondary goals were embedded as supportive goals under this broader umbrella. Each plan had a hierarchical goal structure in its organization. While some plans stopped at secondary goals, others branched into tertiary goals, sub-categories of metrics, and/or specific actions (e.g., Figure 2). We used the secondary level as a delineation for inclusion, to (1) have a common basis across plans, (2) avoid coding for lesser priority goals, and (3) retain the focus on goals rather than co-mingled metrics and actions included as tertiary goals or beyond. We did not code a secondary goal if it pertained to the same code applied to the primary goal, as it is common and expected that there are self-references within a hierarchy and our focus was on cross-topic hierarchical integrations.

Figure 2.

An example of plan hierarchy with primary, secondary, and tertiary goals [65]. Call-out boxes indicate our coding strategy, including not coding a self-referential secondary goal.

2.3. Goals Network Analysis Approach

After coding the plans’ primary and secondary goals, we examined the goals’ relative prevalence and importance through a network analysis [69]. This analysis investigated the relationships among secondary goals based on their overarching primary goal, using measures of centrality in a directional one-mode network analysis design [70]. Centrality quantifies the number and, more importantly, the breadth of relationships each goal has with others, and standardizes these on a 0–1 scale. For example, if the goal of “safety” was both a secondary goal across many primary goals and a primary goal that had many secondary goals within it, it might have a higher centrality value (e.g., closer to 1). However, if it was less prevalent across secondary and/or primary levels, it might have a lower centrality value (e.g., closer to 0).

Understanding centrality values assists in considering how important (i.e., abundant and connected) a goal is. As each network is unique, however, there is no absolute threshold for what is defined as “high” or “low” centrality. To aid in interpreting the values in this dataset, we categorized our results by relative centrality [21]—dividing the range of centrality values seen in this context into thirds. The resulting delineations of “high,” “medium,” and “low” relative centrality provide an opportunity to summarize the centrality measures into useful groupings and discuss the implications of these quantitative measures alongside the qualitative analysis. Thus, this pairing of methods about goals may be vital for urban parks to consider for scaffolding strategic plans’ goal topics and cross-referenced supports within their own contexts.

3. Results

3.1. Goal Topics

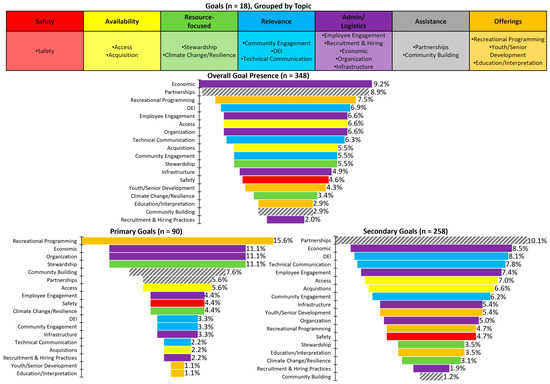

We found 18 goals referenced in the primary and secondary position (Table 1). Six of these were the a priori goals of interest to Rock Creek and the other 12 were emergent. We grouped these 18 goals into seven topics for a greater understanding of how multiple goals relate conceptually (Table 1), though the instances of mentions in each plan, and our analysis, mostly focus on the goal level.

Table 1.

Names, descriptions, and examples of the topics and goals coded within the strategic plans.

Goals can pertain to uses, users, and issues inside park boundaries (i.e., inward or park-focused) and/or groups, communities, or contexts outside of park boundaries (i.e., outward or context-focused). Each has correspondingly different audiences. We found evidence of both, as expected in park planning that addresses the needs of parks and the communities they serve. For example, the five goals associated with park administration and logistics (i.e., employee engagement, recruitment and hiring practices, economics, internal organization, and physical infrastructure) are all inward-facing and related to the park’s organizational needs and internal functions. Conversely, the three goals associated with park offerings (i.e., recreation programming, youth and senior development, and education and interpretation) are all outward-facing and related to content, interactions, and events with visitors, the local community, and/or specific audiences therein.

“Assistance” sums the park or park system’s collaborative connections to other entities. It encompasses both inward and outward-facing goals and, therefore, multiple audiences. We explicitly differentiate “partnerships” and “community building” based on this inward or outward-facing intent. Though we intended to code “partnerships” collectively for Rock Creek’s purposes, it became apparent within the data that these two complementary codes were needed to distinguish the audience. Though both examine ways in which relationships and collaborations assist the park, “partnerships” are aimed at enhancing the park’s capacity to successfully carry out its functions whereas “community building” is aimed at enhancing the community context around the park and supporting community or city-level ambitions.

3.2. Goal Hierarchy

The 18 goals were present across the dataset collectively 348 times: 90 times in a primary position and 258 times in a secondary position (Figure 3). The five most common primary goals were recreation programming, stewardship, economics, organization, and community building. Plans averaged four to five primary goals, each with two to four secondary goals, though there was a wide range across the plans. Each goal was represented in 1–14 instances in the primary position and 2–26 instances in the secondary position. Each goal was represented at least three times in the dataset but not every goal was represented in every plan.

Figure 3.

Summary of goals’ frequencies overall and in the primary and secondary positions, colored by topic. The two “assistance” goals of partnerships and community building are differently shaded to emphasize their positionality across goals. DEI abbreviation = Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.

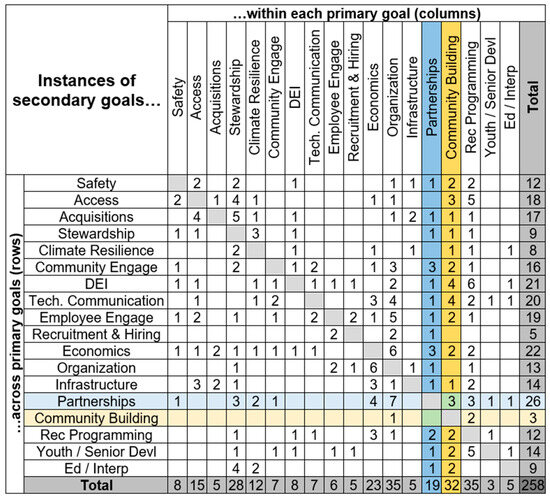

Next, we examined the 258 instances of secondary goals and their intersections within and across primary goals (Figure 4). The five most common secondary goals were partnerships; economics; diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI); technical communications; and employee engagement. The five primary goals containing the most secondary goals (i.e., the highest number of supports embedded) were organization, recreation programming, community building, stewardship, and economics.

Figure 4.

Number of incidences of secondary goals within and across primary goals, with a highlight on partnerships (blue) and community building (yellow) and their intersections (green).

The most frequent pairing was a primary goal of organization, supported by partnerships. Other oft-mentioned pairings between primary and secondary goals were (1) recreation programming with (a) diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), (b) access, or (c) youth and senior development; (2) organization with (a) economics or (b) employee engagement; economics with organization; and (3) stewardship with acquisitions.

Hierarchical pairings depict reciprocity across the primary-secondary goal hierarchy. For example, recreation programming is a standard park engagement and the most referenced primary goal (15.6%; Figure 4). The 14 instances of recreation programming as a primary goal collectively referenced 15 secondary goals in 35 instances, which are the highest values seen. This indicates that recreation programming is an important high-level goal and that many other goals are seen as supportive of it. However, recreation programming was only mentioned as a secondary goal in 12 instances across eight primary goals (i.e., below-average values seen). Together, this indicates that recreation programming may be somewhat siloed in its contributions: though it is an important main goal in strategic plans, its relevance is not reciprocated on the supportive level.

The relative differences of the two “assistance” goals indicate that each is considered differently in its contribution to strategic planning. Community building was almost as numerous and widespread as recreation programming. Though it was represented in the primary position only seven times, within those were 15 secondary goals totaling 32 instances. This indicates that community building is a moderately emphasized primary goal but heavily supported by diverse secondary goals. In a more exaggerated way than recreation programming, reciprocity is lacking when community building is a secondary goal. It only supported two primary goals, totaling three instances. Thus, while community building is an important main goal in strategic plans, it is often siloed and rarely integrated as a support to other goals.

Partnerships exhibit a different pattern. Their five instances as a primary goal collectively contain 14 secondary goals totaling 19 instances. They are, thus, a moderately emphasized primary goal and moderately supported by diverse secondary goals. When partnerships themselves are a secondary goal, they are similarly referenced, supporting 10 primary goals in 26 instances. Therefore, there is general reciprocity between partnerships as a moderately emphasized and integrated overarching main and supportive goal across strategic plans.

Figure 3 also presents the goals’ overall and hierarchical placements, grouped/colored by topic. The patterns of primary to secondary level placement changes are illustrated, and strikingly for “assistance” goals. This depiction introduces other higher-level patterns too. For example, “relevance” goals are less common primary goals but very common secondary goals, implying that they are viewed mostly as supportive. “Resource-focused” goals are conversely common primary goals but relatively uncommon secondary goals, implying that they are viewed more often as main goals. “Administrative/logistics” goals are spread throughout, demonstrating the importance of these goals at both levels of strategic planning.

3.3. Goal Relationships

Finally, we explored combinations within the goal network. This inquiry examined the relationships among the web of secondary goals connecting content across strategic plans. It complements the previous results on single-goal topics and two-level goal hierarchies with an investigation of relationships among all goals at the secondary level.

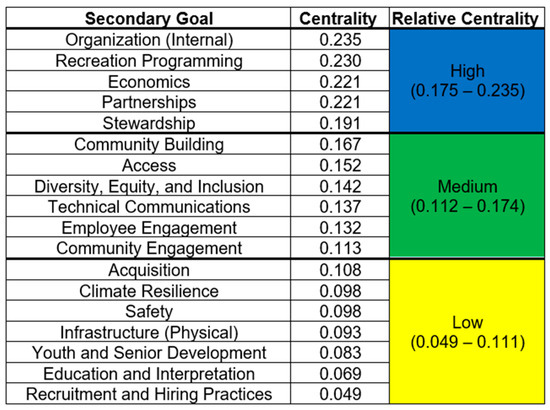

This approach allowed us to determine which goals were more central across the plans (Figure 5) and, thus, provided a measure of relevance for parks to consider in framing their own strategic goals. Centrality values ranged from 0.049 (recruitment and hiring practices) to 0.235 (organization). The low, medium, and high relative centrality groupings within this range (Figure 5) correspond to goals that are of relatively small, average, or large relevance to the network. With these delineations, the most central/relevant are organization, recreation programming, partnerships, economics, and stewardship. Community building and five others are of medium relative centrality, and the seven remaining goals are of low relative centrality.

Figure 5.

Secondary goals’ centrality score and relative centrality contextualized interpretation of high (blue), medium (green), or low (yellow). Centrality is the proportion of existing out-of-potential ties between each goal and the others. The overall network centralization is 0.105.

Interpreting this regarding “assistance”, partnerships are of relatively high centrality and connected to many goals mentioned across the plans, while community building is of medium centrality and connected to somewhat fewer goals. Together, this implies that both partnerships and community building are relatively well connected across the dataset and are of greater relevance than many other goals. This indicates that these two goals are important connections woven across strategic plans. Examination of the two “assistance” topics highlighted differences in how they are embedded into plans and corroborated previous findings on how they are discussed.

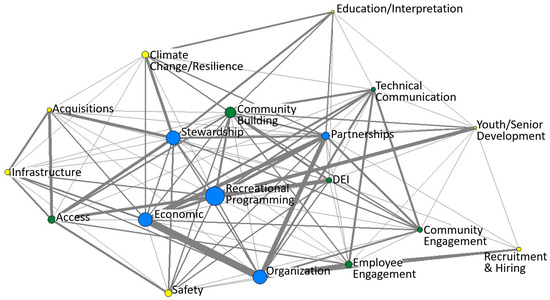

3.4. Results Summary

The three areas of results (topics, hierarchy, and relationships) intersect in Figure 6, depicting the number of primary instances and secondary relationships and the secondary goal centrality. Here, a goal’s centrality value is inherent in its distance from the network’s center and its relative centrality is depicted by shading (see Figure 5). The closer a goal is to the center of the network, the more central it is. The farther from the center the goal is, the more peripheral it is. Each goal is also sized, with a circle size increasing with more primary occurrences. The gray lines creating the “network” illustrate the connections among secondary goals. Goals connected by increasingly thicker lines are those that were more commonly phrased as supporting each other in hierarchical relationships.

Figure 6.

Summary of goals network data. Goal size represents the number of primary occurrences (range: 1 to 14) and color represents the relative centrality of secondary occurrences (low = yellow; medium = green; high = blue). Connection widths between goals correspond to the number of secondary goal co-occurrence instances (0 [no line] to 7 [thickest line]). DEI abbreviation = Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.

A few summary trends are apparent. First, recreation programming is toward the center of the network, large, and blue (high relative centrality). These all indicate that it is an important goal across connection metrics and hierarchical placements. The goals of economics and organization are smaller, indicating fewer primary goal occurrences. However, they are both blue (high relative centrality), driven by a diversity of connections and the thick connection between them. The latter indicates many co-occurring, supportive goal mentions—economics supporting organization goals or organization supporting economics goals. Second, six of the 18 goals have few occurrences as primary or secondary goals and are less connected (i.e., on the network periphery): safety, infrastructure, acquisitions, climate resilience, education and interpretation, youth and senior development, and recruitment and hiring practices. This indicates that although these goals are pronounced enough to be named goals across this investigation, their inclusion, position, and cross-referencing in any one plan are likely highly contextualized. The pronounced areas of co-occurrence or support (thicker lines) with these goals should not be discounted though, such as recreation programming with youth and senior development or stewardship with both climate resilience and acquisitions. The remainder of the goals—those in the mid-network positions (secondary occurrences), various sizes (primary occurrences), and blue or green color (high to medium relative centralities) are also goals that are important across the strategic plans, but their specific positionality and integration are also likely determined by the context and by the suite of goals represented in the plan.

Specifically for the two “assistance” goals, their difference emerges in this synthesis. Though community building has a lower relative centrality (green) than partnerships (blue), both are toward the center of the network, indicating that they are important connective goals. The specific inquiries elaborate on how this centrality differs. For community building, it is driven by many mentions as a primary goal (larger circle) and a diversity of supporting, secondary goals (multiple, thinner lines radiating to other goals). In contrast, partnerships’ centrality is driven by slightly fewer primary occurrences (smaller circle), but more secondary occurrences of support provided and received (more lines radiating to other goals), especially in relation to economic and organization goals (thicker lines). Taken together, this illustrates how both ”assistance” goals are critical connective goals across the dataset but in different functions.

4. Discussion

We investigated goals in park strategic plans, sourced from comparable urban complexity, to assist Rock Creek Park in framing their own strategic plan, with emphasis on how partnerships are discussed. Reviewing the plans, community building emerged as worthy of separate delineation from partnerships, though related within the “assistance” topic. This differentiation appears to resonate with and extend the findings of the National Park Service Urban Agenda efforts specifically in the D.C. area [39]. Our discussion is driven by that delineation and the contributions of both “assistance” goals in strategic plans [18,19]. Though we discuss the benefits of these considerations to Rock Creek Park, we also extend to discuss the meanings of this work for urban park systems more broadly, including internationally. As goal topics and hierarchies are common across planning efforts, and none in our dataset appear to be particularly U.S.-exclusive, the points below are of potential utility to urban park planners and related practitioners and scholars worldwide.

First, Rock Creek Park has a substantial start with their five initial goals (safety, access, stewardship, community engagement, and employee engagement), which are well represented throughout our dataset. Considering the park’s existing topics and its interest in partnerships and community building, we suggest that there are areas for integration. Notably, integrations among the five existing goals plus partnerships and community building (Figure 4) appear less common within community and employee engagement as primary goals, and for stewardship and community building as secondary goals. This could potentially mean that considering how other goals support community and employee engagement primary goals and how stewardship and community building support other primary goals could be two specific areas of concerted attention and under-referenced contribution.

These touch points may be useful to consider as Rock Creek and other urban parks frame their own contextualized strategic plans and emphasize how they contribute to a vibrant and inclusive cityscape [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,20,21,22,41]. Checking for cross-references among and within all intended goals may help facilitate an efficient, cohesive plan and potentially highlight novel goal contributions (e.g., what employee engagement looks like as a main goal, what community building looks like as a supportive goal). More broadly, urban parks could consider a matrix approach to setting main and supportive goals in plans, as this could illuminate areas of differential reciprocity and assist in strategically and mindfully acting on disparities if warranted. This would also be a means of emphasizing multiple points of relevance with local populations [13,22,23,41] and, therefore, attend to many priorities simultaneously in planning [13].

Second, detailing the goals present across the dataset provides inspiration and areas for consideration for Rock Creek and other urban parks looking at what others have prioritized. These 18 goals represent a mix of inward and outward-facing audiences. Because strategic plans function internally and externally, it is important to examine which audiences are included and how they may inclusively support goals focused within and beyond park borders [13,22,23,41]. The topic of “assistance” exemplifies how inward and outward-facing goals may be paired for complementary yet distinctive efforts.

Third, five of the 18 goals functioned as more fundamental and core across plans. These are recreation programming, community building, partnerships, stewardship, and organization. These may act as inspiration to urban parks about what is common to address in urban settings [13,21]. These goals emerged as relevant regardless of urban location, as park plans nationwide were included, illustrating their applicability to a diversity of strategic needs. Rock Creek and others may want to critically examine these goals and potentially elevate them to greater priority and visibility. Relatedly, the other 13 goals seemed more context-specific. Even if these are not priority goals for other urban parks, they could still serve as supportive goals as appropriate (e.g., applying them to specific situations and timings in a park’s strategic plan).

Fourth, secondary goals are crucial. Our analyses indicate how they are intimately interconnected to core primary goals and serve as the “glue” linking primary goals together in a cohesive, integrated plan. However, some secondary goals are still more integrative than others.

Community building illustrates this reciprocity imbalance well. It is prominent on the primary level but scarce on the secondary level. Community building as a primary goal is an important emphasis and potentially an ultimate objective for urban parks [41]. However, it is notably siloed as a primary goal and its lack of integration on the secondary level is somewhat troubling. While an important overarching pursuit, community building could also be a connective tissue across goals. This corroborates what the National Park Service Urban Fellow in D.C. found in their detailed interactions, that a presence by the park agency in the community, at events and initiatives that matter to the community but may have more tangential connections to a specific national park, are crucial for connecting the park with the urban setting in a more reciprocal fashion [39]. Community building is somewhat newer within park policy, though we recognize it has long been important in park actions [13,41]. Given this, it is unsurprising that it is siloed in the dataset. This echoes themes found in Avni’s work [40] in Anacostia Park in D.C., in that community integration and power imbalances in planning are acknowledged and discussed as in progress rather than fulfilled. This may change with time. For example, just as diversity, equity, and inclusion were once new and siloed, it is now viewed as a priority emphasized alone and in concert with every other priority in park functions. Urban parks could do the same with community building, considering it an important contribution to supporting multiple park priorities and everyday functions and not strictly as a separate category [13,20,21,22,41]. In this way, goals including community building might be seen as contributing park strengths toward community efforts as a part of all efforts rather than as a separate ask—another consideration but not necessarily additional work. This framing could consider community building both as an aim and as a tool toward other aims. Because stewardship, climate resilience, organization, and recreation programming all displayed a similar, though less pronounced, pattern as community building, these goals specifically may be useful in creatively coordinating with community building across main goals.

Fifth, Rock Creek Park and others may want to thoughtfully consider “assistance” across hierarchies. Although park-focused partnerships are undoubtedly important, they may not suffice alone. Context-focused community building is also vital and will be of increasing importance as urban parks continue to work on greater relevance with their local surroundings and populations [13,20,35,36]. Indeed, while we saw partnerships and community building in the top listings of primary goals, of primary goals receiving support, and of primary goals well connected in the goals network, it was consistently community building that fell short on secondary goals and other measures. Because partnerships appear to already be a consistent thought in crafting main and supportive goals, urban parks may find it useful to ask themselves about the appropriateness of also including community building wherever partnerships have a default “assistance” approach.

Methodologically, these connections should continue to be examined as updated strategic plans are created, a greater depth of urban areas’ park strategic plans are amassed, and new events and challenges emphasize different aspects of collaborative goals in urban park settings. Our work was limited by investigating a subset of urban areas with park planning efforts (the top 20 by population), and the analyzed plans came from different years of creation yet were the most recent found within our specified parameters. A more comprehensive examination may lead to further definition of goal topics and placements. Furthermore, pairing these secondary data analyses with qualitative inquiries with park planners could yield insight into the process for inclusion/exclusion and placement of goals, and the priorities and constraints dictating these final renderings. We note that park planning capacities differ and, therefore, longitudinal studies accounting for these park differences would be warranted, especially to examine any shifts in community-building within a park system and across urban areas over time.

5. Conclusions

This study on urban park planning goals is useful across similar contexts in the U.S. and abroad, especially when considering the framing of “assistance” goals. Park systems are often tasked with providing robust strategic plans that account for their internal work and that need collaborative assistance. Our work synthesizes areas of inspiration and practical application for parks and could act as a guide for framing discussions within their contexts. By examining components of collaboration and assistance more minutely, we found that parks are naming both inward-facing partnership goals and outward-facing community building goals as critical topics in plans. This breakdown of a topic as diffuse as “assistance” is useful to promote discrete and robustly aligned objectives, goals, and actions with these two complementary portions of assistance. Though each park system will need to define what rises to be a primary goal versus a secondary, supportive goal, our examination of goal hierarchy indicates that community building is more prevalent as a primary than a secondary goal, though it could function as an important support across other primary goals. Thus, a major takeaway from this effort is that urban park planning might benefit from more community building efforts across priorities, not just as a stand-alone priority. Considering “community building” as a touchpoint in the naming of supportive goals and actions across all goals would be a rich area for integrated goal development and weaving urban parks more into the identity of their surrounding cityscape, metro area, or region [13].

This dual approach to “assistance” as partnerships and community building is especially needed in metropolitan areas, as examining the complex interchange between parks and their surrounding communities is essential to thriving cityscapes. Compared to partnerships, community building secondary goals may seem lofty or more difficult to put into practice. However, strategic plans allow for such leaps and indicate desired directions for progress, if not attainment (though such attainment should be examined, e.g., [38]). They provide opportunities to examine and promote reciprocity between parks and communities and how plan content can co-support park and community aims and visions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/urbansci9030064/s1, ROCRplans_UrbanScience_Dataset_250106.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.E.P. and E.A.S.; methodology, E.E.P. and E.A.S.; validation, E.E.P., E.A.S. and A.M.; formal analysis, E.E.P. and E.A.S.; investigation, E.E.P.; resources, E.E.P.; data curation, E.A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.E.P. and E.A.S.; writing—review and editing, E.E.P., E.A.S. and A.M.; visualization, E.E.P. and E.A.S.; supervision, E.E.P.; project administration, E.E.P.; funding acquisition, E.E.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The investigation presented here extends from a study within a larger program of research funded by the U.S. National Park Service through Chesapeake Watershed Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (CESU) agreements P19AC01077 and P19AC00946 with Old Dominion University.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or Supplementary Material. The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

We thank Christopher Zajchowski and Jessica Fefer for their input on the initial drafts of this work and for securing and leading the larger program of research with the Region 1 Lands and Planning directorate of the National Park Service.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, M.; Samborska, V. Urbanization: Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Chiesura, A. The role of urban parks for the sustainable city. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 68, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.D.; Vanos, J.; Kenny, N.; Lenzholzer, S. Designing urban parks that ameliorate the effects of climate change. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 138, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Chen, L.; Sun, R. Climatic effects on landscape multifunctionality in urban parks: A view for integrating ecological supply and human benefits. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 19, 014032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes Hursh, S.; Perry, E.E.; Drake, D. A common chord: To what extent can small urban green space support people and songbirds? J. Urban Ecol. 2024, 10, juae009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beninde, J.; Veith, M.; Hochkirch, A. Biodiversity in cities needs space: A meta-analysis of factors determining intra-urban biodiversity variation. Ecol. Lett. 2015, 18, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connop, S.; Vandergert, P.; Eisenberg, B.; Collier, M.J.; Nash, C.; Clough, J.; Newport, D. Renaturing cities using a regionally-focused biodiversity-led multifunctional benefits approach to urban green infrastructure. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 62, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranz, G.; Boland, M. Defining the sustainable park: A fifth model for urban parks. Landsc. J. 2004, 23, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, C.D.; Giusti, M.; Fischer, J.; Abson, D.J.; Klaniecki, K.; Dorninger, C.; Laudan, J.; Barthel, S.; Abernethy, P.; Martin-Lopez, B.; et al. Human-nature connection: A multidisciplinary review. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26–27, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepczyk, C.A.; Aronson, J.F.J.; Evans, K.L.; Goddard, M.A.; Lerman, S.B.; MacIvor, J.S. Biodiversity in the city: Fundamental questions for understanding the ecology of urban green spaces for biodiversity conservation. BioScience 2017, 67, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Park Service Stewardship Institute. Urban Agenda: Call to Action Initiative; National Park Service Stewardship Institute: Woodstock, VT, USA, 2015. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/subjects/urban/index.htm (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Morath, S.J. The National Park Service in urban America. Nat. Resour. J. 2016, 56, 1–21. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24889108 (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Perry, E.E.; Jewiss, J.; Manning, R.E.; Ginger, C. How to define urban park relevance? Examining and integrating US National Park Service and partner views on the goal of “relevance to all Americans”. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, J.; Wolch, J.; Zhang, J. Planning for environmental justice in an urban national park. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2009, 52, 365–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.A.; Hunter, G.; Williamson, S.; Dubowitz, T. Are food deserts also play deserts? J. Urban Health 2016, 93, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahmann, N.; Wolch, J.; Joassart-Marcelli, P.; Reynolds, K.; Jerrett, M. The active city? Disparities in provision of urban public recreation resources. Health Place 2010, 16, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Manning, R.; Perry, E.; Valliere, W. Public awareness of and visitation to national parks by racial/ethnic minorities. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2018, 31, 908–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craigie, I.D.; Pressey, R.L. Fine-grained data and models of protected-area management costs reveal cryptic effects of budget shortfalls. Biol. Conserv. 2022, 272, 109589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slocum, S.L. Operationalising both sustainability and neo-liberalism in protected areas: Implications from the USA’s National Park Service’s evolving experiences and challenges. In Protected Areas, Sustainable Tourism, and Neo-Liberal Governance Policies, 1st ed.; Job, H., Bcken, S., Lane, B., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, E.E.; Krymkowski, D.H. Structures indicating a shift toward a culture of collaboration in National Park Service urban networks. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2024, 38, 252–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, E.E.; Krymkowski, D.H.; Manning, R.E. Brokers of relevance in National Park Service urban collaborative networks. Ecol. Soc. 2019, 24, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, E.E.; Kiewra, L.A.; Brooks, M.E.; Xiao, X.; Manning, R.E. “Parknerships” for sustainable relevance: Perspectives from the San Francisco Bay Area. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Matarrita-Cascante, D.; Xu, Y.; Schuett, M. Examining the conflicting relationship between U.S. national parks and host communities: Understanding a community’s diverging perspectives. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dell, P. Redefining the National Park Service role in urban areas: Bringing the parks to the people. J. Leis. Res. 2016, 48, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambic, E.B.; Herrin, D.; Crawford-Lackey, K. Fulfilling the promise: Improving collaboration between cultural resources and interpretation and education in the U.S. National Park Service. In Connections Across People, Place, and Time, Proceedings of the 2017 George Wright Society Conference on Parks, Protected Areas, and Cultural Sites, Norfolk, VA, USA, 2–7 April 2017; Weber, S., Ed.; George Wright Society: Hancock, MI, USA, 2017; pp. 82–87. Available online: http://www.georgewright.org/gws2017_proceedings.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- National Park Service Stewardship Institute. Collaboration and Engagement. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1412/collaboration-and-engagement.htm (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Partnership and Community Collaboration Academy. The Competencies. Available online: https://www.partnership-academy.net/about-us/the-22-competencies/ (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Knapp, C.N.; Chapin, F.S., III; Kofinas, G.P.; Fresco, N.; Carothers, C.; Craver, A. Parks, people, and change: The importance of multistakeholder engagement in adaptation planning for conserved areas. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiappa, E.A.; Perry, E.E.; Huff, E.; Lopez, M.C. Local climate action planning toward larger impact: Enhancing a park system’s contributions by examining regional efforts. Sustain. Clim. Change 2023, 16, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, G.S.M.; Rhodes, J.R. Protected areas and local communities: An inevitable partnership toward successful conservation strategies? Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.Y.; Samsudin, R. Effects of spatial scale on assessment of spatial equity of urban park provision. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 158, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibes, D.C. Sustainable urban park systems. Cities Environ. 2014, 7, 8. Available online: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/cate/vol7/iss2/8 (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Loures, L.; Santos, R.; Panagopoulos, T. Urban parks and sustainable city planning—The case of Portimão, Portugal. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2007, 10, 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, E.E.; Thomsen, J.M.; D’Antonio, A.L.; Morse, W.; Reigner, N.; Leung, Y.-F.; Wimpey, J.; Taff, B.D. Toward an integrated model of topical, spatial, and temporal scales of research inquiry in park visitor use management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menconi, M.E.; Tasso, S.; Santinelli, M.; Grohmann, D. A card game to renew urban parks: Face-to-face and online approach for the inclusive involvement of local community. Eval. Program Plan. 2020, 79, 101741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuib, K.; Hashim, H.; Akmaniza, N.; Nasir, M. Community participation strategies in planning for urban parks. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 168, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raap, S.; Knibbe, M.; Horstman, K. Clean spaces, community building, and urban stage: The coproduction of health and parks in low-income neighborhoods. J. Urban Health 2022, 99, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebhardt, A.; Eagles, P.F.J. Factors leading to the implementation of strategic plans for parks and recreation. Manag. Leis. 2014, 19, 321–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Park Service. Urban Parks and Programs: Washington DC. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/subjects/urban/washington-dc.htm (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Avni, N. Bridging equity? Washington, D.C.’s new elevated park as a test case for just planning. Urban Geogr. 2018, 40, 488–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, E.E.; Ginger, C.A.; Jewiss, J.; Krymkowski, D.; Manning, R.E. National Park Service internal structures toward agency resilience: A mixed-methods, multi-site, mesoscale investigation. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2024, 42, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Park Service. The Parks of the National Park System, Washington, DC: Reservation List. Land Resources Program Center, National Capital Region, National Park Service, US Department of the Interior 2011. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/features/foia/Reservation-List-2011.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- National Park Service IRMA. National Park Service Visitor Use Statistics: Rock Creek Park (ROCR). Available online: https://irma.nps.gov/Stats/Reports/Park/ROCR (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Bryson, J.M. Strategic Planning for Public and Nonprofit Organizations: A Guide to Strengthening and Sustaining Organizational Achievement, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population in the United States and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2021. Available online: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-total-metro-and-micro-statistical-areas.html#par_textimage_1139876276 (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Mesa Parks, Recreation, and Community Facilities. Strategic Plan 2018–2022; Mesa Parks, Recreation, and Community Facilities: Mesa, AZ, USA, 2017.

- Long Beach Parks, Recreation, and Marine Department. The Strategic Plan for 2022–2032; Long Beach Parks, Recreation, and Marine Department: Long Beach, CA, USA, 2021.

- Los Angeles County Department of Parks and Recreation. Strategic Plan: Shaping Tomorrow Today for Healthier, Happier Communities. Available online: https://parks.lacounty.gov/strategicplan/ (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- San Francisco Recreation and Park Department. Strategic Plan 2020–2024 Update; San Francisco Recreation and Park Department: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2024.

- San Diego County Parks and Recreation. Strategic Plan 2016–2021; San Diego County Parks and Recreation: San Diego, CA, USA, 2016.

- Denver Parks and Recreation. Strategic Acquisition Plan; Denver Parks and Recreation: Denver, CO, USA, 2021.

- City of Tampa Parks and Recreation. Strategic Plan; City of Tampa Parks and Recreation: Tampa, FL, USA, 2021.

- City of Fort Lauderdale Parks and Recreation Department. Parks and Recreation System Master Plan (Chapter 4 and 5); City of Fort Lauderdale Parks and Recreation Department: Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 2016.

- National Park Service. Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site 5-Year Strategic Plan (2006–2011). Available online: https://home.nps.gov/malu/learn/management/lawsandpolicies.htm (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Chicago Park District. Strategic Plan; Chicago Park District: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016.

- Naperville Park District. 2018–2020 Naperville Park District Strategic Plan. Available online: https://napervilleparks.org/about/plansandsurveys/strategicplan (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Boston Harbor Islands Partnership. Boston Harbor Islands National Park Area in 2016: Strategic Plan; National Park Service: Boston, MA, USA, 2009.

- Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board. Comprehensive Plan 2007–2020; Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2007; Available online: https://www.minneapolisparks.org/_asset/9h52lq/comprehensive_plan.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Dallas Park and Recreation Department. Comprehensive Plan. Dallas, Texas. 2015. Available online: https://www.dallasparks.org/DocumentCenter/View/5266/Park-and-Recreation-Comprehensive-Plan-Appendices-Final-20160318 (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Seattle Parks and Recreation. Healthy People, Healthy Environment, Strong Communities: A Strategic Plan for Seattle Parks and Recreation 2020–2032. Seattle, Washington; 2020. Available online: https://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/ParksAndRecreation/PoliciesPlanning/SPR_Strategic_Plan.03.27.2020.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Metroparks Tacoma. Metropolitan Park District of Tacoma: Strategic Master Plan. Tacoma, Washington. 2018. Available online: https://www.metroparkstacoma.org/about/agency-plans-partnerships/strategic-plan/ (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- DC Department of Parks and Recreation. 2020 DPR Strategic Plan. City of Washington, D.C.; 2020. Available online: https://dpr.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/dpr/page_content/attachments/Strategic%20Plan%2C%20Ready2Play%20%281%29.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- National Park Service. George Washington Memorial Parkway Priorities and Actions Handbook 2022–2025. Washington, D.C.; 2019. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/gwmp/learn/management/upload/NPSMagazine_Web-tagged-V2-Final-opt.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- The City of Alexandria Recreation, Parks, and Cultural Activities. Strategic Master Plan for Open Space, Parks, and Recreation; City of Alexandria Recreation, Parks, and Cultural Activities: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2002.

- Arlington County Department of Parks and Recreation. Strategic Plan FY 2021–2025. Arlington, Virgina. 2020. Available online: https://www.arlingtonva.us/files/sharedassets/public/parks-amp-recreation/documents/strategic-plan-summary-dpr-fy21-25.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- New York City Parks. A Plan for Sustainable Practices Within NYC Parks. New York City, New York; 2011. Available online: https://www.nycgovparks.org/sub_about/sustainable_parks/Sustainable_Parks_Plan.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Stemler, S. An overview of content analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2019, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldana, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Giuffre, K. Communities and Networks: Using Social Network Analysis to Rethink Urban and Community Studies; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Knoke, D.; Yang, S. Social Network Analysis, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).