Empowering Urban Tourism Resilience Through Online Heritage Visibility: Bucharest Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Context Analysis

2.1. Urban Tourism Resilience Connected to Cultural Heritage and the Particularities of CEE Destinations

2.2. Online Cultural Heritage Visibility and Urban Tourism Resilience in a Post-COVID Context

2.3. Main Aspects of the Case Study

3. Materials and Methods

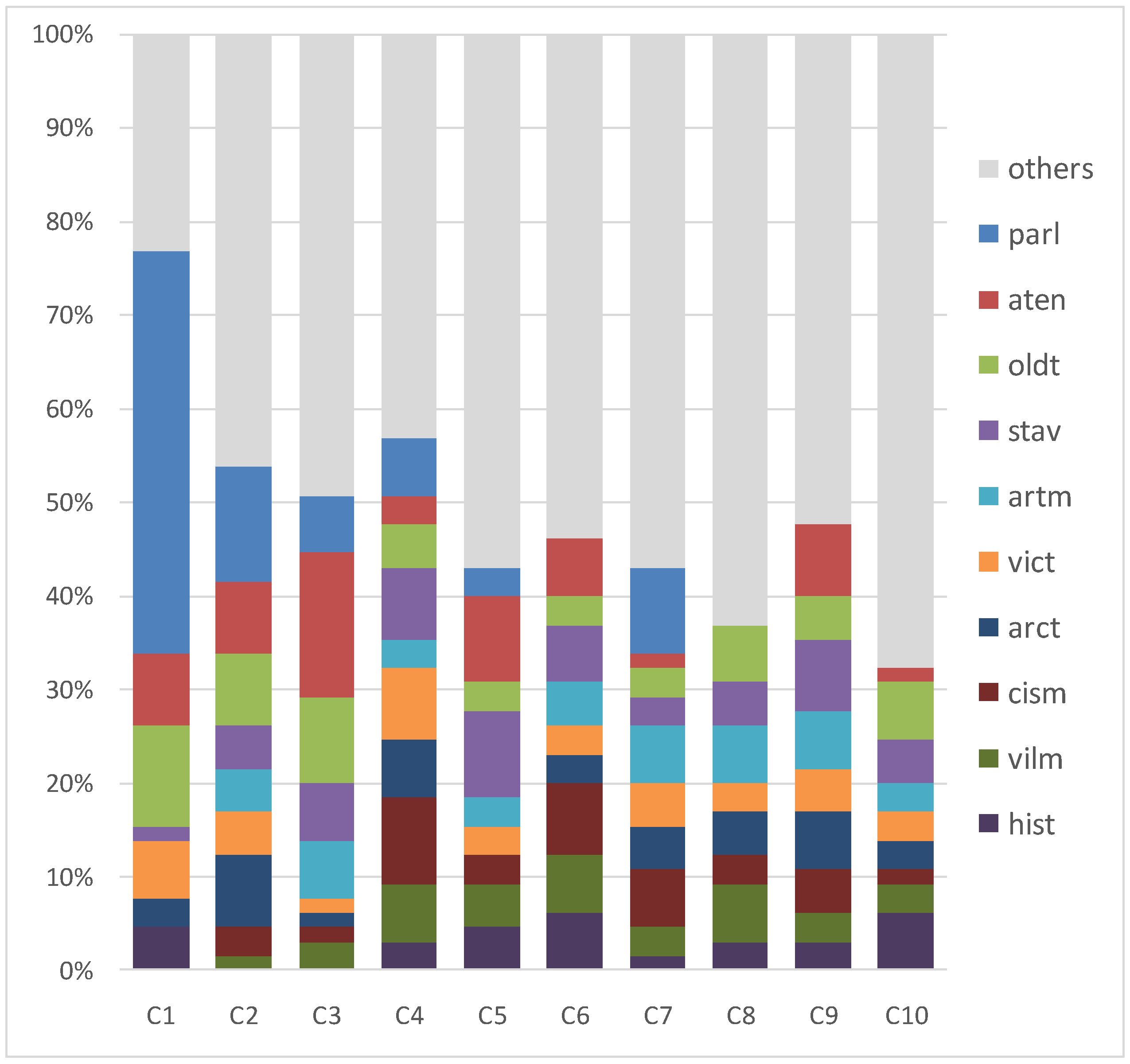

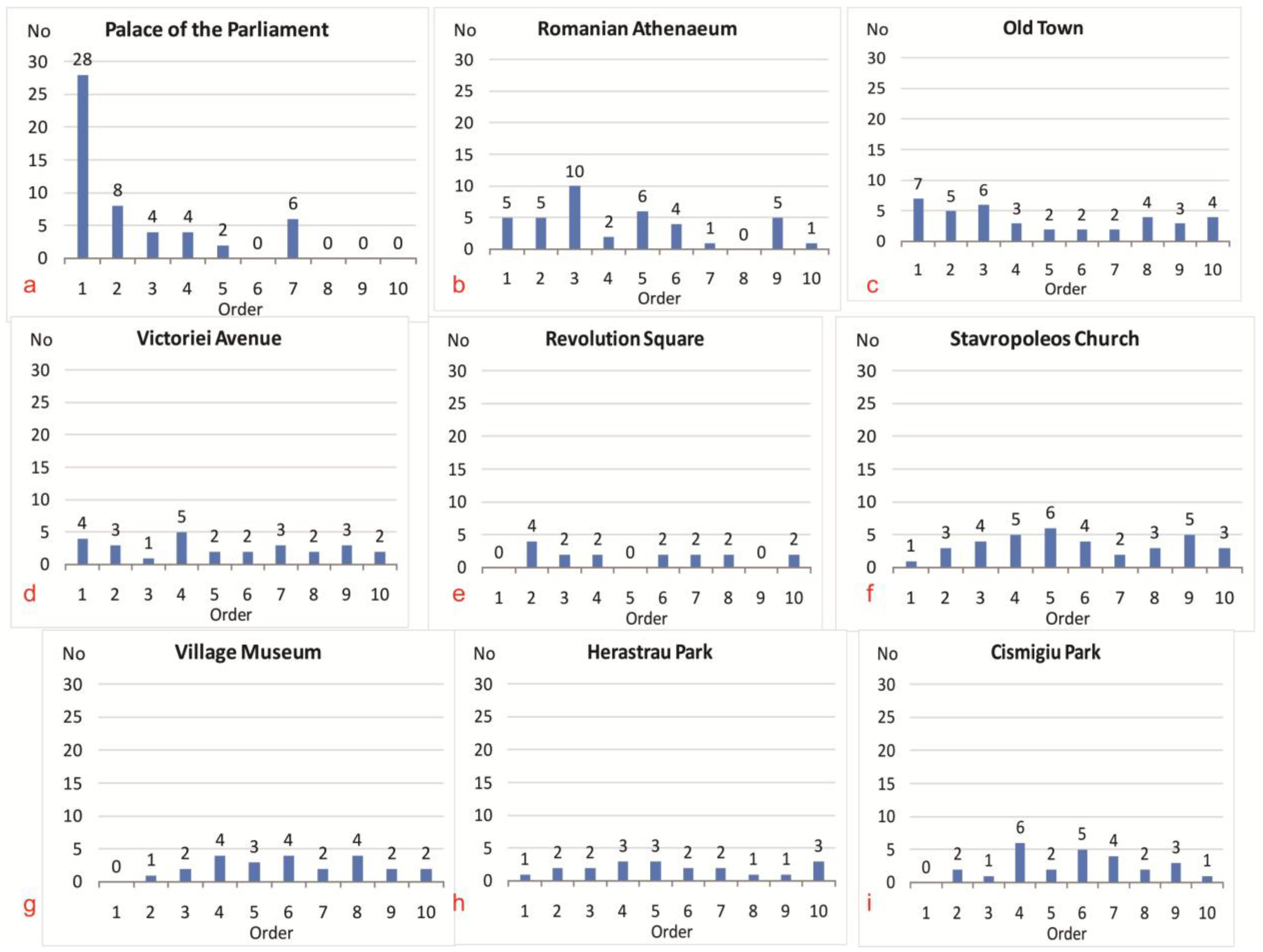

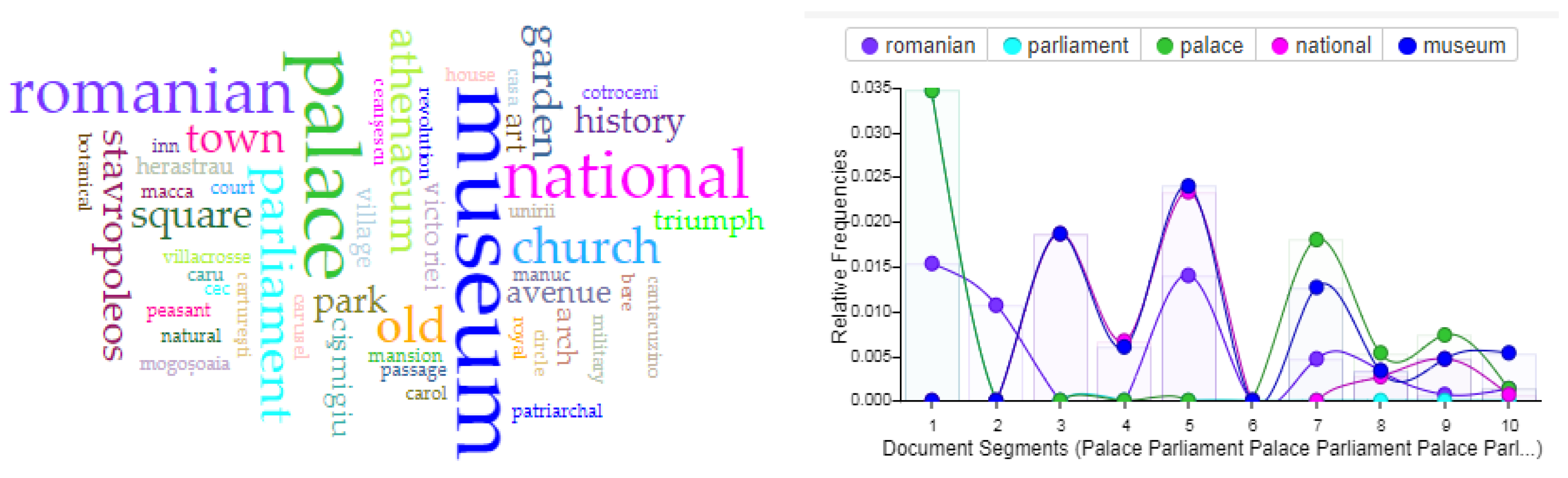

4. Main Results

- -

- Attractions and monuments located in the center of Bucharest (e.g., Palace of Parliament, Unirii Square, Old Town, Stavropoleos Church, Victoriei Avenue, Romanian Athenaeum, Revolution Square, Romanian National Museum of Art, and Cişmigiu Park). Most of the advertised tourist attractions are concentrated here.

- -

- Those located on the express bus line to Henry Coandă (Otopeni) Airport in the northern part of the city. The attractions in this area are just as significant but less frequented than those in the center. These include Bucharest’s largest park, Herăstrău, which is very popular and visited all year round by both foreign tourists and locals; the Village Museum, which is located near Herăstrău Park and recognized and visited mainly by people/tourists interested in Romanian traditions; and the Ceauşescu Mansion/Palatul Primaverii (Spring Palace), which attracts a large number of tourists, especially people interested in recent history and the dictatorship period. These are usually frequented by tourists passing through the area on their way to the airport or specifically visiting different monuments or Bucharest landmarks.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- -

- Extend the visibility and promotion of cultural heritage through the design and development of tourism products proposing flagship iconic objectives and supplementary associated attractions based on either the theme and/or the location of main tourism attractors (e.g., visits to the National Museum of Contemporary Art hosted by the building of the Palace of Parliament; visits to the Museum of Communism located in the Old Town, associated with visits to the Palace of Parliament or Ceauşescu’s residence; visits to Stavropoleos Church, associated with visits to Sf. Anton Church in the Old Town, located near the ruins of the Old Royal Court of Bucharest or other old churches in the city center).

- -

- Extend the visibility and promotion of urban cultural heritage all over Bucharest through the design and development of thematic routes. Starting from the qualitative results in our study and types of heritage that could raise tourist interest, one could see a possible tour of Bucharest’s palaces (e.g., Suţu Palace, part of Bucharest’s Municipality Museum; Cantacuzino Palace, near the National Museum “George Enescu”), churches (in the Old Town and the monasteries around Bucharest), gardens, and famous squares (e.g., Revolution Square, University Square), or a red tourism tour (to be designed and adapted for different target groups).

- -

- Digitalization of cultural heritage for both its valorization and better promotion, starting with the implementation of QR codes as a means of information and continuing to the design of adapted specialized applications for different types of users, which may determine immersive cultural tourism experiences.

- -

- The design of creative cultural products and adapted events that should value both iconic landmarks and less well-known monuments that could be visited in Bucharest, either on an open access basis or on different occasions.

- -

- The association of cultural products and attractions with corporate events and business tourism (e.g., conferences or fairs) that would increase both the visibility and the financial sustainability of cultural heritage preservation and valorization for visiting purposes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheer, J.M. Human flourishing, tourism transformation and COVID-19: A conceptual touchstone. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochado, A.; Rodrigues, P.; Sousa, A.; Borges, A.P.; Veloso, M.; Gómez-Suárez, M. Resilience and Sustainable Urban Tourism: Understanding Local Communities’ Perceptions after a Crisis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surugiu, C.; Tudorache, D.M.; Aştefănoaiei, R.M.; Surugiu, M.R. Bucharest cultural heritage through the eyes of social media users. Anatolia 2021, 33, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lequeux-Dincă, A.I.; Preda, M.; Taloş, A.M. Empirical evidences on foreign tourist demand perception of Bucharest. Almatourism-J. Tour. Cult. Territ. Dev. 2018, 9, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lequeux-Dincă, A.-I.; Sava, A.-A.; Teodorescu, C.; Gheorghilaş, A.; Clius, M. Sport Event Tourism in Bucharest. UEFA EURO 2020 Case Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIS—National Institute of Statistics—Romania. Turismul în Luna Decembrie 2023—Newsletter. 2024. Available online: https://insse.ro/cms/sites/default/files/com_presa/com_pdf/turism12r23.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Hall, D.R. Tourism development and sustainability issues in Central and South-Eastern Europe. Tour. Manag. 1998, 19, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surugiu, C.; Surugiu, M.-R.; Grădinaru, C. Targeting Creativity Through Sentiment Analysis: A Survey on Bucharest City Tourism. Sage Open 2023, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.Q.; Qu, H. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confetto, M.G.; Conte, F.; Palazzo, M.; Siano, A. Digital destination branding: A framework to define and assess European DMOs practices. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2023, 30, 100804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, S.; Raman, R.K. Travel Influencers, Reference Module in Social Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, P.-S.; Tan, G.W.-H.; Aw, E.C.-X.; Ooi, K.-B. Shared moments, lasting impressions: Experience co-creation via travel livestreaming. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 58, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.M.; EkStyven, M.; Nataraajan, R. Social comparison orientation and frequency: A study on international travel bloggers. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harfst, J.; Syrbe, R.-U.; Kern, C.; Wirth, P.; Sandriester, J.; Pstrocka-Rak, M.; Dolzblasz, S. Cultural Tourism and Governance in Peripheral Regions. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D.; Creţan, R.; Voiculescu, S.; Jucu, I.S. Introduction: Changing Tourism in the Cities of Post-communist Central and Eastern Europe. J. Balk. Near East. Stud. 2024, 22, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D. Destination branding, niche marketing and national image projection in Central and Eastern Europe. J. Vacat. Mark. 1999, 5, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, H.; Allen, D. Cultural tourism in Central and Eastern Europe: The views of ‘induced image formation agents’. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horáková, H. Post-Communist Transformation of Tourism in Czech Rural Areas: New Dilemmas. Anthropol. Noteb. 2010, 16, 59–77. [Google Scholar]

- Vaishar, A.; Šťastná, M.; Zapletalová, J. From industry to cultural tourism: Structural transformation of the second-order city. Case Brno. Cities 2025, 158, 105685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen-Verbeke, M. Tourismification of Historical Cities. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 25, 739–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk-Anioł, J. Rethinking tourism-driven urban transformation and social tourism impact: A scenario from a CEE city. Cities 2023, 134, 104178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karner, M.J.; Husseini de Araújo, S.; Escher, A.J.; Soares, S.B.V.; Ribeiro, Z.L.; Pöschl, S.N.; Ramos, J.O.; Rocha e Silva, G.R.; Schneider, K. “Culture-touristification” of colonial towns in the interior of Brazil. Erdkunde 2024, 78, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neducin, D.; Krklješ, M.; Gajić, Z. Post-socialist context of culture-led urban regeneration—Case study of a street in Novi Sad. Serbia. Cities 2019, 85, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, N.; Pop, A.-M.; Marian-Potra, A.-C. Culture-led urban regeneration in post-socialist cities: From decadent spaces towards creative initiatives. Cities 2025, 158, 105707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navratil, J.; Krejci, T.; Martinat, S.; Pasqualetti, M.J.; Klusacek, P.; Frantal, B.; Tochackova, K. Brownfields do not “only live twice”: The possibilities for heritage preservation and the enlargement of leisure time activities in Brno, the Czech Republic. Cities 2018, 74, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilovan, O.-R. The Development Discourse during Socialist Romania in Visual Representations of the Urban Area. J. Urban Hist. 2022, 48, 861–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D. Gazing on communism: Heritage tourism and post-communist identities in Germany, Hungary and Romania. Tour. Geogr. 2000, 2, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manahasa, E.; Manahasa, O. Nostalgia for the lost built environment of a socialist city: An empirical study in post-socialist Tirana. Habitat Int. 2022, 119, 102493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debruyne, N.; Nazarska, G. Contentious heritage spaces in post-communist Bulgaria: Contesting two monuments in Sofia. J. Hist. Geogr. 2024, 83, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokołowicz, M.E.; Przygodzki, Z. The value of ambiguous architecture in cities. The concept of a valuation method of 20th century post-socialist train stations. Cities 2020, 104, 102786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balockaite, R. Coping with the unwanted past in planned socialist towns: Visaginas, Tychy, and NowaHuta. Slovo 2013, 24, 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Naumov, N.; Weidenfeld, A. From socialist icons to post-socialist attractions: Iconicity of socialist heritage in Central and Eastern Europe. Geogr. Pol. 2019, 92, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, I.; Orzan, G.; Dobrescu, A.; Radu, A.C. Online Marketing Communication Using Websites. A Case Study of Website Utility in Accessing European Funds in the Tourism Field Regarding Northeastern Romania. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 23, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Lankao, P.; Gnatz, D.M.; Wilhelmi, O.; Hayden, M. Urban Sustainability and Resilience: From Theory to Practice. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metaxas, T.; Psarropoulou, S. Sustainable Development and Resilience: A Combined Analysis of the Cities of Rotterdam and Thessaloniki. Urban Sci. 2021, 5, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepej, D.; Marot, N. Considering urban tourism in strategic spatial planning. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2024, 5, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandić, A.; Petrić, L.; Pivčević, S. Harmonizing sustainability and resilience in post-crisis cultural tourism: Stakeholder insights from the Split metropolitan area living lab. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2025, 55, 101331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulescu, R.; Meleca, A. Tourism Resilience and the EU Regional Economy. In Proceedings of the 18th International RAIS Conference on Social Sciences and Humanities, Princeton, NJ, USA, 17–18 August 2020; pp. 268–276. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Z.-Y.; Huang, A.-M.; Huang, Z.-Y. Virtual tourism attributes in cultural heritage: Benefits and values. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2024, 53, 101275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Lang, C.; Corbet, S.; Wang, J. The impact of COVID-19 on the volatility connectedness of the Chinese tourism sector. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2024, 68, 102192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianou-Lambert, T. Tourists with cameras: Reproducing or Producing? Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1817–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. Listen with Your Eyes; Towards a Filmic Geography. Geogr. Compass 2013, 7, 714–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spettu, F.; Achille, C.; Fassi, F. State-of-the-ArtWeb Platforms for the Management and Sharing of Data: Applications, Uses, and Potentialities. Heritage 2024, 7, 6008–6035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Mou, N.; Zhu, S.; Yang, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y. How to perceive tourism destination image? A visual content analysis based on inbound tourists’ photos. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2024, 33, 100923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerić, D.; Więckowski, M.; Timothy, D.J. Visual representation of tourism landscapes: A comparative analysis of DMOs in a cross-border destination. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2024, 34, 100932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baka, V. The becoming of user-generated reviews: Looking at the past to understand the future of managing reputation in the travel sector. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Yang, Y. Determinants of consumers’ choices in hotel online searches: A comparison of consideration and booking stages. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 86, 102370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Xu, D.; Chen, T. Travel vlogging practice and its impacts on tourist experiences. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 2518–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasithradevi, A.; Nathan, S.; Chanthini, B.; Subbulakshmi, T.; Prakash, P. MonuNet: A high performance deep learning network for Kolkata heritage image classification. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaika, M. Architecture and crisis: Re-inventing the icon, re-imag(in)ing London and re-branding the City. Trans. Inst. Br. 2010, 35, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, J.L.T.; Smith, R.A. Modelling Urban Tourism in Historic Southeast Asian Cities. Urban Sci. 2021, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćamilović, D. The Internet Presence of Belgrade Museums in the Service of Cultural Tourism. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Scientific Conference, Tourism in Function of Development of the Republic of Serbia: Tourism as a Generator of Employment (TISC 2019), Vrnjačka Banja, Serbia, 30 May–1 June 2019; pp. 500–517. [Google Scholar]

- Merciu, F.-C.; Petrişor, A.-I.; Merciu, G.-L. Economic Valuation of Cultural Heritage Using the Travel Cost Method: The Historical Centre of the Municipality of Bucharest as a Case Study. Heritage 2021, 4, 2356–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucharest Tourism Board. 16 December 2014. Available online: https://www.trendshrb.ro/evenimente/bucharest-tourism-board/ (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Ghira, A. Primăria Bucureștiului Sondează Piața Pentru a Realiza Strategia de Promovare a Turismului în Capitală. 13 April 2022. Available online: https://www.economica.net/strategie-promovare-turism-bucuresti_575649.html?uord=RQ-ZWvb-tTjdRm5hUUkxlrRYLsQvwpdH/r-aRBhVX1MhiGIo9FOqIE2LsdOtLHFImaIWYHh8/DyxKRcUqVE9Z2iqVntiobiCYfMvmcRFOb-8SEuJJPfshzXyRneuUXkxnuNRYvEy (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Bucharest City Hall & World Bank Group (February 2022) IUDS (Integrated Urban Development Plan). Available online: https://estibucuresti.pmb.ro/pdf/sidu/en/STRATEGY-DEVELOPMENT.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Ghira, A. Bucureştiul Are Un Nou Site Pentru Promovarea Turistică. Cum Arată Capitala în Mediul Online. 30 January 2016. Available online: https://www.economica.net/bucurestiul-are-un-nou-site-pentru-promovarea-turistica-cum-arata-capitala-in-online_113848.html (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Available online: https://www.seebucharest.ro/ (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Available online: https://www.b.ro/ (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Leelawat, N.; Jariyapongpaiboon, S.; Promjun, A.; Boonyarak, S.; Saengtabtim, K.; Laosunthara, A.; Yudha, A.K.; Tang, J. Twitter data sentiment analysis of tourism in Thailand during the COVID-19 pandemic using machine learning. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luong, T.-B.; Ching-Hua Ho, C.-H. The influence of food vloggers on social media users: A study from Vietnam. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Law, R.; Vu, H.Q.; Rong, J.; Zhao, X.R. Identifying emerging hotel preferences using Emerging Pattern Mining technique. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lin, J.; Feng, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, S.; Ren, Y.; Li, H. Construction of cultural heritage evaluation system and personalized cultural tourism path decision model: An international historical and cultural city. J. Urban Manag. 2023, 12, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrache, L.; Nae, M. Romanian Food on an International Plate: Exploring Communication, Recipes, and Virtual Affect in Culinary Blogs. Berichte Geogr. Landeskd. 2023, 96, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lequeux-Dincă, A.-I.; Preda, M.; Vijulie, I. Authentic Romanian Gastronomy—A Landmark of Bucharest’s City Center. Tour. Hosp. 2024, 5, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D. Rural Tourism Development in Southeastern Europe: Transition and the Search for Sustainability. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2004, 6, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, A.; Andreoli, M.; Rovai, M. Adaptive Reuse of a Historic Building by Introducing New Functions: A Scenario Evaluation Based on Participatory MCA Applied to a Former Carthusian Monastery in Tuscany, Italy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.K. Issues in Cultural Tourism Studies, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 114–142. [Google Scholar]

- Ianos, I.; Cocheci, R.-M.; Petrişor, A.-I. Exploring the Relationship between the Dynamics of the Urban–Rural Interface and Regional Development in a Post-Socialist Transition. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.-K.; Tan, S.-H. A creative place-making framework—Story-creation for a sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 3673–3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Site/Platform | Marketing and Tourism Platforms | Blogs | Booking and Ticketing Platforms | General Information Platforms | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35 | 16 | 9 | 5 | 65 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lequeux-Dincă, A.-I.; Gheorghilaş, A.; Tudor, E.-A. Empowering Urban Tourism Resilience Through Online Heritage Visibility: Bucharest Case Study. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9030063

Lequeux-Dincă A-I, Gheorghilaş A, Tudor E-A. Empowering Urban Tourism Resilience Through Online Heritage Visibility: Bucharest Case Study. Urban Science. 2025; 9(3):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9030063

Chicago/Turabian StyleLequeux-Dincă, Ana-Irina, Aurel Gheorghilaş, and Elena-Alina Tudor. 2025. "Empowering Urban Tourism Resilience Through Online Heritage Visibility: Bucharest Case Study" Urban Science 9, no. 3: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9030063

APA StyleLequeux-Dincă, A.-I., Gheorghilaş, A., & Tudor, E.-A. (2025). Empowering Urban Tourism Resilience Through Online Heritage Visibility: Bucharest Case Study. Urban Science, 9(3), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9030063