Exploring the Intersection of Environmental Justice and Urban Green Space Planning: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Current Trends and Existing Similar Studies

1.2. Research Gaps

1.3. Conceptualising EJ and Theoretical Underpinnings for UGS

1.4. Objectives and Research Questions

- RQ1: How does environmental racism manifest in UGS distribution and accessibility, especially in the Global South?

- RQ2: How can gentrification risks be mitigated, ensuring green space improvements do not displace marginalised communities?

- RQ3: What specific UGS access challenges do vulnerable groups face, and how can strategies adapt for inclusivity?

- RQ4: How do green regeneration projects impact social injustices, and what strategies promote their inclusivity and equity?

2. Methodological Approach

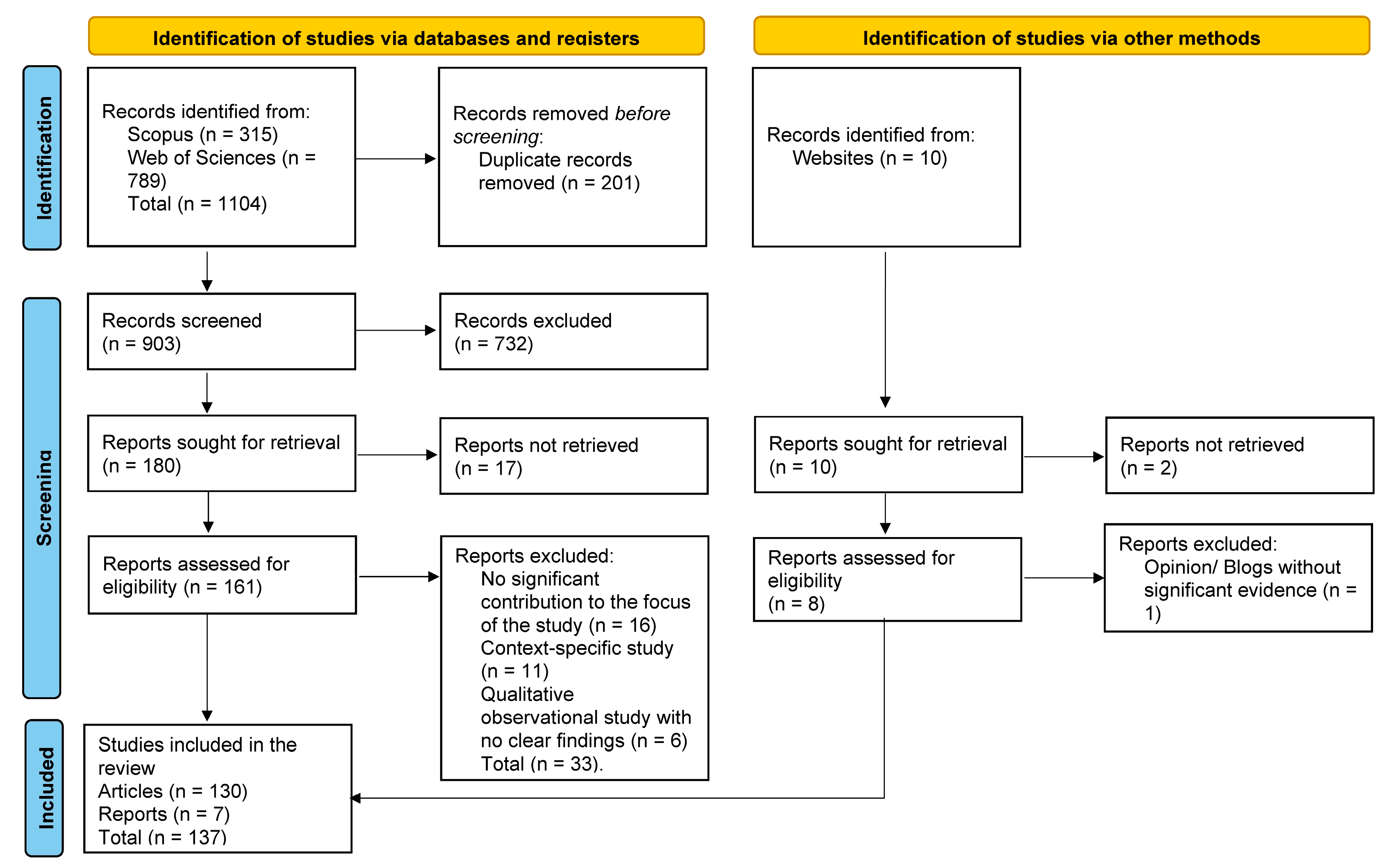

2.1. Literature Review Process and Reporting (PICOSO and PRISMA Frameworks)

2.1.1. Research Protocol for SLR

2.1.2. Search Strategy

Identification

Screening Process

Data Extraction and Quality Appraisal

Eligibility and Inclusion in the Study

2.2. Case Studies Selection

2.3. Analysis and Synthesis

2.3.1. Record Search Analysis

2.3.2. Thematic Analyses

3. Results from Literature Review

3.1. Characteristics of Documents Used for Review

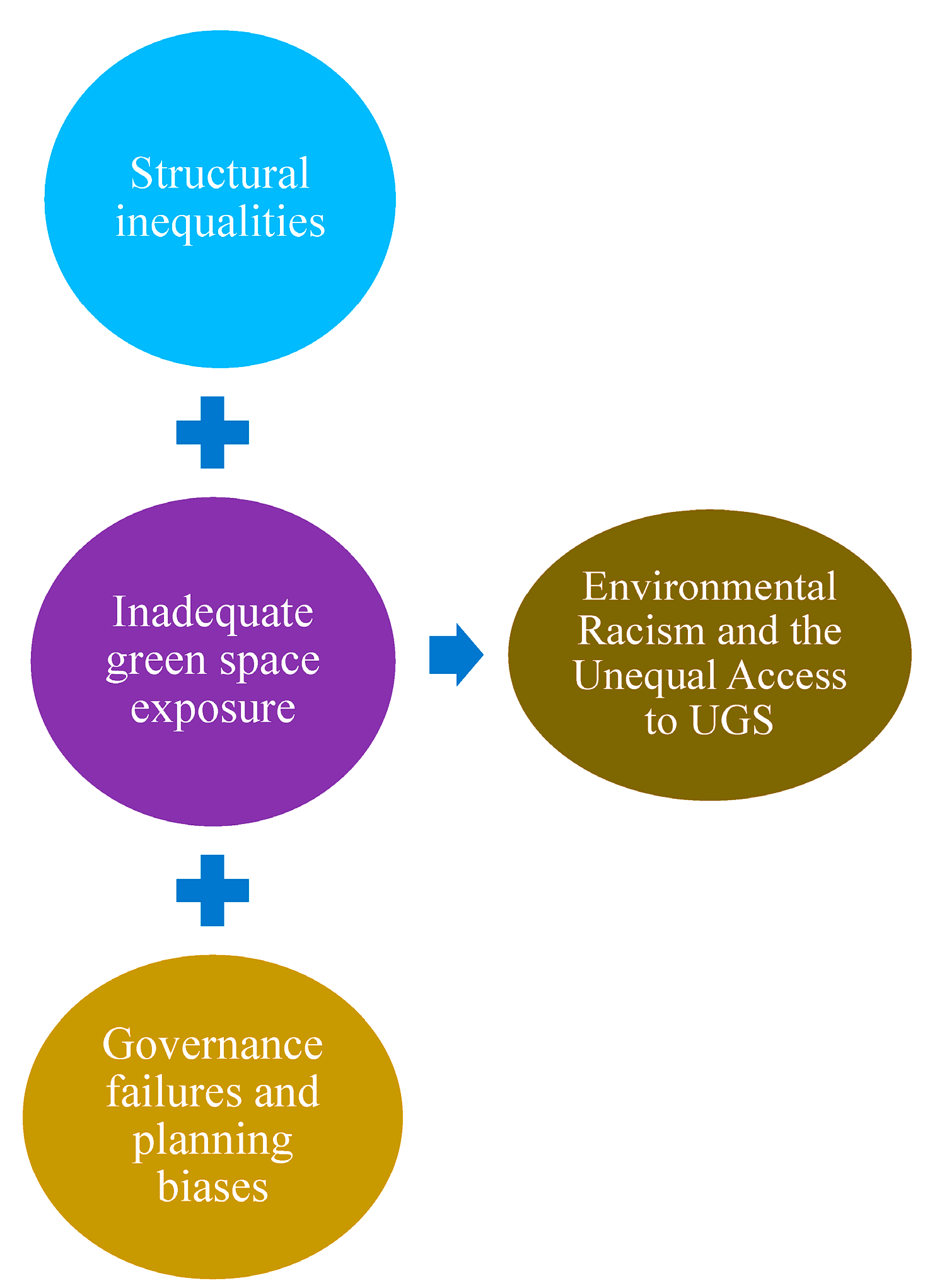

3.2. Environmental Racism and the Unequal Access to UGS

3.3. Gentrification Risks and Urban Planning for Green Space Development

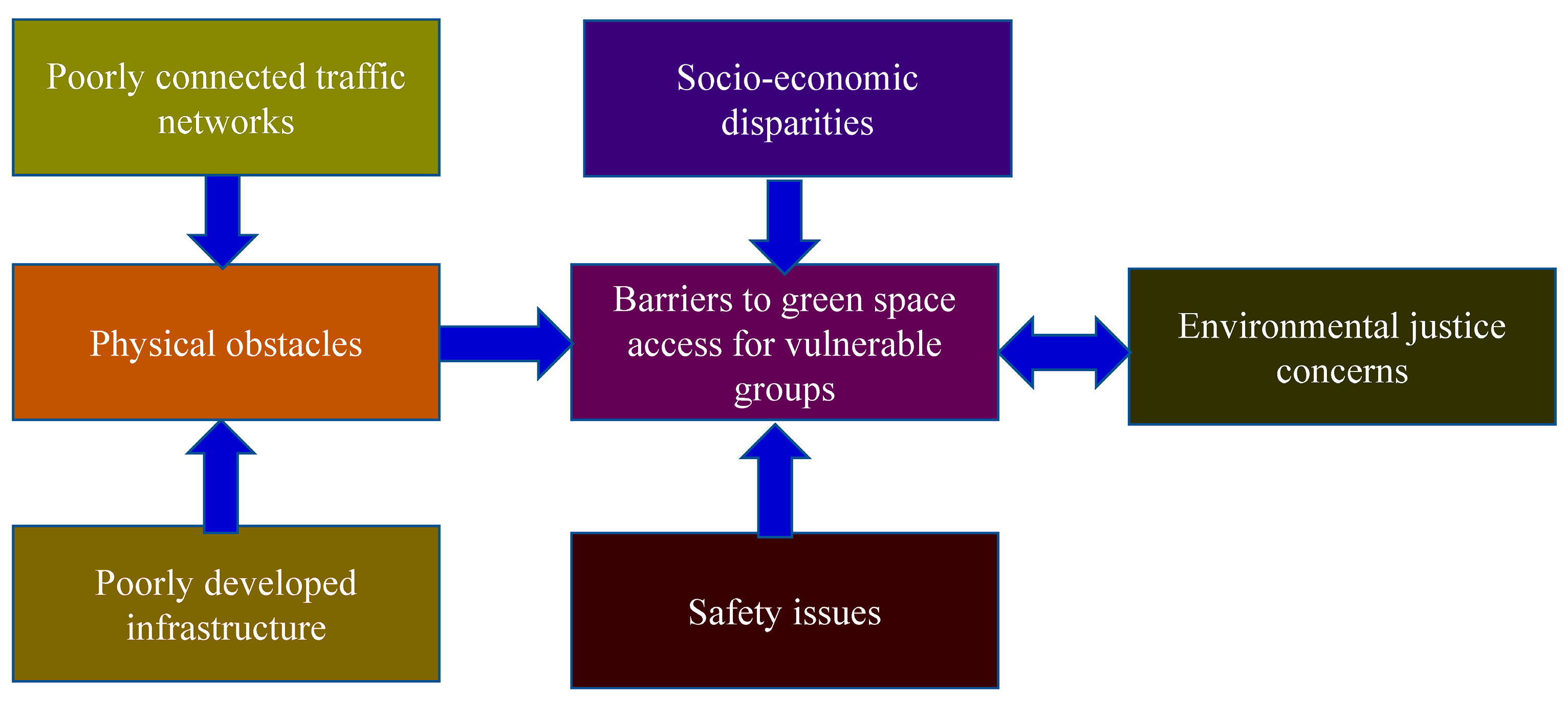

3.4. Specific Challenges Faced by Vulnerable Groups in Accessing UGS, and Urban Strategies to Ensure Inclusivity

3.5. Impact of Green Regeneration Projects on Social Justice and Strategies for Inclusivity

4. Findings from Case Studies

4.1. Washington, D.C: Anacostia River Revitalisation

4.2. Seattle: Urban Greening and Community Displacement

4.3. Amsterdam: Green Space Development and Social Equity

4.4. Mexico City: Distribution of Green Spaces and Environmental Injustice

4.5. Rio de Janeiro: Community-Led Reforestation Amidst Socioeconomic Challenges

4.6. Bhubaneswar, India: Environmental Injustice in Organised Green Spaces

5. Discussion and Strategies for More Inclusive and Equitable Green Regeneration Projects

5.1. Discussion

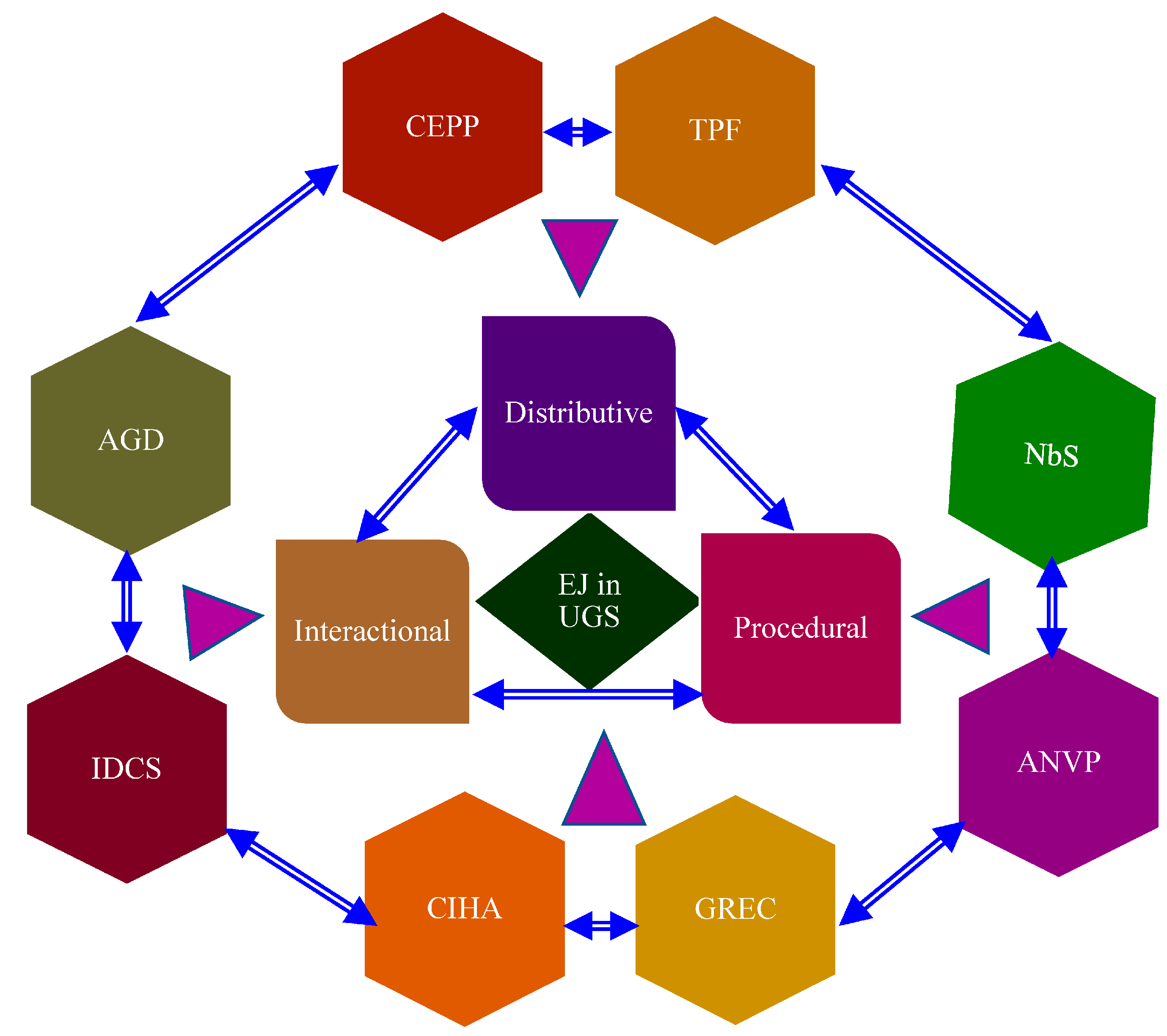

5.2. Strategies for More Inclusive and Equitable Green Regeneration

5.2.1. Community Engagement and Participatory Planning (CEPP)

5.2.2. Targeted Policies and Funding for Equitable UGS Distribution (TPF)

5.2.3. Addressing Gentrification and Displacement (AGD)

5.2.4. Inclusive Design and Cultural Sensitivity (IDCS)

5.2.5. Civic Involvement and Heterogeneous Approaches (CIHA)

5.2.6. Global and Regional Equity Considerations (GREC)

5.2.7. Addressing the Needs of Vulnerable Populations (ANVP)

5.2.8. Nature-Based Solutions (NbS)

6. Conclusions, Contributions, Limitations and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Haas, W.; Hassink, J.; Stuiver, M. The Role of Urban Green Space in Promoting Inclusion: Experiences from The Netherlands. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 618198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O.H.; Hong, I.; Yang, J.; Woo, S.; Kim, J. Urban Green Space and Happiness in Developed Countries. EPJ Data Sci. 2021, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paudel, P.; States, S.L. Urban green spaces and sustainability: Exploring the ecosystem services and disservices of grassy lawns versus floral meadows. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 84, 127932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazbei, M.; Yesayan, T.; Yu, N.; Hutt-Taylor, K.; Ziter, C.D. Lessons from Exploring the Relationship between Livability and Biodiversity in the Built Environment. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 113, 129110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D. Factors and strategies for environmental justice in organised urban green space development. Urban Plan. 2022, 7, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaland, C.; van den Bosch, C.K. Challenges and strategies for urban green-space planning in cities undergoing densification: A review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, B.; Mohamed, A.R. The effect of social and spatial processes on the provision of urban open spaces. Int. J. Green Econ. 2015, 9, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, V.; Johnson Gaither, C.; Schulterbrandt Gragg, R. Promoting environmental justice through urban green space access: A synopsis. Environ. Justice 2012, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg, J.; Haase, A.; Taszkiewicz, E.; Antal, A.; Bara-vikova, A.; Biernacka, M.; Dushkova, D.; Filčák, R.; Haasee, D.; Ignatieva, M.; et al. Environmental justice in the context of urban green space availability, accessibility, and attractiveness in post-socialist cities. Cities 2020, 106, 102862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C. Urban green-space: Environmental justice & green gentrification. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2024, 61, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressane, A.; Loureiro, A.I.S.; Negri, R.G. Environmental racism in the accessibility of urban green space: A case study of a metropolitan area in an emerging economy. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, D.; Zhong, Q.; Yue, B. How green space justice in urban built-up areas affects public mental health: A moderated chain mediation model. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1442182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban Green Space, Public Health, and Environmental Justice: The Challenge of Making Cities “Just Green Enough”. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, A. Inequalities and injustices of urban green regeneration: Applying the conflict analysis perspective. Land 2024, 13, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyster, H.N.; Rodríguez González, M.I.; Gould, R.K. Green Gentrification & the Luxury Effect: Uniting Isolated Ideas towards Just Cities for People & Nature. Ecosyst. People 2024, 20, 2399621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Knöll, M. Environmental justice in the context of access to urban green spaces for refugee children. Land 2024, 13, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, W. Reframing urban nature-based solutions through perspectives of environmental justice and privilege. Urban Plan. 2022, 8, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jing, X.; Ma, R.-F.; Wang, X.-Q.; Li, G. Study on the equity of urban green space: Origin, progress, and enlightenment. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2023, 34, 2006–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, V.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Rigolon, A. Urban green space at the nexus of environmental justice and health equity. In Green Cities: Good Health; Maddock, J.E., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, L.; Quinton, J.E. Invited perspective: Nature is unfairly distributed in the United States—But that’s only part of the global green equity story. Environ. Health Perspect. 2023, 131, 11301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thuy, N.N.; Nguyen, L.V. Disentangling environmental justice dimensions of urban green spaces in cities of the Global South. In World Sustainability Series; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 149–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, O.; Rigolon, A. What has contributed to green space inequities in U.S. cities? A narrative review. J. Plan. Lit. 2024, 40, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasgaard, M.; Breed, C.; Engemann Jensen, K.; Brom, P. Connecting Urban Green Infrastructure and Environmental Justice in South Africa: Integrating Social Access, Ecology, and Design. J. Political Ecol. 2025, 32, 6213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, A.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Lee, K.; Shin, S. Access to Urban Green Space in Cities of the Global South: A Systematic Literature Review. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewartowska, E.; Anguelovski, I.; Oscilowicz, E.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Cole, H.; Shokry, G.; Perez-del-Pulgar, C.; Connolly, J.J.T. Racial Inequity in Green Infrastructure and Gentrification: Challenging Compounded Environmental Racisms in the Green City. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2024, 48, 294–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; van Leeuwen, E.; Tsendbazar, N.; Jing, C.; Herold, M. Urban green inequality and its mismatches with human demand across neighbourhoods in New York, Amsterdam, and Beijing. Landsc. Ecol. 2024, 39, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Absatarov, R.; Uulu, A.M. The influence of urban green areas on the health of citizens: A review. Hum. Ecol. 2024, 31, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, R.; Chen, B.; Wu, J. Inclusive green environment for all? An investigation of spatial access equity of urban green space and associated socioeconomic drivers in China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 241, 104926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucca, R.; Friesenecker, M.; Thaler, T. Green gentrification, social justice, and climate change in the literature: Conceptual origins and future directions. Urban Plan. 2023, 8, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, E.N.R.; Desrosiers, F.; Prokop, L.J.; Dupéré, S.; Diallo, T. Exploring the equitable inclusion of diverse voices in urban green design, planning and policy development: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e078396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G. Environmental Justice: Concepts, Evidence and Politics; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, Y. Urban green space and human health: An environmental justice perspective. Int. J. Nat. Resour. Environ. Stud. 2024, 3, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronlid, C.; Brantnell, A.; Elf, M.; Borg, J.; Palm, K. Sociotechnical analysis of factors influencing IoT adoption in healthcare: A systematic review. Technol. Soc. 2024, 78, 102675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, M.T.; Girma, B.; Ghassabian, A.; Trasande, L. Environmental Racism and Child Health. Acad. Pediatr. 2024, 24, S167–S172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holifield, R. Environmental Racism. In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology; Turner, B.S., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Lee, J.; Liu, D.; Kan, Z.; Wang, J. Identifying urban green space deserts by considering different walking distance thresholds for healthy and socially equitable city planning in the Global South. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 84, 128123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, M.; Chakraborty, M. Distribution of green spaces across socio-economic groups: A study of Bhubaneswar, India. J. Archit. Urban. 2023, 47, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wu, S.; Song, Y.; Webster, C.; Xu, B.; Gong, P. Contrasting inequality in human exposure to greenspace between cities of Global North and Global South. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.M.; Aziz, A.; Stocco, A.F.; Abdo, H.G.; Almohamad, H.; Dughairi, A.A.A.; Al-Mutiry, M. Urban green spaces distribution and disparities in congested populated areas: A geographical assessment from Pakistan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, Y.; Diop, I.; Soulé, M.; Nafiou, M.M. Urban Green Spaces Accessibility: The Current State in Niamey City, Niger. J. Glob. Ecol. Environ. 2022, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, B.R.; Chakraborty, J.; Basu, P. Social inequities in urban heat and greenspace: Analysing climate justice in Delhi, India. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidique, U. Towards just cities: An environmental justice analysis of Aligarh, India. Dev. Pract. 2024, 35, 493–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathyakumar, V.; Ramsankaran, R.; Bardhan, R. Linking remotely sensed urban green space (UGS) distribution patterns and socio-economic status (SES)—A multi-scale probabilistic analysis based in Mumbai, India. Gisci. Remote Sens. 2019, 56, 645–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udvardi, M. Bangalore: Urban Development and Environmental Injustice. Honours Thesis, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ngome, C.S.; Yeom, C. Charting sustainable paths: Balancing urban green dilemmas in East Africa. Asia Pac. J. Convergent Res. Interchang. 2024, 10, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, T.; Paul, A.; Maiti, C. Analysis of urban green spaces using geospatial techniques: A case study of Chandannagar Municipal Corporation, Hugli, West Bengal, India. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2023, 19, 370–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Tu, Y.; Huang, S. Beyond green environments: Multi-scale difference in human exposure to greenspace in China. Environ. Int. 2022, 166, 107348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Svenning, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, K.; Abrams, J.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Teng, S.N.; Dunn, R.R. Global Inequality in Cooling from Urban Green Spaces and its Climate Change Adaptation Potential. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.09725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueckner, J. Gentrification: J. Brueckner. In Selected Topics in Migration Studies; Bean, F.D., Brown, S.K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyly, E. Gentrification. In The Planetary Gentrification Reader; Lees, L., Slater, T., Wyly, E., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2022; pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pala, Ö.N.; Acar, S. Assessing a greening tool through the lens of green gentrification: Socio-spatial change around the Nation’s Gardens of Istanbul. Cities 2024, 147, 105023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xie, C. Identifying green gentrification in Chongqing Central Park based on price feature model. BCP Bus. Manag. 2022, 33, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinton, J.E.; Nesbitt, L.; Connolly, J.J.T.; Wyly, E. How common is greening in gentrifying areas? Urban Geogr. 2023, 45, 1029–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinton, J.; Nesbitt, L.; Sax, D.; Harris, L. Greening the Gentrification Process: Insights and Engagements from Practitioners. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 2024, 7, 1893–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; Stuhlmacher, M. The Green Space Dilemma: Pathways to Greening with and without Gentrification. J. Urban Aff. 2024, 47, 3236–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, L. Gentrification outcomes of greening in different urbanisation stages: A longitudinal analysis of Chinese cities, 2012–2020. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2024, 52, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, R.; Roebeling, P.; Fidélis, T.; Saraiva, M. Can policy instruments enhance the benefits of nature-based solutions and curb green gentrification? The case of Genova, Italy. Environ. Dev. 2024, 50, 100995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, A.; Fernandez, M.; Harris, B.; Stewart, W. An Ecological Model of Environmental Justice for Recreation. Leisure Sci. 2019, 44, 655–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaad, R.; Jezzini, Y. Green gentrification vulnerability index (GGVI): A novel approach for identifying at-risk communities and promoting environmental justice at the census-tract level. Cities 2024, 145, 104858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droste, J.; Gianoli, A. Green gentrification: A fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis of greened neighbourhoods in Berlin. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2024, 68, 3193–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oscilowicz, E.; Anguelovski, I.; García-Lamarca, M.; Cole, H.; Shokry, G.; Pérez-del-Pulgar, C.; Argüelles, L.; Connolly, J.J.T. Grassroots mobilisation for a just, green urban future: Building community infrastructure against green gentrification and displacement. J. Urban Aff. 2023, 47, 347–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, J. Policy Implications of Urban Greening to Sustainable Gentrification: A Case Study of Quezon City, Philippines. Ph.D. Thesis, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnowska-Heciak, M.; Suchocka, M.; Błaszczyk, M.; Muszyńska, M. Urban parks as perceived by city residents with mobility difficulties: A qualitative study with in-depth interviews. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y. A study on urban park design from the perspective of environmental perception: Exploring future landscapes to enhance well-being and social inclusion for vulnerable groups. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2025, 122, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffimann, E.; Barros, H.; Ribeiro, A.I. Socioeconomic inequalities in green space quality and accessibility—Evidence from a Southern European city. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Mavoa, S.; Smith, M. Inequalities in urban green space distribution across priority population groups: Evidence from Tāmaki Makaurau, Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand. Cities 2024, 149, 104972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Bai, Y.; Geng, T. Examining spatial inequalities in public green space accessibility: A focus on disadvantaged groups in England. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovsiankin, O.; Nosal, S. Inclusive urban planning initiatives. Space Dev. 2024, 8, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, K.M.A.; Zhang, D. Analysing the level of accessibility of public urban green spaces to different socially vulnerable groups of people. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, A.; Christensen, J. Examining facilitators and challenges to implementing equitable green space policies: Lessons from Los Angeles County. J. Urban Aff. 2023, 47, 488–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, V.S. What is inclusive and accessible public space? J. Public Space 2022, 7, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, V.S.; Meyer, S.W.; Cruz, J.P. The Inclusion Imperative: Forging an Inclusive New Urban Agenda. J. Public Space 2017, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Selanon, P.; Chuangchai, W. Improving Accessibility to Urban Greenspaces for People with Disabilities: A Modified Universal Design Approach. J. Plan. Lit. 2023, 39, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacka, M. Green Space Provision and Equity in the City. In Equity in the Urban Built Environment; Bereitschaft, B., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, W.; Qin, L.; Jiao, S.; Zhang, R. An innovative approach for equitable urban green space allocation through population demand and accessibility modelling. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petríková, D.; Petríková, L. Inclusive and Accessible SMART City for All. In Smart Governance for Cities: Perspectives and Experiences; Lopes, N., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silveira, A.O.; Bichueti, R.S. Cidades inteligentes e neurodiversidade: Discussão sobre a necessidade de espaços urbanos inclusivos para todos (ensaio). Cidades. Comunidades E Territ. 2024, 48, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, J.E.; Eisenberg, Y.; Hosseini, M.; Azenkot, S.; Bigham, J.P.; Campbell, H.; Chava, V.; D’Souza, R.; Ferres, L.; Goodchild, M.; et al. The future of urban accessibility for people with disabilities: Data collection, analytics, policy, and tools. In Proceedings of the International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Athens, Greece, 9–12 October 2022; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, G.; Dongying, L.; Rui, Z.; Dingding, R. Resilience through regeneration: The economics of repurposing vacant land with green infrastructure. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2018, 6, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, C. The impact of urban regeneration and environmental improvements on well-being. Int. J. Educ. Humanit. 2024, 16, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zaan, T.; van ‘t Hof, S. Regeneration of Degraded Land with Nature-Based Solutions. In Design for Regenerative Cities and Landscapes; Roggema, R., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, A.D. Siting green infrastructure: Legal and policy solutions to alleviate urban poverty and promote healthy communities. BC Envtl. Aff. L. Rev. 2010, 37, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, V.; Baptiste, A.; Jelks, N.; Skeete, R. Urban green space and the pursuit of health equity in parts of the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Jin, C.; Li, T. Megacity urban green space equity evaluation and its driving factors from supply and demand perspective: A case study of Tianjin. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 474, 143583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, A.; Koprowska, K.; Borgström, S. Green regeneration for more justice? An analysis of the purpose, implementation, and impacts of greening policies from a justice perspective in Łódź Stare Polesie (Poland) and Leipzig’s inner east (Germany). Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 136, 726–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainisio, N.; Boffi, M.; Piga, B.E.A.; Stancato, G.; Fumagalli, N. Community-based participatory research for urban regeneration: Bridging the dichotomies through the EIA method. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2024, 34, e2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander, W. Striving for just green enough. Agora 2017, 62, 62–66. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, D.; Marat-Mendes, T.; Falanga, R.; Henfrey, T.; Penha-Lopes, G. Towards a Necessary Regenerative Urban Planning: Insights from Community-Led Initiatives for Ecocity Transformation. Cidades Comunidades e Territórios 2021, 21, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mell, I.C. Examining the role of green infrastructure as an advocate for regeneration. Front. Sustain. Cities 2022, 4, 731975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolnicki, J.; Woodhatch, A.L.; Stafford, R. Assessing environmentally effective post-COVID green recovery plans for reducing social and economic inequality. Anthr. Sci. 2022, 1, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguelovski, I.; Brand, A.L.; Ranganathan, M.; Hyra, D. Decolonising the green city: From environmental privilege to emancipatory green justice. Environ. Justice 2022, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elderbrock, E.; Russel, K.; Ko, Y.; Budd, E.; Gonen, L.; Enright, C. Evaluating urban green space inequity to promote distributional justice in Portland, Oregon. Land 2024, 13, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazar, M.; Hestad, D.; Mangalagiu, D.; Saysel, A.K.; Ma, Y.; Thornton, T.F. From urban sustainability transformations to green gentrification: Urban renewal in Gaziosmanpaşa, Istanbul. Clim. Change 2020, 160, 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubanza, N.S.; Das, D.K.; Simatele, D. Some happy, others sad: Exploring environmental justice in solid waste management in Kinshasa, the Democratic Republic of Congo. Local Environ. 2016, 22, 595–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Álvarez, R. Inequitable distribution of green public space in Mexico City: An environmental injustice case. Econ. Soc. Territ. 2017, 17, 399–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, F.A.; Scarlett, R. Escaping the practice of exclusion. In Just Green Enough; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023; pp. 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breyer, B.; Mohr, H. Right tree, right place for whom? Environmental Justice and Practices in Urban Forest Assessment. Local Environ. 2023, 28, 1082–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguelovski, I.; Connolly, J.J.T.; Pearsall, H.; Shokry, G.; Checker, M.; Maantay, J.; Gould, K.; Lewis, T.; Maroko, A.; Roberts, J.T. Opinion: Why green “climate gentrification” threatens poor and vulnerable populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 26139–26143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, M.D.; Van Zandt, S. Unequal protection revisited: Planning for environmental justice, hazard vulnerability, and critical infrastructure in communities of colour. Environ. Justice 2021, 14, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, N.; Bokare, M.; Harrison, R.; Yonkos, L.T.; Pinkney, A.E.; Murali, D.; Ghosh, U. Codeployment of passive samplers and mussels reveals major source of ongoing PCB inputs to the Anacostia River in Washington, DC. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 1320–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, N. DC Sues the US government over Anacostia River pollution. Reuters, 10 January 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Washington Post DC. Attorney general sues federal government over Anacostia River pollution. The lawsuit claims that the U.S. government for decades used the Anacostia as a “cost-free toxic dumping ground”. Washington Post, 10 January 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Avni, N.; Fischler, R. Social and environmental justice in waterfront redevelopment: The Anacostia River, Washington, D.C. Urban Aff. Rev. 2020, 56, 1779–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, C.A.; Green, O.O.; DeCaro, D.A.; Chase, A.; Ewa, J.G. Resilience of the Anacostia River Basin: Institutional, social, and ecological dynamics. In Resilience in Ecology and Urban Design; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glennie, C. Gardens in the growth machine: Seattle’s P-Patch program and the pursuit of permanent community gardens. In Urban Agriculture and the Struggle for Land; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 154–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, H. Seattle’s Central District, 1990–2006: Integration or displacement. Urban Lawyer 2007, 39, 167–256. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=970310 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Abel, T.D.; White, J.; Clauson, S. Risky business: Sustainability and industrial land use across Seattle’s gentrifying riskscape. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15718–15753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, N. Alaska Air and Delta must face lawsuit over Seattle airport pollution. Reuters, 27 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, C. Alaska Air and Delta targeted in Seattle airport pollution lawsuit. FOXBusiness, 28 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Anguelovski, I.; Connolly, J.J.T.; Cole, H.; Pearsall, H.; Zografos, C.; Shi, L.; Sekulova, F.; Alier, M.; Del Pulgar, C.P.; Oscilowicz, E.; et al. Green gentrification in European and North American cities. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 31572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingle, M. Emerald City: An Environmental History of Seattle; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dommerholt, T. Environmental (In)justice in Amsterdam Greening Policy: A Case Study on the Social Impact of Green Interventions. Master’s Thesis, Wageningen University & Research, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pellerey, V.; Giezen, M. More green but less just? Analysing urban green spaces, participation, and environmental justice in Amsterdam. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2024, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Strohbach, M.; Haase, D.; Kronenberg, J. Urban Green Space Availability in European Cities. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 70, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, S.; Buijs, A.; Snep, R.P.H. Environmental justice in The Netherlands: Presence and quality of greenspace differ by socioeconomic status of neighbourhoods. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruize, H.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Glasbergen, P.; van Egmond, K.; Dassen, T. Environmental equity in the vicinity of Amsterdam Airport: The interplay between market forces and government policy. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2007, 50, 699–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cator, C. Transforming the City for Sustainable Futures? Contestation and Alternatives in Amsterdam. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Azcárraga, C.; Díaz, D.; Fernández, T.; Córdova-Tapia, F.; Zambrano, L. Uneven distribution of urban green spaces in relation to marginalisation in Mexico City. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Mata, A. Urban sprawl, environmental justice and equity in the access to green spaces in the metropolitan area of San Luis Potosí, Mexico. In Urban Transformations; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Bernabé, G.; Chacalo-Hilu, A.; Nava-Bolaños, I.; Meza-Paredes, R.M.; Zaragoza-Hernández, A.Y. Changes in the surface of green areas in two city halls of Mexico City between 1990–2015. Polibotánica 2019, 48, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, M.; del Carmen, M. The Trees of Mexico City: Guardians of Their Image and of the Environment. Bitácora Arquit. 2015, 31, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, D.D.L.H.; Martínez, S.A.; Vargas, E.C.; Alanís, J.C. Análisis espacial del Índice de Sustentabilidad Ambiental Urbana en la Megalópolis de México. Invest. Geogr. 2020, 73, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malleret, C. I think, boy, I’m a part of all this’: How local heroes reforested Rio’s green heart. The Guardian, 10 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fontes, A.S.; Galarce, F.E.; do Valle, L.M.; Motta, V.F.; da Faria, T.S. Táticas cidadãs para ativação de áreas subutilizadas: O caso das hortas comunitárias do Rio de Janeiro. Rev. Arq. Urb. 2018, 23, 135–156. [Google Scholar]

- Vílchez Ponce, L.A. Participatory action research in Rio de Janeiro’s sustainable favela network. In The City is an Ecosystem Sustainable Education, Policy, and Practice; Mutnick, D., Cuonzo, M., Griffiths, C., Leslie, T., Shuttleworth, J.M., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2022; pp. 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, O.A.; Melo, M.E. Do mito à realidade: A experiência de turismo sustentável na comunidade do Vale Encantado, Floresta de Tijuca, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Field Actions Sci. Rep. 2011, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, J.A.L. O jardim dentro da máquina: Breve história ambiental da Floresta da Tijuca. Estud. Hist. 1988, 1, 276–298. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, C.P. A multifunctional green infrastructure design to protect and improve native biodiversity in Rio de Janeiro. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 12, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, C.F.S.; Rodacoski, J.L.; Collesi, G.S.P.; de Faria, S.P. Recuperação da cobertura vegetal do Quilombo do Cabral em Paraty, RJ—Bases de um projeto socio-ambiental de extensão. Rev. Ciência Extensão 2013, 9, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, M.; Abranches Abelheira, M.; Gomes, O.S.; Fonseca, W.; Besen, D. Rio de Janeiro Community Protection Program. Procedia Econ. Finance 2014, 18, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.; Edge, S.; Millward, A.A.; Roman, L.A.; Teelucksingh, C. Centering community perspectives to advance recognitional justice for sustainable cities: Lessons from urban forest practice. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, M.; Swain, M.J.; Prusty, M. Urban green space management and planning: A case study of Bhubaneswar. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2024, 12, 5525–5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snaith, B.; Odedun, A. Weeds, wildflowers, and White privilege: Why recognising nature’s cultural content is key to ethnically inclusive urban greenspaces. J. Race Ethn. City 2023, 5, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaňo, S.; Olafsson, A.S.; Mederly, P. Advancing urban green infrastructure through participatory integrated planning: A case from Slovakia. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 58, 126957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cenci, J.; Zhang, J. Policies for Equity in Access to Urban Green Space: A Spatial Perspective of the Chinese National Forest City Policy. Forests 2024, 15, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, H.B.; Roychansyah, M.S. The Social Equity of Public Green Open Space Accessibility: The Case of South Tangerang, Indonesia. Geogr. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 16, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, J. Inclusive design: Planning public urban spaces for children. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Munic. Eng. 2007, 160, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Q. Visualising green space accessibility for more than 4,000 cities across the globe. Environ. Plann. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2022, 5, 1578–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Details |

|---|---|

| Research Questions |

|

| Database used | Scopus and Web of Science |

| Publication period | 2001–2025 |

| Keywords | Environmental Justice, Procedural Justice, Distributive Justice, Recognition Justice, Interactional Justice, Environmental Racism, Gentrification, Green Space, Open Space, Recreational Space, Equity, Inclusivity, Vulnerable Groups, Development, Planning, Management, Urban Area, Cities |

| Timeframe for literature search | June 2024 and August 2025 |

| Inclusion criteria (premised on PICOSO framework) | Population: Peer-Reviewed Journals, Books, Book Chapters, Theses, Conference Proceedings Interventions: Environmental Justice, Urban Green Space, Planning, Policies, Strategies, Development, Nature-Based Solutions Context (Comparison): Global South, Global North, Urban Areas/Cities Outcomes: Accessible, Inclusivity, Equity, Justice, Sustainability, Resiliency. Others (Language): English, French, Spanish, or Portuguese, |

| Exclusion criteria | Non-Peer-Reviewed Articles, Patents, Laws, Treaties, Not Aligned to Urban Green Spaces, Environmental Justice, Selective Reporting, Specific Contextual Studies, Qualitative Observational Studies, Blogs/Opinions Without Evidence |

| Data extraction | Used a standardised form (spreadsheet) to capture all relevant data |

| Quality assessment | Used the 27 PRISMA checklist to assess methodological quality, Risk of Bias (ROB2) analysis and Cohen’s Kappa analysis |

| Analytical approach | Use narrative and thematic analysis to synthesise the data. |

| Software used | Biblioshiny in the R software Package |

| Sl No | Themes | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Definitions and concepts of EJ | Dimensions of EJ: Distributional, Procedural and recognition EJ |

| 2 | Environmental Racism and the Unequal Access to UGS | Accessibility & Equity |

| Structural inequality | ||

| Governance failures | ||

| 3 | Gentrification Risks and Urban Planning for Green Space Development | Green gentrification |

| Distribution of UGS and Anti-displacement policies | ||

| Governance and Zoning & Regulation | ||

| 4 | Specific challenges faced by vulnerable groups in accessing UGS, and urban policies to ensure inclusivity | Community participation and Vulnerable groups’ access |

| Cultural inclusivity | ||

| Physical barriers | ||

| Safety & exclusion | ||

| 5 | Green Regeneration & Social Justice | Inclusive regeneration |

| Risks of eco-gentrification |

| Literature Source | Numbers | Share (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Journal articles | 109 | 79.56 |

| Conference Proceedings | 2 | 1.46 |

| Books | 6 | 4.38 |

| Book chapters | 10 | 7.30 |

| Thesis | 3 | 2.19 |

| Web articles/Reports | 7 | 5.11 |

| Total | 137 | 100.00 |

| Measure | Value | Std. Error | Approx. T | N of Valid Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohen’s Kappa (k) | 0.792 | 0.079 | 9.219 | 128 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Das, D.K. Exploring the Intersection of Environmental Justice and Urban Green Space Planning: A Systematic Review. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120540

Das DK. Exploring the Intersection of Environmental Justice and Urban Green Space Planning: A Systematic Review. Urban Science. 2025; 9(12):540. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120540

Chicago/Turabian StyleDas, Dillip Kumar. 2025. "Exploring the Intersection of Environmental Justice and Urban Green Space Planning: A Systematic Review" Urban Science 9, no. 12: 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120540

APA StyleDas, D. K. (2025). Exploring the Intersection of Environmental Justice and Urban Green Space Planning: A Systematic Review. Urban Science, 9(12), 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120540