1. Introduction

In the late twentieth century, Riyadh underwent a transformation from a desert town into a metropolis, driven by oil wealth, state-led modernization, and national aspirations for globalization [

1,

2]. While scholars have documented the city’s infrastructural growth and planning, few have examined how architecture, particularly buildings integrating urban design principles, reshaped public life during this rapid change.

During the 1980s and 1990s, civic and cultural buildings began to depart from introverted typologies (inward courtyards and car-dependent access) by incorporating landscaped plazas, shaded walkways, and pedestrian-friendly interfaces [

3]. Throughout this study, the term public space is used as the principal analytical concept, encompassing both the physical and social dimensions of spatial openness. The related term open space is employed only when referring to the architectural and environmental form that enables public interaction [

4]. In this sense, open space is treated as the material substrate through which public space—understood as a socially produced and culturally negotiated condition—becomes manifest. This distinction ensures conceptual precision while maintaining alignment with the study’s broader theoretical framework of publicness and architectural mediation.

These designs introduced semi-public spaces for gathering, visibility, and accessibility within Riyadh’s segregated urban fabric [

5]. Although subtle, they enabled new experiences of publicness, leisure, and civic interaction—key to understanding the city’s negotiated modernity.

Despite their significance, these architectural interventions remain understudied. Existing literature on Riyadh’s urban development primarily focuses on master planning, infrastructure, or stylistic evolution, neglecting the role of public-space designs in shaping lived experience and socio-spatial culture [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. A critical gap persists in understanding architecture’s role in producing public space within contexts of cultural conservatism, gender segregation, and climatic constraints. Consequently, the impacts of these projects remain under-theorized in the urban studies discourse. In this context, Riyadh’s architectural modernization can be understood as the emergence of public-scapes, spatial fields where architecture, climate, and civic life converge to redefine visibility and participation within culturally conservative settings. These emerging public-scapes illustrate how architecture mediates social transformation not through radical openness, but through layered, negotiated permeability, establishing the conceptual foundation for the analysis that follows.

As a result, this study examines how the architectural design of open spaces transformed Riyadh (1980s–1990s), analyzing their spatial logic, socio-cultural impacts, and urban planning implications. Focusing on this transitional period, when Riyadh evolved from an administrative capital to a metropolitan hub, the research investigates how architecture mediated between modernization and cultural preservation.

Framed within theories of urban sociology, public space production, and spatial behavior, this study examines the intersection of architecture with social practices and planning to mediate urban transformation. The research addresses its central question of how open-space architectural designs transformed urban life in Riyadh during the 1980s–1990s through case studies of key projects that introduced public spatiality. These buildings are analyzed through their formal strategies, spatial organization, user experience, and urban influence.

To strengthen the study’s theoretical coherence, this study explicitly anchors its argument in three intersecting frameworks that recur throughout the analysis. First, Lefebvre’s concept of production of space provides the foundation for interpreting architecture as a social construct that mediates between material form and lived experience. Second, relational urbanism informs the study’s understanding of how openness operates not merely as a physical attribute but as a dynamic condition negotiated through cultural, climatic, and institutional forces. Third, the concept of architectural agency, as discussed by Awan, Schneider, and Till (2011) [

11] and Carmona (2021) [

12], underpins the analysis of how design choices can both reflect and reshape civic life within constrained governance systems. Together, these frameworks structure the comparative reading of the three case studies, ensuring that discussions of form, behavior, and symbolism remain theoretically grounded and conceptually consistent across the paper.

Accordingly, this study is guided by the following central research question: How did architectural interventions integrating open-space design principles mediate the transformation of public life and civic identity in Riyadh during the 1980s–1990s, and what theoretical insights does this offer into the relational production of public space in culturally conservative, rapidly modernizing contexts? This question is examined through the lens of the three theoretical pillars introduced earlier: production of space, relational urbanism, and architectural agency. These frameworks collectively inform how we interpret the selected case studies not merely as design objects but as active mediators of social transformation. Through this lens, “controlled openness” and “hybrid publicness” emerge as central analytical concepts that connect architectural form with socio-spatial behavior, enabling the paper to trace how design mediates between modernization and cultural continuity within Riyadh’s evolving urban fabric.

By positioning architecture as an active urban agent, the study challenges the divide between architecture and urbanism in Middle Eastern contexts. It reveals how Saudi cities, often viewed as products of top-down planning, experienced bottom-up transformations through architectural interventions. Thus, the research identifies open-space architecture as a critical yet underrecognized factor in Riyadh’s socio-spatial evolution during this pivotal period.

The selection of the 1980s–1990s as the study period is intentional and grounded in both historical and theoretical rationale. This era marked Riyadh’s first major architectural confrontation with the challenges of modernization, when the state’s oil-driven expansion coincided with a growing awareness of cultural identity and environmental adaptation. During these decades, architecture became a testing ground for reconciling global design influences with local socio-religious norms, resulting in the emergence of hybrid typologies that mediated between tradition and modernity. By focusing on this formative period, the study captures the foundational moment when public space was first consciously articulated as part of the city’s modernization agenda. Moreover, examining this transitional phase offers valuable lessons for contemporary practice, revealing how negotiated openness and culturally informed design can guide present and future urban transformations in rapidly modernizing cities, particularly across the Arab world and the Global South.

2. Literature Review

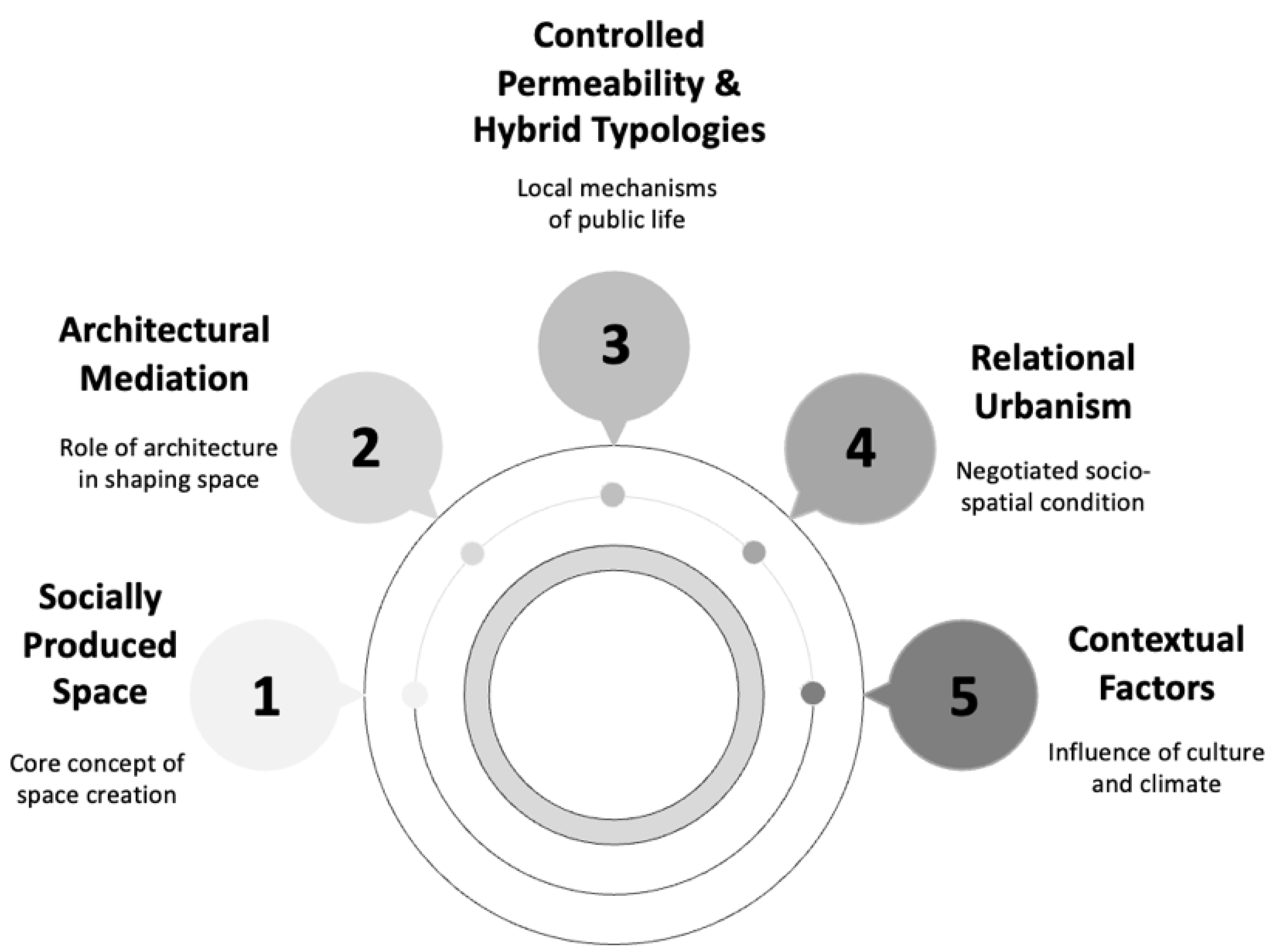

This literature review examines how architectural form mediates the production of public space in Riyadh’s urban landscape. Engaging global, regional, and local discourse, it positions the city within debates on urban openness, spatial behavior, and socio-cultural transformation. The review’s multi-scalar approach, from international models to local typologies, informs the study’s analytical framework, synthesizing five key concepts: socially produced space, architectural mediation, controlled permeability/hybrid typologies, relational urbanism, and contextual factors. These interrelated concepts, derived from the literature, guide the subsequent case study analysis while maintaining a focus on architecture’s role in shaping public life across comparable contexts.

This study interprets Riyadh’s late twentieth-century transformation through the lens of “public-scapes of controlled openness”, spatial fields where architecture, governance, and social life intersect to produce negotiated forms of civic visibility [

13] (

Figure 1). These public-scapes emerge not as fixed physical domains but as dynamic environments shaped by climatic adaptation, cultural codes, and institutional power. Within such terrains, architectural mediation operates simultaneously at formal, behavioral, and symbolic levels, translating state-led modernization into lived spatial experiences. By framing these open-space interventions as evolving public-scapes, the study highlights the relational and adaptive character of urban transformation, where architecture becomes both an agent and a register of social change.

2.1. Global Perspectives on Architecture, Urban Design, and Public Space

The architectural integration of public space has historically enhanced the urban quality of life, serving not only as activity containers but also as tools that shape social interaction, civic behavior, and urban identity. Western and global discourse has extensively examined architecture’s role in the formation of publicness, particularly in post-industrial regeneration, modernist planning, and participatory urbanism [

14]. This section situates Riyadh’s developments within these global theoretical and practical frameworks.

Lefebvre’s (2012) [

15] seminal work frames urban space as a social product shaped by perception, representation, and practice, revealing architecture as inherently political in its organization of visibility and access. In parallel, Gehl (2011) [

16] and Whyte (1980) [

17] demonstrated how human-scale design elements (permeability, seating, visual connectivity) directly influence pedestrian behavior and urban vitality through empirical studies of Copenhagen, New York, and Melbourne.

Modernist planning’s legacy, epitomized by Le Corbusier’s Radiant City, prioritized functional zoning over spatial integration [

18]. Its critique spawned New Urbanism’s emphasis on walkability and mixed-use design [

19], as seen in projects such as Barcelona’s Olympic Village waterfront regeneration and New York’s High Line adaptive reuse [

20,

21].

Middle Eastern contexts present distinct challenges, where climate, privacy norms, and rapid development have historically limited public space integration. Top-down experiments, such as Doha’s Education City [

22] and Masdar City [

23], contrast with Istanbul’s Gezi Park [

24], revealing the political potency of public space.

Riyadh’s 1980s–1990s open-space adaptations reflect this global-local negotiation. Unlike European plazas that enable spontaneous gatherings, Riyadh’s shaded walkways and courtyards function as semi-public filters [

25], mirroring Southeast Asia’s hybrid courtyard-urbanism [

26,

27]. Crucially, publicness emerged programmatically through libraries and campuses, rather than through dedicated civic squares—a distinctive model of spatial production.

This comparative analysis positions Riyadh as a critical case of contextual adaptation, where global design principles are reinterpreted through local spatial codes to produce novel urban experiences under specific climatic, cultural, and governance conditions. Taken together, these international trajectories foreshadow the emergence of context-specific public-scapes, where spatial openness operates as a relational field linking built form, social encounter, and environmental mediation rather than as a static urban type.

2.2. Regional and Gulf Context

The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) architecture has become a primary medium for expressing national identity and urban modernity; however, public space integration remains uneven due to cultural conservatism, climatic constraints, and state-driven urbanization. Unlike Western bottom-up public space formation, Gulf publicness typically emerges through curated top-down interventions [

28].

Doha, Dubai, and Abu Dhabi have pioneered large-scale projects combining architectural spectacle with programmed public environments. Msheireb Downtown Doha exemplifies this shift toward context-sensitive urbanism through its vernacular-inspired courtyards and walkways, though critics note its exclusivity [

29]. Similarly, Dubai’s Design District (d3) blends commercial and cultural functions with pedestrian design, albeit serving niche demographics [

30]. In contrast, Kuwait’s Shaheed Park exemplifies how open-space architecture can successfully integrate leisure, culture, and environmental adaptation [

31], thereby redefining state-civil society relations through spatial means [

32].

Riyadh’s trajectory differs significantly, shaped by state agencies like the Arriyadh Development Authority emphasizing controlled modernization over cosmopolitan display [

33,

34]. While the 1980s Diplomatic Quarter represented early open-space integration, most late 20th-century development remained fragmented [

35]. The 1980s–1990s saw institutional buildings begin to embed semi-public spaces, as seen in the King Fahad National Library’s permeable plaza [

36], mirroring Jeddah’s incremental improvements in waterfront accessibility [

37,

38].

Regional scholarship challenges Western public space paradigms, emphasizing Gulf-specific configurations of access, visibility, and programmed use [

39,

40,

41]. Riyadh’s malls and cultural buildings create alternative publicness models that transcend traditional binaries [

42], reflecting the region’s broader spectrum from commodified to contextually responsive spaces.

2.3. Contextual Foundations: Riyadh in the Late 20th Century

Riyadh’s late 20th-century transformation reflected Saudi Arabia’s post-oil boom urbanization, distinguished by centralized governance and controlled modernization [

43]. Unlike Dubai and Doha’s globalized development, Riyadh’s growth followed state-led planning through the Arriyadh Development Authority (ADA), prioritizing infrastructure over human-scale design [

36,

44]. This created tensions between Najdi cultural norms of privacy and the functional needs of a modern capital, mirroring regional patterns seen in Cairo and Tehran [

45,

46].

The 1980s Diplomatic Quarter (DQ) represented Riyadh’s most ambitious open-space experiment, combining modernist planning with regionalist architecture through the use of pedestrian paths and shaded courtyards [

47,

48]. While pioneering, its principles remained confined mainly to this enclave. Mainstream development continued to feature walled compounds and car-centric layouts, though exceptions, such as King Saud University’s courtyard design and the King Fahad National Library’s setbacks, hinted at evolving approaches [

49].

This period saw the emergence of “controlled openness”—spatial filters accommodating public interaction within socio-religious norms [

12], comparable to adaptations in Amman and Muscat. Gendered urbanism played a crucial role, as architecture negotiated women’s increasing public participation through the use of layered spatial hierarchies [

50].

These fragmented yet significant interventions laid the foundations for rethinking architecture’s role in Riyadh’s urban life, striking a balance between modernization and cultural continuity through adaptive spatial strategies rather than radical breaks. These incremental adaptations can be read as the early formation of Riyadh’s proto-public-scapes, transitional environments through which architectural design began translating modernization ideals into socially negotiable urban forms.

2.4. Architectural Typologies and Quality of Urban Life

Architectural typologies serve as socio-spatial mediators between users and their environments, shaping accessibility, sociability, and the symbolic meaning of these spaces. In Riyadh, traditional inward-oriented forms (courtyard houses, madrasa-like institutions) have gradually incorporated extroverted elements (arcades, atriums, transition zones) since the 1980s–1990s, adapting modernist vocabularies through cultural filters [

51,

52].

This typological evolution mirrors global trends toward permeable, interactive spaces. While Scandinavian schools use open plazas to enhance collaboration [

53], and Singapore’s public buildings employ atriums for communal use, Riyadh’s adaptations remain more constrained. Hybrid projects, such as Dhahran’s Ithra, demonstrate how cultural institutions can blend spatial fluidity with contextual envelopes [

54].

Commercial architecture reveals unique adaptations. Riyadh’s malls emerged as quasi-public typologies, offering climate-controlled spaces that paradoxically enhanced social inclusion by accommodating traditional gender norms [

55,

56]. Cultural buildings, such as the renovated King Fahad National Library, introduced plazas and pedestrian linkages, signaling a shift from authoritarian fortresses to experience facilitators [

57].

Theoretical frameworks highlight the transition from autonomous to relational typologies, prioritizing urban connectivity [

58], as reflected in Riyadh’s UN-Habitat indicators, which emphasize public space provision [

59]. However, innovation remains concentrated in flagship projects, while car-oriented typologies still dominate the broader urban fabric, lagging Muscat’s traditional form guidelines or Doha’s mixed-use experiments. Collectively, these evolving typologies reveal how Riyadh’s architecture gradually assembled a mosaic of public-scapes of controlled openness, prefiguring the civic environments analyzed in the case studies.

3. Research Methodology

This research adopted a qualitative multiple-case study approach to examine how open-space architectural projects shaped Riyadh’s urban life (1980s–1990s). The method enables the deep analysis of complex socio-spatial phenomena within their cultural context [

60]. Studying multiple cases provides both individual depth and comparative insights, offering robust empirical grounding while maintaining analytical flexibility for cross-case examination.

3.1. Case Study Selection Criteria

The case studies were selected through purposeful sampling (

Table 1), guided by four criteria:

- 1.

Temporal relevance: Projects built or significantly redeveloped between the 1980s–1990s.

- 2.

Integration of open space: Incorporation of plazas, courtyards, arcades, promenades, or other forms of open-space design directly connected to the building’s program.

- 3.

Public and civic function: Buildings that serve governmental, cultural, institutional, or semi-public purposes, contributing to Riyadh’s civic or cultural life.

- 4.

Urban and planning significance: Projects that influenced or responded to broader urban planning strategies, spatial policies, or socio-cultural practices.

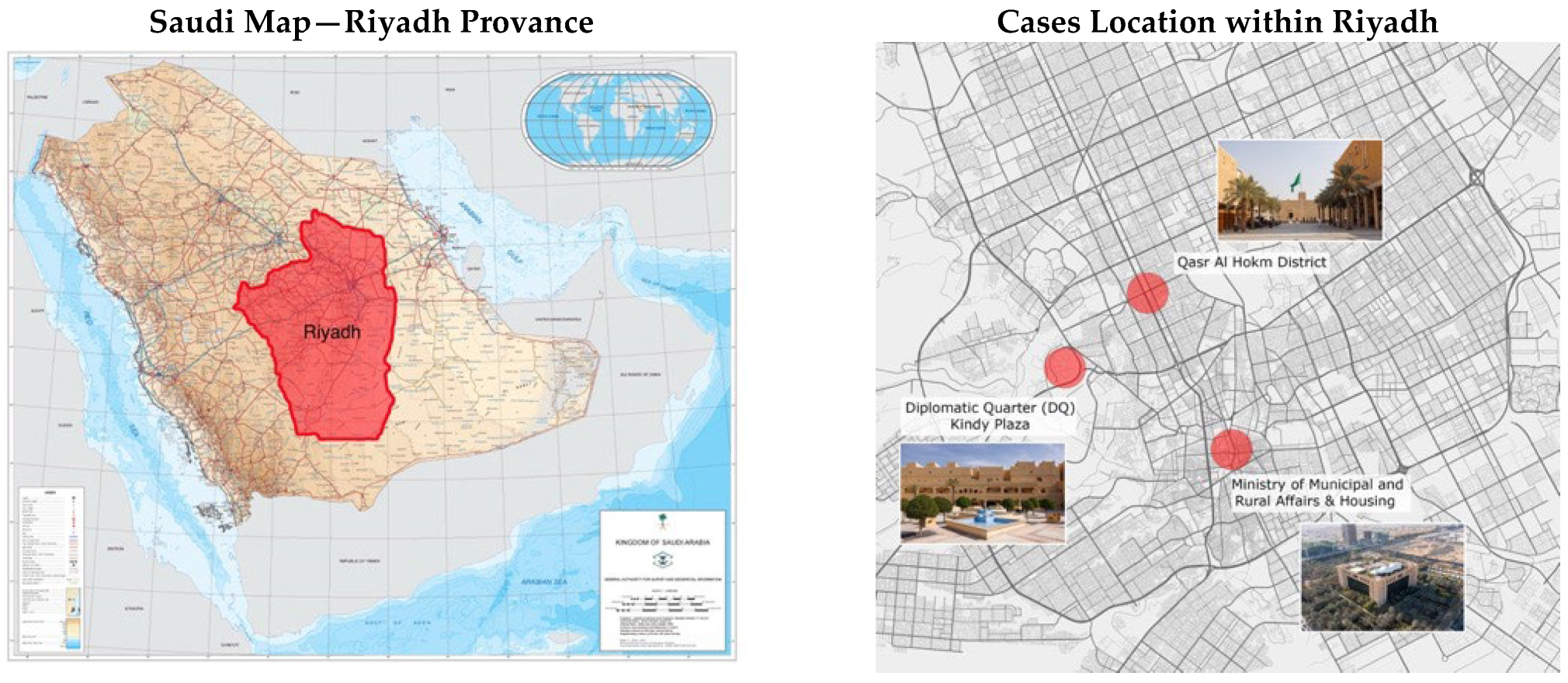

Accordingly, three projects were chosen representing varying functions, openness levels, and urban contexts, collectively illustrating Riyadh’s open-space architectural evolution (

Figure 2).

3.2. Data Collection Methods

A multi-source, triangulated data collection strategy was employed to ensure empirical rigor, validity, and replicability. Data were collected from the following sources:

3.2.1. Archival Research

Archival data were gathered to reconstruct the planning, design, and implementation histories of each case study, such as:

Arriyadh Development Authority (ADA) reports;

Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs documents;

Municipal planning guidelines;

Architectural competition submissions and design documentation;

Academic publications, design reviews, and policy papers.

The archival foundation ensured historical accuracy and provided insight into original design intents and planning objectives.

3.2.2. Site Visit Observation

Direct on-site observations were conducted to assess:

Physical configuration and spatial organization;

Patterns of public use, circulation, and accessibility;

Social interaction behaviors and demographic diversity of users;

Environmental features related to microclimate, shading, and landscape integration;

Interfaces between building edges and the surrounding urban fabric.

Observations were conducted using a structured observation guide to ensure consistency across sites. Field notes, photographs, and site sketches were systematically documented to capture both spatial and behavioral dimensions.

3.2.3. Pedestrian Flow Counts

Basic pedestrian flow counts were conducted at selected observation points during peak and off-peak periods. These counts provided simple empirical indicators of usage intensity, temporal patterns, and variations in public engagement across sites [

61]. This minor quantitative layer enhanced the validity of the observational findings while remaining feasible and methodologically appropriate.

Counts were conducted manually by the research team at each site during two designated time intervals: 10:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m., chosen to represent mid-morning administrative hours and late afternoon peak circulation, respectively. Observations were carried out over three consecutive weekdays to account for typical workday rhythms and minimize anomalies due to special events or holidays. Each session lasted 45 min, during which individuals entering, exiting, or occupying the primary open spaces were tallied. Attention was paid to differentiating between passive users (e.g., those seated or loitering) and transient users (e.g., those walking through). This structured approach enabled cross-case comparability and alignment with the observation-based behavioral data.

3.2.4. Semi-Structured Expert Interviews

A series of semi-structured interviews were conducted with key stakeholders, including:

Architects and designers involved in the projects;

Urban planners and municipal officials;

Scholars specializing in Saudi Arabian architecture and urban studies;

Cultural practitioners and community representatives familiar with the public use of these spaces.

A total of 12 interviews were conducted between January and March 2025. Participants were selected through purposive sampling, based on their direct involvement in the planning, design, or observation of the case study sites. The sample included four architects (including two site designers), three urban planners affiliated with Riyadh’s municipal bodies, two academics specializing in Gulf urbanism, and three local cultural practitioners familiar with public use patterns. Interviews lasted between 30 and 45 min and were conducted in person or via video conferencing. Interviewee backgrounds were intentionally diversified to capture both institutional perspectives and experiential insights, ensuring a well-rounded understanding of each site’s impact (

Table 2). Also, an interview protocol was used to ensure consistency while allowing for rich narrative elaboration. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and anonymized where requested.

The interview protocol was developed around a set of open-ended questions derived from the study’s central research question and theoretical framework. Participants were asked to reflect on: (1) how architectural design mediated the relationship between public life and institutional function; (2) how climatic, cultural, or governance factors influenced the design and use of public spaces; and (3) how perceptions of openness, accessibility, and cultural representation evolved within their professional experience. Follow-up questions were used to probe specific examples or to clarify contradictions between design intent and user behavior. Each participant was interviewed once, with the opportunity for brief follow-up clarification via email when needed. The selection of stakeholders was guided by purposeful sampling to ensure the representation of professional, institutional, and cultural perspectives—specifically, architects involved in the original design, planners responsible for implementation, and cultural practitioners familiar with public life in these spaces. This diversity of perspectives allowed for triangulation between design rationale, governance practice, and user experience, providing a balanced understanding of how public space was both produced and perceived.

3.3. Data Analysis Approach

The analysis followed a thematic, comparative, and theory-informed framework:

Thematic Coding: Interview transcripts, observational data, and archival documents were coded for recurring themes related to spatial openness, public accessibility, socio-cultural negotiation, user behavior, and urban integration. Coding consistency was validated through peer-review of coding samples by a secondary researcher to ensure inter-coder reliability [

62].

Cross-Case Comparative Matrix: Systematic matrices were constructed to compare design attributes, spatial configurations, user experiences, and urban impacts across all three case studies.

Theoretical Integration: Findings were interpreted through established theoretical frameworks (e.g., the production of space, public life theory, and relational urbanism), allowing for both case-specific insight and broader conceptual synthesis [

63].

In practical terms, this integration involved mapping empirical indicators such as pedestrian counts, spatial movement patterns, and observed social behaviors onto the study’s theoretical constructs. Pedestrian flow data were used to evaluate spatial practice [

15] by identifying how users inhabited and adapted designed environments. Behavioral observations and interview narratives informed the analysis of architectural agency [

11], revealing how design intentions translated into lived experiences and cultural negotiation. Cross-case thematic coding then operationalized relational urbanism by tracing the interdependence between environmental design, governance frameworks, and social interaction. Through this iterative process, empirical patterns were not treated as isolated findings but as interpretative evidence situated within the study’s broader theoretical model of public-scapes of controlled openness.

3.4. Ethical Considerations

The study adhered to standard research ethics, obtaining informed consent and anonymizing data as requested. Observations were limited to public spaces, with proper citation of secondary sources.

The researcher’s background as both a scholar and cultural insider enabled nuanced analysis but required safeguards. Methodological triangulation (interviews, observations, archives) and peer review during analysis ensured rigor while maintaining cultural sensitivity.

All data were securely stored in encrypted files accessible only to the researchers. Interview materials were anonymized and archived. Written or recorded verbal consent was obtained from all participants, ensuring confidentiality and compliance with institutional ethics standards.

4. Architectural Transformation in Riyadh (1980–1990s)

Riyadh’s late 20th-century open-space architecture evolved gradually through contextual adaptations, striking a balance between tradition and modernity. This section analyzes three typologically diverse case studies (diplomatic, civic, governmental) through:

Together, these projects reveal how strategically integrated open spaces redefined public life, urban identity, and accessibility during Riyadh’s transformative decades.

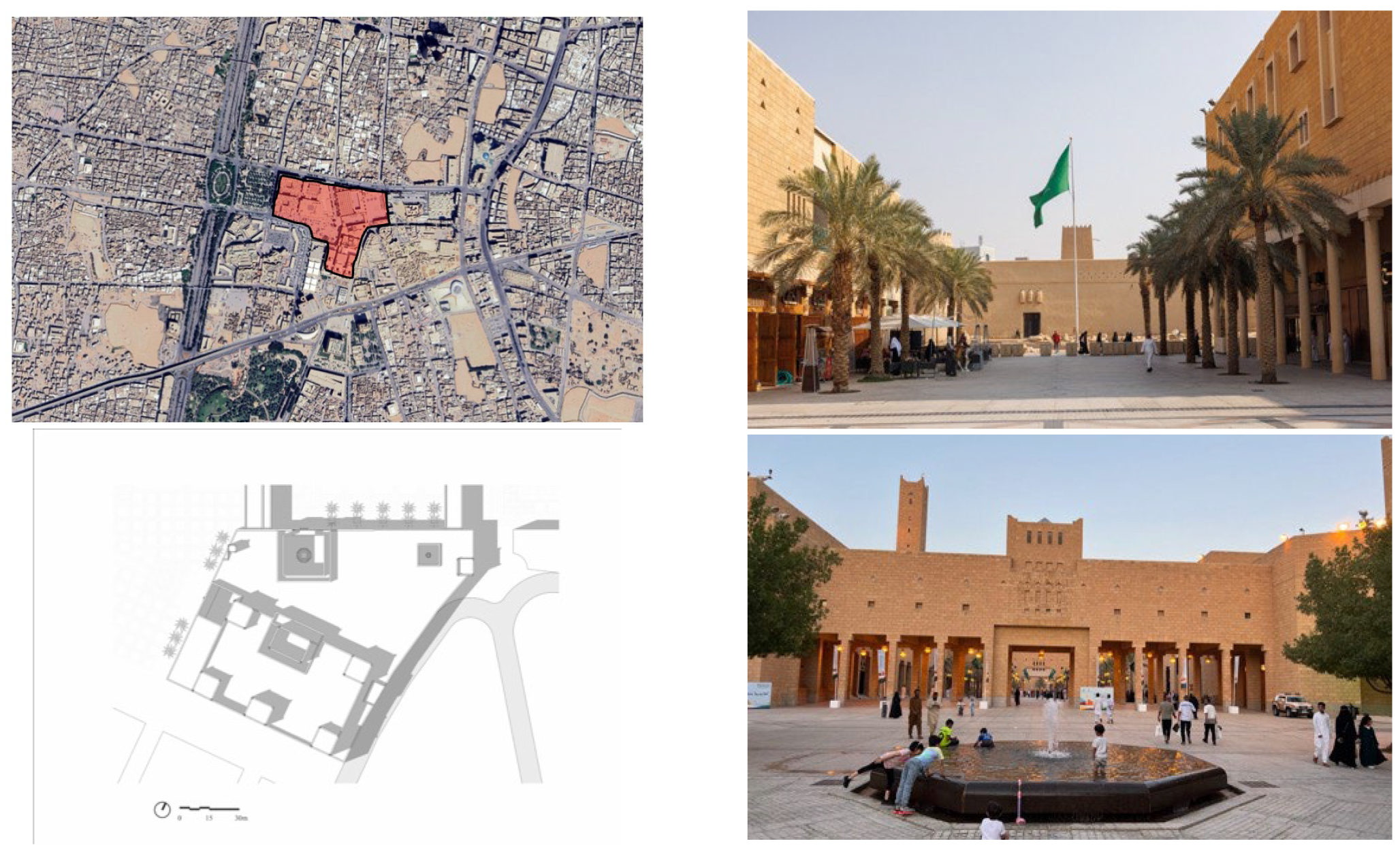

4.1. Diplomatic Quarter (DQ)—Kindy Plaza

The Diplomatic Quarter (Al Safarat), completed in 1986, emerged as a deliberate departure from Riyadh’s car-centric urban expansion, prioritizing pedestrian accessibility and landscape-integrated design at a district scale. Unlike the fragmented modernist planning common in Gulf cities, its masterplan wove together residential, administrative, and civic functions into a cohesive urban fabric [

64].

At its heart, Kindy Plaza reinterprets Najdi urban traditions through a contemporary diplomatic lens. The rectangular plaza, enclosed on three sides by arcaded façades, integrates palm clusters, water features, and shaded platforms to create a layered microclimate. This synthesis of traditional spatial rhythms and modern environmental adaptation (

Figure 3) reflects the Quarter’s broader ambition to reconcile regional identity with functional innovation.

Field observations confirmed the plaza’s climate-responsive design as fundamental to its functionality. Shading strategies, including arcades, recessed façades, trellises, and dense tree planting, created usable microclimates, while building height restrictions and earth-toned finishes mitigated solar gain. Traditional elements, such as triangular vents and crenellated rooflines, embedded cultural resonance, aligning with Gulf regionalist discourse.

Pedestrian data revealed consistent use patterns: peak flows (70–90 users/hour) during diplomatic working hours demonstrated its dual role as a circulation hub and a social space, while off-peak occupancy (20–30 users/hour) confirmed its appeal for informal gathering. Movement trajectories consistently favored shaded routes, validating Gehl’s (2011) [

16] principles of climate-informed public space design.

Interviews with planners highlighted the intentional “controlled permeability” of the Quarter—a synthesis of diplomatic accessibility and cultural discretion. Kindy Plaza’s design mediated visibility and access, exemplifying Lefebvre’s concept of negotiated publicness. Archival plans reinforced this ethos, with 30% of the district allocated to landscaped spaces (

Figure 4). The integration of irrigated gardens and xeriscaping advanced ecological moderation through evapotranspiration and shading, pioneering arid-region landscape urbanism.

The Diplomatic Quarter embodied state-led urban diplomacy during Saudi Arabia’s oil-boom modernization. Housing over 100 embassies within a framework of Saudi cultural motifs, it projected national identity while facilitating global engagement. This dual function, as both a diplomatic enclave and a cultural statement, reflects its role in negotiating between modernity and tradition. The empirical findings (observations, pedestrian data, archival records, interviews) are synthesized in

Table 3 to demonstrate its multi-scalar significance as urban design, political project, and socio-spatial experiment.

Kindy Plaza represents a distinctive Saudi approach to district-scale urbanism, successfully negotiating spatial openness within controlled cultural and political parameters. As a diplomatic enclave, it demonstrates how structured public life emerged in Riyadh through the adaptive reuse of Najdi spatial traditions, climate-responsive design, and state-planning ideology (

Figure 5). Its enduring functionality decades after construction confirms its dual significance as both a practical prototype and a cultural manifesto in Saudi urban modernization.

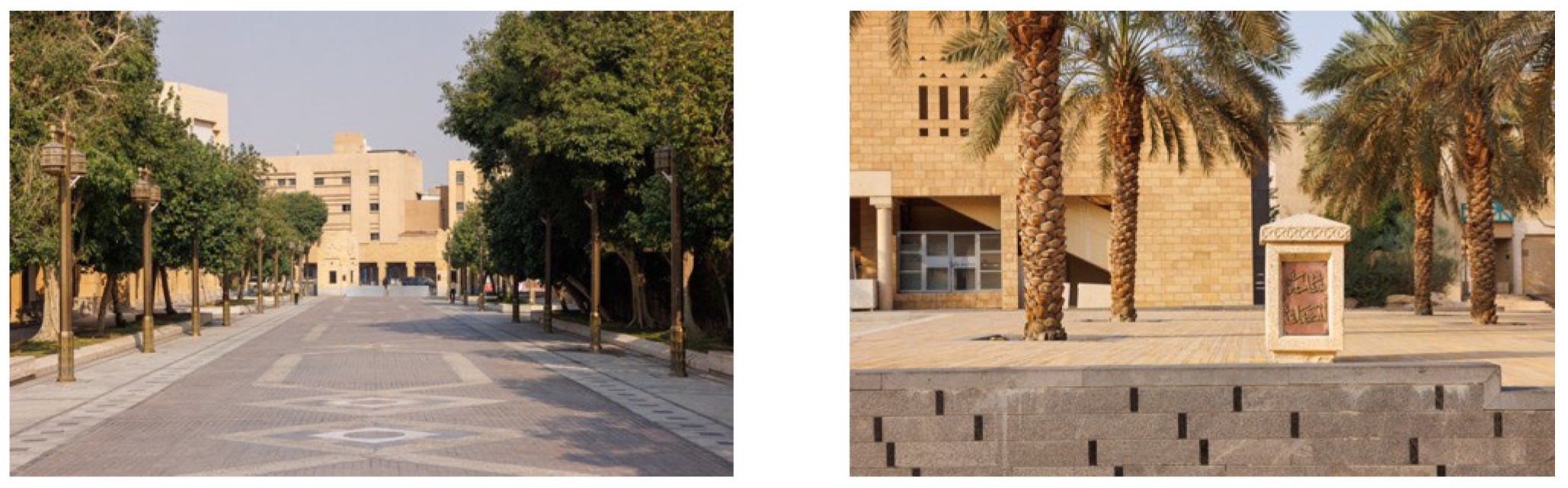

4.2. Qasr Al-Hukm District (QH)

The Qasr Al-Hukm redevelopment (1982–1992) constitutes a defining architectural intervention in Riyadh’s urban history, simultaneously reclaiming the city’s historic center while projecting a vision of culturally grounded modernization. Spearheaded by the Royal Commission for Riyadh City with architect Rasem Badran, the project transformed what had been the city’s traditional political and commercial heart [

65] into a pedestrian-focused urban core that deliberately countered Riyadh’s prevailing patterns of auto-dependent suburban expansion.

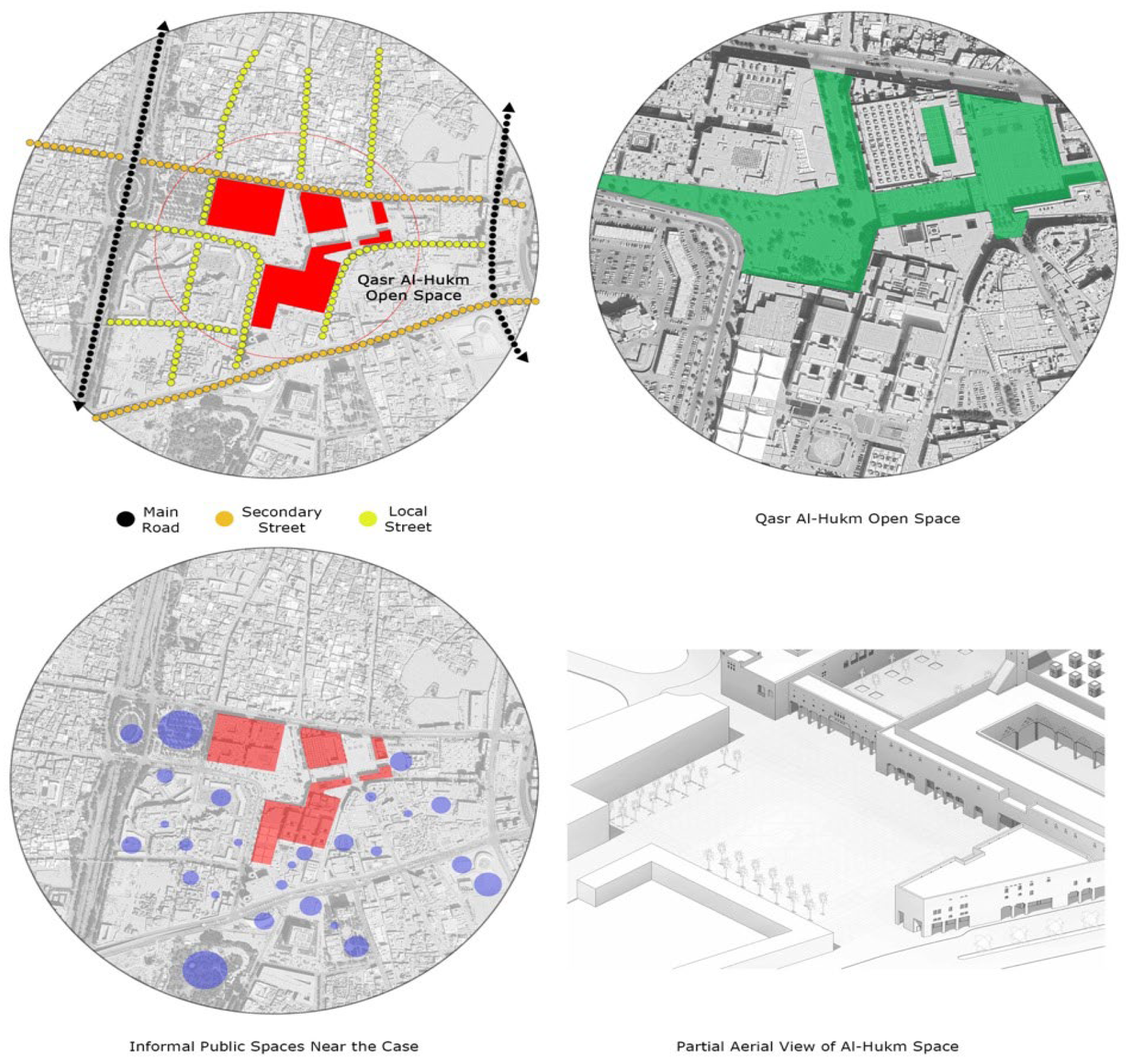

The design consciously revived Najdi urban traditions through narrow shaded passageways, sequenced courtyards, and a network of interconnected public squares, including Al-Safat, Al-Adl, Imam Muhammad Bin Saud, and Al-Masmak. Together, these elements formed Riyadh’s first comprehensive pedestrian realm (

Figure 6), adapting vernacular spatial organization to contemporary civic needs while maintaining essential cultural continuities. The district’s layered spatial hierarchy—modulating between public, semi-public and private domains—represented a significant departure from the city’s prevailing modernist planning paradigms.

Spatial analysis reveals Qasr Al-Hukm as a legible, human-scaled urban center that strikes a balance between administrative density and cultural continuity. The design strategically employs axial alignments framing key historic landmarks, including the Masmak Fortress and Imam Turki Bin Abdullah Grand Mosque, to reinforce historical memory while guiding pedestrian circulation. The squares integrate climatic and social considerations through patterned paving, aligned palm groves, granite seating, and water features, all executed in a restrained architectural language blending semi-solid façades with abstracted Najdi motifs.

Pedestrian data demonstrate robust spatial performance, with peak flows exceeding 150 users/hour during Friday prayers and civic events, stabilizing to 40–60 users/hour for daily use. Unlike newer formal plazas, the district sustains a diverse range of activities—from family gatherings to tourist visits—with movement patterns consistently favoring shaded arcades and walkways. This climate-responsive circulation aligns with Gehl’s principles of how design affordances shape enduring public life.

Interviews with planners and architects underscore the project’s “historically anchored publicness” strategy. Rather than importing foreign models, it reinterpreted pre-modern Riyadh’s organic sociability (

Figure 7), echoing Lefebvre’s conception of space as produced through socio-historical negotiation. The design thus transcends mere monument preservation, instead reviving participatory spatial logics within a modernized framework.

The district’s environmental design demonstrates sophisticated climatic adaptation, employing shaded courtyards, recessed façades, palm groves, and water features to mitigate the extreme heat of Riyadh. Vernacular strategies, including Riyadh stone masonry, thermal mass walls, and wind-channeling narrow passages, create measurable microclimatic improvements, anticipating contemporary sustainability principles through traditional means.

Politically, the project embodies state urbanism through its centralized spatial organization. The deliberate clustering of judicial, religious, and administrative institutions around pedestrian plazas reflects Saudi Arabia’s governance model, while elevated walkways connecting palace and mosque visually reinforce the monarchy’s symbolic relationship with religious authority. This configuration translates political structure into urban form, making power relations spatially legible.

Key empirical findings from site observations, environmental analysis, and institutional studies are systematized in

Table 4, demonstrating how Qasr Al-Hukm negotiates between:

Climatic responsiveness and urban density;

Cultural preservation and modernization;

Political representation and public accessibility.

The project ultimately establishes an urban prototype where environmental intelligence, historical consciousness, and state ideology converge to form an architecturally mediated public realm.

Qasr Al-Hukm endures as a paradigm of culturally grounded urbanism, demonstrating how historic spatial DNA can be adapted to contemporary needs without compromising cultural authenticity. In contrast to Riyadh’s prevailing megaproject urbanism, the district achieves a rare synthesis of three critical dimensions: architectural heritage conservation, environmental intelligence, and urban governance. Its continued vitality decades after completion confirms the value of this integrated approach (

Figure 8).

The project’s success lies in its capacity to simultaneously function as:

A living archive of Najdi urban traditions;

A climate-responsive pedestrian oasis;

A spatial manifestation of Saudi urban polity.

This tripartite model offers critical lessons for Saudi Arabia’s current urban challenges, particularly in reconciling rapid modernization with cultural continuity. Qasr Al-Hukm demonstrates that authentic urban transformation arises not from imported paradigms, but from the thoughtful recalibration of indigenous spatial knowledge to meet present-day requirements. Its enduring relevance underscores the importance of culturally literate urban design in an era of globalized architectural production.

4.3. Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs and Housing (MoMRAH)

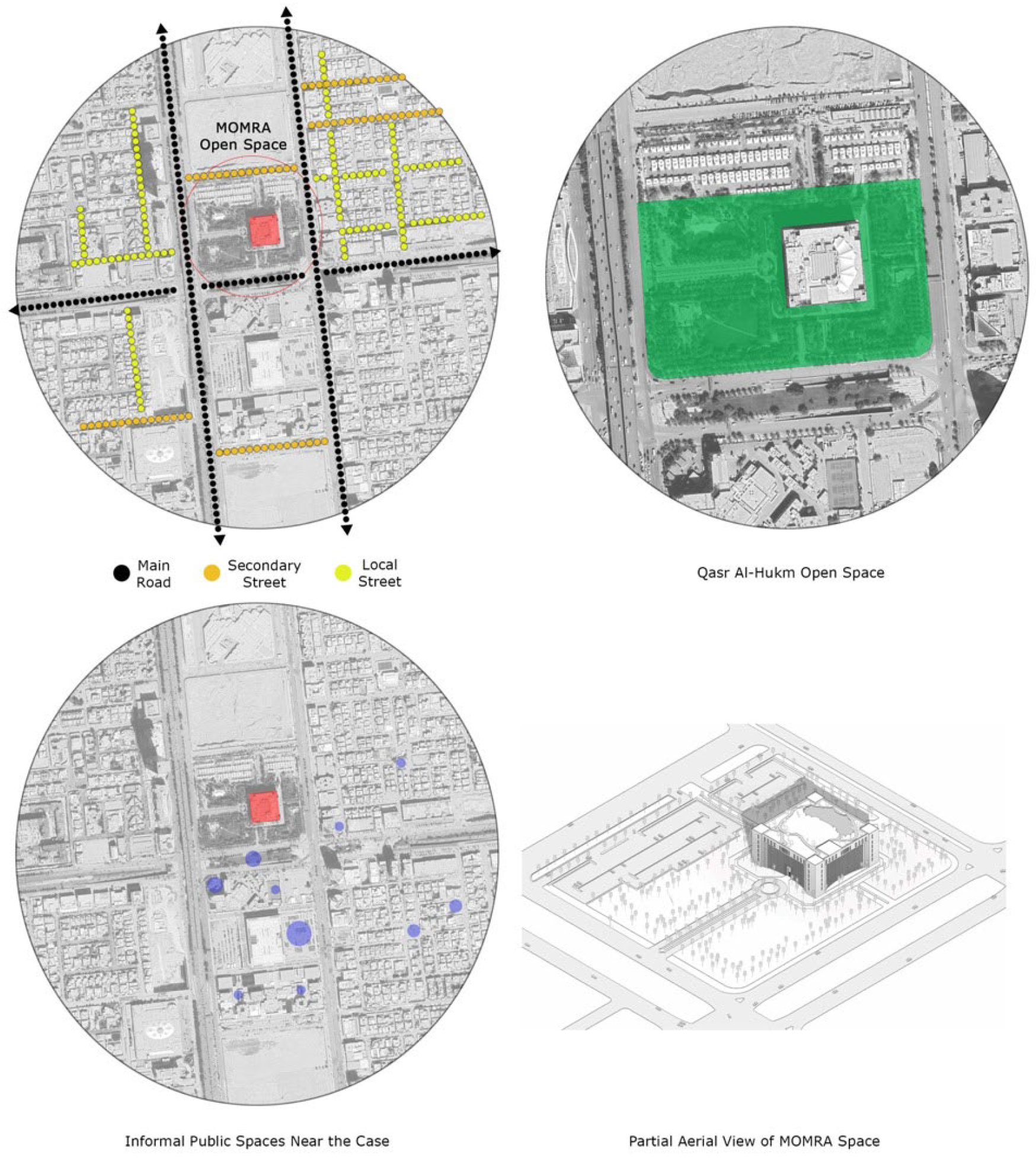

The MoMRAH headquarters (1994), designed by Zuhair Fayez Partnership with BW+P ABROAD, marks a significant evolution in Riyadh’s governmental architecture during the city’s northern expansion. Situated at the intersection of King Fahd Road, King Abdullah Road, and Al-Olaya Street, it reflects both urban centrality and the emerging clustering of ministerial buildings along the capital’s northern growth corridor. The complex breaks from traditional introverted government architecture through its deliberate engagement with the urban context via landscaped transitional spaces.

The architectural solution centers on a precisely proportioned cubic volume measuring 80 by 80 m, organized around a full-height central atrium across seven levels, totaling approximately 50,000 square meters of built space (

Figure 9). The design achieves a sophisticated synthesis of modernist principles and regional identity through multiple strategies: the use of Riyadh limestone cladding provides material continuity with the local context. At the same time, abstracted reinterpretations of Najdi gateway motifs in the projecting entrance volumes negotiate between tradition and innovation. The composition further balances transparency and solidity through its exposed structural framework and judicious use of glazing, exemplifying a mature phase of Gulf regionalist architecture that prioritizes spatial and material authenticity over stylistic revivalism. This approach successfully mediates between contemporary institutional functionality and cultural resonance, establishing an important precedent for subsequent governmental architecture in Riyadh.

The building’s central atrium exemplifies its innovative environmental strategy, employing a steel space-frame to optimize natural light while mitigating solar heat gain. Spanning all floors, this void space serves as both an organizational core and a passive climate moderator, with interior fountains enhancing thermal comfort and cultural resonance through subtle references to traditional Najdi courtyards.

The complex’s perimeter landscape marks a significant evolution in governmental architecture, transitioning from a secured buffer to an accessible public space. Recent pedestrian data revealed consistent use patterns (40–60 users/hour), with activity concentrating along shaded pathways and waterside seating areas. This emergent semi-public realm demonstrates how design affordances can cultivate social use even in institutional contexts, aligning with Gehl’s principles of public life.

Interviews with designers reveal intentional mediation between competing demands. The cubic massing and limestone cladding convey a sense of governmental authority, while the permeable edges and central atrium introduce a sense of accessibility. This nuanced approach embodies Lefebvre’s theory of space as social negotiation, where architecture reconciles institutional presence with evolving expectations of urban civility (

Figure 10). The project thus represents a mature synthesis of environmental intelligence, cultural identity, and social awareness in Saudi institutional design.

The complex pioneered integrated sustainability strategies in Saudi institutional architecture, employing vegetation networks, water features, and rooftop gardens as active thermal regulators. These passive systems, implemented before contemporary green building standards, demonstrate climate-responsive design principles tailored to arid environments, anticipating current approaches to water-sensitive urbanism and microclimatic management.

As headquarters of Saudi Arabia’s urban planning authority, the building embodies a dual institutional identity. Its architecture simultaneously represents centralized governance while signaling a shift toward more accessible public institutions. This duality reflects the nation’s evolving urban paradigm that seeks to reconcile administrative efficiency with emerging priorities of civic engagement and cultural continuity, as systematically analyzed in

Table 5. The project thus serves as both an operational facility and an architectural manifesto for Saudi Arabia’s urban transition.

The Ministry of Municipal, Rural Affairs, and Housing complex thus represents a significant turning point in Riyadh’s architectural and urban development trajectory. It embodies a hybrid institutional model where cultural referencing, environmental pragmatism, and evolving notions of public interface converge within an adaptive and enduring governmental framework (

Figure 11). As Riyadh continues to pursue more comprehensive urban reforms under national vision strategies, this project remains a valuable reference point for balancing administrative function with the imperatives of cultural continuity and urban livability.

5. Findings and Discussion

Viewed collectively, these interventions delineate Riyadh’s evolving network of public-scapes of controlled openness, in which architecture operates as a mediating field connecting environmental pragmatism, cultural representation, and civic accessibility. Taken together, these configurations constitute a series of transforming-scapes, hybrid spatial formations in which publicness is continuously renegotiated through climatic, cultural, and institutional mediations. Within these transforming-scapes, the city’s architectural agency becomes a dynamic process of translation, adapting inherited spatial codes to new social and political realities. This framing highlights how the city’s transformation was not the result of isolated buildings, but rather the cumulative emergence of interlinked spatial terrains that negotiated between tradition, modernization, and state-led urban identity.

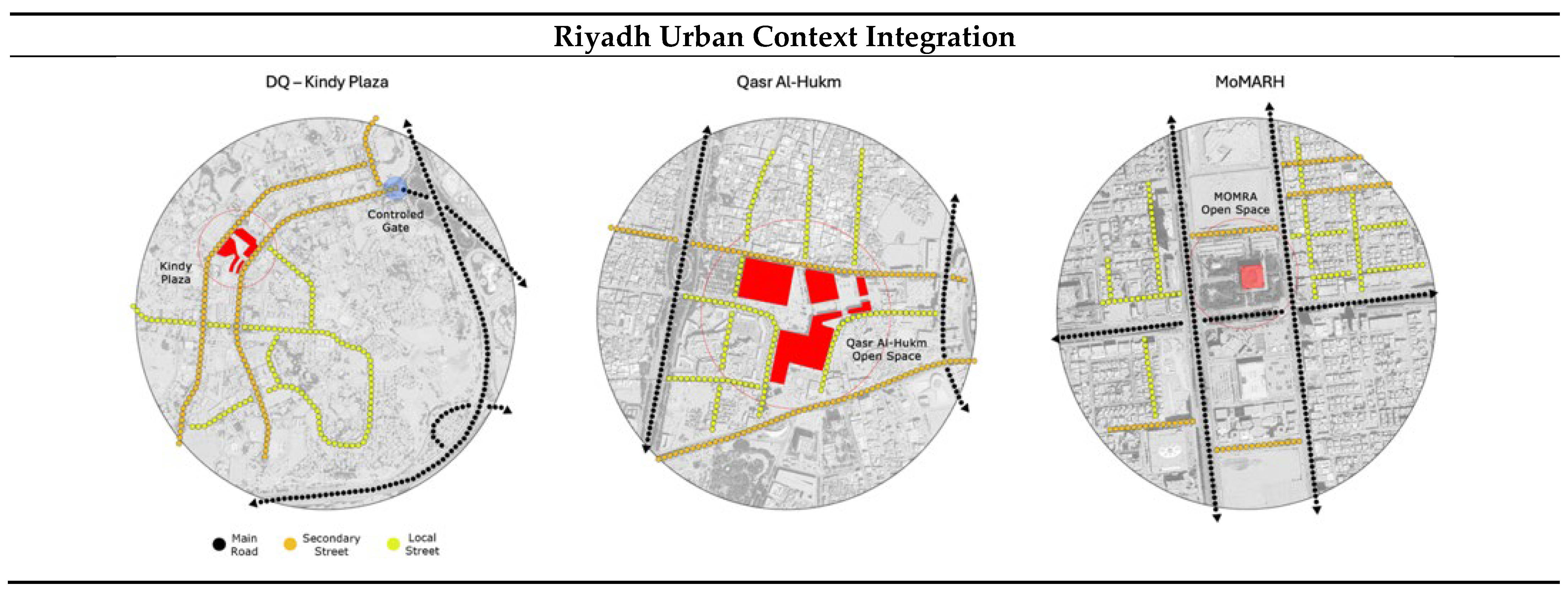

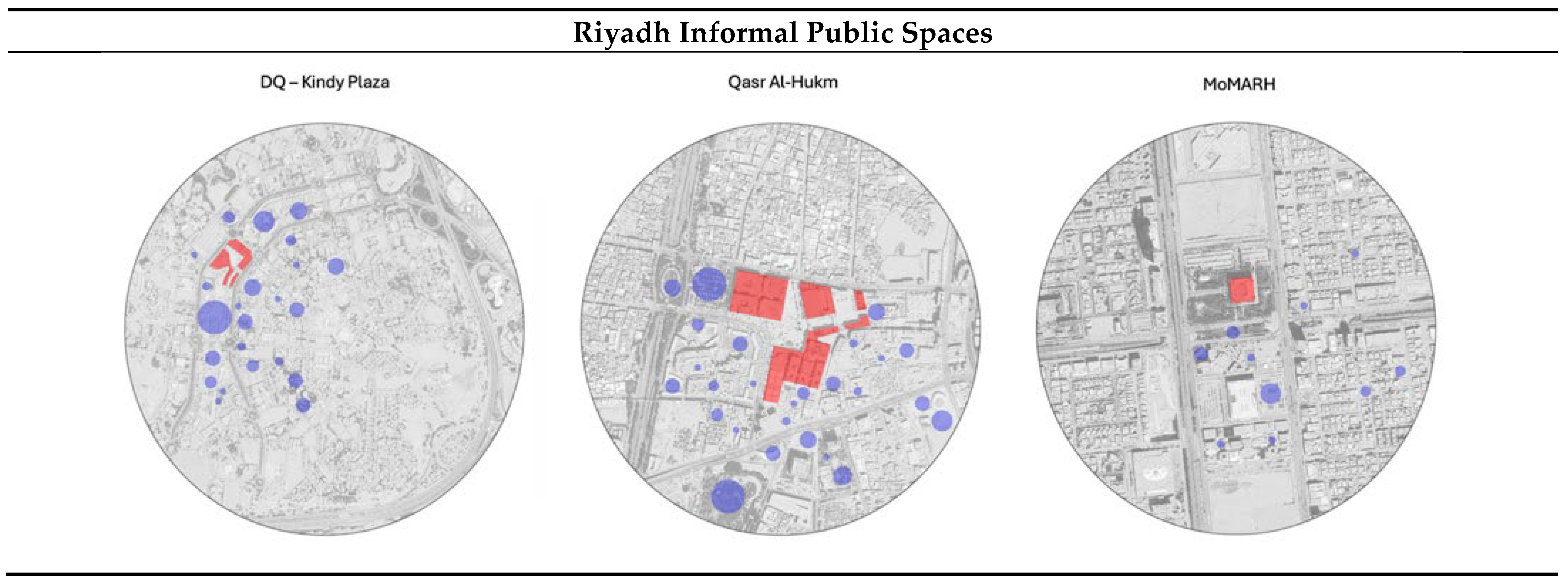

Riyadh’s architectural transformation during the 1980s–1990s witnessed a strategic integration of open spaces through three seminal projects: Kindy Plaza in the Diplomatic Quarter, Qasr Al-Hukm District, and the MoMRAH complex (

Figure 12). Comparative analysis reveals how these interventions collectively reshaped the urban experience through culturally grounded publicness, climate-responsive design, and innovative institutional-civic interfaces. The findings demonstrate architecture’s capacity to mediate between modernization imperatives and cultural continuity during a critical period of urban transition, establishing new paradigms for public space in the Saudi context.

The three case studies demonstrate varying degrees of urban connectivity and public engagement through their distinct spatial configurations. Kindy Plaza in the Diplomatic Quarter establishes a carefully controlled environment through its nested street network, creating security while limiting spontaneous interaction. This reflects the Quarter’s intentional design as an inward-focused enclave, where managed accessibility shapes social dynamics, as confirmed by interviews with planners from the Riyadh Development Authority. The MoMRAH complex presents a different approach through its symmetrical block formation and internal courtyard organization. While its perimeter landscaping and shaded walkways suggest openness, field observations reveal how the design maintains limited urban permeability, creating an impressive yet disconnected monumental presence within the city.

In contrast, Qasr Al-Hukm District achieves deeper urban integration through its embedded position within Riyadh’s historic core. Its network of secondary streets and multiple public squares generates organic pedestrian flows between traditional suqs, mosques, and civic buildings. This spatial configuration has proven particularly effective in reactivating the historic district’s socio-cultural vibrancy during Riyadh’s rapid modernization. The comparative analysis reveals how architectural approaches to public space in conservative urban contexts must negotiate between security, monumentality, and authentic urban engagement (

Figure 13). Successful cases demonstrate that meaningful publicness emerges through culturally graded accessibility rather than absolute openness.

These findings challenge conventional public space metrics by demonstrating how Riyadh’s architectural experiments of the 1980s and 1990s developed alternative models of urban connectivity. The cases collectively illustrate how spatial configurations mediate between urban form and social practice during periods of rapid modernization, with their varying approaches to permeability and access continuing to inform contemporary debates about public space in transforming cities. The Diplomatic Quarter’s controlled environment, MoMRAH’s monumental introversion, and Qasr Al-Hukm’s contextual integration each represent distinct philosophical approaches to balancing cultural norms with urban vitality.

The formal organization of open spaces across the three cases reveals critical relationships between spatial typology and public life (

Figure 14). Kindy Plaza’s geometric plazas and shaded corridors demonstrate thoughtful climate adaptation; however, field observations and architect interviews suggest that their social potential remained partially unrealized. As one landscape architect noted, the visionary forms lacked complementary programming to guide diverse public use beyond official functions.

MoMRAH’s gardens employ an evocative neo-oasis typology, featuring date palm clusters and axial water features that recall Islamic spatial traditions. However, security protocols and contextual isolation limited their public vitality, resulting in lower usage frequency and diversity compared to their design potential. This disconnection between formal ambition and social reality underscores the challenges of creating meaningful public space within institutional compounds.

Qasr Al-Hukm’s network of plazas—particularly Al-Safat, Al-Adl, and Imam Muhammad bin Saud Squares—demonstrates strong public engagement through intentional civic design. Spatial sequencing, elevation shifts, and shaded arcades support both movement and gathering, attracting a diverse mix of users. Al-Safat’s revival symbolized not only physical renewal but also the return of public life to Riyadh’s historic core. The case illustrates that genuine publicness emerges when spatial form aligns with cultural practices, not just esthetic or climatic goals.

Compared to global models like Barcelona’s Plaça Reial or Singapore’s Civic District, Riyadh’s interventions reveal a negotiation between monumentality and controlled access. While all three local projects reflected post-oil architectural ambitions, only Qasr Al-Hukm achieved lasting vitality through integration with a walkable, culturally rich context. Its design embodies Gehl’s “inviting urbanity”, unlike the more representational approaches of Kindy Plaza and MoMRAH.

These insights reinforce relational urbanism: public spaces must function within broader socio-spatial networks. Qasr Al-Hukm’s success lies in its embeddedness and adaptability, contrasting with MoMRAH’s isolation despite formal prominence. The comparison underscores the importance of creating legible, accessible, and programmatically rich spaces to encourage sustained public use.

These findings position Riyadh’s 1980s–1990s architectural experiments within broader global debates on the social production of public space. The adaptive, culturally grounded strategies observed here both parallel and challenge established frameworks developed by scholars such as Gehl (2011) [

16], Carmona (2021) [

12], and Low (2016) [

65]. While Gehl’s emphasis on human-scale interaction and sensory experience offers a universal metric for public life, Riyadh’s experience reveals how such interactions must be recalibrated through climatic and cultural filters. Similarly, Carmona’s multidimensional understanding of public space—linking design, management, and use—finds resonance in Saudi institutional projects where governance and design are inseparable. Low’s anthropological lens on spatial and cultural negotiation further enriches this discussion, demonstrating that in Arab cities, publicness is co-produced through architectural thresholds and social codes rather than open accessibility. Collectively, these correspondences demonstrate that theories emerging from Western urbanism can be critically expanded through cases like Riyadh, highlighting architecture’s role in translating global frameworks into contextually situated practices of public life (

Table 6).

Collectively, these projects redefined Riyadh’s approach to civic space. Where open public environments were once absent, they introduced spatial models grounded in cultural and climatic specificity. While Kindy Plaza emphasized pedestrian formalism and MoMRAH symbolized institutional openness, Qasr Al-Hukm most effectively reactivated urban life through heritage-sensitive design. Together, they shaped a foundational shift in Riyadh’s urban identity and design ethos.

The studied interventions fundamentally altered Riyadh’s socio-spatial dynamics, gradually transforming the residents’ relationship with their urban environment. These plazas, promenades, and gardens introduced new possibilities for informal interaction and cultural expression, challenging the city’s reputation as a strictly functional capital. Through interviews and observations, it became evident that these spaces did more than facilitate movement—they reshaped mental maps of public possibility, embedding the concept of civic space into the city’s collective consciousness. This cultural shift laid the important foundation for subsequent initiatives, such as the King Abdulaziz Historical Center and the Riyadh Art program, with Qasr Al-Hukm particularly emerging as a benchmark for contextual urbanism in later developments.

The study makes three key theoretical contributions to understanding the production of public space. First, it extends Lefebvre’s framework by demonstrating how architectural form mediates spatial production in contexts shaped by both state ideologies and cultural and religious norms. Second, it challenges Western-centric public space models by validating “controlled permeability” and “hybrid typologies” as culturally attuned alternatives to plaza-based spontaneity (

Figure 15). Third, it advances relational urbanism theory by showing how openness operates as a dynamic condition negotiated through design typologies, programming strategies, and evolving user behaviors rather than as a fixed physical property. These insights offer a transferable framework for analyzing urban transformation in Gulf cities, Islamic contexts, and semi-authoritarian settings, navigating similar tensions between modernization and cultural continuity. The research ultimately reveals how seemingly modest architectural interventions can cumulatively reshape a city’s spatial imagination while maintaining cultural authenticity.

6. Conclusions

The comparative findings from Kindy Plaza, Qasr Al-Hukm District, and the Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs & Housing demonstrate that Riyadh’s approach to public space has evolved over two decades in terms of scale, accessibility, cultural responsiveness, and spatial behavior. To support this evolution in future development, the following matrix summarizes key recommendations from the study. The matrix categorizes recommendations across three thematic domains, “Urban Design Practice, Policy Development, and Future Research”, and aligns them with the core issues observed during site analyses and interviews (

Table 7).

From a theoretical perspective,

Figure 7 articulates how Riyadh’s “public-scapes of controlled openness” evolve through three complementary layers: (1) spatial practice, where permeability and contextual integration enhance everyday accessibility; (2) representational form, where cultural references and material continuity reinforce civic identity; and (3) institutional governance, where shared stewardship translates design intent into lived urban experience. Seen together, these layers transform the recommendations from applied design guidelines into a transferable framework for understanding how architecture mediates public life in culturally conservative yet rapidly modernizing contexts.

This study, then, highlights how architectural interventions integrating public-space elements reshaped Riyadh’s urban fabric in the 1980s–1990s, setting new precedents for public life in a car-centric, conservative, and arid context. A comparative analysis of three key projects revealed that successful public spaces emerge from a balance of cultural memory, climatic responsiveness, and urban connectivity. Qasr Al-Hukm stands out for its contextual integration, while Kindy Plaza and MoMRAH demonstrate the limitations of over-control or isolation. It underscores that culturally grounded, socially embedded design, rather than imported models, drives enduring publicness. It advances a relational understanding of urbanism, framing public space as a negotiated condition shaped by design, governance, and user engagement. These insights offer a framework for cities facing similar tensions between modernization and identity, and remain especially relevant as Riyadh advances its Vision 2030 goals.

Beyond the Saudi context, these insights extend to cities confronting similar tensions between modernization, identity, and environmental constraint. By synthesizing these observations, the study contributes to the global discourse by extending the applicability of established theories of public space to non-Western environments. Riyadh’s 1980s–1990s transformation exemplifies how Gehl’s human-centered design principles, Carmona’s relational urbanism, and Low’s socio-anthropological perspective converge in a context of negotiated modernity. The city’s public-scapes illustrate that when these global frameworks are localized, they reveal new dimensions of civic adaptation, where environmental pragmatism and cultural continuity redefine the meaning of public space. Riyadh’s experience illustrates how architecture can operate as a diplomatic interface between tradition and global modernity, offering strategies for negotiating openness through culturally specific spatial hierarchies and climate-responsive design. In this sense, the city’s late-twentieth-century transformation may be read as the emergence of adaptive governance-scapes, where spatial regulation and civic life intersect within broader global urban processes.

At an international level, these cases extend theoretical debates on architectural agency and relational urbanism by demonstrating that the negotiation of openness is not a peripheral or regional phenomenon, but a universal design condition shaped by governance, culture, and environment. Riyadh’s experience underscores architecture’s potential to serve as a diplomatic interface between local identity and global modernity, offering transferable strategies for other cities confronting similar pressures, including environmental constraints and socio-political regulations. Viewed through this lens, Riyadh’s late-twentieth-century experiments also foreshadow the emergence of governance-scapes. In these spatial regimes, design, regulation, and civic life intersect to produce culturally specific forms of managed publicness. These governance-scapes suggest a broader Global South condition in which architecture becomes a mediating instrument of negotiation between state modernization agendas and collective spatial experiences.

Finally, future research might explore how the principles identified here, layered permeability, culturally informed spatial hierarchies, and climate-responsive mediation, can inform comparative frameworks for studying emergent public-scapes across the Global South. In doing so, the study repositions Riyadh not as an exceptional case but as a critical node within a larger global conversation on the architecture of negotiated public life.