2. Singapore Context

Singapore reported its first case of COVID-19 in January 2020. In February, the Disease Outbreak Response System Condition (DORSCON) level was raised from Yellow to Orange, signalling growing concerns over local transmission. By April, as community infections surged, the government implemented a nationwide “circuit breaker,” which included the suspension of non-essential services, a transition to home-based learning, and work-from-home directives wherever feasible. Hailed by the World Health Organization as a model of effective pandemic management (Yan et al., 2020) [

3], Singapore’s response was characterised by a multi-pronged strategy that included early and widespread testing, stringent border controls, the deployment of digital contact-tracing technologies, and a comprehensive national vaccination programme.

However, this broader narrative of success obscured a key vulnerability in Singapore’s pandemic response: the treatment and containment of its low-waged migrant worker population, particularly those housed in large-scale dormitories. Despite early warnings from civil society groups and NGOs about the unsanitary and overcrowded living conditions in these dormitories (Han, 2020) [

4], the state was perceived to have failed to address these structural shortcomings in time. The dormitories rapidly became epicentres of infection. While community case numbers declined during the circuit breaker period, infections among dormitory-based workers surged, leading to a bifurcation of national case reporting between “community” and “migrant worker” cases. Dutta (2021) [

5] argues that the outbreak among migrant workers in dormitories showcased the “failure of Singapore’s public health infrastructure”, especially with regard to how migrants were treated and taken care of (Dutta, 2021) [

5]. Kaur-Gill (2020) [

6], and De Visser & Straughan (2021) [

7] also observed that Singapore’s widely praised pandemic response harboured significant blind spots, particularly in its handling of the migrant worker population. Notably absent throughout was any sustained discourse of rights or entitlements for these workers. Those on work permits, especially in the construction sector, bore the brunt of the pandemic’s disruptions. They experienced social isolation, economic precarity, and a deep sense of disconnection from community life in Singapore and from their families abroad. Their testimonies reveal anxieties about their health, the well-being of their transnational families, and the psychological strain of living in cramped, confined dormitories. Their immobility was compounded by border closures, which rendered them effectively feeling trapped. Between 2019 and 2021, migrant workers made up approximately one-third of Singapore’s total workforce (Ye, 2021) [

8], with over 300,000 residing in purpose-built dormitories segregated from the general population.

This research focuses on the treatment of male migrant workers residing in dormitories, specifically examining how they experienced one of the most prolonged and restrictive lockdown regimes globally during the pandemic. We argue that the physical confinement of migrant workers during the COVID-19 pandemic represents an extension of and intensification of pre-existing state policies and social practices that have long rendered this labouring population structurally marginal and spatially segregated from the mainstream of Singaporean society. These workers, valued primarily for their economic utility yet positioned as socially expendable, were subjected to heightened forms of spatial and bodily regulation under infrastructures of care and control. The restriction of their physical mobility via containment within purpose-built dormitories and restricted access to public spaces was accompanied by a broader apparatus of surveillance, policing, and disciplinary intervention to achieve discipline and biopolitical control. Official justifications for such confinement were framed in biomedical and epidemiological terms, citing public health and safety. However, these measures also entailed the normative disciplining of migrant bodies and behaviours, especially with respect to hygiene, sanitation, and cleanliness. This process was further underpinned by racialised narratives, particularly those focused on male South Asian migrant workers, who became a disproportionately visible and easily governable constituency for health securitisation. They became scapegoats of a pandemic response that concealed latent fears of racialised difference and moral threat. The situation was exacerbated when India’s COVID-19 crisis dominated global headlines, lending credence, however unfounded, to the racial profiling and disciplining of ‘brown bodies’ from South Asia, regardless of their national origin. These racialised anxieties were embedded in normative assumptions about the ‘healthy’, infection-free, and morally upright body cast in contrast to the supposedly disorderly and dangerous migrant subject. The pandemic thus exposed and amplified the existing architecture of exclusion, revealing how public health rationalities can serve to legitimise and extend the reach of state power over precarious migrant populations.

3. Literature Review

Research regarding the migrant worker experience during the pandemic has relatively been well-documented on an international level. The literature has discussed how social isolation arising from government-imposed movement restrictions affects migrant workers adversely. Research has shown that mandatory quarantine in government-designated facilities in India exacerbated migrant workers’ sense of isolation, significantly undermining their mental well-being (Choudhari, 2020) [

9]. The enforcement of strict movement restrictions, often without adequate psychosocial support, was correlated with heightened levels of depression, stress, and anxiety (Saw, Tan, Buvaneswari, Doshi, & Liu, 2021) [

10]. A population survey conducted in Singapore during the COVID-19 outbreak investigated the mental health of international migrant workers and highlighted the impact of restricted access to accurate information (Saw, Tan, Buvaneswari, Doshi, & Liu, 2021) [

10]. The study found that symptoms of depression and stress were closely associated with how migrant workers perceived and assessed the situation, underscoring the role of information access in shaping psychological outcomes. In particular, participants who were more exposed to unverified rumours reported significantly higher levels of anxiety, depression, and stress.

These findings suggest that limited access to official information due in part to movement restrictions and language barriers was a key stressor. The compounded effect of these barriers left many migrants unable to verify or contextualize the circulating misinformation, heightening uncertainty and fear. These mental health symptoms were further exacerbated when workers tested positive for COVID-19, as fears surrounding their physical health were accompanied by anxieties over potential job loss and long-term livelihood insecurity. Dutta (2021) [

5], too, referring to the Singapore situation highlighted how the poor infrastructural conditions of migrant worker dormitories significantly compromised their health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. He argued that the “communication inequality”—by this he meant the lack of access to timely, reliable, and comprehensible official information—was “intrinsically intertwined with the poor health outcomes experienced” by migrant workers (Dutta, 2021) [

5]. His work is particularly valuable in foregrounding the lived experiences of migrant workers by engaging directly with them, thus centering their voices in the narrative of pandemic governance. Through these conversations, Dutta revealed how migrant workers perceived their “everyday lives [as] shaped by the structures of labor exploitation in Singapore,” thereby drawing attention to the structural conditions that rendered them especially vulnerable during the crisis (Dutta, 2021) [

5].

De Jesus et al. (2022) [

11] and Fassin (2020) [

12], writing in the French context, and Sztainbok (2021) [

13], focusing on Canada, offer comparative insights into how state power was exercised over marginalised populations through pandemic-related confinement. Fassin (2020) [

12], for example, identifies the emergence of a moral hierarchy wherein the undocumented are discursively and materially rendered unworthy of protection, exposing the uneven application of state care and surveillance. He notes: ‘These differential policies reveal an implicit moral hierarchy, in which undocumented migrants occupy the lower segment of the social scale, as well as a politics of indifference, which inculcates in them the illegitimacy of their presence and the unworthiness of their lives.’ Sztainbok (2021) [

13], similarly, critiques the biopolitical logic of fragmentation—a system that discerns between the “protected” and the “disposable”—arguing that such logics are both racialised and embedded within global capitalist structures. Her critique of the “carceral character” of pandemic management, particularly her claim that “carcerality signals abandonment,” resonates powerfully with the treatment of many migrant workers globally, where isolation practices were enforced through heavily securitized lockdowns.

This pattern of biopolitical governance is also reflected in scholarship on the Southeast Asian and South Asian contexts. For instance, Yeoh et al. (2023) [

14] and Koh (2020) [

15] have examined how the dormitory confinement of low-wage migrant workers in Singapore during COVID-19 starkly illuminated pre-existing spatial and social segregations, long justified under the guise of efficiency and containment. Koh (2020) [

15] argues that the state’s pandemic response re-entrenched a form of “biosecurity apartheid” that protected the citizenry while subjecting foreign labour to intensified surveillance and confinement. Likewise, Yeoh and colleagues (2023) [

14] note that while the public health rationale for dormitory lockdowns was framed as neutral and necessary, it disproportionately affected low-wage male workers from South Asia who were already structurally excluded from mainstream society. Beyond Southeast Asia, research from the Gulf States (Gardner et al. 2013) [

16] also speaks to similar dynamics, where the kafala system and the spatial organization of migrant housing facilitated swift, large-scale containment, often with little regard for the psychosocial effects on workers. Such practices reflect what Agamben (1998) [

17] calls the “state of exception,” where certain populations are subjected to extraordinary forms of control and stripped of normative legal protections under the pretence of crisis management.

Collectively, the literature points to the ways in which pandemic containment policies, while ostensibly public health driven, served to intensify pre-existing inequalities. The deployment of confinement as a strategy disproportionately impacted those already at the margins—(un)documented migrants, racialized foreign labour, and low-wage workers—whose reduced visibility in public discourse further enabled the normalization of their predicament. In Singapore, this was starkly evidenced by the prolonged dormitory lockdowns and the slow reintegration of migrant workers into public life, practices that cannot be separated from broader moral, racial, and economic hierarchies embedded in the state’s governance of mobility and labour.

Kloppenburg and Peters’ (2012) [

18] concept of a mobility regime offers a valuable lens through which to understand the governance of movement and its entanglement with power. While their analysis centres on the controlled return of Indonesian migrants, we extend their framework to theorise a politics of immobility in Singapore, where migrant workers were subjected to intensified surveillance, restriction, and containment during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is aligned with Dutta’s (2021) [

5] account of communication inequality and infrastructural neglect, both of which exacerbated migrant workers’ health vulnerabilities and exposed the structural violence embedded in Singapore’s labour regime. Building on Dutta’s ethnographically grounded insights, this study explores how the pandemic reshaped migrant workers’ relational, emotional, and spatial worlds both in their communities in Singapore and with families abroad. By centring their voices, we examine the psychosocial toll of isolation, confinement, and systemic segregation, while also tracing the fragile forms of resilience that emerged within these constraints. In doing so, we contribute to broader debates on migrant precarity, surveillance, and the moral economies of care under crisis.

4. Analytical Framing

Singapore’s management of its low-wage migrant workforce reflects a deeply entrenched biopolitical logic rooted in its postcolonial governance framework. Goh (2019) [

19] argues that the city-state’s model of multiracialism, once designed to manage ‘traditional’ diversity comprising mainly the ethnoracial communities of Chinese, Indians, Malays and ‘others’, has come under strain with the increasing influx of low-wage migrant workers. According to him, the 2013 ‘Little India riot’ where the perpetrators were migrants from India served as a catalytic event that accelerated spatial segregation policies, prompting the construction of dedicated dormitories and reinforcing their exclusion from public housing. These measures, justified through racialised discourse and moral panic, were accompanied by community opposition articulated in explicitly “racist terms” (Goh, 2019) [

19], systematically marginalising migrant workers from ‘mainstream’ residential life.

Our analysis of this spatial containment draws on Foucault’s (2003) [

20] concept of biopolitics, where the dormitory does not function as a site of social integration but rather as a mechanism for preserving migrants as an “inexpensive, reserve labour power” (Goh, 2019) [

19]. Their biological existence is instrumentalised; their bodies are rendered valuable only insofar as they fulfil economic functions, stripped of emotional, social, and political recognition (Foucault, 1978; Goh, 2019) [

19,

21]. Even before the onset of the pandemic, there was already a degree of containment in the daily lives of migrant workers, as Ye (2014) [

22] observed in both their living arrangements and their dependence on employers for essentials such as housing, daily meals, transport to and from the worksite, medical coverage, and eventual repatriation. The COVID-19 pandemic intensified this logic of containment where public health measures introduced under the guise of necessity reconstituted the migrant worker as a “medical risk,” rather than a subject vulnerable to infection (Ye, 2021) [

8]. The prolonged lockdown of dormitories, enforced even as Singapore gradually resumed normalcy, manifested what Ye (2021) [

8] terms “inclusive exclusion,” a condition where migrants are essential yet structurally and spatially segregated. The deployment of the military to manage these zones further illustrates the coercive underpinnings of this response.

Techno-political interventions embedded within this response also reflect the uneasy fusion of care and control. Digital surveillance tools such as TraceTogether and FWMOMCare rendered migrant workers “knowable objects,” subject to constant monitoring and ‘datafication’ of their health and movements (Ye, 2021; Joyce et al., 2020) [

8,

23]. These infrastructures enabled not only pandemic management but also entrenched a form of biomedical governance that disciplined the workers through digital means. The outbreak itself revealed structural vulnerabilities long ignored. By early April 2020, migrant dormitories became the epicentre of infection, accounting for 88% of confirmed cases by 6 May (Chew et al., 2020; Koh, 2020) [

15,

24]. In response, the government launched mass testing and spatial redistribution efforts, relocating workers to floating hotels and military facilities (Theng et al., 2020) [

25]. The relocation of high-risk individuals into designated spaces reflected a biopolitical logic treating migrant bodies as instruments in the management of contagion, subject to strategic spatial redistribution (Chew et al., 2020) [

24]. However, these were largely reactive, technocratic measures aimed at infection control rather than structural reform, despite earlier critiques of substandard dormitory conditions (Joyce et al., 2020; Koh, 2020) [

15,

23].

Discursive constructions in media and state narratives further legitimised this exclusionary regime. The pandemic was framed as “two separate infections”—one affecting the general public, the other confined to dormitories (Ye, 2021) [

8]. This binary spatialisation of risk racialised the virus, casting dormitories as unsanitary “hotspots” and reinforcing the image of the migrant body as biologically suspect (Kaur-Gill, 2020) [

6]. Migrant domestic workers were similarly subjected to moral surveillance, with public warnings against social gatherings on rest days further entrenching their marginality (Kaur-Gill, 2020) [

6]. Such narratives served to normalise their exclusion from employment rights and political voice, even as occasional reports disrupted dominant frames by foregrounding poor living conditions or the perspectives and lived experiences of migrants (Kaur-Gill, 2020; Oberai et al., 2024) [

6,

26].

The government’s response unfolded amid what Wickramasekara (2020) [

27] terms a “triple crisis”, one that encompassed health, economic, and migratory dimensions. By the end of 2020, over 54,500 migrant workers had contracted COVID-19, comprising 47% of all dormitory residents (Wickramasekara, 2020; Theng et al., 2020) [

25,

27]. Though treatment was provided without cost and wages were maintained, workers continued to face strict confinement, extensive surveillance, and threats of punishment. Activists likened dormitories to “prisons,” with their carceral design and militarised oversight amplifying existing precarity (Wickramasekara, 2020; Joyce et al., 2020) [

23,

27]. These governance practices exemplify what Joseph (2025) [

28] calls “authoritarian pastoralism,” an adaptation of Foucault’s triangle of sovereignty, discipline, and government to crisis settings. Under this paradigm, the state assumes both the role of carer and enforcer: providing welfare while disciplining populations deemed incapable of self-regulation. Singapore’s pandemic response exemplifies this logic through its dual approach of offering healthcare, food, and wages on one hand, and imposing lockdowns, surveillance, and militarised enforcement on the other. As Ying (2020) [

29] argues, health-promoting infrastructures are neither neutral nor evenly distributed; they operate through racialised, gendered, and normative assumptions about the body and deservingness.

The result is a population rendered docile not through consent, but through the normalization of economic precarity and health securitization. Foucault’s concept of disciplinary power is vividly embodied in the treatment of migrant workers, whose lives were reorganised to conform to a regime of regulation, surveillance, and control (Foucault, 1977) [

30]. Dormitories, gazetted as isolation areas, became tools of biopolitical management where bodies were made legible, traceable, and strategically isolated (Chew et al., 2020; Koh, 2020) [

15,

24]. Through FWMOMCare, self-surveillance became institutionalised, enabling the state to coordinate pandemic response at the population level with minimal disruption to economic productivity (Joyce et al., 2020) [

23].

As the data from our study revealed, this compliance, however, was not the product of internalised discipline alone, but one precipitated by the fear of repatriation, loss of income, or even criminalisation. Economic necessity became a mechanism of social control, making workers more governable through their structural precarity (Oberai et al., 2024) [

26]. In other words, “the migrants themselves enabling and participating in this exploitative process, reproducing certain patterns of subordination and appropriation of their labour” (Ye, 2014, p. 1015) [

22]. Public discourse, too, often reinforced this arrangement by portraying migrant workers as either dangerous or grateful—precarious individuals who required paternalistic management rather than rights (Kaur-Gill, 2020) [

6].

6. The “Underlife” of Migrant Dormitories Under Lockdown

In the case of the migrant workers we interviewed, these tactics took simple but powerful forms: emotional self-regulation; pursuit of hegemonic migrant masculinity and the gendered politics of endurance; maintenance of transnational kinship ties via digital resources; solidarity forged within dormitories; and the use of religious rituals, ‘emotional leakages’, or informal networks to cope with the situation. Such acts were neither spectacular nor confrontational, but they help carve out agentic spaces within a structure designed to render them passive.

The above themes emerged from a qualitative study conducted as part of a larger research project that sought to appreciate and situate the lived experiences of residents and low-wage migrant workers in Singapore (Sinha et al., 2025) [

34], particularly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Fieldwork for the current study began in 2024, shortly after public life had started returning to pre-pandemic rhythms, providing a moment in which research participants could reflect on their experiences during and in the aftermath of the dormitory lockdowns.

A total of sixteen in-depth interviews were conducted with South Asian male migrant workers from India and Bangladesh. Twelve of these interviews took place in purpose-built dormitories, facilitated through the assistance of a key informant. He was a supervisor in charge of the workers residing in the dormitories and was also interviewed. The remaining four interviews were conducted with workers staying in makeshift worksite accommodations. Although living arrangements differed, qualitatively there were no discernible differences in deprivation or restrictions described. All participants were employed in the construction sector. Most were married with young children, typically hailing from extended families where left-behind spouses took responsibility for caring for their parents and children. For participants whose ages were known, these ranged from 24 to the late 40s. They had worked in Singapore for between 5 and 20 years, in some cases uninterrupted. Pseudonyms have been used throughout this study to protect their identities.

In-depth interviews were selected as the primary method because they allow participants to narrate their experiences in their own terms and are particularly valuable for eliciting contextually grounded accounts of life under restrictive conditions (Spradley, 1979; O’Reilly, 2012) [

35,

36], surfacing emotional and moral meanings that cannot be captured through surveys or secondary data. The confidential and dialogic setting helped overcome silences common in group or structured formats, enabling workers to disclose sensitive issues such as fear, stigma, or longing for kin. Beyond eliciting private struggles, interviews also produced “thick description,” situating practices like prayer, routine-making, and small solidarities within the wider social and political economy of migrant labour. Finally, the richness and flexibility of interview narratives provided the kind of inductive material necessary for grounded theory.

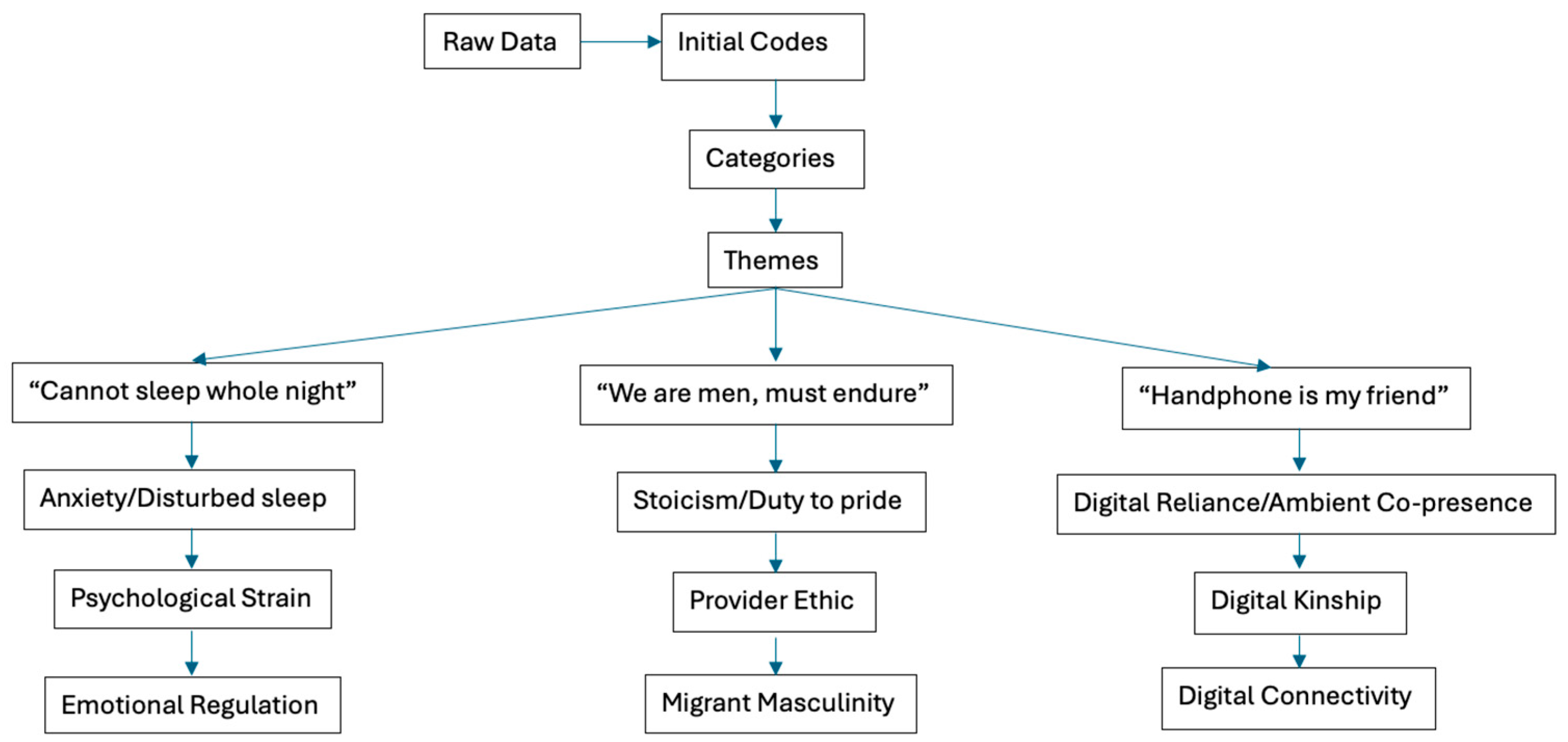

Of the sixteen interviews, eleven were conducted in English and five in Tamil, ensuring that workers could communicate in a language they were comfortable with. Each interview lasted approximately one hour and was audio-recorded with informed consent. Transcripts were prepared in full, and those conducted in Tamil were translated into English for analysis. Data coding and analysis followed a grounded theory approach, with initial open coding used to identify key concepts, followed by axial coding to explore relationships between emerging categories. Themes were then developed inductively, with close attention paid to the institutional contexts within which these narratives were situated.

This research was reviewed and approved by the National University of Singapore’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). Recognising that migrant workers constitute a vulnerable population, safeguards were put in place to minimise risk and ensure ethical integrity. These included: (i) guaranteeing anonymity through pseudonyms and the removal of identifying details; (ii) making clear to participants that their involvement was entirely voluntary and that they could withdraw or stop the interview at any time without any consequences; (iii) obtaining explicit informed consent for audio-recording, with the option to decline; and (iv) conducting interviews in a manner that prioritised participants’ comfort and well-being, avoiding intrusive questioning and respecting silences. We were attentive to the potential power asymmetries in the research encounter, and took care to foreground participants’ autonomy, dignity, and right to control their narratives.

Access to dormitory residents was a significant challenge and impacted our ability to generate data beyond the constraints imposed by various “barriers”. Eight interviews were conducted in public spaces within dormitory premises where the larger dormitory community could observe, and potentially overhear, our interactions. We fully expected workers’ narratives to be constrained under such conditions, and our aim was to query what was sayable within these parameters. As to be expected, participants appeared careful and cautious in framing their responses, reflecting the weight of power imbalances between workers and their employers, dormitory caretakers, and even interviewers (Karnieli-Miller et al., 2009) [

37]. At the same time, they exercised agency in offering nuanced judgements about gaps in care. For example, several noted that while the government had issued clear guidelines about wage protection during the pandemic, some employers failed to translate these into practice, resulting in delayed or partial salary payments.

In addition to constraints of setting, certain methodological limitations must be acknowledged. First, the interviews required participants to recall events that had taken place approximately two years earlier, potentially introducing retrospective bias (Bernard, 2011) [

38]. Second, most participants recounted overwhelmingly positive accounts of government and employer responses to the pandemic, with only two alluding, albeit mildly, to experiences of discrimination or frustration regarding lockdown measures. This likely reflects a degree of social desirability bias, shaped by unequal power relations and the highly visible settings of many of the interviews. However, it would be inaccurate to dismiss such expressions of gratitude as “invalid.” Rather, they should be treated as important social facts in their own right. Many workers did indeed voice appreciation for the provision of medical care, additional mobile data, and wage protection, even as others simultaneously registered confusion, anger, or disappointment at restrictions that applied disproportionately to South Asian migrants. To report such ambivalence is not to endorse prevailing structures of control, but to recognise the complex ways in which migrants negotiated survival and made sense of their experiences.

Third, the willingness of some workers to participate may reflect self-selection bias, with those who coped relatively well during the crisis more inclined to step forward. This may mean that the most distressed voices are underrepresented. Yet, rather than undermining the validity of our findings, these constraints illuminate the dynamics of what is narratable under conditions of surveillance and precarity. As ethnographic traditions remind us, silence, evasion, and restraint are themselves analytically significant. Finally, while it was not feasible to undertake participant observation, documentary analysis, or inter-coder verification given the timing and access restrictions, we sought to enhance rigour through systematic coding, transparency in analytic procedures, and reflexive acknowledgment of positionality. The coding maps and conceptual figures (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) presented below illustrate our effort to render the analytic process as transparent as possible.

Given these issues, this study does not claim to represent the full spectrum of migrant workers’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. We fully acknowledge that many workers may not have coped well and could have experienced profound emotional or psychological distress, which remains underrepresented here. The focus, however, is on those who demonstrated adaptive resilience and survived to narrate their stories. Their accounts provide critical insights into everyday strategies of endurance, adaptation, and meaning-making under conditions of crisis. To foreground resilience is not to romanticize suffering, but to complicate binary framings of workers as either passive victims or heroic resisters, showing instead how agency is exercised in constrained, contingent, and ambivalent ways.

6.1. Emotional Regulation

The majority of migrant workers recollected feelings of confusion, frustration, uncertainty, and fear during the dormitory lockdown, emotions that impacted not only their physical well-being but also their emotional and psychological health. These feelings were linked to specific experiences: a lack of information about the pandemic; being transferred between quarantine facilities without adequate explanation; restricted movement within dormitories; bureaucratic gaze that looms over the worker through labyrinth of surveillance structures; overcrowded living conditions—sometimes with 30 or more workers sharing a single room and hygiene facility which heightened fears of infection; anxiety over potential job loss and the inability to support families back home; a struggle with an ‘inauthentic self,’ in which they felt unable to speak honestly about their situation with colleagues or loved ones; and, most profoundly, the fear of dying in a foreign country. As Kannan, whose wife was expecting their first child, shared:

One person ah, anybody also no talking, only one person, think all crazy things going, mind is, so after I call my wife and my family, no feeling, after nighttime coming automatically sleeping, so sometimes no sleep, full whole night cannot sleep…

Notably, these expressions of distress were shared even as workers consistently voiced appreciation for their employers’ care and the government’s management of the pandemic. This coexistence of gratitude and deep emotional strain reveals the complexity of their lived experience; one marked by both material provision and psychological vulnerability. As Rahim, a Bangladeshi worker, stated: ‘My boss is very good, everything take care of us, no complain.’

His peer, Rahim, echoed:

Government they give t-shirt, fresh everything they give, medicine also they give…I no problem, anything need I call my boss. I need only, room change or anything, then I call MOM (Ministry of Manpower)…

In contrast, the following interlocutor, Vasu, an Indian national who had worked in Singapore for more than a decade, expressed his concerns regarding the differential treatment South Asian migrant workers had to particularly endure:

I felt very sad, angry and confused because many Singapore people and even many workers from Thailand, China and Burma (Myanmar) can go outside but we cannot…not Indian and Bangladeshi workers…till today, I cannot understand why this separation…don’t know why but we all very confused and inside very angry. Can I complain or don’t know if must say thank you to the government for keeping me alive because the government took care of us.

Another interlocutor, Guru, a dormitory supervisor, also expressed frustration and disappointment at the differential treatment of Singaporeans and foreign workers. When asked how he felt that others could move about freely but he could not, he replied plainly: ‘It is like having biryani (a fragrant, spiced rice) in front of you but you are not allowed to eat. Why we cannot eat ?’

Across interviews, emotional self-regulation emerged as a central feature of survival. Participants did not report overt breakdowns but instead invoked narratives of acceptance and suppressed distress. As Bashim, a staunch Muslim, confided:

Sometimes 1 o’clock, 2 o’clock, sleeping no come...Just pray, just sleep. Full day sleep, no go walking.

Never tell them [family] got COVID…were also actually some people are, they don’t care, especially the Kampong (rural) people, they don’t care, They…God…Allah give or maybe something think Allah give me life…HE will take care of me…so I’m not worries about…

This stoic endurance mirrors what Hochschild (1979) [

39] terms as “rules of emotional display”, wherein individuals manage feelings to align with expected norms; in this case, the migrant script of resilience and endurance “that sanctions what feelings should (or should not) be felt or exhibited in certain situations” (Crewe et al., 2014) [

40].

The norm of emotional restraint also had a collective coping function. While emotional ‘leakages’ are accepted as long as they were to take place in ‘private sanctuaries’ (in this case where a worker cried himself to sleep without getting attention from his co-workers), perpetual and open displays of emotions were proscribed, not dissimilar to the case of prisoners (Jewkes, 2005) [

41], for they placed a burden on other workers and because it reminded them of their own vulnerabilities and personal troubles. Thus, emotional regulation revolves around the identity work of ‘masking’ and ‘fronting’ (Crewe et al., 2014) [

40] to cope with pains of the communal lockdown. Again, drawing upon Hochschild (1979, p. 561) [

39], ‘fronting’ is a form of evocation, ‘in which the cognitive focus is on a desired feeling which is initially absent’, while ‘masking’ suggests a form of suppression, ‘in which the cognitive focus is on an undesired feeling which is initially present’. These processes resemble a form of non-reflective cognition that can be understood as a self-protective cognitive flattening, what Victor Turner (1969) [

42] might describe as “liminal detachment”: a strategic suspension of reflection in order to endure moments of crisis.

The following excerpts from our interlocutors’ narratives attests to this performance of masking and fronting:

…I hide it from them [family], they also scared already, I also scared I cannot tahan (cannot tolerate), so I that time, my wife pregnant, so that time I anything no tell her…Ah, I no tension her…Corona coming and then baby coming pressure everything coming, so I anything no talk, I only I am happy and very safe, anything no feeling, so I every time happy when we talk.

…she [wife] call me, video call me, I in hospital sleeping, so how to say? I go and dress changing, after coming, I say I’m in my room inside, like this. Hospital going like this. I go inside toilet, changing dress, after that call…

A number of migrant workers also shared that their experience of the lockdown felt akin to that of a “prisoner,” drawing on circulating cultural imaginaries of incarceration to articulate the sense of confinement, surveillance, and loss of agency, even though they themselves had never been imprisoned. Here is such a sentiment from Muhammad:

Everything also cannot…cannot talk to anyone, must always wear mask stay in the room only. Food come they put outside after knocking, then we take food inside...cannot go outside, MOM people always outside, sometimes got police and military people…everything also must ask permission, that time I go crazy like prisoner…

…we shift, shift, shift…just listen to people, don’t know where they take us one…Then they make sometimes they make us exercise also…

Though the invocation of the imagery of a prisoner was a strong one, the interlocutors were careful not to let that articulation constitute or to be read as an assault on their personal dignity or self-concept; they were quick to reclaim their autonomy and self-respect in ways that did not position them solely as passive victims, but as individuals exercising agency, resilience, and moral worth even within constrained circumstances. Nowhere was this more evident than in their adherence to the script of migrant masculinity, an ethic that foregrounds stoicism and the fulfilment of provider responsibilities as expressions of strength and self-possession. This theme is discussed in the following section.

6.2. Migrant Masculinity and the Gendered Politics of Endurance

We miss family, but we are men, right?

This remark from an interlocutor encapsulates a recurring theme across the interviews: that of migrant masculinity as a framework through which emotional vulnerability is acknowledged, yet immediately subordinated to the imperative of endurance. It is a powerful declaration that gestures toward pain while affirming strength, drawing on a gendered repertoire that privileges stoicism, emotional restraint, and the ability to preserve under pressure. Migrant men repeatedly framed their suffering, whether physical, psychological, or emotional, not as calls for help but as conditions to be endured.

As Jewkes (2005, p. 48) [

41] notes, “all forms of masculinity inevitably involve a certain degree of putting on a “manly front”, and it therefore seems reasonable to consider the outward manifestation of all masculinities as presentation or performance”. Central to this performance, as noted in the narratives of interlocutors, was the ethic of provision. As Mansoor explained: “Money don’t have then that’s why I come here lah.” While Mani exclaimed as a matter of fact, “I have not seen my family for 14 years, I have to send money home.”

Emphasising his duty of care, Mani, the youngest sibling and unmarried, supported his aged parents and four sisters:

It’s sad, but no choice we have to do this also. Because we need to support our family, so that’s why.

The family remained emotionally significant, but its affective needs were subordinated to the economic obligation of remittance. Ye (2014) [

22], in her study of Bangladeshi men in Singapore’s labour force, found that participants’ decisions to work in Singapore were almost always shaped by their roles as men within their households. Even after migrating, masculinity continued to be framed within existing patriarchal structures, where men were expected to fulfil the role of economic providers while women remained responsible for reproductive labour within the household. Emphasising the intersectionality of class and gender, she makes an important assertion that labour migration cannot be solely comprehended in terms of economic rationality as “labour migration and the economic capital they hope to reap from it become a significant part of their identity construction as men” (Ye, 2014, p.1014–1015) [

22]. As Bourdieu (2001, p. 96) [

43] similarly noted:

…social positions themselves (are) sexually characterised and characterizing…in defending their jobs against feminization, men are trying to protect…themselves as men, such as manual workers…which owe much, if not all of their value, even in their (own) eyes, to their image of manliness.

This is consistent with Osella and Osella’s (2000) [

44] work on South Asian migrant masculinities, where being a man is closely tied to fulfilling one’s role as a self-sacrificing breadwinner who absorbs hardship for the sake of familial well-being. Thus, masculine migratory imperative is often situated within pressures to conform to heteropatriarchal “male breadwinner” ideal (Kukreja, 2021) [

45]. South Asian masculinity, at times interacting with rural hegemonic masculinity, “positions South Asian men’s experiences within the intersections of caste ideology, the colonial encounter, religious fundamentalism, and local forms of patriarchy…[where] employment, marriage, and parenthood are cultural entry points into heterosexual masculine sorority while those who are unemployed or unmarried are more likely to be accorded a marginal masculine status” (Kukreja, 202, p. 201–310) [

45].

Undergirding this agency is the ongoing construction of their gender subjectivities, which is always tied to wage labour (Ye, 2014) [

22]. As a result, the gendered divisions of labour not only spatialise men and women differently but also reproduce differentiated notions of morality for men and women. While the migrant men in our study (a subset of the global working class) may occupy subordinated positions within the hierarchies of class and the global capitalist relations of production, they nonetheless retain a measure of power within the gender order. As men, they continue to participate in a system of asymmetrical gender relations in which they are collectively privileged over women, even as they themselves are marginalised in other structural domains. As Messerschmidt (2018, p. 52) [

46] observes, “even men who are subordinated in terms of class or race may still participate in and derive benefits from a gender order that privileges men over women”.

Even in moments of acute vulnerability such as contracting COVID-19 and experiencing the totalising effects of the dormitory lockdown, emotional expression was carefully managed. As Muhammad recounted, “This time my family all cry lah, my wife also cry... I also cry,” but he quickly returned to a discourse of stoic inevitability: “No choice mah.” The tears were real, but they were immediately bracketed by a normative expectation of masculine control. His emotional self-suppression thus becomes a classed strategy of survival, an assertion of agency under conditions where both masculine respectability and economic necessity intersect. It is at this intersection of gender and class that migrant agency is most visible not in defiance of structure, but in the capacity to negotiate it.

6.3. Digital Connectivity as Affective Infrastructure

During the COVID-19 pandemic, physical distancing limited social interaction resulting in feelings of loneliness and social isolation, consequently affecting mental well-being (Buecker & Horstmann, 2022; Kim et al., 2020; Hwang et al., 2020) [

47,

48,

49]. Digital connectivity thus became a central lifeline for communities globally. Lim (2020) [

50] describes this as

distant sociality, where people turned to Zoom, WhatsApp, and social media to sustain emotional ties. For middle-class households with stable internet access, digital life expanded to include livestreamed concerts, virtual religious services, and remote work arrangements (Tay & Pierce, 2021) [

51]. However, for low-wage migrant workers confined in institutional dormitories during the COVID-19 pandemic, digital connectivity assumed a qualitatively distinct significance.

Often housed in crowded dormitories or employer-provided accommodations (in the case of female domestic workers) with limited connectivity and heightened surveillance, migrant workers relied heavily on mobile phones and data access not for leisure, but for survival. In these constrained settings, digital technologies functioned less as tools of convenience and more as affective infrastructures—systems that structure and mediate emotional life and social presence (Parks, 2014; Larkin, 2013) [

52,

53]. As Haja, a relatively recent migrant, recounted, “Everyday two times, sometimes three times I call family…other friends no room inside. The handphone is my friend only”.

As Lin and Ye (2022) [

54] emphasize, for many migrants, mobile phones became critical lifelines, enabling them to share financial updates, offer and receive emotional support, and maintain transnational ties with family members during extended periods of isolation. The multimodal affordances of social media platforms—allowing for text, video, and voice interaction—also played an important role in sustaining emotional well-being and a sense of empowerment, particularly for displaced or isolated populations (Leurs & Patterson, 2020) [

55]. Murugan, a skilled worker entrusted with dormitory management, professed: “That gave me the power to continue,” referring to Tamil films and YouTube.

Referring to this phenomenon as “ambient co-presence,” Madianou (2016, p.183) [

56] describes a form of mediated relationality marked by a heightened yet often peripheral awareness of the everyday lives and emotional states of significant others. Enabled by the technological convergence of mobile and social media, ambient co-presence becomes a vital emotional infrastructure for transnational families, particularly those sustained by low-wage migrant workers. This peripheral connectivity allows for the cultivation of intimacy, reassurance, and a sense of moral proximity across geographical and institutional divides. As Madianou (2016) [

56] observes, ambient co-presence has powerful emotional consequences, shaping how care, responsibility, and belonging are maintained under conditions of enforced separation.

That time, of course, heart pain, very scared. My brother also cry, I also here cry, my father mother also cry, because this situation, this COVID situation, many people died, so only God help you (Bashim).

The following exchange revealed how ‘ambient co-presence’ is performed:

Interviewer: So you said that your wife was pregnant during COVID, so you weren’t there when your child was born?

Interlocutor Kannan: how to go…everything lockdown…I want to go but cannot…my wife very scared …my wife and me got video call and she show video of my twins…I tell my wife we take care of children together…I work Singapore to send money for my children…for my family.

In this context, digital connectivity was not merely an auxiliary means of communication, but a vital infrastructure of care and self-making, wherein digital proximity became the primary mode through which kinship was enacted and sustained (Baldassar, 2008) [

57]. Importantly, digital connectivity also intersected with migrant men’s gendered performances of endurance as they “do family” (Morgan, 1996) [

58] despite having to navigate the pressures of being distant breadwinners. Such usage also illustrates how the digital space served as a balancing mechanism within dominant masculinities that often hinge on the stoic suppression of vulnerability, a point that was discussed earlier.

Across all the interviews, our interlocutors never failed to highlight the key role state and non-governmental actors in Singapore played in shaping these digital ecologies. The workers acknowledged receiving 100 GB of free data, a policy introduced by the government in collaboration with telcos and NGOs during the dormitory lockdown (Chua, 2020) [

59]. This provision of digital infrastructure somewhat accentuated the entanglement of care and control, what Gillespie, Osseiran, and Cheesman (2018) [

60] termed “digital borderlands”, where technology simultaneously offers support while extending the reach of governance. Nonetheless, such provision of digital support helped to mitigate “second-order disasters” (Madianou, 2020) [

61] referring to how digital technologies in such contexts can exacerbate inequalities by becoming both indispensable and unevenly accessible (Robinson et al., 2015) [

62]. Thus, to claim that digital connectivity mattered to everyone during the pandemic is true but insufficient to an extent. What makes the migrant case distinct is the structural dependence on these tools for basic emotional, economic, and relational functioning in the context of protracted immobility, limited autonomy, and institutional lockdown. Digital connectivity was a survival infrastructure, an assemblage of emotional scaffolding, care-at-a-distance, practical coordination, and gendered self-making.

The interview data also surfaced themes of solidarity, routinisation, and religious coping, though these tended to be related to the broader dominant themes of emotional regulation, migrant masculinity, and digital connectivity as affective infrastructure as discussed earlier. Due to space constraints, these themes could not be explored in-depth.

7. Discussion: Rethinking Biopolitics, Agency, and the Working-Class Migrant

The governance of Singapore’s low-wage migrant workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic can be discursively read through a Foucauldian lens. Many scholars have drawn on Foucault’s concepts of biopolitics, disciplinary power, and governmentality to illuminate how migrant bodies are rendered knowable, manageable, and exploitable through regimes of surveillance, spatial containment, and biomedical control (Foucault, 1977, 1978, 2003; Ye, 2021) [

8,

20,

21,

30]. Yet while the Foucauldian frame remains generative for unpacking the technologies of power that shaped the pandemic response, it risks portraying migrant workers as wholly docile subjects.

Our data complicate this determinism. As Goffman’s (1961) [

31] work on “free places” in total institutions reminds us, even under highly regulated conditions, spaces exist for adaptation, privacy, and the subversion of rules. For the migrant workers in our study, such tactics ranged from emotional regulation, performing masculinity, and “doing family” to structuring daily routines and religious practices that preserved dignity and emotional coherence amid lockdown. This focus on agency is not intended to minimise the structural realities of their subordination, but rather to foreground how working-class subjects salvage a measure of self-determination even in the face of restrictive governance. At the same time, this agency should not be conflated with James Scott’s (1985; 1989) [

63,

64] notion of everyday resistance, which describes how subordinated groups covertly undermine domination through small acts of sabotage or disobedience.

Our data did not indicate that the workers engaged in covert defiance such as foot-dragging, pilfering, or sabotage but instead turned to prayers, routines, small solidarities, and phone calls to kin as ways of sustaining themselves. These practices were not oriented toward undermining authority but toward enduring it. They preserved sanity and dignity within the boundaries imposed, rather than destabilising the system that constrained them. This distinction is crucial, for resistance, in Scott’s view, is always oppositional, aimed at pushing back against domination whether openly or covertly. Adaptive agency, by contrast, is the capacity to act meaningfully within constraints, sustaining selfhood even when open confrontation is neither possible nor intended.

The distinction is therefore conceptual as well as empirical. Resistance is oppositional and carries an implicit political charge, however muted. Adaptive agency is not about opposition but about survival; it is a politics of endurance rather than disruption. To conflate the two risks over-politicizing practices that are fundamentally about maintaining life in precarious conditions. At the same time, recognizing adaptive agency does not diminish its significance. It reminds us that the capacity to act is not exhausted by resistance: it also includes the ability to cultivate meaning, manage emotions, and sustain relational worlds under domination.

A key to understanding these dynamic lies in what has come to be termed “authoritarian pastoralism”, a governance logic that fuses coercion with care. Drawing on Foucault’s (2009) [

65] concept of pastoral power, the state assumed the role of both carer and disciplinarian: providing healthcare, wages, and food, while simultaneously enforcing confinement, surveillance, and militarised oversight.

This care–control nexus was visible in the Singapore state’s response to the pandemic. Publicly, the provision of welfare was framed as benevolent protection where restrictions were legitimised as acts of safeguarding. Privately, however, workers navigated these constraints through quiet acts of resilience and adaptation. From a critical theory perspective, the provision of care was also functional to the reproduction of labour power. The minimal social wage as seen in the form of medical care, food, and accommodation ensured workers’ physical and emotional capacity to return to work, while reinforcing their dependence on wage labour and limiting the likelihood of overt defiance.

The pandemic thus revealed not only the durability of Singapore’s migrant labour regime but also the mechanisms through which subordination is reproduced in a climate of crisis. Care was not the antithesis of control, but its necessary complement. It presented an ambivalent mode of governance that preserved both the productivity and governability of the workforce. Recognising this grey zone between coercion and compassion complicates linear readings of docility, highlighting instead a political economy in which the very gestures that appear to value workers’ lives also secure their continued economic exploitation.