Bridging Perceptions: A Comparative Evaluation of Public Space Design Qualities by Experts and Users

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Literature Review on Designing Successful Public Squares

- Inclusiveness: Design and management of public squares to meet diverse needs, with particular attention to vulnerable populations.

- Accessibility and connectivity: Physical and social accessibility ensure the participation in public life.

- Sociability: The capacity of a space to foster interactions, strengthen social ties, and promote diversity.

- Vitality: The ability of a place to sustain diverse activities and maintain constant activity levels.

- Perceptual and esthetic satisfaction: The sensory and symbolic qualities that enhance user experience and attachment.

- Community engagement: Citizens’ involvement in shaping public squares to ensure legitimacy, sustainability, and long-term use.

2.2. Analysis of Qualities and Variables

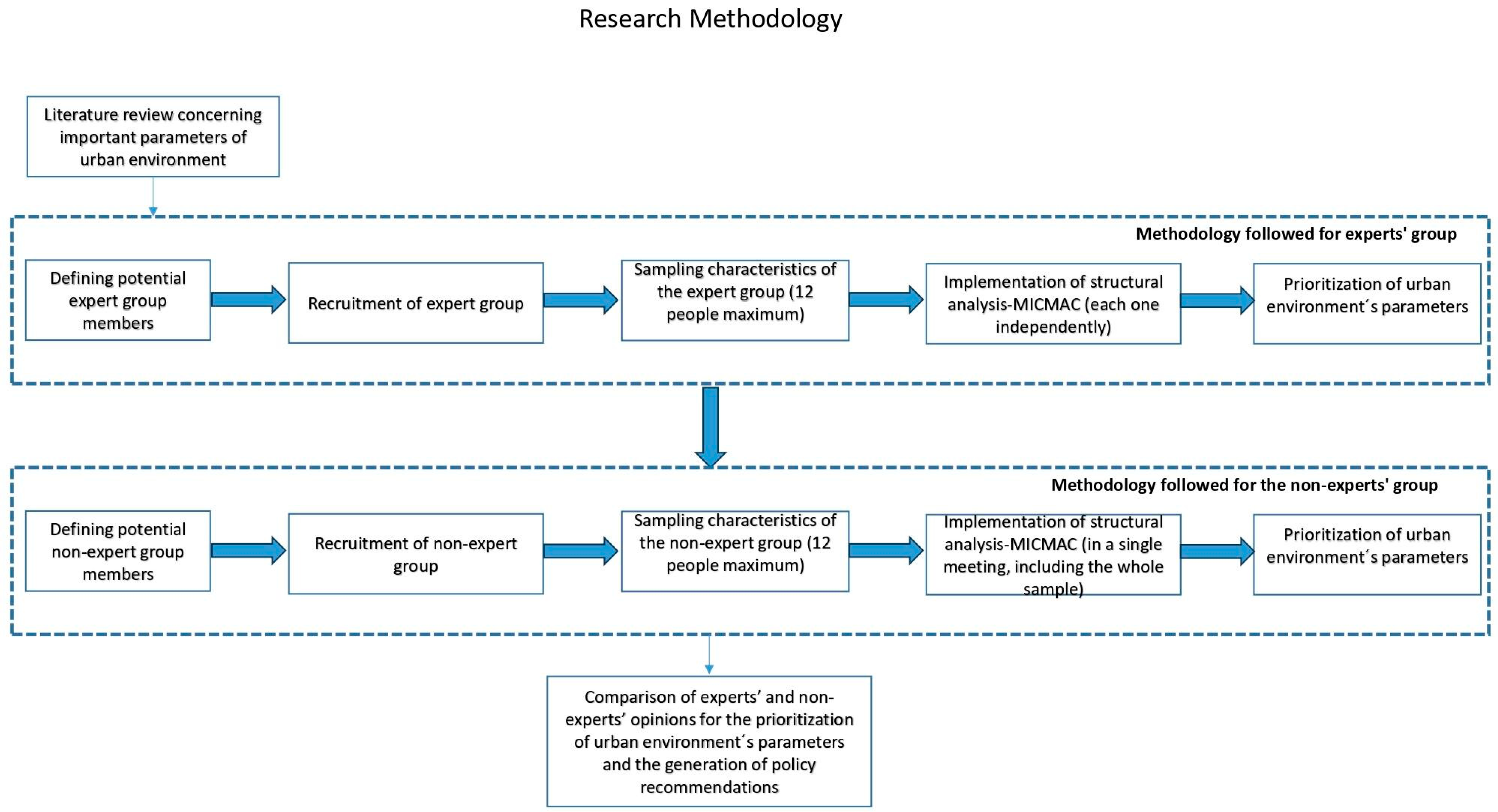

3. Method

3.1. Recruitment of People and Composition of Groups

3.2. Structural Analysis Overview

3.3. Inventory of Parameters and Composition-Invitation of Participants

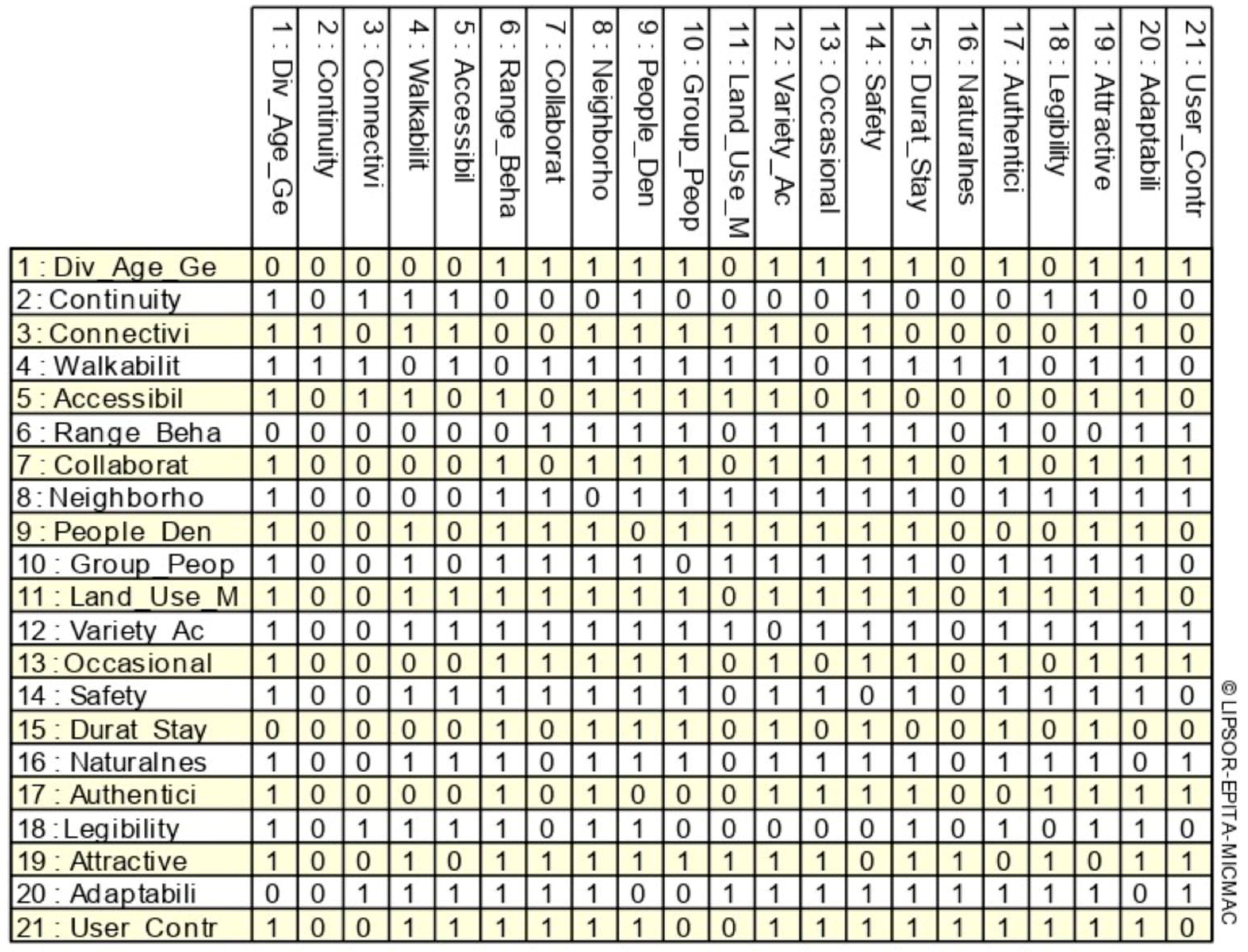

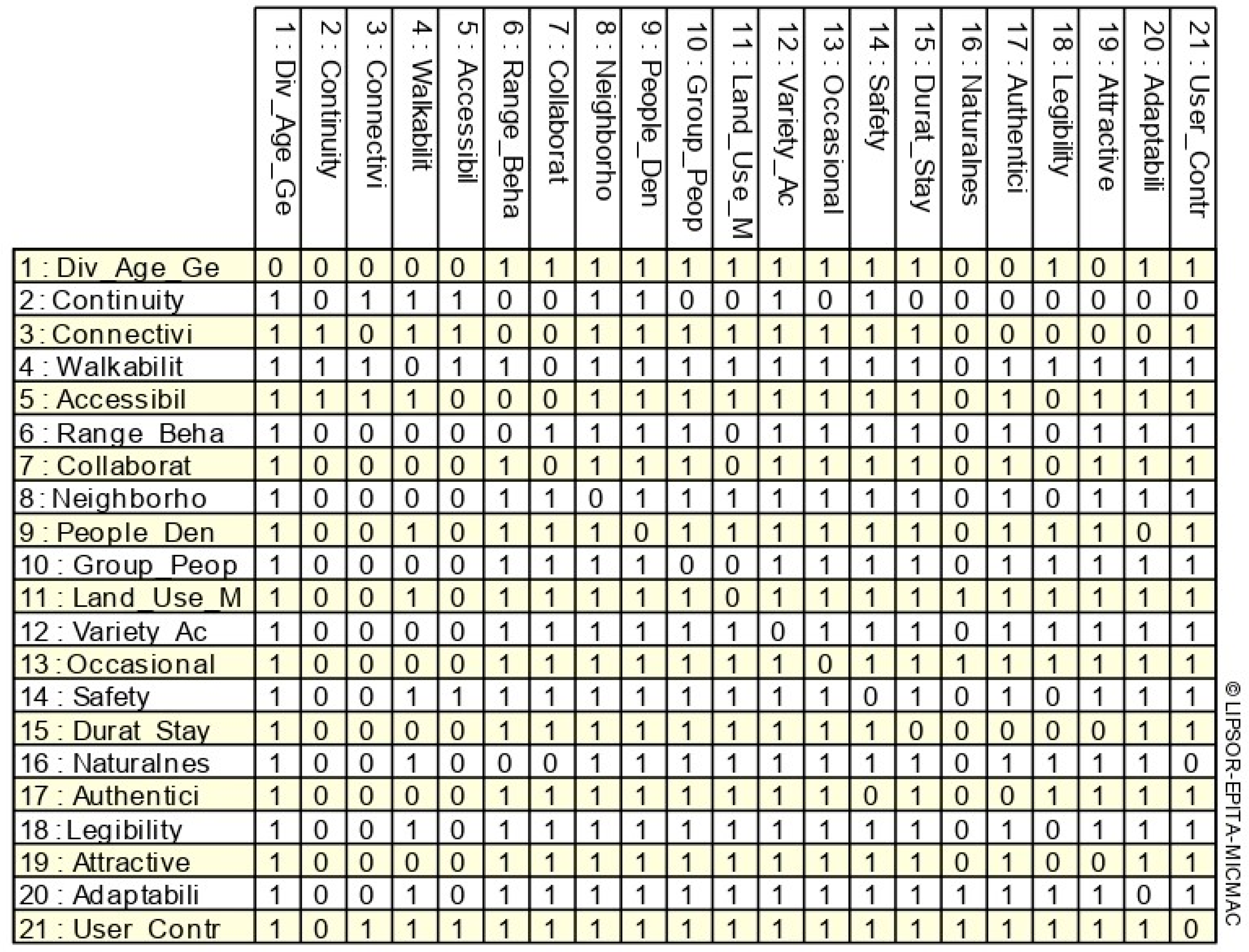

3.4. Recording Relationships Between Parameters

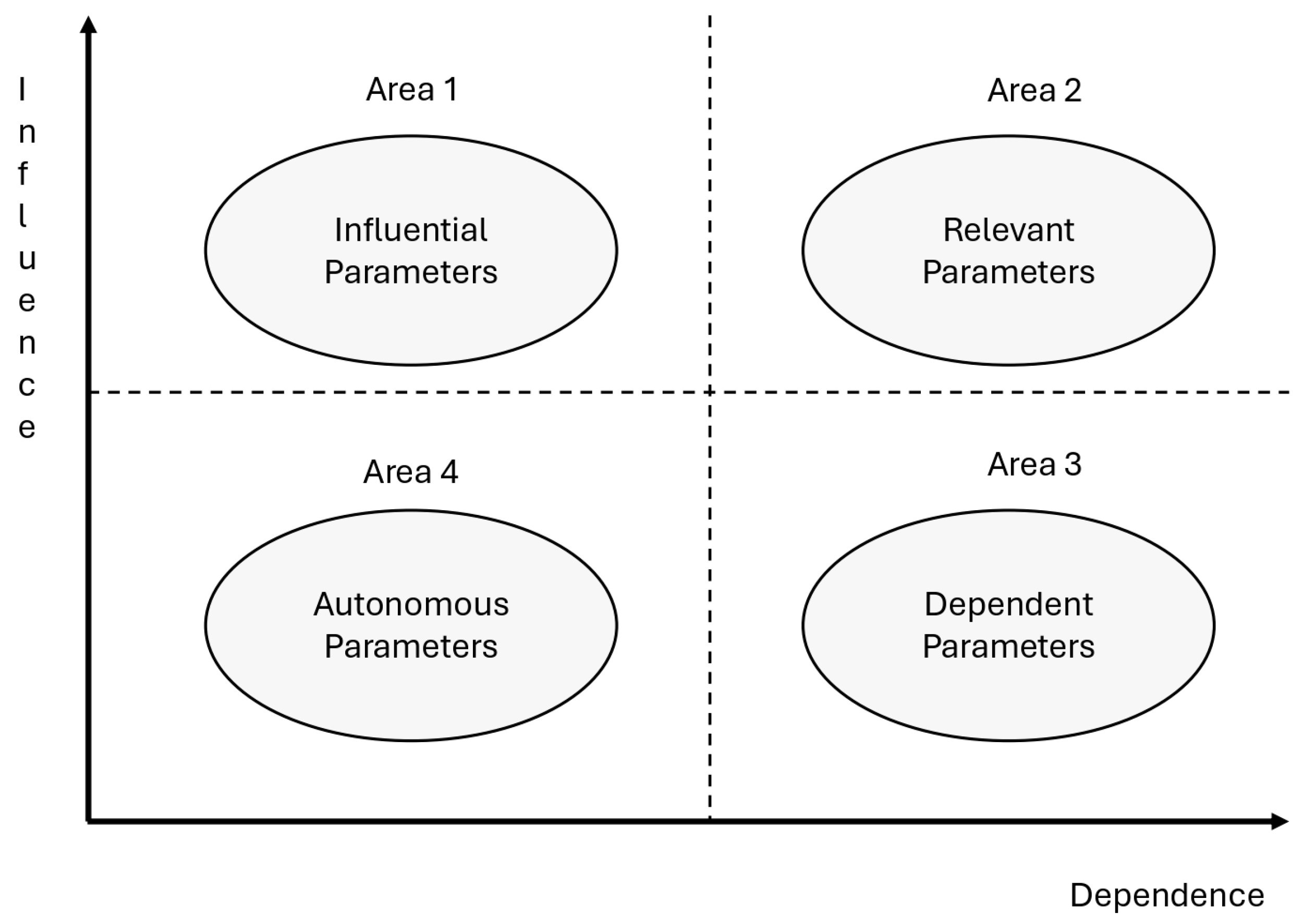

3.5. Parameters Prioritization

4. Results and Discussion

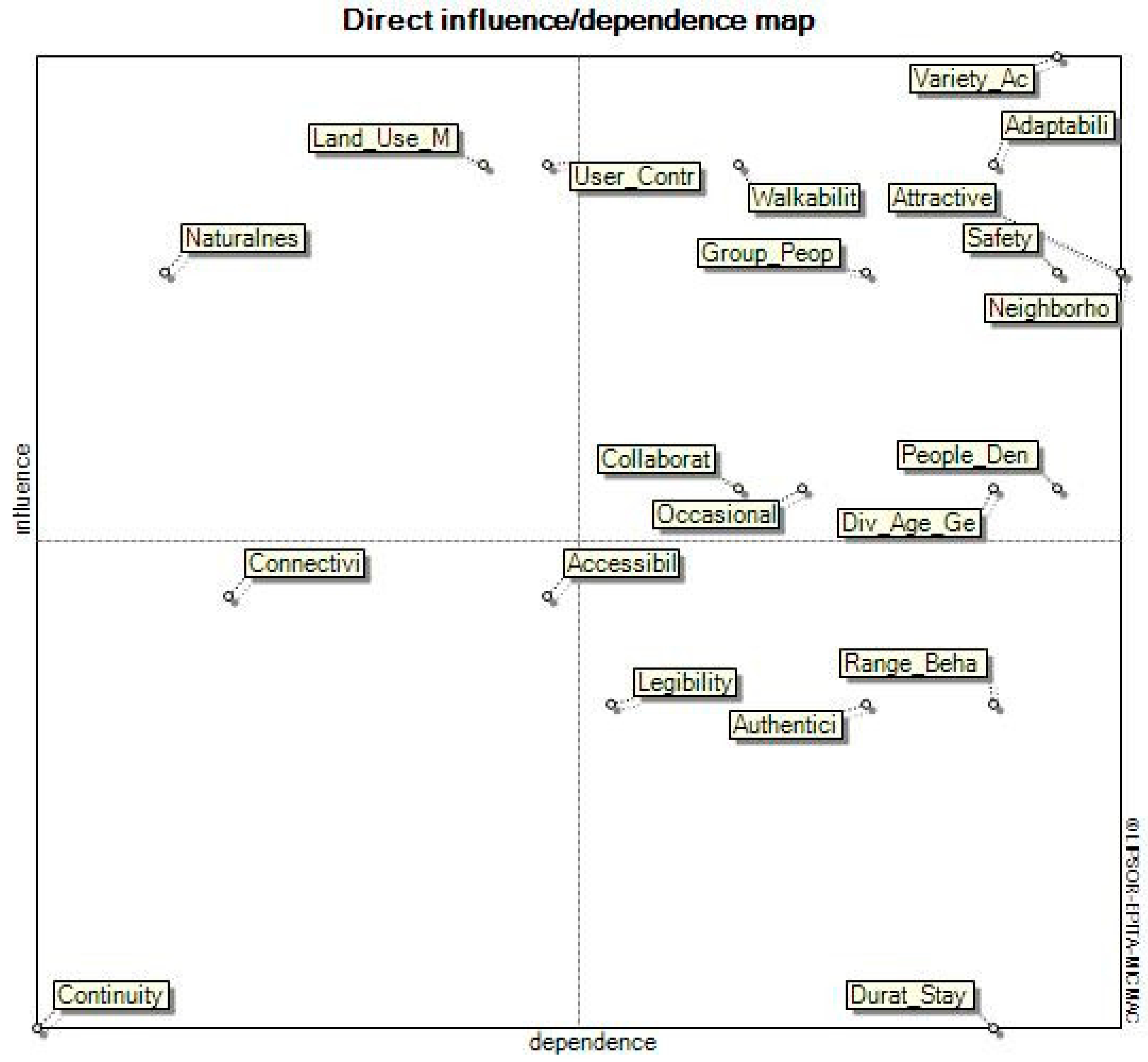

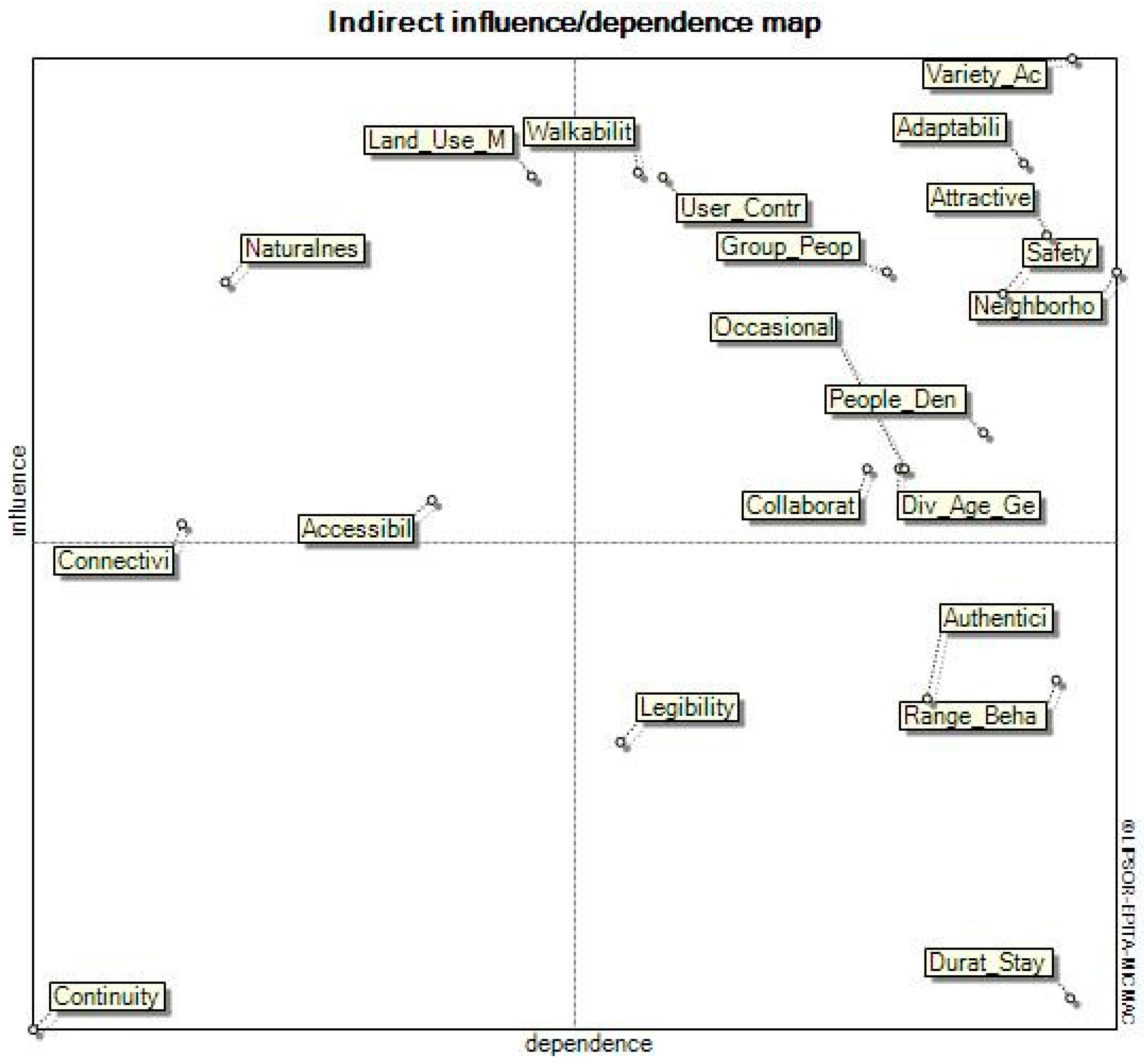

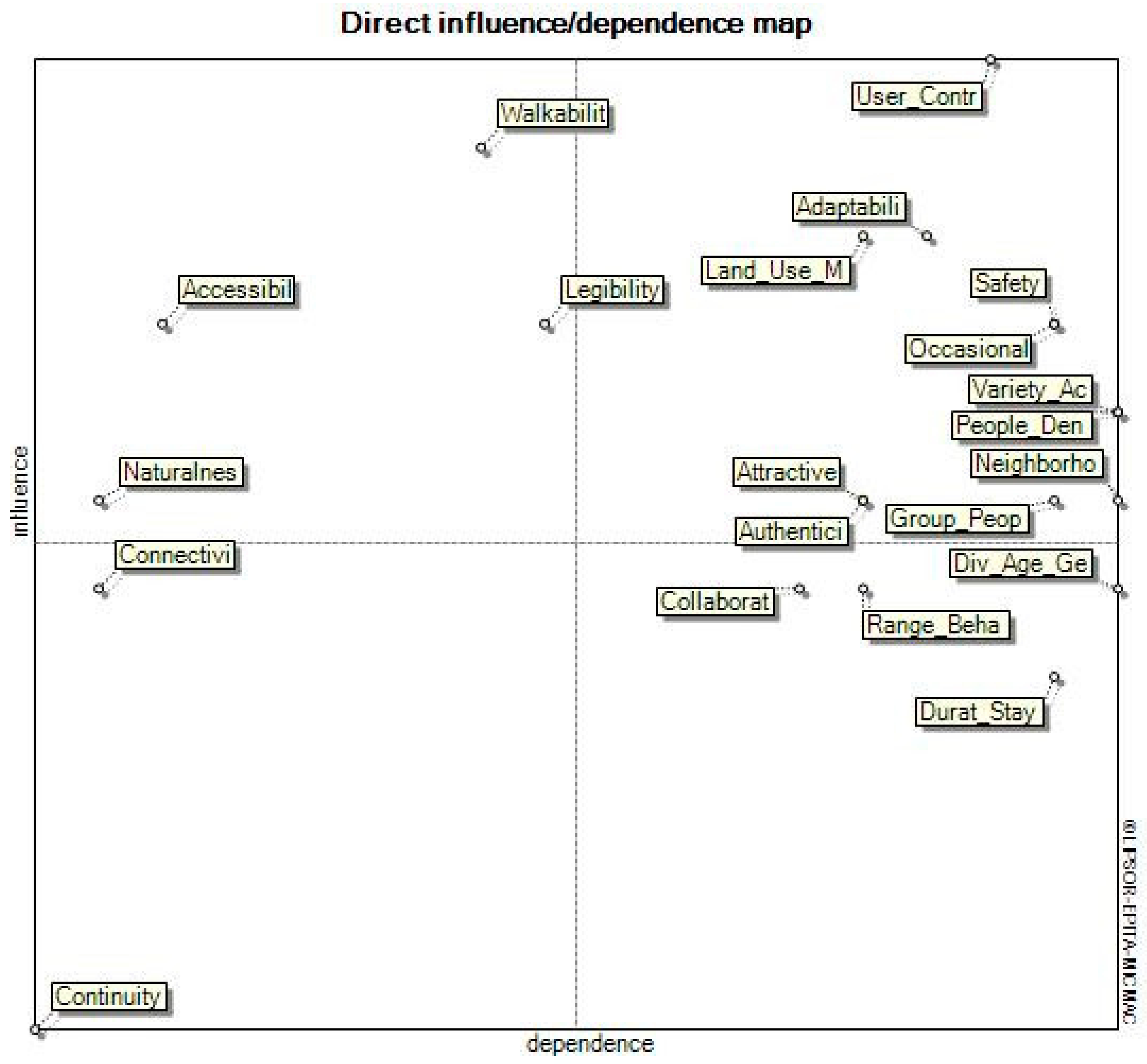

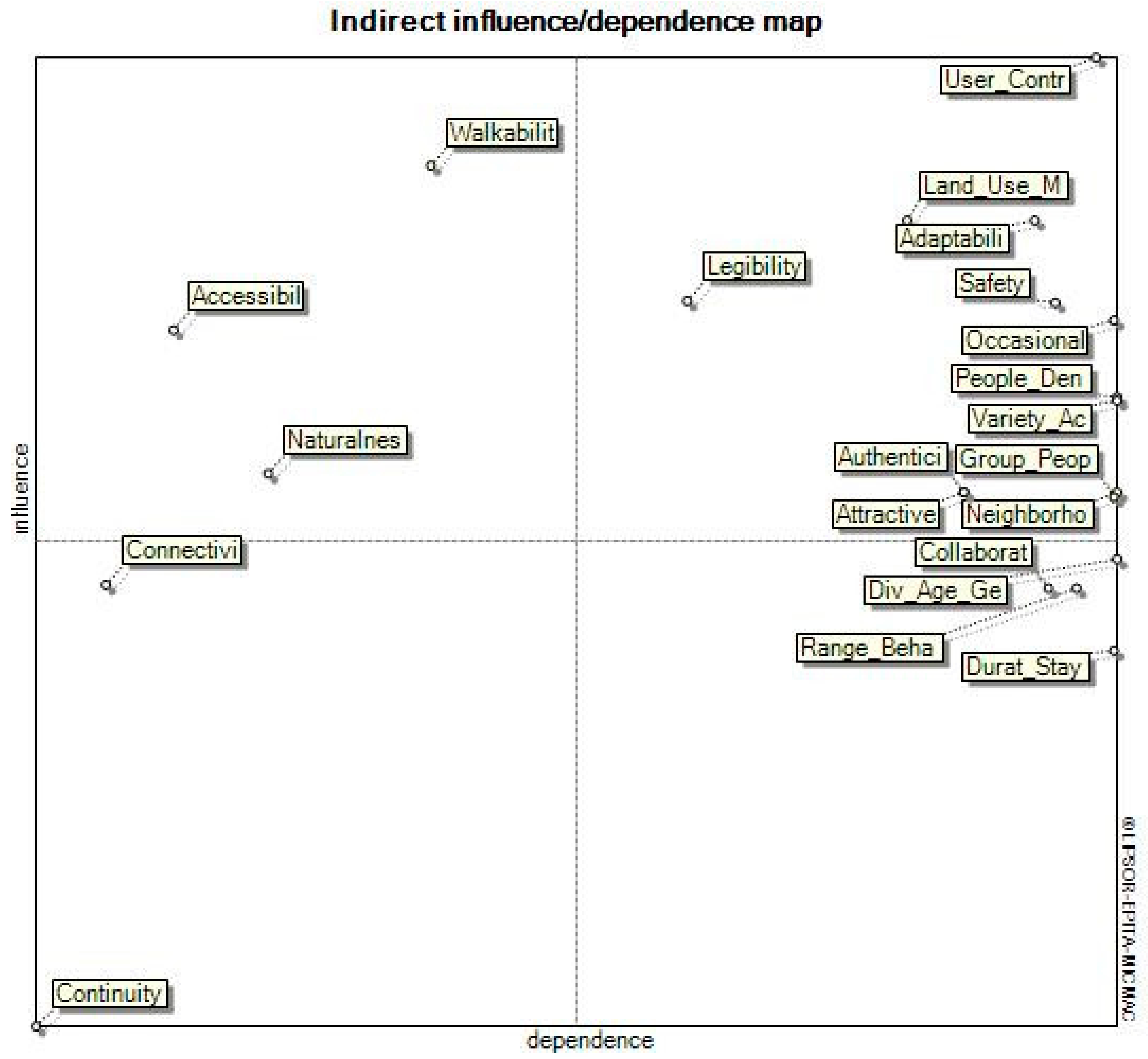

4.1. Structural Analysis Implementation

4.2. Policy Recommendations

- The promotion of multifunctionality in the components of public squares constitutes an approach directly associated with the enhancement of resilience and with the diversification of modes of use. Such an orientation renders public space more adaptable, a quality that is widely recognized as a highly influential variable, both by experts and by non-experts. A representative example refers to multifactional object of public square may be related to seating areas—according to literature [4,91,92], it is not limited to benches (primary seating) but may also include ledges around natural features, steps, terraces, or any other surface that can offer a basic level of comfort (secondary seating)—that can urge people to express different types of activities, like people watching, reading a book, eating a snack and working on a laptop. Flexible seating areas can be placed in various spots around a public square; in this way it is transformed into a particularly interesting environment compared to one with conventional primary seating. Such spaces can significantly influence the variety of activities, which is identified by the experts as the most influential variable in order for a square to be a successful one. Flexibility may also be understood as the capacity to design artifacts with dual functionality (polymorphic objectives), thereby enhancing the adaptive resilience of a local community when confronted with conditions of crisis (i.e., for the provision of temporary shelter for part of the population). Recent experiences of natural disasters (i.e., fires in Mati, 2018; earthquake in Samos, 2020; floods in Karditsa—Ianos and Daniel storms, 2020, 2023) in Greek cities foreground the relevance of such a practice within the discourse of urban design.

- Safety and sense of safety are two main variables that may be enhanced in public squares. Experts and non-experts were aligned with the literature [93,94], as they identified this variable as one of great importance for creating a successful public square. This objective may be accomplished through multiple design approaches. One aspect pertains to ensuring appropriate lighting conditions. This does not imply strong lighting, but rather light reflected on vertical surfaces, faces, walls, and so on, in order to ensure the differentiated use of the space across its various sub-areas. It is worth noting that this practice has been observed in recent urban design projects in Athens and across Greece, though to a modest extent, with a preference for the installation of lighting fixtures that provide indirect lighting. In many cases, lighting design even constitutes the core element of the overall design plan.

- Incorporating multisensory elements into public squares can significantly enhance their attractiveness and usability, which is an important variable from the perspective of experts. The integration of greenery, water features, ambient sound, and carefully designed lighting, as mentioned before, not only enriches the esthetic and experiential quality of the space but also encourages diverse activities throughout the day. Experts claimed that this matter is the main key factor that influences the success of a public square.It should be noted that this practice is well known worldwide and is also expressed in the literature. The “Power of 10+” theory by PPS is such an example according to which an area requires 10 major destinations—as is commonly stated—each of which should contain 10 distinct places, and within each place, there should be ten different activities for people to engage in [51]. However, in Greek practice, such an approach does not appear to have been widely adopted in the past, a tendency that is now shifting and can be attributed to the significance that experts assign to this variable.Although non-experts have not identified this variable (Variety of activities) as a critically important one, such sensory stimuli foster prolonged engagement, encourage social interaction, and support the occurrence of occasional activities, which are recognized as influential for the success of a public square. The facilitation of such activities is further reinforced by local community collaboration (i.e., Neighborhood associations), allowing groups to utilize public spaces for diverse purposes. This approach aligns with non-experts’ view about community engagement, as they recognize this quality as the most important in order for a square to be a successful one.

- Enhancing the degree of land-use mix is particularly important in areas of centrality, such as those surrounding public squares. Although experts did not identify this variable as among the most influential—possibly because in Greek cities land-use mix is the dominant pattern of urban development—non-experts emphasized its role in sustaining the vitality of squares, in line with the existing literature [2,79]. It is important to highlight, however, that there is an optimal degree of land-use mix. In practice, clustering of complementary activities such as recreation, commerce, and housing—particularly in case of neighborhood squares—is prioritized, as these functions encourage continuous public presence in the space.

- Artistic interventions may be applied in public squares, as they are considered a key element for strengthening the attractiveness of a square and for giving it a distinctive character that identifies it and makes it stand out in terms of esthetics and form [59]. Both the attractiveness and the character of an urban space are parameters recognized as quite influential for its success by the expert group. Within this framework, the promotion of public art is considered appropriate, along with the use of colors and a variety of materials that connect with the historical context of an area and the tradition of the respective place. These elements also define and differentiate the ways in which the space can function, as usually happens in cases of reclaiming surfaces from cars for pedestrians. Such a policy, which aligns with the prevailing trend to limit motorized traffic in cities and promote strategies for sustainable urban mobility, enhances continuity of public spaces, accessibility and legibility, which is considered, both by experts and by citizens, as a variable highly dependent on other factors.

- Community engagement was considered the most important quality in order to create successful and inclusive public squares, according to non-experts, as mentioned before. Participatory design allows community members to express their views, actively contribute to the formulation of proposals, and cultivate a sense of collective responsibility and “ownership” of the space, which was considered a variable significantly affected by other variables, according to non-experts. Within this framework, co-creation plays a decisive role, as it fosters cooperation between residents, local businesses, community organizations, and designers, ensuring that the design of public space reflects the real needs of the community [7,75]. At the same time, co-management of the space is vital for maintaining and adapting interventions to the changing requirements of users. To ensure active participation, the planning of participatory workshops and open discussions, combined with online surveys/voting and promotional campaigns, constitutes a key priority. Through these practices, stakeholders are not merely recipients of design proposals but become participants in the decision-making process, contributing to the formation of a space that responds to their real needs and desires. Furthermore, these processes enhance the sustainability of interventions, as social acceptance and local support are critical for the long-term preservation of public spaces. The involvement of different stakeholders in the stages of design and implementation can act as a catalyst in promoting positive changes in neighborhoods and in public spaces as a whole. It should be underlined that active community engagement in urban design practice across Greece was not commonly observed.

5. Conclusions

Study Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/wpp2022_summary_of_results.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Kyriakidis, C. Comparative study on the functioning of outdoor public urban spaces in Athenian neighborhoods. Aeichoros 2024, 40, 110–133. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakidis, C. Approaching the functioning of public urban space based on local parameters: A comparative study between Larissa and Nottingham. Aeichoros 2016, 24, 67–85. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Life Between Buildings—Using Public Space; Katsavounidou, G., Taranis, P., Eds.; University of Thessaly Press: Volos, Greece, 2013. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, V. The Street: A Quintessential Social Public Space; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Garvin, A. Enhancing the public realm. In Urban Parks and Open Space; Garvin, A., Berens, G., Eds.; ULI (Urban Land Institute): Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, W. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces; Conservation Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage Books Editions: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Stagias, A. Evaluating Tactical Urbanism Initiatives Through the Prism of Placemaking: A Case Study on Milan’s “Piazze Aperte”. Bachelor’s Thesis, School of Rural, Surveying & Geoinformatics Engineering, National Technical University of Athens, Athens, Greece, Department of Architecture & Urban Studies, Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Project for Public Spaces. Available online: https://www.pps.org/article/grplacefeat (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Siolas, A.; Vassi, A.; Vlastos, T.; Kyriakidis, C.; Bakogiannis, E.; Siti, M. Methods, Applications and Tools of Urban Planning; [Undergraduate Handbook]; Kallipos, Open Academic Editions: Athens, Greece, 2015. (In Greek) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moughtin, C. Urban Design: Street and Square, 3rd ed.; Architectural Press: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. City Design: What It Is and How It Might Be Taught (1980). In City Sense and City Design: Writings and Projects of Kevin Lynch; Banerjee, T., Southworth, M., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995; pp. 652–659. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, M.; Heath, T.; Oc, T.; Tiesdell, S. Public Places Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Urban Design Lab. Available online: https://urbandesignlab.in/definitions-of-urban-design/?srsltid=AfmBOorB81NiHjcHdsF0xoLMEjek8cYzl5YXwRsbeyh0QQIr4giHor9E (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Gehl, J.; Svarre, B. How to Study Public Life; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA; Covelo, CA, USA; London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bakogiannis, E.; Kyriakidis, C.; Kourmpa, E.; Siolas, A. The function of urban public spaces in medium size cities in Greece. First evaluation for Chalkida, Greece. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Humanities, Psychology and Social Sciences, Munich, Germany, 19–21 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, M.B.; McNevin, A. Global ideologies and urban landscapes: Introduction to the special issue. Globalizations 2010, 7, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, S.; Francis, M.; Rivlin, G.L.; Stone, M.A. Public Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Madanipour, A. Design of Urban Space: An Inquiry into a Socio-Spatial Process; John Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gospodini, A.A. Type and Function in the Urban Square: A Case Study of London. Ph.D. Thesis, University College London, London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. A Theory of Good City Form; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X. Understanding ‘Inclusiveness’ in Public Space. Master’s Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A. Urban form and social context: Cultural differentiation in the uses of urban parks. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 1995, 14, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, V. Evaluating Public Space. J. Urban Des. 2014, 19, 53–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelischer, C.; Loukaitou-Sideris, A. Intergenerational public space design and policy: A review of the literature. J. Plan. Lit. 2022, 37, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. Space, Place, and Gender; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Koskela, H. ‘Bold Walk and Breakings’: Women’s spatial confidence versus fear of violence. Gend. Place Cult. 1997, 4, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, L. Feminist City: Claiming Space in a Man-Made World; Verso: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Adebanjo, D.; Khosla, P.; Snyder, V. Gender Issue Guide: Urban Planning and Design; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UN Women. Progress of the World’s Women 2008/2009: Who Answers to Women? UN Women: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Imrie, R. Disability and discourses of mobility and movement. Environ. Plan. A 2000, 32, 1641–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindu, V.T.; Devi, M. Accessible Tourism: Determinants and Constraints; A Demand Side Perspective. Sociol. Geogr. Environ. Sci. 2016, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Buj, I. Accessibility development: A guide to sustain modern market for urban shopper’s diversity. Int. Conf. Community Dev. (ICCD) 2010, 1, 578–588. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. Inclusive, Safe and Accessible Public Space Booklet; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, M.; Tiesdell, S.; Heath, T.; Oc, T. Public Places—Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design; Elsevier: Oxford, UK; Burlington, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fallah, A.; Fallah, B. Identifying Environmental Affordance in Design Case Study: Kerman, Iran. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. Sci. 2015, 5, 445–450. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B. Space Is the Machine: A Configurational Theory of Architecture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Rafiemanzelat, R.; Karami, M.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A. City sustainability: The influence of walkability on built environments. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 24, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abley, S. Walkability Research Tools—Summary Report; NZ Transport Agency Research Report 356; NZ Transport Agency: Wellington, New Zealand, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Speck, J. Walkable City: How Downtown Can Save America, One Step at a Time; North Point Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Kodali, H.; Wyka, K.E.; Huang, T.T.K. Perceived neighborhood environment walkability and health-related quality of life among predominantly Black and Latino adults in New York City. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, A.; Southworth, M. Cities Afoot—Pedestrians, Walkability and Urban Design. J. Urban Des. 2008, 13, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, J.; Farrington, D.P. Rural accessibility, social inclusion and social justice: Towards conceptualisation. J. Transp. Geogr. 2005, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M. Placemaking and People-Making. J. Public Space 2022, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bakogiannis, E.; Kyriakidis, C.; Siti, M.; Siolas, A.; Vassi, A. Social mutation and lost neighborhoods in Athens, Greece. Int. J. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2015, 3, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, R.; Handy, S. Measuring the Unmeasurable: Urban Design Qualities Related to Walkability. J. Urban Des. 2009, 14, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, C.; Ishikawa, S.; Silverstein, M. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, E.T. The Hidden Dimension; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, R. Personal Space: The Behavioral Basis of Design; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Project for Public Spaces (PPS). Sociability: Public Spaces as an Antidote to Isolation. 2023. Available online: https://www.pps.org (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Montgomery, I. Making a City: Urbanity, Vitality and Urban Design. J. Urban Des. 1998, 3, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delitheou, V.; Bakogiannis, E.; Kyriakidis, C.; Katarachia, K.M. Economic activity and urban design policy as a means for recovery of commercial activity: The case study of Athens’ commercial streets. In Contemporary Issues in Social Science; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021; pp. 149–164. [Google Scholar]

- Katsavounidou, G. The City at the Human Scale; [Undergraduate Handbook]; Kallipos, Open Academic Editions: Athens, Greece, 2023. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Talen, E. The Social Goals of New Urbanism. Hous. Policy Debate 2002, 13, 165–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.S.; Baper, S.Y. Assessment of livability in commercial streets via placemaking. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M.; De Magalhães, C. Public Space Management: Present and Potential. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2006, 49, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B. Against Enclosure. In Rehumanising Housing; Teymur, N., Markus, T., Wooley, T., Eds.; Butterworths: London, UK, 1988; pp. 63–85. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, C.-F. Housing layout and crime vulnerability. Urban Des. Int. 2000, 5, 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, O. Defensible Space: People and Design in the Violent City; Architectural Press: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolopoulou, M.; Baker, N.; Steemers, K. Thermal comfort in outdoor urban spaces: Analysis across different European climates. Build. Environ. 2003, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, J.; Pretty, J. Urban Ecology and Urban Health and Well-Being. In Urban Ecology; Society, B.E., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 202–229. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, V.; Bosson, J. Third places and the social life of streets. Environ. Behav. 2010, 42, 779–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.B. A Sense of Place, A Sense of Time; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Relph, E. Place and Placelessness; Pion: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A. History and Precedent in Environmental Design; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M. Art, Space and the City: Public Art and Urban Futures; Routledge: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Landry, C. The Creative City: A Toolkit for Urban Innovators; Earthscan: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Praliya, S.; Garg, P. Public space quality evaluation: Prerequisite for public space management. J. Public Space 2019, 4, 93–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madanipour, A. Roles and challenges of urban design. J. Urban Des. 2006, 11, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatley, T. Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, P.; Jennings, I. Cities as Sustainable Ecosystems: Principles and Practices; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bakogiannis, E.; Potsiou, C.; Apostolopoulos, K.; Kyriakidis, C. Crowdsourced geospatial infrastructure for coastal management and planning for emerging post COVID-19 tourism demand. Tourism Hosp. 2021, 2, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies; Macmillan: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn, S.; Bentley, I.; Smith, G. Responsive Environments: A Manual for Designers; The Architectural Press: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Santos Nouri, A.; Costa, J.P. Placemaking and Climate Change Adaptation: New Qualitative and Quantitative Considerations for the ‘Place Diagram’. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2017, 10, 356–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatziioannou, I.; Nikitas, A.; Tzouras, P.G.; Bakogiannis, E.; Alvarez-Icaza, L.; Chias-Becerril, L.; Rexfelt, O. Ranking Sustainable Urban Mobility Indicators and Their Matching Transport Policies to Support Liveable City Futures: A MICMAC Approach. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2023, 18, 100788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatziioannou, I.; Alvarez-Icaza, L. A structural analysis method for the management of urban transportation infrastructure and its urban surroundings. Cogent Eng. 2017, 4, 1364053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatziioannou, I.; Alvarez-Icaza, L.; Bakogiannis, E.; Kyriakidis, C.; Chias-Becerril, L. A Structural Analysis for the Categorization of the Negative Externalities of Transport and the Hierarchical Organization of Sustainable Mobility’s Strategies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasopoulos, K. Towards a Method of Integrating Citizens into the Planning of Sustainable Urban Mobility Projects. Ph.D. Thesis, National Technical University of Athens, Athens, Greece, 2009. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou, I. Sampling Theory; [Undergraduate Handbook]; Kallipos, Open Academic Editions: Athens, Greece, 2015. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Arcade, J.; Godet, M.; Roubekat, F. Structural Analysis with the MICMAC Method & Actors’ Strategy with MACTOR Method; IIEP/UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, T.; Helmer, O. Report on a long-range forecasting study. In Social Technology; Gordon, T., Helmer, O., Eds.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1966; pp. 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Romero Perea, A. Methodology for the Ranking of Urban Passenger Transport Policies that Minimize the Negative Externalities. Ph.D. Thesis, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda, V.S. What is Inclusive and Accessible Public Space? J. Public Space 2022, 7, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakidis, C.; Chatziioannou, I.; Iliadis, F.; Nikitas, A.; Bakogiannis, E. Evaluating the public acceptance of sustainable mobility interventions responding to Covid-19: The case of the Great Walk of Athens and the importance of citizen engagement. Cities 2023, 132, 103966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlastos, A.; Bakogiannis, E. Towards a Greece with Fewer Cars; Grigoris Publications: Athens, Greece, 2019. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Theologou, K.; Zografos, A.; Kasimati, E.; Lenetis, G.; Sierra, A.; Hasalevri, E. Mapping the Idiodimo. Material and Immaterial Public Space in Modern Greece: The Idiodimon and the Status of Citizen; Ellinoekdotiki: Athens, Greece, 2016. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakidis, C.; Bakogiannis, E.; Siolas, A. Identifying Environmental Affordances in Kypseli Square in Athens, Greece. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Social Sciences, New York, NY, USA, 17–19 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Experts | Area of Expertise |

|---|---|

| 1 | Dr Urban Planner |

| 2 | Dr Transport Engineer |

| 3 | Dr Urban Planner |

| 4 | Urban Planner |

| 5 | Policymaker |

| 6 | Surveyor |

| 7 | Surveyor |

| 8 | Surveyor—PhD Candidate |

| 9 | Surveyor |

| 10 | Architect |

| 11 | Architect |

| 12 | Civil Engineer |

| Experts | Area of Expertise |

|---|---|

| 1 | Education |

| 2 | Insurance |

| 3 | Food and Beverage |

| 4 | Domestic Services |

| 5 | Entrepreneurship |

| 6 | Logistics-Supply Chain Management |

| 7 | Medicine |

| 8 | Business Administration |

| 9 | Mechanical Engineering |

| 10 | Agriculture Engineering |

| 11 | Law |

| 12 | Product Storage |

| Code | Parameter-Variable | Symbolism (In MICMAC Software) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Diversity in Age, Gender, and Physical Abilities | Div_Age_Ge |

| 2 | Continuity | Continuity |

| 3 | Connectivity | Connectivi |

| 4 | Walkability | Walkabilit |

| 5 | Accessibility | Accessibil |

| 6 | Range of Behaviors | Range_Beha |

| 7 | Collaborativeness | Collaborat |

| 8 | Neighborhood Character | Neighborho |

| 9 | Human Density | People_Den |

| 10 | Groups of People | Group_Peop |

| 11 | Land-Use Mix | Land_Use_M |

| 12 | Variety of Activities and Opportunities | Variety_Ac |

| 13 | Occasional Active Uses | Occasional |

| 14 | Safety | Safety |

| 15 | Duration of Stay | Durat_Stay |

| 16 | Naturalness | Naturalnes |

| 17 | Authenticity and Sense of Space | Authentici |

| 18 | Legibility | Legibility |

| 19 | Attractiveness and Resilience | Attractive |

| 20 | Adaptability | Adaptabili |

| 21 | User Control | User_Contr |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chatziioannou, I.; Kanellopoulos, P.; Kyriakidis, C.; Bakogiannis, E. Bridging Perceptions: A Comparative Evaluation of Public Space Design Qualities by Experts and Users. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 412. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9100412

Chatziioannou I, Kanellopoulos P, Kyriakidis C, Bakogiannis E. Bridging Perceptions: A Comparative Evaluation of Public Space Design Qualities by Experts and Users. Urban Science. 2025; 9(10):412. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9100412

Chicago/Turabian StyleChatziioannou, Ioannis, Panagiotis Kanellopoulos, Charalampos Kyriakidis, and Efthimios Bakogiannis. 2025. "Bridging Perceptions: A Comparative Evaluation of Public Space Design Qualities by Experts and Users" Urban Science 9, no. 10: 412. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9100412

APA StyleChatziioannou, I., Kanellopoulos, P., Kyriakidis, C., & Bakogiannis, E. (2025). Bridging Perceptions: A Comparative Evaluation of Public Space Design Qualities by Experts and Users. Urban Science, 9(10), 412. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9100412